Abstract

Objectives: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has presented extreme challenges for health care workers. This study sought to characterize challenges faced by physician mothers, compare differences in challenges by home and work characteristics, and elicit specific needs and potential solutions.

Methods: We conducted a mixed-methods online survey of the Physician Moms Group (PMG) and PMG COVID19 Subgroup on Facebook from April 18th to 29th, 2020. We collected structured data on personal and professional characteristics and qualitative data on home and work concerns. We analyzed qualitative data thematically and used bivariate analyses to evaluate variation in themes by frontline status and children's ages.

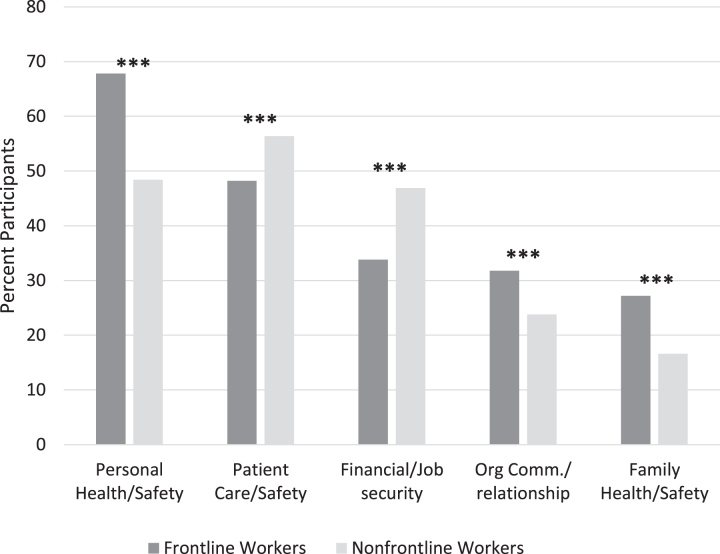

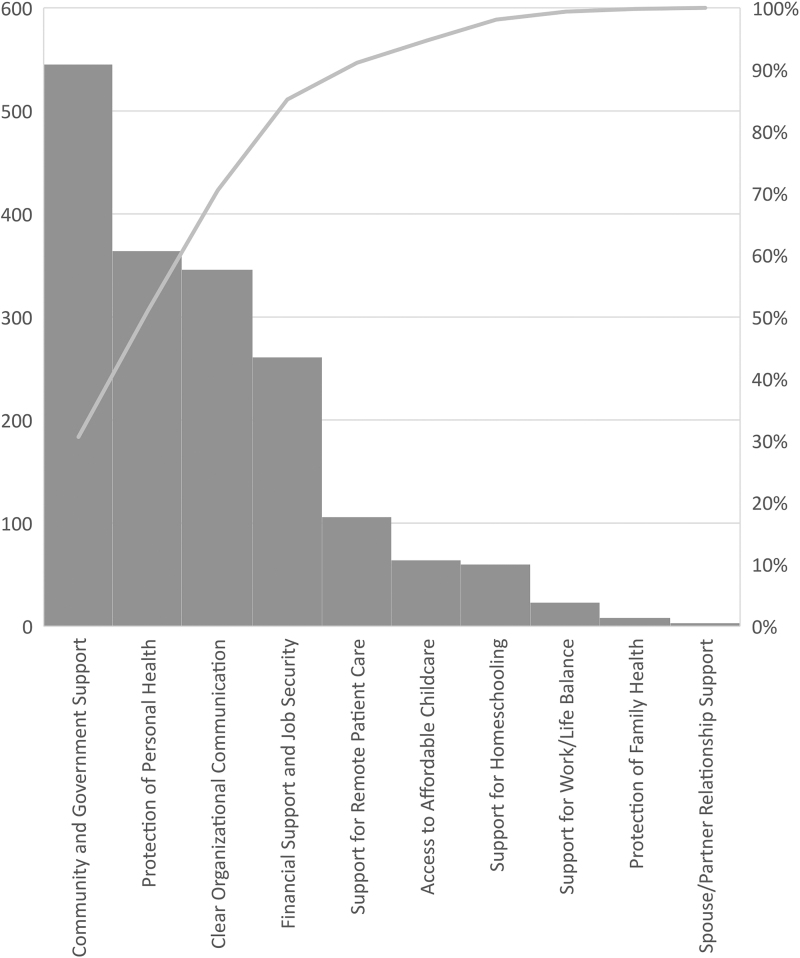

Results: We included 1,806 participants in analysis and identified 10 key themes. The most frequently identified need/solution was for Community and Government Support (n = 545, 47.1%). When comparing frontline and nonfrontline physicians, those on the frontline more frequently raised concerns about Personal Health and Safety (67.8% vs. 48.4%, p < 0.001), Organizational Communication and Relationships (31.8% vs. 23.8%, p < 0.001), and Family Health and Safety (27.2 vs. 16.6, p < 0.001), while nonfrontline physicians more frequently addressed Patient Care and Safety (56.4% vs. 48.2%, p < 0.001) and Financial/Job Security (33.8% vs. 46.9%, p < 0.001). Participants with an elementary school-aged child more frequently raised concerns about Parenting/Homeschooling (44.0% vs. 31.1%, p < 0.001) and Work/Life Balance (28.4 vs. 13.7, p < 0.001), and participants with a preschool-aged child more frequently addressed Access to Childcare (24.0 vs. 7.7, p < 0.001) and Spouse/Partner Relationships (15.8 vs. 9.5, p < 0.001), when compared to those without children in these age groups.

Conclusions: The physician workforce is not homogenous. Health care and government leaders need to understand these diverse challenges in order to meet physicians' professional and family needs during the pandemic.

Keywords: physicians, women, mothers, COVID-19, work-life balance, occupational stress

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has presented extreme challenges for health care workers. Lack of access to proper personal protective equipment (PPE), fear of becoming infected, fear of infecting friends and family, lack of testing, lack of access to childcare during school closures, and lack of up-to-date information about COVID-19 have led to higher levels of depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia among health care providers around the world.1–5 Female health care workers are disproportionately affected by many of these challenges.1,6

The pandemic's impact on health care providers varies based on professional attributes (e.g., clinical duties, specialty, and career/training level, as well as personal characteristics such as age, gender, and marital status.1,4,7–9 Female physicians, and mothers in particular, face additional challenges because of underlying structural inequalities based on gender, including lower pay than their male counterparts,10 discrimination in the workplace,11 and the expectation that they will take on a greater share of childcare and household duties, particularly in two-parent heterosexual households.12 Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, parents in the United States have almost doubled their time spent on household tasks and childcare, with mothers contributing an average of 15 hours per week more than fathers.13 There is evidence that these additional hours spent on household tasks and childcare are negatively impacting women's productivity at work more so than men. Research in academic settings, including academic medical settings, has found that the percentage of research articles submitted by male authors has actually increased in regions where social-distancing measures (such as school closures) were adopted, while articles submitted by women have decreased.14,15

In this mixed-methods study sampling a large, diverse online group of U.S. physician mothers, we sought to characterize specific challenges faced by the female physician workforce relating to work and home life during the COVID-19 pandemic and to compare differences in these challenges based on home and work characteristics. We also aimed to elicit specific solutions to improve the COVID-19 response and lessen the impact on the personal and professional lives of these physician mothers.

Methods

Study setting and population

We developed an online survey to collect data on mental health, demographics, concerns, and needs of physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. We posted the survey daily from April 18th to April 29th, 2020, on two online groups: Physician Moms Group (PMG) and PMG COVID19 Subgroup. We selected the groups due to their large size, high level of participant engagement, group guidelines requiring all members to be both physicians and mothers (including pregnant women), and history of successful research collaborations.9,16–20 The PMG has 73,369 physician members who self-identify as mothers, including pregnant, adoptive, or foster mothers.21 The group is active with an average of 205 new posts, 6,400 comments, and 22,000 reactions and “likes” daily. The PMG COVID19 Subgroup was created as a linked group to PMG on March 6, 2020, to address COVID-19 effects on the physician community and serve as an educational platform to share current clinical information, research, and hands-on experience of caring for patients with the disease.22 The PMG COVID19 Subgroup includes 37,174 members, 91.5% of whom are women. The majority (95%) of members of both PMG and the PMG COVID19 Subgroup live in the United States. The PMG COVID19 Subgroup is also active with an average of 200 posts, 6,500 comments, and 18,000 reactions or “likes” daily.

Study design and measurements

We iteratively developed a 22-item questionnaire-based survey with both open- and closed-ended questions, focusing on physician mothers' work and home lives during the COVID-19 pandemic. The tool was developed after a literature review and with expert feedback from physicians and academic researchers with diverse specialties and backgrounds.1–5

Participants reported demographics, family composition, marital status, specialty, and clinical practice information (e.g., inpatient, outpatient, telehealth) during the previous 14 days. Participants reported whether they had cared for a patient with presumed or confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in person within the last 14 days. We categorized those who responded “yes” as frontline workers. For both current and prepandemic periods, we asked participants to approximate the time spent on caregiving and domestic tasks (defined as tending to loved ones' physical and psychological needs; home-related responsibilities) by self, partner/spouse, or others (inclusive of employed help, relatives, or others). Participants also responded to three open-ended questions: (1) What are the biggest challenges you are facing at work right now? (2) What are the biggest challenges you are facing at home right now? and (3) What are some specific ways your employer or the general public can help you right now? (see Supplementary Appendix SA1 for full instrument).

This study was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board.

Analytic plan

We used the mixed-method analytic software Dedoose23 to code responses to the open-ended survey questions. Using a thematic content analysis approach,24,25 five team members (M.C.H., K.S.M., L.C.D., Ele.L., U.S.) reviewed the data and developed a draft codebook based on patterns that the team determined to be dominant in the data. We then conducted multiple rounds of codebook revision and interrater reliability testing until a minimum pooled Cohen's kappa (κ) value of greater than κ = 0.8 was achieved by all coders to ensure the clarity of coding definitions.26 Four team members (M.C.H., K.S.M., K.O., E.G.M.) then applied the codebook to the full dataset, conducting interim interrater reliability checks to ensure that κ ≥ 0.8 was maintained throughout.27 In total, we double coded 15% of the full data set with an average of κ = 0.82. We applied multiple themes to a single participant answer if applicable.

We calculated frequencies for each of the 10 main codes by question and for the full sample, and we identified sample quotes illustrating the range of dimensions within each theme. To evaluate variation in themes by frontline worker role and children's ages, we conducted chi-square, Fisher-exact test, t-testing, and Mann–Whitney-U testing as appropriate for participants' work and family characteristics using IBM SPSS 24.28

Reflexivity statement

The authors include a diverse group of health researchers from a wide range of professional backgrounds, including medical anthropology, bioethics, public policy, public health, epidemiology, critical care medicine, dermatology, psychiatry, emergency medicine, internal medicine, and radiation oncology, among others. Ten of the 12 authors are mothers, and 8 of us are physician mothers, although the ages of our children vary widely. We also experienced widely different personal impacts of the pandemic, with some working on the frontlines treating COVID-19 patients and others working primarily from home through various means. As such, our personal and professional backgrounds also reflect the diverse work and home challenges captured in this study. In addition, the study team includes academic leaders who mentor many physician mothers and who are seeking institutional solutions to these issues.

Results

Participant characteristics and caregiving responsibilities

A total of 2,268 individuals clicked on the survey link reaching the consent form, and 1,814 of these individuals proceeded to answer the first binary question about whether they were frontline workers. We excluded 8 participants who identified as male from the analysis, leaving a total sample size of 1,806. Overall, 56.8% identified as white, with a mean age of 42.6 ± 6.4 years, and a median of 2 children (interquartile range 2–3) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics among Frontline Workers, Nonfrontline Workers, and Overall Sample

| FL (n = 771), n (%) | NFL (n = 1,035), n (%) | Overall (N = 1,806), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 423 (54.9) | 603 (58.3) | 1,026 (56.8) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 25 (3.2) | 31 (3.0) | 56 (3.1) |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 142 (18.4) | 151 (14.6) | 293 (16.2) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 67 (8.7) | 86 (8.3) | 153 (8.5) |

| Other, non-Hispanic or unknown | 21 (14.8) | 22 (15.8) | 43 (15.4) |

| Age (mean ± SD)a | 42.4 ± 6.0 | 42.7 ± 6.7 | 42.6 ± 6.4 |

| Number of children (median, IQR)b | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) |

| Age of childrenb | |||

| Preschool (<6 years)* | 331 (42.9) | 496 (47.9) | 827 (45.8) |

| Elementary age (6–10 years)* | 345 (44.7) | 404 (39.0) | 749 (41.5) |

| Middle/high school age (11–18 years) | 237 (30.7) | 279 (27.0) | 516 (28.6) |

| Adult children (19+ years) | 65 (8.4) | 100 (9.7) | 165 (9.1) |

| Pregnancy/no children* | 21 (2.7) | 14 (1.4) | 35 (1.9) |

| Missing | 81 (10.5) | 121 (11.7) | 202 (11.2) |

| Employed** | |||

| Full-time | 593 (76.9) | 687 (66.4) | 1,280 (70.9) |

| Part-time | 90 (11.7) | 197 (19.0) | 287 (15.9) |

| Unemployed | 5 (0.6) | 17 (1.6) | 22 (1.2) |

| Prefer not to answer or missing | 83 (10.8) | 134 (12.9) | 217 (12.0) |

| Clinical practice typec | |||

| Inpatient, in-person (hospital)** | 507 (65.8) | 303 (29.3) | 810 (44.9) |

| Outpatient, in-person (clinic) | 400 (51.9) | 564 (51.9) | 964 (53.4) |

| Inpatient, via telehealth | 49 (6.4) | 74 (7.4) | 123 (6.8) |

| Outpatient, via telehealth** | 376 (48.8) | 667 (64.4) | 1,043 (57.8) |

| No direct patient care** | 3 (0.4) | 142 (13.7) | 145 (8.0) |

Significant differences between groups: p < 0.05.

Significant differences between groups: p < 0.001.

Calculated from 1,762 participant responses; Missing: n = 44.

Calculated from 1,604 participant responses; Missing: n = 202.

Clinical practice setting in the last 2 weeks; categories not mutually exclusive.

FL, frontline worker; IQR, interquartile range; NFL, nonfrontline worker; SD, standard deviation.

Three-quarters of the participants reported working in-person within either inpatient or outpatient settings (n = 1,403), with 20.3% working in both. Sixty percent of all participants (n = 1,089) reported having telehealth responsibilities for either inpatient or outpatient settings. Almost half the participants were frontline workers (n = 771, 42.7%). Frontline workers more often worked and in inpatient settings when compared to nonfrontline providers. The age of participants' children varied widely, with 45.8% reporting having at least one preschool-aged child, 41.5% at least one elementary school-aged child, 28.6% a middle or high school-aged child, and 9.1% at least one adult child (Table 1). Frontline workers completing the survey also had significantly younger children, compared to nonfrontline workers.

When reporting distribution of caregiving responsibilities, there was a wide range in the distribution of estimated percentage effort for themselves, their partners, and external caregivers (Supplementary Appendix Table ST1). On average, participants reported a decrease in the support provided by employed caregivers, relatives, or others with the current pandemic. For nonfrontline physicians, this corresponded to an increase in their percent effort for overall caregiving/domestic responsibilities twice that seen for their spouse/partner (mean increase 5.3% ± 16.9 vs. 2.6% ± 13.3). For frontline providers, on the other hand, the increase in percent effort for overall caregiving responsibility for the participant was, on average, small (0.9% ± 16.9) compared to the increase in the reported effort of their spouse (5.2% ± 14.3).

Qualitative themes

Of the 1,806 survey participants, 1,702 (94.2%) responded to at least one qualitative question with a total of 4,465 qualitative responses. These included 1,634 (90.5%) responses regarding work challenges, 1,674 (92.7%) responses regarding home challenges, and 1,157 (64.1%) responses regarding needs and solutions. The 10 main themes identified across all questions included the following: (1) Personal Health and Safety (n = 1,324, 30.2%); (2) Patient Care and Safety (n = 982, 22.4%); (3) Financial and Job Security (n = 910, 20.8%); (4) Parenting/Homeschooling (n = 676, 15.4%); (5) Community and Government Support (n = 564, 12.9%); (6) Organizational Communication and Relationships (n = 537, 12.3%); (7) Family Health and Safety (n = 374, 8.5%); (8) Work/Life Balance (n = 363, 8.3%); (9) Access to Childcare (n = 318, 7.2%); and (10) Spouse/Partner Relationships (n = 222, 5.1%). Theme definitions, illustrative quotes, and associated frequencies are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of 10 Primary Themes with Frequency Across All Three Questions (Total Responses n = 4,465) and Exemplary Quotes

| Theme and definition | Responses, n (%) | Exemplary quotes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Personal health and safety: Challenges or suggestions related to personal health, safety, and/or well-being, including both physical and mental/emotional health | 1,324 (30.2) | • We only have 1 surgical mask per person per week. In mid-March we had 2 physicians (myself included) and 5 [medical assistants] contract COVID-19. Then many of our family members became ill. One of our [medical assistant's] mothers ended up in the [intensive care unit] on the ventilator. (FL 414) • My employer needs to be able to provide universal testing for patients and health care care workers so that appropriate quarantining and treatment can occur and minimize the rate of spread in a health care setting. My employer also needs to provide optimum levels of [personal protective equipment] in all settings, not just the high-risk inpatient settings. (NFL 292) • I don't know. I'm having trouble helping myself most days and I feel like I'm just going through the motions. I feel guilty to use up resources for mental health that are available for front line workers since I'm at home. I had baseline depression/anxiety that is much worse and untreated. I am afraid for my life and what will happen to my child when I am forced to return to work if I get sick and die. (NFL 1,536) |

| 2. Patient care and safety: Challenges or suggestions related to caring for patients during the pandemic, including both COVID and other patients | 982 (22.4) | • Stress of trying to figure out what is safest, delaying care vs. sending someone for imaging or bringing them to clinic for exam or labs, delaying consults/referrals—every straightforward medical decision is now a complex analysis of risk vs. benefit without any textbook answer. (FL 116) • I'm a psychiatrist—My patients are starting to decompensate. Psychotic patients are becoming more psychotic, anxious patients are becoming more anxious, depressed patients are becoming more depressed. (NFL 1,477) • The deep sadness over elderly COVID patients being unable to have the comfort of family nearby and the loss of physical interaction with patients. (FL 399) • I am a pediatric intensivist taking care of older adults COVID patients. I last took care of [intensive care unit] adult patients in medical school in 2000. (FL 171) |

| 3. Financial/job security: Challenges or suggestions related to professional, personal or home finances, including loans or cost of living, salary, productivity loss, or job security | 910 (20.8) | • Salary decrease by 20% and voluntary days off without pay, or to keep full salary, need to volunteer to be part of the intubation team, [intensive care unit] team, or be deployed to high COVID-19 centers in [New York City] or New Jersey. (FL 30) • Simultaneously being in some situations where I treat persons under investigation with or who have COVID as a consultant but also at risk for pay cut due to loss of other clinical revenue. (FL 253) • I want to work and help patients, but there isn't a need right now… I have student loans (not all federal and forbearance-able), children, and a husband in fellowship in an incredibly high cost of living area. I (we) are crumbling. (NFL 19) • Rather than cutting lowest earners first, top earners including [Chief Executive Officer, Chief Operations Officer] need to take cuts first. (FL 60) |

| 4. Parenting/homeschooling: Challenges or suggestions related to caring for children and/or the home during the pandemic, including physical, psychological or educational needs | 676 (15.4) | • …trying to keep my teenagers safe and sane while running full time distance learning through their schools… (FL 30) • The biggest challenges at home are about our kids. Their school has transitioned to online classes, but the reality is that they are looking at a screen for class, watching YouTube or playing video games for the majority of the day. I worry about their mental and emotional health. And I worry about their physical health both from less activity but also if I were to bring the virus home to them. (NFL 1,552) • Provide grocery hours for providers in person and for online orders also, this could ease at least one stress…(NFL 468) • Supporting my children mentally—my husband and I are both physicians. I worry we are not supporting them as best we could. I know they are scared. (FL 289) • The fear in my kids eyes when I leave for work, I am keeping myself away from them as much as I can but it is impossible to achieve completely. Home schooling while working full time. (FL 28) |

| 5. Community and government support: Challenges or suggestions related to the government and/or the broader community's support for public health measures and health care workers | 564 (12.9) | • General public can stay home, respect the gravity of the situation and support those trying to work to care for patients in this challenging time. Also, this underscores that the business and politics of medicine does not work for the people we care for or the health care providers who provide the care. (NFL 165) • The general public should stop treating this like a joke and stay inside. The recent protests make it seem like they don't care about Health care workers let alone themselves. (FL 114) • General public needs to do their part and stay home and social distance. I don't need “free coffee or car washes.” I need them to stay home. (NFL 129) • Listen to scientific experts and stay home and stay clean. Put pressure on government to implement adequate testing, case tracking, appropriate quarantining, and adequate financial support for small businesses, unemployed individuals and their families during this time. (NFL 292) |

| 6. Organizational communication and relationships: Challenges or suggestions related to communication or relationship with their health care organization leadership | 537 (12.3) | • I would feel so much better if I knew there was enough PPE and that policies were not being dictated by supply. I feel that I can't trust my institution to do the right thing because I know their decisions are influenced by the lack of supply. They tried to say giving nebs did not require N95 and continue to say this. I can't help but wonder if they are saying that because they want to save masks. (NFL 1,529) • Too many administrators having too many meetings about the best way to practice medicine—these administrators don't know what it is like on the front lines. (NFL 74) • Administrators: Come into the [emergency room], Gown up and shadow a doctor for a complete shift at least once a week. See every patient with them, even if they are doing a high-risk procedure. Wear the same PPE they are wearing. (FL 324) • [Do] not require PTO/vacation for work related exposure, COVID symptoms, etc. It's terrible to know we are being forced to use all our paid time off for this year and next year (in advance) if we get COVID. (FL 60) |

| 7. Family health and safety: Challenges or suggestions related to the potential for family members to contract COVID, including strategies used to mitigate risk of transmission | 374 (8.5) | • Fear of bringing COVID home…I worry about my diabetic smoker husband catching it from me. I can't check on my depressed mother who lives alone. I call daily but it isn't the same… (FL 89) • Death of father-in-law during the lockdown—not COVID related—but died alone in hospital with very small funeral and inability to have friends and family around for comfort of my spouse, [mother-in-law] now alone and needing support but difficult given stay at home orders in our state…(NFL 1,021) • Fear of passing COVID to my family. I have a disabled child and a father who is elderly with many comorbidities. I have a husband with many comorbidities. (NFL 1,042) |

| 8. Work/life balance: Challenges or suggestions related to the tension, intersection and/or conflict between work and home roles and responsibilities during the pandemic | 363 (8.3) | • Parents call every day to make sure I'm okay, and ask if I can quit my job to be safe. (FL 1,774) • Allowing work from home in days with only virtual visits to help kids with schoolwork during the day… (FL 1,288) • Trying to complete telemedicine with my patients with the company of my 2 and 5 years [olds]. (NFL 1,074) • Not letting my work stress interfere with being present at home…(FL 1,269) • Work is home and home is work. Very little separating the two now. (NFL 571) |

| 9. Access to childcare: Challenges or suggestions related to finding, utilizing, or paying for outside childcare providers during the pandemic | 318 (7.2) | • Need someone to watch my child!!! School is out. After school program is closed and critical infrastructure workers can't have had contact with someone with COVID [for] their kids to be in daycare??? (NFL 75) • A daycare in the hospital or subsidized childcare would be great. (FL 110) • We are trying to avoid having our nanny come. My husband is still working 4/7 days per week, and I am working 3 late shifts in the [emergency department]. We are trying to juggle our schedules to avoid needing help, because while we know our own risk, we have no idea whether those we ask to help us are actually practicing safe social distancing. (FL 705) |

| 10. Spouse/partner relationship: Challenges or suggestions related to managing the relationship with a spouse or partner, including roles and responsibilities | 222 (5.1) | • My partner is not in health care plus his source of information is not very reputable. We argue quite a bit because our area has not been hit very hard yet and he thinks I'm blowing this out of proportion…(FL 244) • Tired of social distancing from my spouse. (FL 1,047) • Husband is not happy about having to take the kids almost solo. (FL 740) • …Spouse furloughed but not picking up the fair share of homeschooling or house work (FL 356) |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; PPE, personal protective equipment; PTO, paid time off.

“Knowing you were at risk and not being listened to was debilitating”—Work Concerns and Challenges

Frontline physicians were more likely than nonfrontline physicians to raise concerns related to Personal Health and Safety (67.8% vs. 48.4%, p < 0.001), Organizational Communication and Relationships (31.8% vs. 23.8%, p < 0.001), and Family Health and Safety (27.2% vs. 16.6%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). The theme of Personal Health and Safety focused on the challenges and needs related to both physical and mental/emotional health. Participants expressed fear of infection and frustration with a lack of sufficient PPE and adequate testing for health care workers. Participants also described the psychological challenges derived from the constant fear of infection, and from witnessing so many patients dying from COVID-19. The theme of Organizational Communication and Relationships reflected participants' frustration with health care administration, including poorly organized communication, a lack of transparency, implementation of policies that were seen as unfair and/or unsafe, and the perception that decision-making was being conducted without obtaining sufficient input from physicians. The theme of Family Health and Safety centered on the fear of bringing the virus home to family members, particularly elderly parents or medically fragile children. Participants described taking extensive measures to avoid contamination, including quarantining separately from their immediate families for extended periods of time, as well as high levels of guilt for the risk they felt they posed to their families.

FIG. 1.

Work-related concerns and challenges, identified by participants, stratified by frontline worker status (n = 1,700). Dark bars represent frequency of theme raised by frontline workers; light bars represent frequency of theme raised by nonfrontline workers. ***p < 0.001.

On the other hand, nonfrontline physicians were more likely than frontline physicians to raise concerns related to the themes of Patient Care and Safety (56.4% vs. 48.2%, p < 0.001) and Financial/Job Security (46.9% vs. 33.8%, p < 0.001). These physicians' concerns focused on their frustration with the limitations of telehealth and challenges of remote monitoring of chronic disease, particularly when caring for low-income, rural, and/or elderly populations, who were already considered high risk. The theme of Financial/Job Security highlighted how the epidemic has affected the financial health of the health care industry, including physicians. Physicians reported furloughs, pay cuts, and a drastic reduction in patient volumes and associated revenues. They expressed frustration at assumptions that physicians would be immune from financial instability, citing both the low salaries for those still in training and extensive student loan debt.

“I'm coming home to a full day of school work after I worked a full day.”—Home Concerns and Challenges

Four themes captured participants' concerns related to the home environment, with significant variation depending on their children's ages (Supplementary Appendix Table ST2). The theme of Parenting/Homeschooling focused on the concerns of managing children and the home, including household demands such as groceries and laundry. Stress related to remote learning was a particularly salient component of this theme, and participants with an elementary school-aged child were more likely to raise this theme compared to those without a child in this age group (44.0% vs. 31.1%, p < 0.001). Participants also described challenges related to managing their children's behaviors and mental health, with frontline providers highlighting the impact that their work has on their children's anxiety and fear for their parents' safety.

Participants with elementary school-aged children were also most likely to discuss concerns related to the theme of Work/Life Balance (28.4% vs. 13.7%, p < 0.001). This theme included explicit statements in which the participants focused on the intersecting challenges of work and home life during the pandemic. Examples included mentions of family pressure to leave their jobs to avoid COVID-19 risk, strategies to avoid bringing the stress of work into the home environment, and the challenges of doing telemedicine visits from home, especially for those with young children.

The theme of Access to Childcare, on the other hand, was most frequently raised by participants with a preschool-aged child (24.7% vs. 7.7%, p < 0.001). This theme focused on the challenges of accessing childcare with most schools and daycares closed. In addition to a lack of available childcare centers, participants described difficulties in finding caregivers (e.g., nannies, babysitters) who were willing to come into their homes because they were health care workers, as well as the inability to rely on elderly parents for childcare support, out of fear of spreading infection to these more vulnerable family members.

Participants with a preschool-aged child were also most likely to raise the theme of Spouse/Partner Relationship (15.8% vs. 9.5%, p < 0.001), which focused on the ways in which the challenges of the pandemic affected both the practical and interpersonal aspects of their relationship with their spouse or partner. These ranged from increased frustration with a spouse/partner's lack of contributions to increased caregiving demands to participant guilt when a spouse/partner was forced to take on the majority of these demands due to the participant's job. This theme also included feelings of emotional disconnection arising from stress or intentional physical distancing to reduce the risk of infection.

“The public can heed our advice, and the current White House leadership needs to act in the best interest of human life.”—Needs and Solutions

The frequency of themes raised in response to the question regarding needs and solutions (n = 1,157) is illustrated in Figure 2. The most frequently raised theme in response to the question of needs and solutions was Community and Government Support (n = 545, 47.1%). This theme included participants' frustration with lack of compliance with public health recommendations and the spread of misinformation related to the pandemic, and emphasized the need for strong support of public health measures, including stay-at-home orders, social distancing, and masking. They also encouraged the public to advocate for government support for health care workers (including increasing provision of PPE and stronger support for social distancing) and the public health response more broadly.

FIG. 2.

Frequency of themes reported as suggestions, needs, or solutions. Columns represent the frequency of each theme as referenced in response to the question of current needs or suggested solutions to address challenges related to the pandemic. The line represents the cumulative percent of reported themes.

Participants also suggested a range of solutions related to the themes described above, with a primary focus on work-related solutions. Personal Health and Safety suggestions (n = 364, 31.4%) focused on the urgent need for sufficient PPE, mental health services for health care workers, and to minimize exposure through teleworking or virtual patient encounters. Suggestions related to Organizational Communication and Relationships (n = 346, 29.9%) included the need for health care administrators within their organizations to listen to physicians involved in direct patient care to ensure that policies address their needs. Patient Care and Safety suggestions (n = 261, 22.6%) included better technical support for telehealth, urgent planning for safe means to provide outpatient care for non-COVID-19 patients, and essential improvements regarding access to testing for patients. Financial/Job Security solutions (n = 106, 9.2%) included supporting telehealth infrastructure to increase patient volumes, minimizing physician salary cuts and/or providing hazard pay, and loan deferment for those struggling with excessive debt from medical training.

Although home-related suggestions were less frequently raised, solutions included encouraging stores to provide special hours for health care providers and/or set aside certain items (e.g., toilet paper, cleaning supplies) to allow health care workers to manage their households despite their busy schedules, and better support for remote learning. Participants also described the urgent need for on-site childcare as well as subsidies to cover additional childcare costs incurred due to the pandemic.

Discussion

The results of this mixed-methods, cross-sectional survey of 1,806 physician–mothers illustrate key differences in the challenges faced by physician mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic based on both their personal and professional characteristics. Building upon existing studies including only frontline providers,29,30 we found key differences in the challenges faced at work for nonfrontline compared to frontline physicians, as well as variation based on the ages of physicians' children. Overall, the most frequently identified need expressed by physician mothers was for community and government support. Specifically, participants asked for strong support for public health measures, including stay-at-home orders, social distancing, and masking. This study complements and extends existing studies quantifying the impact of the pandemic on health care workers by providing uniquely rich and vivid insights regarding the mechanisms through which the pandemic has affected the vitality of this critical segment of the health care workforce.

Although studies have examined work-related challenges faced by frontline workers,29,31 to our knowledge this study is the first large-scale empirical examination of the intersection of work and home challenges faced by both frontline and nonfrontline physicians during the pandemic. This broader, comparative lens provides key insights for health care leaders and policymakers as they develop policies and practices to support health care workers throughout the pandemic. Our results suggest potential hypotheses for variation in resilience, stress, and anxiety observed in recently published studies examining the mental health impacts of the pandemic.32 Frontline physicians highlighted the need for PPE and strong organizational leadership and support through the pandemic, which has been suggested as a key factor impacting physicians' mental health during crisis.33 However, nonfrontline physicians—and particularly those in private or small group practices—are also being challenged by financial losses. An August 2020 survey by the Physicians Foundation, a nonprofit group, found that 8% of physicians have closed their offices in recent months, with an additional 4% planning to close within the year.34 If policymakers do not address this challenge, the closure of these practices could reshape the landscape of health care delivery in the United States and significantly impact access to health care for decades.35

An understanding of the intersection of both work and home challenges is essential to ensure that underlying gender disparities already present in medicine are not further exacerbated during the pandemic.36,37 While other studies have examined the work-related challenges of the pandemic, such as the shift to telehealth,38,39 our results suggest that an understanding of home challenges is also important when developing policies and appropriate expectations for physicians working from home, and particularly those with young children. Our study provides further evidence of the high burden of home responsibilities felt by many female physicians and necessary details regarding their nature and impact.40 The extent to which these gender disparities in caregiving roles have been exacerbated by the pandemic has been well documented in the broader academic and scientific community.41–43 There is an urgent need to directly address these challenges to prevent further exacerbating the high rates of burnout experienced by female physicians, the majority of whom are mothers.44,45

Finally, it is notable that the most frequently identified need expressed by physician mothers was for community and government support—even above their personal and family health and safety. At the time this article was written, COVID-19 prevalence and death rates are climbing more quickly than we have yet seen during this pandemic. To address many of the work and home challenges raised by participants, strong national leadership is essential, as is broad community support for public health efforts to prevent the virus's spread.

Important limitations of our study include the cross-sectional survey design, the inability to formally calculate a response rate, and possible selection bias in this convenience sample. Because our population included only physician-mothers, results may not be generalizable to all physicians, but given the sizeable number of women physicians in practice, understanding their experiences is important. Further, our study was conducted during a 2-week period early in the pandemic, and the landscape of both work and home life have undoubtedly evolved since this time. However, our findings also reflect longstanding challenges related to the intersection of work and home responsibilities for physician mothers that are relevant during and beyond the pandemic. Finally, while the distribution of study respondents based on race/ethnic background is generally consistent with that of the broader physician workforce,46 we were unable to examine specific or additional challenges that likely stem from the intersection of gender and racial bias experienced by physicians from diverse backgrounds.

Conclusions

The vitality of the physician workforce is integral to the health of the population, particularly in a time of a public health crisis. Given that women constitute the majority of medical school classes and the majority of actively practicing young physicians,47 hearing the voices of this critical component of the physician workforce is essential. However, it also is necessary to recognize that the female physician workforce is not homogenous and that the diversity in characteristics of both their home and work environments leads to variations in how individual physicians experience challenges raised by the pandemic. Leaders within health care organizations and the government need a deep understanding of these challenges in order to ensure robust public health policies, adequate equipment for personal safety and optimal patient care, and support to meet basic personal financial and family needs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Vanessa Nava, Nick Riano, and Rochelle Jones for technical support and those who participated from the Physician Moms Group for their contributions to this study.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author Disclosure Statement

M.C.H. is supported by the NIH (3U01HG010218-03S2-03S2 and 5UL1TR003142-02). K.S.M. is supported by the NIH (K23HL130648 and U01HL122998) and serves on the BREATHE Trial Steering Committee supported by Roivant/Kinevant Sciences. L.C.D. is supported by the NIH (P30 CA008748 and K07 CA184037). She receives author royalties for a textbook published by Multilingual Matters, an imprint of Channel View Publications, on the topic of language barriers in health care. U.S. is supported by the NIH (K24CA212294). She has received grant funding for unrelated work from NIH, the Agency for Health care Research and Quality, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, The California Health Care Foundation, Blue Shield of California Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the Commonwealth Fund. She is also supported by an unrestricted gift from the Doctors Company Foundation and holds contract funding from She holds contract funding from AppliedVR, InquisitHealth, and Somnology. She serves as am uncompensated scientific/expert advisor for nonprofit organizations HealthTech 4 Medicaid and HopeLab. She has been a clinical advisor for Omada Health, and an advisory board member for Doximity. C.M. is supported by several grants including the National Institutes of Mental Health (R01MH112420), Genentech, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (Grant 2015211), the California Health Care Foundation. She is a founding member of TIME'S UP Healthcare, but receives no financial compensation from that organization. In 2019, she received one-time speaking honoraria from Uncommon Bold. M.K.G. is supported by the NIH (R01HD070910, R03MD011654). R.J. has stock options as compensation for her advisory board role in Equity Quotient, a company that evaluates culture in health care companies; she has received personal fees from Amgen and Vizient and grants for unrelated work from the National Institutes of Health, the Doris Duke Foundation, the Greenwall Foundation, the Komen Foundation, and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan for the Michigan Radiation Oncology Quality Consortium. She has a contract to conduct an investigator initiated study with Genentech. She has served as an expert witness for Sherinian and Hasso and Dressman Benzinger LaVelle. She is an uncompensated founding member of TIME'S UP Healthcare and a member of the Board of Directors of ASCO. E.L. is supported by the NIH (grants DP2CA225433 and K24AR075060).

Funding Information

There was no directed funding for this study.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Elbay RY, Kurtulmuş A, Arpacıoğlu S, Karadere E. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in Covid-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res 2020;290:113130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2020;323:2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang C, Yang L, Liu S, et al. . Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. . Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rodriguez RM, Medak AJ, Baumann BM, et al. . Academic emergency medicine physicians' anxiety levels, stressors, and potential stress mitigation measures during the acceleration phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Bird SB, ed. Acad Emerg Med 2020;27:700–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wilson W, Raj JP, Rao S, et al. . Prevalence and predictors of stress, anxiety, and depression among healthcare workers managing COVID-19 pandemic in India: A nationwide observational study. Indian J Psychol Med 2020;42:353–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krukowski RA, Jagsi R, Cardel MI. Academic productivity differences by gender and child age in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2021;30:341–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kannampallil TG, Goss CW, Evanoff BA, Strickland JR, McAlister RP, Duncan J. Exposure to COVID-19 patients increases physician trainee stress and burnout. Murakami M, ed. PLoS One 2020;15:e0237301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Linos E, Halley M, Sarkar U, et al. . Anxiety levels among physician-mothers during the COVID pandemic. Am J Psychiatry 2021;178:203–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ganguli I, Sheridan B, Gray J, Chernew M, Rosenthal MB, Neprash H. Physician work hours and the gender pay gap—Evidence from primary care. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1349–1357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Adesoye T, Mangurian C, Choo EK, et al. . Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: A cross-sectional survey. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1033–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Perry-Jenkins M, Gerstel N. Work and family in the second decade of the 21st century. J Marr Fam 2020;82:420–453 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matt Krentz, Kos E, Green A, Garcia-Alonso J. Easing the COVID-19 Burden on Working Parents. Boston Consulting Group, 2020. Available at: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2020/helping-working-parents-ease-the-burden-of-covid-19 Accessed October13, 2020

- 14. Andersen JP, Nielsen MW, Simone NL, Lewiss RE, Jagsi R. COVID-19 medical papers have fewer women first authors than expected. Elife 2020;9:e58807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wehner MR, Li Y, Nead KT. Comparison of the proportions of female and male corresponding authors in preprint research repositories before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2020335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gupta K, Lisker S, Rivadeneira NA, Mangurian C, Linos E, Sarkar U. Decisions and repercussions of second victim experiences for mothers in medicine (SAVE DR MoM). BMJ Qual Saf 2019;28:564–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Adesoye T, Mangurian C, Choo EK, et al. . Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: A cross-sectional survey. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1033–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Choo EK, Girgis C, Han CS, et al. . High prevalence of peripartum depression among physician mothers: A cross-sectional study. AJP 2019;176:763–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Halley MC, Rustagi AS, Torres JS, et al. . Physician mothers' experience of workplace discrimination: A qualitative analysis. BMJ 2018;363:k4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yank V, Rennels C, Linos E, Choo EK, Jagsi R, Mangurian C. Behavioral health and burnout among physician mothers who care for a person with a serious health problem, long-term illness, or disability. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:571–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Adesoye T, Mangurian C, Choo EK, et al. . Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: A cross-sectional survey. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith M, Cortez FM. Doctors turn to social media to develop Covid-19 treatments in real time. March 24, 2020. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-24/covid-19-mysteries-yield-to-doctors-new-weapon-crowd-sourcing Accessed October15, 2020

- 23. Dedoose. SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, 2018. Available at: www.dedoose.com Accessed October15, 2020

- 24. Huberman AM, Miles MB. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualit Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101 [Google Scholar]

- 26. De Vries H, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Teleki SS. Using pooled kappa to summarize interrater agreement across many items. Field Methods 2008;20:272–282 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Ecucat Psychol Measures 1960;20:37–46 [Google Scholar]

- 28. IBM SPSS Statistics. IBM Corp, 2016. Available at: https://www-01.ibm.com/support/docview.wss?uid=swg21476197 Accessed October15, 2020

- 29. Firew T, Sano ED, Lee JW, et al. . Protecting the front line: A cross-sectional survey analysis of the occupational factors contributing to healthcare workers' infection and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Graham MS, et al. . Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e475–e483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2020;323:2133–2134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barzilay R, Moore TM, Greenberg DM, et al. . Resilience, COVID-19-related stress, anxiety and depression during the pandemic in a large population enriched for healthcare providers. Transl Psychiatry 2020;10:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Preti E, Di Mattei V, Perego G, et al. . The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: Rapid review of the evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2020;22:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. The Physicians Foundation. The physicians foundation 2020 physician survey: COVID-19 impact ediction. The Physicians Foundation, 2020. Available at: https://physiciansfoundation.org/research-insights/2020physiciansurvey Accessed November18, 2020

- 35. Abelson R. Doctors Are Calling It Quits Under Stress of the Pandemic. The New York Times, November 15, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/15/health/Covid-doctors-nurses-quitting.html Accessed November15, 2020

- 36. Brubaker L. Women physicians and the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2020;324:835–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Halley MC, Rustagi AS, Torres JS, et al. . Physician mothers' experience of workplace discrimination: A qualitative analysis. BMJ 2018;363:k4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Uscher-Pines L, Sousa J, Raja P, Mehrotra A, Barnett ML, Huskamp HA. Suddenly becoming a “virtual doctor”: Experiences of psychiatrists transitioning to telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. PS 2020;71:1143–1150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reilly SE, Zane KL, McCuddy WT, et al. . Mental health practitioners' immediate practical response during the COVID-19 pandemic: Observational questionnaire study. JMIR Ment Health 2020;7:e21237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yank V, Rennels C, Linos E, Choo EK, Jagsi R, Mangurian C. Behavioral health and burnout among physician mothers who care for a person with a serious health problem, long-term illness, or disability. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179):571–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cardel MI, Dean N, Montoya-Williams D. Preventing a secondary epidemic of lost early career scientists. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on women with children. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2020;17:1366–1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Myers KR, Tham WY, Yin Y, et al. . Unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientists. Nat Hum Behav 2020;4:880–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yildirim TM, Eslen-Ziya H.. The differential impact of COVID-19 on the work conditions of women and men academics during the lockdown. Gend Work Organ 2020. Aug 19;10.1111/gwao.12529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stentz NC, Griffith KA, Perkins E, Jones RD, Jagsi R. Fertility and Childbearing Among American Female Physicians. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2016;25:1059–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Templeton K, Bernstein CA, Sukhera J, et al. . Gender-based differences in burnout: Issues faced by women physicians. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, Washington, DC.: National Academy of Medicine, 2019. Available at: 10.31478/201905a Accessed October15, 2020 [DOI]

- 46. Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. AAMC. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018 Accessed January25, 2021

- 47. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. AAMC. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019 Accessed October15, 2020

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.