Abstract

Introduction

Real-world trial data comparing single- with multiple-inhaler triple therapy (MITT) in COPD patients are currently lacking. The effectiveness of once-daily single-inhaler fluticasone furoate (FF)/umeclidinium (UMEC)/vilanterol (VI) and MITT were compared in usual clinical care.

Methods

INTREPID was a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase IV effectiveness study comparing FF/UMEC/VI 100/62.5/25 µg via the ELLIPTA inhaler with a clinician's choice of any approved non-ELLIPTA MITT in usual COPD clinical practice in five European countries. Primary end-point was proportion of COPD Assessment Test (CAT) responders (≥2-unit decrease in CAT score from baseline) at week 24. Secondary end-points in a subpopulation included change from baseline in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and percentage of patients making at least one critical error in inhalation technique at week 24. Safety was also assessed.

Results

3092 patients were included (FF/UMEC/VI n=1545; MITT n=1547). The proportion of CAT responders at week 24 was significantly greater with FF/UMEC/VI versus non-ELLIPTA MITT (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.13–1.51; p<0.001) and mean change from baseline in FEV1 was significantly greater with FF/UMEC/VI (77 mL versus 28 mL; treatment difference 50 mL, 95% CI 26–73 mL; p<0.001). The percentage of patients with at least one critical error in inhalation technique was low in both groups (FF/UMEC/VI 6%; non-ELLIPTA MITT 3%). Safety profiles, including incidence of pneumonia serious adverse events, were similar between treatments.

Conclusions

In a usual clinical care setting, treatment with once-daily single-inhaler FF/UMEC/VI resulted in significantly more patients gaining health status improvement and greater lung function improvement versus non-ELLIPTA MITT.

Short abstract

Once-daily single-inhaler treatment with FF/UMEC/VI results in greater improvements in health status and lung function compared with non-ELLIPTA multiple-inhaler triple therapy in patients with COPD in a usual clinical practice setting https://bit.ly/2PHXNwU

Introduction

Triple therapy with inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) and long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) for COPD has traditionally required use of multiple inhalers, sometimes several times per day [1]. However, patients’ persistence and adherence with COPD medication administered via multiple inhalers have been shown to be worse than with therapy administered via a single inhaler [2, 3]. Reducing the number of inhalers required and frequency of use should improve treatment persistence and adherence, which could in turn improve clinical effectiveness and patient outcomes [4, 5]. Fewer inhalers and reduced treatment complexity has been highlighted as a preferred treatment strategy for patients with COPD [6, 7]. In addition, the use of multiple inhalers has been associated with more frequent errors in inhaler technique compared with therapy administered via a single inhaler [8]. This may result in worse symptom control, as shown in observational studies [9, 10], and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease report recommends that inhaler technique and adherence be checked regularly as part of routine follow-up and before changing treatment [11].

Single-inhaler triple therapy (SITT) is a recent development for COPD treatment and could provide a more practical option for patients [1, 12]. In conventional randomised controlled trials (RCTs), SITT with fluticasone furoate (FF)/umeclidinium (UMEC)/vilanterol (VI) has shown significant reductions in moderate/severe exacerbation rates and significant improvements in lung function and health status compared with dual therapy with FF/VI, UMEC/VI or budesonide/formoterol [13, 14]. Recent RCT results indicate that FF/UMEC/VI SITT may provide more sustained lung function benefit compared with budesonide/formoterol plus tiotropium multiple-inhaler triple therapy (MITT) [15]. However, evidence from controlled studies supporting the superiority of single-inhaler combination therapy versus multiple-inhaler therapy on health status and symptoms is needed [16]. Conventional double-blind RCTs include highly selected patient populations, involve using dummy inhalers and are conducted in highly controlled environments, which may limit the applicability of the results to routine clinical care [17–19].

Effectiveness studies provide real-world context to complement conventional RCTs, as they enrol patients more representative of those prescribed treatment in routine care, do not involve dummy inhalers [20] and allow physicians and patients to prescribe and take their medication as they would in usual care settings. The Salford Lung Study demonstrated the effectiveness of once-daily FF/VI single-inhaler therapy over usual care in a COPD population [21]. However, data are lacking with respect to health status benefits of SITT versus MITT in COPD in usual clinical care settings.

The INTREPID (INvestigation of TRelegy Effectiveness: usual PractIce Design) study was designed to build on the effectiveness data obtained in the Salford Lung Study to investigate the impact of SITT with FF/UMEC/VI versus MITT on health status over 24 weeks in a usual clinical care setting across multiple sites in five European countries.

Materials and methods

Study design

INTREPID (GSK study 206854; clinicaltrials.gov NCT03467425) was a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase IV effectiveness study comparing once-daily single-inhaler FF/UMEC/VI delivered by the ELLIPTA inhaler with any licenced non-ELLIPTA MITT in patients with COPD in a usual clinical practice setting. The trial protocol has been described previously [22]. The primary objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of FF/UMEC/VI versus non-ELLIPTA MITT on health status in patients with COPD after 24 weeks of treatment.

Patients were randomised 1:1 to receive either once-daily FF/UMEC/VI 100/62.5/25 µg or continue with their usual twice-daily triple therapy regimen (ICS+LAMA+LABA) administered via multiple non-ELLIPTA inhalers (non-ELLIPTA MITT). Patients on dual therapy at screening who were deemed by the clinician to need triple therapy were stepped up at randomisation. Randomisation was stratified based on previous treatment (ICS+LABA, LAMA+LABA or ICS+LAMA+LABA) and recruitment of patients on prior dual therapy was not to exceed a combined total of ∼50% for each country. Patients continued to use short-acting β2-agonist therapy as required.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were minimal [22]; details are provided in the supplementary material.

This trial was conducted at 147 centres in the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden from April 2018 to October 2019 in usual care settings. It was carried out in accordance with good clinical practice guidelines under the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from local institutional review boards or independent ethics committees. All patients provided signed informed consent.

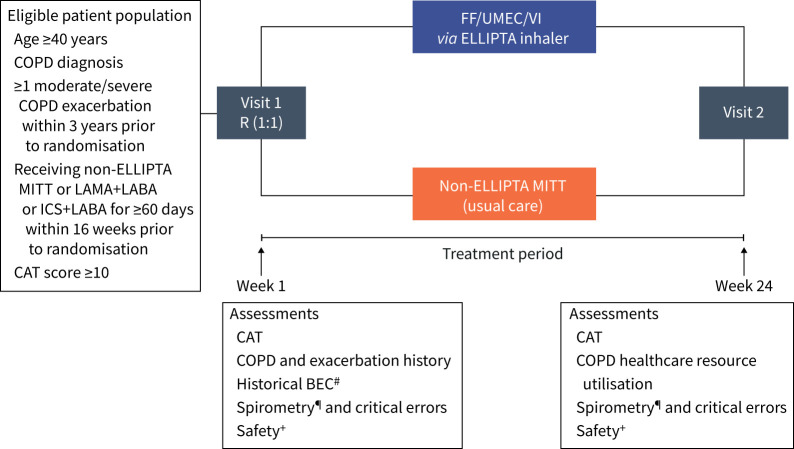

To minimise deviations from usual care and impact on normal patient behaviour, patients were managed by their clinician in accordance with usual care practice and only two study visits were mandated: screening/randomisation (visit 1) and study end (visit 2; week 24) (figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study design. MITT: multiple-inhaler triple therapy; LAMA: long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist; LABA: long-acting β2-agonist; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; CAT: COPD Assessment Test; FF: fluticasone furoate; UMEC: umeclidinium; VI: vilanterol; R: randomisation; BEC: blood eosinophil count. #: where available, peripheral BECs were collected using the historical value closest to the patient's consenting visit and no later than 36 months prior to visit 1; ¶: patients were asked, if possible, to withhold short-acting β2-agonists or short-acting anticholinergics for ≥4 h and not to take either their single-inhaler triple therapy or MITT until after the clinic visit at week 24 to enable measurement of trough forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1). If this was not possible or had not been done, FEV1 was still measured; +: safety information was collected at all scheduled or usual care visits recorded in the electronic case report form.

In total, 3000 patients were required to obtain sufficient power to assess the primary outcome, but only ∼1520 patients were required to assess secondary outcomes [22]. Therefore, in order to minimise disruption to usual care, spirometry data were only collected in Germany and the United Kingdom. In addition, critical errors in inhalation technique were only assessed in patients enrolled at centres within the countries participating in spirometry assessment and only if an appropriate error checklist was available for all of the inhalers they were using. Details on the production and validation of the error checklists have been published previously [22].

Effectiveness outcomes

The primary end-point was proportion of responders based on the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) at week 24. A clinically meaningful response was defined as a decrease in CAT score of ≥2 units from baseline [23]. Secondary end-points included change from baseline in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and percentage of patients making at least one critical error in inhalation technique at week 24.

In addition, an exploratory treatment comparison of FF/UMEC/VI versus non-ELLIPTA MITT was performed for the primary outcome by prior medication strata. Details of the analysis populations and statistical analyses are provided in the supplementary material. In brief, the proportion of CAT responders was analysed in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population using a logistic regression model with treatment as an explanatory variable and covariates of baseline CAT score, number of exacerbations in the prior year, actual prior medication use strata, and country. For analysis of the primary end-point using the primary estimand, patients who modified their randomised treatment, changed pulmonary rehabilitation status or started oxygen therapy were considered as nonresponders. CAT data for patients who discontinued randomised treatment without receiving another COPD maintenance therapy during the study were used if available (supplementary table S1). Missing week 24 CAT data were imputed using multiple imputation based on the randomised treatment arm characteristics assuming missing at random (supplementary table S1). Three supportive estimands were defined for the primary end-point, with different strategies for handling intercurrent events or events leading to missing data (supplementary table S1). Details of the statistical analyses for the secondary outcomes and the exploratory analysis of the primary outcome can be found in the supplementary material.

Safety assessments

Adverse-event recording was limited to treatment-related adverse events, serious adverse events (SAEs) and adverse events leading to study treatment discontinuation or study withdrawal. Serious adverse events of special interest (AESI), i.e. SAEs which have specified areas of interest for FF, VI or UMEC or the overall COPD population, were also collected.

Results

Trial population

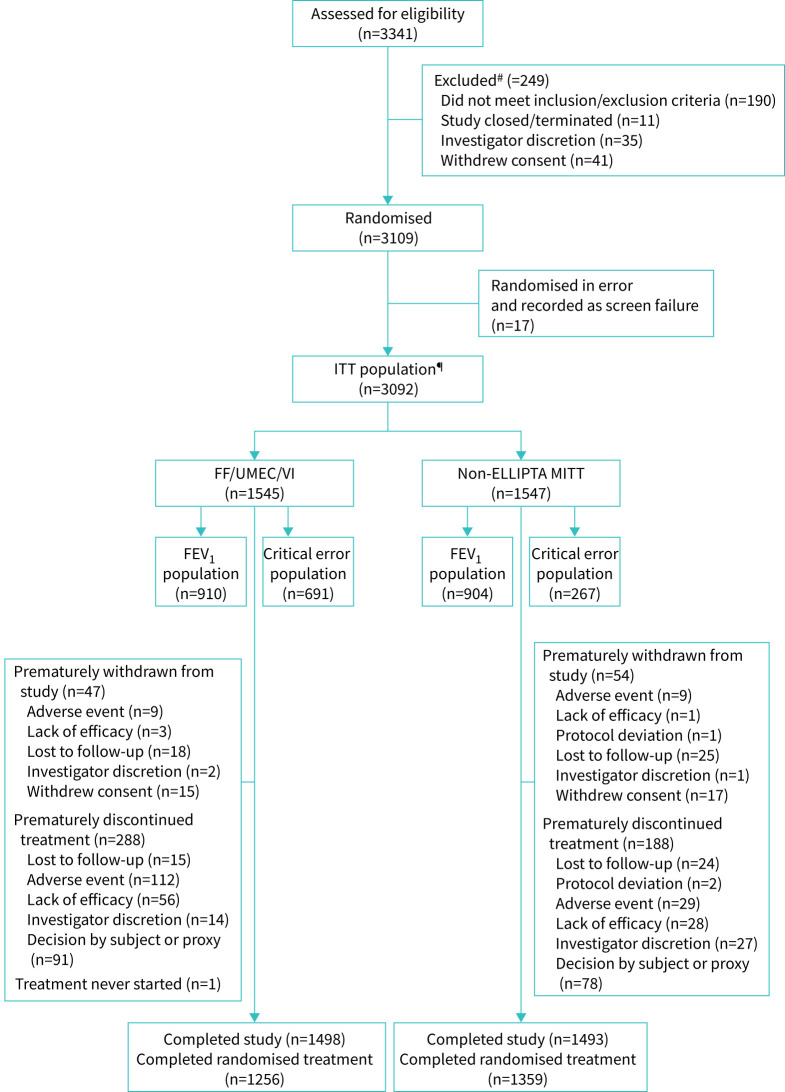

Of the 3109 patients who underwent randomisation, 3092 patients were included in the ITT population, and 1545 and 1547 patients were randomised to FF/UMEC/VI and non-ELLIPTA MITT, respectively. Within the ITT population, 910 patients randomised to FF/UMEC/VI and 904 patients randomised to non-ELLIPTA MITT were included in the FEV1 population. The critical-error population included 691 patients from the FF/UMEC/VI randomised ITT population and 267 patients from the non-ELLIPTA MITT randomised ITT population (figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Patient disposition. ITT: intention-to-treat; FF: fluticasone furoate; UMEC: umeclidinium; VI: vilanterol; MITT: multiple-inhaler triple therapy; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s. #: patients may have been excluded for multiple reasons. Patients who were randomised in error (n=17) are also identified as excluded due to eligibility. For those withdrawing from the study or randomised treatment only one primary reason is recorded. A patient completed randomised study treatment if they did not prematurely discontinue randomised study treatment and attended visit 2 (week 24). A patient who continued on all components of the randomised treatment and added additional medication to their maintenance treatment were considered as modifying their randomised treatment (intercurrent event), but were not considered to have prematurely discontinued from randomised treatment; ¶: one patient who withdrew >1 day after randomisation and did not take any study medication was included in the ITT population.

Overall, 2991 (97%) patients completed the trial, with 2615 (85%) patients completing the trial while receiving the treatment components to which they were randomised. During the first 8 weeks of treatment, rates of discontinuation of randomised treatment were higher with FF/UMEC/VI compared with non-ELLIPTA MITT, but were then comparable over the next 16 weeks (figure 2, supplementary figure S1). Demographic characteristics at screening were similar between the two treatment groups. Prior to study entry, 80% of patients were receiving triple therapy, 12% were receiving LAMA+LABA and 8% were receiving ICS+LABA maintenance therapy (table 1, supplementary table S2).

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics at screening (intention-to-treat population)

| FF/UMEC/VI | Non-ELLIPTA MITT | Total | |

| Patients | 1545 | 1547 | 3092 |

| Age years | 67.8±8.78 | 67.8±8.59 | 67.8±8.68 |

| Male | 837 (54) | 818 (53) | 1655 (54) |

| BMI kg·m−2 | 27.84±5.93 n=1536 |

28.05±6.05 n=1538 |

27.95±5.99 n=3074 |

| COPD exacerbation history in the prior 12 months | |||

| Moderate | |||

| 0 | 409 (26) | 405 (26) | 814 (26) |

| 1 | 639 (41) | 645 (42) | 1284 (42) |

| ≥2 | 497 (32) | 497 (32) | 994 (32) |

| Severe | |||

| 0 | 1349 (87) | 1361 (88) | 2710 (88) |

| 1 | 155 (10) | 139 (9) | 294 (10) |

| ≥2 | 41 (3) | 47 (3) | 88 (3) |

| Moderate/severe | |||

| 0 | 363 (23) | 361 (23) | 724 (23) |

| 1 | 615 (40) | 610 (39) | 1225 (40) |

| ≥2 | 567 (37) | 576 (37) | 1143 (37) |

| CAT score | 20.8±6.76 n=1543 |

20.5±6.62 n=1547 |

20.7±6.69 n=3090 |

| Peripheral blood eosinophil count# | n=605 | n=572 | n=1177 |

| <150 cells·µL−1 | 208 (34) | 223 (39) | 431 (37) |

| ≥150 cells·µL−1 | 397 (66) | 349 (61) | 746 (63) |

| Actual prior medication use strata | |||

| ICS+LAMA+LABA | 1226 (79) | 1235 (80) | 2461 (80) |

| ICS+LABA | 126 (8) | 126 (8) | 252 (8) |

| LABA+LAMA | 192 (12) | 183 (12) | 375 (12) |

| Missing¶ | 1 (<1) | 3 (<1) | 4 (<1) |

Data are presented as n, mean±sd or n (%). FF: fluticasone furoate; UMEC: umeclidinium; VI: vilanterol; MITT: multiple-inhaler triple therapy; BMI: body mass index; CAT: COPD Assessment Test; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; LAMA: long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist; LABA: long-acting β2-agonist. #: historical eosinophils were recorded as the most recent measure taken within the previous 36 months; ¶: stratum is considered missing if the combination of maintenance treatments taken in the 14 days prior to randomisation do not meet any of the three defined strata groups.

Primary and secondary efficacy analyses

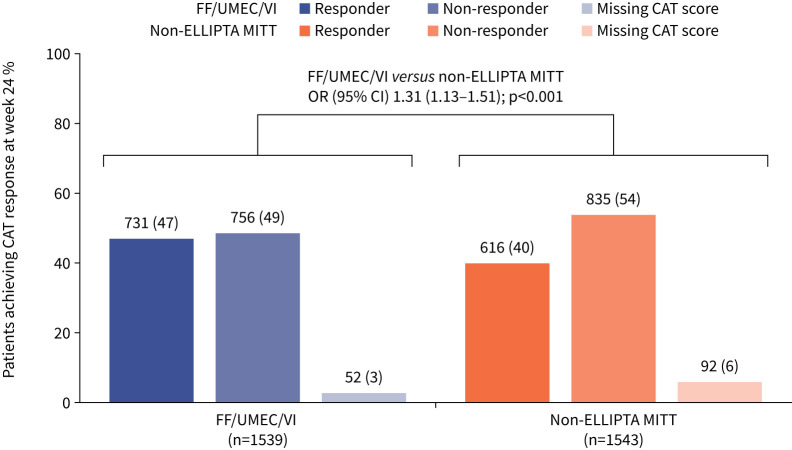

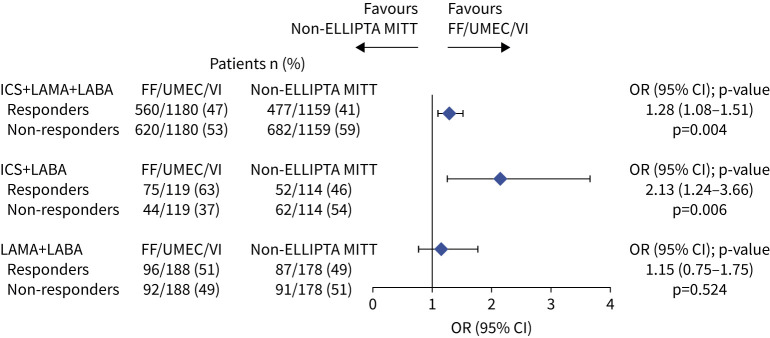

The odds of being a CAT responder at week 24 were significantly greater in patients receiving FF/UMEC/VI compared with those receiving non-ELLIPTA MITT (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.13–1.51; p<0.001) (figure 3). Mean±sd CAT score at week 24 was 18.0±8.0 and 19.1±7.9 in the FF/UMEC/VI and non-ELLIPTA MITT arms, respectively. Mean±sd change from baseline in CAT score at week 24 in FF/UMEC/VI and non-ELLIPTA MITT arms was −2.8±6.3 and −1.3±6.0, respectively, and median (interquartile range) change was −3.0 (−7.0–1.0) and −1.0 (−5.0–3.0), respectively. A significantly greater proportion of CAT responders were seen with FF/UMEC/VI over non-ELLIPTA MITT across all three supportive estimands (supplementary table S3). In patients receiving triple therapy prior to randomisation, the odds of being a CAT responder at week 24 were significantly greater with FF/UMEC/VI versus non-ELLIPTA MITT. The same was found for patients who had stepped up to triple therapy from ICS/LABA. In patients who had stepped up to triple therapy from LAMA+LABA, there was a numerical improvement in favour of FF/UMEC/VI, but this was not statistically significant (figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

Proportion of COPD Assessment Test (CAT) responders at week 24. Missing CAT scores were imputed using multiple imputation based on the randomised treatment arm characteristics assuming missing at random. Response is defined as a CAT score ≥2 units below baseline. Data labels above bars are n (%). FF: fluticasone furoate; UMEC: umeclidinium; VI: vilanterol; MITT: multiple-inhaler triple therapy.

FIGURE 4.

Proportion of COPD Assessment Test (CAT) responders at week 24 by prior medication strata. MITT: multiple-inhaler triple therapy; FF: fluticasone furoate; UMEC: umeclidinium; VI: vilanterol; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; LAMA: long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist; LABA: long-acting β2-agonist.

In the FEV1 population, the mean change from baseline in FEV1 (trough and non-trough values) at week 24 was significantly greater with FF/UMEC/VI versus non-ELLIPTA MITT (table 2).

TABLE 2.

Change from baseline in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and trough FEV1 at week 24

| FF/UMEC/VI population | Non-ELLIPTA MITT population | FF/UMEC/VI versus non-ELLIPTA MITT | |

| Patients | 910 | 904 | |

| FEV1# | |||

| Patients | 691 | 675 | |

| FEV1 mL | 1446 (1425–1467) | 1396 (1375–1418) | 50 (26–73); p<0.001 |

| FEV1 mL change from baseline | 77 (57–98) | 28 (6–49) | |

| Trough FEV1 | |||

| Patients | 301 | 292 | |

| FEV1 mL | 1498 (1462–1534) | 1445 (1404–1486) | 53 (9–96); p=0.017 |

| FEV1 mL change from baseline¶ | 100 (64–135) | 47 (6–88) |

Data are presented as n or least-squares mean (95% CI), unless otherwise stated. FF: fluticasone furoate; UMEC: umeclidinium; VI: vilanterol; MITT: multiple-inhaler triple therapy. #: data include both trough and non-trough values; ¶: patients with imputed FEV1, n=82 (FF/UMEC/VI), n=115 (non-ELLIPTA MITT). Trough FEV1 is defined as the FEV1 value recorded while patients have withheld COPD maintenance, short-acting β2-agonist and short-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist treatment. For COPD maintenance treatments taken once daily, FEV1 was considered as trough if the patient withheld the LABA and LAMA components of the maintenance treatment for ≥16 h. For COPD maintenance treatments taken twice daily, FEV1 was considered as trough if the patient withheld the LABA and LAMA components of the maintenance treatment for ≥8 h.

In the critical error population, there was no statistically significant difference in the percentage of patients with at least one critical error in inhalation technique at week 24 (6% in the FF/UMEC/VI group, 3% in the non-ELLIPTA MITT group; OR 1.99, 95% CI 0.87–4.53; p=0.103). Similar results were seen in the supportive estimand (supplementary table S4). Moderate/severe exacerbation rates are summarised in supplementary table S5.

Safety profile

Adverse events on randomised treatment occurred in 250 (16%) and 151 (10%) of patients receiving FF/UMEC/VI and non-ELLIPTA MITT, respectively (table 3). Of these, 9% in the FF/UMEC/VI arm and 3% in the non-ELLIPTA MITT arm were considered treatment-related in the opinion of the investigator. The only treatment-related adverse event occurring in >1% of patients was dyspnoea (supplementary table S6). On-randomised-treatment adverse events leading to study withdrawal, SAEs, fatal SAEs and serious AESIs are described in table 3. No new safety findings associated with the use of an ICS, a LAMA or a LABA in combination were seen. The on-study safety profile is described in supplementary table S7.

TABLE 3.

Incidence of on-randomised-treatment adverse events#

| FF/UMEC/VI | Non-ELLIPTA MITT | |||

| Patients n (%) | Events rate¶ (n) | Patients n (%) | Events rate¶ (n) | |

| Patients n | 1545 | 1547 | ||

| Total duration at risk patient-years | 636.7 | 685.8 | ||

| Any adverse event | 250 (16) | 590.6 (376) | 151 (10) | 322.2 (221) |

| Any treatment-related adverse event | 145 (9) | 329.8 (210) | 44 (3) | 77.3 (53) |

| Any adverse event leading to study withdrawal | 115 (7) | 279.6 (178) | 32 (2) | 70.0 (48) |

| Any SAE | 114 (7) | 257.6 (164) | 114 (7) | 255.2 (175) |

| Any treatment-related SAE | 13 (<1) | 20.4 (13) | 6 (<1) | 10.2 (7) |

| Any fatal SAE | 8 (<1) | 20.4 (13) | 8 (<1) | 23.3 (16) |

| Any treatment-related fatal SAE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serious AESIs | ||||

| Cardiovascular effects | 29 (2) | 55.0 (35) | 23 (1) | 39.4 (27) |

| Decreased BMD and associated fractures | 6 (<1) | 9.4 (6) | 4 (<1) | 7.3 (5) |

| Infective pneumonia | 27 (2) | 44.0 (28) | 32 (2) | 46.7 (32) |

| LRTI excluding infective pneumonia | 7 (<1) | 11.0 (7) | 10 (<1) | 14.6 (10) |

FF: fluticasone furoate; UMEC: umeclidinium; VI: vilanterol; MITT: multiple-inhaler triple therapy; SAE: serious adverse event; AESI: adverse event of special interest; BMD: bone mineral density; LRTI: lower respiratory tract infection. #: the recording of adverse events was limited to treatment-related adverse events, SAEs and adverse events leading to study treatment discontinuation or study withdrawal. Refer to supplementary tables S6 and S7 for further details; ¶: event rate per 1000 patient-years, calculated as number of events × 1000, divided by the total duration at risk.

Discussion

In this effectiveness trial, in patients with COPD in routine care settings, FF/UMEC/VI SITT resulted in a significantly greater proportion of patients gaining clinically meaningful improvements in health status compared with non-ELLIPTA MITT. In the FEV1 population, larger improvements in lung function were seen in patients receiving FF/UMEC/VI compared with those receiving non-ELLIPTA MITT. Similar benefits to health status were seen whether patients had previously been on triple therapy or were stepped up from dual therapy. These results provide compelling evidence of the benefits of FF/UMEC/VI SITT compared with non-ELLIPTA MITT on both health status and lung function in routine care and support simplification of COPD treatment regimens.

The significantly increased odds of achieving a clinically relevant CAT response with FF/UMEC/VI compared with non-ELLIPTA MITT reported in this study show that more patients can achieve an improvement in health status with single-inhaler FF/UMEC/VI versus multiple-inhaler regimens. Numerical differences in odds in favour of FF/UMEC/VI versus non-ELLIPTA MITT were seen regardless of therapy prior to study entry. The health status result is further supported by the spirometry data demonstrating significantly greater improvements in lung function in patients receiving FF/UMEC/VI compared with non-ELLIPTA MITT.

The proportion of patients making at least one critical error in inhalation technique at week 24 was low in both treatment arms, with no statistical difference between arms. To assess critical errors, patients had to be capable of withholding their COPD maintenance medication prior to the study visit, remember to do so and be using devices for which validated technique checklists were available. Only a small proportion of patients met these criteria, limiting our ability to analyse this end-point. The main reasons patients were not assessed were not omitting their morning dose, forgetting to bring their inhaler for the visit or using one or more devices without an assessment checklist. This last point largely explains the difference in population sizes, as all patients randomised to FF/UMEC/VI were using the ELLIPTA device, which had an assessment checklist, while only a subset of patients in the non-ELLIPTA MITT arm would have been using inhalers that all had a checklist. Furthermore, although participating clinicians were offered training on the assessment of inhaler technique, their ability to perform this accurately was not assessed. It is important to note that no selection of patients based on their inhaler technique was conducted at screening and this low critical error rate may be due to patients having had extensive previous experience of using their inhaler. The low critical error rate contrasts with other studies where error rates have generally been higher, although the ELLIPTA inhaler has previously been associated with low critical error rates compared to other inhalers in patients with COPD [10, 24, 25].

Discontinuation rates with randomised treatment were higher with FF/UMEC/VI compared with non-ELLIPTA MITT during the first 8 weeks of treatment, but were comparable over the next 16 weeks. This may be attributed to device familiarity. Patients randomised to the non-ELLIPTA MITT arm were likely to have been using their devices for many years, whereas patients randomised to FF/UMEC/VI would have been unfamiliar with the new ELLIPTA device and switched back to devices they were more familiar with or were more competent at using [26]. As the supportive estimands were consistent with the primary estimand, the difference in discontinuation rates within the first 8 weeks is unlikely to have affected the primary end-point. However, the significant effects observed for the primary end-point may not solely be a consequence of the single- versus multiple-inhaler regimen, but may also reflect the different molecules and frequency of dosing.

The incidence of treatment-related adverse events and adverse events leading to study withdrawal was higher in patients receiving FF/UMEC/VI compared with non-ELLIPTA MITT. This was not unexpected, as the open-label nature of the trial is likely to have introduced a potential bias in the reporting of more adverse events for a new treatment compared with standard-of-care options [27]. However, it should be noted that treatment-related adverse events and adverse events leading to study withdrawal occurred in <1% patients across most preferred terms. Overall, the incidence of SAEs and serious AESI, including cardiovascular effects and pneumonia serious AESIs, was low, and unsurprisingly, as all patients received triple therapy, was comparable across treatment arms. These data add confidence to the evidence from conventional RCTs that FF/UMEC/VI has a similar safety profile to non-ELLIPTA MITT, including when used by a much broader group of patients in the usual clinical care setting.

Effectiveness studies are designed to test the benefit and risk of interventions when used in routine care settings so that results generated are applicable and generalisable to usual clinical care populations. Compared with conventional RCTs, by design, effectiveness studies allow more heterogeneity in study elements such as patient populations, permitted additional therapeutics, delivery of care (e.g. general versus specialist services; involvement of respiratory nurses) and patterns of medication use. Consequently, effectiveness studies are at risk of being unable to detect small differences in outcomes due to the dilution of treatment effects that can occur in heterogeneous populations [18, 28]. Therefore, the magnitude of the differences in health status, supported by the lung function improvement observed in INTREPID is particularly meaningful.

Some limitations of this study should be considered. The minimal intervention design of INTREPID and the fact that study treatments were prescribed by the treating physician as per usual clinical practice meant that it was not possible to measure adherence. Similarly, additional measures that affect patients with COPD and that are modified by pharmacological treatments were not assessed in order to minimise intervention, including exercise tolerance and dyspnoea. The pragmatic nature of the study meant that it was simple in design, but the decision to only include two clinic visits meant that collection of data was restricted to just these two timepoints. More timepoints would have allowed a more complete picture of concordance with the various treatment regimens and more measurements of health status, but would have deviated more from usual care. The short length of the study combined with the study population size meant that exacerbation rate could not be compared; however, the annualised rates in both arms were low. Another potential limitation was that critical errors could only be assessed for devices for which an assessment form was available, and if patients remembered to withhold medication prior to the second assessment visit and bring their inhaler(s) with them. If this study was to be conducted again, we would reconsider the most effective way of assessing critical errors. Improvements in CAT score were observed in both treatment groups, which could be attributed to the open-label study design and a potential Hawthorne effect [29]; however, despite this, improvements in health status were observed in more patients randomised to FF/UMEC/VI compared with those randomised to non-ELLIPTA MITT.

The study has a number of key strengths. It is the first to evaluate SITT effectiveness over MITT in a usual clinical care setting in multiple countries. Previous studies have been double-blind, double-dummy studies that did not permit investigation of possible benefits such as improved adherence or reduced number of devices. INTREPID compared SITT with MITT without dummy placebo inhalers, and is therefore more reflective of the usual clinical care setting. The study entry criteria were primarily focused on physicians’ management strategies; any patients requiring triple therapy could be enrolled and the lack of strict inclusion/exclusion criteria ensured that patients enrolled were representative of patients with COPD requiring triple therapy in the general population. In addition, the study protocol permitted patients to change treatment regimen at the discretion of their physician, mirroring clinical practice. The study was designed to align the “usual care” to that of all countries in which the study was conducted, allowing examination of therapeutic effectiveness in accordance with the heterogeneity seen in everyday clinical practice and across healthcare systems in different countries. Complexity and interventions were kept to a minimum to avoid impact on physician and patient behaviour that may have influenced results. This means that although compromises were made to maintain the usual care setting, INTREPID still collected robust clinical data, allowing treatment superiority to be demonstrated.

In conclusion, single-inhaler FF/UMEC/VI therapy in a usual clinical care setting resulted in more patients achieving significant and clinically meaningful improvements in health status and significant improvements in lung function compared with non-ELLIPTA MITT, with a similar safety profile. The pragmatic design of INTREPID extends understanding of the effectiveness of FF/UMEC/VI beyond RCT settings. For the first time the benefits of SITT versus MITT in patients with highly symptomatic COPD have been confirmed in a routine care setting.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00950-2020.SUPPLEMENT (363.7KB, pdf)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jamila Astrom (Real World Study Delivery, GSK, Solna, Stockholm, Sweden) for leading the operational delivery of the study, and Dimitra Brintziki (GSK R&D, Brentford, UK) for her support with study reporting and analyses. The authors would also like to thank all patients for their participation in the INTREPID study. Editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, assembling figures, collating author comments, grammatical editing and referencing) was provided by Katie Baker and Philip Chapman at Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK, and was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK).

Footnotes

This article has supplementary material available from openres.ersjournals.com.

This study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with identifier number NCT03467425. Anonymised individual participant data and study documents can be requested for further research from www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

Author contributions: The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. All authors had full access to the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. David M.G. Halpin, Sally Worsley, Neil G. Snowise, Chris Compton, Dawn Midwinter, Afisi S. Ismaila, Elaine Irving and Maggie Tabberer contributed to study conception and design. David M.G. Halpin, Jose M. Marin, Janwillem W.H. Kocks and Kai-Michael Beeh contributed to the acquisition of data. David M.G. Halpin, Sally Worsley, Neil G. Snowise, Chris Compton, Dawn Midwinter, Afisi S. Ismaila, Janwillem W.H. Kocks, Jose M. Marin, Kai-Michael Beeh, Maggie Tabberer and Neil Martin contributed to data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to the writing and reviewing of the manuscript and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Conflict of interest: D.M.G. Halpin reports this study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and medical writing support was funded by GSK and personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees and nonfinancial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Chiesi and GSK, personal fees and nonfinancial support from Novartis, and personal fees from Pfizer and Sanofi, outside the submitted work. S. Worsley reports this study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and medical writing support was funded by GSK.

Conflict of interest: S. Worsley is an employee of and holds shares/options in GSK. A.S. Ismaila reports this study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and medical writing support was funded by GSK..

Conflict of interest: A.S. Ismaila is an employee of and holds shares/options in GSK, and is an unpaid, part-time professor at McMaster University.

Conflict of interest: M. Beeh reports this study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and medical writing support was funded by GSK, and personal and/or institutional compensation for clinical research, consulting or lecturing fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Novartis, Menarini/Berlin Chemie and Chiesi, consulting and lecturing fees from Sanofi and Elpen, and consulting fees from Sterna, outside the submitted work. D. Midwinter reports this study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and medical writing support was funded by GSK.

Conflict of interest: D. Midwinter is an employee of and holds shares/options in GSK.

Conflict of interest: J.W.H. Kocks reports this study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and medical writing support was funded by GSK, and grants, personal fees and nonfinancial support from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim and GSK, grants and personal fees from Chiesi Pharmaceuticals and Novartis, and grants from MundiPharma and TEVA, outside the submitted work. E. Irving reports this study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and medical writing support was funded by GSK.

Conflict of interest: E. Irving is an employee of and holds shares/options in GSK.

Conflict of interest: J.M. Marin reports this study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and medical writing support was funded by GSK, and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, speaker fees from and membership of an advisory committee for GSK, and speaker fees from Chiesi and Menarini, outside the submitted work. N. Martin reports this study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and medical writing support was funded by GSK.

Conflict of interest: N. Martin was an employee of GSK at the time of the study and holds shares/options in GSK. M. Tabberer reports this study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and medical writing support was funded by GSK.

Conflict of interest: M. Tabberer was an employee of GSK at the time of the study and holds stock in GSK. N.G. Snowise reports this study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and medical writing support was funded by GSK.

Conflict of interest: N.G. Snowise is a former employee of and holds shares/options in GSK, a shareholder in Vectura, and a visiting senior lecture at King's College London. C. Compton reports this study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and medical writing support was funded by GSK.

Conflict of interest: C. Compton is an employee of and holds shares/options in GSK.

Support statement: This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK study number CTT206854; NCT03467425). The funders of the study had a role in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry. ELLIPTA is owned by or licensed to the GSK Group of Companies.

References

- 1.Gaduzo S, McGovern V, Roberts J, et al. When to use single-inhaler triple therapy in COPD: a practical approach for primary care health care professionals. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2019; 14: 391–401. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S173901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu AP, Guérin A, Ponce de Leon D, et al. Therapy persistence and adherence in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: multiple versus single long-acting maintenance inhalers. J Med Econ 2011; 14: 486–496. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2011.594123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang S, King D, Rosen VM, et al. Impact of single combination inhaler versus multiple inhalers to deliver the same medications for patients with asthma or COPD: a systematic literature review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2020; 15: 417–438. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S234823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kocks JWH, Chrystyn H, van der Palen J, et al. Systematic review of association between critical errors in inhalation and health outcomes in asthma and COPD. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2018; 28: 43. doi: 10.1038/s41533-018-0110-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mäkelä MJ, Backer V, Hedegaard M, et al. Adherence to inhaled therapies, health outcomes and costs in patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med 2013; 107: 1481–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis H, Schroeder M, Gunsoy NB, et al. Evaluating patient preferences of maintenance therapy for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a discrete choice experiment in the UK, USA and German. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2020; 15: 595–604. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S221980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroeder M, Lewis H, Doll H, et al. P240 Evaluating patient preferences of maintenance therapy for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the UK: a discrete choice experiment. Thorax 2018; 73: Suppl. 4, A232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Palen J, Moeskops-van Beurden W, Dawson CM, et al. A randomized, open-label, single-visit, crossover study simulating triple-drug delivery with Ellipta compared with dual inhaler combinations in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2018; 13: 2515–2523. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S169060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melani AS, Bonavia M, Cilenti V, et al. Inhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease control. Respir Med 2011; 105: 930–938. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molimard M, Raherison C, Lignot S, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation and inhaler device handling: real-life assessment of 2935 patients. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1601794. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01794-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. 2020. Available from: http://goldcopd.org/

- 12.López-Campos JL, Quintana Gallego E, Carrasco Hernández L. Status of and strategies for improving adherence to COPD treatment. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2019; 14: 1503–1515. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S170848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipson DA, Barnacle H, Birk R, et al. FULFIL trial: once-daily triple therapy for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 196: 438–446. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0449OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipson DA, Barnhart F, Brealey N, et al. Once-daily single-inhaler triple versus dual therapy in patients with COPD. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1671–1680. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferguson GT, Brown N, Compton C, et al. Once-daily single-inhaler versus twice-daily multiple-inhaler triple therapy: two replicate trials in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 201: A4295.

- 16.Buhl R, Gessner C, Schuermann W, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily QVA149 compared with the free combination of once-daily tiotropium plus twice-daily formoterol in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD (QUANTIFY): a randomised, non-inferiority study. Thorax 2015; 70: 311–319. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halpin DM, Kerkhof M, Soriano JB, et al. Eligibility of real-life patients with COPD for inclusion in trials of inhaled long-acting bronchodilator therapy. Respir Res 2016; 17: 120. doi: 10.1186/s12931-016-0433-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patsopoulos NA. A pragmatic view on pragmatic trials. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2011; 13: 217–224. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.2/npatsopoulos [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Treweek S, Zwarenstein M. Making trials matter: pragmatic and explanatory trials and the problem of applicability. Trials 2009; 10: 37. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heddini A, Sundh J, Ekström M, et al. Effectiveness trials: critical data to help understand how respiratory medicines really work? Eur Clin Respir J 2019; 6: 1565804. doi: 10.1080/20018525.2019.1565804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vestbo J, Leather D, Diar Bakerly N, et al. Effectiveness of fluticasone furoate-vilanterol for COPD in clinical practice. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1253–1260. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Worsley S, Snowise N, Halpin DMG, et al. Clinical effectiveness of once-daily fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol in usual practice: the COPD INTREPID study design. ERJ Open Res 2019; 5: 00061-2019. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00061-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kon SS, Canavan JL, Jones SE, et al. Minimum clinically important difference for the COPD Assessment Test: a prospective analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2: 195–203. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70001-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collier D, Wielders P, van der Palen J, et al. Critical error rates with the ELLIPTA inhaler compared with other dry-powder inhalers in patients with COPD: an open-label, low-intervention clinical study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 199: A2437. [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Palen J, Thomas M, Chrystyn H, et al. A randomised open-label cross-over study of inhaler errors, preference and time to achieve correct inhaler use in patients with COPD or asthma: comparison of Ellipta with other inhaler devices. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2016; 26: 16079. doi: 10.1038/npjpcrm.2016.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bjermer L. The importance of continuity in inhaler device choice for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration 2014; 88: 346–352. doi: 10.1159/000363771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beeh K, Beier J, Donohue J. Clinical trial design in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current perspectives and considerations with regard to blinding of tiotropium. Respir Res 2012; 13: 52. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-13-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ford I, Norrie J. Pragmatic trials. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 454–463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1510059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pate A, Barrowman M, Webb D, et al. Study investigating the generalisability of a COPD trial based in primary care (Salford Lung Study) and the presence of a Hawthorne effect. BMJ Open Respir Res 2018; 5: e000339. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2018-000339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00950-2020.SUPPLEMENT (363.7KB, pdf)