ABSTRACT

Plant growth, morphogenesis and development involve cellular adhesion, a process dependent on the composition and structure of the extracellular matrix or cell wall. Pectin in the cell wall is thought to play an essential role in adhesion, and its modification and cleavage are suggested to be highly regulated so as to change adhesive properties. To increase our understanding of plant cell adhesion, a population of ethyl methanesulfonate-mutagenized Arabidopsis were screened for hypocotyl adhesion defects using the pectin binding dye Ruthenium Red that penetrates defective but not wild-type (WT) hypocotyl cell walls. Genomic sequencing was used to identify a mutant allele of ELMO1 which encodes a 20 kDa Golgi membrane protein that has no predicted enzymatic domains. ELMO1 colocalizes with several Golgi markers and elmo1−/− plants can be rescued by an ELMO1-GFP fusion. elmo1−/− exhibits reduced mannose content relative to WT but no other cell wall changes and can be rescued to WT phenotype by mutants in ESMERALDA1, which also suppresses other adhesion mutants. elmo1 describes a previously unidentified role for the ELMO1 protein in plant cell adhesion.

KEY WORDS: Adhesion, Cell wall, Mannose, ELMO1, Arabidopsis

Summary: The new cell adhesion locus ELMO1 describes a Golgi protein required for cell adhesion and mannose accumulation in the cell wall of Arabidopsis.

INTRODUCTION

The regulation of cell adhesion and cell separation in angiosperms is crucial for growth and development and is dependent upon the cell wall that lies between adjacent cells. During cytokinesis in plants, a new membrane-bound cell plate expands to fuse with the primary cell wall of the daughter cells (Miart et al., 2014; van Oostende-Triplet et al., 2017). This cell plate is formed by the fusion of vesicles from the Golgi at the phragmoplast, a structure established during anaphase that acts as the scaffold for cell plate construction (Reichardt et al., 2007; Verma, 2001). Soon after vesicle fusion and the establishment of the cell plate, callose is deposited, with cellulose accumulating and replacing callose as the plate matures (Drakakaki, 2015; Samuels et al., 1995). As the plate expands to fuse with the existing walls, pectin, hemicellulose and cellulose are deposited on either side of the plate, forming the primary cell walls of the daughter cells (Miart et al., 2014; van Oostende-Triplet et al., 2017). The daughters are formed with the completion of the new primary wall but remain connected by the cell plate, which then becomes the middle lamella region (Staehelin and Hepler, 1996). During cell growth and differentiation, old cell wall material is pushed away from the plasma membrane while new material is deposited at the membrane, providing an explanation for the high concentration of pectin in the middle lamella as a result of its early deposition at the cell plate during cell division (Keegstra, 2010).

In the cell walls of dicots the pectin family are polymers of galacturonic acid, predominantly homogalacturonan (HG), and less abundant rhamnogalacturonan I (RG-I) and rhamnogalacturonan II (RG-II) (Mohnen, 2008). HG is a linear polymer composed of galactopyranosyluronic acid (GalpA) that undergoes methylesterification and O-acetylation, whereas RG-I is composed of repeating Rhamnose-GalA (Rha-GalA) units, partially O-acetylated, and RG-II is composed of 1,4-linked GalA residues that have oligosaccharide sidechains and branched structures (Ridley et al., 2001). Though all three of these pectins contribute to the structure and function of the cell wall, HG pectin is thought to be primarily responsible for adhesion and is concentrated in the middle lamella and at cellular junctions (Daher and Braybrook, 2015).

The synthesized HG pectin polysaccharide deposited at the cell wall and middle lamella is highly methylesterified and then can be de-methylesterified by pectin methylesterases (PMEs) localized to the cell wall (Mohnen, 2008). The PME initiates the hydrolysis of the methyl-ester bond at the C-6 residues of the HG polymer to remove the methyl group and creates a negative charge on the carboxyl group of the backbone (Sénéchal et al., 2014). As a result of its change in charge, physicochemical and consequently mechanical properties of the cell wall are greatly modified. Furthermore, the de-esterified pectin is able to ionically bond with calcium cations. In its esterified state, in vitro, the HG pectin is more fluid; de-esterification allows for calcium cross-linking, causing the pectin to gel into a more rigid matrix structure. This phenomenon may occur in vivo in the middle lamella in the presence of calcium (Daher and Braybrook, 2015; Wolf and Höfte, 2014). The enzymatic activity of PMEs is countered by pectin methylesterase inhibitors (PMEIs). To restrict de-esterification, the PMEI forms a stable noncovalent complex with PME, preventing the methyl substrate from binding to the putative active site on the methylesterase (Harholt et al., 2010; Wormit and Usadel, 2018).

Analyses of pectin deposition, synthesis and modification support the significant role of pectin in cellular adhesion. The Arabidopsis EMB30 (GNOM) gene, which encodes a protein similar to yeast Sec7p, and is required for directing the transport of vesicles from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi, is important for cellular growth and adhesion during development (Shevell et al., 2000). The emb30 mutant disrupts the localization of pectin in the secretory pathway and affects adhesion and, as a result, growth. The Trans-Golgi-Network (TGN) ECHIDNA protein also affects trafficking of cell wall polysaccharides and the integrity of the cell wall (Gendre et al., 2011; 2013). The level of esterification and de-esterification of pectin, as well as the composition of the middle lamella, has been suggested to impact cellular adhesion. HG pectin and calcium ions are abundant in the middle lamella, and de-esterification causes the formation of a pectate gel in vitro (Daher and Braybrook, 2015). The level and pattern of methylesterification affects physical properties including resistance to compressibility of the extracellular matrix (ECM) (Willats et al., 2001). Increased PMEI expression, which causes higher levels of pectin methylesterification, has been linked to inhibition of growth in Arabidopsis (Jonsson et al., 2021; Peaucelle et al., 2011; Willats et al., 2001). Moreover, demethylesterification reveals substrates for pectate lyase and homogalacturonase, and this instead can lead to a loss of cell adhesion. These findings indicate that changes to the structure of the middle lamella influence cellular adhesion and that fine tuning of the methylesterification level of HG is required for proper morphogenesis.

Glycosyltransferases and methyltransferases involved in the synthesis and modification of pectin have emerged as possible key players in cellular adhesion. The QUASIMODO1 gene (QUA1) encodes a glycosyltransferase, and qua1-1 and qua1-2 mutants display a dwarfed growth and defective adhesion phenotype in Arabidopsis (Bouton et al., 2002). These mutants also have cell protrusions occurring in the cotyledons, leaves and hypocotyls, as well as cell detachment and gapping at the hypocotyl, indicating failed cellular adhesion. Biochemical analyses indicate that qua1-1 mutants have 25% less HG pectin in the cell wall than wild type (WT), and this is corroborated by reduced immunohistochemical staining of pectin epitopes, whereas levels of rhamnose, arabinose and galactose remained the same (Bouton et al., 2002). In addition, in cell culture qua1-1 mutant shows lower levels of methyl-esterification of pectin (Leboeuf et al., 2005).

Mutants of the QUASIMODO2 gene (QUA2), which encodes a membrane protein with HG methyltransferase activity (Du et al., 2020) localized to the Golgi, show similar phenotypes to qua1-1 and qua1-2, further indicating that the synthesis and modification of pectin affects cellular adhesion. qua2-1 mutants also have stunted growth, defective cellular adhesion and a 50% decrease in HG pectin (Mouille et al., 2007). However, unlike qua1 mutants, the percentage of methylesterification of HG pectin in qua-2 mutants is comparable with that of WT plants (Mouille et al., 2007). Separately isolated alleles of QUA2, initially characterized as the TUMOROUS SHOOT DEVELOPMENT2 (TSD2) gene, also have reduced cellular adhesion and, in extreme mutants, display disorganized tumorous growth as well as dwarfed growth (Krupková et al., 2007). Here too, pectin modification by methyltransferases appears to affect cellular adhesion.

Together, the analysis and isolation of QUA1 and QUA2 mutants indicate that the amount of pectin synthesized, and its esterification by Golgi-localized glycosyltransferase and methyltransferase enzymes, directly affect cellular adhesion. However, the isolation of QUASIMODO3 mutants provides conflicting findings complicating the model of cellular adhesion dictated by HG pectin levels. QUA3 has a high amino acid similarity to the pectin methyl transferase QUA2, and is localized to the Golgi (Miao et al., 2011). Unlike QUA2, RNA interference-induced qua3i mutants do not display cellular adhesion defects nor reduced HG pectin content. Differences in pectin methylation, however, were observed in qua3i compared with the WT (Miao et al., 2011). These findings indicate that both the levels and degree of methylesterification are crucial for cell adhesion.

Although overall the qua mutants suggest that pectin deficiency is responsible for defective cellular adhesion, the isolation of other HG defective and abnormal cell adhesion mutants has indicated that this is not always the case. Conversely, the friable1 (frb1) adhesion mutant in a gene annotated as a putative O-fucosyltransferase (DUF246) has no effect on pectin levels, but instead reduces pectin methylesterification, galactose- and arabinose-containing oligosaccharides in the Golgi, and extensin and xyloglucan microstructure (Neumetzler et al., 2012). The frb1 mutant phenotype includes cell dissociation manifested in the sloughing of cells and crumbling of plant tissue.

Mutations to another Golgi-localized protein annotated as a putative O-fucosyltransferase, also with a DUF246 domain, do not show the same cellular adhesion defect. ESMERALDA1 (ESMD1) was isolated as a suppressor of qua2-1, and also suppresses frb1-1, and the esmd1-1 mutants have no difference in phenotype compared with WT (Verger et al., 2016). Normal cellular adhesion was restored in esmd1-1/qua2-1 plants as well as in the triple mutant esmd1-1/qua2-1/frb1, but the double mutant qua2-1/frb1 displayed non-additive defective cellular adhesion (Verger et al., 2016). esmd1-1 acts as a suppressor of qua2 and frb1mutants, and lack of additivity in these mutant phenotypes and co-suppression suggest that qua2-1 and frb1 function in the same molecular signaling pathway. esmd1-1 does not restore HG content of qua2-1 mutants and the results suggest the existence of an as yet undefined signaling pathway likely responsible for the maintenance of cellular adhesion (Verger et al., 2016).

Although pectin appears to be a major contributor to cell adhesion, there are other cell wall components that contribute to cell wall structure and some may play a more minor role in adhesion. The irregular xylem8 (irx8) mutant of a putative HG galacturonosyltransferase, has a reduction in xylan and HG content, causing dwarfed growth but normal cellular adhesion (Persson et al., 2007). The hemicellulose glucomanan appears to help strengthen the cell wall, and xyloglucan may act as spacer polymers to provide structural integrity (Goubet et al., 2009; Miedes et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2016). Cellulose itself is not thought to contribute to adhesion, yet its crosslinking to hemicellulose and pectin is important in cell wall integrity, and extensins are thought to aid in this crosslinking (Du et al., 2020; Showalter and Basu, 2016). The GPI anchored, heavily glycosylated, cell surface arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs) have been suggested to play a role in adhesion but there is not as yet direct evidence (Kjellbom et al., 1997; Showalter and Basu, 2016; Tan et al., 2013).

To further explore how plant cells adhere, a mutational screen of Arabidopsis seedlings employed the pectin binding Ruthenium Red dye that can enter adhesion deficient, but not WT, hypocotyls (Verger, 2014; Šola et al., 2019) One of the recovered mutants named elmo1 has patchy red staining of the hypocotyl, curling or sloughing of cells at the hypocotyl surface and a reduced mannose content. Whole-genome sequencing analysis identified the causative mutation and describes a novel 20 kDa Golgi membrane protein with no identifiable catalytic domains. elmo1 describes a previously unidentified role for ELMO protein in cell adhesion.

RESULTS

Isolation of cellular adhesion mutant lines

Ruthenium Red can stain roots but not hypocotyls of WT dark-grown seedlings, but hypocotyls of the cell adhesion mutants qua2-1 and frb1-1 do stain red, presumably because the dye can penetrate and bind to de-esterified pectin (Verger, 2014; Šola et al., 2019). With the goal of finding key genes involved in adhesion, 5000 WT Arabidopsis seeds were mutagenized with ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS), self-crossed and the M2 (mutagenized F2) population were collected in 191 pools. Ruthenium Red staining was then used to identify adhesion-defective mutant plants from these pools.

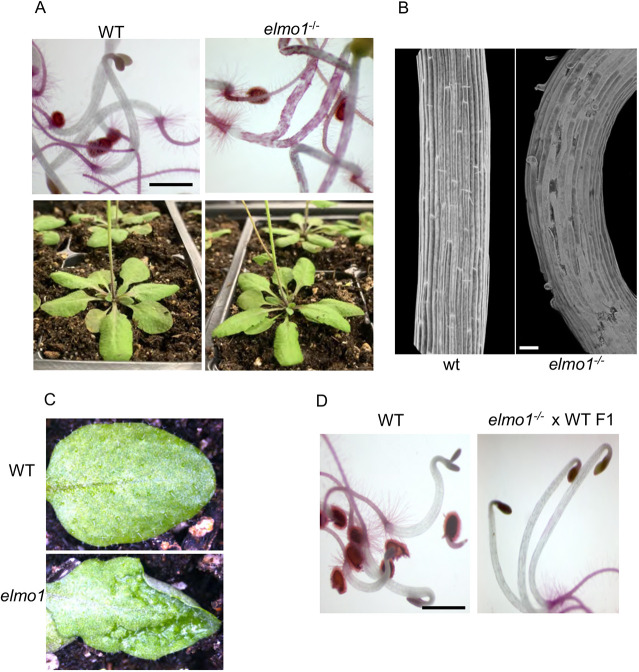

One mutant was named elmo1 in reference to the beloved Sesame Street character who has curly red fur. The initial parental elmo1 line was isolated from the pool and grown on agar, then transferred to soil to self-cross and produce M3 elmo1 offspring. The M3 elmo1 seedlings were stained to verify the inheritance of the adhesion mutation and all seedlings stained red (Fig. 1A) indicating that the M2 isolate was homozygous for the mutation. elmo1−/− showed patchy Ruthenium Red staining of the hypocotyl, curling cells and slight breakage, and displayed a clear adhesion defective phenotype. Confocal microscopy of propidium iodide-stained dark-grown hypocotyls showed that, relative to WT, elmo1−/− hypocotyl cells curled away from each other, leaving gaps and disorganized regions (Fig. 1B). On soil, elmo1−/− appeared as the WT (Fig. 1A), except that in some older leaves a rough and bubbling appearance was observed (Fig. 1C) similar to, but not as severe as, the frb1 and qua mutants (Bouton et al., 2002; Mouille et al., 2007; Neumetzler et al., 2012).

Fig. 1.

elmo1 shows adhesion defects. (A) WT and elmo1−/− dark-grown hypocotyls stained with Ruthenium Red (top panel) or grown on soil (bottom panel). (B) Confocal microscopy imaging of propidium iodide-stained elmo1−/− and WT dark-grown hypocotyls. (C) Soil grown leaves from the indicated genotype. (D) F1 generation of a backcross of M3 elmo1−/− to WT, showing adhesion is restored and elmo1 is recessive. Scale bars: 1 mm (A,D); 50 µm (B).

M3 elmo1−/− seedlings were back-crossed to WT A. thaliana Col0 to allow the segregation of other EMS-induced mutations in the genome and to characterize the dominance of the mutation. These heterozygote F1 offspring were stained with Ruthenium Red and none of the hypocotyls of the F1 seedlings stained red (Fig. 1D), indicating that the mutation is recessive to the WT allele.

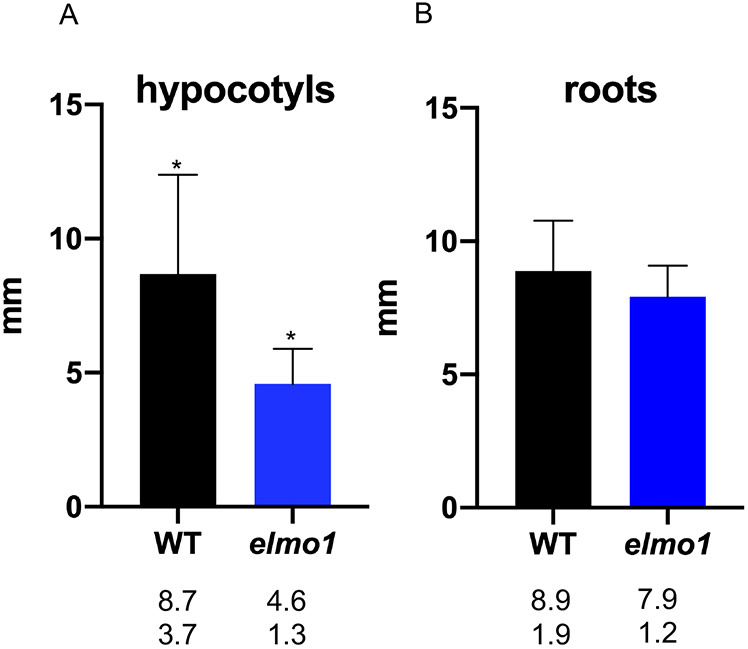

To identify additional phenotypes, elmo1−/− seedlings were grown on agar plates, and the lengths of the hypocotyls and roots were measured. Fig. 2 shows that, relative to WT seedlings, elmo1−/− seedlings had shorter hypocotyls (unpaired two tailed t-test, P<0.01) but roots of similar length (unpaired two tailed t-test, P>0.01).

Fig. 2.

elmo1 hypocotyls, but not roots, are shorter than WT hypocotyls. (A,B) Dark-grown elmo1 and WT hypocotyls (A) or roots (B) were measured using ImageJ. Length in mm. *P<0.01 (unpaired two tailed t-test). Numbers below each bar show mean (top) and standard deviation (bottom).

elmo1 is a new cell adhesion locus

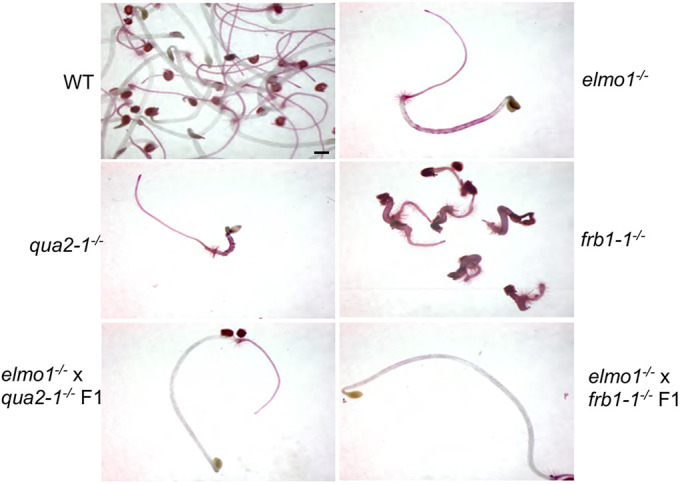

To determine whether elmo1 is a new allele of previously identified adhesion mutants, M3 elmo1−/− plants were crossed with qua2-1−/− and frb1-1−/− plants to assess complementation, and Ruthenium Red staining was used to assay the phenotype of the dark-grown hypocotyls of the F1 offspring of these crosses. Fig. 3 shows that, although elmo1−/−, qua2-1−/− and frb1−/− all stained with the dye and showed visible adhesion defects, the F1 of elmo1−/−×qua2-1−/− and elmo1−/−×frb1−/− offspring displayed a WT adhesion phenotype, with no staining or abnormal curling cells. The restoration of normal adhesion in the offspring of these crosses resulted from genetic complementation, arguing that the elmo1 mutation does not occur within the QUA2 or FRB1 gene.

Fig. 3.

elmo1 is not complemented by qua-2 or frb-1. The indicated dark-grown hypocotyls were stained with Ruthenium Red dye. F1 progeny do not have adhesion defects, indicating elmo1 is not a new allele of QUA2 or FRBL1. Scale bar: 1 mm.

Genome sequence of elmo1−/−

To identify the mutation causing the elmo1−/− phenotype, F1 seeds of the elmo1−/−×WT cross were sown on soil and self-crossed. Of the F2 offspring, a quarter were expected to be homozygous for the elmo1 cell adhesion mutation, but other EMS-induced background mutations present in these F2 elmo1−/− would be expected to have segregated and appear at less than 100% frequency. Whole-genome sequencing of the pooled elmo1−/− F2 allows for the identification of mutations that occur with 100% frequency, and thus are candidate causative mutations (Verger et al., 2016). The F2 seeds were therefore collected and germinated and grown in liquid media for 4 days in the dark at 20°C and stained with Ruthenium Red to identify the individuals homozygous for elmo1. We pooled 450 dark-grown F2 hypocotyls from the elmo1−/−×WT cross displaying the elmo1 mutant phenotype and the extracted DNA underwent whole-genome sequencing. artMAP software (Javorka et al., 2019) was used to analyze sequencing data and identified only four mutations occurring with 100% frequency (Fig. S1). However, of the four, three were mutations in transposable elements and these candidates were given lower priority owing to the low likelihood of their role in adhesion. The remaining mutation occurring with 100% frequency was mapped to position 13828788 in At2g32580, where the mutation causes an adenine in the place of a guanine at the 3′ splice junction of the 2nd intron (Fig. S2). This change likely could impact mRNA transcript levels of the gene.

In WT Arabidopsis, At2g32580 is predicted to encode a 183 amino acid 19.967 kDa protein (DUF1068) (Figs S2, S3). The mRNA is expressed in most plant structures and during almost all developmental stages (TAIR; ThaleMine), but whereas ELMO is predicted to be a Golgi membrane protein, there are no identifiable catalytic or binding domains present (TAIR; ThaleMine). InterPro (Mitchell et al., 2019) predicts a signal sequence, a membrane anchor, a Golgi lumenal domain and a coiled structure.

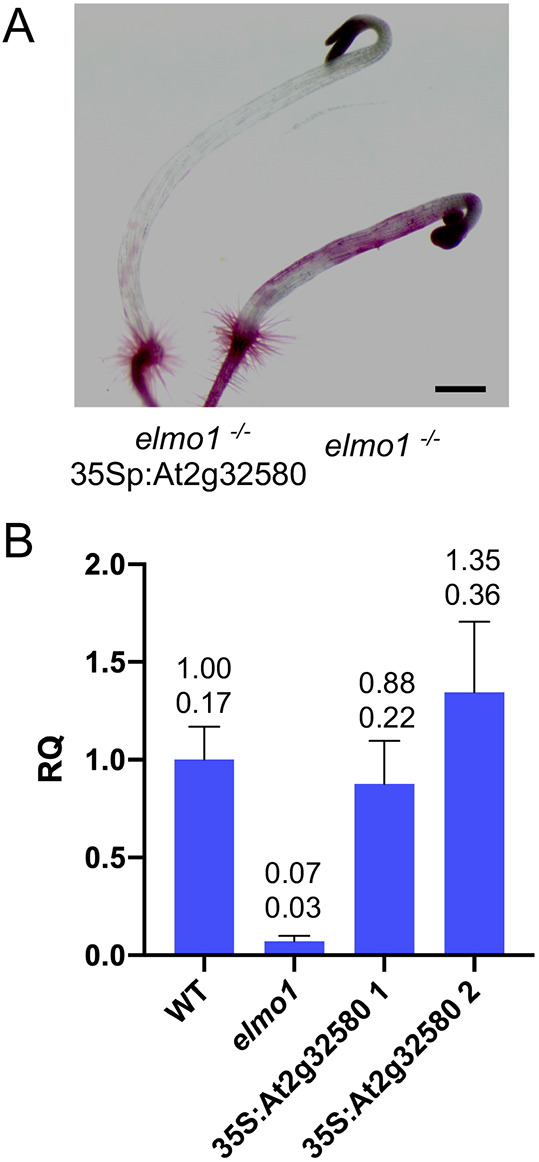

elmo−/− is complemented by At2g32580

To verify that the mutation in At2g32580 is indeed responsible for the elmo1 phenotype, the WT coding region of At2g32580 using the native start and stop codons was expressed under the control of the 35S promoter by transformation of elmo1−/− plants. T2 hygromycin-resistant plants were then grown in liquid medium in the dark for 4 days, and the hypocotyls were stained with Ruthenium Red. Fig. 4A shows that elmo1−/− 35Sp:At2g32580 transformed seedlings have greatly reduced staining and no visible cell adhesion defects relative to elmo1−/− seedlings, indicating that At2g32580 can indeed complement the elmo1 allele.

Fig. 4.

At2g32580 complements elmo1−/−. (A) Ruthenium Red-stained dark-grown hypocotyls of elmo1−/− or elmo1−/− transformed with 35S:At2g3250. (B) Relative quantitation (RQ) using RT-qPCR of the indicated genotype, relative to actin. 35S:At2g32580 1 and 35S:At2g32580 2 indicate two independent elmo1−/− 35S:At2g3250 transformants. Numbers above each bar show mean (top) and standard deviation (bottom). The elmo1 mutant has an almost 6-fold reduction (unpaired two tailed t-test, P<0.01) of At2g32580 expression relative to WT. At2g32580 levels in the two isolates of elmo1−/− 35Sp:At2g32580 are not distinguishable from WT (unpaired two tailed t-test, P>0.01). Scale bar: 0.5 mm.

The elmo1 mutation in At2g32580 is predicted to inhibit the removal of the second intron, and thereby cause a change in mRNA accumulation. RT-qPCR was used to measure the levels of At2g32580 mRNA expression relative to actin in dark-grown hypocotyls of WT, elmo1−/− and two different elmo1−/− 35Sp:At2g32580 independent transformants (1,2) (Fig. 4B). The elmo1 mutant showed an almost 6-fold reduction (unpaired two tailed t-test, P<0.01) of At2g32580 expression relative to WT. At2g32580 levels in the two isolates of elmo1−/− 35Sp:At2g32580 were not distinguishable from WT (unpaired two tailed t-test, P>0.01). The results indicate that the mutation at the predicted splice junction of intron 2 and exon 3 leads to a dramatic reduction in the expression of exon 3. Although the mutation is expected to eliminate splicing at this junction, it remains to be determined how the levels of protein are affected; as exon three is not detected by RT-qPCR (Fig. 4B) it is likely that at least the carboxyl terminal two thirds of the protein is not expressed.

Although the elmo1 mutation was complemented by an ELM01-GFP fusion protein, and was the only mutation of significance that appeared at 100% frequency in the segregation and sequencing analysis, an independent allele was obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Centre (ABRC) to provide further evidence that elmo1 is linked to cell adhesion defects. The new mutation (now called elmo1-2) is a T-DNA insertion (SALK019927C) located 252 base pairs 5′ to the predicted start of translation, in the 350 bp long 5′ untranslated region (Fig. S2). Although WT hypocotyls do not stain with Ruthenium Red, elmo1-2−/−seedlings homozygous for this T-DNA insertion did stain, but more lightly than elmo1-1−/− (Fig. S4A). Confocal microscopy imaging of propidium iodide-stained dark-grown hypocotyls is shown in Fig. S4B, and reveals that elmo1-2−/− cells appeared more disorganized than in WT, but did not curl away as in elmo1-1−/−. Thus elmo1-2−/−appears to be a weaker allele than elmo1-1−/−.

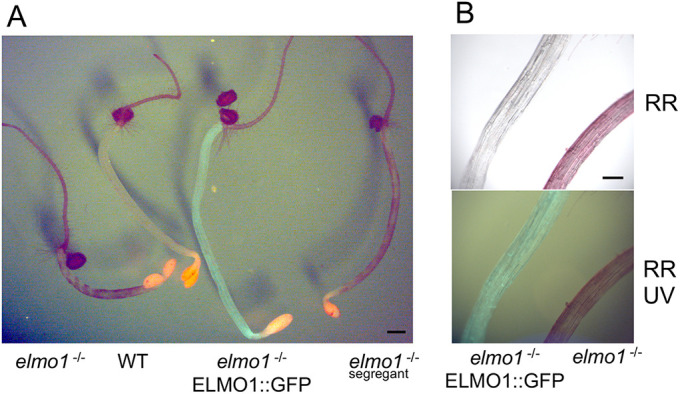

ELMO1 is a Golgi protein

ELMO1 is predicted to be localized to the Golgi (SUBA and ARAPORT), and an extensive proteomic analysis identifies ELMO1 as resident to the medial Golgi (Parsons et al., 2019). To provide a separate confirmation of the proteomics localization, At2g32580 was also expressed with a carboxyl-terminal GFP domain in elmo1−/− plants. The T2 generation of this transformation is shown in Fig. 5A, in which WT, elmo1−/− and elmo1−/−:35Sp:ELMO1::GFP dark-grown seedlings were stained with Ruthenium Red and visualized under UV to detect GFP. Magnification of the same seedlings in Fig. 5A are shown in Fig. 5B. The results indicate that not only does the ELMO1-GFP fusion express in hypocotyls, but the fusion protein can also rescue the elmo1 mutation such that transformants have no adhesion defects and do not stain with dye (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

35S:At2g35280::GFP complements elmo1−/−. (A) Ruthenium Red-stained dark-grown hypocotyls of elmo1−/− or elmo1−/− transformed with 35S:At2g3250::GFP (ELMO::GFP) visualized under 488 nm excitation and 510 nm emission light for GFP. Sufficient white light was included to also visualize the whole seedling. (B) Magnification of the hypocotyl of elmo1−/− 35S:At2g3250::GFP (ELMO1::GFP) and elmo1−/− dark-grown seedling detecting Ruthenium Red (RR) and GFP. Scale bars: 0.5 mm (A); 200 µm (B).

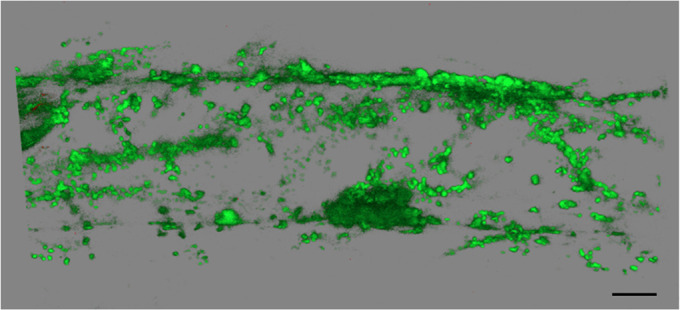

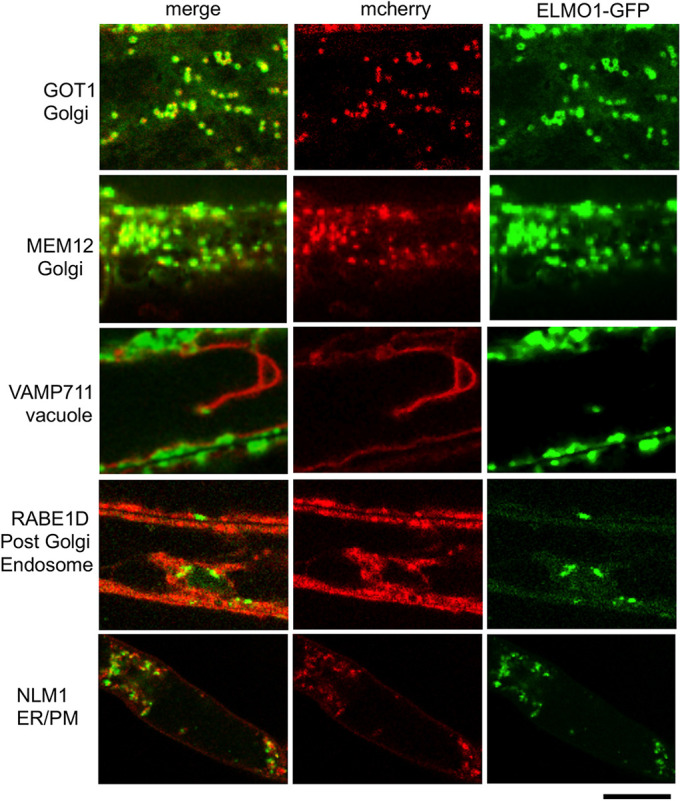

To determine where the ELMO-GFP is localized, a z-stack was generated by confocal microscopy and 3D rendering, and Fig. 6 shows that ELMO-GFP accumulated in a network of cytoplasmic organelles throughout the single root cell displayed. A similar localization was seen in all tissue types of the plant. Plants expressing ELMO1-GFP were then crossed to plants expressing one of five mCherry Wave line markers for cellular compartments; Golgi GOT1, Golgi MEMB12, ER NLM1, post Golgi endosome RABE1D and vacuole Vamp711 (Geldner et al., 2009). The F1 seeds of the cross were grown on agar plates and visualized by confocal microcopy. Fig. 7 shows that the two Golgi markers (red) had significant overlap in localization with ELMO1-GFP. ELMPO-GFP appeared to be distinct from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), post Golgi and vacuole markers, confirming that ELMO1-GFP is a Golgi protein. In some images, ELMO1-GFP appeared in rings, indicative of Golgi membrane structures. GOT1-RFP was detected within some of these rings, but it is not known if this represents a luminal distribution of GOT1 within a Golgi body. Although the proteomic analysis (Parsons et al., 2019) identified ELMO1 as a medial Golgi protein, the analysis here was only able to localize ELMO1 to the Golgi, not to a specific compartment within the Golgi.

Fig. 6.

35S:At2g35280::GFP localization. A confocal microscope z-stack was generated using 488 nm excitation and 510 nm emission of elmo1−/− 35S:At2g35280::GFP, and Leica software was used to render a 3D image. A single root cell is shown. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Fig. 7.

35S:At2g35280::GFP colocalizes with Golgi markers. Seedlings expressing elmo1−/− 35S:At2g35280::GFP and the indicated marker protein-mCherry fusion were visualized by sequential confocal microscope scanning. Green is GFP, red is mCherry. Scale bar: 10 µm.

elmo1 has reduced mannose

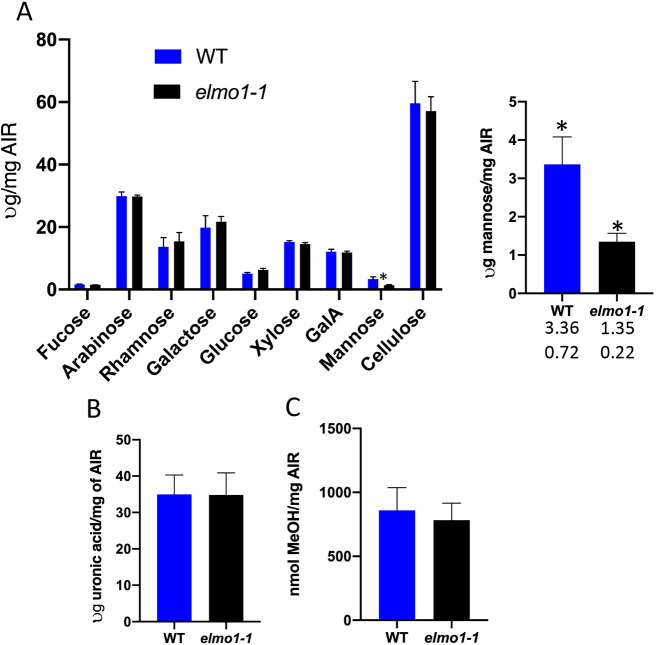

There are multiple causes for loss of cell adhesion, and to determine how elmo1−/− might induce a defect, a total cell wall analysis was performed (Fig. 8). No difference between elmo1−/− and WT was detected for cellulose, or any of the neutral sugars (unpaired two tailed t-tests, P>0.01; Fig. 8A), except a 2.6-fold reduction (unpaired two tailed t-test P<0.01) in mannose levels. In addition, both the galacturonic acid levels in the ammonium oxalate-extracted alcohol insoluble residue (AIR) (GalA; unpaired two tailed t-test, P>0.05; Fig. 8A) and ammonium oxalate-extracted galacturonic acid (unpaired two tailed t-test, P>0.05; Fig. 8B) are the same for elmo1−/− and WT. The absolute levels of pectin methylesterification were also unchanged (unpaired two tailed t-test, P>0.05; Fig. 8C) in elmo1−/− relative to WT levels.

Fig. 8.

elmo1−/− has reduced mannose. (A-C) An alcohol insoluble fraction (AIR) from dark-grown seedlings was used to measure, by HPAEC-PAD, neutral sugars content and cellulose. (A) No significant differences between elmo−/− and WT were detected (unpaired two tailed t-test, P>0.05) for all sugars and cellulose except for mannose. The mannose levels are also shown on a larger scale to the right [numbers below each bar show mean (top) and standard deviation (bottom)]. *P<0.01 (unpaired two tailed t-test). (B) Pectin was measured by extracting uronic acids with ammonium oxalate from the indicated genotype. (C) Total released methanol from AIR preparations indicates degree of pectin methylesterification between the indicated genotype. No significant differences were detected (unpaired two tailed t-test, P>0.05).

Mutations in esmd1-1, a DUF246-containing protein (Verger et al., 2016), can suppress adhesion mutations that are effected by both reduced pectin content in qua2-1 (Mouille et al., 2007) and qua1-1 (Bouton et al., 2002), but also the frb1 mutant that alters pectin esterification, glucose and arabinose levels. As elmo1-1 reduced the mannose content, and caused a milder adhesion defect than qua and frb1 mutants, it was of interest to see whether esmd1-1 could suppress elmo1-1. elmo1-1−/− was crossed with esmd1−/− and the F2 were screened by PCR and sequencing of the two genes for plants homozygous for both mutations. Fig. S5 shows dark-grown Ruthenium Red-stained seedlings from WT, elmo1-1−/−, esmd1−/− and elmo1-1−/−/esmd1−/− individuals and indicates that esmd1-1 can indeed suppress elmo1-1−/−, as the phenotype is restored to WT.

ELMO family

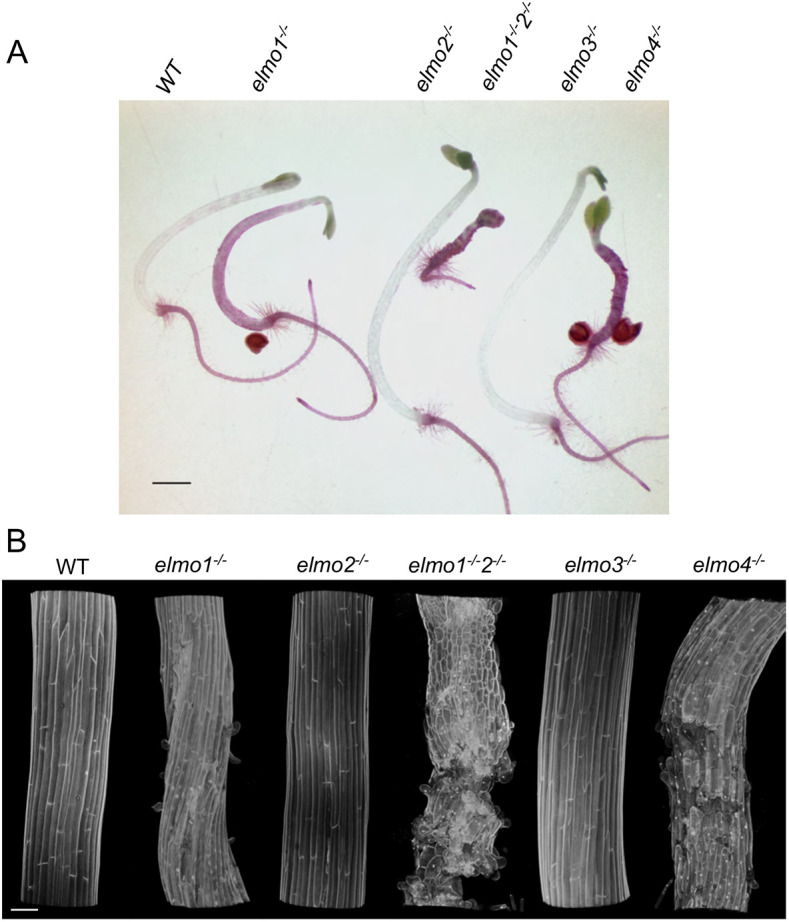

Database queries indicate that At2g32580 (ELMO1) has five Arabidopsis homologs that have all been named DUF1068 (UniProt) and have similar predicted molecular weights. Fig. S3A shows the sequence identity, with At2g32580 highlighted in dark blue, and lighter blue indicating similar amino acids. ELMO1 is also conserved throughout the angiosperms (Fig. S3B). All of these genes are predicted to encode putative transmembrane Golgi proteins of similar molecular weight, and also of unknown function but with a predicted coiled-coil structure (DUF1068, TAIR; UniProt). At4g04460 is listed in Fig. S3A but can only be detected through National Institutes of Health (NIH) blast searches, and is not listed on any Arabidopsis database, is not annotated in the genome, and may therefore reflect a variant of one of the other ELMOs. We suggest that the ELMO1 homologues be given the name ELMO1-5; ELMO1 At2g32580, ELMO2 At1g05070, ELMO3 At4g04360, ELMO4 At4g30996, ELMO5 At2g24290. Surveys of expression databases show that ELMO1 is expressed in seeds, seedlings, roots, leaves, stems and all flower structures except for very low levels in pollen (http://aranet.sbs.ntu.edu.sg/responder.py?name=gene!ath!630). The ELMO family members have similar expression patterns, although some tissues vary in level. Co-expression analysis finds that the five ELMO family members are all co-expressed (http://genemania.org/search/arabidopsis-thaliana/At2g32580). The similar Golgi local amino acid conservation and expression patterns predict that the ELMO family members have similar or related functions, and are somehow involved in cell adhesion. To test this prediction, T-DNA alleles of each gene were obtained from the ABRC (elmo2, SALK205719C; elmo3, SALK20486C; elmo4, Salk 1398222), verified by PCR for the presence of the T-DNA, and then screened for plants homozygous for the allele. In addition, elmo1-1−/− was crossed with elmo2−/−, and an F2 plant identified that was homozygous for both alleles (elmo1-1−/− elmo2−/−). Dark-grown 4-day-old seedlings were stained with Ruthenium Red (Fig. 9A). As expected, WT hypocotyls did not stain, and elmo1-1−/− exhibited the expected hypocotyl cell curling and Ruthenium Red staining. Although elmo2−/− appeared to be similar to WT, elmo1-1−/− elmo2−/− seedlings had a dramatic cell adhesion phenotype, with frequent cell sloughing and strong Ruthenium Red staining. Confocal microscopy imaging of propidium iodide-stained dark-grown hypocotyls confirmed the observations of the Ruthenium Red images (Fig. 9B). The results suggest that ELMO1 and ELMO2 are partially redundant. No visible adhesion defects were seen in elmo3−/− plants and they appeared to be similar to WT, yet elmo4−/− had a dramatic cell adhesion phenotype, with Ruthenium Red staining and sloughing and curling cells. It remains to be determined what the effect of each of these alleles is on gene expression and the cell wall, but these initial results provide support for the conclusion that ELMO1 is important for cell adhesion, and that the family members may play a similar role. Further work is needed to fully characterize the family, their interactions, and their role in cell adhesion and plant growth.

Fig. 9.

Mutations in the ELMO family have adhesion defects. (A) Dark-grown hypocotyls of the indicated genotype were stained with Ruthenium Red. (B) Confocal microscopy imaging of propidium iodide-stained dark-grown hypocotyls of the indicated genotype. Scale bars: 1 mm (A); 50 µm (B).

DISCUSSION

To identify new mutants in cellular adhesion, a Ruthenium Red staining assay was used on a population of EMS-mutagenized Arabidopsis. One isolate elmo1 has a 3′ splice junction mutation in At2g32580 that altered mRNA levels and leads to cell curling, Ruthenium Red staining, shortened hypocotyls and some leaf cell disturbance. elmo1−/− mutants have a reduced level of mannose, but no other cell wall changes were detected. A 35Sp:At2g32580 and a GFP fusion of the encoded protein can complement elmo1-1, indicating that the adhesion defect is caused by a mutation of this gene. The plant-specific protein ELMO1 localizes to the Golgi and is predicted to be a 20 kDa coiled-coil protein in the Golgi lumen with one membrane anchor, and no known binding or catalytic domains.

The elmo1 mutant line shares phenotypic similarity with qua1-1, qua2-1 and frb-1 adhesion mutants. Dark-grown qua1-2 exhibits curling along the hypocotyl, gapping between cells, as well as shorter hypocotyls compared with the WT (Bouton et al., 2002). Shorter hypocotyls are also characteristic of the elmo1 phenotype, and confocal microscopy of elmo1-1 detects similar gapping between cells. The curling and sloughing of cells in the elmo1-1 mutant line also creates a lumpy texture along the hypocotyl, like the qua1-1 mutant, but far less pronounced. Like elmo1, cell protrusion also occurs in the cotyledons and leaves in qua1-1 mutants in addition to the hypocotyl, giving these tissues a rough and bubbling appearance (Bouton et al., 2002). The same is true of frb1-1 mutants, which show sloughing of the cells so severe that tissues appear as if they are crumbling (Neumetzler et al., 2012). Cell protrusion and sloughing at the hypocotyls also occurs in the qua2-1 mutant, along with reduced hypocotyl length and dwarfed growth in mature plants (Mouille et al., 2007). Thus, although the elmo1-1 phenotype shares phenotypic characteristics with these mutants, overall the effect of the mutation in elmo1 appears less severe than mutations in QUA1, QUA2 and FRB1.

The presence of ELMO-like genes could provide some functional redundancy for ELMO1, and may help to explain why the elmo1-1 mutant has a weak phenotype relative to other loss-of-function mutants such as frb1 and qua2 that affect adhesion. Indeed, the initial screen of T-DNA alleles in ELMO2, ELMO3 and ELMO4 indicates that ELMO1 and ELMO2 are partially redundant. As the elmo4 T-DNA allele alone has a strong adhesion phenotype, it is possible that the family lacks redundancy for ELMO4 function; however, further analysis of the strength of each allele, their effect on gene expression and on the cell wall is needed before further conclusions can be made.

The hypothesis that ELMO1 is not an enzymatic protein is supported by its size and predicted structure. At2g32580 encodes a protein 183 amino acids in length with a molecular weight of 19.967 kDa. Database searches fail to identify similarities to known enzyme classes of any kind, suggesting that ELMO1 is not involved directly in the enzymatic production of the cell wall. Although it was expected that elmo1 might reduce the pectin content of the cell wall, as both qua1 and qua2 adhesion mutants affect pectin, no reduction in pectin was detected relative to WT. Instead, the only change detected in elmo1 was a 2.6-fold reduction in mannose, but it is not clear that the mannose change is causative of the adhesion phenotype. Rather, the mannose change might be result of a secondary or indirect effect of elmo1-1. Additional analysis of cell wall carbohydrates and proteins will be essential to identify the causative agent of reduced adhesion.

Although certainly causing structural changes to the cell walls (Goubet et al., 2009; Miedes et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2016), a reduction in the hemicelluloses glucomannan and galactomannan have not been reported to lead to adhesion defects in angiosperms. In addition, changes to other hemicelluloses such as xyloglucan may change the structural integrity and spacing of the cell wall, but they do not lead to adhesion defects (Xiao et al., 2016). Moreover, elmo1-1 appears to have no changes in cell wall sugars that would suggest a reduction in hemicelluloses.

Mannose is also found as an essential component of both O-linked and N-linked glycosylated proteins and within glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors (Paulick and Bertozzi, 2008; Strasser, 2016). However, there appear to be no reports of O-linked mannose on proteins required for cell wall function, although this work suggests this is a possibility. AGPs are rich in arabinan and galactan O-linked polysaccharide side chains (Showalter and Basu, 2016), yet the elmo1-1 cell wall analysis detects no change in these sugars, indicating that AGPs are not affected. If elmo1-1 were to affect the core mannose-containing N-linked oligosaccharide added to many proteins in the ER, then one would expect a more pleiotropic and stronger phenotype and additional changes in the cell wall sugar profile. These are not seen, and moreover, ELMO1 is a Golgi and not an ER protein. Although a role for ELMO1 in the core N-linked glycosylation is less likely, elmo1 could have a more specific effect on the GPI anchor of numerous proteins including AGPs, and this in turn might affect cell adhesion. However, this too is less likely as the GPI anchor is synthesized and added in the ER, not near Golgi-localized ELMO1 (Strasser, 2016). A more thorough exploration of AGP structure and modification in elmo1 may address these possibilities. A mutation in a protein of unknown function, DUF246 (MSR1/2), has been noted to have reduced mannose, but it is not known if there are any cell adhesion phenotypes (Wang et al., 2013). Glycosylated sphingolipids (GIPCs) are also mannosylated, and a mutant of Golgi-localized GIPC mannosyltransferase (GMT1) leads to ectopically parting cells, a cell adhesion phenotype and reduced cellulose content (Fang et al., 2016). Each of these proteins need to be evaluated as potential candidates that might be altered in elmo1-1−/−.

There is, however, a strong possibility that the ELMO family is involved in a quality control mechanism for the export of cell wall-related proteins from the Golgi. Mutants of Golgi mannosidase activity, despite having no apparent phenotype alone, enhance the effects of cell wall mutants rsw2, cob1 and cesa6 (Liebminger et al., 2009). The mannosidase trimming is required for prevention of aggregation of folding intermediates, and is thought to be part of the quality control (Strasser, 2016). Perhaps ELMO1 provides an accessory protein or scaffold for these processes specific for cell wall proteins, possibly specific for those involved in adhesion. Scaffold proteins, which recruit and link proteins in a complex, facilitate the activity of enzymatic and signal transduction pathways (Lim et al., 2019; Pawson and Scott, 1997). There are examples of enzyme complexes in the biosynthetic pathways of carbohydrates in wheat (Tetlow et al., 2008), the likely formation of complexes in flavonoid synthesis, (Burbulis and Winkel-Shirley, 1999) and non-enzymatic proteins involved in starch metabolism in the chloroplast of A. thaliana (Lohmeier-Vogel et al., 2008). Non-enzymatic scaffold proteins might play an important role in the assembly of ECM carbohydrates that affect cellular adhesion, and ELMO1 may serve this function. The observation that esmd1, which suppresses multiple pectin-dependent adhesion defects such as qua2 and frb1, also suppresses elmo1, provides further evidence that ELMO1 is involved in the cell adhesion pathway. Analysis of the genetic interaction with other genes and the physical association of ELMO1 with other proteins will reveal the role that ELMO1, the ELMO family and mannose play in cell adhesion and cell wall assembly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana seeds were sterilized for 5 min in 95% ethanol and then 5 min in 10% bleach and rinsed twice with sterile dH2O. Seeds were then grown in liquid or agar containing Murashige and Skoog (MS) media (Sigma-Aldrich) (pH 5) with 2% agarose and 1% sucrose or planted directly onto soil. Following plating, seeds were exposed to cold (4°C) for 48 h, then exposed to light for 4 h at 20°C and grown at 20°C for 4 days in the dark. Seeds planted directly on soil were exposed to cold (4°C) for 48 h and grown with a cover on. For in-experiment comparisons, samples were grown at the same time in triplicate. Plants were imaged using a Nixon D3000 camera.

Mutant identification

To identify A. thaliana mutants with abnormal cellular adhesion, approximately 5000 M1 plants grown from EMS-mutagenized seeds were grown on soil (Rédei and Koncz, 1992). M2 generation seeds were then collected in 191 pools (each pool contained the progeny of approximately 20-30 plants) and 400 seeds from each pool were then grown for 4 days in the dark in liquid media after sterilization and stained with Ruthenium Red dye (Verger, 2014). Liquid media was removed and 3 ml of Ruthenium Red dye (Sigma Corporation, 0.5 mg/ml in dH2O) was applied to seedlings for 2 min in a 10 ml microtiter growth plate. After 2 min, seedlings were washed twice with 5 ml of dH2O. Hypocotyl staining was then observed under a dissecting microscope, and mutants were isolated and plated on MS agarose for 5 days in light conditions before being transferred to soil.

DNA extraction and PCR

Three-week old healthy green leaves from plants of interest were collected, frozen in liquid N2, and DNA was extracted as previously described (Kohorn et al., 2016). The indicated genes were PCR amplified according to the manufacturer's conditions using Titanium Taq DNA polymerase (Takara Bio) using the following primers: QUA2 F, 5′ CAGGGATCTTAGATTTATAGCAGCAAC-3′; QUA2R, 5′-GAAACCGAACCGGAAACATA-3′; ESMD1F, 5′-GGCGATAGGTTTCAATGATGAATTAAG-3′; ESMD1R, 5′-CCAAGTAAAGGGAAATATGAACATGATTATTG ATGATGTAC-3′. PCR samples were sequenced by Retrogen.

elmo1 F2 whole-genome sequencing

The pooled DNA preparations of 100 elmo1 individuals of an elmo1×WT Col0 F2 progeny were sequenced with Illumina genome sequencing technology performed by Novogene. Analysis of the elmo1 F2 allele frequencies was performed using the data file provided by Novogene and the programs artMAP (used to identify the allele frequencies) (Javorka et al., 2019) and IGV (used to visualize the genome sequence) (Thorvaldsdóttir et al., 2012).

Cell wall preparation

Four-day old dark-grown whole seedlings (roots, hypocotyls and cotyledons) were pooled and immersed in 96% ethanol and incubated at 80°C for 15 min twice, homogenized using a ball homogenizer for 20 min, centrifuged for 15 min at 20,000 g, and the supernatant was removed and the pellet re-suspended in acetone and centrifuged for 15 min at 20,000 g. The supernatant was then removed and the pellet was re-suspended in methanol:chloroform (2v:3v) and shaken overnight. Samples were then centrifuged for 15 min at 20,000 g and the supernatant was removed. The pellet was then re-suspended sequentially in 100%, 65%, 80%, and 100% ethanol. After each re-suspension samples were centrifuged at 20,000 g for 15 min and the supernatant was removed and the pellet of AIR dried under vacuum. This AIR was saponified overnight in 200 µL of 0.05 M NaOH and the samples were centrifuged at 4°C, 10,000 g for 10 min. Methylesterification of the pectin was quantified by measurement of the methanol content in the supernatant (Verger et al., 2016). The pellet was then washed twice with 70% ethanol (to remove residual NaOH) and twice with acetone at room temperature. The samples were not destarched. The residual pellet was air dried under vacuum and extracted with ammonium oxalate as previously described (Verger et al., 2016; Neumetzler et al., 2012). Ammonium oxalate-extracted uronic acid content was determined according to methods in Blumenkrantz and Asboe-Hansen (1973). The pellet was then washed twice with 70% ethanol (to remove residual ammonium oxalate) and twice with acetone at room temperature. Neutral monosaccharide composition analysis of the non-crystalline polysaccharide fraction and cellulose were performed on this ammonium oxalate extracted pellet (referred to as ammonium oxalate extracted AIR) after hydrolysis in 2.5 M trifluoroacetic acid for 1.5 h at 100°C as previously described (Harholt et al., 2006; Verger et al., 2016). The released monosaccharide was quantified using HPAEC-PAD chromatography as described in Harholt et al. (2006). Three biological replicates were analyzed.

Expression of ELMO

The coding region of At2g32580 was PCR amplified using the following primers: At2g32580FNco, 5′-CCATGGCGAAGCACACGG-3′; At2g32580Bamstop (no GFP tag), 5′-GGATCCTTAAGCAACCTCAGTGCCGC-3′; At2g32580Bamnostop, 5′-GGATCCGCAGCAACCTCAGTGCCGC-3′. The products were cloned into the NcoI BglII restriction enzyme sites of pCambia 1302. Plasmids were then transformed into Agrobacterium and the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998) was used for transformation of elmo1-1−/− A. thaliana Col0.

Confocal microscopy

Four-day-old dark grown seedlings were stained for 10 min with 10 µg/mL propidium iodide, and then washed once in dH2O. Hypocotyls were then visualized by confocal microscopy on a Leica SP8 microscope using a 10× objective, a 514 nm excitation laser and an emission spectrum of 617 nm. A z-stack was then created for the seedling using the Leica SP8 software. GFP and mCherry fusion proteins were detected by sequential scanning on the Leica SP8 at the following wavelengths: GFP, excitation 488 nm, emission 510-515 nm; mCherry, excitation 587 nm, emission 610 nm. The following Wave line Arabidopsis seed stocks expressing sub-cellular markers were obtained from ABRC as described in Geldner et al. (2009): ATMEMB12 At5g50440 Golgi, GOT1 At3g03180 Golgi, ATRABE1D At5g03520 Post Golgi/endosomal, VAMP711 At4g32150 late endosome/prevaculor compartment, AT-NLM1 NOD26-like intrinsic protein1 ER/plasma membrane. The pcambia1302ELMO1-GFP plasmid was transformed using Agrobacterium into each maker plant line as described above, and the T1 seeds were visualized using confocal microscopy.

RNA quantification

RNA from elmo1 M3 and WT plants was extracted from dark-grown hypocotyls using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit according to kit instructions (Qiagen). cDNA from 1 µg of RNA was synthesized using an Invitrogen Superscript III First Strand Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer's conditions. RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR green dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in an Applied Biosystems StepOne system as previously described (Kohorn et al., 2016). Biological triplicates were run for each sample and relative expression was calculated relative to an actin control. Analysis was carried out using the Applied Biosystems supplied software and prism. Primers used were: At2g32580FRT, 5′-GTGATCCAGAGGTGAACGAAGACAC-3′; At2g32580RRT, 5′-CCTCAGTGCCGCTTTTGGATTTAACAG-3′.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Stephane Verger and Julien Sechet for thoughtful discussions.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: B.D.K., G.M.; Methodology: B.D.K.; Software: B.D.K.; Validation: B.D.K.; Formal analysis: B.D.K.; Investigation: B.D.K., F.D.H.Z., J.D.-M., S.C., G.M., S.K.; Resources: B.D.K.; Data curation: B.D.K.; Writing - original draft: B.D.K.; Writing - review & editing: B.D.K., F.D.H.Z., G.M.; Visualization: B.D.K.; Supervision: B.D.K.; Project administration: B.D.K.; Funding acquisition: B.D.K.

Funding

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation grant IOS 1556057, and an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20GM103423. This work has also benefited from a French State grant from Labex Saclay Plant Sciences (ANR-10-LABX-0040-SPS, ANR-17-EUR-0007 and EUR SPS-GSR). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Data Availability

Sequencing data have been deposited in SRA under accession number PRJNA727485.

References

- Blumenkrantz, N. and Asboe-Hansen, G. (1973). New method for quantitative determination of uronic acids. Anal. Biochem. 54, 484-489. 10.1016/0003-2697(73)90377-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton, S., Leboeuf, E., Mouille, G., Leydecker, M. T., Talbotec, J., Granier, F., Lahaye, M., Höfte, H. and Truong, H. N. (2002). QUASIMODO1 encodes a putative membrane-bound glycosyltransferase required for normal pectin synthesis and cell adhesion in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14, 2577-2590. 10.1105/tpc.004259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbulis, I. E. and Winkel-Shirley, B. (1999). Interactions among enzymes of the Arabidopsis flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 12929-12934. 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S. J. and Bent, A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735-743. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher, F. B. and Braybrook, S. A. (2015). How to let go: pectin and plant cell adhesion. Frontiers in plant science 6, 523. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakakaki, G. (2015). Polysaccharide deposition during cytokinesis: challenges and future perspectives. Plant Sci 236, 177-184. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, J., Kirui, A., Huang, S., Wang, L., Barnes, W. J., Kiemle, S. N., Zheng, Y., Rui, Y., Ruan, M., Qi, S.et al. (2020). Mutations in the pectin methyltransferase QUASIMODO2 influence cellulose biosynthesis and wall integrity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 32, 3576-3597. 10.1105/tpc.20.00252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang, L., Ishikawa, T., Rennie, E. A., Murawska, G., Lao, J., Yan, J., Tsai, A. Y., Baidoo, E. E. K., Xu, J., Keasling, J. D.et al. (2016). Loss of inositol phosphorylceramide sphingolipid mannosylation induces plant immune responses and reduces cellulose content in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 28, 2991-3004. 10.1105/tpc.16.00186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldner, N., Dénervaud-Tendon, V., Hyman, D. L., Mayer, U., Stierhof, Y. D. and Chory, J. (2009). Rapid, combinatorial analysis of membrane compartments in intact plants with a multicolor marker set. Plant J. 59, 169-178. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03851.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendre, D., Oh, J., Boutté, Y., Best, J. G., Samuels, L., Nilsson, R., Uemura, T., Marchant, A., Bennett, M. J., Grebe, M.et al. (2011). Conserved Arbidopsis echidna protein mediated trans-golgi-network trafficking and cell elongation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 8048-8053. 10.1073/pnas.1018371108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendre, D., McFarlane, H. E., Johnson, E., Mouille, G., Sjodin, A., Oh, J., Levesque-Tremblay, G., Watanabe, Y., Samuels, L. and Bhalerao, R. P. (2013). Trans-Golgi network localized ECHIDNA/Ypt interacting protein complex is required for the secretion of cell wall polysaccharides in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 2633-2646. 10.1105/tpc.113.112482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goubet, F., Barton, C. J., Mortimer, J. C., Yu, X., Zhang, Z., Miles, G. P., Richens, J., Liepman, A. H., Seffen, K. and Dupree, P. (2009). Cell wall glucomannan in Arabidopsis is synthesised by CSLA glycosyltransferases, and influences the progression of embryogenesis. Plant J. 60, 527-538. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03977.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harholt, J., Jensen, J. K., Sørensen, S. O., Orfila, C., Pauly, M. and Scheller, H. V. (2006). ARABINAN DEFICIENT 1 is a putative arabinosyltransferase involved in biosynthesis of pectic arabinan in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 140, 49-58. 10.1104/pp.105.072744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harholt, J., Suttangkakul, A. and Vibe Scheller, H. (2010). Biosynthesis of pectin. Plant Physiol. 153, 384-395. 10.1104/pp.110.156588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javorka, P., Raxwal, V., Najvarek, J. and Riha, K. (2019). artMAP: a user-friendly tool for mapping EMS-induced mutations in Arabidopsis. Plant Direct 3, e00146. 10.1002/pld3.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson, K., Lathe, R. S., Kierzkiwski, D., Routier-Kierzkowska, A. L., Hamant, O. and Bhalerao, R. P. (2021). Mechanochemical feedback mediates tissue bending required for seedling emergence. Curr. Biol. 31, 1-11. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegstra, K. (2010). Plant cell walls. Plant Physiol. 154, 483-486. 10.1104/pp.110.161240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjellbom, P., Snogerup, L., Stohr, C., Reuzeau, C., McCabe, P. F. and Pennell, R. I. (1997). Oxidative cross-linking of plasma membrane arabinogalactan proteins. Plant J. 12, 1189-1196. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.12051189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohorn, B. D., Hoon, D., Minkoff, B. B., Sussman, M. R. and Kohorn, S. L. (2016). Rapid oligo-galacturonide induced changes in protein phosphorylation in Arabidopsis. Molecular & cellular proteomics: MCP 15, 1351-1359. 10.1074/mcp.M115.055368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupková, E., Immerzeel, P., Pauly, M. and Schmülling, T. (2007). The TUMOROUS SHOOT DEVELOPMENT2 gene of Arabidopsis encoding a putative methyltransferase is required for cell adhesion and coordinated plant development. Plant J. 50, 735-750. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leboeuf, E., Guillon, F., Thoiron, S. and Lahaye, M. (2005). Biochemical and immunohistochemical analysis of pectic polysaccharides in the cell walls of Arabidopsis mutant QUASIMODO 1 suspension-cultured cells: implications for cell adhesion. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 3171-3182. 10.1093/jxb/eri314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebminger, E., Huttner, S., Vavra, U., Fischl, R., Schoberer, J., Grass, J., Blaukopf, C., Seifert, G. J., Altmann, F. and Mach, L.et al. (2009). Class I alpha-mannosidases are required for N-glycan processing and root development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 21, 3850-3867. 10.1105/tpc.109.072363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S., Jung, G. A., Glover, D. J. and Clark, D. S. (2019). Enhanced enzyme activity through scaffolding on customizable self-assembling protein filaments. Small 15, e1805558. 10.1002/smll.201805558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmeier-Vogel, E. M., Kerk, D., Nimick, M., Wrobel, S., Vickerman, L., Muench, D. G. and Moorhead, G. B. (2008). Arabidopsis At5g39790 encodes a chloroplast-localized, carbohydrate-binding, coiled-coil domain-containing putative scaffold protein. BMC Plant Biol. 8, 120. 10.1186/1471-2229-8-120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Y., Li, H. Y., Shen, J., Wang, J. and Jiang, L. (2011). QUASIMODO 3 (QUA3) is a putative HG methyltransferase regulating cell wall biosynthesis in Arabidopsis suspension-cultured cells. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 5063-5078. 10.1093/jxb/err211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miart, F., Desprez, T., Biot, E., Morin, H., Belcram, K., Hofte, H., Gonneau, M. and Vernhettes, S. (2014). Spatio-temporal analysis of cellulose synthesis during cell plate formation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 77, 71-84. 10.1111/tpj.12362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miedes, E., Suslov, D., Vandenbussche, F., Kenobi, K., Ivakov, A., Van Der Straeten, D., Lorences, E. P., Mellerowicz, E. J., Verbelen, J. P. and Vissenberg, K. (2013). Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH) overexpression affects growth and cell wall mechanics in etiolated Arabidopsis hypocotyls. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 2481-2497. 10.1093/jxb/ert107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A. L., Attwood, T. K., Babbitt, P. C., Blum, M., Bork, P., Bridge, A., Brown, S. D., Chang, H., El-Gebali, S. and Fraser, M. I. (2019). InterPro in 2019: improving coverage, classification and access to protein sequence annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D351-D360. 10.1093/nar/gky1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohnen, D. (2008). Pectin structure and biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 266-277. 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouille, G., Ralet, M. C., Cavelier, C., Eland, C., Effroy, D., Hematy, K., McCartney, L., Truong, H. N., Gaudon, V. and Thibault, J. F.et al. (2007). HG synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana requires a golgi-localized protein with a putative methyltransferase domain. Plant J. 50, 605-614. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03086.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumetzler, L., Humphrey, T., Lumba, S., Snyder, S., Yeats, T. H., Usadel, B., Vasilevski, A., Patel, J., Rose, J. K. and Persson, S.et al. (2012). The FRIABLE1 gene product affects cell adhesion in Arabidopsis. PLoS One 7, e42914. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, H. T., Stevens, T. J., McFarlane, H. E., Vidal-Melgosa, S., Griss, J., Lawrence, N., Butler, R., Sousa, M. M. L., Salemi, M. and Willats, W. G. T.et al. (2019). Separating golgi proteins from cis to trans reveals underlying properties of cisternal localization. Plant Cell 31, 2010-2034. 10.1105/tpc.19.00081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulick, M. G. and Bertozzi, C. R. (2008). The glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor: a complex membrane-anchoring structure for proteins. Biochemistry 47, 6991-7000. 10.1021/bi8006324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, T. and Scott, J. D. (1997). Signaling through scaffold, anchoring, and adaptor proteins. Science 278, 2075-2080. 10.1126/science.278.5346.2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaucelle, A., Braybrook, S. A., Le Guillou, L., Bron, E., Kuhlemeier, C. and Hofte, H. (2011). Pectin-induced changes in cell wall mechanics underlie organ initiation in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 21, 1720-1726. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson, S., Caffall, K. H., Freshour, G., Hilley, M. T., Bauer, S., Poindexter, P., Hahn, M. G., Mohnen, D. and Somerville, C. (2007). The Arabidopsis irregular xylem8 mutant is deficient in glucuronoxylan and HG, which are essential for secondary cell wall integrity. Plant Cell 19, 237-255. 10.1105/tpc.106.047720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rédei, G. P. and Koncz, C. (1992). Classical mutagenesis. In Methods in Arabidopsis research (ed. Chua N.-H., Koncz C. and Schell J.), pp. 16-82. World Scientific, Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt, I., Stierhof, Y. D., Mayer, U., Richter, S., Schwarz, H., Schumacher, K. and Jurgens, G. (2007). Plant cytokinesis requires de novo secretory trafficking but not endocytosis. Curr. Biol. 17, 2047-2053. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, B. L., O'Neill, M. A. and Mohnen, D. (2001). Pectins: structure, biosynthesis, and oligogalacturonide-related signaling. Phytochemistry 57, 929-967. 10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00113-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, A. L., Giddings, T. H., Jr. and Staehelin, L. A. (1995). Cytokinesis in tobacco BY-2 and root tip cells: a new model of cell plate formation in higher plants. J. Cell Biol. 130, 1345-1357. 10.1083/jcb.130.6.1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sénéchal, F., Wattier, C., Rusterucci, C. and Pelloux, J. (2014). HG-modifying enzymes: structure, expression, and roles in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 5125-5160. 10.1093/jxb/eru272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevell, D. E., Kunkel, T. and Chua, N. H. (2000). Cell wall alterations in the arabidopsis emb30 mutant. Plant Cell 12, 2047-2060. 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showalter, A. M. and Basu, D. (2016). Extensin and arabinogalactan-protein biosynthesis: glycosyltransferases, research challenges, and biosensors. Frontiers in plant science 7, 814. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šola, K., Gilchrist, E. J., Ropartz, D., Wang, L., Feussner, I., Mansfield, S. D., Ralet, M. C. and Haughn, G. W. (2019). RUBY, a putative galactose oxidase, influences pectin properties and promotes cell-to-cell adhesion in the seed coat epidermis of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 31, 809-831. 10.1105/tpc.18.00954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staehelin, L. A. and Hepler, P. K. (1996). Cytokinesis in higher plants. Cell 84, 821-824. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81060-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser, R. (2016). Plant protein glycosylation. Glycobiology 26, 926-939. 10.1093/glycob/cww023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L., Eberhard, S., Pattathil, S., Warder, C., Glushka, J., Yuan, C., Hao, Z., Zhu, X., Avci, U. and Miller, J. S.et al. (2013). An Arabidopsis cell wall proteoglycan consists of pectin and arabinoxylan covalently linked to an arabinogalactan protein. Plant Cell 25, 270-287. 10.1105/tpc.112.107334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetlow, I. J., Beisel, K. G., Cameron, S., Makhmoudova, A., Liu, F., Bresolin, N. S., Wait, R., Morell, M. K. and Emes, M. J. (2008). Analysis of protein complexes in wheat amyloplasts reveals functional interactions among starch biosynthetic enzymes. Plant Physiol. 146, 1878-1891. 10.1104/pp.108.116244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorvaldsdóttir, H., Robinson, J. T. and Mesirov, J. P. (2012). Integrative genomics viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief. Bioinform. 14, 178-192. 10.1093/bib/bbs017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oostende-Triplet, C., Guillet, D., Triplet, T., Pandzic, E., Wiseman, P. W. and Geitmann, A. (2017). Vesicle dynamics during plant cell cytokinesis reveals distinct developmental phases. Plant Physiol. 174, 1544-1558. 10.1104/pp.17.00343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verger, S. (2014). Genetic and chemical genomic dissection of the cell adhesion mechanisms in plants. PhD thesis, Université Paris Sud, France. [Google Scholar]

- Verger, S., Chabout, S., Gineau, E. and Mouille, G. (2016). Cell adhesion in plants is under the control of putative O-fucosyltransferases. Development 143, 2536-2540. 10.1242/dev.132308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma, D. P. (2001). Cytokinesis and building of the cell plate in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 52, 751-784. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Mortimer, J. C., Davis, J., Dupree, P. and Keegstra, K. (2013). Identification of an additional protein involved in mannan biosynthesis. Plant J. 73, 105-117. 10.1111/tpj.12019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willats, W. G., McCartney, L., Mackie, W. and Knox, J. P. (2001). Pectin: cell biology and prospects for functional analysis. Plant Mol. Biol. 47, 9-27. 10.1023/A:1010662911148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, S. and Höfte, H. (2014). Growth control: a saga of cell walls, ROS, and peptide receptors. Plant Cell 26, 1848-1856. 10.1105/tpc.114.125518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormit, A. and Usadel, B. (2018). The multifaceted role of pectin methylesterase inhibitors (PMEIs). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 2878. 10.3390/ijms19102878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, C., Zhang, T., Zheng, Y., Cosgrove, D. J. and Anderson, C. T. (2016). Xyloglucan deficiency disrupts microtubule stability and cellulose biosynthesis in Arabidopsis, altering cell growth and morphogenesis. Plant Physiol. 170, 234-249. 10.1104/pp.15.01395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.