Abstract

As one of the most important imaging modalities, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) still faces relatively low sensitivity to monitor low-abundance molecules. A newly developed technology, hyperpolarized 129Xe magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), can boost the signal sensitivity to over 10 000-fold compared with that under conventional MRI conditions, and this technique is referred to as ultrasensitive MRI. However, there are few methods to visualize complex mixtures in this field due to the difficulty in achieving favorable “cages” to capture the signal source, namely, 129Xe atoms. Here, we proposed metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) as tunable nanoporous hosts to provide suitable cavities for xenon. Due to the widely dispersed spectroscopic signals, 129Xe in different MOFs was easily visualized by assigning each chemical shift to a specific color. The results illustrated that the pore size determined the exchange rate, and the geometric structure and elemental composition influenced the local charge experienced by xenon. We confirmed that a complex mixture was first differentiated by specific colors in ultrasensitive MRI. The introduction of MOFs helps to overcome long-standing obstacles in ultrasensitive, multiplexed MRI.

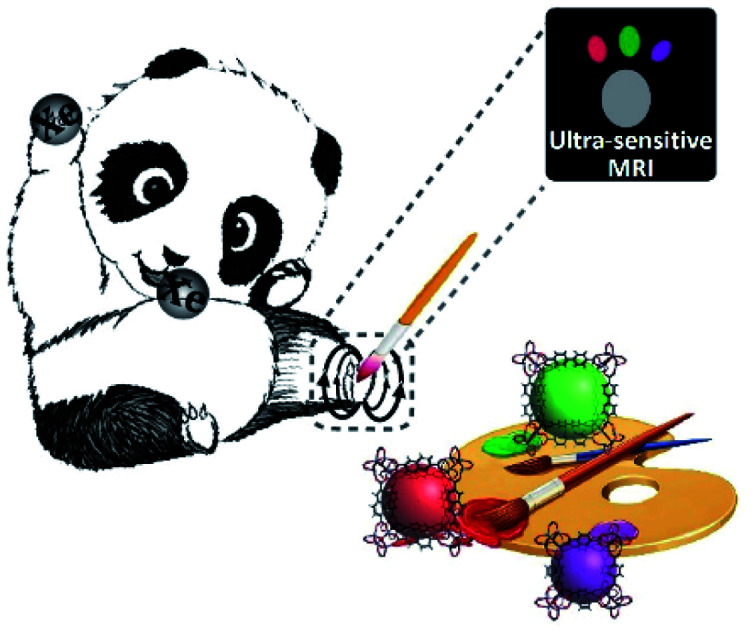

Metal organic frameworks with tunable pore structures are able to provide varied chemical environments for hyperpolarized 129Xe atom hosting, which results in distinguishing magnetic resonance signals, and stains ultra-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with diverse colors.

Introduction

Multicolor imaging provides a method for investigating complex biological processes in living samples. Target analytes that are labeled with different dyes can be clearly distinguished by color differentiation.1 Multicolor imaging has been widely explored in chemical, biological, and medical fields; this technique can visualize T lymphocytes, bacteria, and tumors in the whole body,2 constantly monitor drug release from cargos,3 intensively investigate the spatiotemporal dynamics of signaling cascades,4 and quantitatively detect the tissue volume.5 Despite extensive studies, multicolor imaging applications are still limited at the subcutaneous, cellular, or in vitro levels. In most scenarios, multicolor imaging methods are based on optical technologies, such as fluorescence,6 luminescence,7 phosphorescence,8 and Raman spectroscopies,9 which exhibit poor penetrability to image targets in deeply opaque tissues.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a clinically used imaging modality that can penetrate living tissue without depth limitations. However, only approximately 1 out of 100 000 atoms contributes to the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) detection signal at thermal equilibrium,10 resulting in relatively low sensitivity compared with optical techniques. Therefore, samples with millimolar (mM) concentrations are usually prepared to achieve detectable signals for NMR or MRI studies. By using radiofrequency (RF) irradiation to saturate the target signal and then transfer it to water protons, chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) provides a new alternative for increasing magnetic resonance (MR) signals from exchangeable protons up to more than 1000 times.11 Numerous CEST contrast agents with various irradiation frequencies (chemical shifts) have been exploited.12–15 Nevertheless, background signals from endogenous glucose, creatine, glutamate, nucleic acids, peptides, and other biomolecules make it difficult to extract target information due to overlapping signals.

A newly developed technique, namely, hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI, has overcome the above sensitivity and background noise issues by increasing the signal of the heteronuclear spin of 129Xe. In previous studies, we used a homemade polarizer to transfer the angular momentum from photons to 129Xe atoms, achieving a hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI enhancement of 100 000 times over that at thermal equilibrium. This up-to-date technology can monitor gas–gas16–20 and gas–blood21–24 exchange in the lungs, as well as evaluate brain function.25,26 Because of the much higher sensitivity, hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI is referred to as ultrasensitive MRI.27,28 To confer targeting ability to chemically inert xenon, host “cages” with high xenon affinity are introduced and modified with targeting groups.29 The resulting 129Xe in cages produces new signals that can be separated from the dissolved free 129Xe signals in tissues and blood. Some nanostructures, such as porous nanoparticles,30 nanoemulsions,31 dendrimers,32 proteins,33 and genetically encoded reporters,34,35 could provide host cavities for xenon binding and exchange. Nevertheless, 129Xe signals in most of the developed nanocages are broad, due to the complicated exchange processes and the intricate chemical microenvironments. Some supramolecular and superstructural cages, such as cryptophane36–38 and metal–organic capsules,39–41 show narrower signal peaks than nanocages because their pores bind only one xenon atom and exhibit an intermediate exchange rate at room temperature. By using targeted cryptophane as a cage, a low detection limit of 10−10 M was achieved to trace intracellular biothiol with hyperpolarized 129Xe chemical exchange saturation transfer (Hyper-CEST) MRI.42 The multiplexing capacity of 129Xe NMR has been exploited by modifying or replacing the linker of cryptophane.43 However, 129Xe MRI biosensors in real samples were physically separated from each other.44,45 There are very few reports on detecting complex mixtures by 129Xe MRI, which may be due to the unacceptable biocompatibility, negligible chemical shift differences, or complicated synthesis procedures of cryptophane. Hence, searching for better host cages remains a challenge in exploiting the applications of ultrasensitive MRI for multitarget imaging.

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are synthetic materials with controllable pores that have been widely studied in environmental,46,47 energy,48,49 and nanomedicine50,51 fields. Compared with other nanomaterials, MOFs have unique advantages because their skeleton, structure, and pore function can be carefully designed and controlled by the selection of starting derivatives and metals. It is worth mentioning that MOFs have been successfully applied in xenon separation,52 which demonstrates the high affinity between xenon and MOFs and inspires us to develop MOF-based 129Xe biosensors. Besides, it was reported that the 129Xe NMR chemical shift was increased from the larger isoreticular MOF (UiO-67) to the smaller one (UiO-66).53 If we can find an MOF that permits only a single xenon atom exchange per pore, such as cryptophane, a favorable signal may be obtained in ultrasensitive MRI. This would overcome the issue that 129Xe signals in nanomaterial-based cages are typically too broad and weak. More importantly, the 129Xe atom is extremely sensitive to its local environment; its MR chemical shift spans over 5000 ppm, which is a much wider range than that of 1H (∼20 ppm). On the basis of the above theories, we expect to develop a series of MOFs with different pore structures to offer diverse chemical surroundings for 129Xe atom thrusts and achieve different MR signals. Inspired by semiconductor quantum dots, which can generate diverse emission colors by simply controlling the dot's inner core shell,54 a distinguishable 129Xe MR signal resulting from each edited MOF may also be “stained” with its own color to show the signal difference. Thus, the introduction of MOFs may provide comparable 129Xe MRI labels for multitarget analysis.

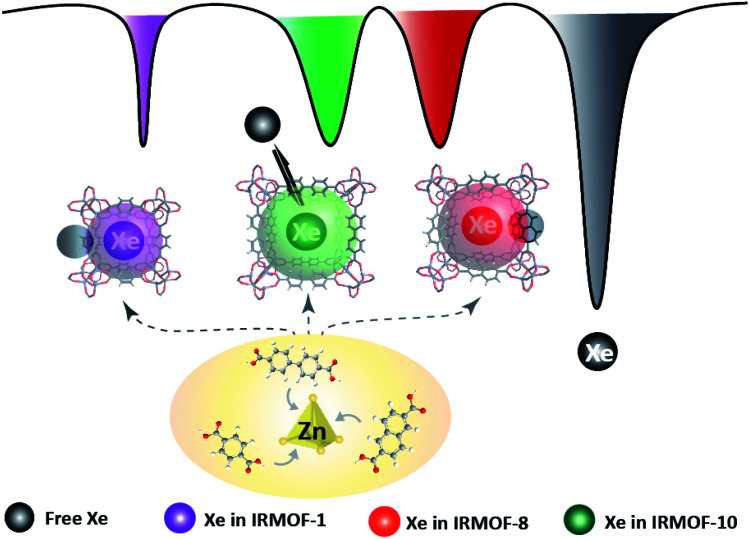

In this study, we investigated the potential of modifying the MOF pore structure to gain multiple signals for coloring ultrasensitive MRI (Scheme 1). A class of MOF nanoparticles was formed by similar octahedral Zn–O–C clusters and benzene links, and their pore size was expanded by extending the molecular struts. It was shown that the exchange rate of the 129Xe atom in MOF pores increased as the organic link was extended, and the resulting signal differences between any two MOFs were large enough to be completely separated. To better understand the inherent key factors that led to these unique properties, we performed theoretical calculations of 129Xe in each MOF pore. The results illustrated that the pore sizes and charge numbers contributed to the different chemical microenvironments, which manifested as diverse chemical shifts. Based on the above experimental and theoretical studies, the MOF family was developed as a favorable contrast agent for ultrasensitive MRI. Furthermore, three types of MOF nanoparticles with different pore sizes and structures were mixed. The 129Xe NMR and MRI results showed that the signals in the three MOFs could be totally received and completely discriminated. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that large 129Xe MR signal differentiation is obtained in a complex mixture by using a class of “nanocages” with similar chemical compositions. These results prove the concept of achieving distinguishable caged 129Xe MR signals by regulating the MOF structure and encoding ultrasensitive MRI with multiple colors that resulted from the different chemical shifts. Hence, ultrasensitive MRI with tunable MOFs opens a new approach for imaging complex mixtures without invasiveness, radiation, and depth limitations.

Scheme 1. MOF pore structures are altered to provide diverse microenvironments for 129Xe atom hosting and produce distinguishable MR signals. Multicolor 129Xe MR images are introduced by staining the unique signal in each altered MOF with a specific color.

Results

Production of MOF nanoparticles

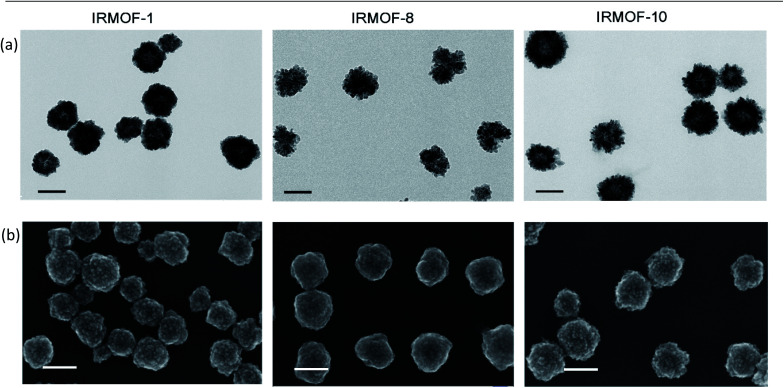

MOFs with similar structures were solvothermally prepared by mixing carboxylate benzene organic links with metallic node zinc ions and the stabilizing reagent polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP) in dimethylformamide (DMF)/ethanol. Their pore sizes were regulated with expanded link lengths. We introduced 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid, 2,6-naphthalenedicarboxylic acid, and biphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid as the organic links, and the produced MOFs were named IRMOF-1, IRMOF-8, and IRMOF-10, respectively. As shown in the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Fig. 1) images, the spherical nanoparticles indicated the morphology and structural features of the as-prepared IRMOF-1, IRMOF-8, and IRMOF-10 nanoparticles. When the visual field was further enlarged (Fig. S1–S3†), obvious lattice structures were observed (Fig. S4–S6†), and numerous small nanoparticles (∼10 nm) accumulated and formed IRMOF nanospheres. By counting the particle sizes in the TEM images, the IRMOF nanoparticles showed diameters of approximately 110 nm (Table S1†), while the dynamic light scattering (DLS) results showed particles that were ∼40 nm larger (Table S2†). The fabrication of these structures might be induced by a surface-energy-driven mechanism.55 The X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Fig. S13–S15†) and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Fig. S16–S18†) results further revealed the successful formation of IRMOF nanoparticles.

Fig. 1. Characterization of the morphology of the MOF nanoparticles. (a) TEM and (b) SEM images of IRMOF-1, IRMOF-8, and IRMOF-10 showed spherical structures and relatively uniform size distributions. Scale bar, 100 nm.

Modification of the MOF pore structure to achieve different cages for 129Xe hosting

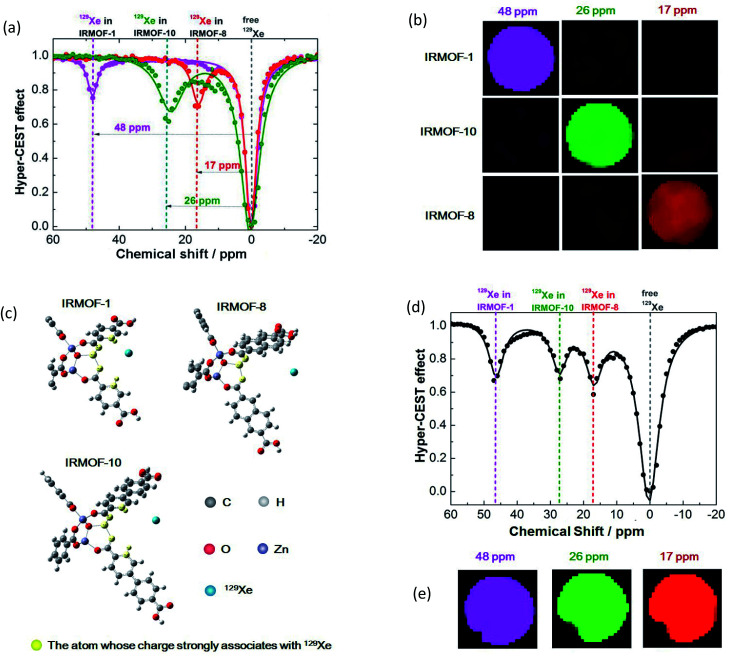

The free volume in crystals in the MOF could be varied by regulating the molecular linkers, and the produced MOFs would provide different pores as hosts for small molecules. In the present study, the free volume was expanded with extended benzene links, and the free diameters of pores in IRMOF-1, IRMOF-8, and IRMOF-10 were 7.93, 9.17, and 12.15 Å, respectively.56 The nanoscale pores may offer cavities for 129Xe atom hosting and then produce various MR signals due to the diverse microenvironments provided by the different-sized pores in each MOF. To investigate their potential as host cages to capture 129Xe atoms and produce new signals, we performed NMR studies of the designed MOFs with a 9.4 T spectrometer with a homemade 129Xe hyperpolarizer. In a typical CEST procedure, a series of RF irradiations was applied to saturate the MR signal of 129Xe in the cage, and the dissolved 129Xe signal was decreased when the free 129Xe atom was thrust and exchanged. As hypothesized, the 129Xe atom in each MOF produced an MR signal at its unique chemical shift; IRMOF-1, IRMOF-8, and IRMOF-10 were saturated at 48, 17, and 26 ppm, respectively (Fig. 2a). These irradiation differences were large enough to excite the signal from only one MOF under its particular frequency. For example, under 13 μT RF saturation at 48 ppm, IRMOF-1 produced sufficient contrast in ultrasensitive MRI (Fig. 2b), whereas signals from IRMOF-8 and IRMOF-10 samples remained silent. This phenomenon occurred because the RF at 48 ppm could only saturate the MR signal from 129Xe in IRMOF-1, and one irradiation at a defined chemical shift corresponded to one specific 129Xe cage. Simultaneously, ultrasensitive 129Xe MRI could be further colored by IRMOF-8 and IRMOF-10 with RF irradiation at 17 and 26 ppm, respectively. The MRI results showed that the three signals from the designed MOFs could be excited separately (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2. Manipulation of the MOF pore structure to produce unique 129Xe MR signals. (a) Frequency-dependent saturation spectra of IRMOF-1, IRMOF-8, and IRMOF-10. To eliminate the influence of solvent, chemical shifts were referenced to the dissolved free 129Xe atom. (b) Coloring ultrasensitive MRI with three types of MOF nanoparticles. Each MOF is saturated at its unique chemical shift, thus enabling discrimination from others in ultrasensitive MRI. (c) Calculating the charge in an edge of an MOF pore. Charge numbers contribute to the differences in chemical shifts. (d) A mixture containing IRMOF-1, IRMOF-8, and IRMOF-10 showed separated signals. (e) MOF nanoparticles provide diverse contrast agents for complex mixture imaging. The MOF mixture showing ultrasensitive MRI in three colors, thus enabling the labeling of three different targets in a single sample.

The pore size determines the exchange rate

We evaluated the interaction of 129Xe atoms with MOFs by quantitative Hyper-CEST analysis. A series of full Hyper-CEST spectra were obtained by saturating 129Xe in MOFs under the B1 field at 16, 13, 10, 6.5, and 3.5 μT (Fig. S25–S27†). After fitting, the exchange rates of 129Xe atoms in IRMOF-1, IRMOF-8, and IRMOF-10 were 428.57 ± 152.04, 1175.74 ± 936.60, and 2495.64 ± 547.81 s−1 (Table 1), respectively. The increased exchange rate along with the expanding pore diameter indicated that the increased size in the free “void volume” led to faster exchange of 129Xe atoms, and this result was consistent with our expectation.

129Xe-host interaction parameters obtained from quantitative Hyper-CEST. The free diameter of MOF pores was expanded as the organic length was extended from IRMOF-1 to IRMOF-10. The exchange rate of the 129Xe atom in the MOF increased with the expanding MOF pore diameter. The exchange rate of 129Xe in the MOF was considerably smaller than that in gas vesicles and larger than that in supermolecular cryptophane-A due to the intermediate pore space for Xe hosting.

Moreover, the exchange rate of 129Xe atoms in MOFs was considerably smaller than that in other nanocages (Table 1).57 According to previous research, the increase in particle size slowed the effective xenon exchange rate because diffusion limited the Xe residence times.31,59 As a result, the reported nanocages whose diameters were smaller than 200 nm had no detectable signal in ultrasensitive 129Xe NMR.31 In this study, we fabricated MOFs with a diameter of approximately 110 nm and achieved remarkable signals that were diverse and distinguishable. These favorable results may be attributed to the uniform, precise, and sub-nano/nanosized pore structure. The exchange process of xenon in MOFs was closer to that of supramolecular cryptophane than to diffusion in other nanocages. It was also notable that nanoparticles with smaller diameters were better to maximize the uptake rate and intracellular concentration.60 Compared with the reported cages, these MOF nanoparticles are advantageous for intracellular and in vivo analyses.

Charge numbers contribute to the differences in chemical shifts

Interestingly, the irradiation frequency (at a specific chemical shift) that saturates 129Xe in a nanocage was not related only to the pore size.61,62 The pore size gradually expanded from IRMOF-1 to IRMOF-10. The 129Xe atoms in the smallest pore of IRMOF-1 had the largest chemical shift difference compared with free 129Xe atoms (0 ppm). While the corresponding frequency of 129Xe in the other two MOFs did not behave as expected, the chemical shift of 129Xe in IRMOF-8 was 9 ppm smaller than that of IRMOF-10. We considered that the linker structure, length, and chemical composition might collectively influence the interaction between xenon and the cages.

To explain the disorder phenomenon, we further investigated the effect of electron clouds based on the IRMOF pore structures. We took one triangle and three edges in one lattice of IRMOF and then placed one xenon in them (Fig. S28†). R was defined as the distance from the xenon to the vertex of the lattice, and it was stretched along the diagonal line of the lattice to calculate the Mulliken charge change. As shown in Fig. S29,† the calculated chemical shift of 129Xe decreased in the order of IRMOF-1, IRMOF-10, and IRMOF-8 under the same R value. This trend fits well with the Hyper-CEST results (Fig. 2a). Then, the charge of each atom in the three systems was studied along with different R values. The atoms with charge root mean square changes larger than 0.01 in the three structures are shown in Fig. 2c, and the charges of these atoms with R = 1.8, 2.4, and 2.8 Å are presented in Table S4.† Those atoms in IRMOF-1 were close to those in IRMOF-10 due to the similar geometric structures of the edges. However, IRMOF-8 had fewer effective atoms than IRMOF-1 and IRMOF-10. We also noted that the absolute values of the charges on Zn and O for IRMOF-8 were smaller than those of IRMOF-1 and IRMOF-10; this led to a smaller interaction between IRMOF-8 and xenon than that between IRMOF-1 and IRMOF-10 with xenon. The charge on Zn, O, C, and H for IRMOF-1 was larger than that for IRMOF-10, and the pore size of IRMOF-1 was smaller than that of IRMOF-10. Thus, xenon has a higher probability of being close to the edges and the triangle in IRMOF-1. All these factors resulted in dispersed chemical shifts, that is, IRMOF-1 > IRMOF-10 > IRMOF-8.

Analysis of an MOF mixture by ultrasensitive MRI

Next, we studied the possibility of analyzing complex samples by ultrasensitive MRI. The prepared IRMOF-1, IRMOF-8, and IRMOF-10 nanoparticles were mixed and dispersed in an NMR tube; RF irradiation from −20 ppm to 60 ppm was performed within an interval of 1 ppm. The results illustrated that the peaks at 48, 17, and 26 ppm had no overlap and could be completely separated (Fig. 2d). The signals from the three IRMOFs were totally independent and did not influence each other. This phenomenon indicated that the introduced MOF nanoparticles may serve as three labels to test complex mixtures with hyperpolarized 129Xe. Further MRI experiments showed all three colored signals at 48, 17, and 26 ppm (Fig. 2e), demonstrating the existence of the three MOFs in the mixed sample.

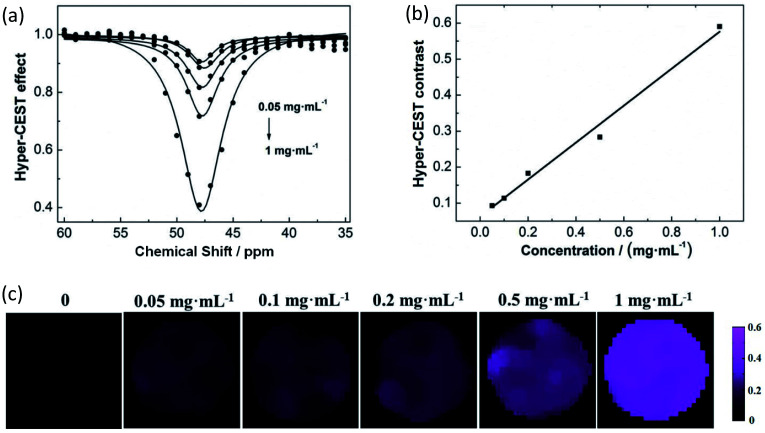

Quantitative measurements of the IRMOF nanoparticles by ultra-sensitive MRI

Taking IRMOF-1 nanoparticles as a model, the Hyper-CEST effect was enhanced with increasing concentrations (Fig. 3a). A linear response was obtained over the concentration range from 0.05 mg mL−1 to 1 mg mL−1 (Fig. 3b). The corresponding ultrasensitive MRI also showed a concentration-dependent intensity (Fig. 3c). Hence, the exploited MOF nanoparticles could be used as ultrasensitive MRI stains with diverse colors, making it possible to analyze complex samples qualitatively and quantitatively in the future.

Fig. 3. Quantitative measurements of IRMOF nanoparticles. (a) The Hyper-CEST effect of IRMOF-1 at concentrations of 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 mg mL−1. (b) The concentration of IRMOF-1 is linearly related to the Hyper-CEST contrast. (c) The intensity of ultrasensitive 129Xe MRI is enhanced as the concentration increases.

Conclusions

In this study, a complex mixture was first distinguished by color differentiation in ultrasensitive MRI, which was achieved by the introduction of MOF nanoparticles as contrast agents. Compared to other hard-to-obtain 129Xe cages, MOF nanoparticles with uniform pores could be easily fabricated by altering the length of the starting organic links. The produced MOF nanoparticles provided three types of pore spaces with different chemical microenvironments to capture the signal source of 129Xe atoms. As the 129Xe atom was extremely sensitive to the surrounding environment, the designed MOF nanoparticles produced distinct 129Xe MR signals under three irradiation frequencies, resulting in three colors for ultrasensitive MRI stains. These colors could be completely separated because the 129Xe chemical shift differentiation between any two MOFs was over 9 ppm.

We carefully investigated the relationship between the MOF pore structure and the resulting 129Xe MR signals, expecting to find laws that might help us explore more types of ultrasensitive MRI contrast agents. The pore size was expected to be one of the important factors that considerably affect the exchange rate of 129Xe atoms. As anticipated, the exchange rates of 129Xe in IRMOF-1, IRMOF-8, and IRMOF-10 increased with increasing pore size. However, the variation in relevant chemical shifts did not show a similar trend. The pore structure was mimicked, and the charge of the system was calculated. The results showed that the geometric structure and the number of atoms combined to act on the charge of each atom, which led to dispersed chemical shifts (IRMOF-1 > IRMOF-10 > IRMOF-8).

In conclusion, we successfully explored a new type of nanocage that circumvents the difficulty of fabricating 129Xe host cages and can be used as an ultrasensitive MRI stain with three individual colors. This approach may serve as a new strategy to analyze complex mixtures by combining the advantages of modifiable MOFs and ultrasensitive MRI without depth limitations. Numerous studies are expected to be conducted in the future, and they include but are not limited to the following. (1) Additional pore structures can be designed and fabricated by replacing organic links and/or metals, which may provide additional colors for ultrasensitive MRI. (2) The designed MOFs produced MR signals upfield of soluble free 129Xe atoms; other types of MOFs, which may lead to signals downfield, could be explored by utilizing the shielding electron effect. (3) The ultrasensitive MRI signal may be enhanced by improving the dispersity of MOF nanoparticles. (4) Real biological samples could be detected by introducing targeting groups. (5) Insoluble MOFs could be prepared in the form of spray and then inhaled for lung imaging.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91859206, 81625011, 81871453, 21921004, and 81825012), National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0700400), and Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, CAS (ZDBS-LY-JSC004). X. Zhou acknowledges the support from the Tencent Foundation through the XPLORER PRIZE.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Synthetic procedures, characterization of materials, and detailed technical information. See DOI: 10.1039/d0sc06969h

Notes and references

- Kim D. Park S. Y. Multicolor Fluorescence Photoswitching: Color-Correlated versus Color-Specific Switching. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018;6:1800678. doi: 10.1002/adom.201800678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra K. Stankevych M. Fuenzalida-Werner J. P. Grassmann S. Gujrati V. Huang Y. Klemm U. Buchholz V. R. Ntziachristos V. Stiell A. C. Multiplexed whole-animal imaging with reversibly switchable optoacoustic proteins. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:24. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz6293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. Liu H. Liu J. Haley K. N. Treadway J. A. Larson J. P. Ge N. Peale F. Bruchez M. P. Multicolor Liposome Mixtures for Selective and Selectable Cargo Release. Nano Lett. 2018;18:1331–1336. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b05025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviv T. Kim B. B. Chu J. Lam A. J. Lin M. Z. Yasuda R. Simultaneous dual-color fluorescence lifetime imaging with novel red-shifted fluorescent proteins. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:989–992. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutu D. L. Kokkaliaris K. D. Kunz L. Schroeder T. Multicolor quantitative confocal imaging cytometry. Nat. Methods. 2018;15:39–46. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collot M. Fam T. K. Ashokkumar P. Faklaris O. Galli T. Danglot L. Klymchenko A. S. Ultrabright and Fluorogenic Probes for Multicolor Imaging and Tracking of Lipid Droplets in Cells and Tissues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:5401–5411. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Pan C. Zhu Y. Zhao L. He H. Liu X. Qiu J. Achieving Thermo-Mechano-Opto-Responsive Bitemporal Colorful Luminescence via Multiplexing of Dual Lanthanides in Piezoelectric Particles and its Multidimensional Anticounterfeiting. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1804644. doi: 10.1002/adma.201804644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D. Lu F. Wang J. Hu W. Cao X. M. Ma X. Tian H. Amorphous Metal-Free Room-Temperature Phosphorescent Small Molecules with Multicolor Photoluminescence via a Host–Guest and Dual-Emission Strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:1916–1923. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitta N. Iino T. Isozaki A. Yamagishi M. Kitahama Y. Sakuma S. Suzuki Y. Tezuka H. Oikawa M. Arai F. Asai T. Deng D. Fukuzawa H. Hase M. Hasunuma T. Hayakawa T. Hiraki K. Hiramatsu K. Hoshino Y. Inaba M. Inoue Y. Ito T. Kajikawa M. Karakawa H. Kasai Y. Kato Y. Kobayashi H. Lei C. Matsusaka S. Mikami H. Nakagawa A. Numata K. Ota T. Sekiya T. Shiba K. Shirasaki Y. Suzuki N. Tanaka S. Ueno S. Watarai H. Yamano T. Yazawa M. Yonamine Y. Carlo D. Hosokawa Y. Uemura S. Sugimura T. Ozeki Y. Goda K. Goda K. Raman image-activated cell sorting. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3452. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17285-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery D. Long H. Meersmann T. Grandinetti P. J. Reven L. Pines A. High-field NMR of adsorbed xenon polarized by laser pumping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991;66:584. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.66.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo D. Xu X. Li Y. Tang J. A. Zhang J. Zijl P. C. M. Liu G. Detection and Quantification of Hydrogen Peroxide in Aqueous Solutions Using Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer. Anal. Chem. 2017;89:7758–7764. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J. Payen J. F. Wilson D. A. Traystman R. J. Zijl P. C. M. Using the amide proton signals of intracellular proteins and peptides to detect pH effects in MRI. Nat. Med. 2003;9:1085–1090. doi: 10.1038/nm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y. Zhang J. Qi X. Li S. Liu G. Siddhanta S. Barman I. Song X. McMahon M. T. Bulte J. W. M. Furin-mediated intracellular self-assembly of olsalazine nanoparticles for enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and tumor therapy. Nat. Mater. 2019;18:1376–1383. doi: 10.1038/s41563-019-0503-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo L. D. L. Bartoli A. Consolino L. Bardini P. Arena F. Schwaiger M. Aime S. In Vivo Imaging of Tumor Metabolism and Acidosis by Combining PET and MRI-CEST pH Imaging. Cancer Res. 2016;76:6463–6470. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. Yuan Y. Li S. Zeng Q. Guo Q. Liu N. Yang M. Yang Y. Liu M. McMahon M. T. Zhou X. Free-Base Porphyrins as CEST MRI Contrast Agents with Highly Upfield Shifted Labile Protons. Magn. Reson. Med. 2019;82:577–585. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert M. S. Cates G. D. Driehuys B. Happer W. Sam B. Springer J. C. S. Wishnia A. Biological magnetic resonance imaging using laser-polarized 129Xe. Nature. 1994;370:199–201. doi: 10.1038/370199a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. Graziani D. Pines A. Hyperpolarized Xenon NMR and MRI Signal Amplification by Gas Extraction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:16903–16906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909147106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matin T. N. Rahman N. Nickol A. H. Chen M. Xu X. Stewart N. J. Doel T. Grau V. Wild J. M. Gleeson F. V. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Lobar Analysis with Hyperpolarized Xe-129 MR Imaging. Radiology. 2017;282:857–868. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016152299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkup L. L. Myers K. El-Bietar J. Nelson A. Willmering M. M. Grimley M. Davies S. M. Towe C. Woods J. C. Xenon-129 MRI detects ventilation deficits in paediatric stem cell transplant patients unable to perform spirometry. Eur. Respir. J. 2019;53:1801779. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01779-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner L. He M. Virgincar R. S. Heacock T. Kaushik S. S. Freemann M. S. McAdams H. P. Kraft M. Driehuys B. Hyperpolarized, 129Xenon Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Quantify Regional Ventilation Differences in Mild to Moderate Asthma A Prospective Comparison Between Semiautomated Ventilation Defect Percentage Calculation and Pulmonary Function Tests. Invest. Radiol. 2017;52:120–127. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. Zhao X. Wang Y. Lou X. Chen S. Deng H. Shi L. Xie J. Tang D. Zhao J. Bouchard L.-S. Xia L. Zhou X. Damaged Lung Gas-Exchange Function of Discharged COVID-19 Patients Detected by Hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI. Sci. Adv. 2021;7:eabc8180. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc8180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driehuys B. Cofer G. P. Pollaro J. Mackel J. B. Hedlund L. W. Johnson G. A. Imaging alveolar-capillary gas transfer using hyperpolarized Xe-129 MRI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:18278–18283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608458103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loza L. A. Kadlecek S. J. Pourfathi M. Hamedani H. Duncan I. F. Ruppert K. Rizi R. R. Quantification of Ventilation and Gas Uptake in Free-Breathing Mice with Hyperpolarized Xe-129 MRI. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2019;38:2081–2091. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2019.2911293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruppert K. Brookeman J. R. Hagspiel III K. D. Mugler J. P. Probing lung physiology with xenon polarization transfer contrast (XTC) Magn. Reson. Med. 2009;44:349–357. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200009)44:3<349::AID-MRM2>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao M. R. Stewart N. J. Griffiths P. D. Norquay G. Wild J. M. Imaging Human Brain Perfusion with Inhaled Hyperpolarized Xe-129 MR Imaging. Radiology. 2017;286:659–665. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017162881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. Zhang Z. Zhong J. Ruan W. Han Y. Sun X. Ye C. Zhou X. Oxygen-Dependent Hyperpolarized 129Xe Brain MR. NMR Biomed. 2016;29:220–225. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunth M. Witte C. Hennig A. Schröder L. Identification, classification, and signal amplification capabilities of high-turnover gas binding hosts in ultra-sensitive NMR. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:6069–6075. doi: 10.1039/C5SC01400J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y. Guo Q. Zhang X. Jiang W. Ye C. Zhou X. Silica Nanoparticle Coated Perfluorooctyl Bromide for Ultrasensitive MRI. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2020;8:5014–5018. doi: 10.1039/D0TB00484G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Dmochowski I. J. An Expanded Palette of Xenon-129 NMR Biosensors. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016;49:2179–2187. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q. Bie B. Guo Q. Yuan Y. Han Q. Han X. Chen M. Zhang X. Yang Y. Liu M. Deng H. Zhou X. Hyperpolarized Xe NMR Signal Advancement by Metal-organic Framework Entrapment in Aqueous Solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117:17558–17563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004121117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens T. K. Ramirez R. M. Pines A. Nanoemulsion Contrast Agents with Sub-picomolar Sensitivity for Xenon NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:9576–9579. doi: 10.1021/ja402885q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mynar J. L. Lowery T. J. Wemmer D. E. Pines A. FreÂchet J. M. J. Xenon biosensor amplification via dendrimer-cage supramolecular constructs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:6334–6335. doi: 10.1021/ja061735s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Roose B. W. Palovcak E. J. Carnevale V. Dmochowski I. J. A. Genetically Encoded beta-Lactamase Reporter for Ultrasensitive Xe-129 NMR in Mammalian Cells. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:8984–8987. doi: 10.1002/anie.201604055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro M. G. Ramirez R. M. Sperling L. J. Sun G. Sun J. Pines A. Schaffer D. V. Bajaj V. S. Genetically encoded reporters for hyperpolarized xenon magnetic resonance imaging. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:630–635. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmanan A. Lu G. J. Farhadi A. Nety S. P. Kunth M. Lee-Gosselin A. Maresca D. Bourdeau R. W. Yin M. Yan J. Preparation of biogenic gas vesicle nanostructures for use as contrast agents for ultrasound and MRI. Nat. Protoc. 2017;12:2050–2080. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P. Ronson T. K. Greenfield J. L. Brotin T. Berthault P. Leonce E. Zhu J. Xu L. Nitschke J. R. Enantiopure [Cs+/Xe subset of Cryptophane] subset of (Fe4L4)-L-II Hierarchical Superstructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:8339–8345. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b02866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild R. M. Joseph A. I. Holman K. T. Fogarty H. A. Brotin T. Dutasta J. Boutin C. Huber G. Berthault P. A Water-Soluble Xe@cryptophane-111 Complex Exhibits Very High Thermodynamic Stability and a Peculiar 129Xe NMR Chemical Shift. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132(44):15505–15507. doi: 10.1021/ja1071515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber G. Beguin L. Desvaux H. Brotin T. Fogarty H. A. Dutasta J. Berthault P. Cryptophane-Xenon Complexes in Organic Solvents Observed through NMR Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2008;112:11363–11372. doi: 10.1021/jp807425t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K. Zemerov S. D. Parra S. H. Kikkawa J. M. Dmochowski I. J. Paramagnetic Organocobalt Capsule Revealing Xenon Host−Guest Chemistry. Inorg. Chem. 2020;19:13831–13844. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b03634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K. Zemerov S. D. Carroll P. J. Dmochowski I. J. Paramagnetic Shifts and Guest Exchange Kinetics in ConFe4–n Metal–Organic Capsules. Inorg. Chem. 2020;59(17):12758–12767. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c01816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roukala J. Zhu J. Giri C. Rissanen K. Lantto P. Telkki V. V. Encapsulation of Xenon by a Self-Assembled Fe4L6 Metallosupramolecular Cage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137(7):2464–2467. doi: 10.1021/ja5130176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q. Guo Q. Yuan Y. Yang Y. Zhang B. Ren L. Zhang X. Luo Q. Liu M. Bouchard L.-S. Zhou X. Mitochondria Targeted and Intracellular Biothiol Triggered Hyperpolarized 129Xe Magnetofluorescent Biosensor. Anal. Chem. 2017;89:2288–2295. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber A. G. Brotin T. Dubois L. Desvaux H. Dutasta J.-P. Berthault P. Water soluble cryptophanes showing unprecedented affinity for xenon: Candidates as NMR-based biosensors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:6239–6246. doi: 10.1021/ja060266r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthault P. Bogaert-Buchmann A. Desvaux H. Huber G. Boulard Y. Sensitivity and Multiplexing Capabilities of MRI Based on Polarized Xe-129 Biosensors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16456–16457. doi: 10.1021/ja805274u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klippel S. Freund C. Schroder L. Multichannel MRI Labeling of Mammalian Cells by Switchable Nanocarriers for Hyperpolarized Xenon. Nano Lett. 2014;14:5721–572628. doi: 10.1021/nl502498w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanikel N. Prévot M. S. Yaghi O. M. MOF water harvesters. MOF water harvesters. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020;15:348–355. doi: 10.1038/s41565-020-0673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y. Huang H. Zhang Y. Kang C. Chen S. Song L. Liu D. Zhong C. A versatile MOF-based trap for heavy metal ion capture and dispersion. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:187. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02600-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang S. Zhu Q. Xu Q. Nanomaterials derived from metal-organic frameworks. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018;3:17075. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2017.75. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q. Xiong P. Liu J. Xie Z. Wang Q. Yang X. Hu E. Cao Y. Sun J. Xu Y. Chen L. A Redox-Active 2D Metal-Organic Framework for Efficient Lithium Storage with Extraordinary High Capacity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020;59:5273–5277. doi: 10.1002/anie.201914395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X. Liang S. Cai X. Huang S. Cheng Z. Shi Y. Pang M. Ma P. Lin J. Yolk–Shell Structured Au Nanostar@Metal–Organic Framework for Synergistic Chemo-photothermal Therapy in the Second Near-Infrared Window. Nano Lett. 2019;19(10):6772–6780. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b01716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Wu W. Liu J. Manghnani P. N. Hu F. Ma D. Teh C. Wang B. Liu B. Cancer-Cell-Activated Photodynamic Therapy Assisted ss Cu(II)-Based Metal–Organic Framework. ACS Nano. 2019;13:6879–6890. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b01665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee D. Cairns A. J. Liu J. Motkuri R. K. Nune S. K. Fernandez C. A. Krishna R. Strachan D. M. Thallapally P. K. Potential of Metal-Organic Frameworks for Separation of Xenon and Krypton. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48(2):211–219. doi: 10.1021/ar5003126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trepte K. Schaber J. Schwalbe S. Drache F. Senkovska I. Kaskel S. Kortus J. Brunnerb E. Seifert G. The origin of the measured chemical shift of 129Xe in UiO-66 and UiO-67 revealed by DFT investigations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19:10020–10027. doi: 10.1039/C7CP00852J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasaki Y. Supran G. J. Bawendi M. G. Bulović V. Emergence of colloidal quantum-dot light-emitting technologies. Nat. Photonics. 2013;7:13–23. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2012.328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. Chen Y. Xu X. Zhang J. Xiang G. He W. Wang X. Well-Defined Metal–Organic Framework Hollow Nanocages. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:429–433. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddaoudi M. Kim J. Rosi N. Vodak D. Wachter J. O'Keeffe M. Yaghi O. M. Systematic Design of Pore Size and Functionality in Isoreticular MOFs and Their Application in Methane Storage. Science. 2002;295:469–472. doi: 10.1126/science.1067208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunth M. Lu G. J. Witte C. Shapiro M. G. Schröder L. Protein Nanostructures Produce Self-Adjusting Hyperpolarized Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast through Physical Gas Partitioning. ACS Nano. 2018;12:10939–10948. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b04222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taratula O. Hill P. A. Khan N. S. Carroll P. J. Dmochowski I. J. Crystallographic observation of ‘induced fit’ in a cryptophane host-guest model system. Nat. Commun. 2010;1:148. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. Har-el Y. McMahon M. T. Zhou J. Sherry A. D. Sgouros G. Bulte J. W. M. Zijl P. C. M. Size-Induced Enhancement of Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) Contrast in Liposomes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5178–5184. doi: 10.1021/ja710159q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albanese A. Tang P. S. Chan W. C. W. The Effect of Nanoparticle Size, Shape, and Surface Chemistry on Biological Systems. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2012;14:1–16. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071811-150124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terskikh V. V. Moudrakovski I. L. Breeze S. R. Lang S. Ratcliffe C. I. Ripmeester J. A. Sayari A. A General Correlation for the 129Xe NMR Chemical Shift–Pore Size Relationship in Porous Silica-Based Materials. Langmuir. 2002;18(15):5653–5656. doi: 10.1021/la025714x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraissard J., Chapter 1: Xenon as a Probe Atom: Introduction, Characteristics, Investigation of Microporous Solids, in Hyperpolarized Xenon-129 Magnetic Resonance: Concepts, Production, Techniques and Applications, 2015, pp. 1–15 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.