Abstract

Baclofen is an effective therapeutic for the treatment of spasticity related to multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injuries, and other spinal cord pathologies. It has been increasingly used off-label for the management of several disorders, including musculoskeletal pain, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and alcohol use disorder. Baclofen therapy is associated with potential complications, including life-threatening toxicity and withdrawal syndrome. These disorders require prompt recognition and a high index of suspicion. While these complications can develop following administration of either oral or intrathecal baclofen, the risk is greater with the intrathecal route. The management of baclofen toxicity is largely supportive while baclofen withdrawal syndrome is most effectively treated with re-initiation or supplementation of baclofen dosing. Administration of other pharmacologic adjuncts may be required to effectively treat associated withdrawal symptoms. This narrative review provides an overview of the historical and emerging uses of baclofen, offers practical dosing recommendations for both oral and intrathecal routes of administration, and reviews the diagnosis and management of both baclofen toxicity and withdrawal.

Keywords: Baclofen, spasticity, toxicity, withdrawal

Introduction

Baclofen was originally developed as an antiepileptic in 1962 by Swiss chemist Heinrich Keberle. 1 Although it failed to effectively treat epilepsy, baclofen was found to reduce spasticity in selected patients. 1 It was introduced in 1971 and ultimately approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1977 for the treatment of spasticity related to multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injuries, and other spinal cord pathologies. 2 Providers must be aware of the potential pitfalls associated with baclofen therapy. Both toxicity and withdrawal represent medical emergencies that carry a risk of death. 3 The purposes of this narrative review are to provide an overview of the common uses of baclofen in the clinical setting, assist providers with oral and intrathecal dosing regimens, and review the diagnosis and management of baclofen toxicity and withdrawal. Relevant English language references on baclofen administration, pharmacology, and adverse effects were reviewed. Included references consist of randomized controlled trials, non-randomized trials, expert opinions, commentaries, structured and unstructured reviews, case reports, and package inserts. References in languages other than English and unpublished reports were not included. Literature search was performed using PubMed.

Mechanism of action

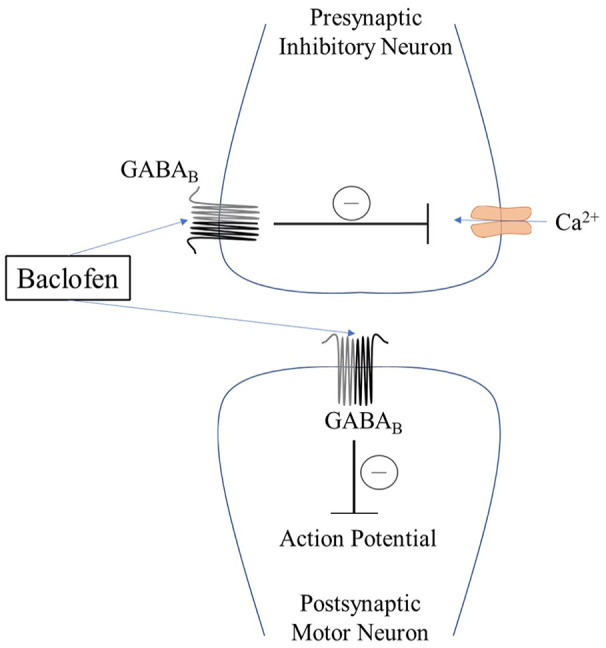

Baclofen is an agonist for gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)B receptors on pre- and postsynaptic neurons in the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system. 4 Its action results in inhibition of the transmission of both mono- and polysynaptic reflexes at the spinal cord, relaxing spasticity. 5 Agonism of GABAB receptors found on type Ia presynaptic neurons arising from extrafusal muscle spindles causes an influx of potassium (K+) leading to hyperpolarization of the neuronal membrane, as well as decreased calcium (Ca2+) influx at presynaptic nerve terminals.4,5 The net result is a decrease in the rate of action potential threshold being reached by presynaptic type Ia neurons and decreased amplitude of excitatory postsynaptic potentials arising from gamma motor neurons that innervate the muscle spindles. This mechanism accounts for baclofen’s therapeutic effect of decreasing spasticity (Figure 1). However, GABAB receptors are also found on other neurons throughout the body, including in the CNS and sympathetic nervous system, which can account for the side effects of drowsiness and dizziness. Baclofen is the only FDA-approved GABAB agonist. 6

Figure 1.

A simple model of baclofen’s presynaptic and postsynaptic activity mediated through the GABAB receptor. The net result is a reduction in the postsynaptic motor neuron action potential, decreasing spasticity.

GABA: gamma-aminobutyric acid; Ca2+: calcium.

Baclofen indications

Spasticity

Baclofen is an effective treatment for spasticity of cerebral or spinal origin.7,8 It is FDA-approved for the treatment of spasticity through several routes of administration. Oral indications include management of reversible spasticity associated with spinal cord injury and multiple sclerosis. Oral baclofen is the most commonly used antispasmodic. 9 Intrathecal indications include the management of severe spasticity associated with spinal cord injury and multiple sclerosis. In patients greater than 4 years of age, baclofen can be used for cerebral causes of spasticity, such as cerebral palsy and traumatic brain injury. 2 Compared with oral administration, intrathecal baclofen (ITB) can more effectively treat spasticity directly at the level of the spinal cord with less associated systemic side effects. 10 In a cross-sectional matched cohort survey study comparing the two routes of administration, patients who received ITB experienced significantly fewer and less severe spasms compared with those who received oral baclofen. 11 In this study, there were no significant differences between the two groups in regards to pain, sleep, fatigue, or quality of life.

Off-label uses

Alcohol use disorder

Recently, baclofen has been administered as an off-label treatment for alcohol use disorder (AUD). 12 Alcohol intake and reinforcement is mediated by mesolimbic dopamine neurons. There is a high concentration of GABAB receptors in this area of the brain, and it is believed that activation of these receptors inhibits the surrounding dopaminergic pathways, leading to a decrease in dopamine release in response to alcohol consumption with a corresponding reduction in craving. 13 Despite this physiologic basis, there is no consistent evidence for the use of baclofen as an effective treatment for AUD. 12

In 2007, Addolorato et al. 14 conducted a double-blind randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of oral baclofen on maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis. In this trial, 74% of the patients who received baclofen achieved and maintained abstinence compared with 29% of the placebo group (odds ratio = 6.3 [95% CI 2.4–16.1]; p = 0.0001). Baclofen doses reached a maximum of 30 mg/day, and no hepatic side effects were noted. In 2015, Müller et al. 15 performed a randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of individually titrated high-dose baclofen for the treatment of alcohol dependence. In this trial, individually titrated high-dose baclofen (30–270 mg/day) was well tolerated and effective in supporting alcohol-dependent patients in maintaining alcohol abstinence. In 2017, Reynaud et al. 16 conducted a randomized controlled trial (ALPADIR study) comparing the efficacy and safety of baclofen at a target dose of 180 mg/day with placebo to evaluate the maintenance of abstinence and reduction in alcohol consumption in 320 adult alcohol-dependent patients. The results of this study did not demonstrate a statistically significant superiority of baclofen in the maintenance of abstinence or reduction in alcohol consumption in alcohol-dependent patients. Similarly, other randomized controlled trials have failed to demonstrate baclofen’s efficacy in the setting of AUD.17–19

Minozzi et al. 20 performed a Cochrane review of 12 randomized controlled trials to assess the efficacy and safety of baclofen for the treatment of AUD. The authors did not find any difference between baclofen and placebo and concluded that the evidence regarding the use of baclofen as a first-line treatment for AUD is uncertain. Conversely, a meta-analysis by Pierce et al. 21 evaluated 13 randomized controlled trials and concluded that baclofen seems to be effective in the treatment of alcohol dependence, especially among heavy drinkers.

A cohort study from the French Health Insurance claims database compared outcomes of adult patients being treated for AUD with oral baclofen and three other approved drugs. 22 The results indicated that baclofen exposure was associated with a significant dose-dependent increase in the risk of hospitalization and mortality versus the other approved AUD drugs. Furthermore, there has been expert opinion highlighting a negative benefit:harm ratio for the use of baclofen for this indication. 23 Despite this, in 2018, the French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety (ANSM) formally approved using baclofen to treat alcohol dependence, after temporarily approving it for this indication in 2014. France became the first country to support this off-label use of baclofen; the US FDA has not made similar formal statements.24,25 Shortly after the ANSM approval for the use of baclofen in alcohol-dependent patients, the Cagliari Expert Consensus Group published a statement supporting the off-label use of baclofen as a first-line pharmacologic treatment in patients with a contraindication to approved medications and as a second-line pharmacologic treatment in patients who have not responded to approved pharmacologic treatments for AUD. 26

In 2020, Rigal et al. 27 published a randomized controlled trial (Bacloville’s study) comparing baclofen titrated up to 300 mg/day versus placebo in adult outpatients with high-risk alcohol consumption. In this study, authors reported that baclofen was more effective than placebo in reducing alcohol consumption to low-risk levels. Serious adverse events, including death, were more frequent with baclofen administration. Notably, there have been concerns related to the data transparency, delay in study publication, primary outcome measure, and modifications to the study protocol.28,29 Overall, additional high-quality studies are needed to further evaluate the role of baclofen in the treatment of AUD.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

One of the most widely postulated mechanisms for the development of reflux symptoms is excess transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation (TLESR) episodes. 30 These episodes are physiologic processes that allow for venting of gastric gas and act as protection against the accumulation of excess gas in the stomach. 30 TLESRs are vasovagally induced reflexes that are triggered by gastric distention and work via several neurotransmitters and receptors, including the GABAB receptor. 31 Through its GABAB receptor activity, baclofen inhibits TLESRs, and has been shown to significantly inhibit gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) episodes in both healthy volunteers and in patients with reflux disease.32–34

Other off-label uses

There are case reports or small studies describing the off-label use of baclofen for the treatment of several clinical entities, including muscle spasm/musculoskeletal pain, 2 persistent/chronic hiccups,35–37 autism spectrum disorders, 38 chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 39 narcolepsy, 40 persistent speech stuttering, 41 post-hemorrhoidectomy pain, 42 trigeminal neuralgia, 43 and low back pain. 44

Oral baclofen

Oral baclofen pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

The oral form of baclofen is well absorbed and has a bioavailability of approximately 75%–80% systemically.45,46 It undergoes approximately 15% hepatic metabolism and is primarily excreted in the urine with 65%–80% of the drug excreted in its unchanged form.47,48 Baclofen’s water solubility does not allow it to readily cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) when administered orally. 48 Accordingly, oral baclofen may require higher doses to achieve a therapeutic effect and have an increased potential for unwanted side effects, such as somnolence and sedation. Table 1 summarizes the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of baclofen administration.2,48–51

Table 1.

Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of baclofen.

| Route of administration | Onset of action | Peak effect | Half-life |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Rapid | 45 min–2.5 h | 2–6 h* |

| Intrathecal, bolus | 30 min–1 h | 4 h | 1–5 h** |

| Intrathecal, continuous infusion | 6–8 h after infusion initiation | 24–48 h after infusion initiation | 5 h** |

Plasma; **cerebrospinal fluid.

Oral baclofen dosing for spasticity

Oral baclofen dosing for spasticity starts at an initial dose of 5 mg, administered one to three times daily. 2 The goal of symptomatic relief of spasticity is reached with incremental increases of 5 mg every 3 days, with a maximum dose of 80 mg/day. 2

Oral baclofen dosing for AUD

There is no consensus on the appropriate dose of oral baclofen for the off-label treatment of AUD, and several dosing regimens are in use. Overall, the daily baclofen dose should be based on safety, tolerability, and individual patient response. 26 There is substantial variation in the daily dose of baclofen required to achieve abstinence, reduction in alcohol consumption, or a decrease in alcohol craving.12,26 The Cagliari Expert Consensus Group recommends an oral baclofen dosing regimen that begins with an initial dose of 5 mg, administered three times a day, and titrating up to 5–10 mg/day every 3 days. 26 No recommended maximum dose is provided in the Cagliari Statement nor in a follow-up clinical practice review authored by the same group of experts.12,26 When the ANSM approved the use of oral baclofen to treat AUD, a maximum dose of 80 mg/day was authorized. 25

Oral baclofen dosing for other off-label uses

For persistent or chronic hiccups, oral baclofen dosing starts with an initial dose of 5–10 mg, administered three times a day and titrating up to a maximum dose of 45 mg/day. 37 For muscle spasms or musculoskeletal pain, oral baclofen dosing starts with an initial dose of 5–10 mg, administered —one to three times a day as needed. 2

Oral baclofen dosing in renal impairment

Manufacturers do not provide specific dosing adjustment recommendations in patients with renal impairment. Given that approximately 80% of baclofen is cleared via glomerular filtration, it is prudent to exercise caution with dosing regimens in this setting. 52 There have been several published case reports describing baclofen overdose in the context of renal dysfunction.53–55 The authors of a multicenter study of baclofen pharmacokinetics recommend a dose adjustment based on estimated creatinine clearance (CrCl) thresholds. 56 Their specific recommendations include: CrCl > 80 mL/min: maintain standard dose of 5 mg every 8 h; CrCl 50–80 mL/min: reduce dose to 5 mg every 12 h; CrCl 30–50 mL/min: reduce dose to 2.5 mg every 8 h; and CrCl < 30 mL/min: reduce dose to 2.5 mg every 12 h. Although baclofen is dialyzable in cases of toxicity, it should be avoided in patients with end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis.52,57

Oral baclofen dosing in hepatic impairment

There are no formal recommendations for dosing adjustments in patients with hepatic impairment. As baclofen undergoes only limited hepatic metabolism, it may be a safe treatment option in patients with liver disease. 12 While Macaigne et al. 58 described a case of probable baclofen-induced acute hepatitis in an alcohol-dependent patient, the data from large clinical trials suggest that baclofen is generally safe in patients with advanced liver disease.14,59,60

Intrathecal baclofen

ITB pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

ITB has a different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile compared with oral baclofen administration (Table 1). Baclofen directly administered into the intrathecal space allows for therapeutic cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations to be achieved with plasma concentrations 100 times less than that associated with oral administration. 49 Plasma concentrations of baclofen during intrathecal administration are typically 0–5 ng/mL. 49

ITB dosing for spasticity

ITB dosing for spasticity begins with a screening test to assess for a positive response, characterized by a reduction in tone, a reduction in spasms, or improved functional capacity. 61 A screening test commonly starts with an ITB bolus dose of 50 µg followed by observation for 8 h. 61 If no response is identified, a subsequent ITB bolus dose of 75 µg is administered at least 24 h after the initial 50 µg bolus. 61 The patient is again monitored for a positive response for 8 h. If this dose is not adequate to provide a positive response, then after 24 h, a final screening bolus can be administered with a maximum ITB dose of 100 µg.49,61

Maintenance ITB infusion dosing is dictated by the response to the initial screening dose. If a positive response has been achieved with reduction of spasticity that lasts > 4 h, but < 8 h, the maintenance dose will be double that of the screening dose with the infusion over 24 h. 61 For example, if a reduction in spasticity is achieved for 5 h after an ITB 50 µg screening bolus, then the infusion dose would be ITB 100 µg delivered over a 24-h period. If the screening dose provided a positive response for > 8 h or caused a negative reaction (e.g. change in mental status, loss of function, change in vital signs), then the maintenance infusion dose will not change from the screening dose. 61 For example, if a reduction in spasticity is achieved for a 10-h time period after an ITB 50 µg screening bolus, then the infusion dose will be ITB 50 µg to be delivered over a 24 hour period. It is recommended to allow ITB to establish a steady state for a minimum of 24 h before titrating up from the initial infusion dose. 61 Furthermore, it is recommended to increase the infusion dose up to 10%–30% per day for spinal cord-associated spasticity and 5%–15% per day for spasticity from cerebral origin.49,61

Baclofen toxicity

While the expansion of baclofen’s use beyond the treatment of spasticity has been associated with an increased number of overdose and toxicity events, the most serious adverse outcomes have been associated with ITB administration.3,62–72 It is important for providers to maintain a high diagnostic index of suspicion as the nature and severity of symptoms varies widely. Patient history, vital sign abnormalities, and physical examination findings are all important in establishing the diagnosis. Baclofen toxicity should be considered in the setting of hypotonia and flaccid paralysis, while spasticity and hyperreflexia are more commonly encountered with baclofen withdrawal. 68 Baclofen toxicity can be life-threatening with hemodynamic instability, cardiac arrhythmias, and respiratory failure often requiring admission to the intensive care unit (ICU). Signs and symptoms of baclofen toxicity are shown in Table 2.62–85

Table 2.

Clinical signs and symptoms of baclofen toxicity and withdrawal.

| System | Baclofen toxicity | Baclofen withdrawal |

|---|---|---|

| General | Hypothermia, death | Pruritus, hyperthermia, multisystem organ failure, death |

| Psychiatric | Hallucinations, agitation, mania, catatonia | Hallucinations, anxiety, paranoia, delusions |

| Neurological | Hyporeflexia, tremor, confusion, impaired memory, lethargy, somnolence, seizures, encephalopathy, coma | Hyperreflexia, tremor, paresthesias, headache, altered mental status, delirium, seizures |

| Cardiovascular | Conduction abnormalities, prolonged QTc interval, autonomic dysfunction: bradycardia, tachycardia, hypotension, hypertension | Acute reversible cardiomyopathy, cardiac arrest, autonomic dysfunction: bradycardia, tachycardia, hypotension, hypertension |

| Respiratory | Respiratory failure | Respiratory failure |

| Gastrointestinal | Nausea, vomiting | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea |

| Musculoskeletal | Hypotonia | Hypertonia, rhabdomyolysis |

Baclofen toxicity signs and symptoms

In the setting of excess GABAB activity, mild baclofen toxicity typically presents with nonspecific signs of CNS depression, including lethargy, confusion, and somnolence.65,86 Although the mechanism is poorly understood, more significant baclofen toxicity can present with generalized tonic–clonic or myoclonic seizures despite its inhibitory CNS actions. 65 Seizures may result from activity on both the GABAergic and glutamatergic systems.73,83 In addition, the excess of GABAB activity may induce neural excitation via hyperpolarization of the presynaptic and postsynaptic inhibitory interneurons, effectively lowering the seizure threshold.63,83 Neurologically, baclofen toxicity can also present with metabolic encephalopathy, nonconvulsive status epilepticus, and coma. 65 Complete loss of brainstem reflexes has been reported in several cases of baclofen overdose.67,70 Electroencephalogram (EEG) can assist with the diagnosis of baclofen toxicity. 64 EEG findings in patients with baclofen toxicity have been notable for nonconvulsive status epilepticus, moderate-to-severe generalized slowing, triphasic waves, and burst suppression.63,71,87

Variation in baclofen toxicity presentation

There have been several cases of baclofen overdose described in the literature with notable variation in dosing thresholds and clinical presentations.62–72 There is a not a well-defined threshold dose above which toxicity reliably occurs. Toxicity-induced acute encephalopathy with abnormal EEG findings has been reported in patients on modest stable regimens of oral baclofen (30–140 mg/day). 71 In a published case series of 23 presentations of baclofen overdose, Leung et al. 65 found a higher ICU admission rate, rate of mechanical ventilation, and prolonged hospital length of stay in patients taking more than 200 mg/day of oral baclofen compared with those who received less than 200 mg/day. In this same series, coma, delirium, and clinical seizures only occurred with oral baclofen regimens over 200 mg/day. While this may provide some rough dosing guidance, the patients’ weights were not described in this series. Hypotension, hypotonia, bradycardia, and respiratory depression are expected signs of baclofen toxicity, although the clinical presentation can vary dramatically. 65 Parker-Pitts et al. 68 described a case of baclofen toxicity that mimicked the signs and symptoms of baclofen withdrawal in a patient with a functioning intrathecal pump. The patient described in their case paradoxically presented with dyspnea, hypertension, and tachycardia. In the case series presented by Leung et al., 65 hypertension was considerably more common with high-dose (> 200 mg) versus low-dose (< 200 mg) baclofen toxicity. In this same series, tachycardia was also more common than bradycardia in the high-dose toxicity group.

Baclofen toxicity laboratory analysis

Plasma baclofen levels can be directly measured, although this is not commonly included on initial toxicology analyses.3,88 The normal therapeutic blood plasma concentration with oral baclofen administration is 0.08–0.4 mg/L, while the toxic concentration is 1.1–3.5 mg/L. 89 The reported comatose-fatal concentration is 6.0–9.6 mg/L. 89 Despite these reference ranges, clinical improvement does not always directly correlate with a reduction in plasma baclofen concentration.3,87 Furthermore, plasma concentrations are not reliable in the setting of ITB administration due to low penetration of the BBB. 49

Baclofen toxicity treatment

There is no specific treatment for baclofen toxicity. Effective management requires the prompt cessation of baclofen administration and supportive measures to ensure adequate circulatory and respiratory function until the toxic effects of the drug subside. 85 Administration of intravenous fluids and/or vasopressors is recommended for the treatment of hypotension. Endotracheal intubation and initiation of mechanical ventilation may be necessary for severe respiratory or CNS depression. 85 Benzodiazepines are considered the first-line treatment for seizures associated with baclofen toxicity. 3 However, in addition to its proconvulsant effects, baclofen has also been reported to cause a toxic metabolic encephalopathy. 71 Encephalopathic patients may be markedly sensitive to the CNS and respiratory depressive effects of benzodiazepines, so careful monitoring is encouraged. 71 Gastric lavage and activated charcoal have been recommended for children with baclofen overdose, but their effectiveness in the adult population is less clear.65,90 The elimination of baclofen is highly dependent on intact renal function. Hemodialysis may be necessary to reduce plasma drug levels, especially in patients with renal insufficiency.57,87

Baclofen withdrawal

Baclofen withdrawal syndrome represents the most concerning complication of baclofen therapy. Given its potential for rapid progression and high rates of morbidity and mortality, prompt recognition and effective treatment are essential. Baclofen withdrawal can occur in patients taking both oral baclofen and ITB.74–76,78–80,82,84,91,92 Patients typically experience withdrawal symptoms within hours to days following drug interruption, often close to their scheduled prescription refill dates or because of malfunctions in their ITB delivery systems.81,85 A high index of suspicion is required to diagnose baclofen withdrawal given the nonspecific nature of presentation and degree of symptom overlap with other clinical entities.93,94 Baclofen withdrawal is largely a clinical diagnosis, and there is no best diagnostic test (Table 2). Performing a thorough history and physical is critical. In general, withdrawal from oral baclofen is most often associated with the development of mild symptoms, while withdrawal from ITB is more likely to present with severe, life-threatening withdrawal syndrome.

Oral baclofen withdrawal

Withdrawal symptoms can be seen in patients taking oral baclofen following abrupt discontinuation or dosing reductions.76,91 These symptoms can include altered mental status, worsening of spasticity, fever, nausea, weakness, and autonomic instability.76,91 If left untreated, initial mild symptoms can progress to severe. One case report describes a patient who developed acute hypoxic respiratory failure requiring ICU admission and noninvasive ventilatory support following withdrawal from 60 mg/day of oral baclofen. 91 Although this patient’s condition rapidly improved after restarting oral baclofen, there is a paucity of evidence suggesting that drug levels in the CSF reach therapeutic levels following acute resumption of oral baclofen. Overall, doses must be carefully titrated to achieve relief of withdrawal symptoms because there is no direct conversion from intrathecal to oral baclofen dosing. 81 Future studies measuring CSF baclofen levels following initiation of oral regimens may prove useful in formulating conversion guidelines.

Oral baclofen withdrawal in maternal–fetal medicine

There are several case reports describing baclofen withdrawal in newborn infants secondary to intrauterine exposure.77,95–98 The mother was taking oral baclofen in all reported cases. Maternal ITB therapy has not been associated with neonatal withdrawal symptoms, likely because the daily doses are 20–100 times lower than oral baclofen doses. 97 Baclofen concentration in breast milk has been shown to correlate with maternal serum baclofen concentration. 96 However, there are no case reports of infants showing signs of withdrawal after weaning from breast milk. Presumably, this is due to the gradual transition from breast milk to solid foods that is typically done over the course of several months. Overall, baclofen is categorized as pregnancy category C by the FDA. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies evaluating its use in pregnant patients, and baclofen should only be used during pregnancy if the potential benefit justifies the potential fetal risk. 47

ITB withdrawal

Severe, life-threatening withdrawal symptoms are most commonly seen upon sudden cessation of ITB therapy from human error, ITB pump malfunction, migration of the intrathecal catheter, or after removal of the pump due to infection.92,99 Patients usually present with signs of excessive neurologic, autonomic, and psychiatric excitation due to abrupt cessation of baclofen’s inhibitory CNS effects.79,81 Early presenting symptoms include return of baseline spasticity, fever, pruritus, or paresthesias. Ongoing withdrawal may lead to hallucinations, delirium, seizures, and muscle rigidity. 85 If left untreated, withdrawal from ITB can progress to rhabdomyolysis, profound autonomic instability, multisystem organ failure, cardiac arrest, and death within 1–3 days.74,75,78,82,84 Severe baclofen withdrawal syndrome can mimic sepsis, malignant hyperthermia, autonomic dysreflexia, serotonin syndrome, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, or other hypermetabolic states with widespread rhabdomyolysis. 49 Furthermore, recognition of baclofen withdrawal can be especially difficult if patients are taking serotonergic and/or dopaminergic medications, have confounding medical or psychiatric comorbidities, or suffer from substance use disorders.

ITB withdrawal laboratory and imaging analysis

Laboratory and imaging studies can provide supporting evidence. For example, elevations in serum creatinine kinase, potassium, and creatinine levels can alert clinicians to the development of rhabdomyolysis that can occur with baclofen withdrawal syndrome. Several of the most common complications, including catheter kinking, migration, and discontinuity can be visualized by plain film radiography, although there is a lack of evidence directly evaluating the efficacy of plain films alone to reliably identify pump- and catheter-related complications.

Given the low risk and wide availability, plain radiography is usually the initial approach to imaging evaluation of suspected ITB pump–catheter system dysfunction. 100 In order to image the entire ITB system, a standard abdominal radiograph, an anteroposterior (AP) thoracic spine radiograph, and AP/lateral lumbar spine radiographs should be obtained. 75 Information about intrinsic pump function can also be obtained if radiographs are performed both before and after a programmed rotor rotation. It is important to note that these studies cannot evaluate catheter patency, occlusion, or leaks that are not associated with catheter discontinuities. 100 Injection of contrast material in the ITB system under fluoroscopy can identify several catheter-related complications, including perforations and leaks in the pump and/or catheter tubing. The use of computerized tomography imaging during and after contrast administration may provide better visualization. 100 If any radiographic study is performed with contrast, it is critical to aspirate 2–3 mL of fluid from the accessory port prior to injection of contrast, in order to prevent inadvertent baclofen overdose. 101 While the use of magnetic resonance imaging is not contraindicated in patients with ITB pumps, the pump manufacturer should be consulted prior to the study. Exposure to an external magnetic field may cause the rotor to stall, although it should restart without intervention after the device is removed from the magnetic field.100,102 Overall, surgical interrogation and exploration of the pump system may be necessary if imaging studies are nondiagnostic. 81 In terms of assessing ITB pump function, modern devices have alarms which signify low battery, low drug volume, or malfunction of the device. Older pump systems may not have these alarms and therefore have much higher rates of failure. Long-term follow-up studies performed in the 1990s have yielded a 37%–55% rate of pump and/or catheter malfunction in these devices. 101

Treatment of baclofen withdrawal

General treatment principles of baclofen withdrawal include frequent vital sign monitoring, avoidance of dehydration, support of cardiopulmonary function, management of associated symptoms such as seizures and delirium, and most importantly, re-initiation or supplementation of baclofen dosing.74,85,103 Hydration with intravenous fluids is important to prevent and treat the effects of rhabdomyolysis. 104 Given the potential for rapid decompensation, it is recommended that patients being managed for baclofen withdrawal be admitted to an ICU for close monitoring of their hemodynamics and respiratory status. In severe cases, respiratory support in the form of noninvasive or invasive ventilation modalities may be necessary. Significant morbidity and mortality can develop if appropriate resumption of baclofen is delayed or nonexistent. 75 Other pharmacologic agents have been used as treatment adjuncts and will be discussed in the sections below.

Baclofen

Definitive treatment of baclofen withdrawal syndrome involves urgent restoration of drug delivery, preferably via the same route and dosage as before the interruption. 105 Restoring ITB delivery may be delayed as this often involves coordinating a surgical team to evaluate an indwelling pump in the operating room setting. In 2016, a panel of 21 multidisciplinary physicians actively managing > 3200 ITB patients released best practice guidelines for troubleshooting ITB therapy. 105 The experts agreed that the first-line treatment for acute baclofen withdrawal is prompt restoration of baclofen therapy via intrathecal bolus or alternatively, temporary intrathecal catheter placement with a continuous infusion until definitive replacement in the operating room can be performed. A single intrathecal dose can help alleviate withdrawal symptoms for as long as 6–8 h.92,104 Hwang et al. 106 described a technique for continuing ITB when urgent pump removal is needed because of infection. In their case series, the authors removed the infected pumps, cleaned them with betadine, and then reconnected them to new or existing externalized lumbar drains. There were no reported withdrawal symptoms associated with this technique. While it appears to be safe, this treatment strategy requires further investigation. If the healthcare system lacks the equipment or qualified personnel to administer ITB, then it is acceptable to administer baclofen via the oral route. 105 However, the pharmacological limitations of the oral formulation such as its short half-life, poor BBB penetration, and supraspinal CNS activity causing sedation, dizziness, confusion, and somnolence render it an imperfect solitary substitution for ITB. 94 Orally administered baclofen may be poorly absorbed in critically ill patients, and as discussed above, there is no reliable oral to intrathecal conversion dose. Furthermore, since many patients who receive ITB have already failed high-dose oral baclofen therapy, oral administration may not be adequate to prevent withdrawal. 46 As a result, supplementation with other pharmacologic agents, such as benzodiazepines, cyproheptadine, propofol, dantrolene, and/or dexmedetomidine may be required to effectively treat associated withdrawal symptoms. A review of these medications is provided in Table 3.75,82,94,104,105,107–132

Table 3.

Pharmacologic adjuncts for the treatment of baclofen withdrawal syndrome.

| Medication | Mechanism of action | Onset time | Suggested dose | Half-life | Safety or monitoring concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diazepam | GABAA receptor agonist | IV: 0.5–3 min PO: 15–60 min |

IV: 2–10 mg q6h PO: 5–15 mg q6h |

IV: 20–50 h PO: 30–48 h |

CNS depression, hypotension, respiratory depression, FDA pregnancy category D, IV solution contains propylene glycol: caution in renal impairment |

| Lorazepam | GABAA receptor agonist | IV: 1–3 min PO: 20–30 min |

IV: 0.5–2 mg q6h PO: 0.5–2 mg q6h |

IV: 11–22 h PO: 14 h |

CNS depression, hypotension, respiratory depression, FDA pregnancy category D, IV solution contains propylene glycol: caution in renal impairment |

| Midazolam | GABAA receptor agonist | IV: 0.5–1 min | IV: 1–4 mg q6h | IV: 1.5–3 h | CNS depression, hypotension, respiratory depression, FDA pregnancy category D |

| Cyproheptadine | Histamine and serotonin antagonist | PO: 15–60 min | PO: 4–8 mg q6h, should not exceed 0.5 mg/kg/day | PO: 1–4 h | The anticholinergic effects of cyproheptadine can be additive with other anticholinergics. Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOI therapy and in debilitated, elderly patients |

| Propofol | GABAA receptor agonist | IV: 0.5–1 min | IV: 20–200 µg/kg/min | Context-sensitive half-time. Bolus or short infusion duration: 40 min. In prolonged infusions, half-life can be up to 1–3 days |

CNS depression, hypotension, respiratory depression. Risk of propofol infusion syndrome |

| Dantrolene | Ryanodine receptor antagonist | PO: variable IV: 1 min |

PO: 25 mg daily with titration up to 25 mg q8h over

1 week IV: divided doses up to a maximum cumulative dose of 10 mg/kg |

PO: 6–9 h IV: 4–8 h |

CNS depression, respiratory depression, hepatotoxicity, muscle weakness, FDA pregnancy category C |

| Dexmedetomidine | Alpha-2 receptor agonist | IV: 3–5 min | IV: 0.2–1.5 µg/kg/h | IV: 2–3 h | Hypotension, bradycardia, FDA pregnancy category C |

GABA: gamma-aminobutyric acid; IV: intravenous; PO: by mouth; q6h: every 6 h; q8h: every 8 h; CNS: central nervous system; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; MAOI: monoamine oxidase inhibitor.

Benzodiazepines and cyproheptadine

While there are no published studies evaluating the comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic agents for baclofen withdrawal, best practice guidelines recommend benzodiazepines and cyproheptadine as first-line adjuncts to ITB for the management of ITB withdrawal. 105 Both benzodiazepines and cyproheptadine target key receptors that are altered by chronic baclofen use. GABAB receptors are downregulated in response to the repeated and prolonged presence of baclofen-induced GABA agonism. 122 When baclofen is abruptly withdrawn, the result is hyperactivity of afferent nerve impulses, precipitating the characteristic withdrawal symptoms of seizures, muscle spasticity, and agitation. 75 Benzodiazepines target pre-sympathetic GABAA receptors, which act to circumvent the chronic baclofen-induced down regulation of GABAB receptors and lessen the severity of withdrawal symptoms. 94 Common benzodiazepines used as adjuncts in baclofen withdrawal include diazepam, lorazepam, and midazolam, with the former being the most commonly used. While there is no standard for initial dosing of these medications, they are typically titrated until muscle relaxation, normothermia, normotension, and resolution of seizures occur. 94

Cyproheptadine is a potent first-generation histamine and serotonin antagonist that has been used as an adjunct in the management of baclofen withdrawal syndrome.94,125 It is thought that chronic GABAB receptor activation inhibits the release of serotonin at the level of the brainstem. When this inhibition is abruptly removed (i.e. during baclofen withdrawal), there may be a state of excess serotonin activity in the brain. 108 When used in conjunction with baclofen and diazepam, cyproheptadine is associated with improvement in the management of acute ITB withdrawal symptoms. 125

Propofol

Propofol is a potent GABAA receptor agonist that is commonly used for the induction of general anesthesia. 131 It enhances GABA-mediated synaptic inhibition and may help to prevent the progression of acute baclofen withdrawal symptoms. Continuous infusions of propofol have been used successfully in cases of acute hyperspasticity associated with baclofen withdrawal. 107 Propofol is a global CNS depressant and has a rapid onset of action. It also produces dose-dependent hypotension and respiratory depression. 124 Because of these characteristics, propofol should only be administered in a closely monitored setting with personnel skilled at airway management readily available.

Dantrolene

Dantrolene is a muscle relaxant that is FDA-approved for the treatment of malignant hyperthermia and several muscle spasticity disorders. 128 It causes dissociation of excitation–contraction coupling by inhibiting the ryanodine receptor, which is responsible for releasing calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and inducing skeletal muscle contraction. 112 Dantrolene can be used as an adjunct in severe baclofen withdrawal to counteract the associated hypertonicity and hypermetabolic state. 132 It has been used successfully in a case of severe hyperthermia and spasticity that was unresponsive to high-dose oral baclofen administration. 121

Dexmedetomidine

Dexmedetomidine is a potent and highly selective alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist that possesses sedative and analgesic effects. 120 While it is FDA-approved for the maintenance of sedation in intubated patients in the ICU and peri-procedural sedation in non-intubated patients, it has been used off-label for the treatment and prevention of delirium, for analgesia, for the treatment of insomnia, and for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. 129 Recent reports have described the safe and effective use of dexmedetomidine infusions for the treatment of symptoms associated with baclofen withdrawal.109,116,126 Although the most common adverse effects of dexmedetomidine include hypotension and bradycardia, it does not induce as much respiratory depression as propofol or high-dose benzodiazepines. 129 This attribute may make it an attractive option in patients with tenuous respiratory function.

Limitations

Like other narrative reviews, this review did not follow a specific set of evidence-based criteria to select or evaluate the included references, potentially introducing bias. In addition, the lack of rigid methodology in the selection and evaluation process prevents replicability. It is possible that certain included references are not representative of the evidence base at large, and relevant references were inadvertently omitted. Finally, a systematic review and meta-analysis could have provided a quantitative summary of the literature and reported pooled analyses, which could not be presented in this narrative review.

Conclusion

Baclofen has proven to be a valuable pharmacologic agent for patients with spasticity. It has been increasingly used off-label for the management of several disorders including musculoskeletal pain, muscle spasms, AUD, chronic hiccups, GERD, and PTSD. This expansion of its use has led to an increase in baclofen-associated complications, which can be especially pronounced in patients with renal or hepatic dysfunction. Its narrow therapeutic window mandates careful dose initiation and monitoring. Both baclofen toxicity and withdrawal are life-threatening complications that require prompt recognition and a high index of suspicion. The management of baclofen toxicity is largely supportive and involves preservation of adequate circulatory and respiratory function. Baclofen withdrawal syndrome most commonly occurs in the setting of ITB administration and is most effectively treated with re-initiation or supplementation of baclofen dosing. Several pharmacologic adjuncts have been used successfully to treat the associated symptoms of baclofen withdrawal.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Jia W Romito  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5011-9179

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5011-9179

Bryan T Romito  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7178-4613

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7178-4613

References

- 1. Froestl W. Chemistry and pharmacology of GABAB receptor ligands. Adv Pharmacol 2010; 58: 19–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Entreprises Importfab Inc. Ozobax™ (baclofen) oral solution [package insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/208193s000lbl.pdf (accessed 7 January 2021).

- 3. Franchitto N, Rolland B, Pelissier F, et al. How to manage self-poisoning with baclofen in alcohol use disorder? Current updates. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9: 417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davidoff RA. Antispasticity drugs: mechanisms of action. Ann Neurol 1985; 17(2): 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Allerton CA, Boden PR, Hill RG. Actions of the GABAB agonist, (-)-baclofen, on neurones in deep dorsal horn of the rat spinal cord in vitro. Br J Pharmacol 1989; 96(1): 29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kent CN, Park C, Lindsley CW. Classics in chemical neuroscience: baclofen. ACS Chem Neurosci 2020; 11: 1740–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Albright AL, Barron WB, Fasick MP, et al. Continuous intrathecal baclofen infusion for spasticity of cerebral origin. JAMA 1993; 270: 2475–2477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Penn RD, Savoy SM, Corcos D, et al. Intrathecal baclofen for severe spinal spasticity. N Engl J Med 1989; 320: 1517–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ertzgaard P, Campo C, Calabrese A. Efficacy and safety of oral baclofen in the management of spasticity: a rationale for intrathecal baclofen. J Rehabil Med 2017; 49: 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yoon YK, Lee KC, Cho HE, et al. Outcomes of intrathecal baclofen therapy in patients with cerebral palsy and acquired brain injury. Medicine 2017; 96(34): e7472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McCormick ZL, Chu SK, Binler D, et al. Intrathecal versus oral baclofen: a matched cohort study of spasticity, pain, sleep, fatigue, and quality of life. PM R 2016; 8(6): 553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Beaurepaire R, Sinclair JMA, Heydtmann M, et al. The use of baclofen as a treatment for alcohol use disorder: a clinical practice perspective. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9: 708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Agabio R, Colombo G. GABAB receptor ligands for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: preclinical and clinical evidence. Front Neurosci 2014; 8: 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of baclofen for maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet 2007; 370: 1915–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Müller CA, Geisel O, Pelz P, et al. High-dose baclofen for the treatment of alcohol dependence (BACLAD study): a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2015; 25(8): 1167–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reynaud M, Aubin HJ, Trinquet F, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of high-dose baclofen in alcohol-dependent patients-the ALPADIR study. Alcohol Alcohol 2017; 52: 439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beraha EM, Salemink E, Goudriaan AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of high-dose baclofen for the treatment of alcohol dependence: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2016; 26(12): 1950–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Garbutt JC, Kampov-Polevoy AB, Gallop R, et al. Efficacy and safety of baclofen for alcohol dependence: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2010; 34(11): 1849–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ponizovsky AM, Rosca P, Aronovich E, et al. Baclofen as add-on to standard psychosocial treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with 1 year follow-up. J Subst Abuse Treat 2015; 52: 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Minozzi S, Saulle R, Rösner S. Baclofen for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 11: CD012557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pierce M, Sutterland A, Beraha EM, et al. Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of low-dose and high-dose baclofen in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2018; 28(7): 795–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chaignot C, Zureik M, Rey G, et al. Risk of hospitalisation and death related to baclofen for alcohol use disorders: comparison with nalmefene, acamprosate, and naltrexone in a cohort study of 165,334 patients between 2009 and 2015 in France. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2018; 27: 1239–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Naudet F, Braillon A. Baclofen and alcohol in France. Lancet Psychiatry 2018; 5: 961–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kranzler HR, Soyka M. Diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of alcohol use disorder: a review. JAMA 2018; 320: 815–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rolland B, Simon N, Franchitto N, et al. France grants an approval to baclofen for alcohol dependence. Alcohol Alcohol 2020; 55: 44–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Agabio R, Sinclair JM, Addolorato G, et al. Baclofen for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: the Cagliari Statement. Lancet Psychiatry 2018; 5(12): 957–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rigal L, Sidorkiewicz S, Tréluyer JM, et al. Titrated baclofen for high-risk alcohol consumption: a randomized placebo-controlled trial in out-patients with 1-year follow-up. Addiction 2020; 115(7): 1265–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Braillon A, Naudet F, Cristea IA, et al. Baclofen and alcohol use disorders: breakthrough or great white elephant? Alcohol Alcohol 2020; 55: 49–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Naudet F, Braillon A, Cristea IA, et al. Restoring the Bacloville trial: efficacy and harms. Addiction 2020; 115(11): 2184–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim HI, Hong SJ, Han JP, et al. Specific movement of esophagus during transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2013; 19(3): 332–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Clarke JO, Fernandez-Becker NQ, Regalia KA, et al. Baclofen and gastroesophageal reflux disease: seeing the forest through the trees. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2018; 9: 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li S, Shi S, Chen F, et al. The effects of baclofen for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2014; 2014: 307805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lidums I, Lehmann A, Checklin H, et al. Control of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations and reflux by the GABA(B) agonist baclofen in normal subjects. Gastroenterology 2000; 118(1): 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang Q, Lehmann A, Rigda R, et al. Control of transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations and reflux by the GABA(B) agonist baclofen in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut 2002; 50(1): 19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mirijello A, Addolorato G, D’Angelo C, et al. Baclofen in the treatment of persistent hiccup: a case series. Int J Clin Pract 2013; 67(9): 918–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Seker MM, Aksoy S, Ozdemir NY, et al. Successful treatment of chronic hiccup with baclofen in cancer patients. Med Oncol 2012; 29(2): 1369–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang C, Zhang R, Zhang S, et al. Baclofen for stroke patients with persistent hiccups: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Trials 2014; 15: 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mahdavinasab SM, Saghazadeh A, Motamed-Gorji N, et al. Baclofen as an adjuvant therapy for autism: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019; 28(12): 1619–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Drake RG, Davis LL, Cates ME, et al. Baclofen treatment for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann Pharmacother 2003; 37(9): 1177–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morse AM, Kelly-Pieper K, Kothare SV. Management of excessive daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy with baclofen. Pediatr Neurol 2019; 93: 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Beraha E, Bodewits P, van den Brink W, et al. Speaking fluently with baclofen? BMJ Case Rep 2017; 2017: 218714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ala S, Alvandipour M, Saeedi M, et al. Effect of topical baclofen 5% on post-hemorrhoidectomy pain: randomized double blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Gastrointest Surg 2020; 24(2): 405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bendtsen L, Zakrzewska JM, Abbott J, et al. European Academy of Neurology guideline on trigeminal neuralgia. Eur J Neurol 2019; 26(6): 831–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dapas F, Hartman SF, Martinez L, et al. Baclofen for the treatment of acute low-back syndrome. A double-blind comparison with placebo. Spine 1985; 10(4): 345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Agarwal SK, Kriel RL, Cloyd JC, et al. A pilot study assessing pharmacokinetics and tolerability of oral and intravenous baclofen in healthy adult volunteers. J Child Neurol 2015; 30(1): 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schmitz NS, Krach LE, Coles LD, et al. A Randomized dose escalation study of intravenous baclofen in healthy volunteers: clinical tolerance and pharmacokinetics. PM R 2017; 9(8): 743–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cima Labs Inc. Kemstro™ (baclofen orally disintegrating tablets) [package insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2003/21589_kemstro_lbl.pdf (accessed 7 January 2021).

- 48. Simon N, Franchitto N, Rolland B. Pharmacokinetic studies of baclofen are not sufficient to establish an optimized dosage for management of alcohol disorder. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9: 485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cangene Biopharma Inc. Gablofen® (baclofen injection) [package insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022462s000lbl.pdf (accessed 7 January 2021).

- 50. Ghanavatian S, Derian A. Baclofen. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Penn RD, Kroin JS. Long-term intrathecal baclofen infusion for treatment of spasticity. J Neurosurg 1987; 66: 181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Meulendijks D, Khan S, Koks CH, et al. Baclofen overdose treated with continuous venovenous hemofiltration. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2015; 71(3): 357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Aisen ML, Dietz M, McDowell F, et al. Baclofen toxicity in a patient with subclinical renal insufficiency. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1994; 75(1): 109–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chou CL, Chen CA, Lin SH, et al. Baclofen-induced neurotoxicity in chronic renal failure patients with intractable hiccups. South Med J 2006; 99(11): 1308–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mousavi SS, Mousavi MB, Motemednia F. Baclofen-induced encephalopathy in patient with end stage renal disease: two case reports. Indian J Nephrol 2012; 22(3): 210–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vlavonou R, Perreault MM, Barrière O, et al. Pharmacokinetic characterization of baclofen in patients with chronic kidney disease: dose adjustment recommendations. J Clin Pharmacol 2014; 54(5): 584–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Roberts JK, Westphal S, Sparks MA. Iatrogenic baclofen neurotoxicity in ESRD: recognition and management. Semin Dial 2015; 28(5): 525–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Macaigne G, Champagnon N, Harnois F, et al. Baclofen-induced acute hepatitis in alcohol-dependent patient. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2011; 35(5): 420–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Morley KC, Baillie A, Fraser I, et al. Baclofen in the treatment of alcohol dependence with or without liver disease: multisite, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2018; 212: 362–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mosoni C, Dionisi T, Vassallo GA, et al. Baclofen for the Treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with liver cirrhosis: 10 years after the first evidence. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9: 474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Boster AL, Bennett SE, Bilsky GS, et al. Best practices for intrathecal baclofen therapy: screening test. Neuromodulation 2016; 19(6): 616–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Caron E, Morgan R, Wheless JW. An unusual cause of flaccid paralysis and coma: baclofen overdose. J Child Neurol 2014; 29(4): 555–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Farhat S, El Halabi T, Makki A, et al. Coma with absent brainstem reflexes and a burst suppression on EEG secondary to baclofen toxicity. Front Neurol 2020; 11: 404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kumar G, Sahaya K, Goyal MK, et al. Electroencephalographic abnormalities in baclofen-induced encephalopathy. J Clin Neurosci 2010; 17(12): 1594–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Leung NY, Whyte IM, Isbister GK. Baclofen overdose: defining the spectrum of toxicity. Emerg Med Australas 2006; 18(1): 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nugent S, Katz MD, Little TE. Baclofen overdose with cardiac conduction abnormalities: case report and review of the literature. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 1986; 24(4): 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ostermann ME, Young B, Sibbald WJ, et al. Coma mimicking brain death following baclofen overdose. Intensive Care Med 2000; 26(8): 1144–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Parker-Pitts CK, Weymouth CW, Frawley MT. Intrathecal baclofen overdose with paradoxical autonomic features mimicking withdrawal. J Emerg Med 2020; 58(4): 616–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Slaughter AF, Roddy SM, Holshouser BA, et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy and electroencephalography in baclofen coma. Pediatr Neurol 2006; 34(2): 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sullivan R, Hodgman MJ, Kao L, et al. Baclofen overdose mimicking brain death. Clin Toxicol 2012; 50: 141–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Triplett JD, Lawn ND, Dunne JW. Baclofen neurotoxicity: a metabolic encephalopathy susceptible to exacerbation by benzodiazepine therapy. J Clin Neurophysiol 2019; 36(3): 209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wall GC, Wasiak A, Hicklin GA. An initially unsuspected case of baclofen overdose. Am J Crit Care 2006; 15(6): 611–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bowery NG. Historical perspective and emergence of the GABAB receptor. Adv Pharmacol 2010; 58: 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Cardoso AL, Quintaneiro C, Seabra H, et al. Cardiac arrest due to baclofen withdrawal syndrome. BMJ Case Rep 2014; 2014: 204322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Coffey RJ, Edgar TS, Francisco GE, et al. Abrupt withdrawal from intrathecal baclofen: recognition and management of a potentially life-threatening syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002; 83(6): 735–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cunningham JA, Jelic S. Baclofen withdrawal: a cause of prolonged fever in the intensive care unit. Anaesth Intensive Care 2005; 33(4): 534–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Freeman EH, Delaney RM. Neonatal baclofen withdrawal: a case report of an infant presenting with severe feeding difficulties. J Pediatr Nurs 2016; 31(3): 346–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Green LB, Nelson VS. Death after acute withdrawal of intrathecal baclofen: case report and literature review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80(12): 1600–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Leo RJ, Baer D. Delirium associated with baclofen withdrawal: a review of common presentations and management strategies. Psychosomatics 2005; 46(6): 503–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Levy J, De Brier G, Hugeron C, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy as a reversible complication of intrathecal baclofen withdrawal. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2016; 59(5–6): 340–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lim CA, Cunningham SJ. Baclofen withdrawal presenting as irritability in a developmentally delayed child. West J Emerg Med 2012; 13(4): 373–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Reeves RK, Stolp-Smith KA, Christopherson MW. Hyperthermia, rhabdomyolysis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation associated with baclofen pump catheter failure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79(3): 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Rolland B, Deheul S, Danel T, et al. A case of de novo seizures following a probable interaction of high-dose baclofen with alcohol. Alcohol Alcohol 2012; 47(5): 577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Sampathkumar P, Scanlon PD, Plevak DJ. Baclofen withdrawal presenting as multiorgan system failure. Anesth Analg 1998; 87(3): 562–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Watve SV, Sivan M, Raza WA, et al. Management of acute overdose or withdrawal state in intrathecal baclofen therapy. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kiel LB, Hoegberg LC, Jansen T, et al. A nationwide register-based survey of baclofen toxicity. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2015; 116(5): 452–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. De Marcellus C, le Bot S, Decleves X, et al. Report of severe accidental baclofen intoxication in a healthy 4-year-old boy and review of the literature. Arch Pediatr 2019; 26(8): 475–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Nahar LK, Cordero RE, Nutt D, et al. Validated method for the quantification of baclofen in human plasma using solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Anal Toxicol 2016; 40(2): 117–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Schulz M, Iwersen-Bergmann S, Andresen H, et al. Therapeutic and toxic blood concentrations of nearly 1000 drugs and other xenobiotics. Crit Care 2012; 16: R136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Dasarwar N, Shanbag P, Kumbhare N. Baclofen intoxication after accidental ingestion in a 3-year-old child. Indian J Pharmacol 2009; 41(2): 89–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Alvis BD, Sobey CM. Oral baclofen withdrawal resulting in progressive weakness and sedation requiring intensive care admission. Neurohospitalist 2017; 7(1): 39–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Greenberg MI, Hendrickson RG. Baclofen withdrawal following removal of an intrathecal baclofen pump despite oral baclofen replacement. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2003; 41: 83–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Mohammed I, Hussain A. Intrathecal baclofen withdrawal syndrome- a life-threatening complication of baclofen pump: a case report. BMC Clin Pharmacol 2004; 4: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Ross JC, Cook AM, Stewart GL, et al. Acute intrathecal baclofen withdrawal: a brief review of treatment options. Neurocrit Care 2011; 14(1): 103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Duncan SD, Devlin LA. Use of baclofen for withdrawal in a preterm infant. J Perinatol 2013; 33(4): 327–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Hara T, Nakajima M, Sugano H, et al. Pregnancy and breastfeeding during intrathecal baclofen therapy–a case study and review. NMC Case Rep J 2018; 5(3): 65–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Moran LR, Almeida PG, Worden S, et al. Intrauterine baclofen exposure: a multidisciplinary approach. Pediatrics 2004; 114(2): e267–e269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Ratnayaka BD, Dhaliwal H, Watkin S. Drug points: neonatal convulsions after withdrawal of baclofen. BMJ 2001; 323: 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Terrence CF, Fromm GH. Complications of baclofen withdrawal. Arch Neurol 1981; 38(9): 588–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Miracle AC, Fox MA, Ayyangar RN, et al. Imaging evaluation of intrathecal baclofen pump-catheter systems. Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32(7): 1158–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Vender JR, Hester S, Waller JL, et al. Identification and management of intrathecal baclofen pump complications: a comparison of pediatric and adult patients. J Neurosurg 2006; 104(Suppl. 1): 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Penn RD, York MM, Paice JA. Catheter systems for intrathecal drug delivery. J Neurosurg 1995; 83: 215–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Paul V, Righter K, Kim E, et al. Severe hyperthermia due to oral baclofen withdrawal. BMJ Case Rep 2020; 13: e234710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Farid R. Problem-solving in patients with targeted drug delivery systems. Mo Med 2017; 114(1): 52–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Saulino M, Anderson DJ, Doble J, et al. Best practices for intrathecal baclofen therapy: troubleshooting. Neuromodulation 2016; 19(6): 632–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Hwang RS, Sukul V, Collison C, et al. A novel approach to avoid baclofen withdrawal when faced with infected baclofen pumps. Neuromodulation 2019; 22(7): 834–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ackland GL, Fox R. Low-dose propofol infusion for controlling acute hyperspasticity after withdrawal of intrathecal baclofen therapy. Anesthesiology 2005; 103(3): 663–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Bose P, Parmer R, Thompson FJ. Velocity-dependent ankle torque in rats after contusion injury of the midthoracic spinal cord: time course. J Neurotrauma 2002; 19(10): 1231–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Defayette A, Perrello A, Brewer T, et al. Enteral baclofen withdrawal managed with intravenous dexmedetomidine: a case report. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2020; 77: 352–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Dhaliwal JS, Rosani A, Saadabadi A. Diazepam. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Dinis-Oliveira RJ. Metabolic profiles of propofol and fospropofol: clinical and forensic interpretative aspects. Biomed Res Int 2018; 2018: 6852857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Diszházi G, Magyar Z, Mótyán JA, et al. Dantrolene requires Mg2+ and ATP to inhibit the ryanodine receptor. Mol Pharmacol 2019; 96: 401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Douglas AF, Weiner HL, Schwartz DR. Prolonged intrathecal baclofen withdrawal syndrome. Case report and discussion of current therapeutic management. J Neurosurg 2005; 102: 1133–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Folino TB, Muco E, Safadi AO, et al. Propofol. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Ghiasi N, Bhansali RK, Marwaha R. Lorazepam. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Gottula AL, Gorder KL, Peck AR, et al. Dexmedetomidine for acute management of intrathecal baclofen withdrawal. J Emerg Med 2019; 58: E5–E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Horn E, Nesbit SA. Pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of sedatives and analgesics. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2004; 14(2): 247–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Roche Products Inc. Valium (diazepam) tablets [package insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/013263s083lbl.pdf (accessed 7 January 2021).

- 119. JHP Pharmaceuticals LLC. Dantrium® (dantrolene sodium) capsules [package insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/017443s043s046s048s049lbl.pdf (accessed 7 January 2021).

- 120. Keating GM. Dexmedetomidine: a review of its use for sedation in the intensive care setting. Drugs 2015; 75: 1119–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Khorasani A, Peruzzi WT. Dantrolene treatment for abrupt intrathecal baclofen withdrawal. Anesth Analg 1995; 80(5): 1054–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Kroin JS, Bianchi GD, Penn RD. Intrathecal baclofen down-regulates GABAB receptors in the rat substantia gelatinosa. J Neurosurg 1993; 79(4): 544–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Emcure Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Cyproheptadine HCl USP [package insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/087056s045lbl.pdf (accessed 7 January 2021).

- 124. Marik PE. Propofol: therapeutic indications and side-effects. Curr Pharm Des 2004; 10(29): 3639–3649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Meythaler JM, Roper JF, Brunner RC. Cyproheptadine for intrathecal baclofen withdrawal. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003; 84: 638–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Morr S, Heard CM, Li V, et al. Dexmedetomidine for acute baclofen withdrawal. Neurocrit Care 2015; 22: 288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Procter Gamble Pharmaceuticals. Dantrium® Intravenous (dantrolene sodium for injection) [package insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/018264s025lbl.pdf (accessed 7 January 2021).

- 128. Ratto D, Joyner RW. Dantrolene. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Reel B, Maani CV. Dexmedetomidine. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Roberts RJ, Barletta JF, Fong JJ, et al. Incidence of propofol-related infusion syndrome in critically ill adults: a prospective, multicenter study. Crit Care 2009; 13(5): R169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Sahinovic MM, Struys M, Absalom AR. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of propofol. Clin Pharmacokinet 2018; 57: 1539–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Stetkarova I, Brabec K, Vasko P, et al. Intrathecal baclofen in spinal spasticity: frequency and severity of withdrawal syndrome. Pain Physician 2015; 18(4): E633–E641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]