Abstract

A 23-year-old Korean female presented epigastric pain of two-months’ duration. She had a laparoscopic ovarian cyst excision 8 months previously. Clinical examination was normal. An abdominal computed tomogram (CT) demonstrated a 10-cm solid mass in the distal pancreas, with signs of splenic artery and vein occlusion, gastric and transverse colon invasion. Operative findings showed a mass involving distal pancreas, invasive to the posterior wall of the antrum of the stomach and transverse colon and 4th portion of the duodenum without lymph node involvement. The surgery consisted of a distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy and combined partial resection of the stomach, transverse colon and 4th portion of the duodenum. The immunohistochemistry and histopathological features were consistent with a confirmed diagnosis of intra-abdominal desmoid type fibromatosis (DTF). The prognosis of pancreatic DTF is not known and she showed no recurrence or distant metastasis during a 3 year follow-up. Herein we report a rare case with an isolated, sporadic, and non-trauma-related DTF, located at the pancreatic body and tail.

Keywords: Pancreatic desmoid type fibromatosis, Desmoid tumor, Aggressivefibromatosis

INTRODUCTION

Desmoid type fibromatosis (DTF), also known as a desmoid tumor, deep fibromatosis, or aggressive fibromatosis, is a rare neoplastic tumor arising from proliferation of mesenchymal stem cell progenitors.1 It is locally invasive but without metastatic potential, and is slow-growing.2 Although not metastatic, DTF tends to destroy surrounding tissues and organs and recurs frequently after radical resection. It can arise sporadically at any anatomical site throughout the body or be associated with familial adenomatous polyposis.3 DTF is categorized by location as extra-abdominal, abdominal wall, and intra-abdominal. Desmoid tumors account for 0.03% of all neoplasms and 3% of soft tissue tumors, and their annual incidence has been estimated to be 2-4 cases per million per year in the general people.4 Moreover, the incidence of sporadic intra-abdominal DTF is low (5%); fewer than 100 cases have been reported since the 1960s. Of these, intra-abdominal DTF of pancreatic origin is particularly rare, with only thirteen individual cases described in the English literature since the 1980s (Table 1).5-16 Herein we report a case with an isolated, sporadic, and non-trauma-related DTF, located at the pancreatic body and tail and invading the stomach, the transverse colon and the duodenum.

Table 1.

Review of pancreatic desmoid type fibromatosis (DTF)a

| Reference | Gender | Age (years) | Symptoms and signs | Lab findings | CT features | Tumor location | Size (cm) | Previous surgery | Surgery | Adjuvant treatment | Recurrence | Follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Roggli et al. (1980)5 | M | 0.3 | Tachypnea, fever, anorexia, weight loss | NA | Solid | Diffuse | NA | None | Biopsy | None | NA | DOD 7 days |

| 02 | Bruce et al. (1996)6 | M | 38 | Abdominal pain | NA | Solid | Tail | 5×4.5×2.1 | Partial pancreatectomy | Resection | NA | No | ANED 24 months |

| 03 | Sedivy et al. (2002)7 | F | 68 | Weight loss, nausea | Normal | Solid | Head | 1.5 | Pancreatic biopsy | Resection | NA | NA | NA |

| 04 | Nursal et al. (2003)8 | F | 25 | Epigastric pain | NA | Solid | Tail | 8.5×5.0 | None | Biopsy | Symptomatic | NA | NA |

| 05 | Nursal et al. (2003)8 | M | 39 | Epigastric pain | NA | Solid | Tail | 7.5×4.0 | None | Biopsy | Symptomatic | NA | NA |

| 06 | Pho et al. (2005)9 | M | 17 | Epigastric pain | NA | Cystic | Tail | 2.8×4.2 | None | Resection | Sulindac, tamoxifen, methotrexate, vinblastine | Yes | AWD 24 months |

| 07 | Weiss et al. (2006)10 | M | 63 | Epigastric pain, abdominal fullness | Normal | Solid | Tail | 6.5×5.3 | Partial pancreatectomy | Resection | None | No | ANED 9 months |

| 08 | Amiot et al. (2008)11 | F | 51 | Epigastric pain, weight loss | Normal | Cystic | Tail | 6 | None | Resection | None | No | ANED 12 months |

| 09 | Polistina et al. (2010)12 | M | 68 | None | Normal | Cystic | Tail | 5 | None | Resection | None | No | ANED 60 months |

| 10 | Jia et al. (2013)13 | M | 41 | Epigastric pain, weight loss | Normal | Cystic | Head | 1.9 | None | Resection | None | No | ANED 24 months |

| 11 | Xu et al. (2013)14 | M | 17 | Epigastric pain | Normal | Cystic solid | Body | 8.6 | None | Resection | None | No | ANED 20 months |

| 12 | Slowik-Moczydlowskaet al. (2015)15 | M | 13 | Left upper quadrant abdominal pain | Normal | Cystic | Tail | 10 | None | Resection | None | No | ANED 19 months |

| 13 | Wang and Wong (2016)16 | F | 57 | Epigastric pain, weight loss | Normal | Solid | Head | 10 | None | Resection | Cox-2 inhibitor | No | ANED 24 months |

| 14 | Present study (2017) | F | 22 | Epigastric pain | Normal | Solid | Body, Tail | 10 | Ovarian cystectomy | Resection | None | No | ANED 8 months |

aAll cases were sporadic except for one patient with complication FAP reported by Pho et al.9

CT, computed tomography; NA, not available; ANED, alive with no evidence of disease; AWD, alive with disease; DOD, dead of disease

CASE

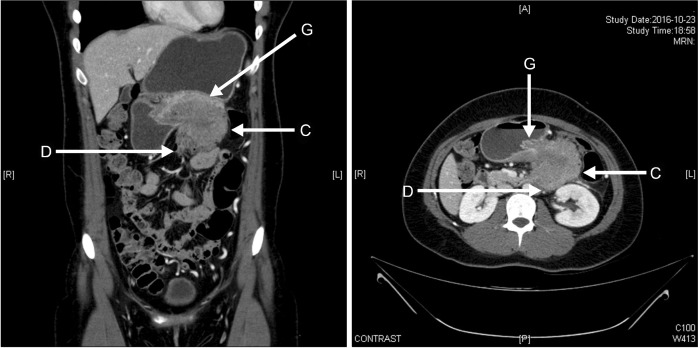

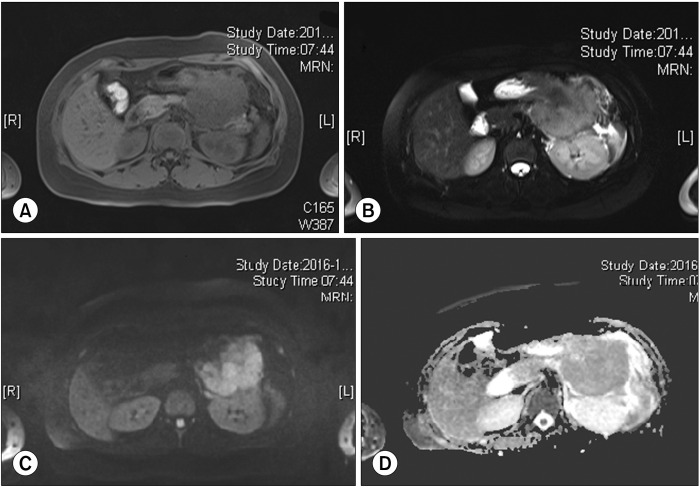

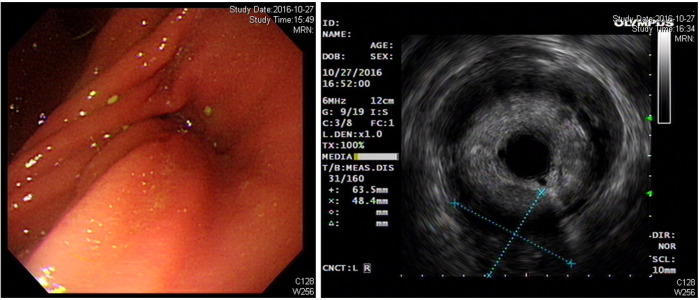

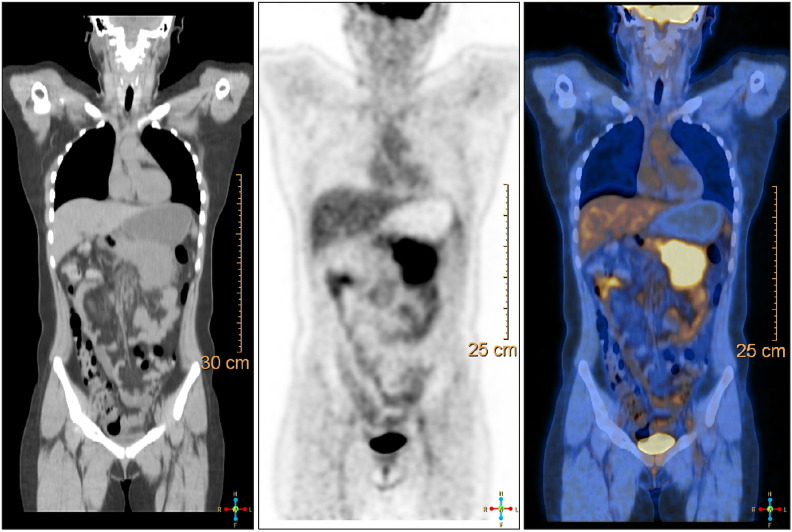

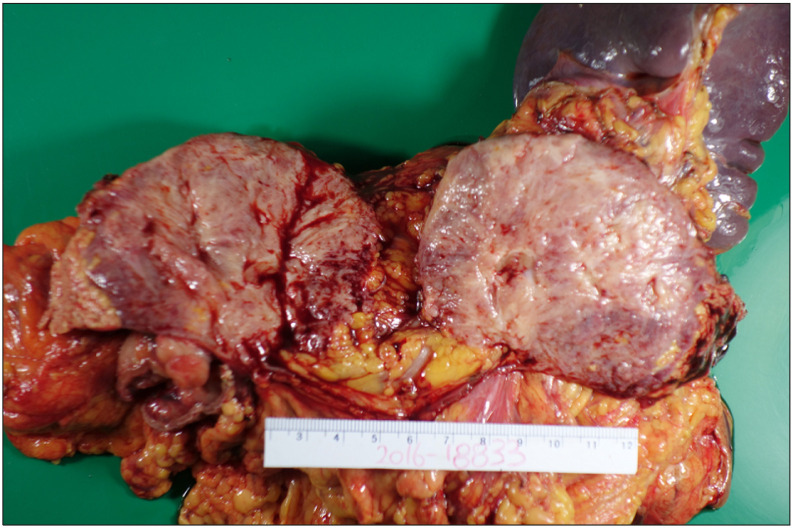

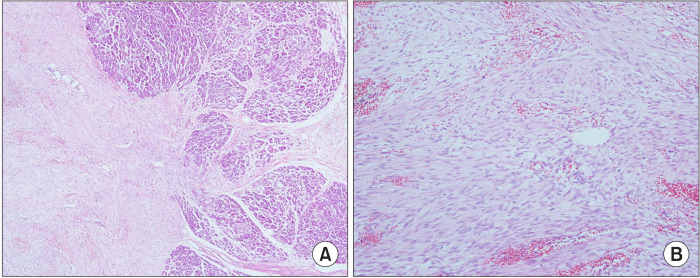

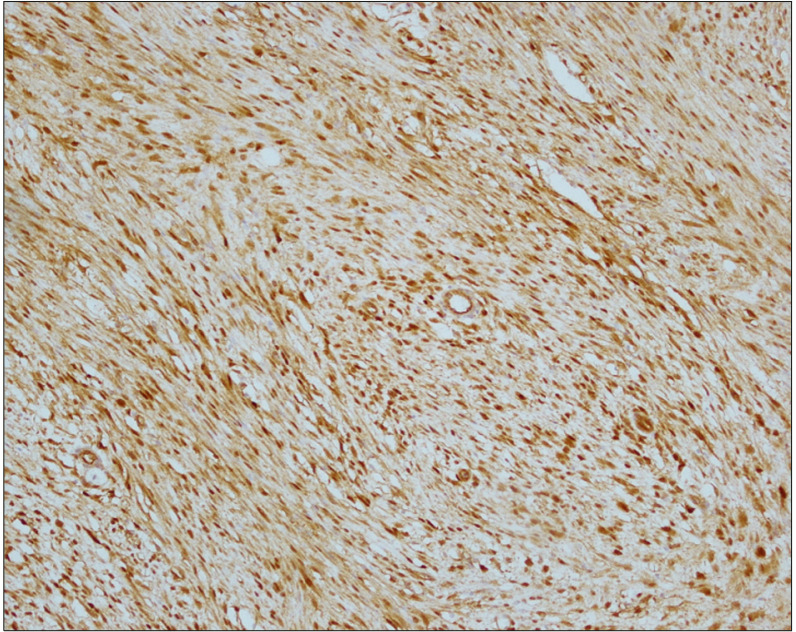

A 23-year-old Korean female presented to our surgical department with epigastric pain of two-months’ duration. Her past surgical history included laparoscopic ovarian cyst excision 8 months previously. No history of prior abdominal trauma was noted. There was no family history to suggest a genetic hereditary disease. Clinical examination was normal. The liver function test was normal except elevated serum amylase 250 U/L (reference range: 28 to 100 U/L) and lipase level 708 U/L (reference range: l3 to 60 U/L). The levels of serum tumor markers were within normal limits: carcinoembryonic antigen, 0.6 ng/ml (reference range: 0 to 5 ng/ml); carbohydrate antigen 19 to 9, 6.27 IU/ml (reference range: 0 to 37 IU/ml) (Table 2). An abdominal computed tomogram (CT) demonstrated a 10-cm solid mass in the distal pancreas, with signs of splenic artery and vein occlusion, gastric and transverse colon invasion (Fig. 1). The pancreatic mass was ill-delineated with no evidence of metastasis. On MRI scan, a huge lobulated contour mass was found in the body and tail of the pancreas, showing low signal intensity on T1- and slightly high T2-weighted images with diffusion restriction and delayed enhancement pattern (Fig. 2). On EUS a showed an huge soft tissue mass with no cystic portion but multiple echogenic foci located in the distal pancreas (Fig. 3). PET CT showed heterogeneous hypermetabolic lesion in left quadrant abdomen (Fig. 4). Operative findings showed a mass involving distal pancreas, invasive to the posterior wall of the antrum of the stomach and transverse colon and 4th portion of the duodenum without lymph node involvement. The surgery consisted of a distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy and combined partial resection of the stomach, transverse colon and 4th portion of the duodenum. On gross pathology the tumor appeared as a grayish, white, dense and firm mass, without necrosis or hemorrhage (Fig. 5). On pathologic microscopic examination, the surgical margins were negative for a tumor. Histological sections showed a large number of spindle-shaped cells, with a regular nuclear pattern within a background of massive collagen fibers. No marked cell death but mitosis 8/50 HPF was observed (Fig. 6). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the tumor cells were diffuse immune-positive for vimentin and β-catenin (Fig. 7), but immune-negative for smooth muscle actin, S-100, and CD34. The immunohistochemistry and histopathological features were consistent with a confirmed diagnosis of intra-abdominal DTF. The patient received no adjuvant therapy after surgery. She exhibited good health and complained of no discomfort. No local recurrence or distant metastasis in CT was found during a 3 year follow-up.

Table 2.

Laboratory finding

| Hgb (g/dl) | 14.2 (12-16) | Sodium (mEq/L) | 140 (135-145) |

| WBC (/μl) | 5,700 (4,000-105,000) | Potassium (mEq/L) | 3.5 (3.5-5.3) |

| PLT (/μl) | 237K (150K-450K) | Chloride (mEq/L) | 102 (98-110) |

| AST (U/L) | 39 (7-38) | CA 19-9 (U/ml) | 6.27 (0-37) |

| ALT (U/L) | 79 (4-43) | ||

| BUN (mg/dl) | 12 (8-20) | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) | ||

| Total protein (mg/dl) | 7.3 (6-8.1) | ||

| Albumin (mg/dl) | 4.7 (3.5-5.3) | ||

| Amylase (U/L) | 250 (28-100) | ||

| Lipase (U/L) | 708 (13-60) |

Fig. 1.

Abdominal computed to-mogram (CT) showed a 7.7-cm solid mass in the distal pancreas, with signs of splenic artery and vein occlusion, duodenum ‘D’, gastric ‘G’ and transverse colon invasion ‘C’.

Fig. 2.

A huge lobulated con-tour mass was found in the body and tail of the pancreas, showing low signal intensity on T1-weighted image (A) and slightly high T2-weighted image (B) with diffusion restriction (C) and delayed enhancement pattern (D).

Fig. 3.

Endoscopic ultrasono-gram shows a huge soft tissue mass with no cystic portion but multiple echogenic foci in the distal pancreas.

Fig. 4.

PET-CT showed heterogeneous hypermetabolic tumor in left upper abdomen.

Fig. 5.

Gross specimen of the pancreatic body solid mass measuring 10 cm in size.

Fig. 6.

H&E staining showed spindle cell mass in the pan-creatic gland (A: H&E ×40 mag-nification, B: H&E ×100 magni-fication).

Fig. 7.

Immunohistochemical staining showed in strong positive beta-catenin.

DISCUSSION

Pancreatic DTFs are extremely rare and encountered incidentally in surgical practice. To the best of our knowledge only thirteen previous cases of pancreatic DTFs have been reported within the last three decades in the English medical literature (Table 1).5-16 Of these cases, all occurred in middle-aged patients except for one infant.5 Six patients had cystic pancreatic tumors and one patient had concomitant FAP. Nine of the pancreatic DTFs were located in the pancreatic tail, three in the head, and one case was diffuse throughout the pancreas.

DTF etiology has not been well defined. A history of trauma to the site of the tumor, often surgical in nature, may be elicited in approximately 25% of cases.17,18 Because women are more prone to sporadic intra-abdominal DTF than men, (female-to-male ratio of 2:1 to 5:1), estrogen might have a pathogenetic role. However, for diagnosed pancreatic DTF in particular, the literature review and our report identified nine males and five females. FAP is frequently associated with intra-abdominal DTF, but only one pancreatic DTF patient was reported to have concomitant FAP in the current literature.9 A somatic mutation in the genes 3’-adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) or β-catenin (CTNNB1) is the most significant risk factor for intra-abdominal DTF in FAP patients.19,20

Previous abdominal surgery is said to initiate the proliferation of fibrous tissue and is therefore implicated in the occurrence and recurrence of intra-abdominal DTF. However, of the reported pancreatic DTF patients, only three had undergone previous abdominal surgery, one of whom developed a sporadic DTF at the pancreatic suture line,6 and another a DTF of the pancreatic stump following a distal pancreatectomy for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.10 Our case is sporadic and not associated with FAP but has the history of ovarian cystectomy previously and we do not assure whether the ovarian surgery develop pancreatic DTF.

The clinical presentation of most patients with DTF is usually asymptomatic and otherwise presents nonspecific abdominal pain. Our patient presented epigastric pain and had a mild elevation in amylase and lipase which suggest pancreatitis.

DTF is typically suspected on imaging studies, although a pathological specimen is required for definitive diagnosis. Computed tomography demonstrates a well-defined mass with variable enhancement pattern. The mass is typically iso-attenuating to hyper-attenuating to muscle on contrast-enhanced imaging.21 DTF on MRI typically returns low signal on T1-weighted sequences, with variable signal on T2-weighted sequences. EUS is very useful for visually defining the pancreatic tumor located in the pancreatic head, and to determine whether the major vessels and the duodenum are infiltrated by the tumor. Additionally, EUS allows fine needle aspiration biopsy for cytological examination of superficially located tumors.22,23

Differentiating DTF from other types of soft tissue neoplasms may be difficult based on histological analysis alone. Expression was negative for CD34, CD117, S-100 and desmin, which excluded a gastrointestinal stromal tumor, solitary fibrous tumor, schwannoma, leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma, respectively.24,25 Recent efforts in immunostaining of intranuclear β-catenin and the gene responsible for its mutation proved efficient in discriminating DTF from other benign and malignant fibroblastic and myofibroblastic lesions (Table 3).26

Table 3.

iagnosis and treatment

| Immunohistochemistry | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Mesenchymal cell (VIMENTIN) (+) | Watching and waiting |

| Marker for stromal cell CD117(−) CD34(−) | Radical resection: recurrence 19-77% |

| Neural cell S-100(−) | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) |

| Beta-catenin (+) | Hormonaltherapy non-steroidal benzothiophene (tamoxifen or raloxifen) Interferon Chemotherapy(vinbrastine, methotrexate, doxorubicin and dacarbazine) Imatinib |

Multimodal therapy has been reported for the treatment of intra-abdominal DTF, including pancreatic DTF (Table 3). The prognosis of pancreatic DTF is not known.

CONCLUSION

Sporadic pancreatic DTF is a rare nonmetastatic and locally invasive soft tissue tumor. Diagnosis is based on medical imaging and confirmed via immunohistochemistry to differentiate DTF from other uncommon soft tissue tumors originating from the pancreas. Radical resection is recommended as first-line treatment for pancreatic DTF. Long-term follow-up studies are required to establish the prognosis of pancreatic DTF.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: WYK. Writing - original draft: CGP, WYK. Writing - review & editing: CGP, YNL, WYK

REFERENCES

- 1.Wu C, Amini-Nik S, Nadesan P, Stanford WL, Alman BA. Correction: aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumor) is derived from mesenchymal progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6084. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gounder MM, Lefkowitz RA, Keohan ML, D'Adamo DR, Hameed M, Antonescu CR, et al. Activity of sorafenib against desmoid tumor/deep fibromatosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4082–4090. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher C, Thway K. Aggressive fibromatosis. Pathology. 2014;46:135–140. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Micke O, Seegenschmiedt MH German Cooperative Group on Radiotherapy for Benign Diseases, author. Radiation therapy for aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumors): results of a national Patterns of Care Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:882–891. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.07.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roggli VL, Kim HS, Hawkins E. Congenital generalized fibromatosis with visceral involvement. A case report. Cancer. 1980;45:954–960. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800301)45:5<954::AID-CNCR2820450520>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce JM, Bradley EL, 3rd, Satchidanand SK. A desmoid tumor of the pancreas. Sporadic intra-abdominal desmoids revisited. Int J Pancreatol. 1996;19:197–203. doi: 10.1007/BF02787368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sedivy R, Ba-Ssalamah A, Gnant M, Hammer J, Klöppel G. Intraductal papillary-mucinous adenoma associated with unusual focal fibromatosis: a "postoperative" stromal nodule. Virchows Arch. 2002;441:308–311. doi: 10.1007/s00428-002-0686-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nursal TZ, Abbasoglu O. Sporadic hereditary pancreatic desmoid tumor: a new entity? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:186–188. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200308000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pho LN, Coffin CM, Burt RW. Abdominal desmoid in familial adenomatous polyposis presenting as a pancreatic cystic lesion. Fam Cancer. 2005;4:135–138. doi: 10.1007/s10689-004-1923-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss ES, Burkart AL, Yeo CJ. Fibromatosis of the remnant pancreas after pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:679–688. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amiot A, Dokmak S, Sauvanet A, Vilgrain V, Bringuier PP, Scoazec JY, et al. Sporadic desmoid tumor. An exceptional cause of cystic pancreatic lesion. JOP. 2008;9:339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polistina F, Costantin G, D'Amore E, Ambrosino G. Sporadic, nontrauma-related, desmoid tumor of the pancreas: a rare disease-case report and literature review. Case Rep Med. 2010;2010:272760. doi: 10.1155/2010/272760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jia C, Tian B, Dai C, Wang X, Bu X, Xu F. Idiopathic desmoid-type fibromatosis of the pancreatic head: case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:103. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu B, Zhu LH, Wu JG, Wang XF, Matro E, Ni JJ. Pancreatic solid cystic desmoid tumor: case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8793–8798. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Słowik-Moczydłowska Ż, Rogulski R, Piotrowska A, Małdyk J, Kluge P, Kamiński A. Desmoid tumor of the pancreas: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:104. doi: 10.1186/s13256-015-0591-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang YC, Wong JU. Complete remission of pancreatic head desmoid tumor treated by COX-2 inhibitor-a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:190. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0944-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez R, Kemalyan N, Moseley HS, Dennis D, Vetto RM. Problems in diagnosis and management of desmoid tumors. Am J Surg. 1990;159:450–453. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(05)81243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKinnon JG, Neifeld JP, Kay S, Parker GA, Foster WC, Lawrence W., Jr Management of desmoid tumors. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;169:104–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joyce M, Mignanelli E, Church J. Ureteric obstruction in familial adenomatous polyposis-associated desmoid disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:327–332. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181c52894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venkat D, Levine E, Wise WE. Abdominal pain and colonic obstruction from an intra-abdominal desmoid tumor. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2010;6:662–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Einstein DM, Tagliabue JR, Desai RK. Abdominal desmoids: CT findings in 25 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:275–279. doi: 10.2214/ajr.157.2.1853806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Bree E, Keus R, Melissas J, Tsiftsis D, van Coevorden F. Desmoid tumors: need for an individualized approach. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:525–535. doi: 10.1586/era.09.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lips DJ, Barker N, Clevers H, Hennipman A. The role of APC and beta-catenin in the aetiology of aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumors) Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimada S, Ishizawa T, Ishizawa K, Matsumura T, Hasegawa T, Hirose T. The value of MDM2 and CDK4 amplification levels using real-time polymerase chain reaction for the differential diagnosis of liposarcomas and their histologic mimickers. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1123–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1466–1478. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1466-GSTROM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhattacharya B, Dilworth HP, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Ricci F, Weber K, Furlong MA, et al. Nuclear beta-catenin expression distinguishes deep fibromatosis from other benign and malignant fibroblastic and myofibroblastic lesions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:653–659. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000157938.95785.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]