Abstract

Problem

COVID-19 guidance from professional and health organisations created uncertainty leading to professional and personal stress impacting on midwives providing continuity of care in New Zealand (NZ). The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in massive amounts of international and national information and guidance. This guidance was often conflicting and not suited to New Zealand midwifery.

Aim

To examine and map the national and international guidance and information provided to midwifery regarding COVID-19 and foreground learnt lessons for future similar crises.

Methods

A systematic scoping review informed by Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage framework. A range of sources from grey and empirical literature was identified and 257 sources included.

Findings

Four categories were identified and discussed: (1) guidance for provision of maternity care in the community; (2) guidance for provision of primary labour and birth care; (3) Guidance for midwifery care to women/wāhine with confirmed/suspected COVID-19 infection, including screening processes and management of neonates of infected women/wāhine (4) Guidance for midwives on protecting self and own families and whānau (extended family) from COVID-19 exposure.

Conclusion

Guidance was mainly targeted and tailored for hospital-based services. This was at odds with the NZ context, where primary continuity of care underpins practice. It is evident that those providing continuity of care constantly needed to navigate an evolving situation to mitigate interruptions and restrictions to midwifery care, often without fully knowing the personal risk to themselves and their own families. A key message is the need for a single source of evidence-based guidance, regularly updated and timestamped to show where advice changes over time.

Keywords: COVID-19, Midwives, New Zealand, Lockdown, Guidance, Practice

Statement of significance.

Problem or issue

COVID-19 practice guidance for midwives created uncertainty leading to professional and personal stress impacting on midwives providing continuity of care in New Zealand.

What is already known

Continuity of care improves outcomes and is desired by women. COVID-19 guidance for New Zealand midwives from international and national sources was not consistent in the initial stages of the pandemic.

What this paper adds

This review illustrates how inconsistency in practice guidance impacts on midwifery during a quickly changing pandemic practice context. It is imperative to be prepared for future pandemics to help ensure quality safe midwifery continuity of care continues. Policy makers must consider midwives and their families when issuing practice guidance.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), created a fast-moving and changing public health crisis globally [1]. This was evident within maternity and midwifery services [2,3] and impacted women [4] around the world. New Zealand adopted a quick decisive early approach to COVID-19 with the intention of eradicating the virus within the borders [5,6]. The subsequent national health emergency resulting in shutdown of all services except essential ones, placed frontline health workers including midwives in a challenging and dynamic situation which they had never encountered. As the situation unfolded much uncertainty continued. Despite uncertainty, midwives across New Zealand needed to grapple with major practice situations for which they had never been prepared [7]. The fluidity of the government-coordinated risk management advice created uncertainty and ambiguity in a workforce under stress [8,9], that has also been reflected in the media coverage of maternity experiences in New Zealand [7]. The ever-changing guidance and myriad sources of information coming from the global networks and national professional bodies and New Zealand Ministry of Health (MoH) added to a situation which has been reported anecdotally as adding stress to an already demanding practice reality [10]. Dealing with sudden changes to how they work with women and whānau during pregnancy, birth and postnatally, especially in the community, required unprecedented innovation and adaptation by midwives in all settings. This scoping review reports on how this guidance came from multiple sources over a four month period and illustrates the complexity of the practice reality of the New Zealand midwifery workforce who continued to work in ways that ensured, as much as possible, a preservation of the New Zealand model of maternity care. This model of care is built upon a foundation of relational continuity, partnership and safety of the women/wāhine, families and whānau and communities. The balance between keeping themselves safe, their own families and whānau safe whilst continuing to work at the frontline of maternity services is highlighted.

Background

The New Zealand maternity system provides free maternity care for all eligible women/wāhine. Women/wāhine who choose the additional services of a private obstetrician will pay for this service. Nevertheless, every birthing woman in NZ will have a midwife involved in her care. Women may choose their Lead Maternity Carer (LMC), who can be a midwife, General Practitioner (GP) or obstetrician, who is accountable and responsible for all the care. Around 95% of women/wāhine in NZ have a midwife LMC. Continuity of care is a standard for maternity care in NZ [11]. This continuity of care model is available to women/wāhine and their families and whānau in the community and in secondary and tertiary facilities [12]. New Zealand’s unique model of care continued despite the disruption to health services following the announcement in March 2020 of a State of Emergency and full lockdown, which mandated social distancing and self-isolation [13]. Midwives employed in hospitals and birth centres (known as core midwives) continued to provide care to women across the whole spectrum of care in a rapidly-changing practice environment. This includes midwifery care for primary (women with uncomplicated pregnancies), secondary (women who require input from obstetric services but not a transfer of care) and tertiary maternity (women with pregnancy complications requiring transfer of care). The complexity of delivering midwifery care during COVID-19 represents a defining moment in New Zealand’s maternity services because the situation has highlighted the need to be resilient and to address existing professional concerns. Due to the collective uncertainty within the profession, convening on online web conferencing and social media platforms was ubiquitous. New Zealand midwives, including the authors, engaged with online communication to discuss practice concerns. Midwives working in the primary setting engaged extensively in online platforms due to the need to communicate with each other about clinical practice concerns. Through participation in online forums the authors noted the concerns midwives raised, and formulated several questions:

-

1

What is the best way to provide midwifery and ensure continuity of care and partnership with women/wāhine and families and whānau during a pandemic?

-

2

How do midwives keep the families and whānau they serve safe during COVID-19 pandemic?

-

3

How do midwives keep themselves safe during COVID-19 pandemic?

-

4

How do midwives keep their own families and whānau safe during COVID-19 pandemic?

These questions prompted a larger study investigating midwives within the context of COVID-19 New Zealand of which this scoping review is a part. The aim of this scoping review is to address these questions by: examining and mapping the national and international guidance and information provided to midwifery and maternity health care providers regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, illustrating the complexity for frontline NZ midwives, and to foreground learnt lessons for future similar crises. The regional uniqueness of this scoping review highlights the contextual reality of midwifery continuity of carer when confronted by an array of changing pandemic guidance over time that posed restrictions on movement, social distancing and evolving requirements for protective measures as evidence emerged. Table 1 provides New Zealand specific terms and acronyms. This scoping review contributes to a larger three stage study that aims to inform future practice arrangements and guidance provision for the ongoing COVID-19 situation and future pandemics. A search for similar scoping review protocols in progress or completed was undertaken. To the authors knowledge no other scoping review on this topic within the New Zealand context has been undertaken. This review protocol has been registered and published [14].

Table 1.

Regional and domain specific terms and acronyms.

| DHB | District Health Boards |

| LMC | Lead Maternity Carer. Self-employed, can be a midwife, GP with a diploma in obstetrics or obstetrician. Most LMCs are midwives practising in the community, with a focus on primary birthing, |

| Core midwives | Employed midwives practising in primary, secondary and tertiary units. |

| MOH | Ministry of Health |

| NZCOM | New Zealand College of Midwives |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) |

| RANZCOG | Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists |

| RCOG | Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists |

Methods

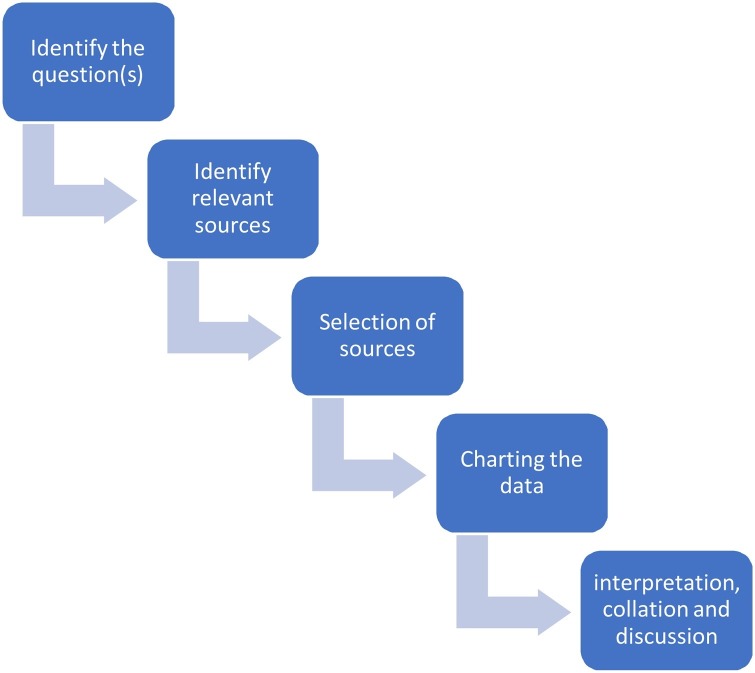

The method of this scoping review was informed by the five-stage framework by Arksey and O’Malley [15]; a framework further enhanced to increase transparency of the process by Levac et al. [16]. Scoping reviews are becoming a popular form of evidence synthesis to address research questions through gathering of data over multiple sources [17]. A Scoping review can be used to inform policy and practice although the focus is not necessarily related to questions of feasibility, appropriateness, or effectiveness; instead the purpose is concerned with identifying and clarifying research priorities and questions by providing background and contextual information [18]. A scoping review framework described by Arksy and O’Malley was suitable because it led to synthesised evidence that enabled identification of policy changes pertinent to midwifery practice in the early stages of the pandemic. Sourcing an array of sources over a critical timeline resulted in a trustworthy evidence synthesis that has proven to be an invaluable adjunct to the larger COVID-19 NZ midwifery research project still underway. The review started with an a priori protocol developed before commencing the review and registered with the Open Science Framework, 2020 [19] and published [14] (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

The five-stage framework adapted from Arksey and O’Malley [15].

Stage one: identifying the question(s)

Stage one clarifies the research question and purpose of the review. The purpose is to examine and illustrate the complexity for frontline NZ midwives during COVID-19 lockdown contributing to a larger three stage study that highlights lessons learnt for future similar crises by informing future practice arrangements and guidance provision. The overarching question of this review is ‘What guidance and information has been provided and available to maternity health care providers in the period of the 1st Nov 2019 to the 30th June 2020 regarding the COVID-19?’ Although the novel coronavirus was first formally announced 31st December there was some information emerging prior to the formal announcement and we wanted to capture all these early sources. During the authors initial exploration of the media coverage and, social media platforms [7] four distinct categories of the phenomenon of interest emerged, these became the four categories which are elaborated later.

-

1

Guidance for provision of maternity care visits in the community (antenatal and postnatal) during the COVID-19 pandemic;

-

2

Guidance for provision of primary labour and birth care (excluding births by caesarean section) including place of birth, labour support, protective equipment for normal birth;

-

3

Guidance for provision of midwifery care to women/wāhine with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infection, including screening processes and management of neonates of infected women/wāhine and

-

4

Guidance for midwives on protecting self and own families and whānau from exposure to COVID-19 during the pandemic.

Stage two: identifying relevant sources

Stage two identified relevant sources whilst balancing achievability with the breadth and comprehensiveness of the review, whilst maintaining alignment with the studies’ purpose and questions. Only text and artefacts written in English and found through the robust systematic search strategy were included. Any sources with ethical issues were excluded. The search included research literature, official guidance and information published globally for maternity health care providers during the COVID-19. This report only includes identified sources that are peer-reviewed academic research articles, peer-reviewed or substantiated report literature (e.g., policy documents, reports, brief reports and fact sheets that guide practice for maternity health care providers, government reports, DHB communications, professional bodies and fact sheets that guided practice for NZ midwives). Where deemed appropriate for inclusion opinion and editorial texts were used if verifiable easily accessible sources.

Two genres of sources were included: international and national. International sources are included because the international guidance begun to emerge prior to national sources which were informed by the emerging global responses and understanding of the pandemic. The first Covid-19 symptoms were verified on 8th December 2019 with the WHO reporting an outbreak on the 30th December 2019 [20]. Before bespoke New Zealand guidance for practice emerged, New Zealand midwives, their associations and the Ministry of Health worked through information and guidance emerging globally from late 2019. Therefore, the time limits for the international data were from Nov 2019 until 30th June 2020 in order to capture all advice. The NZ national data includes sources 1st March to 30th June 2020.

A search strategy together with a research librarian was developed. The search strategy followed a three-step process suggested by the Joanna Briggs Institute [21]. Step one: The initial search was performed in the databases CINAHL, MEDLINE and on official websites of WHO and NZ government. This was followed by an analysis of the text words in the title and abstract of retrieved papers, and of the index terms which informed the key terms to be used in step two.

Keyword set

For scientific articles, keywords were: (midwif* OR matern* OR pregnan* OR perinatal) AND (guideline* OR instruction* OR rule* OR guidance) AND (“COVID-19” OR COVID-19 OR coronavirus) (midwife OR maternity OR pregnant OR pregnancy OR perinatal) AND (guidelines OR instructions OR rules OR guidance) AND (“COVID-19” OR COVID-19 OR coronavirus).

For national or international guidance from government and government agencies, we used Google to find information from government websites. Keywords were:

(midwives OR maternity) (guidelines OR instructions OR rules OR guidance) “COVID-19” site: govt.nz (midwives OR maternity) (guidelines OR instructions OR rules OR guidance) “COVID-19” site: who.int

In Step two: All identified keywords and index terms were used to search across all included databases and official websites (CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed and Google scholar, WHO, ICM, UNISECO, CDC, Professional bodies-NZ College of Midwives, Ministry of Health and District Health Boards (DHBs). The same searches were re-run every two weeks until 30th June to capture the unfolding nature of the phenomenon of interest. In Step three: the reference list of all identified reports and articles were searched to capture additional studies/sources. Other sources were included and explored as the scoping process progressed.

Stage three: source selection

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The selection of sources was an iterative process involving all the authors of the review. Inclusion criteria was based on clearly identifiable populations, concepts and contexts (PCC) [21]. Table 2 illustrates how the PCC acronym was applied.

Table 2.

Application of the PCC research tool.

| Population | Midwives referred to in sources of guidance and information and related to the objectives of the study. In this study, registration, regulation and association of midwifery and be in one the 37 countries OECD membership are considered. Relevant papers to be highlighted if they are outside the OECD and included. |

| Concept | Phenomenon of Interest – Guidance/information for midwives during COVID-19. |

| Context | The COVID-19 pandemic in New Zealand between 1st March to 30th June 2020. |

| The COVID-19 pandemic in global between 1st Nov 2019 and 30th June 2020. |

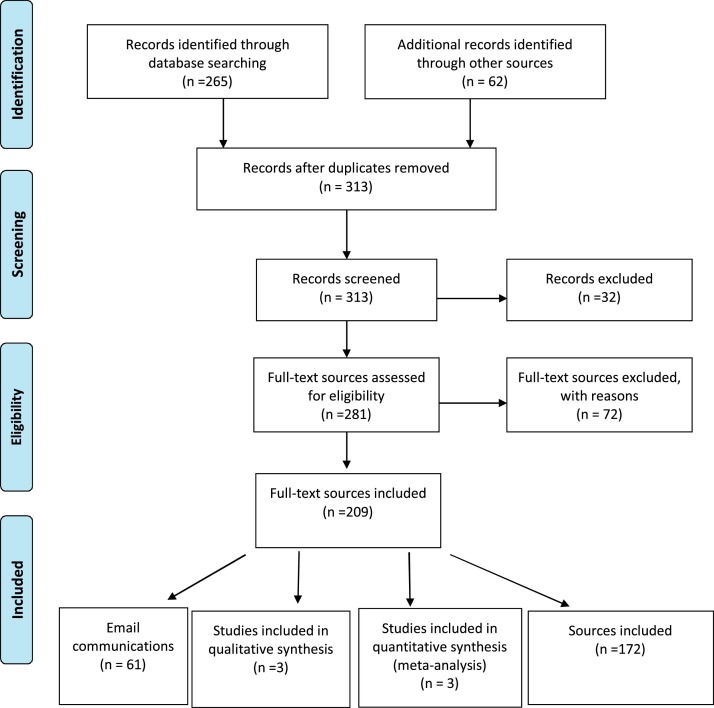

Source selection was performed in several steps. First, author independently screened all titles and abstracts to determine eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. Only items that included guidance on the above four categories of the domain were included in the review. Some items were relevant to more than one sub-area. The titles were screened and labelled as “included”, “excluded” and “uncertain”. All articles labelled “included” and “uncertain” were considered in the second step. In the second step, each research team member was assigned one of the four categories and reviewed the relevant sources. A second reviewer was assigned to each category to verify inclusion. In case of disagreements, a third reviewer was involved to reach consensus. This assured a robust and trustworthy review process. A formal assessment of the quality of the literature was not performed in this scoping review because the aim was to present a map of what is already done and what evidence exists rather than finding the best available evidence. The following PRISMA flow chart shows the inclusion and exclusion process during identification of relevant sources (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

A PRISMA Flow Diagram (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009) (p.9).

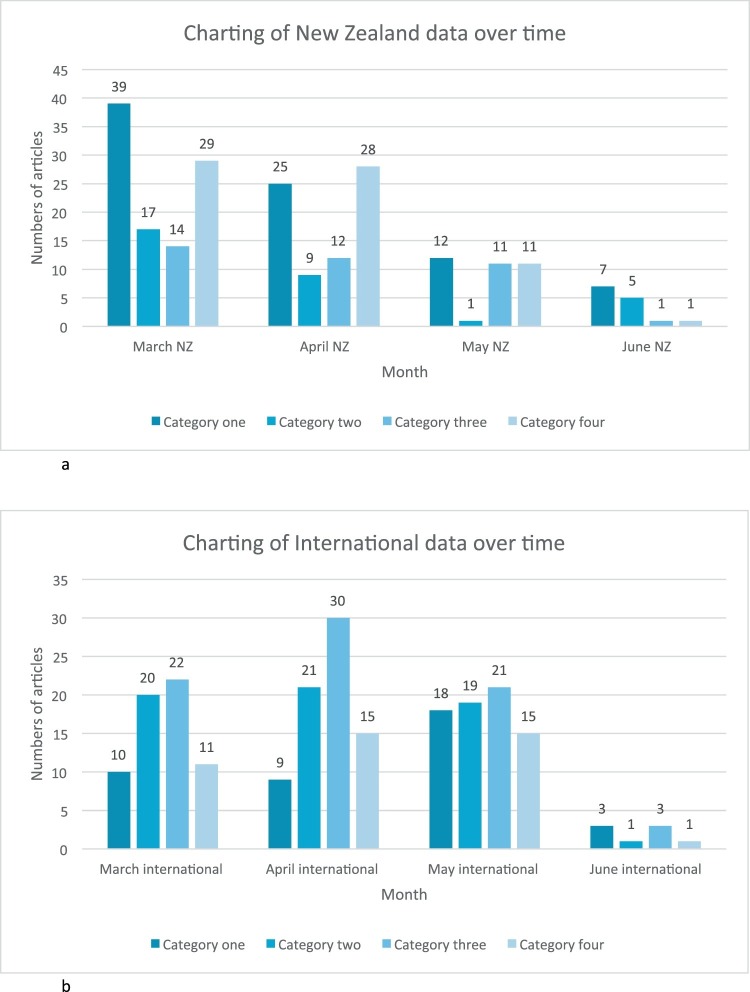

Stage four: charting the data

Stage four involved a systematic search and charting of the evidence led to a summary of the thematic analysis that addressed the four categories illustrating the changing guidance and dynamic changing nature of such guidance over time. A series of charting tables are presented to record the key information and data extracted from the included sources explicitly showing the chronological quality of the phenomenon of interest across the 4 categories:

-

•

Category one: provision of maternity care visits in the community (antenatal and postnatal).

-

•

Category two: provision of primary labour and birth care (excluding births by caesarean section), including place of birth, labour support, protective equipment for normal birth.

-

•

Category three: provision of midwifery care to women/wāhine with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infection, including screening processes and management of neonates/pēpi of infected women/wāhine.

-

•

Category four: guidance for midwives on protecting self and own families/whānau from exposure to COVID-19.

The following tables provide examples to illustrate the data charting and analysis. The tables provide a descriptive summary charting the results linking the review questions and the four categories and how the passage of time influenced type, style and frequency of guidance to midwives. The full data set in excel format is in the supplementary materials (link). Many of the guidance communications in the early phase of the pandemic were via emails from DHBs and professional and regulatory bodies to their members and staff. Therefore, emails were included when they provided explicit guidance to the midwifery workforce. Although these sources are not easily accessed online the research team deemed them significant to include and are available on request to the primary corresponding author. Inclusion of the emails was part of the original scoping review protocol, but it was necessary to include only those emails pertinent to the review when containing guidance not available in other sources. Not all emails were nationally distributed and were regionally specific to DHBs. All DHB email communication followed MoH verified guidance and content differences between DHB email communications was only in how guidance was regionally applied (Tables 3a, 3b, and 4 ) (Fig. 3 ).

Table 3a.

Example of details of the New Zealand sources.

| Source code | Title | Date of public availability | Author | Type of source | Main category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NZ153 | Aotearoa New Zealand Midwife Issue 97 [22] | 1/06/2020 | NZCOM | Professional magazine | Category one |

| NZ154 | Access to this season’s flu immunisation starts this week – message from the MOH [23] | 9/06/2020 | MOH | Official information | Category four |

| NZ133 | Breastfeeding advice for women/wāhine who have a confirmed or probable case of COVID-19 [24] | 1/05/2020 | MOH | Official guidance | Category three |

Table 3b.

Example of the details of the international sources.

| Source code | Title | Date of public availability | Author | Type of source | Main Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter01 | Expert consensus for managing pregnant women and neonates born [25] | 01/4/2020 | Chen, D. J. | Research literature | Category two and three |

| Inter02 | 2020-03-25-COVID-19-antenatal-screening [26] | 23/03/2020 | RCOG | Official guidance | Category three |

| Inter03 | Successful containment of COVID-19 outbreak in a large maternity and perinatal center while continuing clinical service [27] | 20/04/2020 | Pediatr Allergy Immunol | Research article | Category four |

Table 4.

Charting of data showing how some guidance changed and emerged over time.

| Category | Guidance | Source of guidance | March 2020 | April 2020 | May 2020 | June 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four | Mask wearing | New Zealand and international | Do not endorse wearing mask at this point in the outbreak [28] | In level 3 and 4 wear appropriate PPE [29,30] | Maintain the use of PPE as appropriate [31,32] | No guidance located |

| One, two, three, four | Face to face contact | New Zealand | Strictly limiting visiting Explore tele/virtual contacts and support for women/wāhine and families and whānau [33] |

Minimise physical contact time with their clients during this period through using telephone and/or video calling [34] | Begin to move back to normal in-person appointments [35] | Midwifery visits may now be undertaken face to face and at usual intervals [36] |

| One | Other visitors to home | New Zealand | No visitors [33] | No visitors [30] | Under alert level 2, visiting is allowed, but a limit on the number of visitors or the length of time they can stay [37] | Follow the limitations of social distancing requirements [36] |

| Three | Breast feeding of women/wāhine with suspected or confirmed infection | New Zealand and international | a. In China and Singapore, recommended no breast feeding, neonates isolated for 14 days, not to be given mothers expressed milk [25,38]. b. In Europe and Canada, recommended breastfeed. Expressed milk can be fed to infants unpasteurised [39,40]. |

In New Zealand, women/wāhine can choose to breastfeed. If too unwell to breastfeed women/wāhine can express. If self-isolating breastfeeding women/wāhine should keep baby with them so that breastfeeding can continue [41]. | Internationally, limited data suggest COVID-19 not transmitted via breastmilk. But separation of covid infected mothers and infants still advised in many locations. | No guidance located |

Fig. 3.

(a) Charting of New Zealand data over time. (b) Charting of international data over time.

Stage five: findings and discussion

Stage five involves interpreting, collating, summarizing and reporting the results of the selected evidence and identifying the overarching themes and presentation of implications. This was undertaken by the research team in an iterative process until consensus on the thematic results and implications of the scoping review were agreed. As a scoping review the aim was not to synthesize or analytically map the results/outcomes of included sources of evidence or include a formal thematic analysis because this would be beyond the limits of a scoping review. As such, outcomes comprised a descriptive summary of the findings in relation to the purpose of the review. The following discussion presents a descriptive summary of results linked to the four categories which classified interventions, strategies and practice behaviours and how these were modified over time.

Category one: provision of maternity care visits in the community

As the pandemic rapidly swept across the world in early 2020 resultant global regional lockdowns occurred. Category one guidance soared in March 2020 in the New Zealand context when the severest of lockdown across the entire country was initiated by central government. The provision of community-based midwifery visits for antenatal and postnatal care episodes was severely disrupted. Although mask wearing and other forms of PPE were not mandatory or advised in March there was direction provided on limiting home visits. In one DHB the advice included exploring alternative ways of doing clinical care such as tele/virtual contacts when continuing primary support for women/wāhine and whānau — this genre of guidance created changes in practice across the country. Further restrictions on other visitors being around at the time of visits was recommended which had social and cultural implications especially in cultures that favour more collective ways of living where there is greater fluidity between households. By April 2020 the advice changed to promotion of more PPE and mask wearing and guidance from the NZCOM was to keep any face-to-face visits to less than 15 min for essential hands-on clinical care when unavoidable. By May 2020 when the initial community transmission had been contained the MoH instructed community midwives that it was safe to move back to normal in-person appointments; this advice was then endorsed in June 2020 by The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG). What is evident in this survey of guidance is the rapidly changing advice from different agencies on what was deemed safe and appropriate community midwifery practices. For community midwives, just keeping up on what level care provision was safe and expected was a significant demand. The face-to-face connection with women/wāhine and families and whānau by midwives remained a high priority and core value to the NZ midwifery ethos of care yet was infused with ongoing uncertainty and resource concerns (e.g. access to PPE in the community setting). Although NZ midwives have responsibility to provide care up until six weeks postnatal this normally entails a transition to well child providers, such as Plunket (Well-child) services. However, Plunket services withheld all community face-to-face visits leaving midwives as the sole primary maternal and infant health care provider in many areas/regions.

Category two: provision of primary labour and birth care

Amidst the plethora of information and guidance on the management and provision of care during the pandemic coming from myriad national and international sources comes the very salient quote, “We are all learning as we proceed” [42]. The international information and guidance were prolific and ahead of that coming from national sources, but this likely led to a more measured response from within NZ. Much of the international advice to the maternity system during February and March 2020 was targeted at the provision of care to women and babies within the hospital system where PPE was recommended for care providers in the hospital setting, and visitors, including support people during labour, were restricted. Generally, international advice in the early stages was that COVID-19 was not in itself an indication for expedited delivery and each woman must be individually assessed [43]. There was general support for women with uncomplicated pregnancies, and negative for COVID-19, to birth in the community including at home. This advice was positioned around alleviating the burden on the hospital system [44].

Other management strategies included use of CTG monitoring during labour due to the possible risk of fetal tachycardia and potential for fetal compromise should the woman be infectious [45]. There were no contraindications for epidural for pain relief [46]. Some authors posited the potential risk of vertical transmission, however, over time this concern was shown to have no basis in evidence [47]. Initially there was mixed advice regarding breastfeeding by COVID-19 positive women with some advising total separation for mother and baby following birth and feeding via expressed breast milk. The UNFPA later advocated for continued direct breastfeeding and uninterrupted care between the mother and baby [43]. Mask use during breastfeeding was encouraged.

The practice of water immersion and water birth was the focus of mixed opinion over the early months. In some contexts, e.g. United Kingdom (UK) the demand of pandemic on the midwifery workforce meant fewer midwives were available to staff primary units and attend births at home. In the absence of any real evidence, the default position was to forbid its use for women with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 [48]. However, over time the theoretical risks proposed were considered not valid for non-COVID-19 negative women, and women and midwives should use an individualised approach and emerging evidence to inform their practice [49].

The early information and guidance from within NZ came mainly from the MOH, the NZCOM, the Midwifery Council of New Zealand (MCNZ) DHBs. There was strong support for women and midwives to consider community-based birth including home birth. Women elected home birth at times due to the restriction in visitors and support people in the hospitals. For midwives this meant planning and logistics to ensure available equipment and resources for home births, such as birth pools, birthing packs and emergency equipment. Many DHBs provided home birth equipment to facilitate this choice and some welcomed the opportunity to birth at home [7]. Both the professional and regulatory bodies for midwives in NZ acknowledged midwifery autonomy, responsibility and informed decision-making in partnership with women, with MCNZ advising midwives to use their professional judgement and evidence and to be guided by the Code of Conduct [50]. The information regarding PPE availability and usage in the community was very mixed and supplies were slow to reach the community with many midwives providing their own resources.

Category three: midwifery care to women/wāhine with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infection, including screening processes and management of neonates of infected women/wāhine

This was a highly contested category in the literature both internationally and nationally. Items from international literature included primarily consensus or position statements, case-series, technical briefs, special editorials and rapid-reviews. From May 2020 guidance emerged from a broader range of professional bodies and the first Systematic Reviews of previously published articles appeared. Authors of these publications generally emphasised the paucity of research evidence to guide maternity care providers and advised caution with use of the guidance provided.

International recommendations varied widely by country. For example, pregnant women in the United Kingdom (UK) with COVID-19 were recommended to defer appointments for antenatal assessment and ultrasound scans for 14 days [51]. If the appointment could not safely be deferred women should attend alone and wear a mask. One source from China advised all Covid positive women be admitted to dedicated COVID-19 maternity facilities and quarantined [52].

Internationally vaginal birth was considered the preferred mode unless otherwise indicated [53]. Following the emergence of evidence that COVID-19 infection during pregnancy was associated with adverse fetal effects, continuous fetal monitoring was recommended during labour. Most advised that a birth partner labour/support person may be present, although they should be free of COVID-19 symptoms and not accompany the woman to the postnatal ward. The safety of labour and birth in water became contentious once COVID-19 was detected in faecal matter. For example, women with COVID-19 in an April 2020 UK clinical briefing were precluded from using a birth pool in areas where this option existed [49].

The area of greatest discrepancy in the international sources was between guidance documents and recommendations around immediate care of the neonate and initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding for COVID-19 women. The World Health Organisation recommended delayed cord clamping, skin-to-skin, rooming-in and breastfeeding for women with COVID-19 an approach that was generally supported in the UK and Europe. In stark contrast to this, many organisations recommended immediate cutting of the cord and complete separation of the mother and infant for 14 days, with the infant to be formula fed or else fed expressed breastmilk by a non-Covid infected nurse, notably in China, Singapore and the USA. When separation of mothers and babies was recommended clinicians were advised to be aware this was likely to influence bonding and on women’s psychological wellbeing and bonding [54]. Such discordant and changeable international clinical advice only exacerbated an already uncertain challenging situation [45].

In New Zealand, guidance for Midwives on how to manage women and babies with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 primarily emanated from regional DHBs, professional bodies such as NZCOM, RANZCOG and the MOH. DHB policy and guidance primarily consisted of re-iterating MoH guidance, operationalised for the local situation.

Guidance promulgated during March 2020 and April 2020 emphasised the fact that the impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy was presently unknown and there appeared to be a greater focus on recommendations for screening and PPE use by health care providers than on clinical care of women with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. Recommendations from RANZCOG emphasised that all women were entitled to high-quality maternity care, including those with COVID-19 infection [55]. In terms of screening and entry to maternity services, women were advised to communicate with the maternity service prior to visits so that staff could ensure appropriate infection control measures were taken (single-room, PPE) when seeing women with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection. Non-urgent scans for COVID-19 positive women were recommended to be deferred [51].

For labour and birth, women with COVID-19 were advised not to birth at home or in a primary birthing units and care was to be overseen by obstetric teams at DHBs due to risk of respiratory sequelae and later risk of compromised fetus [56]. Vaginal birth was communicated to be the preferred option for women with COVID-19 unless otherwise indicated. Delayed cord clamping was not contraindicated and following birth, skin-to-skin, rooming-in and breastfeeding were recommended if the woman’s clinical condition allowed. This advice remained consistent throughout the included time-period of the review. The MoH provided recommendations for care of pregnant women in isolation and emphasised that it was the responsibility of DHBs to provide PPE for community-based midwives. Women were recommended to continue breastfeeding and practice ‘respiratory hygiene’ i.e. wearing a facemask during feeding, coughing into the elbow and washing hands in-between baby-cares.

By May 2020, new iterations of earlier guidance became available often including more specific recommendations, for example, advice that use of a birth pool is not recommended for COVID-19 positive women, although Entonox and epidural were acceptable (NZCOM). While there was no evidence of vertical transmission of COVID-19 at this time, reports had emerged of an association between COVID-19 infection during pregnancy and preterm birth. This was communicated widely, shifting the emphasis from infection control to ensuring appropriate care of women. Information about re-lactation for women who had ceased breastfeeding due to COVID-19 illness was also circulated.

Postnatal home visiting was advised for COVID-19 positive women, according to clinical need e.g. to perform metabolic screening, weigh infant at day 7 and breastfeeding support, with the midwife using full PPE. Time spent in physical assessment was expected to be kept to a minimum and postnatal care was to be provided by telephone where face-to-face assessment was deemed not essential. In summary, guidance for care of women with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection was reasonably consistent and in-keeping with guidance from the WHO. Although the reality for NZ Midwives was that the National response to the pandemic was so successful that only a handful of maternal COVID-10 cases were ever recorded. The MoH provided clear and regularly updated guidance which then formed the basis of other advice from professional organisations.

Given the rapidly changing situation during a pandemic, there are benefits to a clearly communicated and centralised approach with minimisation of multiple iterations of the same advice. In terms of potential improvements to dissemination of health professional guidance in future pandemics, a serialised approach to the release of guidance documents such as clearly named monthly bulletins could assist clinicians in understanding which information was the most up-to-date. In summary, multiple and contradictory guidance regarding the care of infected women and infants proliferated during the time-period reviewed. Internationally, expert opinion appeared to take precedence over emerging evidence with little regard for potential harm of unsupported practices such as separation of mothers and babies at birth.

Category four: guidance for midwives on protecting self and own families/whānau from COVID-19 exposure

New Zealand based advice for how health professionals needed to protect themselves during the COVID-19 pandemic emerged from DHBs [57] and the MoH [56]. The advice centred around the need to use PPE in various clinical circumstances. The guidelines were based on international guidance and followed evidence on infection control and prevention to prevent or limit transmission of COVID-19 in healthcare settings. Initial guidelines stated that clarification was sought in relation to labour and birthing and that a further update would be provided. In other words, specific advice for midwives to protect themselves and their whānau were slow to arrive.

Other guidance came primarily through DHBs, for example, distribution of PPE, when to use it and videos of how to don and doff it [57]. The advice from the DHBs and the Ministry of Health available in March, did not recognise that at least 50% of midwives in Aotearoa work in the community. Guidance for community midwives started to come through the NZCOM, who themselves were navigating advice from the MoH, DHBs and international sources. In a March 16th announcement, the NZCOM published on its website that “The College is working on detailed advice for midwives, midwifery care and advice for women and whānau relating to COVID-19. We will be updating information regularly on our website and Facebook page.” NZCOM continued to provide updates through these sources for midwives to protect themselves around when to use PPE, how to access PPE, and how to conduct antenatal, labour and birth and postnatal visits.

In April 2020, the Ministry of Health released guidance for community-based midwives which included screening women prior to visiting them, providing care via tele means when possible, and advice re maternity care to those in self isolation due to exposure to COVID-19, and providing midwifery care to those who have COVID-19 [56]. This guidance also stated times when midwives must not go to work.

The first published guidance for midwives by Wilson et al., provided an overview of important considerations for supporting the emotional, mental and physical health needs of maternity care providers [58]. The authors suggested that cooperation, planning and adequate availability of PPE was critical. They also highlighted that emotional and psychological support needed to be available throughout the response to prevent stress and burnout. Despite this caution we found no sources which provided advice regarding midwife’s protection of their whānau when they arrived home from work with regards to removing their clothing or showering for example. In summary advice re protection of midwives focused on facility-based midwives initially. Once advice for community midwives emerged, that advice focussed on screening women for risk of Covid, and when and where to use PPE.

Conclusion

This scoping review examined, and mapped guidance and information, regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, provided to maternity health care providers in Aotearoa New Zealand over the period 1st Nov 2019 to 30th June 2020. The purpose was to examine and illustrate the complexity for frontline NZ midwives during COVID-19 lockdown. The review illuminated how this fast moving and ever-changing global health crisis impacted maternity care provision and providers. Guidance and information were, in the main, targeted and tailored for hospital-based services due to an understanding that hospital services would become overwhelmed with numbers of infected people.

In the NZ context, where continuity of care (and carer) underpins the model of care, there was ambiguity and uncertainty for midwives providing primary maternity care in the community. The level of uncertainty regarding safety provoked by the shifting guidance added further responsibility onto an already busy professional group. By examining the local guidance, it is evident that New Zealand midwives, especially those providing continuity of care across community and maternity facilities, constantly needed to navigate the evolving difficult circumstances to mitigate interruptions and restrictions to midwifery care; often without fully knowing the personal risk to themselves and their own families.

A key message to emerge from the scoping review is the need for a sole source of evidence-based guidance and information, regularly updated and timestamped to show where advice changes over time, that informs practice both in the hospital system and in the community. Whilst all were learning as the pandemic proceeded, this review revealed how maternity services and midwives rapidly adapted to a new way of working. These lessons will inform future pandemic planning.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this review are its systematic and robust process based on an a priori protocol. The outcomes of the review directly inform the context of New Zealand midwives in the COVID-19. The outcomes are provided in real time, dynamic lived through phenomenon. Limitations to the review include the types of sources available and that no grading or rating of the quality of evidence was provided. Other relevant sources of information may have been omitted due to unavailability of sources either in review process or still being completed due to the dynamic real time nature of the phenomenon of interest of this review. However, all sources included were dependent on the nature and quality of available sources as they ‘became’ accessible and therefore implications for practice were uncertain in a dynamic changing landscape throughout the time of this review. In terms of transferability the review has limited global practice implications. Conversely the strength of this single country foci highlighting the effects of COVID-19 on midwifery services in NZ where continuity of carer is the foundation of good care, shedding light on how this model can be sustained during a pandemic.

Implications for future research

In the maternity context, continuity of care has been shown to make a positive difference to outcomes for women and babies. Further research on how continuity of care is maintained during a global pandemic, and an examination of maternal and neonatal outcomes during the pandemic, is needed. As well, research exploring the impact of COVID-19 guidance on the provision of culturally appropriate care would inform future pandemic planning. Changes made during the pandemic included the use of tele/virtual care for women and babies antenatally and postnatally. Research should be conducted to examine and compare outcomes that might include how did deferring ultrasound scanning impact the diagnosis of SGA and did that have any correlation to outcomes for babies. Other key maternity outcomes such as neonatal weight gain, breastfeeding success, rates of infection can be included.

Implications for practice, education, and policy

This implications for practice and education are to have a plan in place for how midwives, both in facilities and in the community, practice safely to protect women, whānau and themselves during a pandemic (or epidemic). This includes attention to increased midwifery workloads. For example, the NZ MOH acknowledged the increased anxiety that women would be feeling, and recommended midwives maintain telephone support for women. While a valuable recommendation, funding to support this additional demand on community midwives was slow to come. Education packages on how to adapt antenatal, labour, birth and postnatal care for delivery during a pandemic is needed. Midwives also need more education in infection control including when and how to use PPE and other infection control measures. Equally important is education in self-care to prevent stress and burnout during a pandemic or other natural disaster. For policy makers the recommendation is a centralised approach to promulgation of recommendations during a pandemic to ensure ongoing high-quality maternity care during a pandemic. Any policy to be developed during a pandemic should be consensus-based, pragmatic and include consideration of avoidance of harm to both midwives and the communities they work for.

Author contributions

All co-authors have assisted in the each of the literature review stages, the conception of the review and writing of this article. All co-authors have reviewed the final version submitted for review and agree to submission.

Ethical approval

None declared.

Funding sources

Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences funding at AUT University was obtained for focused COVID-19 related work and used to employ a research assistant for this review. No other funding associated with the writing of this scoping review.

Clinical trial registry and registration number

Not applicable. However, scoping review protocol published: Zhao, Y., Maude, R., Bradford, B. F., & Crowther, S. (2020 July 10,). New Zealand maternity and midwifery services responses to COVID-19. Retrieved from osf.io/akg8h.

Declaration of competing interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Hartley D.M., Perencevich E.N. Public health interventions for COVID-19: emerging evidence and implications for an evolving public health crisis. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1908–1909. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy P.A. Midwifery in the time of COVID-19. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2020;65(3):299–300. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.13121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Connell M., Crowther S., Ravaldi C., Homer C. Midwives in a pandemic: a call for solidarity and compassion. Women Birth. 2020;33(3):205–206. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim E. 2020. COVID-19 BRIEF: Impact on Women and Girls. (Accessed 10 August 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jefferies S., French N., Gilkison C., et al. COVID-19 in New Zealand and the impact of the national response: a descriptive epidemiological study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(11):e612–e623. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30225-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robert A. Lessons from New Zealand’s COVID-19 outbreak response. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(11):e569–e570. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30237-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowther S., Maude R., Bradford B., et al. When maintaining relationships and social connectivity matter: the case of New Zealand midwives and COVID-19. Front. Sociol. 2021;6(43) doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.614017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Writes E. Spinoff; 2020. Covid-19 has Only Made it Harder to be a Midwife. (Accessed 5 May 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 9.NZCOM . Midwife Aotearoa; New Zealand: 2020. Special Covid-19 Online Edition. (Accessed June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaskey T. Stuff; 2020. Coronavirus: ‘Scary and Uncertain Time’ for Mothers and Midwives’. 13/04/20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.MoH . In: New Zealand Maternity Standards: A Set of Standards to Guide the Planning, Funding and Monitoring of Maternity Services by the Ministry of Health and District Health Boards. Health Mo, editor. Ministry of Health; Wellington: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grigg C.P., Tracy S.K. New Zealand’s unique maternity system. Women Birth. 2013;26(1):e59–e64. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MoH . 2020. COVID-19 (novel coronavirus)https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus . (Accessed 20 August 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Y., Maude R., Bradford B.F., Crowther S. 2020. New Zealand Maternity and Midwifery Services Responses to Covid-19. Retrieved from osf.io/akg8h. July 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arksey H., O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010;5(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollock D., Davies E.L., Peters M.D., et al. Undertaking a scoping review: a practical guide for nursing and midwifery students, clinicians, researchers, and academics. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021;77(4):2102–2113. doi: 10.1111/jan.14743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munn Z., Peters M.D., Stern C., Tufanaru C., McArthur A., Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018;18(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Open Science Framework . 2020. New Zealand Maternity and Midwifery Services and the Covid-19 Response: A Systematic Scoping Review.https://osf.io/7us65/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Joanna Briggs Institute . The Joanna Briggs Institute; Australia: 2015. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 edition/Supplement. [Google Scholar]

- 22.New Zealand College of Midwives . Midwife Aotearoa; New Zealand: 2020. The Magazine of the New Zealand College of Midwives. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministry of Health . 2020. Access to This Season’s Flu Immunisation Starts This Week — Message From the MOH.https://www.midwife.org.nz/midwives/covid-19/access-to-this-seasons-flu-immunisation-starts-this-week-message-from-the-moh/ . (Accessed 9 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Health . 2020. Breastfeeding Advice for Women Who Have a Confirmed or Probable Case of COVID-19. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-information-specific-audiences/covid-19-information-parents/breastfeeding-advice-women-who-have-confirmed-or-probable-case-covid-19 (Accessed 9 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen D.J., Yang H.X., Cao Y., Cheng W.W., Duan T., Guan X.M. Expert consensus for managing pregnant women and neonates born to mothers with suspected or confirmed novel coronavirus (COVID-19) infection. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020;149(2):130–136. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists . Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists; London: 2020. Guidance for Antenatal Screening and Ultrasound in Pregnancy in the Evolving Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kabesch M., Roth S., Brandstetter S., et al. Successful containment of Covid-19 outbreak in a large maternity and perinatal center while continuing clinical service. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1111/pai.13265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hutt Valley District Health Board, Capital & Coast District Health Board . Hutt Valley District Health Board and Capital & Coast District Health Board; New Zealand: 2020. Letter to Colleagues about Masks. [Google Scholar]

- 29.New Zealand College of Midwives. Guidance for frequency of contacts for community midwifery carre for women/wahine and babies/pepi during alert level 4. 2020.

- 30.New Zealand College of Midwives. Guidance for frequency of contacts for community midwifery care and COVID-19 risk reduction. 2020.

- 31.Lambelet V., Vouga M., Pomar L., et al. SARS-CoV-2 in the context of past coronaviruses epidemics: consideration for prenatal care. Prenat. Diagn. 2020;40(13):1641–1654. doi: 10.1002/pd.5759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ortiz E.I., Herrera E., Torre A.D.L. Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in pregnancy. Colomb. Médica. 2020;51(2) doi: 10.25100/cm.v51i2.4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Counties Manukau District Health . Counties Manukau District Health; New Zealand: 2020. Women’s Health Communication Revisiting Policy. [Google Scholar]

- 34.New Zealand College of Midwives . New Zealand College of Midwives; New Zealand, Chirstchurch: 2020. COVID-19 Alert Levels 3 & 4 Information for midwives: 24 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ministry of Health . 2020. Covid-19 Information for Community-based Midwives at Alert Level 2.health.govt.nz/covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- 36.The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . 2020. RANZCOG Updated Advice for the Care of Pregnant Women.https://ranzcog.edu.au/news/updated-advice-for-the-care-of-pregnant-women2020 [Google Scholar]

- 37.New Zealand College of Midwives. COVID-19 Alert level 2 Information for Pregnant Women and Whānau: updated 20 May 2020.

- 38.Chua M.S.Q., Lee J.C.S., Sulaiman S., Tan H.K. From the frontline of COVID-19 — how prepared are we as obstetricians: a commentary. BJOG. 2020;127:786–788. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.CAPWHN . Canadian Association of Perinatal and Women’s Health Nurses; 2020. COVID-19_Suggestions For the Care of the Perinatal Population. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davanzo R., Moro G., Sandri F., Agosti M., Moretti C., Mosca F. Breastfeeding and coronavirus disease-2019: ad interim indications of the Italian Society of Neonatology endorsed by the Union of European Neonatal & Perinatal Societies. Matern. Child Nutr. 2020 doi: 10.1111/mcn.13010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Pregnancy: A Guide for Resource-limited Environments.ranzcog.edu.au/COVID-19-limited-resources2020 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Capanna F., Haydar A., McCarey C., et al. Preparing an obstetric unit in the heart of the epidemic strike of COVID-19: quick reorganization tips. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1749258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.UNFPA . In: Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Preparedness and Response — UNFPA Technical Briefs V March 23_2020. UNFPA, editor. UNFPA; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carmichael A., Dillon E., Hamil T., et al. Washington State Midwifery COVID-19 in collaboration with the Washington State Midwifery COVID-19 Response Coalition 31/3/2020; Washington, US: 2020. MAWS’ Interim Guidelines for Community-based Midwives during the COVID-19 Pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liang H., Acharya G. Novel corona virus disease (COVID-19) in pregnancy: what clinical recommendations to follow? Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020;99(4):439–442. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen D., Yang H., Cao Y., et al. Expert consensus for managing pregnant women and neonates born to mothers with suspected or confirmed novel coronavirus (COVID-19) infection. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020;149(2):130–136. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verma S., Lumba R., Lighter J.L., et al. Neonatal intensive care unit preparedness for the Novel Coronavirus Disease-2019 pandemic: A New York City hospital perspective. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care. 2020;50(4) doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2020.100795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poon L.C., Yang H., Kapur A., et al. Global interim guidance on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) during pregnancy and puerperium from FIGO and allied partners: information for healthcare professionals. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020;149(3):273–286. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.RCM . Royal College of Midwives; London: 2020. RCM Clinical Briefing: Waterbirth — COVID-19. 23rd April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 50.MCNZ . MCNZ; Wellington: 2010. Midwifery Council of New Zealand Code of Conduct. [Google Scholar]

- 51.RCOG Guidance for antenatal screening and ultrasound in pregnancy in the evolving coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. R. Coll. Obstetr. Gynaecol. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang S.-s., Zhou X., Lin X.-g., et al. Experience of clinical management for pregnant women and newborns with novel coronavirus pneumonia in Tongji Hospital, China. Curr. Med. Sci. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11596-020-2174-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mullins E., Evans D., Viner R., O’Brien P., Morris E. Coronavirus in pregnancy and delivery: rapid review. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;55(5):586–592. doi: 10.1002/uog.22014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chua M.S.Q., Lee J.C.S., Sulaiman S., Tan H.K. From the frontline of COVID-19—how prepared are we as obstetricians? A commentary. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020;127(7):786–788. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.RANZCOG . The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2020. Updated Advice for the Care of Pregnant Women. [Google Scholar]

- 56.MoH . Ministry of Health; Werllington: 2020. Covid-19 Information for Community-based Midwives at Alert Level 2. [Google Scholar]

- 57.CCDHB & HCCDHB . Hutt Valley District Health Board and Capital & Coast District Health Board; Wellington: 2020. Letter to Colleagues about Masks. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson A.N., Ravaldi C., Scoullar M.J., et al. Caring for the carers: ensuring the provision of quality maternity care during a global pandemic. Women Birth. 2021;34(3):206–209. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]