Abstract

Interactions between the bone marrow microenvironment and MDS tumor clones play a role in pathogenesis and response to treatment. We hypothesized G-CSF and plerixafor may enhance sensitivity to azacitidine in MDS. 28 patients with MDS were treated with plerixafor, G-CSF and azacitidine with a standard 3+3 design. Subjects received G-CSF 10 mcg/kg D1–D8, plerixafor D4–D8, and azacitidine 75 mg/m2 D4–D8, but the trial was amended to reduce G-CSF dose to 5 mcg/kg for 5 days after 2 patients had significant leukocytosis. Plerixafor was dose escalated to 560mcg/kg/day without dose limiting toxicity. Two complete responses and 6 marrow responses were seen for an overall response rate (ORR) of 36% in evaluable patients, and ORR of 53% in patients receiving the triplet. Evidence of mobilization correlated with a higher ORR, 60% vs 17%. Plerixafor, G-CSF and azacitidine appears tolerable when given over 5 days and has encouraging response rates.

Keywords: Plerixafor, G-CSF, MDS, azacitidine

INTRODUCTION

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) represent a spectrum of clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorders characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis, malignant expansion of clonal myeloid cells, and progressive bone marrow failure.[1] Azacitidine can prolong survival and delay progression of leukemia in intermediate-2 and high risk MDS. However, it is not curative and only achieves remission in approximately 20–30% of patients, with a median duration of response of 8–10 months.[2, 3]

Normal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) migrate to and are anchored in the perivascular niche of the bone marrow by chemotactic signals, including CXCL12 (stem cell derived factor-1, or SDF-1), which is produced by cells in the marrow stroma and binds to its receptor, chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) on the HSC surface.[4] Leukemic stem cells also use CXCL12- and CXCR4- adhesion molecule-dependent mechanisms to home to this perivascular niche where they are maintained in a quiescent, protected state.[5, 6, 7, 8] The bone marrow niche has been implicated in leukemogenesis by upregulating production of CXCR4 and CXCL12, enhancing the survival of malignant stem cells and protecting them from cytotoxic chemotherapy in MDS and AML.[9, 10] While CXCR4 is an unfavorable prognostic marker in AML[11, 12, 13], disrupting CXCR4 signaling inhibits transmigration, survival and chemotherapy resistance in AML xenografts.[14, 15, 16] The use of G-CSF priming with cytotoxic therapy in AML and MDS decreases the duration of neutropenia, reduces infections and possibly improves responses.[17, 18, 19]

G-CSF can mobilize hematopoietic stem cells by reducing CXCL12 expression in osteoblasts in the bone marrow niche.[20, 21] Plerixafor is a bicyclam small molecule inhibitor of CXCR4 and a potent stem cell mobilizing agent that is approved for use with G-CSF for mobilization of patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplant for multiple myeloma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma[22, 23, 24] and has been studied as a single agent for mobilization of normal donors.[25, 26]

Increased expression of CXCR4 on MDS blasts is associated with worse outcomes and lower rates of apoptosis with chemotherapy; additionally, disrupting CXCR4 in vitro disrupts cell adhesion and migration.[27, 28, 29] In pre-clinical models, disruption of the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis leads to mobilization of leukemic cells and sensitization to chemotherapy.[30, 31] Several clinical studies demonstrated the feasibility using plerixafor with chemotherapy that resulted in mobilization of malignant cells and encouraging responses.[32, 33] We hypothesized that plerixafor in combination with G-CSF would mobilize MDS blasts and improve their sensitivity to azacitidine, improving the overall response rate. The goal of this trial was to determine the optimal dose of plerixafor in combination with G-CSF and azacitidine in patients with high risk MDS.

METHODS

Patients

This was a single institution open-label phase 1 clinical trial of plerixafor, G-CSF and azacitidine. Eligible patients were >18 years old with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of MDS according to WHO criteria with 5–20% blasts in the bone marrow aspirate and at least one cytopenia.[34] Previous hypomethylating agent (HMA) therapy was allowed and all patients were required to have a 4 week washout period from prior therapy. Patients were excluded if they had untreated 5q minus syndrome, if their life expectancy was < 2 months in the opinion of the treating physician, or if they had poor liver or kidney function.

Treatment

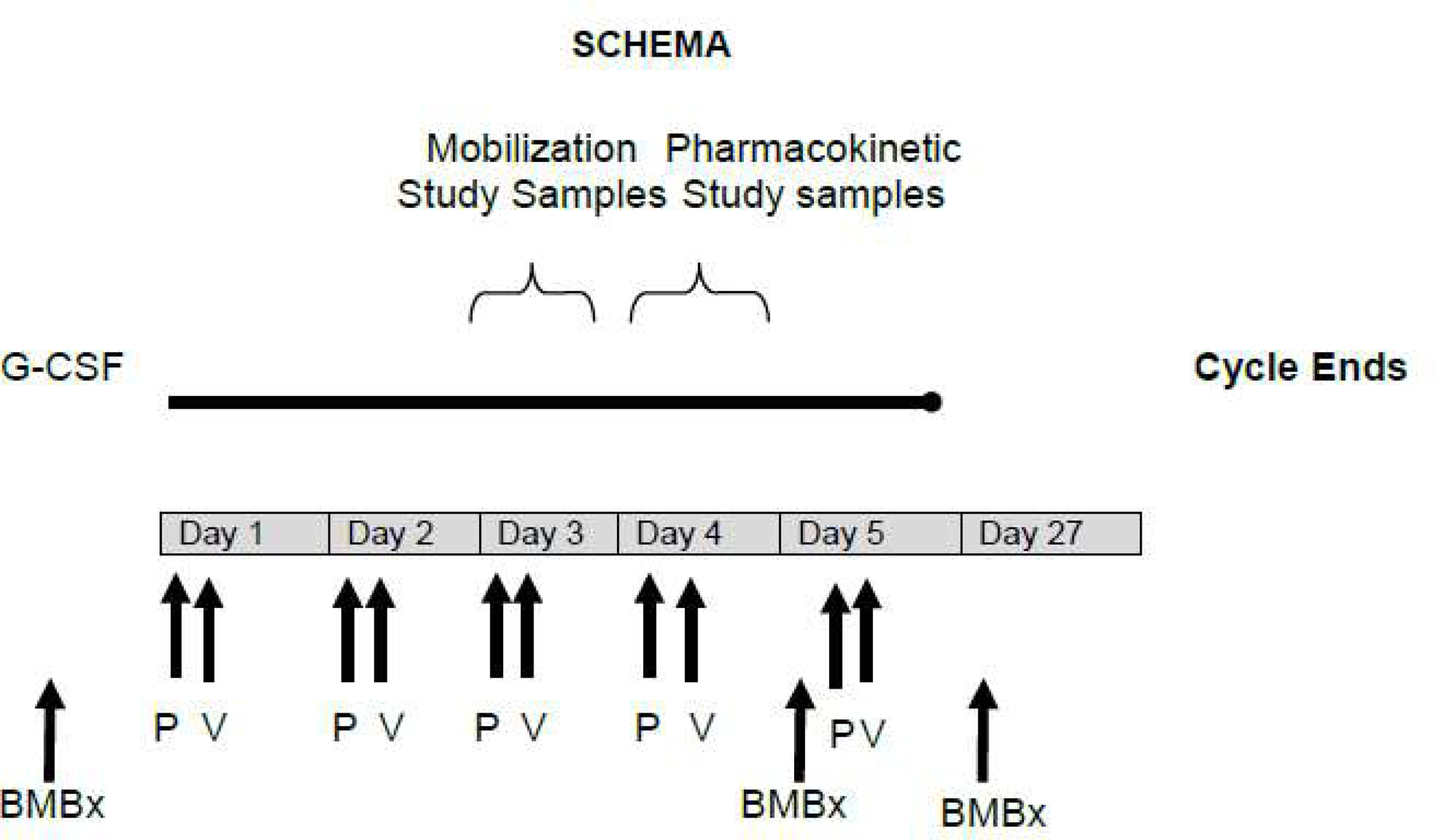

This phase 1 trial of adding plerixafor to G-CSF and azacitidine was performed using a standard 3 + 3 design with 3 dose escalation cohorts of plerixafor 320 µg/kg/day, 440 µg/kg/day, and 560 µg/kg/day. Seven additional patients were enrolled at the highest dose level of plerixafor and treated without G-CSF to evaluate the phenotype and preferential mobilization of blasts with plerixafor alone. Patients received G-CSF 5 µg/kg subcutaneously daily on days 1–5. Plerixafor was given subcutaneously at the prescribed dose level on days 1–5, 4 hours prior to azacitidine 75 mg/m2 given as a subcutaneous injection (Figure 1). The trial initially called for patients to receive G-CSF 10 mcg/kg subcutaneously daily on days 1–8, plerixafor daily on days 4–8, and azacitidine on days 4–8, but was amended after the first 3 patients to reduce G-CSF dose to 5 mcg/kg/day and administration to 5 days.

Figure 1.

Trial schema showing cycle 1 of plerixafor, G-CSF and azacitidine. P plerixafor. V azacitidine (Vidaza).

The primary objective of this study was to determine the optimal dose and schedule of plerixafor and determine the safety and tolerability of plerixafor, G-CSF and azacitidine. Secondary objectives were to characterize the mobilization of MDS cells and determine the response rate and progression free survival of patients. Dose limiting toxicity was defined as grade 3 or higher non-hematologic toxicity and hematologic toxicity of leukostasis or tumor lysis. Myelosuppression, infection, grade 3 nausea, fatigue, weight loss, and electrolyte abnormalities were not considered dose limiting. Dose holding parameters for G-CSF and plerixafor were a white blood cell (WBC) count exceeding 40k/uL or absolute peripheral blood blast count exceeding 10k/uL.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample, as well as adverse events and complications, were summarized using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means, medians and standard deviations for ordinal and continuous variables. Responses to therapy were described using frequencies and percentages. Survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and univariate associations between clinical characteristics were evaluated with the log-rank test. All analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism, version 7.04 and R, version 3.5.1.

This study was conducted at the Siteman Cancer Center at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. It was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and all patients voluntarily provided informed consent to participate. This trial was registered on clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01065129. Data Collection and statistical analyses were conducted by the Siteman Cancer Center.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Twenty-eight patients were treated with plerixafor, G-CSF and azacitidine. Baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. The median age at time of registration was 67 years and 64% were male. Ten patients had refractory anemia with excess blasts (RAEB-1), while 18 patients had RAEB-2. The international prognosis scoring system (IPSS) was low risk in 1 patient, intermediate-1 in 6, intermediate-2 in 15 and high in 6. Thirteen patients had received prior chemotherapy, 8 of which were for a previous malignancy. Six patients had received prior HMA therapy (azacitidine = 3, decitabine = 3) with either no response or progressive disease. On baseline bone marrow biopsy, the median blast count was 11%. Seven patients had high risk cytogenetic abnormalities. Not all patients had baseline molecular data collected based on the year they were enrolled.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and disease characteristics.

| All Patients (n = 28) | Responders (n=8) | Non-responders (n=14) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Age (range) | 67 years (32–79) | 67 years (60–71) | 66 years (32–79) | p = 0.49 |

| Sex (% male) | 18 (64%) | 3 (38%) | 11 (79%) | p = 0.054 |

| Diagnosis | p = 0.67 | |||

| RAEB-1 | 10 (36%) | 3 (38%) | 4 (29%) | |

| RAEB-2 | 18 (64%) | 5 (63%) | 10 (71%) | |

| Therapy-related | 8 (29%) | 3 (38%) | 1 (7%) | |

| IPSS | p = 0.58 | |||

| Low | 1 (4%) | 1 (13%) | 0 (0%) | |

| INT-1 | 6 (21%) | 1 (13%) | 2 (14%) | |

| INT-2 | 15 (54%) | 4 (50%) | 9 (64%) | |

| High | 6 (21%) | 2 (25%) | 3 (21%) | |

| Prior HMA exposure | 6 (21%) | 2 (25%) | 4 (29%) | p = 0.86 |

| Azacitidine | 3 (11%) | 2 (25%) | 3 (21%) | |

| Decitabine | 3 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7%) | |

| Cytogenetics: | p = 0.71 | |||

| Poor Risk | 8 (29%) | 2 (25%) | 4 (29%) | |

| Intermediate | 6 (21%) | 3 (38%) | 3 (21%) | |

| Favorable | 13 (46%) | 3 (38%) | 7 (50%) | |

| Not evaluated | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

RAEB: refractory anemia with excess blasts; IPSS: international prognostic scoring system; INT: intermediate; HMA: hypomethylating agent.

Study Results

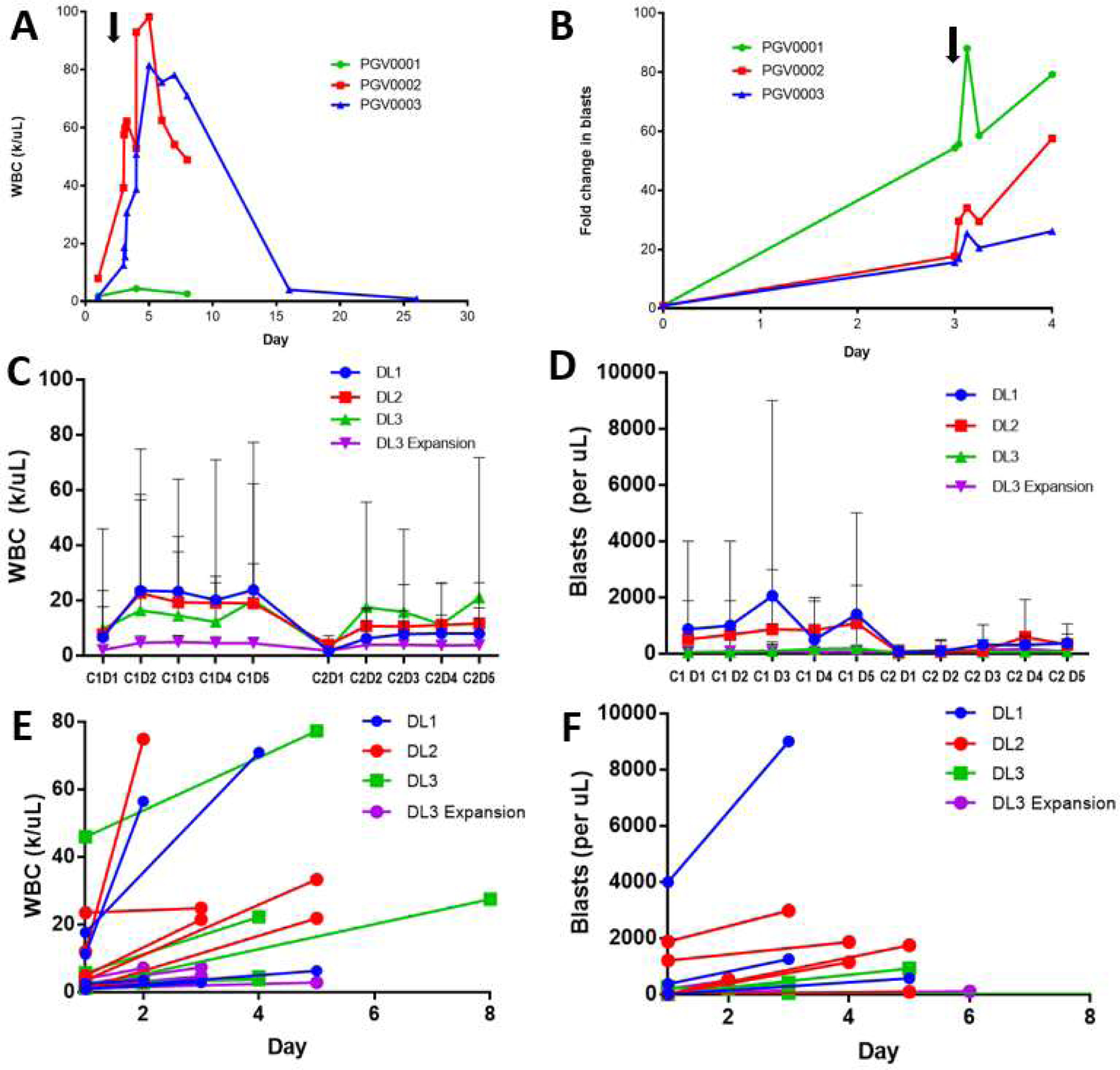

The addition of plerixafor at the lowest dose level (plerixafor 320 µg/kg/day) to G-CSF 10 mcg/kg/day and azacitidine resulted in brisk leukocytosis. Two of 3 patients enrolled in the first cohort experienced significant leukocytosis to 80k/uL and 100k/uL (Figure 2A). One patient developed symptoms concerning for leukostasis. These patients had treatment held, and their counts returned to normal. After this, the trial was amended to reduce the G-CSF dose from 10 mcg/kg/day to 5 mcg/kg/day and to reduce the duration from 8 to 5 days, concurrent with plerixafor and azacitidine. After this protocol amendment, 5 of 18 additional patients receiving plerixafor and G-CSF developed leukocytosis of WBC >40k/uL requiring treatment to be held (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. WBC and Blast Mobilization.

(A) WBC count of the original study cohort of 3 patients treated with G-CSF 10 mcg/kg daily on days 1–8, plerixafor 320 µg/kg/day days 4–8, and azacitidine (arrow indicates start of plerixafor). (B) Blast fold increase in peripheral blood (by morphology) for the original study cohort (arrow indicates plerixafor administration). (C) Mean daily WBC count by plerixafor dose during cycles 1 and 2 in the revised cohorts treated with G-CSF 5 mcg/kg given daily on days 1–5, azacitidine, and plerixafor 320 µg/kg/day, 440 µg/kg/day, and 560 µg/kg/day in dose level (DL) 1, DL2, and DL3 as well as the expansion cohort treated with plerixafor 560 µg/kg/day and azacitidine without G-CSF (error bars indicate range). (D) Mean absolute peripheral blood blast count by dose level with ranges. (E) Baseline and peak WBC count during cycle 1 of assigned therapy by dose level. (F) Baseline and peak peripheral absolute blast count during cycle 1 of assigned therapy by dose level.

MTD Determination and Toxicity

Dose-limiting toxicities seen in the revised cohort for dose level 1 were atrial fibrillation in 1 patient and thrombocytosis in 1 patient at dose level 2 (Table 2). No DLTs were seen at dose level 3 or in the expansion cohort at dose level 3 treated with plerixafor and azacitidine. Grade 3–4 adverse events are listed in Table 3. The most common grade 3–4 nonhematologic events included hyponatremia (25%), febrile neutropenia (25%), hypophosphatemia (14%), hyperglycemia (14%), pneumonia (14%), hypoxia (11%), fatigue (11%) and dyspnea (11%). Other common adverse events included fatigue (68%), nausea (64%), diarrhea (61%), dyspnea (54%), constipation (46%), generalized weakness (46%), dizziness (42%), edema (39%), hypotension (39%) and injection site reactions (39%). Two patients died on study, 1 from respiratory failure and a second from sepsis. These events occurred after cycle 3 and cycle 2 at dose level 3 and in the expansion cohort, respectively, and were thought to be unrelated to treatment with plerixafor and/or G-CSF.

Table 2.

Treatment Cohorts

| Cohorts | Dose Limiting Toxicity | Best Response | Reason for study withdrawal |

|---|---|---|---|

|

DL1 (n=3) Plerixafor 320 µg/kg D4–8 G-CSF 10 mcg/kg D1–8 Azacitidine 75mg/m2 D4–8 |

Leukocytosis, grade 4 (n=1) Leukocytosis, grade 2 (n=1) |

Not evaluable n=3 | DLT n=1 Transplant n=1 Hospice n=1 |

|

Revised DL1 (n=6) Plerixafor 320 µg/kg D1–5 G-CSF 5 mcg/kg D1–5 Azacitidine 75 mg/m2 D1–5 |

Atrial fibrillation, grade 3 (n=1) | CR/mCR n=2 Progressive disease n=3 Not evaluable n=1 |

Disease progression n=4 DLT n=1 Hospice n=1 |

|

DL2 (n=6) Plerixafor 440 µg/kg D1–5 G-CSF 5 mcg/kg D1–5 Azacitidine 75 mg/m2 D1–5 |

Thrombocytosis (n=1) | CR/mCR n=2 Stable disease n=2 Not evaluable n=1 Progressive disease n=1 |

Disease progression n=3 Transplant n=1 DLT n=1 Withdrew consent n=1 |

|

DL3 (n=6) Plerixafor 560 µg/kg D1–5 G-CSF 5 mcg/kg D1–5 Azacitidine 75 mg/m2 D1–5 |

None | CR/mCR n=4 Stable disease n=1 Not evaluable n=1 |

Withdrew consent n=3 Transplant n=1 Death n=1 Disease progression n=1 |

|

DL3 Expansion Cohort (n=7) Plerixafor 560 µg/kg D1–5 Azacitidine 75 mg/m2 D1–5 |

None | Stable disease n=5 Progressive disease n=2 |

Transplant n=4 Disease progression n=2 Death n=1 |

DL: dose level, CR: complete response, mCR: marrow complete response

Table 3.

Grade 3–4 Adverse Events Seen in >1 Patient (N = 28)

| AE | Patients with Gr III/IV AE | % |

|---|---|---|

| Leukopenia | 16 | 57% |

| Neutropenia | 11 | 39% |

| Anemia | 10 | 36% |

| Thrombocytopenia | 9 | 32% |

| Hyponatremia | 7 | 25% |

| Febrile Neutropenia | 7 | 25% |

| Pneumonia | 4 | 14% |

| Hypophosphatemia | 4 | 14% |

| Hypoxia | 3 | 11% |

| Fatigue | 3 | 11% |

| Dyspnea | 3 | 11% |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 2 | 7% |

| Syncope | 2 | 7% |

| Cellulitis | 2 | 7% |

| Sinusitis | 2 | 7% |

| Hypokalemia | 2 | 7% |

| Hypertension | 2 | 7% |

| Headache | 2 | 7% |

| Decreased ejection fraction | 2 | 7% |

| Diarrhea | 2 | 7% |

| Acute kidney injury | 2 | 7% |

| C. Diff Colitis | 2 | 7% |

As expected with HMA therapy in patients with MDS, hematologic toxicity was common. Grade 3–4 lymphopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia were seen in 64%, 36% and 32% of patients, respectively. As expected with G-CSF and plerixafor, leukocytosis was relatively common with 4 instances of grade 2 leukocytosis and one instance of grade 4 leukocytosis. This led to study discontinuation in two patients and treatment delays in three patients.

Efficacy Assessments

The 28 patients treated received a median of 3 cycles of treatment (range < 1 to 10) with 22 patients evaluable after cycle 2. The best response achieved in these 22 patients was a complete response (CR) in 2 patients, marrow complete response (mCR, with incomplete count recovery) in 6, stable disease in 8, and progressive disease in 6 (Table 2). The overall response rate (ORR, CR + mCR) of evaluable patients was 36% and the intent-to-treat overall response rate was 29%. Of the 6 patients with mCR, 4 had hematologic improvement; with 3 in platelet count, 2 in hemoglobin, and 1 in neutrophil count.

Of the 6 patients that received prior HMA therapy, there was 1 CR, 1 mCR, 1 stable disease, and 3 progressive diseases, for an ORR of 33% (p = 0.93, versus HMA naïve patients). Of the patients treated at dose level 3 of plerixafor 560 µg/kg/day with G-CSF, the ORR was 4/5 evaluable patients, with 1 patient having a CR, 3 with marrow CR, and 1 stable disease. For the expansion cohort of 7 patients treated with plerixafor 560 µg/kg/day and azacitidine, without concurrent G-CSF, there were no responders. Five patients had stable disease and 2 had disease progression after 2 cycles. Of these 7 patients, 2 had prior HMA therapy and 5 were treatment-naïve. Excluding the expansion cohort, the ORR for all evaluable patients receiving plerixafor (any dose), G-CSF, and azacitidine was 53% (8 of 15 evaluable patients).

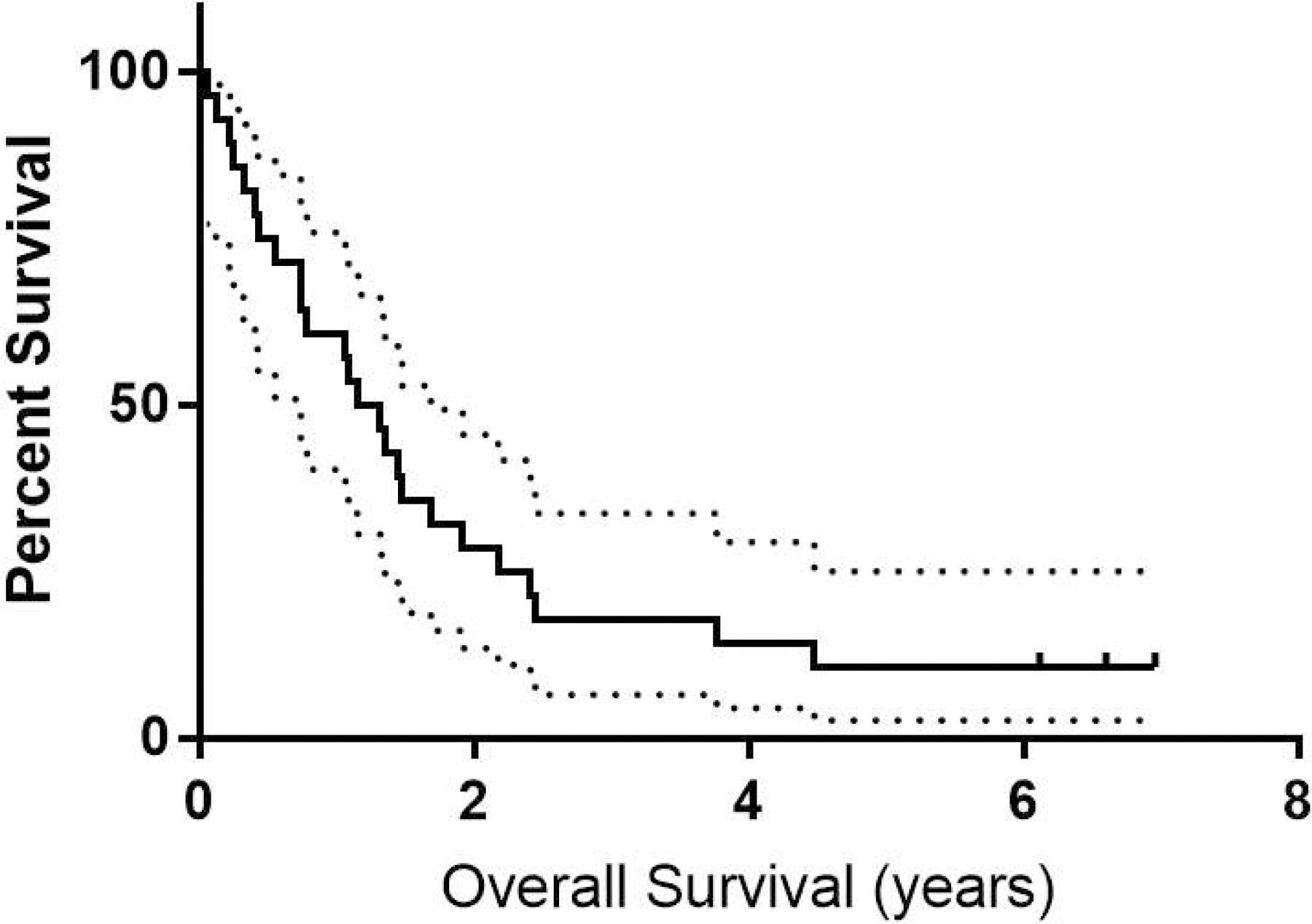

The median overall survival (OS) for the entire study population was 452 days (95% confidence interval 271–794 days) (Figure 4). For responders, the median OS was 511 days (95% CI 423 days with the upper 95% CI not reached) versus 338 days (95% CI 149–880 days) for nonresponders (p=0.7). The median duration of response was 392 days (95% CI 230-NR). The OS of patients who were previously treated with a HMA therapy was 510 days, which was not significantly different from those who were treatment-naïve (p = 0.50). Fifteen of the 28 patients went on to receive an allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) at a median of 90 days after their last study treatment (range 12–184 days). Patients who received a HCT had a median OS of 616 days versus 270 days for those who did not (p < 0.01).

Figure 4.

OS of all patients treated with 95% confidence intervals.

Mobilization of Leukocytes and Blasts

The peripheral blood WBC count increased briskly in the first 3 patients in the original study cohort treated with G-CSF 10 mcg/kg on days 1–8 prior after starting plerixafor 320 µg/kg on day 4 (Figure 2A). In the revised study cohort treated with G-CSF 5 mcg/kg/day on days 1–5, concurrent with the dose escalation of plerixafor, there was a more modest increase in WBC count with no clear dose-response relationship with plerixafor (Figure 2). In the plerixafor 560 µg/kg/day expanded cohort that did not receive G-CSF, there was minimal increase in WBC count or circulating blasts.

Blast mobilization was analyzed by peripheral blood morphology and by FISH using commercially available probes on whole blood mononuclear cells in patients with baseline cytogenetic abnormalities. In the original study cohort of 3 patients treated with G-CSF 10 mcg/kg on days 1–8 prior to starting plerixafor on day 4, there was a substantial increase in blast percentage between 15–50 fold after three days of G-CSF, which then increased an additional 11–40 fold after plerixafor administration on day 4 (Figure 2B). The revised study cohort received G-CSF 5 mcg/kg on day 1–5, concurrent with plerixafor and had a more variable increase in blast count with 10 patients having a greater than 2-fold increase in blast mobilization. Blast mobilization did not appear to correlate with plerixafor dose (p = 0.60) (Figure 2D). Blast mobilization during treatment was associated with response, with patients that mobilized >2-fold having an ORR of 60% versus 17% for those that did not mobilize (p = 0.035). However, this improved response rate did not result in improved OS for patients that mobilized (p = 0.20). Blast mobilization was not associated with patient IPSS score (p = 0.36) and there was a non-significant trend toward better mobilization in patients not previously treated with prior HMA therapy, 52.9% versus 16.7% (p = 0.12).

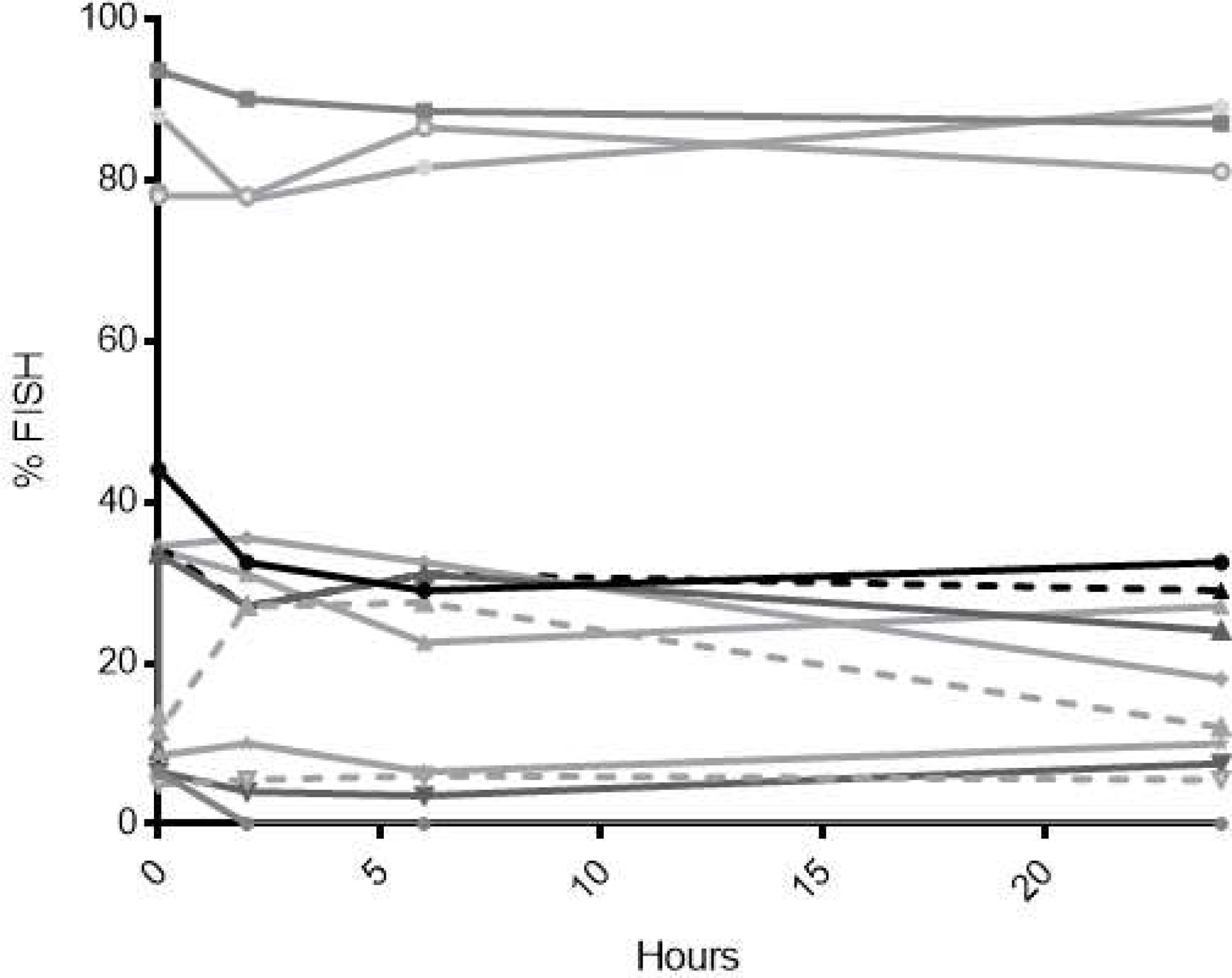

Thirteen patients had informative cytogenetics and FISH was performed at 0, 2, 6 and 24 hours after the day 3 dose of plerixafor in an attempt to evaluate for preferential mobilization of malignant blasts. The percent of blasts with cytogenetic abnormalities in the peripheral blood did not appear to change significantly after plerixafor injection (Figure 3), suggesting that while the absolute number of peripheral blasts increased in response to plerixafor in some patients, the malignant cells did not preferentially mobilize.

Figure 3.

FISH of mononuclear cells in the peripheral blood on Cycle 1 Day 3 after plerixafor administration in 13 patients with informative cytogenetics to evaluate for preferential mobilization of leukemic blasts. Lines depict the percentage of a representative cytogenetic abnormality in an individual patient.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we describe the safety and tolerability of adding plerixafor to G-CSF and azacitidine. While the safety of adding plerixafor to G-CSF is well-established in healthy donors and in patients with myeloma and non-hodgkin’s lymphoma, there remains concerns of leukocytosis when using this combination in patients with high grade hematologic malignancies. Indeed, when plerixafor 320 µg/kg/day was given after priming with 3 days of G-CSF 10 mcg/kg, brisk leukocytosis was observed in 2 of the first 3 patients treated at dose level 1, prompting a protocol amendment. One of these patients had clinical evidence of leukostasis, which resolved after holding further therapy. After the reduction in dose and duration of G-CSF to 5 mcg/kg/day for 5 days, the combination still caused frequent leukocytosis that could be effectively managed with dose delays in 5 patients. In the expanded cohort treated with plerixafor 560 µg/kg/day without G-CSF, minimal leukocytosis or blast mobilization was observed, suggesting the combination of G-CSF with plerixafor is more potent at mobilizing MDS patients than plerixafor alone. Since normal hematopoietic cells can also be mobilized and may be sensitized to the effects chemotherapy, there is a possibility of prolonging cytopenias with this combination, although this was not observed in this study. While other studies in AML have suggested FISH-positive blasts may be preferentially mobilized with the combination of plerixafor and G-CSF, this was not observed in this trial.[33] A number of explanations could account for this finding, first being the small numbers in this trial, the effect of different chemotherapies on mobilization when used with plerixafor and G-CSF, or the lower blast burden seen in MDS compared to AML.

This study supports our hypothesis that adding plerixafor to G-CSF mobilizes MDS blasts in patients with high risk MDS. The concept of G-CSF priming in hematopoietic malignancies has been extensively studied over the last few decades, where it was shown to reduce duration of neutropenia and infectious complications.[18, 35, 36, 37] Although the reported anti-leukemic efficacy of G-CSF priming has been mixed, there are several studies demonstrating improvements in response rate and DFS when used with intensive chemotherapy for induction or salvage of myeloid malignancies.[17, 18, 19] The mechanism of action is presumed to be G-CSF activation of metabolic processes and blast proliferation, thereby sensitizing them to cytotoxic therapy. G-CSF mobilizes normal and leukemic stem cells by down-regulating CXCL12 mRNA and protein expression in the perivascular niche of the marrow, disrupting homing and retention of stem cells and the interaction with other cell surface molecules that cause stromal-mediated chemo-resistance. Plerixafor acts synergistically with G-CSF to mobilize stem cells in autologous donors but also has a second potential mechanism of action by preventing stem cell factor (SCF)- induced internalization of CXCR4 thus disrupting downstream signaling through the PI3K-ADK and MAPK pro-survival pathways.[32]

Fifty three percent of evaluable patients responded to plerixafor, G-CSF and azacitidine in this study, which compares favorably to azacitidine alone.[2] An association between blast mobilization and response was observed that has been previously reported by other groups using plerixafor with decitabine.[38] Interestingly, responses were seen at all dose levels of plerixafor with G-CSF, but no responses were seen in the seven patients enrolled at the MTD of plerixafor 560 µg/kg/day without G-CSF. While these are small numbers and most responses were mCR, it suggests clinical response may be improved with dual targeting of the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis with both G-CSF and plerixafor. Other studies have demonstrated increased surface expression of CXCR4 on AML blasts after the administration of plerixafor, which is felt to be due to the ability of plerixafor to block ligand induced internalization of CXCR4.[32, 33] This increase in CXCR4 expression may be abrogated with G-CSF administration, leading to improved response.

Another group has administered plerixafor plus ten day decitabine in elderly patients with AML, showing an ORR of 43%, which was similar to the response published by the same group using decitabine without plerixafor.[38, 39] Interestingly, when plerixafor was combined with decitabine, blast mobilization was observed that was also significantly associated with clinical response. However, the largest predictor of response to decitabine and plerixafor was prior HMA exposure. In our study, responses were also seen in patients who were previously treated with HMAs, although comparison of response rates is limited due to small numbers. While this may not be a real difference, the mechanisms of chemoresistance in MDS are poorly understood and may be different between different HMAs. These mechanisms are likely at least in part due to the complex interactions between MDS blasts and the bone marrow microenvironment and may be susceptible to dual targeting to the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis by plerixafor and G-CSF, restoring HMA-sensitivity to some individuals.

Combining the CXCR4/CXCL12 inhibitor plerixafor with G-CSF and azacitidine is an intriguing approach to improving responses in high grade MDS. This trial demonstrates the safety and feasibility of this strategy, and its ability to mobilize MDS blasts. The response rates observed in this study are encouraging and warrant further study.

KEY POINTS.

Plerixafor and G-CSF can be safely combined with azacitidine for 5 days in patients with MDS.

The overall response rate of 53% for evaluable patients with this regimen is higher than expected and more responses were seen in patients with blast mobilization.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri, for the use of their core facilities. The Siteman Cancer Center is supported in part by Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA91842 from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

Research reported in this publication was supported by research funding from Sanofi (JFD), National Institutes of Health grants R01 CA152329 (JFD), R21 CA141523 (JFD), R35 1R35CA210084 (JFD), and 5K12HL08710703 (MAS) and the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1 TR000448 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH. Support also received by MAS from CALGB/Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology Foundation. This trial was developed with the support of the American Society of Hematology Clinical Research Training Institute.

The authors would like to thank the late J Evan Sadler, M.D., Ph.D., Monica Bessler, M.D., Ph.D., and Matthew Walter, M.D. for critical feedback and mentoring.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

EH, TF, JR, LG, KM, SC, WCE, KT, RR, SK, AG, CA, AFC, KSG, RV, PW and JFD have declared that no relevant conflict of interest exists. MAS, MPR, GLU, and RV report receiving honoraria from Sanofi. RV has received honoraria from Bristol Myers Squibb.

References

- 1.Mufti GJ. Pathobiology, classification, and diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2004. December;17(4):543–57. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, et al. Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a randomised, open-label, phase III study. Lancet Oncol 2009. March;10(3):223–32. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverman LR, Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, et al. Continued azacitidine therapy beyond time of first response improves quality of response in patients with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer 2011. June 15;117(12):2697–702. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cojoc M, Peitzsch C, Trautmann F, et al. Emerging targets in cancer management: role of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis. Onco Targets Ther 2013;6:1347–61. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S36109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blau O Bone marrow stromal cells in the pathogenesis of acute myeloid leukemia. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2014;19:171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colmone A, Amorim M, Pontier AL, et al. Leukemic cells create bone marrow niches that disrupt the behavior of normal hematopoietic progenitor cells. Science 2008. December 19;322(5909):1861–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1164390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayala F, Dewar R, Kieran M, et al. Contribution of bone microenvironment to leukemogenesis and leukemia progression. Leukemia 2009. December;23(12):2233–41. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konopleva MY, Jordan CT. Leukemia stem cells and microenvironment: biology and therapeutic targeting. J Clin Oncol 2011. February 10;29(5):591–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.0904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azizidoost S, Babashah S, Rahim F, et al. Bone marrow neoplastic niche in leukemia. Hematology 2014. June;19(4):232–8. doi: 10.1179/1607845413Y.0000000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cogle CR, Saki N, Khodadi E, et al. Bone marrow niche in the myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Res 2015. October;39(10):1020–7. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rombouts EJ, Pavic B, Lowenberg B, et al. Relation between CXCR-4 expression, Flt3 mutations, and unfavorable prognosis of adult acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2004. July 15;104(2):550–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konoplev S, Rassidakis GZ, Estey E, et al. Overexpression of CXCR4 predicts adverse overall and event-free survival in patients with unmutated FLT3 acute myeloid leukemia with normal karyotype. Cancer 2007. March 15;109(6):1152–6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spoo AC, Lubbert M, Wierda WG, et al. CXCR4 is a prognostic marker in acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood 2007. January 15;109(2):786–91. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng Z, Samudio IJ, Munsell M, et al. Inhibition of CXCR4 with the novel RCP168 peptide overcomes stroma-mediated chemoresistance in chronic and acute leukemias. Mol Cancer Ther 2006. December;5(12):3113–21. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tavor S, Eisenbach M, Jacob-Hirsch J, et al. The CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 impairs survival of human AML cells and induces their differentiation. Leukemia 2008. December;22(12):2151–5158. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Patel S, Abdelouahab H, et al. CXCR4 inhibitors selectively eliminate CXCR4-expressing human acute myeloid leukemia cells in NOG mouse model. Cell Death Dis 2012;3:e396. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowenberg B, van Putten W, Theobald M, et al. Effect of priming with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on the outcome of chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2003. August 21;349(8):743–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohno R, Naoe T, Kanamaru A, et al. A double-blind controlled study of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor started two days before induction chemotherapy in refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Kohseisho Leukemia Study Group. Blood 1994. April 15;83(8):2086–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofmann WK, Heil G, Zander C, et al. Intensive chemotherapy with idarubicin, cytarabine, etoposide, and G-CSF priming in patients with advanced myelodysplastic syndrome and high-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol 2004. August;83(8):498–503. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0889-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petit I, Szyper-Kravitz M, Nagler A, et al. G-CSF induces stem cell mobilization by decreasing bone marrow SDF-1 and up-regulating CXCR4. Nat Immunol. 2002. July;3(7):687–94. doi: 10.1038/ni813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christopher MJ, Liu F, Hilton MJ, et al. Suppression of CXCL12 production by bone marrow osteoblasts is a common and critical pathway for cytokine-induced mobilization. Blood 2009. August 13;114(7):1331–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broxmeyer HE, Orschell CM, Clapp DW, et al. Rapid mobilization of murine and human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. J Exp Med 2005. April 18;201(8):1307–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiPersio JF, Stadtmauer EA, Nademanee A, et al. Plerixafor and G-CSF versus placebo and G-CSF to mobilize hematopoietic stem cells for autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood 2009. June 4;113(23):5720–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiPersio JF, Micallef IN, Stiff PJ, et al. Phase III prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of plerixafor plus granulocyte colony-stimulating factor compared with placebo plus granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for autologous stem-cell mobilization and transplantation for patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2009. October 1;27(28):4767–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schroeder MA, Rettig MP, Lopez S, et al. Mobilization of allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell donors with intravenous plerixafor mobilizes a unique graft. Blood 2017. May 11;129(19):2680–2692. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-739722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YB, Le-Rademacher J, Brazauskas R, et al. Plerixafor alone for the mobilization and transplantation of HLA-matched sibling donor hematopoietic stem cells. Blood Adv 2019. March 26;3(6):875–883. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018027599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang R, Pu J, Guo J, et al. The biological behavior of SDF-1/CXCR4 in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Med Oncol 2012. June;29(2):1202–8. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-9943-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Guo Q, Zhao H, et al. Expression of CXCR4 is an independent prognostic factor for overall survival and progression-free survival in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Med Oncol 2013. March;30(1):341. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y, Zhao H, Zhao D, et al. SDF-1/CXCR4 axis in myelodysplastic syndromes: correlation with angiogenesis and apoptosis. Leuk Res 2012. March;36(3):281–6. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeng Z, Shi YX, Samudio IJ, et al. Targeting the leukemia microenvironment by CXCR4 inhibition overcomes resistance to kinase inhibitors and chemotherapy in AML. Blood 2009. June 11;113(24):6215–24. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nervi B, Ramirez P, Rettig MP, et al. Chemosensitization of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) following mobilization by the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100. Blood 2009. June 11;113(24):6206–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uy GL, Rettig MP, Motabi IH, et al. A phase 1/2 study of chemosensitization with the CXCR4 antagonist plerixafor in relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2012. April 26;119(17):3917–24. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-383406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konopleva M, Benton CB, Thall PF, et al. Leukemia cell mobilization with G-CSF plus plerixafor during busulfan-fludarabine conditioning for allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015. July;50(7):939–946. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 2016. May 19;127(20):2391–405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heil G, Hoelzer D, Sanz MA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study of filgrastim in remission induction and consolidation therapy for adults with de novo acute myeloid leukemia. The International Acute Myeloid Leukemia Study Group. Blood 1997. December 15;90(12):4710–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Godwin JE, Kopecky KJ, Head DR, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in elderly patients with previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest oncology group study (9031). Blood 1998. May 15;91(10):3607–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ossenkoppele GJ, van der Holt B, Verhoef GE, et al. A randomized study of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor applied during and after chemotherapy in patients with poor risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a report from the HOVON Cooperative Group. Dutch-Belgian Hemato-Oncology Cooperative Group. Leukemia 1999. August;13(8):1207–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roboz GJ, Ritchie EK, Dault Y, et al. Phase I trial of plerixafor combined with decitabine in newly diagnosed older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2018. 10/26/received04/27/ accepted 05/03/epreprint;103(8):1308–1316. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.183418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritchie EK, Feldman EJ, Christos PJ, et al. Decitabine in patients with newly diagnosed and relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia & lymphoma 2013. 02/07;54(9):10.3109/10428194.2012.762093. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.762093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]