Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic imposed major changes on daily-life routine worldwide. To the best of our knowledge, no study quantified the changes on moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and sedentary behaviors (SB) and its correlates in Brazilians. This study aimed to (i) evaluate the changes (pre versus during pandemic) in time spent in MVPA and SB in self-isolating Brazilians during the COVID-19 pandemic, and (ii) to explore correlates.

Methods

A cross-sectional, retrospective, self-report online web survey, evaluating the time spent in MVPA and SB pre and during the COVID-19 pandemic in self-isolating people in Brazil. Sociodemographic, behavioral, and clinical measures, and time in self-isolation were also obtained. Changes in MVPA and SB and their correlates were explored using generalized estimating equations (GEE). Models were adjusted for covariates.

Results

A total of 877 participants (72.7% women, 53.7% young adults [18–34 years]) were included. Overall, participants reported a 59.7% reduction (95% CI 35.6–82.2) in time spent on MVPA during the pandemic, equivalent to 64.28 (95% CI 36.06–83.33) minutes per day. Time spent in SB increased 42.0% (95% CI 31.7–52.5), corresponding to an increase of 152.3 (95% CI 111.9–192.7) minutes per day. Greater reductions in MVPA and increases in SB were seen in younger adults, those not married, those employed, and those with a self-reported previous diagnosis of a mental disorder.

Conclusions

People in self-isolation significantly reduced MVPA levels and increased SB. Public health strategies are needed to mitigate the impact of self-isolation on MVPA and SB.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11332-021-00788-x.

Keywords: Physical activity, Sedentary behavior, COVID-19, Pandemic

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the spread of the severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has infected more than 13 million people in more than 200 countries around the world resulting in nearly 570 thousand deaths on the 14th of July 2020 according to the World Health Organization (WHO)[1]. As a response to reduce the virus spread, the WHO recommended national governments to adopt non-pharmacological strategies based on social and physical distancing, such as lockdown, quarantine, and self-isolation.

In Brazil, the epidemiological report number 05 of the Ministry of Health has recommended the adoption of social distancing measures, including self-isolation in areas with community transmission [2]. When self-isolating, people were advised to stay at home, and only go out in public for essential activities, such as going to the supermarket, to the pharmacy, or to use essential services, such as medical assistance. All other non-essential services, including gyms, parks, stadiums, and other places where people exercised were closed.

Self-isolation measures impose a drastic and sudden disruption of daily-life routine, resulting in limited physical and social mobility, and fewer opportunities to be active [3]. Moreover, the emotional burden [4, 5] of the pandemic likely resulted in additional barriers to remain focused and motivated to be and/or stay physically active, potentially reducing the time spent in physical activity (PA), defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that result in energy expenditure [6]. The negative impact of the pandemic and self-isolation measures on PA levels, both on light PA and moderate to vigorous PA (MVPA), defined as any activities that result in energy expenditure above 3 metabolic equivalents (METs) [7] noted in many countries including Australia [8, 9], Canada [10], Croatia [11], France [12], Italy [13], Spain [14], the UK [15, 16], and the USA [17–19]. However, some moderating factors on PA changes in this period were identified. For example, age [13, 15], sex [14], and the presence of chronic physical diseases or mental disorders moderated the pandemic impact on PA levels [15]. Further, increases in time spent in sedentary behavior (SB), defined as any waking behavior characterized by an energy expenditure ≤ 1.5 METs, while in a sitting, reclining or lying posture [20], were noted during the pandemic in the US [18, 19], France and Sweden [21], and Spain [14]. In Spain, sex moderated the increase in time spent in SB [14].

To the best of our knowledge, no study has evaluated how the COVID-19 pandemic changed PA and SB during self-isolating Brazilians. The present study aimed (i) to examine the changes (pre versus during COVID-19 pandemic) on PA and SB in self-isolating Brazilians, and (ii) to evaluate whether sociodemographic (sex, age, ethnicity, marital status, employment, monthly household income), behavioral (smoking, current alcohol consumption), clinical (presence of chronic physical diseases or mental disorders), and contextual factors (i.e., number of days of self-isolation) moderated these changes.

Methods

This paper presents pre-planned interim analysis of data from a cross-sectional study. Data collection was performed through an online survey (www.qualtrics.com). The study was launched on 11 April 2020 and data collection continued until 05 May. The study was approved by the Federal University of Santa Maria Research Ethics Committee and by the National Commission of Ethics in Research [CONEP] (30244620.1.0000.5346).

Participants and recruitment

Participants were recruited through social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter), and by distributing an invitation to participate through existing researcher networks. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Brazilians adults (18–65 years), (2) currently residing in Brazil, and (3) in self-isolation due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Self isolation was defined as staying-at-home and only leaving for essential activities such as food shopping, visiting the pharmacist or other health professionals. Participants who self-reported the presence of COVID-19 symptoms, assessed through a list of symptoms (fever, cough, dry mouth, coriza, sore throat), were removed from this analysis.

Moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and sedentary behavior (SB) assessment

Participants were asked to recall the amount of time in vigorous and moderate physical activity, and sedentary behavior they undertook on an average day, separately both pre- and during self-isolation [16]. Participants were asked: (1) “How much time on an average day have you spent in vigorous activity before/since social distancing?”; (2) “How much time on an average day have you spent in moderate activity since/before social distancing?” and (3) “How much time on an average day have you spent sitting since/before social distancing?” Responses were given in hours and minutes. MVPA and SB were analyzed as continuous variables (minutes per day). We also categorized PA levels (≥ 30 min/day or < 30 min/day of MVPA), which is in accordance with the WHO recommendations. Next, four categories were derived to identify patterns of change: (1) persistent inactive (< 30 min/day of MVPA pre and during the pandemic), (2) decreased PA (≥ 30 min/day of MVPA pre and < 30 min/day of MVPA during the pandemic), (3) increased PA (< 30 min/day of MVPA pre and ≥ 30 min/day of MVPA during the pandemic) and (4) persistent active (≥ 30 min/day of MVPA pre and during the pandemic).

Covariates

Demographic data were collected, including sex (men or women), age (in 10-year age bands), ethnicity (Caucasian, Black, Asian, mixed, others), marital status (single, divorced, widowed or married), employment (employed, student, military, unemployed), monthly household income ≤ R$1254, R$1255–R$2004, R$2005–R$8640, R$8641–R$11,261 ≥ R$11,262). Health behaviors data included current smoking (y/n) or alcohol consumption (y/n). Clinical data included self-reported previous diagnosis of physical diseases or mental disorders, such as: obesity, hypertension, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and other coronary diseases, other cardiac diseases, varicose veins of lower extremities, osteoarthritis, chronic neck pain, chronic low back pain, chronic allergy (excluding allergic asthma), chronic bronchitis, emphysema or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, diabetic retinopathy, cataract, peptic ulcer disease, urinary incontinence or urine control problems, hypercholesterolemia, chronic skin disease, chronic constipation, liver cirrhosis and other hepatic disorders, stroke, chronic migraine/others, depression, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia/others. Number of days (extension) in self-isolation was registered with a single question.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using mean and standard deviation (SD) or 95% confidence interval (95%CI) for continuous data and the raw numbers and % for categorical variables. Normality was checked with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Due to the non-normal distribution, the mean changes (pre versus during the pandemic) of MVPA levels and SB were evaluated using two generalized estimating equations models (GEE), one with changes in MVPA and one with change in SB as the dependent variable. The models were run testing the time effects (pre/during) and the interactions between time and the factors included in the model. The factors included in the models were (sex [male versus female], age [young adults {18–34 years} versus middle-age adults {35–54 years} versus older adults {55–65 years}], ethnicity [Caucasian versus Asian/Black/mixed/others], marital status [married versus single/divorced/widowed], employment [employed/students/military versus unemployed/retired], monthly household income [< R$2005 versus R$2005–R$8640 versus R$8641–R$11,261 versus > R$11,261], current smoking [yes versus no], alcohol consumption [yes versus no], self-reported previous diagnosis of any chronic diseases [yes versus no] or any mental disorders [yes versus no]). When the interaction between time and any factor was significant, the Bonferroni test was applied. The results of the models are presented using estimated marginal means and 95% CI. We also calculated the delta% change (pre to during), together with 95% CI as the effect size measure. The associations between the time (in days) in self-isolation and the change in MVPA and SB were tested using linear regression models. Days in self-isolation were collected as a continuous variable, and linear regression models were used to test the association of time in self-isolation with changes in MVPA and SB. The level of statistical significance was set at p value < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS (v. 21).

Results

A total of 1354 participants responded to the survey. Of these, 877 participants reported being in self-isolation and provided complete data for the present analysis. The sample was predominantly comprised of women (n = 635, 72.7%), young adults ranging from 18 to 34 years (n = 471, 53.7%), Caucasians (n = 669, 76.3%), singles (n = 442, 50.9%), currently employed/students/military (n = 723, 92.6%), with a monthly income ranging from R$2005 to R$8640 (n = 364, 41.5%), non-smokers (n = 836, 95.3%), currently consuming alcohol (n = 605, 69.1%), with a self-reported previous diagnosis of a physical chronic disease (n = 824, 94%) and without a self-reported previous diagnosis of a mental disorder (n = 523, 59.6%). More than half of the participants were from the Rio Grande do Sul state (80%), 11% from the Rio de Janeiro, and about 6% from Ceará. Participants were on average 27.13 (6.57) days in self-isolation. The full details of the sample can be seen at Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Category/mean (standard deviation) | Overall N = 877a (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 238 (27.3) |

| Female | 635 (72.7) | |

| Age | 18–24 years | 131 (14.9) |

| 25–34 years | 340 (38.8) | |

| 35–44 years | 220 (25.1) | |

| 45–54 years | 108 (12.3) | |

| 55–64 years | 78 (8.9) | |

| Ethnicity | Asian | 3 (0.3) |

| Black | 24 (2.7) | |

| Mixed | 163 (18.6) | |

| Caucasian | 669 (76.3) | |

| Others | 16 (1.8) | |

| Marital Status | Married | 363 (41.4) |

| Widowed | 4 (0.5) | |

| Divorced | 60 (6.9) | |

| Single | 442 (50.9) | |

| Employment | Employed | 558 (63.6) |

| Unemployed | 43 (1.6) | |

| Student | 235 (26.8) | |

| Military | 19 (2.2) | |

| Retired | 22 (2.5) | |

| Monthly household income | < R$1254 ($232) | 30 (3.4) |

| R$1255 ($232)–R$2004 ($371) | 94 (10.7) | |

| R$2005 ($371)–R$8640 ($1600) | 364 (41.5) | |

| R$8641 ($1600)–R$11,261 ($2085) | 139 (15.8) | |

| > R$11,262 ($2085) | 250 (28.5) | |

| Current smoking | No | 836 (95.3) |

| Yes | 41 (4.7) | |

| Current alcohol consumption | No | 271 (30.9) |

| Yes | 605 (69.1) | |

| Self-reported previous diagnoses of physical disease | No | 53 (6) |

| Yes | 824 (94) | |

| Self-reported previous diagnoses of mental disorder | No | 523 (59.60) |

| Yes | 354 (40.4) | |

| Days in self isolation | Mean (standard deviation) | 27.07 (6.71) |

aTotal sample with available data. Number of cases can be different for each variable due to missing cases (minimum = 869)

Mean changes in MVPA and SB (pre versus during pandemic)

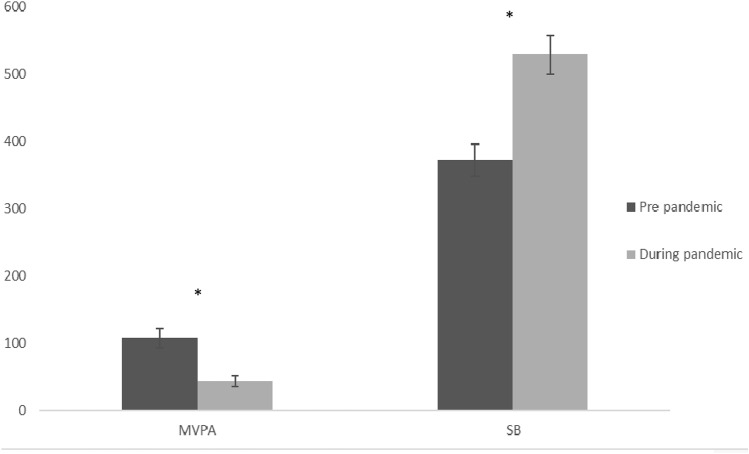

A total of 432 (49.3%) of participants persisted to be active during the pandemic, 32 (3.6%) increased MVPA levels during the pandemic, 306 (34.9%) reduced MVPA levels during the pandemic, and 107 (12.2%) persisted to be inactive. We found an overall reduction of 64.28 (95% CI 36.06–83.33) minutes per day on time spent in MVPA, corresponding to a reduction of 59.7% (95% CI 35.64–82.21, p < 0.001). The average time spent in SB increased 42.0% (95% CI 31.74–52.50, p < 0.001) during the pandemic, corresponding to additional 152.3 (95% CI 111.9–192.7) minutes per day in SB. The mean time spent in MVPA and SB at baseline and during the pandemic can be found at Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary behavior, pre and during COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 in Brazil. Values are shown as the estimated marginal means, in minutes per day, of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and sedentary behavior (SB) together with their standard error. Significant changes across time were found for MVPA (p < 0.001) and SB (p < 0.001)

Correlates of MVPA change

Significant interactions in MVPA change were found for age (p = 0.013), marital status (p = 0.006) and employment (p = 0.008). Bonferroni post-hoc test found that young adults (mean change = − 71.37, 95% CI − 99.76.51 to − 42.98) and middle-age adults (mean change = − 66.76, 95% CI − 94.50 to − 39.01) had greater decreases in time spent in MVPA when compared to older adults (mean change = − 54.70, 95% CI − 86.25 to − 23.16). Also, those not married (single/divorced/widowed) had greater reductions (mean change = − 75.50, 95% CI − 102.00 to − 49.00) when compared to those married (mean change = − 53.05, 95% CI − 79.36 to − 26.75), and those with an occupation (employed/student/military) had greater reductions (mean change = − 78.69, 95% CI − 105.21 to − 52.16) when compared to those without occupation (unemployed/retired. Mean change = − 49.87, 95% CI − 78.83 to − 20.90). The detailed results of the MVPA model with mean changes can be seen in Table 2. Those not married (mean difference = 22.08, 95% CI 6.79–37.36, p = 0.005), and with no occupation (mean difference = 38.55, 95% CI 14.08–63.03, p = 0.002) had greater MVPA levels at baseline (pre and during pandemic means are shown in Supplementary Material 1). The number of days in self-isolation was not associated with changes in MVPA (unstandardized beta coefficient = 0.234, 95% CI − 0.816 to 1.284, p = 0.662, R2 = 0.00).

Table 2.

Moderate to vigorous physical activity change (pre-post pandemic) in self-isolated adults during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in 2020 in Brazil

| Characteristics | Category | MVPA change (pre versus during) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean change in minutes | 95% CI | Delta% | 95% CI (%) | Interaction p value | ||||

| Sex | Male | – 65.86 | – 92.26 | – 39.52 | – 61.24 | – 85.79 | – 36.75 | 0.778 |

| Female | – 62.71 | – 89.37 | – 36.05 | – 58.18 | – 82.91 | – 33.44 | ||

| Age | Young adults (18–35 years) | – 71.37a | – 99.76 | – 42.98 | – 72.68 | – 101.51 | – 43.77 | 0.013 |

| Middle age adults (36–55 years) | – 66.76a | – 94.50 | – 39.01 | – 64.53 | – 91.34 | – 37.07 | ||

| Older adults (55–64 years) | – 54.70b | – 86.25 | – 23.16 | – 45.08 | – 71.08 | – 19.08 | ||

| Ethnicity | Black/Asian/Mixed/Others | – 66.00 | – 95.52 | – 36.48 | – 62.67 | – 90.70 | – 34.64 | 0.216 |

| White | – 62.55 | – 86.72 | – 38.38 | – 56.59 | – 78.87 | – 34.98 | ||

| Marital status | Single/divorced/widowed | – 75.50a | – 102.00 | – 49.00 | – 63.60 | – 85.93 | – 41.28 | 0.006 |

| Married | – 53.05b | – 79.36 | – 26.75 | – 54.91 | – 82.14 | – 27.68 | ||

| Employment | Employed/students/military | – 78.69a | – 105.21 | – 52.16 | – 61.99 | – 82.88 | – 41.09 | 0.008 |

| Unemployed/retired | – 49.87b | – 78.83 | – 20.90 | – 56.42 | – 89.19 | – 23.64 | ||

| Monthly household income | < R$2005($371) | – 82.58 | – 114.49 | – 50.66 | – 63.52 | – 88.15 | – 39.00 | 0.647 |

| R$2005($371)–R$8640($1600) | – 57.53 | – 82.31 | – 32.75 | – 56.57 | – 80.94 | – 32.20 | ||

| R$8641($1600)–R$11,261($2085) | – 56.72 | – 89.26 | – 24.19 | – 58.06 | – 91.38 | – 24.76 | ||

| > R$11,261 | – 60.28 | – 88.92 | – 31.63 | – 59.44 | – 87.69 | – 31.19 | ||

| Current smoking | Yes | – 70.76 | – 112.95 | – 28.57 | – 67.02 | – 106.9 | – 27.06 | 0.090 |

| No | – 57.80 | – 77.29 | – 38.30 | – 52.77 | – 70.43 | – 34.90 | ||

| Current alcohol consumption | Yes | – 58.39 | – 84.85 | – 31.93 | – 57.09 | – 82.97 | – 31.22 | 0.378 |

| No | – 70.16 | – 97.22 | – 43.10 | – 62.06 | – 85.29 | – 38.12 | ||

| Self-reported previous diagnosis of mental disorders | Yes | – 67.46 | – 95.88 | – 39.05 | – 63.37 | – 90.07 | – 36.68 | 0.112 |

| No | – 61.09 | – 85.60 | – 36.58 | – 56.11 | – 78.63 | – 33.60 | ||

| Self-reported previous diagnosis of physical diseases | Yes | – 67.42 | – 89.62 | – 45.23 | – 59.64 | – 79.28 | – 40.01 | 0.803 |

| No | – 61.13 | – 96.90 | – 25.63 | – 59.77 | – 94.74 | – 25.63 | ||

Different letters mean significant differences according the Bonferroni post-hoc test (p < 0.05)

Bold values indicate that the significance of p < 0.05

Correlates of SB changes

The interactions found for the SB model were age (p < 0.001), marital status (p = 0.024), employment (p = 0.03), and self-reported previous diagnosis of mental disorders (p = 0.003). Young adults had greater increases (mean change = 190.48, 95% CI 149.65–231.30) in time spent in SB when compared to middle age (mean change = 143.35 95% CI 99.48–187.21) or older adults (mean change = 136.71, 95% CI 77.88–195.54). Also, greater increases in time spent in SB were found in those not married (mean change = 176.15, 95% CI 133.74–218.56) compared to those married (mean change = 137.96, 95% CI 96.85–178.24), in those with an occupation (mean change = 179.85, 95% CI 142.15–217.55) compared to those with no occupation (mean change = 133.84, 95% CI 79.26 to 188.42), and in those with a self-reported previous diagnosis of mental disorders (mean change = 173.16, 95% CI 129.97–216.34) compared to those with no history of mental disorders (mean change = 140.53, 95% CI 101.07–180.00). The detailed results of the SB model with interactions can be seen in Table 3. Younger adults spent more time in SB than middle-age adults (mean difference = 39.99, 95% CI 5.27–74.71, p = 0.017), but not more than older adults (mean difference = 43.28, 95% CI − 13.15 to 99.75, p = 0.20). Those with a self-reported previous diagnosis of a mental disorder spent more time in SB at baseline (mean difference = 24.09, 95% CI 0.41–48.66, p = 0.046) than those without (pre and during pandemic means are shown in Supplementary Material 2). The number of days in self-isolation was not associated with changes in SB (unstandardized beta coefficient = 0.306, 95% CI − 1.732 to 2.345, p = 0.77, R2 = 0.00). The sample size (n = 1000) was calculated for evaluating the association of MVPA with mental health outcomes, published elsewhere [22].

Table 3.

Sedentary behavior change (pre-post pandemic) in self-isolated adults during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in 2020 in Brazil

| Characteristics | Category | SB change (pre versus during) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean change in minutes | 95% CI | Delta% | 95% CI (%) | Interaction p value | ||||

| Sex | Male | 161.41 | 119.48 | 203.35 | 42.51 | 31.47 | 53.56 | 0.380 |

| Female | 152.28 | 111.87 | 192.69 | 41.72 | 30.61 | 52.78 | ||

| Age | Young adults (18–35 years) | 190.48a | 149.65 | 231.30 | 47.62 | 37.42 | 57.81 | < 0.001 |

| Middle age adults (36–55 years) | 143.35b | 99.48 | 187.21 | 39.87 | 27.62 | 51.99 | ||

| Older adults (55–64 years) | 136.71b | 77.88 | 195.54 | 38.34 | 21.82 | 54.80 | ||

| Ethnicity | Black/Asian/Mixed/Others | 155.43 | 109.04 | 201.81 | 41.42 | 29.07 | 53.81 | 0.940 |

| White | 158.26 | 121.24 | 195.29 | 42.81 | 32.80 | 52.83 | ||

| Marital status | Single/divorced/widowed | 176.15a | 133.74 | 218.56 | 46.87 | 35.58 | 58.15 | 0.024 |

| Married | 137.54b | 96.85 | 178.24 | 37.29 | 26.18 | 48.32 | ||

| Employment | Employed/students/military | 179.85a | 142.15 | 217.55 | 45.58 | 36.02 | 55.14 | 0.030 |

| Unemployed/retired | 133.84b | 79.26 | 188.42 | 38.22 | 22.63 | 53.81 | ||

| Monthly household income | < R$2005($371) | 171.17 | 118.64 | 223.70 | 47.39 | 32.85 | 61.94 | 0.632 |

| R$2005($371) –R$8640($1600) | 166.74 | 125.52 | 207.95 | 45.81 | 34.49 | 57.14 | ||

| R$8641($1600)—R$11,261 ($2085) | 150.63 | 102.05 | 199.21 | 40.36 | 27.34 | 53.38 | ||

| < R$2005($371) | 138.85 | 92.10 | 185.59 | 35.50 | 23.54 | 47.45 | ||

| Current smoking | Yes | 158.87 | 108.25 | 209.49 | 42.72 | 29.10 | 56.33 | 0.984 |

| No | 154.82 | 116.98 | 192.66 | 41.53 | 31.38 | 51.68 | ||

| Current alcohol consumption | Yes | 173.39 | 134.25 | 212.53 | 46.86 | 36.28 | 57.44 | 0.091 |

| No | 140.30 | 96.75 | 183.85 | 37.44 | 25.82 | 49.06 | ||

| Self-reported previous diagnosis of mental disorders | Yes | 173.16a | 129.97 | 216.34 | 45.02 | 33.79 | 56.25 | 0.003 |

| No | 140.53b | 101.07 | 180.00 | 39.03 | 28.07 | 49.99 | ||

| Self-reported previous diagnosis of physical diseases | Yes | 139.60 | 107.20 | 172.00 | 37.85 | 29.07 | 46.64 | 0.358 |

| No | 174.09 | 117.49 | 230.69 | 46.31 | 31.25 | 61.37 | ||

Different letters mean significant differences according the Bonferroni post-hoc test (p < 0.05)

Bold values indicate that the significance of p < 0.05

Discussion

The present study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study demonstrating the impact of the self-isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic on Brazilians for self-reported MVPA and SB. Approximately 35.0% of the sample became insufficiently active during the self-isolation period. Only 3.6% became active with self-isolation. On average, there was a reduction of about 1 h/day of time spent in MVPA, which corresponds to a reduction of 60.0% of their MVPA pre-pandemic levels. Participants reported spending 2.5 h/day more in SB during the pandemic than before the pandemic, corresponding to an increase of 40.0%.

The reduction in MVPA levels in Brazilians is consistent with the findings of previous studies in other countries. For example, we found that roughly 35.0% of respondents became inactive during the self-isolation period as did about 50.0% in similar studies collected in France [12], the USA [17], and Australia [9]. Our results included reductions of 60.0% of the time spent in MVPA in Brazil, which is comparable to the reductions found in the USA, where there was a decrease of 47.0% on time spent in moderate PA [17]. Additionally, we observed an increase of about to 2.5 h/day on time spent in SB, which is consistent with other studies that have found an increase of about 2–3 h/day of SB in multiple countries [14, 23]. These findings highlight the urgent need for public health strategies to mitigate the impact of self-isolation on MVPA and SB.

Greater reductions in MVPA and increases in SB were found among younger adults, which is line with the findings from Italy and the UK [13, 15]. It is possible that this age group had fewer resources and greater difficulty coping with emotional responses to this situation [24]. In addition, those not married and currently working had higher MVPA levels at baseline, but decreased their MVPA to similar levels to those not married and with no work during the pandemic. Of note, those currently employed might have reduced their commuting-related PA and have likely increased their SB time due to online meetings and activities. Lastly, those with a self-reported previous pandemic diagnosis of a mental disorder spent more time in SB and reported the greatest increases in time spent in SB during the pandemic. This finding is in accordance with a study in the UK [15] that found a greater reduction in MVPA in people with depression. This finding is also consistent with previous studies showing that people with mental disorders have higher SB levels than people without mental disorders [25–27] and suggests that self-isolation during the pandemic might be specifically detrimental to people with a previous diagnosis of a mental disorder.

There is ample evidence to justify making PA promotion a global public health priority during the coronavirus pandemic [3]. The COVID-19 pandemic appears to have impacted mental health globally, increasing rates of depression and anxiety symptoms and disorders [5]. On the other hand, physical activity is a protective factor for mental disorders [28–30]. During the pandemic, cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence suggests that those with higher PA or lower SB levels are less likely to present depressive symptoms [22, 31]. Promoting MVPA and reducing SB during the pandemic is also essential for physical health. Higher mortality due to COVID-19 is seen in those with clinical comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease [32]. Increasing time spent in MVPA and reducing time spent in SB seems to reduce the risk of developing multiple chronic diseases, including those associated with a higher risk of COVID-19 mortality [33]. For example, people with higher PA levels have 35% and 23% less risk of developing diabetes [34] and heart failure [35], respectively. In addition, achieving the public health recommendations of 150 min of MVPA per week reduces the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality [36]. Lastly, initial evidence has suggested that physical inactivity may be a risk factor for hospitalization due to COVID-19 [37], further underlining the potential importance of promoting PA during the pandemic.

The present study has some limitations. First, MVPA and SB were assessed using self-reported questionnaires. Self-reported questionnaires are commonly associated with overestimations of MVPA [38] and underestimation of SB [39]. Second, pre-pandemic MVPA and SB were assessed retrospectively, and both can be susceptible to memory bias. Third, the representativeness of the sample is limited. However, participants were drawn from 24 of the 27 federative units of Brazil, with most participants being from the Rio Grande do Sul state, Rio de Janeiro, and Ceará. Also, some groups such as adults aging 55–64, Asian and Black people, and those with a household income lower than < R$1254 are poorly represented. Fourth, we could not explore changes in light PA, such as walking. Also, we could not explore the changes in time spent on MVPA across the different PA domains (work/occupational, leisure, transportation, household). It is possible, for example, that some participants reduced the time spent in leisure, transportation, or work/occupational activities, but increased the time spent in household activities. This is important since we know that some mental health benefits are more likely to be associated with time spent in leisure activities [40]. The strengths of the manuscript are the large sample size of self-isolating Brazilians and the possibility to explore a variety of moderators. Although the sample size was calculated for estimating the association of MVPA and mental health outcomes, the large sample size is sufficiently powered for the present analyses.

Conclusion

Self isolation during the pandemic significantly reduced time spent in MVPA and increased time spent in SB in Brazilian adults, particularly in younger adults, those who were single, and those who were employed. These findings highlight the urgent need of the adoption of public health strategies to address the impact of self-isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic on MVPA and SB.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

This study was part financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001. André Werneck is supported by a São Paulo Research Foundation PhD scholarship (FAPESP process: 2019/24124-7). Mark Tully is partly supported by funding as Director of the Northern Ireland Public Health Research Network by the Research and Development Division of the Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Federal University of Santa Maria Research Ethics Committee and by the National Commission of Ethics in Research [CONEP] (30244620.1.0000.5346).

Informed consent

All participants read and signed the informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Mark Tully, Lee Smith are joint final authors.

References

- 1.Organization WH (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 179. 2020

- 2.Saúde MD (2020) Boletim epidemiológico 05 - 20/03/2020, M.d. Saúde, Editor. 2020: http://maismedicos.gov.br/images/PDF/2020_03_13_Boletim-Epidemiologico-05.pdf. Accessed 13 Mar 2020

- 3.Sallis J, et al. An international physical activity and public health research agenda to inform COVID-19 policies and practices. J Sport Health Sci. 2020;9(4):328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ornell F, et al. Pandemic fear and COVID-19: mental health burden and strategies. Brazil J Psychiatry. 2020;42(3):232–235. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks SK, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):126–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ainsworth BE, et al. Compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(8):1575–1581. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallo LA, et al (2020) The impact of isolation measures due to COVID-19 on energy intake and physical activity levels in Australian university students. medRxiv, p. 2020.05.10.20076414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Stanton R, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in Australian adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4065. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lesser I, Nienhuis C. The impact of COVID-19 on physical activity behavior and well-being of Canadians. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3899. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sekulic D, et al. Prospective analysis of levels and correlates of physical activity during COVID-19 pandemic and imposed rules of social distancing; Gender specific study among adolescents from Southern Croatia. Sustainability. 2020;12(10):4072. doi: 10.3390/su12104072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deschasaux-Tanguy M, et al (2020) Diet and physical activity during the COVID-19 lockdown period (March-May 2020): results from the French NutriNet-Sante cohort study. medRxiv, p. 2020.06.04.20121855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Giustino V, et al. Physical activity levels and related energy expenditure during COVID-19 quarantine among the sicilian active population: a cross-sectional online survey study. Sustainability. 2020;12:4356. doi: 10.3390/su12114356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castañeda-Babarro A, Arbillaga-Etxarri A, Gutiérrez-Santamaría B, Coca A (2020) Physical activity change during COVID-19 confinement. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: 6878. 10.3390/ijerph17186878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Rogers NT et al (2020) Behavioral change towards reduced intensity physical activity is disproportionately prevalent among adults with serious health issues or self-perception of high risk during the UK COVID-19 lockdown. Front public health 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Lee Smith JM, López-Sanchéz GF, Schuch F, Grabovac I, Veronese N, Abufaraj A, Coperchiona C, Tully M (2020) Prevalence and correlates of physical activity in a sample of UK adults observing social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Dunton GF et al (2020) Early effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity locations and behaviors in adults living in the United States. Prev Med Rep 20:101241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Dunton GF, Do B, Wang SD (2020) Early effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and sedentary behavior in children living in the U.S. BMC Public Health 20:1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Meyer J, et al (2020) Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviour due to the COVID-19 outbreak and associations with mental health in 3,052 US adults

- 20.Tremblay MS, et al. Sedentary behavior research network (SBRN)–terminology consensus project process and outcome. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0525-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheval B, et al. Relationships between changes in self-reported physical activity, sedentary behaviour and health during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in France and Switzerland. J sports sci. 2020;39(6):699–704. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2020.1841396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuch FB, et al. Associations of moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary behavior with depressive and anxiety symptoms in self-isolating people during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey in Brazil. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113339. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ammar A, et al. Effects of COVID-19 Home Confinement on Eating Behaviour and Physical Activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 International Online Survey. Nutrients. 2020;12:1563. doi: 10.3390/nu12061563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott SB, Sliwinski MJ, Blanchard-Fields F. Age differences in emotional responses to daily stress: the role of timing, severity, and global perceived stress. Psychol Aging. 2013;28(4):1076–1087. doi: 10.1037/a0034000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuch F, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior in people with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vancampfort D, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior in people with bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;201:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vancampfort D, et al. Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):308–315. doi: 10.1002/wps.20458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brokmeier LL, et al. Does physical activity reduce the risk of psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Psychiatry Res. 2019;284:112675. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuch FB, et al. Physical activity and incident depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(7):631–648. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17111194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuch FB, et al. Physical activity protects from incident anxiety: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36(9):846–858. doi: 10.1002/da.22915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolf S, et al (2021) Is Physical activity associated with less depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic? A rapid systematic review. Sports Med. 10.1007/s40279-021-01468-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Zhou F, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine–evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25:1–72. doi: 10.1111/sms.12581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aune D, et al. Physical activity and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30(7):529–542. doi: 10.1007/s10654-015-0056-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aune D, et al. Physical activity and the risk of heart failure: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36(4):367–381. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00693-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ekelund U, et al. Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1302–1310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamer M, et al. Lifestyle risk factors, inflammatory mechanisms, and COVID-19 hospitalization: a community-based cohort study of 387,109 adults in UK. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:184–187. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee PH, et al. Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):115. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prince S, et al. A comparison of self-reported and device measured sedentary behaviour in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0902-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teychenne M, et al. Do we need physical activity guidelines for mental health: What does the evidence tell us? Ment Health Phys Act. 2020;18:100315. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2019.100315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.