Abstract

Background:

Posttranslational histone modifications play a critical role in the regulation of gene transcription underlying synaptic plasticity and memory formation. One such epigenetic change is histone ubiquitination, a process that is mediated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system in a manner similar to that by which proteins are normally targeted for degradation. However, histone ubiquitination mechanisms are poorly understood in the brain and in learning. In this article, we describe a new role for the ubiquitin-proteasome system in histone cross-talk, showing that learning-induced monoubiquitination of histone H2B (H2Bubi) is required for increases in the transcriptionally active H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) mark at learning-related genes in the hippocampus.

Methods:

Using a series of molecular, biochemical, electrophysiological, and behavioral experiments, we interrogated the effects of short interfering RNA–mediated knockdown and CRISPR-mediated upregulation of ubiquitin ligases, deubiquitinating enzymes and histone methyltransferases in the rat dorsal hippocampus during memory consolidation.

Results:

We showed that H2Bubi recruits H3K4me3 through a process that is dependent on the 19S proteasome subunit RPT6 and that a loss of H2Bubi in the hippocampus prevents learning-induced increases in H3K4me3, gene transcription, synaptic plasticity, and memory formation. Furthermore, we show that CRISPR-dCas9-mediated increases in H2Bubi promote H3K4me3 and memory formation under weak training conditions and that promoting histone methylation does not rescue memory impairments resulting from loss of H2Bubi.

Conclusion:

These results suggest that H2B ubiquitination regulates histone cross-talk in learning by way of non-proteolytic proteasome function, demonstrating a novel mechanism by which histone modifications are coordinated in response to learning.

Keywords: histone, methylation, ubiquitination, proteasome, epigenetics, memory

Introduction

Chromatin remodeling mechanisms are widely implicated in the transcriptional control of synaptic plasticity and memory formation (1–6). The best studied of these mechanisms are the post-translational modifications to histone proteins, which can activate or repress transcription of genes necessary for long-term memory formation or consolidation. For example, histone H3 lysine methylation has been shown to regulate both gene activation and repression during memory formation depending on which lysine residue is methylated (7, 8). One of these methylation marks is H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), which is normally enriched at genes that are being actively transcribed and is considered a marker of increased transcription. Interestingly, not only is H3K4me3 involved in normal memory formation, but dysregulation of this mark is also associated with multiple psychiatric disorders (9–11). However, the means by which the H3K4me3 mark and its methyltransferase, MLL1, are recruited to specific DNA regions in the brain following learning remain unknown. Moreover, while epigenetic modifications often work in concert to regulate transcription during activity-dependent synaptic plasticity (12), little is known about how this histone “cross-talk” is coordinated in the brain.

In addition to the better-understood acetylation and methylation modifications, histones can also be ubiquitinated (13). Histone ubiquitination occurs through the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) in the same manner by which proteins are normally targeted for degradation, except that histone proteins generally only receive a single ubiquitin tag (14, 15). The proteasome has lower affinity for monoubiquitin tags, thus sparing these proteins from degradation. Instead, histone monoubiquitination controls DNA accessibility to transcription factors. The most common histone ubiquitination tag is monoubiquitination of H2B at lysine 120 (H2BubiK120). Evidence from single-cell organisms and cancer cells suggest that H2BubiK120 (H2BubiK119 in yeast) controls transcription by recruiting the H3K4me3 mark, thus promoting active transcriptional control (13, 16–18). However, histone ubiquitination mechanisms are not well understood in the brain, and it is unknown whether H2B ubiquitination is involved in the recruitment of H3 lysine methylation during learning-dependent synaptic plasticity.

In this study, we tested whether H2BubiK120 controls histone cross-talk mechanisms during memory formation. We found that H2B ubiquitination controls learning-dependent synaptic plasticity by recruiting H3K4me3 in a gene-specific manner. This process requires the 19S proteasome subunit RPT6, which acts independently of the 26S proteasome, forming a complex with H2BubiK120 to recruit H3K4me3. Collectively, these findings reveal a new process for coordinating histone modifications during memory formation and identify a new, non-proteolytic role for the UPS in the brain.

Methods and Materials

Subjects

A total of 225 male and 10 female 8–9 week old Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan) were used for these experiments. See SI for expanded methods.

Cranial Infusion of siRNA and Plasmids

Region-specific knockdown of target genes was achieved by cranial infusion of short interfering RNA (siRNA) according to previously described stereotactic surgery protocols (19–21). In like manner, cranial infusions were used to achieve region-specific, in vivo transfection of CRISPR guide RNA and/or dCas9 DNA plasmids. See SI for expanded methods and cloning protocols.

Behavioral Procedures

Rats were trained and tested to a contextual fear-conditioning paradigm as described previously (19–21). See SI for expanded methods.

Tissue Preparation

The CA1 region of the dorsal hippocampus was collected and sub-dissected as described previously (19–21). See SI for expanded methods.

Antibodies, Immunohistochemistry, and Western Blot

A list of all antibodies used is provided in the expanded methods (see SI) along with standard immunohistochemical and Western blot protocols.

Protein Immunoprecipitation

Normalized protein extracts were and incubated with primary antibody (αH2BubiK120, RPT6) or control (IgG) overnight at 4°C, mixed with Pierce Magnetic Protein A/G beads (Thermo Fisher) for 1 hr at 4°C, extensively washed, eluted at 95°C for 5 min and imaged as described in the SI expanded methods.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA and DNA were extracted from area CA1 using the Qiagen Allprep Kit. RNA (200ng) was converted to cDNA using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Biorad) and RT-PCR amplifications for Rnf20, Rnf40, Egr1, c-fos, and Bdnf were performed on the CFX96 or IQ5 real-time PCR system (Biorad). Primers and analysis can be found in the expanded methods section (see SI).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIP) were performed as described previously (20, 21). See SI for expanded methods.

Bioinformatics

Publicly-available data were collected from NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus for the following sources and antibody targets: USF1 binding sites were determined using previously-published ChIP-seq data collected for project ENCODE in human brain SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells treated with trans-retinoic acid for differentiation into a neuronal phenotype (GEO: GSE32465, sample GSM803472) (22). H3K4me3 enrichment was determined using previously-published ChIP-seq data collected for the Broad Institute’s Human Reference Epigenome Mapping Project in human hippocampal tissue (GEO: GSE19465, sample GSM670022)(23). See SI for expanded methods.

Electrophysiology

Electrophysiological studies were performed according to the specifications outlined in the expanded methods (see SI).

Statistical Analyses

Outliers were defined as those falling two standard deviations from the group mean using the Outlier function in Prism software. For behavioral data, if an animal was determined to be an outlier during training or testing, they were removed from both analyses since the two measures are not independent. All data are presented as group averages with standard error of the mean and analyzed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Fisher Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc tests or pairwise t-tests as indicated in the figure legends.

Results

H2B ubiquitination is increased following learning

We first examined whether H2BubiK120 levels changed in response to learning. Immunofluorescent imaging showed a qualitative increase in H2BubiK120 in area CA1 of the dorsal hippocampus 1 hr after contextual fear conditioning (Fig 1A), so we quantified H2BubiK120 in bulk histone extracts collected from area CA1 1 hr after fear conditioning and compared them to naïve animals or animals exposed to the context and shock in a non-associative manner. We found significant increases in H2BubiK120 levels in area CA1 of fear-conditioned animals relative to naïve and immediate-shock controls (Fig 1B) which was learning-specific and absent in other regions involved in fear memory consolidation (Fig. S1), suggesting a specific role in the dorsal hippocampus. Notably, we observed similar H2BubiK120 increases in area CA1 of female rats (Figure S2), but did not observe a learning-induced increase in monoubiquitination of H2A at lysine 119 (H2AubiK119) (Fig. 1C), a finding that suggests a sex-independent role for H2BubiK120 in the memory consolidation process. The increases in H2BubiK120 returned to baseline 24 hrs after training (Fig. 1D), suggesting that changes to this epigenetic mark occurred and resolved during the memory consolidation process. These results suggest that H2BubiK120 is transiently increased in area CA1 as a result of learning and may be involved in memory consolidation.

Figure 1. Histone H2B ubiquitination is increased in the hippocampus following learning.

Animals were trained on a contextual fear conditioning protocol and the CA1 region of the dorsal hippocampus was collected 1 hr later. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images from a naïve (top) and fear conditioned (bottom) animal showing a qualitative increase in H2BubiK120 staining throughout the CA1 region of the dorsal hippocampus following learning. (B) Western blot analysis of bulk histone extracts collected from the dorsal CA1 region revealed a selective increase in H2BubiK120 in fear conditioned animals (CFC) vs naïve controls (two-tailed t-test, t9 = 2.460, P = 0.0361, n = 5–6 per group) in comparison to immediate shock controls vs naïve controls (two-tailed t-test, t8 = 0.2450, P = 0.8126, n = 5 per group). (C) H2AubiK119 levels were not increased in fear conditioned animals vs naïve controls (two-tailed t-test, t9 = 0.8562, P = 0.4141, n = 5–6 per group) or immediate shock controls vs naïve controls (two-tailed t-test, t8 = 0.5352, P = 0.6071, n = 5 per group). (D) H2BubiK120 levels returned to baseline 24 hrs after training (two-tailed t-test, t4 = 0.2147, P = 0.8405, n = 3 per group). * P < 0.05 from Naïve.

H2B ubiquitination regulates H3 methylation during memory formation

Next, we tested whether H2BubiK120 influenced histone methylation marks following learning. We infused a siRNA targeting the H2B ubiquitin ligase Rnf20 into area CA1 5 days before fear conditioning and collected bulk histones from that area 1 hr after training (Fig. 2A, S3, S4). Learning-induced increases in H2BubiK120 were lost following Rnf20 knockdown (Fig. 2B), confirming that Rnf20 knockdown was sufficient to prevent H2BubiK120. Remarkably, learning-induced increases in H3K4me3 (Fig. 2C) were also abolished following Rnf20 knockdown. Consistent with this relationship, H3K4me3 co-precipitated with H2BubiK120 from CA1 bulk histone extracts (Fig. 2D). However, H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3; Fig. 2E) levels remained unchanged, suggesting that not all histone methylation modifications were altered with Rnf20 knockdown. Additionally, we observed a complete loss of learning-dependent H3 acetylation increases following Rnf20 knockdown (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, knockdown of the H3K4me3 methyltransferase Mll1 in area CA1 prior to fear conditioning selectively reduced H3K4me3, but not H2BubiK120, in area CA1 (Fig. S4), suggesting that the relationship between H2BubiK120 and H3K4me3 is not bidirectional. Collectively, these results suggest that H2BubiK120 is required for associated H3K4me3 changes during learning.

Figure 2. Loss of H2BubiK120 in area CA1 prevents learning-induced increases in global histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation following learning.

All statistics reported in this figure were computed using One-way ANOVA and Fisher LSD posthoc tests where appropriate. (A) Animals were injected with Accell siRNA targeting H2B ubiquitin ligase Rnf20 or control into the hippocampus 5 days prior to contextual fear conditioning. Area CA1 was collected 1 hr after completion of the training session. (B) Loss of Rnf20 prevented learning induced increases in H2BubiK120 levels in area CA1 (F(2,10) = 9.744, P = 0.0045, n = 4–5 per group). Arrow denotes H2BubiK120. Upper band likely represents antibody light chain. (C) Loss of Rnf20 prevented learning induced increases in H3K4me3 (c, F(2,10) = 4.333, P = 0.0441, n = 4–5 per group) in area CA1. (D) Immunopreciptation assay revealed that H3K4me3 co-precipitated with H2BubiK120 from CA1 histone lysates. (E-F) Loss of Rnf20 prevented learning-induced increases in H3 acetylation (F, F(2,11) = 6.038, P = 0.0170, n = 4–5 per group), but not H3K27me3 (E, F(2,11) = 6.496, P = 0.0137, n = 4–5 per group) levels in area CA1. * P < 0.05 from Scr-siRNA Naïve. # P < 0.05 from Rnf20-siRNA CFC.

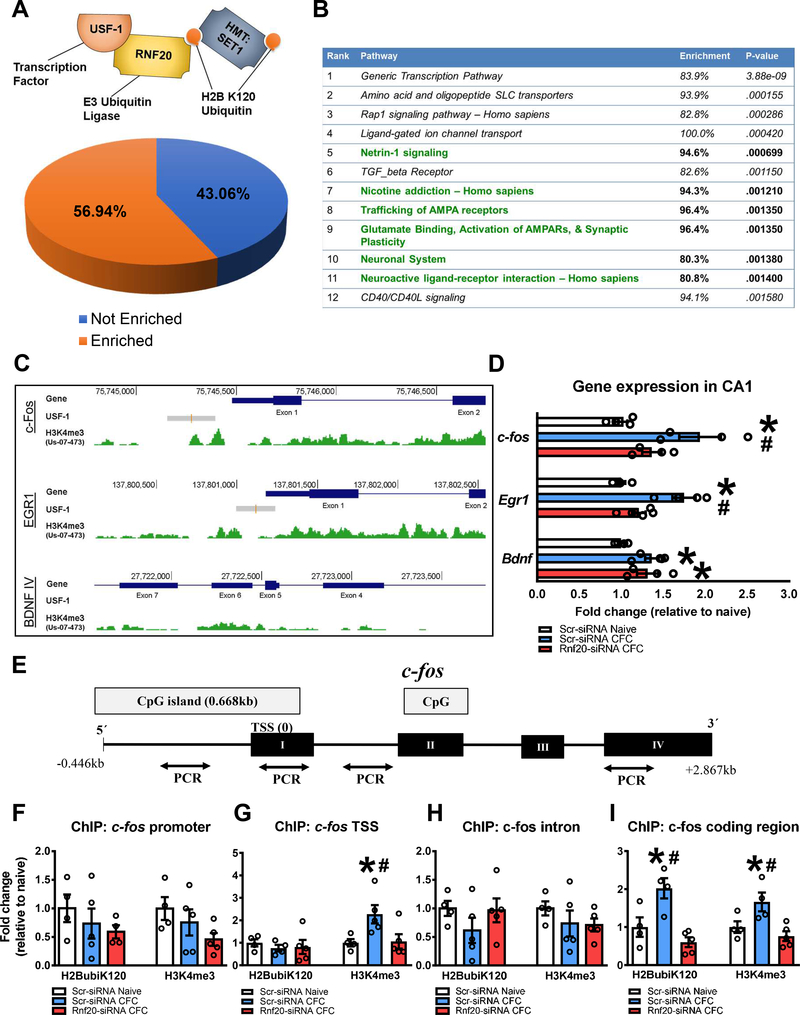

To further understand the relationship between H2BubiK120 and H3K4me3, we analyzed publicly available ChIP-seq datasets and overlapped enrichment sites for H3K4me3 and binding sites for USF1, which was used as a proxy for H2BubiK120 because it has been shown that this is required for the recruitment of histone ubiquitination (24) and there were no publicly available ChIP-seq datasets for H2BubiK120. We found that over 56% of genomic intervals enriched for USF1 were also enriched for H3K4me3 (Fig. 3A), suggesting a significant overlap between the H2BubiK120 and H3K4me3 marks. Gene set pathway analysis for genomic intervals enriched for both USF1 and H3K4me3 revealed several neurological functions, including synaptic plasticity (Fig. 3B). Next, three memory-related genes were visualized alongside USF1-binding and H3K4me3 enrichment sites. USF1 binding was determined by ChIP-seq performed in human brain SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells treated with trans-retinoic acid for differentiation into a neuronal phenotype, and H3K4me3 enrichment sites were identified by ChIP-seq analysis of human hippocampal tissue. We found that of three memory-permissive genes analyzed that were enriched for H3K4me3, Egr-1 and c-fos, but not Bdnf IV, were also enriched for USF1 (Fig. 3C). This was confirmed in area CA1 of fear-conditioned animals, where we found that Rnf20 knockdown prevented learning-induced increases in Egr-1 and c-fos, but not Bdnf IV (Fig. 3D and S5). These findings suggest that H2BubiK120 regulates the expression of some, but not all, H3K4me3-target genes during the memory consolidation process.

Figure 3. Loss of H2BubiK120 in area CA1 prevents learning-induced increases in gene-specific histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation following learning.

All statistics reported in this figure were computed using One-way ANOVA and Fisher LSD posthoc tests where appropriate. (A-C) Bioinformatic analysis of publicly available whole genome ChIP-Seq data comparing overlap of H3K4me3 peaks and binding sites for USF1, a binding partner of RNF20. The analysis revealed that more than 56% of USF1 binding sites were enriched with H3K4me3 (A) and regulated a number of different cellular processes, including synaptic plasticity (B). Analysis of three candidate genes critical for memory formation found that USF1 binding sites correlated with H3K4me3 peaks in the c-fos and Egr1, but not Bdnf IV, transcripts (C). (D) Knockdown of Rnf20 in the hippocampus prevented learning-induced increases in c-fos (F(2,10) = 15.60, P = 0.0008, n = 4–5 per group) and Egr1 (F(2,9) = 8.356, P = 0.0089, n = 4 per group), but not Bdnf IV (F(2,10) = 4.947, P = 0.0321, n = 4–5 per group), expression. (E) Diagram showing regions of the c-fos gene examined in ChIP studies. From left to right, primers targeted the c-fos promoter, transcription start site (TSS), intron or coding regions. (F-I) Learning increased H2BubiK120 levels in the c-fos coding (I, F(2,10) = 11.57, P = 0.0025, n = 4–5 per group), but not promoter (F, F(2,10) = 0.7830, P = 0.4832, n = 4–5 per group), TSS (G, F(2,11) = 0.2491, P = 0.7842, n = 4–5 per group) or intron (H, F(2,11) = 1.161, P = 0.3486, n = 4–5 per group), regions, which was lost following Rnf20 knockdown. H3K4me3 was increased in a learning-dependent manner in the c-fos TSS (F(2,11) = 4.736, P = 0.0328, n = 4–5 per group) and coding (F(2,10) = 6.939, P = 0.0129, n = 4–5 per group), but not promoter (F(2,11) = 2.051, P = 0.1749, n = 4–5 per group) or intron (F(2,11) = 0.8201, P = 0.4656, n = 4–5 per group), regions, both of which were lost following Rnf20 knockdown. * P < 0.05 from Scr-siRNA Naïve. # P < 0.05 from Scr-siRNA CFC.

Having identified potential target genes of H2BubiK120, we next used ChIP (Fig. S6) to determine whether H2BubiK120 and H3K4me3 levels were increased in area CA1 at the same gene regions following learning, using c-fos as a candidate gene (Fig. 3E). We found significant increases in H2BubiK120 in the c-fos coding region (Fig. 3I), but not the promoter (Fig. 3F), transcription start site (TSS; Fig. 3G), or intron regions (Fig. 3H) following learning, suggesting that H2BubiK120 is present at the more distal coding regions of its target gene. This enrichment was lost following Rnf20 knockdown. H3K4me3 was enriched in the c-fos TSS and coding regions, but not in the promoter or intron regions following learning, both of which were lost following Rnf20 knockdown. Finally, knockdown of the H3K4me3 methyltransferase Mll1 in area CA1 prior to fear conditioning resulted in redistribution—but not a loss—of H2BubiK120 (Fig. S7) enrichment, showing that H2BubiK120 changes occur upstream of H3K4me3. Collectively, these results suggest that H2BubiK120 recruits H3K4me3 to regulate gene transcription during fear memory formation.

H2B ubiquitination recruits H3 methylation via proteasome subunit RPT6 during memory formation

Our data strongly suggest that H2BubiK120 regulates H3K4me3 levels in area CA1 following fear conditioning. Accordingly, we asked how H2BubiK120 recruits H3K4me3 to DNA regions during the memory consolidation process. In yeast, the 19S proteasomal subunit SUG1 bridges H2BubiK120 to H3K4me3 (25); therefore, we tested whether the mammalian SUG1 homolog RPT6 (gene: Psmc5) is necessary for H2B-dependent recruitment of histone methylation during memory formation. First, we examined how learning alters the expression of the six RPT (ATPase) subunits of the 19S proteasome. Immunofluorescence (Fig. 4A) and whole genome RNA-sequencing analysis (Fig. S8) showed that only one subunit, RPT6, had decreased Psmc5 mRNA expression but increased RPT6 protein expression in area CA1 1 hr after fear conditioning, suggesting that expression of this proteasome RPT subunit alone is changed as a function of learning. To better understand how RPT6 expression changes following fear conditioning, we collected histone and cytoplasmic fractions from the CA1 regions of trained and naïve animals. We found that nuclear, but not cytoplasmic, RPT6 levels increased following learning (Fig. 4B and S7). Furthermore, co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that nuclear RPT6 associates with H2BubiK120 and both RNF20 isoforms, but not with RPT4 (Fig. 4C), suggesting that RPT6 forms a complex with H2BubiK120 that is independent of the 19S or 26S proteasome structure. Accordingly, ChIP experiments showed an increase in RPT6 enrichment at the c-fos coding region where we had previously found increased H2BubiK120, which was lost following Rnf20 knockdown (Fig. 4D). These findings further suggest that H2BubiK120 may recruit RPT6 to increase H3K4me3 during memory formation.

Figure 4. 19S proteasome subunit RPT6 is necessary for the H2BubiK120-dependent recruitment of H3K4me3 following learning.

(A) Immunofluorescence images showing a qualitative increase in the expression of RPT6 in dorsal CA1 1 hr after contextual fear conditioning. RPT6 (Psmc5) is in green, DAPI is blue. (B) Fear conditioning increased nuclear (two-tailed t-test, t10 = 2.364, P = 0.0397, n = 6 per group), but not cytoplasmic (two-tailed t-test, t10 = 0.1367, P = 0.8940, n = 6 per group), levels of RPT6 in area CA1. In representative western blot images, top box is RPT6 and bottom box is H3 (nuclear) or β-Actin (cytoplasmic). (C) Immunoprecipitation of RPT6 from CA1 nuclear extract resulted in co-precipitation of H2BubiK120 and RNF20, but not RPT4. (D) Learning increased RPT6 binding to the c-fos coding region, which was lost following Rnf20 knockdown (Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric ANOVA, H12 = 5.901, P = 0.0358, n = 4 per group). (E-H) Knockdown of the gene for RPT6, Psmc5, in the hippocampus prevented learning-induced increases in RPT6 (E, One way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(2,13) = 4.982, P = 0.0248, n = 5–6 per group), H3K4me3 (F, One way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(2,13) = 5.820, P = 0.0157, n = 5–6 per group), H2BubiK120 (G, One way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(2,13) = 3.638, P = 0.0556, n = 5–6 per group) and RNF20 (H, One way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(2,12) = 3.924, P = 0.0488, n = 5 per group) binding in the c-fos coding region. Psmc5 knockdown reduced H3K4me3 in the c-fos TSS (One way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(2,13) = 5.115, P = 0.0230, n = 5–6 per group) without altering RPT6 (One way ANOVA, F(2,11) = 1.793, P = 0.2118, n = 4–5 per group), H2BubiK120 (One way ANOVA, F(2,12) = 0.7674, P = 0.4857, n = 4–6 per group) or RNF20 (One way ANOVA, F(2,13) = 0.1460, P = 0.8656, n = 5–6 per group) in the same region. (I) Western blot analysis of reversed crosslinked ChIP tissue revealed that learning increased global H2BubiK120 (One-tailed t-test, t8 = 2.020, P = 0.0390, n = 5 per group) in the dorsal CA1 region, which was lost following Psmc5 knockdown (One-tailed t-test, t9 = 0.4802, P = 0.3213, n = 5–6 per group). In representative western blot images, top box is H2BubiK120 and bottom box is H3. (J) Western blot analysis of reversed crosslinked ChIP tissue revealed that learning increased global H3k4me3 (One-tailed t-test, t8 = 2.132, P = 0.0328, n = 5 per group) in the dorsal CA1 region, which was lost following Psmc5 knockdown (One-tailed t-test, t9 = 0.1151, P = 0.9109, n = 5–6 per group). (K) Psmc5 knockdown reduced c-fos expression in the dorsal CA1 region following learning (One-tailed t-test, t9 = 1.980, P = 0.0395, n = 5–6 per group). (L-M) Knockdown of Psmc5 in the hippocampus did not impair the ability of the animals to acquire the task (L, one-tailed t-test, t13 = 0.1954, P = 0.4240, n = 7–8 per group), but significantly impaired memory during the test day (M, one-tailed t-test, t13 = 1.853, P = 0.0433, n = 7–8 per group). * P < 0.05 from Naïve, Scr-siRNA Naïve or Scr-siRNA. # P < 0.05 from Psmc5-siRNA CFC.

To test whether RPT6 is necessary for learning-induced increases in H3K4me3 levels, we knocked down Psmc5 prior to fear conditioning and interrogated H2BubiK120, RPT6 and H3K4me3 binding throughout the TSS and coding regions of c-fos. We showed that transient Psmc5 knockdown selectively reduced RPT6 expression without altering proteasome activity (Fig. S9), as these changes might have impacted the protein degradation process. We found that knockdown of Psmc5 prevented learning-induced increases in RPT6 in the c-fos coding region (Fig. 4E), as well as H3K4me3 in the c-fos TSS and coding regions (Fig. 4F and S9), suggesting that RPT6 is necessary for recruiting H3K4me3 to specific gene regions during the memory consolidation process. Surprisingly, loss of RPT6 also prevented learning-induced increases in H2BubiK120 (Fig. 4G and S9) and RNF20 (Fig. 4H) in the c-fos coding region. While these results do support the idea that RPT6 plays a unique role in regulation of H3K4me3 during learning-dependent synaptic plasticity, the loss of H2BubiK120 following Psmc5 knockdown was unexpected. To investigate this further, we reverse-crosslinked ChIP samples and examined global levels of H2BubiK120 and H3K4me3 using western blot analysis. Consistent with our ChIP data, Psmc5 knockdown resulted in a global loss of both H2BubiK120 (Fig. 4I) and H3K4me3 (Fig. 4J) following learning. In combination with our Rnf20 data, these findings suggest that H2BubiK120 recruits RPT6 to both regulate H3K4me3 recruitment and stabilize a RNF20-H2BubiK120-H3K4me3 complex that is critical for gene transcription and memory formation. Accordingly, loss of Psmc5 reduced c-fos expression following learning (Fig. 4K and S9) and impaired long-term memory (Fig. 4L–M). Altogether, these results show that H2BubiK120 recruits H3K4me3 via RPT6 to regulate active gene transcription in area CA1 in a way that is necessary for memory formation.

H2B ubiquitination is critical for activity- and learning-dependent synaptic plasticity

We next tested the functional significance of increased H2BubiK120 after learning by examining long-term memory retention following Rnf20 knockdown (Fig. 5A). We found that while Rnf20 knockdown did not affect the ability of the animals to acquire the fear conditioning task (Fig. 5B), it significantly impaired long-term memory in a later test (Fig. 5C), suggesting that increased H2BubiK120 is critical for memory consolidation. Additionally, we found that in vivo knockdown of Rnf20 impaired hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP; Fig. 5D), but did not alter basal synaptic transmission (Fig. 5E), leaving presynaptic plasticity largely intact (Fig. 5F). These results suggest that H2BubiK120 is a critical regulator of synaptic plasticity and memory formation in the hippocampus.

Figure 5. Loss of H2BubiK120 impairs activity-dependent synaptic plasticity and long-term memory formation.

(A) Animals were injected with Accell siRNA targeting Rnf20 or control into the CA1 region of the dorsal hippocampus. Five days later, animals were either trained to contextual fear conditioning and tested 24 hrs later or animals were euthanized and slices collected for electrophysiology experiments. (B-C) Rnf20 knockdown did not impair the ability of the animals to acquire the fear conditioning task (B, two-tailed t-test, t9 = 1.100, P = 0.3000, n = 4–7 per group), but significantly impaired memory during the test day (C, two-tailed t-test, t9 = 2.750, P = 0.0225, n = 4–7 per group). (D) Knockdown of Rnf20 impaired LTP (left), which was localized to the late (right, 90, two-tailed t-test, t75 = 0.2.276, P = 0.0257, n = 38–39 slices per group), but not early (right, 30, two-tailed t-test, t78 = 0.2945, P = 0.7692, n = 39–41 slices per group), phase of LTP. (E) Basal synaptic transmission was unaffected by Rnf20 knockdown. (F) Paired Pulse Facilitation remained largely intact. * P < 0.05 from Scr-siRNA.

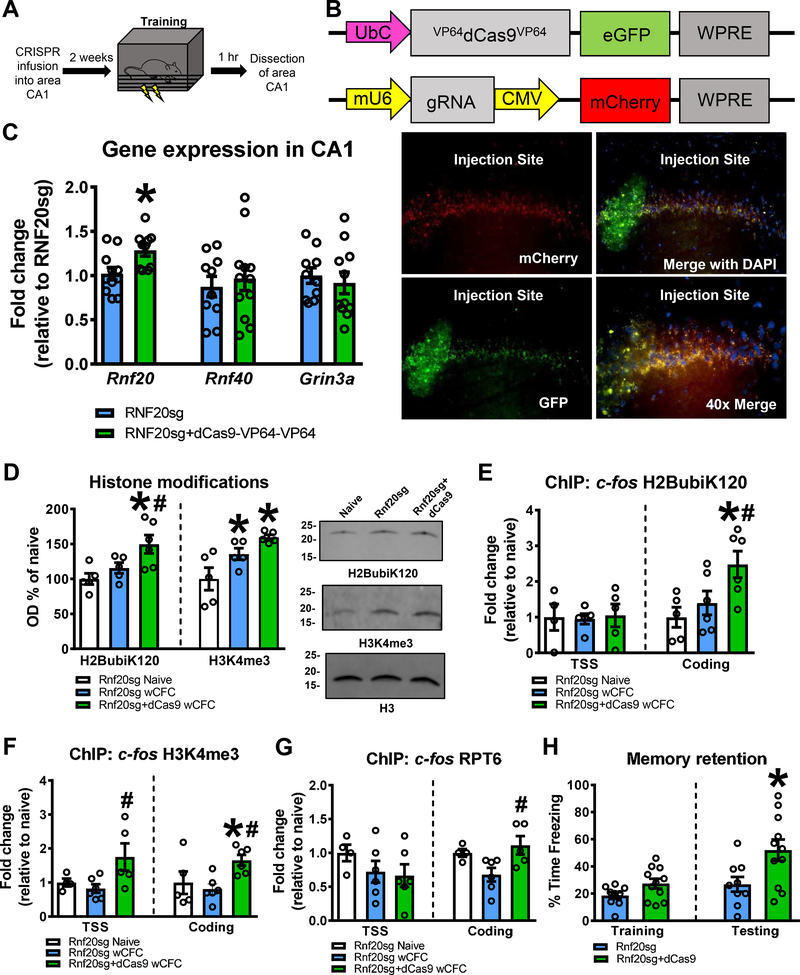

Increasing H2B ubiquitination recruits H3 methylation and promotes memory formation

We next asked whether enhancing H2BubiK120 would promote recruitment of H3K4me3 and enhance memory formation. For these experiments, we reduced the number of shocks presented as well as the duration of animal context training during the fear conditioning acquisition phase, as this results in a marked reduction in overall memory retention during the test phase. Prior to this weak contextual fear conditioning (wCFC), we increased endogenous expression of Rnf20 using the CRISPR-dCas9 system (Fig. 6A), which has been shown to effectively and specifically control gene transcription in neurons (26). Specifically, we used a synthetic guide RNA targeting a region 200 bp upstream of the Rnf20 TSS (Rnf20sg) alongside a catalytically-inactive Cas9 fused to a double VP64 transcriptional activator domain (dCas9-VP64-VP64). This Rnf20sg was under the control of the UbC promoter, limiting this manipulation specifically to neurons (Fig. 6B). DNA plasmids were transfected into the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus 2 weeks prior to wCFC (Fig. S10) and we confirmed that expression of Rnf20, but not binding partner Rnf40 or chromosomal adjacent gene Grin3a, was increased in area CA1 2 weeks after infusion of the CRISPR-dCas9 plasmids (Fig. 6C and S11). These results demonstrate that the CRSIPR-dCas9 system can be used to effectively upregulate Rnf20 expression in area CA1 in vivo.

Figure 6. Increasing H2BubiK120 enhances histone methylation and promotes memory formation under weak training conditions.

(A) CRISPR plasmids were injected into the CA1 region of the dorsal hippocampus 2 weeks prior to weak contextual fear conditioning and CA1 tissue collected 1 hr after completion of the training session. (B) Diagram of CRISPR constructs. The dCas9 carried a double VP64 transcriptional activator domain. Images depict sgRNA and dCas9 expression in dorsal CA1 2 weeks after infusion. (C) Infusion of sgRNA targeting Rnf20 in combination with dCas9 (Rnf20sg+dCas9VP64-Vp64) increased Rnf20 (left, two-tailed t-test, t19 = 2.754, P = 0.0126, n = 10–11 per group), but not related ubiquitin ligase Rnf40 (middle, two-tailed t-test, t20 = 0.5060, P = 0.6184, n = 11 per group) or downstream gene Grin3a (middle, two-tailed t-test, t19 = 0.5413, P = 0.5946, n = 10–11 per group), expression in dorsal CA1 2 weeks after transfection relative to sgRNA injected controls (Rnf20sg). (D) Rnf20sg+dcas9 increased global H2BubiK120 (left, one way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(2,13) = 6.133, P = 0.0133, n = 5–6 per group) and H3K4me3 (right, one way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(2,12) = 7.981, P = 0.0062, n = 5 per group) levels in bulk histone extracts following weak training. (E) Rnf20sg+dcas9 increased H2BubiK120 in the c-fos coding (right, one way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(2,14) = 5.064, P = 0.0221, n = 5–6 per group), but not TSS (left, one way ANOVA, F(2,11) = 0.03164, P = 0.9689, n = 4–5 per group), region following weak training. (F) Rnf20sg+dcas9 increased H3K4me3 in the c-fos TSS (left, one way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(2,12) = 3.898, P = 0.0496, n = 4–6 per group), and coding (right, one way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(2,14) = 4.494, P = 0.0311, n = 5–6 per group) regions following weak training. (G) Rnf20sg+dcas9 increased RPT6 in the c-fos coding (right, one way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(2,12) = 4.690, P = 0.0313, n = 4–6 per group), but not TSS (left, one way ANOVA, F(2,13) = 1.055, P = 0.3763, n = 4–6 per group), region following weak training. (H) Rnf20sg+dcas9 did not alter the ability of the animals to acquire the weak contextual fear conditioning task (left, two-tailed t-test, t18 = 1.921, P = 0.0707, n = 9–11 per group) but enhanced memory when tested the following day (right, two-tailed t-test, t18 = 2.519, P = 0.0214, n = 9–11 per group). * P < 0.05 from Rnf20sg. # P < 0.05 from Rnf20sg wCFC

Next, we examined H2BubiK120 and H3K4me3 levels in bulk histone extracts collected from area CA1 1 hr after wCFC (Fig. 6D and S11). We found that while wCFC was not sufficient to upregulate H2BubiK120 on its own, the Rnf20sg+dCas9 resulted in a significant increase in H2BubiK120 following learning, further demonstrating that we could artificially drive increases in H2BubiK120 in area CA1. Additionally, we found that while wCFC did increase H3K4me3 levels, this was further increased by Rnf20sg+dCas9, showing recruitment of H3K4me3 during Rnf20 overexpression. We next asked whether increasing Rnf20 would drive gene-specific H2BubiK120 and H3K4me3 following wCFC. Remarkably, although we saw no changes in H2BubiK120 (Fig. 6E) or H3K4me3 (Fig. 6F) at the c-fos TSS or coding region following wCFC, enhancing Rnf20 expression significantly increased both marks while leaving other marks unaffected (Fig. S12). Additionally, Rnf20sg+dCas9 also enhanced the recruitment of RPT6 to the c-fos coding region following wCFC (Fig. 6G). Importantly, neither histone mark nor RPT6 was increased within the c-fos TSS or coding region in response to wCFC unless the Rnf20sg was co-infused with dCas9. These findings show that we were able to recruit H2BubiK120, H3K4me3 and RPT6 to specific gene regions by promoting the endogenous transcription of Rnf20. Consistent with this, we saw a nearly 3-fold increase in memory retention after animals were infused with both Rnf20sg and dCas9 (Fig 6H). Collectively, these results indicate that enhancing H2BubiK120 increases H3K4me3 and promotes memory formation under weak training conditions.

H2B ubiquitination regulates memory formation via histone methylation

Our previous experiments found that H2BubiK120 regulates histone methylation and memory formation. However, these experiments did not directly test whether H2BubiK120 regulates memory formation specifically by way of recruitment of histone methylation. To test this directly, we simultaneously knocked down Rnf20 expression in area CA1 while promoting global histone methylation through knockdown of the histone lysine demethylase 1 (Kdm1a; Fig. 7A–B). We found that animals that received the Rnf20-siRNA had impaired memory on the test day relative to controls and these memory impairments were completely rescued by simultaneous knockdown of Kdm1a (Fig. 7C). Considering that KDM1A is not specific to H3K4me3 and can instead regulate demethylation of H3K9me2, which is also involved in memory formation (7, 8), we further tested the H2BubiK120-H3K4me3 relationship by using the CRISPR-dCas9 system to simultaneously upregulate the expression of Mll1 and Usp49, a H2B-specific deubiquitinating enzyme (Fig. 7D–E). Remarkably, we found that upregulation of Usp49 alone or in combination with Mll1 resulted in memory deficits relative to controls (Fig. 7F). In combination with our biochemical data, these findings strongly suggest that H2B ubiquitination regulates fear memory formation in the hippocampus through recruitment of histone lysine-4 methylation mechanisms (Fig. S14).

Figure 7. Increasing H3K4me3 does not rescue memory deficits that result from loss of H2BubiK120.

(A) Animals were injected with control (Scr-siRNA), Rnf20- (Rnf20-siRNA), histone demethylase 1a- (Kdm1a-siRNA) or a combination of Rnf20- and histone demethylase 1a-siRNAs (Rnf20+Kdm1a-siRNA) into the CA1 region of the dorsal hippocampus. Five days later, animals were trained to contextual fear conditioning and tested 24 hrs later. (B) qRT-PCR analysis showing successful knockdown of Rnf20 (One way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(3,23) = 8.392, P = 0.0006, n = 6–7 per group) and Kdm1a (One way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(3,22) = 7.059, P = 0.0017, n = 6–7 per group) alone or in combination. (C) None of the siRNAs altered the ability of the animals to acquire the task (One way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(3,21) = 1.025, P = 0.4015, n = 6–7 per group) but simultaneous knockdown of Rnf20 and Kdm1a rescued memory deficits that resulted from loss of Rnf20 alone (One way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(3,21) = 3.392, P = 0.0370, n = 6–7 per group). (D) Animals were injected with control (USP49sg+MLL1sg), USP49sg+dCas9-VP64-VP64 or USP49sg+MLL1sg+dCas9-VP64-VP64 into the CA1 region of the dorsal hippocampus. Two weeks later, animals were trained to contextual fear conditioning and tested 24 hrs later. (E) qRT-PCR analysis showing successful upregulation of Usp49 (One way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(2,15) = 3.951, P = 0.0418, n = 6 per group) and Mll1 (One way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(2,15) = 46.51, P < 0.0001, n = 6 per group) alone or in combination. (F) A main effect was found for CRISPR plasmid administration for the test (right, One way ANOVA, F(2,15) = 3.932, P = 0.0424, n = 6 per group), but not training session (left, One way ANOVA, Fisher LSD posthoc tests, F(2,15) = 0.6059, P = 0.5584, n = 6 per group). During the test session, upregulation of Usp49 alone (two-tailed t-test, t10 = 2.301, P = 0.0442) or in combination with upregulation of Mll1 (two-tailed t-test, t10 = 2.641, P = 0.0247) resulted in memory deficits relative to controls. * P < 0.05 from Scr-siRNA or USPsg+MLL1sg. # P < 0.05 from Rnf20+Kdm1a-siRNA or USP49sg+dCas9-VP64-VP64.

Discussion

Many studies have identified a role for various histone modifications in memory consolidation (9, 27–30). While less abundant than other modifications (31), histone ubiquitination has been shown to regulate chromatin boundary integrity and broad transcriptional processes (32, 33), though remains poorly understood in the context of memory formation. Here, we identified H2B ubiquitination as a critical regulator of histone methylation during fear memory formation in the hippocampus. We found that H2BubiK120 directs global and gene-specific increases in transcriptionally-active histone methylation, gene expression, synaptic plasticity, and memory consolidation in hippocampal neurons. Remarkably, we found that H2BubiK120 regulates histone methylation by recruiting the 19S proteasomal subunit RPT6, suggesting a non-proteolytic role for the proteasome in histone cross-talk during memory formation. This study is the first to identify a clear role for histone ubiquitination in synaptic plasticity and long-term memory, and, collectively, our results suggest that H2B ubiquitination is a regulator of histone methylation mechanisms that are critical for fear memory formation.

More broadly, our results provide some of the earliest examples of how histone cross-talk is regulated during memory formation. Importantly, we found that while a loss of H2BubiK120 reduced H3K4me3 levels, H2BubiK120 remained at normal levels when H3K4me3 was lost. This strongly suggests that H2B ubiquitination occurs upstream of H3 methylation and that simply manipulating one histone modification will not indirectly alter the expression of another. Additionally, we found that loss of H2BubiK120 reduces learning-dependent H3K4me3 globally and in a gene-specific manner, suggesting that H2BubiK120 plays a significant role in the activity-dependent recruitment of H3K4me3. However, our data demonstrated that not all H3K4me3-target genes are regulated by H2BubiK120. Future studies should identify which genes require H2BubiK120 for the recruitment of H3K4me3 and how those genes that do not require H2BubiK120 ultimately become enriched in H3K4me3.

Despite our evidence that H2BubiK120 regulates H3K4me3 during memory formation, some of our data revealed that H3K4me3 could still be engaged following weak contextual fear conditioning in the absence of H2BubiK120. These data suggest that under certain conditions it is possible H3K4me3 can still regulate memory formation in the absence of H2BubiK120, likely by the MLL1-H3K4me3 complex being targeted to specific gene loci via another mechanism. While it is unclear what this mechanism is, it is important to note that behavioral performance in this case remained low, suggesting that even if H3K4me3 could be engaged in the absence of H2BubiK120 it may not be optimal for normal memory formation. Consistent with this, our CRISPR experiments revealed that simply upregulating Mll1 is not sufficient to overcome the memory deficits that result from losing H2BubiK120. Future studies will need to more precisely examine the unique conditions in which H3K4me3 is capable of regulating memory formation in the absence of H2BubiK120.

A number of recent studies have identified a role for ubiquitin-proteasome signaling in memory formation (34–37). However, these studies have focused mainly on the proteasome’s proteolytic activity during memory consolidation (38). Here, we found that monoubiquitination of H2B regulates the transcription of genes necessary for memory consolidation in the hippocampus—one of the first non-proteolytic roles of the UPS to be discovered in this context, and the first of such functions to be identified in the context of histone modification. This suggests that memory formation requires both proteasome-dependent and proteasome-independent ubiquitination in neurons. Consistent with this was the surprising finding that the RPT6 subunit is necessary for H2BubiK120-dependent recruitment of H3K4me3, as well as H2BubiK120 stability. This supports a non-proteolytic function of the proteasome complex in synaptic plasticity (39), although it was unexpected that Psmc5 knockdown resulted in loss of global and gene-specific H2BubiK120 levels following learning. However, some recent evidence suggests that H2BubiK120 levels could be regulated by RPT6, as yeast SUG1 regulates the deubiquitinating activity of the H2B-specific deubiquitinase USP49 (40). While it is unclear how RPT6 regulated H2BubiK120 levels in the present study, our results strongly suggest that RPT6 may be a critical component in the complex that H2BubiK120 recruits to regulate downstream transcriptional processes. Future studies are needed to determine how RPT6 regulates H2BubiK120 and H3K4me3 levels following learning, and whether RPT6 is necessary for the recruitment or stability of H2BubiK120 at gene promoters during the memory consolidation process.

An important limitation of our study was that the majority of experiments were completed using only male animals. Importantly, while sex as a biological variable has seldom been considered in studies examining the role of epigenetic modifications in memory formation (41), one recent study found that males and females differ significantly in their engagement and need for histone variant H2A.Z in the formation of aversive, but not non-aversive, spatial memories (42). Additionally, while some studies have found that both males and females require histone acetylation for memory formation (43–45), whether there are sex differences in the need for histone methylation are unknown. As no previous studies have examined the role of H2B ubiquitination in memory formation, it is unknown if a sex difference exists for this histone modification. While our data indicates that both males and females engage H2BubiK120 following learning, it is unclear if females, like males, need this histone modification to regulate H3 methylation dynamics and memory formation. Considering our recent work indicating that males and females differ significantly in ubiquitin-proteasome system regulation in the hippocampus (46), it is possible that H2BubiK120 may regulate memory formation in a sex-dependent manner. Future studies will need to more directly assess the role of H2BubiK120 in the regulation of H3 methylation and memory formation in females.

In conclusion, we offer the first evidence that H2B ubiquitination is a critical regulator of active histone methylation marks during the memory consolidation process. Considering that aberrant histone lysine methylation is often associated with intellectual disorders (47, 48) and is the most common histone modification associated with psychiatric disorders (11), targeting of H2B ubiquitination mechanisms may prove useful as a strategy for improving cognitive function and eliminating the memories of traumatic experiences that characterize disorders such as PTSD.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| Resource Type | Specific Reagent or Resource | Source or Reference | Identifiers | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Add additional rows as needed for each resource type | Include species and sex when applicable. | Include name of manufacturer, company, repository, individual, or research lab. Include PMID or DOI for references; use “this paper” if new. | Include catalog numbers, stock numbers, database IDs or accession numbers, and/or RRIDs. RRIDs are highly encouraged; search for RRIDs at https://scicrunch.org/resources. | Include any additional information or notes if necessary. |

| Antibody: H2B ubiquitin lysine 120 | Rat | Cell Signaling | 5546 | Western blot, Chromatin Immunoprecipitation, Immunofluorescence, Immunoprecipitation |

| Antibody: H2B (total) | Rat | Cell Signaling | 12364 | Western blot |

| Antibody: H3 lysine 4 trimethylation | Rat | MilliporeSigma | 04-745 | Western blot, Chromatin Immunoprecipitation |

| Antibody: H3 (total) | Rat | Abcam | ab1791 | Western blot |

| Antibody: H3 lysine 9 dimethylation | Rat | MilliporeSigma | 07-441 | Western blot |

| Antibody: H3 lysine 27 trimethylation | Rat | MilliporeSigma | 07-449 | Western blot |

| Antibody: H2A ubiquitin lysine 119 | Rat | Cell Signaling | 8240 | Western blot |

| Antibody: H2A (total) | Rat | Cell Signaling | 12349 | Western blot |

| Antibody: H3 acetylation | Rat | MilliporeSigma | 06-599 | Western blot, Chromatin Immunoprecipitation |

| Antibody: RNF20 | Rat | Cell Signaling | 11974 | Western blot |

| Antibody: RPT6 (PSCM5) | Rat | Abcam | ab178681 | Western blot, Chromatin Immunoprecipitation, Immunofluorescence, Immunopreciptation |

| Antibody: Actin | Rat | Cell Signaling | ab1801 | Western blot |

| Antibody: Alexa488 Secondary | Goat anti-rabbit | Jackson Immuno Research | 111-545-003 | Immunofluorescence |

| Cell Line: B35 cells | Rat | ATCC | CRL-2754 | |

| Transfection: Lipofectamine 3000 | N/A | Invitrogen | L3000001 | |

| Transfection: In Vivo Jet-PEI | N/A | Polyplus | 201-10G | 0.5ug/ul total DNA |

| Accell siRNA: Rnf20 | Rat | Dharmacon | E-096875-00-0005 | 4.5uM |

| Accell siRNA: Mll1 (Kmt2a) | Rat | Dharmacon | E-100995-00-0005 | 4.5uM |

| Accell siRNA: Psmc5 | Rat | Dharmacon | E-096860-00-0005 | 4.5uM |

| Accell siRNA: Kmd1a | Rat | Dharmacon | E-105863-00-0005 | 4.5uM |

| Accell siRNA: Control | Rat | Dharmacon | D-001910-10-05 | 4.5uM |

| Organism/Strain | Rat, Sprague Dawley, Male and Female | Envigo | 8–9 week old at arrival | |

| Recombinant DNA | CRISPR gRNA Vector | Addgene | 44248 | |

| Recombinant DNA | VP64-dCas9-VP64 | Addgene | 59791 | |

| Reagent: Proteasome activity kit | N/A | MilliporeSigma | APT280 | |

| Reagent: Protein A/G Beads | N/A | Thermo Fisher | 88802 | Immunoprecipitation |

| Reagent: Magna ChIP Protein A/G Beads | N/A | MilliporeSigma | 16-663 | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation |

Acknowledgements and Funding

We thank the UAB electrophysiology core facility for help with collection of the electrophysiology data. This work was supported by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants MH097909 (F.D.L.), and the Evelyn F. McKnight Brain Institute at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. T.J.J. was supported in part by a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Federation for Aging Research (PD16051). W.M.W. is supported by the NIH NIGMS (T32 GM008361) and NINDS (F30 NS100340).

Footnotes

Competing Interests

All authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jarome TJ, Lubin FD (2014): Epigenetic mechanisms of memory formation and reconsolidation. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 115:116–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwapis JL, Wood MA (2014): Epigenetic mechanisms in fear conditioning: implications for treating post-traumatic stress disorder. Trends in neurosciences. 37:706–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dias BG, Maddox SA, Klengel T, Ressler KJ (2015): Epigenetic mechanisms underlying learning and the inheritance of learned behaviors. Trends in neurosciences. 38:96–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haettig J, Stefanko DP, Multani ML, Figueroa DX, McQuown SC, Wood MA (2011): HDAC inhibition modulates hippocampus-dependent long-term memory for object location in a CBP-dependent manner. Learn Mem. 18:71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McQuown SC, Barrett RM, Matheos DP, Post RJ, Rogge GA, Alenghat T, et al. (2011): HDAC3 is a critical negative regulator of long-term memory formation. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 31:764–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day JJ, Sweatt JD (2010): DNA methylation and memory formation. Nature neuroscience. 13:1319–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta-Agarwal S, Franklin AV, Deramus T, Wheelock M, Davis RL, McMahon LL, et al. (2012): G9a/GLP histone lysine dimethyltransferase complex activity in the hippocampus and the entorhinal cortex is required for gene activation and silencing during memory consolidation. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 32:5440–5453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta-Agarwal S, Jarome TJ, Fernandez J, Lubin FD (2014): NMDA receptor- and ERK-dependent histone methylation changes in the lateral amygdala bidirectionally regulate fear memory formation. Learn Mem. 21:351–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta S, Kim SY, Artis S, Molfese DL, Schumacher A, Sweatt JD, et al. (2010): Histone methylation regulates memory formation. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 30:3589–3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerimoglu C, Agis-Balboa RC, Kranz A, Stilling R, Bahari-Javan S, Benito-Garagorri E, et al. (2013): Histone-methyltransferase MLL2 (KMT2B) is required for memory formation in mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 33:3452–3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Network, Pathway Analysis Subgroup of Psychiatric Genomics C (2015): Psychiatric genome-wide association study analyses implicate neuronal, immune and histone pathways. Nature neuroscience. 18:199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller CA, Campbell SL, Sweatt JD (2008): DNA methylation and histone acetylation work in concert to regulate memory formation and synaptic plasticity. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 89:599–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun ZW, Allis CD (2002): Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates H3 methylation and gene silencing in yeast. Nature. 418:104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarome TJ, Helmstetter FJ (2013): The ubiquitin-proteasome system as a critical regulator of synaptic plasticity and long-term memory formation. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 105:107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hegde AN (2010): The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and synaptic plasticity. Learn Mem. 17:314–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wojcik F, Dann GP, Beh LY, Debelouchina GT, Hofmann R, Muir TW (2018): Functional crosstalk between histone H2B ubiquitylation and H2A modifications and variants. Nat Commun. 9:1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shema E, Tirosh I, Aylon Y, Huang J, Ye C, Moskovits N, et al. (2008): The histone H2B-specific ubiquitin ligase RNF20/hBRE1 acts as a putative tumor suppressor through selective regulation of gene expression. Genes & development. 22:2664–2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang E, Kawaoka S, Yu M, Shi J, Ni T, Yang W, et al. (2013): Histone H2B ubiquitin ligase RNF20 is required for MLL-rearranged leukemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110:3901–3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarome TJ, Butler AA, Nichols JN, Pacheco NL, Lubin FD (2015): NF-kappaB mediates Gadd45beta expression and DNA demethylation in the hippocampus during fear memory formation. Front Mol Neurosci. 8:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarome TJ, Perez GA, Hauser RM, Hatch KM, Lubin FD (2018): EZH2 Methyltransferase Activity Controls Pten Expression and mTOR Signaling during Fear Memory Reconsolidation. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 38:7635–7648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webb WM, Sanchez RG, Perez G, Butler AA, Hauser RM, Rich MC, et al. (2017): Dynamic association of epigenetic H3K4me3 and DNA 5hmC marks in the dorsal hippocampus and anterior cingulate cortex following reactivation of a fear memory. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 142:66–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gertz J, Savic D, Varley KE, Partridge EC, Safi A, Jain P, et al. (2013): Distinct properties of cell-type-specific and shared transcription factor binding sites. Molecular cell. 52:25–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernstein BE, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Costello JF, Ren B, Milosavljevic A, Meissner A, et al. (2010): The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium. Nat Biotechnol. 28:1045–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma MK, Heath C, Hair A, West AG (2011): Histone crosstalk directed by H2B ubiquitination is required for chromatin boundary integrity. PLoS genetics. 7:e1002175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ezhkova E, Tansey WP (2004): Proteasomal ATPases link ubiquitylation of histone H2B to methylation of histone H3. Molecular cell. 13:435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng Y, Shen W, Zhang J, Yang B, Liu YN, Qi H, et al. (2018): CRISPR interference-based specific and efficient gene inactivation in the brain. Nature neuroscience. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stefanko DP, Barrett RM, Ly AR, Reolon GK, Wood MA (2009): Modulation of long-term memory for object recognition via HDAC inhibition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106:9447–9452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bredy TW, Wu H, Crego C, Zellhoefer J, Sun YE, Barad M (2007): Histone modifications around individual BDNF gene promoters in prefrontal cortex are associated with extinction of conditioned fear. Learn Mem. 14:268–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng J, Zhou Y, Campbell SL, Le T, Li E, Sweatt JD, et al. (2010): Dnmt1 and Dnmt3a maintain DNA methylation and regulate synaptic function in adult forebrain neurons. Nature neuroscience. 13:423–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guan JS, Haggarty SJ, Giacometti E, Dannenberg JH, Joseph N, Gao J, et al. (2009): HDAC2 negatively regulates memory formation and synaptic plasticity. Nature. 459:55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tweedie-Cullen RY, Reck JM, Mansuy IM (2009): Comprehensive mapping of post-translational modifications on synaptic, nuclear, and histone proteins in the adult mouse brain. Journal of proteome research. 8:4966–4982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Batta K, Zhang Z, Yen K, Goffman DB, Pugh BF (2011): Genome-wide function of H2B ubiquitylation in promoter and genic regions. Genes & development. 25:2254–2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bourbousse C, Ahmed I, Roudier F, Zabulon G, Blondet E, Balzergue S, et al. (2012): Histone H2B monoubiquitination facilitates the rapid modulation of gene expression during Arabidopsis photomorphogenesis. PLoS genetics. 8:e1002825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jarome TJ, Werner CT, Kwapis JL, Helmstetter FJ (2011): Activity dependent protein degradation is critical for the formation and stability of fear memory in the amygdala. PloS one. 6:e24349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reis DS, Jarome TJ, Helmstetter FJ (2013): Memory formation for trace fear conditioning requires ubiquitin-proteasome mediated protein degradation in the prefrontal cortex. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience. 7:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Artinian J, McGauran AM, De Jaeger X, Mouledous L, Frances B, Roullet P (2008): Protein degradation, as with protein synthesis, is required during not only long-term spatial memory consolidation but also reconsolidation. The European journal of neuroscience. 27:3009–3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez-Salon M, Alonso M, Vianna MR, Viola H, Mello e Souza T, Izquierdo I, et al. (2001): The ubiquitin-proteasome cascade is required for mammalian long-term memory formation. The European journal of neuroscience. 14:1820–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pavlopoulos E, Trifilieff P, Chevaleyre V, Fioriti L, Zairis S, Pagano A, et al. (2011): Neuralized1 activates CPEB3: a function for nonproteolytic ubiquitin in synaptic plasticity and memory storage. Cell. 147:1369–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohnishi YH, Ohnishi YN, Nakamura T, Ohno M, Kennedy PJ, Yasuyuki O, et al. (2015): PSMC5, a 19S Proteasomal ATPase, Regulates Cocaine Action in the Nucleus Accumbens. PloS one. 10:e0126710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Z, Jones A, Joo HY, Zhou D, Cao Y, Chen S, et al. (2013): USP49 deubiquitinates histone H2B and regulates cotranscriptional pre-mRNA splicing. Genes & development. 27:1581–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keiser AA, Wood MA (2019): Examining the contribution of histone modification to sex differences in learning and memory. Learn Mem. 26:318–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramzan F, Creighton SD, Hall M, Baumbach J, Wahdan M, Poulson SJ, et al. (2020): Sex-specific effects of the histone variant H2A.Z on fear memory, stress-enhanced fear learning and hypersensitivity to pain. Sci Rep. 10:14331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lopez-Atalaya JP, Ciccarelli A, Viosca J, Valor LM, Jimenez-Minchan M, Canals S, et al. (2011): CBP is required for environmental enrichment-induced neurogenesis and cognitive enhancement. EMBO J. 30:4287–4298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frick KM (2013): Epigenetics, oestradiol and hippocampal memory consolidation. J Neuroendocrinol. 25:1151–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maurice T, Duclot F, Meunier J, Naert G, Givalois L, Meffre J, et al. (2008): Altered memory capacities and response to stress in p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF) histone acetylase knockout mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 33:1584–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Devulapalli RK, Nelsen JL, Orsi SA, McFadden T, Navabpour S, Jones N, et al. (2019): Males and Females Differ in the Subcellular and Brain Region Dependent Regulation of Proteasome Activity by CaMKII and Protein Kinase A. Neuroscience. 418:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jarome TJ, Lubin FD (2013): Histone lysine methylation: critical regulator of memory and behavior. Reviews in the neurosciences. 24:375–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parkel S, Lopez-Atalaya JP, Barco A (2013): Histone H3 lysine methylation in cognition and intellectual disability disorders. Learning & memory. 20:570–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.