COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection has caused substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide and paralyzed the international economy. Understanding the magnitude and duration of the antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 is important to achieve a balance between curbing the pandemic and minimizing adverse effects on society.1 Although the antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 within 9 months has been extensively studied,2–6 little is known about the magnitude and kinetics of antibody responses for over 9 months. Moreover, with limited observations over 9 months (n < 100),2,7,8 several studies have produced inconsistent conclusions about antibody dynamics, suggesting different rates of antiviral antibody positivity at the last follow-up.2,7,8 These studies have been limited by a lack of measurement of neutralizing antibodies (NAbs),7 of inclusion of mild or asymptomatic cases,2,8 and of further exploration of potential predisposing factors for antibody dynamics.2,7 Considering the individual heterogeneity (such as disease severity)8 and time-dependent nature1 of the immune response, in-depth characterization of SARS-CoV-2 antibody kinetics across disease severity groups over a long period is urgently needed. Therefore, we repeatedly tested IgM, IgG, viral spike protein receptor-binding dom (anti-RBD) IgG, and NAb titers in COVID-19 patients during a follow-up period of up to 10 months and explored potential predisposing factors of antibody titers during follow-up.

A total of 215 COVID-19 patients consisting of both mild and severe cases were recruited and regularly followed up. During a median follow-up of 275 (range, 241–303) days, 803 serum samples were collected for longitudinal SARS-CoV-2 serological tests. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were performed to measure IgM, IgG, and anti-RBD IgG. NAbs were evaluated using a SARS-CoV-2 pseudotyped virus neutralization assay. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (NT50) for plasma was calculated as the NAb titer. Samples from the same patient were tested together and in double-blind randomization. Details of the study design and antibody test are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Of the 215 patients, the median (interquartile range, IQR) age was 61 (51–67) years, and 105 (48.8%) individuals were male (Table S1). Their symptoms were classified as mild (142 participants, 66.0%) or severe (73 participants, 34.0%) according to Chinese national treatment guidelines. A total of 112 (52.1%) patients had a long duration of viral clearance (≥34 days), and 38 patients (17.7%) had redetectable positive RNA tests. Hypertension (78, 36.3%), diabetes (30, 14.0%), and cardiovascular disease (17, 7.9%) were the most common comorbidities. The median (IQR) duration between symptom onset and the first antibody test was 37 (23–100) days. Most participants (116, 54.0%) underwent four antibody tests. Details of the definition of severity, duration of viral clearance, redetectable positive RNA test, and comorbidities are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

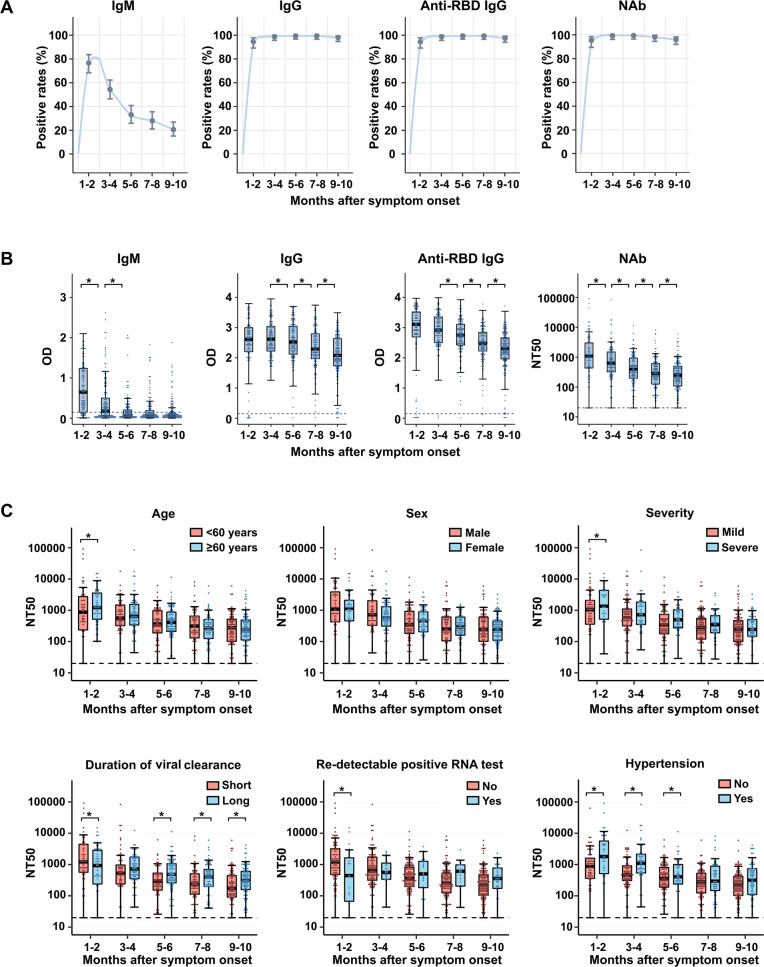

The positivity rates for IgM, IgG, anti-RBD IgG, and NAb fell to 20.4% (39/191), 97.9% (187/191), 97.4% (186/191), and 95.8% (183/191), respectively, during 9–10 months post symptom onset (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 1B and Fig. S1, a rapid decline in IgM titers was observed from 1 to 6 months post symptom onset, with median (IQR) optical density (OD) values at 1–2, 3–4, and 5–6 months post symptom onset of 0.65 (0.15–1.24), 0.18 (0.05–0.51), and 0.06 (0.02–0.21), respectively. Afterwards, IgM titers remained relatively stable for 6–10 months. In addition, progressive declines in IgG and anti-RBD IgG were observed during 1–10 months after symptom onset, with median OD (IQR) values from 2.61 (2.20–3.00) and 3.11 (2.69–3.51) at 1–2 months to 2.08 (1.74–2.64) and 2.29 (1.95–2.67) at 9–10 months post symptom onset. Similarly, a significant decrease in NAbs was identified during the whole observation period. The median (IQR) NT50 was 1096 (430–3222) during 1–2 and decreased to 249 (105–501) during months 9–10.

Fig. 1.

Longitudinal assessment of the antibody response to SARS-CoV-2. A Positivity rates for virus-specific IgM, IgG, anti-RBD IgG, and NAb. An optical density (OD) value of 0.15 indicated positivity for IgM, IgG, and anti-RBD IgG; the cutoff for NAb was NT50 of 20. B Box plots show the distribution of IgM, IgG, anti-RBD IgG, and NAb titers over time. Boxplots show the 25th, 50th (median), and 75th percentiles. Whiskers extend to the upper and lower adjacent values, with the farthest values within 1.5 × the interquartile range beyond the 25th and 75th percentiles. The dashed lines of IgM, IgG, and anti-RBD IgG indicate the thresholds for a test to be declared positive. The dashed lines of neutralizing antibodies indicate the limit of detection for the pseudotyped virus neutralization assay. We used linear mixed models to estimate the difference between different phases after symptom onset, which was adjusted for age and sex. All P values were calculated based on multivariate linear mixed models. C Box plots illustrate the distribution of NAb titers by age, sex, severity, duration of viral clearance, redetectable positive RNA test, and history of hypertension, along with the median (solid horizontal line in the box) and quartile (upper/lower limits of the box). We used linear mixed models and constructed Wald tests to derive P values comparing different subgroups, which were adjusted for age and sex. NAb neutralizing antibody, OD optic density, NT50 half-maximal inhibitory concentration for plasma. *P value < 0.05

To explore potential predisposing factors of antibody dynamics during each postinfection phase, we examined distributions of NAb by age, sex, disease severity, duration of viral clearance, redetectable positive RNA test, and hypertension, as depicted in Fig. 1C. NAb titers during 1–2 months post symptom onset were significantly higher in elderly participants, severe cases, and patients without repositive RNA tests or with hypertension. Compared to the group with a long viral clearance duration, the group with a short viral clearance duration had a higher NAb titer during 1–2 months and a lower titer during 5–10 months post symptom onset. Longitudinal assessment of IgM, IgG, and anti-RBD IgG titers by different characteristics is shown in Figs. S2–S4. Figures S5–S8 also illustrate associations of baseline characteristics with the trajectory patterns of IgM, IgG, anti-RBD IgG and NAb titers.

Consistent with previous studies,3–5,7 declines in antibody titers of IgG, anti-RBD IgG, and NAb were observed in the present study. Moreover, we found the NAb seropositive rate during the 10 months post onset to be 95.8%, which was much higher than that in another study conducted by He et al.2 in Wuhan with 9 months of observation (46.0%). One plausible explanation for the difference is that the intensity and duration of humoral immune responses might be inherently heterogeneous for patients with different degrees of severity.8 He’s study2 mainly enrolled asymptomatic cases (>75%), whereas our study included mild and severe cases. Evidence suggests weaker immune responses in asymptomatic and mild cases than in cases with more severe symptoms.9 Notably, we found that participants with long viral clearance durations had lower NAb titers for 1–2 months but higher NAb titers for 5–10 months than those with short viral clearance durations. Strong antibody response in the early period may help to block virus entry and facilitate viral clearance; a long viral clearance duration may contribute to a persistently strong antibody response in the late convalescence phase. Furthermore, we observed that pre-existing hypertension was linked to higher NAb titers during 1–6 months of convalescence. Hypertension is one of the most common comorbidities of COVID-19 patients and is linked to increased mortality and morbidity in the pandemic.10 Our findings provide a clue regarding a link between hypertension and the immune response in COVID-19.

Our study depicts the comprehensive dynamics of the four most relevant antibodies for SARS-CoV-2 for up to 10 months in 215 participants consisting of patients with both mild and severe disease. To our knowledge, this is one of the longest observations for SARS-CoV-2 antibody dynamics thus far. Moreover, our study had a high follow-up rate, with 88.8% (191/215) attending the last follow-up during 9–10 months post symptom onset. Our findings may have important implications for future epidemic control and vaccination strategies.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank all the study participants and project staff. This work was supported by grants from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2019kfyXMBZ015), the 111 Project (Prof. Wu), the Fellowship of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020T130034ZX, and 2020T130035ZX), the National Key Research and Development Plan Program of China (2020YFC0860800), the Revitalization Projects after the COVID-19 Plague of the China Association for Science and Technology (20200608CG111311) and the Emergency Research Projects for COVID-19 Prevention and Control of the Wuhan Health Commission (EG20M01).

Author contributions

H.W., Y.Y., M.X., L.C., and Y.Z. are joint first authors. T.W., X.L., R.G., H.W., Y.Y., M.X., and Y.Z. designed the study. All authors participated in the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data. H.W., Y.Y., L.C., H.Z., Y.L., and T.D. performed the laboratory work including the data analysis. Y.Y., H.W., L.C., and P.L. drafted the manuscript. H.W., Y.Y., L.C., Y.Z., A.P., C.W., L.L., R.G., and T.W. contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. T.W., X.L., and R.G. are joint senior authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Hao Wang, Yu Yuan, Mingzhong Xiao, Li Chen, Youyun Zhao.

Contributor Information

Rui Gong, Email: gongr@wh.iov.cn.

Xiaodong Li, Email: lixiaodong555@126.com.

Tangchun Wu, Email: wut@mails.tjmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41423-021-00708-6.

References

- 1.Wu T. Persistence of humoral and cellular immune response after SARS-CoV-2 infection: opportunities and challenges. Front. Med. 2020;14:816–819. doi: 10.1007/s11684-020-0823-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He Z, et al. Seroprevalence and humoral immune durability of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in Wuhan, China: a longitudinal, population-level, cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2021;397:1075–1084. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00238-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dan JM, et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science. 2021;371:eabf4063. doi: 10.1126/science.abf4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaebler, C. et al. Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nature10.1038/s41586-021-03207-w (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Peng P, et al. Changes in the humoral immunity response in SARS-CoV-2 convalescent patients over 8 months. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2021;18:490–491. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-00605-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitcombe AL, et al. Comprehensive analysis of SARS-CoV-2 antibody dynamics in New Zealand. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2021;10:e1261. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Favresse J, et al. Persistence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies depends on the analytical kit: a report for up to 10 months after infection. Microorganisms. 2021;9:556. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9030556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanshylla, K. et al. Kinetics and correlates of the neutralizing antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Cell Host Microbe 29, 1–13 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Long QX, et al. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1200–1204. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0965-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel AB, Verma A. COVID-19 and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: what is the evidence? JAMA. 2020;323:1769–1770. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.