To the Editor:

Historically, international medical graduates born outside the United States have comprised a vital portion of the nephrology workforce. In 2020, 4 of 10 matched nephrology fellowship positions were filled by non-US international medical graduates.1 Moreover, among all specialties participating in the 2020 National Resident Matching Program, nephrology ranked in the top 5 specialties, with the highest percentage of positions filled by non-US international medical graduates.2 Notably, non-US international medical graduate trainees are often challenged by unique obstacles related to their immigration status, such as meeting visa requirements and stringent deadlines or ineligibility to receive federal funding for research endeavors. Non-US international medical graduate trainees may also experience difficulties finding employment after training, as suggested by results from the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) 2019 Nephrology Fellow Survey.3

Although challenges faced by non-US international medical graduates are not new and are multifactorial, knowledge gaps may exist among nephrology fellowship leaders that, if filled, could facilitate addressing such challenges. For this reason, the ASN Diversity and Inclusion Committee conducted a survey of nephrology fellowship leaders to evaluate awareness of non-US international medical graduates’ (IMG's) immigration-related hindrances. Specifically, “Perceptions of IMG Visa Issues and Opportunities (PIVIO)” surveyed division chiefs, program directors, and associate program directors of academic centers with nephrology fellowships.

The PIVIO survey was electronically disseminated through the division chiefs and training program exchange communities on the ASN website between October 2, 2019, and November 29, 2019. One email reminder was sent to encourage participation. The survey examined the presence of visa-holding trainees at the respective program, familiarity with waiver programs and permanent resident status, and sponsorship opportunities for nephrology fellows on visas. The survey specifically inquired whether fellows held a J-1 (exchange visitor) visa or an H-1B (temporary worker) visa, 2 visas commonly held by trainees. PIVIO consisted of a total of 7 questions (Table 1; Fig 1; Item S1): 3 in the form of dichotomous yes or no responses (questions 1-3), 3 with an ordinal scale using a computer mouse–based caliper that ranked answers from 0 (least likely) to 100 (most likely), and 1 with a “select all that apply” response (question 7). Before starting the survey, each respondent provided consent for participation in the survey and dissemination of results.

Table 1.

Survey Responses for Questions 1 Through 6

| Questions With Dichotomous (yes or no) Responses | Response = Yes |

|---|---|

| 1. Do you currently have clinical/research fellows on J-1 or H-1B visas in your program? | 61 (82%) |

| 2. In the last 5 years, have you sponsored a waiver program for individuals on J-1 visas in the transition from trainee to faculty at your institution? | 36 (49%) |

| 3. In the last 5 years, have you sponsored individuals on H-1B visas for lawful permanent resident status (ie, “green card”) in the transition from trainee to faculty at your institution? | 47 (64%) |

| Questions using an ordinal scalea | Median score (25th-75th percentile) |

| 4. How knowledgeable are you about J-1 visa waiver programs and/or lawful permanent resident status? | 53 (40-78) |

| 5. How likely is your institution to sponsor a J-1 visa waiver program or sponsor an individual for lawful permanent resident status? | 50 (17-75) |

| 6-How limiting do you perceive a trainee's visa status to be for transition to practice?b | 53 (46-82) |

Ordinal scale using a computer mouse–based caliper that ranked the answers from 0 (least likely) to 100 (most likely).

All 74 participants responded to each question, except for question 6 (n = 73 responses).

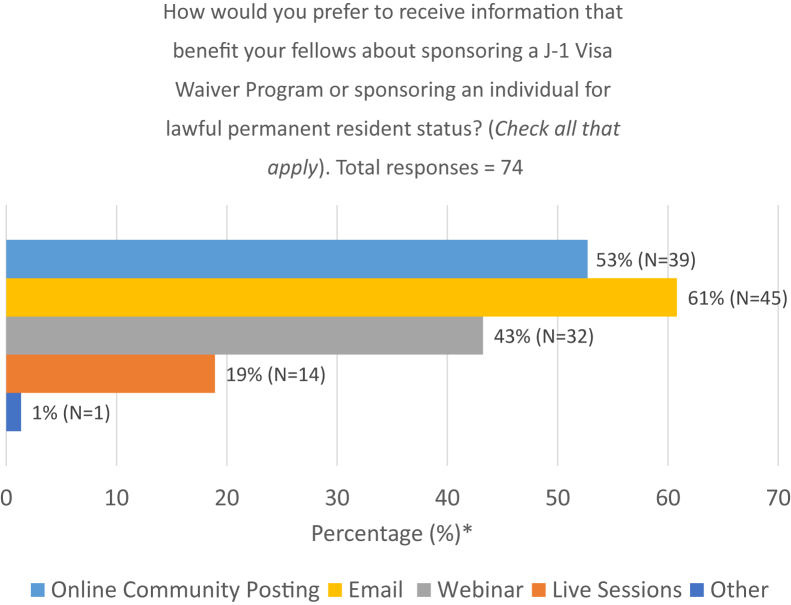

Figure 1.

Survey responses for question 7. ∗Percentage: number for each option divided by the total number of respondents (N = 74).

Among 457 division chiefs, program directors, and associate program directors, 74 anonymous replies were received (response rate, 16.2%). A total of 82% reported that their program had at least 1 fellow on a J-1 or H-1B visa, and 49% reported sponsoring a waiver program for individuals on a J-1 visa in the last 5 years, whereas 64% reported sponsoring individuals on an H-1B visa for lawful permanent resident status in the last 5 years (Table 1). Overall, respondents reported being somewhat knowledgeable (median score of 53, with 0 representing least knowledgeable and 100 representing most knowledgeable) about the J-1 visa waiver programs and/or lawful permanent resident status. Respondents believed that their institution was somewhat likely (median score of 50, with 0 representing least likely and 100 representing most likely) to sponsor a J-1 visa waiver program or sponsor an individual for lawful permanent resident status. Last, respondents believed that the visa status of trainees somewhat limited (median score of 53, with 0 representing least likely and 100 representing most likely) their transition to practice after fellowship (Table 1). Most respondents preferred email or online community posting to receive information related to sponsorship of J-1 waivers or lawful permanent resident status. Webinars and live educational sessions were also favored (Fig 1).

The survey results suggest that most programs have recently trained individuals on J-1 or H-1B visas, but only half have sponsored waiver programs for individuals on J-1 visas or lawful permanent residence status for individuals on H-1B visas. This may be due to inexperience with the immigration process itself, unfamiliarity with the available channels for sponsorship, or limited resources. Limitations of the survey include the low response rate and nondisclosure of institutional affiliation, which precludes definitive conclusions. Future examination of this immigration topic should include a more comprehensive assessment of current institutional practices and bridging of logistical gaps that may facilitate immigration processes for fellowship leaders, administrators, and non-US international medical graduate trainees. This is particularly important because nephrology fellowship leaders that participated in the survey disclosed interest in receiving further education in this area.

Recently, the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has ushered in additional anxieties and potential hurdles for international medical graduate physicians, including travel restrictions, visa sponsorship, and fluctuating immigration policies. It will be important to investigate how immigration changes have affected the nephrology community because the data could strengthen further advocacy efforts aimed at restructuring immigration policies. A mixed-methods approach may lend itself best for this purpose, specifically conducting interviews and/or focus groups with non-US international medical graduates, fellowship leaders, and immigration policy representatives to determine the most critical barriers to facilitate completion of mandatory immigration processes during and after training.

Finally, it is important to continue the dissemination of resources that highlight the journey of non-US international medical graduate trainees, such as recent work by Neyra et al4 in which they describe common exchange visitor and temporary worker visas and elucidate pathways of transition from training to practice. Professional mentorship initiatives and platforms such as that established by ASN5 are also key to expanding professional networks, sponsorships, and allyships. These continued efforts will need to be amplified and promoted by the field at large so as to maintain a cohesive, diverse, and equitable workforce that will best care for the growing patient population affected by kidney diseases.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Flor Alvarado, MD, MPH, Deidra C. Crews, MD, ScM, Cynthia Delgado, MD, and Javier A. Neyra, MD, MSCS.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: DCC, CD, JAN; data acquisition: FA, JAN; data analysis and interpretation: all authors; study supervision: DCC, JAN. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

Dr Alvarado is supported by grant 2 T32 DK 7732-26 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Dr Crews is supported in part by grant K24 HL148181 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, NIH. Dr Delgado’s contribution is the result of work supported with the resources and use of facilities at the San Francisco VA Medical Center. Dr Neyra is supported in part by NIDDK R56 DK126930 and P30 DK079337.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgements

Dr Delgado serves as chair, Dr Neyra is an active member, and Dr Alvarado is the current intern of the ASN Diversity and Inclusion Committee. The authors thank all members of the ASN Diversity and Inclusion Committee for their thoughtful feedback throughout the execution of this project, and particularly, Ms Katlyn Leight for her support and assistance with survey dissemination.

Peer Review

Received August 11, 2020. Evaluated by 1 external peer reviewer, with direct editorial input from the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form December 13, 2020.

Footnotes

Item S1. ASN Survey: Perceptions of International Medical Graduate Visa Issues and Opportunities

Supplementary Material

Item S1

References

- 1.ASN preliminary analysis released on AY 2020 nephrology match data. ASN Kidney News. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.kidneynews.org/careers/resources/asn-preliminary-analysis-released-on-ay-2020-nephrology-match-data

- 2.National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: Specialties Matching Service 2020 Appointment Year. National Resident Matching Program; 2020.

- 3.Pivert K., Boyle S., Chan L. ASN Alliance for Kidney Health; 2019. 2019 Nephrology Fellow Survey—Results and Insights. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neyra J.A., Tio M.C., Ferrè S. International medical graduates in nephrology: a guide for trainees and programs. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020;27(4):297–304. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2020.05.003. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engage in Mentoring. ASN Communities. Accessed October 25, 2020. https://community.asn-online.org/mentoring

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Item S1