Abstract

Amyloid transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis with polyneuropathy (PN) is a progressive, debilitating, systemic disease wherein transthyretin protein misfolds to form amyloid, which is deposited in the endoneurium. ATTR amyloidosis with PN is the most serious hereditary polyneuropathy of adult onset. It arises from a hereditary mutation in the TTR gene and may involve the heart as well as other organs. It is critical to identify and diagnose the disease earlier because treatments are available to help slow the progression of neuropathy. Early diagnosis is complicated, however, because presentation may vary and family history is not always known. Symptoms may be mistakenly attributed to other diseases such as chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP), idiopathic axonal polyneuropathy, lumbar spinal stenosis, and, more rarely, diabetic neuropathy and AL amyloidosis. In endemic countries (e.g., Portugal, Japan, Sweden, Brazil), ATTR amyloidosis with PN should be suspected in any patient who has length-dependent small-fiber PN with autonomic dysfunction and a family history of ATTR amyloidosis, unexplained weight loss, heart rhythm disorders, vitreous opacities, or renal abnormalities. In nonendemic countries, the disease may present as idiopathic rapidly progressive sensory motor axonal neuropathy or atypical CIDP with any of the above symptoms or with bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome, gait disorders, or cardiac hypertrophy. Diagnosis should include DNA testing, biopsy, and amyloid typing. Patients should be followed up every 6–12 months, depending on the severity of the disease and response to therapy. This review outlines detailed recommendations to improve the diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis with PN.

Keywords: ATTR amyloidosis, ATTRv, Diagnosis, hATTR, Peripheral neuropathy, Transthyretin amyloidosis

Introduction

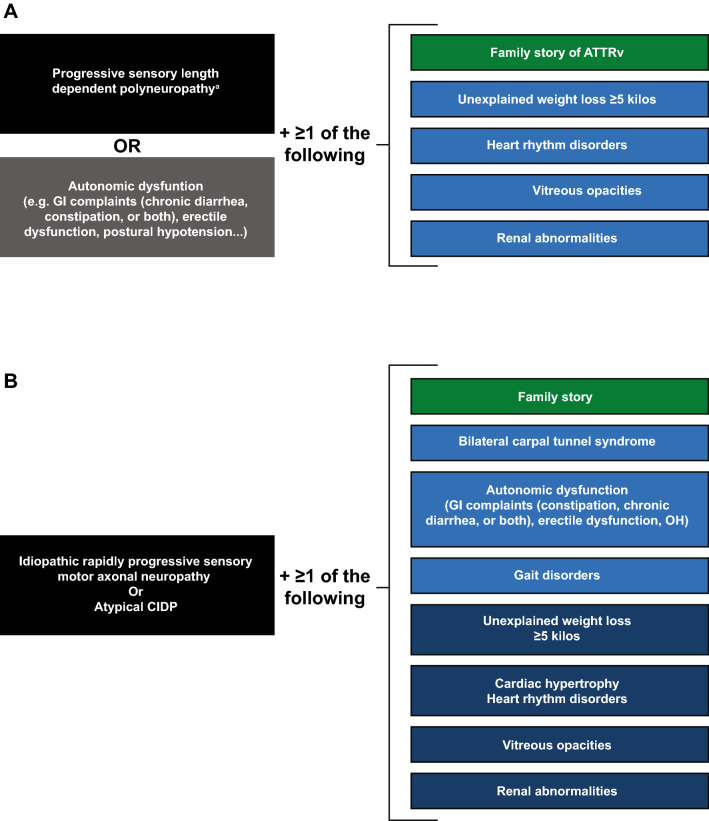

Hereditary amyloid transthyretin (ATTRv; v for “variant”) amyloidosis with polyneuropathy (PN) is a rare multisystemic disease with predominant involvement of the peripheral nervous system and amyloid deposits in the endoneurium [1]. It was first described in endemic areas in Portugal and later in Japan and Sweden and is now considered a worldwide disease [2]. ATTRv amyloidosis has an autosomal-dominant mode of transmission because of a point mutation of the TTR gene [3]. Certain TTR mutations are associated predominantly with endoneurial amyloid deposition that results in polyneuropathy (most commonly Val30Met); others are associated with predominant cardiomyopathy or a mixed phenotype [4–6] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Genotype–phenotype correlations in ATTR amyloidosis. ATTR amyloid transthyretin, WT wild type. Reprinted with permission from Castano et al. [6]

ATTRv amyloidosis is the most serious hereditary polyneuropathy of adult onset and a progressive, devastating, and life-threatening disease. Diagnostic delay varies in nonendemic regions from 3 to 4 years. Average survival from disease onset varies from 6 to 12 years, and cardiac involvement is often the cause of death [7, 8].

The disease is caused by abnormal transthyretin (TTR) protein that misfolds and aggregates to form amyloid fibrils that deposit in organs and tissue. It has long been considered an endemic disease with a high prevalence (~ 1/1000 persons). Early diagnosis is typically facilitated by positive family history, stereotypical neurologic manifestations such as length-dependent polyneuropathy and autonomic dysfunction [9], and presence of the unique TTR variant Val30Met. Gradually, it has been reported in many countries outside endemic areas with a sporadic presentation and is now well accepted as a globally prevalent disease. The estimated prevalence of ATTRv amyloidosis with PN worldwide is 10,000 (1/1,000,000 persons) [2].

Purpose and methodology

The diagnosis of this rare disease is a challenge for the neurologist and is most often delayed by 3–4 years, which impacts patients’ functional and vital prognosis. Diagnostic delays occur for multiple reasons, but oftentimes misleading diagnoses are made because of sporadic, late-onset, highly varied clinical presentation patterns of various TTR variants [10]. In this review, we describe the main phenotypes of neuropathies of this disease and present simple tools to quickly confirm the diagnosis and to perform the minimal investigations needed to clarify the systemic extension of the disease.

Consensus recommendations for the suspicion and diagnosis of all forms of ATTR amyloidosis were developed through a series of development and review cycles by an international working group consisting of key amyloidosis specialists in collaboration with companies conducting research in ATTR amyloidosis (GSK, Ionis, Pfizer, Alnylam) and the Amyloidosis Research Consortium. These consensus recommendations were developed based on the published literature and the medical expertise of the international working group through in-person meetings along with refinement of the draft by telephone or email. The literature was surveyed using PubMed Central, and references were selected by the expert working group according to the relevance of the data. Recently, specific consensus recommendations were provided for cardiology ATTR amyloidosis [11]. This review describes the specific consensus recommendations for best practices in ATTR with predominant PN. It is intended to provide clinicians with an overview of important aspects of ATTR diagnosis that may facilitate rapid and accurate identification of the disease.

Clinical presentation and suspicion index

Clinical manifestations and phenotypes

Historical phenotypes in endemic areas

In endemic areas (such as Portugal, Japan, Sweden, Brazil), the main phenotype represents the hallmark of ATTRv with PN—a length-dependent small-fiber PN with dysautonomia—with manifestations mimicking those of diabetic neuropathy [12]. In these areas, the disease may not be as difficult to diagnose because it is aided by positive family history, high penetrance, and typical clinical presentation and by genetic counseling for, detection in, and follow-up of carriers of the mutant TTR gene [13]. Penetrance, however, is highly variable. For instance, in Portugal, the median age at onset is around 30 years [7], and 80% of mutation carriers are reported to exhibit the disease by age 50, whereas this number is only 11% in Sweden [14, 15].

Initial symptoms of ATTRv with PN vary but can include sensory symptoms such as pain, paresthesia, and numbness in the feet; autonomic dysfunction such as digestive disorders and erectile dysfunction; and general items such as fatigue, weight loss, and plantar ulcers [7, 16]. Sensory loss progresses with advancing disease and eventually extends to the lower limbs and to the hands and arms. More advanced disease may also involve loss of reflexes, reduced motor skills, and muscle weakness [4, 17].

Two clinical neuropathic phenotypes in late versus early onset in Val30Met variant

ATTRv amyloidosis is classified on the basis of age at onset, and symptoms before the age of 50 distinguish early from late onset [18]. Clinical presentation and disease course differ considerably between patients with early-onset and those with late-onset ATTRv with PN associated with the Val30Met mutation [7, 8, 18–21] (Table 1). Early-onset disease follows the classical course. In patients with early onset, penetrance is high (0.8) [14] and the disease is nearly always associated with a positive family history, initial symptoms of somatic or autonomic peripheral neuropathy, less severe disease course, and longer survival [19]. Late-onset disease tends to occur sporadically and typically presents with peripheral (not autonomic) neuropathy. In families with late-onset disease, there is a male predominance and low penetrance. At 50 years, sensorimotor symptoms begin in the lower extremities with disturbance of both superficial and deep sensation (mixed sensory loss) and relatively mild autonomic symptoms [19, 22]. In the Swedish population, amyloid fibril composition determines the phenotype; ATTR consisting of full-length TTR is associated with early onset and neuropathy, whereas a mixture of TTR fragments is associated with late onset, neuropathy, and cardiomyopathy [23].

Table 1.

Characteristics of Val30Met early- and late-onset ATTR amyloidosis at the time of diagnosis and clinical course

| Early-onset Val30Met [7, 19] | Late-onset Val30Met [8, 19, 20] | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at onset, years | < 50 | ≥ 50 |

| Country | Portugal, Japana, Brazil, Swedenb | Swedenb, France, UK, Italy, Japan, USA |

| Positive family history, % | 94 | 48 |

| Peripheral neuropathy, % | 57 | 81 |

| Autonomic neuropathy, % | 48 | 10 |

| Weight loss, % | 5 | 0 |

| Disease course | ||

| Mean delay in need for aid in walking, years | > 5.6 | 3 |

| Mean delay for wheelchair bound, years | 10 | 6 |

| Cardiac events | Progressive conduction disorders |

Restrictive cardiomyopathy Cardiac insufficiency Progressive conduction disorders |

| Median survival, years | 11 | 7.3 |

| Cause of death |

Cachexia Infection |

Cardiac insufficiency Sudden death Cachexia or secondary infection |

Other clinical phenotypes in nonendemic countries

In nonendemic regions, four ATTRv amyloidosis phenotypes are reported [13, 24]. Small-fiber PN is not predominant and may occur in about 33% of patients. Also reported are length-dependent, all-fiber PN with diffuse areflexia and mixed sensory loss for pain, temperature, and proprioception [19] mimicking demyelinating polyneuropathy [25, 26]; multifocal neuropathy with onset in the upper limbs [8, 27]; ataxic neuropathy [24]; and exceptional motor neuropathy [26, 28, 29].

Misdiagnosis

For people in nonendemic areas, diagnosis is likely to be missed. In these areas, 52–77% of cases occur with no family history of the disease [13, 24, 28], and presentation is variable. It has been reported that ATTRv with PN is suspected in only 26–38% of initial evaluations in these areas [24, 28]. Multiple misdiagnoses before the correct diagnosis of amyloid neuropathy have been reported in 20–40% of cases [25, 27].

Misdiagnoses depend on the initial clinical presentation of neuropathy (symptoms and signs). Common misdiagnoses (Table 2) [13, 25–27, 29–32] of patients before the correct diagnosis of ATTRv with PN include chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP), idiopathic axonal polyneuropathy, lumbar spinal stenosis, and, more rarely, diabetic neuropathy and AL amyloidosis. Increased awareness of this serious disease and its symptoms—as well as better knowledge of simple diagnostic tools, especially among neurologists—is essential to enable early diagnosis and optimal treatment of ATTRv with PN.

Table 2.

Main misdiagnosis and red flags

| Misdiagnosis | Incidence, % | Misleading features | Red flags | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIDP | 13–15 |

SM 4 limbs Diffuse areflexia Albuminocytologic dissociation Demyelination on biopsy Demyelinating NCS |

Pain Sensory loss (wrists) Autonomic dysfunction Upper limb weakness NCS |

[26] [25] [30] [31] |

| Chronic axonal idiopathic PN | 24–33 | Axonal neuropathy in the elderly, seemingly idiopathic |

Severity, disability, rapid Difficulties in walking |

[13] [30] [27] |

| CTS | 11 | Paresthesia in the hands | No relief after surgery | [27] |

| Lumbar spinal stenosis | 7.3 |

Progressive difficulty walking in the elderly Spinal stenosis on lumbar CT or MRI |

Abnormal NCS Worsening in spite of surgery |

[25] |

|

Motor neuron disease Motor neuropathy, ALS |

< 1 |

Upper limb and tongue amyotrophy Dysarthria Hand weakness |

Abnormal sensory SNAP (NCS) No symptoms of upper motor neuron involvement |

[32] [29] |

| Miscellaneous | ||||

| Alcoholic PNP | Small-fiber length-dependent PN | Alcoholism | [25] | |

| Diabetic PNP |

Small-fiber length-dependent PN Autonomic dysfunction |

Rapid severity/duration of diabetes Difficulties in walking |

[30] | |

| Paraneoplastic neuropathy |

Non-length-dependent sensory loss + ataxia Weight loss |

No anti-onconeuronal antibody Negative findings on whole-body PET |

[27] | |

ALS amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, CIDP chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, CT computed tomography, CTS carpal tunnel syndrome, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, NCS nerve conduction study, PET positron emission tomography, PN polyneuropathy, PNP peripheral neuropathy, SM sensorimotor, SNAP sensory nerve action potential

The disease course for late onset is more aggressive and has a shorter survival time than for early onset [18]. Initial symptoms of late-onset disease may also include sensory problems in upper limbs (33%) and walking disorders (11%) [24], and autonomic neuropathy may occur later in the disease in approximately 47–78% of these patients [24, 28, 30].

Amyloid can also be deposited in the heart, eyes, and leptomeninges, resulting in associated organ dysfunction and clinical symptoms. Cardiac involvement is usually asymptomatic at diagnosis but has been detected in up to 72% of patients when using cardiac imaging [30]. Cardiac hypertrophy (septal thickness > 12 mm) is found at presentation in 33 of 60 (55%) patients with late-onset Val30Met, predominantly in males [20].

Physicians should be aware of the leptomeningeal forms of ATTRv amyloidosis, which are associated with cerebral hemorrhage [33–36] and CNS dysfunction, typically with symptoms related to CNS impairment such as dementia, ataxia, spasticity, seizures, and stroke-like episodes [37–40]. The abnormal TTR protein deposited in the leptomeninges may be produced in the choroid plexus, making liver transplantation less effective in these patients [37].

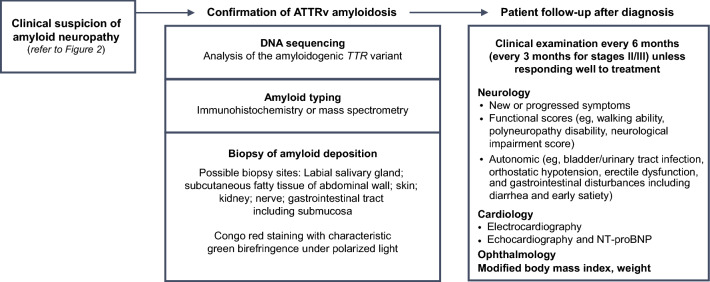

Suspicion index

Suspicion of ATTRv amyloidosis should be high for patients with progressive and disabling polyneuropathy, particularly in elderly patients. The disease should also be considered in patients with neuropathy plus at least one red flag symptom suggestive of multisystemic involvement (Fig. 2) [41].

Fig. 2.

Suspicion index for diagnosis of ATTRv amyloidosis with PN. a In endemic areas. b In nonendemic areas. ATTRv hereditary transthyretin amyloid amyloidosis, CIDP chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, GI gastrointestinal, OH orthostatic hypotension. aNo diabetes, no alcohol abuse, vitamin B12 deficiency. Adapted with permission from Conceicao et al. [41]

For patients with a known family history of ATTRv amyloidosis, any onset of length-dependent axonal polyneuropathy predominantly affecting temperature and pain sensation, autonomic dysfunction, or cardiac arrhythmia signals a need to assess organ involvement.

For patients without a family history of amyloidosis, diagnosis of ATTRv amyloidosis should be considered if they have progressive idiopathic, axonal polyneuropathy, or atypical CIDP. Particular attention should be given to those who have autonomic dysfunction, early gait disorders, gastrointestinal disturbances and weight loss, carpal tunnel syndrome or previous surgery for bilateral carpal tunnel, concurrent cardiac abnormalities, or unexplained weight loss.

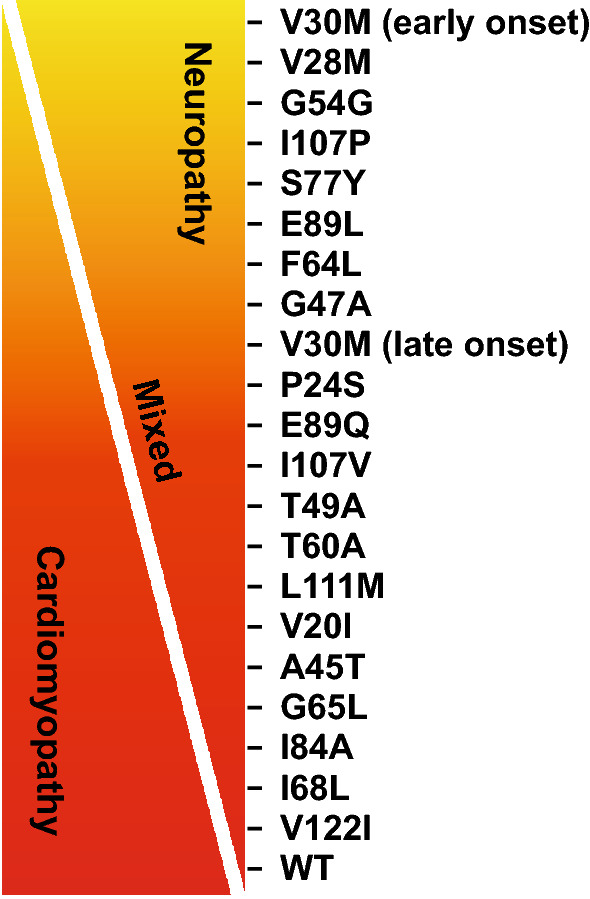

Diagnosis

Physicians should be aware of the clinical presentation and diagnostic approaches for patients with ATTRv amyloidosis with PN [10, 18, 25, 42–45] (Figs. 2, 3, Table 3). Clinical manifestations are diverse and nonspecific and may include neuropathic pain, loss of balance, carpal tunnel syndrome, and unexpected weight loss.

Fig. 3.

Diagnostic approach and patient follow-up. ATTRv hereditary transthyretin amyloid, NT-proBNP N-terminal fragment of the probrain natriuretic peptide, TTR transthyretin

Table 3.

Diagnostic tools for ATTR-PN

| TTR gene analysis | Amyloid detection | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Biopsya | DPD, PYP, HMDP scintigraphy | ||

| Advantages |

Looking for 1 of the 130 amyloidogenic variants [10] Possible to rule out ATTRv if gene analysis is negative for a variant Fastest method to confirm ATTRv in case of neuropathy |

Formal proof of amyloidosis in carriers of TTR variants and sporadic amyloid neuropathy | Noninvasive demonstration of cardiac amyloid with bone scintigraphy [43, 44] |

| Rules | TTR gene sequencing of the 4 exons |

Congo red staining Examination under polarized microscopy Many sections often needed to detect a single deposit |

|

| Limits |

13 nonamyloidogenic variants, including Gly6Ser and Thr119Met [10] Possible delay of genetic results |

Sensitivity for amyloid detection 60–80% [25] Dependent on experience and expertise of pathologist May be invasive and risky (cardiac) Time-consuming Several biopsy sites sometimes needed to find a deposita |

Radiolabeling if no light chain Sensitivity < 100% LV wall thickness > 12 mm in combination with abnormal heart/whole-body retention Heart/whole-body > 7.5 associated with the highest event rate [45] |

| Remarks | Some correlation between mutation and predominant organ involvement (e.g., heart, brain, eye) |

False negative Amyloid light chain must be excluded |

Complementarity of TTR gene analysis May avoid cardiac biopsy |

ATTR-PN amyloid transthyretin polyneuropathy, DPD diphosphono-1,2-propanodicarboxylic acid, HMDP hydroxymethylene diphosphonate, LV left ventricular, PYP pyrophosphate

aAt least one tissue biopsy should be performed to identify amyloid deposits and, if negative, another biopsy, preferentially mini-invasive (skin, labial salivary gland, abdominal fat), should be performed

Diagnostic tools

There are only two main categories of diagnostic tools in ATTR-PN: TTR gene sequencing looking for TTR gene amyloidogenic variants and tools for detection of amyloid deposits including classical biopsy and, more recently, bone scintigraphy with diphosphono-1,2-propanodicarboxylic acid (DPD), hydroxymethylene diphosphonate (HMDP), or pyrophosphate (PYP) (Table 3). Staining a tissue biopsy (salivary gland, abdominal fat, or nerve tissue), typing for amyloid, and screening for TTR mutations by TTR gene sequencing are important measures for identifying amyloid neuropathy in sporadic cases presenting with rapidly idiopathic progressive axonal polyneuropathy of undetermined origin or atypical CIDP [13].

TTR gene sequencing

The TTR gene, located in chromosome 18, is small (4 exons). More than 130 mutations can occur, most of which are pathogenic and amyloidogenic and are associated with varied phenotypes including predominant neuropathy, cardiomyopathy, and, more rarely, ocular and cerebromeningeal. A registry has been established to record the significance of mutations and phenotypes in ATTRv amyloidosis [10]. A few nonamyloidogenic variants have also been identified, including the polymorphism Gly6Ser; the discovery of such a variant has no significant value in a patient with idiopathic sporadic peripheral neuropathy. A TTR variant alone cannot confirm a diagnosis of ATTRv amyloidosis because of incomplete penetrance in carriers. Nevertheless, DNA sequencing of the TTR gene can be a useful approach in patients with idiopathic neuropathy to support or exclude a diagnosis of ATTRv amyloidosis and for predictive genetic counseling testing in healthy but potentially at-risk persons with a family history of ATTRv amyloidosis.

Amyloid confirmation

Biopsy

Staining of biopsy samples with Congo red and visualization of apple-green birefringence of Congo red-stained preparations under polarized light are crucial to confirm the diagnosis of disease and are indicative of the presence of amyloid fibrils. Finding amyloid deposits can be challenging, however, and negative biopsy results should not exclude a diagnosis [46, 47]. Mini-invasive biopsy include labial salivary gland biopsy, skin biopsy, and abdominal fat biopsy, which are preferred to invasive biopsies such as nerve biopsy and cardiac biopsy. The sensitivity of a biopsy can be impeded by inadequacies of the tissue samples; much depends on the site of the biopsy and on whether the biopsy includes nerve tissue (Table 4). In France and Portugal [48], biopsy of the salivary gland is preferred over abdominal fat aspiration, which is used in the USA, the UK, and other European countries except Sweden, where fat pad biopsy is used. The diagnostic sensitivity of a 3-mm-diameter skin punch biopsy at the distal leg 10 cm proximal to the lateral malleolus and proximal thigh is 70% [49, 50]. The minimal number of tissues to be examined for amyloid detection, including by mini-invasive biopsy, is two.

Table 4.

Histologic and mass spectrometry methods for diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis

| Investigation | Sensitivity | Specificity | Aim |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biopsy site | |||

| Sural nerve | 79–80% TTR | High | Detecting amyloid deposits [24, 28, 30] |

| Labial salivary glanda | 91% Val30Met early onset | High | Detecting amyloid deposits [77] |

| Abdominal fat padb | 14–83% | High | Detecting amyloid deposits [78] |

| Heart | ~ 100% | ~ 100% | Detecting amyloid deposits |

| Renal | 92–100% | High | Detecting amyloid deposits [79–82] |

| Skin biopsy | 70% | 100% | Detecting amyloid deposits [49, 50] |

| Pathology test [83] | |||

| Congo red staining | Medium–high | High | Detecting amyloid deposits |

| Polarized microscopy examination | High | High | Green birefringence |

| IHC with anti-TTR antibodies | High | Medium–high | – |

| Immuno-EM with anti-TTR antibodies | High | High | Detecting and typing amyloid fibrils |

| Mass spectrometry tests [84] | |||

| LMD/MS | ~ 100% | High | Determining specific type of amyloid deposits |

Adapted with permission from Adams et al. [85]

ATTR amyloid transthyretin, EM electron microscopy, IHC immunohistochemistry, LMD/MS laser microdissection mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis, TTR transthyretin

aPortugal and France

bUSA, UK, the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden

Bone scintigraphy

Myocardial radiotracer uptake in bone scintigraphy with 99mtechnetium (Tc)-labeled 3,3-DPD, 99mTc-labeled PYP, or 99mTc-labeled HMDP could be useful in patients with peripheral neuropathy, amyloidogenic TTR mutation, and hypertrophic cardiopathy who have negative biopsy findings, and it may obviate the need for endomyocardial biopsy [44].

Assessment of the extent of the disease

Grading and staging other manifestations

Because ATTRv amyloidosis is a systemic disease, physicians should be aware of manifestations other than those of the peripheral nervous system, such as cardiac, ocular, and renal manifestations. A multidisciplinary approach is required to assess whether, through effects of autonomic dysfunction or amyloid deposition, other organs and systems are likely to be affected [18, 41].

Autonomic dysfunction

Autonomic dysfunction occurs in approximately 73% of patients with ATTR amyloidosis with PN and affects the gut, bladder sphincter, genital nerves, and cardiovascular system. Common symptoms include impotence (73% of male patients), gastrointestinal (GI) disturbance (53%), urinary incontinence (50%), and orthostatic dysregulation (46%) [51]. The most common symptoms seen in the GI system include weight loss (approximately 30% of patients), early satiety, and alternating constipation and diarrhea [52]. The incidence of GI disturbances increases as the disease progresses [53], and the onset of diarrhea earlier in the course of the disease is associated with shorter survival [54, 55].

Other organ involvement

Amyloid can also be deposited in the heart, eyes, kidneys, and, rarely, the leptomeninges, resulting in associated organ dysfunction and clinical symptoms. Cardiac involvement is usually asymptomatic at diagnosis but has been detected in up to 72% of patients through cardiac imaging [30] or cardiac multimodal imaging [56]. Cardiac involvement is associated with progressive myocardial infiltration, denervation, and conduction and rhythm disturbances. Systematic assessment and management of cardiac involvement is critical because cardiac manifestations worsen with disease progression and are more likely to cause death [18]. Ophthalmic manifestations have been reported in 20% (glaucoma and/or vitreous opacities) to 70% (dry eye) of patients with ATTR amyloidosis with PN [57–60].

Evaluation of the spread of the disease

Assessment of the spread of the disease is crucial for the detection of accompanying organ damage and requires a multidisciplinary approach by a neurologist (polyneuropathy, autonomic neuropathy), a cardiologist, an ophthalmologist, and a nephrologist or general health practitioner (Table 5) [61–71]. This is essential because the involvement of most organs, other than the nervous system, is latent but may have potentially major consequences—heart blocks, restrictive cardiomyopathy, glaucoma, renal insufficiency—for patients. Required evaluations for neuropathy include neuropathy impairment score (NIS), search for orthostatic hypotension, sudoscan, heart rate variability tests, Compound Autonomic Dysfunction Test for autonomic dysfunction, and Rasch-built Overall Disability Scale (RODS). Required evaluations for cardiac involvement include New York Heart Association (NYHA) score, electrocardiography (ECG), multimodal cardiac imaging [echocardiography (ECHO), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), DPD, metaiodobenzylguanidine], complete ophthalmologic examination, and modified body mass index (mBMI). Biomarkers are also required for heart [N-terminal fragment of the probrain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and cardiac troponins] and renal [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), proteinuria] dysfunction (Table 5).

Table 5.

Evaluation of disease progression at initial screening and follow-up

| Evaluation | Purpose | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurologic manifestations | |||

| A. Sensory motor neuropathy | Questionnaire | [61] | |

| Paresthesia, neurogenic pain | Small fiber loss | ||

| Gait disability | Large fiber loss | ||

| NIS (0–244) | |||

| Weakness in LL and UL | Large fiber loss | ||

| Sensory loss in toes and fingers | Small and large fiber loss | ||

| Tendon reflex loss in the four limbs | Large fiber loss | ||

| Examination | |||

| Pain and thermal sensory loss in the extremities in LL and UL (extension) | Small fiber loss | ||

| Disability | Modified Norris test | Sensorimotor neuropathy | [62] |

|

FAP-RODS RODS |

Overall disability Overall disability |

[63] [86] |

|

| Locomotion | PND score | Autonomy to walk | |

| B. Autonomic neuropathy | CADT* (24-0) | Overall dysfunction | [62] |

| COMPASS 31 | [64] | ||

| Sudoscan | Denervated sweat glands of the soles and palms | ||

| Orthostatic hypotension | [87] | ||

| MIBG scintigraphy | Sympathetic cardiac denervation | ||

| Heart rate variability tests | Sympathetic and parasympathetic | ||

| Non-neurologic manifestations | |||

| C. Cardiac |

ECG, Holter-ECG Cardiac staging |

Looking for conduction block or arrhythmia | |

| ECHO (strain) | Cardiac involvement | ||

| Cardiac MRI | Cardiac involvement | ||

| DPD, PYP, and HMDP scintigraphy | Cardiac amyloidosis | ||

| NT-proBNP | Cardiomyocyte stress | ||

| Cardiac troponin | Cardiomyocyte death | ||

| NYHA class | Extent of heart failure | ||

| NYHA class | Stage the extent of cardiac damage | [65] | |

| D. Ocular |

Slit-lamp examination Intraocular pressure Schirmer test Visual acuity |

Vitreous opacities Ocular hypertension Dry eye (sicca syndrome) |

|

| E. Kidney |

Proteinuria eGFR |

Renal dysfunction Renal insufficiency |

|

| F. General condition |

Weight mBMI |

Nutritional status Nutritional status |

|

| Quality of life | Norfolk QOL-DN | Disease-specific changes in QOL | [66] |

| SF-36 QOL | Non-disease-specific changes in QOL | [67] | |

| Overall scale for ATTR disease | Kumamoto neurologic scale | Sensory disturbances, motor weakness, autonomic dysfunction, and visceral organ impairment | [68, 69] |

| Sensory motor deficit in the limbs and autonomic dysfunction | NIS + 7, mNIS + 7 | Composite score for clinical trial only |

[70] [71] |

CADT Compound Autonomic Dysfunction Test, COMPASS Composite Autonomic Symptom Score, DN diabetic neuropathy, DPD diphosphono-1,2-propanodicarboxylic acid, ECG electrocardiography, ECHO echocardiography, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, FAP-RODS Familial Amyloid Polyneuropathy-Specific Rasch-built Overall Disability Scale, HMDP hydroxymethylene diphosphonate, LL lower limb, mBMI modified body mass index, MIBG metaiodobenzylguanidine, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, mNIS modified Neuropathy Impairment Score, NIS Neuropathy Impairment Score, NT-proBNP N-terminal fragment of the probrain natriuretic peptide, NYHA New York Heart Association, PND polyneuropathy disability, PYP pyrophosphate, QOL quality of life, SF-36 36-Item Short Form Survey, UL upper limb

Grading of the disease

Grading of the disease in each organ system involved is important for the follow-up of these patients. Grading allows detection of eventual disease progression and of organ complications that will require specific management (Tables 3, 5). The frequency of examinations should be determined by the severity and the systemic nature of the disease in each patient.

Follow-up

Patients with confirmed diagnoses should be routinely followed up to monitor for disease progression [18] (Fig. 3). Assessments should evaluate somatic neuropathy with locomotion (polyneuropathy disability score), severity of sensory motor neuropathy (NIS), autonomic dysfunction, manifestations with cardiac insufficiency (NYHA), biomarkers (ECG, ECHO, NT-proBNP), mBMI, renal dysfunction with eGFR, and proteinuria (Table 5). Assessments should be scheduled every 6–12 months, and that schedule should be maintained, depending on investigations.

The quantification of dysfunction caused by ATTRv amyloidosis depends on an array of clinical tests, including those that measure nerve conduction, autonomic neuropathy, manual grip strength, and lower limb function (Tables 5, 6) [7, 8, 18, 51, 72]. However, many of these tests have been used only in relatively small studies; further refinement and validation of these tests in larger patient cohorts are needed.

Table 6.

Staging of ATTRv amyloidosis with PN, scales, and tools at baseline

| Locomotion stage description [7] | Duration of stage, years | PND score [88] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early-onset Val30Met [7] | Late-onset Val30Met Other variants [8, 72] |

||

|

Stage 1 Disease limited to the lower limbs Walking without help Slight weakness of the extensors of the big toes |

5.6 ± 2.8 | 2–4 |

PND I Sensory disturbances in extremities Preserved walking capacity PND II Difficulty walking but no need for a walking stick |

|

Stage 2 Progression of motor signs in lower limbs with steppage and distal amyotrophies; muscles of the hands becoming wasted and weak Patient obviously disabled but can still move around with help |

4.8 ± 3.6 | 2–3 |

PND IIIa 1 stick or 1 crutch required for walking |

|

PND IIIb 2 sticks or 2 crutches required for walking |

|||

|

Stage 3 Patient confined to a wheelchair or a bed, with generalized weakness and areflexia |

2.3 ± 3.1 | 1–2 |

PND IV Patient confined to a wheelchair or a bed |

Reprinted with permission from Adams [18]

ATTRv hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis, PND polyneuropathy disability

Consequences of diagnosis with ATTRv with PN

For patients with diagnoses of ATTRv with PN, early disease-modifying therapy may be beneficial [73, 74] and underscores the need for diagnosis as soon as possible. Genetic counseling is recommended for family members of patients, and therapeutic patient education is recommended for siblings and children [75, 76].

Conclusions

Identification of ATTRv amyloidosis with PN can be challenging, particularly in nonendemic regions, and a high level of suspicion is required to diagnose patients as early as possible. Patients can present with heterogeneous symptoms and variable levels of disease severity, which often leads to a misdiagnosis of diabetic neuropathy or CIDP. Early and accurate diagnosis may also be confounded by a lack of family history and the presence of various phenotypes common to multiple disease conditions such as GI disorders. Older patient age at disease onset can also contribute to misdiagnosis because symptoms of ATTR amyloidosis may be confused with declines in systemic neurologic function that typically occur with normal aging.

In sporadic and potentially misdiagnosed cases, important tools for identifying amyloid neuropathy include TTR gene sequencing for amyloidogenic mutations, tissue biopsy (salivary gland, skin, abdominal fat, or nerve tissue) with staining, and amyloid typing. Because ATTRv with PN is a systemic disease, a holistic assessment approach should be used that includes consultation across multiple specialties (e.g., neurologists, cardiologists, ophthalmologists and eventually gastroenterologists, and nephrologists). Early and accurate diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis allows early treatment and will potentially modify disease progression in patients.

Acknowledgements

Funding for these recommendations was provided by the Amyloidosis Research Consortium. Medical editorial assistance with nonintellectual content and manuscript preparation was provided by ApotheCom (San Francisco, CA, USA). This review was sponsored by the Amyloidosis Research Consortium.

Author contributions

Dr Adams wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript for intellectual content and gave approval for it to be submitted for publication.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

This review was sponsored by the Amyloidosis Research Consortium. Dr Adams reports grants from Alnylam and Pfizer and personal fees from Prothena, GSK, Alnylam, and Pfizer. Dr Ando has nothing to disclose. Dr Beirão has nothing to disclose. Dr Coelho was paid per protocol for clinical trials from FoldRx, Pfizer, Ionis, and Alnylam and received grants from FoldRx and Pfizer; received support from Pfizer, Ionis, Biogen, and Alnylam to attend scientific meetings; and has presented on behalf of Pfizer, Alnylam, GSK, Prothena, and Ionis/Akcea and received honoraria. Dr Gertz has received personal fees from Ionis/Akcea, Alnylam, Prothena, Celgene, Janssen, Annexon, Appellis, Amgen, Medscape, Physicians Education Resource, and Research to Practice; grants and personal fees from Spectrum; personal fees for Data Safety Monitoring board from AbbVie; speaker fees from Teva, Johnson and Johnson, Medscape, and DAVA Oncology; royalties from Springer Publishing; and grant funding from the Amyloidosis Foundation, the International Waldenström Foundation, and the National Cancer Institute (SPORE MM SPORE 5P50 CA186781-04). In addition, he has served on advisory boards for Pharmacyclics and for Proclara (outside the submitted work). Dr Gillmore has participated in advisory boards for Alnylam Pharmaceuticals Inc and GSK Inc. Dr Hawkins has nothing to disclose. Ms Lousada has received honoraria from Akcea. Dr Suhr has received honoraria and travel and consultancy fees from Ionis/Akcea, Alnylam, Prothena, and Intellia. Dr Merlini has received honoraria from Janssen and Prothena; travel support from Prothena and Celgene; and consulting fees from Millennium, Pfizer, Janssen, Prothena, and Ionis.

Ethical standards

Not applicable for this type of study.

Informed consent

Not applicable for this type of study.

References

- 1.Adams D, Koike H, Slama M, Coelho T. Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis: a model of medical progress for a fatal disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(7):387–404. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt HH, Waddington-Cruz M, Botteman MF, Carter JA, Chopra AS, Hopps M, Stewart M, Fallet S, Amass L. Estimating the global prevalence of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2018;57:829–837. doi: 10.1002/mus.26034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saraiva MJ, Birken S, Costa PP, Goodman DS. Amyloid fibril protein in familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy, Portuguese type. Definition of molecular abnormality in transthyretin (prealbumin) J Clin Investig. 1984;74:104–119. doi: 10.1172/JCI111390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkins PN, Ando Y, Dispenzeri A, Gonzalez-Duarte A, Adams D, Suhr OB. Evolving landscape in the management of transthyretin amyloidosis. Ann Med. 2015;47:625–638. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2015.1068949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rapezzi C, Quarta CC, Obici L, Perfetto F, Longhi S, Salvi F, Biagini E, Lorenzini M, Grigioni F, Leone O, Cappelli F, Palladini G, Rimessi P, Ferlini A, Arpesella G, Pinna AD, Merlini G, Perlini S. Disease profile and differential diagnosis of hereditary transthyretin-related amyloidosis with exclusively cardiac phenotype: an Italian perspective. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:520–528. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castano A, Drachman BM, Judge D, Maurer MS. Natural history and therapy of TTR-cardiac amyloidosis: emerging disease-modifying therapies from organ transplantation to stabilizer and silencer drugs. Heart Fail Rev. 2015;20:163–178. doi: 10.1007/s10741-014-9462-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coutinho P, Martins da Silva A, Lopas LJ (1980) Forty years of experience with type 1 amyloid neuropathy. Review of 483 cases. In: Amyloid and amyloidosis. Excerpta Medica, Amsterdam, pp 88–98

- 8.Koike H, Tanaka F, Hashimoto R, Tomita M, Kawagashira Y, Iijima M, Fujitake J, Kawanami T, Kato T, Yamamoto M, Sobue G. Natural history of transthyretin Val30Met familial amyloid polyneuropathy: analysis of late-onset cases from non-endemic areas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:152–158. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrade C. A peculiar form of peripheral neuropathy; familiar atypical generalized amyloidosis with special involvement of the peripheral nerves. Brain. 1952;75:408–427. doi: 10.1093/brain/75.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowczenio DM, Noor I, Gillmore JD, Lachmann HJ, Whelan C, Hawkins PN, Obici L, Westermark P, Grateau G, Wechalekar AD. Online registry for mutations in hereditary amyloidosis including nomenclature recommendations. Hum Mutat. 2014;35:E2403–2412. doi: 10.1002/humu.22619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maurer MS, Bokhari S, Damy T, Dorbala S, Drachman BM, Fontana M, Grogan M, Kristen AV, Lousada I, Nativi-Nicolau J, Cristina Quarta C, Rapezzi C, Ruberg FL, Witteles R, Merlini G. Expert consensus recommendations for the suspicion and diagnosis of transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12:e006075. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.119.006075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams D, Cauquil C, Labeyrie C, Beaudonnet G, Algalarrondo V, Theaudin M. TTR kinetic stabilizers and TTR gene silencing: a new era in therapy for familial amyloidotic polyneuropathies. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;17:791–802. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2016.1145664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams D, Lozeron P, Lacroix C. Amyloid neuropathies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25:564–572. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328357bdf6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plante-Bordeneuve V, Carayol J, Ferreira A, Adams D, Clerget-Darpoux F, Misrahi M, Said G, Bonaiti-Pellie C. Genetic study of transthyretin amyloid neuropathies: carrier risks among French and Portuguese families. J Med Genet. 2003;40:e120. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.11.e120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hellman U, Alarcon F, Lundgren HE, Suhr OB, Bonaiti-Pellie C, Plante-Bordeneuve V. Heterogeneity of penetrance in familial amyloid polyneuropathy, ATTR Val30Met, in the Swedish population. Amyloid. 2008;15:181–186. doi: 10.1080/13506120802193720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams D, Beaudonnet G, Adam C, Lacroix C, Theaudin M, Cauquil C, Labeyrie C. Familial amyloid polyneuropathy: when does it stop to be asymptomatic and need a treatment? Rev Neurol (Paris) 2016;172:645–652. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coelho T, Vinik A, Vinik EJ, Tripp T, Packman J, Grogan DR. Clinical measures in transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2017;55:323–332. doi: 10.1002/mus.25257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams D. Recent advances in the treatment of familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2013;6:129–139. doi: 10.1177/1756285612470192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koike H, Misu K, Ikeda S, Ando Y, Nakazato M, Ando E, Yamamoto M, Hattori N, Sobue G. Type I (transthyretin Met30) familial amyloid polyneuropathy in Japan: early- vs late-onset form. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1771–1776. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.11.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hornsten R, Pennlert J, Wiklund U, Lindqvist P, Jensen SM, Suhr OB. Heart complications in familial transthyretin amyloidosis: impact of age and gender. Amyloid. 2010;17:63–68. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2010.483114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olsson M, Norgren N, Obayashi K, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Suhr OB, Cederquist K, Jonasson J. A possible role for miRNA silencing in disease phenotype variation in Swedish transthyretin V30M carriers. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamashita T, Ueda M, Misumi Y, Masuda T, Nomura T, Tasaki M, Takamatsu K, Sasada K, Obayashi K, Matsui H, Ando Y. Genetic and clinical characteristics of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis in endemic and non-endemic areas: experience from a single-referral center in Japan. J Neurol. 2018;265:134–140. doi: 10.1007/s00415-017-8640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ihse E, Ybo A, Suhr OB, Lindqvist P, Backman C. Amyloid fibril composition is related to the phenotype of hereditary transthyretin V30M amyloidosis. J Pathol. 2008;216:253–261. doi: 10.1002/path.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams D, Lozeron P, Theaudin M, Mincheva Z, Cauquil C, Adam C, Signate A, Vial C, Maisonobe T, Delmont E, Franques J, Vallat JM, Sole G, Pereon Y, Lacour A, Echaniz-Laguna A, Misrahi M, Lacroix C. Regional difference and similarity of familial amyloidosis with polyneuropathy in France. Amyloid. 2012;19(Suppl 1):61–64. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2012.685665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cortese A, Vegezzi E, Lozza A, Alfonsi E, Montini A, Moglia A, Merlini G, Obici L. Diagnostic challenges in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis with polyneuropathy: avoiding misdiagnosis of a treatable hereditary neuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88:457–458. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-315262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lozeron P, Mariani LL, Dodet P, Beaudonnet G, Theaudin M, Adam C, Arnulf B, Adams D. Transthyretin amyloid polyneuropathies mimicking a demyelinating polyneuropathy. Neurology. 2018;91:e143–e152. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Theaudin M, Lozeron P, Algalarrondo V, Lacroix C, Cauquil C, Labeyrie C, Slama MS, Adam C, Guiochon-Mantel A, Adams D, French FAPNSG. Upper limb onset of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis is common in non-endemic areas. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26:497–e436. doi: 10.1111/ene.13845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cappellari M, Cavallaro T, Ferrarini M, Cabrini I, Taioli F, Ferrari S, Merlini G, Obici L, Briani C, Fabrizi GM. Variable presentations of TTR-related familial amyloid polyneuropathy in seventeen patients. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2011;16:119–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2011.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goyal NA, Mozaffar T. Tongue atrophy and fasciculations in transthyretin familial amyloid neuropathy: An ALS mimicker. Neurol Genet. 2015;1:e18. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koike H, Hashimoto R, Tomita M, Kawagashira Y, Iijima M, Tanaka F, Sobue G. Diagnosis of sporadic transthyretin Val30Met familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a practical analysis. Amyloid. 2011;18:53–62. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2011.565524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathis S, Magy L, Diallo L, Boukhris S, Vallat JM. Amyloid neuropathy mimicking chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2012;45:26–31. doi: 10.1002/mus.22229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lozeron P, Lacroix C, Theaudin M, Richer A, Gugenheim M, Adams D, Misrahi M. An amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-like syndrome revealing an amyloid polyneuropathy associated with a novel transthyretin mutation. Amyloid. 2013;20:188–192. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2013.818535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arpa Gutierrez J, Morales C, Lara M, Munoz C, Garcia-Rojo M, Caminero A, Gutierrez M. Type I familial amyloid polyneuropathy and pontine haemorrhage. Acta Neuropathol. 1993;86:542–545. doi: 10.1007/BF00228595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bersano A, Del Bo R, Ballabio E, Cinnante C, Lanfranconi S, Comi GP, Baron P, Bresolin N, Candelise L. Transthyretin Asn90 variant: amyloidogenic or non-amyloidogenic role. J Neurol Sci. 2009;284:113–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakashita N, Ando Y, Jinnouchi K, Yoshimatsu M, Terazaki H, Obayashi K, Takeya M. Familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (ATTR Val30Met) with widespread cerebral amyloid angiopathy and lethal cerebral hemorrhage. Pathol Int. 2001;51:476–480. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2001.01228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salvi F, Pastorelli F, Plasmati R, Morelli C, Rapezzi C, Bianchi A, Mascalchi M. Brain microbleeds 12 years after orthotopic liver transplantation in Val30Met amyloidosis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24:e149–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benson MD. Leptomeningeal amyloid and variant transthyretins. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:351–354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vidal R, Garzuly F, Budka H, Lalowski M, Linke RP, Brittig F, Frangione B, Wisniewski T. Meningocerebrovascular amyloidosis associated with a novel transthyretin mis-sense mutation at codon 18 (TTRD 18G) Am J Pathol. 1996;148:361–366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamashita T, Ando Y, Okamoto S, Misumi Y, Hirahara T, Ueda M, Obayashi K, Nakamura M, Jono H, Shono M, Asonuma K, Inomata Y, Uchino M. Long-term survival after liver transplantation in patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Neurology. 2012;78:637–643. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318248df18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikeda SI. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy with familial transthyretin-derived oculoleptomeningeal amyloidosis. Brain Nerve. 2013;65:831–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conceicao I, Gonzalez-Duarte A, Obici L, Schmidt HH, Simoneau D, Ong ML, Amass L. "Red-flag" symptom clusters in transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2016;21:5–9. doi: 10.1111/jns.12153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carvalho A, Rocha A, Lobato L. Liver transplantation in transthyretin amyloidosis: issues and challenges. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:282–292. doi: 10.1002/lt.24058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fine NM, Arruda-Olson AM, Dispenzieri A, Zeldenrust SR, Gertz MA, Kyle RA, Swiecicki PL, Scott CG, Grogan M. Yield of noncardiac biopsy for the diagnosis of transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:1723–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gillmore JD, Maurer MS, Falk RH, Merlini G, Damy T, Dispenzieri A, Wechalekar AD, Berk JL, Quarta CC, Grogan M, Lachmann HJ, Bokhari S, Castano A, Dorbala S, Johnson GB, Glaudemans AW, Rezk T, Fontana M, Palladini G, Milani P, Guidalotti PL, Flatman K, Lane T, Vonberg FW, Whelan CJ, Moon JC, Ruberg FL, Miller EJ, Hutt DF, Hazenberg BP, Rapezzi C, Hawkins PN. Nonbiopsy diagnosis of cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Circulation. 2016;133:2404–2412. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rapezzi C, Quarta CC, Guidalotti PL, Pettinato C, Fanti S, Leone O, Ferlini A, Longhi S, Lorenzini M, Reggiani LB, Gagliardi C, Gallo P, Villani C, Salvi F. Role of (99m)Tc-DPD scintigraphy in diagnosis and prognosis of hereditary transthyretin-related cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imag. 2011;4:659–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luigetti M, Conte A, Del Grande A, Bisogni G, Madia F, Lo Monaco M, Laurenti L, Obici L, Merlini G, Sabatelli M. TTR-related amyloid neuropathy: clinical, electrophysiological and pathological findings in 15 unrelated patients. Neurol Sci. 2013;34:1057–1063. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1105-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plante-Bordeneuve V, Ferreira A, Lalu T, Zaros C, Lacroix C, Adams D, Said G. Diagnostic pitfalls in sporadic transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy (TTR-FAP) Neurology. 2007;69:693–698. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000267338.45673.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Do Amaral B, Coelho T, Sousa A, Guimaraes A. Usefulness of labial salivary gland biopsy in familial amyloid polyneuropathy Portuguese type. Amyloid. 2009;16:232–238. doi: 10.3109/13506120903421850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ebenezer GJ, Liu Y, Judge DP, Cunningham K, Truelove S, Carter ND, Sebastian B, Byrnes K, Polydefkis M. Cutaneous nerve biomarkers in transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Ann Neurol. 2017;82:44–56. doi: 10.1002/ana.24972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chao CC, Hsueh HW, Kan HW, Liao CH, Jiang HH, Chiang H, Lin WM, Yeh TY, Lin YH, Cheng YY, Hsieh ST. Skin nerve pathology: biomarkers of premanifest and manifest amyloid neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 2019;85:560–573. doi: 10.1002/ana.25433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dohrn MF, Rocken C, De Bleecker JL, Martin JJ, Vorgerd M, Van den Bergh PY, Ferbert A, Hinderhofer K, Schroder JM, Weis J, Schulz JB, Claeys KG. Diagnostic hallmarks and pitfalls in late-onset progressive transthyretin-related amyloid-neuropathy. J Neurol. 2013;260:3093–3108. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-7124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wixner J, Mundayat R, Karayal ON, Anan I, Karling P, Suhr OB. THAOS: gastrointestinal manifestations of transthyretin amyloidosis - common complications of a rare disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:61. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steen L, Ek B. Familial amyloidosis with polyneuropathy. A long-term follow-up of 21 patients with special reference to gastrointestinal symptoms. Acta Med Scand. 1983;214:387–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suhr O, Danielsson A, Holmgren G, Steen L. Malnutrition and gastrointestinal dysfunction as prognostic factors for survival in familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. J Intern Med. 1994;235:479–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1994.tb01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andersson R. Familial amyloidosis with polyneuropathy. A clinical study based on patients living in northern Sweden. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1976;590:1–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bechiri MY, Eliahou L, Rouzet F, Fouret PJ, Antonini T, Samuel D, Adam R, Adams D, Slama MS, Algalarrondo V. Multimodality imaging of cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis 16 years after a domino liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:2208–2212. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ando E, Ando Y, Okamura R, Uchino M, Ando M, Negi A. Ocular manifestations of familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy type I: long-term follow up. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:295–298. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.4.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu T, Zhang B, Jin X, Wang W, Lee J, Li J, Yuan H, Cheng X. Ophthalmic manifestations in a Chinese family with familial amyloid polyneuropathy due to a TTR Gly83Arg mutation. Eye. 2014;28:26–33. doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beirao JM, Malheiro J, Lemos C, Beirao I, Costa P, Torres P. Ophthalmological manifestations in hereditary transthyretin (ATTR V30M) carriers: a review of 513 cases. Amyloid. 2015;22:117–122. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2015.1015678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martins AC, Rosa AM, Costa E, Tavares C, Quadrado MJ, Murta JN. Ocular manifestations and therapeutic options in patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a systematic review. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:282405. doi: 10.1155/2015/282405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dyck PJ, Davies JL, Litchy WJ, O'Brien PC. Longitudinal assessment of diabetic polyneuropathy using a composite score in the Rochester Diabetic Neuropathy Study cohort. Neurology. 1997;49:229–239. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.1.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Denier C, Ducot B, Husson H, Lozeron P, Adams D, Meyer L, Said G, Planté-Bordeneuve V. A brief compound test for assessment of autonomic and sensory-motor dysfunction in familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Neurol. 2007;254:1684–1688. doi: 10.1007/s00415-007-0617-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pruppers MHJ, Merkies ISJ, Faber CG, Da Silva AM, Costa V, Coelho T. The Val30Met familial amyloid polyneuropathy specific Rasch-built overall disability scale (FAP-RODS©) J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2015;20:319–327. doi: 10.1111/jns.12120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sletten DM, Suarez GA, Low PA, Mandrekar J, Singer W. COMPASS 31: a refined and abbreviated Composite Autonomic Symptom Score. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1196–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gillmore JD, Damy T, Fontana M, Hutchinson M, Lachmann HJ, Martinez-Naharro A, Quarta CC, Rezk T, Whelan CJ, Gonzalez-Lopez E, Lane T, Gilbertson JA, Rowczenio D, Petrie A, Hawkins PN. A new staging system for cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2799–2806. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vinik EJ, Vinik AI, Paulson JF, Merkies IS, Packman J, Grogan DR, Coelho T. Norfolk QOL-DN: validation of a patient reported outcome measure in transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2014;19:104–114. doi: 10.1111/jns5.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vita GL, Stancanelli C, Gentile L, Barcellona C, Russo M, Bella GD, Vita G, Mazzeo A. 6MWT performance correlates with peripheral neuropathy but not with cardiac involvement in patients with hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;29(3):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tashima K, Ando Y, Terazaki H, Yoshimatsu S-i, Suhr OB, Obayashi K, Yamashita T, Ando E, Uchino M, Ando M. Outcome of liver transplantation for transthyretin amyloidosis: follow-up of Japanese familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy patients. J Neurol Sci. 1999;171:19–23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dyck PJ, Kincaid JC, Dyck PJB, Chaudhry V, Goyal NA, Alves C, Salhi H, Wiesman JF, Labeyrie C, Robinson-Papp J, Cardoso M, Laura M, Ruzhansky K, Cortese A, Brannagan TH, 3rd, Khoury J, Khella S, Waddington-Cruz M, Ferreira J, Wang AK, Pinto MV, Ayache SS, Benson MD, Berk JL, Coelho T, Polydefkis M, Gorevic P, Adams DH, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Whelan C, Merlini G, Heitner S, Drachman BM, Conceicao I, Klein CJ, Gertz MA, Ackermann EJ, Hughes SG, Mauermann ML, Bergemann R, Lodermeier KA, Davies JL, Carter RE, Litchy WJ. Assessing mNIS+7Ionis and international neurologists' proficiency in a familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy trial. Muscle Nerve. 2017;56:901–911. doi: 10.1002/mus.25563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Adams D, Cauquil C, Labeyrie C. Familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2017;30:481–489. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mariani LL, Lozeron P, Theaudin M, Mincheva Z, Signate A, Ducot B, Algalarrondo V, Denier C, Adam C, Nicolas G, Samuel D, Slama MS, Lacroix C, Misrahi M, Adams D. Genotype-phenotype correlation and course of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathies in France. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:901–916. doi: 10.1002/ana.24519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Adams D, Gonzalez-Duarte A, O'Riordan WD, Yang CC, Ueda M, Kristen AV, Tournev I, Schmidt HH, Coelho T, Berk JL, Lin KP, Vita G, Attarian S, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Mezei MM, Campistol JM, Buades J, Brannagan TH, 3rd, Kim BJ, Oh J, Parman Y, Sekijima Y, Hawkins PN, Solomon SD, Polydefkis M, Dyck PJ, Gandhi PJ, Goyal S, Chen J, Strahs AL, Nochur SV, Sweetser MT, Garg PP, Vaishnaw AK, Gollob JA, Suhr OB. Patisiran, an RNAi therapeutic, for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Benson MD, Waddington-Cruz M, Berk JL, Polydefkis M, Dyck PJ, Wang AK, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Barroso FA, Merlini G, Obici L, Scheinberg M, Brannagan TH, 3rd, Litchy WJ, Whelan C, Drachman BM, Adams D, Heitner SB, Conceicao I, Schmidt HH, Vita G, Campistol JM, Gamez J, Gorevic PD, Gane E, Shah AM, Solomon SD, Monia BP, Hughes SG, Kwoh TJ, McEvoy BW, Jung SW, Baker BF, Ackermann EJ, Gertz MA, Coelho T. Inotersen treatment for patients with hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:22–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Obici L, Kuks JB, Buades J, Adams D, Suhr OB, Coelho T, Kyriakides T, European Network for T-F Recommendations for presymptomatic genetic testing and management of individuals at risk for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2016;29(Suppl 1):S27–S35. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Theaudin M, Cauquil C, Antonini T, Algalarrondo V, Labeyrie C, Aycaguer S, Clement M, Kubezyk M, Nonnez G, Morier A, Bourges C, Darras A, Mouzat L, Adams D. Familial amyloid polyneuropathy: elaboration of a therapeutic patient education programme, "EdAmyl". Amyloid. 2014;21:225–230. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2014.941463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dardiotis E, Koutsou P, Papanicolaou EZ, Vonta I, Kladi A, Vassilopoulos D, Hadjigeorgiou G, Christodoulou K, Kyriakides T. Epidemiological, clinical and genetic study of familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy in Cyprus. Amyloid. 2009;16:32–37. doi: 10.1080/13506120802676948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van Gameren II, Hazenberg BP, Bijzet J, van Rijswijk MH. Diagnostic accuracy of subcutaneous abdominal fat tissue aspiration for detecting systemic amyloidosis and its utility in clinical practice. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2015–2021. doi: 10.1002/art.21902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lobato L, Beirao I, Guimaraes SM, Droz D, Guimaraes S, Grunfeld JP, Noel LH. Familial amyloid polyneuropathy type I (Portuguese): distribution and characterization of renal amyloid deposits. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31:940–946. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v31.pm9631837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lobato L, Beirao I, Silva M, Bravo F, Silvestre F, Guimaraes S, Sousa A, Noel LH, Sequeiros J. Familial ATTR amyloidosis: microalbuminuria as a predictor of symptomatic disease and clinical nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:532–538. doi: 10.1093/ndt/18.3.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oguchi K, Takei Y, Ikeda S. Value of renal biopsy in the prognosis of liver transplantation in familial amyloid polyneuropathy ATTR Val30Met patients. Amyloid. 2006;13:99–107. doi: 10.1080/13506120600722662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Snanoudj R, Durrbach A, Gauthier E, Adams D, Samuel D, Ferlicot S, Bedossa P, Prigent A, Bismuth H, Charpentier B. Changes in renal function in patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy treated with orthotopic liver transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:1779–1785. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ando Y, Coelho T, Berk JL, Cruz MW, Ericzon BG, Ikeda S, Lewis WD, Obici L, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Rapezzi C, Said G, Salvi F. Guideline of transthyretin-related hereditary amyloidosis for clinicians. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:31. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klein CJ, Vrana JA, Theis JD, Dyck PJ, Dyck PJ, Spinner RJ, Mauermann ML, Bergen HR, 3rd, Zeldenrust SR, Dogan A. Mass spectrometric-based proteomic analysis of amyloid neuropathy type in nerve tissue. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:195–199. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Adams D, Suhr OB, Hund E, Obici L, Tournev I, Campistol JM, Slama MS, Hazenberg BP, Coelho T, European Network for T-F First European consensus for diagnosis, management, and treatment of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2016;29(Suppl 1):S14–S26. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.van Nes SI, Vanhoutte EK, van Doorn PA, Hermans M, Bakkers M, Kuitwaard K, Faber CG, Merkies IS. Rasch-built Overall Disability Scale (R-ODS) for immune-mediated peripheral neuropathies. Neurology. 2011;76:337–345. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318208824b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Piekarski E, Chequer R, Algalarrondo V, Eliahou L, Mahida B, Vigne J, Adams D, Slama MS, Le Guludec D, Rouzet F. Cardiac denervation evidenced by MIBG occurs earlier than amyloid deposits detection by diphosphonate scintigraphy in TTR mutation carriers. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45:1108–1118. doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-3963-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yamamoto S, Wilczek HE, Nowak G, Larsson M, Oksanen A, Iwata T, Gjertsen H, Soderdahl G, Wikstrom L, Ando Y, Suhr OB, Ericzon BG. Liver transplantation for familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (FAP): a single-center experience over 16 years. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2597–2604. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]