Abstract

Sleep dysfunction has been identified in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease (AD); however, the role and mechanism of circadian rhythm dysfunction is less well understood. In a well-characterized cohort of patients with AD at the mild cognitive impairment stage (MCI-AD), we identify that circadian rhythm irregularities were accompanied by altered humoral immune responses detected in both the cerebrospinal fluid and plasma as well as alterations of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of neurodegeneration. On the other hand, sleep disruption was more so associated with abnormalities in circulating markers of immunity and inflammation and decrements in cognition.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, circadian, immunity, inflammation, neurodegeneration, sleep

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) remains the primary contributor to dementia, afflicting 50 million people worldwide with a dramatic projected increase to 152 million people in 2050 [1]. The estimated cost of AD is $305 billion in 2020 and expected to increase to $1 trillion as the population ages [2]. Urgent measures are therefore critically needed to prevent AD occurrence and mitigate progression. Several studies have identified a relationship between sleep deficits and circadian dysfunction in the pathophysiology of AD [3]. Thus, circadian and sleep measures may represent high priority, novel potential promulgators of AD activity and possible interventional targets to halt or mitigate AD progression.

Preliminary findings support circadian-related alterations of protein homeostasis, inflammation and immune-mediated pathways, i.e., implicating dysregulation of NF-kB signaling and BMAL1 (clock gene) regulation of nuclear receptor protein, Reverbα [4]. However, thus far it is unclear if the inflammation observed in relation to AD biomarkers [5] and circadian and sleep indices [6] share the same inflammatory pathways and immune-mediated outcomes in the central nervous system and the periphery. To identify inflammatory pathways or networks of inflammatory analytes pertinent to circadian and sleep indices and neurodegeneration, it is crucial to develop approaches that evaluate multiple analytes concomitantly and interrogate their clinical significance when expressed together in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma. As a preliminary test of the premise that distinct immune/inflammation related changes and altered neurodegeneration biomarkers relate to sleep and circadian abnormalities and relate to cognitive outcomes in AD, we conducted an unbiased, hypothesis-generating examination of CSF and plasma biomarkers in a well characterized cohort of patients with AD at the mild cognitive impairment stage (MCI-AD) who underwent circadian and sleep studies.

METHODS

Participants and protocol

Clinical characterization of the MCI-AD study patients has been published previously [5]. A subset of the cohort underwent circadian and sleep rhythm phenotyping via actigraphy and overnight home sleep apnea testing using standard protocols. Informed consent was obtained, and the study was approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board. Details on the AD biomarkers and the panel of inflammation-related analytes have been detailed earlier [5]. The protocol involved CSF and plasma collection and analysis by an independent laboratory via the validated RBM Multi-Analyte Profile (MAP) platform from Myriad Genetics (Salt Lake City, UT) using a Luminex platform with Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute validation. Morning CSF and plasma samples were collected contemporaneously with two randomly selected technical replicates of CSF and plasma samples to evaluate consistency. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [7] and Clinical Dementia Rating scale (DRS) [8] were collected to characterize the degree of baseline cognitive and functional deficit.

Data collection

Baseline circadian and sleep measures were collected less than three months from the date of the CSF biomarker collection. A wrist accelerometer (Motionlogger Micro Watch by Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc®) with multi-parameter data collection including temperature and an ambient light channel was used by participants for 10 days on the non-dominant wrist. Activity data was collected in proportional integration mode (PIM) and the Cole-Kripke algorithm was used as the validated scoring algorithm with manual scoring in 1-min epochs. Circadian measures include the F-ratio, a measure of robustness of rhythmicity of the circadian activity pattern capturing the extent to which an individual’s sleep-wake activity conforms to an extended cosine model, with higher values indicating greater conformity to the cosine shape [9]. Perturbations of circadian robustness measured by the F-ratio are associated with adverse outcomes including increased mortality and cognitive decline [10, 11]. Other circadian measures include amplitude (counts/min, difference between the peak and nadir of the activity fitted curve), mesor (counts/min, mean of the activity fitted curve) and acrophase (hours, time of day of the peak of the fitted curve). We also examined circadian variability, i.e., sleep regularity index (SRI), the likelihood that any two time-points (minute-by-minute) 24 h apart are the same sleep/wake state across all days [12] and interdaily stability, the latter a measure of the fragmentation of the rhythm relative to its 24-h amplitude [13]. Sleep-wake variables include: total sleep time (TST), nocturnal awakenings, sleep efficiency (SE), and wakefulness after sleep onset. Sleep fragmentation index (SFI), i.e., number of awakenings / Total Sleep Time in minutes * 100 as a measure of sleep disruption was calculated. A home sleep apnea testing diagnostic device (ApneaLink Air by ResMed ®) was used for one night (overlapped with actigraphy monitoring) to monitor respiratory effort via nasal flow (by nasal-oral thermocouple and nasal cannula pressure recording, 100 Hz sampling rate), thoracoabdominal pneumatic technology (10 Hz), pulse, oxygen saturation via finger pulse oximeter (Nonin ® reusable soft sensor oximeter, sampling frequency 1 Hz), snoring microphone via nasal cannula and position sensor with standard scoring criteria. The apnea hypopnea index (AHI, hypopnea with 3% oxygen desaturation) was used to define sleep disordered breathing (SDB) severity.

Statistical methods

We examined 11 circadian/sleep measures and the 69 CSF or circulating biomarkers of inflammation, immunity and neurodegeneration. Linear models (beta estimates, 95% confidence intervals) were used to assess sleep and circadian measures relative to log-transformed CSF and plasma biomarkers of neurodegeneration, inflammation and immunity and cognitive measures. Models were fit unadjusted and then adjusted individually for age, sex, body mass index, or education. We present unadjusted results given the discovery-based approach and also present the application of FDR adjustment which corrects for the 69 comparisons with each circadian/sleep marker. Analysis was performed using SAS software (version 9.4) and an overall significance level of 0.05 was assumed for all tests; limma analyses (R software) [14] were used to optimize power, however, as results were not substantively changed, only linear model results are presented.

RESULTS

18 participants with MCI-AD with median age69.5 [P25, P75:64.0, 72.0], 44.4% female, all Caucasian, median BMI: 27.3 [P25, P75:24.7, 31.2] comprised the analytic sample (Table 1). We present findings of biomarkers of immunity and neurodegeneration in relation to 1) circadian measures and 2) sleep measures as below.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics of analytic sample

| Total (n = 18) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Factor | n | |

| Demographics | ||

| Age | 18 | 69.5 [64.0, 72.0] |

| Sex | 18 | |

| Male | 10 (55.6) | |

| Female | 8 (44.4) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 18 | 27.3 [24.7, 31.2] |

| Education | 18 | 16.0 [14.0, 16.0] |

| Race | 18 | |

| White | 18 (100.0) | |

| Sleep measures | ||

| Apnea-Hypopnea index↑ | 18 | 12.0 [5.6, 18.8] |

| SaO2% <90↑ | 18 | 0.84 [0.14, 2.2] |

| Sleep efficiency, %* | 18 | 88.2 [82.2, 92.6] |

| Total sleep time, min* | 18 | 424.3 [292.7, 488.7] |

| Sleep Fragmentation index* | 18 | 4.4 [2.5, 9.9] |

| Wake episodes, number* | 18 | 12.6 [9.2, 19.5] |

| Circadian measures | ||

| Mesor, counts/min* | 18 | 129.9 [115.4, 139.7] |

| Amplitude, counts/min* | 18 | 103.4 [84.0, 124.1] |

| F-Ratio* | 18 | 3685 [2831, 5625] |

| Sleep Regularity index* | 18 | 60.9 [51.5, 65.3] |

| Interdaily stability* | 18 | 57.3 [48.5, 65.5] |

| Cognitive measures | ||

| APOE positive, % | 18 | 16 (88.9) |

| Aβ42, pg/ml | 18 | 335.1 [226.8, 382.0] |

| t-Tau, pg/ml | 18 | 527.0 [362.3, 719.2] |

| p-Tau, pg/ml | 18 | 82.5 [67.8, 97.9] |

| MMSE, score | 18 | 25.0 [20.0, 26.0] |

| DRS score | 18 | 125.0 [106.0, 133.0] |

| CDR-SB score | 17 | 3.0 [2.0, 4.0] |

Statistics presented as median [P25, P75], N (column %). BMI, body mass index; CDR-SB, Clinical Dementia Rating scale-Sum of Boxes; DRS, Dementia Rating Scale; MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Examination.

From overnight sleep study.

From actigraphy.

Circadian rhythm measures and biomarkers of inflammation, immunity, and neurodegeneration

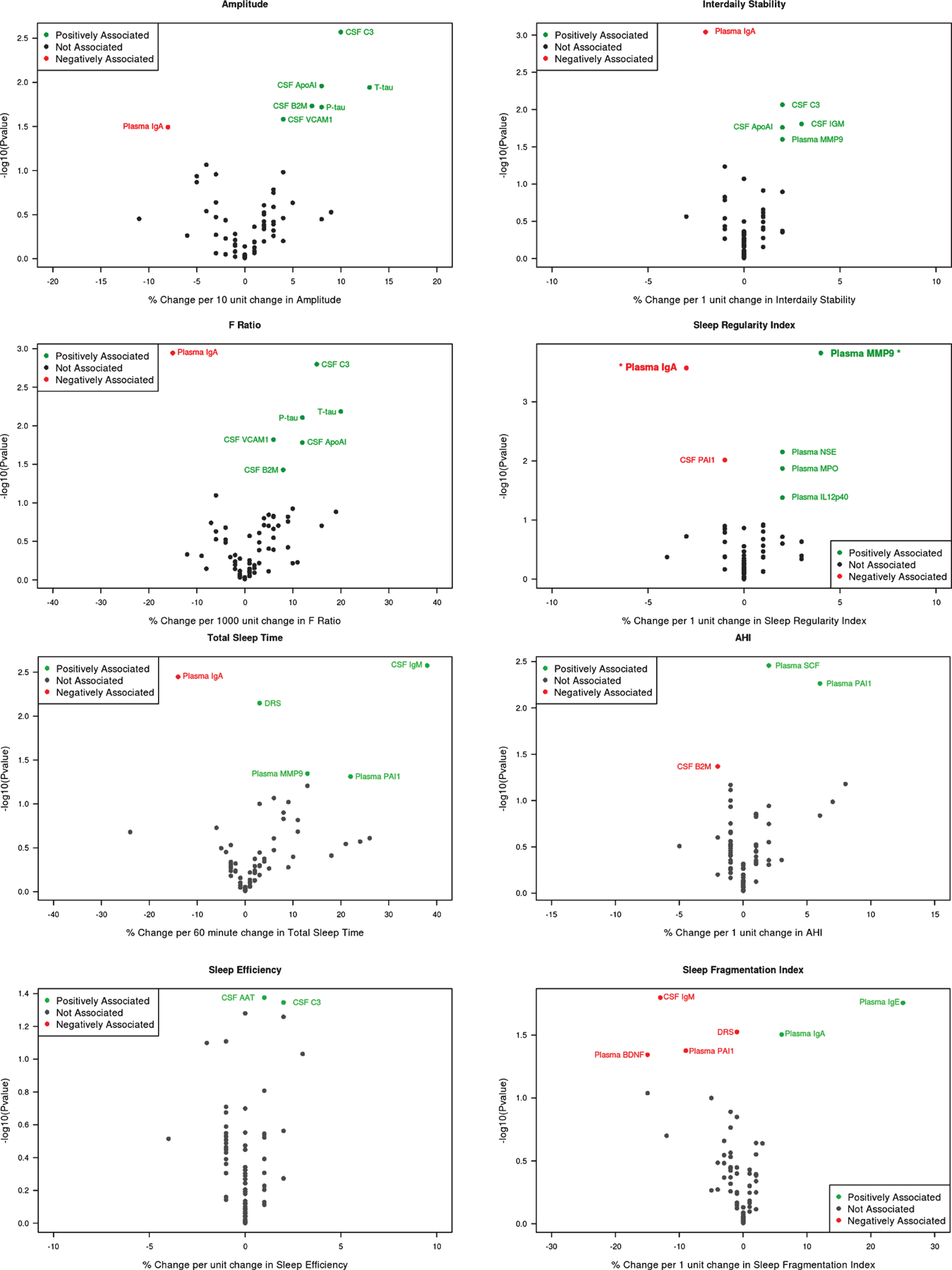

Circadian rhythm objective measures, i.e., actigraphy-based amplitude and F-ratio, showed internally consistent significant positive associations with increases in CSF (and not plasma) biomarkers of humoral immune activation, i.e., CSF complement (C3) (amplitude: 10% [95% CI: 4 to 16%] per 10 unit amplitude change, p = 0.003; F-ratio: 15% [6 to 24%] per 1000 unit F-ratio change, p = 0.002), apololipoprotein A-1 (Apo-A1) (amplitude: 8% [2 to 15%], p = 0.011; F-ratio: 12% [2 to 22%], p = 0.017), beta-2 microglobulin (B2M) (amplitude: 7% [1 to 12%], p = 0.019; F-ratio: 8% [1 to 17%], p = 0.037) as well as vascular cell adhesion molecule1 (VCAM1) (amplitude: 4% [1 to 8%], p = 0.026; F-ratio: 6% [1 to 12%], p = 0.015). Furthermore, amplitude and F-ratio were negatively associated with plasma IgA (Amplitude: −8% [−15 to −1%], p = 0.032; F-ratio: −15% [−22 to −7%], p = 0.001). Immune biomarkers, i.e., CSF complement C3, IgM, Apo-A1, and plasma matrix metalloproteinase (MMP9), were positively associated with interdaily stability, the latter also negatively associated with plasma IgA. The sleep regularity index was the only measure associated with biomarkers which retained significance after application of FDR specifically relative to plasma IgA: −3% [−5 to −2%] per unit change in sleep regularity index, p < 0.001) and MMP-9 (4% [2 to 5%], p < 0.001. Circulating and CSF biomarkers were not significantly associated with mesor and acrophase circadian rhythm measures except a positive association of mesor and plasma CCL-2, a chemokine. Notably, amplitude and F-ratio were both associated with CSF measures of neurodegeneration (t-tau and p-tau), but not amyloid (CSF Aβ42) (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Circadian and sleep measures and biomarkers of inflammation, immunity, and neurodegeneration. A) Circadian rhythm measures. B) Sleep measures. AAT, Alpha-1 antitrypsin; APO-A1, apolipoprotein A-I; B2M, Beta-2 microglobulin; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic growth factor; DRS, Dementia Rating Scale; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase; MPO, myeloperoxidase; NSE, nonspecific esterase; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule1. Sleep Regularity index biomarkers plasma IgA and MMP-9 are in bold and asterisk as remained significant after false discovery rate application.

Sleep measures and biomarkers of inflammation, immunity, and neurodegeneration

A profile emerged such that a greater number of immune markers were associated with circadian measures (as above) compared to sleep disruption. That said, SE and TST shared common patterns of alteration in immune mediators as observed with circadian measures, i.e., positive associations with CSF complement C3 (SE: 2% [0 to 4%] per unit change in SE, p = 0.045), IgM (TST: 38% [14 to 68%] per hour change in TST, p = 0.003), plasma MMP9 (TST: 13% [0 to 28%] per hour change in TST, p = 0.045) and negative association with plasma IgA (TST: −14% [−22 to −6%], p = 0.004). These sleep measures also had biomarker alterations distinct from the circadian measures, i.e., positive association with CSF alpha-1 antitrypsin (SE: 1% [0–2%], p = 0.042). SDB, defined by AHI, was associated with increased PAI-1 and SCF plasma levels. Sleep disruption, i.e., TST and SFI, showed a consistent association with poorer cognitive impairment, as defined by DRS score; findings not observed with circadian rhythm dysfunction (Fig. 1B).

Overall, all above results were not appreciably altered after isolated adjustment for age, sex, BMI, or education status individually.

DISCUSSION

In this first of its kind, unbiased examination of a multiplex panel of CSF and plasma biomarkers of immunity, inflammation and neurodegeneration relative to circadian and sleep disruption in MCI-AD, we identify circadian rhythm irregularities accompanied by 1) altered humoral immune responses in both the CSF and the plasma, i.e., circadian disruption was associated with altered immune profiles and 2) increased CSF neurodegeneration biomarkers (p-tau and t-tau). Alternatively, sleep disruption was 1) associated more so with abnormalities in primarily circulating plasma markers of immunity and inflammation, 2) not associated with neurodegeneration biomarkers, and 3) accompanied by further decrement in cognition among these MCI patients. Interestingly, Apo-A1, a biomarker best known for many of its HDL-related inflammation mitigating and atheroprotective properties [15], but related to increased risk of clinical progression among non-demented elderly APOE ε4 carriers with subjective cognitive decline [16], was associated with circadian dysfunction, thereby suggesting its role as a potential candidate analyte of interest.

Circadian and sleep disruption showed some shared apparent complementary alteration in biomarkers of immunity and inflammation, i.e., both accompanied with increases in complement C3, IgM, and plasma MMP9, and most notably, reduction in plasma IgA levels—the latter which remained robust to false discovery rate specific to the sleep regularity index. That said, distinctive profiles were also noted in terms of differential alteration in immunity, inflammation and neurodegeneration biomarkers related to circadian and sleep perturbations. These findings suggest in tandem interdependent and independent mechanisms of circadian and sleep disruption in AD pathophysiology.

Our preliminary data suggest that among patients in the symptomatic MCI stage of AD, those with abnormal circadian measures are in an immune-activated state as has been hypothesized [17] as well as a dysregulated circadian neurodegenerative state, whereas sleep disruption facilitates negative cognitive outcomes. It should be emphasized that the current work is discovery-based and hypothesis-generating. Future investigation of the neuroinflammatory changes in relation to circadian and sleep dysregulation along with AD biomarkers in presymptomatic AD could potentially impact AD pathology and the onset of cognitive decline. The role of the identified candidate biomarkers of neuroinflammation and immunity in the pathophysiology of sleep and circadian dysfunction-induced cognitive decline and neurodegeneration in AD and sleep and circadian disturbance as risk biomarkers or therapeutic targets warrants further study [18, 19].

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the patients who agreed to participate and acknowledge the contributions of the research management, coordinator, polysomnologist, and laboratory team to the study: Kylie Phillips, Joan Aylor, Rawan Nawabit, Jessica Lee and Samantha Wells and Christine Reece.

This work is supported by the Cleveland Clinic Catalyst award, the National Institute on Aging (1P30 AG062428-01, K23AG055685, R01AG022304), and the Alzheimer’s Association (2014-NIRG-305310).

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/20-1573r2).

REFERENCES

- [1].Wahl D, Solon-Biet SM, Cogger VC, Fontana L, Simpson SJ, Le Couteur DG, Ribeiro RV (2019) Aging, lifestyle and dementia. Neurobiol Dis 130, 104481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wong W (2020) Economic burden of Alzheimer disease and managed care considerations. Am J Manag Care 26, S177–S183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Musiek ES, Xiong DD, Holtzman DM (2015) Sleep, circadian rhythms, and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. Exp Mol Med 47, e148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Griffin P, Dimitry JM, Sheehan PW, Lananna BV, Guo C, Robinette ML, Hayes ME, Cedeno MR, Nadarajah CJ, Ezerskiy LA, Colonna M, Zhang J, Bauer AQ, Burris TP, Musiek ES (2019) Circadian clock protein Rev-erbalpha regulates neuroinflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 5102–5107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pillai JA, Maxwell S, Bena J, Bekris LM, Rao SM, Chance M, Lamb BT, Leverenz JB, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2019) Key inflammatory pathway activations in the MCI stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 6, 1248–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Irwin MR (2019) Sleep and inflammation: Partners in sickness and in health. Nat Rev Immunol 19, 702–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Morris JC (1993) The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology 43, 2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Marler MR, Gehrman P, Martin JL, Ancoli-Israel S (2006) The sigmoidally transformed cosine curve: A mathematical model for circadian rhythms with symmetric non-sinusoidal shapes. Stat Med 25, 3893–3904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Paudel ML, Taylor BC, Ancoli-Israel S, Blackwell T, Stone KL, Tranah G, Redline S, Cummings SR, Ensrud KE, Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study (2010) Rest/activity rhythms and mortality rates in older men: MrOS Sleep Study. Chronobiol Int 27, 363–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rogers-Soeder TS, Blackwell T, Yaffe K, Ancoli-Israel S, Redline S, Cauley JA, Ensrud KE, Paudel M, Barrett-Connor E, LeBlanc E, Stone K, Lane NE, Tranah G, Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study Research Group (2018) Rest-activity rhythms and cognitive decline in older men: The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Sleep Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 66, 2136–2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lunsford-Avery JR, Engelhard MM, Navar AM, Kollins SH (2018) Validation of the sleep regularity index in older adults and associations with cardiometabolic risk. Sci Rep 8, 14158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Van Someren EJ, Swaab DF, Colenda CC, Cohen W, McCall WV, Rosenquist PB (1999) Bright light therapy: Improved sensitivity to its effects on rest-activity rhythms in Alzheimer patients by application of nonparametric methods. Chronobiol Int 16, 505–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK (2015) limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43, e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gordon SM, Davidson WS (2012) Apolipoprotein A-I mimetics and high-density lipoprotein function. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 19, 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Slot RE, Van Harten AC, Kester MI, Jongbloed W, Bouwman FH, Teunissen CE, Scheltens P, Veerhuis R, van der Flier WM (2017) Apolipoprotein A1 in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma and progression to Alzheimer’s disease in non-demented elderly. J Alzheimers Dis 56, 687–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Irwin MR, Vitiello MV (2019) Implications of sleep disturbance and inflammation for Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Lancet Neurol 18, 296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Boespflug EL, Iliff JJ (2018) The emerging relationship between interstitial fluid-cerebrospinal fluid exchange, amyloid-beta, and sleep. Biol Psychiatry 83, 328–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cordone S, Annarumma L, Rossini PM, De Gennaro L (2019) Sleep and beta-amyloid deposition in Alzheimer disease: Insights on mechanisms and possible innovative treatments. Front Pharmacol 10, 695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]