Abstract

Participation in and opportunities for physical activity (PA) and sports (PA inclusively hereafter) are known to vary across individuals with different social positions. Intersectionality theory may help us to better understand the complex processes of multiple interlocking systems of oppression and privilege shaped by intersections of individuals’ social categories. The objectives of this systematic scoping review were (1) to summarize the findings of articles examining PA claimed operationalization of intersectionality and (2) to identify the scope and gaps pertaining to the operationalization of intersectionality in PA research. A search was conducted in September 2019 in seven electronic databases (e.g., SPORTDiscus, Scopus, Web of Science) for relevant research articles written in English. Key search terms included “intersectionality” AND “physical activity” OR “sport”. Database searches, data screening and extraction, and narrative synthesis were conducted between September 2019 and May 2020. Of 16564 articles identified, 45 articles were included in this review. The majority of included articles used qualitative methods (n = 41), with two quantitative and two mixed-methods articles. The most frequently observed intersectional social position was sex/gender + race/ethnicity (n = 11), followed by sex/gender + race/ethnicity + sexuality (n = 6) and sex/gender + race/ethnicity + religion (n = 6). Most qualitative studies (n = 38) explicitly claimed operationalization of intersectionality as a key theoretical framework, and over half of these studies (n = 27) implicitly used intra-categorical intersectionality. Two quantitative studies were identified which examined a number of intersections simultaneously using inter-categorical intersectionality. Complex processes of individual and social-structural level factors that drive inequalities in PA opportunities and participation could be better elucidated with the operationalization of intersectionality theory. Intersectionality theory may serve as a useful framework in both qualitative and quantitative investigations. Advancement in quantitative intersectionality is critical in order to produce knowledge that could inform more inclusive PA promotion efforts.

Keywords: Gender, Racism, Sexism, Exercise, Quantitative intersectionality

Highlights

-

•

Intra-categorical intersectionality is commonly used in most qualitative investigations.

-

•

Inter-categorical intersectionality is used in quantitative research.

-

•

Utilizing multiplicative statistical models may advance quantitative intersectionality.

-

•

Investigating varying axes of marginalization beyond sex/gender + race/ethnicity is important.

-

•

Intersectionality is useful in better understanding disparities in physical activity.

1. Introduction

Among many areas of social participation, involvement in physical activity (PA), including sports, (PA inclusively hereafter) is advantageous for both individuals and societies. Specifically, regular participation in PA improves physical, psychological, and social well-being (Warburton & Bredin, 2017) while also promoting social cohesion (Government of Canada, 2000). Given these benefits, it is imperative that every individual has access to quality PA opportunities and participation. However, unequal opportunities and participation in PA are well noted across individuals with membership in different category-based groups. For example, it is suggested that women and girls, people with disabilities, newcomers, people with lower income or education levels, older adults, and members of gender and sexual minority communities participate in PA at far lower rates than the modal (male, able-bodied, long-settled, mid to high-socioeconomic status/degreed, young-to middle-aged, heterosexual and/or cisgender) population in North American and European societies (Aubert et al., 2018; Bauman et al., 2012; Cragg, Costas-Bradstreet, Arkell, & Lofstrom, 2016; Hosseinpoor et al., 2012).

In the context of Canada as an example, Sport Canada suggested in their 2016 policy document that barriers to sport participation among the members of underrepresented groups are “likely the same” (Cragg et al., 2016). However, an increasing number of studies appear to suggest the otherwise, particularly using qualitative methods (Government of Canada, 2000; Blodgett, Ge, Schinke, & McGannon, 2017; Withycombe, 2011; Herrick & Duncan, 2018). For instance, compounded by heteronormativity and middle-class normativity, whiteness has been found to prevail explicitly and implicitly in collegiate athletic administration and coaching (Borland & Bruening, 2010; Larsen, Fisher, & Moret, 2019; McDowell & Carter-Francique, 2017; Rankin-Wright, Hylton, & Norman, 2020) as well as in recreational sporting contexts, such as roller derby (Pavlidis & Fullagar, 2013), stickball (Welch, Siegele, Smith, & Hardin, 2019), or rugby (Adjepong, 2017) in a number of qualitative investigations. Though quantitative investigation on the intersectionality of PA opportunities and participation is scarce, a recent investigation (Abichahine & Veenstra, 2017) examining leisure-based PA among a large sample of Canadian adults found that taking a multiplicative statistical approach grounded in intersectionality is superior to a traditional additive statistical approach in clarifying social inequalities in PA opportunities and participation. The authors of this investigation (Abichahine & Veenstra, 2017) also suggested that incorporating intersectional analyses into quantitative research may advance our understanding of inequalities that exist in PA opportunities and participation across individuals with diverse social identities.

Intersectionality, first coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw (Crenshaw, 1989), is known as a powerful theoretical framework for examining how interlocking systems of power manifest in individuals' experiences and studying how these systems produce inequalities based on individuals' social positioning (Collins, 2015; Crenshaw, 1991). Intersectionality theory posits that diverse patterns of identity-based inequality, such as sexism, racism, ableism and nationalism are mutually constituted (Collins, 1993). Due to the entanglement of these domains of inequalities, individuals' experience often manifests at varying intersections of sex/gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and other identity-based variables (Collins, 1993). Given these, taking an intersectional lens may help to explain why PA opportunities and participation in multi-marginalized groups continue to lag compared to their counterparts who are dominantly situated. In particular, in the sport setting where whiteness and maleness are prevalent (Ray, 2014), Black women's experience of inequality in sport can be clearly articulated through an intersectional lens rather than taking a single-identity approach (Crenshaw, 1989).

Though intersectionality is gaining momentum in different disciplines, particularly in public health (Bauer, 2014) and psychology (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016), measuring, analyzing, and interpreting intersectionality is far from straightforward due to the construct's complexity (Bowleg, 2008; Flintoff, Fitzgerald, & Scraton, 2008). There are primarily three approaches within the intersectionality framework: anti-categorical, intra-categorical, and inter-categorical (McCall, 2005). Anti-categorical intersectionality denotes an approach that deconstructs analytical categories of social position, asserting that using fixed categories is too simplistic to capture the complexity of individuals' experiences. Intra-categorical intersectionality refers to an approach that focuses on one specific group with more than two social categories (e.g., Black women) with no comparison group (e.g., Black men or white women). Conversely, the inter-categorical intersectionality approach considers the impact of multiple intersections between different groups.

In the realm of PA research, intersectionality approaches have shed light on the interconnectedness of different social categories in shaping one's opportunities and participation in PA, predominantly using qualitative methods. Quantitative intersectionality research is emerging in recent years; however, it is a largely unexplored paradigm in PA research. Therefore, the objectives of this systematic scoping review were (1) to summarize the findings of articles examining PA claimed operationalization of intersectionality and (2) to identify the scope and gaps pertaining to the operationalization of intersectionality theory in PA research.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Review protocol

This review followed the methodological framework (Peters et al., 2015) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) reporting guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018). We took the following steps: (1) discover research questions; (2) determine relevant articles from a wide range of literature; (3) screen and select appropriate articles for final inclusion; (4) extract and chart the data based on key concepts; and (5) collate, summarize, disseminate the findings, and make recommendations for future research (Peters et al., 2015).

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Due to the exploratory nature of this scoping review, a liberal approach was taken in determining inclusion criteria. Specifically, articles were included based on the following criteria: (1) explicitly claimed operationalization of intersectionality, (2) written in English, and (3) published in peer-reviewed journals. All types of research methods (i.e., qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods) were considered with no limit on publication year. To be classified as explicitly claiming operationalization of intersectionality, studies had to not only mention intersectionality as a guiding theory or framework but also investigate an intersection of at least two social categories simultaneously as a key participant characteristic (e.g., sex/gender and race/ethnicity, sex/gender and disability, race/ethnicity and class). Eligible PA domains included, but were not limited to, walking, leisure-time PA, active travel, active leisure, aerobic exercises, muscle toning exercises, sport, dance, and physical education classes.

2.3. Information sources and search procedures

Searches were conducted with pre-determined search terms (i.e., “Intersectionality” AND “Physical activity” OR “Sport”) in the following key databases that are relevant to the review topic: Social Science @ ProQuest (ProQuest; 1991-), ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global (ProQuest; 1991-), Web of Science (Clarivate; 2006-), SPORTDiscus (EBSCOHost; 2010-), Global Health (Ovid; 1973-), Gender Studies Database (EBSCOHost; 2003-), and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health ([CINAHL] EBSCOHost; 2016-). These databases were searched for relevant articles between October 7th and 10th in 2019. Detailed information on search databases, search terms for each database, and numbers of duplicates and articles yielded are indicated in Appendix A, Appendix A. Covidence (www.covidence.org), a web-based software program, was used for screening research articles.

2.4. Selection of sources of evidence

The research team for the screening process consisted of one primary investigator (EL), two graduate students (EJ and HL), and two undergraduate assistants (KJ and XD). Before the screening, all screeners acquainted themselves with the objectives of this review and inclusion criteria for eligible articles. To ensure consistency across screeners, a series of training sessions was conducted before and during each level of screening (i.e., titles and abstracts, full-texts). Specifically, all five screeners reviewed 10 articles simultaneously during the first training session prior to the Level 1 screening (titles and abstracts). During the Level 1 screening, all five screeners reviewed articles independently and recorded whether an article should be included or excluded. During the Level 2 screening (full-texts), two pairs of research assistants screened and validated articles (each pair consisted of one reviewer and one verifier) to ensure the rigour of the screening process. Articles were first independently screened and then each pair met to compare results and resolve conflicts. If conflicts remain unresolved between two screeners, the primary investigator reviewed the articles in question and supported consensus. The research team also held bi-weekly meetings between October 2019 to March 2020 to provide the team members with the opportunity to discuss uncertainties that arose during the screening process. A fair level of inter-rater reliability was achieved between two screeners of each pair during Level 2 ( = 0.29). Prior to the data extraction, theses/dissertations (n = 143) were further excluded due to the challenges identified during the pilot data extraction process. Specifically, a large number of initially identified theses/dissertations did not examine PA as the main topic of their investigation. We also found that there were some overlapping publications under the same author in different formatting (i.e., original articles and theses/dissertations); therefore, we retained an original article published in a peer-reviewed journal if a thesis/dissertation by the same author on the same topic was captured in our search. Articles that are systematic reviews, commentaries, or conceptual in nature (n = 33) were also excluded because we were interested in summarizing research findings based on original investigations; however, articles other than original investigations were used to guide our discussion.

2.5. Data extracting process and key variables

Data extraction was conducted using two different data extraction forms (i.e., qualitative and quantitative) in Microsoft Excel developed by the primary investigator. Data were individually extracted for study description (i.e., author, publication year, geographic location, methods, sample characteristics, theory used), key intersectionality-related variables used (i.e., sex/gender, race/ethnicity, income, education, occupation, sexuality, religion, body shape/size/image, [im]migration status, English as an Additional Language (EAL) status, disability, age, and nationality), domain of PA (e.g., sport, habitual PA), level of engagement studied (e.g., elite athletes, recreational), role of participants described in studies (e.g., consumer, coach/teacher, participant), and the summary of findings. Two research assistants extracted data then verified by the other two research assistants. Extracted data from the articles included in this review are described in Appendix A, Appendix A (qualitative articles) and Appendix A, Appendix A (quantitative articles). Only qualitative evidence is extracted and described in Appendix A, Appendix A from two mixed-methods articles.

2.6. Synthesis of results

The general study characteristics of the included articles were categorized then analyzed separately by geographical locations, main domains of investigation, levels of engagement, and roles in participation. The frequency of various social category variables and their intersections investigated across the articles were calculated. For the qualitative evidence, theory used (e.g., intersectionality, Black feminist theory), data collection and analysis, and intersectionality approach used (i.e., inter-, intra-, or anti-categorical) were described. For the quantitative evidence, theory used, study design, and statistical data collection and analysis, and intersectionality approaches were described. For qualitative articles, data analysis was conducted by a research assistant then verified by the primary investigator.

Following initial read-throughs of the included articles, findings were summarized by qualitative (Appendix A, Appendix A) and quantitative methods (Appendix A, Appendix A), given the heterogeneity observed in the operationalization of intersectionality theory (i.e., primarily intra-categorical vs inter-categorical) between the two methods. For qualitative evidence, a deductive content analysis (White & Marsh, 2006) was performed on the extracted contents based on the following steps: (1) the extracted data along with full-text articles were read thoroughly and notes were made in the text using open coding (Kardorff & Steink, 2004); (2) frequency analysis of key variables was conducted; (3) most to least frequently observed intersections of social categories were ranked; and (4) frequency of intra- and inter-categorical approaches was determined. For quantitative evidence, key variables and relationships examined (i.e., exposure, outcome) and statistical analytic techniques and findings were extracted on the Excel sheet first by a research assistant then verified by the primary investigator.

3. Results

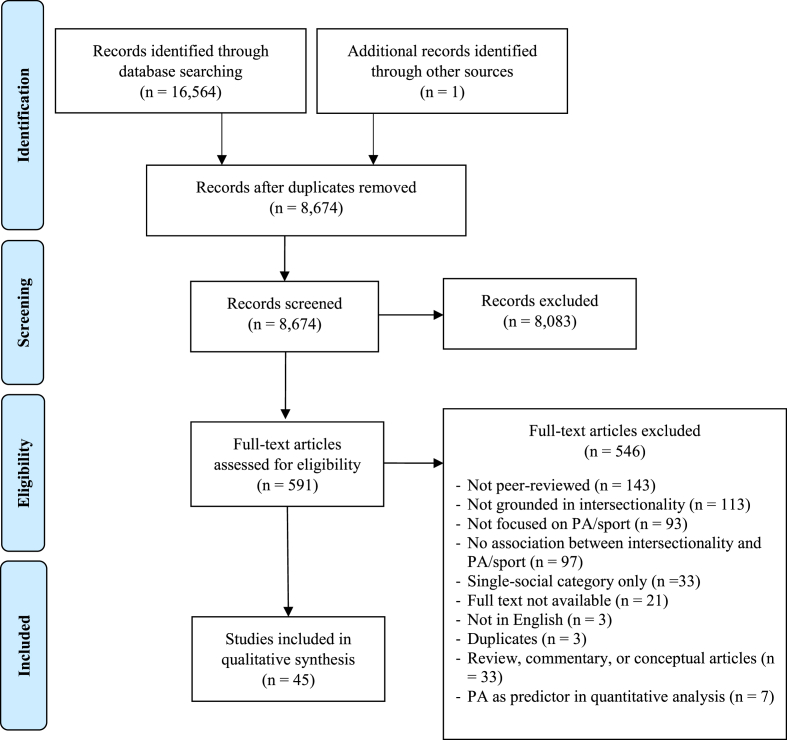

A PRISMA-ScR flow chart was employed for the search and selection process (Fig. 1). The search of seven databases yielded 16564 potential articles and one additional article was identified by primary investigator (EL) (total N = 16565). After removing duplicates (n = 7891) and irrelevant articles (n = 8629) based on the aforementioned eligibility criteria (i.e., claimed operationalization of intersectionality, written in English, published in peer-reviewed journals), a total of 45 articles were selected for evidence synthesis. (Full bibliography of the included articles is available in Appendix A).

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews flow chart.

3.1. General descriptive characteristics (N = 45)

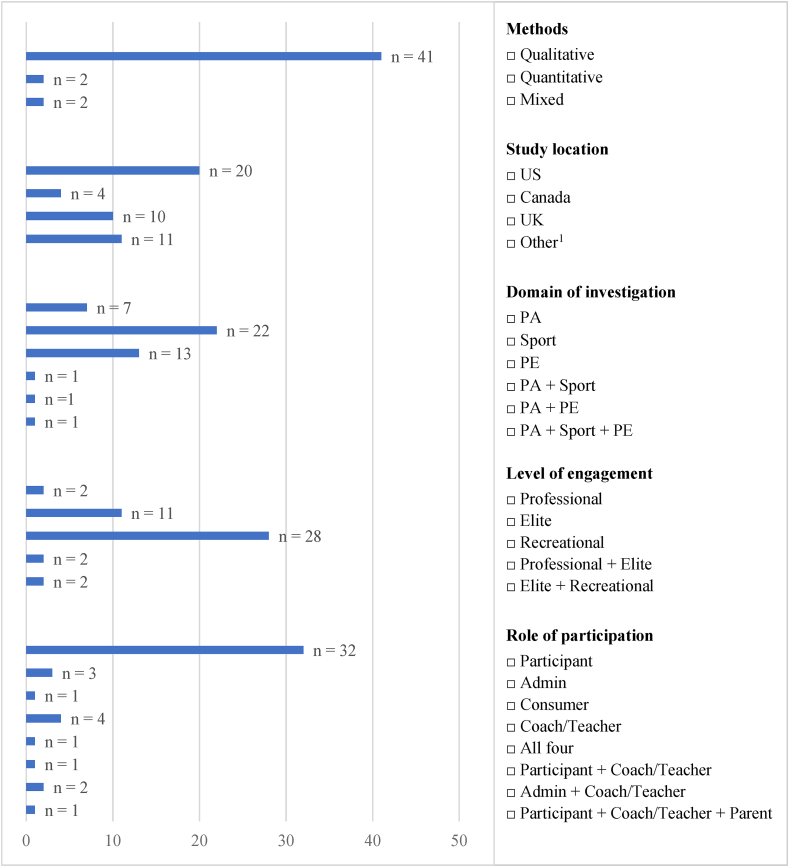

Of 45 articles, 41 were qualitative and two articles were quantitative. Two articles used mixed-methods but were included in qualitative evidence because the quantitative evidence provided in these articles was only descriptive. As outlined in Fig. 2, a total of 20 articles reported on research conducted in the US, followed by the UK (n = 10) and Canada (n = 4) in frequency. Most articles focused on one domain of investigation, either sport (n = 22), physical education in K-12 schools (n = 13), habitual PA (n = 7), while three articles spanned two or all three of these domains. A total of 28 articles examined PA at the recreational level, followed by elite (n = 11) and professional (e.g., coaching or school [n = 2]) levels. The main PA role reported on by almost three-quarters of the articles was participant (i.e., athlete or student [n = 32]), while seven articles reported on research with coaches/teachers (n = 4) or sport organization administrators (n = 3).

Fig. 2.

Study characteristics (N = 45). 1Other countries included Australia (n = 3); South Africa (n = 1); Denmark (n = 2); Sweden (n = 1); Norway (n = 2); Netherlands (n = 1); South Korea (n = 1).

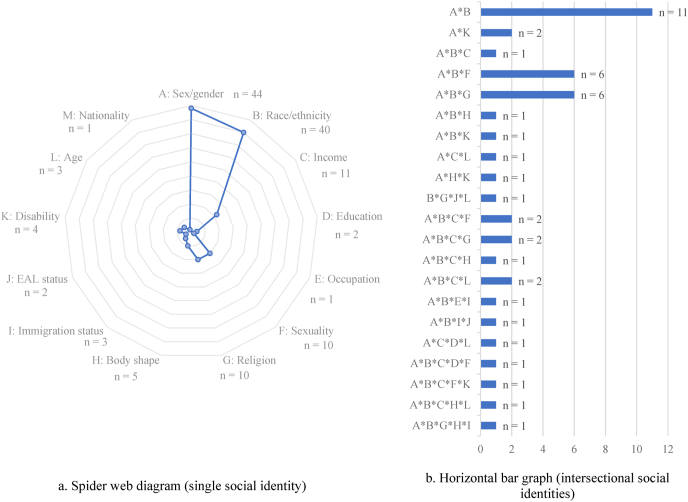

The included articles examined the relationships among multiple combinations of social category and PA. As illustrated in Fig. 3, sex/gender (n = 44) and race/ethnicity (n = 40) were the most frequently observed social categories, followed by income (n = 11), sexuality (n = 10) and religion (n = 10) while nationality (n = 1) and occupation (n = 1) were the least frequently observed social categories, followed by education (n = 2) and English as an additional language (EAL) status (n = 2). The most commonly observed intersection was sex/gender + race/ethnicity (n = 11), followed by sex/gender + race/ethnicity + sexuality (n = 6) or sex/gender + race/ethnicity + religion (n = 6). Other intersections observed were identified in fewer than three articles (Fig. 3). Due to heterogeneity, methodological scope and summary were synthesized by research methods (i.e., qualitative and quantitative) separately.

Fig. 3.

Intersections of social identity variables observed in the included article (N = 45).

EAL: English as an additional language.

a. Spider web digram: This diagram represents the number of articles that have included each social identity; therefore, number of articles across different social identities are not mutually exclusive. For example, 44 articles included sex/gender while 40 articles also included race/ethnicity.

b. Horizontal bar graph: This graph represents the number of articles that have included intersections of social identities. For example, the aggregation of different combinations of intersection examined make up a total of 45 articles. A total of 13 articles examined the intersection of two social identities: A*B (n = 11) indicates that 11 articles examined the intersection between sex/gender and race/ethnicity while A*K (n = 2) indicates that two articles examined the intersection between sex/gender and the disability status. A total of 17 articles examined the intersection between three social identities, 11 articles examined the intersection between four social identities, and the rest four studies examined the intersection between four social identities.

3.2. Methodological scope and summary of qualitative evidence (n = 43)

Of the 41 qualitative articles and two mixed-methods articles, 38 articles adopted intersectionality as a guiding theory or framework while four articles utilized intersectionality along with other theories, including feminist post-structuralism/decolonial theory, feminist epistemology, Black feminism, and Indigenous feminism. Most qualitative articles used more than one data collection method. The most common qualitative data collection method used to operationalize intersectionality theory was interviewing (n = 35 [whether in-depth, semi-structured, or unstructured]). Direct observation (n = 8), questionnaire (n = 3), field work (n = 6), focus group (n = 2), and/or photovoice (n = 1) were also used along with interviewing. Other types of method used in isolation included field work (n = 1), participatory action research (n = 1), or questionnaire (n = 1) with focus group (n = 1). Several data analysis techniques were employed including thematic analysis (n = 20), media coverage analysis (n = 2), content analysis (n = 2), discourse analysis (n = 3), interpretative phenomenological analysis (n = 3), or narrative analysis (n = 4).

At the intersection between sex/gender + race/ethnicity, most qualitative evidence has centred maleness (masculinity) and whiteness when investigating unequal opportunities and participation in PA among minoritized groups, using the experiences of white and men athletes as a norm (Benn et al., 2011; Dlugonski et al., 2017; Dworkin et al., 2017; Ekholm et al., 2019; Flintoff, 2014; Forbes, 2018; Kardorff & Steink, 2004; White & Marsh, 2006). For example, in elite collegiate women's basketball departments (e.g., coaches or directors) at the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division 1, Black women were more likely to be disadvantaged in being promoted to a higher position in collegiate athletic coaching compared to their white men and women counterparts (Larsen et al., 2019). The dominance of whiteness in PA contexts also appeared to label minoritized individuals as ‘others’ in order to maintain the interlocking systems of oppression associated with gender and race, while normalizing whiteness, particularly in sport (Benn et al., 2011; Dworkin et al., 2017; Ekholm et al., 2019) Idealized white masculinity also perpetuated a hierarchy that stereotypes racialized ethnic minorities (e.g., Asian) as ‘gay,’ ‘working-class,’ ‘aliens,’ or ‘forever-foreigners’ and positioning these ‘others’ in a lower rank of the social hierarchy in comparison with white men in the PA context in the US (Lee, 2016).

Compounded with maleness and whiteness, heteronormativity also prevailed explicitly and implicitly in PA contexts at the intersection of sex/gender + race/ethnicity + sexual orientation. For example, Asian British women who play football were perceived as a tomboy by others because football is known as predominantly men's sport (Ratna, 2013). In the media, the hyper-sexualization of Black woman athletes was also often reproduced (Litchfield et al., 2018; Withycombe, 2011) at the same time as these athletes' athletic abilities and successes are disregarded (Barak et al., 2018; Withycombe, 2011). The stereotyping of white women athletes as heterosexual and feminine impacted them considerably, coercing a performance of ‘female-ness,’ that is “not too muscular, feminine but not girly, heterosexual but not sexually active" (Barak et al., 2018), regardless of their social identities (Adjepong, 2017; Barak et al., 2018). Such phenomena are also noted among LGBTQ+ (or gender and sexual minority) individuals participating in recreational PA (Herrick & Duncan, 2018). For example, LGBTQ + individuals reported that gender identities (e.g., women, men, transgender) and gender expressions (e.g., gesture, language) are negatively perceived by their peers and acted as a barrier to participating in PA. Also, change rooms were not considered as safe in public fitness centres or gyms for transgender individuals as they are forced to choose between two binary choices that may not be accurate or welcoming (Herrick & Duncan, 2018).

Religion was also an important addition to the sex/gender + race/ethnicity equation. Specifically, religion, combined with gender and racial minority statuses, acted as a barrier to PA among South Asian and Muslim girls (Benn et al., 2011; Dagkas & Hunter, 2015; Ratna, 2011; Stride, 2014, 2016; With-Nielsen & Pfister, 2011). Due to culturally embodied and religious beliefs in how women should be, the intersection of sex/gender + race/ethnicity + religion produced unique challenges and opportunities that appear to influence their participation in PA “in complex, fluid, and multiple ways" (Stride, 2016). For example, Muslim girls challenged to navigate their Muslim identity in PA; the settings where masculinity is dominated largely conflicts with expectations and beliefs demanded by their culture and religion (Benn et al., 2011; With-Nielsen & Pfister, 2011). Racialized sport participants are also considered ‘strangers’ or ‘outsiders’ who are unable to assimilate into American sport culture (Lee, 2016). Muslim girls in Norwegian schools were treated as the ‘other’ in physical education (PE) classes because they are seen to be passive, uninterested in co-ed, lacking in physical ability due to their sex, ethnicity, and religion (Walseth, 2015).

In examining the intersection of social categories and its influence on PA, 27 articles took an intra-categorical intersectionality approach, studying experiences at a single intersection of multiple social categories. Studies taking the intra-categorical approach focused on one particular intersection (e.g., Black women or Muslim women) in the recruitment of participants and the analysis/interpretation of their experiences without any comparison groups. For example, Dlugonski et al.(2017) examined motivation for participating in and barriers to PA among low-income Black women who are positioned at the intersection of three social categories (i.e., sex/gender + race/ethnicity + social class) without any comparison groups (e.g., high-income Black women, low-income white women, etc.). Almost one-third of the articles (n = 16) employed an inter-categorical intersectionality approach. These articles recruited individuals from diverse social groups and conducted comparative analysis and interpretation across different social strata. For instance, Barak and colleagues (2018) investigated women collegiate athletes’ self-representations at varying intersections of sex/gender (i.e., women), race/ethnicity (i.e., Black, white, Asian [-American], or Hispanic), and sexual orientation (i.e., heterosexual, queer, bisexual).

3.3. Methodological scope and summary of quantitative evidence (n = 2)

Overall, only two quantitative articles investigated intersectional correlates of PA while explicitly claimed operationalization of intersectionality theory (Abichahine & Veenstra, 2017; Lee et al., 2020). Two mixed-methods articles did not provide quantitative evidence with appropriate statistical testing (Carter-Francique, 2011; Dlugonski et al., 2017). Both quantitative articles used the cross-sectional design and were based on self-reported, national datasets with large sample sizes. These articles showed that varying social categories intersect and, together, contribute to creating inequality in PA (Abichahine & Veenstra, 2017; Lee et al., 2020).

One study was conducted among 149,574 Canadian adults (Abichahine & Veenstra, 2017) based on inter-categorical intersectionality (as above, comparing across multiple categories within more than two social identity strata) including various combinations of gender, race, socioeconomic status (i.e., income, education level), and sexual orientation. This study applied two-stage analytic strategies to analyze intersectionality quantitatively: additive and multiplicative models (Abichahine & Veenstra, 2017). Additive models focused on investigating the main effect of each social category, while multiplicative models addressed the interactive effects (i.e., moderation) of multiple social categories (Abichahine & Veenstra, 2017). The authors concluded that multiplicative models better predict PA participation than additive models, further supporting intersectional inequalities that exist in PA participation and highlighting the importance of using multiplicative models grounded in intersectionality in future investigations (Abichahine & Veenstra, 2017). Applying multiplicative models, this study examined four-way interactions between gender, race, sexual orientation, and income or education. Though none of the two four-way interactions tested in this study were statistically significant, three-way interaction terms between gender race income as well as gender education sexual orientation enhanced the predictive probabilities of PA participation compared to additive models. Specifically, visible minority women, regardless of income, were the least likely while white and visible minority men with high income were the most likely to be physically active than their respective counterparts. In addition, sexual orientation (i.e., heterosexual, lesbian, gay, or bisexual) was associated with being physically active, particularly among women who identified themselves as lesbian or bisexual and with no post-secondary education, while gay or bisexual men with post-secondary education were less likely to be physically active than their respective counterparts.

Another article (Lee et al., 2020) conducted among 372,433 South Korean adolescents examined intersectional correlates of meeting the PA recommendation (i.e., 60 min/d of moderate-to vigorous-intensity PA). With sex as the centre variable of analyses, participants were stratified into 2 2 or 2 3 intersectional groups by categorizing individuals into different strata of sex (i.e., woman and man) and social class (i.e., family economic status, parental education level, and academic performance) categories. Compared to female adolescents, male adolescents were consistently associated with meeting the PA recommendation, regardless of social class. In the 2 2 or 2 3 intersectionality models, social class appeared to be not significant or even detrimental to meeting PA recommendation among female adolescents, except for mother's education. Specifically, female adolescents with a mother with post-secondary education were more likely to meet the PA recommendation than those with a mother with a high school diploma or lower (Lee et al., 2020).

4. Discussion

This systematic scoping review aimed to summarize the evidence on intersectionality in PA and to identify the scope of and gaps within the relevant literature. We found 45 articles that explicitly claimed operationalization of intersectionality and examined how varying intersections of social categories impact individuals’ opportunities and participation in PA. The included articles explicitly claimed operationalization of intersectionality to better understand unequal opportunities and participation in PA in different locations, domains, engagement levels, and participating roles using a variety of methods. The most common method used to study intersectionality in PA was qualitative (96%) and almost all articles included sex/gender as one of the intersectional variables except one article. In every article, sex/gender was constructed as static, not fluid, and as a binary (i.e., a simple duality of cisgender men and cisgender women). Sport was the most common domain of investigation over habitual PA or physical education at schools, while participant (i.e., not coach) was the main form of participation at the recreational level. Most qualitative articles utilized intra-categorical intersectionality while two quantitative articles utilized inter-categorical intersectionality. Qualitative articles mostly employed interviews and/or direct observation while using intersectionality as a guiding theory for study design and data collection, analysis, and interpretation. The two quantitative articles used self-reported questionnaire data and took different statistical approaches including additive, multiplicative, and/or stratified statistical models.

This review identified that almost all articles focused on investigating PA opportunities and participation at the intersections between sex/gender + race/ethnicity. For example, most qualitative articles highlighted the invisibility or negative experiences of Black or ethnic minority women (e.g., South Asian girls, Muslim girls, Lebanese-Canadian women, or Latina) when participating in PA. As noted in previous literature in social epidemiology (Mena & Bolte, 2019) and sport sociology (Flintoff et al., 2008), this sex/gender + race/ethnicity dominance is likely because intersectionality theory is rooted in Black feminism and unbalanced power relations can be best explained when the intersection between sex/gender + race/ethnicity is considered (Crenshaw, 1989). Specifically, experiences of Black women can be better articulated with the intersection of both categories than either race- or gender-only theory (Collins, 2006). Additionally, sport is a unique context where two common phenomena – gender stereotyping femininity and racial stereotyping - are amplified (Alley & Hicks, 2005, Cooky et al., 2010, Dworkin et al., 2017). This was evident in the articles included in this review. For instance, white women athletes were experiencing identity negotiation due to sexist notions of beauty while Black women athletes were masculinized, hypersexualized or asexualized, and vilified with hypervisibility or invisibility that persist in sport (Barak et al., 2018; Cooky et al., 2010; Litchfield et al., 2018; Mowatt, French, & Malebranche, 2013).

The findings of qualitative evidence largely support the literature on PA research claimed operationalization of intersectionality. Whiteness, compounded with masculinity and heterosexuality, preserves the social privilege and dominance of white, straight, and middle-class men and boys in the PA context (Cheeks & Carter-Francique, 2015; Dagkas, 2016; Davidson, 2014; King & McDonald, 2007; Mowatt et al., 2013; Roberts, 2009; Tredway, 2019) because this intersectional positioning was considered to be “natural, normal, and/or inevitable” (McDonald, 2009) therein. Meanwhile, the bodies of women and racialized minorities were considered to be ‘sporting space invaders’ when they excel in the sport that white men have historically dominated, such as tennis (Litchfield et al., 2018) (e.g., Serena Williams) and track and field (Brown, 2015) (e.g., Caster Semenya).

Only two quantitative articles were located and selected for this review in accordance with our criteria, which suggests that intersectionality theory is largely lacking in quantitative PA research. These two studies employed inter-categorical intersectionality and used a number of social categories. Methodological challenges in using intersectionality within the quantitative research framework have been well-noted in recent literature. Notably, Bowleg and Bauer (Bowleg & Bauer, 2016) argued that intersectionality is not developed to be operationalized, measured, or tested within the quantitative research framework. In fact, one of the major critiques of incorporating intersectionality in quantitative research is that quantitative analyses which are largely based on categorical thinking may not be adequate in operationalizing the multiple and fluid nature of individuals’ social categories and how inequalities are produced through relations of difference (Bowleg, 2008; Flintoff et al., 2008). This further explains the reason why our review included mostly qualitative evidence.

Quantifying intersectionality is a relatively new direction in quantitative research and only began picking up momentum in the early 2010s in social epidemiology (Galea & Link, 2013) and psychology (Syed, 2010). In our review, it was evident that intersectionality is an important theory to incorporate when examining inequalities in PA opportunities and participation. Actively claiming intersectionality theory, two quantitative articles found that individuals with minority social categories are disadvantaged in PA participation. In parallel with the suggestion of Bowleg and Bauer (2016), innovating how we measure, analyze, and interpret the potential impact of intersecting social categories using quantitative methodology is important because it will enable generating large-scale data, which could help to identify “at-risk (low/no PA)” (p. 376) groups and their determinants at the population level and, in turn, targeted strategies can be developed.

In PA scholarship, interactions between different demographic variables (most commonly the age gender interaction effect on PA) have been tested using different statistical techniques for decades (Lee et al., 2016; Sherar, Esliger, Baxter-Jones, & Tremblay, 2007). However, within conventional quantitative PA research, interactional analyses were used to identify ‘multiple, interactive risk factors’ at the individual level rather than to investigate systemic patterns of discrimination as the key cause of unequal opportunities for and participation in PA, grounded in intersectionality or on the basis of political act while seeking social justice at its core. It is also noted that theorising the relationship between different categories raises complex issues of theory, methodology, and politics (Flintoff et al., 2008). Because PA literature has been largely dominated by quantitative, biomedical, and bio-behavioral (and therefore self-defined as apolitical) research, researchers have largely eschewed operationalizing the impact of intersectional oppression due to a focus on individual differences as causes of inequality in PA. Notwithstanding methodological limitations, two original, peer-reviewed articles (Abichahine & Veenstra, 2017; Lee et al., 2020) included in this review provided preliminary support that quantitative intersectionality can advance our understanding of disparities in PA opportunities and participation.

This review is the first to provide the scope and gaps in PA research that claim to operationalize intersectionality and sheds light on advancing quantitative intersectionality. However, several limitations should be noted. Given that this review only included original articles published in peer-reviewed journals in English, the findings of this review may not encompass perspectives from non-peer-reviewed grey literature or articles in languages other than English. However, intersectionality was originated by Crenshaw, a Black feminist scholar based in the US; as such, the evidence thus far has been predominantly produced by English speaking scholars from Western countries where racial diversity is more visible than in many other countries due to high levels of settler migration and immigration. This review likely excluded quantitative evidence that have examined the interactive effect of more than two social categories on PA. This was a deliberate decision to only include quantitative investigations that were explicitly claimed operationalization of intersectionality theory. In this regard, future quantitative investigation is encouraged to conduct research on marginalized groups and power relations that operationalizes intersectionality theory in order to reduce interlocking social-structural inequalities in PA, and other domains (Bowleg & Bauer, 2016). Bowleg (2012) also suggested that future research that operationalizes intersectionality should clearly mention ‘intersectionality’ in titles, keywords, abstracts, or articles to innovate sampling, measurement and methodologies and advance the quantitative study of intersectionality. Overall, the present review's inclusion criteria can offer guidance for future intersectionality-based PA studies.

5. Conclusion

This scoping review identified the scope of and gaps in PA research claimed operationalization of intersectionality theory. PA, particularly sport, appears to be a unique context where complex processes of social and structural forces create a space that is unwelcoming of and even harmful for certain groups based on their membership in various social categories. Individuals are often segregated based on the sex/gender binary, intensifying stereotypical differences between binary categories, leading men and women to occupy separate spaces, and largely excluding individuals who do not identify within the gender binary (e.g., who are non-binary). In addition, middle-class, white heteronormative masculinity appears to dominate PA spaces, while ‘othering’ individuals who are racialized and non-heterosexual. Our review of 45 articles further reflects decades of struggle in creating inclusive PA environments. Additional research should aim to better elucidate power imbalances across different social categories, as these have been shown to lead to inequality in PA opportunities and participation. Intersectionality theory may serve as a useful framework in both qualitative and quantitative investigations to this end. Our review also suggested that advancement in quantitative intersectionality is critical in order to better understand disparities in PA opportunities and participation and produce knowledge to inform more inclusive PA promotion efforts.

Financial disclosure

This systematic scoping review was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Funding File # 430-2020-00097).

Ethical statement

This review article did not involve human subjects research. As such, this research did not require ethical approval from an Institutional Review Board.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Heejun Lim: Investigation, Data screening, extracting & synthesizing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Eun Jung: Investigation, Data screening & extracting, Writing – original draft. Kaila Jodoin: Investigation, Data screening & extracting. XiaoWei Du: Investigation, Data screening & extracting. Lee Airton: Evidence synthesis, Writing – review & editing. Eun-Young Lee: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Evidence synthesis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100808.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Abichahine H., Veenstra G. Inter-categorical intersectionality and leisure-based physical activity in Canada. Health Promotion International. 2017;32(4):691–701. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daw009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adjepong A. ‘We’re, like, a cute rugby team’: How whiteness and heterosexuality shape women's sense of belonging in rugby. International Review for the Sociology of Sport. 2017;52(2):209–222. [Google Scholar]

- Alley T.R., Hicks C.M. Peer attitudes towards adolescent participants in male- and female-oriented sports. Adolescence. 2005;40(158):274–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubert S., Barnes J.D., Abdeta C. Global matrix 3.0 physical activity report card grades for children and youth: Results and analysis from 49 countries. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2018;15(Suppl 2):S251–S273. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2018-0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak K.S., Krane V., Ross S.R., Mann M.E., Kaunert C.A. Visual negotiation: How female athletes present intersectional identities in photographic self-representations. Quest. 2018;70(4):471–491. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer G.R. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;110:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman A.E., Reis R.S., Sallis J.F. Correlates of physical activity: Why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet. 2012;380(9838):258–271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benn T., Dagkas S., Jawad H. Embodied faith: Islam, religious freedom and educational practices in physical education. Sport, Education and Society. 2011;16(1):17–34. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2011.531959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett A.T., Ge Y., Schinke R.J., McGannon K.R. Intersecting identities of elite female boxers: Stories of cultural difference and marginalization in sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2017;32:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borland J.F., Bruening J.E. Navigating barriers: A qualitative examination of the under-representation of black females as head coaches in collegiate basketball. Sport Management Review. 2010;13(4):407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2010.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. When Black + lesbian + woman ≠ Black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles. 2008;59:312–325. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267–1273. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L., Bauer G. Invited reflection: Quantifying intersectionality. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2016;40(3):337–341. doi: 10.1177/0361684316654282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L.E.C. Sporting space invaders: Elite bodies in track and field, a South African context. South African Rev Sociol. 2015;46(1):7–24. doi: 10.1080/21528586.2014.989666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Francique A.R. Fit and phat: Black college women and their relationship with physical activity, obesity and campus recreation facilities. Sport, Education and Society. 2011;16(5):553–570. [Google Scholar]

- Cheeks G., Carter-Francique A. HBCUS versus HWCUS: A critical examination of institutional distancing between collegiate athletic programs. Race, Gend Cl. 2015;22:1–12. http://search.proquest.com/openview/d018ba835364c7e03b8d5a2caff7ddf5/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=25305 [Google Scholar]

- Collins P.H. Toward a new vision: Race, class, and gender as categories of analysis and connection. Race, Sex Cl. 1993;1(1):25–45. doi: 10.4324/9780429500930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P.H. Some group matters: Intersectionality, situated standpoints, and black feminist thought. A Companion to African-American Philos. Published online. 2006:205–229. doi: 10.1002/9780470751640.ch12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P.H. Intersectionality's definitional dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology. 2015;41:1–20. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooky C., Wachs F.L., Messner M., Dworkin S.L. It ’s not about the game : Don Imus , race , class , gender. Sociology of Sport Journal. 2010;27(2):139–159. [Google Scholar]

- Cragg S., Costas-Bradstreet C., Arkell J., Lofstrom K. 2016. Policy and program considerations for increasing sport participation among members of under- represented groups in Canada: A literature review. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. Univ Chicago Leg Forum; 1989. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex : A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine , feminist theory and antiracist politics. Published online 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review. 1991;43(6):1241–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Dagkas S. Problematizing social justice in health pedagogy and youth sport: Intersectionality of race, ethnicity, and class. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport. 2016;87(3):221–229. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2016.1198672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagkas S., Hunter L. ‘Racialised’ pedagogic practices influencing young Muslims' physical culture. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy. 2015;20(5):547–558. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2015.1048210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson J. Racism against the abnormal? The twentieth century gay games, biopower and the emergence of homonational sport. Leisure Studies. 2014;33(4):357–378. doi: 10.1080/02614367.2012.723731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dlugonski D., Martin T.R., Mailey E.L., Pineda E. Motives and barriers for physical activity among low-income black single mothers. Sex Roles. 2017;77(5–6):379–392. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin S.L., Swarr A.L., Cooky C. Justice in sport : The treatment of South African track star Caster Semenya. Feminist Studies. 2017;39(1):40–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ekholm D., Dahlstedt M., Rönnbäck J. Problematizing the absent girl: Sport as a means of emancipation and social inclusion. Sport in Society. 2019;22(6):1043–1061. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2018.1505870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest N.M., Hyde J.S. Intersectionality in quantitative psychological research: II. Methods and techniques. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2016;40(3):319–336. doi: 10.1177/0361684316647953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flintoff A. Tales from the playing field: Black and minority ethnic students' experiences of physical education teacher education. Race, Ethnicity and Education. 2014;17(3):346–366. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2013.832922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flintoff A., Fitzgerald H., Scraton S. The challenges of intersectionality: Researching difference in physical education. International Studies in Sociology of Education. 2008;18(2):73–85. doi: 10.1080/09620210802351300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes K. Feminist organizing around gender discrimination lawsuits in higher education. Feminist Form. 2018;30(2):65–89. doi: 10.1353/ff.2018.0019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S., Link B.G. Six paths for the future of social epidemiology. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;178(6):843–849. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2020. Role of sport Canada.https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/services/role-sport-canada.html [Google Scholar]

- Herrick S.S.C., Duncan L.R. A qualitative exploration of LGBTQ+ and intersecting identities within physical activity contexts. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology. 2018;40(6):325–335. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2018-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinpoor A.R., Bergen N., Kunst A. Socioeconomic inequalities in risk factors for non communicable diseases in low-income and middle-income countries: Results from the world health survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):912. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardorff E von, Steink I. A companion to qualitative research. 2004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King S.J., McDonald M.G. (Post)identity and sporting cultures: An introduction and overview. Sociology of Sport Journal. 2007;24(1):1–19. doi: 10.1123/ssj.24.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen L.K., Fisher L.A., Moret L. The coach's journal: Experiences of black female assistant coaches in NCAA division I women's basketball. Qualitative Report. 2019;24(3):632–658. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. From forever foreiners to model minority: Asian American men in sports. Physical Culture and Sport. Studies and Research. 2016;72:23–32. doi: 10.1515/pcssr. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E.Y., An K., Jeon J.Y., Rodgers W.M., Harber V.J., Spence J.C. Biological maturation and physical activity in South Korean adolescent girls. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2016;48(12):2454–2461. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E.-Y., Khan A., Uddin R., Lim S., George L. J Adolesc Heal; 2020. Six-year trends and intersectional correlates of meeting 24-hour movement guidelines among 372,433 South Korea adolescents: Korea youth risk behaviour surveys 2013-2018. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litchfield C., Kavanagh E., Osborne J., Jones I. Social media and the politics of gender, race and identity: The case of Serena Williams. European Journal Sport Society. 2018;15(2):154–170. doi: 10.1080/16138171.2018.1452870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCall L. The complexity of intersectionality. Signs. 2005;30(3):1771–1800. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald M.G. Dialogues on whiteness, leisure and (anti)racism. Journal of Leisure Research. 2009;41(1):5–21. doi: 10.1080/00222216.2009.11950156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell J., Carter-Francique A. An intersectional analysis of the workplace experiences of African American female athletic directors. Sex Roles. 2017;77:393–408. doi: 10.1007/s11199-016-0730-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mena E., Bolte G. Intersectionality-based quantitative health research and sex/gender sensitivity: A scoping review. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2019;18(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-1098-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowatt R.A., French B.H., Malebranche D.A. Black/female/body hypervisibility and invisibility: A black feminist augmentation of feminist leisure research. Journal of Leisure Research. 2013;45(5):644–660. doi: 10.18666/jlr-2013-v45-i5-4367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis A., Fullagar S. Narrating the multiplicity of “derby grrrl”: Exploring intersectionality and the dynamics of affect in roller derby. Leisure Sciences. 2013;35(5):422–437. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2013.831286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M.D., Godfrey C.M., McInerney P., Soares C.B., Khalil H., Parker D. Joanne Briggs Inst; 2015. The joanna briggs institute reviewers' manual 2015: Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. Published online. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin-Wright A.J., Hylton K., Norman L. Critical race theory and black feminist insights into “race” and gender equality. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2020;43(7):1111–1129. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2019.1640374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ratna A. “Who wants to make aloo gobi when you can bend it like beckham?” British asian females and their racialised experiences of gender and identity in women's football. Soccer and Society. 2011;12(3):382–401. doi: 10.1080/14660970.2011.568105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ratna A. Intersectional plays of identity: The experiences of British asian female. Sociological Research Online. 2013;18(1):108–117. [Google Scholar]

- Ray R. An intersectional analysis to explaining a lack of physical activity among middle class Black women. Social Compass. 2014;8(6):780–791. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts N.S. Crossing the color line with a different perspective on whiteness and (anti)racism: A response to mary McDonald. Journal of Leisure Research. 2009;41(4):495–509. doi: 10.1080/00222216.2009.11950187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherar L.B., Esliger D.W., Baxter-Jones A.D.G., Tremblay M.S. Age and gender differences in youth physical activity: Does physical maturity matter? Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2007;39(5):830–835. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180335c3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stride A. Let us tell you! South Asian, Muslim girls tell tales about physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy. 2014;19(4):398–417. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2013.780589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stride A. Centralising space: The physical education and physical activity experiences of South Asian, Muslim girls. Sport, Education and Society. 2016;21(5):677–697. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2014.938622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M. Disciplinarity and methodology in intersectionality theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65(1):61–62. doi: 10.1037/a0017495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tredway K. Serena Williams and (the perception of) violence: Intersectionality, the performance of blackness, and women's professional tennis. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2019:1–18. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2019.1648846. 0(0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walseth K. Muslim girls' experiences in physical education in Norway: What role does religiosity play? Sport, Education and Society. 2015;20(3):304–322. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2013.769946. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton D.E.R., Bredin S.S.D. Health benefits of physical activity: A systematic review of current systematic reviews. Current Opinion in Cardiology. 2017;32(5):541–556. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch N.M., Siegele J., Smith Z.T., Hardin R. Making herstory: Cherokee women's stickball. Ann Leis Res. 2019:1–21. doi: 10.1080/11745398.2019.1652104. 0(0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White M.D., Marsh E.E. Content analysis: A flexible methodology. Library Trends. 2006;55(1):22–45. doi: 10.1353/lib.2006.0053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- With-Nielsen N., Pfister G. Gender constructions and negotiations in physical education: Case studies. Sport, Education and Society. 2011;16(5):645–664. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2011.601145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Withycombe J.L. Intersecting selves: African American female athletes' experiences of sport. Sociology of Sport Journal. 2011;28(4):478–493. doi: 10.1123/ssj.28.4.478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.