Abstract

Background

Research suggests that individuals with low back pain (LBP) may have poorer motor control compared to their healthy counterparts. However, the sample population of almost 90% of related articles are young and middle-aged people. There is still a lack of a systematic review about the balance performance of elderly people with low back pain. This study aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to understand the effects of LBP on balance performance in elderly people.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis included a comprehensive search of PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases for full-text articles published before January 2020. We included the articles that 1) investigated the elderly people with LBP; 2) assessed balance performance with any quantifiable clinical assessment or measurement tool and during static or dynamic activity; 3) were original research. Two independent reviewers screened the relevant articles, and disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer.

Results

Thirteen case-control studies comparing balance performance parameters between LBP and healthy subjects were included. The experimental group (LBP group) was associated with significantly larger area of centre of pressure movement (P < 0.001), higher velocity of centre of pressure sway in the anteroposterior and mediolateral directions (P = 0.01 and P = 0.02, respectively), longer path length in the anteroposterior direction (P < 0.001), slower walking speed (P = 0.05), and longer timed up and go test time (P = 0.004) than the control group.

Conclusion

The results showed that balance performance was impaired in elderly people with LBP. We should pay more attention to the balance control of elderly people with LBP.

Keywords: Low back pain, Balance performance, Elderly people

Background

It was reported that the world’s population aged ≥60 years will triple by 2050 [1]. Rapidly growing aging populations have increased the prevalence of diseases such as musculoskeletal pain. The reported prevalence of muscular and skeletal pain is 65–85% in elderly people [2, 3], 36–70% of which had LBP [3, 4]. Low back pain was the most common health problem among older adults, results in pain and disability [5]. Moreover, elderly people with LBP are often underreported and inadequately provided with treatment [6]. Untreated or undertreated older individuals with LBP may experience sleep disturbances, limitations to their social and recreational activities, psychological distress, decreased cognition, rapid deterioration of functional ability, and falls subsequently causing great burdens on family and society [7–9].

Balance, which is fundamental to activities of daily living, is impaired in the patients with LBP [10]. Most functional tasks in daily life require balance control in the horizontal and vertical directions. Impaired balance is associated with poor motor control, the ability for one to maintain their balance and body orientation during locomotion [11]. Previous studies demonstrated that patients with LBP may have impaired motor control [12–14], which would further affect their balance performance and motor behaviour.

Balance dysfunction in the aging population is based on knowledge of the normal aging processes, loss of sensory elements, and loss of musculoskeletal function [15]. Balance performance declines with age due to biological changes (e.g. mobility, physical inactivity), which in turn could lead to falls [16, 17]. LBP is known to be an independent risk factor for recurrent falls in older women [18].

What is the effect of aging combined with LBP? Here we aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to understand the effects of low back pain in elderly people with the ultimate goal of providing better clinical research and treatment guidelines.

Methods

Literature search strategy

This review was conducted according to the guidelines outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement [19]. Two independent investigators screened the titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies to identify those appropriate for full-text review. Subsequently, they independently assessed the papers in full to identify the studies to be included in the analysis. Any disagreements about inclusion were resolved by discussion and through arbitration by a third reviewer.

Selection criteria

We included articles that:

Participants included elderly people with a mean age of ≥60 years who had chronic LBP;

For case-control study, participants included a control group of individuals healthy without LBP;

Outcome measures included a measure of balance performance (e.g. balance and gait) that uses highly valid and reliable methods (such as static and dynamic posturographic analyses, centre of pressure [COP] analysis, centre of gravity analysis, and timed up and go test) to access their dynamic or static balance or balance performance. All the articles had to have been available in the English language and published in full within a peer-reviewed journal;

studies that scored ≥4 on the Cross-sectional/Prevalence Study Quality scale (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, AHRQ) [20];

were written in English.

The following exclusion criteria were used:

Articles appeared only in abstract format or included insufficient detail to gauge study quality and extract results;

The articles were case reports or experimental studies.

Study selection

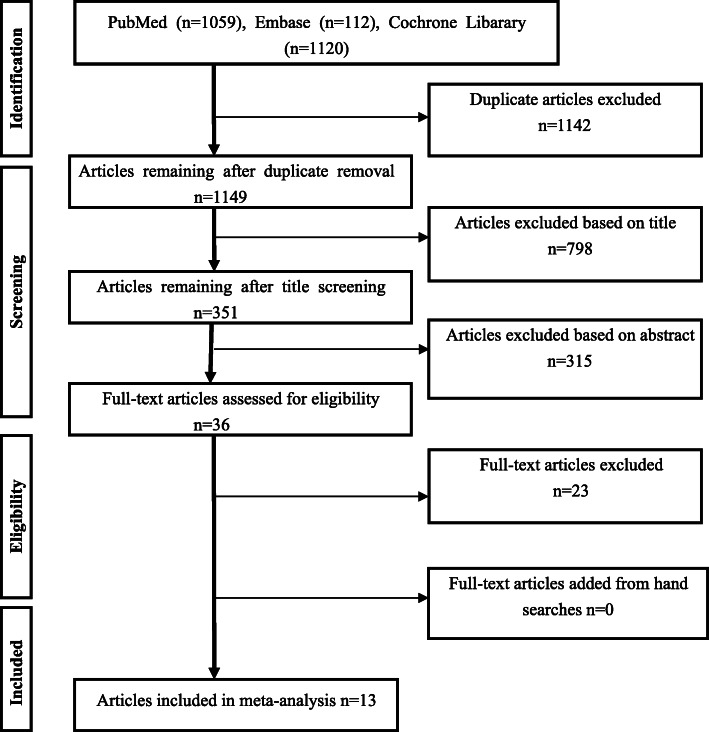

The search strategy is displayed in Fig. 1. Two reviewers independently screened all abstracts of articles potentially meeting the inclusion criteria. The full texts of those articles were subsequently reviewed. The reviewers then met with the entire review team and resolved any disagreements via consensus. The initial search yielded 2291 publications. Following the title and abstract screening, 35 full-text articles were retrieved. The full-text review was completed to determine final inclusion; 13 articles case-control studies [21–33] met the inclusion criteria.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the article screening and selection process

Quality assessment

Quality was assessed using the Cross-sectional/Prevalence Study Quality (AHRQ) [20], which has 11 tests and a total score of 11 points. The two researchers independently evaluated all studies that met the inclusion criteria; there were no significant intergroup differences.

Data extraction

For each study that met the full inclusion and exclusion criteria, information regarding study design and outcome measures (e.g. COP, one-leg stance time) were extracted. The major results of each study focusing on balance function were briefly summarised. The meta-analysis data were collected from the results sections and tables of the manuscripts. The graphs were also used to extrapolate the data. If it was impossible to collect the data from the manuscript, the corresponding author of the manuscript was contacted twice before the study was excluded.

Results

Search findings

Figure 1 illustrates the search findings. The initial search yielded 2291 articles. After the two round of screening, 13 case-control studies that compared balance performance for elderly adults with LBP and healthy participants were remained. Data from the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Six studies use the COP parameters to evaluated the the balance performance of the participants [23,25.26,27,29,32]. Two studies use the relative proprioceptive weighting (RPW) [22, 24]. Three studies use the TUG test [21, 26]. And three studies use the gait parameters [28, 30, 31].

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of included case-control studies

| References Design | Basic data of Participant | Balance task | Outcome measure (balance performance) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBP | Health | Source of participants | ||||||

| Age (mean ± SD) | N | Age (mean ± SD) | N | |||||

| Yi-Liang(2015) [21] | case-control | 60.5(4.1) | 13 | 59.7 (3.0) | 13 | local communities and affiliated hospital | Single-leg standing |

TUG STS |

| Ito(2018) [22] | case-control | 75.5 (5.1) | 28 | 73.7 (5.7) | 46 |

Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabitation |

eyes closed Muscle Vibration |

RPW |

| Brumagne (2004) [23] | case-control | 63 | 10 | 63 | 10 |

Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation |

1. control (no vibration); 2. bilateral vibration of thetriceps surae tendons; 3. bilateral vibration of the Tibialis anterior tendons; 4. bilateral vibration of the Paraspinal muscle bellies |

COP |

| Ito(2017) [24] | case-control | 76.7 (4.2) | 47 | 73.8 (4.9) | 64 |

NationalCenter for Geriatric and Gerontology |

Muscle Vibration | RPW |

| Lee(2016) [25] | case-control | 64.5 (5.7) | 30 | 66.2 (4.5) | 26 |

University Hospital, local communities, and around the campus |

Postural perturbation | COP |

| Iversen(2009) [26] | case-control | 75.5 (5.1) | 28 | 73.7 (5.7) | 46 | tertiary care spine center | static standing |

TUG COP |

| Kendall(2018) [27] | case-control | 82.4 (4.6) | 24 | 81.1 (4.3) | 19 |

a preventative home visit program |

static standing | COP |

| Sung(2017) [28] | case-control | 65.1 (13.5) | 51 | 63.6 (15) | 59 | community | walk | gait parameters |

| Lihavainen(2010) [29] | case-control | 80.6 (4.8) | 291 | 80.1 (4.4) | 314 | all the inhabitants of thecity in Finland |

static standing eyes open eyes close Feet together |

COP |

| Champagne(2012) [30] | case-control | 68.9 (6.6) | 15 | 69.4 (6.4) | 15 | local community | – |

TUG One-leg stance Walking speed |

| Hicks(2018) [31] | case-control | 69.3 (6.7) | 54 | 71.1 (6.8) | 54 | community | walk | gait parameters |

| Silva(2016) [32] | case-control | 70.0(8) | 10 | 73.0 (7) | 10 | local community | one-leg stance | COP |

| Kato(2019) [33] | case-control | 77.4 (4.2) | 21 | 78.1 (4.4) | 17 | outpatient of hospital | one-leg standing | standing time |

N number of participants in the study, COP centre of pressure, RPW relative proprioceptive weighting, STS sit-to-stand test, TUG timed up and go test. LBP low back pain participants, Health healthy participants without low back pain

In order to efficiently reduce the risks of bias, the studies had to score ≥ 4 on AHRQ scale to be included in the review. The individual scores attained by the studies using the AHRQ scale are reported in Tables 2. The average AHRQ score for the 13 included studies was computed to be 5.6 out of 11, indicating fair quality of the overall studies.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of included studies

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Item | Score | ||||||||||

| Define source of information (survey or review) | List inclusion and exclusion criteria for exposed and unexposed subjects (cases and controls) or refer to previous publications |

Indicate time period used to identify patients |

Indicate whether subjects were consecutive if not population- based |

Indicate if evaluators of subjective components of study were masked to, Other aspects of the status of the participants | Describe any assessments undertaken for quality assurance purposes | Explain any patient exclusions from analysis | Describe how confounding variables were assessed or controlled for | If applicable, explain how missing data were handled in the analysis | Summarise patient response rate and completeness of data collection | Clarify what follow-up, if any, was expected and the percentage of patients for whom incomplete data or follow-up was obtained | ||

| Yi-Liang (2015) [20] | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | 6 |

| Ito (2018) [21] | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | N | N | U | Y | N | 5 |

| Brumagne (2004) [22] | Y | N | N | N | U | Y | N | Y | U | Y | N | 4 |

| Ito (2017) [23] | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | N | Y | U | Y | N | 6 |

| Lee (2016) [24] | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | 6 |

| Iversen (2009) [25] | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | 6 |

| Kendall (2018) [26] | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | 6 |

| Sung (2017) [27] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | 7 |

|

Lihavainen (2010) [28] |

Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | 6 |

|

Champagne (2012) [29] |

Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | 6 |

| Hicks (2018) [30] | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | 5 |

| Silva (2016) [31] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | 6 |

| Kato (2019) [32] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | U | N | Y | N | 5 |

N NO, Y YES, U UNCLEAR

Outcomes

One-leg stance

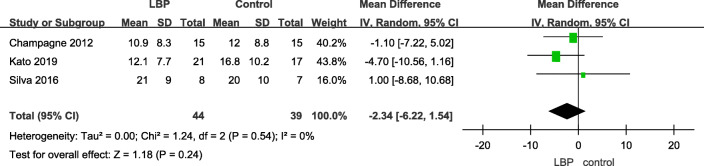

A total of four articles used one-leg stance time to assess the balance function of patients with LBP and their healthy counterparts; however, one just calculated the number of people who stood on a single leg for 20 s; therefore, we extracted data from three articles. No significant difference was noted between the two groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

One-leg stance

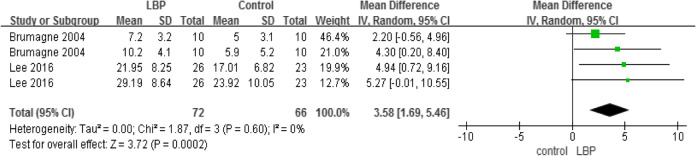

COP area

A total of four studies used COP parameters to measure balance performance, which was recognised as a valid and reliable method. The larger the COP area was, the worse the balance performance was. Older adults with LBP had a longer path length and larger area of COP movements than older adults without LBP (Table 4).

Table 4.

Centre of pressure area

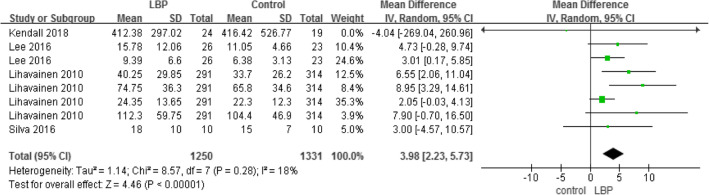

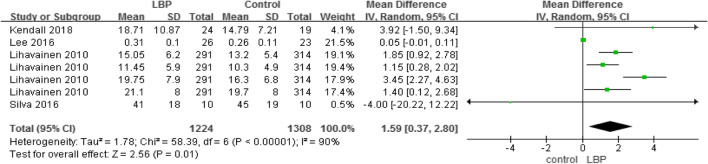

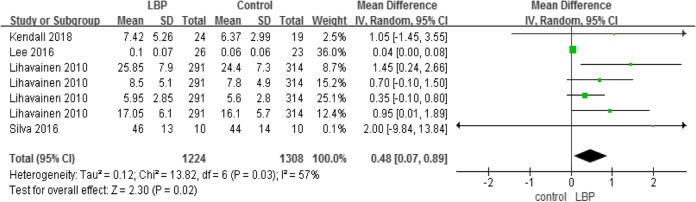

COP anteroposterior velocity, mediolateral velocity, and anteroposterior range

A total of four studies used COP sway velocity parameters to measure motor control (Tables 5 and 6), while two studies used COP sway range parameters to measure motor control (Table 7). The higher the COP sway velocity and the longer path length in the anteroposterior direction was, the more unstable the individual was. The three parameters also demonstrated that older adults with LBP would have higher velocity and larger COP movements than older adults without LBP.

Table 5.

Centre of pressure, anteroposterior velocity

Table 6.

Centre of pressure, mediolateral velocity

Table 7.

Centre of pressure, anteroposterior range

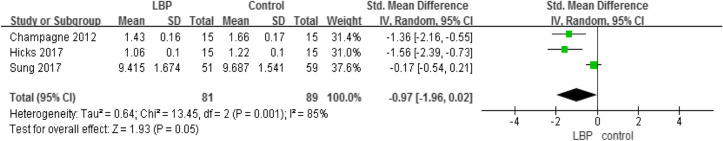

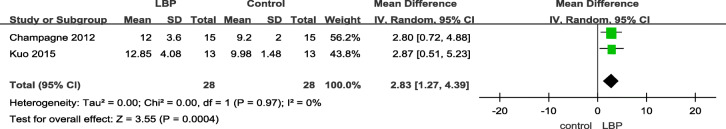

Gait (speed) and TUG

A total of three studies used the gait test (Table 8) and two studies used the TUG (Table 9) to compare the dynamic balance between individuals with LBP and those without LBP. The result showed that, compared to healthy individuals, patients with LBP walked more slowly and needed more time to complete the TUG test.

Table 8.

Gait speed

Table 9.

Timed up and go test

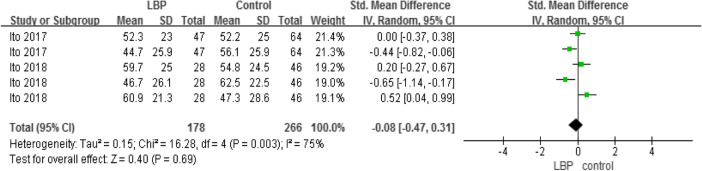

Relative proprioceptive weighting

Two studies compared the RPW between the two groups but found no significant intergroup difference (Table 10).

Table 10.

Relative proprioceptive weighting

Outcomes measures, risk bias of the studies included in the meta-analysis and sensitivity analysis

Using STATA software to assess the study biases and sensitivity analysis (Table 11), the sensitivity results suggested that our meta-analysis results are relatively stable.

Table 11.

Outcomes measures, risk bias of the studies included in the meta-analysis and sensitivity analysis

| outcomes | References | Design | P value | Egger’s test (P value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-leg stance |

Champagne(2012) [30] Silva(2016) [32] Kato(2019) [33] |

case-control | P = 0.24 | 0.365 |

| COP area |

Lee(2016) [25] Kendall(2018) [27] Lihavainen(2010) [29] Silva(2016) [32] |

case-control | P < 0.01 | 0.273 |

| COP AP velocity |

Lee(2016) [25] Kendall(2018) [27] Lihavainen(2010) [29] Silva(2016) [32] |

case-control | P = 0.01 | 0.929 |

| COP ML velocity |

Lee(2016) [25] Kendall(2018) [27] Lihavainen(2010) [29] Silva(2016) [32] |

case-control | P = 0.02 | 0.161 |

| COP AP range |

Brumagne(2004) [23] Lee(2016) [25] |

case-control | P < 0.01 | 0.184 |

| Gait |

Sung(2017) [28] Hicks(2018) [31] Champagne(2012) [30] |

case-control | P = 0.05 | 0.037 |

| TUG |

Yi-Liang(2015) [21] Iversen(2009) [26] Champagne(2012) [30] |

case-control | P < 0.01 | 0.317 |

| RPW |

Ito(2018) [22] Ito(2017) [24] |

case-control | P = 0.69 | 0.682 |

COP centre of pressure, RPW relative proprioceptive weighting, AP anteroposterior, ML mediolateral, TUG timed up and go test

Discussion

This meta-analysis, which identified 13 case-control studies that compared balance performance for elderly adults with LBP and healthy participants. The qualities of all the case-control studies were moderate. The risk of bias was assessed for each article using the Cochrane Collaboration recommendations, the sensitivity results suggested that our meta-analysis results seem to be stable.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to focus on LBP and balance performance in elderly people. This systematic review aimed to estimate the effect of LBP on balance performance in elderly people. Our results demonstrated that elderly people with LBP have poorer balance performance than those without LBP. With the rapidly aging society, the proportion of elderly patients with chronic LBP is increasing annually, which lead to bad moods, functional inactivity, a decrease in quality of life, and an increase in fall risk. [34]. It is necessary to provide effective intervention measures to improve elderly peoples’ quality of life and reduce the economic losses and physical and emotional trauma caused by chronic LBP.

The aging process results in changes in the central nervous system, peripheral nervous system, and the musculoskeletal system [35, 36]. Pain itself has a wide range of effects on motor function [37]. People who experience chronic pain display changes in motor patterns, exercise coordination, and the ability to maintain stability in response to external disturbances. Pain induces spinal motility restrictions, lumbar proprioceptive losses, weakening of lower-extremity sensory feedback, and trunk muscle weakness and atrophy [26, 28, 29, 32]. Thus, when aging is combined with LBP, balance performance becomes worse. However, almost 90% of articles to date focused on young and middle-aged people. It is conceivable that conditions associated with younger and middle-aged people are more optimistic regardless of the balance performance or responsive to treatment. It is also possible that older adults with LBP should be subjected to different assessments and interventions than younger adults to account for the differences in therapeutic approaches and treatment outcomes. Given the age disparities in LBP people, in addition to solving the pain issue, it is important to focus on the balance performance of older individuals. As we all know, balance control with age is among the major risk factors for falls, which is a difficult problem that the world faces, especially as the population continues to age [38].

Poor balance performance in elderly people with LBP means they could not perform accurate movements and ambulation [39, 40], which in turn affected their physical activities. In the present study, TUG, one-leg stance, postural sway, and gait are reliable and valid fall-risk assessments [41–44], poor outcomes on the TUG and postural sway tests may indicate an increased risk of falling that could lead to disastrous consequences. Problems with balance performance were also reportedly associated with fall risk [45]. Physical therapists in the clinical setting should be aware of an increased risk of falling for their patients with LBP.

There is some evidence that LBP impacts the equilibrium of older individuals. However, only one study in this review assessed reactive balance control, which assessed the postural responses to a suddenly released pulling force in older adults with LBP [24]. The results showed older adults with LBP had poorer postural responses in delayed reaction, larger displacement, higher velocity, longer path length, and greater COP sway area compared to the older healthy controls. The outcome parameters assessed in Lee et al’s [24] study were similar to those used in present study. Sudden postural perturbations are very common during everyday life, such as pulling an object that might suddenly move or open, poorer reactive balance control is important to maintain balance in the sudden postural perturbation, which could reduce the falling risk. Besides the reactive balance control, it is also very common for postural tasks to be accompanied with cognitive tasks (e.g., making a telephone call while walking) in daily life. Understanding of the effects of dual tasks on static and dynamic balance performance among older individuals with LBP could help reduce the occurrence of falls for the elderly people. However, none study assessed the effect of dual tasks on balance performance in older individuals with LBP. Future studies must focus more on this issue, especially on motor performance or balance function in these patients. The results of this review depended on the outcome measures examined in the reviewed articles, and the small sample sizes may have limited the power of our findings. Therefore, future research should include adequate sample sizes and must be combined with myoelectric and neural electrical activity and gait analyses to evaluate dynamic-static equilibrium and reactive balance, which could better reflect the effect of the central nervous system on peripheral control.

Study limitations

This review included only case-control studies. Furthermore, the present review did not incorporate non-English studies. This may limit the validity of our findings and must be taken into consideration when interpreting its overall generalizability. The limited number of case-control studies did not allow a subgroup meta-analysis. However, we achieved the main aim of our review, which was to estimate the effect of LBP on balance performance in elderly people.

Conclusion

In summary, the study results indicate evidence in favour of a negative effect of LBP on balance performance in elderly people with LBP. Future studies should focus on the mechanisms and effective interventions for abnormal balance control in elderly people with LBP.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- LBP

Low back pain

- COP

Centre of pressure

- RPW

Relative proprioceptive weighting

- AP

Anteroposterior

- ML

Mediolateral

- TUG

Timed up and go test

- STS

Sit-to-stand test

- AHRQ

Cross-sectional/Prevalence Study Quality

- PRISMA

Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis

Authors’ contributions

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and all authors approved the final version to be published.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors approved the final version to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nations, B.U. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Ageing 2009. Popul Dev Rev. 2011;37.

- 2.Bressler HB, Keyes WJ, Rochon PA, Badley E. The prevalence of low back pain in the elderly. A systematic review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24(17):1813–1819. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199909010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podichetty VK, Mazanec DJ, Biscup RS. Chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal pain in older adults: clinical issues and opioid intervention. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79(937):627–633. doi: 10.1136/pmj.79.937.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edmond SL, Felson DT. Prevalence of back symptoms in elders. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(1):220–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, Woolf A, Vos T, Buchbinder R. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(6):2028–2037. doi: 10.1002/art.34347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molton IR, Terrill AL. Overview of persistent pain in older adults. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):197–207. doi: 10.1037/a0035794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, Hoy D, Karppinen J, Pransky G, Sieper J, Smeets RJ, Underwood M, Lancet Low Back Pain Series Working Group What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2356–2367. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Q, Hayman LL, Shmerling RH, Bean JF, Leveille SG. Characteristics of chronic pain associated with sleep difficulty in older adults: the maintenance of balance, independent living, intellect, and zest in the elderly (MOBILIZE) Boston study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(8):1385–1392. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodges PW, Richardson CA. Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain. A motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21(22):2640–2650. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199611150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nies N, Sinnott PL. Variations in balance and body sway in middle-aged adults. Subjects with healthy backs compared with subjects with low-back dysfunction. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991;16(3):325–330. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199103000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piscitelli D. Motor rehabilitation should be based on knowledge of motor control. Arch Physiother. 2016;6:5. doi: 10.1186/s40945-016-0019-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodges PW, Richardson CA. Altered trunk muscle recruitment in people with low back pain with upper limb movement at different speeds. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(9):1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsao H, Galea MP, Hodges PW. Reorganization of the motor cortex is associated with postural control deficits in recurrent low back pain. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 8):2161–2171. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsao H, Druitt TR, Schollum TM, Hodges PW. Motor training of the lumbar paraspinal muscles induces immediate changes in motor coordination in patients with recurrent low back pain. J Pain. 2010;11(11):1120–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stelmach GE, Teasdale N, Di Fabio RP, Phillips J. Age related decline in postural control mechanisms. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1989;29(3):205–223. doi: 10.2190/KKP0-W3Q5-6RDN-RXYT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan DCL, Wong TWL, Zhu FF, Cheng Lam C, Young WR, Capio CM, Masters RSW. Investigating changes in real-time conscious postural processing by older adults during different stance positions using electroencephalography coherence. Exp Aging Res. 2019;45(5):410–423. doi: 10.1080/0361073X.2019.1664450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duarte M, Sternad D. Complexity of human postural control in young and older adults during prolonged standing. Exp Brain Res. 2008;191(3):265–276. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muraki S, Akune T, Oka H, En-Yo Y, Yoshida M, Nakamura K, Kawaguchi H, Yoshimura N. Prevalence of falls and the association with knee osteoarthritis and lumbar spondylosis as well as knee and lower back pain in Japanese men and women. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(10):1425–1431. doi: 10.1002/acr.20562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation [published correction appears in BMJ. 2016 Jul 21;354:i4086] BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stephenson J. AHRQ director sets course for Agency's health services research. JAMA. 2016;316(16):1632–1634. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuo YL, Huang KY, Chiang PT, Lee PY, Tsai YJ. Steadiness of Spinal Regions during Single-Leg Standing in Older Adults with and without Chronic Low Back Pain. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0128318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito T, Sakai Y, Morita Y, et al. Proprioceptive Weighting Ratio for Balance Control in Static Standing Is Reduced in Elderly Patients With Non-Specific Low Back Pain [published correction appears in Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2020 May 15;45(10):E606] Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018;43(24):1704–1709. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brumagne S, Cordo P, Verschueren S. Proprioceptive weighting changes in persons with low back pain and elderly persons during upright standing. Neurosci Lett. 2004;366(1):63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito T, Sakai Y, Yamazaki K, Igarashi K, Sato N, Yokoyama K, Morita Y. Proprioceptive change impairs balance control in older patients with low back pain. J Phys Ther Sci. 2017;29(10):1788–1792. doi: 10.1589/jpts.29.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee PY, Lin SI, Liao YT, et al. Postural Responses to a Suddenly Released Pulling Force in Older Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain: An Experimental Study. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0162187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iversen MD, Kale MK, Sullivan JT., Jr Pilot case control study of postural sway and balance performance in aging adults with degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2009;32(1):15–21. doi: 10.1519/00139143-200932010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kendall JC, Hvid LG, Hartvigsen J, Fazalbhoy A, Azari MF, Skjødt M, Robinson SR, Caserotti P. Impact of musculoskeletal pain on balance and concerns of falling in mobility-limited, community-dwelling Danes over 75 years of age: a cross-sectional study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30(8):969–975. doi: 10.1007/s40520-017-0876-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sung PS, Zipple JT, Danial P. Gender differences in asymmetrical limb support patterns between subjects with and without recurrent low back pain. Hum Mov Sci. 2017;52:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lihavainen K, Sipilä S, Rantanen T, Sihvonen S, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Contribution of musculoskeletal pain to postural balance in community-dwelling people aged 75 years and older. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(9):990–996. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Champagne A, Prince F, Bouffard V, Lafond D. Balance, falls-related self-efficacy, and psychological factors amongst older women with chronic low Back pain: a preliminary case-control study. Rehabil Res Pract. 2012;2012:430374. doi: 10.1155/2012/430374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hicks GE, Sions JM, Coyle PC, Pohlig RT. Altered spatiotemporal characteristics of gait in older adults with chronic low back pain. Gait Posture. 2017;55:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.da Silva RA, Vieira ER, Carvalho CE, Oliveira MR, Amorim CF, Neto EN. Age-related differences on low back pain and postural control during one-leg stance: a case-control study. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(4):1251–1257. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-4255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato S, Murakami H, Demura S, et al. Abdominal trunk muscle weakness and its association with chronic low back pain and risk of falling in older women. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):273. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2655-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fehlings MG, Tetreault L, Nater A, et al. The aging of the global population: the changing epidemiology of disease and spinal disorders. Neurosurgery. 2015;77(Suppl 4):S1–S5. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burns ER, Stevens JA, Lee R. The direct costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults - United States. J Saf Res. 2016;58:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F, Foschi R, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2010;21(5):658–668. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e89905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JK, Desmoulin GT, Khan AH, Park EJ. Comparison of 3D spinal motions during stair-climbing between individuals with and without low back pain. Gait Posture. 2011;34(2):222–226. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheffer AC, Schuurmans MJ, van Dijk N, van der Hooft T, de Rooij SE. Fear of falling: measurement strategy, prevalence, risk factors and consequences among older persons. Age Ageing. 2008;37(1):19–24. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nelson-Wong E, Poupore K, Ingvalson S, Dehmer K, Piatte A, Alexander S, Gallant P, McClenahan B, Davis AM. Neuromuscular strategies for lumbopelvic control during frontal and sagittal plane movement challenges differ between people with and without low back pain. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2013;23(6):1317–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crosbie J, Nascimento DP, Filho Rde F, Ferreira P. Do people with recurrent back pain constrain spinal motion during seated horizontal and downward reaching? Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2013;28(8):866–872. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kojima G, Masud T, Kendrick D, et al. Does the timed up and go test predict future falls among British community-dwelling older people? Prospective cohort study nested within a randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:38. Published 2015 Apr 3. doi:10.1186/s12877-015-0039-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Dohrn IM, Hagströmer M, Hellenius ML, Ståhle A. Gait speed, quality of life, and sedentary time are associated with steps per day in community-dwelling older adults with osteoporosis. J Aging Phys Act. 2016;24(1):22–31. doi: 10.1123/japa.2014-0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas JI, Lane JV. A pilot study to explore the predictive validity of 4 measures of falls risk in frail elderly patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(8):1636–1640. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tucker MG, Kavanagh JJ, Morrison S, Barrett RS. What are the relations between voluntary postural sway measures and falls-history status in community-dwelling older adults? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(5):750–758. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim BJ, Robinson CJ. Postural control and detection of slip/fall initiation in the elderly population. Ergonomics. 2005;48(9):1065–1085. doi: 10.1080/00140130500071028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.