Abstract

Within the genus Trichinella, Trichinella pseudospiralis is the only recognized non-encapsulated species known to infect mammals and birds. In October 2020, larvae recovered from muscle tissues of a wolf (Canis lupus italicus) originating from Molise Region, Central Italy, were molecularly confirmed as those of Trichinella britovi and T. pseudospiralis. This is the first detection of T. pseudospiralis from a wolf. In Italy, this zoonotic nematode was detected in a red fox (Vulpes vulpes), three birds (Strix aluco, Athene noctua, Milvus milvus) and five wild boars (Sus scrofa), and was also identified as the etiological agent of a human outbreak of trichinellosis in 2015. Since T. pseudospiralis is rarely reported from carnivore mammals in comparison to the encapsulated species frequently detected in these hosts, this finding opens the question of the role of carnivores as reservoirs for this parasite.

Keywords: Trichinella pseudospiralis, Trichinella britovi, Wolf, Italy, Epidemiology, Diagnosis

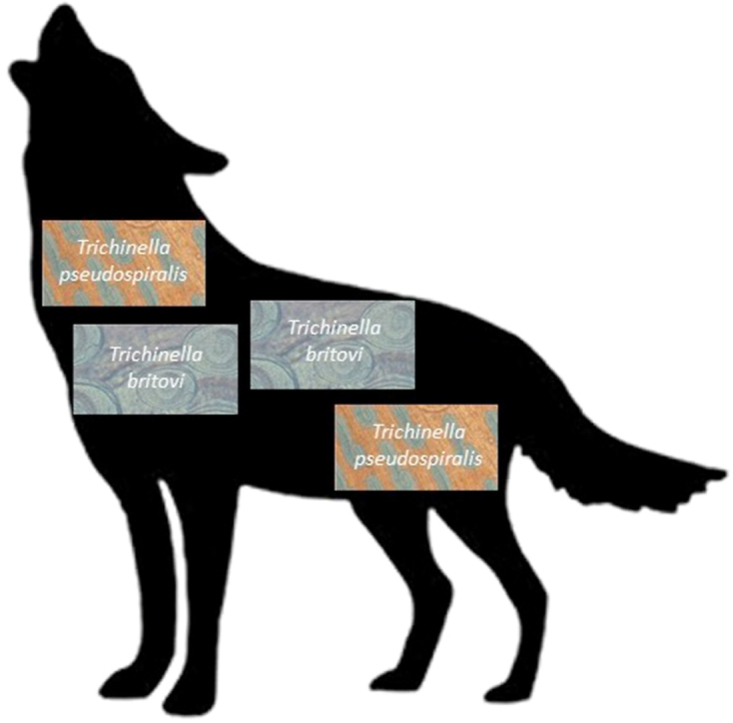

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

First report of Trichinella pseudospiralis infection in a wolf.

-

•

T. pseudospiralis is rarely documented in carnivorous mammals.

-

•

T. pseudospiralis and T. britovi mixed infection in a wolf.

1. Introduction

Trichinella spp. are the etiological agents of trichinellosis a foodborne disease of humans caused by the consumption of raw or semi-raw meat of animals infected by larvae of these zoonotic nematodes (Gottstein et al., 2009). The main reservoir hosts of these pathogens are carnivore and omnivore mammals, birds and reptiles. They are widespread on all continents except Antarctica (Pozio, 2019). Currently, ten species separated in two clades are described within the genus Trichinella. Seven species (Trichinella spiralis, Trichinella nativa, Trichinella britovi, Trichinella murrelli, Trichinella nelsoni, Trichinella patagoniensis and Trichinella chanchalensis) and three genotypes (Trichinella T6, T8 and T9) belong to the encapsulated clade infecting only mammals. The other three species characterized by the lack of the collagen capsule around the larva in the muscle cell, infect mammals and birds (Trichinella pseudospiralis) and mammals and reptiles (Trichinella papuae and Trichinella zimbabwensis) (Pozio and Zarlenga, 2013; Sharma et al., 2020).

In Europe, four species, namely T. spiralis, T. nativa, T. britovi and T. pseudospiralis, are known to circulate in wildlife and some in free-ranging and backyard pigs (EFSA, 2018; Pozio et al., 2009; Pozio, 2016). Trichinella pseudospiralis has been reported from the majority of European countries, however the real epidemiological scenario of this species remains to be defined because its detection in mammals is much lower than that of capsulated species and only a few studies regarding the role of birds in the epidemiology of this pathogen are available (Pozio, 2016). In Italy, this nematode species was reported in two owls (Strix aluco and Athene noctua), one red kite (Milvus milvus), five wild boars (Sus scrofa) and one red fox (Vulpes vulpes) (Pozio et al., 1999; Merialdi et al., 2011; Conedera et al., 2014; Pozio, 2016;Marucci et al., in press). Furthermore, in Europe, T. pseudospiralis is recognized as the etiological agent of two outbreaks of trichinellosis due to the consumption of wild boar meat, which occurred in France and Italy in 1999 and 2015, respectively (Ranque et al., 2000; Gómez-Morales et al., 2021).

The wolf is the largest extant member of Canidae native to Eurasia and North America (Carbyn et al., 1995). In the European Union, the wolf population is estimated to be around 13,000 head spread in 21 countries (European Parliament, 2018). This carnivore, at the top of the food chain, is an excellent predator but also a scavenger, and may thus play an important role as reservoir of Trichinella species in the wild. However, the protection to which the populations of this canid are subject in most of European countries, does not allow a systematic sampling to monitor the circulation of pathogens. The aim of this article was to report the first detection of T. pseudospiralis in a wolf from Italy and to review the literature on Trichinella in this carnivore mammal.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. The target host

The Italian wolf (Canis lupus italicus) differentiated in the Italian peninsula due to partial isolation and adaptation to local ecological conditions. Until the mid-ninth century, this species was widespread throughout the Italian peninsula and in Sicily, in particular in the mountainous areas of the Apennines and the Alps. However, it underwent a dramatic process of numerical reduction and range contraction restricted to a few areas from the end of the 1800 with pastoral economies, which brought the Italian population to a minimum of 100 individuals in the early seventies. Since 1971, the protection of this species, the gradual increase of wild prey, the abandonment of the mountainous areas by the resident human population and an ever greater sensitivity of the public, have allowed the numerical recovery of the population. Currently, this species is known to inhabit the whole Apennine chain, the western Alps and the central alpine sector (Galaverni et al., 2016).

In the framework of a monitoring plan on wildlife diseases in the Abruzzi and Molise regions (Central Italy), all road-kill carcasses of Trichinella-susceptible animals, those that are illegally hunted or poisoned and carcasses of euthanized injured animals collected by rangers, are sent to Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale of Abruzzo and Molise for necropsy. Striated muscles are inspected to detect Trichinella sp. larvae for epidemiological surveillance.

2.2. Diagnostic procedures

On the 12th of October 2020, a 31 kg carcass of an adult female wolf (gray coat; 5–6 years old; 60 cm high at the withers), killed by a car, was collected in the San Felice del Molise municipality, at 500 m above sea level (lat. 41.893332, long. 14.701444; Campobasso province, Molise Region, Central Italy) (Fig. 1). Five grams of tibial muscle, masseter and tongue were tested for the presence of Trichinella sp. larvae by the enzymatic digestion method according to the Commission Regulation (EC) no. 1375/2015 (European Commission, 2015). Following digestion, larvae were recovered, counted, stored in 96% ethanol and forwarded to the International Trichinella Reference Center (ITRC) (Rome, Italy) for species identification by multiplex PCR according to a published protocol (Pozio and La Rosa, 2010). A muscle sample from the tongue was sent to the Institute for Environmental Protection and Research, Ozzano dell'Emilia (Italy), for the genetic identification of the host and to establish if the animal was a pure wolf, a hybrid (wolf/dog) or a dog phenotypically similar to a wolf (Marucco et al., 2020).

Fig. 1.

Map of Italy with Trichinella pseudospiralis records. Black circle, T. pseudospiralis in hunted wild boar; open circle, T. pseudospiralis in farmed wild boar; striped circle, T. pseudospiralis human outbreak caused by wild boar meat; black triangle, T. pseudospiralis in hunted red fox; black square, T. pseudospiralis and Trichinella britovi in a wolf; black star, T. pseudospiralis in night bird of prey; open star, T. pseudospiralis in a red kite. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3. Results and discussion

The host animal was identified as an Apennine wolf (Canis lupus italicus). An average of 4.5 larvae/g were detected in the tibial muscle, masseter and tongue. The molecular identification of larvae showed a mixed infection of T. britovi and T. pseudospiralis.

As part of the Wildlife Monitoring Plan in the territory of the Abruzzi and Molise regions, 350 wolf carcasses were necropsied from 2013 to 2020 and tested for the presence of Trichinella sp. larvae. A total of 105 (30.0%) wolves were positive and Trichinella sp. larvae were recovered from 77 carcasses and identified as T. britovi or as a mixed infection of T. britovi and T. pseudospiralis (this study). Larvae collected from the other 28 wolves did not provide any results by multiplex PCR. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of T. pseudospiralis in a wolf.

During the same period, a total of 223 wild birds belonging to Strigiformes (n = 68), Accripitridae (n = 80), Falconidae (n = 59) and Corvidae (n = 16) were negative to Trichinella sp. infection. In contrast, Trichinella sp. larvae were detected in 42 (6.3%) out of 668 red foxes, 3 (1.14%) out of 264 mustelids and 26 (0.04%) out of 62,660 wild boars. Trichinella britovi was the only species identified with a similar prevalence of the infection in the same hosts in the 2004–2014 period (Badagliacca et al., 2016).

In Italy, Trichinella sp. was documented in 6 out of 6 tested wolves from Calabria and Basilicata regions (Southern Italy) from 1959 to 1975 (Gentile and Corcione, 1959; Colella and Ciufini, 1962; Corcione and Musacchio, 1966; Colella, 1975). At the time of the investigations, all Trichinella larvae were thought to be those of T. spiralis. We speculate that it was a T. britovi infection because the larvae were encapsulated and T. britovi is the only encapsulated species detected in Central and Southern Italy (Garbarino et al., 2017). From 1987, T. britovi was documented in 135 wolves from Italy as single infections (134 wolves) and a mixed infection with T. pseudospiralis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Records of Trichinella spp. in wolves according to the International Trichinella Reference Center from 1987 to 2018 and literature data (Beck et al., 2009; Airas et al., 2010; Larter et al., 2011; Teodorovic et al., 2014; Bień et al., 2016; Erster et al., 2016; Erol et al., 2021).

| Trichinella species/genotype | Country of origin | No. of records |

|---|---|---|

| T. spiralis | Croatia | 2 |

| Germany | 1 | |

| Finland | 7a | |

| Serbia | 1 | |

| Spain | 1 | |

| Total | 12 (2.2%) | |

| T. nativa | Russia | 63 |

| Finland | 53b | |

| Estonia | 20 | |

| Sweden | 15 | |

| Alaska (USA) | 11 | |

| Latvia | 3 | |

| Canada | 8 | |

| Total | 173 (32.6%) | |

| T. britovi | Italy | 135c |

| Serbia | 59 | |

| Latvia | 33 | |

| Croatia | 19 | |

| Poland | 14 | |

| Estonia | 12 | |

| Romania | 12 | |

| Sweden | 12 | |

| Finland | 11d | |

| Bulgaria | 4 | |

| France | 3 | |

| Germany | 3 | |

| Spain | 3 | |

| Ukraine | 3 | |

| Portugal | 2 | |

| Bosnia & Herzegovina | 1 | |

| Israel | 1 | |

| Republic of North Macedonia | 1 | |

| Slovakia | 1 | |

| Slovenia | 1 | |

| Turkey | 1 | |

| Total | 331 (62.3%) | |

| Trichinella T6 | Alaska (USA) | 5 |

| Canada | 9 | |

| Total | 14 (2.6%) | |

| T. pseudospiralis | Italy | 1e (0.2%) |

| Grand Total | 531 |

One double infection with T. nativa.

Of which one double infection with T. spiralis and seven double infections with T. britovi.

Of which one double infection with T. pseudospiralis.

Of which seven double infections with T. nativa.

One double infection with T. britovi.

Worldwide, Trichinella spp. were documented in 522 wolves of which 488 originated from Europe, 33 from North America and 2 from Asia (Table 1). Trichinella britovi was detected in 62.3% of wolves from 21 countries as a single or a mixed infection with T. nativa or T. pseudospiralis. Trichinella nativa was reported in 32.6% of wolves from 7 countries as a single or a mixed infection with T. britovi or T. spiralis. Trichinella spiralis was found in 2.2% of wolves from 5 countries as a single or a mixed infection with T. nativa. Trichinella pseudospiralis was detected only in association with T. britovi in the wolf reported in this study (Table 1).

Mixed infections of T. britovi and T. pseudospiralis were previously reported in 6 swine, 11 raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides), 5 lynxes (Lynx lynx), 1 badger (Meles meles), and 1 domesticated cat from Europe (Pozio, 2019). The different number of reports of T. pseudospiralis in wild boar (49 records as single infections and 3 records as mixed infections, worldwide) and the only report of T. pseudospiralis in a wolf (this study), can be explained by the millions of tested wild boar in comparison to the few hundred tested wolves, although T. pseudospiralis larvae show a very short survival time (less than 6 months) in swine (Pozio et al., 2020). No information is available on the survival time of T. pseudospiralis larvae in wolves and in carnivore mammals generally.

We can speculate that the reservoir of T. pseudospiralis must be searched in other mammalian orders other than carnivores and families other than suidae or, alternatively, no group of mammals plays the role of reservoir of T. pseudospiralis but only the role of occasional host and the real reservoir could be represented by birds. The presence of infection in birds, whose carcasses are tested very rarely compared to those of wild mammals, should be further investigated to understand the role played by birds as reservoir of this zoonotic pathogen. In fact, there have been no studies on the presence of T. pseudospiralis in birds based on a statistically significant number of analyzed animals.

No difference was observed regarding the larval distribution in the three tested muscles, but since the wolf harbored two Trichinella species, it was impossible to know the larval species distribution. In naturally-infected red foxes, the predilection muscles of T. britovi larvae is the tibial muscle, arbitrarily attributing a frequency ratio of 100 to this muscle, the frequency ratio of tongue, diaphragm and masseter was 88.4, 63.2 and 50.0, respectively (Marazza, 1960). According to Kapel et al. (2005), the predilection muscle of T. pseudospiralis larvae in experimentally-infected red foxes is the diaphragm, whereas the tibial muscle, the masseter and the tongue, rank in sixth, seventh and ninth position, respectively. In the same study, the predilection muscle of T. britovi larvae in the red fox is the tongue followed by the lower forelimb, the diaphragm, upper forelimb, upper hindlimb and masseter.

4. Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of T. pseudospiralis in a wolf. The number of reports of this Trichinella species in carnivore mammals is very low in comparison to that of encapsulated species. Experimental studies are needed to evaluate the duration of survival of T. pseudospiralis larvae in muscles of carnivore mammals and in those of birds. The results of this study suggests that carnivores, main reservoirs of the encapsulated species of the genus Trichinella, cannot be considered as sentinel animals to monitor the circulation of T. pseudospiralis in Italy and most likely in Europe. Therefore, there is an urgent need to investigate, which species of mammals and/or birds play the role of reservoir for this zoonotic pathogen in Italy and more in general in Europe and other geographical regions.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the staff of the local unit of Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale of Abruzzo and Molise for their help and cooperation. This study was supported by the Abruzzi and Molise Regions in the framework of Wildlife Monitoring Plans and by the DG SANTE of the European Commission (grants 2020–2021).

References

- Airas N., Saari S., Mikkonen T., Virtala A.M., Pellikka J., Oksanen A., Isomursu M., Kilpelä S.S., Lim C.W., Sukura A. Sylvatic Trichinella spp. infection in Finland. J. Parasitol. 2010;96:67–76. doi: 10.1645/GE-2202.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badagliacca P., Di Sabatino D., Salucci S., Romeo G., Cipriani M., Sulli N., Dall'Acqua F., Ruggieri M., Calistri P., Morelli D. The role of the wolf in endemic sylvatic Trichinella britovi infection in the Abruzzi region of Central Italy. Vet. Parasitol. 2016;231:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck R., Beck A., Kusak J., Mihaljević Z., Lucinger S., Zivicnjak T., Huber D., Gudan A., Marinculić A. Trichinellosis in wolves from Croatia. Vet. Parasitol. 2009;159:308–311. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bień J., Moskwa B., Goździk K., Cybulska A., Kornacka A., Welc M., Popiołek M., Cabaj W. The occurrence of nematodes of the genus Trichinella in wolves (Canis lupus) from the Bieszczady Mountains and Augustowska Forest in Poland. Vet. Parasitol. 2016;231:115–117. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbyn L.N., Fritts S.H., Seip D.R. Canadian Circumpolar Institute; Edmonton, Alberta: 1995. Ecology and Conservation of Wolves in a Changing World. [Google Scholar]

- Colella G. Indagini sulla trichinosi in provincia di Matera: prima segnalazione nel cane. Vet. Ital. 1975;26:371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Colella G., Ciufini F. La trichinosi della volpe e del lupo in provincia di Matera. Vet. Ital. 1962;13:955–958. [Google Scholar]

- Conedera G., Vio D., Ustulin M., Londero M., Bregoli M., Perosa G., Rigo S., Simonato G., Marangon S., Interisano M., Gomez Morales M.A., Pozio E., Capelli G. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift; 2014. Trichinella Pseudospiralis in Wildboars (Sus scrofa) of the Friuli Venezia Giulia Region, Italy. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Corcione B., Musacchio O. Contributo allo studio della trichinosis in Calabria. ATTI Soc. Peloritana Sci. Fis. Mat. Nat. 1966;12:381–385. [Google Scholar]

- Erol U., Danyer E., Sarimehmetoglu H.O., Utuk A.E. First parasitological data on a wild grey wolf in Turkey with morphological and molecular confirmation of the parasites. Acta Parasitol. 2021 Jun;66(2):687–692. doi: 10.1007/s11686-020-00311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erster O., Roth A., King R., Markovics A. Molecular characterization of Trichinella species from wild animals in Israel. Vet. Parasitol. 2016;231:128–131. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015/1375 of 10 August 2015 laying down specific rules on official controls for Trichinella in meat. Off. J. 2015;L212:7–34. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Agency The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2017. EFSA J. 2018;16:5500. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament . 2018. Research for AGRI Committee - the Revival of Wolves and Other Large Predators and its Impact on Farmers and Their Livelihood in Rural Regions of Europe.https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/191585/IPOL_STU(2018)617488_EN%20AGRI-original.pdf Policy Department for Agriculture and Rural Development Directorate-General for Internal Policies PE 617.488. [Google Scholar]

- Galaverni M., Caniglia R., Fabbri E., Milanesi P., Randi E. One, no one, or one hundred thousand: how many wolves are there currently in Italy? Mamm. Res. 2016;61:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino C., Interisano M., Chiatante A., Marucci G., Merli E., Arrigoni N., Cammi G., Ricchi M., Tonanzi D., Tamba M., La Rosa G., Pozio E. Trichinella spiralis a new alien parasite in Italy and the increased risk of infection for domestic and wild swine. Vet. Parasitol. 2017;246:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile A., Corcione B. Contributo allo studio della trichinosi in Italia: su un caso di trichinosi riscontrato in un lupo dell'Appennino silano (Canis lupus) Atti Soc. It. Sci. Vet. 1959;13:343–347. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Morales M.A., Mazzarello G., Bondi E., Arenare L., Bisso M.C., Ludovisi A., Amati M., Viscoli C., Castagnola E., Orefice G., Magnè F., Pezzotti P., Pozio E. Second outbreak of Trichinella pseudospiralis in Europe: clinical patterns, epidemiological investigation and identification of the etiological agent based on the western blot patterns of the patients' serum. Zoonoses Public Health. 2021;68:29–37. doi: 10.1111/zph.12761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottstein B., Pozio E., Nöckler K. Epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and control of trichinellosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009;22:127–145. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00026-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapel C.M., Webster P., Gamble H.R. Muscle distribution of sylvatic and domestic Trichinella larvae in production animals and wildlife. Vet. Parasitol. 2005;132:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larter N.C., Forbes L.B., Elkin B.T., Allaire D.G. Prevalence of Trichinella spp. in black bears, grizzly bears, and wolves in the Dehcho Region, Northwest Territories, Canada, including the first report of T. nativa in a grizzly bear from Canada. J. Wildl. Dis. 2011;47:745–749. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-47.3.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marazza V. La trichinosi delle volpi in Italia. Arch. Vet. Ital. 1960;11:507–566. [Google Scholar]

- Marucci G., Romano A.C., Interisano M., Toce M., Pietragalla I., Collazzo G.P., Palazzo L. Trichinella pseudospiralis in a red kite (Milvus milvus) of Italy. Parasitol. Res. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00436-021-07165-0. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marucco F., La Morgia V., Aragno P., Salvatori V., Caniglia R., Fabbri E., Mucci N., Genovesi P. Institute for Environmental Protection and Research; 2020. Guidelines and Protocols for the National Monitoring of the Wolf in Italy; pp. 1–98.https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/files2020/notizie/linee-guida-e-protocolli_monitoraggio_lupo.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Merialdi G., Bardasi L., Fontana M.C., Spaggiari B., Maioli G., Conedera G., Vio D., Londero M., Marucci G., Ludovisi A., Pozio E., Capelli G. First reports of Trichinella pseudospiralis in wild boars (Sus scrofa) of Italy. Vet. Parasitol. 2011;178:370–373. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozio E. Trichinella pseudospiralis an elusive nematode. Vet. Parasitol. 2016;231:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozio E. Trichinella and trichinellosis in Europe. Vet. Glas. 2019;73:65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pozio E., Goffredo M., Fico R., La Rosa G. Trichinella pseudospiralis in sedentary night-birds of prey from Central Italy. J. Parasitol. 1999;85:759–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozio E., La Rosa G. Trichinella. In: Liu D., editor. Molecular Detection of Foodborne Pathogens. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2010. pp. 851–863. [Google Scholar]

- Pozio E., Merialdi G., Licata E., Della Casa G., Fabiani M., Amati M., Cherchi S., Ramini M., Faeti V., Interisano M., Ludovisi A., Rugna G., Marucci G., Tonanzi D., Gómez-Morales M.A. Differences in larval survival and IgG response patterns in long-lasting infections by Trichinella spiralis, Trichinella britovi and Trichinella pseudospiralis in pigs. Parasites Vectors. 2020;13:520. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-04394-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozio E., Rinaldi L., Marucci G., Musella V., Galati F., Cringoli G., Boireau P., La Rosa G. Hosts and habitats of Trichinella spiralis and Trichinella britovi in Europe. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009;39:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozio E., Zarlenga D.S. New pieces of the Trichinella puzzle. Int. J. Parasitol. 2013;43:983–997. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranque S., Faugère B., Pozio E., La Rosa G., Tamburrini A., Pellissier J.F., Brouqui P. Trichinella pseudospiralis outbreak in France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2000;6:543–547. doi: 10.3201/eid0605.000517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R., Thompson P.C., Hoberg E.P., Scandrett B.W., Konecsni K., Harms N.J., Kukka P.M., Jung T.S., Elkin B., Mulders R., Larter N.C., Branigan M., Pongracz J., Wagner B., Kafle P., Lobanov V.A., Rosenthal B.M., Jenkins E.J. Hiding in plain sight: discovery and phylogeography of a cryptic species of Trichinella (Nematoda: trichinellidae) in wolverine (Gulo gulo) Int. J. Parasitol. 2020;50:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2020.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teodorović V., Vasilev D., Ćirović D., Marković M., Ćosić N., Djurić S., Djurković-Djaković O. The wolf (Canis lupus) as an indicator species for the sylvatic Trichinella cycle in the Central Balkans. J. Wildl. Dis. 2014;50:911–915. doi: 10.7589/2013-12-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]