Abstract

Purpose

Nurses’ behaviors are largely influenced by their managers’ leadership style. The relationships between ethical leadership, trust, psychological well-being, and organizational citizenship behaviors have rarely been investigated in nursing studies. The current study attempted to examine the relationships between perceived ethical leadership, trust, psychological health, and nurses’ organizational citizenship behaviors towards their patients in the context of Chinese hospitals.

Methods

This research adopted a cross-sectional research design. Participants were 495 nurses solicited from six hospitals in China. Hayes’s PROCESS and SPSS 22 were employed to analyze the data.

Results

This study demonstrated ethical leadership perceived by nurses is positively associated with trust in management and psychological well-being. Trust in management is also positively associated with nurses’ organizational citizenship behaviors. The indirect effects of perceived ethical leadership on organizational citizenship behaviors through trust in management and psychological well-being were statically significant.

Conclusion

This study adds value to the literature by revealing ethical leadership boosts nurses’ trust in leadership and their psychological well-being, resulting in more organizational citizenship behaviors towards patients in the context of the Chinese hospitals. It is suggested that the hospital management creates an environment in which all members are treated fairly to boost nurses’ psychological health and improve their service quality toward patients’ satisfaction.

Keywords: perceived ethical leadership, trust in management, organizational citizenship behavior, psychological health, nursing, Chinese hospitals, COVID-19

Introduction

Working on the front line of health care, nurses play an essential role in ensuring high-quality patient care service. However, they mostly work in a stressful environment.1 Moreover, as a profession, nursing is facing challenges worldwide such as staff shortage, heavy workload, ambiguous responsibilities, and high risks.2 These challenges, together with the working conditions negatively influence nurses’ psychological well-being.3 The situation became more severe for Chinese nurses during the COVID 19 pandemic as they had to suffer from heavy daily workload and stress, which not only directly impacted their physical and psychological health but also influenced the health care quality.4 Given the service-intensive nature and frequent interaction with patients, nurses are required to build a trusting relationship with their clients, which entails nurses performing voluntary behavior beyond job descriptions usually called organizational citizenship behavior (OCB).5

In this study, we are interested in OCB towards the customer which refers to employees’ voluntary commitment towards their customers within an organization that goes above and beyond what is required in the job description.6 OCB towards the customer is important to organizations because it is associated with employees’ service quality provided to the customer.5 Evidence has shown that employees’ willingness to perform OCBs increases customer satisfaction and service quality.7 At hospitals, patients are considered customers, and nurses function as a hub of communication between physicians and patients and/or their family members.8 Therefore, hospitals need to encourage nurses to exhibit OCBs towards patients in the workplace. For example, nurses are willing to work after normal working hours to help patients to solve problems without any complaints.

While OCB towards patients is a voluntary commitment to helping patients, nurses’ behaviors are also influenced by their supervisors’ or managers’ leadership style.9 For this reason, leadership was identified as one of the priority foci of the new agenda to guide nursing administration studies.10 While traditional leaders encourage employees to avoid loss and deviant behavior at work, ethical leaders tend to promote employees to focus on helping behavior.11 As a moral person, an ethical leader plays a significant role in improving employees’ concerns toward the organization.12 Ethical leadership is a new value-based leadership style defined as the demonstration and promotion of normatively appropriate conduct to the followers by the leaders through personal actions and interpersonal relationships.13 Mastracci14 argued that ethical leadership has three major ingredients: serving as an ethical role model, treating others fairly, and actively practicing ethics. Ethical leadership may also increase employees’ trust in management15 and psychological well-being.16 Trust in management is defined as the extent to which employees have positive expectations about the management’s intentions or behaviors especially with regards to their own situations.17 As a psychological term, psychological well-being is commonly defined as the overall effectiveness of people’s psychological functioning.18

The purpose of this study was to examine the mediating effects of trust in management and psychological well-being on the relationship between ethical leadership and organizational citizenship behaviors towards patients in the context of Chinese nursing. Specifically, research questions included (1) Are there any relationships between nurses’ perceived ethical leadership, trust in management, psychological well-being, and nurses’ patient-oriented OCB in Chinese hospitals? (2) Are the relationship between nurses’ perceived ethical leadership and patient-oriented OCB mediated by their trust in management and psychological well-being?

This study adds value to both nursing and leadership literature. First, despite the relationship between ethical leadership and OCB has been examined in the literature,19 the underlying mechanism through which ethical leadership influences OCB has not been fully understood20 and has been largely ignored in nursing studies.21 It remains unclear whether ethical leaders in the hospitals can promote nurses’ trust in their supervisors and psychological health, ultimately stimulating nurses’ OCB towards patients. Furthermore, the results of prior studies on the relationship between ethical leadership and psychological well-being were mixed. While some studies found that ethical leadership has a positive effect on employees’ psychological well-being,16 other research found their relationship to be negative.22 Therefore, we conducted this study to fill these research gaps in the nursing and leadership literature.

Theoretical Background

Social learning theory23 posits new behaviors can be acquired by observing and imitating others. In organizations, employees learn from role models by observation, imitation, and modeling.24 Ethical leaders demonstrate the commitment to ethical practices in the workplace and serve as ethical models for people around them.25 They have a higher level of ethical standards with integrity and veracity and discipline those who violate the ethical principles.26 They also care about their followers. The employees, in turn, will model their leaders’ behaviors. They most likely also show care and concern to colleges and go the extra mile to help their customers. Thus, ethical leaders can inspire and motivate employees to achieve higher work performance. In addition, leaders treat their followers fairly.27 Employees in turn will most likely involve in OCB behaviors.28 Increasing empirical evidence has shown that ethical leaders inspire employees to adopt OCBs in the workplace to help supervisors, fellow workers, and customers.29,30 In nursing, studies have documented that ethical leadership is related to nurses’ OCBs toward their patients in the workplace.31 However, the study results are mixed. While some confirmed that ethical leadership directly affects OCB towards patients,5,32 other studies concluded that such a relationship is not direct.33 We argue that ethical leadership perceived by nurses is positively associated with patient-oriented OCBs in Chinese hospitals. Thus, we propose that

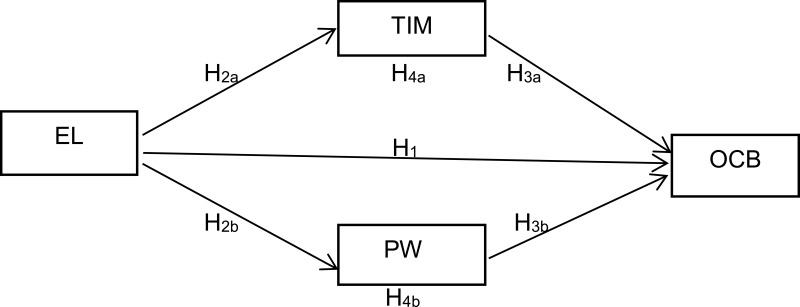

H1: Nurses’ perceived ethical leadership was positively associated with their patient-oriented OCBs.

Not only can ethical leaders inspire employees to display OCBs, but they also increase employees’ trust in management15 and psychological well-being.16 Social exchange theory holds that if employees perceive their leaders put their best interests at heart, followers are most likely to feel obliged to reciprocate the favor received.27 Ethical leaders believe in justice, care about their followers, and treat them with fairness and dignity. They are always honest, question unethical behavior, and create high-quality, trust-oriented relations with their followers.34 Such leaders can easily gain the trust and respect of their followers.27 Research has indicated that ethical leadership positively influences employees’ trust in management.35,36 In the context of hospitals, especially, a study conducted by Enwereuzor et al37 demonstrated that ethical leadership was positively related to trust in leaders. Furthermore, ethical leaders are perceived as ethical decision-makers, they always do their best to enhance their followers’ well-being and life quality.34 Evidence has shown that ethical leadership can reduce stress and stimulate a high-quality work environment.38,39 Thus, ethical leadership is a vital determinant of employees’ well-being in organizations. Based on the above reasoning and literature, we proposed the following two hypotheses:

H2a: Nurses’ perceived ethical leadership was positively related to their trust in management, and

H2b: Nurses’ perceived ethical leadership was positively associated with their psychological well-being;

Affective Event Theory (AET)40 proposes that positive emotions and attitudes that arise due to positive stimulus from leaders tend to result in positive work behavior in the workplace. As aforementioned, ethical leaders can stimulate employees to show trust towards leaders. These trusting employees will be encouraged to engage in extra-role behaviors. That is, when employees trust their leaders who are ethical and always do the right things, they are most likely to behave in accordance with what the leaders expect them to do for the benefit of the whole organization.41 Certainly, such behaviors include OCBs. In the literature, it was found that employees who trust their management are more likely to demonstrate OCBs toward others.42,43 Just as trust in leaders affects employees’ OCBs, employees’ psychological well-being might be OCB’s another predictor. As argued previously, employees’ mood and emotions influence their workplace behaviors. Employees with positive psychological well-being tend to involve in more prosocial behaviors.44 However, performing OCB entails employees doing extra work and thus adds to their personal workload, impeding employees’ task progress.45 Psychological well-being can serve as adding value in aiding the acquisition and conservation of desirable personal and job resources to incentivize employees’ OCBs.46 In actuality, empirical evidence has demonstrated that psychological well-being is positively associated with employee performance47 and OCB.48 Based on the theory and empirical evidence, we proposed the subsequent hypotheses.

H3a: Nurses’ trust in management was positively associated with their OCBs towards patients, and

H3b: Nurses’ psychological well-being was positively related to their OCBs towards patients.

Perceived ethical leadership is hypothesized to associate with nurses’ trust in leaders and their psychological well-being. Trust in leaders and psychological well-being, in turn, are related to employees’ OCBs toward patients. We further proposed that nurses’ trust in management and psychological well-being act as mediators that transmit the effect of perceived ethical leadership on nurses’ OCBs toward their patients. Thus, we hypothesized that

H4a: Nurses’ trust in management mediated the association between their perceived ethical leadership and OCBs towards patients.

H4b: Nurses’ psychological well-being mediated the association between their perceived ethical leadership and OCBs towards patients.

The conceptual model is presented in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

Abbreviations: EL, ethical leadership; TIM, trust in management; PW, psychological well-being; OCB, organizational citizenship behavior.

The next sections were structured as follows. First, we described the research participants and study setting. Then, we outlined data collection processes, followed by measurement instruments and data analysis techniques. Subsequently, we presented research results, including descriptive statistics and hypotheses testing. We concluded with a discussion of the results, limitations and future research, and practical implications.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Study Setting

This study aims to investigate the relationships between nurses’ perceived ethical leadership, trust in management, psychological well-being, and nurses’ patient-oriented OCB in Chinese hospitals. We adopted a cross-sectional design. They were solicited from six hospitals in Guizhou Province located in the southwestern part of China between August 9 and September 23, 2019. The six hospitals were randomly chosen. Prior to data collection, approvals were obtained from each hospital. The head nurses of each hospital assisted the researchers to distribute the survey questionnaires to 1968 nurses using WeChat. Only those with more than six-month clinical experience were eligible to participate. They were asked to complete survey instruments of ethical leadership, trust in management, psychological well-being, and patient-oriented OCB in one month. A total of 495 nurses who participated provided valid data with a response rate of 25.2%. Among these 495 nurses, a vast majority of them were women (91.11%), and there were only 44 male nurses (8.89%). Nearly half of the nurses were in their 20s (47.1%). A total of 185 nurses (37.4%) held college degrees and 211 nurses (42.6%) reported that they earned 4000–6000 CNY per month. In terms of tenure, 341 participants (68.9%) worked in their hospital for over 5 years.

Data Collection

Before the survey, we obtained permission from the management of six hospitals. Nursing managers helped to distribute survey questionnaires via WeChat. Two weeks after the initial WeChat text, a reminder was sent to nurses asking them to complete the questionnaires. Nurses were told their participation in this study was completely voluntary and their anonymity and confidentiality were protected. Furthermore, a pilot study was conducted involving 40 nurses to ensure that the questions are clear, specific, and concise. Minor changes were subsequently made according to their comments and suggestions. Using G*Power, we computed the minimum sample size to be 187. There were 495 participating nurses in this study. Therefore, the sample size was sufficient.

Measures

The survey consisted of two components. The first component covered nurses’ demographic information. The second part asked participants to rate all the items of ethical leadership, trust in management, psychological well-being, and patient-oriented OCB based on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Some questions were negatively worded to balance positive and negative items to mitigate the effect of common method bias (CMB).

Perceived Ethical Leadership

Perceived ethical leadership was measured using a 10-item measurement scale developed by Brown, Trevino, and Harrison.13 The nurses rated each item based on their perception of ethical leadership exhibited by their supervisors. Two sample items are “My manager has the best interests of nurses in mind” and “My manager discusses business ethics or values with us”. Cronbach’s alpha was α = 0.94.

Trust in Management

A 6-item scale developed by McAllister49 was selected to measure participants’ trust in management. A sample item was “If I shared my problems with my manager, I know he or she would respond constructively and caringly.” Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.93.

Psychological Well-Being

Psychological well-being was evaluated by The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire developed by Hills and Argyle.50 This scale consists of 18 items. Two sample items included “I find most things amusing” and “I have a particular sense of meaning and purpose in my life”. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.92.

Patient-Oriented OCB

Patient-oriented OCB was measured by using a 7-item scale developed by Dimitriades.51 A sample item was “I make innovative suggestions to improve customer service.” Cronbach’s alpha was α = 0.92 for this scale.

We collected demographic data such as gender, age, education, income, and tenure. It was found in prior studies that these variables were associated with OCB.52,53

Data Screening and Common Method Biases Issue

Data screening was performed to ensure the data is clean and ready to be used to conduct further statistical analyses. No missing data nor outliers were detected. The skewness indices of all the data were all within the range of −1 and +1 and the absolute values of kurtosis indices were lower than 3, indicating the data followed a normal distribution pattern.54 In addition, no evidence showed that multi-collinearity was a major issue because all the values of variance inflation factors (VIF) indicating collinearity were below 3. Multi-collinearity test detects whether two explanatory variables are highly linearly related. With the VIF scores under 3.3, the data could be deemed free of CMB.55

Statistical Analysis

SPSS version 22 was used to calculate means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations in the research. Hayes’s56 PROCESS with SPSS was employed to estimate the relationships between ethical leadership, trust in management, psychological well-being, and patient-oriented OCB. PROCESS is widely adopted in the social, business, and health sciences to examine direct and indirect effects in single and multiple mediator models. This study attempted to test the direct effect of perceived ethical leadership on nurses’ patient-oriented OCB, as well as the indirect effects through trust in management and psychological well-being. Therefore, PROCESS was deemed an appropriate tool to test the proposed hypotheses.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Inter-Correlations

Descriptive information such as means and standard deviations of the variables, as well as inter-correlations between them, are presented in Table 1. Patient-oriented OCB (M = 3.78) and psychological well-being (M = 3.75) had higher means than perceived ethical leadership (M = 3.41) and trust in management (M = 3.43). However, perceived ethical leadership (SD = 0.98) and trust in management (SD = 1.05) had a higher standard deviation than psychological well-being (SD = 0.88) and patient-oriented OCB (SD = 0.79). As expected, ethical leadership, trust in management, psychological well-being, and OCB were all correlated (see Table 1). For control variables, only age and tenure were significantly correlated with patient-oriented OCB.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Interrelations of the Variables

| Variable | M | SD | Gen | Age | Edu | Sal | Ten | EL | TIM | PW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gen | 1.91 | 0.29 | ||||||||

| Age | 32.50 | 7.21 | 0.06 | |||||||

| Edu | 14.66 | 4.55 | 0.00 | 0.08 | ||||||

| Sal | 6439.69 | 4139.76 | 0.13** | 0.28** | 0.05 | |||||

| Ten | 8.91 | 7.43 | 0.10* | 0.83** | 0.04 | 0.28** | ||||

| EL | 3.41 | 0.98 | 0.05 | -0.00 | -0.07 | -0.04 | 0.06 | |||

| TIM | 3.43 | 1.05 | 0.04 | −.01 | −.06 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.86** | ||

| PW | 3.75 | 0.88 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −.01 | −.04 | 0.05 | 0.56 ** | 0.61 ** | |

| OCB | 3.78 | 0.79 | 0.04 | 0.16** | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.20** | 0.49 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.57** |

Notes: N = 495; M denotes mean; SD signifies standardized deviation; * p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Abbreviations: Gen, gender; Edu, education; Sal, salary; Ten, tenure; EL, perceived ethical leadership; TIM, trust in management; PW, psychological well-being; OCB, patient-oriented OCB.

Hypothesis Testing

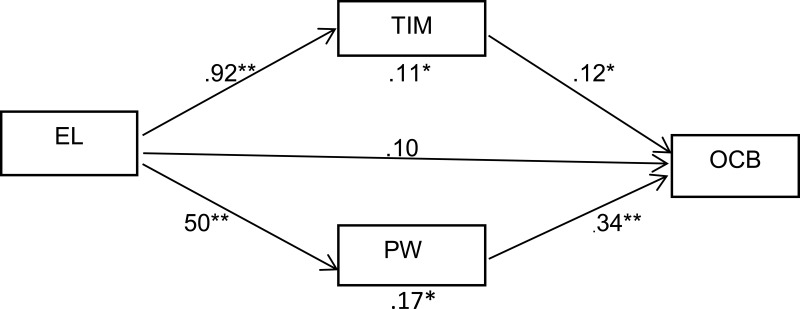

PROCESS with SPSS was employed to test the relationships and indirect effects hypothesized. Hypothesis testing was presented in Figure 2. Bootstrapping with 5000 replacements was used to more accurately estimate the standard errors and confidence intervals. Table 2 presented the bootstrapping results. As indicated in Table 2, the path coefficient from perceived ethical leadership to OCB is 0.10 (t = 1.86, p = 0.064), indicating there is no significant direct effect of ethical leadership on nurses’ OCB towards patients. Thus, H1 was rejected.

Figure 2.

Hypothesis testing.

Notes: * p < 0.05; ** p <0.01.

Abbreviations: EL, ethical leadership; TIM, Trust in management; PW, Psychological well-being; OCB, Organizational citizenship behavior.

Table 2.

Study Results for Mediation Model

| Hypothesis | Coefficient | SE | t | p | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: EL OCB | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1.86 | 0.064 | Rejected |

| H2a: EL TIM | 0.92 | 0.02 | 36.81 | < 0.01 | Supported |

| H2b: EL PW | 0.50 | 0.03 | 14.72 | < 0.01 | Supported |

| H3a: TIM OCB | 0.12 | 0.05 | 2.31 | 0.021 | Supported |

| H3b: PW OCB | 0.34 | 0.04 | 8.63 | < 0.01 | Supported |

| Indirect Effect | Boot SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | ||

| H4a: EL TIM OCB | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.21 | Supported |

| H4a: EL PW OCB | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.22 | Supported |

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; EL, perceived ethical leadership; TIM, trust in management; PW, psychological well-being; OCB, patient-oriented OCB.

Hypothesis 2a suggested that perceived ethical leadership was positively associated with trust in management. As shown in Table 2, the path coefficient from perceived ethical leadership to trust in management was 0.92 (t = 36.81, p < 0.01). Therefore, H2 was confirmed. The association between trust in management and OCB was also significant (β=0.12, t = 2.31, p = 0.021). Thus, H3a was supported. The results also showed that the indirect effect of perceived ethical leadership on OCB through trust in management was significant with an effect size of 0.11 and 95% bootstrapping confidence interval [0.01, 0.21]. H4a was supported.

Hypothesis 2b suggested that ethical leadership perceived by nurses positively associated with psychological well-being. The path coefficient between perceived ethical leadership and psychological well-being was 0.50, (t = 14.721, p < 0.01) (see Table 2). Therefore, H2b was confirmed. The association between psychological well-being and OCB was also significant with a path coefficient of 0.34, t = 8.63 (p < 0.01). Thus, H3b was confirmed. It was also shown that the indirect effect of perceived ethical leadership on OCB through psychological well-being was significant with an effect size of 0.17 and 95% bootstrapping confidence interval [0.12, 0.22]. H4b was supported.

Discussion

This study focused on the relationships between perceived ethical leadership, trust in management, psychological well-being, and nurses’ OCB towards their patients. We especially examined the mediating effect of trust in management and psychological well-being between ethical leadership and nurses’ OCB. The results lend support to most of these relationships. As leaders play a crucial role in influencing followers’ attitudes and behaviors, ethical leadership is vital in creating a trusting environment and boosting employees’ psychological well-being, resulting in nurses’ voluntary behaviors to help patients.

Perceived ethical leadership is positively related to nurses’ trust in management. Nurses who perceived a high level of ethical leadership are more likely to trust their supervisors or managers. They also tend to be more psychologically healthy. This finding supports the work of Engelbrecht, Heine, and Mahembe.57 Perceived ethical leadership is positively related to nurses’ psychological well-being. Nurses who perceive their manager to be ethical tend to be more psychologically healthy. This result agrees with the finding of Teimouri, Hosseini, and Ardeshiri.16 However, this result does not support the study of Yang22 who found that ethical leadership has a negative direct effect on employee well-being. Ethical leaders in hospitals concern about the best interests of the nurses. These behaviors particularly enhance their image as trustworthy in the nurses’ minds. Further, ethical nursing managers maintain dignity and show a servant attitude toward nurses. Therefore, nurses are more likely to have a high level of psychological well-being. This study also demonstrated that nurses’ trust in management and psychological health in turn, is positively associated with their OCBs to patients. The positive relationships are consistent with the finding of a study by Barzoki and Rezaei.58 Ethical leaders are considered trustworthy. They create a trusting and healthy environment wherein nurses trust others and feel psychologically healthy. When nurses are asked to perform certain tasks beyond the job description, they are more likely to “go the extra mile” to serve their patients without reluctance.

We failed to find the direct relationship between perceived ethical leadership and nurse’s OCB. This result is consistent with the conclusion of Jeon et al’s33 study. However, indirect associations between them through both trust in management and psychological health are significant. This is to say the effect of ethical leadership on OCB is transmitted through trust and psychological health. Ethical leaders are more likely to increase nurses’ trust and boost their psychological health, thus influencing nurses to do extra work to help patients. Since ethical leaders act as role models and are perceived as caring about employees’ wellbeing, employees would mimic the ethical behaviors and reciprocate the treatment in the workplace to the leaders, colleagues, and patients.

Limitations and Future Research

There are several limitations in this study. The first limitation relates to the use of a convenience sample of hospital nurses in a less developed province Guizhou. Therefore, the conclusion may not apply to other parts of China, especially more developed areas, or hospitals worldwide. Future research could consider using random sampling or stratified sampling to collect data that would be more representative of the nurse population. Next, we did not obtain group or department level data from our sample, therefore hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) was not employed in this study. Lastly, we collected the data only from nurses and did not use other sources such as colleagues or patients. Although we used the necessary methods to attempt to reduce the effect of CMB, the estimated relationships might still be biased to some extent. Future research could further minimize such biases by using other procedural and statistical remedies recommended by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff59 such as temporal or proximal separation between predictor and criterion.

Practical Implications

The findings of this study have several implications for hospital nurse leaders and managers. First, the demonstrated importance of ethical leadership suggests that nurse leaders need to emphasize their responsibilities to their nurses, define nursing values, and develop a nursing administration code of ethics. They need to protect and maintain work value by rewarding those who adhere to the ethical principles and disciplining those who breach. For nursing leaders and management, setting a good example and caring about nurses are critical in bolstering supporting relationships among all members of the nursing community. Second, it is also the hospital management’s responsibility to create an environment in which all members are treated fairly and with trust and respect. Role modeling is vital and nursing leaders need to be honest, supportive, and consistent. Third, psychologically healthy nurses are important to hospitals and health care organizations. They are competitive resources that would contribute to the sustainable development of hospitals and healthcare organizations. Keeping and maintaining nurses’ well-being can prevent large issues from developing in hospitals. It is important to establish human resource policies and implement practices following ethical leadership principles.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that perceived ethical leadership is positively related to their trust in management and psychological health among Chinese nurses in hospitals. Also, both nurses’ trust in management and psychological health mediate the relationship between perceived ethical leadership and their OCB behaviors towards patients. Ethical nurse leaders care about nurses’ wellbeing and practice ethical conduct in their interaction with their nurses. They also discipline those who violate ethical principles. Therefore, an environment is easily promoted in hospitals wherein nurses support each other and trust their supervisors. When hospital nurses trust their leaders and are psychologically healthy, more patient-oriented OCBs would occur in the workplace. This is to say that nurses are more likely to make extra efforts to serve their patients, contributing to increased patient satisfaction and nurses’ work performance. As such, hospitals will benefit and achieve their financial success. Nurse leaders need to create a trusting environment in the healthcare industry and in triggering nurses’ OCBs to serve their customers. Further, this study adds value to the existing nursing literature by reaffirming the relationships between ethical leadership, trust in management, psychological well-being, and nurses’ OCB towards patients in the Chinese hospitals.

Acknowledgment

The first two authors (Shaoping Qiu and Naizhu Huang) contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

Funding Statement

This study did not receive any funds from any institutions.

Abbreviations

EL, perceived ethical leadership; TIM, trust in management; PW, psychological well-being; OCB, organizational citizenship behavior; t, t- score; p, p-value; M, Mean; SD, standard deviation; CMB, common method bias.

Data Sharing Statement

Data are available upon request.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Committee of Ethics of Xiangnan University (No.CE2019-0121A). Participation in this study was voluntary. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured in this study. Before the survey, we obtained permission from the management of each hospital. An invitation letter appeared above the survey in which participants were told about the purpose of the survey. Informed consent was obtained from participants. This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

- 1.Huang H, Liu L, Yang S, Cui X, Zhang J, Wu H. Effects of job conditions, occupational stress, and emotional intelligence on chronic fatigue among Chinese nurses: a cross-sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manage. 2019;12:351. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S207283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun Y, Wang D, Han Z, Gao J, Zhu S, Zhang H. Disease prevention knowledge, anxiety, and professional identity during COVID-19 pandemic in nursing students in Zhengzhou, China. 2020;50:533–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato T. Coping with interpersonal stress and psychological distress at work: comparison of hospital nursing staff and salespeople. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2014;7:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie N, Qin Y, Wang T, Zeng Y, Deng X, Guan L. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among nurses in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qiu S, Dooley LM, Deng R, Li L. Does ethical leadership boost nurses’ patient‐oriented organizational citizenship behaviours? A cross‐sectional study. J Advan Nurs. 2020;76(7):1603–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Organ DW, Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature, Antecedents, and Consequences. SAGE; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Syed Naseeb Ullah S, Shahid J, Qadar Bakhsh B. Role of service quality and customer satisfaction in firm’s performance: evidence from Pakistan Hotel Industry. Pak J Commerce Soc Sci. 2018;12(1):167–182. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maier CB, Batenburg R, Birch S, Zander B, Elliott R, Busse R. Health workforce planning: which countries include nurse practitioners and physician assistants and to what effect? Health Policy (New York). 2018;122(10):1085–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Northouse PG. Leadership: Theory and Practice. 7th ed. SAGE Publications, Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott ES, Murphy LS, Warshawsky NE. Nursing Administration Research Priorities Findings From a Delphi Study. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2016;46(5):238–244. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neubert MJ, Kacmar KM, Carlson DS, Chonko LB, Roberts JA. Regulatory focus as a mediator of the influence of initiating structure and servant leadership on employee behavior. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(6):6. doi: 10.1037/a0012695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mo S, Shi J. Linking ethical leadership to employees’ organizational citizenship behavior: testing the multilevel mediation role of organizational concern. J Business Ethics. 2017;141(1):151–162. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown ME, Treviño LK, Harrison DA. Ethical Leadership: A Social Learning Perspective for Construct Development and Testing. United States: Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam; 2005:117. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mastracci S. Beginning nurses’ perceptions of ethical leadership in the shadow of Mid Staffs. Public Integrity. 2017;19(3):250–264. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoch JE, Bommer WH, Dulebohn JH, Wu D. Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. J Manage. 2018;44(2):501–529. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teimouri H, Hosseini SH, Ardeshiri A. The role of ethical leadership in employee psychological well-being (Case study: golsar Fars Company). J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2018;28(3):355–369. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao L, Janssen O, Shi K. Leader trust and employee voice: the moderating role of empowering leader behaviors. Leadersh Q. 2011;22(4):787–798. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright TA, Cropanzano R. Psychological well-being and job satisfaction as predictors of job performance. J Occup Health Psychol. 2000;5(1):84–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akanksha B, Can MA, Sandy G, Meta-analytic A. Review of ethical leadership outcomes and moderators. J Business Ethics. 2016;139(3):517–536. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raad Abdulkareem S, Tarik A. The influence of ethical leadership on academic employees’ organizational citizenship behavior and turnover intention: mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Manage Decision. 2019;57(3):583–605. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng TWH, Feldman DC. Ethical Leadership: Meta-Analytic Evidence of Criterion-Related and Incremental Validity. United States: APA AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION; 2015:948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang C. Does Ethical Leadership Lead to Happy Workers? A Study on the Impact of Ethical Leadership, Subjective Well-Being, and Life Happiness in the Chinese Culture. J Business Ethics. 2014;123(3):513–525. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bandura A, McClelland DC. Social Learning Theory. Vol. 1. Englewood cliffs Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blau PM. Exchange and Power in Social Life. [By] Peter M. Wiley; 1964. Blau. J. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallagher A, Tschudin V. Educating for ethical leadership. Nurse Educ Today. 2010;30(3):224–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makaroff KS, Storch J, Pauly B, Newton L. Searching for ethical leadership in nursing. Nurs Ethics. 2014;21(6):642–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown ME, Treviño LK, Harrison DA. Ethical leadership: a social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2005;97(2):117–134. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konovsky MA, Pugh SD. Citizenship behavior and social exchange. Acad Manage j. 1994;37(3):656–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerpott FH, Van Quaquebeke N, Schlamp S, Voelpel SC. An identity perspective on ethical leadership to explain organizational citizenship behavior: the interplay of follower moral identity and leader group prototypicality. J Business Ethics. 2019;156(4):1063–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ko C, Ma J, Kang M, AS English, MH Haney. How ethical leadership cultivates healthy guanxi to enhance OCB in China. Asia Pac J Human Resources. 2017;55(4):408–429. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiu S, Dooley LM, Deng R, Li L. Does ethical leadership boost nurses’ patient‐oriented organizational citizenship behaviours? A cross‐sectional study. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(7):1603–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aloustani S, Atashzadeh-Shoorideh F, Zagheri-Tafreshi M, Nasiri M, Barkhordari-Sharifabad M, Skerrett V. Association between ethical leadership, ethical climate and organizational citizenship behavior from nurses’ perspective: a descriptive correlational study. BMC Nurs. 2020;19(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeon SH, Park M, Choi K, Kim MK. An ethical leadership program for nursing unit managers. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;62:30–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Xu J, Tu Y, Lu X. Ethical leadership and subordinates’ occupational well-being: a multi-level examination in China. Soc Indic Res. 2014;116(3):823–842. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kihyun LEE. Ethical leadership and followers’ taking charge: trust in, and identification with, leader as mediators. Soc Behav Personality. 2016;44(11):1793–1802. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Javed B, Rawwas MY, Khandai S, Shahid K, Tayyeb HH. Ethical leadership, trust in leader and creativity: the mediated mechanism and an interacting effect. J Manage Organ. 2018;24(3):388–405. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enwereuzor IK, Adeyemi BA, Onyishi IE. Trust in leader as a pathway between ethical leadership and safety compliance. Leadership Health Serv. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmad MA. The effect of ethical leadership on management accountants’ performance: the mediating role of psychological well-being. Problems Perspectives Manage. 2019;17(2):228. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chughtai A, Byrne M, Flood B. Linking ethical leadership to employee well-being: the role of trust in supervisor. J Business Ethics. 2015;128(3):653–663. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiss HM, Cropanzano R Affective events theory: a theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. 1996.

- 41.Amir DA. The effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior: the role of trust in leader as a mediation and perceived organizational support as a moderation. J Leadership Organ. 2019;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiu S, Alizadeh A, Dooley LM, Zhang R. The effects of authentic leadership on trust in leaders, organizational citizenship behavior, and service quality in the Chinese hospitality industry. J Hosp Tourism Manage. 2019;40:77–87. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dirks KT, Ferrin DL. Trust in leadership: meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87:4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Devonish D. Emotional intelligence and job performance: the role of psychological well-being. Int J Workplace Health Manage. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bolino MC, Klotz AC, Turnley WH, Harvey J. Exploring the dark side of organizational citizenship behavior. J Organ Behav. 2013;34(4):542–559. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu J, Xie B, Chung B. Bridging the gap between affective well-being and organizational citizenship behavior: the role of work engagement and collectivist orientation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):4503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wright TA, Bonett DG. Role of Employee Coping and Performance in Voluntary Employee Withdrawal: A Research Refinement and Elaboration. Vol. v19. Sage Publications, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davila MC, Finkelstein MA. Organizational citizenship behavior and well-being: preliminary results. Int J Appl Psychol. 2013;3(3):45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 49.McAllister DJ. Affect-and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad Manage J. 1995;38(1):24–59. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hills P, Argyle M. The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: A Compact Scale for the Measurement of Psychological Well-Being. Great Britain: Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam.; 2002:1073. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dimitriades ZS. The influence of service climate and job involvement on customer-oriented organizational citizenship behavior in Greek service organizations: a survey. Employee Relations. 2007;29(5):469–491. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shih Yung C. A theoretical analysis of immigrant employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors in organizations. J Glob Mobil. 2018;6(2):209–225. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jessica Sze Yin H, Sanjaya SG, Kok WC, Nasreen K. Gender roles and customer organisational citizenship behaviour in emerging markets. GenderManage. 2017;32(8):503–517. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kock N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int J e-Collaboration (Ijec). 2015;11(4):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Andrew F. Hayes. Second. Second ed. ed, Guilford Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Amos SE, Gardielle H, Bright M. Integrity, ethical leadership, trust and work engagement. Leadership Organ Develop J. 2017;38(3):368–379. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barzoki AS, Rezaei A. Relationship between perceived organisational support, organisational citizenship behaviour, organisational trust and turnover intentions: an empirical case study. Int J Prod Qual Manage. 2017;21(3):273–299. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. United States: ANNUAL REVIEWS INC; 2012:539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]