Abstract

The Achilles tendon, while the strongest and largest tendon in the body, is frequently injured. Even after surgical repair, patients risk re-rupture and long-term deficits in function. Poly-N-acetyl glucosamine (sNAG) polymer has been shown to increase the rate of healing of venous leg ulcers, and use of this material improved tendon-to-bone healing in a rat model of rotator cuff injury. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the healing properties of liquid sNAG polymer suspension in a rat partial Achilles tear model. We hypothesized that repeated sNAG injections throughout healing would improve Achilles tendon healing as measured by improved mechanical properties and cellular morphology compared to controls. Results demonstrate that sNAG has a positive effect on rat Achilles tendon healing at three weeks after a full thickness, partial width injury. sNAG treatment led to increased quasistatic tendon stiffness, and increased tangent and secant stiffness throughout fatigue cycling protocols. Increased dynamic modulus also suggests improved viscoelastic properties with sNAG treatment. No differences were identified in histological properties. Importantly, use of this material did not have any negative effects on any measured parameter. These results support further study of this material as a minimally invasive treatment modality for tendon healing.

Keywords: animal model, biomechanical properties, orthopaedics, foot and ankle, injury

Introduction

The Achilles tendon, while the strongest and largest tendon in the body, is frequently injured. These injuries can range from microtraumatic tear-induced tendinopathy to debilitating full-thickness ruptures3. Because the Achilles plays a crucial role in ankle stability as well as both ankle and knee flexion, injuries to this tendon can significantly limit basic activities, and thereby quality of life. Unfortunately, there is not a consensus on specific treatment protocols for Achilles tendon tears, as there is data to support both conservative (non-operative) repair as well as more invasive surgical repair18. Even after surgical repair, patients risk re-rupture and typically have long-term deficits in function, with a low rate of return to pre-injury levels of activity1.

In an attempt to improve tendon repair, various forms of biological augmentation have been utilized, including platelet rich plasma, growth factors, and stem cell delivery20. Delivery methods for these therapeutic approaches vary, from scaffold-based treatments implanted during surgical treatment to the use of growth factor-coated sutures. Many of these methods are incompatible with non-operative treatment strategies, in which patients undergo a period of immobilization and rest followed by increased load bearing over time25. In this scenario, the addition of biological augmentation via minimally invasive delivery methods would be highly advantageous.

Poly-N-acetyl glucosamine (sNAG) polymer, derived from oceanic microalgae has been shown to increase the rate of healing of venous leg ulcers, with an 86% success rate clinically11. In a mouse model of cutaneous injury, application of this material decreased scarring and improved mechanical properties after healing; evidence suggests that these effects were due to alterations in immune cell activation13. Importantly, we have previously utilized this material in a rat model of rotator cuff injury and repair17. Application of a single dose of a thin sNAG membrane at the injury site increased tendon maximum load and maximum stress, and improved functional properties assessed using animal gait analysis. However, effects of the application of this material in a soft tissue tendon injury environment (as opposed to a rotator cuff tendon-to-bone detachment used in the previous study) have not yet been investigated. In order to test effects of this nanofiber material in a non-operative model of Achilles tendon injury, we utilized an injectable liquid formulation. This allowed for the delivery of sNAG via a series of injections throughout early healing. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the healing properties of unlabeled liquid sNAG polymer in a rat partial Achilles tear model. We hypothesized that sNAG injections would improve Achilles tendon healing as measured by improved mechanical properties and cellular morphology compared to controls.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

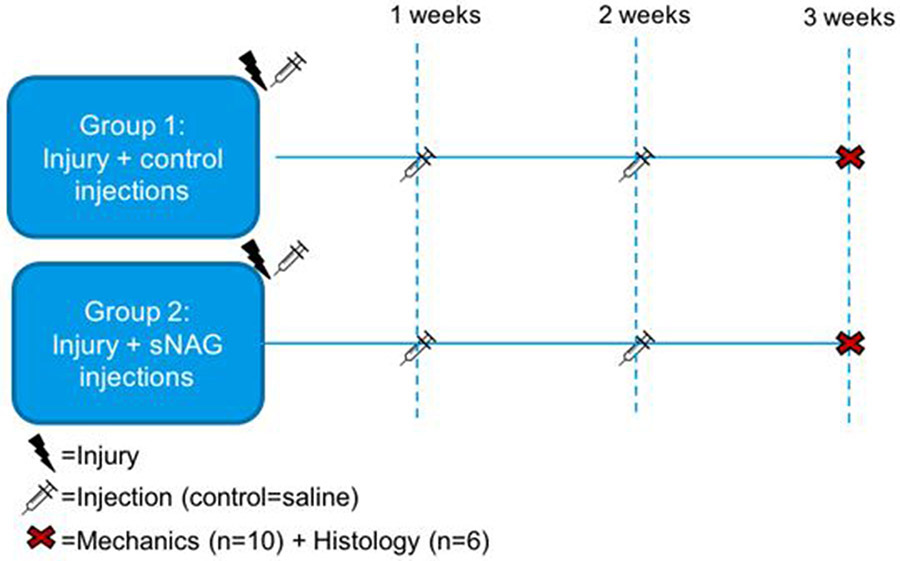

A total of 43 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (400-450g) were used in this University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved study. Animals were housed in a conventional facility in 12-hour light/dark cycles and were fed standard rat chow ad libitum. All animals underwent a partial-width, full thickness injury using a 1.5 mm biopsy punch through the right Achilles tendon9. In a pilot study, 9 animals received a single 10 μl injection of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled sNAG polymer liquid (20 mg/ml) at the time of injury, and were euthanized at 3, 7, and 14 days post-injury (n=3/time points) via CO2 inhalation.

For the primary study, after injury, the remaining animals were randomized into two groups, receiving an injection directly into the defect of either 10 μl of 0.9% saline (control group, n=16) or 10 μl of 20 mg/ml unlabeled sNAG polymer liquid (sNAG group, n=16). Animals were allowed normal cage activity after surgery, without immobilization. Our previous study suggests that short-term use of immobilization after injury in this model may interfere with the ability to measure effects of a treatment variable8. Animals received repeat saline or sNAG injections at the site of the injury through the skin at one and two weeks post-surgery. This study design is displayed in Figure 1. All animals were humanely euthanized three weeks after injury via CO2 inhalation.

Figure 1. Experimental study design.

Animals underwent a full-thickness, partial width Achilles tendon injury followed by injections of either saline (control group, n=16) or sNAG (n=16) at the time of injury. Percutaneous injections were repeated at one and two weeks post-injury. All animals were euthanized three weeks post-injury for tendon histological and mechanical assessments.

sNAG polymer (Talymed Suspension) was provided by Marine Polymer, Inc. The dosage used in this study was chosen to be an identical quantity of polymer as was utilized in the previous rotator cuff model17.

Injury and Treatment

Buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) was administered to all animals 30 minutes prior to surgery. Once rendered unconscious by inhalation of isoflurane, the right hind limb was cleared of hair and sterilized with betadine and alcohol scrubs. Under sterile surgical conditions, the Achilles tendon was surgically exposed by a medial 2 cm skin incision along the posterior side of the lower limb. All fascia was separated from the tendon. Surgical scissors were placed under the tendon for support while a 1.5mm biopsy punch was inserted into the center of the tendon. At this time, animals received either 10 μl of sNAG or saline injections directly into the defect and the surgical site was sutured closed. Animals recovered under a heat lamp and were allowed unrestricted cage activity. Buprenorphine injections (0.05 mg/kg) were administered every 6 to 10 hours for two additional days.

As noted above, all animals received intratendinous injections of either 10 μl sNAG or saline, using a 50 μl Hamilton syringe with a 23 gauge needle, immediately following surgically-induced injury. All animals also received two additional injections performed percutaneously into the injury site at one and two weeks post-surgery. These percutaneous injections were performed under anesthesia and in an aseptic environment, as described above.

Assessment of Polymer Longevity (Pilot)

For the pilot study, at the time of sacrifice, the Achilles-calcaneus complex was immediately harvested, fixed in 4% PFA, and decalcified with 10% EDTA. Tendon-bone complexes were bisected along the sagittal plane, and visualized with a Zeiss AxioZoom microscope, using the following filters: YFP for FITC labeled-sNAG, mRFP for background/autofluorescence, and bright field for tendon-bone structure. Composite images were created using the Zeiss ZenLite software.

Tendon Mechanical Testing

Immediately after sacrifice, rats (n=10/ group) were frozen at −20°C and later randomly selected for dissection and mechanical testing. The Achilles tendon and foot complex were dissected under a stereomicroscope to remove all soft tissue surrounding the tendon and bone and stain dots were applied to the tendon using Verhoeff’s stain for optical strain measurement. The following mechanical testing protocol has been previously described5,8. Briefly, tendon cross sectional area (CSA) was measured using a custom laser device4, then the calcaneus was potted in poly(methyl methacrylate). Once cured, the tendons were gripped with sandpaper and placed into a custom grip allowing for a 12 mm tendon gauge length. The potted tendon was immersed, in physiologic orientation, into an Instron Biopuls bath filled with 37°C phosphate-buffered saline, and attached to a testing frame Instron Electropuls E3000 using a 250N load cell. Tendons were subjected to a mechanical loading protocol consisting of: preconditioning, stress relaxation at 6% strain, dynamic frequency sweeps under displacement control from 0.1 to 10Hz, and fatigue cycling under load control (5 to 35 N) until specimen failure. The initial ramp to 35 N (fatigue cycle 1) is performed at 2% strain/second. Fatigue testing was performed at 2 Hz using a sinusoidal waveform. Previous publications provide more extensive details regarding this testing protocol5. Images for optical strain measures were captured, and the slope of the linear region of the stress-strain curve was quantified to calculate linear modulus as well as regional linear modulus for the tendon insertion (0-3 mm), tendon injury region (3-6 mm) and tendon musculotendinous junction (MTJ, 6-12 mm).

Histology

For experimental groups, at the time of sacrifice, the Achilles-calcaneus complex was immediately harvested and processed for histological analysis as previously described5,9,23 including quantitative collagen fiber organization analysis (n=6/experimental group). Samples were fixed in formalin, decalcified in Immunocal, and processed with paraffin. Each sample was sagitally sectioned at 7 μm and stained with hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E). Samples were imaged within the injury region using a polarizing light microscope, and collagen organization (measured as angular deviation of collagen alignment) was quantified using a custom MATLAB code. Three blinded graders semi-quantitatively assessed images (200x magnification taken at the injury site) for cell shape and cellularity (2 images per sample). Scoring was on a scale from 1 to 3 (1 for lower cell density and more spindle shaped cells, and 3 for higher cell density and more rounded cell shape) using grading scale created within the set of images taken for this study, as previously described24. Median scores were used for each image, and scores were averaged between images for each sample.

Statistical Analysis

Sample sizes were determined using a priori power analyses. No statistics were performed for the pilot study (qualitative analysis only). Statistical comparisons were made between the two experimental groups, control (saline) and sNAG. -Based on the study hypothesis that sNAG would improve tendon properties post-injury, one-tailed t-tests were used to compare quasistatic mechanics parameters and collagen fiber organization. Dynamic properties were compared with a two-way ANOVA for treatment and test frequency (0.1-10 Hz), while fatigue properties were compared with two-way ANOVA for treatment and percent fatigue life (5, 50, and 95%). Semi-quantitative histological comparisons were made using Mann-Whitney U tests. If significant for treatment, p-values are listed in the figure legend. Follow-up t-tests were conducted to compare between groups at test frequency or percent fatigue life; p-values of 0.1 or less are reported with a black horizontal bars on the graph (solid bars indicate significant differences (p<0.05) and hashed bars indicate trends (p<0.1). P-values for both significant and trend differences are noted in the results.

Results

Polymer Longevity

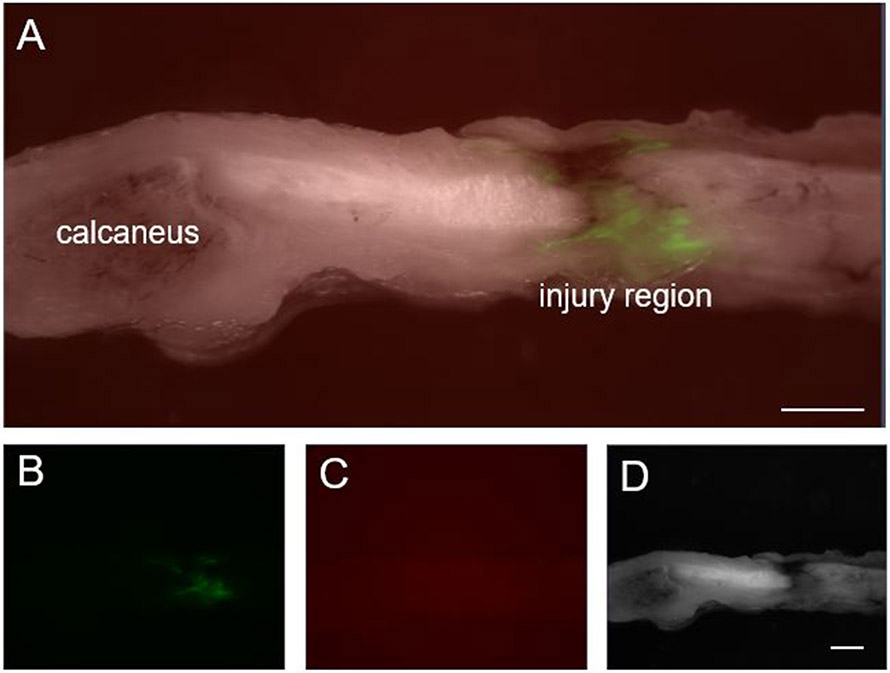

Qualitative assessment of the presence of FITC-labeled polymer demonstrated clear, positive signal primarily localized at the injury/injection, with some dispersion through the surrounding tendon region. This signal was similar for samples assessed at the 3 and 7 day time points, but by 14 days, signal intensity appeared to be diminished. Based on these findings, repeated injection of control or sNAG at 7 day intervals was determined for the experimental study design. A representative image depicting the presence of FITC-sNAG at the injury site 7 days post-injury is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. sNAG longevity at injury/injection site.

(A) Composite image of sagittal Achilles tendon 7 days after FITC-labeled sNAG injection following full-thickness, partial width Achilles tendon injury. Green signal indicates localization of FITC-labeled sNAG to the injury site. (B) FITC filter only. (C) mRFP filter only demonstrates lack of background or autoflourescent signal. (D) Bright field filter only. Scale bars: 1 mm.

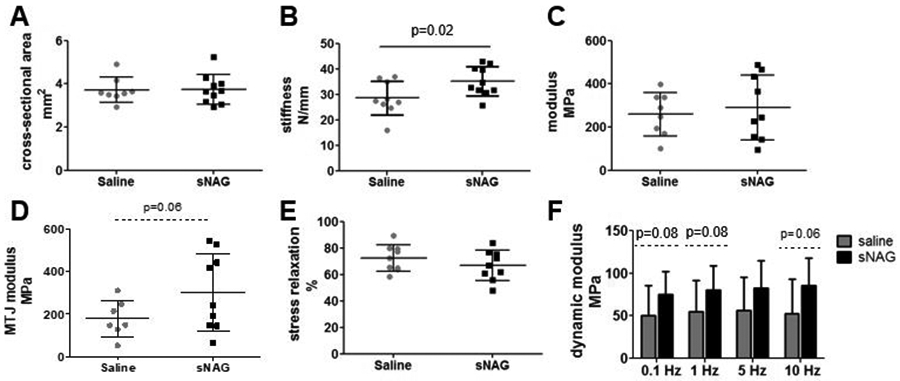

Tendon Mechanical Properties

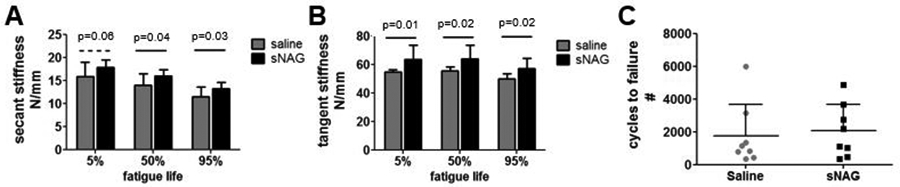

At three weeks after injury, there was no difference in tendon cross-sectional area (Fig 3A). Tendon stiffness was improved with sNAG treatment (Fig 3B, p=0.02), but tendon modulus measured across the entire tendon was not different between groups (Fig 3C). However, regional modulus was improved in the musculotendinous junction proximal to the injury site (Fig 3D, p=0.06). Viscoelastic testing demonstrated no difference in percent relaxation (Fig 3E). Dynamic modulus was increased with sNAG treatment across tested frequencies (Fig 3F, p=0.004), but tanδ, a measure of force dissipation, was not different (not shown). Fatigue properties were also improved with sNAG delivery after injury. Tendon secant stiffness (Fig. 4A; 5%, p=0.06; 50%; p=0.04; 95%, p=0.03) and tangent stiffness (Fig. 4B; 5%, p=0.01; 50%, p=0.02; 95%, p=0.02) were increased throughout fatigue life for sNAG-treated tendons compared to controls. There was no difference in cycles to failure (Fig. 4C), or other fatigue properties measured, including tangent modulus, tangent stiffness, hysteresis, and peak strain.

Figure 3. Quasistatic and viscoelastic mechanical properties.

(A) No differences were seen in cross-sectional area. (B) Tendons treated with sNAG were stiffer than control tendons. (C) No differences were seen in linear modulus. (D) Regional modulus measured at the musculotendinous junction (MTJ) was increased with sNAG treatment. (E) No differences were seen in percent relaxation. (E) Dynamic modulus measured across four frequencies was significantly different between treatment groups (p=0.004). Data shown as mean±SD.

Figure 4. Fatigue mechanical properties.

(A) Secant stiffness was increased for sNAG treated tendons across fatigue life. (B) Tangent stiffness was increased for sNAG treated tendons across fatigue life. (C) No differences were seen in number of cycles to failure. Data shown as mean+SD.

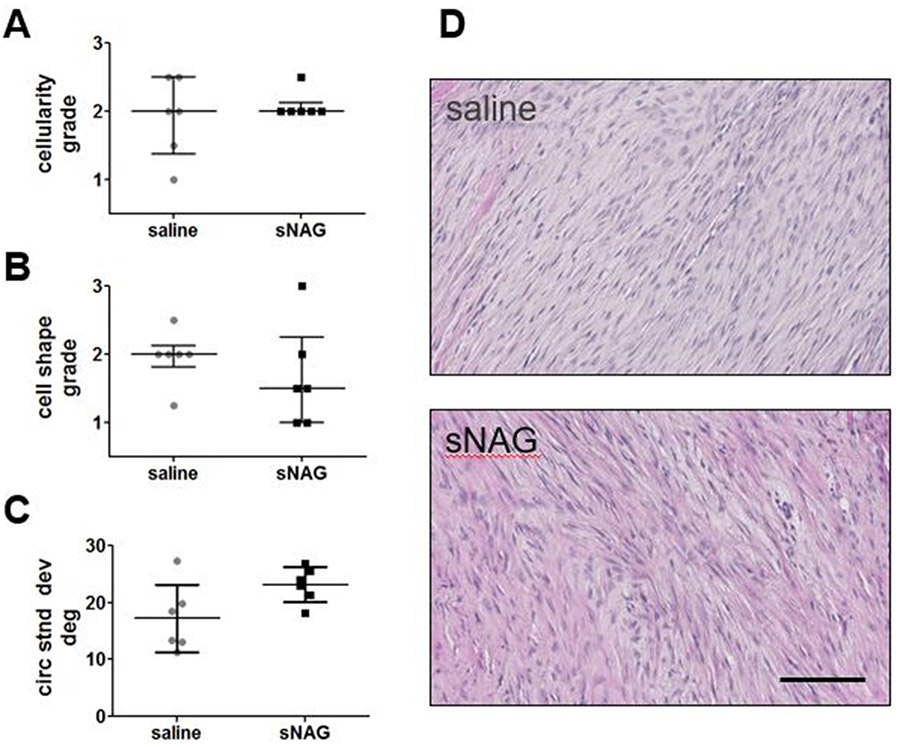

Histologic Observations

No differences were identified in cellularity (Fig. 5A) or cell shape (Fig. 5B) at the injury region. Collagen alignment measured in this region was also not different between groups (Fig. 5C). Representative images of the injury region for both groups are shown in Figure 5D.

Figure 5. Histological properties.

(A) No difference in cellularity at the site of injury was seen between groups (1=fewer cells, 3=more cells). (B) No difference in cell shape at the site of injury was seen between groups (1=more spindled cell shape, 3=more rounded cell shape). (C) No difference in collagen organization, as measured by standard deviation of alignment, was seen between groups. (D) Representative images of the injury site for saline treated (top) and sNAG treated (bottom) Achilles tendons. Data represented as median median±IQR in A and B, and as mean±SD in C. Scale bar in D: 100 μm.

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of repeated sNAG polymer application on tendon healing in a model of partial Achilles tendon injury treated conservatively (non-operatively). Although several parameters did not exhibit differences between treatment groups, several key results demonstrate that sNAG has a positive effect on rat Achilles tendon healing at three weeks after a full thickness, partial width injury. Quasistatic testing demonstrated increased tendon stiffness with sNAG treatment, and these improvements continued during fatigue cycling, as shown in increased tangent and secant stiffness across fatigue life. Although stiffness was increased by an average of 23% with sNAG treatment, tendons are still significantly less stiff than uninjured tendons (133 ± 26 N/mm, data from previous study)9. Increased dynamic modulus also suggests improved viscoelastic properties with sNAG treatment. For this parameter, sNAG improved tendon dynamic modulus by at least 50%, resulting in a return toward baseline uninjured dynamic modulus values (85.9± 29.5 MPa at 0.1 Hz, 92.5± 30.9 MPa at 1 Hz, 96.3± 31.8 MPa at 5 Hz, and 95.0± 32.3 MPa at 10 Hz)9. Importantly, use of this material did not have any negative effects on any measured parameter. Following our previous study demonstrating improved healing properties in a rat rotator cuff injury model17, data from this study further supports the use of sNAG polymer after musculoskeletal injuries.

sNAG polymer, a bio-active product isolated from microalgae, is currently FDA-approved for wound care, with applications including venous ulcers, pressure ulcers, burns, and abrasions. In vitro studies suggest that the mechanism of action of this product is through enhanced angiogenesis and increased granulation tissue formation19. While we can only speculate that this is a mechanism in action in our in vivo model, we plan to include vascular assessments in future studies utilizing sNAG. Although overall tissue quantity was not increased in this study (as measured by tendon cross-sectional area), tendon vascularity was not assessed. Together with immune cell modulation, another effect of sNAG identified in a wound-healing environment13, neo-vascularization has been identified as an important property of early healing12. These processes have been shown to play an important role in prohibiting the formation of ectopic ossification, which does occur at later time points in this injury model9. Further studies should be performed to specifically assess these healing properties. The basic histological assessments completed here did not detect significant differences in cell density, cell shape, or collagen organization at the site of the injury. Although these assays may not be robust enough to detect small differences in these parameters, these results suggest that the mechanisms behind improved mechanics are not related to cell density, cell morphology, or collagen alignment. In our previous sNAG study, we similarly did not detect differences in cell-specific histological properties, yet sNAG improved mechanical properties17.

In our previous study, we hypothesized that sNAG polymer was maintained at the delivery site (tendon-bone interface) for a significant period of time due to its impact on healing properties17. Data from the pilot study presented here (Figure 2), while qualitative, confirms that it is not immediately cleared from an injured tendon environment. This is not surprising, as this polymer has a positive charge capable of allowing strong adhesion to biological materials, which in turn promotes red blood cell aggregation and platelet activation16,21,22. Maintenance of the polymer within the site of delivery was consistent, and the time scale of clearance (over a two week period) supports translation of a periodic delivery protocol for clinical use during tendon healing processes.

A number of other biologically active materials are used as “injection therapies” in a similar manner to treat Achilles tendon injuries, which are classified along with a number of other therapeutic approaches (cryotherapy, ultrasound, splints, etc) as non-surgical, conservative approaches10. Autologous blood or platelet-rich plasma can be isolated from a patient and injected directly into the injury site. However, there is no evidence to support that this treatment strategy leads to better outcomes than a placebo treatment14. This may be due to variability in patient-derived materials due to significant diversity in age, co-morbidities, etc. within the patient population15. Therefore, use of a consistent, biologically active, off-the-shelf material that does not necessitate secondary patient procedures or preparation provides significant benefits over current treatment paradigms.

This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the injury model of a conservatively treated partial tear was created surgically and immobilization was not implemented. We acknowledge that this acute surgical model does not replicate the chronic injury clinical scenario. Several studies have attempted to induce an overuse injury in the rat Achilles via treadmill running, but results have been inconsistent6,7. Our injury model has been well-characterized and provides an easily repeatable injury with consistent outcomes9. Additionally, use of immobilization/remobilization during such a short healing period (three weeks) has been shown to be detrimental to healing at this time point specifically, and could therefore interfere with therapeutic outcomes9. Previous studies suggest that this material may mitigate pain after rotator cuff injury17. Functional testing such as gait assessment would be valuable, potentially expanding the use of this material as a less invasive treatment for painful Achilles tendonitis2. Additionally, dosage studies and number of repeated sNAG injections may optimize the use of sNAG for soft tissue tendon healing. Finally, studies to elucidate the mechanism of action for the changes identified are important.

This study evaluated the mechanical and histological properties of injured Achilles tendons treated with and without repeated injections of a sNAG polymer suspension. Overall, sNAG had positive effects on tendon stiffness measured three weeks after injury. Further, no negative effects were identified in any property assessed in this study. These results support further study of this material as a minimally invasive treatment modality for tendon healing and tendinopathy.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Marine Polymer Technologies, Inc. and NIH/NIAMS supported Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders Grant (5P30AR069619). We thank Stephanie Weiss for assistance with surgical procedures, and Peter Chan for assistance with histology.

Grant support:

Funding provided by Marine Polymer Technologies, Inc., and the NIH/NIAMS supported Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders Grant (5P30AR069619).

Study approved by:

University of Pennsylvania IACUC #806378

References

- 1.Barfod KW, Bencke J, Lauridsen HB, Ban I, Ebskov L, and Troelsen A. Nonoperative dynamic treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture: the influence of early weight-bearing on clinical outcome: a blinded, randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 96(18):1497–1503, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barg A, and Ludwig T. Surgical Strategies for the Treatment of Insertional Achilles Tendinopathy. Foot Ankle Clin. 24(3):533–559, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egger AC, and Berkowitz MJ. Achilles tendon injuries. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med 10:72–80, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Favata M Thesis Dissertation. Scarless healing in the fetus: implications and strategies for postnatal tendon repair. University of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freedman BR, Gordon JA, Bhatt PR, Pardes AM, Thomas SJ, Sarver JJ, Riggin CN, Tucker JJ, Williams AW, Zanes RC, Hast MW, Farber DC, Silbernagel KG, and Soslowsky LJ. Nonsurgical treatment and early return to activity leads to improved Achilles tendon fatigue mechanics and functional outcomes during early healing in an animal model. J Orthop Res 34:2172–2180, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glazebrook MA, Wright JR Jr, Langman M, Stanish WD, and Lee JM. Histological analysis of achilles tendons in an overuse rat model. J Orthop Res. 26:840–6, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinemeier KM, Skovgaard D, Bayer ML, Qvortrup K, Kjaer A, Kjaer M, Magnusson SP, and Kongsgaard M. Uphill running improves rat Achilles tendon tissue mechanical properties and alters gene expression without inducing pathological changes. J Appl Physiol (1985). 113:827–36, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huegel J, Boorman-Padgett JF, A Nuss C, Raja HA, Chan PY, Kuntz AF, Waldorff EI, Zhang N, Ryaby JT, and Soslowsky LJ. Effects of Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Therapy on Rat Achilles Tendon Healing. J Orthop Res. 38(1):70–81, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huegel J, Boorman-Padgett JF, Nuss CA, Minnig MCC, Chan PY, Kuntz AF, Waldorff EI, Zhang N, Ryaby JT, and Soslowsky LJ. Quantitative comparison of three rat models of Achilles tendon injury: A multidisciplinary approach. J Biomech. 88:194–200, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kearney RS, Parsons N, Metcalfe D, Costa ML. Injection therapies for Achilles tendinopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 26;(5):CD010960, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelechi TJ, Mueller M, Hankin CS, Bronstone A, Samies J, and Bonham PA. A randomized, investigator-blinded, controlled pilot study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a poly-N-acetyl glucosamine-derived membrane material in patients with venous leg ulcers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 66(6):e209–e215, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kokubu S, Inaki R, Hoshi K, and Hikita A. Adipose-derived stem cells improve tendon repair and prevent ectopic ossification in tendinopathy by inhibiting inflammation and inducing neovascularization in the early stage of tendon healing. Regen Ther. 14:103–110, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindner HB, Felmly LM, Demcheva M, Seth A, Norris R, Bradshaw AD, Vournakis J, Muise-Helmericks RC. pGlcNAc Nanofiber Treatment of Cutaneous Wounds Stimulate Increased Tensile Strength and Reduced Scarring via Activation of Akt1. PLoS ONE. 10(5):e0127876, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu CJ, Yu KL, Bai JB, Tian DH, and Liu GL. Platelet-rich plasma injection for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinopathy: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 98(16):e15278, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Chowaniec DM, Cote MP, Romeo AA, Bradley JP, Arciero RA, and Beitzel K. Platelet-rich plasma differs according to preparation method and human variability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 94(4):308–316, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morykwas MJ, Thornton JW, and Bartlett RH. Zeta potential of synthetic and biological skin substitutes: effects on initial adherence. Plast. Reconstr. Surg 79(5):732–739,1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nuss CA, Huegel J, Boorman-Padgett JF, Choi DS, Weiss SN, Vournakis J, and Soslowsky LJ. Poly-N-Acetyl Glucosamine (sNAG) Enhances Early Rotator Cuff Tendon Healing in a Rat Model. Ann Biomed Eng. 45(12):2826–2836, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park SH, Lee HS, Young KW, and Seo SG. Treatment of Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture. Clin Orthop Surg. 12(1):1–8, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scherer S, Pietramaggiori G, Matthews J, Perry S, Assmann A, Carothers A, Demcheva M, Muise-Helmericks RC, Seth A, Vournakis JN, Valeri RC, Fischer TH, Hechtman HB, and Orgill DP. Ann Surg. 250(2):322–30, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapiro E, Grande D, and Drakos M. Biologics in Achilles tendon healing and repair: a review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 8(1):9–17, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thatte HS, Zagarins SE, Amiji M, and Khuri SF. Poly-N-acetyl glucosamine-mediated red blood cell interactions. J. Trauma 57:S7–S12, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thatte HS, Zagarins SE, Khuri SF, and Fischer TH. Mechanisms of poly-N-acetyl glucosamine polymermediated hemostasis: platelet interactions. J. Trauma 57:S13–S21, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomopoulos S, Williams GR, Gimbel JA, Favata M, and Soslowsky LJ. Variation of biomechanical, structural, and compositional properties along the tendon to bone insertion site. J Orthop Res 21:413–419, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tucker JJ, Cirone JM, Morris TR, Nuss CA, Huegel J, Waldorff EI, Zhang N, Ryaby JT, and Soslowsky LJ. Pulsed electromagnetic field therapy improves tendon-to-bone healing in a rat rotator cuff repair model. J Orthop Res. 35(4):902–909, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang X, Meng H, Quan Q, Peng J, Lu S, Wang A. Management of acute Achilles tendon ruptures: A review. Bone Joint Res. 7(10):561–569, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]