Abstract

Background:

Over a third of preadolescent children are with overweight or obesity. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends pediatric providers help families make changes in eating and activity to improve body mass index (BMI). However, implementation is challenging given limited time and referral sources, and family burden to access in-person weight management programs.

Purpose:

To describe the design of a National Heart Blood and Lung Institute sponsored cluster randomized controlled pediatric-based trial evaluating the effectiveness of the Fitline pediatric practice-based referral program to reduce BMI and improve diet and physical activity in children with overweight or obesity. Comparison will be made between brief provider intervention plus referral to (1) eight weekly nutritionist-delivered coaching calls with workbook to help families make AAP-recommended lifestyle changes (Fitline-Coaching), vs. (2) the same workbook in eight mailings without coaching (Fitline-Workbook).

Methods:

Twenty practices are pair-matched and randomized to one of the two conditions; 494 parents and their children ages 8-12 with a BMI of ≥85th percentile are being recruited. The primary outcome is child BMI; secondary outcomes are child’s diet and physical activity at baseline and 6- and 12-months post-baseline. Cost-effectiveness of the two interventions also will be examined.

Conclusion:

This is the first randomized controlled trial to examine use of a centrally located telephonic coaching service to support families of children with overweight and obesity in making AAP-recommended lifestyle changes. If effective, the Fitline program will provide an innovative model for widespread dissemination, setting new standards for weight management care in pediatric practice.

Keywords: Overweight, Obesity, Children, Coaching, Pediatric Practice, Group Randomized Controlled Trial

1. Introduction

The prevalence of childhood obesity has tripled in the U.S. over the past three decades, with 35.5% of preadolescent children now with overweight or obesity.1 Childhood obesity carries a 16-fold risk of severe obesity in adulthood2 and is associated with an increased risk of chronic disease and disability in adulthood.3 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends a staged approach to the management of pediatric overweight and obesity, starting with Stage 1, Prevention Plus, which encourages patients and their families to improve lifestyle choices related to eating and activity to improve body mass index (BMI) status.4 Most pediatric practices, however, have difficulty implementing these guidelines due to limited time and access to weight loss experts to whom they can refer their patients.

Effective, accessible weight management treatment approaches therefore are needed in the pediatric primary care setting. Primary care-based interventions like Let’s Go 5-2-1-0 that train providers and staff to use healthy messaging and healthy habits screening tools have been found to improve provider’s self-efficacy in addressing weight concerns and counseling about patient nutrition and physical activity.5,6 However, these interventions are not widely used in clinical practice due to provider time constraints and belief that their counseling would be ineffective in changing parents’ and children’s behaviors.7-11 The overwhelming majority of pediatric patients with overweight and obesity do not get referred from their provider to a registered dietitian,12 likely due to limited resources. A survey with 600 pediatric care providers found only 20% of practices had a pediatric dietitian, and half lacked any referral sources for pediatric weight management.11

Given pediatricians have limited time to perform weight counseling13 and half lack any referral sources,14 the AAP identified referral centers as an essential part of a comprehensive plan for the treatment of pediatric obesity.4 Such centers offer centralized resources to provide families with nutrition, activity, and weight management counseling.15 However, many families are unable to utilize these resources due to the burden of attending in-person weight loss programs, including distance to programs, and difficulties with transportation, cost, and coordination of family schedules. This is particularly true for children of low-income families who have the least access to care and are at the highest risk of obesity.14,16,17

Addressing this gap by offering a low-cost, easily-accessible parent-focused telephone-based resource could reduce the burden of childhood obesity in the clinical sector. There is a precedent for parent coaching for pediatric weight management, with studies concurring that parent-only interventions are equal to and often more successful than parent/child interventions and less costly.18,19,20 Studies have shown that telephone coaching is equal to in-person visits in maintaining childhood weight loss, however primary BMI reductions have not been closely studied.21 In addition, one trial found that phone-based coaching of approximately 15-20 minutes duration every other month for one year with families of children experiencing obesity recruited from the pediatric practice improves childhood BMI.22 However, it has yet to be determined whether a more frequent duration of calls, such as weekly phone coaching, over a shorter period of time is effective in producing long-lasting change. The Fitline pediatric practice-based referral program consists of brief provider intervention plus referral to eight weekly nutritionist-delivered coaching calls to help families make AAP-recommended lifestyle changes. This gives providers an easily-accessed referral resource, trained nutritionists in a centralized call center, to coach parents in improving their child’s weight-related behaviors.

We previously conducted a nonrandomized intervention pilot study of the Fitline program with contemporaneous control (ClinicalTrials.gov ID# NCT02085434) and found significant reductions in BMI and improvements in weight-related behaviors.23 Forty parents and their children ages 8-12 with BMI ≥85th percentile were recruited from an academic pediatric practice serving a multi-ethnic population; all 40 completed follow-up assessments (100% retention). Children were an average age of 9.6 years (SD 1.4), 46% were female, mean BMI was 27.2 (SD 3.4), and were predominantly low income (insured by MassHealth/Medicaid) and represented the diverse racial/ethnic mix of Central Massachusetts: 25% Hispanic, 12.5% Black, 47.5% White, and 15% Multiracial. Mean change in BMI from baseline to 3-month follow-up was −0.45 BMI units (SD 0.99; t-test −2.86, p=0.007) for the FITLINE group, 0.35 BMI units (SD 0.96; t-test 2.42, p=0.02) for the control group. The two groups significantly differed in change in BMI (0.85, t value 3.59, p<0.0006); children in the FITLINE condition were 0.85 BMI units lower than children in the control condition, equivalent to about an 8-pound difference over 3 months. Significant improvements in many dietary and sedentary behaviors also were noted, including reductions in eating a fast food or restaurant meal (p=0.002) or desserts (p=0.036), drinking fruit juice (p=0.004) and sweetened beverages (p=0.030), and use of computer and video games; and increases in eating 5 fruit and vegetables (p=0.002) (trend toward more days being physically active for at least 60 minutes).

2. Study aims

The primary aim of this five-year cluster randomized controlled pediatric practice-based trial is to examine the effectiveness of two practice-based interventions on reducing BMI among 8-12 year old children with overweight or obesity. Twenty pediatric primary care practices are randomized to either the Fitline-Coaching (N=10) or the Fitline-Workbook condition (N=10). Four hundred and ninety four parents and their children ages 8-12 with a body mass index (BMI) of ≥85th percentile (with overweight or obesity) are being enrolled from the practices to achieve N=400 families at 12-month follow-up. Assessments are completed at baseline and 6- and 12-months post-baseline. Aim 1 hypothesis: Children in the Fitline-Coaching group will have greater reductions in BMI at 6-month follow-up than children in the Fitline-Workbook group, and these between-group differences in reductions will be maintained at 12-month follow-up.

The second aim of this study is to determine the effectiveness of the Fitline-Coaching program in improving the child’s diet and physical activity (PA) behaviors. Aim 2 hypothesis: Children in the Fitline-Coaching group compared to the Fitline-Workbook will have greater improvements in intake of calories, sugar-sweetened beverages, saturated fats and fruit and vegetables and physical activity at 6-month follow-up, and these changes will be maintained over time (12-month follow-up).

The third aim is to explore possible mechanisms of the effect of the Fitline-Coaching program on BMI, diet, and physical activity. Aim 3 hypothesis: the effect of the Fitline-Coaching program will be explained through its impact on parent and child Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) constructs, which in turn impact child weight-related behavior changes and BMI.

The fourth aim is to estimate the cost-effectiveness of the Fitline-Coaching program compared with Fitline-Workbook in terms of cost per change in quality adjusted life-years (QALYs) and per reduction in the child’s BMI.

3. Study design and methods

3.1. Overview

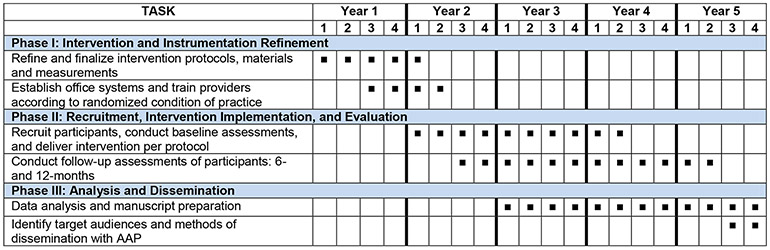

This is a five-year, cluster-randomized controlled pediatric practice-based trial with practices as the unit of randomization. We compare the effectiveness of two practice-based interventions on reducing BMI and improving diet and physical activity among children with overweight and obesity seen in pediatric practice. The first condition, Fitline-Coaching, consists of a pediatric practice-based component based on the Let’s Go 5-2-1-0 program5,6 plus Fitline phone-delivered coaching and workbook. The second condition, Fitline-Workbook, consists of the same practice-based component, but only the family workbook mailed over 8 weeks, with no referral to Fitline coaching. Children ages 8-12 with a BMI of ≥ 85th percentile (with overweight or obesity) and their parent are recruited from 20 pediatric primary care practices to achieve N=400 at 12-month follow-up. The 20 practices are pair-matched on size and percent low income (enrolled in MassHealth/Medicaid), and within each matched pair randomly allocated to either the Fitline-Coaching (N=10) or the Fitline-Workbook condition (N=10). Assessments are completed at baseline and 6- and 12-months post-baseline. The proposed project involves three phases (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1.

Study Timeline

3.2. Participating Pediatric Practices

This study is taking place in 20 pediatric primary care practices in Central Massachusetts. The practices have on average 4 attending pediatricians, with a range of 1 to 9. There are on average 1,743 8-12 year old children per practice across the 20 practices, ranging from 496 to 7,000 children All sites use electronic medical record software applications. All sites care for children from diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. Practices were selected to represent a wide variety of patients and their families to ensure we are testing the program in representative pediatric primary care settings. Practices were matched based on size and percent of patients enrolled in Medicaid. The study team did not have an established working relationship with the majority of these clinics. The study pediatrician knew one or more clinicians in a few of the pediatric practices. The study pediatrician met with each practice to introduce the study and establish themselves as a contact for possible issues and concerns.

3.2.1. Randomization

Randomization.

Pairs of clinics were matched based jointly on number of age-appropriate patients and percent of patients enrolled in Medicaid; within each pair, one clinic was randomly assigned to Fitline-Coaching and the other to Fitline-Workbook using a randomization based on random numbers generated in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) by the study statistician.

3.3. Participant Recruitment, Enrollment, and Retention

Inclusion Criteria: Eligible dyads must include: (1) child ages 8-12 years, (2) child BMI ≥ 85th percentile for age/sex, (3) participating parent/guardian and child English speaking, and (4) referred by the child’s primary care provider. If more than one child in a family is eligible, the oldest child will be invited to participate in order to avoid within-family clustering. Exclusion Criteria: Individuals will be excluded from participation if they: (1) are planning to move out of the area during the period of study participation to allow for the completion of follow up assessments, (2) medical condition that precludes adherence to AAP dietary and physical activity recommendations on which the intervention is based, (3) genetic (e.g., Prader Willi Syndrome, Leptin deficiency) or endocrine (Hypothyroidism, Cushing’s Syndrome) causes of obesity as these conditions make weight gain less likely to be modified by the lifestyle changes recommended by the AAP, (4) child prescribed medications associated with weight gain which would preclude the child from being able to reduce their BMI through purely lifestyle changes, (5) child on psychiatric medications as these are often associated with weight gain in children, or (6) morbidly obese (≥300 pounds) as weight is less likely to be modifiable by lifestyle changes.

The 8 to 12 age range was selected for a number of reasons: (1) it is the most common age range used in the majority of intervention trials of children with overweight and obesity, (2) it is the age range for which a parent-focused intervention such as Fitline is most appropriate, given the parent still has significant influence over the lifestyle choices of the child, and (3) age 8 has been shown to be a critical marker of the beginning of risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus.24

Recruitment and Informed Consent.

Potentially eligible children (8-12 years old, with overweight or obesity per medical record from their most recent visit) scheduled for a well-child clinic visit are identified through the practice’s office scheduling and electronic medical record system (e.g., Allscripts/Epic). During the clinic visit, the pediatric provider gives the family a one-page description of the study and, if the family indicates interest, returns the form to the study Project Director. Research staff mail the family the informed consent (parent) and assent (child) forms, contact them by phone to explain the study, and describe the parent and child’s potential role using a standardized information sheet. The confidentiality of all collected information is emphasized, and it is explained that the child’s care in the pediatric practice will not be affected by whether or not they participate in the study. The parent and child are provided the opportunity to have questions answered by the research staff. If the family is interested, parental consent and child assent is requested and provided both verbally during the call and by signing the consent (parent) and assent (child) forms. Research staff schedule a baseline study visit to collect anthropometric data from both the parent and the child and determine final eligibility of the child. Enrollment is staggered across study sites to make assessments and Fitline coaching feasible.

The following strategies are used to enhance recruitment based on pilot work and recommendations from Levickis and colleagues:25 (1) recruit and intervene during well visits with the child’s primary provider when review of the child’s growth is part of the visit; (2) provide a simple explanation of study time commitments and expectations; (3) emphasize the value of enhancing healthy diet and physical activity even in children just above the 85th percentile and/or already engaging in positive behaviors; (4) train providers on patient-centered language to address lack of parent motivation to increase provider self-efficacy in addressing weight; and (5) highlight how the Fitline coaches help parents to address their child’s weight related behaviors in a positive way to reduce potential negative impact on the child.

Retention.

We expect to retain 85% of families at 12-month follow-up (n=400). We have achieved outstanding retention rates in our prior pediatric trials.26-28 To maximize retention, we collect phone numbers and best times to reach parents. Tracking procedures are implemented for those not completing a study assessment. Parents and children each receive a gift card upon completion of assessments ($25 at baseline, $40 at 6-month, $50 at 12-month follow-up). This incentive schedule is consistent with that provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Healthy Communities Study.29

All procedures were reviewed, refined and approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board.

3.4. Description of Study Arms

3.4.1. Pediatric Practice plus Coaching (Fitline-Coaching) Condition

The Fitline-Coaching condition includes two components: a pediatric practice-based component and a parent support component.

Pediatric Practice-based Component.

The practice component is based on the Let’s Go 5-2-1-0 intervention 5,6 that provides tools for clinical decision support and counseling for the management of overweight in pediatric primary care practice. This program has been demonstrated to increase assessment of BMI/BMI percentile for age and gender and weight classification and improve parent-reported rates of provider counseling and provider knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy and practice. Implementation involves: (1) identifying a physician champion in each office, (2) establishing the optimal office flow and training in the 5-2-1-0 protocol, and (3) establishing sustained implementation of the practice-based component. Each of these implementation steps have been established in the study practices.

The practice-based component involves establishing systems to: (1) assess BMI percentile for age and gender in all children, (2) provide the Healthy Habits Questionnaire which briefly assesses diet, physical activity and lifestyle (regardless of weight status) to all families seeing a provider for a well visit, and (3) prompt pediatric providers to intervene and proactively refer interested parents of children with overweight and obesity (BMI ≥85th percentile for age and gender) ages 8-12 to the Fitline coaching program. Providers are prompted via provision of the completed Healthy Habits Questionnaire, provider algorithm (based on the AAR model – Ask, Advise, Refer),30 and brief written description of the Fitline coaching program (for families of children with overweight and obesity ages 8-12 only). The brief provider intervention involves the following AAR steps:

Ask the parent his/her thoughts on their child’s weight and weight related behaviors in a non-judgmental, supportive manner, reviewing the Healthy Habits Questionnaire completed by families.

Advise the parent to make key behavior changes recommended by the AAP and consistent with the Let’s Go 5-2-1-0 model, including family lifestyle and dietary changes (5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day, 0 sweetened beverages), increasing the child’s physical activity to at least 1 hour/day, and decreasing screen time to less than 2 hours/day. Ask if the parent is interested in making these changes. If not, let the parent know about available resources if they become interested.

Refer interested parents to the Fitline call center staffed by Fitline nutritionists and research staff. For parents in the Fitline-Coaching condition, the provider briefly introduces the coaching program as a telephone-based program with coaching by a nutritionist to guide parents in helping their child eat healthy and be physically active. All referrals are made using the practice’s referral process (e.g., sending a referral through the electronic medical record system, which is then forwarded to the Fitline call center). Once a referral is received by the Fitline call center, parents in the Fitline-Coaching condition are contacted to schedule the 8 coaching calls and sent the workbook. Referring providers receive a written summary from the Fitline nutritionist of the family’s progress within 2 weeks of program completion, allowing them to determine if the Stage 1, Prevention Plus intervention was enough to assist the family in maintaining improvements or refer for more intensive intervention if needed.

Pediatric providers are trained by the principal investigator and study pediatrician in a 45 minute in-clinic group training consisting of a review of the AAP recommendations, demonstration of the AAR intervention, and overview of the Fitline program. The AAR provider intervention is scripted and is included on the referral sheet provided to the clinicians for each potentially eligible child. In addition, the self-identified physician champion for each practice and their office manager met with study staff to discuss their roles and were provided with contact information for the study pediatrician and study staff and invited to reach out with any questions or concerns they had throughout the study.

Parent Support Component.

Parents are provided the following sources of support in making health behavior changes with their child. Except for the family workbook, which is provided to families in both conditions, the following support components are unique to Fitline-Coaching condition. This support component was pilot tested and modified based on parent feedback.

1. Fitline telephone coaching by centralized nutritionists

The eight weekly 30-minute Fitline calls provide personalized behavioral coaching to guide parents in improving their child’s weight-related behaviors through targeted lifestyle changes recommended by the AAP for Stage 1, Prevention Plus4 (see Table 3.4.1.a. for the Fitline Coaching Session Protocol including session topics, targeted behaviors per AAP guidelines, and type of behavior targeted (lifestyle, eating behavior, physical activity, or media/screen time). Calls are scheduled at a time convenient for the parent, including nights and weekends, with one nutritionist assigned to a family for the duration of the study calls for consistency. Fitline coaches use a structured protocol for each of the eight sessions that guides them in tailoring to the family’s unique situation throughout:

Table 3.4.1.a.

Fitline Coaching Session Protocol

| Fitline Session | Targeted Obesity-Related Behaviors per AAP Guidelines for Each Session |

Behavior Type Targeted (Lifestyle, Eating Behavior, Physical Activity, Media/Screen Time) |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1: Initial Assessment; SMART Goal | Involve the whole family in lifestyle changes Help families tailor behavior recommendations to their cultural values |

Lifestyle |

| Session 2: Healthy Foods for Families | Consume ≥ 5 servings of fruits and vegetables every day | Eating behavior |

| Session 3: Reducing Sugar-Sweetened Beverages; Parenting for Self-Regulation of Eating | Minimize sugar-sweetened beverages, such as soda, sports drinks, and punches. Ideally, these beverages will be eliminated from the child’s diet. | Eating behavior |

| Allow the child to self-regulate his or her meals and avoid overly restrictive feeding behaviors. | Lifestyle | |

| Session 4: Active Living | Be physically active ≥ 1 hour each day | Physical activity |

| Sessions 5: Family Meals and Eating Out/Take Out | Prepare more meals at home rather than purchasing restaurant food Eat at the table as a family at least 5 or 6 times per week | Lifestyle Eating behavior |

| Session 6: Breakfast Every Day; Healthy Snacks; Avoid Skipping Meals | Consume a healthy breakfast every day | Eating behavior |

| Session 7: Electronics in the Bedroom; Sleep; Sedentary Behavior | Decrease television viewing and other forms of screen time to ≤ 2 hours per day. To assist with this change, the television should be removed from the room where the child sleeps. | Media/screen time |

| Session 8: Keeping it Going | Review progress made/issues resolved and remaining, and next steps including reaching out to the pediatrician for ongoing support for lifestyle changes | Lifestyle |

Check-in: Each session begins with a check-in about progress made on the prior week’s goals (except the first session). This includes encouraging any efforts made, discussing challenges encountered, and reviewing how the goals were discussed with their child in order to help coach the parent in using a more authoritative parenting style. An authoritative parenting style, high parental involvement/high responsiveness to the child in which the parent sets appropriate limits in the context of a warm and nurturing environment, has been associated with positive health outcomes in children including greater consumption of fruits and vegetables, increased self-esteem, and lower BMI.

Introduction of the day’s topic: The coach briefly presents the topics to be discussed and, if more than one topic is to be covered, invites the parent to select which topic s/he would like to start with. If a parent had commented on the topic in the past, the coach is prompted to note this in their introduction to enhance relevance of the topic to the parent. For example, if the topic is eating a daily breakfast and this had been raised as an issue before, noting: “I recall you mentioned that it’s a struggle for you to get (child’s name) to eat breakfast. I think you’ll find some helpful tips for you to try out.”

- Topic: For each topic in a session, the coach covers the following:

- Assess – the coach asks open-ended questions about the child’s current status on the topic. For example, for the topic of reducing sugar-sweetened beverages, the coach asks: “What does (child’s name) typically drink? At school? At meals? Between meals?”

- Rationale – a very brief rationale is provided to highlight the importance of the topic. For example, for the topic of eating 5 or more fruits and vegetables a day, the rationale is provided: “The American Academy of Pediatrics encourages families to work towards eating 5 or more servings of fruit and vegetables a day. The reason for this is that fruits and vegetables are low in calories and high in fiber and other nutrients. Fiber is filling and helps with reducing hunger.”

- Problem-solve/Parenting tips – the coach asks the parent about strategies they have already implemented and ideas they have for doing so now. The coach then refers to the family workbook for tips provided and asks which tips or ideas might work well for the family, for example, “Which of the strategies in the workbook would you like to try with (child’s name)?”

- Assist parent in setting new goals – the coach asks the parent for the goals they would like to work on in the coming week

Summarize goals: The coach summarizes the parents’ stated goals for the coming week and has the parent write down their goals in their workbook, ensuring it is a SMART goal (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time-bound)

Arrange follow-up call

The Fitline coaching protocol is patient/family-centered, as recommended by the AAP for families of diverse cultures and financial situations. This means that the nutritionist asks open-ended questions, carefully assesses the child’s current behavior or family situation, and provides recommendations and resources adapted to the unique needs, culture, socioeconomic status, and lifestyle of each family. The protocol is designed to be appropriate for families from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, including low-income families, working with families to identify and problem-solve barriers to healthy eating and physical activity unique to the socioeconomic status, culture and lifestyle of each family. This includes tips on buying and preparing healthy foods and meals on a budget and finding low-cost opportunities for physical activity in their community.

The Fitline coaching is being conducted by phone. Our intervention was carefully designed to be accessible to and appropriate for families from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, including low-income families with limited resources. In our preliminary work, families indicated coaching by telephone to be the most convenient and easily-accessible venue for them. Of 114 Boston area parents surveyed, only a very small number of parents reported a preference for a computer-based service (n=7, 6%) or in-person counseling (n=7, 6%) over a telephone-based service.31 In addition, research has shown that there is a significant digital inequality, with low-income households having lower rates of in-home Internet connectivity compared with higher-income groups, and that 80% of those who lack Internet access at home cite Internet costs as a key reason.32 Even with the narrowing of some aspects of the digital divide, there are wide gaps in digital access. For example, 94% of higher income families ($100K+) report having home broadband, compared to only half (54%) of lower income families (<$30K).33 Given our target population and desire to be accessible to low-income families, we made a conscious decision to deliver our intervention via telephone, and decided to keep the coaching intervention consistent and deliver the intervention exclusively by telephone. There have been a number of studies showing patient preference for telephone counseling and a recent systematic review of psychosocial interventions for adult cancer patients found improved Quality of Life of telephone counseling compared with other modalities.34

2. Fitline family workbook

The family workbook contains information, tips, and practical strategies for families to support their implementing the AAP-recommended lifestyle changes. The workbook is organized by session, covering the topics for each of the eight coaching sessions (see Table 3.4.1.a.). The workbook begins with a “My Family Goal Sheet” for families to document their goals for each of the 8 sessions as they progress through the workbook. It then provides a section on each topic covered, including: (1) information about that topic (e.g., rationale for eating a healthy breakfast, facts about sugar-sweetened beverages, why having healthy snacks available is important, research on the impact of TV and screen time), (2) tips and strategies for implementing each AAP recommendation (e.g., how to fit exercise into your family’s schedule, tips for eating together as a family, 10 practical tips to eat better on a budget, tips on helping children reduce screen time, ways to incorporate more fruits and vegetables into their child’s diet, how to build a healthy lunch with a checklist of options from which to choose a fruit, veggie, protein), and (3) concrete examples for each topic (e.g., easy to-go breakfast ideas, a table of sugar-sweetened beverages with suggested alternatives and calories saved, a list of healthy choices when eating out, a comprehensive list of fruits and vegetables, a list of physical activities recommended by teens). Reference to the relevant workbook information is integrated into the Fitline coaching call protocol.

3. Structured goal setting, home assignments, and feedback

With coaching from the Fitline nutritionist, parents work with their child to set structured and personally meaningful goals for diet, physical activity, and other weight-related lifestyle changes and engage in related homework assignments between sessions. This includes families documenting/tracking goals, steps taken to achieve their goals, and progress made (i.e., self-monitoring of behavior changes made) which is continuously reviewed at each weekly session with feedback provided by the nutritionist. Unlike with adults with overweight or obesity, parents are not encouraged to monitor their child’s weight at home. Inadvertent focus on weight dieting or body image in children could increase maladaptive responses by parents or children.35,36 Instead, parents are instructed to focus on making healthy eating and physical activity lifestyle changes adapted to the child’s life and health needs. 37,38 Child’s height and weight are measured only at study visits by trained staff using the study scale as per clinical protocol.39,40

The Fitline program provides a total of eight hours of combined intervention: four hours of telephone coaching (eight 30-minute sessions), plus four hours of between-session work (review of written materials; home assignments based on goals set), consistent with meta-analyses indicating that low intensity interventions of 6-8 hours can improve weight-related behaviors and reduce BMI in children with overweight and obesity.15,41

Fitline Coach Training and Fidelity

The four nutritionist coaches are all registered dieticians with a range of 2-25 years’ experience providing nutrition counseling. For the study, the coaches are provided eight hours of baseline training in the Fitline protocol, followed by repeated practice in delivering the protocol with critical feedback by a senior Fitline nutritionist prior to making the first call with families. In preparation for training, the nutritionists review the AAP Guidelines, Fitline protocol, family workbook, and supporting materials (AAP guidelines, patient centered counseling guidance, and selected publications related to pediatric weight loss). During the training, the protocol and family workbook is reviewed with a focus on how to implement each coaching session in a patient centered manner. Following the training and intensive practice sessions, the coaches continued to practice delivery of the protocol with other coaches and receive instruction in using the coaching fidelity checklist that is to be completed following each coaching session. The checklist for each session includes (1) the core activities for all sessions (e.g., checking in about progress on the prior week’s goals, introducing today’s topic, summarizing goals for the coming week, and arranging the follow-up call) and (2) the activities specific to that session (for example, for the session on reducing sweetened beverages, assessing what the child typically drinks, sharing the AAP recommendation that children drink 0 sugar-sweetened beverages and rationale, reviewing the amount of sugar in beverages, and discussing tips for cutting back on sugar-sweetened beverages).

Ongoing supervision to ensure consistency by nutritionists in protocol delivery and quality are provided via weekly check in calls with the coaching team, supervisor and principal investigator during the first year and bi-weekly calls in the second year, plus individual supervision as requested by the coach. These calls are focused on ensuring fidelity to the protocol so that the protocol is delivered consistently across participants and problem solving the nuances of the Fitline lifestyle changes for families. Additionally, to ensure fidelity to the protocol and with permission from the parents, all calls are recorded. A 10% random sample of the calls are reviewed by a senior Fitline nutritionist using the fidelity checklist, who then provides one-on-one detailed feedback to each coach on the degree to which they are following protocol and any areas needing strengthening to enhance fidelity and maximize between-nutritionist consistency.

Theoretical Framework

The Fitline coaching program uses strategies based on the AAP recommendations (motivational interviewing, goal setting, positive reinforcement, and monitoring)42 and is grounded in Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT).43 SCT posits that people learn by receiving instruction and guidance on how to engage in a behavior, by observing or hearing of the actions and outcomes of others’ behavior, and by verbal persuasion, encouragement and support.44 SCT states behavior change involves a number of key constructs, described in Table 3.4.1.b. along with related Fitline strategies. The Fitline-Coaching condition provides families with personalized, patient-centered coaching from a nutritionist addressing all constructs in the theoretical framework, guiding parents in helping their child make lifestyle changes. In contrast, the Fitline-Workbook condition provides families with written materials only, with primary focus on the parent and child’s knowledge and less so on addressing the other SCT constructs.

Table 3.4.1.b.

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) Constructs and Related Fitline Strategies

| SCT Construct | Fitline Strategies |

|---|---|

| Knowledge – the parent and child’s understanding of what constitutes healthy behaviors | Provide information about healthy diet, physical activity; guide parents on sharing this information with their child |

| Outcome expectations – the anticipated benefits of the behavior change | Identify outcomes that will motivate the parent and child to engage in the behavior change |

| Behavioral capability – the knowledge and skills to perform a behavior, learned through goal setting, problem solving, self-monitoring and self-reward; includes parent and child’s ability to set goals, problem solve challenges, track progress, reinforce behavior change | Practical skills training, including goal setting, strategies to engage the child, identifying barriers/problem solving solutions, parenting skills training, homework assignments to apply skills learned; provide encouragement for positive changes made |

| Self-efficacy – the parent and child’s confidence in performing the behaviors, found to predict behaviors including weight loss, smoking cessation, and exercise.45 | Set small, specific and attainable goals; track successes |

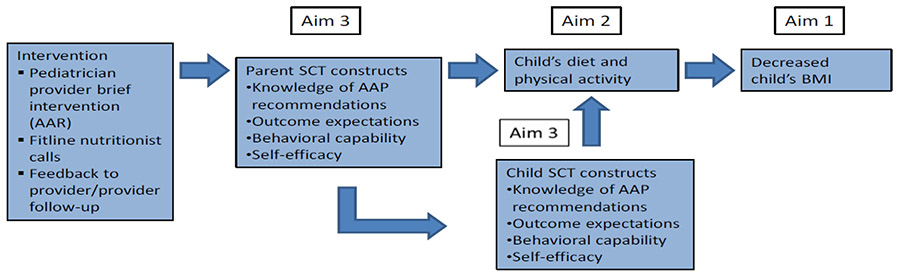

Based on SCT, we hypothesize that the Fitline coaching will help parents develop the knowledge, outcome expectations, behavioral capability and self-efficacy needed to modify the home environment and support their child in making healthy dietary and physical activity changes to reduce BMI. This will in turn assist the child in developing their knowledge, outcome expectations, behavioral capability and self-efficacy needed to make healthy changes. Figure 3.4.1.a. depicts our hypothesis, that the Fitline-Coaching intervention will directly impact on the parent’s and subsequently child’s SCT constructs (mediators), affecting the child’s weight-related behaviors, which will then lead to reduction in BMI.

Figure 3.4.1.a.

Conceptual Model Based on SCT Theoretical Framework for the Fitline-Coaching Program

3.4.2. Pediatric Practice plus Workbook (Fitline-Workbook) Condition

Pediatric Practice plus Workbook (Fitline-Workbook) Condition.

Practices randomized to the Fitline-Workbook condition receive the same pediatric practice-based assistance in setting up their office systems to implement the Let’s Go 5-2-1-0 program and the same group training program for the pediatric providers as described earlier (see Section 3.4.1.), with the exception of any reference or access to the Fitline coaching. When a family in this condition expresses interest in participating in the study, the provider lets them know they will receive weekly mailings. For the parent support component, families receive the same educational workbook materials as those provided in the Fitline-Coaching condition mailed over 8 weeks. The content and timing of topics is identical to that covered each week in the Fitline coaching program to control for weekly contact and educational curriculum. In this way, the two conditions will be identical with the exception of the Fitline coaching and feedback to the referring provider, allowing the testing of the effectiveness of the Fitline coaching component. This rigorous comparison condition was selected to control for pediatric practice systems, provider intervention and weekly educational curriculum, thus testing the added effect of the personalized Fitline coaching from a centrally located nutritionist

3.5. Measures

All data for study aims 1-3 are collected at three timepoints – at baseline and at 6- and 12-months post-baseline – from parents and children through anthropometric measures collected by research staff during study visits held in the pediatric primary care clinic, and through surveys, accelerometry, and phone interviews (24-hour dietary and physical activity recalls). Assessments have been used with children and parents in our pilot study 23 and other studies. Data confidentiality will be emphasized on the surveys and verbally by research staff, and by the use of unique identification numbers.

3.5.1. Primary Outcome Measures

Anthropometrics

Weight and height will be measured in clinic by research staff during each study visit using standard methodology;39 BMI will be calculated from weight (kg)/height squared (in meters) and BMI for age/sex will be determined using CDC growth charts46 for the child. Overweight is defined as a BMI at or above the 85th percentile and below the 95th percentile for children and teens of the same age and sex; obesity is defined as a BMI at or above the 95th percentile for children and teens of the same age and sex.

3.5.2. Secondary Outcome Measures

Dietary behavior

Dietary behavior is assessed through three unannounced 24-hour dietary recall interviews (similar to CATCH trial),47 validated with children.48 The Nutrient Data System for Research, updated annually, is used to quantify timing, location, and quality of dietary intake. Seven relevant items from an instrument developed by Ammerman recommended by Glasgow49 assesses specific self-management dietary behaviors targeted by the intervention.

Physical Activity

Physical activity is assessed by accelerometry. Accelerometer data from ActiGraph Model GT1M or GTX3+ for 7 days averaged, recommended for children,50 is used as an independent assessment of activity in both the children and the parent. In addition, during the first of the three 24-hour dietary recalls conducted at each assessment timepoint (baseline 6- and 12-month assessments), a 7-day Physical Activity Recall interview will be conducted.51,52,53,54 A single item adapted from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention assesses self-reported number of days during the past 7 days that the child was physically active for at least 60 minutes per day (0-7 days), which is the goal of the AAP recommendation and the intervention.

Sedentary behavior is measured by YRBS items49 which assess average number of hours of TV and hours playing computer or non-active video games. Sedentary time also will be calculated from the accelerometer data.

3.5.3. Potential Mechanisms of Effect/Mediators

Possible mechanisms of the effect of the Fitline-Coaching program on BMI, diet and physical activity are assessed by both parent and child measures.

Parent-completed measures.

The parent’s Social Cognitive Theoretical (SCT) constructs are assessed by a brief measure of their knowledge of the AAP recommendations; measures55,56,57,58 adapted for our prior obesity trial to assess parents’ outcome expectations for their child’s weight-related changes (e.g., improve his/her health, school performance, self-esteem, and energy) and behavioral capability in helping their child set goals and problem solve to eat healthy and be physically active; and the Parental Self-Efficacy for Obesity Prevention Related Behaviors,59 which assesses parent’s self-efficacy and skills in dealing with their child’s weight-related challenges. Caregiver Attitudes and Belief’s Survey assesses perceived social support and barriers to supporting their child behavior changes (created by the investigators). Their stress over the past month is assessed by the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)60 and depression by a brief screener, the PHQ-4.61

The health of the family system62 and parenting style63 also are assessed. Parent BMI is calculated from weight (kg)/height squared (in meters) measured in clinic during study visits using standard methodology. Their dietary behavior is assessed with seven items from an instrument developed by Ammerman recommended by Glasgow49 that assesses specific self-management dietary behaviors targeted by the intervention. Their physical activity is assessed with accelerometry as well as with a single item physical activity measure64 which assesses the number of days in the past week they have engaged in a total of 30 or more minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity. Parents also report on both parent and child demographics (e.g., age, gender, socio-economic status, race/ethnicity, number of other children living in the home, parent education level, marital status) at baseline and pubertal status of their child (initiation of menstruation (girls) or facial hair/voice change (boys)).

Child-completed measures.

The child’s Social Cognitive Theoretical (SCT) constructs are assessed by a brief measure of their knowledge of the AAP recommendations; measures55-58 adapted for our prior obesity trial to assess child’s outcome expectations for their weight-related changes (e.g., improve his/her health, school performance, self-esteem, and energy) and behavioral capability in setting goals and problem solving to eat healthy and be physically active; and measures from the Go Girls65 and GEMS58 studies used in children to assess self-efficacy. The Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale for Healthy Behaviors measures social support for weight-related behaviors (parental support and friend support).66 A brief measure adapted from New Moves67 for children assesses their barriers to change. Quality of life is assessed with the Child Health Utilities Index (CHU9D),68 which is used to measure health status and health-related quality of life and provides a measure of child health utility for cost-effectiveness analyses.

3.5.4. Cost-effectiveness

We estimate the cost-effectiveness of the Fitline-Coaching program compared with the Fitline-Workbook program in terms of cost per change in quality adjusted life-years (QALYs) and per reduction in the child’s BMI. Costs include those of (1) provider training and intervention, (2) office set-up and support, (3) intervention materials, and (4) Fitline coaching calls (Fitline-Coaching only) measured and tracked by study staff. The primary effectiveness measure is change in quality adjusted life-years (QALYs). QALYs, a common health outcome used in cost-effectiveness analyses, are a measure of disease burden which incorporates both the quality and the quantity of life lived. QALYs will be calculated from utility scores derived from the Child Health Utilities Index (CHU9D).68 The CHU9D measures health status and health-related quality of life. The tool has demonstrated reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change in pediatric populations.69 Secondary outcomes include change in BMI. The CHU9D is used to measure health status and health-related quality of life and can be used to produce utility scores for QALY calculation. The tool has demonstrated reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change in pediatric populations.69

3.5.5. Process data

The feasibility of implementing the pediatric office-based components (i.e., the extent to which providers deliver the brief AAR intervention per protocol) is assessed in both conditions through a Patient Exit Interview survey on the parent’s baseline survey. Parent utilization and receptivity to the Fitline coaching program (Fitline-Coaching only) is assessed by percentage of eligible families referred to the program, number of Fitline coaching sessions completed (i.e., intervention dose), and parent report of receptivity and recommendations for further refinement for future dissemination via the six month survey. Fidelity to Fitline coaching intervention protocol by nutritionists is assessed by review of a 10% random sample of audiotapes of Fitline coaching sessions, and by nutritionist checklists. To assess intervention fidelity, we will include a random effect for nutritionist to determine between-nutritionist consistency. Nutritionist tracking of coaching calls process will be provided through the Coaching Call Tracking form, which tracks attempts to schedule the coaching calls, dates of completion for each all, total time spent on the call, and perceived level of parent engagement (1=not at all to 5=very). Parent self-report of number of mailings received and number for which parent read at least 80% of content assesses fidelity to material mailing (Fitline-Workbook only). A provider survey at baseline and end of intervention in both conditions assesses feasibility of intervention delivery, barriers to treatment, and provider-reported attitudes, self-efficacy, and practice.

3.5.6. Demographics

The following demographics are collected from the parent survey: age and gender of parent, socio-economic status, race/ethnicity, number of other children living in the home, parent education level, marital status, and parental perception of child’s weight status. From the child survey: age, gender, and race/ethnicity.

4. Analysis Approach/Analytic Plan

Baseline characteristics of participants – both children and parents – will be summarized using frequencies and means (standard deviations), comparing Fitline-Coaching and Fitline-Workbook groups using chi-square and two-sample t-tests. Analyses to test study aims will be intent-to-treat. We will identify correlates of retention at 6 and 12 months, to be included as longitudinal model covariates to reduce possible bias from nonresponse.70 Additional approaches for handling missing data include multiple imputation,70 such as imputation of missing accelerometer physical activity based on the 7-day physical activity recall measure. Models also will include a random effect for practice to account for the clustered sampling and randomization. Model fit will be assessed via the Akaike information criterion71 as well as checks on assumptions such as normally distributed residuals; variables will be transformed if needed to satisfy model assumptions. All analyses will be conducted in SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Aim 1: Determine the effectiveness of the Fitline-Coaching program in reducing BMI in children with overweight and obesity.

We will estimate a linear mixed model72 for BMI at 6 and 12 months as a function of time point, Fitline-Coaching / Fitline-Workbook, and their interaction, with adjustment for baseline BMI to account for possible regression to the mean.73 We hypothesize a statistically significant greater 6-month decline in BMI and 12-month maintenance of BMI loss for Fitline-Coaching than for Fitline-Workbook. Adjustment for covariates will focus on those predictive of the outcome, regardless of whether they differ by randomization condition.74 We also will test interactions between time point and predictors to assess whether predictors differ for 6-month BMI loss and 12-month maintenance. Parallel models will be estimated for the binary outcome of the child being classified as having overweight versus obesity, using generalized linear mixed modeling.75

Aim 2: Determine the effectiveness of the Fitline-Coaching program in improving the child’s diet and physical activity behaviors.

We will use the same analytic strategy as for Aim 1 to compare changes in diet and physical activity by treatment condition. For both dietary and physical activity outcomes we have complementary measures that capture different aspects of diet and physical activity. Separate models will be estimated for each outcome, to assess whether intervention-related differences are consistent across measures or whether the intervention is particularly beneficial for a subset of outcomes. We will average total energy intake (kcal/day) across the three 24-hour dietary recalls at each timepoint for a more stable estimate for each participant. Each of the seven Ammerman diet items will be analyzed using methods appropriate for count data, such as generalized linear mixed models for Poisson or negative binomial outcomes.49 The accelerometer data and data from the 7-day physical activity recalls will both provide an independent measure of PA, as well as a measure of the number of days of physical activity in the last week. For accelerometer data, we will summarize the 7 days of data by modeling the 7-day mean. Because activity level will likely vary between weekends and weekdays, we will explore modeling mean weekday activity and mean weekend activity separately. Since participants likely will be missing valid days of data, we also will calculate an average using two weekend and two week days. We will examine whether results are consistent across the two approaches, and are consistent with the 24-hour physical activity recall data. Sedentary time also will be calculated from the accelerometer data.

Aim 3: Explore possible mechanisms of the effect of the Fitline-Coaching program on BMI, diet and physical activity.

We will expand the models for Aims 1 and 2 above to include hypothesized mediator variables, with a focus on the impact of the coaching program on parent and child Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) constructs such as outcome expectations, self-efficacy, and behavioral capability, as well as on parental BMI and related parent and child dietary and physical activity behaviors. Additional secondary analyses will examine effect modifiers of Fitline-Coaching / Fitline-Workbook differences; potential moderator variables include baseline characteristics such as age, gender, and parental education. These analyses will facilitate identification of subgroups who respond particularly well to the intervention.

Aim 4: Estimate the cost-effectiveness of the Fitline-Coaching program compared with Fitline-Workbook program in terms of cost per reduction in the child’s BMI.

Cost-effectiveness analyses will be conducted to compare the costs and health outcomes of the two interventions, in order to identify the value of the Fitline coaching intervention. Analyses will be conducted over a one-year horizon from a health care utilization perspective. The primary effectiveness outcome will be change in quality adjusted life-years (QALYs). Secondary outcomes will include change in BMI. We will calculate and report incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs)76 that compare the costs and outcomes of the Fitline-Coaching and Fitline-Workbook interventions. ICERs will be calculated by rank-ordering the strategies by increasing cost and comparing the more costly strategy with the less costly strategy by dividing the additional cost by the additional benefit. Cost-effectiveness will be expressed as cost per change in QALY gained and per BMI. We will use sensitivity analysis for varying inputs over realistic ranges to test the extent to which our findings remain robust over the range of plausible inputs. Additional analyses will be conducted to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the interventions relative to estimates of one-year changes in quality of life and BMI among children receiving usual care obtained from published literature.

Exploratory analyses: Feasibility of pediatric providers and their practices in implementing the pediatric office-based components (both conditions).

Our process variables include: recruitment (number of families identified and agree to participate), number of providers receiving recruitment forms and returning forms after delivering intervention, and number of families referred to the Fitline program (both the Fitline-Coaching and Fitline-Workbook programs).

In addition, parent utilization and engagement/receptivity to the Fitline program will be assessed in both study conditions. Parents in both conditions will self-report their engagement with and receptivity to the Fitline program on the 6-month survey. For the Fitline-Coaching condition only, parents will self-report their comfort in discussing their child’s diet and physical activity with the Fitline coach, as well as how helpful the coaching sessions were in their efforts to help their child eat healthy and increase their physical activity. Fitline nutritionists will track the number of telephone coaching sessions completed by each parent referred to the coaching calls. For the Fitline-Workbook condition only, parents will self-report whether they received and read each of the 8 weekly mailed workbook materials, the number of minutes spent reading the materials, and an estimate of the overall percentage of the materials they read. In both study conditions, parents will self-report the degree to which they found the family workbook to be helpful in their efforts to help their child eat healthy and increase their physical activity, how likely they would recommend the Fitline program to their friends and family, the degree to which they were able to put into action strategies learned, the three most helpful areas covered in the program, whether they shared the information learned with their child, and whether they worked with their child to set goals and monitor progress. These data will be reported using standard statistical techniques. Some of these variables, such as participation in coaching calls, can be used as explanatory variables in analyses described above.

Sample Size Determination

The target sample size is selected to achieve 80% power to detect a between-group mean difference in within-child change of 1.5 BMI units (kg/m2) at 6 months, using a two-sided two-sample t-test with 0.05 Type I error. This difference corresponds to approximately 10 pounds in 10-year-old children with an average height of 56 inches, a clinically meaningful difference in this age group. Moreover, this difference is similar to an extrapolation (doubling) of the 3-month change of 0.85 kg/m2 observed in our pilot study],23 and thus is expected to be attainable. We note that the between-group difference could reflect both weight loss in the Fitline-Coaching group and weight gain in the Fitline-Workbook group. Using an estimated average standard deviation of 5.0 using CDC data from 2007-2010 (Table 4.7.), we will need 176 children per group at 6 months. To arrive at the number needing to be recruited, we account for both attrition – 15% was selected as a conservatively large value well over the attrition in our prior pediatric practice-based studies which had much lower attrition (0% to less than 5% attrition)23,77 in order to account for greater participant burden in the current trial – as well as within-in practice clustering. Considering physicians are unlikely to implement a weight reduction intervention over a 12-month period, and parents are unlikely to choose a physician based on their child’s weight, we assume a low intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.01. With an anticipated average of N=21 children per practice, the resulting design effect due to clustering (DEFF) is 1 + ICC×(N-1) = 1.20, yielding needed per-group recruitment of 176 × 1.20/0.85 = 248 children.

We initially recruited 16 practices but increased to 20 practices after finding a lower-than-anticipated participant rate; this yields a slightly lower design effect than the original calculation, as number of children per practice is slightly smaller.

5. Participant Safety

The following steps and safeguards are being implemented to monitor and maximize the safety of participants.

The interventions are state-of-the-art and represent good standards of care as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). They are fundamentally educational and are designed with the participants’ best interests in mind.

All study investigators as well as the nutrition team conducting the Fitline telephone counseling calls have experience with and a reputation for designing and delivering culturally-sensitive, patient-centered programs, and are accountable to those standards.

The potential risks of the evaluative research component of this project are small. In order to safeguard the confidentiality of participants’ surveys and study records, a number of strategies are maintained. First, the study staff are trained on how to reassure any participants who may raise concerns. Each participant is assigned a unique study identification number. The only individuals who have access to these identifiers are the Program Director and Research Assistant responsible for data collection. Other research personnel and investigators are not privy to identifying information about the individual participants. Subsequent protection of study data is assured by the use of locked files and password-protected computer data bases with access available only to the principal study personnel.

Another possible risk is the potential for parents and children to feel uncomfortable discussing their weight and disclosing their nutrition and physical activity behaviors. To mitigate this risk, the clinic and project staff are trained on how to minimize these risks and reassure any participants who might raise concerns about confidentiality and how to implement assessment protocols in a sensitive and respectful manner to minimize discomfort.

A Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) is established for this Phase III clinical trial. The DSMB consists of three members, one epidemiologist, one pediatrician, and one pediatric psychologist. The board meets every 6 months to review data quality and safety.

There is also a core group from the research team consisting of the Principal Investigator that is responsible for ongoing monitoring of the trial and reporting to our Human Subjects Committee any issues regarding the safety of study subjects or threats to data integrity. The Human Subjects Committee at UMMS is a fully authorized Institutional Review Board that provides oversight to research conducted at the medical school. This committee will be providing oversight to the current study.

5. Discussion

The AAP recommends supporting families of children with overweight and obesity to work toward establishing healthy lifestyles,4 yet strikingly, there has been little research on how to implement this recommendation within the constraints of real-world clinical practice. There is a strong and compelling need for theory-driven approaches to deliver accessible, skilled coaching services to support parents in creating a healthy eating and activity environment, and in guiding their children in making healthy choices outside the home. Given the majority of children see their pediatric provider each year,78,79 there is tremendous opportunity for systematic identification, brief intervention, and referral to more intensive counseling as offered through the personalized Fitline calls. The program goes beyond providing information on diet and physical activity by including customized coaching to parents on concrete strategies to create a healthy eating and activity environment, and to engage, communicate with and support their children.

The model underlying Fitline, using trained nutritionists to coach parents telephonically in improving their child’s diet and physical activity, is highly innovative and has the potential for significant public health impact, providing an evidence-based model that can be implemented within pediatric practices. Most pediatric practices have difficulty implementing AAP guidelines due to limited provider time and poor access to nutritionists to whom they can refer. The Fitline model gives providers an easily-accessed referral resource, trained nutritionists in a centralized call center to coach parents in improving their child’s weight-related behaviors. This model is similar to the successful use of telephone Quitlines, which are effective in improving smoking cessation rates80 but have limited reach in the absence of specific marketing campaigns. Pediatric practices are viewed by families as a trusted source of information and guidance. Thus, having the pediatric provider recommend the Fitline intervention may be more impactful and motivating to families than coming across a resource such as a Quitline on their own. The Fitline model also has the potential to improve access beyond what Quitlines achieve by working within pediatric offices to prompt referrals.

In addition, while large-scale telephone care management strategies are widely used in adult settings and have been demonstrated to be cost-effective,81 they have yet to be tested in addressing childhood obesity. Demonstrating cost-effectiveness is key to disseminating the intervention beyond the initial trial. Using a telephone-based approach addresses many of the significant barriers to accessing specialized care for weight management for families, including distance to programs and difficulties with transportation, cost, and coordination of family schedules, issues that are particularly salient for children of low-income families who have the least access to care and are at the highest risk of obesity.14,16,17 This approach also provides a more systematic and robust way to deliver treatment compared to the sporadic, episodic care possible within in-person practices, and is consistent with the AAP’s exploration of telemedicine for pediatrics.15,82,83 Moreover, delivery of treatment via telephone may improve efficacy by providing parents coaching and support in implementing the AAP recommendations in their real world contexts.

With over a third of pre-adolescent children being with overweight or obesity, pediatric providers continue to struggle to help families make changes in eating and activity habits. In addition to the challenges of limited time, referral sources and the burden of accessing in-person weight management programs, pediatric providers and families now face the added challenge of contact and travel restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, in response, the medical care delivery system is currently shifting to a more hybrid model. While the Fitline coaching program was developed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was purposefully designed to be a feasible means of remote delivery of weight management assistance for pediatric providers to recommend to families that can overcome many of the barriers to accessing weight management programs. The current study aims to detect whether individualized telephone support from a trained nutritionist can enhance outcomes above the provision of written education alone. Should this trial demonstrate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of Fitline coaching, this program has potential for widespread implementation, such as nationally through the CDC, through state’s Medicaid programs, or regionally through a health insurer or large health plan or HMO.

This study has a number of potential limitations. First, only families willing and able to complete the rigorous study assessments, including surveys, anthropometric measurements, accelerometry, and 24-hour dietary recalls, are eligible to enroll in the trial. It is possible that families with many competing demands and limited time or resources may opt out of participating in the study, thus reducing generalizability of study findings. Families are compensated for their time to complete assessments, which may mitigate this concern to some degree. Second, it is possible that children will underreport their dietary intake on the 24-hour dietary recalls, consistent with the finding that such underreporting of dietary intake occurs more among children with overweight and obesity than those without.84 This underreporting may be expected to be similar across conditions. However, a third possible limitation is that there may be greater social desirability bias on the part of families in the coaching compared to the workbook alone condition, resulting in overreporting healthy behaviors and underreporting unhealthy behaviors on the survey and 24-hour dietary recalls to present themselves in a way they feel their coaches would consider favorable, thus biasing the data. To mitigate this concern, research staff will emphasize that all assessments are confidential (24-hour recall dieticians are blinded to study arm) and will not be shared with their pediatric providers or coaches. Alternatively, families in the coaching condition may be more accurate in reporting their dietary intake because they have learned more during the intervention about being aware of and estimating foods and portion sizes. However, in a study of youth report of fruit and vegetable intake in a behavioral nutrition intervention trial, differential response bias in reporting of dietary intake due to involvement in the intervention was not observed.85

There are many strengths to this study. First, this trial is based on our nonrandomized intervention pilot study (ClinicalTrials.gov ID# NCT02085434)23 which found improvements in BMI, diet and physical activity compared to a contemporaneous control. This pilot informed development of the current study, including refining the intervention and guiding recruitment and retention processes. Second, the study design and choice of comparison condition allows for testing the independent contribution of the Fitline coaching calls separate from the effect of pediatric provider intervention and family workbook. Third, the study addresses health disparities by making more easily-accessible weight management resources available to all families, and in particular low-income families and their children who are at highest risk of obesity and experience the least access to care.14,16,17 In addition, the practices selected are representative of practices that serve children across the socioeconomic spectrum. Fourth, the telephonic-based intervention being tested enhances accessibility to personalized and expert guidance delivered conveniently to the parent. As has been seen with the burgeoning interest in telehealth in the COVID-19 era, use of the phone or some version of tele-coaching will become increasingly popular, particularly when personalized to the patient. Fifth, high quality dietary and physical activity assessments are being used, including 24 hour dietary recalls validated in children48,86 and accelerometry recommended for children.50 Sixth, a unique feature of this trial design is the exploration of the potential mechanisms of the effect of Fitline on BMI, diet, and physical activity, including parental and child Social Cognitive Theory constructs such as outcome expectations, self-efficacy, and behavioral capability on each outcome. Additional secondary analyses will examine effect modifiers of Fitline-Coaching / Fitline-Workbook to determine whether the impact of the intervention differs based on factors such as age, gender, and parental education, and thus will have implications on the future target population for implementation. Seventh, using the 5-2-1-0 model and AAP clinical recommendations which focus on health behaviors as opposed to weight loss makes the intervention more palatable to both pediatric clinicians and families. And lastly, if the coaching program is found effective, funding mechanisms could include coverage through third-party insurers and employer-paid benefits that commonly pay for health coaching plans. Cost analyses from this trial will inform the resources needed to implement the Fitline program for nationwide dissemination. Examining cost-effectiveness as well as effectiveness for lifestyle change will provide critical information to support implementation of Fitline-Coaching.87 Moreover, the process outcomes measuring feasibility of incorporating this intervention into pediatric provider practice, palatability of the intervention to families and providers, and fidelity to the intervention itself will allow for evaluation of real-world implementation during the clinical trial, thus enhancing the potential adoption of Fitline-Coaching into clinical settings if proven to be effective.

It is anticipated that the results from this trial will have important implications for the prevention and treatment of childhood obesity, both for families wanting to make healthy lifestyle changes to support their children with overweight and obesity, and the pediatric clinicians caring for them. If found to be cost-effective, future directions include understanding what families may benefit most from the intervention and conducting a dissemination and implementation trial to maximize the ability to effectively disseminate this program nationwide.

Table 4.

Estimated Standard Deviations and Percentiles for Body Mass Index (BMI) among Children Aged 8-12 Years Based on CDC Data46

| Age | Mean BMI (kg/m2) |

S.D. BMI (kg/m2) |

85th Percentile | 95th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| 8 | 18.1 | 4.65 | 22.2 | 24.9 |

| 9 | 18.8 | 5.71 | 23.3 | 26.9 |

| 10 | 19.6 | 4.37 | 23.8 | 27.2 |

| 11 | 20.6 | 6.18 | 26.0 | 30.0 |

| 12 | 21.3 | 5.94 | 26.8 | 30.2 |

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) R01 HL130505 (PI: L Pbert).

Abbreviations

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- BMI

body mass index

- AAR model

Ask, Advise, Refer

- SCT

Social Cognitive Theory

- QALYs

quality adjusted life-years

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Trial Registration

The ClinicalTrials.gov registration number is NCT03143660.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The NS, Suchindran C, North KE, Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P. Association of adolescent obesity with risk of severe obesity in adulthood. JAMA. 2010;304(18):2042–2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35(7):891–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barlow SE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007; 120 Suppl 4:S164–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polacsek M, Orr J, Letourneau L, et al. Impact of a primary care intervention on physician practice and patient and family behavior: keep ME Healthy---the Maine Youth Overweight Collaborative. Pediatrics. 2009;123 Suppl 5:S258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polacsek M, Orr J, O'Brien LM, Rogers VW, Fanburg J, Gortmaker SL. Sustainability of key Maine Youth Overweight Collaborative improvements: a follow-up study. Child Obes. 2014;10(4):326–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel AI, Madsen KA, Maselli JH, Cabana MD, Stafford RS, Hersh AL. Underdiagnosis of pediatric obesity during outpatient preventive care visits. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(6):405–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanda R, Salsberry P. The impact of the 2007 expert committee recommendations on childhood obesity preventive care in primary care settings in the United States. J Pediatr Health Care. 2014;28(3):241–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rausch JC, Perito ER, Hametz P. Obesity prevention, screening, and treatment: practices of pediatric providers since the 2007 expert committee recommendations. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50(5):434–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moyce SC, Bell JF. Receipt of Pediatric Weight-Related Counseling and Screening in a National Sample After the Expert Committee Recommendations. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein JD, Sesselberg TS, Johnson MS, et al. Adoption of body mass index guidelines for screening and counseling in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):265–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh CO, Milliren CE, Feldman HA, Taveras EM. Factors affecting subspecialty referrals by pediatric primary care providers for children with obesity-related comorbidities. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2013;52(8):777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper S, Valleley RJ, Polaha J, Begeny J, Evans JH. Running out of time: physician management of behavioral health concerns in rural pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):e132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sesselberg TS, Klein JD, O'Connor KG, Johnson MS. Screening and counseling for childhood obesity: results from a national survey. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(3):334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spear BA, Barlow SE, Ervin C, et al. Recommendations for treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2007;120 Suppl 4:S254–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freedman DS, Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Dietz WH. Childhood overweight and family income. MedGenMed. 2007;9(2):26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wells NM, Evans GW, Beavis A, Ong AD. Early childhood poverty, cumulative risk exposure, and body mass index trajectories through young adulthood. American journal of public health. 2010;100(12):2507–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janicke DM, Sallinen BJ, Perri MG, et al. Comparison of parent-only vs family-based interventions for overweight children in underserved rural settings: outcomes from project STORY. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(12):1119–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalavainen MP, Korppi MO, Nuutinen OM. Clinical efficacy of group-based treatment for childhood obesity compared with routinely given individual counseling. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31(10):1500–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.West F, Sanders MR, Cleghorn GJ, Davies PS. Randomised clinical trial of a family-based lifestyle intervention for childhood obesity involving parents as the exclusive agents of change. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(12):1170–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]