Abstract

BACKGROUND

Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC) is a rare low-grade malignant salivary gland tumor. The morphological and immunohistochemical features of MASC closely resemble those of breast secretory carcinoma. The key characteristics of the lesion are a lack of pain and slow growth. There is no obvious specificity in the clinical manifestations and imaging features. The diagnosis of the disease mainly depends on the detection of the MASC-specific ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene.

CASE SUMMARY

This report describes a rare case of a 32-year-old male patient who presented with a gradually growing lesion that was initially diagnosed as breast-like secretory carcinoma of the right parotid gland. Imaging and histological investigations were used to overcome the diagnostic difficulties. The lesion was managed with right parotidectomy, facial nerve preservation, biological patch implantation to restore the resulting defect, and postoperative radiotherapy. On postoperative follow-up, the patient reported a mild facial deformity with no complications, signs of facial paralysis, or Frey’s syndrome.

CONCLUSION

The imaging and histological diagnostic challenges for MASC are discussed.

Keywords: Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma, Salivary gland, Immunohistochemistry, Total lobectomy of right parotid gland, Case report

Core Tip: Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma is a rare low-grade malignant salivary gland tumor. The morphological and immunohistochemical features of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma closely resemble those of breast secretory carcinoma. The key characteristics of the lesion are a lack of pain and slow growth. There is no obvious specificity in the clinical manifestations and imaging features. The diagnosis of this disease is particularly difficult. This report describes a rare case of a 32-year-old male patient who presented with a gradually growing lesion that was initially diagnosed as breast-like secretory carcinoma of the right parotid gland. Imaging and histological investigations were used to overcome the diagnostic difficulties.

INTRODUCTION

Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC) is a rare malignant tumor of the salivary glands that mainly occurs in the parotid gland, followed by the submandibular gland, minor salivary gland, and accessory parotid gland[1,2]. The clinical manifestations of MASC are a lack of pain and a slowly growing solid mass. The clinical features and imaging specificities are relatively weak; therefore, the tumor may be misdiagnosed[3,4]. Skálová et al[5] investigated various salivary gland tumors and reported that although MASC has similarities to acinar cell carcinoma (AciCC), the two are separate entities with dissimilar histological characteristics. In addition, the diagnosis of the disease depends on the detection of the MASC-specific ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene[6]. Currently, the pathogenesis of MASC is unclear. Chiose et al[7] reported discontinuous p63-positive cells, which are non-neoplastic basal cells, around the tumor cells and cysts, suggesting that MASC may originate from the ductal epithelium. On the other hand, Connor et al[8] reported an occasional local involvement of medium-sized ducts in some tumors, indicating that MASC is more likely to originate from striated ducts. Mariano et al[9] believed that MASC is a lipid-rich tumor containing large lipid droplets encapsulated by adipophilin or adipocyte differentiation-related protein, suggesting that MASC may have lactation-like characteristics. In this article, we report a rare case of a 32-year-old male patient who presented with a gradually growing lesion that was initially diagnosed as breast-like secretory carcinoma of the right parotid gland. Imaging and histological investigations were used to overcome the diagnostic difficulties. The lesion was managed with right parotidectomy, facial nerve preservation, restoration of the defect, and postoperative radiotherapy.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

Two-year history of a painless mass under his right ear.

History of present illness

The 32-year-old male patient visited the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Hospital of Stomatology, Jilin University, China with a 2-year history of a painless mass under his right ear. The lesion had gradually increased in size. The patient reported no pain, facial paralysis, or posture-related issues.

History of past illness

The patient had no history of hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, smoking, or drinking. He denied a history of surgery.

Personal and family history

The patient denied a relevant family history.

Physical examination

The clinical examination revealed a mobile and palpable mass (2.0 cm × 1.5 cm) in the right subauricular area with the superior and inferior boundaries extending 1.5 cm under the zygomatic arch and 2 cm above the superior margin of the mandibular angle, respectively.

Laboratory examinations

Laboratory examination showed no obvious abnormality.

Imaging examinations

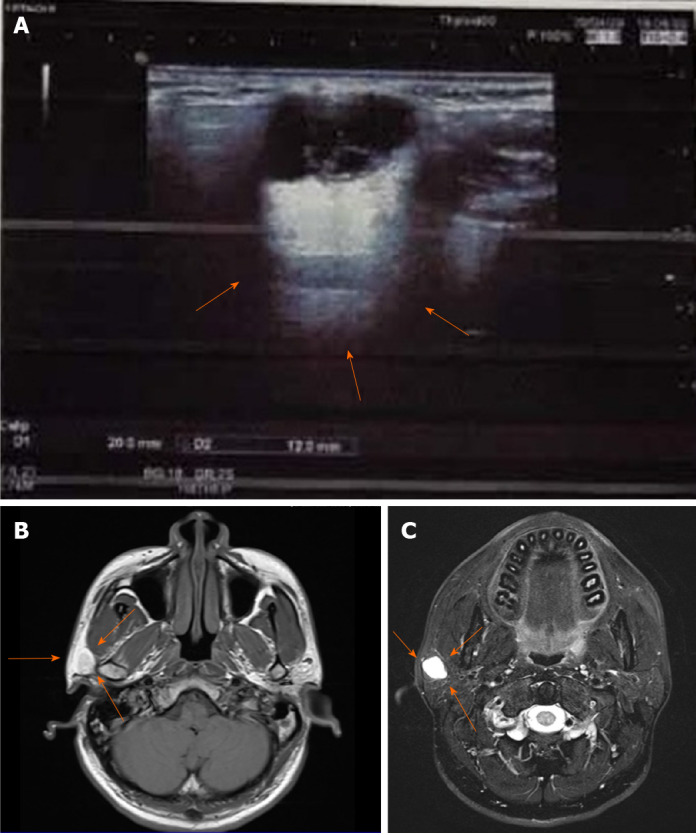

Ultrasonography revealed the right parotid gland had a physiological shape and size (2.0 cm × 4.0 cm × 1.5 cm), and a heterogeneous mixed-echo light mass approximately 2.0 cm × 1.2 cm was observed in the lower pole. The boundary was clear, showing strong echoes with strips and dots (Figure 1A).

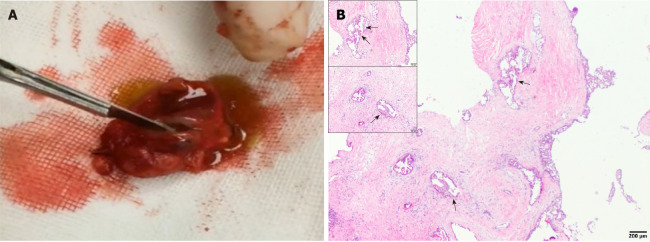

Figure 1.

Radiological results for the lesion. A: Ultrasonic examination showing a clear boundary with strong echoes of strips and dots (arrows); B: Magnetic resonance imaging results for the lesion showing iso-low signals for T1; C: High signals for the T2 fat compression.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a circular abnormal signal for the right parotid gland, with an iso-low signal for T1-weighted image. In addition, T2 fat compression, diffusion-weighted imaging, and apparent diffusion coefficient images resulted in high signals. The edge of the focus was smooth, and the largest slice was 1.34 cm. The initial MRI results suggested a cystic or benign tumor of the parotid gland (Figures 1B and C).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The patient was diagnosed with MASC of the right parotid gland.

TREATMENT

The tumor section was solid and brownish red in color with an obvious cystic component and yellowish green fluid (Video 1). The capsule was incomplete, with an unclear boundary. There was no obvious adhesion to the surrounding tissues, and the tumor was clearly separate from the facial nerve branches. Histopathological analysis confirmed the cystic nature of the lesion.

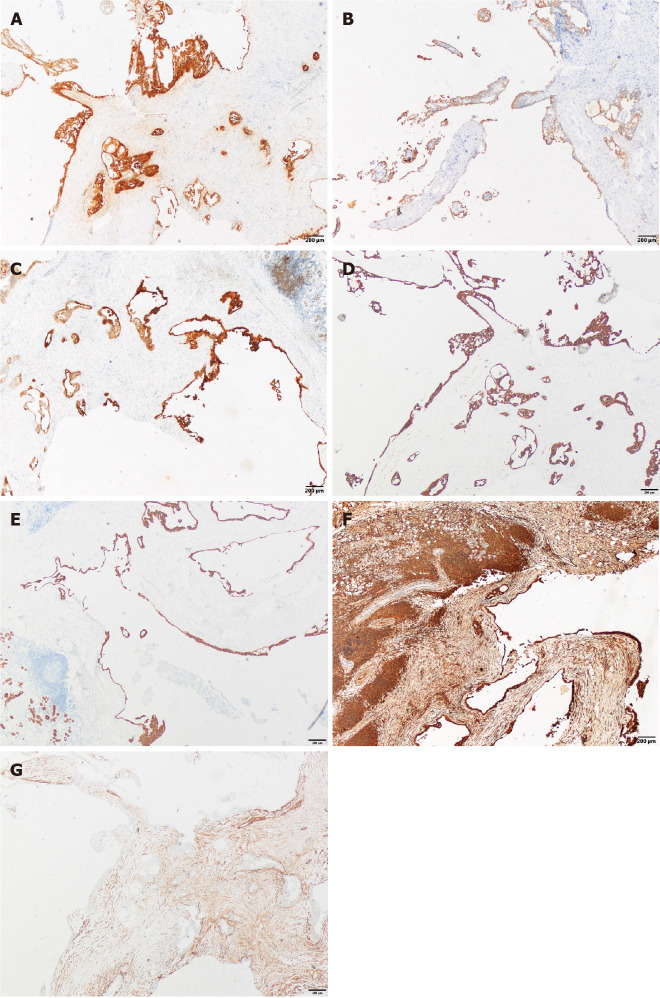

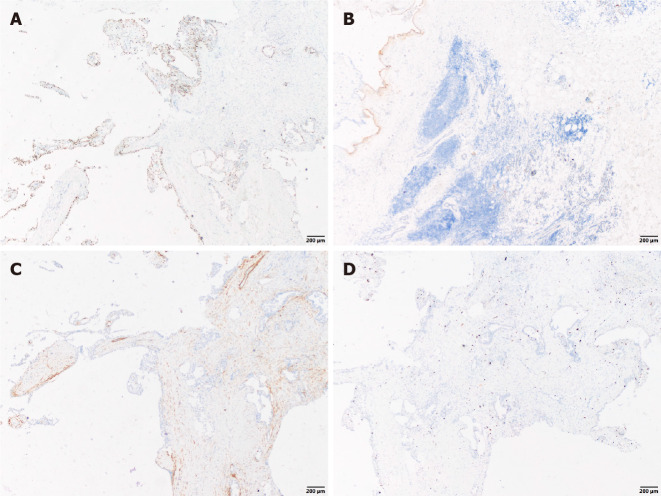

The cystic wall epithelium showed scattered papillary hyperplasia and epithelial nests. The cell volume was small and microcapsules could be observed between cells (Figure 2). Further immunohistochemical staining showed: S-100 (+), Mammaglobin (MMG) (+), Cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 (+), CK7 (+), CK8 (+), Vimentin (Vim) (+), smooth muscle actin (SMA) (-), scattered p63 (+), discovered on gastrointestinal stromal tumor-1 (DOG-1) (-), calponin (-), and a Ki-67 positive rate of 2%. The histopathological analysis confirmed the diagnosis of a breast-like secreting malignancy of the parotid gland (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 2.

Clinical and histological examinations of the tumor tissues. A: A section of the tumor, showing a solid, brownish red, cystic, mass with yellowish green liquid; B: The histological examination of the lesion showing the cystic components, areas of the cyst wall epithelium, and papillary hyperplasia to the cyst cavity (indicated using black arrows).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining (×40). A: Immunostaining for S-100; B: Immunostaining for Mammaglobin; C: Immunostaining for Cytokeratin (CK) 5/6; D: Immunostaining for CK7; E: CK8 (+); F: Vimentin (+); G: Immunostaining for Smooth Muscle Actin.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining (×40). A: Immunostaining for scattered P63; B: Immunostaining for discovered on Gastrointestinal Stromal tumor-1; C: Immunostaining for Calponin; D: Immunostaining for Ki-67.

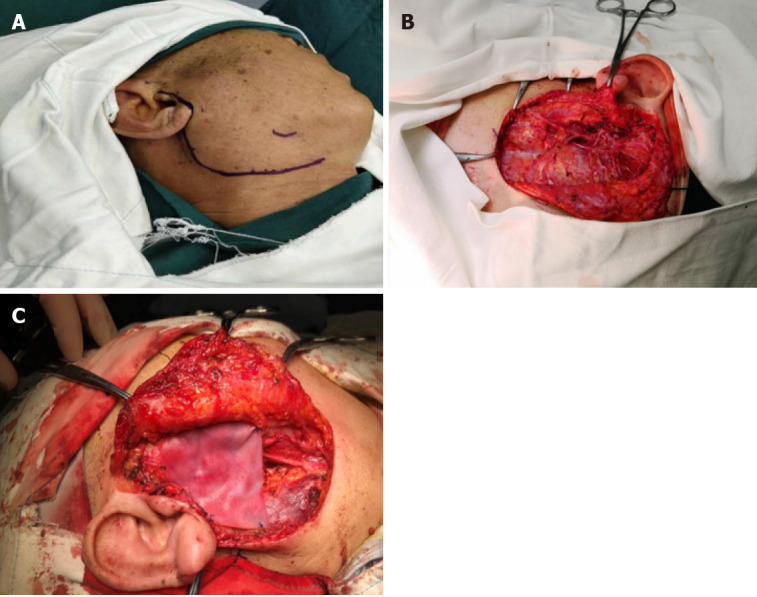

According to the treatment principles for salivary gland tumors[10,11], ipsilateral parotidectomy was performed. We chose the maxillofacial approach, drawing lines along the tragus, bypassing the earlobe downward to the tip of the mastoid, parallel to the posterior edge of the ascending branch to the mandibular angle, 2.0 cm forward parallel to the inferior edge of the mandible, as for the preangular level (Figure 5A), incision of the skin, subcutaneous, platysma muscle, complete resection of the superficial and deep lobes of the parotid gland, and preservation of the facial nerve (Figure 5B). Because the facial nerve was not closely associated with the tumor, the nerve was preserved. A biological patch (ZH-BIO, Ltd, Yantai, China) was implanted at the surgical site to restore the local sunken deformity and prevent the development of Frey’s syndrome. The patient was followed up and received postoperative radiotherapy to prevent recurrence (Figures 5C).

Figure 5.

Surgical management of the patient. A: Design of incision before total lobectomy of the right parotid gland; B: Total lobectomy of the right parotid gland and preservation of facial nerve; C: Implantation of a biological patch to restore the sunken deformity and prevent Frey’s syndrome.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient fully recovered and reported no complications or the development of Frey’s syndrome. All the incisions healed properly without affecting the secretion of the left parotid gland. The right side of the patient’s face was slightly sunken compared to the left side. The facial and auriculotemporal nerves were well preserved, and there were no symptoms of facial paralysis. At the 6 mo postoperative follow-up, the clinical examination revealed no signs or symptoms of recurrence.

DISCUSSION

This article reports a rare case of a gradually growing MASC associated with the right parotid. Due to the unclear pathogenesis and a lack of decisive clinical and imaging features, the definitive diagnosis of MASC is challenging. The patient in this report received right parotidectomy, restoration of the defect, and postoperative radiotherapy. The patient recovered fully and reported no postoperative complications (such as facial paralysis or Frey’s syndrome) or recurrence. Clinically, MASC is typically a painless slow-growing mass that often occurs in the parotid gland and is equally prevalent in men and women[3]. There is no specific age of onset, and the course of the disease may be as long as 30 years. In general, MASC is a low-grade malignant lesion that has good prognosis with a low recurrence rate and rarely metastasizes to local lymph nodes and distant tissues. Although malignant manifestations of MASC (such as pain, facial paralysis, peripheral tissue adhesion) are relatively rare[12], MASC may transform into a high-grade malignant tumor.

In contrast to the low signal intensity on ultrasound, the MRI results for MASC show a high signal intensity relative to muscle on T1 images and low signal intensity relative to the parotid gland on T2 images[13]. In addition, MASC generally has a clear boundary and therefore may be misdiagnosed as a cystic mass or hemangioma. MASC lesions show heterogeneity in ultrasound and MRI, which is of clinical significance[3,14]. Kuwabara et al[14] reported hemorrhage and ferritin deposition in most MRI T2 weighted images. Although ferritin deposition is usually associated with neurological diseases, it remains unclear whether there is any association between the development of salivary mammary gland carcinoma and the nervous system[15].

Histologically, MASC has a lobulated appearance with a tubular arrangement and papillary cystic, microcapsule tissue[16]. Some tumor cells may have variable configurations simultaneously. Most MASC lesions are comprised of multiple cell types, but a few tumor cells are rich in cytoplasm, vesicles, or vacuoles. In contrast, no MASC cells contain zymogen granules, which is a typical characteristic of AciCC[17]. A certain number of tumor cells appear transparent due to the presence of mucous components as the lumen, microcapsule, and large capsules are filled with eosinophilic homogeneous or vesicular secretions[18].

Cell atypia is uncommon, with medium to low degrees of oval vesicular nuclei that have clear nuclear membranes, a centrally located nucleolus, and rare cellular mitosis[3,6].

Immunohistochemistry plays an important role in the diagnosis of MASC. MASC cells are strongly positive for the calcium-binding S100 protein, MMG, and Vim, and negative for DOG-1. In addition, the cells are mainly positive for broad-spectrum cytokeratins (AE1-AE3, CAM5.2, CK7, CK8, CK18, CK19), gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and Sox10, but negative for SMA, calponin, and p63[19,20]. The tumor proliferating antigen for MASC (Ki-67) is generally low (< 5%) in the cells[8,21].

The cytoplasm of MASC cells is vacuolar and does not contain the probasophilic granules peculiar to AciCC tumor cells, which is the main difference between the two lesions[18]. In addition, the immunohistochemical features of AciCC lack a strong positive expression of Smur100, MMG, and Vim, and the majority of cells are positive for DOG-1[7]. Similarly, MASC can be distinguished from mucoepidermoid carcinoma based on p63 (-) and Smur100. In addition, more than 50% of mucoepidermoid carcinomas have characteristic methods of gene translocation and form cyclic adenylate response elements bound to CRTC1-MAML2 or CRTC3-MAML2 fusion genes. The fusion gene for MASC is ETV6-NTRK3[8,22]. In salivary ductal carcinoma, there is an obvious nucleolus and mitotic activity is common. A dilated duct-like structure is occasionally present, but apocrine secretion associated with the epithelial lining of salivary ductal carcinoma can be observed, distinguishing it from MASC[22].

The ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene is associated with MASC and can be detected with either fluorescent in situ hybridization for auxiliary diagnosis or reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction[14,23]. Kuwabara et al[14] reported that the ETV6-NTRK3 gene may cause MASC tissue bleeding because the product of the fusion gene induces angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor. The overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor can induce tumor-related cyst formation, peritumoral edema, and bleeding[15]. In addition, neovascularization is more abundant in MASC than in AciCC. The process of angiogenesis may be crucial in MASC. The interstitial components of the nipple are abundant in MASC[24]. In certain tumors, such as Dabska’s tumor, retiform hemangioendothelioma, and angiosarcoma, nipple formation is related to angiogenesis. Molecular diagnosis is regarded as the gold standard for the identification of MASC; however, a recent study implicated the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene in certain salivary gland malignant tumors including AciCC[25]. Therefore, the diagnostic approach for MASC identification should be comprehensive[17].

MASC is a low-grade malignant salivary gland tumor with a low likelihood of distant metastases. According to the Ki-67 standard, the degree of malignancy for MASC is weaker than that of AciCC. According to the principles of salivary gland treatment, total parotidectomy should be performed for the treatment of MASC[8]. If the tumor is closely related to the facial nerve, the nerve should not be retained during surgical resection. If the distance from the facial nerve is sufficient, the facial nerve should be preserved when possible and surgery should be supplemented with postoperative radiotherapy to ensure a low recurrence rate and maximize the quality of life for patients after the operation[26]. Cervical lymph node dissection can be considered if the tumor has a potential for high-grade transformation or cervical lymph node metastasis[27,28].

Genetic targeted therapy has demonstrated promising potential in the management of oral cancers. The anti-tumor activity of tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) inhibitors has been demonstrated in patients with neurotropic TRK rear-ranged malignancies. Specifically, larotrectinib and entrectinib have been shown to be potent, safe, and promising TRK inhibitors. Targeting netrin proteins has the potential to be a useful treatment option, particularly for patients with unresectable MASC[6,29-31].

CONCLUSION

We report a patient with a right parotid tumor (MASC) who underwent total parotidectomy and postoperative radiotherapy. At the 6-mo postoperative follow up, the patient reported being in good health with no sign of recurrence. However, long-term follow-up is needed to monitor the prognosis. MASC cases are rare with poor specificity. There are no unified diagnostic criteria for MASC; therefore, it is often misdiagnosed as AciCC during preliminary examinations. This case suggests the significance of good differential diagnosis and critical analysis of atypical examination results. In addition, it is necessary to ensure that primary malignant lesions are completely removed, followed by functional preservation surgery to improve the patients’ quality of life postoperatively. The present study highlights the diagnostic difficulties for MASC and reviews the clinical and histological manifestations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We appreciate the contributions of all members involved in the operation, treatment, and study of this case.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: January 18, 2021

First decision: February 11, 2021

Article in press: March 13, 2021

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Grawish ME S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wu YXJ

Contributor Information

Feng-He Min, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Hospital of Stomatology, Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China; Jilin Provincial Key Laboratory of Tooth Development and Bone Remodeling, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China.

Jia Li, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Hospital of Stomatology, Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China.

Bo-Qiang Tao, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Hospital of Stomatology, Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China; Jilin Provincial Key Laboratory of Tooth Development and Bone Remodeling, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China.

Hui-Min Liu, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Hospital of Stomatology, Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China; Jilin Provincial Key Laboratory of Tooth Development and Bone Remodeling, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China.

Zhi-Jing Yang, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Hospital of Stomatology, Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China; Jilin Provincial Key Laboratory of Tooth Development and Bone Remodeling, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China.

Lu Chang, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Hospital of Stomatology, Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China; Jilin Provincial Key Laboratory of Tooth Development and Bone Remodeling, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China.

Yu-Yang Li, Jilin Provincial Key Laboratory of Tooth Development and Bone Remodeling, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China; Department of Oral Implant, Hospital of Stomatology, Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China.

Ying-Kun Liu, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Hospital of Stomatology, Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China; Jilin Provincial Key Laboratory of Tooth Development and Bone Remodeling, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China.

Yi-Wen Qin, Department of Stomatology, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 400016, China.

Wei-Wei Liu, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Hospital of Stomatology, Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China; Jilin Provincial Key Laboratory of Tooth Development and Bone Remodeling, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China. liuweiw@jlu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Khalele BA. Systematic review of mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary glands at 7 years after description. Head Neck. 2017;39:1243–1248. doi: 10.1002/hed.24755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hindocha N, Wilson MH, Pring M, Hughes CW, Thomas SJ. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the salivary glands: a diagnostic dilemma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;55:290–292. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2016.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skalova A, Michal M, Simpson RH. Newly described salivary gland tumors. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:S27–S43. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine P, Fried K, Krevitt LD, Wang B, Wenig BM. Aspiration biopsy of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of accessory parotid gland: another diagnostic dilemma in matrix-containing tumors of the salivary glands. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:49–53. doi: 10.1002/dc.22886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skálová A, Vanecek T, Sima R, Laco J, Weinreb I, Perez-Ordonez B, Starek I, Geierova M, Simpson RH, Passador-Santos F, Ryska A, Leivo I, Kinkor Z, Michal M. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, containing the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene: a hitherto undescribed salivary gland tumor entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:599–608. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9efcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damjanov I, Skenderi F, Vranic S. Mammary Analogue Secretory Carcinoma (MASC) of the salivary gland: A new tumor entity. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2016;16:237–238. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2016.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiosea SI, Griffith C, Assaad A, Seethala RR. Clinicopathological characterization of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands. Histopathology. 2012;61:387–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connor A, Perez-Ordoñez B, Shago M, Skálová A, Weinreb I. Mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary gland origin with the ETV6 gene rearrangement by FISH: expanded morphologic and immunohistochemical spectrum of a recently described entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:27–34. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318231542a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mariano FV, dos Santos HT, Azañero WD, da Cunha IW, Coutinho-Camilo CM, de Almeida OP, Kowalski LP, Altemani A. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands is a lipid-rich tumour, and adipophilin can be valuable in its identification. Histopathology. 2013;63:558–567. doi: 10.1111/his.12192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seifert G, Brocheriou C, Cardesa A, Eveson JW. WHO International Histological Classification of Tumours. Tentative Histological Classification of Salivary Gland Tumours. Pathol Res Pract. 1990;186:555–581. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee DH, Kim JH, Yoon TM, Lee JK, Lim SC. Outcomes of treatment of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the parotid gland. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;58:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2019.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albus J, Batanian J, Wenig BM, Vidal CI. A unique case of a cutaneous lesion resembling mammary analog secretory carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:e41–e44. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oza N, Sanghvi K, Shet T, Patil A, Menon S, Ramadwar M, Kane S. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of parotid: Is preoperative cytological diagnosis possible? Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:519–525. doi: 10.1002/dc.23459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuwabara H, Yamamoto K, Terada T, Kawata R, Nagao T, Hirose Y. Hemorrhage of MRI and Immunohistochemical Panels Distinguish Secretory Carcinoma From Acinic Cell Carcinoma. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2018;3:268–274. doi: 10.1002/lio2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ni H, Zhang XP, Wang XT, Xia QY, Lv JH, Wang X, Shi SS, Li R, Zhou XJ, Rao Q. Extended immunologic and genetic lineage of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands. Hum Pathol. 2016;58:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helmy D, Chang J, Bishop JW, Vong A, Raslan O, Ozturk A. MR imaging findings of a rare pediatric parotid tumor: Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Radiol Case Rep. 2020;15:1460–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2020.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terada T, Kawata R, Noro K, Higashino M, Nishikawa S, Haginomori SI, Kurisu Y, Kuwabara H, Hirose Y. Clinical characteristics of acinic cell carcinoma and secretory carcinoma of the parotid gland. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276:3461–3466. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05604-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laco J, Švajdler M Jr, Andrejs J, Hrubala D, Hácová M, Vaněček T, Skálová A, Ryška A. Mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary glands: a report of 2 cases with expression of basal/myoepithelial markers (calponin, CD10 and p63 protein) Pathol Res Pract. 2013;209:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boon E, Valstar MH, van der Graaf WTA, Bloemena E, Willems SM, Meeuwis CA, Slootweg PJ, Smit LA, Merkx MAW, Takes RP, Kaanders JHAM, Groenen PJTA, Flucke UE, van Herpen CML. Clinicopathological characteristics and outcome of 31 patients with ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene confirmed (mammary analogue) secretory carcinoma of salivary glands. Oral Oncol. 2018;82:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ngouajio AL, Drejet SM, Phillips DR, Summerlin DJ, Dahl JP. A systematic review including an additional pediatric case report: Pediatric cases of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;100:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffith CC, Stelow EB, Saqi A, Khalbuss WE, Schneider F, Chiosea SI, Seethala RR. The cytological features of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma: a series of 6 molecularly confirmed cases. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:234–241. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Díaz-Flores L, Gutiérrez R, García MDP, Sáez FJ, Díaz-Flores L Jr, Madrid JF. Piecemeal Mechanism Combining Sprouting and Intussusceptive Angiogenesis in Intravenous Papillary Formation Induced by PGE2 and Glycerol. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2017;300:1781–1792. doi: 10.1002/ar.23599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourgeois JM, Knezevich SR, Mathers JA, Sorensen PH. Molecular detection of the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion differentiates congenital fibrosarcoma from other childhood spindle cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:937–946. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200007000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayre G, Hyrcza M, Wu J, Berthelet E, Skálová A, Thomson T. Secretory carcinoma of the major salivary gland: Provincial population-based analysis of clinical behavior and outcomes. Head Neck. 2019;41:1227–1236. doi: 10.1002/hed.25536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baghai F, Yazdani F, Etebarian A, Garajei A, Skalova A. Clinicopathologic and molecular characterization of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary gland origin. Pathol Res Pract. 2017;213:1112–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez MF, Akhtar I, Manucha V. Additional diagnostic features of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma on cytology. Cytopathology. 2018;29:100–103. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki K, Yagi M, Kanda A, Kobayashi Y, Konishi M, Miyasaka C, Tashiro T, Iwai H. Mammary Analogue Secretory Carcinoma Presenting as a Cervical Lymph Node Metastasis of Unknown Primary Site: A Case Report. Case Rep Oncol. 2017;10:192–198. doi: 10.1159/000457949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siddique N, Raza H, Ahmed S, Khurshid Z, Zafar MS. Gene Therapy: A Paradigm Shift in Dentistry. Genes (Basel) 2016;7 doi: 10.3390/genes7110098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kheder ES, Hong DS. Emerging Targeted Therapy for Tumors with NTRK Fusion Proteins. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:5807–5814. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drilon A, Li G, Dogan S, Gounder M, Shen R, Arcila M, Wang L, Hyman DM, Hechtman J, Wei G, Cam NR, Christiansen J, Luo D, Maneval EC, Bauer T, Patel M, Liu SV, Ou SH, Farago A, Shaw A, Shoemaker RF, Lim J, Hornby Z, Multani P, Ladanyi M, Berger M, Katabi N, Ghossein R, Ho AL. What hides behind the MASC: clinical response and acquired resistance to entrectinib after ETV6-NTRK3 identification in a mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC) Ann Oncol. 2016;27:920–926. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drilon A, Siena S, Ou SI, Patel M, Ahn MJ, Lee J, Bauer TM, Farago AF, Wheler JJ, Liu SV, Doebele R, Giannetta L, Cerea G, Marrapese G, Schirru M, Amatu A, Bencardino K, Palmeri L, Sartore-Bianchi A, Vanzulli A, Cresta S, Damian S, Duca M, Ardini E, Li G, Christiansen J, Kowalski K, Johnson AD, Patel R, Luo D, Chow-Maneval E, Hornby Z, Multani PS, Shaw AT, De Braud FG. Safety and Antitumor Activity of the Multitargeted Pan-TRK, ROS1, and ALK Inhibitor Entrectinib: Combined Results from Two Phase I Trials (ALKA-372-001 and STARTRK-1) Cancer Discov. 2017;7:400–409. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]