Abstract

The objective of this study was to analyse the mechanisms of resistance to carbapenems and other extended-spectrum-β-lactams and to determine the genetic relatedness of multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales (MDR-E) causing colonization or infection in solid-organ transplantation (SOT) recipients. Prospective cohort study in kidney (n = 142), liver (n = 98) or kidney/pancreas (n = 7) transplant recipients between 2014 and 2018 in seven Spanish hospitals. We included 531 MDR-E isolates from rectal swabs obtained before transplantation and weekly for 4–6 weeks after the procedure and 10 MDR-E from clinical samples related to an infection. Overall, 46.2% Escherichia coli, 35.3% Klebsiella pneumoniae, 6.5% Enterobacter cloacae, 6.3% Citrobacter freundii and 5.7% other species were isolated. The number of patients with MDR-E colonization post-transplantation (176; 71.3%) was 2.5-fold the number of patients colonized pre-transplantation (71; 28.7%). Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases were detected in 78.0% and 21.1% of MDR-E isolates respectively. In nine of the 247 (3.6%) transplant patients, the microorganism causing an infection was the same strain previously cultured from surveillance rectal swabs. In our study we have observed a low rate of MDR-E infection in colonized patients 4–6 weeks post-transplantation. E. coli producing blaCTX-M-G1 and K. pneumoniae harbouring blaOXA-48 alone or with blaCTX-M-G1 were the most prevalent MDR-E colonization strains in SOT recipients.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Antimicrobials, Clinical microbiology

Introduction

The prevalence of multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales (MDR-E) as a cause of infection in solid-organ transplant (SOT) patients is progressively increasing, mainly during the first month post-procedure. These infections represent an important cause of morbidity and mortality1,2. Studies examining the outcome of infection caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacterales among SOT recipients report mortality rates ranging from 5 to 20%3. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales infections are associated with high mortality among SOT recipients4.

Most MDR-E are organisms producing ESBLs, carbapenemases or AmpC enzymes (by either plasmid-borne genes or derepressed or hyperexpressed chromosomal genes). Among the numerous ESBLs, CTX-M, TEM and SHV are the most commonly detected5. OXA-48-like enzymes along with VIM and KPC are the three most common carbapenemase genes identified in Spain6.

Pre-transplant colonization by MDR-E has been described as an important risk factor for infection after SOT7. Several studies recommend the screening of patients at high risk for MDR-E colonization, including SOT recipients8,9. According to these data, it seems advisable to obtain rectal swabs from SOT recipients at the time of transplantation to assess intestinal colonization by MDR-E. Subsequently, surveillance cultures may be recommended depending on the local epidemiological pattern and individual risk factors1.

The objective of this study was to characterize the mechanisms of resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins and carbapenems and to determine the genetic relatedness of MDR-E involved in both colonization and infection in SOT recipients.

Results

Study population and bacterial strains

A total of 541 MDR-E isolates were obtained from 247 patients with kidney (n = 142), liver (n = 98) or both kidney and pancreatic transplants (n = 7). Of these, 531 were isolated from rectal samples (460 isolates were obtained post-transplantation; 71, pre-transplantation) and 10 were isolated from clinical samples (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of 541 multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales recovered from rectal swabs according to the pre and post-transplantation period and from clinical samples.

| Rectal swabs (n = 531) | Infection (n = 10) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-transplant (n = 71) | Post-transplant (n = 460) | |||

| E. coli (250) | 46 (64.8%) | 202 (43.9%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0.059 |

| K. pneumoniae (191) | 12 (16.9%)* | 174 (37.8%)* | 5 (50.0%) | 0.011 |

| E. cloacae (35) | 5 (7.0%) | 28 (6,1%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0.771 |

| C. freundii (34) | 5 (7.0%) | 29 (6.3%) | 0 | 0.825 |

| Other (31) | 3 (4.3%) | 27 (5.9%) | 1 (10.0%) | 0.595 |

*Statistically significant differences (bold type) were found between pre- and post-transplant rectal swabs.

Other species included: 9 Morganella morganii, 7 Klebsiella oxytoca, 6 Proteus mirabilis, 5 Enterobacter aerogenes, 2 Citrobacter braakii, 1 Enterobacter asburiae and 1 Citrobacter koseri.

The microorganisms recovered were the following: E. coli (46.2%, n = 250), K. pneumoniae.

(35.3%, n = 191), E. cloacae (6.5% n = 35), C. freundii (6.3%, n = 34) and other species (5.7%, n = 31, corresponding to 9 Morganella morganii, 7 Klebsiella oxytoca, 6 Proteus mirabilis, 5 Enterobacter aerogenes, 2 Citrobacter braakii, 1 Enterobacter asburiae and 1 Citrobacter koseri).

Table 2 shows the distribution of 541 MDR-E isolates recovered from patients according to transplant type. Overall, the isolation rates of E. coli and E. cloacae in kidney recipients were significantly higher than those of liver recipients (143/250, 57.2% vs 104/250, 41.6%, P = 0.042 and 22/35, 62.9% vs 9/35, 25.7%, P = 0.050 respectively). K. pneumoniae was significantly more prevalent in rectal swabs collected post-transplantation (174/460, 37.8%) compared with pre-transplantation (12/71, 16.9%) (P = 0.011). No significant differences were found in the prevalence of the other bacterial species between pre- or post-transplantation rectal swabs (Table 1).

Table 2.

Distribution of 541 multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales recovered from 247 patients according to transplant type.

| Transplant type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney (n = 142) | Liver (n = 98) | Kidney /pancreas (n = 7) | P-value | |

| E. coli (250) | 143 (57.2%)* | 104 (41.6%)* | 3 (1.2%) | 0.042 |

| K. pneumoniae (191) | 83 (43.5%) | 99 (51.8%) | 9 (4.7%) | 0.328 |

| E. cloacae (35) | 22 (62.9%)* | 9 (25.7%)* | 4 (11.4%) | 0.050 |

| C. freundii (34) | 18 (53.0%) | 15 (44.1%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0.668 |

| Other (31) | 16 (51.6%) | 15 (48.4%) | 0 | 0.883 |

| Total | 282 | 242 | 17 | |

*Statistically significant differences (bold type) were found in the prevalence of bacterial species between kidney and liver transplant.

Other species included: 9 Morganella morganii, 7 Klebsiella oxytoca, 6 Proteus mirabilis, 5 Enterobacter aerogenes, 2 Citrobacter braakii, 1 Enterobacter asburiae and 1 Citrobacter koseri.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The activities of the 24 antibiotics against the species most frequently isolated (i.e., E. coli, K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae and C. freundii) among the 345 MDR-E isolates (one isolate per REP-PCR pattern/preliminary antibiogram and patient) are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Overall, the resistance rates of the selected MDR-E were 100% to amoxicillin, 98.6% to piperacillin and between 48.4% and 96.8% to cephalosporins. MIC90 values of penicillins, penicillin-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, cephalosporins and aztreonam were > 256 mg/L. The following resistance rates to carbapenems were observed: 4.1% to meropenem, 7.2% to imipenem and 25.8% to ertapenem. Percentages of resistance to aminoglycosides were greater than 37.7% with the exception of amikacin (2.9% resistance rate). Colistin showed the lowest MIC90 (1 mg/L). K. pneumoniae (70.2%) exhibited increased resistance to fosfomycin compared with E. coli (9.2%) or other species.

K. pneumoniae exhibited increased rates of resistance compared with other organisms, with more than half of the isolates showing resistance to all the antibiotics tested except imipenem (4.1%), amikacin (4.1%), meropenem (8.3%) and colistin (10.7%).

Genes encoding ESBLs, AmpC and carbapenemases

The distribution of isolates with genes encoding ESBLs, plasmid-mediated AmpC or carbapenemases or hyperproducing AmpC among 345 MDR-E isolates is shown in Table 3. In all, 269 strains (78.0%) harboured ESBLs genes, CTX-M-group-1 being the most prevalent (53.3%) followed by CTX-M-group-9 in 15.4% of isolates. Detailed information on the exact ESBLs identified is presented in Table 4. Carbapenemases were detected in 73 MDR-E isolates (21.1%). Here, blaOXA-48 was the most frequently identified gene (16.5% of the strains), noted mainly in K. pneumoniae, followed by VIM-1 (3.8%) and KPC-2 (0.9%). No other carbapenemase genes were detected. Among ESBL-producers, 2.1% (n = 3) E. coli, 47.3% (n = 52) K. pneumoniae and 11.1% (n = 1) E. cloacae harboured a carbapenemase gene. In 93.0% (53/57) of the isolates producing OXA-48 (51 K. pneumoniae and 2 E. coli), CTX-M-15 was also detected. One E. coli harboured VIM-1 plus CTX-M-14, and one K. pneumoniae isolate produced both KPC-2 and CTX-M-15 (Supplementary Information files).

Table 3.

Distribution of antibiotic resistance genes encoding ESBLs, AmpC and carbapenemases detected in 345 MDR-E isolates from patients with kidney, liver or combined kidney/pancreas transplant.

| Species (n) | bla CTX-M (238) | TEM (4) | SHV (27) | AmpC-producing (47) | Carbapenemases (73) | Othera (12) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M G1 (184) | CTX-M G9 (53) | CTX-M G8 (1) | Plasmid | Chromosomal hyperproduction | OXA-48 (57) | VIM-1 (13) | KPC-2 (3) | ||||

| E. coli (152) | 75 (49.3%) | 40 (26.3%) | 1 (0.6%) | 3 (2.0%) | 22 (14.3%) | 4 (2.6%) | 3 (2.0%) | 2 (1.3%) | – | 5 (3.3%) | |

| K. pneumoniae (121) | 101 (83.5%) | 4 (3.3%) | – | 1 (0.8%) | 4 (3.3%) | – | 53 (43.8%) | 4 (3.3%) | 3 (2.5%) | 3 (2.5%) | |

| E. cloacae (26) | 2 (7.7%) | 6 (23.1%) | – | – | 1 (3.8%) | 15 (57.7%) | 1 (3.8%) | 2 (7.7%) | – | – | |

| C. freundii (23) | 1 (4.3%) | 2 (8.7%) | – | – | – | 19 (82.6%) | – | 1 (4.3%) | – | – | |

| Othersb (23) | 5 (21.7%) | 1 (4.3%) | – | – | – | 9 (39.1%) | – | 4 (17.4%) | – | 4 (17.4%) | |

aOther mechanisms were: SHV-1 hyperproduction (4 strains), TEM-1 hyperproduction (4 isolates) and OXA-1 production (4 strains).

bOther species included: 7 K. oxytoca, 6 M. morganii, 4 E. aerogenes, 2 P. mirabilis, 2 C. braakii, 1 E. asburiae and 1 C. koseri.

Table 4.

ESBL genes identified in MDR-E isolated from patients with kidney, liver or combined kidney/pancreas transplant.

| ESBLs detected | E. coli (141) | K. pneumoniae (110) | E. cloacae (9) | C. freundii (3) | Other species (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHV-2 | 2 | ||||

| SHV-12 | 22 | 2 | 1 | ||

| TEM-19 | 2 | ||||

| TEM-52 | 1 | ||||

| TEM-169 | 1 | ||||

| CTXM-1 | 6 | ||||

| CTXM-3 | 1 | ||||

| CTXM-8 | 1 | ||||

| CTXM-9 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 1 | |

| CTXM-14 | 22 | 3 | 1 | ||

| CTXM-15 | 44 | 97 | 1 | 3 | |

| CTXM-27 | 10 | ||||

| CTXM-28 | 1 | ||||

| CTXM-32 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| CTXM-55 | 6 | ||||

| CTXM-65 | 1 | 1 | |||

| CTXM-138 | 4 | 2 | |||

| CTXM-156 | 1 | ||||

| CTXM-182 | 1 |

Plasmid-mediated AmpC production was observed in four E. coli isolates (2.6%) (3 CIT and one DHA producers), while the hyperproduction of chromosomal-AmpC was detected in E. cloacae (57.7%), C. freundii (82.6%) and other MDR-E species (39.1%).

Other mechanisms of resistance to ESBLs could be inferred by interpretative reading of antibiograms, and included SHV-1 hyperproduction (3 K. pneumoniae and 1 E. coli), TEM-1 hyperproduction (2 E. coli and 2 K. oxytoca), and OXA-1 production (2 E. coli and 2 K. oxytoca).

Molecular epidemiology

PFGE was performed in 287 isolates: E. coli (n = 141), K. pneumoniae (n = 100), E. cloacae (n = 24) and C. freundii (n = 22).

E. coli isolates recovered from different hospitals and patients exhibit high genetic diversity (Supplementary Fig. 1). A total of 127 isolates were grouped into 113 pulsotypes, 14 of which were non-typeable.

The molecular typing of K. pneumoniae (n = 100) revealed 57 different PFGE-patterns, showing a heterogeneous picture (Supplementary Fig. 2). One strain was non-typeable. There were 44 pulsotypes with a single isolate and 13 clusters with two or more isolates. In general, K. pneumoniae strains exhibited greater similarity in PFGE-patterns compared with E. coli isolates with rates of 1.737 and 1.124, respectively. The predominant clone (#22) included 29 isolates belonging to patients from the same hospital and harboured both CTX-M-15 and OXA-48.

The dendrograms obtained in E. cloacae and C. freundii demonstrated 21 pulsotypes in both species (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), revealing high clonal heterogeneity.

Association between faecal carriage and infection

The number of patients colonized with MDR-E during the first month post-transplantation (176; 71.3%) was 2.5-fold the number of colonized pre-transplantation patients (71; 28.7%). In both cases, CTX-M-producing E. coli was the most prevalent MDR-E isolate.

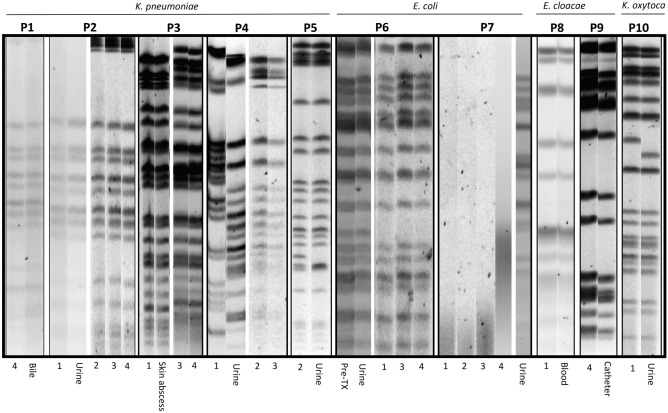

Ten out of 247 (4.0%) patients colonized by MDR-E developed infections during the post-transplantation follow-up. Isolates from rectal swabs pre- and post-transplant and infections were compared using PFGE and MLST. Table 5 shows the characteristics of these patients and the corresponding organisms. The PFGE patterns are shown in Fig. 1. In 9 of these 10 pairs of MDR-E, the colonization and the infection isolates exhibited identical PFGE-typing and STs.

Table 5.

Characteristics of the MDR-E isolated by rectal swab and clinical samples from eight kidney and two liver transplant recipients.

| Patients | Transplant | Species | Clinical sample | Positive rectal samples (weeks) | Antibiotic resistance profile | Mechanisms of resistance | ST | Hospitals | PFGE-pattern relationship between MDR-E isolated in rectal swab and clinical sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | LT | K. pneumoniae | Bile | 4* | AMX, PIP, AMC, TZP, FOX, CTX, CAZ, FEP, AZT, ETP, IMP, MRP, NAL, CIP, LEV, TO, NET, FOS, TIG | CTX-M-15 + OXA-48 | 11 | H1 | Same |

| 02 | KT | K. pneumoniae | Urine | 1*,2,3,4 | AMX, PIP, AMC, TZP, FOX, CTX, CAZ, FEP, AZT, ETP, NAL, CIP, LEV, GN, TO, NET, FOS, SXT, TIG. (urine isolate susceptible to GN, TO, NET,) | CTX-M-15 + OXA-48 | 11 | H1 | Same |

| 03 | KT | K. pneumoniae | Skin abscess | 1*,3,4 | AMX, PIP, AMC, TZP, CTX, CAZ, FEP, AZT, CIP, GN, TO, NET, SXT, TIG | CTX-M-15 | 429 | H2 | Same |

| 04 | LT | K. pneumoniae | Urine | 1*,2*,3 | AMX, PIP, AMC, TZP, FOX, CTX, CAZ, FEP, AZT, ETP, IMP, MRP, NAL, CIP, LEV, AMK, TO, NET, FOS, TIG, COL | KPC-2 | 512 | H6 | Same except RS-1 |

| 05 | KT | K. pneumoniae | Urine | 2* | AMX, PIP, AMC, TZP, CTX, CAZ, FEP, AZT, NAL, CIP, LEV, GN, TO, NET, SXT, TIG, | CTX-M-15 | 307 | H6 | Same |

| 06 | KT | E. coli | Urine | Pre-TX*,1,3,4 | AMX, PIP, AMC, CTX, CAZ, FEP, AZT, NAL, CIP, LEV, TO NET. (urine isolate susceptible to CAZ and FEP) | CTX-M-15 | 43 | H1 | Same |

| 07 | KT | E. coli | Urine | 1*,2,3,4 | AMX, PIP, AMC, TZP, CTX, CAZ, FEP, AZT, NAL, CIP, LEV, TO, NET. (strain from RS-1 susceptible to AMC, TO, NET) | CTX-M-15 (urine), CTX-M-32 (RS-1) | 621 (urine) and 83 (RS1) | H6 | Different |

| 08 | KT | E. cloacae | Blood | 1* | AMX, PIP, AMC, TZP, FOX, CTX, NAL, FOS, TIG | CTX-M-9 | 97 | H1 | Same |

| 09 | KT | E. cloacae | Catheter | 4* | AMX, PIP, AMC, FOX, CTX, NAL, FOS | Hyper AmpC | 781 | H6 | Same |

| 10 | KT | K. oxytoca | Urine | 1* | AMX, PIP, AMC, TZP, AZT | Hyper TEM-1 | 213 | H6 | Same |

KT kidney transplant, LT liver transplant, ST sequence type, AMC amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, AMK amikacin, AMX amoxicillin, AZT aztreonam, CAZ ceftazidime, CIP ciprofloxacin, COL colistin, CTX cefotaxime, ERT ertapenem, FEP cefepime, FOS fosfomycin, FOX cefoxitin, GN gentamicin, IMP imipenem, LEV levofloxacin, MRP meropenem, NAL nalidixic acid, NET netilmicin, PIP piperacillin, RS rectal sample, ST sequence type, SXT trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, TIG tigecycline, TO tobramycin, TZP piperacillin-tazobactam, H1 Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, H2 Hospital Clinic, H6 Hospital Reina Sofia.

*Isolates from the RS that were selected to compare with infection isolate using MLST.

Figure 1.

PFGE patterns of MDR-E from rectal swabs obtained pre-transplant (pre-TX) or post-transplant (number indicates weeks for rectal swabs) and from infection-related strains in 10 transplant recipients (P1 to P10 corresponding to Table 5). The PFGE profiles were obtained from different agarose gels and grouped in this figure. (P7: isolates 1, 2, 3 and 4 were non-typeable with XbaI).

In patient 07, the MDR-E obtained in rectal swabs at 1, 2, 3 and 4 weeks post-TX were non-typeable with XbaI. However, the isolate causing urinary infection obtained in the sample presented a clear PFGE pattern, so they were considered not clonally related (Fig. 1). These isolates presented the same ESBL but with different allelic variants (CTX-M-15 and -32).

Discussion

In this study, the microbiological characteristics of MDR-E isolated from rectal swabs and clinical isolates in SOT patients were analysed. We found high heterogeneity among MDR-E colonizing isolates using a combination of active pre- and post-transplantation surveillance and molecular epidemiology studies.

E. coli and K. pneumoniae represented the majority of MDR-E colonizing strains in our patients, a finding which is consistent with previous studies performed among SOT recipients4,10.

ESBLs were identified in 78.0% of MDR-E, and CTX-M-15 was the most prevalent enzyme. These results are similar to those found in multiple reports worldwide5,11. In Spain approximately 20% of infections in SOT recipients are caused by MDR-E, from which 75% are due to ESBL-producing Enterobacterales12.

Carbapenemases were detected in 21.1% of MDR-E isolates, and OXA-48 was the most common enzyme followed by VIM-1 and KPC-2. Data from the EuSCAPE project in Spain also showed a predominance of OXA-48 and a low prevalence of KPC, VIM or NDM enzymes13.

Carbapenems have been traditionally considered the drugs of choice for the treatment of infections caused by ESBL or AmpC-producing enterobacteria; however, their use has contributed to the significant worldwide spread of carbapenem resistance. It is therefore important to consider alternative drugs, such as ceftazidime-avibactam (active against most KPC- and OXA-48-producing Enterobacterales), meropenem-vaborbactam and imipenem-relebactam, which have activity against KPC and ESBL-producers14. However, MDR-E isolated in our study show a low resistance rate to meropenem (4.1%) and imipenem (7.2%), in contrast to ertapenem (25.8%) for which resistance rates in K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae were 52.9% and 38.5%, respectively.

Surveillance cultures for detection of colonized patients with MDR-E and implementation of contact precautions, among other measures, have allowed a reduction of the infection rate, both in outbreak and in endemic settings9,15.

Post-transplantation complications in SOT patients were associated with both MDR-E colonization and infection, suggesting that in-hospital acquisition of MDR-E in the early post-transplantation period plays an important role16,17. In this respect, MDR-E colonization after SOT transplantation has been associated with a subsequent infection at a 1:7 ratio of infected: colonized patients for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales and 1:4 for organisms resistant to third-generation cephalosporins17. In this study, we observed a low rate of infection with MDR-E (4.0%) in colonized patients during follow-up in the first six weeks post-transplantation. In an Italian cohort study, infections caused by KPC-producing K. pneumoniae were diagnosed in 29.2% of the liver transplant recipients who were colonized7. Other studies have also described higher infection rates (17%-48%) in colonized liver transplant patients9,16,18.

Molecular typing of our isolates (PFGE and MLST) revealed significant genetic diversity. Bert et al. also found high clonal diversity between ESBL-producing Enterobacterales obtained from colonization and infection after liver transplantation18. These findings indicate that MDR-E infections in our patients were not related to the hospital spread of specific clones. The high-risk ST-11 K. pneumoniae strain has been frequently detected worldwide as a successful virulent pathogen with determinants for resistance, including VIM, OXA-4819 and KPC-production20. In our study, all ST11 strains carried CTXM-15 and OXA-48. In recent years, new international drug-resistant lineages have emerged. Among these, K. pneumoniae ST307 and KPC-producing K. pneumoniae ST512 have been recognized in several countries including Spain20,21. ST307 was strongly associated with the diffusion of CTX-M-15, and in France, it has recently been defined as a new successful high-risk clone associated with the dissemination of KPC genes22. Both clones were detected as a cause of urinary infection in two patients in our study.

Some study limitations should be considered when extrapolating our results. First, we only collected rectal swabs, which may be inadequate for detecting resistant pathogens present in small amounts. Nevertheless, there is evidence that rectal swabs are more sensitive than other anatomical sites for detecting MDR-E. Secondly, we performed molecular characterization of 541 MDR-E corresponding to 80.2% of colonized patients pre or post-transplantation. Some hospitals did not send all MDR-E isolated from patients enrolled in the study to the coordinating center. And finally, this is a study restricted to a single country, a fact that may limit the extrapolation of its results to other territories. However, it is a prospective study conducted in seven University hospitals in southern Europe where a pioneering transplant program is implemented, and our results may be useful for comparing the evolution of MDR-E among SOT recipients with neighbouring countries.

In summary, molecular typing of MDR-E revealed significant genetic diversity. E. coli producing blaCTX-M-G1 was the principal MDR-E colonizing strain in liver and/or kidney transplant recipients, followed by K. pneumoniae harbouring blaOXA-48 alone or with blaCTX-M-G1. Rectal colonization by MDR-E increased in the first month after transplantation compared to before transplantation; however, this was not reflected in the infections since there was a low rate of infection by MDR-E during the six-week post-transplantation follow-up.

Materials and methods

Study population and setting

This prospective cohort study, which is part of a prospective multicentre cohort study of intestinal colonization by MDR-E in kidney, liver or combined kidney and pancreas transplant recipients in seven Spanish University Hospitals (The ENTHERE study), was conducted between 29 August 2014 and 9 April 201823–25. Adult patients aged 18 years or older undergoing liver, kidney, or pancreas transplantation during the indicated period were included. Patients were followed up 24–48 h before transplantation, weekly until 6 weeks after transplantation, or until death, if this occurred within the indicated period. Intestinal colonization was defined as the isolation of MDR-E in a rectal swab. Infections were defined according to CDC criteria26.

Of the 931 patients included in the study, no MDR-E were isolated from any of the rectal swabs collected pre- or post-transplantation in 623 patients. In 308 patients in whom MDR-E was isolated in pre- and post-transplant samples, only 247 patient samples were sent to the coordination center for further analysis.

Bacterial strains

A total of 531 MDR-E isolates, defined as producing one or more ESBLs, plasmid-mediated or derepressed AmpC or carbapenemases, were included in this study. Rectal swabs were taken 24–48 h pre-transplantation and weekly up to 6 weeks post-transplantation and inoculated onto both ChromID-ESBL and ChromID-CARBA agar plates (BIOMERIEUX, Marcy L’Étoile, France). During the 6 weeks of follow-up, 10 isolates from patients who developed MDR-E infections were also included.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

All 541 MDR-E isolates underwent susceptibility testing for 24 antimicrobials, including amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (2 mg/L), piperacillin, piperacillin-tazobactam (4 mg/L), cefoxitin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefepime, aztreonam, imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem, amikacin, gentamicin, tobramycin, netilmicin, arbekacin, nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, fosfomycin, tigecycline, and colistin, by standardized broth-microdilution methods according to CLSI guidelines27. The results were interpreted using EUCAST clinical breakpoints28. No breakpoints have been established by EUCAST for arbekacin and nalidixic acid, so the MIC values have been specified. E. coli ATCC 25922, E. coli ATCC 35218, and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were used as quality control strains. Compounds with new β-lactamase inhibitors, such as ceftazidime-avibactam and meropenem-vaborbactam, were not available when the study was planned and consequently could not be tested.

Molecular fingerprinting

Genetic relatedness was first studied by repetitive-extragenic-palindromic PCR (REP-PCR)29 in all 541 MDR-E. Subsequently, the clonal relationship was also determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) in at least one strain per patient or strains from the same patient if they had two or more differing bands on REP-PCR.

Bacterial DNA was embedded in agarose plugs and digested with 20 U of XbaI at 37ºC overnight. The fragments were separated in 1% agarose gel at 6 V/cm and 14 °C with 0.5xTBE buffer using the CHEF-DRII-system (BIO-RAD, California, USA). Pulse times ranged from 1-5 s for 7 h and 15-35 s for 16 h.

PFGE-patterns were analysed with Fingerprinting II v4.5 software (BIO-RAD). Isolates were classified as indistinguishable if they showed > 95% similarity, as closely related subtypes with 85–95% similarity, and as different strains with similarity < 85%.

Molecular characterization of resistance genes

In a selection of 345 MDR-E isolates (one isolate per REP-PCR-pattern/patient and antibiogram pattern), standard-PCR was used to detect the presence of genes encoding ESBLs (blaTEM, blaSHV and blaCTX-M). PCR to detect carbapenemase genes (blaKPC, blaVIM, blaIMP, blaNDM and blaOXA-48) was performed in 90 out 345 MDR-E isolates with a meropenem MIC > 0.125 mg/L, as recommended by EUCAST. In 59 out of 345 isolates not producing an ESBL or carbapenemase gene, multiplex-PCR was performed to detect plasmid-mediated AmpC (blaCIT, blaFOX, blaMOX, blaDHA, blaACC and blaEBC).

The primers and PCR conditions used are provided in Supplementary Table 2 online. Representative amplification products were sequenced and analysed in GenBank (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST)

MLST was determined for 21 MDR-E isolates collected from 10 patients, including 10 isolates from post-transplantation clinical samples related to an infection and 11 isolates that colonized these infected patients, corresponding to the first rectal swab from which MDR-E were obtained.

Four Escherichia coli and 11 Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates were assessed using the Pasteur Institute protocols (https://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/index.html). For K. pneumoniae, the methodology was used as described30. PubMLST (https://pubmlst.org/databases/)31 was used to determine the sequence types (ST) of 2 Klebsiella oxytoca and 4 Enterobacter cloacae.

Ethics statement

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at all participating hospitals [Coordinating laboratory: Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, (Santander); Hospital Clínic (Barcelona); Hospital Cruces (Bilbao); Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Madrid); Hospital 12 de Octubre (Madrid); Hospital Ramón y Cajal (Madrid) and Hospital Reina Sofía (Córdoba)] according to local standards. Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mª Jesús Lecea and Laura Álvarez for technical assistance. This research was supported by ‘Plan Nacional de I+D+i and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias 13/01191), Subdirección General de Redes y Centros de Investigación Cooperativa, Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, and the Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI RD16/0016/0007, RD16/0016/0010, RD16/0016/0012, RD16/0016/0011, RD16/0016/0008, RD16/0016/0002). The study was co-financed by the European Development Regional Fund “A way to achieve Europe” and the Operative Program Intelligent Growth 2014‐2020.

Author contributions

M.F.-M., C.G.-R. L.M.-M. and M.C.F were responsible for the study's conception and designed the experiments. M.C.F obtained funding and M.F.-M. and C.G.-R. performed the experiments. Data acquisition, analysis or interpretation was performed by M.F.-M., C.G.-R. L.M.-M. and M.C.F. All authors contributed strains. M.F.M., L.M.M. and M.C.F. wrote the paper. All authors participated in critical revisions of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Marta Fernández Martínez, Claudia González-Rico, Luis Martínez-Martínez and Maria Carmen Fariñas.

A list of authors and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

Contributor Information

Marta Fernández-Martínez, Email: mfernandez@idival.org.

Luis Martínez-Martínez, Email: luis.martinez.martinez.sspa@juntadeandalucia.es.

Maria Carmen Fariñas, Email: mcarmen.farinas@scsalud.es.

ENTHERE Study Group, the Group for Study of Infection in Transplantation of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (GESITRA-SEIMC) and the Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI):

Carlos Salas, Carlos Armiñanzas, Francisco Arnaiz de las Revillas, Fernando Casafont-Morencos, Antonio Cuadrado Lavín, Emilio Fábrega, Concepción Fariñas-Álvarez, Virginia Flor Morales, Emilio Rodrigo, Juan Carlos Ruiz San Millán, Marta Bodro, Asunción Moreno, Laura Linares, Miquel Navasa, Frederic Cofan, Fernando Rodríguez, Julián Torre-Cisneros, Aurora Páez Vega, José Miguel Montejo, María José Blanco, Javier Nieto Arana, Jesús Fortún, Rosa Escudero Sánchez, Pilar Martin Dávila, Patricia Ruiz Garbajosa, Adolfo Martínez, Javier Graus, Ana Fernández, Patricia Muñoz, Maricela Valerio, Marina Machado, María Olmedo, Caroline Agnelli Bento, Cristina Rincón Sanz, María Luisa Rodríguez Ferrero, Luis Alberto Sánchez Cámara, José María Aguado, and Elena Resino

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-90382-5.

References

- 1.Aguado JM, et al. Management of multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacilli infections in solid organ transplant recipients: SET/GESITRA-SEIMC/REIPI recommendations. Transplant. Rev. 2018;32:36–57. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreno A, et al. Bloodstream infections among transplant recipients: results of a nationwide surveillance in Spain. Am. J. Transplant. 2007;7:2579–2586. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linares L, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in solid organ transplant recipients: epidemiology and antibiotic resistance. Transplant. Proc. 2010;42:2941–2943. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.07.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lanini S, et al. Incidence of carbapenem-resistant gram negatives in Italian transplant recipients: a nationwide surveillance study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0123706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adler A, Katz DE, Marchaim D. The continuing plague of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae Infections. Infect. Dis. Clin. North. Am. 2016;30:347–375. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oteo J, et al. Prospective multicenter study of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae from 83 hospitals in Spain reveals high in vitro susceptibility to colistin and meropenem. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59:3406–3412. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00086-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Errico G, et al. Colonization and infection due to carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in liver and lung transplant recipients and donor-derived transmission: a prospective cohort study conducted in Italy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019;25:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giannella M, et al. The impact of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization on infection risk after liver transplantation: a prospective observational cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019;25:1525–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freire MP, et al. Surveillance culture for multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria: performance in liver transplant recipients. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2017;45:e40–e44. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamandi B, Husain S, Grootendorst P, Papadimitropoulos EA. Clinical and microbiological epidemiology of early and late infectious complications among solid-organ transplant recipients requiring hospitalization. Transpl. Int. 2016;29:1029–1038. doi: 10.1111/tri.12808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantón R, González-Alba JM, Galán JC. CTX-M enzymes: origin and diffusion. Front. Microbiol. 2012;3:110. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodro M, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of bacteremia caused by drug-resistant ESKAPE pathogens in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2013;96:843–849. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182a049fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sánchez-López J, Cantón R. Current status of ESKAPE microorganisms in Spain: Epidemiology and resistance phenotypes. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 2019;32:27–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodríguez-Baño J, Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez B, Machuca I, Pascual A. Treatment of infections caused by extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-, AmpC-, and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018;31:e00079–e117. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00079-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tacconelli E, et al. ESCMID guidelines for the management of the infection control measures to reduce transmission of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in hospitalized patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014;20:1–55. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gagliotti C, et al. Infections in liver and lung transplant recipients: a national prospective cohort. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018;37:399–407. doi: 10.1007/s10096-018-3183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macesic N, et al. Genomic surveillance reveals diversity of multidrug-resistant organism colonization and infection: a prospective cohort study in liver transplant recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018;67:905–912. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bert F, et al. Pretransplant fecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and infection after liver transplant, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18:908–916. doi: 10.3201/eid1806.110139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pérez-Vázquez M, et al. Phylogeny, resistome and mobile genetic elements of emergent OXA-48 and OXA-245 Klebsiella pneumoniae clones circulating in Spain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016;71:887–896. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oteo J, et al. The spread of KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Spain: WGS analysis of the emerging high-risk clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae ST11/KPC-2, ST101/KPC-2 and ST512/KPC-3. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016;71:3392–3399. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruiz-Garbajosa P, et al. A single-day point-prevalence study of faecal carriers in long-term care hospitals in Madrid (Spain) depicts a complex clonal and polyclonal dissemination of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016;71:348–352. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonnin RA, et al. Emergence of new non-clonal group 258 high-risk clones among Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase-Producing K. pneumoniae Isolates, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:1212–1220. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.191517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramos-Vivas J, et al. Biofilm formation by multidrug resistant Enterobacteriaceae strains isolated from solid organ transplant recipients. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:8928–8938. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45060-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramos-Vivas J, et al. Adherence to human colon cells by multidrug resistant enterobacterias strains isolated from solid organ transplant recipients with a focus in Citrobacter freundii. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020;16:447. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fariñas MC, et al. Oral decontamination with colistin plus neomycin in solid organ transplant recipients colonized by multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales: a multicenter, randomized, controlled, open-label, parallel-group clinical trial. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020;23:1198. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2008;36:309–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically˗11th Edition: Approved Standard M7-A6. NCCLS, Wayne, PA, USA 2018.

- 28.The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 9.0, 2019. http://www.eucast.org.

- 29.Vila J, Marcos MA, de Jimenez AMT. A comparative study of different PCR-based DNA fingerprinting techniques for typing of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex. J. Med. Microbiol. 1996;44:482–489. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-6-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diancourt L, Passet V, Verhoef J, Grimont PA, Brisse S. Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:4178–4182. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.4178-4182.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jolley KA, Bray JE, Maiden MCJ. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;24:124. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.