Abstract

Objective

Febrile seizure is a common childhood disorder that affects 2-5% of all children, and is associated with later development of epilepsy and psychiatric disorders. This study determines how the incidence of febrile seizures correlates with birth characteristics, age, sex, and brain development.

Methods

This is a cohort study of all children born Denmark between 1977 and 2011 who were alive at 3 months of age (N = 2,103,232). The Danish National Patient Register was used to identify children with febrile seizures up to 5 years of age. Follow-up ended on 31 December 2016 when all cohort members had potentially reached 5 years of age.

Results

In total, 75,593 (3.59%, 95% CI: 3.57-3.62%) were diagnosed with febrile seizures. Incidence peaked at 16.7 months of age (median: 16.7 months, interquartile range: 12.5-24.0). The 5-year cumulative incidence of febrile seizures increased with decreasing birth weight (<1500 g; 5.42% (95% CI: 4.98-5.88% vs. 3,000-4,000 g; 3.53% (95% CI: 3.50-3.56%)), and with decreasing gestational age at birth (31-32 weeks; 5.90% (95% CI: 5.40-6.44%) vs. 39-40 weeks; 3.56% (95% CI: 3.53-3.60)). Lower gestational age at birth was associated with higher age at onset of a first febrile seizure; an association that essentially disappeared when correcting for age from conception.

Conclusions

The risk of febrile seizures increased with decreasing birth weight and gestational age at birth. The association between low gestational age at birth and age at first febrile seizure suggest that onset of febrile seizures is associated with the stage of brain development.

Keywords: birth weight, gestational age, brain development, febrile seizures and epilepsy

INTRODUCTION

Febrile seizures is a common childhood disorder that affects 2-5% of all children. It is defined as seizures associated with a body temperature above 38°C without serious underlying causes (i.e. head trauma, intracranial infection, or epilepsy) between 3 months and 5 years of age.1-5 Febrile seizures are generally self-limiting and can be categorised as simple (generalised and brief seizures) or complex (focal symptoms and longer duration of seizures).4,6 Long-term co-morbidities include epilepsy7 and neuropsychiatric disorders.8 The development of childhood seizures likely involves a cascade of developmental molecular, cellular and neuronal network alterations responsible for enhanced seizure susceptibility in the developing brain.9-14 These developmental factors in the human brain interplay with environmental factors such as preterm birth,15,16 infections17,18 and seasonality of birth.19 An understanding of these complex interactions may help identify potential therapeutic targets for prevention of febrile seizures and possibly also the association with later development of epilepsy7 and psychiatric disorders.20,21

We studied the risk of febrile seizures in a large population-based sample of children born in Denmark, focusing on the incidence of febrile seizures in relation to age, sex, birth weight, and gestational age at birth.

METHODS

Study design

This is a register-based cohort study of children born in Denmark. The cohort was followed and investigated in the Danish national health registers.

Study population

Utilizing the Danish Civil Registration System,22 we identified a study population of all live-born children born in Denmark between 1 January 1977 and 31 December 2011 who were alive at 3 months of age (n=2,103,232). The Danish Civil Registration System links individual information about a person to his or her identification number in national registers, providing a large database ideally suited for register studies. The Danish Civil Registration System was also used to identify children who died or emigrated from Denmark.

Febrile seizures

From the study population defined above, children with a diagnosis of febrile seizures were identified using the Danish National Patient Register.16,23 This register contains information about all discharges from Danish hospitals since 1977, and on all outpatients since 1995, including diagnostic information based on the International Classification of Diseases (8th revision from 1977 to 1993 (IDC-8) and 10th revision from 1994 to 2016 (IDC-10)). In the present study, children were classified as having had a febrile seizure if they were diagnosed with febrile seizures (either ICD-8: 780-21 or ICD-10: R56.0) between the age of 3 months and 5 years as defined in the 1980 National Institutes of Health initiated consensus statement on febrile seizures.24 Febrile seizure diagnoses were excluded in children with a previous diagnosis of conditions that could be contraindicative of or exclude a febrile seizures diagnosis. These were either a diagnosis of epilepsy (IDC-8: 345, excluding 345.29 or IDC-10: G40.0), cerebral palsy (IDC-8: 343.99, 344.99, ICD-10: G80), intracranial tumours (ICD-8: 191, 225, ICD-10: C70-C71, D32-D33), severe head traumas (ICD-8: 851, 854, ICD-10: S06.1-S06.9) or intracranial infections (ICD-8: 320, 323, ICD-10: G00-G09).1,7,25 Time of onset of the febrile seizure was determined as the first day of hospital or outpatient contact with a febrile seizure diagnosis. The study population was followed until the end of 2016, when all children in the cohort had potentially reached 5 years of age. Children were censored at time of death and emigration.

Assessment of birth characteristics

Information about birth weight and gestational age at birth of children in the study population was obtained from the Danish Medical Birth Registry.26 The birth weight indicates the baby's birth weight measured immediately after birth. (<1,500 g, 1,500-2,499 g, 2,500-2,999 g, 3,000-4,000 g, and 4,000+ g). Gestational age indicates the period from the first day of the mother's last menstrual period before conception to the day the baby is born. Gestational age is usually corrected after early ultrasound scan or at the time of fertility treatment.26 Gestational age was defined by subtracting gestational age at birth from the date of birth i.e. age from conception. From 1978-1996 when gestational age was recorded in full weeks, gestational age in days was estimated as; date of birth – (gestational age in weeks * 7) and from 1997-2011 when gestational age was recorded in days, gestational age was estimated as; date of birth - gestational age. In 1977, gestational age was recorded more imprecisely, and births from 1977 are therefore not included in analyses of gestational age. We defined small for gestational age as children with birth weight <10% percentile for the gestational birth week.

Statistical analyses

All children were followed from 3 months of age, until the day of the first febrile seizure, death, emigration, or the end of follow-up on 31 December 2016. We estimated the sex-specific incidence rate of a first febrile seizure for all ages between 3 months and 5 years (i.e. 60 months). Next, we used competing risk regression to estimate the cumulative incidence of febrile seizure by birth weight and gestational age at birth, while accounting for death as a competing risk. We also estimated the cumulative incidence of febrile seizure by birth weight and gestational age at birth after stratifying on small for gestational age at birth. We used a nonparametric approach based on the sub-distribution hazards for this purpose.27,28 In these models, age of the offspring was used as the underlying time scale. To examine how gestational age at birth influenced the age at onset of febrile seizures, we constructed cumulative density distributions of the age at onset of febrile seizures for children born at gestational week 31-32, 33-34, 35-36, 37-38, 39-40, 41-42, and 43-44, respectively. Age distributions were constructed for age from birth as well as for age from conception. We also constructed age distributions of onset of febrile seizures by age from conception after stratifying on being born small for gestational age.

Sensitivity analyses

Because outpatients and emergency room visits were included in the hospital register in 1995 and because the ICD was changed from ICD8 to ICD10 in 1994, we assessed the cumulative risk of febrile seizures by gestational age and birth weight in two time periods: birth years 1977-1990 and birth years 1995 to 2011.

Ethics committee approval

Analyses were based on pseudo-anonymized data, and the study involved no individual patient contact. The project was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (journal number: 2015-57-0002).

Role of sponsors

The sponsors had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the manuscript.

RESULTS

We identified 75,593 children with febrile seizures out of a total population of 2,103,232 (3.59% (95% confidence interval (CI): 3.57-3.62%)); the overall incidence for girls was 58.9 (95% CI: 58.3-59.5) per 100,000 person months and 71.1 (95% CI: 70.5-71.8) per 100,000 person months for boys, corresponding to a 21% higher risk in boys compared to girls (HR: 1.21 (95% CI: 1.19-1.22)). The median age of first febrile seizure in the entire cohort was 16.7 months, interquartile range (IQR): 12.5-24.0), and 90.9% of the children had their first febrile seizure before 3 years of age.

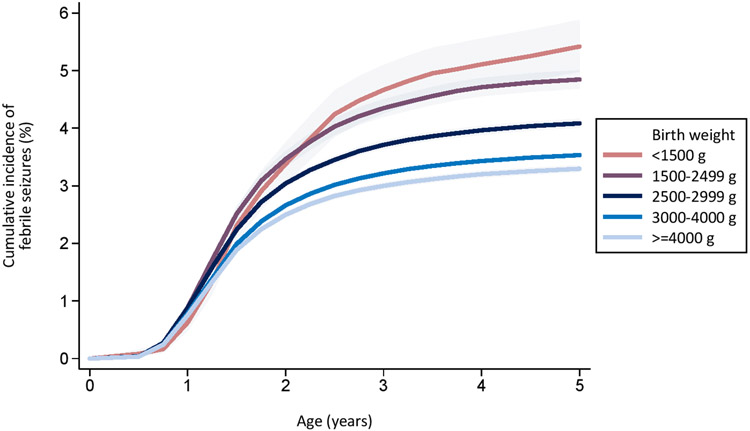

The cumulative incidence of a first febrile seizure increased with decreasing birth weight (Figure 1a). At the age of 5 years, the cumulative incidence of a first febrile seizure was <1,500 g: 5.42% (95% CI: 4.98-5.88); 1,500-2,499 g: 4.85% (95% CI: 4.69-5.01); 2,500-2,999 g: 4.08% (95% CI: 4.01-4.16); 3,000-4,000 g: 3.53% (95% CI: 3.50-3.56); and > 4,000 g: 3.30% (95% CI: 3.24-3.36).

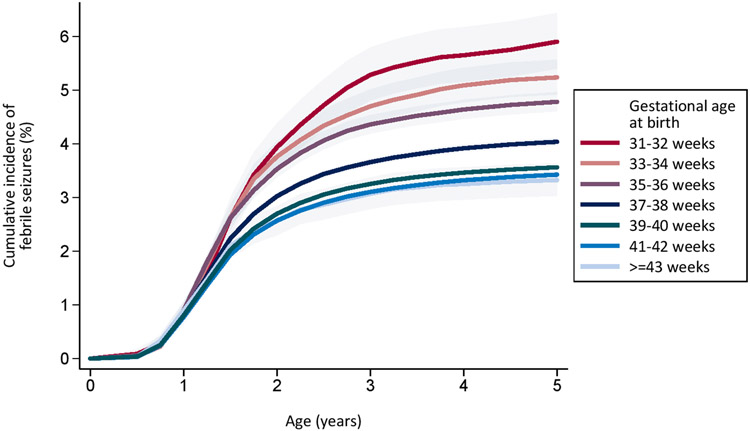

Figure 1:

Cumulative incidence of first febrile seizure by birth weight (Figure 1a) and by gestational age at birth (Figure 1b) in 2,103,288 children born in Denmark in 1977-2011 with follow up to 31 December 2016.

Similarly, the cumulative incidence of first febrile seizure increased with decreasing gestational age at birth (Figure 1b). The cumulative incidence was 31-32 weeks: 5.90% (95% CI: 5.40-6.44); 33-34 weeks: 5.24% (95% CI: 4.92-5.57); 35-36 weeks: 4.78% (95% CI: 4.61-4.96), 37-38 weeks: 4.04% (95% CI: 3.97-4.11); 39-40 weeks: 3.56% (95% CI: 3.53-3.60); 41-42 weeks: 3.43% (95% CI: 3.38-3.48); 43-44 weeks: 3.33% (95% CI: 3.03-3.64)

The cumulative incidence of febrile seizures at five years of age was higher in children born small for gestational age (4.11% (95% CI: 4.03-4.20)) compared to children born normal for gestational age (3.56% (3.53-3.58)). However, the risk of febrile seizures increased by decreasing birth weight and decreasing gestational age at birth, both for children born small for gestational age and for children born normal for gestational age (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cumulative incidence of febrile seizures by birth weight and gestational age at birth stratified on whether or not children were born normal for gestational age.

| Children born normal for gestational age N = 1,764,001 |

Children born small for gestational age N = 199,591 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Birth characteristics | Cumulative incidence of febrile seizures at age 5 years % (95% CI) |

Cumulative incidence of febrile seizures at age 5 years % (95% CI) |

| Overall | 3.56 (3.53-3.58) | 4.11 (4.03-4.20) |

| Birth weight | ||

| <1500 g | 5.25 (4.75-5.78) | 5.92 (5.04-6.90) |

| 1500-2499 g | 5.01 (4.79-5.24) | 4.67 (4.45-4.90) |

| 2500-2999 g | 4.12 (4.01-4.24) | 4.04 (3.94-4.16) |

| 3000-3999 g | 3.53 (3.50-3.56) | 3.73 (3.55-3.93) |

| ≥ 4000 g | 3.30 (3.24-3.36) | - |

| Gestational age at birth | ||

| 31-32 weeks | 6.01 (5.48-6.58) | 4.93 (3.58-6.60) |

| 33-34 weeks | 5.16 (4.83-5.51) | 5.92 (4.90-7.06) |

| 35-36 weeks | 4.69 (4.51-4.88) | 5.59 (5.00-6.22) |

| 37-38 weeks | 3.98 (3.91-4.06) | 4.52 (4.29-4.76) |

| 39-40 weeks | 3.51 (3.47-3.55) | 4.02 (3.90-4.14) |

| 41-42 weeks | 3.38 (3.33-3.43) | 3.86 (3.70-4.03) |

| ≥ 43 weeks | 3.32 (3.01-3.65) | 3.37 (2.50-4.44) |

In the sensitivity analysis of febrile seizures stratified on birth year, the cumulative incidence of febrile seizures at five years of age increased during the study period from 3.10% (95% CI: 3.063.14) for children born in from 1977 to 1990 to 3.93% (95% CI: 3.89-3.96)) for children born from 1995 to 2011. The difference between the two time periods was (0.83% (95% CI: 0.78-0.88) (P < 0.001)). The association between gestational age at birth and birth weight and risk of febrile seizures was similar in the two time periods (Data not shown).

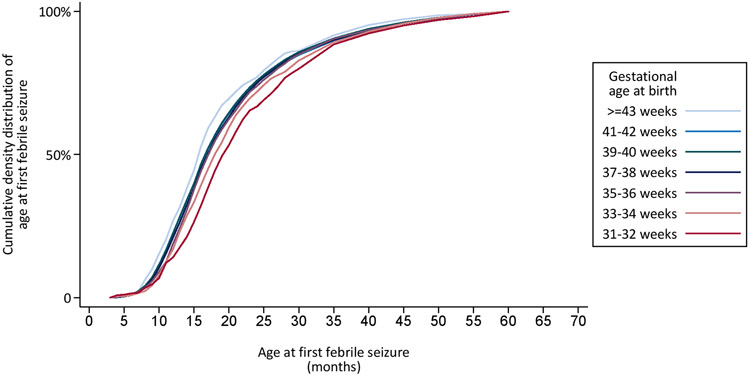

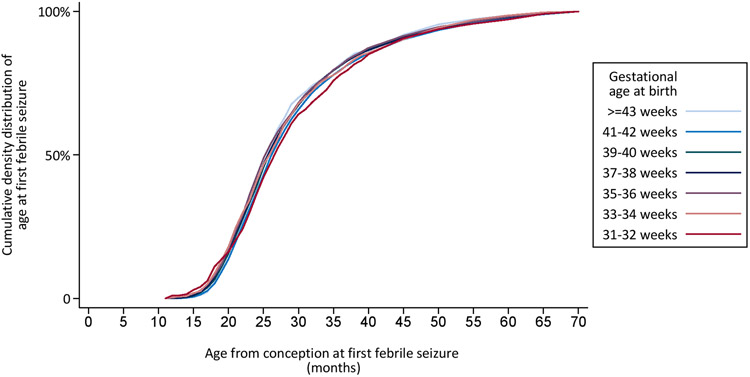

The cumulative distribution of age at first febrile seizure by gestational age at birth is shown in Figure 2a. The figure illustrates that lower gestational age at birth is associated with later age at onset of a first febrile seizure, which is also reflected by the median age at first febrile seizures by gestational age at birth (Table 2). This association essentially disappears when considering age from conception rather than age from birth (Figure 2b). Thus, this suggests that the variation in the cumulative age distributions of onset of febrile seizures by gestational age approximately corresponds to the variation in gestational age itself. The cumulative distribution of age of first febrile seizures also disappeared when considering age from conception both for children born normal for gestational age and for children born small for gestational age (Data not shown).

Figure 2:

Cumulative distribution of age at first febrile seizure, by gestational age at birth in 71,551 children born in Denmark in 1978-2011. Cumulative distribution of age from birth at first febrile seizure by gestational age at birth (Figure 2a). Cumulative distribution of age from conception at first febrile seizure by gestational age at birth (Figure 2b).

Table 2.

Gestational age at birth and median age at first febrile seizure in 71,551 children born in Denmark in 1978-2011.

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) |

Median age (months) at first febrile seizure (interquartile range) |

|---|---|

| 31-32 weeks | 19.1 months (14.9-27.3) |

| 33-34 weeks | 17.8 months (13.3-25.2) |

| 35-36 weeks | 17.0 months (13.1-24.5) |

| 37-38 weeks | 16.9 months (12.7-24.0) |

| 39-40 weeks | 16.6 months (12.4-23.6) |

| 41-42 weeks | 16.6 months (12.4-24.0) |

| 43-44 weeks | 15.6 months (11.6-22.6) |

DISCUSSION

The findings of this cohort study of more than 2 million children suggests that the risk of and time of onset of a first febrile seizure depends on various endogenous factors. We found that the risk of febrile seizures was substantially higher in children born prematurely and with a low birth weight compared to children born at term and with a normal birth weight. The increased risk associated with low birth weight and low gestational age at birth was identified both in children who were born normal for gestational age and in children who were born small for gestational age. The age-specific risk of being admitted with a first febrile seizure peaked at 16 months of age, but to our surprise, we observed that being born earlier (i.e. with a low gestational age birth) correlated with a later age at onset of febrile seizures. This difference in age at onset disappeared when we considered age from conception, and was observed both for children born normal for gestational age and for children born small for gestational age, indicating that the age-specific risk of febrile seizures may depend on the stage of brain development.9,10 Thus, our study indicates that for both pre- and post-term children, the peak age of the first febrile seizure will occur at the same corrected age as in children born at term.

The developing human brain has unique properties with regards to neuronal activity during early childhood. Major changes take place, including in the GABA-ergic system, which changes from being predominantly excitatory to becoming inhibitory, and synaptic networks are being established.9,29 This study found, that the risk of febrile seizure was highest around 16 months of age, corresponding to the timing of important neuronal network changes.9,10 In addition, we found that the age of onset of the first febrile seizures was higher when the gestational age was low, and that this effect disappeared when using corrected age – further suggesting that the risk of febrile seizures correlates with the stage brain development.

Due to the nature of the present data, we are unable to determine whether children with a febrile seizure generally have more febrile episodes than children who do not have febrile seizures. However, a previous study found that variants at genetic loci harbouring innate immune response genes were associated with febrile seizures occurring after vaccination against measles, mumps and rubella (MMR).30 Future genetic studies may elucidate the relative contribution of pathways related to fever/immune response versus pathways related to ion channel function and neuronal excitability.

Children born preterm and with low birth weight was found to have an overall higher risk of febrile seizures (Figure 1a and 1b), perhaps because of their higher susceptibility to infections and fever episodes.31,32 However, if a fever episode was the only determinant of febrile seizures, we would expect the peak incidence among children born preterm to occur early in life, i.e. at an age comparable to that of children born at term – in fact, we observed the opposite – preterm infants had later onset of first febrile seizure than term children.

This study has a number of obvious strengths as well a number of limitations. The statistical power of register-based cohort studies is strong, especially when a large cohort such as the entire population of live-born children in Denmark over a period of 35 years is used.16 Although the cumulative incidence increased in the study period, there was no time trend in the association between gestational age of birth, birth weight and the risk of febrile seizures at five years of age. In addition, for the diagnosis of febrile seizures, the Danish Hospital Register has high data quality.1,16 A validation study found a positive predictive value of a febrile seizure diagnosis in the Danish Hospital Register of 92.8% (95% CI: 88.8-95.7).1 This study also assessed the completeness of the febrile seizure diagnosis in the Danish Hospital Register to estimate how many children are admitted to hospital for a febrile seizure. In a cohort of 6,624 pregnancies, febrile seizures were verified by telephone interviews or review of medical records and linked with the Danish Hospital Register. Authors found that 323 (4.9%) children in the cohort had had febrile seizures, and 231 of those were registered in the Danish Hospital Register (completeness: 71.5%, 95% CI: 66.3–76.4). The current study identified 3.59% of children with febrile seizures in the Danish Hospital Register, and we may therefore not capture all children with febrile seizures.

Significant limitations to this register-based study are the lack of detailed clinical data and information on use of medication. The register contains no information on the severity of febrile seizures (duration, recurrence within 24 hours or type of seizure (focal or generalized)), and we were thus unable to divide the febrile seizures into simple or complex febrile seizures.33 Therefore, the present findings might not apply to all subgroups of children with febrile seizures in the cohort.

The study was based on data from the Danish registers, and genetic and environmental differences (e.g. climate, load and seasonality of infectious diseases, public health care) may exist between populations. Studies from Asian countries have found a substantially higher risk of febrile seizures;34 e.g., a register study from Korea found that 6.92% of all children were admitted with febrile seizures, which is almost twice as many as reported by our study. With regards to sex difference and peak risk of febrile seizures, the same Korean study found higher risk in boys than in girls (7.67% for boys and 6.12% for girls) - a sex difference also seen in our study. However, the Korean study described that the first episode of febrile seizures occurred between 18 and 30 months, which is later than found in the present study.16

Conclusion

The causes of febrile seizures are multifactorial and likely involve interactions between several factors including individual and familial susceptibility, birth characteristics, stage of brain development and exogenous factors such as infections. Although most of the febrile seizures are self-limiting and associated with favourable prognosis, the interaction between genetic predisposition and perinatal conditions will represent important future targets for research into potential consequences for long-term development including the risk of epilepsy and psychiatric disorders after febrile seizures.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (1R01NS106104-01A1), the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF16OC0019126), Central Denmark Region, and the Danish Epilepsy Association. Bjarke Feenstra received funding from a Lundbeck Foundation Ascending Investigator grant (R313-2019-554).

Footnotes

Competing interests

Jakob Christensen received honoraria from serving on the scientific advisory board of UCB Nordic and Eisai AB, received honoraria from giving lectures from UCB Nordic and Eisai AB, and received funding for a trip from UCB Nordic. The other authors report no conflicts of interests.

Data sharing

Anonymized summary data on the patient cohort that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Vestergaard M, Obel C, Henriksen TB, et al. The Danish National Hospital Register is a valuable study base for epidemiologic research in febrile seizures. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(1):61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forsgren L, Sidenvall R, Blomquist HK, Heijbel J. A prospective incidence study of febrile convulsions. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1990;79(5):550–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hauser WA. The prevalence and incidence of convulsive disorders in children. Epilepsia. 1994;35 Suppl 2:S1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung AK, Hon KL, Leung TN. Febrile seizures: an overview. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212536–212536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guidelines for Epidemiologic Studies on Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1993;34(4):592–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mewasingh LD. Febrile seizures. BMJ clinical evidence. 2014;2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vestergaard M, Pedersen CB, Sidenius P, Olsen J, Christensen J. The long-term risk of epilepsy after febrile seizures in susceptible subgroups. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(8):911–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dreier JW, Pedersen CB, Cotsapas C, Christensen J. Childhood seizures and risk of psychiatric disorders in adolescence and early adulthood: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3(2):99–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rakhade SN, Jensen FE. Epileptogenesis in the immature brain: emerging mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(7):380–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverstein FS, Jensen FE. Neonatal seizures. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(2):112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobbing J, Sands J. Quantitative growth and development of human brain. Archives of disease in childhood. 1973;48(10):757–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hjeresen DL, Diaz J. Ontogeny of susceptibility to experimental febrile seizures in rats. Developmental Psychobiology. 1988;21(3):261–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen FE, Baram TZ. Developmental seizures induced by common early-life insults: short- and long-term effects on seizure susceptibility. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2000;6(4):253–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bender RA, Baram TZ. Epileptogenesis in the developing brain: what can we learn from animal models? Epilepsia. 2007;48 Suppl 5(Suppl 5):2–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vestergaard M, Basso O, Henriksen TB, Ostergaard JR, Olsen J. Risk factors for febrile convulsions. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass). 2002;13(3):282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vestergaard M, Christensen J. Register-based studies on febrile seizures in Denmark. Brain Dev. 2009;31(5):372–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harder KM, Molbak K, Glismann S, Christiansen AH. Influenza-associated illness is an important contributor to febrile convulsions in Danish children. J Infect. 2012;64(5):520–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharawat IK, Singh J, Dawman L, Singh A. Evaluation of Risk Factors Associated with First Episode Febrile Seizure. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(5):SC10–SC13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikkonen K, Uhari M, Pokka T, Rantala H. Diurnal and seasonal occurrence of febrile seizures. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;52(4):424–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertelsen EN, Larsen JT, Petersen L, Christensen J, Dalsgaard S. Childhood Epilepsy, Febrile Seizures, and Subsequent Risk of ADHD. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillberg C, Lundstrom S, Fernell E, Nilsson G, Neville B. Febrile Seizures and Epilepsy: Association With Autism and Other Neurodevelopmental Disorders in the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;74:80–86.e82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedersen CB, Gotzsche H, Moller JO, Mortensen PB. The Danish Civil Registration System. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull. 2006;53(4):441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Consensus statement. Febrile seizures: long-term management of children with fever-associated seizures. Pediatrics. 1980;66(6):1009–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christensen J, Vestergaard M, Pedersen MG, Pedersen CB, Olsen J, Sidenius P. Incidence and prevalence of epilepsy in Denmark. Epilepsy Res. 2007;76(1):60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bliddal M, Broe A, Pottegard A, Olsen J, Langhoff-Roos J. The Danish Medical Birth Register. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33(1):27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CVaB M. Cumulative incidence estimation in the presence of competing risks. Stata J. 2004;4(2):103. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marubini EVM. Analysing Survival Data from Clinical Trials and Observational Studies. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nardou R, Ferrari DC, Ben-Ari Y. Mechanisms and effects of seizures in the immature brain. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;18(4):175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feenstra B, Pasternak B, Geller F, et al. Common variants associated with general and MMR vaccine-related febrile seizures. Nature genetics. 2014;46(12):1274–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Townsi N, Laing IA, Hall GL, Simpson SJ. The impact of respiratory viruses on lung health after preterm birth. Eur Clin Respir J. 2018;5(1):1487214–1487214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. Trends in Care Practices, Morbidity, and Mortality of Extremely Preterm Neonates, 1993-2012. Jama. 2015;314(10):1039–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH. Predictors of epilepsy in children who have experienced febrile seizures. The New England journal of medicine. 1976;295(19):1029–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Byeon JH, Kim GH, Eun BL. Prevalence, Incidence, and Recurrence of Febrile Seizures in Korean Children Based on National Registry Data. J Clin Neurol. 2018;14(1):43–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]