Abstract

BACKGROUND

Gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease (GIBD) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are inflammatory diseases sharing a considerable number of similarities. However, different from CD, the operative and postoperative management of GIBD remains largely empirical because of the lack of comprehensive treatment guidelines.

AIM

To compare surgical patients with GIBD and those with CD in a medical center and identify notable clinical features and effective postoperative treatment for surgical patients with GIBD.

METHODS

We searched patients diagnosed with CD and GIBD who underwent operations for gastrointestinal complications from 2009 to 2015 at West China Hospital of Sichuan University. A total of 10 surgical patients with GIBD and 106 surgical patients with CD were recruited. Information including demographic data, medication, and operative and postoperative parameters were collected and analyzed. As the incidence of surgical GIBD is low, their detailed medical records were reviewed and compared to previous studies. Moreover, the prognoses of CD and GIBD were evaluated respectively between groups treated with biological and non-biological agents.

RESULTS

Indication for first surgery was often acute intestinal perforation for GIBD patients (7/10 vs 0/106, P < 0.001), whereas intestinal fistulae (0/10 vs 44/106, P = 0.013) and ileus (0/10 vs 40/106, P = 0.015) were the indications for surgical CD patients. Approximately 40% of patients with GIBD and 23.6% of patients with CD developed postoperative complications, 50% of patients with GIBD and 38.7% of patients with CD had recurrence postoperatively, and 40% (4/10) of patients with GIBD and 26.4% (28/106) of patients with CD underwent reoperations. The average period of postoperative recurrence was 7.87 mo in patients with Behçet's disease (BD) and 10.43 mo in patients with CD, whereas the mean duration from first surgery to reoperation was 5.75 mo in BD patients and 18.04 mo in CD patients. Surgical patients with GIBD more often used corticosteroids (6/10 vs 7/106, P < 0.001) and thalidomide (7/10 vs 9/106, P < 0.001) postoperatively, whereas surgical patients with CD often used infliximab (27/106), azathioprine, or 6-mercaptopurine (74/106) for maintenance therapy.

CONCLUSION

Patients suffering GIBD require surgery mostly under emergency situations, which may be more susceptible to recurrence and reoperation and need more aggressive postoperative treatment than patients with CD.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease, Crohn’s disease, Surgery, Postoperative treatment, Biological agents, Real-world study

Core Tip: This real-world study was designed to identify effective postoperative treatment for patients with gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease (GIBD) from the experience of Crohn’s disease (CD). Indication for first surgery was often acute gastrointestinal complications for GIBD patients, compared with patients with CD frequently undergoing purposed elective surgeries. Although no statistically significant difference was observed, patients with GIBD suffered more and earlier recurrences and reoperations than patients with CD. Awareness should be raised about the emergency condition of GIBD because it is more likely to be discounted than CD in clinics. Furthermore, they may require more aggressive treatment for more severe disease process postoperatively, like biological agents.

INTRODUCTION

Behçet disease (BD) is a rare, relapsing, and chronic multisystem vasculitis disease, with typical oral and genital ulcerations and ocular inflammation[1,2]. Gastrointestinal involvement in BD (GIBD) is observed in only 5%-50% of BD cases[3,4].

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a representative inflammatory bowel disease involving the entire gastrointestinal tract, especially the ileocecal area[5]. However, different from the vasculitis of intestinal BD, CD is characterized by non-caseating granulomas and discontinuous transmural lesions with inflammation penetrating to the muscularis propria, resulting in stricturing and fistulization[6]. However, they are similar inflammatory diseases sharing a considerable number of genetic backgrounds, pathogenesis, clinical features, and treatment protocols[7,8]. Both activate innate and adaptive immune systems, increasing Th1, Th17, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells and γδ+ T cell activities[9-13]. Intestinal BD and CD are regarded as two sides of the same coin rather than two distinct disease entities[14].

Although pharmacotherapy is the preferred option for BD in the absence of complications, surgery is needed in uncontrolled or emergency situations, such as perforations, massive bleeding, and obstruction[15]. Choi et al[16] reported that 36% and 43% of patients with GIBD received an operation at 2 and 5 years compared with at least half of patients with CD who underwent one or more surgical procedures in their lifetimes. However, the surgical treatment of GIBD is still empirical sometimes because of the lack of randomized control trials[17], and reports on the surgical treatment and outcomes of GIBD are few. Guidelines on surgical treatment in CD has been suggested by the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO). Can we guide the surgical treatment of BD from the experience of CD? Do they share common surgical characteristics? We compared our surgical GIBD patients to surgical CD patients from different aspects with the aim of determining optimal postoperative management of GIBD. To our knowledge, this is the first article comparing clinical characteristics, postoperative pharmacotherapy, and outcomes between surgical GIBD cases and CD cases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

We searched for patients at West China Hospital of Sichuan University diagnosed with GIBD and CD undergoing operation from 2009-2015, collecting relative data and performing statistical analysis (GIBD group, n = 10; CD group, n = 106). Patients undergoing surgery for gastrointestinal disease and meeting the diagnostic criteria of the International Criteria for BD[18] and ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in CD[19] were included. Patients without complete medical records or continuous follow-up for more than 5 years and with other gastrointestinal diseases or critical illnesses were excluded.

Data collection

We investigated demographic data, including gastrointestinal or extraintestinal manifestations and signs, of these two groups. We collected surgery parameters, including the duration from initial diagnosis to first surgery, indication for first surgery and first operation type, and postoperative parameters about number of ostomy closures, recurrences, reoperations, and postoperative complications and mortality. Furthermore, use of drugs before and after surgery was determined. Finally, we compared our results with those of previous studies, which mainly included articles about treatment and relative prognosis of patients suffering from GIBD and undergoing operations. The key words were as follows: “(gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease,” “intestinal Behçet’s disease,” or “entero-Behçet’s disease”) and “surgery.”

Statistical analysis

Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 19.0) software and Graph Pad Prism V.6.0 (San Diego, CA, United States) were used for analyses and graphics. Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± SD and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. The χ2 test and Fisher exact test were used to compare categorical variables, and the t-test was used for continuous variables. Recurrence-free rate and reoperation-free rate were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Differences with a P value < 0.05 were considered significant for all tests. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Chen YL from West China Biomedical Big Data Center. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

RESULTS

Study information and patient characteristics

A total of 10 surgical patients with GIBD and 106 surgical patients with CD were recruited. The characteristics of the two groups are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of surgical patients with GIBD (41.90 ± 11.15) was higher than that of surgical patients with CD (32.38 ± 9.46, P = 0.003). The surgical patients with GIBD had more cases of oral aphtha (P < 0.001), genital ulcer (P < 0.001), skin lesions (P < 0.001), and fevers (P = 0.025) than the surgical patients with CD but fewer cases of diarrhea (P < 0.001). Only one surgical patient with GIBD had ocular lesion. Both groups had more cases of ulcer in the ileum and colon (4/10 vs 66/106) than in the other sites of the digestive tract.

Table 1.

Clinical features of surgical patients with gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease and Crohn’s disease

|

|

GIBD (n = 10)

|

CD (n = 106)

|

P

value

|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 41.90 ± 11.15 | 32.38 ± 9.46 | 0.003 |

| Male, n (%) | 6 (60) | 74 (69.8) | 0.498 |

| Family history (n) | 0 | 0 | —— |

| Symptoms and signs, n (%) | |||

| Oral aphthae | 8 (80) | 8 (7.5) | < 0.001 |

| Ocular lesion | 1 (10) | 0 | 0.086 |

| Genital ulcer | 5 (50) | 3 (2.8) | < 0.001 |

| Skin lesion | 5 (50) | 2 (1.9) | < 0.001 |

| Arthritis/arthralgia | 4 (40) | 16 (15.1) | 0.068 |

| Abdominal pain | 10(100) | 101 (95.3) | 1.000 |

| Diarrhea | 2 (20) | 67 (63.2) | < 0.014 |

| GI bleeding | 6 (60) | 37 (34.9) | 0.170 |

| Abdominal mass | 3 (30) | 39 (36.8) | 0.746 |

| Fever | 6 (60) | 26 (24.5) | 0.026 |

| Weight loss | 6 (60) | 74 (69.8) | 0.498 |

| Location of ulcer, n (%) | |||

| Upper GI | 0 | 2 (1.8) | 1.000 |

| Ileum/jejunum | 1 (10) | 16 (15.1) | 1.000 |

| Ileum and ileocecal | 2 (20) | 3 (2.8) | 0.058 |

| Ileum and colon | 4 (40) | 66 (62.3) | 0.191 |

| Colon | 3 (30) | 19 (17.9) | 0.377 |

| Shape of ulcer, n (%) | |||

| Oval | 4 (40) | 0 | < 0.001 |

| Longitudinal | 0 | 38 (35.8) | 0.029 |

| Other | 6 (60) | 68 (64.2) | 1.000 |

CD: Crohn’s disease; GIBD: Gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease; GI: Gastrointestinal; SD: Standard deviation.

Surgical and postoperative therapy of patients with GIBD and CD

As indicated by the surgery and postoperative parameters in Table 2, 7/10 surgical patients with GIBD achieved a confirmed diagnosis after first surgery. Indications for first surgery were acute intestinal perforation (P < 0.001) or diagnostic surgery for acute abdomen (P < 0.001) in surgical GIBD patients, whereas intestinal fistulae (P = 0.013) and ileus (P = 0.015) were more in surgical patients with CD. The ulcers of GIBD tended to perforate at multiple sites more easily than those of CD. One of our GIBD cases showed perforations at four sites in the small intestine and transverse colon. No patient with GIBD underwent operation for perianal lesions, intestinal fistulae, ileus, or abdominal abscess, which were common in patients with CD. Moreover, segmental resection and ostomy (7/10 vs 48/106, P = 0.188) were the preferred first surgery options by both groups, especially under emergency situations. Approximately 71.4% (5/7) of patients with GIBD and 60.4% (29/48) of patients with CD underwent ostomy closure. The average period from ostomy to ostomy closure was 18.60 mo in patients with GIBD and 13.86 mo in patients with CD (P = 0.358).

Table 2.

Surgery and postoperative parameters of patients with gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease and Crohn’s disease

|

|

GIBD (n = 10)

|

CD (n = 106)

|

P

value

|

| Diagnosed after first surgery, n (%) | 7 (70.0) | 56 (52.8) | 0.341 |

| Duration from initial diagnosis to first surgery (mo, mean ± SD) | 27.67 ± 23.03(n = 3)1 | 41.60 ± 39.22(n = 50)2 | 0.548 |

| Indications for first surgery, n (%) | |||

| Perianal abscess or fistula | 0 | 10 (9.4) | 0.597 |

| Intestinal fistulae | 0 | 44 (41.5) | 0.013 |

| Ileus | 0 | 40 (37.7) | 0.015 |

| Abdominal abscess | 0 | 12 (11.3) | 0.596 |

| Acute intestinal perforation | 7 (70) | 0 | < 0.001 |

| Diagnostic surgery for acute abdomen | 3 (30) | 0 | < 0.001 |

| First operation type, n (%) | |||

| Segmental resection and ostomy | 7 (70) | 48 (45.3) | 0.188 |

| Perforation repairmen + drainage | 1 (10) | 0 | 0.086 |

| Segmental resection | 2 (20) | 37 (34.9) | 1.000 |

| Drainage | 0 | 21 (19.8) | 0.204 |

| Others | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 1.000 |

| Ostomy closure, n (%) | 5 (71.4)3 | 29 (60.4)4 | 0.696 |

| Ostomy to ostomy closure (mo, mean ± SD) | 18.60 ± 10.14 | 13.86 ± 10.58 | 0.359 |

| Recurrence, n (%) | 5 (50) | 41 (38.7) | 0.515 |

| Recurrence from first surgery (mo, mean ± SD) | 7.87 ± 7.37 | 10.43 ± 8.97 | 0.543 |

| Recurrence location, n (%) | |||

| Anastomosis | 5 (100) | 32 (78.8) | 0.566 |

| Others | 2 (40) | 26 (63.4) | 0.365 |

| Reoperations, n (%) | 4 (40) | 28 (26.4) | 0.460 |

| Duration from first surgery to reoperation (mo, mean ± SD) | 5.75 ± 4.99 | 18.04 ± 16.30 | 0.150 |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | 4 (40) | 25 (23.6) | 0.265 |

| GI bleeding | 1 (10) | 5 (4.7) | 0.425 |

| Anastomotic fistula | 2 (20) | 23 (21.7) | 1.000 |

| Intraabdominal infection | 4 (40) | 12 (11.3) | 0.031 |

| Others | 1 (10) | 4 (3.8) | 0.368 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 1 (10) | 2 (1.9) | 0.239 |

Patients with gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease (GIBD) required surgery always for acute and emergency complications, while elective surgeries were more common in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD). The average period of postoperative recurrence was 7.87 mo with a range of 0.3 to 18 mo in GIBD patients and 10.43 mo with a range of 2 to 36 mo in CD patients.

Three (30.0) patients with GIBD were diagnosed before first surgery.

Fifty (47.2) patients with CD were diagnosed before first surgery.

Seven (70.0) patients with GIBD underwent surgery including the operation type of ostomy.

Forty-eight (45.3) patients with CD underwent surgery including the operation type of ostomy. CD: Crohn’s disease; GIBD: Gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease; SD: Standard deviation.

Postoperative recurrence was observed in 5 (50%) of 10 cases in patients with GIBD and in 41 of 106 cases (38.7%) in patients with CD. Recurrences from the anastomosis area were frequent in patients with GIBD and CD (5/5 vs 32/41, respectively). The average period of postoperative recurrence was 7.87 mo with a range of 0.3 to 18 mo in patients with GIBD and 10.43 mo with a range of 2 to 36 mo in CD patients. Four of the five patients with GIBD, who had recurrence, underwent reoperations. The causes of reoperations were bowel perforation in one (10%) case, gastrointestinal bleeding in one (10%), and anastomotic fistula in two (20%). The mean duration from first surgery to reoperation was 5.75 mo in patients with GIBD and 18.04 mo in patients with CD. Although no significant difference in the average period of recurrence and reoperation was observed between the two groups, one patient with GIBD had recurrence of distal perforation from stoma 11 d after segmental resection and ostomy. The patients with GIBD appeared to have recurrence and underwent reoperation earlier than the patients with CD. The incidence of postoperative complications was 40% (4/10) in patients with GIBD and 23.6% (25/106) in patients with CD (P = 0.265). The postoperative complications of patients with GIBD included intraabdominal infection in one case, anastomotic fistula combined with intraabdominal infection in two, and GI bleeding combined with intraabdominal infection in one.

The two groups were compared with regard to the use of drugs before and after surgery (Table 3). We found no significant difference in preoperative medication. Notably, surgical patients with GIBD more often used corticosteroids (6/10 vs 7/106, P < 0.001) and thalidomide (7/10 vs 9/106, P < 0.001) after surgery, whereas surgical patients with CD often used infliximab (27/106), azathioprine (AZA), or 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP; 74/106) for postoperative maintenance therapy. In our cases, two surgical patients suffering from GIBD and using adalimumab postoperatively under the background of intestinal perforation and timely enterostomy showed a preferable prognosis with successful ostomy closure and endoscopic remission and without recurrence or reoperation during our 5-year follow-up.

Table 3.

Use of drugs before and after surgery in patients with gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease and Crohn’s disease

|

GIBD (n = 10)

|

CD (n = 106)

|

P

value

|

|||||

|

|

Before surgery (n = 3)1

|

After surgery (n = 10)

|

Before surgery (n = 50)2

|

After surgery (n = 106)

|

P

1

value

|

P

2

value

|

|

| 5-ASA or sulfasalazine | 1(33.3) | 1 (10) | 31 (62) | 12 (11.3) | 0.555 | 1.000 | |

| AZA or 6-MP | 1(33.3) | 6 (60) | 20 (40) | 74 (69.8) | 1.000 | 0.498 | |

| Corticosteroids | 0 | 6 (60) | 7 (14) | 7 (6.6) | 1.000 | < 0.001 | |

| Biological agent | 0 | 2 (20) | 9 (18) | 27 (25.5) | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Infliximab | 0 | 0 | 9 (18) | 27 (25.5) | 1.000 | 0.114 | |

| Adalimumab | 0 | 2 (20) | 0 | 0 | - | 0.007 | |

| Thalidomide | 1(33.3) | 7 (70) | 2 (4) | 9 (8.5) | 0.163 | < 0.001 | |

| MTX | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 2 (1.9) | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Others | 0 | 1 (10) | 1 (2) | 2 (1.9) | 1.000 | 0.239 | |

Three (30.0) surgical patients with gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease were diagnosed before first surgery.

Fifty (45.0) surgical patients with Crohn’s disease were diagnosed before first surgery. CD: Crohn’s disease; GIBD: Gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease; 5-ASA: 5-aminosallcylic acid; 6-MP: 6-mercaptopurine; AZA: Azathioprine; MTX: Methotrexate.

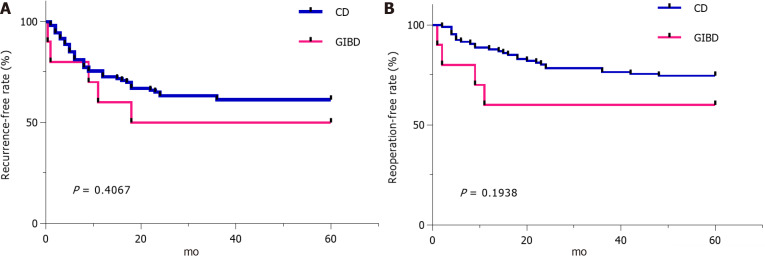

As the mortality (1/10 vs 2/106, P = 0.239), recurrence-free rate (5/10 vs 65/106, P = 0.4067), and reoperation-free rate (6/10 vs/ 83/106, P = 0.1938) in 5 years showed no significant difference in both groups (Table 2, Figure 1), we observed that one patient with GIBD and segmental resection and ostomy for emergency intestinal perforation used AZA, corticosteroids, and thalidomide successively as maintenance drugs for postoperative medical therapy and died of repeated uncontrolled perforation of the digestive tract. Two patients with CD died of severe intra-abdominal infection. In the patients with GIBD, the group treated with biological agents had no recurrence (0/2), reoperation (0/2), or mortality (0/2), and the recurrence rate, reoperation rate, and mortality were 62.5% (5/8), 50% (4/8), and 12.5% (1/8) in the group treated with nonbiological agents (P > 0.05). In the patients with CD, the recurrence rate, reoperation rate, and mortality were 21.4% (7/27), 3.6% (2/27), and no mortality (0/27) in the group treated with biological agents, and 48.2% (34/79; P = 0.115), 34.9% (26/79; P = 0.011), and 8.4% (2/79; P = 1.000) in the group treated with nonbiological agents, respectively.

Figure 1.

Recurrence-free rate and reoperation-free rate in surgical gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease group and surgical Crohn’s disease group. Recurrence-free rate and reoperation-free rate after first surgery are higher in surgical patients with Crohn’s disease than patients with gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease, whereas there is no significant difference in both groups. A: Recurrence-free rate; B: Reoperation-free rate. CD: Crohn’s disease; GIBD: Gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease.

DISCUSSION

The clinical characteristics and surgical parameters of 10 surgical patients with GIBD and 106 surgical patients with CD were compared in this study. Surgical patients with GIBD are likely to have more cases of oral aphthae, genital ulcer, skin lesion, and vascular lesion than those with CD in our data, which have been proved as relatively specific clinical manifestations of BD previously[20-22].

The surgical parameters of the two groups were similar in some characteristics but had differential points. Timely surgical treatment in GIBD is essential under uncontrolled or emergency conditions (e.g., intestinal perforation, huge GI bleeding, or other acute abdominal diseases)[2,20,21]. Our study showed GIBD cases always requiring surgery for emergency conditions. However, an elective surgery, which optimized the nutritional and immunosuppression status of these patients before operation, was more common in patients with CD. The indications for first surgery were acute intestinal perforation (P < 0.001) or diagnostic surgery for acute abdomen (P < 0.001) in patients with GIBD and intestinal fistulae (P = 0.013) and ileus (P = 0.015) with long course in surgical patients with CD.

Segmental resection and ostomy (7/10 vs 48/106, P = 0.188) were the preferred first surgery options for both groups. A temporary stoma was recommended in CD patients with emergency conditions, such as intestinal perforation, or in patients with prolonged (> 6 wk) and high-dose (≥ 20 mg of prednisolone equivalent) steroid use, which are associated with postoperative complications, such as anastomotic leakage. In the ECCO Guidelines of 2020, defunctioning ileostomy together with intensified medical therapy for refractory CD colitis to divert the fecal stream, may ameliorate disease progression[23]. Similarly, clinicians had reached a consensus that creating a stoma is more preferable than primary anastomosis for surgical patients with GIBD at an active stage, especially under emergency conditions[21,22,24]. Baek et al[24] finished a retrospective review including 91 surgical patients with GIBD to determine whether these patients were under a high risk of recurrence and needed stoma frequently. However, approximately 90% the patients with CD reached obvious remission in the distal intestinal segment after defunctioning stoma. This condition was not observed in the patients with GIBD. A patient with GIBD in our study presented with repeated perforation in the distal intestinal segment of the stoma. This result indicated that patients with GIBD may need to start intensive treatment earlier after surgery, even if the patients already underwent defunctioning stoma.

In our study, postoperative recurrence was observed in 50% of patients with GIBD and 38.7% of patients with CD. The average period of postoperative recurrence was 7.87 mo in patients with BD and 10.43 mo in patients with CD. The mean duration from first surgery to reoperation was 5.75 mo in patients with BD and 18.04 mo in patients with CD. Although no statistically significant difference was observed, surgical patients with GIBD were associated with a higher ratio of postoperative recurrence than surgical patients with CD, similar to a previous study[24]. Patients who were suffering from GIBD and had postoperative recurrence and reoperation earlier than CD patients may require more aggressive postoperative treatments. Patients with GIBD were associated with a high rate of postoperative recurrence and reoperation, especially those with early onset or high level of C-reactive protein initially. Furthermore, patients with GIBD characterized with deep ulcers, especially volcano-shaped ulcers, were associated with relatively early postoperative recurrence[2]. A follow-up of every 6-12 mo including radiography and endoscopy for surgical patients with CD was also recommended for surgical patients with BD.

The surgical patients with GIBD in our study frequently used corticosteroids or MTX after operation, whereas surgical patients with CD used infliximab or AZA postoperatively for maintenance therapy. Similar to CD, T helper type 1-associated cytokines, such as TNF-α, is associated with BD[25]. Two patients using adalimumab postoperatively in our study showed a preferable prognosis with endoscopic remission and without recurrence, as indicated in a previous study, which reported that anti-TNF-α is useful in maintaining remission of intestinal BD[2,26]. By contrast, one patient with GIBD who used AZA, corticosteroids, and thalidomide for postoperative medical therapy died of repeated uncontrolled gastrointestinal perforation. Biological agents may control inflammation at an ideal state, such as the remission state of “mucosa healing” for CD, which leads to a preferable prognosis. Clinicians tested biological agents on patients with GIBD. Sfikakis et al[27] proposed that IFX may be used in patients who failed treatment using immunosuppressants or used corticosteroid at dosage exceeding 7.5 mg/d. Lee et al[28] performed a multicenter retrospective noncontrolled review including 28 patients in South Korea; they found that infliximab is an effective therapy for patients with intestinal BD. Japanese Consensus Statements in 2020 stated that medication with TNF-α inhibitors is recommended for patients who are not responsive to traditional medical treatment. Patients with severe symptoms and deep ulcers can receive 0.5-1 mg/kg prednisolone for 1-2 wk and undergo slow tapering. Biological agents, such as adalimumab and infliximab, can be considered in such cases[2,29]. Biological agents may be used for high-risk patients with GIBD during severe or emergency situations, similar to the therapy protocol of CD called “top-down therapy” with early initiation of biological agents[30], not only stepping up to it after failing to respond to conventional treatment. Sex (male), ileal involvement, accompanying with ocular lesions are associated with a high risk of undergoing surgery[31,32], and such patients may benefit more from the early use of biological agents[2]. However, biological agents are not effective for all GIBD patients. Naganuma et al[26] reported that patients suffering from GIBD with involvement of the ileum may tend to be more inefficient to infliximab and require operation than those with involvement of the cecum.

There are some limitations to this study. This study is a retrospective one. Although the incidence of surgical GIBD is low, we compared accurate and complete information of our surgical patients with GIBD with those of surgical patients with CD, providing valuable perspectives on the treatment of surgical GIBD. However, a randomized controlled trial is still needed.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, awareness should be raised about the emergency condition of GIBD because it is more likely to be discounted than CD in clinics. Although no statistically significant difference was observed, patients with GIBD having a numerically higher incidence of recurrence and reoperation, which also tended to occur earlier than those patients with CD, may require more aggressive postoperative treatment. Biological agents may be ideal postoperative maintenance treatments for some surgical patients with GIBD after risk assessment.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

The preoperative and postoperative management of gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet's disease (GIBD) remains empirical sometimes. We may guide the surgical treatment of GIBD from the experience of Crohn’s disease (CD).

Research motivation

Treatment strategies and randomized control trials for surgical patients with GIBD are lacking.

Research objectives

To identify notable clinical features and effective postoperative treatment for patients with GIBD from the experience of CD.

Research methods

Patients diagnosed with CD and GIBD who underwent operations for gastrointestinal complications were recruited. Information including demographic data, medication, and operative and postoperative parameters were collected and analyzed.

Research results

Indication for first surgery was often acute gastrointestinal complications for GIBD patients, compared with patients with CD frequently undergoing purposed elective surgeries. Although no statistically significant difference was observed, patients with GIBD suffered more and earlier recurrences and reoperations than patients with CD.

Research conclusions

Although no statistically significant difference was observed, patients with GIBD having a numerically higher incidence of recurrence and reoperation, which also tended to occur earlier than those patients with CD, may require more aggressive postoperative treatment.

Research perspectives

As patients with GIBD may require more aggressive postoperative treatment, biological agents may be ideal postoperative maintenance treatments for them. A randomized controlled trial is still needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Department of Medical Records of West China Hospital, Sichuan University for providing these data.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: Ethical approval was obtained from the Biomedical Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University.

Informed consent statement: The patients provide signed informed consent to the study.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: November 30, 2020

First decision: February 23, 2021

Article in press: April 6, 2021

Specialty type: Medicine, general and internal

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Farid K S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang LL

Contributor Information

Li Zeng, Department of Gastroenterology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China.

Wen-Jian Meng, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China.

Zhong-Hui Wen, Department of Gastroenterology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China.

Yi-Long Chen, West China Biomedical Big Data Center, West China Hospital/West China School of Medicine, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China.

Yu-Fang Wang, Department of Gastroenterology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China. wangyufang04@126.com.

Cheng-Wei Tang, Department of Gastroenterology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Behçet's syndrome. JAMA. 1973;224:756–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanabe K, Tanida S, Inoue N, Kunisaki R, Kobayashi K, Nagahori M, Arai K, Uchino M, Koganei K, Kobayashi T, Takeno M, Ueno F, Matsumoto T, Mizuki N, Suzuki Y, Hisamatsu T. Evidence-based diagnosis and clinical practice guidelines for intestinal Behçet's disease 2020 edited by Intractable Diseases, the Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:679–700. doi: 10.1007/s00535-020-01690-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheon JH, Kim ES, Shin SJ, Kim TI, Lee KM, Kim SW, Kim JS, Kim YS, Choi CH, Ye BD, Yang SK, Choi EH, Kim WH. Development and validation of novel diagnostic criteria for intestinal Behçet's disease in Korean patients with ileocolonic ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2492–2499. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ye JF, Guan JL. Differentiation between intestinal Behçet’s disease and Crohn’sdisease based on endoscopy. Turk J Med Sci. 2019;49:42–49. doi: 10.3906/sag-1807-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369:1641–1657. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60751-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:417–429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grigg EL, Kane S, Katz S. Mimicry and deception in inflammatory bowel disease and intestinal behçet disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2012;8:103–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim DH, Cheon JH. Intestinal Behçet's Disease: A True Inflammatory Bowel Disease or Merely an Intestinal Complication of Systemic Vasculitis? Yonsei Med J. 2016;57:22–32. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Direskeneli H. Behçet's disease: infectious aetiology, new autoantigens, and HLA-B51. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:996–1002. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.11.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Direskeneli H, Eksioglu-Demiralp E, Kibaroglu A, Yavuz S, Ergun T, Akoglu T. Oligoclonal T cell expansions in patients with Behçet's disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;117:166–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00931.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki Y, Hoshi K, Matsuda T, Mizushima Y. Increased peripheral blood gamma delta+ T cells and natural killer cells in Behçet's disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:588–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freysdottir J, Lau S, Fortune F. Gammadelta T cells in Behçet's disease (BD) and recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;118:451–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Na SY, Park MJ, Park S, Lee ES. Up-regulation of Th17 and related cytokines in Behçet's disease corresponding to disease activity. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31:32–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valenti S, Gallizzi R, De Vivo D, Romano C. Intestinal Behçet and Crohn's disease: two sides of the same coin. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2017;15:33. doi: 10.1186/s12969-017-0162-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatemi I, Esatoglu SN, Hatemi G, Erzin Y, Yazici H, Celik AF. Characteristics, Treatment, and Long-Term Outcome of Gastrointestinal Involvement in Behcet's Syndrome: A Strobe-Compliant Observational Study From a Dedicated Multidisciplinary Center. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3348. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi IJ, Kim JS, Cha SD, Jung HC, Park JG, Song IS, Kim CY. Long-term clinical course and prognostic factors in intestinal Behçet's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:692–700. doi: 10.1007/BF02235590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopalco G, Rigante D, Venerito V, Fabiani C, Franceschini R, Barone M, Lapadula G, Galeazzi M, Frediani B, Iannone F, Cantarini L. Update on the Medical Management of Gastrointestinal Behçet's Disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:1460491. doi: 10.1155/2017/1460491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Team for the Revision of the International Criteria for Behçet's Disease (ITR-ICBD) The International Criteria for Behçet's Disease (ICBD): a collaborative study of 27 countries on the sensitivity and specificity of the new criteria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:338–347. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, Kucharzik T, Fiorino G, Annese V, Calabrese E, Baumgart DC, Bettenworth D, Borralho Nunes P, Burisch J, Castiglione F, Eliakim R, Ellul P, González-Lama Y, Gordon H, Halligan S, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Kotze PG, Krustinš E, Laghi A, Limdi JK, Rieder F, Rimola J, Taylor SA, Tolan D, van Rheenen P, Verstockt B, Stoker J European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO] and the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology [ESGAR] ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:144–164. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hatemi I, Hatemi G, Çelik AF. Gastrointestinal Involvement in Behçet Disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2018;44:45–64. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bayraktar Y, Ozaslan E, Van Thiel DH. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Behcet's disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:144–154. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200003000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moon CM, Cheon JH, Shin JK, Jeon SM, Bok HJ, Lee JH, Park JJ, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim NK, Kim WH. Prediction of free bowel perforation in patients with intestinal Behçet's disease using clinical and colonoscopic findings. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2904–2911. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adamina M, Bonovas S, Raine T, Spinelli A, Warusavitarne J, Armuzzi A, Bachmann O, Bager P, Biancone L, Bokemeyer B, Bossuyt P, Burisch J, Collins P, Doherty G, El-Hussuna A, Ellul P, Fiorino G, Frei-Lanter C, Furfaro F, Gingert C, Gionchetti P, Gisbert JP, Gomollon F, González Lorenzo M, Gordon H, Hlavaty T, Juillerat P, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Krustins E, Kucharzik T, Lytras T, Maaser C, Magro F, Marshall JK, Myrelid P, Pellino G, Rosa I, Sabino J, Savarino E, Stassen L, Torres J, Uzzan M, Vavricka S, Verstockt B, Zmora O. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn's Disease: Surgical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:155–168. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baek SJ, Kim CW, Cho MS, Jang HA, Baik SH, Hur H, Min BS, Kim NK. Surgical Treatment and Outcomes in Patients With Intestinal Behçet Disease: Long-term Experience of a Single Large-Volume Center. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:575–581. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gül A. Behçet's disease: an update on the pathogenesis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19:S6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naganuma M, Sakuraba A, Hisamatsu T, Ochiai H, Hasegawa H, Ogata H, Iwao Y, Hibi T. Efficacy of infliximab for induction and maintenance of remission in intestinal Behçet's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1259–1264. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sfikakis PP, Markomichelakis N, Alpsoy E, Assaad-Khalil S, Bodaghi B, Gul A, Ohno S, Pipitone N, Schirmer M, Stanford M, Wechsler B, Zouboulis C, Kaklamanis P, Yazici H. Anti-TNF therapy in the management of Behcet's disease--review and basis for recommendations. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:736–741. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JH, Cheon JH, Jeon SW, Ye BD, Yang SK, Kim YH, Lee KM, Im JP, Kim JS, Lee CK, Kim HJ, Kim EY, Kim KO, Jang BI, Kim WH. Efficacy of infliximab in intestinal Behçet's disease: a Korean multicenter retrospective study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1833–1838. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31828f19c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hisamatsu T, Ueno F, Matsumoto T, Kobayashi K, Koganei K, Kunisaki R, Hirai F, Nagahori M, Matsushita M, Kishimoto M, Takeno M, Tanaka M, Inoue N, Hibi T. The 2nd edition of consensus statements for the diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet's disease: indication of anti-TNFα monoclonal antibodies. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:156–162. doi: 10.1007/s00535-013-0872-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oldenburg B, Hommes D. Biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: top-down or bottom-up? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:395–399. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32815b601b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naganuma M, Iwao Y, Inoue N, Hisamatsu T, Imaeda H, Ishii H, Kanai T, Watanabe M, Hibi T. Analysis of clinical course and long-term prognosis of surgical and nonsurgical patients with intestinal Behçet's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2848–2851. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasahara Y, Tanaka S, Nishino M, Umemura H, Shiraha S, Kuyama T. Intestinal involvement in Behçet's disease: review of 136 surgical cases in the Japanese literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:103–106. doi: 10.1007/BF02604297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.