Abstract

The genetic improvement of durum wheat and enhancement of plant performance often depend on the identification of stable quantitative trait loci (QTL) and closely linked molecular markers. This is essential for better understanding the genetic basis of important agronomic traits and identifying an effective method for improving selection efficiency in breeding programmes. Meta-QTL analysis is a useful approach for dissecting the genetic basis of complex traits, providing broader allelic coverage and higher mapping resolution for the identification of putative molecular markers to be used in marker-assisted selection. In the present study, extensive QTL meta-analysis was conducted on 45 traits of durum wheat, including quality and biotic and abiotic stress-related traits. A total of 368 QTL distributed on all 14 chromosomes of genomes A and B were projected: 171 corresponded to quality-related traits, 127 to abiotic stress and 71 to biotic stress, of which 318 were grouped in 85 meta-QTL (MQTL), 24 remained as single QTL and 26 were not assigned to any MQTL. The number of MQTL per chromosome ranged from 4 in chromosomes 1A and 6A to 9 in chromosome 7B; chromosomes 3A and 7A showed the highest number of individual QTL (4), and chromosome 7B the highest number of undefined QTL (4). The recently published genome sequence of durum wheat was used to search for candidate genes within the MQTL peaks. This work will facilitate cloning and pyramiding of QTL to develop new cultivars with specific quantitative traits and speed up breeding programs.

Subject terms: Quantitative trait, Plant breeding

Introduction

Durum wheat is an important cereal crop grown in a wide range of agricultural regions. The Mediterranean basin represents more than half of the world’s durum wheat growing area, but it is also grown in the northern plains of the United States and Canada, the desert areas in the southeast United States and northern Mexico, and to a minor extent in other regions.

(International Grain Council, https://www.igc.int/en/default.aspx), all of which are characterized by low rainfall. Wheat is successful due to its wide adaptation to local environments and good processing propertiesin the Mediterranean, soil water availability is a limiting factor incereal crop productivity,and biotic and abiotic stress may strongly affect wheat quality)1.

Water scarcity, often associated with high temperatures during the grain filling period, severely affects durum wheat quality and yield2,3. At this stage of the crop cycle,lack of water and high temperaturesreduce photosynthesis and the source-to-sink transportation of photosynthates in the caryopsis, thereby affecting the formation of the seed proteome. In contrast, excess moisture improves the yield by increasing starch concentrations in the caryopsis and therefore reducing the protein content. A crucial factor in determining the quality of semolina is the seed protein content (and its composition)4–6. In addition, as reported in7, genotype × environment effects can also alter the composition of the reserve proteome.

Therefore, improving breeding programs aim tocombine the highest number of desirable traits in the same genotype. Combining all the most favourable alleles in one cultivar translates into advantages for the miller and the consumer. High-quality kernels produce good quality flour with a balanced protein profile that guarantees high quality doughs and therefore end products with adequate texture and structure that meet consumer requirements. Certain traits not only satisfy consumers but also have nutritional value. An example is the colour of semolina: consumers generally appreciatea yellow pigmentation, which alsoindicates a high level of carotenoid pigments in the kernel. Combining the highest number of genes involved in carotenoid trait expressionis thereforea tool for both improving the nutritional value of wheat and satisfying consumers8.

In 2019 nearly 16 million tons of pasta were produced worldwide. Italy is the greatest consumer, with near 24 kg of pasta consumed per person each year (https://internationalpasta.org/). There is increasing awareness of the importance of wheat-based products in a healthy diet, and producers are identifying and exploiting natural variations in bioactive compounds. However, in some cases natural variations in a trait may be limited in extent or be difficult to exploit, so that other approaches may be required, as in this case. The most important targets of this type of approach are currently minerals, resistant starch, antioxidant compounds, carotenoids, protein content and dietary fibre. As mentioned earlier, quality is directly linked to biotic and abiotic stress. In recent years many quantitative trait loci (QTL) studies have focused on these traits, such as fiber content QTL in Marcotuli et al.9, root and shoot morphological traits in Iannucci et al.10, and many others reviewed in Colasuonno et al.11. These studies identified hundreds of QTL in different mapping populations with different types of markers besides. To identify the genome regions most involved in trait variationand the major, stable QTLs affecting these traits, the QTL meta-analysis approach developed by Goffinet and Gerber12 can help narrow down QTL regions, identify candidate genes and tackle map-based cloning strategies.

This approach allows the integration of independent QTL studies in a consensus mapor reference genome of the species. QTL meta-analysis is a powerful tool for discovering genome regions most frequently implicated in trait variation and forreducing the QTL confidence intervals, thereby enhancing the detection of candidate genes for positional cloning13. To identify meta-QTL (MQTL) for their use in marker-assisted breeding, Loffler et al.14 defined three criteria: (1) the MQTL must have a small supporting interval, (2) include a high number of original QTL, and (3) those QTL must have a large effect on the phenotypic variance explained.

Many of the traits mentioned above and analysed in the present paper are polygenic traits, and associated QTL have been located on all the tetraploid wheat chromosomes.

Meta-QTL (MQTL) analysis is a good instrument for studying many traits at once and finding the consensus, robust QTL region through the use of data reported in multiple studies for the reliability of their location and effect across different genetic backgrounds and environments, as well as to refine QTL positions on a consensus map12.The recent sequencing of the ‘Svevo’ durum wheat genome has enabled the identification of consensus genomic regions, the study of relationships among candidate genes within QTL, and the identification of pleiotropic effects among them15.

There are many examples in which MQTL analysis has also been successfully used to detect consensus QTL regions in wheat: root-related traits13,16, pre-harvest sprouting tolerance17, ear emergence18,19, resistance against Fusarium head blight20–22, plant height23, grain dietary fiber content24, seed size and shape25, yield-contributing traits24,26–28, resistance to leaf rust29; pasta-making quality30; potassium use efficiency31; drought tolerance32; tan spot resistance33. The objective of the present study was to focus on MQTL analysis of durum wheat progenies using a highly saturated consensus map from Macaferri et al.15, taking into account a high number of traits in order to identify major regions and possible pleiotropic gene effects.

Results

QTL distribution and projection

A total of 41QTL studies for quality, abiotic and biotic stress reported inColasuonno et al.11 were analysed, including 36 different traits (Table 1). The studies involved 34 different mapping populations, including 53 different parental accessions (Table 2). QTL projection was carried out using only QTL having the same flanking markers in the consensus map. A total of 368 QTL distributed on all 14 chromosomes (genomes A and B) were projected: 171 corresponded to quality-related traits; 127 to abiotic stress, and 71 to biotic stress.

Table 1.

Traits for biotic stress, abiotic stress and quality reported in the QTL meta-analysis.

| Trait | Description |

|---|---|

| Biotic stress | |

| CP | Clavicepspurpurea resistance |

| FHB | Fusarium head blight resistance |

| LR | Leaf rust resistance |

| LS | Loose smut resistance |

| PM | Powdery mildew resistance |

| SBCMV | Soil-borne cereal mosaic virus resistance |

| SR | Stem rust resistance |

| STB | Septoriatritici blotch resistance |

| YR | Yellow rust resistance |

| Abiotic stress | |

| CC | Chlorophyll content |

| CIR | Carbon isotope ratio |

| CL | Coleoptile length |

| DB | Dry biomass |

| FLRI | Flag leaf rolling index |

| NDVI | NDVI |

| OP | Osmotic potential |

| PDL | Length of the ear peduncle |

| RRT | Root related traits |

| SPAD | Chlorophyll content |

| Quality | |

| AX | Arabinoxylan |

| BG | β-glucan |

| Fb | Flour yellow colour |

| GCaC | Grain calcium concentration |

| GCuC | Grain copper concentration |

| GFeC | Grain iron concentration |

| GKC | Grain potassium concentration |

| GMgC | Grain magnesium concentration |

| GMnC | Grain mangnese concentration |

| GPC | Grain protein content |

| GSC | Grain sulphur concentration |

| GSeC | Grain selenium concentration |

| GseY | Grain selenium yield |

| GZnC | Grain zinc concentration |

| PGC | Phosphorus grain concentration |

| SV | SDS-sedimentation volume |

| YPC | Yellow pigment content |

Table 2.

Mapping populations used in the study and related references, including the years when experiments were done and the number of environments (Env).

| References | Cross | Type | Size | Trait | N QTL | Years | Env |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | Langdon × G18-16 | RIL | 156 | CIR, OP, CC, FLRI | 6, 9, 7, 9 | 2004 | 2 |

| 51 | Kofa × Svevo | RIL | 247 | PDL, SPAD, NDVI | 4, 3, 5 | 2004, 2005 | 8 |

| 52 | Omrabi5 × Belikh2 | RIL | 114 | CL, RRT | 5, 1 | 2009 | 2 |

| 53 | Colosseo × Lloyd | RIL | 176 | RRT | 28 | – | 1 |

| 53 | Meridiano × Caludio | RIL | 181 | RRT | 32 | – | 1 |

| 10 | Simeto × MolliseColli | RIL | 136 | RRT | 18 | – | 1 |

| 54 | Strongfield × Blackbird | DH | 85 | FHB | 2 | – | 1 |

| 55 | LDN × LDN-Dic7A | RIL | 118 | FHB | 1 | 2004, 2005 | 3 |

| 56 | Colosseo × Lloyd | RIL | 176 | LR | 1 | 2006, 2007 | 1 |

| 57 | Meridiano × Claudio | RIL | 181 | SBCMV | 1 | 2007, 2008 | 1 |

| 58 | DS × Td161 | BC | 134 | FHB | 1 | 2006, 2008 | 2 |

| 58 | Floradur × Td161 | BC | 129 | FHB | 3 | 2006, 2008 | 2 |

| 58 | Helidur × Td161 | BC | 126 | FHB | 1 | 2006, 2008 | 2 |

| 59 | Kristal × Sebatel | RIL | 85 | SR | 7 | 2008–2010 | 2 |

| 60 | Simeto × Levante | RIL | 180 | SBCMV | 7 | 2008, 2009 | 1 |

| 61 | BGRC3487 × 2 * DT735 | RIL | 160 | FHB | 2 | 2008–2010 | 2 |

| 62 | Cirillo × Neodur | RIL | 146 | SBCMV | 2 | 2008 | 1 |

| 63 | Wollaroi × Bansi | RIL | 92 | YR | 2 | 2007–2009 | 1 |

| 64 | Gerizim × Helidur | RIL | 103 | FHB | 1 | 2008, 2009 | 2 |

| 65 | Langdon × G18-16 | RIL | 157 | PM | 4 | – | 1 |

| 66 | Latino × MG5323 | RIL | 110 | LR | 3 | – | 1 |

| 67 | Ben × PI41025 | RIL | 200 | FHB | 3 | 2010–2012 | 1 |

| 68 | Sumai-3 × Saragolla | RIL | 135 | FHB | 11 | 2012, 2013 | 2 |

| 69 | Karur × DBC-480 | RIL | 111 | FHB | 1 | 2013–2015 | 1 |

| 70 | Strongfield × Blackbird | DH | 90 | LS | 2 | 2011, 2012 | 1 |

| 71 | Kofa × W9262-260D3 | DH | 155 | YR | 1 | 2013 | 1 |

| 72 | Joppa × 10Ae564 | RIL | 205 | FHB | 3 | 2015, 2016 | 2 |

| 73 | Rusty × PI 192051-1 | RIL | 180 | LR | 5 | 2017 | 2 |

| 74 | Ben × Tunisian 108 | BIL | 171 | FHB | 3 | 2010, 2011 | 2 |

| 75 | Greenshank × AC Avonlea | DH | 132 | CP | 4 | – | 2 |

| 76 | UC1113 × Kofa | BP | 93 | YPC | 4 | 2003–2006 | 2 |

| 50 | Langdon × G18-16 | RIL | 152 | GCaC, GCuC, GFeC, GKC, GMgC, GMnC, GPC, GSC, GZnC, PGC | 5, 10, 10, 8, 2, 2, 4, 5, 6, 3 | 2004 | 2 |

| 77 | DT695 × Strongfield | DH | 185 | GPC | 6 | 2002, 2003, 2005 | 3 |

| 78 | Latino × Primadur | BP | 121 | YPC | 4 | 2006, 2008 | 3 |

| 79 | UC1113 × Kofa | RIL | 93 | GPC, SV | 8, 10 | 2006, 2007 | 3 |

| 80 | UC1113 × Kofa | BP | 93 | F, YPC | 7, 6 | 2006, 2007 | 3 |

| 81 | Svevo × Ciccio | BP | 120 | YPC | 7 | 2006, 2007 | 2 |

| 82 | Duilio × Avonlea | RIL | 134 | BG | 2 | 2014 | 2 |

| 83 | Langdon × G18-16 | RIL | 152 | GSeC, GSeY | 9, 6 | 2005, 2007 | 2 |

| 8 | Colosseo × Lloyd | BP | 176 | YPC | 9 | – | – |

| 8 | Kofa × Svevo | BP | 249 | YPC | 9 | – | – |

| 8 | Meridiano × Claudio | BP | 181 | YPC | 6 | – | – |

| 84 | Svevo × Y12-3 | RIL | 208 | GPC | 12 | 2014, 2015 | 3 |

| 4 | Saragolla × 02-5B-318 | RIL | 135 | GPC | 4 | 2015–2017 | 1 |

| 61 | Pelissier × Strongfield | DH | 162 | SV | 6 | 2008–2010 | 2 |

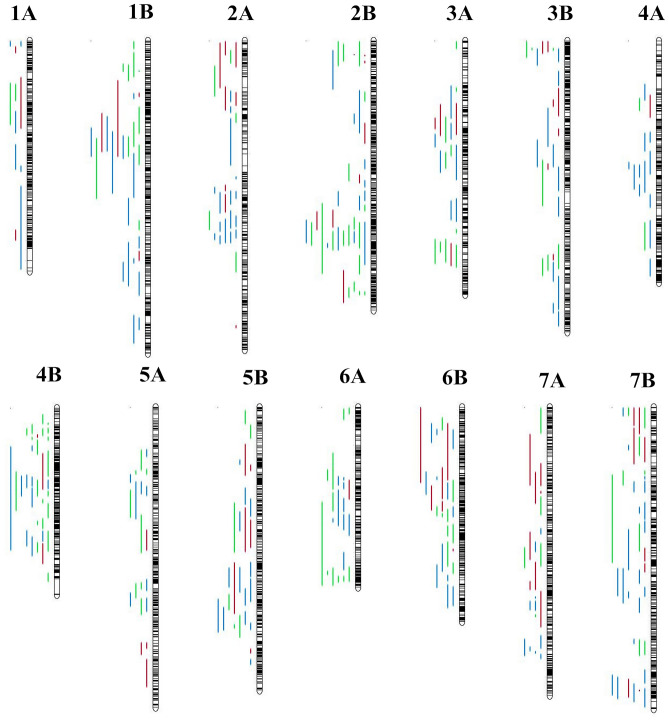

Differences in the number of projected QTL were observed not only among all the seven homoeologous groups, but also among individual chromosomes within a homoeologous group (Fig. 1).The number of projected QTL per genome was 144 (39%) and 244 (61%) for genomes A and B, respectively.The number of QTL per chromosome ranged from 11 in chromosome 1A to 40 in chromosomes 2B and 7B, with an average of 26 QTL per chromosome.

Figure 1.

QTL distribution along durum wheat genome chromosomes A and B. Colour code: green: abiotic stress QTL; orange: biotic stress QTL; blue: quality QTL. Black bars within chromosomes represent marker density.

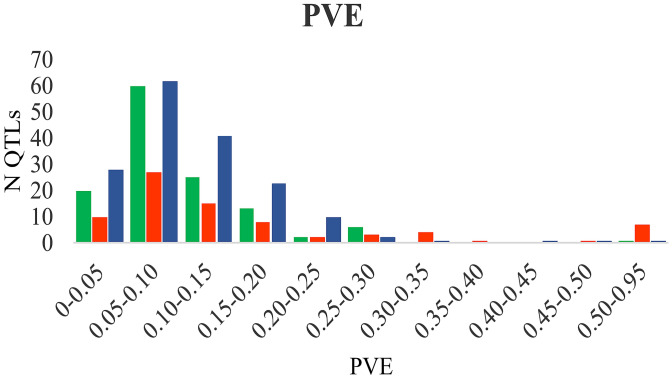

The means of the proportion of phenotypic variance explained (PVE) by the original QTL showed a similar pattern among the traits, with 63%, 53% and 48% of the QTL showing a PVE < 0.10, for abiotic stress, biotic stress and quality respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Phenotypic variance explained by original QTL. Colour code: green: abiotic stress QTL; orange: biotic stress QTL; blue: quality QTL.

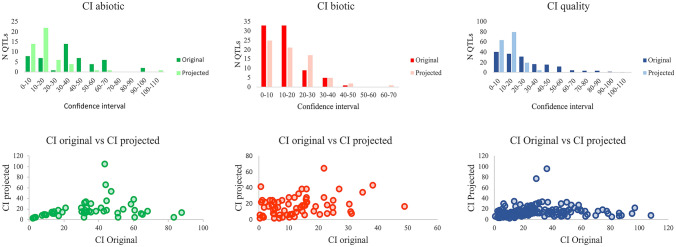

When the confidence interval (CI) was not reported in the original studies, it was calculated as the distance between the flanking markers. The CIs in the projected QTL were estimated at 95% using the empirical formula proposed by Guo et al. (2006). Comparison between CIs in original and projected QTL (Fig. 3) revealed clear differences for abiotic stress and quality traits. Most of the projected QTL for these traits showed lower CIs, with respective mean values of 35 cM and 18 cM for original and projected abiotic stress CIs and of 28 cM and 14 cMfor original and projected quality traits. In the case of biotic stress traits, instead, the original QTL showed lower CIs (mean 13 cM) than the projected QTL (mean 17 cM). For abiotic stress, 69% of the original QTL had CIs greater than 20 cM, whereas 73% of the projected QTL had CIs lower than 20 cM. For biotic stress traits, 79% and 65% of the original and projected QTL yielded CI values lower than 20 cM, respectively. Lastly, for quality traits, 54% of the original QTL had CIs greater than 20 cM, whereas 85% of the projected QTL yielded CIs lower than 20 cM.

Figure 3.

Comparison of confidence intervals for original and projected QTL and their correlation for the different traits.

QTL meta-analysis

Of the 368 QTL projected onto the consensus map of Maccaferri et al. (2015), 318 were grouped in 85 meta-QTL (MQTL) (Table 3) and 24 remained as single QTL not overlapping with MQTL. The remaining 26 QTLwere not assigned to any MQTL either, because their CI overlapped with different MQTL or because the predicted QTL peaks were not included within any MQTL. They were not considered as single QTL, as their CI overlapped with MQTL.

Table 3.

Characterization of MQTL.

| MQTL | Peak | N QTL | Traits | CI left (cM) | CI right (cM) | Left closest marker | Position (bp) | Right closest marker | Position (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| durumMQTL1A.1 | 3.5 | 3 | FHB, YPC, GPC | 2.1 | 5.0 | BS00064204_51 | 3,574,024 | wsnp_Ex_c2868_5293485 | 7,130,925 |

| durumMQTL1A.2 | 46.1 | 4 | LR, SR, CC, YPC | 41.2 | 50.9 | RAC875_c17283_453 | 48,029,342 | Tdurum_contig48416_335 | 362,986,005 |

| durumMQTL1A.3 | 92.7 | 2 | AX, SV | 90.1 | 95.4 | RAC875_c16149_298 | 509,524,234 | wsnp_Ex_c3258_6004611 | 521,653,795 |

| durumMQTL1A.4 | 142.0 | 2 | LR, YPC | 139.3 | 144.6 | wsnp_Ex_c3201_5910659 | 571,925,048 | CAP12_rep_c5332_341 | 576,427,845 |

| durumMQTL1B.1 | 16.9 | 4 | RRT | 16.5 | 17.4 | wPt-5006 | 16,362,423 | wPt-0655 | 17,484,592 |

| durumMQTL1B.2 | 29.3 | 2 | LR, YPC | 28.2 | 30.5 | TA002065-1430 | 52,576,257 | Kukri_c5861_360 | 65,241,426 |

| durumMQTL1B.3 | 55.3 | 10 | FHB, YPC, RRT, GPC, CL, AX, SV | 52.9 | 57.8 | BS00069723_51 | 449,298,414 | RAC875_c92464_53 | 478,463,076 |

| durumMQTL1B.4 | 95.3 | 2 | RRT, GPC | 92.5 | 98.1 | wsnp_Ex_rep_c71376_70138381 | 585,368,279 | BS00064162_51 | 594,840,328 |

| durumMQTL1B.5 | 117.6 | 5 | GseC, FHB, YPC, GPC | 116.2 | 119.0 | Kukri_rep_c97349_140 | 626,782,208 | BS00089790_51 | 633,135,607 |

| durumMQTL1B.6 | 151.3 | 2 | GseY, YPC | 149.8 | 152.7 | D_GBUVHFX01AHO3C_336 | 661,200,398 | IAAV6011 | 664,610,714 |

| durumMQTL2A.1 | 8.2 | 4 | FHB, SBCMV, BG, RRT | 4.9 | 11.6 | RFL_Contig4030_493 | 4,105,954 | D_contig79877_194 | 10,965,955 |

| durumMQTL2A.2 | 39 | 4 | LR, BG, FHB, NDVI | 36.1 | 42.3 | Kukri_c27040_309 | 29,530,680 | Ku_c23118_149 | 34,130,605 |

| durumMQTL2A.3 | 50.84 | 3 | NDVI, GPC, SPAD | 48.8 | 52.9 | Tdurum_contig32692_271 | 38,336,059 | Tdurum_contig46797_585 | 43,936,608 |

| durumMQTL2A.4 | 104.6 | 6 | YPC, SR, NDVI | 103.1 | 106.1 | gwm95 | 156,761,990 | Kukri_c52614_291 | 192,760,487 |

| durumMQTL2A.5 | 126.1 | 4 | FLRI, YPC, GZnC | 123.6 | 128.5 | Tdurum_contig42540_843 | 603,597,766 | Tdurum_contig101781_53 | 608,746,813 |

| durumMQTL2A.6 | 135.2 | 4 | GPC, GZnC, LR, YPC, GFeC | 133.5 | 136.9 | BobWhite_c34273_67 | 644,481,819 | wsnp_JD_c514_781859 | 671,466,946 |

| durumMQTL2B.1 | 10.8 | 5 | RRT, SBCMV, BG, SPAD, NVDI | 10.4 | 11.2 | BS00081871_51 | 11,131,675 | BS00085748_51 | 9,712,138 |

| durumMQTL2B.2 | 59.0 | 2 | GseY, GPC | 55.4 | 62.7 | Tdurum_contig74936_133 | 79,053,860 | Tdurum_contig59780_988 | 99,231,827 |

| durumMQTL2B.3 | 91.0 | 2 | NDVI, BG | 87.5 | 94.6 | RAC875_c5080_915 | 201,176,819 | RFL_Contig3353_125 | 404,189,154 |

| durumMQTL2B.4 | 102.9 | 2 | LR, GFeC | 100.5 | 105.3 | Ra_c106383_270 | 446,141,376 | RAC875_c992_370 | 493,056,835 |

| durumMQTL2B.5 | 115.0 | 3 | GFeC, SV, YPC | 112.0 | 118.0 | Excalibur_c84741_99 | 537,614,290 | wsnp_Ex_c114_229879 | 570,335,910 |

| durumMQTL2B.6 | 126.7 | 4 | RRT, GPC, NDVI, LR | 124.4 | 128.9 | GENE-1352_214 | 603,649,910 | IAAV5675 | 633,838,200 |

| durumMQTL2B.7 | 147.5 | 11 | GseY, LR, FLRI, RRT, GFeC | 145.8 | 149.1 | BobWhite_c27184_148 | 697,868,929 | Tdurum_contig17826_338 | 714,626,523 |

| durumMQTL2B.8 | 183.3 | 5 | NDVI, SPAD, PDL, PM | 183.2 | 183.5 | BS00065302_51 | 778,068,615 | BS00083998_51 | 778,539,953 |

| durumMQTL3A.1 | 61.8 | 5 | FHB, DB, NDVI, SBCMV | 58.4 | 65.1 | Tdurum_contig43850_140 | 117,216,598 | BS00063531_51 | 282,116,044 |

| durumMQTL3A.2 | 83.7 | 4 | LR, PDL, GFeC, STB | 80.4 | 87.1 | Tdurum_contig59531_914 | 532,975,275 | wsnp_Ku_c5378_9559013 | 560,465,228 |

| durumMQTL3A.3 | 123.5 | 2 | GSeC, AX | 117.7 | 129.4 | Kukri_c25064_120 | 649,262,262 | RAC875_c22641_993 | 739,903,219 |

| durumMQTL3A.4 | 150.2 | 5 | RRT | 148.9 | 151.6 | Tdurum_contig42495_389 | 705,563,307 | wsnp_Ex_c9377_15572157 | 707,002,492 |

| durumMQTL3B.1 | 6.3 | 7 | SPAD, NDVI, RRT, LR, PDL | 5.5 | 7.2 | Kukri_rep_c88385_226 | 6,221,552 | wsnp_Ex_c40595_47620787 | 6,886,922 |

| durumMQTL3B.2 | 45.7 | 2 | FHB | 42.7 | 48.8 | BobWhite_c62702_587 | 54,867,872 | GENE-1900_115 | 67,253,287 |

| durumMQTL3B.3 | 67.0 | 2 | SBCMV, YPC | 63.9 | 70.1 | RFL_Contig3857_548 | 133,186,432 | RAC875_c79844_323 | 167,491,237 |

| durumMQTL3B.4 | 91.7 | 5 | SR, SV | 89.2 | 94.2 | BobWhite_rep_c61884_158 | 516,937,853 | Kukri_c15521_2027 | 553,129,195 |

| durumMQTL3B.5 | 159.9 | 5 | RRT, YR, CL, RRT | 157.7 | 162.1 | BS00063624_51 | 772,236,110 | Kukri_c3243_1016 | 776,834,461 |

| durumMQTL3B.6 | 196.6 | 3 | YPC | 195.2 | 198.1 | RAC875_c111148_585 | 817,039,063 | wsnp_BE444579B_Ta_2_2 | 818,195,973 |

| durumMQTL4A.1 | 44.0 | 3 | GPC, CIR, LR | 40.3 | 47.7 | IACX62 | 46,560,597 | wsnp_Ex_c30989_39836034 | 88,066,155 |

| durumMQTL4A.2 | 71.6 | 2 | LR, GCuC | 67.8 | 75.4 | wsnp_BF484585A_Td_2_1 | 572,071,933 | TA005643-0627 | 583,594,297 |

| durumMQTL4A.3 | 92.7 | 5 | GPC, YPC, GCuC | 90.2 | 95.2 | Ku_c6779_1381 | 604,660,434 | Tdurum_contig61343_177 | 608,153,268 |

| durumMQTL4A.4 | 112.4 | 2 | SR, GCuC | 108.7 | 116.1 | wsnp_Ex_c41313_48161689 | 622,734,003 | BobWhite_c10610_149 | 635,190,258 |

| durumMQTL4A.5 | 154.5 | 3 | SR, CC | 151.2 | 157.9 | Kukri_c13761_379 | 702,329,076 | wPt-9196 | 707,410,962 |

| durumMQTL4B.1 | 11.6 | 2 | RRT, CL | 10.5 | 12.6 | Tdurum_contig29961_68 | 11,083,105 | wsnp_Ex_c10347_16946522 | 12,042,854 |

| durumMQTL4B.2 | 17.1 | 4 | RRT, CL | 15.5 | 18.7 | GENE-4933_489 | 13,403,076 | Tdurum_contig68677_480 | 18,074,456 |

| durumMQTL4B.3 | 21.7 | 3 | FHB, RRT | 20.7 | 22.7 | Kukri_c34633_69 | 20,795,117 | BS00022431_51 | 23,204,984 |

| durumMQTL4B.4 | 30.3 | 2 | GPC, NDVI | 28.0 | 32.7 | Tdurum_contig75738_113 | 26,056,520 | IACX47 | 30,112,862 |

| durumMQTL4B.5 | 54.6 | 6 | GMnC, GPC, AX, SV, GMnC | 51.5 | 57.8 | TA006298-0500 | 383,231,914 | wsnp_Ex_c16083_24512551 | 453,294,222 |

| durumMQTL4B.6 | 64.4 | 3 | GCuC, RRT, GseY | 62.9 | 65.9 | Tdurum_contig24612_209 | 504,883,147 | Kukri_c322_1394 | 524,075,645 |

| durumMQTL4B.7 | 82.8 | 2 | RRT | 81.0 | 84.6 | wsnp_Ex_c23638_32875196 | 607,834,125 | RAC875_c14455_1148 | 621,516,171 |

| durumMQTL4B.8 | 98.14 | 6 | YPC, GCuC, RRT | 95.8 | 100.5 | Tdurum_contig8322_966 | 646,421,893 | wsnp_Ex_c14138_22066009 | 652,716,927 |

| durumMQTL5A.1 | 48.6 | 3 | YPC, RRT | 47.1 | 50.0 | D_GA8KES402GAVSF_317 | 111,907,960 | Kukri_c25407_645 | 331,277,629 |

| durumMQTL5A.2 | 61.6 | 4 | GseC, YPC, AX | 58.6 | 64.6 | Tdurum_contig5481_369 | 395,919,866 | BS00022110_51 | 401,330,652 |

| durumMQTL5A.3 | 96.1 | 2 | SBCMV, SR | 89.1 | 103.1 | wsnp_BE443745A_Ta_2_1 | 439,542,927 | BobWhite_rep_c50888_306 | 468,004,808 |

| durumMQTL5A.4 | 131.1 | 3 | GCaC, CIR, RRT | 128.7 | 133.5 | CAP7_c4800_276 | 527,044,675 | Tdurum_contig60421_74 | 529,441,492 |

| durumMQTL5A.5 | 143.2 | 3 | GseY, OP, GPC | 139.9 | 146.6 | BobWhite_c40643_370 | 537,480,079 | Excalibur_c26671_57 | 553,019,889 |

| durumMQTL5A.6 | 175.6 | 3 | FHB | 174.9 | 176.3 | Excalibur_c4083_874 | 607,909,980 | Ku_c24141_700 | 610,522,247 |

| durumMQTL5B.1 | 9.9 | 2 | NDVI, SPAD | 5.9 | 13.8 | wsnp_Ku_c10586_17464696 | 9,787,752 | Tdurum_contig92396_380 | 17,218,406 |

| durumMQTL5B.2 | 42.0 | 3 | GPC, CP, FHB | 40.3 | 43.8 | Excalibur_c57167_475 | 84,059,870 | Excalibur_c15262_2304 | 327,019,780 |

| durumMQTL5B.3 | 69.3 | 2 | Fb | 64.4 | 74.2 | Tdurum_contig28754_218 | 439,553,088 | Kukri_c10296_1512 | 475,596,832 |

| durumMQTL5B.4 | 87.1 | 4 | FLRI, PM, GCaC, SR | 81.5 | 92.7 | GENE-3437_68 | 489,178,563 | Tdurum_contig53926_455 | 514,395,841 |

| durumMQTL5B.5 | 122.2 | 3 | GCaC, GPC, YPC | 118.0 | 126.4 | wsnp_Ex_c13485_21225504 | 559,774,294 | wsnp_Ra_c39562_47242455 | 576,849,094 |

| durumMQTL5B.6 | 139.0 | 3 | GMgC, CC, GCaC | 135.0 | 143.1 | Excalibur_rep_c88310_1394 | 588,418,255 | RFL_Contig3835_475 | 604,697,415 |

| durumMQTL5B.7 | 159.3 | 5 | YPC, CIR, OP | 157.8 | 160.8 | Tdurum_contig56335_223 | 643,149,387 | IACX3775 | 649,698,450 |

| durumMQTL6A.1 | 2.3 | 2 | NDVI | 0.0 | 4.9 | BobWhite_c43135_397 | 1,819,265 | Tdurum_contig41990_1324 | 7,436,293 |

| durumMQTL6A.2 | 53.7 | 6 | YPC, CL, LR, RRT, SR | 52.4 | 55.0 | Excalibur_c33110_52 | 323,649,274 | wsnp_Ex_c35545_43677480 | 443,168,317 |

| durumMQTL6A.3 | 81.3 | 6 | YPC, SV, CIR | 79.6 | 83.1 | BS00023893_51 | 552,510,396 | BS00065082_51 | 553,838,425 |

| durumMQTL6A.4 | 123.6 | 6 | RRT, NDVI, AX | 123.4 | 123.8 | BobWhite_c24258_496 | 602,232,048 | RAC875_c27781_591 | 602,503,159 |

| durumMQTL6B.1 | 18.1 | 5 | GKC, RRT, YPC, GKC | 15.8 | 20.3 | Excalibur_c72517_251 | 13,113,351 | Kukri_rep_c103034_636 | 17,165,695 |

| durumMQTL6B.2 | 61.0 | 5 | GKC, OP, FHB, NDVI | 56.8 | 65.3 | Tdurum_contig48689_514 | 126,247,427 | BS00073879_51 | 146,626,621 |

| durumMQTL6B.3 | 77.5 | 5 | RRT, GKC, YPC, FHB, RRT | 76.0 | 78.9 | IACX4889 | 442,381,268 | BS00089580_51 | 454,883,952 |

| durumMQTL6B.4 | 90.8 | 2 | RRT | 86.9 | 94.7 | wsnp_JG_c1834_901723 | 537,655,953 | Tdurum_contig44825_307 | 588,937,432 |

| durumMQTL6B.5 | 104.7 | 2 | LS, NDVI | 103.4 | 105.9 | TA004372-0730 | 621,526,724 | BS00011523_51 | 633,371,119 |

| durumMQTL6B.6 | 127.2 | 3 | PGC | 126.5 | 128.0 | BS00109717_51 | 662,889,085 | Tdurum_contig45914_283 | 663,681,523 |

| durumMQTL7A.1 | 61.6 | 5 | LR, SPAD, PDL, NDVI | 60.4 | 62.7 | Tdurum_contig31137_373 | 61,412,931 | RAC875_c10701_435 | 65,969,594 |

| durumMQTL7A.2 | 102.3 | 2 | FHB, YPC | 98.3 | 106.3 | BobWhite_c48548_106 | 131,332,420 | Tdurum_contig51089_1066 | 163,557,572 |

| durumMQTL7A.3 | 114.7 | 2 | RRT | 109.1 | 120.3 | RFL_Contig5676_748 | 200,976,557 | BS00069163_51 | 511,685,823 |

| durumMQTL7A.4 | 145.4 | 4 | YPC, Fb, SR, RRT | 142.8 | 147.9 | BS00044234_51 | 631,404,872 | BS00022202_51 | 641,161,271 |

| durumMQTL7A.5 | 175.7 | 3 | YPC, PGC | 173.7 | 177.7 | wPt-5558 | 682,897,955 | Tdurum_contig31699_276 | 691,003,050 |

| durumMQTL7A.6 | 179.6 | 2 | AX, YPC | 179.5 | 179.8 | Tdurum_contig31699_276 | 691,003,050 | Tdurum_contig31699_276 | 691,003,050 |

| durumMQTL7B.1 | 2.3 | 5 | RRT, GPC, FHB | 0.1 | 4.6 | Ex_c21249_1111 | 886,966 | Tdurum_contig49737_462 | 5,096,321 |

| durumMQTL7B.2 | 29.7 | 4 | FHB, CIR, GseY | 27.6 | 31.9 | RAC875_c10672_440 | 87,960,765 | wsnp_Ex_c36325_44308589 | 53,938,632 |

| durumMQTL7B.3 | 52.9 | 4 | RRT, YPC | 51.5 | 54.3 | BS00000170_51 | 103,606,730 | Excalibur_c1694_899 | 105,323,515 |

| durumMQTL7B.4 | 75.4 | 2 | GseC, Fb | 72.7 | 78.1 | Kukri_c9353_642 | 255,076,815 | RAC875_c22594_125 | 388,539,117 |

| durumMQTL7B.5 | 89.2 | 2 | GSC, AX | 84.8 | 93.6 | CAP8_c949_312 | 437,505,136 | Kukri_rep_c71356_236 | 512,177,803 |

| durumMQTL7B.6 | 116.4 | 3 | LR, YPC, YR | 113.8 | 119.0 | RAC875_c18043_411 | 578,959,591 | Excalibur_c58742_144 | 593,689,787 |

| durumMQTL7B.7 | 137.0 | 3 | GSeC, SR | 134.9 | 139.2 | wsnp_Ex_c10307_16890310 | 630,702,498 | Kukri_c31628_571 | 641,717,556 |

| durumMQTL7B.8 | 172.8 | 3 | YPC, RRT | 170.7 | 174.8 | wsnp_Ex_rep_c101269_86663549 | 684,341,861 | wsnp_Ex_c2365_4431185 | 687,868,244 |

| durumMQTL7B.9 | 206.53 | 7 | YPC, LR, Fb, SR, GPC | 206.5 | 206.6 | RAC875_rep_c106035_443 | 715,557,101 | Tdurum_contig28601_486 | 716,329,509 |

The number of MQTL per chromosome ranged from four in chromosomes 1A and 6A to 9 in chromosome 7B. Chromosomes 3A and 7A showed the highest number of individual QTL (4), chromosome 7B the highest number of undefined QTL (4). The number of QTL per MQTL ranged from 2 in 26 MQTL to 11 in the durumMQTL2B.7.As 41 MQTL (47%) derived from the clustering of QTL from threeor more different studies on different parental lines, they will be more stable across environments. The number of traits involved in each MQTL ranged from 1 in twelveMQTL to 7 in the MQTL durum MQTL1B.3. Six MQTL involved 5or more different traits (Table 3). The CI of the MQTL ranged from 0.1 to 14 cM, with an average of 4.9 cM. This isa significant reduction from the original QTL, whichranged from 0.4 to 108.1 cM, with an average of 25.5 cM.

The three criteria proposed by Löffler et al.14 were used toidentify the most promising MQTL for marker-assisted selection and candidate gene analysis: (1) small MQTL supportintervals, (2) large number of initial QTL and (3) high PVE values of the original QTL. A total of 17 MQTL were selected using the following criteria: a number of QTL per MQTL equal to or greater than 5, with a CI equal toor lower than the average (4.9), and a mean PVE value for the original QTL in the MQTL equal to or greater than 0.10 (Table 4).Only MQTL with a physical distance of less than 5 Mb were subsequently selected for candidate gene (CG) identification.

Table 4.

Selected MQTL.

| MQTL | QTL | CI (cM) | Distance between flanking markers (Mb) | PVE original QTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| durumMQTL2B.1 | 5 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.41 |

| durumMQTL2B.8 | 5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.10 |

| durumMQTL3A.4 | 5 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 0.11 |

| durumMQTL3B.1 | 7 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.11 |

| durumMQTL3B.5 | 5 | 4.4 | 4.6 | 0.13 |

| durumMQTL6A.3 | 6 | 3.5 | 1.3 | 0.10 |

| durumMQTL6A.4 | 6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.10 |

| durumMQTL6B.1 | 5 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 0.10 |

| durumMQTL7A.1 | 5 | 2.3 | 4.6 | 0.22 |

| durumMQTL7B.9 | 7 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.19 |

Candidate genes and in silico gene expression analysis

Candidate genes (CG) for investigating and estimating relative gene expression levels were identified within the MQTL regions reported in Table 4. The flanking markers of the CI were launched against the genome browser for both ‘Svevo’ (durum wheat)34 and ‘Chinese spring’ (bread wheat) (https://iwgs.org/) reference genomes. Excluding transposable elements, atotal of 436 and 326 gene modelswere detected for ‘Svevo’ and ‘Chinese Spring’ respectively (Additional file 1). Differentially expressed genes (DEG) upregulated under abiotic and biotic stress conditions (Table 5) and expressed in the grain tissues for quality CGs were subsequently analysed using the RNAseq data available at http://www.wheat-expression.com/35.

Table 5.

Number of genes detected for each MQTL.

| MQTL | Number of genes | |

|---|---|---|

| DURUM wheat | Bread wheat | |

| durumMQTL2B.1 | 29 | 42 |

| durumMQTL2B.8 | 8 | 11 |

| durumMQTL3A.4 | 24 | 32 |

| durumMQTL3B.1 | 20 | 22 |

| durumMQTL3B.5 | 111 | 45 |

| durumMQTL6A.3 | 20 | 8 |

| durumMQTL6A.4 | 16 | 4 |

| durumMQTL6B.1 | 107 | 69 |

| durumMQTL7A.1 | 104 | 69 |

| durumMQTL7B.9 | 17 | 24 |

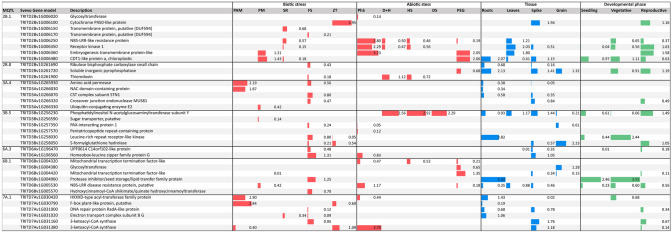

Thebread wheat gene models were analysed using the RNAseq experiments available at www.wheat-expression.com35,36. In particular, the study focused on identifying expression genes involved in biotic and abiotic stress, in different tissues and developmental phases (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Expressed genes involved in biotic and abiotic stress, in different tissues and developmental phases for each MQTL.

A total of 36 CGs upregulated under biotic and abiotic stress were found in seven MQTL. MQTL3B.1 and MQTL7B.9 in ‘Svevo’ and ‘Chinese spring’ did not yieldhomologous gene models, and no upregulated gene models were found for MQTL6A.4 (Fig. 4).

The genes most expressed during biotic stress conditions with respect to control conditionswithout stress were: (1) for expression analyses using pathogens associated molecular patterns (PAMP), F-box plant-like protein (7A.1), amino acid permease (3A.4), HXXXD-type acyl-transferase family protein (7A.1) and NAC domain-containing protein (3A.4); (2) for powdery mildew infection, CDT1-like protein and embryogenesis transmembrane protein (2A.1);( 3) for infection with Fusarium pseudograminearum, homeobox-leucine zipper family protein G (6A.3), protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer family protein (6B.1) and 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (7A.1); and (4) for infection with Zymoseptoriatritici, cytochrome P450-like protein (2B.1) and 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (7A.1) during stress.

Expression analysis under abiotic stress included: phosphorous starvation, drought stress, heat stress, combined drought and heat, addition of PEG 6000 to simulate drought and cold stress. No upregulated genes were found for cold stress. The most expressed genes identified associated to phosphorus starvation conditions were NBS-LRR disease resistance proteins (2B.1 and 7A.1), receptor kinase 1 (2B.1), embryogenesis transmembrane protein-like (2B.1) and 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (6B.1).

Phosphatidylinositol N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase subunit Y (3B.5) was differentially expressed under combined drought and heat and under those single conditions, whereas a thioredoxin (2B.8) was also expressed under combined drought and heat stress. Lastly, three genes were the most upregulated when simulating drought stress using PEG:CDT1-like protein a, chloroplastic (2B.1), embryogenesis transmembrane protein-like (2B.1) and mitochondrial transcription termination factor (6B.1).

According to the plant tissue where the genes were upregulated, the spikes showed the higher number of transcripts with expression levels higher than 1tpm (7), whereas the lower number was found in grain (3). From below ground to the top of the plant, the most expressed gene models were: (1) roots: protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer family protein (6B.1), leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase (3B.5), soluble inorganic pyrophosphatase (2B.8), CDT1-like protein (2B.1), HXXXD-type acyl-transferase family protein (7A.1), electron transport complex subunit B G (7A.1) and phosphatidylinositol N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase subunit Y (3B.5); (2) leaves: receptor kinase 1, Embryogenesis transmembrane protein-like, NBS-LRR-like resistance protein (2B.1), phosphatidylinositol N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase subunit Y (3B.5) and NBS-LRR disease resistance protein (6B.1); 3) cytochrome P450-like protein (2B.1), 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (7A.1), phosphatidylinositol N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase subunit Y (3B.5), soluble inorganic pyrophosphatase (2B.8), 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (7A.1), CDT1-like protein (2B.1), homeobox-leucine zipper family protein G (6A.3) and crossover junction endonuclease MUS81 (3A.4); and (4) grain: S-formylglutathione hydrolase (3B.5), soluble inorganic pyrophosphatase (2B.8) and glycosyl transferase (6B.1).

Three developmental phases were considered in expression analysis: seedling, vegetative, and reproductive. The most expressed genes in seedlings were protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer family protein (6B.1) and CDT1-like protein (2B.1), whereas during vegetative growth they were protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer family protein (6B.1), leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase (3B.5), CDT1-like protein (2B.1) and soluble inorganic pyrophosphatase (2B.8). Lastly, during the reproductive stage the most expressed gene models were receptor kinase 1, embryogenesis transmembrane protein (2B.1), phosphatidylinositol N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase subunit Y (3B.5), soluble inorganic pyrophosphatase (2B.8), cytochrome P450 protein (2B.1) and S-formylglutathione hydrolase (3B.5).

Gene expression in grains was analysed not only under biotic or abiotic stress conditions but also to detect candidate genes of importance in grain quality.

High expression levels (tpm > 2) were observed in grain for phospholipid-transporting ATPase, nascent polypeptide-associated complex subunit alpha-like protein, acetyltransferase component of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, polyadenylate-binding protein-interacting protein 4, acyl-CoA N-acyltransferase with RING 2FFYVE 2FPHD-type zinc finger protein, mitochondrial inner membrane protease subunit 1, S-formylglutathione hydrolase and peroxidase (on 3B.5, 6A.3 and 6B.1).

When grain tissues ofthe endosperm, embryo, aleurone layer, seed coat and transfer cells were dissected, all the genes described above for the whole grain were strongly expressed in at least one of the different tissues. Other gene models that expressed over 2 tpm were: glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [NAD( +)] in the aleurone layer and seed coat, a 28S ribosomal S34 protein in the embryo, S-acyltransferase in the aleurone layer, a pimeloyl-[acyl-carrier protein] methyl ester esterase in the aleurone layer, glycosyltransferase in the endosperm, hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein-like G in the aleurone layer and seed coat, histidine-containing phosphotransfer protein in the embryo, a general regulatory factor 1G in the embryo, aleurone layer and seed coat, S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent methyltransferase superfamily protein in the seed coat, an F-box in the aleurone layer, and phosphatidylinositol N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase subunit Y in the endosperm, embryo and seed coat.

Discussion

One of the main challenges of breeding programs is to increase crop yield. Crop productivity is highly affected by environmental constraints and diseases, so thatnew cultivars must incorporate new loci to cope with the different stresses affecting plant growth and yield. Breeders have another important challenge in the development of new cultivars: to improve grain quality for end products that meet industrial and consumer requirements.

In recent years numerous studies have been carried out to identify new loci controlling traits for abiotic and biotic stress tolerance and grain quality in bread and durum wheat. QTL meta-analysis has been carried out on most of the QTL identified in durum wheat for disease resistance, environmental tolerance and grain quality. This approach has been used extensively in plants since its development in 200437. It is especially useful in detecting major loci for quantitative traits and, by increasing map resolution, in identifying candidate genes controlling polygenic traits12.

This is the first study that provides an overview and comparison of genetic loci controlling multiple traits in durum wheat, including quality traits and biotic and abiotic traits. It adds new MQTL for durum grain traits: some of the MQTL were mapped with high precision and are relatively more robust and stable with major effects.

We report a total of 368 QTL distributed on all 14 chromosomes, of which 171 are related to quality traits, 127 to abiotic stress, and 71 to biotic stress, over a total of 34 mapping population. A total of 85 meta-QTL were identified, of which 15 meta-QTL were selected as the most promising for candidate gene selection.

The meta-analysis conducted in this study accurately compared genomic positions of individual QTL identified in different studies and refined the confidence intervals of the main genomic regions associated with different traits. The durum wheat consensus map15 preserved the marker order of individual maps, and confidence intervals were calculated to highlight differences between the original map position and its projection. For abiotic stress and quality traits, there was a reduction in the CI, whereas biotic stress traits showed an increase in the confidence interval. This may be due to the quantitative nature of the different traits; individual QTL for abiotic stress and quality showed lower PVE values, whereas those related to disease resistance yielded higher values (means of 0.11, 0.12 and 0.20 respectively). Biotic stress traits were controlled by a lower number of genes than traits related to abiotic stress or quality. Results reveal that the number of QTL per study was 25 for abiotic stress traits, 12 for quality related traits and 3 for biotic stress traits. Comparison of the reduction of CIs and number of genome regions involved in trait variation between this study and other studies carried out in durum wheat (quality)30, bread wheat (abiotic and biotic traits)13,29 and maize (yield)38 is reported in Additional file 3. Reduction of the CI and number of QTL after meta-analysis was 80% and 77% respectively, which is within the range among the different studies (from 60 to 88% for CI and from 65 to 90% for number of QTL).

The MQTL identified provide more closely linked markers due to the availability of a durum wheat consensus map15. Some of these are also linked to known major genes for other agronomically important traits, there by adding value to these MQTLas targets for marker assisted selection using the SNP markers flanking the MQTL, however an initial validation of the alleles reporting favourable effects should be addressed. According to the genome position of important agronomic genes reported in Liu et al.39, eleven MQTL were found to include 12 genes enhancing grain yield, quality, or plant development. DurumMQTL5A.5 and durumMQTL7B.9 included the vernalization genes Vrn-A1 and Vrn-B3 respectively. The incorporation of favourable alleles for this gene during breeding helps develop spring habit without cold requirements for flowering40, thus can be used as a strategy for introgressing important target traits from non-adapted pre-breeding materials combining the most favourable vernalization alleles. DurumMQTL4B.4 carries the dwarfing gene Rht-B1. Dwarfing genes were the basis of the green revolution, allowing an up to 35% increase in the yield of durum wheat41. Five durumMQTL, 2B.7, 4A.1, 7A.1, 7A.2 and 7A3, included genes involved in grain weight and size, the genes TaGS2-B1, TaCwi-A1, TaTEF-7A, TaGASR7-A1 and TaTGW-7A. Other genes affecting grain yield and quality were the TaSdr-A1 and TaALP-4A involved in preharvest sprouting tolerance and located in durumMQTL2A.4 and durumMQTL4A.5, respectively. Preharvest sprouting is an important limiting factor for grain yield in the major wheat production areas, especially when frequent rainfall occurs during harvest. Lastly, two genes involved in grain quality were found in durumMQTL1A.1 (Glu-A3) and durumMQTL7B.9 (Psy-B1). According to Subirà et al.42, the introgression of favorable alleles for HMW and LMW glutenin subunits led tothe improvement of pasta-making quality in modern durum wheat cultivars. The phytoene synthase gene Psy-B1 is involved in the biosynthesis of carotenoid pigments.

An interesting case of study was in the durumMQTL2B.1 where are co-located QTL for RRT (abiotic stress) and SBCMV (biotic stress). Looking at candidate gene reported in Fig. 4, NBS-LRR-like resistance genes were highly expressed in both abiotic and biotic stresses experiments, which may indicate a link between the two traits and a pleiotropic effect on root development and pathogen growth. This theory has been supported by Kochetov et al.43, which reported a differential expression of NBS-LRR-encoding genes detected in the root transcriptomes of two Solanumphureja.

The most promising MQTL arethe ones located on chromosome 1B (two MQTL), 2B (three MQTL), 3A (1 MQTL), 3B (two MQTL), 5B (1 MQTL), 6A (two MQTL), 6B (two MQTL), 7A (1 MQTL) and 7B (1 MQTL). These showed co-localized QTL for several grain traits, as found in earlier studies on bread wheat44–46, indicating that QTL are not randomly spread throughout the genome but cluster in specific genomic regions. The study of different MQTL has revealed how some traits are always associated, such as FHB, GPC and YPC (durumMQTL1B.3, durumMQTL1B.5 and durumMQTL6B.3) or RRT, SPAD and NVDI (durumMQTL2B.1, durumMQTL3B.1, durumMQTL6A.4, durumMQTL7A.1). This represents an important key for identifying and characterizing genes associated with the MQTL, with a pleiotropic effect on yield-related traits and quality traits.

To correlate between MQTL and previous QTL identified by GWAS, MQTL positions were compared with marker trait associations (MTA) reviewed by Colasuonno et al.11 for abiotic and biotic stress and quality traits. Of the 352 MTA, 58 were located within 33 durum MQTL. Of these, 37 MTA in 26 MQTL reported associations with one of the traits included in the MQTL (Additional file 2). The highest number of MTA per trait category corresponded to LR for biotic stress, NDVI for abiotic stress and YPC for grain quality. These MTA were distributed in 11 chromosomes. These results suggest that new bioinformatic tools are required to integrate association studies with QTL meta-analysis for better understanding the molecular bases of trait variation in crop species.

Conclusions

QTL meta-analysis can help validate QTL previously detected in different populations and unravel the most stable QTL for the most important wheat traits. This studyused QTL meta-analysis toacquirea comprehensive picture of the mainregions of the durum wheat genome involved in the control of multiple traits so as to identify QTL-enriched regions and candidate genes with possible pleiotropic effects.

The numerous markers within stable QTL and rich candidate gene regionscan helpelucidate the mechanism regulatingmany traits and speed up breeding programs for the production of top-quality cultivars.

Material and methods

Collection of QTL database and projection on a consensus map

A thorough bibliographic review was carried out on the literature reported in Colasuonno et al.11. QTL information on biparental durum wheat populations was retrieved from 41 independent studies, including a total of 36 different traits (Table 1) relating to quality (14), biotic stress (22) and abiotic stress (5).

Information on chromosome location, the most closely flanking markers, QTL position, logarithm of odds (LOD) values, confidence intervals (CIs) and phenotypic variance explained (PVE or r2) values are summarized in the review by Colasuonno et al.11.

To representall the QTL in one linkage map, the durum wheat consensus map developed by Maccaferri et al.15 was used for QTL projection, following the homothetic approach described by Chardon et al.37 as described in Colasuonno et al.11. The CIs for the projected QTL were estimated for a confidence interval of 95% using the empirical formula proposed by Guo et al.47.

QTL meta-analysis

QTL meta-analysis was conducted using BioMercator v.4.248, available at https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/Tools/BioMercator-V4, adopting the approach developed by Veyrieras et al.49. Meta-analysis determines the best QTL model based on model choice criteria from the Akaike information criterion (AIC), a corrected AIC, a Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and the average weight of evidence (AWE). The best QTL model was selected when the lowest values of the model selection criteria were achieved in at least threemodels. Consensus QTL from the optimum model were regarded as MQTL.

Identification of candidate genes underlying the MQTL region and expression analysis

Gene models within MQTL were identified using the high-confidence genes reported for the durum wheat reference sequence34, available at https://wheat.pw.usda.gov/GG3/jbrowse_Durum_Svevo based on the positions of markers flanking the CI of the MQTL.

In silico expression analysis and the identification of upregulated gene models was carried out using the RNAseq data available at http://www.wheat-expression.com/35 using gene models, from ‘Chinese spring’, located within the markers flanking the MQTL (https://iwgs.org/). Homologous genes from ‘Svevo’ were subsequently identified in durum wheat.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the PRIMA 2019 “CEREALMED” project (Italy), PON-AIM Project AIM1812334 (Ministerodell’Istruzione, dell’Università e dellaRicerca, Italy) and project PID2019-109089RB-C31 (Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Spain). JMS is supported by the CERCA programme/Generalitat de Catalunya (http://cerca.cat/).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jose Miguel Soriano, Email: josemiguel.soriano@irta.cat.

Ilaria Marcotuli, Email: ilaria.marcotuli@uniba.it.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-91446-2.

References

- 1.Reynolds M, Tattaris M, Cossani CM, Ellis M, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Pierre CS. Exploring genetic resources to increase adaptation of wheat to climate change. In: Ogihara Y, Takumi S, Handa H, editors. Advances in wheat genetics: From genome to field. Tokyo: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flagella Z, Giuliani M, Giuzio L, Volpi C, Masci S. Influence of water deficit on durum wheat storage protein composition and technological quality. Eur J Agron. 2010;33:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2010.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xynias IN, Mylonas I, Korpetis EG, Ninou E, Tsaballa A, Avdikos ID, Mavromatis AG. Durum wheat breeding in the mediterranean region: current status and future prospects. Agronomy. 2020;10:432. doi: 10.3390/agronomy10030432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giancaspro A, Giove SL, Zacheo SA, Blanco A, Gadaleta A. Genetic variation for protein content and yield-related traits in a durum population derived from an inter-specific cross between hexaploid and tetraploid wheat cultivars. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1509. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laino P, Shelton D, Finnie C, De Leonardis A, Mastrangelo A, Svensson B, et al. Comparative proteome analysis of metabolic proteins from seeds of durum wheat (cv. Svevo) subjected to heat stress. Proteomics. 2010;10:2359–2368. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gadaleta A, Blechl AE, Nguyen S, Cardone MF, Ventura M, Quick JS, et al. Stably expressed D-genome-derived HMW glutenin subunit genes transformed into different durum wheat genotypes change dough mixing properties. Mol Breed. 2008;22(2):267–279. doi: 10.1007/s11032-008-9172-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colasuonno P, Marcotuli I, Cutillo S, Simeone R, Blanco A, Gadaleta A. Effect of barley chromosomes on the β-glucan content of wheat. Genet Res Crop Evol. 2020;67:561–567. doi: 10.1007/s10722-019-00829-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colasuonno P, Marcotuli I, Blanco A, Maccaferri M, Condorelli GE, Tuberosa R, et al. Carotenoid pigment content in durum wheat (Triticumturgidum L. vardurum), an overview of quantitative trait loci and candidate genes. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1347. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcotuli I, Houston K, Waugh R, Fincher GB, Burton RA, Blanco A, et al. Genome wide association mapping for arabinoxylan content in a collection of tetraploid wheats. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0132787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iannucci A, Marone D, Russo MA, De Vita P, Miullo V, Ferragonio P, et al. Mapping QTL for Root and shoot morphological traits in a durum wheat × T dicoccum segregating population at seedling stage. Int J Genom. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/6876393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colasuonno P, Marcotuli I, Gadaleta A, Soriano JM. From genetic maps to QTL cloning: An overview for durum wheat. Plants. 2021;10:315. doi: 10.3390/plants10020315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goffinet B, Gerber S. Quantitative trait loci: A meta-analysis. Genetics. 2000;155:463–473. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soriano JM, Alvaro F. Discovering consensus genomic regions in wheat for root-related traits by QTL meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9:10537. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47038-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loffler M, Schon CC, Miedaner T. Revealing the genetic architecture of FHB resistance in hexaploid wheat (Triticumaestivum L.) by QTL meta-analysis. Mol Breed. 2009;23:473–488. doi: 10.1007/s11032-008-9250-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maccaferri M, Ricci A, Salvi S, Milner SG, Noli E, Martelli PL, et al. A high-density, SNP-based consensus map of tetraploid wheat as a bridge to integrate durum and bread wheat genomics and breeding. Plant Biotechnol J. 2015;13:648–663. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acunã-Galindo MA, Mason RE, Subramanian NK, Hays DB. Meta-analysis of wheat QTL regions associated with adaptation to drought and heat stress. Crop Sci. 2015;55:477–492. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2013.11.0793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tyagi S, Gupta PK. Meta-analysis of QTL involved in preharvest sprouting tolerance and dormancy in bread wheat. Triticeae Genom Genet. 2012;3:9–24. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanocq E, Laperche A, Jaminon O, Laine AL, Le Gouis J. Most significant genome regions involved in the control of earliness traits in bread wheat, as revealed by QTL meta-analysis. Theor Appl Genet. 2007;114:569–584. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0459-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffiths MD. Minimizing harm from gambling: What is the gambling industry's role? Addiction. 2009;104:696–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Häberle J, Holzapfel J, Schweizer G, Hartl L. A major QTL for resistance against Fusarium head blight in European winter wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;119:325–332. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu S, Hall MD, Griffey CA, McKendry AL. Meta-analysis of QTL associated with Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Crop Sci. 2009;49:1955–1968. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2009.03.0115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Löffler M, Schön C, Miedaner T. Revealing the genetic architecture of FHB resistance in hexaploid wheat (Triticumaestivum L) by QTL meta-analysis. Mol Breed. 2009;23:473–488. doi: 10.1007/s11032-008-9250-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffiths S, Simmonds J, Leverington M, Wang Y, Fish L, Sayers L, et al. Meta-QTL analysis of the genetic control of crop height in elite European winter wheat germplasm. Mol Breed. 2012;29:159–171. doi: 10.1007/s11032-010-9534-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quraishi UM, Pont C, Ain Q-U, Flores R, Burlot L, Alaux M, et al. Combined genomic and genetic data integration of major agronomical traits in bread wheat (Triticumaestivum L.) Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1843. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gegas VC, Nazari A, Griffiths S, Simmonds J, Fish L, Orford S, et al. A genetic framework for grain size and shape variation in wheat. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1042–1046. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.074153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang LY, Liu DC, Guo XL, Yang WL, Sun JZ, Wang DW, et al. Genomic distribution of quantitative trait loci for yield and yield-related traits in common wheat. J Integr Plant Biol. 2010;52:996–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soriano JM, Malosetti M, Roselló M, Sorrells ME, Royo C. Dissecting the old Mediterranean durum wheat genetic architecture for phenology, biomass and yield formation by association mapping and QTL meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0178290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avni R, Oren L, Shabtay G, et al. Genome based meta-QTL analysis of grain weight in tetraploid wheat identifies rare alleles of GRF4 associated with larger grains. Genes. 2018;9:636. doi: 10.3390/genes9120636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soriano JM, Royo C. Dissecting the genetic architecture of leaf rust resistance in wheat by QTL meta-analysis. Phytopathology. 2015;105:1585–1593. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-05-15-0130-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roselló M, Royo C, Álvaro F, Villegas D, Nazco R, Soriano JM. Pasta-Making quality QTLome from mediterranean durum wheat landraces. Front Plant Sci. 2017;9:1512. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Safdar LB, Andleeb T, Latif S, Umer MJ, Tang M, Li X, et al. Genome-wide association study and QTL meta-analysis identified novel genomic loci controlling potassium use efficiency and agronomic traits in bread wheat. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:70. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar A, Saripalli G, Jan I, Kumar K, Sharma PK, Balyan HS, Gupta PK. Meta-QTL analysis and identification of candidate genes for drought tolerance in bread wheat (Triticumaestivum L.) Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2020;26:1713–1725. doi: 10.1007/s12298-020-00847-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Salsman E, Wang R, Galagedara N, Zhang Q, Fiedler JD, et al. Meta-QTL analysis of tan spot resistance in wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2020;133:2363–2375. doi: 10.1007/s00122-020-03604-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maccaferri M, Harris NS, Twardziok SO, Pasam RK, Gundlach H, Spannagl M, et al. Durum wheat genome reveals past domestication signatures and future improvement targets. Nat Genet. 2019;51:885–895. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0381-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramirez-Gonzalez RH, Borrill P, Lang D, Harrington SA, Brinton J, Venturini L, et al. The transcriptional landscape of polyploid wheat. Science. 2018;361:6403. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borrill P, Ramirez-Gonzalez R, Uauy C. expVIP: A customizable RNA-seq data analysis and visualization platform. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:2172–2186. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chardon F, Virlon B, Moreau L, Falque M, Joets J, Decousset L, et al. Genetic architecture of flowering time in maize as inferred from quantitative trait loci meta-analysis and synteny conservation with the rice genome. Genetics. 2004;168(4):2169–2185. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.032375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez AK, Soriano JM, Tuberosa R, Koumproglou R, Jahrmann T, Salvi S. Yield QTLome distribution correlates with gene density in maize. Plant Sci. 2016;242:300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu J, Rasheed A, He Z, Imtiaz M, Arif A, Mahmood T, et al. Genome-wide variation patterns between landraces and cultivars uncover divergent selection during modern wheat breeding. Theor Appl Genet. 2019;132:2509–2523. doi: 10.1007/s00122-019-03367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Royo C, Dreisigacker S, Ammar K, Villegas D. Agronomic performance of durum wheat landraces and modern cultivars and its association with genotypic variation in vernalization response (Vrn-1) and photoperiod sensitivity (Ppd-1) genes. Eur J Agron. 2020;120:126129. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2020.126129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Royo C, Elias EM, Manthey FA. Durum wheat breeding. In: Carena MJ, editor. Handbook of plant breeding: Cereals. Springer; 2009. pp. 199–226. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subirà J, Peña RJ, Álvaro F, Ammar K, Ramdani A, Royo C. Breeding progress in the pasta-making quality of durum wheat cultivars released in Italy and Spain during the 20th Century. Crop Pasture Sci. 2014;65:16–26. doi: 10.1071/CP13238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kochetov AV, Glagoleva AY, Strygina KV, et al. Differential expression of NBS-LRR-encoding genes in the root transcriptomes of two Solanum phureja genotypes with contrasting resistance to Globoderarostochiensis. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:251. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1193-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dholakia BB, Ammiraju JSS, Singh H, Lagu MD, Röder MS, Rao VS, et al. Molecular marker analysis of kernel size and shape in bread wheat. Plant Breed. 2003;122:392–395. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0523.2003.00896.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breseghello F, Sorrells ME. QTL analysis of kernel size and shape in two hexaploid wheat mapping populations. Field Crops Res. 2007;101:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2006.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun XY, Wu K, Zhao Y, Kong FM, Han GZ, Jiang HM, Huang XJ, Li R-J, Wang HG, Li SS. QTL analysis of kernel shape and weight using recombinant inbred lines in wheat. Euphyt. 2008;165:615–624. doi: 10.1007/s10681-008-9794-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo B, Sleper DA, Lu P, Shannon JG, Nguyen HT, Arelli PR. QTL associated with resistance to soybean cyst nematode in soybean: Meta-analysis of QTL locations. Crop Sci. 2006;46:595–602. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2005.04-0036-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arcade A, Labourdette A, Falque M, Mangin B, Chardon F, Charcosset A, et al. BioMercator: Integrating genetic maps and QTL towards discovery of candidate genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;22(20):2324–2326. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Veyrieras JB, Goffinet B, Charcosset A. MetaQTL: A package of new computational methods for the meta-analysis of QTL mapping experiments. BMC Bioinform. 2007;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peleg Z, Cakmak I, Ozturk L, Yazici A, Jun Y, Budak H, et al. Quantitative trait loci conferring grain mineral nutrient concentrations in durum wheat × wild emmer wheat RIL population. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;119:353–369. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1044-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Graziani M, Maccaferri M, Royo C, Salvatorelli F, Tuberosa R. QTL dissection of yield components and morpho-physiological traits in a durum wheat elite population tested in contrasting thermo-pluviometric conditions. Crop Pasture Sci. 2014;65:80–95. doi: 10.1071/CP13349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nagel M, Navakode S, Scheibal V, Baum M, Nachit M, Röder MS, et al. The genetic basis of durum wheat germination and seedling growth under osmotic stress. Biol Plant. 2014;58:681–688. doi: 10.1007/s10535-014-0436-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maccaferri M, El-Feki W, Nazemi G, Salvi S, Cané MA, Colalongo C, et al. Prioritizing quantitative trait loci for root system architecture in tetraploid wheat. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:1161–1178. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Somers DJ, Fedak G, Clarke J, Cao W. Mapping of FHB resistance QTL in tetraploid wheat. Genome. 2006;49:1586–1593. doi: 10.1139/g06-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kumar S, Stack RW, Friesen TL, Faris JD. Identification of a novel fusarium head blight resistance quantitative trait locus on chromosome 7A in tetraploid wheat. Phytopathology. 2007;97:592–597. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-97-5-0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maccaferri M, Mantovani P, Tuberosa R, DeAmbrogio E, Giuliani S, Demontis A, et al. A major QTL for durable leaf rust resistance widely exploited in durum wheat breeding programs maps on the distal region of chromosome arm 7BL. Theor Appl Genet. 2008;117:1225–1240. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0857-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maccaferri M, Sanguineti MC, Demontis A, El-Ahmed A, Garcia, del, Moral, L.,, et al. Association mapping in durum wheat grown across a broad range of water regimes. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:409–438. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buerstmayr M, Huber K, Heckmann J, Steiner B, Nelson J, Buerstmayr H. Mapping of QTL for Fusarium head blight resistance and morphological and developmental traits in three backcross populations derived from Triticumdicoccum × Triticum durum. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;125:1751–1765. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-1951-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haile JK, Nachit MM, Hammer K, Badebo A, Röder MS. QTL mapping of resistance to race Ug99 of Pucciniagraminis f. sp. tritici in durum wheat (Triticum durumDesf.) Mol Breed. 2012;30:1479–1493. doi: 10.1007/s11032-012-9734-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maccaferri M, Francia R, Ratti C, Rubies-Autonell C, Colalongo C, Ferrazzano G, et al. Genetic analysis of Soil-Borne Cereal Mosaic Virus response in durum wheat: Evidence for the role of the major quantitative trait locus QSbm.ubo-2BS and of minor quantitative trait loci. Mol Breed. 2012;29:973–988. doi: 10.1007/s11032-011-9673-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruan Y, Comeau A, Langevin F, Hucl P, Clarke J, Brule-Babel A, Pozniak C. Identification of novel QTL for resistance to Fusarium head blight in a tetraploid wheat population. Genome. 2012;55:853–864. doi: 10.1139/gen-2012-0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Russo MA, Ficco DBM, Marone D, De Vita P, Vallega V, Rubies-Autonell C, et al. A major QTL for resistance to soil-borne cereal mosaic virus derived from an old Italian durum wheat cultivar. J Plant Interact. 2012;7:290–300. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2011.640437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bansal UK, Kazi AG, Singh B, Hare RA, Bariana HS. Mapping of durable stripe rust resistance in a durum wheat cultivar Wollaroi. Mol Breed. 2013;33:51–59. doi: 10.1007/s11032-013-9933-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buerstmayr M, Alimari A, Steiner B, Buerstmayr H. Genetic mapping of QTL for resistance to Fusarium head blight spread (type 2 resistance) in a Triticumdicoccoides × Triticum durum backcross-derived population. Theor Appl Genet. 2013;126:2825–2834. doi: 10.1007/s00122-013-2174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ben-David R, Peleg Z, Dinoor A, Saranga Y, Korol AB, Fahima T. Genetic dissection of quantitative powdery mildew resistance loci in tetraploid wheat. Mol Breed. 2014;34:1647–1658. doi: 10.1007/s11032-014-0178-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Desiderio F, Guerra D, Rubiales D, Piarulli L, Pasquini M, Mastrangelo AM, et al. Identification and mapping of quantitative trait loci for leaf rust resistance derived from a tetraploid wheat Triticumdicoccum accession. Mol Breed. 2014;34:1659–1675. doi: 10.1007/s11032-014-0186-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang Q, Axtman JE, Faris JD, Shiaoman C, Zengcui Z, Timothy LF, et al. Identification and molecular mapping of quantitative trait loci for Fusarium head blight resistance in emmer and durum wheat using a single nucleotide polymorphism-based linkage map. Mol Breed. 2014;34:1677–1687. doi: 10.1007/s11032-014-0180-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Giancaspro A, Giove SL, Zito D, Blanco A, Gadaleta A. Mapping QTL for Fusarium head blight resistance in an interspecific wheat population. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1381. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prat N, Guilbert C, Prah U, Wachter E, Steiner B, Langin T, et al. QTL mapping of Fusarium head blight resistance in three related durum wheat populations. Theor Appl Genet. 2017;130:13–27. doi: 10.1007/s00122-016-2785-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumar S, Knox RE, Singh AK, DePaw RM, Campbell HR, Isidro-Sanchez J, et al. High-density genetic mapping of a major QTL for resistance to multiple races of loose smut in a tetraploid wheat cross. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0192261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin X, N’Diaye A, Walkowiak S, Nilsen KT, Cory AT, Haile J, et al. Genetic analysis of resistance to stripe rust in durum wheat (Triticumturgidum L. var. durum) PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0203283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhao M, Leng Y, Chao S, Xu SS, Zhong S. Molecular mapping of QTL for Fusarium head blight resistance introgressed into durum wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2018;131:1939–1951. doi: 10.1007/s00122-018-3124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aoun M, Kolmer JA, Rouse MN, Elias EM, Breiland M, Bulbula WD, et al. Mapping of novel leaf rust and stem rust resistance genes in the Portuguese durum wheat landrace PI 192051. G3. 2019;9:2535–2547. doi: 10.1534/g3.119.400292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pirseyedi SM, Kumar A, Ghavami F, Hegstad JB, Mergoum M, Mazaheri M, et al. Mapping QTL for Fusarium head blight resistance in a Tunisian-derived durum wheat population. Cereal Res Commun. 2019;47:78–87. doi: 10.1556/0806.46.2018.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gordon A, McCartney C, Knox RE, Ereful N, Hiebert CW, Konkin DJ, et al. Genetic and transcriptional dissection of resistance to Clavicepspurpurea in the durum wheat cultivar Greenshank. Theor Appl Genet. 2020;133:1873–1886. doi: 10.1007/s00122-020-03561-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang W, Dubcovsky J. Association between allelic variation at the Phytoene synthase 1 gene and yellow pigment content in the wheat grain. Theor Appl Genet. 2008;116:635–645. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0697-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Suprayogi Y, Pozniak CJ, Clarke FR, Clarke JM, Knox RE, Singh AK. Identification and validation of quantitative trait loci for grain protein concentration in adapted Canadian durum wheat populations. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;119:437–448. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Blanco A, Colasuonno P, Gadaleta A, Mangini G, Schiavulli A, Simeone R, et al. Quantitative trait loci for yellow pigment concentration and individual carotenoid compounds in durum wheat. J Cereal Sci. 2011;54:255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2011.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Conti V, Roncallo PF, Beaufort V, Cervigni GL, Miranda R, Jensen CA, Echenique VC. Mapping of main and epistatic effect QTL associated with grain protein and gluten strength using a RIL population of durum wheat. J Appl Genet. 2011;52:287–298. doi: 10.1007/s13353-011-0045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roncallo P, Cervigni G, Jensen C, Miranda R, Carrera A, Helguera M, et al. QTL analysis of main and epistatic effects for flour color traits in durum wheat. Euphytica. 2012;185:77–92. doi: 10.1007/s10681-012-0628-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Colasuonno P, Gadaleta A, Giancaspro A, Nigro D, Give S, Incerti O, et al. Development of a high-density SNP-based linkage map and detection of yellow pigment content QTL in durum wheat. Mol Breed. 2014;34:1563–1578. doi: 10.1007/s11032-014-0183-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marcotuli I, Gadaleta A, Mangini G, Signorile AM, Zacheo SA, Blanco A, et al. Development of a high-density SNP-based linkage map and detection of QTL for beta-glucans, protein content, grain yield per spike and heading time in durum wheat. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1329. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yan J, Xue WT, Yang RZ, Qin HB, Zhao G, Tzion F, et al. Quantitative trait loci conferring grain selenium nutrient in durum wheat × wild emmer wheat RIL population. Czech J Genet Plant Breed. 2018;54:52–58. doi: 10.17221/112/2016-CJGPB. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fatiukha A, Lupo I, Lidzbarsky G, Klymiuk V, Korol AB, Pozniak C, et al. Grain protein content QTL identified in a Durum × wild emmer wheat mapping population tested in five environments. bioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/601773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].