Abstract

Research Question:

Is the karyotype of the first clinical miscarriage (CM) in an infertile patient predictive of the outcome of the subsequent pregnancy?

Design:

Retrospective cohort study of infertile patients undergoing manual vacuum aspiration with chromosome testing at the time of the first (index) CM with a genetic diagnosis and a subsequent pregnancy. Patients treated at two academic-affiliated fertility centers from 1999–2018 were included. Patients utilizing preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy were excluded. Main outcome was live birth in the subsequent pregnancy.

Results:

100 patients with euploid CM and 151 patients with aneuploid CM in the index pregnancy were included. Patients with euploid CM in the index pregnancy had a live birth (LB) rate of 63% in the subsequent pregnancy compared to 68% among patients with aneuploid CM (aOR 0.75, CI .47–1.39, p=0.45, logistic regression model adjusting for age, parity, BMI, and mode of conception). In a multinomial logistic regression model with three outcomes (LB, CM, or biochemical miscarriage (BM)), euploid CM for the index pregnancy was associated with similar odds of CM in the subsequent pregnancy compared to aneuploid CM for the index pregnancy (32% vs 24%, respectively, aOR 1.49, CI 0.83–2.70, p=0.19). Euploid CM for the index pregnancy was not associated with likelihood of BM in the subsequent pregnancy compared to aneuploid CM (5% vs 8%, respectively, aOR 0.46, CI 0.14–1.55, p=0.21).

Conclusion:

Prognosis after a first CM among infertile patients is equally favorable among patients with euploid and aneuploid karyotype, and independent of the karyotype of the pregnancy loss.

Keywords: pregnancy loss, infertility, clinical miscarriage, biochemical pregnancy, genetic testing, karyotype

Introduction

Clinical miscarriage (CM) is common, occurring in 10–20% of clinically recognized pregnancies (Warburton 1987, Wilcox et al 1988). The majority of CMs are attributed to embryonic chromosomal abnormalities occurring on a random basis, with an increasing frequency noted with advancing maternal age (Boué et al 1975, Edmonds et al 1982, Hassold and Chiu 1985, Simpson 1980, Stephenson et al 2002). In a 2019 Practice Committee document, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) states “Each pregnancy loss merits careful review to determine whether specific evaluation of the woman or couple may be appropriate (ASRM Committee Opinion 2020).” The ASRM also notes in a 2012 Practice Committee document that “testing of the products of conception may also be of psychological value to the couple (ASRM Committee Opinion 2012).” Genetic testing of products of conception (POCs), however, is not recommended until after the second consecutive early pregnancy loss (ACOG Practice Bulletin 2018). In patients with consecutive CMs, genetic testing of POCs has been shown to be cost-effective, provide closure for the patient and partner to understand why their pregnancy ended in CM, and equips the physician to more effectively guide future management (ACOG Practice Bulletin 2018, Ogasawara et al 2000, Wilcox et al 1988). In the setting of recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL), euploid CM is a negative prognostic indicator (Stephenson et al 2002). The frequency of euploid embryonic karyotype has been shown to significantly increase with the number of prior CMs, and a euploid CM is associated with lower odds of subsequent live birth among RPL patients (Carp et al 2001, Ogasawara et al 2000, Wolf and Horger 1995).

There is ample evidence of the emotional toll of miscarriages in the literature (Cumming et al 2007, Farren et al 2020). Although clinical practices and the accompanying guidelines treat patients with recurrent losses as distinct from those with sporadic miscarriage (ACOG Practice Bulletin 2018, ASRM Committee Opinion 2012), from a patients’ perspective, each pregnancy loss is impactful and can be devastating (Lee and Slade 1996). The psychological sequelae of miscarriage are often overlooked and women experience high levels of post-traumatic stress, anxiety and depression lasting several months after first time and recurrent early pregnancy losses (Farren et al 2020). During these times, clinicians frequently face questions from patients after a single miscarriage regarding the need for and utility of additional testing. The prognostic value of the karyotype of a first-time clinical miscarriage is not known. The objective of this study was to determine if the karyotype of the first CM is predictive of the outcome of the subsequent pregnancy.

Materials and Methods:

Patients

This was a retrospective cohort study of infertile patients who underwent manual vacuum aspiration and chromosome testing of POCs at the time of their first CM and subsequently became pregnant (ending in live birth, CM, or biochemical pregnancy loss) from 1999–2018 at two academic fertility centers. The index pregnancy was the first CM experienced by all patients included in the study.

Medical records were reviewed for demographic information, obstetric history and fertility treatment received. Only the pregnancy immediately following the index pregnancy was included for outcome analysis. All patient ages and infertility diagnoses were included. The following modes of conception were included: spontaneous or natural cycle with or without intra-uterine insemination (NC), controlled ovarian hyperstimulation and intrauterine insemination or timed intercourse (non-IVF COH), in vitro fertilization (IVF) without preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A). Patients utilizing PGT-A to conceive either the initial or subsequent pregnancy were excluded. Patients utilizing donor oocytes or gestational carriers were included only if the index pregnancy and subsequent pregnancy used the same oocyte source or gestational carrier. For patients utilizing donor oocytes, the age of the oocyte donor was reported. Patients performing natural cycle IVF were not included. Patients were excluded if chromosome testing of CM tissue did not provide a genetic diagnosis, if testing confirmed maternal cell contamination, or if a subsequent pregnancy was not attained after the first CM. Prior to the first miscarriage, all patients underwent a standard infertility evaluation including assessment of ovarian reserve, assessment of tubal patency, pelvic ultrasound to evaluate ovarian and uterine morphology, and assessment of thyroid function. All patients were managed in a subsequent pregnancy per standard clinical protocols. Patients were not offered anticoagulation treatment after a single miscarriage regardless of karyotype. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both centers.

Study Definitions

The primary outcome was live birth and the secondary outcome was pregnancy loss. The secondary outcome was further subdivided into CM and biochemical miscarriage (BM). Pregnancy loss was defined as a spontaneous termination of pregnancy from conception (defined as serum quantitative hCG level >5mIU/mL) through twenty weeks gestational age. BM was defined as a miscarriage after a serum hCG level >5mIU/mL without a gestational sac on transvaginal ultrasound before 12 6/7 weeks’ gestation. CM was defined as a miscarriage after a serum hCG level >5mIU/mL and subsequent documented gestational sac on transvaginal ultrasound before 12 6/7 weeks’ gestation. Birth of a neonate at or beyond 24 weeks’ gestation, documented by patient report or medical record review, was considered a live birth (LB).

Chromosome Testing of CM Specimens

Patients in both fertility centers routinely had transvaginal ultrasounds performed between 6 and 8 weeks’ gestation to confirm a viable intrauterine pregnancy prior to transferring care to an obstetrician. Patients diagnosed with a CM by transvaginal ultrasound were offered treatment options of manual vacuum aspiration, medical management with misoprostol, or expectant management. All patients with CM were routinely offered chromosome testing of specimens. In patients electing to undergo manual vacuum aspiration, the products of conception were carefully examined and the villi were separated according to a previously published technique to minimize maternal cell contamination (Murugappan et al 2014). Chromosome testing of villi was performed using either cytogenetic testing or molecular testing. The decision to perform molecular testing or cytogenetic testing of villi was made by the patient’s physician according to the standard of clinical care at the time of management as well as shared decision making with the patient incorporating cost and pros/cons of each testing modality.

Cytogenetic testing was performed by a university reference laboratory using standard cell culture and metaphase chromosome analysis using the Giemsa-trypsin-wrights banding method. Molecular testing was performed using single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarray at a commercial reference laboratory (Natera™). This testing platform is described in detail elsewhere (Lathi et al 2012, Shah et al 2017). In brief, a Parental Support Algorithm™ is used to determine the number and origin of each chromosome. Comparison of SNPs between maternal and product of conception samples is used to identify maternal cell contamination as well as parental origin of aneuploidy and unbalanced chromosomal rearrangements. Patients with a result of 46,XX on initial cytogenetic testing of POC were counseled that this result is inconclusive because maternal cell contamination (MCC) cannot be excluded by this testing modality (Bell et al 1999). These patients were offered additional molecular testing of the villi to confirm the euploid CM.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics were compared between those with euploid CM and aneuploid CM in the index pregnancy using t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables, Mann-Whitney U tests for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and Chi-Square Tests or Fisher’s Exact tests for categorical variables. Rates of LB, CM, and BM were calculated for euploid and aneuploid index pregnancy losses.

We modeled the association between index pregnancy CM karyotype and subsequent pregnancy outcome using multinomial logistic regression to account for three possible discrete outcomes (LB, CM, or BM). LB was used the reference outcome. The model adjusted for maternal age, overweight/obesity (≥25 kg/m2), and mode of conception for subsequent pregnancy (IVF, non-IVF COH, or spontaneous/natural cycle). As a secondary analysis, we grouped CM and BM and evaluated the association between index pregnancy CM karyotype and LB, versus any pregnancy loss, using binomial logistic regression. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25. All tests were 2-sided and p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sample Size

Prior studies reported subsequent pregnancy CM rates of 55% and 29% among patients with recurrent euploid pregnancy loss and recurrent aneuploid pregnancy loss, respectively (12,13). Based on live birth rates of 45% and 71% among patients with recurrent euploid and aneuploid pregnancy loss, we calculated that our study would need 118 patients (59 per group) to detect an absolute difference of 25% with 80% power and 2-tailed alpha of 0.05.

Results

Cohort Characteristics

A total of 1,353 patients undergoing manual vacuum aspiration for missed abortion were screened for potential study inclusion. 19% (n=251) of patients met the study criteria and were included. Of the patients undergoing manual vacuum aspiration who did not meet study criteria, the majority (70%) were non-first miscarriages, and the remaining 30% of patients did not achieve a subsequent pregnancy. 100 patients with a euploid CM in the index pregnancy and 151 patients with an aneuploid CM in the index pregnancy were included. Patients with a euploid and aneuploid CM for the index pregnancy were similar ages on average at the time of index pregnancy (34.5±4.1 years vs 34.8±4.3 years, respectively, p=0.55). Patients with euploid and aneuploid CM for the index pregnancy had similar mean BMI (24.2±3.8 kg/m2 vs 24.3±4.6 kg/m2, p=0.80) (Table 1). 14% (n=14) of patients had at least one prior live birth in the euploid group while 27% (n=41) of patients had at least one prior live birth in the aneuploid group (p=0.66). For all patients included in the study, the index pregnancy was their first CM. 7% (n=7) of patients in the euploid group had a prior BM while 6.6% (n=10) of patients in the aneuploid group had a prior BM (p=0.91). 1% (n=1) of patients in the euploid group had a prior ectopic pregnancy while 3.3% (n=5) of patients in the aneuploid group had a prior ectopic pregnancy (p=0.24). In pregnancies with a fetal pole, mean fetal crown rump length was significantly smaller for euploid compared to aneuploid clinical miscarriages (6.9±8.8 mm vs 10.5±10.0 mm (all singleton), p=0.03). Only 2 patients in the euploid karyotype and 3 patients in the aneuploid karyotype for first miscarriage used an egg donor to conceive both the index and subsequent pregnancy.

Table 1.

Demographics of patients comparing those with euploid versus aneuploid miscarriage.

| n=100 | n=151 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD), range | 24–43 | 23–42 | |

| Mean (SD), range | 18.0–34.4 | 17.9–42.3 | |

| Prior live birth, n (%) | 14 (14) | 41 (27) | 0.66** |

| Prior biochemical miscarriage†, n (%) | 7 (7.0) | 10 (6.6) | 0.91** |

| Prior ectopic pregnancy, n(%) | 1 (1.0) | 5 (3.3) | 0.24** |

| Mean (SD), range | 0.8–53 | 2–72 | |

| Mode of conception, n (%) | |||

| IVF | 54 (54%) | 68 (45%) | |

| Non-IVF COH | 33 (33%) | 67 (44%) | |

| Spontaneous or natural cycle | 13 (13%) | 16 (11%) | |

| Infertility Diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Ovulatory | 25 (25%) | 44 (29%) | |

| Tubal Factor | 8 (8%) | 8 (5%) | |

| Uterine Factor | 5 (5%) | 9 (6%) | |

| Endometriosis | 8 (8%) | 10 (7%) | |

| Male Factor | 23 (23%) | 38 (25%) | |

| Unexplained | 42 (42%) | 53 (35%) | |

| Subsequent Pregnancy | |||

| Mean (SD), range | 26–44 | 23–44 | |

| Mode of conception, subsequent pregnancy, n (%) | |||

| IVF | 57 (57%) | 77 (51%) | |

| Non-IVF COH | 29 (29%) | 53 (35%) | |

| Spontaneous or natural cycle | 14 (14%) | 21 (14%) | |

Student’s t-test

Chi-square test

CRL=crown rump length

For all patients included in the study, the index pregnancy was their first clinical miscarriage.

Among patients with an aneuploid karyotype, 93 patients had molecular testing of villi performed using a SNP microarray and 58 patients had cytogenetic testing of villi. Among patients with a euploid karyotype, 41 patients had molecular testing of villi and 59 had cytogenetic testing of villi. Of the 57 patients with a 46,XX karyotype result from POC genetic testing, 18 resulted from molecular testing and 39 resulted from cytogenetic testing without a subsequent SNP microarray testing to rule out MCC. Inability to test for MCC was because the provider and/or patient elected not to perform a SNP microarray. The XX:XY ratio among patients with a euploid CM was 1.4:1.0.

Among patients with euploid CM for the index pregnancy, 54% conceived that pregnancy with IVF without PGT-A, 33% conceived with non-IVF COH and 13% conceived during a natural cycle. Among patients with aneuploid CM for the index pregnancy, 45% conceived that pregnancy with IVF without PGT-A, 44% conceived with non-IVF COH and 11% conceived during a natural cycle. Mode of conception was similar among pregnancies with euploid and aneuploid karyotype for the index pregnancy (p=0.20, Chi-square test). Infertility diagnoses (not mutually exclusive) are detailed in Table 1 and were not significantly different between the groups; the most common infertility diagnoses were unexplained (42% v 35% in euploid v aneuploid karyotype groups) and ovulatory factor (25% v 29% in euploid v aneuploid karyotype groups).

For the subsequent pregnancy, patients with euploid and aneuploid CM for the index pregnancy were similar ages on average (35.4±4.0 years vs 35.6±4.3 years, respectively, p=0.71). For the subsequent pregnancy, 57% of patients with a euploid CM for the index pregnancy utilized IVF, 29% utilized non-IVF COH and 11% conceived spontaneously or during a natural cycle. For the subsequent pregnancy, 51% of patients with aneuploid CM for the index pregnancy utilized IVF, 35% utilized non-IVF COH and 14% conceived spontaneously or during a natural cycle. There was a non-significant difference among modes of conception for the subsequent pregnancy between patients with aneuploid and euploid CM for the index pregnancy (p=0.71, Chi-square test). Between the index and subsequent pregnancy, a similar proportion of patients utilized IVF and other modes of conception (p=0.83 for euploid karyotype in index pregnancy, p=0.24 for aneuploid karyotype in index pregnancy).

Clinical outcomes

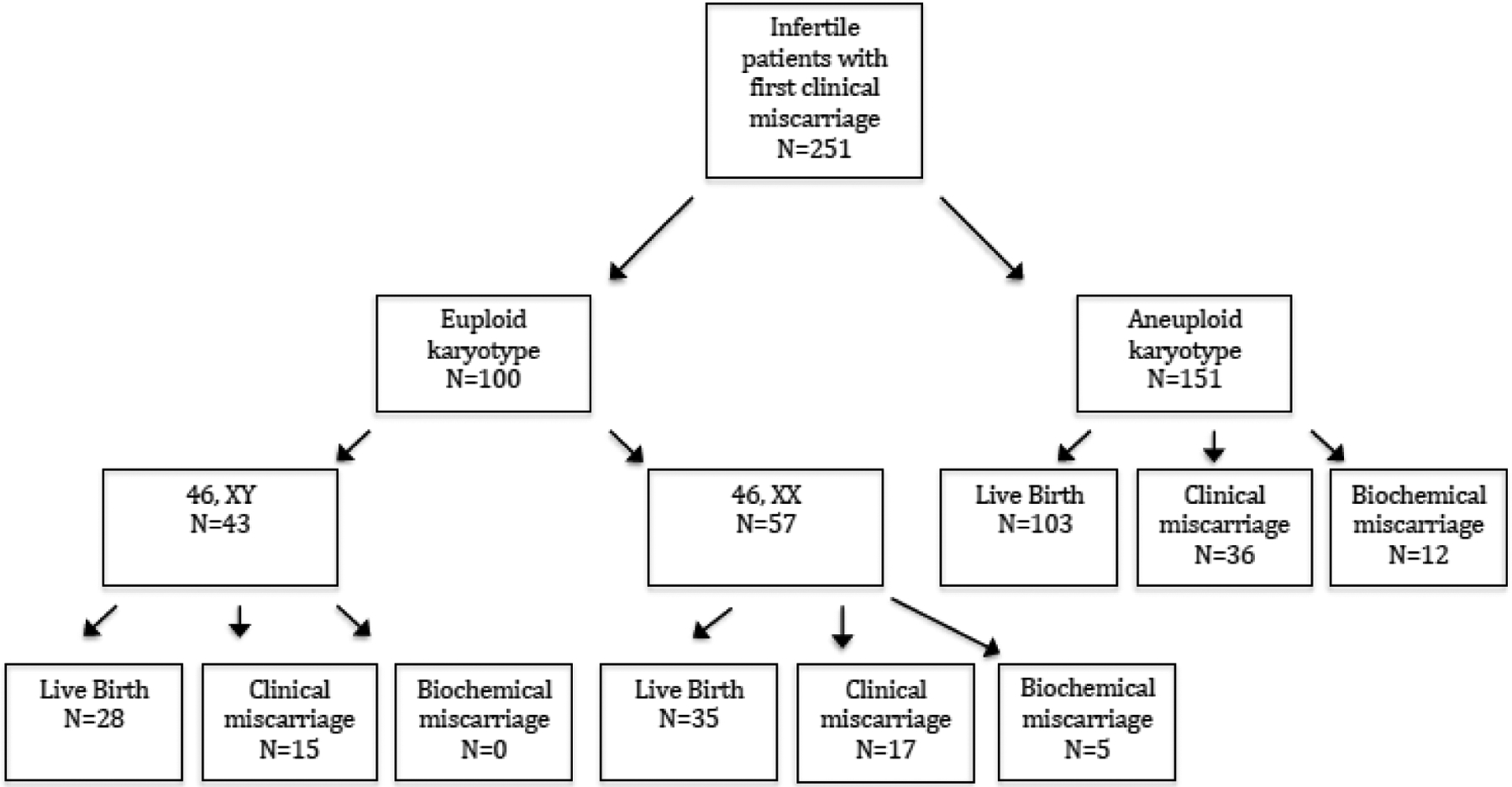

A flowchart including clinical outcomes among patients with euploid and aneuploid CM for the index pregnancy is shown in Figure 1. Among 100 patients with a euploid CM for the index pregnancy, 63 had a subsequent LB (63%), 32 had a CM (32%), and 5 had a BM (5%). Among 151 patients with an aneuploid CM for the index pregnancy, 103 (68%) had a subsequent LB, 36 had a subsequent CM (24%), and 12 had a subsequent BM (8%). There were no pregnancy losses after 20 weeks gestation in either group. In a binomial logistic regression model, euploid CM for the index pregnancy, compared with aneuploid CM, was not associated with the odds of live birth (aOR 0.75, CI 0.47–1.39, p=0.45). In a multinomial logistic regression model to assess CM and BM separately compared with live birth, euploid CM for the index pregnancy was not associated with the odds of CM (aOR 1.49, CI 0.83–2.70, p=0.19) or BM (aOR 0.46, CI 0.14–1.55, p=0.21) in the subsequent pregnancy (Table 2). Excluding patients with prior BM did not change the results of the analysis. Among 90 patients in the euploid karyotype subgroup without a prior BM, there were 58 subsequent LB (62%), 32 subsequent CM (34%) and 5 had a subsequent BM (3%). Among 141 patients in the aneuploid karyotype subgroup without a prior BM, there were 94 subsequent LB (67%), 37 had a subsequent CM (26%) and 9 had a subsequent BM (6%). Live birth (p=0.73), CM (p=0.13) and BM rates (p=0.31) were similar between subgroups. 17 patients in the euploid karyotype group and 36 patients in the aneuploid karyotype group had a prior live birth. Excluding patients with a prior live birth did not change the result of the analysis, and live birth outcome was similar among patients with a prior live birth regardless of karyotype of the index pregnancy (p=0.66).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of clinical outcomes from genetic testing of first miscarriage to outcome of subsequent pregnancy.

Table 2.

Association between euploid, versus aneuploid, clinical miscarriage in the index pregnancy and pregnancy loss (any) and pregnancy loss subtypes (clinical miscarriage or biochemical pregnancy loss) in the subsequent pregnancy.

| Outcome of subsequent pregnancy | Crude OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live birth ** | 0.82 (0.48–1.39) | 0.46 | 0.75 (0.47–1.39) | 0.45 |

| Pregnancy loss, subtypes† | ||||

| Clinical miscarriage | 1.40 (0.79–2.47) | 0.25 | 1.49 (0.83–2.70) | 0.19 |

| Biochemical miscarriage | 0.54 (0.17–1.75) | 0.30 | 0.46 (0.14–1.55) | 0.21 |

Adjusted for maternal age, body mass index, parity, and mode of conception

Binomial logistic regression model, pregnancy loss (any) used as reference outcome

Multinomial logistic regression model, live birth used as reference outcome

Association between ploidy of index CM and subsequent CM

Among the 32 patients with euploid CM in the index pregnancy who went on to have another CM, karyotype of that CM was known for 16 patients. Of these 16 miscarriages, 9 (56%) were aneuploid. Among the 37 patients with aneuploid CM in the index pregnancy who went on to have another CM, karyotype of that CM was known for 19 patients. Of these 19 miscarriages, 12 (63%) were aneuploid. Among patients with recurrent euploid CM, MCC was ruled out for all 46,XX karyotypes. Among patients with initial aneuploid CM and subsequent euploid CM, 5 POC specimens with karyotype 46,XX did not have MCC ruled out. There was no association with ploidy of the index CM and ploidy of the subsequent CM (p=0.32, Fisher’s Exact Test).

Conclusion

Although chromosomal abnormalities are widely recognized as the most common cause of CM ((Boué et al 1975, Warburton et al 1964, Wilcox et al 1988), only a small fraction of first trimester CMs are tested for chromosomal anomalies (McNally et al 2016). In patients with consecutive CMs, genetic testing of POCs is more frequently performed and has been shown to be cost-effective, provide closure for the patient and partner to understand, and is of prognostic value (ASRM Committee Opinion 2012, Stephenson et al 2002, Wolf and Horger 1995). Among RPL patients, a euploid CM is associated with lower odds of subsequent live birth (Carp et al 2001, Ogasawara et al 2000, Warburton et al 1987). The goal of this study was to determine if genetic testing of the first CM predicts the outcome of the subsequent pregnancy.

Among infertile patients with both euploid and aneuploid karyotype at the time of first CM, subsequent pregnancy outcomes were overall good, with 63% of patients achieving a live birth after euploid index CM and 68% of patients achieving live birth after aneuploid index CM. Odds of all clinical outcomes including live birth, clinical miscarriage and biochemical pregnancy loss were similar after euploid or aneuploid CM in the index pregnancy in our patient population. Despite the frequency of miscarriages, their psychological sequelae are often overlooked and women experience high levels of post-traumatic stress, anxiety and depression lasting several months after an early pregnancy loss (Cumming et al 2007, Farren et al 2020, Klock et al 1997, Lee and Slade 1996, McNally et al 2016, Nikcevic et al 1998). While clinical guidelines do not recommend a workup until after the second consecutive pregnancy loss, clinicians frequently face questions from patients after a single miscarriage regarding the need for and utility of additional testing. A national survey of 448 women with a first trimester miscarriage revealed that while only 8% underwent chromosome testing at the time of miscarriage, 66% of those who did not undergo testing said they wished they had done so at the time of miscarriage, and 67% said they would still want testing if it were available at the time of the survey (McNally et al 2016). Our findings suggest that patients can be reassured after a first time miscarriage, and that embarking on a resource-intensive clinical or laboratory evaluation after a single miscarriage may not be cost effective or clinically impactful. Furthermore, the overall favorable clinical outcomes among patients with both euploid and aneuploid first miscarriage may help patients recover from the trauma of experiencing a miscarriage.

Among patients with recurrent euploid miscarriages, prognosis is worse. A patient with two euploid CMs has a 23% risk of subsequent CM while a patient with three prior euploid CMs has a 32% risk of subsequent CM. Although clinically rare, a patient with seven prior euploid CMs has a 67% risk of subsequent CM. The etiology of euploid CM is yet to be fully understood. Uterine and embryonic factors are likely contributory, including embryonal genetic aberrations that are not currently routinely detected (Annan et al 2013, Colley et al 2019, Larsen et al 2013). In addition, the contribution of male factors to euploid loss is poorly understood. Among patients with recurrent pregnancy loss, the incidence of euploid CMs is significantly higher (Stephenson et al 2002, Warburton et al 1987), suggesting that CMs have less random etiologies as they increase in frequency. The factors associated with recurrent CM and the risk of euploid CM warrant further study. While pregnancies conceived with PGT-A were excluded from this study to limit confounding of the patient cohorts, the role of PGT-A in first time and recurrent euploid CM also warrants additional study. In addition, the etiology of biochemical miscarriage remains elusive and further studies are warranted to characterize the prognosis of biochemical miscarriage on subsequent pregnancy outcome.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to characterize karyotype and subsequent pregnancy outcome among patients with first time CM. Prior studies have examined the value of chromosome testing in patients with RPL or a heterogeneous cohort of women with first time and recurrent CMs. Our primary finding, that infertile patients with first time euploid and aneuploid CM have an equally favorable prognosis, also limits our statistical power, as pregnancy loss rates were much lower in this patient population compared to patients with recurrent aneuploid or euploid losses. For CM, the minimum detectable odds ratio was 2.17 at 80% power and 2-tailed alpha of 0.05. At the effect level observed (crude OR 1.40), power to detect a true effect was only 29%. Larger scale studies are warranted to further investigate this clinical question.

The inability to test for MCC in 15% (n=39) of our CM specimens is an additional limitation of the study. The patients who did not have MCC testing are primarily from procedures performed prior to 2010 when molecular testing became an option for genetic testing of POC (Lathi et al 2012). Estimates of the prevalence of MCC range from 4–47% with an average of 22% (Lathi et al 2014). Using the average MCC rate, we estimate that 8–9 samples or 5–6% may have unreliable chromosome testing results, which is unlikely to significantly influence the results of our overall analysis. A limitation of data collection is that BMI was available only at the time of index pregnancy and not at the time of subsequent pregnancy. However, mean difference in age at the index and subsequent pregnancy was 6 months and BMI is unlikely to change significantly in this time period. An additional limitation is selection bias inherent to studying a retrospective cohort of infertile patients. This cohort of patients was chosen because as part of routine clinical care, patients in both fertility clinics were offered chromosome testing regardless of number of prior CMs, therefore we could capture patients undergoing testing at the time of the first CM. However, infertile patients who have consecutive CMs are a poorer prognosis group compared to fertile RPL patients. The applicability of our results to a fertile population is not clear. Further studies including infertile and non-infertile women and incorporating consideration of cost as well as psychological aspects of CM management are warranted.

In conclusion, among 251 infertile patients undergoing chromosome testing at the time of first CM, prognosis after a first time miscarriage was equally favorable among patients with euploid and aneuploid karyotype.

Key Message.

Among 251 infertile patients undergoing chromosome testing at the time of first miscarriage, karyotype of the first pregnancy loss did not predict subsequent pregnancy outcome.

Acknowledgments:

The authors acknowledge Dr. Nina Vyas for her contribution to data collection.

Funding:

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH/NICHD (1K12HD103084).

Biography

I am an Instructor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Stanford/NIH/NICHD

Stanford Women’s Reproductive Health Research Career Development Scholar (WRHR K12), Associate Director of the Fellowship in Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility (REI), Director of the ROSE Biobank, and Medical Director of the RENEW Biobank in the Stanford REI Division.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at Pacific Coast Reproductive Society Conference, April 2019, Indian Wells, CA

References:

- Annan JJK, Gudi A, Bhide P, Shah A and Homburg R. Biochemical pregnancy during assisted conception: A little bit pregnant. L Clin Med Res 2013; 5:269–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell KA, Van Deerlin PG, Haddad BR, and Feinberg RF. Cytogenetic diagnosis of “normal 46XX” karyotypes in spontaneous abortions frequently may be misleading. Fertil Steril 1999; 71:334–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boué J, Boué A, and Lazar P. Retrospective and prospective epidemiological studies of 1500 karyotyped spontaneous human abortions. Teratology 1975;12:11–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carp H, Toder V, Aviram A, Daniely M, Mashiach S and Barkai G. Karyotype of the abortus in recurrent CM. Fertil Steril 2001; 75:678–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colley E, Hamilton S, Smith P, Morgan NV, Coomarasamy A and Allen S. Potential genetic causes of CM in euploid pregnancies: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 2019; 25:452–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. Early Pregnancy Loss: ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 200. Obset & Gynecol 2018; 132: e197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming GP, Klein S, Bolsover D, Lee AJ, Alexander DA, Maclean M and Jurgens JD. The emotional burden of miscarriage for women and their partners: trajectories of anxiety and depression over 13 months. BJOG 2007; 114: 1138–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds DK, Lindsay KS, Miller JF, Williamson E, and Wood PJ. Early embryonic mortality in women. Fertil Steril 1982;38:447–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farren J, Jalmbrant M, Falconieri N, Mitchell-Jones N, Bobdiwala S, Al-Memar M, Tapp S, Van Calster B, Wynants L, Timmerman D and Bourne T. Post-traumatic stress, anxiety and depression following miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy: a multi-center, prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020; 4: 367.e1–367.e22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassold T and Chiu D. Maternal age-specific rates of numerical chromosome abnormalities with special reference to trisomy. Hum Genet 1985;70:11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klock SC, Chang G, Hley A, and Hill J. Psychological distress among women with recurrent spontaneous abortions. Psychosomaties 1997; 38:503–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen EC, Christiansen OB, Kolte AM, and Macklon N. New insights into mechanisms behind CM. BMC Med 2013; 11:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathi RB, Gustin SL, Keller J, Maisenbacher MK, Sigurjonsson S, Tao R, and Demko Z. Reliability of 46,XX results on CM specimens: a review of 1,222 first-trimester CM specimens. Fertil Steril 2014; 101:178–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathi RB, Massie JA, Loring M, Demko ZP, Johnson D, Sigurjonsson S, Gemelos G, Rabinowitz M. Informatics enhanced SNP microarray analysis of 30 CM samples compared to routine cytogenetics. PLoS One 2012; 7:e31282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C and Slade P. Miscarriage as a traumatic event: a review of the literature and new implications for intervention. J Psychosomatic Res 1996; 40:235–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally L, Huynh D, Keller J, Dikan J, Rabinowitz M and Lathi RB. Patient experience with karyotyping after first trimester CM: a national survey. J Reprod Med 2016; 61:128–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugappan G, Gustin S and Lathi RB. Separation of CM tissue from maternal decidua for chromosome analysis. Fertil Steril 2014; 102:e9–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikcevic AV, Tunkel SA, and Nicolaides KH. Psychological outcomes following missed abortions and provision of follow-up care. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1998; 11:123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogasawara M, Aoki K, Okada S and Suzumori K. Embryonic karyotype of abortuses in relation to the number of previous CMs. Fertil Steril 2000; 73:300–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Definitions of infertility and pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2020; 11:533–4. [Google Scholar]

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2012; 98:1103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah MS, Cinnioglu C, Maisenbacher M, Comstock I, Kort J, and Lathi RB. Comparison of cytogenetics and molecular karyotyping for chromosome testing of CM specimens. Fertil Steril 2017; 107:1028–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JL. Genes, chromosomes, and reproductive failure. Fertil Steril 1980;33:107–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson MD, Awartani KA, and Robinson WP. Cytogenetic analysis of CMs from couples with recurrent CMs: a case-control study. Hum Reprod 2002; 17:446–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton D and Fraser FC. Spontaneous abortion risks in man: data from reproduction histories collected in a medical genetic unit. Am J Hum Genet 1964;16:1–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton D, Kline J, Stein Z, Hutzler M, Chin A and Hassold T Does the karyotype of a spontaneous abortion predict the karyotype of a subsequent abortion? Evidence from 273 women with two karyotyped spontaneous abortions. Am. J. Hum. Genet 1987; 41:463–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O’Connor JF, Baird DD, Schlatterer JP, Canfield RE, Armstrong EG and Nisula BC. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1988;319:189–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf GC and Horger EO Indications for examination of spontaneous abortion specimens: a reassessment. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 1995; 173:1364–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]