Abstract

While a considerable research base demonstrates the positive effects of 8-week secular mindfulness courses, it remains unclear to what degree their participants continue to engage with mindfulness practices; and there is a dearth of published reports on longer-term mindfulness interventions. Studies have also tended to focus on clinical “effectiveness,” with less attention given to participants’ own construal and expectations of mindfulness. To address these gaps, the study reported here implemented a year-long mindfulness program for a group of 20 individuals with long-standing health conditions who gradually transitioned to self-guiding. Their experiences, expectations, and understanding of mindfulness were investigated through the lens of descriptive phenomenology. The findings revealed that mindfulness practice did bring therapeutic improvement but that it was a multi-faceted process where an individual’s intentionality toward practice was key, with a clear division between those pursuing an “embodied integrated” mindfulness and those viewing it as a stress management tool.

Keywords: mindfulness, chronic illness, experiential learning, qualitative research

Background and Rationale

Mindfulness: Orientation to Experience

Mindfulness in the form of short, secular mindfulness-based courses is now a global phenomenon. Its current instantiation in the West largely derives from the Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction program (MBSR) spearheaded by Kabat-Zinn in the 1970s to relieve suffering in heterogeneous patient populations, particularly those with chronic conditions for whom the health system had little left to offer (Kabat-Zinn, 2013). Kabat-Zinn (2003) has provided a succinct “operational” definition of mindfulness as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (p. 145). While some Buddhist scholars (e.g., Dreyfus, 2011) have questioned whether the understanding of mindfulness as present-centered, nonjudgmental awareness fully represents how mindfulness is described in the early Buddhist texts, this definition, with its particular understanding of what experiential learning entails, has prevailed in current therapeutic programs of mindfulness. Key to mindfulness practice is not only the regulation and flexible deployment of attention, but also the cultivation of compassion toward oneself and “an orientation that is characterized by curiosity, openness, and acceptance” (Bishop et al., 2004, p. 232). Rather than seeking to avoid suffering, it encourages an approach toward, and compassionate observation of, pain and difficulties. As van der Meide et al. (2018, p. 2247) have observed, mindfulness aims to integrate mind and body rather than control the body.

Viewed from the lens of phenomenology, participants in a mindfulness course are, in effect, being asked to change their ontological orientation to experience. Indeed Kabat-Zinn (2003) himself recognizes in one of his articles that: “the term ‘practice’ . . . is better understood as a way of being, a way of seeing, which is embodied, inhabited, grown into through the implementation of the methods and techniques that comprise the discipline” (p. 148). Building on Kabat-Zinn’s definition, Shapiro et al. (2006) have posited that the construct of mindfulness involves three intertwined components: intention, attention, and attitude. They note that the intention, “the personal vision,” which underlies an individual’s engagement with mindfulness “is often dynamic and evolving” (p. 375). They see the conjoined operation of these three components as leading to a reperceiving of experience, “a profound shift in one’s relationship to thoughts and emotions” (p. 379).

On our reading then, mindfulness as it is understood within the MBSR and Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) programs calls for a specific ontological orientation to self, experience, and the world. However, as Hayes and Wilson (2003) observe: “mindfulness is treated sometimes as a technique, sometimes as a more general method or collection of techniques, sometimes as a psychological process that can produce outcomes, and sometimes as an outcome in and of itself” (p. 161).

Effectiveness—But for How Long?

Research on mindfulness programs has centered on determining their effectiveness, with a generally positive picture emerging, from a large number of individual studies and meta-analyses, of benefits in relation to specific conditions, such as: anxiety and low mood (Vøellestad et al., 2011), depression (van der Velden et al., 2015), and pain (Goyal et al., 2014). Benefits have been seen to cover a wide spectrum of conditions and problems (Grossman et al., 2004; Hofmann et al., 2010, p. 180).

Most findings on health effects have been limited to the immediate postintervention period and overall evidence for long-term improvement is modest (Bohlmeijer et al., 2010; Chiesa & Serretti, 2010). A number of studies, however, indicate the potential for sustained benefit beyond 6 months in respect of psychological (e.g., Hofmann et al., 2010), cognitive (e.g., Johns et al., 2016), and physical well-being (e.g., Cherkin et al., 2017).

While this picture is heartening, some cautionary notes need to be introduced. MBSR and MBCT courses have multiple elements. In MBSR, these include systematic scanning of sensations in the body, mindful attention to the breath, tracking of the moment-by-moment flow of thoughts and feelings, and gentle yoga stretches. It is not clear which of these components might be most effective for healing in general and for specific populations, including those living with enduring conditions. The focus of much research on the relief of symptoms means that less attention is given to the wider effects of mindfulness, to how it may potentially refigure subjective experience to a degree and shift one’s horizons.

The extent to which participants continue to practice after an 8-week course is unclear. Goleman and Davidson (2017, p. 166) note that although continuity of practice is key to long-term benefit, “we still have virtually no good information on the extent to which those who have taken an MBSR course continue to engage in formal practice in the years following their initial training.” The 8-week length of courses, which is treated as a default setting across the majority of mindfulness interventions, can be viewed as “the equivalent of a ‘low-dose, short-term’ trial of a medication” (Goleman and Davidson, 2017, p. 194). There would appear to be a clear case for instituting, and exploring the effects of, much longer interventions—an exercise that would also provide greater knowledge of the experiential process of learning mindfulness over time. The following sections describe how we took up this challenge.

Our study had another key objective. Writing in this journal in 2005, Bruce and Davies observed that “there is little research that examines the lived experience of mindfulness and its meaning for those who practice it” (1329). While research on the lived experience of mindfulness has increased over the last decade, for example in Doran’s (2014) study published in this journal of a mindfulness-based approach to back pain, this observation still has considerable force. Accordingly, we set out to explore as a central question: how did participants in the intervention themselves experience and understand mindfulness? Did they view it as a set of helpful techniques or as a mode of being? What intentions, what personal projects did they pursue in mindfulness practice?

Focus and Aims of the Study

A key element of the study reported here was the development of a longer-term intervention. This longer-term intervention in turn allowed a close exploration over time of how its participants learned mindfulness, experienced the group process and used the practices in everyday life. The preceding section has established that the focus of previous research has been directed on clinical outcomes, to the effects of a psycho-educational treatment on individuals. By contrast, this study is grounded in the perspective that a mindfulness “treatment” is not simply received by program participants. Rather, they need to make their own personal sense of what mindfulness means, and how it fits, or fails to resonate with, the horizons of their life. Guided by a focus on the fine-grained investigation of participants’ encounters with, and construal of, mindfulness, the study sought to explore the nuances of their understanding of mindfulness and the meanings and emotions that they associated with it.

A descriptive phenomenological research study, where the focus is on the fine-grained, systematic exploration of participants’ experiences and how they relate to a particular phenomenon, appeared to be the most apposite choice for this line of enquiry. The ontological orientation and practices of descriptive phenomenological research also resonate with the accent in mindfulness practice on attending to, and apprehending, the flow of experience and the objects of consciousness.

Accordingly, a longitudinal, phenomenological study was deployed to explore the experiential process of learning mindfulness as perceived by a group of people with enduring conditions, identifying barriers and supports to practice and examining the degree to which self-guiding would lead participants to embed mindfulness practice. We also aimed to discover how the nature and context of the program, including the language that was employed and group dynamics, influenced participants’ intentions and motivations toward mindfulness practice.

Research Design

The longitudinal, phenomenological research design was based on descriptive phenomenology (Ashworth & Ashworth, 2003; Giorgi, 1997). Descriptive phenomenological analysis seeks to create rich descriptions of experiences and their underlying structures that encompass multiple layers of meaning (Finlay, 2011). The interpretive role of the researcher is acknowledged but the “phenomenological attitude” is adopted to minimize overt influence on the processes of data generation and analysis (Finlay, 2012).

A central feature of the design was the consideration given throughout the data creation and analysis to reflexivity. This involved several elements, including attention to our: subject positions as researchers, values, relationship to the topic, and frameworks of interpretation.

As committed practitioners of mindfulness ourselves, we cannot claim that we were able to escape the perspective that this gave us on the topic, but it was necessary for us to be as conscious as we could be of the preconceptions that we were bringing to the study concerning mindfulness and its effects. To pursue our aim of creating a trustworthy study, we needed to continually question and critically examine our research actions and in particular our processes of inferencing and reasoning at the stage of analysis. This involved maintaining a balance between “retaining wonder and openness to the world while reflexively restraining preunderstandings” (van Wijngaarden et al., 2017, p. 1741).

Intervention: Rationale and Design

The longer-term intervention that featured in this study drew on the understanding of mindfulness and the practices of the MBSR program set out by Kabat-Zinn (2013). MBSR emphasizes the internal resources of participants and an experiential learning process that fosters a change in how one relates to thoughts and emotions. The extension, however, ensured that participants were not dropped in at the deep end. Instead, there was a gradual, staged transition toward the participants themselves taking on an active role in guiding practice.

The program comprised 34 sessions delivered over 1 year. Table 1 sets out the sequence of the sessions and summarizes the six phases of the research process.

Table 1.

Data Collection Activities Aligned to the Different Phases of the Intervention.

| Research phase | Data collection activities and time data collected | Numbers interviewed |

|---|---|---|

| PHASE 1—Preprogram Screening/Baseline Assessment | Health Agenda/Demographic Interview/Individual Interview | 26 applied of whom 20 met study criteria |

| PHASE 2 9-Week MBSR course 8 weekly 2½ hour sessions plus day retreat | Three Focus Groups (3 weeks) 1:1 Embodied Interviews (9 weeks) |

17 18 |

| PHASE 3—Consolidation of training 1½ hour fortnightly sessions | Three Focus Groups (4 months) | 14 |

| PHASE 4—Supported Transition to

self-led (½ hour fortnightly sessions |

Individual Interviews (9 months) | 12 of which two were withdrawal interviews |

| PHASE 5—Self-led—11 Weekly (1½

hour) sessions and 3 half-day retreats |

— | — |

| PHASE 6—Postproject period | 1:1 Embodied Interviews (1 year) | 10 |

Note. MBSR = mindfulness based stress reduction program.

Phase 1 involved recruitment, screening, and the gathering of baseline data. Phase 2 consisted of an intensive 9-week introductory course in MBSR. After this MBSR course, sessions were shortened to 1½ hours and took place fortnightly. Phase 3 was a 3-month period of consolidation to help participants build confidence in the methods taught. During the 8 weeks of Phase 4, groups of three participants took turns to guide meditation practice with mentoring support from the teacher. The groups were completely self-led during the three months of Phase 5 which included three half-day retreats and a return to a weekly format. The mindfulness teacher maintained contact in Phase 5 by attending the monthly half-day retreats.

The mindfulness teacher met the U.K. recommendations for good mindfulness teaching practice (United Kingdom Network of Mindfulness Teacher Training Organisations, 2015). Her experience included extensive practice as a nurse working with people with enduring conditions and leading mindfulness group programs within this context.

Ethics

Ethical approval was gained from the University and National Health Service Research Ethics committees. Ethical principles to exercise a duty of care and safeguard the public interest were upheld in line with the U.K. Nursing and Midwifery Code (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2008). Ethical conduct was seen as involving more than simply observing established principles. In line with the spirit of mindfulness practice, acting in an ethical manner called for a close, sustained attentiveness, and responsiveness to the needs and experiences of participants, for an “ethics of care” (Tronto, 1993).

Participants

The study set out, via local publicity, to recruit individuals with different long-term conditions who were new to mindfulness. Twenty-six people (12M: 14F) attended a briefing meeting where they received information about mindfulness and the study and were issued with consent forms. They were informed that they could withdraw at any time and that confidentiality would be assured. Three women were excluded due to prior mindfulness experience and three decided not to take part, leaving 20 participants (10M: 10F).

Socio-economic, education, and religious status varied. Eleven were not working, primarily due to medical retirement. Ages ranged from 36 to 73 years, with a median age of 50 years. Seventeen participants were of white, British origin, and there were two white Europeans and one participant of South Asian origin. The participants identified their religious affiliation, as follows: no religion (n = 9), Christian (n = 7), Muslim (n = 1), and some form of Spirituality (n = 5). The common denominator was the experience of living with chronic illness. Primary conditions included: severe anxiety, depression, cancer, bronchiectasis, heart disease, fibromyalgia, and multiple sclerosis. Multiple conditions were reported by all but three individuals. The relationship between physical and psychological ill-health was evident, with stress, fatigue, and low mood being common. Frequent physical pain affected a third, and sleeplessness three-quarters of the group.

Attrition

To address the question of the degree to which participants may sustain attendance in a longer-term program, it is important to give a detailed account of attrition. A range of factors impacted upon attendance and attrition was gradual (Table 2). One woman came once and another dropped out after 3 weeks, the former due to illness and the other due to uncertainty about the program. The remaining 18 people completed the 9-week MBSR course. (As a point of comparison with “standard” length MBSR courses, Ledesma and Kumano (2009, p. 574) found in their meta-analysis of MBSR courses for individuals with cancer a mean drop-out rate of 23%). During the consolidation period, there were a further four departures (1M:3F); and in Phase 4, three men left. The 11 (6M:5F) who continued into Phase 5 stayed until the end although one woman managed only two meetings due to ill-health and hospitalization and was unable to give a final interview. Follow-up was attempted with all nine program leavers, and interviews sought to gain insight into why they decided to exit the program. Two participants (who withdrew in Phase 4) agreed to a recorded interview and five informally related their reasons.

Table 2.

Attrition During the Project and Reasons for Leaving.

| Participant withdrawals | Reason for leaving |

|---|---|

| Phase 2 (n = 2) | Ill-health (n = 1); unsure about program (n = 1) |

| Phase 3 (n = 4) | Program delivery (n = 2); no reason given (n = 2) |

| Phase 4 (n = 3) | Ill-health/social reasons (n = 1); lack of belief in program (n = 2) |

| Phase 5 (n = 1) | Ill-health/ hospitalization |

Methods

Data Collection

Data collection took the form of semistructured interviews, focus groups, and embodied interviews (EIs); and observations of the sessions by Gillian Mathews that informed these primary sources of data. The combination of these data collection methods enabled different facets of the participants’ encounters with mindfulness to come into view. The focus group and EI techniques were piloted in advance of the main study.

Semi-structured Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were employed twice: in Phase 1 to gain insight into participants’ (n = 26) circumstances and to provide a benchmark against which later experience could be assessed; and at 9 months in Phase 4 (n = 12) to obtain a general update on experience following the first phase of self-guiding. An empathic manner was adopted to help put participants at ease and open-ended questions aimed to elicit in-depth accounts of their experiences.

Embodied Interviews

Developed within the phenomenological research tradition, EIs have as their “pivotal point . . . the participant’s experiential, embodied involvement in the issues of the research interview” (Stelter, 2010, p. 859). Their aim is to assist participants to connect with and bring into language their experience of embodied practices, such as mindfulness meditation. EIs took place at the conclusion of the MBSR program (n = 18); and in Phase 6, one-month postcompletion (n = 10). These interviews sought nuanced information on the subtle aspects of mindfulness experience, using techniques from Focusing (Gendlin, 1996) and features of Stelter’s (2010) approach. The processes of embodied interviewing were refined in the light of findings from pilot interviews and from the knowledge and experience gained by Gillian Mathews who undertook a year-long certificated training in Focusing. To bring awareness to the body, these interviews included an initial 10 minutes of meditation.

Focus Groups

Two sets of focus groups were conducted (n = 6). The first set (n = 3) gave insight into early program experience during Phase 2. The second set (n = 3) in Phase 3, covered the period of consolidation following the initial MBSR course and asked participants about the pending move to the self-guiding format.

Data Analysis

All the interviews were fully transcribed and data were anonymised prior to analysis. The same analytical process was applied, both within, and across, the interview data sets. Analysis used the phenomenological reduction which entails close description, horizontalisation to avoid the creation of meaning hierarchies, and verification of individual participant accounts (Giorgi, 1985). This positioned the analytical focus of the investigation in line with the research aims and questions, while still allowing scope for the “discovery orientation” of phenomenological investigation (Giorgi, 1997).

Once they had been analyzed in this manner, the data sets for each person were brought together to create an individual account of mindfulness experience over the year. These individual accounts were then examined using the lens of the Lifeworld fractions (Ashworth, 2003) to encapsulate the different aspects of individuals’ experiences of mindfulness. The fractions also provided a structure for the next stage of analysis which involved coalescing participant accounts and identifying shifts over time, commonalities, continuities, and key areas of difference across the group.

The Lifeworld fractions were developed as a heuristic scheme to assist the analysis of an individual’s lifeworld and have been used previously to explore long-term illness experience (Ashworth & Ashworth, 2003). They derive from a synthesis of the work of phenomenological and existentialist philosophers, in particular from the writings of Merleau-Ponty (1962/1945), and are seen to encapsulate central features of human experience, enabling “the detailed description of a given lifeworld to be undertaken in a thorough and phenomenological manner” (Ashworth, 2003, p. 147). The seven fractions are: selfhood (social identity, sense of agency), sociality (how a situation affects relations with others), embodiment (feelings about one’s body), temporality (sense of time), spatiality (understanding of place/space), discourse (terms available to construe one’s experience), and project (intentionality, and ability to carry out activities that an individual has committed to) (Ashworth, 2003, pp. 148–150).

The individual elements and overall form of this analytical scheme fitted well with the range of topics of interest in this study. Employing it enabled a comprehensive picture of participants’ experiences of mindfulness to emerge. It provided a clear structure for analysis that aided the synthesis of data, allowing both variability in experience, across time and between participants, and common patterns to be articulated.

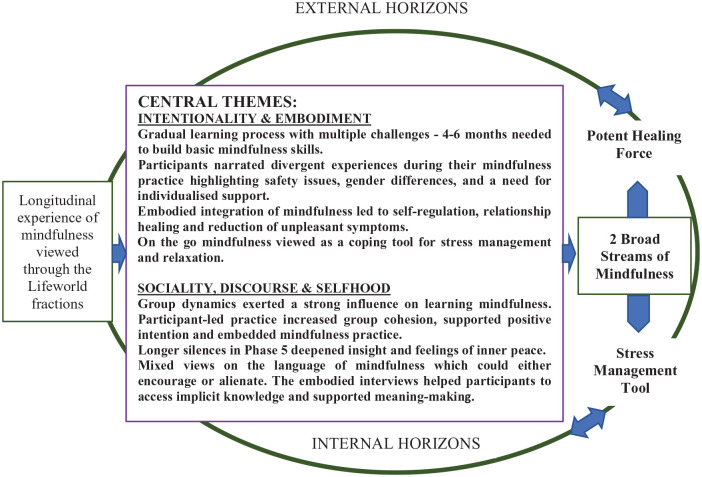

As the following pages reveal, a central area of contrast emerged in participants’ intentionality toward practice which led in turn to different trajectories of engagement with mindfulness. The different threads of participants’ experiences of mindfulness were closely intertwined. For the purposes of clear, coherent exposition, they needed both to be teased out and have their interconnections made visible. Accordingly, the following sections organize findings under the different Lifeworld fractions which allowed individual features to be foregrounded, without losing sight of their position within a wider horizonal landscape. Central themes are depicted in Figure 1. As befits a longitudinal study, the findings concerning temporality were woven into all of the Findings sections.

Figure 1.

Central themes depicted through the lens of the Lifeworld fractions.

Findings

Intentionality and Embodiment

Before the intervention, participants described considerable physical and psychological suffering that constricted their lives. Pain, debility, tiredness, anxiety, and low mood were part of daily living:

I cannot sit for too long . . . It’s just difficult to control it, so I have to do something. If I move, at least I forget about the pain. [Participant, Pre-programme]

Initial intention toward mindfulness was characterized by a quiet optimism. Participants wanted to build personal strengths and develop tangible skills. A common hope was for some benefit in terms of symptom and medication reduction but regaining personal control over health and well-being was key. Expectations were modest:

If it helps me in any way, even just . . . finding something that helps handle illness. If things stay the same, fine, but if not, okay. [Participant, Pre-programme]

The process of turning inwards intensified awareness of mental and physical events and participants reported fluctuating experiences during meditation. For a small number, it instilled positive feelings which helped to calm mental activity and bring about some bodily relaxation. Wrestling with mental conflicts was, however, common and, particularly for those for whom anxiety was a primary condition, the practice exacerbated symptoms creating uncertainty about how to manage emotions:

When I suffer from really bad periods of panic and anxiety, you’re very, very breathless, and trying to breathe to slow it down, it actually, kind of makes it worse . . . ‘Cos you’re even more aware that you’re breathless so I was struggling with, ehm, just being able to concentrate on the breathing. In fact, I left last Monday and I thought, “I don’t know if I can continue with this to be honest” ‘cos I actually felt really anxious about it by the time I got home and I hadn’t been feeling anxious at all [laughter]. [Participant, 3 Weeks]

Although most participants felt motivated to attend the MBSR meetings, setting aside protected time to practice meditation at home proved significantly more difficult. Levels of engagement were affected by: individual perceptions of mindfulness, early experience on the program, and the escalation of health conditions and intervening life circumstances. A popular, pragmatic way of addressing the home practice issue was to use shorter practices:

I’ve discovered that I’m more the short time person, like the ten-minute meditation or a shorter body scan; and I use that a lot. I think, I’m using it much more than I thought I would use it. It’s allowing me to stop, and take a note of how I am, and what’s going on. [Participant, 9 weeks]

When the introductory course ended, mindfulness was generally viewed as a coping tool for stress through increased awareness and relaxation. These positive gains plateaued, however, and group members who had developed a consistent approach during the MBSR course subsequently found their routines fractured by a recurrence of old habits, difficult life events, and ill-health. Virtually everyone gravitated toward short, informal exercises that could be more readily integrated into everyday life. Later, at 4 months, a general consensus existed that mindfulness offered meaningful techniques to manage stress and aid personal healing, but it was perceived that several months were needed to embed a basic skill set. The value of continuing beyond the MBSR program to consolidate learning was key:

I think this whole mindfulness thing, it’s like learning how to play golf. You spend six months on the practice field learning how to hit a ball and it’s not until you learn how to hit a ball that you can then learn how to actually start playing golf which is getting underway on the golf course . . . and with this whole thing of mindfulness you’ve got to learn the basic building blocks first before you can then begin to apply it. [Participant, 4 Months]

At 9 months, the group remained divided in terms of undertaking home practice with half of the remaining participants (n = 5) using mindfulness on an informal, ad hoc basis with the occasional sitting meditation or body scan while the rest (n = 6) had a daily routine. Residual benefit from the introductory program and attending the fortnightly sessions appeared to support mindfulness in daily life but more pronounced health benefits and an ability to cope with emotional turmoil and difficult life events were only reported by those who regularly engaged in the longer (30–60 minute) formal practices, that is, the body scan, sitting meditations, and mindful movement. One participant, who had tussled with mindfulness for the greater part of the year, encapsulated the difference between formal meditation and a sporadic informal approach:

There’s a definite difference . . . I still do feel better after formal practice. I feel more warmth and I feel calmer and a lot more at peace and more energised. I think the informal practice, it just gets me through things. It doesn’t give me that whole sense of feeling more satisfied. It just really lets me accept the situation more, and just get on with things. The informal practice is helpful but much more satisfaction is gained from the formal practice when it’s done. [Participant, 1 year]

This pattern continued until the end of the program when two core streams of experience were identified: (a) embodied integrated mindfulness (n = 5) and (b) mindfulness as a stress management tool (n = 5). Those who continued to practice meditation regularly and build mindfulness skills appeared more attuned to the body.

The overriding feeling from mindfulness is shared peace, I think. Absolute peace. And relaxation [felt] all over, but it’s just sensory in the body. Probably in the belly, abdomen area, lower abdomen. It’s just quite wonderful. [Participant, 1 year]

A relationship between the depth and amount of practice over time and improved well-being was indicated:

My body says it needs it [mindfulness practice], daily. You can gain the kind of feeling . . . kind of serenity or being at peace, or being content. You can get a relaxed state, but by saying all that . . .you also have to realise that it’s got to be practiced and worked at and you sometimes don’t get any of that for weeks and weeks, and weeks, and then one day you do get it. [Participant, 1 year]

Contrastingly, the participants who employed an ad hoc approach to mindfulness described some residual benefit from the MBSR course and fortnightly meetings but improvements were less pronounced:

Not much. More sort of on-the-go practice. It feels enough . . . in my head . . . enough to keep the stress away and give some relaxation. [Participant, 1 year]

Choice over how to employ mindfulness was very important at the individual level. It was apparent that there was a fine line to walk between not putting unhelpful pressure on oneself to practice while acknowledging that regular meditation brought greater well-being.

Sociality, Selfhood, and Discourse

Group dynamics exerted significant influence on participants, both helping and impeding their development of mindfulness. Impeding factors were unfamiliarity with mindfulness and the group; the presence of individuals who talked at length, triggering a degree of recoil; resistance to elements of the course delivery, language and content; and the key tenet of invitational process, that is, that one only speaks if one really wants to.

Tensions were observed in the group when members expressed contrasting views, a person spoke extensively, or a lengthy silence followed a request for feedback from the facilitator. Such situations called for skillful, sensitively judged action on the part of the facilitator. A few participants talked about feeling impelled to speak out simply to fill an awkward silence, while others deliberately held back:

I’ve found that I’m probably behaving differently as I would at other times. [Participant, 3 Weeks]

It’s feeling a bit like being back at school. It’s odd. Very odd. Not wanting to speak up, you know, knowing the answer but not wanting to speak up. [Participant, 3 Weeks]

These exchanges point up the need to give attention in both research and practice to how individual participants appraise the group process in mindfulness courses and to how these appraisals will be shaped by their personal history and the wider horizons of their lives.

A difference was noted between those group members who wished for greater social interaction to build familiarity and deepen connection and others who were quite happy to maintain the status quo. More intimate sharing in small groups and pairs was appreciated by the women, whereas most of the men found it unhelpful. At 2 months, it was evident that the group was still at a relatively formative stage:

I think it feels probably more like a collection of individuals than a cohesive group. I think probably there’s a lot of different people with different experiences and different levels of comfort getting to know other people. I think that’s fine and it’s a group that only meets once a week so it’s not been that long that they’ve been together, things take time. [Participant, 2 Months]

There were varying perceptions of the dialogue in the group and its benefits, as can be seen in the tensions captured in the following interview extract:

I found the sharing sometimes excruciating, cringing. It just makes me want to go . . . hide in a way, I suppose. It just doesn’t fit with me. And then other people say . . . you know, they can say things that really hit home and sometimes when people speak up, what I was just about to say myself, so there can be like . . . if you like, it’s a mixture of like minds and unlike minds. [Participant, 2 months]

Group cohesion was observed to develop gradually as individual participants navigated a unique path through conflicting perspectives on, and divergent encounters with, mindfulness. By 4 months, participants talked more readily about how words used within everyday life elicited specific responses and reactions. By adopting a wiser response potentially difficult interactions were ameliorated, leading to improved harmony in relationships. The presence of mutual suffering offered a tenuous bond and at the same time the benefits of the diversity in participants’ conditions were highlighted. This diversity was seen to guard against the danger of unhelpful comparisons and corresponding pressure to achieve.

I think the anonymity of what people’s conditions are, what people bring, I think that privacy has been crucial. If it had been people in the group who all had the same as me I think that would have been more difficult. For me that would have been a measure of whose chronic fatigue is worse or getting better or whose pain is getting worse or better. I think it’s for me, because the group’s diverse and everybody has their own issues I think I’ve worked better in that group. . . .the “should” part of doing more might have been worse if there was people with my condition getting better before me. [Participant, 2 Months]

At the end of the program participants identified a marked contrast in group experience compared to the beginning. Going through the process together with those who sustained commitment over the year was perceived as “uplifting” and represented “a big contrast to the acute awkwardness of the early phases which were characterised by considerable tensions, frustration and withdrawal.” [Participant, 1 Year].

The experience of change over time is exemplified by this participant:

I don’t know if I feel a total part of the group. I’m quite quiet in the group, yeah. I sometimes feel nervous to speak out in front of the group. . . I don’t know why that is. [Participant, 2 months]

After about halfway through, I certainly felt just a normal member of the group. I think perhaps as I felt more comfortable in the group, maybe it became more significant and became more powerful . . . Maybe all the anxieties have gone and you’re more comfortable in that situation, or maybe just with practice, things just got better. [Participant, 1 year]

Leading practice together appeared to motivate attendance and intentionality toward mindfulness. It also increased comfort levels across the group. Guiding the different exercises engendered the confidence to shape practice to what worked best at a personal level rather than striving to achieve a perceived “right way” to do it:

I think it’s [mindfulness practice] become more towards the end, going on towards the end of the year, and possibly more from being actually directly involved in leading a practice, rather than necessarily being led. [Participant, 1 year]

Mindfulness practice in the group was observed to develop significantly in the last quarter. Meetings became filled with silent, shared space and the need for words was relinquished. These longer periods of silence were cited by participants as important to embed skills and deepen practice.

Discourse

The language of mindfulness elicited a mixed response. It influenced participant intention toward mindfulness practice and the process of making meaning. Forms of expression used in the practices and teachings contained unfamiliar terms and some participants struggled to understand and connect to these. Those who grasped the general nub found participation easier; and many found the invitational language helpful. It took away the pressure of “having to do” home practice and was cited by some participants as key in helping them to embrace this:

I know it’s the language that’s used . . . Everything’s an invitation, everything feels it belongs to me, and I have the control to learn, and, you know . . . What’s the word? It’s basically, to be open. For me to be open spiritually, physically, and mentally, to hear what the teachings are about. I think the poetry is wonderful. [Participant, 3 Weeks]

Others found the approach: “sugar-coated” and “New Ageist” [Participants, 3 Weeks]. It was considered that Scots are characterized as quite reserved and less open to this form of intervention:

It’s that sort of “touchy feelyness” that probably we’re not all very . . . us Scots particularly aren’t very good at and if it’s maybe not been in your upbringing. [Participant, 3 Weeks]

Such reactions could be read as indicating that these participants simply needed to habituate to the lexis and forms of expression of mindfulness. However, when one recognizes that “the speaking of a language is part of an activity, or of a form of life” (Wittgenstein, 1958, p. §23), it is clear that more is at stake here. The forms of expression, lexis, norms, and processes of group interaction, in mindfulness courses can be seen to be integral parts of what the sociolinguist Gee (2008) has termed a capital “D” Discourse. A capital “D” Discourse is:

composed of distinctive ways of speaking/listening coupled with distinctive ways of acting, interacting, valuing, feeling, dressing, thinking, believing, with other people and with various objects, tools, and technologies, so as to enact specific socially recognizable identities engaged in specific socially recognizable activities. (155)

Gee makes a distinction between primary discourses that are acquired in an immediate family and community of origin and secondary discourses that are then acquired in different contexts. This distinction brings out clearly how for some participants their preceding enculturation led them to find the ways of speaking, interacting, and enacting an identity in the secondary discourse of mindfulness somewhat challenging, while others experienced an easier transition.

Discussion

Overview

In this study, the development of a long-term intervention allowed us to describe the multi-faceted experiential process of learning mindfulness. It was found that 4 to 6 months were required to embed a basic skill set.

MBSR is presented in the literature as a psycho-educational program that can reduce suffering. This study has shown that it can indeed bring considerable therapeutic improvement but that it is not a straightforward option for people living with long-term conditions. It is our judgment that considerable commitment and courage were needed to engage with what has been revealed as a multifaceted learning process.

Distinct differences were apparent at the individual and group level as participants moved from the more intensive and directive introductory course to the fortnightly meetings, progressed through the supported transition phase, and finally embraced self-facilitation. Half of those who completed the year-long intervention (n = 5) reported improvements in their physical and psychological health and well-being, while the remainder (n = 5) described it as a useful stress management tool.

Intentionality and Embodiment

Two core streams of experience were identified: embodied, integrated mindfulness; and mindfulness as a stress management tool. This key finding points up the importance of attending to how individual participants construe what mindfulness entails. Rather than viewing mindfulness as a psycho-educational intervention delivered to participants, the study has highlighted how participants themselves actively shaped their own mindfulness projects, locating them within the wider horizons of their lives. The fact that they could pursue contrasting visions of mindfulness can also be seen to reflect the current polysemous meaning of mindfulness that we have noted earlier.

How one interprets and responds to this difference in intentionality remains open to question. We have observed that Kabat-Zinn’s conceptualization of mindfulness entails the kind of ontological orientation to experience that those participants who adopted “embodied, integrated” mindfulness displayed. Accordingly, it could be argued that one should make greater efforts to assist those who were treating it as a stress management tool to achieve this ontological disturbance and reorientation; and there is a good general case for a deeper exploration of mindfulness psychology featuring in mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) to guide the understanding of core material. At the same time, however, it could be argued that those who were treating it as a stress management tool were gaining from their practice, albeit not to the same degree, and that their autonomy to set their own mindfulness project should be respected.

Embodiment and Challenges

Turning to consider how the processes of embodiment were experienced by participants, embodied awareness proved to be an elusive skill that was difficult to attain without individualized support, especially for men in this program. Recent work indicates that positive emotional change through mindfulness is linked to the ability to describe emotions, and suggests that women may be more receptive than men to mindfulness training, pointing to the benefits of gender-specific modifications (Rojiani et al., 2017). It needs to be noted, however, that female as well as male participants in this study struggled with the invitation to embrace difficulty with acceptance and kindness. While exposure to difficult experience and accepting vulnerability have been identified as critical change mechanisms in MBIs (Malpass et al., 2012), it was shown here that this form of encounter could be very disturbing, giving rise to fear, confusion, and strong resistance. Bringing awareness to experience can precipitate unpleasant symptoms, and in beginners to mindfulness present-centered attention may not be associated with a nonjudgmental approach to self (Baer, 2006).

Media accounts accent the benefits of mindfulness practice, but there is much less coverage of its potential for harm. This gap requires attention (Fjorback et al., 2011), particularly given that meditation can invoke psychological disturbance in some people (Shonin et al., 2014). Safety issues were given close attention within the current intervention and alertness to adverse psychological or physical effects seen as a central component of exercising an ethics of care. We suggest that safety issues during mindfulness interventions require further consideration and underline a moral responsibility to support participant learning robustly, even where participants are not viewed as constituting a “vulnerable” group.

Features of the Intervention

Heterogeneity of conditions

Turning to look at salient features of the intervention, a central decision was to recruit participants who had a wide range of long-standing conditions. This decision proved to be justified, as participants found benefits in the diversity of conditions represented in the group; and, as has been illustrated, felt that this diversity obviated unhelpful comparisons and a pressure to achieve. While the trend within health contexts has been to offer mindfulness by diagnostic category, it appears that diversity in participants’ conditions can promote a broader view of mindfulness and help to generalize its acceptability within the public health domain (Horrigan, 2007). It also needs to be noted that multimorbidity is common in people living with enduring illness and often physical and psychological impacts co-exist (Barnett et al., 2012).

Group dynamics and discourse

Group resonance is posited as an important part of mindfulness experience (Shapiro et al., 2006), but there is little empirical research on whether, and how, this is achieved. Studies that have investigated group processes in MBIs have tended to present a largely positive picture of group interactions and their effects (Cormack et al., 2018). This study has presented a more variegated picture, bringing out the strong influence of group dynamics which both helped and impeded members’ experience and varied over time. The role of the facilitator as a mediating force was critical in responding to difficulties experienced by individuals and in ensuring that certain individuals did not dominate group discussion. Acting in a way that was considerate of others posed considerable challenge in a group of people where extensive suffering was a common thread. Group members struggled with some aspects of mindfulness education and benefit from group sharing was variable, pointing up a need for 1:1 contact to help address issues at an individual level.

While some participants took quite readily to the forms of language and norms and processes of communication, for others the ways of speaking, interacting, and enacting an identity within MBSR did not resonate with their preceding capital “D” Discourses (Gee, 2008), in some cases sparking a degree of resistance. This finding suggest that there is a need to give close attention in future research to how the discourse of mindfulness is perceived and reacted to in particular sociocultural contexts.

Attrition

There was a very high level of attendance throughout the initial 9-week course; thereafter, attrition was gradual but very considerable by the end of the program. This finding can be evaluated in different ways. A cursory judgment could be made that this is simply a mark of failure. Alternatively, it could be seen as a positive outcome that half of the participants despite suffering from chronic pain and long-standing conditions stayed the course. One cannot readily predict what the attrition rate might be for longer-term interventions held in different contexts and geared to different groups of participants; but clearly a longer intervention will always carry the risk of a considerable drop out. Even allowing for the concomitant danger of considerable drop out, a strong case can be made for taking ahead longer-term interventions, as we argue in the following, final paragraphs.

The case for longer-term interventions

The design of mindfulness interventions would seem to require a balance to be struck between providing sufficient professional input and fostering participants’ independent practice. One means of achieving both of these objectives is to build in a gradual and supported transition toward self-management. The expanded community-based program and hands-on guiding approach in this study helped to empower participants and to embed and embody learning, but this approach took time. Participant motivation toward mindfulness was strong at the outset coupled with the desire for increased self-regulation of illness symptoms. In the event, the pursuit of mindfulness could not always be readily woven into the fabric of participants’ situated lived experience. The exacerbation of illness, family stressors and other life events impeded mental focus and the provision of time to build skills and confidence was key to being able to deploy mindfulness when under duress.

Participant experience here showed that 4 to 6 months are needed to build a foundational practice, suggesting that short-form mindfulness courses may not allow sufficient time for skill acquisition, at least for participants whose health is severely compromised. It is contended that participant understanding of, and skill-development in, mindfulness can be significantly expanded through increasing the experiential learning component to incorporate self-guiding, a strategy that led to improvements in well-being in this group.

The findings reviewed in the preceding paragraphs are in line with the results of a number of preceding studies. Longitudinal follow-up of MBSR courses has shown a gradual decline in effects (e.g., Henderson et al., 2012) and those that demonstrate greater durability appear to include additional contact (e.g., Gross et al., 2011). The degree of exposure to mindfulness instruction and amount of home practice have been positively linked to the improvement of clinical symptoms (Carmody & Baer, 2009; Parsons et al., 2017); and the value of longer interventions for vulnerable populations noted (Koszycki et al., 2007; Mackenzie et al., 2007).

In conclusion, the argument for a long-term intervention is distinctly strengthened when one casts a close, analytical eye on what “learning” mindfulness actually entails. Here, it is useful to distinguish between acquisition and learning (Gee, 2008; Pinker, 1994). Entering the practices of mindfulness involves both learning and acquisition where “learning is a process that involves conscious knowledge gained thorough teaching . . . or through certain life experiences that trigger conscious reflection” (Gee, 2008, p. 170). By contrast “acquisition is a process of acquiring something (usually, subconsciously) by exposure to models, a process of trial and error, and practice within social groups, without formal teaching” (Gee, 2008, p. 169). It seems reasonable to suggest that, as in the mastery of any demanding skill set, the acquisition of mindfulness practices and their associated intentions, attitudes, and ways of being, is not a rapid exercise but one that calls for a considerable period of assimilation, fine-tuning, and consolidation.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend a heartfelt appreciation to all the participants in this research study who provided an abundance of rich data, and numerous valuable insights into their mindfulness experience. They also express their gratitude to the Queen’s Nursing Institute for Scotland (QNIS) who provided funding to support the mindfulness intervention.

Author Biographies

Gillian Mathews has a professional background in nursing, midwifery and health visiting. She works as a health researcher, psychotherapeutic counsellor and mindfulness facilitator. Her research is centred on the needs of people with long-term health conditions, including people living with dementia and their families/carers.

Charles Anderson is a long-standing practitioner of mindfulness and facilitates mindfulness groups. His research is focused on learning and teaching, centred principally on language and on interaction in a range of educational settings.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Gillian Mathews  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0595-8475

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0595-8475

References

- Ashworth A., Ashworth P. (2003). The lifeworld as phenomenon and as research heuristic exemplified by a study of the lifeworld of a person suffering Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 34(2), 179–205. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth P. (2003). An approach to phenomenological psychology: The contingencies of the lifeworld. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 34(2), 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Baer R. A. (2006). Mindfulness-based treatment approaches: clinician’s guide to evidence base and applications. Elsevier & Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett K., Mercer S. W., Norbury M., Watt G., Wyke S., Guthrie B. (2012). Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet, 380(9836), 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop S. R., Lau M., Shapiro S., Carlson L., Anderson N. D., Carmody J., Segal Z. V., Abbey S., Speca M., Velting D., Devins G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmeijer E., Prenger R., Taal E., Cuijpers P. (2010). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on mental health of adults with a chronic medical disease: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 68(6), 539–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce A., Davies B. (2005). Mindfulness in hospice care: Practicing meditation-in-action. Qualitative Health Research, 15(10), 1329–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody J., Baer R. A. (2009). How long does a mindfulness-based stress reduction program need to be? A review of class contact hours and effect sizes for psychological distress. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(6), 627–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherkin D. C., Anderson M. L., Sherman K. J., Balderson B. H., Cook A. J., Hansen K. E., Turner J. A. (2017). Two-Year Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or Usual Care for Chronic Low Back Pain. JAMA, 317(6), 642–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A., Serretti A. (2010). A systematic review of neurobiological and clinical features of mindfulness meditations. Psychological Medicine, 40(8), 1239–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormack D., Jones F. W., Maltby M. (2018). A “collective effort to make yourself feel better”: The group process in mindfulness-based interventions. Qualitative Health Research, 28(1), 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran N. J. (2014). Experiencing wellness within illness: Exploring a mindfulness-based approach to chronic back pain. Qualitative Health Research, 24(6), 749–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus G. (2011). Is mindfulness present-centred and non-judgmental? A discussion of the cognitive dimensions of mindfulness. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay L. (2011). Phenomenology for therapists: Researching the lived world. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay L. (2012). Unfolding the phenomenological research process: Iterative stages of “seeing afresh.” Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 53(2), 172–201. [Google Scholar]

- Fjorback L. O., Arendt M., Ørnbøl E., Fink P., Walach H. (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness—based cognitive therapy—A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124(2), 102–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee J. P. (2008). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gendlin E. (1996). Focusing-oriented psychotherapy: A manual of the experiential method. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi A. (1985). Sketch of a psychological phenomenological method. In Giorgi A. (Ed.), Phenomenology and psychological research (pp. 8–22). Duquesne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi A. (1997). The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 28, 235–260. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman D., Davidson R. (2017). The science of meditation: How to change your brain, mind and body. Penguin Life. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal M., Singh S., Sibinga E. M., Gould N. F., Rowland-Seymour A., Sharma R., Berger Z., Sleicher D., Maron D. D., Shibab H. M., Ranasinghe P. D., Linn S., Saha S., Bass E. B., Haythornthwaite J. A. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 357–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross C. R., Kreitzer M. J., Reilly-Spong M., Wall M., Winbush N. Y., Patterson R., Mahowald M., Cramer-Bklj M. (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction versus pharmacotherapy for chronic primary insomnia: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Explore, 7(2), 76–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P., Niemann L., Schmidt S., Walach H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. C., Wilson K. G. (2003). Mindfulness: Method and process. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson V. P., Clemow L., Massion A. O., Hurley T. G., Druker S., Hébert J. R. (2012). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on psychosocial outcomes and quality of life in early-stage breast cancer patients: A randomized trial. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 131, 99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann S. G., Oh D., Sawyer A. T., Witt A. A. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrigan B. (2007). Interview with Saki Santorelli EdD, MA. Mindfulness and medicine. Explore, 3(2), 136–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns S. A., Von Ah D., Brown L. F., Beck-Coon K., Talib T. L., Alyea J. M., Monahan P. O., Tong Y., Wilhelm L., Giesler R. B. (2016). Randomized controlled pilot trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction for breast and colorectal cancer survivors: Effects on cancer-related cognitive impairment. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 10(3), 437–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. (2013). Full catastrophe living, revised edition: How to cope with stress, pain and illness using mindfulness meditation. Little, Brown Book Group. [Google Scholar]

- Koszycki D., Benger M., Shlik J., Bradwejn J. (2007). Randomized trial of a meditation-based stress reduction program and cognitive behavior therapy in generalized social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 2518–2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma D., Kumano H. (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cancer: A meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer, 18(6), 571–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie M. J., Carlson L. E., Munoz M., Speca M. (2007). A qualitative study of self-perceived effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in a psychosocial oncology setting. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 23(1), 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Malpass A., Carel H., Ridd M., Shaw A., Kessler D., Sharp D., Bowden M., Wallond J. (2012). Transforming the perceptual situation: A meta-ethnography of qualitative work reporting patients’ experiences of mindfulness-based approaches. Mindfulness, 3, 60–75. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty M. (1962. [1945]). Phenomenology of perception (Smith C., Trans). Routledge and Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. (2008). The code: Standards of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives. http://www.nmc-uk.org/Publications/Standards/The-code/Introduction/

- Parsons C. E., Crane C., Parsons L. J., Fjorback L. O., Kuyken W. (2017). Home practice in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of participants’ mindfulness practice and its association with outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 95, 29–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinker S. (1994). The language instinct: How the mind creates language. William Morrow. [Google Scholar]

- Rojiani R., Santoyo J. F., Rahrig H., Roth H. D., Britton W. B. (2017). Women benefit more than men in response to college-based meditation training. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro S. L., Carlson L. E., Astin J. A., Freedman B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 373–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonin E., van Gordon W., Griffiths M. (2014). Are there risks associated with using mindfulness in the treatment of psychopathology? Clinical Practice, 11(4), 389–392. [Google Scholar]

- Stelter R. (2010). Experience-based, body-anchored qualitative research interviewing. Qualitative Health Research, 20(6), 859–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronto J. C. (1993). Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- United Kingdom Network of Mindfulness Teacher Training Organisations. (2015). Good practice guidance for teachers. Microsoft Word - UK MB teacher GPG 2015 final 2.doc (bamba.org.uk). [Google Scholar]

- Vøellestad J., Sivertsen B., Nielsen G. H. (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for patients with anxiety disorders: Evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(4), 281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meide H., Teunissen T., Collard P., VisseM Visser L. H. (2018). The mindful body: A phenomenology of the body with multiple sclerosis. Qualitative Health Research, 28(14), 2239–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Velden A. M., Kuyken W., Wattar U., Crane C., Pallesen K. J., Dahlgaard J., Fjorback L. O., Piet J. (2015). A systematic review of mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in the treatment of recurrent major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 26–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wijngaarden E., van der Meide H., Dahlberg K. (2017). Researching health care as a meaningful practice: Toward a nondualistic view of evidence for qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 27(10), 1738–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein L. (1958). Philosophical investigations. Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]