Abstract

BACKGROUND

Retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) has been proven to be a safe and effective treatment modality in large-scale quantitative studies. However, although its safety profile has been established, it also has a potential risk of life-threatening complications. We here describe our experience with a patient who developed a huge periureteral hematoma after RIRS with holmium laser lithotripsy.

CASE SUMMARY

A 73-year-old woman visited our center with a complaint of gross hematuria. An enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 1.5-cm left renal pelvis stone with hydronephrosis. The patient underwent RIRS. During the surgery, a 12/14-Fr ureteral access sheath was applied and a 6-Fr ureteral catheter was indwelled thereafter. On postoperative day 1, she experienced aggravated left flank pain and left lower-quadrant tenderness without rebound tenderness. A follow-up CT scan was taken, which revealed a huge hematoma in the periureteral space, not in the perirenal space, with suspicious contrast medium extravasation. Immediate angiography was performed; however, it showed no evidence of active bleeding. She was conservatively managed with hydration and antibiotic and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy, and was discharged on postoperative day 7. However, she visited our outpatient department with recurrent left flank pain at 5 d from discharge. Ultrasonography confirmed that the double J-stent was intact. To rule out stent malfunction, the stent was changed. Decreased size of the hematoma was observed in the imaging studies, and conservative management for candiduria was performed for 1 wk.

CONCLUSION

Although RIRS is an effective and safe procedure for the management of renal stones, clinicians should be aware of its potential complications.

Keywords: Retroperitoneal hematoma, Ureteral access sheath, Retrograde intrarenal surgery, Acute complication, Case report

Core Tip: Retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) is known as an effective and safe procedure for the management of renal stones. Most of the cases shows excellent clinical outcome, while life threatening complications may occur in some cases. During RIRS, ureteral access sheath (UAS) helps surgeon to reduce operative time as well as potential complications associated with stone retrieval. However, we should remember to manipulate UAS carefully, due to its own risk of ureteral tearing. This case emphasize us to pay attention to acute postoperative pain even after successful RIRS. Additionally, the useful diagnostic suggestions are mentioned based on our experience.

INTRODUCTION

Since the first flexible ureteroscopic procedure was performed in the 1960s, the continuous development of instruments, in terms of image quality, durability, and deflection, has made it possible to apply flexible ureterorenoscopic procedures as a standard management of larger or multiple stones within the kidney. Retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) has been proven to be a safe and effective treatment modality in large-scale quantitative studies[1]. However, although its safety profile has been established, it also has a potential risk of life-threatening complications[2].

A ureteral access sheath (UAS) is an essential device for flexible ureteroscopy during RIRS for removing renal stones. However, several complications have been reported, such as ureteral wall injuries during the manipulation of the tool. Such injuries are usually confined to the ureteral mucosa, causing hematuria and/or catastrophic stricture.

We here describe our experience with a patient who developed a huge periureteral hematoma after RIRS with holmium laser lithotripsy.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 73-year-old woman was referred to our department with painless gross hematuria persisting for 2 wk.

History of present illness

It was first event, and she had not suffered from recurrent symptomatic cystitis before.

History of past illness

She had a medical history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and recurrence-free breast and thyroid cancer. Furthermore, she was taking aspirin (100 mg/d) to manage an underlying disease (polycythemia vera).

Physical examination

Physical examination showed no abnormal findings.

Laboratory examinations

Microscopic urinalysis revealed moderate hematuria (red blood cell count, 30-50 per high-power field) and scanty pyuria (white blood cell count, 2-4 per high-power field). Pre-operative serum creatinine was 0.78 mg/dL, hemoglobin was 17.5 g/dL, and hemostatic profiles were normal range. Prothrombin time international normalized ratio was 1.02.

Imaging examinations

Enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed a 1.5-cm left renal pelvis stone with moderate hydronephrosis.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The cause of persisting hematuria was renal pelvis stone.

TREATMENT

For definite treatment, the patient was scheduled for RIRS. Initially, the stone was identified using a semi-rigid ureterorenoscope. No significant ureteral stricture was found, allowing the endoscope to pass through the entire ureter. A 12/14-Fr UAS was introduced over a Bentson guide wire up to the ureteropelvic junction. Thereafter, a laser fiber (multi-use Holmium laser fiber, 365 μm) was introduced and used under clear vision. The problematic stone was removed through fragmentation with extraction and the dusting technique. The presence of remnant stone and ureteral injury was examined under a ureterorenoscope at the end of the surgery, and a double J-stent catheter (6 Fr/24 cm) was placed under C-arm fluoroscopy. Overall, no detrimental events occurred during the surgery (operative time, 1 h).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

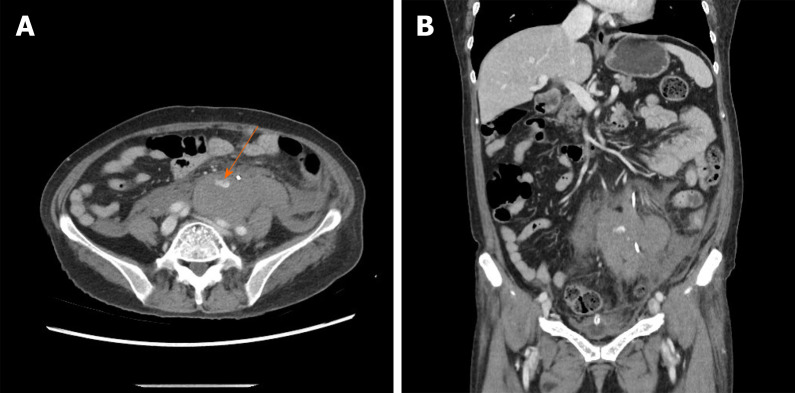

The patient complained of severe left lower-quadrant abdominal pain after the surgery, which was not effectively controlled with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or narcotics. Post-operative day one hemoglobin was 13.8 g/dL, and a bulging lesion was observed in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen. As the pain was constant, immediate CT with contrast was performed. An about 10-cm hematoma was identified in the retroperitoneum around the left mid-ureter, and contrast medium extravasation was observed at the level of the distal ureter, suggesting active bleeding (Figure 1). For further evaluation of other potential injury, angiography focused on the left internal, external iliac, and gonadal arteries was performed. However, no obvious bleeding focus was identified. The pain subsided over time. After 2 mo of follow up, the retroperitoneal hematoma was nearly resolved. No hydronephrosis developed for 1 year after the sequential removal of the ureteral stent.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scans showing a periureteral hematoma in transverse view and coronal view. A: Transverse view computed tomography scan. The orange arrow marks the extravasation of contrast medium; B: Coronal view computed tomography scan.

DISCUSSION

The general trend of minimally invasive surgery is still upward in recent years, which is also true for the field of urology. And this new trends underwent substantial changes not only in the treatment of nephrolithiasis but also benign renal cysts and genitourinary malignancies[3]. RIRS has become an important option for the treatment of renal stones, as its overall feasibility and safety have been verified in previous studies[4-6]. Relatively few studies on mortality and morbidity after RIRS have been published[7,8]. Those studies demonstrated low complication rates after RIRS and the majority of them were Clavien grade I or II. However, RIRS can have rare but life-threatening complications. The complications have shown diverse patterns, including flank pain, hematuria, urinary retention, steinstrasse, hematoma, urinoma, urinary tract infection, fever, and sepsis[9-11]. Bleeding problems often occur as a result of direct mechanical trauma during the manipulation of instruments (stiff guide wire, access sheath, ureterorenoscope, etc.) or because of increased intrarenal pressure.

The patient in our case experienced left lower-quadrant pain after a successful and uneventful RIRS. We didn’t perform retrograde pyelography as a routine procedure, but ureteroscopic examination just before indwelling double J-stent was undertaken, and there was not significant ureteral wall injury at that time. This nonspecific symptom could be considered irrelevant immediately after the surgery. The amount of hematuria was scant, and routine postoperative laboratory tests were unremarkable. However, the pain was resistant to drugs, which mandated further evaluation with CT.

UAS was first used in performing ureteroscopy in 1974. It is now an essential device for RIRS, which is the first-choice treatment for small renal stones. UAS helps the flexible ureterorenoscope in approaching the pelvicalyceal system, securing an adequate diameter to achieve easier stone fragmentation and retrieval in a clear view[12,13]. Conversely, Lallas et al[14] reported that the use of UAS has a risk of inducing overdistention of the ipsilateral ureter, causing ischemic change and generating toxic molecules such as free radicals.

Traxer and Thomas[6] classified ureteral wall injuries according to five grades using visual assessment with ureteroscopy. Several studies have reported that possible injuries are commonly confined to the mucosa[15]. However, severe complications have also been reported, such as ureteral wall injuries during the manipulation of the UAS. Prolonged hematuria, clot retention, intractable ureteral stricture, and urinary extravasation are potential major postoperative concerns[16].

Unusually, our patient did not show any detectable abnormality on direct visual inspection postoperatively. A huge hematoma in the retroperitoneum with extravasation of contrast medium was detected near the distal ureter on the CT scan taken for the evaluation of persistent abdominal pain. However, there was no definite evidence of active bleeding on arteriography, which correlated with the CT findings, after RIRS. On the basis of these results, it can be assumed that the injury occurred in the outer layer of the ureteral wall, such as the muscle layer or periureteral vasculature, without significant mucosal disruption.

Immediate CT scan helped in diagnosing massive hematoma, a rare complication of RIRS, when severe abdominal pain occurred and a palpable mass was found in the left lower-quadrant area after the surgery. As the hemorrhage was controlled with tamponade in the enclosed retroperitoneal space, the abdominal pain and the extent of hematoma gradually improved. No additional procedure was necessary.

To prevent ureteral injury during RIRS using a UAS, a prior examination with a semi-rigid ureteroscope should be considered to detect an unpredicted ureteral stricture and decide the appropriate size and length of the UAS. A gentle procedure with a large amount of lubricant is essential when passing the UAS through the physiologically narrow and curved course of the ureter (especially the ureterovesical junction). Some authors recommended preoperative ureteral stent indwelling to reduce the risk of ureteral injury[6]. In selective cases, based on the complexity of stone characteristics (size, number, location, previous stone or infection history, etc.), this pre-stenting procedure may be recommended despite its potential low cost efficiency.

CONCLUSION

This case revealed that life-threatening complications can occur after RIRS, even during the process of access sheath manipulation. All factors should be considered to predict and prevent potential complications such as massive hemorrhage, urosepsis, and respiratory failure associated with anesthesia. Better and standardized practices are needed to minimize such problems.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: October 8, 2020

First decision: January 17, 2021

Article in press: April 12, 2021

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cassell III AK S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL

Contributor Information

Taesoo Choi, Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 05278, South Korea.

Jeonghyouk Choi, Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 05278, South Korea.

Gyeong Eun Min, Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 05278, South Korea.

Dong-Gi Lee, Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 05278, South Korea. drpedurology@khnmc.or.kr.

References

- 1.Busby JE, Low RK. Ureteroscopic treatment of renal calculi. Urol Clin North Am. 2004;31:89–98. doi: 10.1016/S0094-0143(03)00097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson DB, Pearle MS. Complications of ureteroscopy. Urol Clin North Am. 2004;31:157–171. doi: 10.1016/S0094-0143(03)00089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mancini V, Cormio L, d'Altilia N, Benedetto G, Ferrarese P, Balzarro M, Defidio L, Carrieri G. Retrograde Intrarenal Surgery for Symptomatic Renal Sinus Cysts: Long-Term Results and Literature Review. Urol Int. 2018;101:150–155. doi: 10.1159/000488685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng C, Xiong B, Wang H, Luo J, Zhang C, Wei W, Wang Y. Retrograde intrarenal surgery vs percutaneous nephrolithotomy for treatment of renal stones >2 cm: a meta-analysis. Urol Int. 2014;93:417–424. doi: 10.1159/000363509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giusti G, Proietti S, Luciani LG, Peschechera R, Giannantoni A, Taverna G, Sortino G, Graziotti P. Is retrograde intrarenal surgery for the treatment of renal stones with diameters exceeding 2 cm still a hazard? Can J Urol. 2014;21:7207–7212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Traxer O, Thomas A. Prospective evaluation and classification of ureteral wall injuries resulting from insertion of a ureteral access sheath during retrograde intrarenal surgery. J Urol. 2013;189:580–584. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oguz U, Resorlu B, Ozyuvali E, Bozkurt OF, Senocak C, Unsal A. Categorizing intraoperative complications of retrograde intrarenal surgery. Urol Int. 2014;92:164–168. doi: 10.1159/000354623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breda A, Angerri O. Retrograde intrarenal surgery for kidney stones larger than 2.5 cm. Curr Opin Urol. 2014;24:179–183. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang J, Zhao Z, AlSmadi JK, Liang X, Zhong F, Zeng T, Wu W, Deng T, Lai Y, Liu L, Zeng G. Use of the ureteral access sheath during ureteroscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shoshany O, Margel D, Finz C, Ben-Yehuda O, Livne PM, Holand R, Lifshitz D. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy for infection stones: what is the risk for postoperative sepsis? Urolithiasis. 2015;43:237–242. doi: 10.1007/s00240-014-0747-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de la Rosette J, Denstedt J, Geavlete P, Keeley F, Matsuda T, Pearle M, Preminger G, Traxer O CROES URS Study Group. The clinical research office of the endourological society ureteroscopy global study: indications, complications, and outcomes in 11,885 patients. J Endourol. 2014;28:131–139. doi: 10.1089/end.2013.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho SY. Current status of flexible ureteroscopy in urology. Korean J Urol. 2015;56:680–688. doi: 10.4111/kju.2015.56.10.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cepeda M, Amón JH, Mainez JA, Rodríguez V, Alonso D, Martínez-Sagarra JM. Flexible ureteroscopy for renal stones. Actas Urol Esp. 2014;38:571–575. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lallas CD, Auge BK, Raj GV, Santa-Cruz R, Madden JF, Preminger GM. Laser Doppler flowmetric determination of ureteral blood flow after ureteral access sheath placement. J Endourol. 2002;16:583–590. doi: 10.1089/089277902320913288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel RM, Okhunov Z, Kaler K, Clayman RV. Aftermath of Grade 3 Ureteral Injury from Passage of a Ureteral Access Sheath: Disaster or Deliverance? J Endourol Case Rep. 2016;2:169–171. doi: 10.1089/cren.2016.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Y, Min Z, Wan SP, Nie H, Duan G. Complications of retrograde intrarenal surgery classified by the modified Clavien grading system. Urolithiasis. 2018;46:197–202. doi: 10.1007/s00240-017-0961-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]