Abstract

Background:

In Canada, gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBM) are disproportionately affected by HIV. Our objective was to describe access to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and identify factors associated with not using PrEP among self-reported HIV-negative or HIV-unknown GBM.

Methods:

This was a cross-sectional analysis of the Engage study cohort. Between 2017 and 2019, sexually active GBM aged 16 years or more in Montréal, Toronto and Vancouver were recruited via respondent-driven sampling (RDS). Participation included testing for HIV and sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections, and completion of a questionnaire. We examined PrEP access using a health care services model and fit RDS-adjusted logistic regressions to determine correlates of not using PrEP among those for whom PrEP was clinically recommended and who were aware of the intervention.

Results:

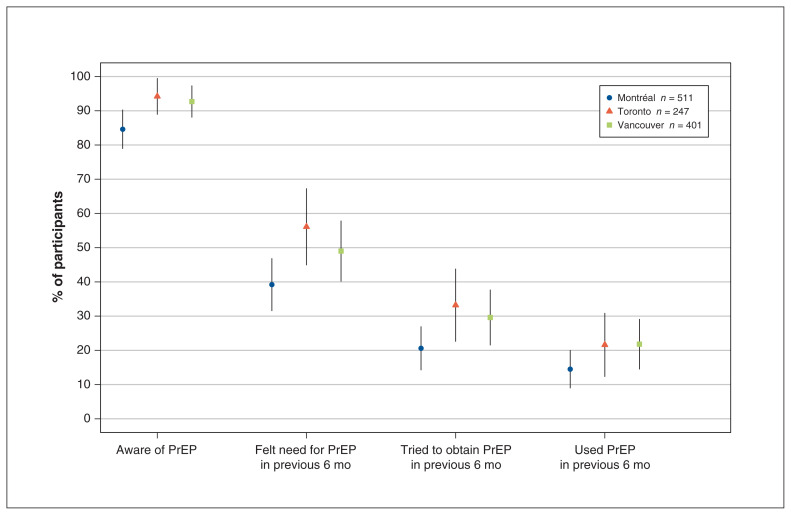

A total of 2449 GBM were recruited, of whom 2008 were HIV-negative or HIV-unknown; 1159 (511 in Montréal, 247 in Toronto and 401 in Vancouver) met clinical recommendations for PrEP. Of the 1159, 1100 were aware of PrEP (RDS-adjusted proportion: Montréal 84.6%, Toronto 94.2%, Vancouver 92.7%), 678 had felt the need for PrEP in the previous 6 months (RDS-adjusted proportion: Montréal 39.2%, Toronto 56.1%, Vancouver 49.0%), 406 had tried to access PrEP in the previous 6 months (RDS-adjusted proportion: Montréal 20.6%, Toronto 33.2%, Vancouver 29.6%) and 319 had used PrEP in the previous 6 months (RDS-adjusted proportion: Montréal 14.5%, Toronto 21.6%, Vancouver 21.8%). Not using PrEP was associated with several factors, including not feeling at high enough risk, viewing PrEP as not completely effective, not having a primary care provider and lacking medication insurance.

Interpretation:

Although half of GBM met clinical recommendations for PrEP, less than a quarter of them reported use. Despite high levels of awareness, a programmatic response that addresses PrEP-related perceptions and health care system barriers is needed to scale up PrEP access among GBM in Canada.

The HIV epidemic continues to disproportionately affect gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBM) in Canada. Although GBM account for 2%–3% of the Canadian population, they represent almost half of all prevalent and newly reported cases of HIV infection.1–3 The disease burden is concentrated in Canada’s 3 largest cities — Montréal, Toronto and Vancouver — where many GBM reside.4,5 HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with antiretroviral medication (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate or tenofovir alafenamide combined with emtricitabine) has been shown to be effective in preventing HIV infection in HIV-negative GBM.6–8 The Canadian guideline on HIV PrEP provides clinical criteria for use of this intervention among those at high risk for HIV infection, including GBM.9 Pre-exposure prophylaxis was approved in Canada in 201610 and is increasingly available. It was approved in Quebec in 2013,11–14 in Ontario in 201715 and in British Columbia in 2018.16

Documenting PrEP uptake and related barriers, especially among GBM who may benefit, is important, as this intervention is scaled up. Understanding uptake may be guided by considering a prevention cascade17 and conceptual frameworks for accessing health care services.18–20 Although a variety of patient-, provider- and system-related barriers to PrEP use are known,21–23 several studies involved clinical cohorts or were conducted before changes were made to provincial programs.22,24,25 We describe access to HIV PrEP in a population-based sample of GBM in Montréal, Toronto and Vancouver (objective 1), and identify factors associated with not using PrEP among HIV-negative and HIV-unknown GBM meeting clinical recommendations for PrEP (objective 2).

Methods

Study design and setting

This study was a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from the Engage cohort.26–28 Engage is a mixed-methods prospective biobehavioural study examining antiretroviral-based prevention of HIV infection and the occurrence of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections among GBM. It is being conducted in Montréal, Toronto and Vancouver. Respondent-driven sampling (RDS), an adapted form of chain referral, was used to recruit participants; this method is recommended for studies where a sampling frame is unavailable.29 Respondent-driven sampling has the advantage of not depending on physical venues (e.g., time–location sampling), community-based organizations or networks, or access to the Internet (e.g., Internet-based sampling). Recruitment starts with nonrandomly selected initial participants (“seeds”), who recruit other eligible participants through their social networks. Respondent-driven sampling aims to approximate probabilistic sampling by adjusting estimates based on the size of participants’ social networks.29–31

Participants

Eligible participants were 16 years of age or more, gender-identified as a man (including trans men), reported sexual activity with a man in the previous 6 months, and were able to read English or French. Seeds were purposively selected to represent diverse features of the population. Members of community engagement committees (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/2/E529/suppl/DC1) at each site were asked to identify people representing the diversity of the GBM community (e.g., age, gender identity, ethnicity, HIV status). Each seed and subsequent participants were given 6 recruitment coupons to invite peers; unique identification numbers were assigned to each participant, and information on who recruited whom was tracked.29 Participants received compensation for the study visit ($50) and for each peer recruited ($15). All participants provided written informed consent. Further details on the RDS method are described elsewhere.26 The STROBE-RDS checklist guided reporting.32

Participants were recruited from February 2017 to June 2018 in Montréal, May 2017 to August 2019 in Toronto, and February 2017 to August 2019 in Vancouver; periods varied based on differences in recruitment rates across cities. The overall target sample size (n = 2160 [720 per city]) was based on precision for estimates of recent HIV infection and the power to study relations between various independent variables and selected outcomes.

Data collection

Participants completed a questionnaire using computer-assisted self-interviewing, after which they underwent testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections performed by a research nurse; this was done during 1 visit at the study site. The baseline questionnaire was designed based on several frameworks (Ivankovich’s Model of Sexual Health,33 an access to health care framework20 and syndemic theory34,35). Questions from field-tested instruments, such as the Canadian M-Track36 and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention behavioural surveys,37 were also included or harmonized to allow comparability. We used selected questionnaire items for the current study.

Analytical sample

To describe access to PrEP (objective 1), we included all participants who self-reported being HIV-negative or HIV-unknown and met the criteria of the Canadian clinical guideline for HIV PrEP.9 According to this guideline, PrEP is recommended for GBM who report condomless anal sex in the previous 6 months and at least 1 of the following: 1) diagnosis of syphilis or rectal sexually transmitted infection in the previous year, 2) more than 1 instance of previous use of HIV postexposure prophylaxis, 3) a relationship with an HIV-positive partner at risk of transmitting HIV and 4) an HIV incidence risk index for men who have sex with men (HIRI-MSM) score of 11 or higher.38 The HIRI-MSM is a validated 6-item screening tool.39 Corresponding questionnaire items are available in Appendix 2 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/2/E529/suppl/DC1).

To identify factors associated with not using PrEP (objective 2), the analysis was limited to self-reported HIV-negative or HIV-unknown GBM who met clinical recommendations for PrEP and were aware of PrEP, a necessary condition to use PrEP.

Variables

Outcome variables

For objective 1, we used the following measures: awareness of PrEP, having perceived the need for PrEP in the previous 6 months, having tried to access PrEP in the previous 6 months and PrEP use in the previous 6 months. For objective 2, the main outcome of interest was no PrEP use in the previous 6 months. Corresponding questionnaire items are available in Appendix 2.

Independent variables

We selected variables based on expert knowledge and a literature review of factors associated with PrEP use.21–25,40–44 The main independent variables for objective 2 align with the access to health care framework,20 specifically perceiving the need for care, seeking care, reaching and paying for care, and engaging in care. Details regarding the development of these questionnaire items are available in Appendix 1. Variables were grouped into the following categories: sociodemographic, prevention strategies related to sexual behaviour and dimensions of access. A complete list of potential correlates is available in Appendix 3, Table S2.2 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/2/E529/suppl/DC1). Although most questionnaire items had Likert-scale response options, variables were treated as categoric (i.e., agreement v. disagreement) to facilitate interpretation.

Statistical analysis

We adjusted all analyses using RDS-II weights31 (inverse probability of sampling weights that are proportional to participant network size), thereby accounting for the likelihood that people with larger social networks would be recruited. The question used to capture social network size is available in Appendix 2.

For objective 1, we calculated crude and RDS-adjusted estimates for each city. For objective 2, because of numerous potential correlates, we took several steps to reduce the number of variables to retain power and interpretability. First, we used univariable logistic regression analyses, stratified by city, to identify potential factors associated with not using PrEP. We selected factors exhibiting similar relations (i.e., direction of association) in each city for pooled (3-city) analyses in order to include salient factors common across cities. We further reduced the total number of variables using correlation matrices; for correlated items (Spearman correlation coefficient ≥ |0.3|), those amenable to intervention were prioritized. We then conducted univariable logistic regressions on pooled data to identify significant correlates (p < 0.10, given the exploratory nature of the analysis) and developed a multivariable logistic regression on pooled data, adjusting for city and year of recruitment to reflect the progressive and varied implementation of PrEP across cities and recruitment periods. To account for the RDS weights, we used quasibinomial regressions. Owing to limited missingness on reported independent variables (0%–6.2%), we performed a complete case analysis. We performed 2 sensitivity analyses: using all independent variables as continuous measures, and repeating the multivariable regression analysis without RDS weights. We performed all analyses using R statistical software and the RDS package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Ethics approval

The Engage cohort study was approved by the research ethics boards of the following institutions: the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, Ryerson University, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto (Health Sciences), University of Windsor, University of British Columbia, University of Victoria and Simon Fraser University.

Results

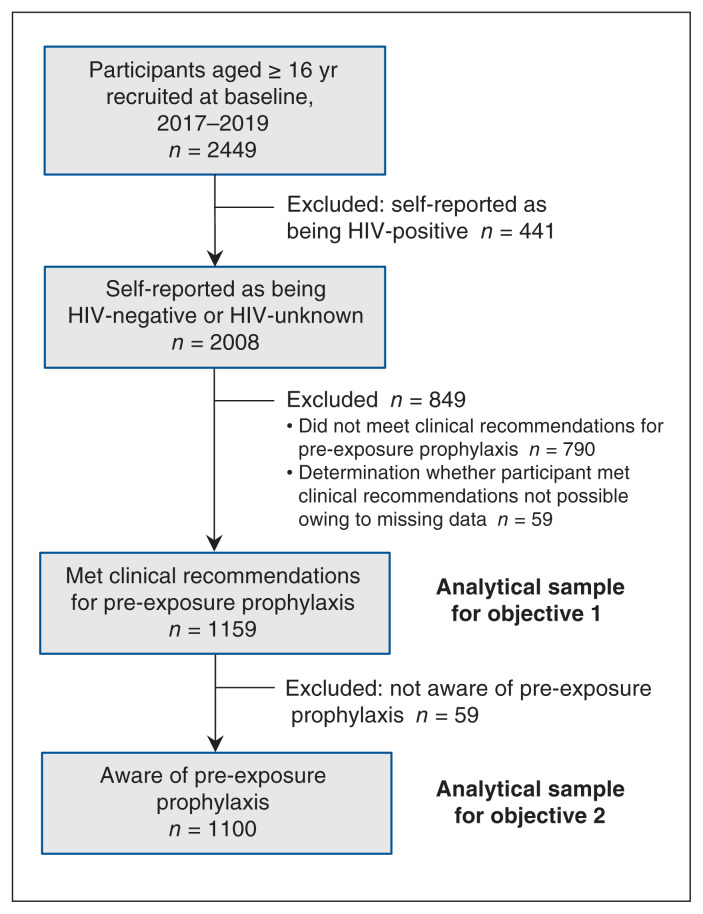

A total of 2449 participants were recruited: 1179 (seeds: 27) in Montréal, 517 (seeds: 96) in Toronto and 753 (seeds: 117) in Vancouver. The RDS recruitment trees are presented in Appendix 4 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/2/E529/suppl/DC1). Of the 2449, 2008 self-reported as HIV-negative or HIV-unknown (Figure 1); the RDS-adjusted proportions of HIV-negative or HIV-unknown participants were 86.3% (95% confidence interval [CI] 82.8%–89.8%), 78.5% (95% CI 74.0%–83.0%) and 79.7% (95% CI 74.1%–85.2%) in Montréal, Toronto and Vancouver, respectively. The proportions of the 2008 participants who met clinical recommendations for PrEP were 49.9% (95% CI 44.1%–55.6%), 44.9% (95% CI 36.6%–53.1%) and 58.1% (95% CI 51.1%–65.2%) in Montréal, Toronto and Vancouver, respectively. A breakdown of participants by the Canadian guideline criteria is available in Appendix 3, Figure S1, Table S3.

Figure 1:

Flow diagram showing selection of study participants.

A total of 1159 participants (median age 30 yr, age range 17–73 yr) met clinical recommendations for PrEP; determination whether the participant met clinical recommendation for PrEP was not possible for 3.5% (Montréal), 3.6% (Toronto) and 1.6% (Vancouver) of participants owing to missing data. Most of the 1159 identified as cisgender (88.5%–99.0% across cities) and gay (81.4%–89.3%), and were born in Canada (60.3%–63.6%) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Sociodemographic characteristics of self-reported HIV-negative or HIV-unknown participants for whom pre-exposure prophylaxis was clinically recommended

| Characteristic | Montréal n = 511 |

Toronto n = 247 |

Vancouver n = 401 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Crude %* | RDS-adjusted % (95% CI)† | Crude %* | RDS-adjusted % (95% CI)† | Crude %* | RDS-adjusted % (95% CI)† | |

| Age, median (Q1, Q3), yr | 30 (25, 36) | 30 (26, 34) | 30 (26, 35) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Gender identity‡ | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Cis | 94.5 | 88.5 (82.3–94.7) | 96.8 | 99.0 (97.8–100.0) | 96.5 | 97.2 (93.8–100.0) |

|

| ||||||

| Trans | 0.6 | 1.6 (0.0–4.5) | 0.4 | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Genderqueer/gender nonconforming | 3.3 | 3.3 (1.1–5.5) | 2.4 | 0.9 (0.0–2.0) | 2.5 | 1.4 (0.0–3.1) |

|

| ||||||

| Other | 1.6 | 6.6 (1.2–12.0) | 0.4 | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | 1.0 | 1.4 (0.0–4.4) |

|

| ||||||

| Sexual orientation | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Gay | 87.5 | 83.8 (78.1–89.4) | 80.6 | 81.4 (71.6–91.2) | 86.8 | 89.3 (85.1–93.4) |

|

| ||||||

| Queer | 5.1 | 3.4 (1.1–5.8) | 14.6 | 12.7 (4.2–21.1) | 5.7 | 2.7 (0.3–5.2) |

|

| ||||||

| Bisexual | 4.3 | 6.0 (2.1–10.0) | 2.4 | 5.1 (0.0–11.4) | 5.0 | 6.7 (3.5–9.8) |

|

| ||||||

| Other | 3.1 | 6.8 (2.9–10.6) | 2.4 | 0.8 (0.0–1.7) | 2.5 | 1.3 (0.2–2.5) |

|

| ||||||

| Ethnicity§ | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Canadian | 56.6 | 47.8 (40.2–55.3) | 40.1 | 31.2 (21.4–41.0) | 46.1 | 40.0 (32.1–48.0) |

|

| ||||||

| European | 16.6 | 16.0 (11.0–21.1) | 24.7 | 29.0 (19.3–38.8) | 22.4 | 18.2 (10.6–25.7) |

|

| ||||||

| Asian | 4.1 | 5.4 (1.3–9.6) | 13.4 | 12.0 (6.9–17.0) | 16.7 | 23.3 (16.8–29.9) |

|

| ||||||

| Latin American | 9.8 | 13.5 (7.0–20.0) | 7.7 | 8.7 (3.2–14.2) | 6.7 | 11.2 (6.4–16.1) |

|

| ||||||

| African, Black, Caribbean | 2.9 | 3.9 (0.7–7.0) | 3.2 | 3.9 (0.0–8.5) | 1.5 | 1.2 (0.0–2.8) |

|

| ||||||

| Arab or North African | 3.9 | 7.4 (3.6–11.3) | 1.2 | 1.6 (0.0–3.6) | 0.7 | 0.6 (0.0–2.2) |

|

| ||||||

| Aboriginal or Indigenous | 0.8 | 2.0 (0.0–4.8) | 0.4 | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | 1.7 | 0.5 (0.0–1.3) |

|

| ||||||

| Other | 5.3 | 3.9 (0.8–6.9) | 9.3 | 13.5 (5.0–22.0) | 4.0 | 5.0 (0.7–9.3) |

|

| ||||||

| Born in Canada | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Yes | 63.6 | 54.5 (46.8–62.3) | 60.3 | 49.0 (38.3–59.6) | 62.8 | 55.6 (47.2–64.1) |

|

| ||||||

| No | 36.4 | 45.5 (37.7–53.2) | 39.7 | 51.0 (40.4–61.7) | 37.2 | 44.4 (35.9–52.8) |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| High school or less | 14.9 | 15.4 (10.9–19.9) | 9.3 | 12.9 (6.2–19.6) | 10.7 | 10.6 (6.1–15.0) |

|

| ||||||

| More than high school | 85.1 | 84.6 (80.1–89.1) | 90.7 | 87.1 (80.4–93.8) | 89.3 | 89.4 (85.0–93.9) |

|

| ||||||

| Annual income, $ | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| < 30 000 | 52.4 | 65.1 (58.4–71.8) | 44.1 | 52.3 (41.6–63.0) | 40.9 | 54.7 (46.5–63.0) |

|

| ||||||

| 30 000–50 000 | 26.6 | 18.6 (13.4–23.8) | 23.5 | 22.0 (14.8–29.2) | 23.7 | 21.5 (14.7–28.4) |

|

| ||||||

| ≥ 50 000 | 20.9 | 16.3 (11.7–21.0) | 32.4 | 25.7 (16.0–35.5) | 35.4 | 23.7 (16.6–30.9) |

|

| ||||||

| Primary care provider aware of male sexual partners | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Yes | 53.4 | 40.9 (33.4–48.4) | 66.8 | 54.7 (43.6–65.8) | 45.4 | 27.6 (20.5–34.6) |

|

| ||||||

| No | 7.6 | 14.5 (9.0–20.0) | 10.1 | 14.8 (6.1–23.5) | 18.0 | 26.4 (19.5–33.4) |

|

| ||||||

| No primary care provider | 38.9 | 44.6 (37.0–52.2) | 23.1 | 30.5 (20.0–41.0) | 36.7 | 46.0 (37.6–54.4) |

|

| ||||||

| Has medication insurance | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Yes | 73.6 | 68.0 (60.9–75.0) | 62.3 | 55.4 (45.2–65.7) | 69.3 | 61.9 (53.8–70.1) |

|

| ||||||

| No | 26.4 | 32.0 (25.0–39.1) | 37.7 | 44.6 (34.3–54.8) | 30.7 | 38.1 (29.9–46.2) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, RDS = respondent-driven sampling.

Except where noted otherwise.

RDS-II weights were used.31

Participants were asked “If you had to choose one term that you felt best described your gender, which would you choose?” The “other” category included 2-spirit, genderfluid and agender.

As worded in the questionnaire.

Awareness of and access to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis

The rate of awareness of HIV PrEP ranged from 84.6% in Montréal to 94.2% in Toronto. In the previous 6 months, 39.2% (Montréal) to 56.1% (Toronto) of participants had perceived the need for PrEP, 20.6% (Montréal) to 33.2% (Toronto) had tried to access PrEP, and 14.5% (Montréal) to 21.8% (Vancouver) had used PrEP (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Access to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among self-reported HIV-negative or HIV-unknown participants for whom PrEP was clinically recommended (n = 1159). Proportions are respondent-driven sampling (RDS)-adjusted RDS-II weights.31 Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

In pooled multivariable models, not using PrEP was significantly associated with being in a relationship with a main partner (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.85, 95% CI 1.21–2.86), not feeling at high enough risk to use PrEP (adjusted OR 6.20, 95% CI 3.61–11.10), not knowing enough about PrEP to determine whether it was right for them (adjusted OR 2.33, 95% CI 1.37–4.05) and perceiving PrEP to not be very effective (adjusted OR 3.97, 95% CI 2.23–7.38) (Table 2). Other factors associated with nonuse included not choosing sexual partners based on their PrEP use (adjusted OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.02–2.41) and continuing condom use if taking PrEP (adjusted OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.27–3.14).

Table 2:

Factors associated with not using pre-exposure prophylaxis among self-reported HIV-negative or unknown participants for whom pre-exposure prophylaxis was clinically recommended and who were aware of pre-exposure prophylaxis

| Factor† | Univariable analysis, OR (95% CI)* n = 1032–1100 |

Multivariable analysis, adjusted OR (95% CI)* n = 987 |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Age, yr | ||

| ≥ 30 | Reference | Reference |

| < 30 | 2.10 (1.56–2.82) | 1.13 (0.74–1.74) |

| Education | ||

| More than high school | Reference | Reference |

| High school or less | 1.83 (1.08–3.34) | 1.35 (0.64–3.00) |

| Income, $ | ||

| ≥ 30 000 | Reference | Reference |

| < 30 000 | 1.62 (1.21–2.18) | 1.02 (0.65–1.58) |

| In a relationship with a main partner | ||

| No | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 2.20 (1.63–2.97) | 1.85 (1.21–2.86) |

| Prevention strategies related to sexual behaviour | ||

| Viral load sorting as HIV prevention strategy | ||

| Yes | Reference | Reference |

| No | 3.12 (2.22–4.38) | 1.51 (0.93–2.46) |

| Dimensions related to perceiving need for care | ||

| Perceived risk of HIV infection | ||

| “I don’t feel that I am at high enough risk to use PrEP” | ||

| Strongly disagree/disagree/neutral | Reference | Reference |

| Agree/strongly agree | 7.88 (5.13–12.69) | 6.20 (3.61–11.10) |

| “HIV/AIDS is a less serious threat than it used to be because of new treatments” | ||

| Strongly agree/agree | Reference | Reference |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 1.91 (1.39–2.63) | 1.42 (0.89–2.27) |

| Knowledge about pre-exposure prophylaxis | ||

| “I know enough about PrEP to tell if it’s right for me or not” | ||

| Strongly agree/agree/neutral | Reference | Reference |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 2.70 (1.82–4.12) | 2.33 (1.37–4.05) |

| Perceived effectiveness of PrEP at preventing HIV infection | ||

| Completely/very | Reference | Reference |

| Moderately/a little/not at all/no opinion | 8.44 (5.34–14.12) | 3.97 (2.23–7.38) |

| “New drug therapies make people less infectious with HIV” | ||

| Strongly agree/agree | Reference | Reference |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 2.52 (1.70–3.86) | 1.34 (0.75–2.42) |

| Dimensions related to seeking care | ||

| Impact of pre-exposure prophylaxis use on sexual behaviour | ||

| “I will choose my sexual partners based on whether they are taking PrEP or not” | ||

| Strongly agree/agree/neutral | Reference | Reference |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 1.48 (1.10–1.98) | 1.56 (1.02–2.41) |

| “If I was taking PrEP, I would most likely stop using condoms” | ||

| Strongly agree/agree/neutral | Reference | Reference |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 2.69 (1.94–3.78) | 1.99 (1.27–3.14) |

| “I am afraid that guys being on PrEP will stop using other ways of protecting themselves” | ||

| Strongly disagree/disagree/neutral | Reference | Reference |

| Agree/strongly agree | 1.93 (1.40–2.65) | 1.00 (0.63–1.59) |

| Dimensions related to accessing and paying for care | ||

| Access to health care services | ||

| Told primary health care provider about male partners | ||

| Yes | Reference | Reference |

| No | 5.68 (3.38–10.14) | 3.30 (1.68–6.76) |

| No primary care provider | 3.65 (2.62–5.13) | 2.66 (1.65–4.35) |

| Has medication insurance | ||

| Yes | Reference | Reference |

| No | 3.21 (2.26–4.65) | 3.10 (1.91–5.12) |

| “I don’t think I can find a doctor that is sensitive and accepting enough of my sexual activities and choices to prescribe PrEP” | ||

| Strongly disagree/disagree/neutral | Reference | Reference |

| Agree/strongly agree | 7.27 (3.27–20.57) | 5.22 (2.00–16.64) |

| “I know where to go to get a prescription for PrEP” | ||

| Strongly agree/agree/neutral | Reference | Reference |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 4.13 (2.84–6.19) | 1.63 (0.97–2.76) |

| “I have not sought a prescription for PrEP in the past because of the cost of the medication” | ||

| Strongly disagree/disagree/neutral | Reference | Reference |

| Agree/strongly agree | 1.43 (1.06–1.94) | 1.55 (1.00–2.41) |

| Dimensions related to engaging in care | ||

| Implications of ongoing use of pre-exposure prophylaxis | ||

| “I am worried about the short- and long-term side effects of taking PrEP” | ||

| Strongly disagree/disagree/neutral | Reference | Reference |

| Agree/strongly agree | 2.19 (1.63–2.94) | 1.81 (1.18–2.79) |

| “I don’t like the idea of being required to go to the regular medical follow-up visits involved in taking PrEP” | ||

| Strongly disagree/disagree/neutral | Reference | Reference |

| Agree/strongly agree | 3.03 (1.94–4.94) | 1.23 (0.67–2.31) |

| City and year of recruitment | ||

| City | ||

| Vancouver | Reference | Reference |

| Toronto | 1.03 (0.70–1.53) | 1.42 (0.81–2.52) |

| Montréal | 1.49 (1.07–2.08) | 1.07 (0.62–1.86) |

| Year | ||

| 2019 | Reference | Reference |

| 2018 | 1.37 (0.94 –2.00) | 1.96 (1.09–3.52) |

| 2017 | 2.26 (1.48–3.43) | 1.97 (1.01–3.87) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio, PrEP = pre-exposure prophylaxis.

All estimates are respondent-driven sampling (RDS)-adjusted.

Other variables that were explored included sexual orientation, ethnicity, other HIV prevention strategies (seropositioning, serosorting, PrEP, withdrawal), impact of PrEP use on sexual behaviour (“PrEP would allow me to have the sex I want,” “If a guy is using PrEP it makes using condoms during anal sex less important”), community receptivity of PrEP (“PrEP is well-perceived in the community,” “I am worried about being negatively judged for taking PrEP”), access to health care services (ease of accessing PrEP, “Clinics where I could get PrEP are too far away,” “Most doctors do not know enough about PrEP to be comfortable prescribing it”), implications of ongoing use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (“I would have difficulty taking PrEP medication every day”), HIV treatment optimism–skepticism scale,45 Collective Self-esteem Scale,46 Sexual Compulsivity Scale,47 sexual altruism scale48,49 and Condom Barriers Scale.50

Participants had higher odds of not using PrEP if they thought they were unable to find a doctor accepting of their sexual behaviours to prescribe PrEP (adjusted OR 5.22, 95% CI 2.00–16.64). Compared to participants who disclosed having male sexual partners to a primary care provider, those who did not disclose (adjusted OR 3.30, 95% CI 1.68–6.76) and those who did not have a care provider (adjusted OR 2.66, 95% CI 1.65–4.35) had higher odds of not using PrEP. Also, not having medication insurance (adjusted OR 3.10, 95% CI 1.91–5.12), being concerned about the cost of PrEP (adjusted OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.00–2.41) and worrying about adverse effects of PrEP (adjusted OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.18–2.79) were associated with nonuse.

Compared to recruitment in 2019, recruitment in 2017 (adjusted OR 1.97, 95% CI 1.01–3.87) and recruitment in 2018 (adjusted OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.09–3.52) were associated with higher odds of not using PrEP.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses gave similar results as the primary analyses. When we used the independent variables as continuous measures, minor changes occurred with respect to statistically significant factors: although worry about adverse effects of PrEP was no longer significant, not liking the idea of regular PrEP follow-up visits was significant (data not shown). The multivariable model without RDS adjustment had the following differences: being in a relationship with a main partner and not knowing enough about PrEP were no longer significantly associated with not using PrEP. In addition, participants who worried that “guys being on PrEP will stop using other ways of protecting themselves” and those who did not know where to get a prescription for PrEP were significantly more likely to not use PrEP.

Interpretation

Using the Canadian HIV PrEP clinical guideline9 and baseline data from the Engage cohort study, we estimated that about half of HIV-negative or HIV-unknown GBM in Montréal, Toronto and Vancouver could benefit from PrEP. We also found that 4 of 5 GBM who met clinical recommendations did not use PrEP.

Similarly low uptake of PrEP among GBM has previously been observed.23,41 In a study of 20 urban areas in the United States (2014 and 2017), only 1 in 3 men thought to benefit from PrEP reported using it.23 Although the majority of GBM in our study (84.6% in Montréal to 94.2% in Toronto) were aware of PrEP, fewer had perceived a need for it or had tried to obtain it. Our findings of participants’ not feeling at sufficient risk and not knowing whether PrEP was appropriate and effective are consistent with previous studies.21,41–43,51–53 The discordance between these perceptions and being at risk for HIV stands out as a target in optimizing access. Perceived risk is a known determinant of health behaviours54 and can be harnessed in promoting behaviour change. These and other dimensions of access that we identified align with literacy on the prevention and care aspects of PrEP. HIV PrEP literacy, or health literacy, encompasses health-related knowledge, personal motivation to access health information, peer norms and behavioural intentions. These are important determinants of a person’s ability to perceive a need and ultimately access a service.20,55 Improving access to PrEP should build on components of PrEP literacy, providing related information to individuals and communities.40 Perceived need, a function of both knowledge about PrEP and one’s perceptions about personal HIV risk,20 could be reinforced for GBM considered most at risk for HIV. Therefore, community information campaigns and peer-based programs could be used to guide GBM regarding the scope of their HIV risk and the potential benefits of PrEP. This could ultimately affect motivations to use PrEP and create new community norms regarding prevention.17,56

Like other investigators,41,44 we observed several factors representing health care system and structural barriers to PrEP use, including not having medical insurance, not having a primary care provider and not being able to find a doctor accepting of sexual behaviours to prescribe PrEP. This last finding is consistent with qualitative work showing lower rates of PrEP use among GBM who had difficulty discussing risky sexual behaviours and PrEP use with health care providers.57,58 In the current study, GBM concerned about adverse effects were also less likely to use PrEP. Interventions such as community outreach to improve linkage and knowledge about PrEP care, and removal of medication cost could increase PrEP uptake.59–61 Finally, work is needed to improve PrEP awareness among primary care networks, including continuing professional development programs on PrEP and general sexual health for GBM.62

Limitations

Although RDS is a useful sampling method, some subgroups of GBM may be over- or underrepresented. Participation in Engage is also limited to people who identify and live as men, therefore excluding trans women. In addition, the cash incentive may have contributed to a selection bias, especially among men with low incomes. However, when asked about the main reasons for participating, only 9% (Toronto) to 11% (Montréal) of participants reported being interested in the incentive (Appendix 3, Table S4). The availability of PrEP varied across cities, with 25% of Vancouver participants recruited before it was officially available (2018). Therefore, use of PrEP in Vancouver may be underestimated.

The proportion of GBM who met clinical recommendations may have been overestimated based on guideline criteria.9 For example, a man aged 18–28 who reports at least 1 episode of condomless receptive anal sex would meet recommendations. Partner type (regular v. casual) is not considered, which highlights the need for differentiated PrEP care.63 On the other hand, application of the current guideline9 seems to exclude those unlikely to benefit; the rate of PrEP use ranged from 1.5% (Montréal) to 7.6% (Vancouver) among men who did not meet clinical recommendations for PrEP (Appendix 3, Table S1). We considered overall use of PrEP, making no distinction between continuous or “on-demand” use; it is unknown whether correlates vary depending on the regimen.

Conducting an analysis on a multicity study with the use of RDS presents some challenges.30 However, we adhered to RDS assumptions by providing city-specific descriptive results, recognizing 3 distinct networks, and we included the RDS-II weights in regression models to minimize selection bias. Although there is no consensus on the use of RDS weights in regression analyses, recent work by members of our team suggests that weighted logistic regression consistently outperforms unweighted models in terms of bias and precision when predictors are correlated with participants’ network size (unpublished data, 2020). Indeed, the majority of the predictors we included in the multivariable model were significantly associated with network size.

Finally, although we cannot exclude social desirability and recall biases in the self-reported measures, the use of computer-assisted self-interviewing would largely mitigate these biases.64,65 Also, because of the cross-sectional nature of the analysis, temporality could not be established, and the results are generalizable only to GBM living in large urban centres.

Conclusion

Although the optimal target for PrEP coverage in the GBM population is unknown, our findings suggest sub-optimal coverage. By considering a variety of barriers to PrEP use, we identified specific gaps and challenges shared by GBM in Canada’s 3 largest cities. Our findings represent a snapshot of PrEP use among GBM as this prevention intervention begins to be used; our finding of higher odds of PrEP access in more recent recruitment years suggests evolving access and a need to follow uptake longitudinally. The epidemiologic features of HIV infection among GBM in Canada, along with the availability of PrEP, highlight the urgency to act. If HIV infection is to be eliminated as a public health threat by 2030 in Canada, informed, formal scale-up in access to PrEP for GBM is needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Engage study participants, office staff and community engagement committee members, as well as their community partner agencies.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Joseph Cox, Herak Apelian, Marc Messier-Peet and Gilles Lambert report nonfinancial support from the Direction régionale de santé publique, Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux Centre-Sud-de-l’Ile-de-Montréal. Joseph Cox reports grants and personal fees from ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences Canada, and personal fees from Merck Canada, outside the submitted work. David Moore reports a grant from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. Nathan Lachowsky reports grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research, Canadian Blood Services, the Vancouver Island Health Authority, the Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research, Gilead Sciences Canada, the Vancouver Foundation, the Public Health Agency of Canada, the University of Victoria and Mitacs, outside the submitted work. Darrell Tan reports a grant from the Canada Research Chairs Program; and grants from AbbVie and Gilead Sciences, outside the submitted work. He has been a site principal investigator for clinical trials sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Cecile Tremblay reports grants and personal fees from Gilead Sciences, Merck and ViiV Healthcare, outside the submitted work. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Joseph Cox and Herak Apelian contributed equally to this work. Joseph Cox, Gilles Lambert, Trevor Hart, Daniel Grace, David Moore, Nathan Lachowsky and Jody Jollimore conceived of and designed the study. Herak Apelian analyzed the data. Joseph Cox, Herak Apelian, Gilles Lambert, Erica Moodie and Marc Messier-Peet interpreted the data. Joseph Cox and Herak Apelian drafted the manuscript. All of the authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. The Engage study is led by the following principal investigators (in alphabetical order): Joseph Cox, Daniel Grace, Trevor Hart, Jody Jollimore, Nathan Lachowsky, Gilles Lambert and David Moore.

Funding: Engage/Momentum II is funded by grants TE2-138299, FDN=143342 and PJT-153139 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), grant CTN300 from the CIHR Canadian HIV/AIDS Trials Network, the Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research, grant 1051 from the Ontario HIV Treatment Network, grant 4500370314 from the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec.

Data sharing: De-identified participant data used in this analysis are stored at the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS. For information regarding these databases and related access, please contact the corresponding author.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/2/E529/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Summary: estimates of HIV incidence, prevalence and Canada’s progress on meeting the 90-90-90 HIV targets, 2016. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2018. [accessed 2020 Apr. 11]. Available: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/diseases-conditions/summary-estimates-hiv-incidence-prevalence-canadas-progress-90-90-90/pub-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haddad N, Robert A, Weeks A, et al. HIV in Canada — surveillance report, 2018. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2019;45:304–12. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v45i12a01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee H, Colyer S, Armstrong HL, et al. Trends in HIV diagnoses by age and ethnicity among men who have sex with men (MSM) in British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec: 2006–2015 Celebrating our diversity: uniting in the response to HIV. Proceedings from the 27th Annual Canadian Conference on HIV/AIDS Research; 2018 Apr 26–29; Vancouver. [accessed 2020 July 27]. Available: https://www.cahr-acrv.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/CAHR2018-Abstract-Book-with-Errata.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Census in brief: same-sex couples in Canada in 2016. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2017. [accessed 2020 Feb. 28]. Cat no 98-200-X. Available: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016007/98-200-x2016007-eng.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The epidemiology of HIV in gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. Toronto: CATIE; 2018. [accessed 2020 Feb. 28]. Available: https://www.catie.ca/sites/default/files/fs-epi-gbmsm-EN-2018-09-07.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sagaon-Teyssier L, Suzan-Monti M, Demoulin B, et al. Uptake of PrEP and condom and sexual risk behavior among MSM during the ANRS IPERGAY trial. AIDS Care. 2016;28(Suppl 1):48–55. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1146653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387:53–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hare CB, Coll J, Ruane P, et al. The phase 3 Discover study: daily F/TAF or F/TDF for HIV preexposure prophylaxis [abstract]. New options and opportunities in PrEP; Proceedings from the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2019 Mar 4–7; Seattle. [accessed 2020 July 29]. Available: https://www.croiconference.org/abstract/phase-3-discover-study-daily-ftaf-or-ftdf-hiv-preexposure-prophylaxis/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan DHS, Hull MW, Yoong D, et al. Canadian guideline on HIV preexposure prophylaxis and nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis. CMAJ. 2017;189:E1448–58. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.PrEP in Canada. What do we know about awareness, acceptability and use? Toronto: CATIE; 2017. [accessed 2020 Feb. 28]. Available: https://www.catie.ca/en/pif/spring-2017/prep-canada-what-do-we-know-about-awareness-acceptability-and-use. [Google Scholar]

- 11.La PrEP. Montréal: RÉZO; [accessed 2020 Feb. 28]. Available: https://www.rezosante.org/ta-sexualite/prevention/prep. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rates in effect. Québec City: Government of Quebec; 2020. [accessed 2020 Feb. 28]. Prescription drug insurance. Available: https://www.ramq.gouv.qc.ca/en/citizens/prescription-drug-insurance/Pages/rates_effect.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pre-exposure prophylaxis to the human immunodeficiency virus: guide for health professionals in Quebec [article in French] Québec City: Government of Quebec; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Interim opinion: on human immunodeficiency virus pre-exposure prophylaxis [article in French] Québec City: Government of Quebec; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.PrEP in Ontario: update for community. Toronto: AIDS Committee of Toronto; 2017. [accessed 2020 Apr. 11]. Available: https://www.actoronto.org/health-information/sexual-health/prep-info/prepontario.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guidance for the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for the prevention of HIV acquisition in British Columbia. Vancouver: British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS; 2019. [accessed 2020 Feb. 28]. Available: http://www.cfenet.ubc.ca/publications/centre-documents/guidance-for-the-use-pre-exposure-prophylaxis-prep-prevention-hiv-acquisition. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaefer R, Gregson S, Fearon E, et al. HIV prevention cascades: a unifying framework to replicate the successes of treatment cascades. Lancet HIV. 2019;6:e60–6. doi: 10.1016/s2352-3018(18)30327-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelley CF, Kahle E, Siegler A, et al. Applying a PrEP continuum of care for men who have sex with men in Atlanta, Georgia. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:1590–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newman PA, Guta A, Lacombe-Duncan A, et al. Clinical exigencies, psychosocial realities: negotiating HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis beyond the cascade among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in Canada. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21:e25211. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:18. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lachowsky NJ, Lawson Tattersall T, Sereda P, et al. Community awareness of, use of and attitudes towards HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men in Vancouver, Canada: preparing health promotion for a publicly funded PrEP program. Sex Health. 2019;16:180–6. doi: 10.1071/SH18115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilton J, Kain T, Fowler S, et al. Use of an HIV-risk screening tool to identify optimal candidates for PrEP scale-up among men who have sex with men in Toronto, Canada: disconnect between objective and subjective HIV risk. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19:20777. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finlayson T, Cha S, Xia M, et al. Changes in HIV preexposure prophylaxis awareness and use among men who have sex with men — 20 urban areas, 2014 and 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:597–603. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6827a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosley T, Khaketla M, Armstrong HL, et al. Trends in awareness and use of HIV PrEP among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Vancouver, Canada 2012–2016. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:3550–65. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2026-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenwald ZR, Maheu-Giroux M, Szabo J, et al. Cohort profile: l’Actuel Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Cohort study in Montreal, Canada. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e028768. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doyle CM, Maheu-Giroux M, Lambert G, et al. Combination HIV prevention strategies among Montreal gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in the PrEP era: a latent class analysis. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:269–83. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02965-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delaunay CL, Cox J, Klein M, et al. Trends in hepatitis C virus seroprevalence and associated risk factors among men who have sex with men in Montréal: results from three cross-sectional studies (2005, 2009, 2018) Sex Transm Infect. 2020 Jul 23; doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054464. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L, Moqueet N, Lambert G, et al. Population-level sexual mixing according to HIV status and preexposure prophylaxis use among men who have sex with men in Montreal, Canada: implications for HIV prevention. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;189:44–54. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwz231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Introduction to HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infection surveillance: module 4 introduction to respondent-driven sampling. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [accessed 2020 Feb. 28]. Available https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/116864. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gile KJ, Beaudry IS, Handcock MS, et al. Methods for inference from respondent-driven sampling data. Annu Rev Stat Appl. 2018;5:65–93. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Volz E, Heckathorn DD. Probability based estimation theory for respondent driven sampling. J Off Stat. 2008;24:79. [Google Scholar]

- 32.White RG, Hakim AJ, Salganik MJ, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology for respondent-driven sampling studies: “STROBE-RDS” statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:1463–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivankovich MB, Fenton KA, Douglas JM. Considerations for national public health leadership in advancing sexual health. Public Health Rep. 2013;128(Suppl 1):102–10. doi: 10.1177/00333549131282S112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singer M. Introduction to syndemics: a critical systems approach to public and community health. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 27–41.pp. 199–221. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santos GM, Do T, Beck J, et al. Syndemic conditions associated with increased HIV risk in a global sample of men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90:250–3. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.M-Track: enhanced surveillance of HIV, sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections, and associated risk behaviours among men who have sex with men in Canada. Phase 1 report. Ottawa: Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control; 2011. [accessed 2020 May 27]. Available: https://www.deslibris.ca/ID/232461. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gallagher KM, Sullivan PS, Lansky A, et al. Behavioral surveillance among people at risk for HIV infection in the U.S.: the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 1):32–8. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith DK, Pals SL, Herbst JH, et al. Development of a clinical screening index predictive of incident HIV infection among men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:421–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318256b2f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States — 2017 update: a clinical practice guideline. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. [accessed 2020 Apr. 3]. Available: www.cfenet.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/centredocs/prep_guidelines-14-aug-2019.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dubov A, Altice FL, Fraenkel L. An information–motivation–behavioral skills model of PrEP uptake. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:3603–16. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2095-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hannaford A, Lipshie-Williams M, Starrels JL, et al. The use of online posts to identify barriers to and facilitators of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men: a comparison to a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:1080–95. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-2011-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krakower DS, Mimiaga MJ, Rosenberger JG, et al. Limited awareness and low immediate uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men using an Internet social networking site. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gallagher T, Link L, Ramos M, et al. Self-perception of HIV risk and candidacy for pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men testing for HIV at commercial sex venues in New York City. LGBT Health. 2014;1:218–24. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maxwell S, Gafos M, Shahmanesh M. Pre-exposure prophylaxis use and medication adherence among men who have sex with men: a systematic review of the literature. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2019;30:e38–61. doi: 10.1097/JNC.0000000000000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ven PVD, Crawford J, Kippax S, et al. A scale of optimism–scepticism in the context of HIV treatments. AIDS Care. 2000;12:171–6. doi: 10.1080/09540120050001841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herek GM, Glunt EK. Identity and community among gay and bisexual men in the AIDS era: preliminary findings from the Sacramento Men’s Health Study. In: Herek GM, Greene B, editors. AIDS, identity, and community. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publishing; 1995. pp. 55–84. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalichman SC, Rompa D. The Sexual Compulsivity Scale: further development and use with HIV-positive persons. J Pers Assess. 2001;76:379–95. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7603_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nimmons D, Folkman S. Other-sensitive motivation for safer sex among gay men: expanding paradigms for HIV prevention. AIDS Behav. 1999;3:313–24. [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Dell BL, Rosser BRS, Miner MH, et al. HIV prevention altruism and sexual risk behavior in HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:713–20. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9321-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doyle SR, Calsyn DA, Ball SA. Factor structure of the Condoms Barriers Scale with a sample of men at high risk for HIV. Assessment. 2009;16:3–15. doi: 10.1177/1073191108322259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Whitfield THF, et al. Familiarity with and preferences for oral and long-acting injectable HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a national sample of gay and bisexual men in the U.S. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:1390–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1370-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Bacon O, et al. High interest in preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men at risk for HIV infection: baseline data from the US PrEP Demonstration Project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68:439–48. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uthappa CK, Allam R, Pant R, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis: awareness, acceptability and risk compensation behaviour among men who have sex with men and the transgender population. HIV Med. 2018;19:243–51. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000;15:259–67. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carson B. The informal norms of HIV prevention: the emergence and erosion of the condom code. J Law Med Ethics. 2017;45:518–30. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Underhill K, Morrow KM, Colleran C, et al. A qualitative study of medical mistrust, perceived discrimination, and risk behavior disclosure to clinicians by U.S. male sex workers and other men who have sex with men: implications for biomedical HIV prevention. J Urban Health. 2015;92:667–86. doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-9961-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wade Taylor S, Mayer KH, Elsesser SM, et al. Optimizing content for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) counseling for men who have sex with men: perspectives of PrEP users and high-risk PrEP naive men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:871–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0617-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krishnaratne S, Hensen B, Cordes J, et al. Interventions to strengthen the HIV prevention cascade: a systematic review of reviews. Lancet HIV. 2016;3:e307–17. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hargreaves JR, Delany-Moretlwe S, Hallett TB, et al. The HIV prevention cascade: integrating theories of epidemiological, behavioural, and social science into programme design and monitoring. Lancet HIV. 2016;3:e318–22. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pinto RM, Berringer KR, Melendez R, et al. Improving PrEP implementation through multilevel interventions: a synthesis of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:3681–91. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2184-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sharma M, Chris A, Chan A, et al. Decentralizing the delivery of HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) through family physicians and sexual health clinic nurses: a dissemination and implementation study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:513. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3324-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grimsrud A, Bygrave H, Doherty M, et al. Reimagining HIV service delivery: the role of differentiated care from prevention to suppression. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19:21484. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.1.21484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reichmann WM, Losina E, Seage GR, et al. Does modality of survey administration impact data quality: Audio computer assisted self-interview (ACASI) versus self-administered pen and paper? PLoS One. 2010;5:e8728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gribble JN, Miller HG, Rogers SM, et al. Interview mode and measurement of sexual behaviors: methodological issues. J Sex Res. 1999;36:16–24. doi: 10.1080/00224499909551963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.