Abstract

Background

We address the question whether professional soccer players with and without macroinjury of the knee joint are at an elevated risk for knee osteoarthritis.

Methods

A systematic review with meta-analyses was conducted. The study protocol was prospectively registered (registration number CRD42019137139). The MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases were searched for relevant publications; in addition, forward searching was performed, and the listed references were considered. All steps of the process were undertaken independently by two reviewers, and any discordances were resolved by consensus. For all publications whose full text was included, the methods used were critically evaluated. The quality of the evidence was judged using the GRADE criteria.

Results

The pooled odds ratio for objectively ascertained osteoarthrosis of the knee was 2.25 (95% confidence interval [1.41–3.61], I2= 71%). When only radiologically ascertained knee osteoarthrosis was considered, the odds ratio was 3.98 [1.34; 11.83], I2= 58%). The pooled risk estimator in studies in which knee joint macroinjury was excluded was 2.81 ([1.25; 6.32], I2= 71%).

Conclusions

A marked association was found between soccer playing and knee osteoarthritis in male professional soccer players. For female professional soccer players, the risk of knee osteoarthritis could not be assessed because of the lack of data. Knee injuries seem to play an important role in the development of knee osteoarthritis in professional soccer players.

Professional soccer players run a total distance of up to 10 km or even more during a game, with frequent abrupt stops and accelerations. Their knees are therefore subject to high levels of stress (e1– e3). They are exposed to elevated risks of injury in the region of the knee joint (1, 2, e4), either macrotrauma (particularly ruptures of the cruciate ligaments or meniscus and fractures involving the knee joint) or microtrauma (as a consequence of sprains and contusions). For a professional soccer player, macrotrauma of the knee joint represents an occupational injury with benefit entitlement. If knee joint trauma in a professional soccer player leads to secondary osteoarthritis of the knee, this can be officially recognized as the consequence of an occupational injury (e5). However, primary osteoarthritis of the knee—in contrast to meniscopathy (coded OD no. 2102 in the German occupational diseases ordinance)—is not so far recognized as an occupational illness.

cme plus

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. The questions on this article can be found at http://daebl.de/RY95. Answers must be received by 28 January 2022.

Participation in the CME certification program is possible only over the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de

For the purposes of this publication, professional soccer players are those male and female players who earn their living from soccer. In Germany, soccer players who are paid, as opposed to playing as a hobby, have to be registered with statutory accident insurance funds by their clubs. One of the criteria is that the payments, including benefits in kind, have exceeded € 200 in each month of the contract period and amounted to at least € 8.50 per hour before deductions (e6).

A number of systematic reviews of the risk of knee osteoarthritis in professional soccer players have been conducted (3– 10), but they do not meet important quality criteria (e7– e9) such as publication of the study protocol (3– 10), double study selection (3, 7, 9), double data extraction (3– 9), assessment of study quality (3, 9), and disclosure of conflicts of interest (5, 8). Furthermore, some of the reviews explored the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in professional soccer players alone, with no comparison to another group (4, 6, 8, 10). Moreover, the reviews failed to include central primary studies and did not consider the role of knee macrotrauma when evaluating the risk of osteoarthritis (4, 6– 9). The present systematic review is intended to help close this gap in our knowledge. The following research questions were posed:

Research question 1: Are professional soccer players at higher risk of developing osteoarthritis of the knee?

Research question 1a: Are professional soccer players with no macrotrauma of the knee joint at higher risk of developing osteoarthritis of the knee?

Methods

A systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA criteria (e10) (PROSPERO registration number: CRD42019137139 [11]). The population was defined as “male and female professional soccer players,” the exposure as “playing soccer,” the outcome as “knee osteoarthritis,” and the relevant study types as cohort studies, case–control studies, and cross-sectional studies (e11). A comprehensive literature search was conducted. Two reviewers independently carried out all steps of the process. Critical assessment of the methods comprised a risk of bias procedure (12, 13). Meta-analyses of the study results were performed (using random effects models and the heterogeneity measure I2 [e12]). The GRADE criteria (14) were utilized to assess the overall quality of the evidence, using an adapted version of the Navigation Guide for epidemiological observational studies (15, 16). Details of the methods can be found in eTable 7 (eMethods).

Results

Results of the literature search

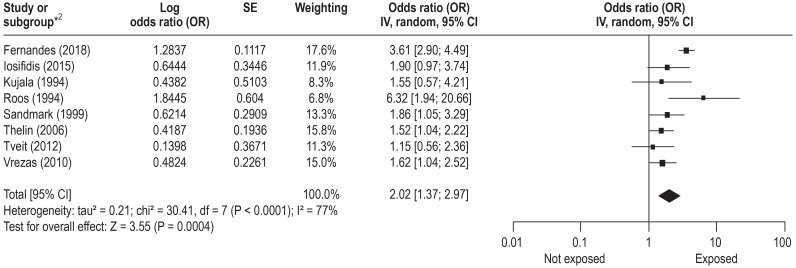

The results of the literature search are depicted in a flow chart (efigure 1). The database search revealed 15 450 records, and supplementary searches found 3208 records. After removal of duplicates, 12 951 references were screened. Of the 39 full texts screened, 30 were excluded on various grounds (16– 24, e13– e33; eTable 4).

eFigure 1.

PRISMA flow chart

* Studies with risk estimators for professional soccer, permitting the two research questions to be answered

Study characteristics

Nine studies—a retrospective cohort study (26), three case–control studies (26-28), and five cross-sectional studies (1, 29– 32)—fulfilled the inclusion criteria of the systematic review. All of them had been carried out in Europe. Professional soccer players were included in six of these studies (1, 25, 29– 32). Three studies concerned themselves with professional and amateur soccer (26– 28), and in one of these specific consideration of professional soccer was possible (27). Only in one study was exposure to soccer classified according to the total number of hours played (26). With the exception of one study in which the comparison group was made up of sports shooters (31), all studies drew their comparison groups from the population. Seven of the nine studies investigated only men, while two included women as well (27, 28). However, only effect estimators for men could be included in the meta-analyses. Operationalization of the outcome of knee osteoarthritis ensued via radiographs (1, 25, 28, 30, 31), knee joint replacement (27), hospital admission (25), or self-reporting of diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis by a physician or performance of joint replacement (29, 32). The characteristics of the individual studies are shown in eTable 5.

eTable 5. Study characteristics.

| Study | Study region | Time of recruitment/follow-up | Exposure group | Comparison group | Clinical endpoint (outcome) |

| Retrospective cohort study | |||||

| Kujala et al., 1994 | Finland | n.d. | Male previous professional soccer players (n = 313) who had represented Finland at least once at the Olympic Games, World Cup, European Championship, or at national level, recruited from a partial sample of the study by Sarna et al. (1993) (e88) Response rate (questionnaire): 84% Average age: 45.4 years (range 23–76) |

Male probands (n = 1712) from the population who had been classed as fully healthy at the time of their military training, matched for age and place of residence, recruited via public archives Response rate (questionnaire): 77% Average age: 44.1 years (range 24–86) |

Hospital admission due to knee osteoarthritis (according to the national register of hospital discharges, 1970–1990) (Excluded: infection of lower extremity, rheumatoid arthritis) |

| Studie | Study region | Time of recruitment/follow-up | Cases | Controls | Exposure |

| Case–control studies | |||||

| Sandmark & Vingard, 1999 | Sweden | n.d. | Male (n = 325) and female (n = 300) cases, born between 1921 and 1938, with knee joint replacement due to primary tibiofemoral knee osteoarthritis in the period 1991–1993 according to the Swedish knee replacement registry Response rate: Men: 88%, women: 79% (Excluded: trauma or surgery of the knee joint or surrounding structures, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic disease affecting the joints [poliomyelitis, rachitis, etc.], musculoskeletal malalignment) |

Male (n = 264) and female (n = 284) population controls, born between 1921 and 1938, recruited randomly from the Swedish population registry Response rate: Men: 80%, women: 77% (Excluded: trauma or surgery of the knee joint or surrounding structures, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic disease affecting the joints [poliomyelitis, rachitis, etc.], musculoskeletal malpositions) |

Professional or amateur soccer during the ages of 15 and 50 years |

| Thelin et al., 2006 | Sweden | n.d. | Male (n = 338) and female (n = 440) cases (age: ≤ 70 years) with advanced severe or moderate tibiofemoral knee osteoarthritis according to the radiographic registries of six southern Swedish hospitals or following knee joint surgery (osteotomy or joint replacement) or with moderate cartilage degeneration or a joint space of ≤ 3 mm Response rate: 94.3% (non-responder analysis performed) Average age (cases and controls): 62.6 years (range 51–70) (Excluded: knee osteoarthritis, minor cartilage degeneration, joint space ≥ 4 mm, knee osteoarthritis of Ahlbäck grade 1 oder 2, patellofemoral knee osteoarthritis, chronic inflammatory joint disease) |

Male (n = 293) and female (n = 402) population controls (age: ≤ 70 years), matched for age, sex, and commune, recruited from the Swedish population registry Response rate: 84.2 % (non-responder analysis performed) Average age (cases and controls): 62.6 years (range 51–70) |

Professional or amateur soccer for at least 1 year after the age of 15 years |

| Vrezas et al., 2010 | Germany | n.d. | Male cases (n = 295) with radiographically diagnosed knee osteoarthritis (Kellgren–Lawrence score ≥ 2) with chronic symptoms (age: 25–70 years), recruited via orthopedic departments and orthopedists in the community Response rate: 61% (non-responder analysis performed) |

Male population controls (n = 327; age: 25–70 years), recruited randomly from the residents’ registries of the cities Frankfurt and Offenbach, Germany Response rate: 55% (non-responder analysis performed) |

Hours spent playing soccer (whole lifetime; unclear whether professional or amateur soccer) |

| Studie | Study region | Time of recruitment/follow-up | Exposure group | Comparison group | Clinical endpoint (outcome) |

| Cross-sectional studies | |||||

| Fernandes et al., 2018 | UK | 12/2014–07/2015 | Male former professional soccer players (n = 1207) aged > 40 years who had played in the top four divisions in England, recruited via 22 professional football organizations (with a partial sample who had had radiographic examination of the knee joint: n = 470) Response rate: questionnaire 25.3%, radiographs n.d. Average age: 59.0 years (± 11.7) Body mass index (current): 27.3 kg/m 2 (± 3.2) |

Male probands (n = 4085) from the population who were not incurably ill, were capable of giving written informed consent, and whose primary care physicians discerned no other grounds for exclusion, recruited from12 primary care practices (with a partial sample who had had radiographic examination of the knee joint: n = 491) Response rate*1: questionnaire 23.8%, radiographs 1.2% Average age: 62.9 years (± 10.4) Body mass index (current): 27.5 kg/m 2 (± 4.7) |

Diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis by a physician (self-reported) Knee joint replacement (self-reported) (Given the inclusion and exclusion criteria, no data extraction of the radiographic examination results was performed, because no response data on the radiographic examinations in the professional soccer players were published and the response rate among the controls was 1.2%.) |

| Iosifidis et al., 2015 | Greece | n.d. | Male former professional soccer players (n = 121) aged ≥ 40 years who had played at national level and participated in at least one European Championship or World Cup and had been active up to the age of 25 years, recruited via sports organizations (with a partial sample who had had radiographic examination of the knee joint: n = 91) Response rate: 84.4% Average age (all professional athletes included): 50.1 years (± 8.5) Body mass index (all professional athletes included, at age 20 years): 22.3 kg/m 2 (±1.6) |

Male probands (n = 181) from the population aged ≥ 40 years, resident in the same region, who had been classed as fully healthy at the time of their military training (with a partial sample who had had radiographic examination of the knee joint: n = 163) Response rate: 86.6% Average age: 50.7 years (± 10.0) Body mass index (at age 20 years): 21.5 kg/m 2 (± 1.6) |

Clinical knee osteoarthritis (pronounced pain or functional impairment of knee joint in recent years and also at least one of the following clinical signs: limited mobility, pain, crepitus, malposition) Radiographically diagnosed knee osteoarthritis (Kellgren–Lawrence score ≥ 2, no information on whether or not a tangential radiograph of the patella was obtained) (Excluded: lower extremity surgery, bone or soft-tissue trauma, inflammatory joint disease) |

| Kujala et al., 1995 | Finland | 1985 | Male former professional soccer players (n = 31) who had represented Finland at least once at the Olympic Games, World Cup, European Championship, or at national level, recruited from a partial sample of the study by Sarna et al. (1993) (e88) Response rate: 83.8% Average age: 56.5 years (± 5.7) Body mass index (at age 20 years): 22.9 kg/m 2 (±1.4) |

Male professional sports shooters (n = 29) Response rate: 82.9% Average age: 61.0 years (± 4.3) Body mass index (at age 20 years): 22.49 kg/m 2 (± 2.3) |

Radiographically diagnosed knee osteoarthritis (Kellgren–Lawrence score ≥ 2) |

| Roos et al., 1994 | Sweden | 1988 | Male former professional soccer players (n = 71; top two divisions in Sweden) and amateur soccer players (n = 215; third or lower divisions in Sweden), all aged ≥ 40 years,), who had been active up to the age of 25 years,recruited from all 10 football clubs in the city of Malmö Response rate: 100% Average age: Professional soccer players: 62.7 years, amateur soccer players: 53.2 years |

Male probands (n = 572) from the population, matched for age, recruited randomly via the Swedish population registry Response rate: 100% Average age: 55.5 years |

Radiographically diagnosed knee osteoarthritis (The radiographic archives of a hospital and two private practices were searched for the knee radiographs of all participating soccer players and controls. Radiographs of 253 soccer players and probands were found. Radiographic knee osteoarthritis was diagnosed according to the criteria of Ahlback (1968) (e35): joint space in p.a. view of tibiofemoral joint only half as great as in the other compartment of the same knee joint or the same compartment of the contralateral knee joint or joint space height of > 3 mm in one compartment. Other changes, e.g., osteophytes were ignored.) |

| Tveit et al., 2012 | Sweden | n.d. | Male former professional soccer players (n = 397) who had been active at national or international level, recruited from an archived book on former professional athletes, via archives of the Swedish Olympic Committee, and from the study by Nilsson & Westlin (1971) (e89) Response rate: 74% Median age (of all investigated professional athletes): 70 years (range 50–93) |

Male probands (n = 1368) from the population, matched for age, recruited via the Swedish population registry Response rate: 64% Median age: 70 years (range 51–93) |

Diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis by a physician (self-reported) Knee joint replacement (self-reported) (Excluded: earlier knee joint fractures) |

*1 The response rate relates to the Knee Pain and Related Health in the Community Study, which covered men and women.n.d., No data

Results of the critical assessment of methods

Three studies (25, 26, 28) were found to have a low, four (29– 32) a high overall risk of bias. In two studies, different outcome-specific classifications of bias domains 4 and 5 led to two different assessments of the overall risk (1, 27). Information on the individual studies can be found in eTable 6.

eTable 6. Critical assessment of methods*1.

| Study | Year | Major domains | Minor domains | Overall risk | |||||||

|

1. Recruitment procedure & follow-up (in cohort studies) |

2. Exposure definition and measurement |

3. Outcome. Source and validation |

4. Confounding |

5. Analysis method |

6. Chronology |

7. Blinding of assessors |

8. Funding |

9. Conflict of interest |

|||

| Fernandes | (2018) | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ |

| Iosifidis | (2015) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | → | → | ↑ | → | → | → | ↓ |

| Kujala | (1994) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↑ |

| Kujala | (1995) | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↑ | → | ↓ |

| Roos a)*2 | (1994) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↑ |

| Roos b)*2 | (1994) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | → | → | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↓ |

| Sandmark a)*3 | (1999) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↑ | → | ↑ |

| Sandmark b)*3 | (1999) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | → | → | ↑ | → | ↑ | → | ↓ |

| Thelin | (2006) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↑ |

| Tveit | (2012) | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ |

| Vrezas | (2010) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

↓ Low risk of bias, ?high risk of bias, → unclear risk of bias

*1 Details of the assessment of the methods used in the individual studies can be requested from the authors.

*2 The two different assessments for Roos et al. (1994) relate to different odds ratios (in some cases calculated by the review authors). In calculating the odds ratio a) (6.32 [1.94; 20.66]), age and sex was considered, so domains 4 and 5 are rated as low risk, leading to classification of the overall risk as low. For all other odds ratios b), it is not clear whether the age was similar in the exposure and comparison groups, so domains 4 and 5 are rated as unclear risk and the overall risk is classified as high.

*3 The same applies to the different assessments for Sandmark & Vingard (1999). For one of the odds ratios a) (2.0 [1.4; 2.8]) calculated by the authors, adjustment was made for age among other factors. Moreover, only men were included in the study, so the variable “sex” was also considered. Domains 4 and 5 were thus rated as low risk, leading to classification of the overall risk as low. For the other odds ratios b), it is not clear whether the age was similar in the exposure and comparison groups, so domains 4 and 5 are rated as unclear risk and the overall risk is classified as high.

Study results

The results of the individual studies can be found in eTable 7, those of the meta-analyses in the Table.

eTable 7. The results of the studies included.

| Study | Clinical endpoint (outcome) | Prevalence or incidence, n (%) | Risk estimator | Remarks | ||||

| Effect estimator | Exposure group or cases | Comparison group or controls | Effect estimator | Effect size [95% CI] | Adjustment for confounders | |||

| Retrospective cohort study | ||||||||

| Kujala et al. (1994) | Hospital admission due to knee osteoarthritis | Outcome incidence | 5 (2.0) | 18 (1.3) | Odds ratio | Professional soccer: 1.55 [0.57; 4.21]*1 | Not adjusted Sex: Only men included Age: Similar average age of exposure and comparison groups |

For the sake of better comparability of results, the odds ratio was calculated, rather than the relative risk as is more usual for incidence. The relative risk was similarly high, at 1.54 [0.58; 4.11]. |

| Case–control studies | ||||||||

| Sandmark & Vingard (1999) | Knee joint prosthesis due to primary tibiofemoral knee osteoarthritis | Prevalence of exposure | Professional soccer: Men: 41 (12.6) Women: 0 (0.0) Amateur soccer: Men: 101 (31.1) Women: 5 (1.7) |

Professional soccer: Men: 19 (7.2) Women: 0 (0.0) Amateur soccer: Men: 77 (29.2) Women: 1 (0.4) |

Odds ratio | Professional AND amateur soccer: Men: 2.0 [1.4; 2.8] Professional soccer: Men: 1.86 [1.05; 3.29] *1 Amateur soccer: Men: 1.10 [0.77; 1.56]*1 Women: 4.80 [0.56; 41.31]*1 |

Professional AND amateur soccer: Age body mass index, physical strain at work/in the household/in leisure time: adjusted Professional soccer: Not adjusted Amateur soccer: Not adjusted Valid for all models: Sex: Only men included |

– |

| Thelin et al. (2006) | Radiographic diagnosis of tibiofemoral knee osteoarthritis or knee joint operation (osteotomy or joint replacement) | Prevalence of exposure | Men: 140 (41.4) Women: 5 (1.1) |

Men: 91 (31.2) Women: 6 (1.5) |

Odds ratio | Professional AND amateur soccer: Men: Model 1: 1.56 [1.12; 2.17] Model 2: 1.52 [1.04; 2.20] Model 3: 0.94 [0.61; 1.44] Women: Model 1: 0.6 [0.23; 2.50] |

Model 1: Not adjusted Model 2: Smoking, body mass index, heredity, work in construction: adjusted Model 3: Smoking, body mass index, heredity, work in construction, previous knee joint injury (fracture, ligament or tendon injury, meniscus injury): adjusted Valid for all models: Sex: Only men or only women included Age: Similar average age of cases and controls |

The study did not distinguish between professional and amateur soccer, so no odds ratios specifically for professional soccer are available. The analyses of models 1–3 for men were also adjusted for professional-level sport; however, this did change the results. These data were not included in the study. |

| Vrezas et al. (2010) | Radiographic diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis | Prevalence of exposure | No soccer: 178 (60.3) > 0–1 660 h: 29 (9.8) 1 660–4 000 h: 41 (13.9) 4 000–7 800 h: 32 (10.8) ≥7 800 h: 15 (5.1) |

No soccer: 208 (63.6) > 0–1 660 h: 35 (10.7) 1 660–4 000 h: 34 (10.4) 4 000–7 800 h: 19 (5.8) ≥ 7 800 h: 16 (4.9) |

Odds ratio | Professional AND amateur soccer: Model 1: Reference category: 1.0 > 0–1 660 h: 1.3 [0.7; 2.3] 1660–4 000 h: 1.9 [1.0; 3.1] 4 000–7 800 h: 2.2 [1.1; 4.4] ≥ 7 800 h: 1.2 [0.5; 2.8] Model 2: Reference category: 1.0 > 0–1 660 h: 1.1 [0.5; 2.1] 1 660–4 000 h: 2.0 [1.0; 3.8] 4 000–7 800 h: 2.2 (1.0; 5.0] ≥ 7 800 h: 1.4 [0.6; 3.6] Dichotomous analysis (no soccer vs. soccer at any time): 1.62 [1.04; 2.51] |

Model 1: Age, region: adjusted Model 2: Age, region, body mass index, cumulative lifting/carrying, kneeling/squatting, jogging/athletics: adjusted Dichotomous analysis: Age, region, body mass index, cumulative lifting/carrying, kneeling/squatting, jogging/athletics: adjusted Valid for all models: Sex: Only men included |

The study did not distinguish between professional and amateur soccer, so no odds ratios specifically for professional soccer are available. The odds ratio for dichotomous analysis was derived from a personal communication from one of the study authors (A.Seidler). |

| Cross-sectional studies | ||||||||

| Fernandes et al. (2018) | Diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis by a physician | Outcome prevalence | 341 (28.3) | 500 (12.2) | Relative risk | Professional soccer: Model 1: 3.53 [3.15; 3.96] Model 2: 3.73 [3.33; 4.17] Model 3: 2.69 [2.36; 3.07] Model 4: 2.18 [1.73; 2.77] |

Model 1: Not adjusted Model 2: Age, body mass index: adjusted Model 3: Age, body mass index, knee joint injury: adjusted Model 4: Age, body mass index, knee joint injury, Heberden’s nodes, knee joint malalignment at age of around 20 years, high-risk occupation for knee osteoarthritis, index finger/ring finger length ratio, comorbidities: adjusted Valid for all models: Sex: Only men included |

The adjustment for knee joint malalignment may be excessive, as professional soccer players are more likely to have a varus knee joint than the general population. The result in model 2 (3.61 [2.90; 4.49]) deviates somewhat from the figures in the study due to different calculation parameters in RevMan 5.3. |

| Knee joint replacement | 134 (11.1) | 157 (3.8) | Professional soccer: Model 1: 2.88 [2.31; 3.60] Model 2: 3.61 [2.90; 4.49] Model 3: 2.33 [1.84; 2.95] Model 4: 2.10 [1.42; 3.14] |

|||||

| Iosifidis et al. (2015) | Clinical knee osteoarthritis | Outcome prevalence | 11 (9.1) | 15 (8.2) | Odds ratio | Professional soccer: 1.11 [0.49; 2.50]*1 |

Not adjusted Sex: Only men included |

The study reported only odds ratios in relation to the whole population of all athletes investigated. In the case of calculation of an odds ratio for a prevalence of > 10%, the value could be overestimated in relation to the corresponding relative risk. |

| Radiographic diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis | 20 (22.0) | 21 (12.9) | Odds ratio | Professional soccer: 1.90 [0.97; 3.74]*1 |

||||

| Kujala et al. (1995) | Radiographic diagnosis of tibiofemoral and patellofemoral knee osteoarthritis | Outcome prevalence | 9 (29.0) | 1 (3.4) | Odds ratio | Professional soccer: Model 1: 12.3 [1.35; 112.06] Model 2: 5.21 [1.14; 23.8] |

Model 1: Age: adjusted Model 2: Type of sport, age, body mass index, occupational stress from heavy work work involving kneeling and squatting, knee joint injury: adjusted Valid for all models: Sex: Only men included |

The result in model 1 (12.3 [1.35; 112.06]) deviates somewhat from the figures in the study due to different calculation parameters in RevMan 5.3. |

| Radiographic diagnosis of tibiofemoral knee osteoarthritis | 8 (25.8) | 0 (0.0) | n.d. | – | – | |||

| Radiographic diagnosis of patellofemoral knee osteoarthritis | 5 (16.1) | 1 (3.4) | Odds ratio | Professional soccer: 5.38 [0.59; 49.20]*1 |

– | |||

| Roos et al. 1994) | Radiographic diagnosis of tibiofemoral knee osteoarthritis | Outcome prevalence | Professional soccer: All: 11 (15.5) With knee injury: 5 (33.3) Without knee injury: 6 (10.7) Amateur soccer: All: 3 (4.2) With knee injury: 4 (12.5) Without knee injury: 5 (2.7) |

All (matched to age of professional soccer players): 4 (2.8) With knee injury: 2 (15.4) Without knee injury: 7 (1.3) |

Odds ratio | Professional soccer: a) 11.47 [4.57; 28.79]*1 b) 6.32 [1.94; 20.66]*1 c) 5.73 [2.01; 16.29]*1 d) 9.46 [3.06; 29.24]*1 Amateur soccer: a) 2.7 [1.0; 6.8] b) 2.73 [1.07; 6.98]* 1 |

Professional soccer: a) Not adjusted b) Not adjusted, age: use of age-matched comparison probands c) Knee joint injury: adjusted d) Exclusion of participants with knee joint injury (non-adjusted) Amateur soccer: a) n.d. b) Not adjusted Valid for all models: Sex: Only men included |

Calculation of the odds ratio for c) with adjustment for knee joint injury was done by means of the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test. The odds ratio for amateur soccer players was reported in the study, but it was not made clear whether any adjustment was carried out. We therefore calculated this odds ratio—without adjustment—and found a slightly different value of 2.73 [1.07; 6.98]. |

| Tveit et al. (2012) | Diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis by a physician | Outcome prevalence | 67 (18.2) | 163 (13.0) | Odds ratio | Professional soccer: Model 1: 1.52 [1.11; 2.07] Model 2: 1.46 [1.04; 2.05] Model 3: 1.13 [0.75; 1.72] |

Model 1: Age: adjusted Model 2: Age, body mass index, occupational load: adjusted Model 3: Age, body mass index, occupational load, soft-tissue injury of knee joint: adjusted Valid for all models: Sex: Only men included |

The result in model 2 (1.15 [0.56; 2.36]) deviates somewhat from the figures in the study due to different calculation parameters in RevMan 5.3. |

| Knee joint replacement | 12 (3.3) | 30 (2.4) | Professional soccer:Model 1: 1.40 [0.71; 2.77] Model 2: 1.15 [0.56; 2.36] Model 3: 1.21 [0.38; 3.84] | |||||

*1 The review authors calculated this risk estimator based on the prevalence or incidence data given in the original study. No adjustment could be made for these calculations.

Bold type indicates statistical significance.

CI, Confidence interval; h, hours; n.d., no data

Table. Results of the meta-analyses.

| Analysis(n: number of studies) | Studies |

N (total) |

n (exposed) |

Odds ratio [95% CI] |

I 2 | Heterogeneity |

| Research question 1 | ||||||

| Meta-analysis 1: Soccer and objectively confirmed knee osteoarthritis | ||||||

|

Overall pooling (n = 6) |

Fernandes et al., 2018 Iosifidis et al., 2015 Kujala et al., 1994 Roos et al., 1994 Sandmark & Vingard, 1999 Tveit et al., 2012 |

9638 | 2042 | 2.25 [1.41; 3.61] |

71% | Substantial |

|

Sensitivity analysis 1: Radiographically confirmed knee osteoarthritis (n = 3) |

Iosifidis et al., 2015 Kujala et al., 1995 Roos et al., 1994 |

527 | 193 | 3.98 [1.34; 11.83] |

58% | Moderate to substantial |

|

Sensitivity analysis 2: Additional inclusion of studies with no differentiation between professional and amateur soccer (n = 8) |

Fernandes et al., 2018 Iosifidis et al., 2015 Kujala et al., 1994 Roos et al., 1994 Sandmark & Vingard, 1999 Thelin et al., 2006 Tveit et al., 2012 Vrezas et al., 2010 |

10 876 | 2494 | 2.02 [1.37; 2.97] |

77% | Substantial to considerable |

|

Sensitivity analysis 3: Study quality (inclusion of high-risk studies) (n = 4) |

Fernandes et al., 2018 Iosifidis et al., 2015 Sandmark & Vingard, 1999 Tveit et al., 2012 |

7790 | 1721 | 2.08 [1.20; 3.62] |

79% | Substantial to considerable |

|

Sensitivity analysis 4: Outcome assessment (exclusion of studies with self-reporting) (n = 4) |

Iosifidis et al., 2015 Kujala et al., 1994 Roos et al., 1994 Sandmark & Vingard, 1999 |

2691 | 472 | 2.12 [1.35; 3.34] |

24% | Probably not important |

| Research question 1a | ||||||

| Meta-analysis 2: Soccer and knee osteoarthritis with exclusion of macrotrauma of the knee joint | ||||||

|

Overall pooling (n = 3) |

Iosifidis et al., 2015 Roos et al., 1994 Sandmark & Vingard, 1999 |

1458 | 207 | 2.81 [1.25; 6.32] |

71% | Substantial |

| Meta-analysis 3: Soccer and knee osteoarthritis without exclusion of macrotrauma of the knee joint | ||||||

|

Overall pooling (n = 4) |

Fernandes et al., 2018 Kujala et al., 1994 Roos et al., 1994 Tveit et al., 2012 |

8795 | 1881 | 2.48 [1.22; 5.04] |

75% | Substantial |

| Meta-analysis 4: Soccer and knee osteoarthritis (without adjustment for knee joint injuries) | ||||||

|

Overall pooling (n = 4) |

Fernandes et al., 2018 Kujala et al., 1995 Roos et al., 1994 Tveit et al., 2012 |

7650 | 1672 | 4.02 [1.63; 9.92] |

82% | Substantial to considerable |

| Meta-analysis 5: Soccer and knee osteoarthritis (with adjustment for knee joint injuries) | ||||||

|

Overall pooling (n = 4) |

Fernandes et al., 2018 Kujala et al., 1995 Roos et al., 1994 Tveit et al., 2012 |

7650 | 1672 | 2.71 [1.55; 4.74] |

41% | Moderate |

CI, Confidence interval; n/N, sample size

Research question 1

The prevalence of radiographically confirmed knee osteoarthritis in the tibiofemoral joint—graded ≥ 2 according to Kellgren and Lawrence (1957) (osteophytes, joint space narrowing, or joint deformity) (e34)—was 22.0% and 25.8% in professional soccer players, against 0% and 12.9% in the respective comparison groups (30, 31). In another study, joint space narrowing of the tibiofemoral joint as defined by Ahlbäck (e35) was found in 15.5% of the professional soccer players and in 2.8% of the members of the comparison group (1). The studies do not report prevalence separately for the medial and lateral portions of the tibiofemoral joint. One study described the rates of Kellgren and Lawrence grade ≥ 2 knee osteoarthritis of the patellofemoral joint as 16.1% in professional soccer players and 3.4% in the comparison group (31).

In the majority of the studies (n = 7 of 9), the relative risk estimators for the association between soccer and knee osteoarthritis were, at 1.5 to 12.3, statistically significantly elevated (1, 26– 29, 31, 32).

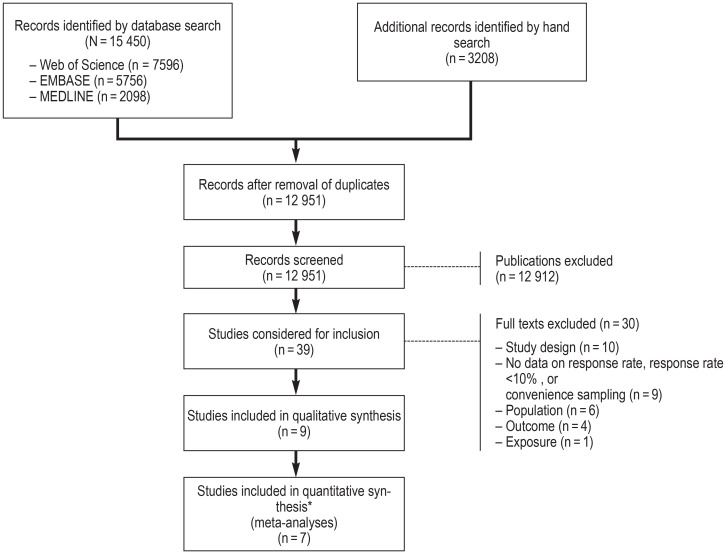

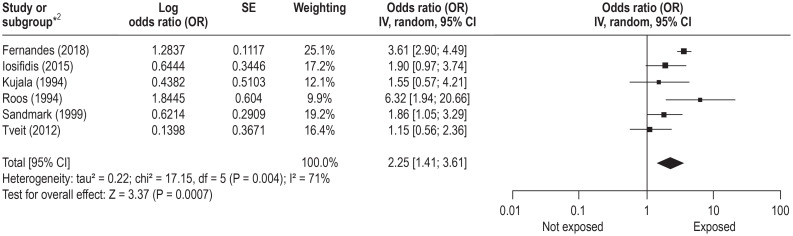

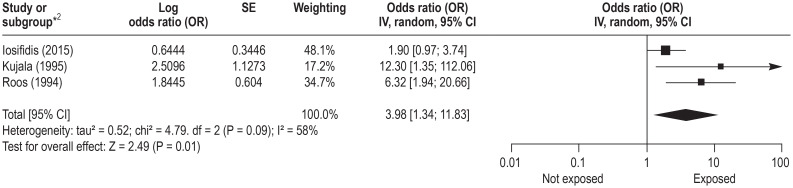

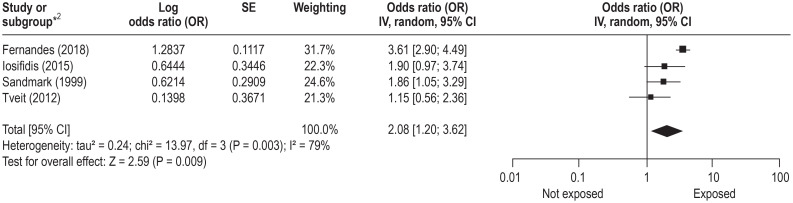

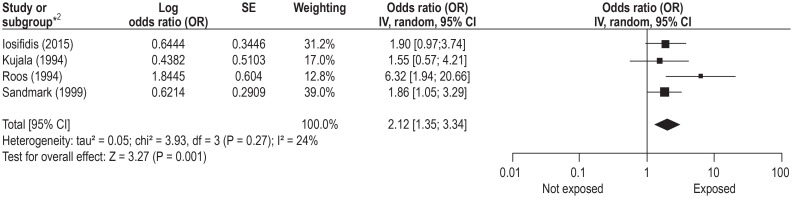

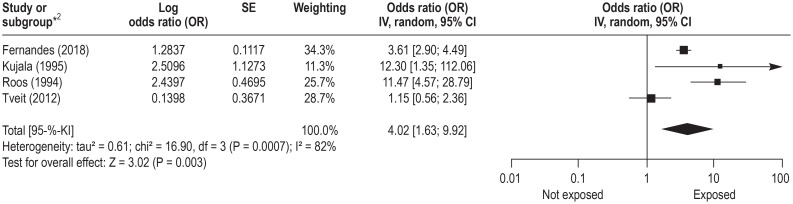

The pooled odds ratio (OR) for objectively confirmed osteoarthritis of the knee is 2.25 (95% confidence interval [1.41; 3.61], I2= 71%, n = 6) (figure 1) (1, 25, 27, 29, 30, 32). Looking only at radiographically confirmed osteoarthritis, the OR is 3.98 ([1.34; 11.83], I2= 58%, n = 3) (figure 2) (1, 25– 30, 32). Additional inclusion of studies that did not differentiate between professional and amateur soccer changed the OR only slightly (OR = 2.02 [1.37; 2.97], I2 = 77%, n = 8) (efigure 2) (1, 25– 30, 32). Restricting analysis to studies with a high overall risk of bias, the OR is 2.08 [1.20; 3.62], I2 = 79%, n= 4) (efigure 3) (27, 29, 30, 32). Excluding the two studies in which the outcomes were self-reported yields an OR of 2.12 ([1.35; 3.34], I2 = 24%, n= 4) (efigure 4) (1, 25, 27, 30).

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis of objectively confirmed knee osteoarthritis*1 in professional soccer players

*1 The meta-analysis included only studies in which the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis was obtained by objective means, i.e., radiographically, status post knee replacement, or registry data showing hospital admission due to knee osteoarthritis.

*2 In all studies the comparison group was made up of population-based probands.

95% CI, 95% Confidence interval; SE, standard error

Figure 2.

Sensitivity analysis 1: Meta-analysis of radiographically confirmed knee osteoarthritis*1 in professional soccer players

*1 The meta-analysis included only studies in which the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis was confirmed radiographically.

*2 The comparison groups were made up of population-based probands (Iosifidis et al., 2015; Roos et al., 1994) and professional sports shooters (Kujala et al., 1995).

95% CI, 95% Confidence interval; SE, standard error

eFigure 2.

Sensitivity analysis 2: Meta-analysis on the risk of knee osteoarthritis in professional and amateur soccer players*1

*1 The meta-analysis additionally included studies that did not differentiate between professional and amateur soccer.

*2 In all studies the comparison group was made up of population-based probands.

95% CI, 95% Confidence interval; SE, standard error

eFigure 3.

Sensitivity analysis 3: Meta-analysis on the risk of knee osteoarthritis in professional soccer players in studies with a high overall risk of bias*1

*1 The meta-analysis included only studies with a high overall risk of bias.

*2 In all studies the comparison group was made up of population-based probands.

95% CI, 95% Confidence interval; SE, standard error

eFigure 4.

Sensitivity analysis 4: Meta-analysis on objectively confirmed knee osteoarthritis in professional soccer players, excluding studies in which the outcome was determined by self-reporting*1

*1 The meta-analysis did not include the two studies that recorded the outcome “status post knee joint replacement” as reported by participants (Fernandes et al., 2018; Tveit et al. 2012).

*2 In all studies the comparison group was made up of population-based probands.

95% CI, 95% Confidence interval; SE, standard error

Research question 1a

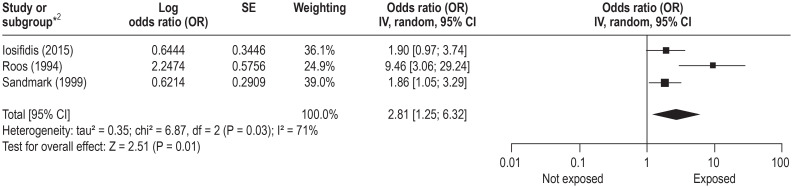

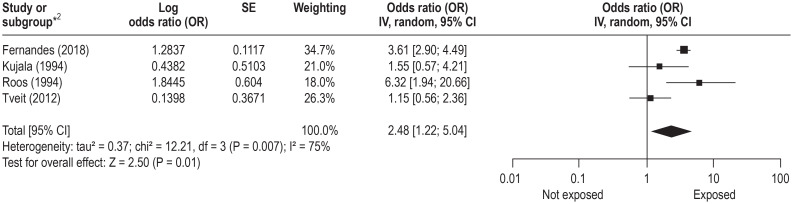

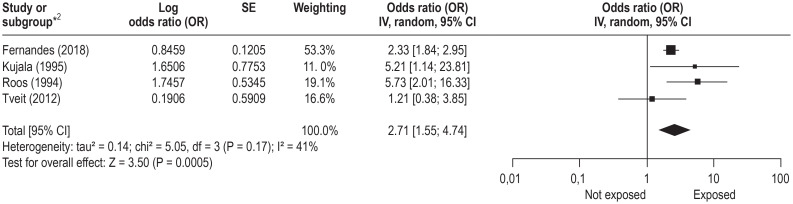

The pooled risk estimator in studies that excluded macrotrauma of the knee joint is 2.81 ([1.25; 6.32], I2 = 71%, n= 3) (figure 3) (1, 27, 30), against 2.48 ([1.22; 5.04], I2= 75%, n= 4) (figure 4) (1, 25, 29, 32) in studies that did not exclude such injuries. The pooled OR after adjustment for knee joint injuries is, at 2.71 ([1.55; 4.74], I2 = 41%, n= 4), much lower than that without adjustment (4.02 [1.63; 9.92], I2= 82%, n= 4]) (1, 29, 31, 32) (eFigures 5, eFigures 6).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis 2: Meta-analysis of the risk of knee osteoarthritis in professional soccer players, excluding those with macrotrauma*1

*1 The meta-analysis included only professional soccer players without macroinjuries.

*2 In all studies the comparison group was made up of population-based probands.

95% CI, 95% Confidence interval; SE, standard error

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis 3: Meta-analysis of the risk of knee osteoarthritis in professional soccer players with and without macrotrauma*1

*1 The meta-analysis included professional soccer players with and without macroinjuries.

*2 In all studies the comparison group was made up of population-based probands.

95% CI, 95% Confidence interval; SE, standard error

eFigure 5.

Meta-analysis 4: Meta-analysis of the risk of knee osteoarthritis in professional soccer players, without adjustment for knee joint injuries*1

*1 The meta-analysis included only risk estimators for which there was no adjustment for knee joint injuries.

*2 The comparison groups were made up of population-based probands (Fernandes et al., 2018; Roos et al., 1994; Tveit et al., 2012) and professional sports shooters (Kujala et al., 1995).

95% CI, 95% Confidence interval; SE, standard error

eFigure 6.

Meta-analysis 5: Meta-analysis of the risk of knee osteoarthritis in professional soccer players, with adjustment for knee joint injuries*1

*1 The meta-analysis included only risk estimators for which there was adjustment for knee joint injuries.

*2 The comparison groups were made up of population-based probands (Fernandes et al., 2018; Roos et al., 1994; Tveit et al., 2012) and professional sports shooters (Kujala et al., 1995).

95% CI, 95% Confidence interval; SE, standard error

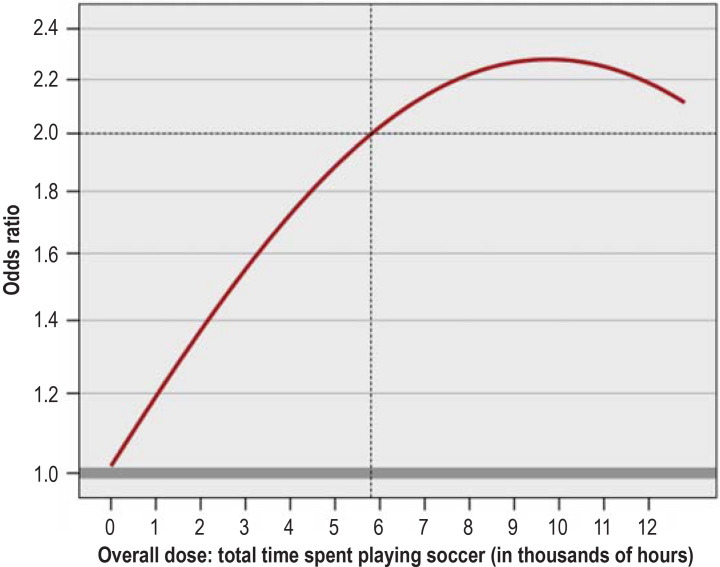

Dose–response gradient

Two studies showed a higher risk of knee osteoarthritis for professional than for amateur soccer players. In Roos et al. the risk was 2.73 [1.07; 6.98] for amateurs and 11.47 [4.57; 28.79] for professionals (1), while in Sandmark and Vingard it was 1.10 [0.77; 1.56] for amateurs and 1.86 [1.05; 3.19] for professionals (27).

The “doubling dose”

On the basis of a study that concerned itself principally with amateur soccer players (26), the doubling dose was around 2600 h with categorized analysis, while with non-linear analysis of the continuous data it was 5900 h (eMethods).

Evidence quality

The quality of the evidence on the link between professional soccer and objectively confirmed osteoarthritis of the knee was rated as moderate in the GRADE classification (eTable 9, Figure 1). When macrotrauma was excluded, the quality of the evidence on the association between professional soccer and objectively confirmed osteoarthritis of the knee (research question 1a) was formally rated low (eTable 9, Figure 3). Adjustment for knee joint injuries (efigure 6) revealed—with relatively high consistency of the studies analyzed—a pooled risk estimator similar to that found when excluding macrotrauma (figure 3); this further supports the evidence for affirmation of research question 1a.

eTable 9. Determination of the quality of evidence.

| Comparison/outcome | Number of studies | Overall risk of a study ↓ | Indirectness ↓ | Inconsistency ↓ | Lacking precision ↓ | Publication bias ↓ | Large effect size↑ | Residual confounding ↑ | Dose–response gradient↑ | Quality level |

|

Research question 1: Are professional soccer players at higher risk of developing osteoarthritis of the knee? | ||||||||||

|

Meta-analysis 1: Soccer and objectively confirmed knee osteoarthritis (figure 1) |

6 | 0*1 (no) |

0 (no) |

–1*2 (yes) |

–1 [1.41; 3.61] (yes) |

0 (no) |

+1 (2.25) (yes) |

0 (no) |

+1*3 (yes) |

Moderate |

|

Research question 1a: Are professional soccer players with no macrotrauma of the knee joint at higher risk of developing osteoarthritis of the knee? | ||||||||||

|

Meta-analysis 2: Soccer and knee osteoarthritis, excluding macrotrauma of the knee joint (figure 3) |

3 | –1*4 (yes) |

0 (no) |

–1*5 (yes) |

–1 [1.25; 6.32] (yes) |

0 (no)*6 |

+1 (2.81) (yes) |

0 (no) |

+1*7 (yes) |

Low |

*1 Four of the six studies included in this meta-analysis (Fernandes et al., 2018, Iosifidis et al., 2015, Sandmark & Vingard, 1999, Tveit et al., 2012) show a high risk of bias. However, the fact that the two studies with a low risk of bias (Kujala et al.,

1994, Roos et al., 1994) have a higher pooled effect estimator (3.02 [0.76; 11.95] than the whole meta-analysis (2.25 [1.41; 3.61]) speaks against downgrading.

*2 Four of the six studies included in this meta-analysis (Fernandes et al., 2018, Iosifidis et al., 2015, Sandmark & Vingard, 1999, Tveit et al., 2012) show a high risk of bias. However, the fact that the two studies with a low risk of bias (Kujala et al., 1994, Roos et al., 1994) have a higher pooled effect estimator (3.02 [0.76; 11.95] than the whole meta-analysis (2.25 [1.41; 3.61]) speaks against downgrading.

*3 In the course of the review a possible exposure–effect relationship emerged, in that two studies showed a higher risk of knee osteoarthritis for professional than for amateur soccer players (Roos et al., 1994, Sandmark & Vingard, 1999). Moreover, an exposure–effect relationship was found in a study that was carried out predominantly in amateur soccer players (Vrezas et al.,2010).

*4 All three of the studies included in this meta-analysis (Iosifidis et al., 2015, Roos et al., 1994, Sandmark & Vingard, 1999) show a high risk of bias.

*5 1. The point estimators of the individual studies vary very widely.

2. The confidence intervals overlap only very slightly.

3. The statistical heterogeneity test shows a low level of significance (p = 0.03).

4. I 2 is high, at 71%.

*6 Assessment limited owing to the low number of studies.

*7 In the course of the review a possible exposure–effect relationship emerged, in that two studies showed a higher risk of knee osteoarthritis for professional than for amateur soccer players

(Roos et al., 1994, Sandmark & Vingard, 1999). Moreover, an exposure–effect relationship was found in a study that was carried out predominantly in amateur soccer players (Vrezas et al.,2010).

Discussion

This systematic review found that male professional soccer players have a 2.3-fold risk of knee osteoarthritis compared with the male general population (OR 2.25). For radiographically confirmed osteoarthritis, the risk is even higher, at fourfold (OR 3.98). However, no differentiation can be made between the tibiofemoral joint and the patellofemoral joint. Injuries to the knee seem to play a large part in the development of osteoarthritis of the knee joint in professional soccer players. Even after exclusion of or adjustment for macrotrauma of the knee joint, the risk of knee osteoarthritis is still increased 2.7-fold (OR 2.81 and 2.71, respectively). Given this elevated risk, it must be assumed, despite the formally limited quality of the evidence, that professional soccer players have a distinctly increased risk of knee osteoarthritis.

Based on the findings of a study that predominantly investigated amateur soccer players, the doubling dose, i.e., the cumulative time spent playing soccer that doubles the risk of knee osteoarthritis, is around 2600 h in categorized analysis and 5900 h with non-linear analysis of the continuous data. Owing to the focus on amateurs, however, this doubling dose cannot be assumed to apply to professional soccer players.

Three earlier systematic reviews also found elevated pooled risk estimators for osteoarthritis of the knee in professional soccer players (3, 7, 9). The results of relevant primary studies that we excluded because they were insufficiently representative were very heterogeneous in respect of research question 1—in contrast to the overall consistency of the findings in the studies we included (16– 24). With regard to the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in soccer players, two previously published reviews reported higher levels (40–80% [4] and 14–80% [8]) than found in our work (3–29%).

The results of numerous uncontrolled cross-sectional studies point to the influence of injuries to the knee joint—a frequent occurrence in professional soccer players (e36)—on the later development of knee osteoarthritis in these athletes (33– 40, e37, e38). The knee joint injuries commonly experienced in professional soccer include anterior cruciate ligament ruptures, meniscus injuries, and lateral ligament ruptures (35, e39– e42). A number of systematic reviews show that programs specifically designed to prevent such injuries in professional and amateur soccer, such as FIFA 11+, have proved effective in reducing the risk of injury in randomized controlled trials (e43– e47). FIFA 11+ is a 20-min training unit that comprises running, stretching, and strengthening exercises.

In one study, osteoarthritis of the knee was the most frequently occurring manifestation of osteoarthritis in retired male professional soccer players—followed by osteoarthritis of the ankle joint, hip joint, and spinal column (e48). Other studies have reported osteoarthritis in joints other than the knee in professional soccer players: the ankle joint (e49), the hip joint (e50, e51), and the cervical spine (e52, e53). Ex-soccer players with osteoarthritis have a poorer quality of life than those without osteoarthritis (e48, e54, e55).

Besides the above-mentioned injuries as risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in professional soccer, other sport-specific phenomena are also thought to constitute stress factors for the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joints. These include running fast (e56– e61), stepping sideways when dribbling the ball around an opponent (e61, e62), shooting the ball (e63), and continual accelerations and abrupt stops (e3, e64). During a 90-min game of soccer, male players cover a mean distance of around 11 km, including 0.7–0.9 km running fast (20–25 km/h) and 0.2–0.3 km sprinting (> 25 km/h) (e1, e3). The distance covered per game depends on the player’s position: it is lowest for goalkeepers, followed by central defenders, strikers, left/right fullbacks, and midfielders (e3, e65, e66). Female professional soccer players cover a mean distance of around 10 km per game, including 2.5 km at high speed (12.2–19.0 km/h) and 0.6 km sprinting (> 19 km/h) (e64).

Only a small number of studies on knee osteoarthritis in female professional soccer players have been published, none of them fulfilling the criteria for inclusion in this systematic review (22, 36, 39, e38), although female players make up around 1 116 000 of the 7 132 000 members of the German Football Association (DFB) (e67). The only one of these studies that featured a control group found a fivefold risk for osteoarthritis of the knee in female soccer players (22). The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the non-controlled cross-sectional studies was in the range 13.8–51 % (36, 39, e38).

The methods of this systematic review

One strength of this systematic review is exclusion of studies that were insufficiently representative owing to the response being unreported or very low (< 10%) and/or use of convenience sampling, in order to avoid including studies affected by selection bias in the data evaluations and meta-analyses.

In the course of critical evaluation of the methods, body mass index was not included as a relevant confounder in the assessment of possible distortion of the study results by confounders, because it can occur not only as a confounder but also as an intermediate factor in the association between soccer and knee osteoarthritis.

Self-reporting of knee joint replacement was included as an outcome in the meta-analysis of objectively confirmed knee osteoarthritis, because recall bias is improbable.

The meta-analysis of radiographically confirmed knee osteoarthritis included one study in which the members of the comparison group were not probands drawn from population, but professional sports shooters (31). The corresponding risk estimator (12.30) was much higher than the risk estimators of the other studies included in this meta-analysis (1, 30) (OR 1.90 and 6.32), which may explain why the pooled risk estimator was higher for radiographically confirmed knee osteoarthritis (OR 3.98) than for objectively confirmed knee osteoarthritis (OR 2.25).

The review includes studies that investigated both amateur and professional soccer (14, 26– 28) without differentiating between the two in their presentation of the results with regard to the occurrence of knee osteoarthritis. These results were excluded from the meta-analyses, which were restricted to risk estimators for professional soccer.

Conclusions

The findings of this systematic review show a clear association between soccer and the development of knee osteoarthritis. The evidence quality is moderate, and some aspects of the results display high heterogeneity. Even after exclusion of or adjustment for macrotrauma of the knee joint, the risk of knee osteoarthritis incurred by male soccer players was still 2.7 times higher (OR 2.81 and 2.71, respectively) than in probands drawn from the population. The data are too sparse to permit any conclusions on the risk of knee osteoarthritis in female soccer players.

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The population comprised professional soccer players of all ages. If dedicated professional soccer studies did not permit calculation of the dose–response gradient, studies were also included that investigated not only professional but also amateur soccer. In that case, the exposure was graded as follows: professional soccer, amateur soccer, no soccer. Moreover, studies in which professional and amateur soccer were considered together were included, as were those where it was unclear whether professional soccer, amateur soccer, or both were concerned.

Only exposure to soccer as played according to the rules of the sport’s governing body (Fédération Internationale de Football Association, FIFA) was included. Studies on American football and Australian rules football were not considered.

All persons in other employment, including in some cases occupations involving no major strain on the knee, e.g., office work, were viewed as suitable for the comparison group.

The outcome of interest was knee osteoarthritis. Every kind of operationalization (radiological or arthroscopic diagnosis, status post knee joint replacement, clinical examination, disease code in registry data, subjective reports of the diagnosis being made, etc.) was relevant. Knee joint symptoms with no evidence of the diagnose of knee osteoarthritis were left out of consideration, as were other diseases of the knee such as meniscus lesions, cruciate ligament ruptures, or lateral ligament ruptures.

The study designs included were epidemiological observational studies, i.e., cohort, cross-sectional, and case–control studies. Clinical observational studies (case series, case reports), qualitative studies, studies without an English abstract, popular science media, and abstracts with no corresponding full text were not included. Studies published from 1980 onward were considered for inclusion, with no limitations regarding study region or language of publication. Studies with no data on participation rate or a participation rate under 10% were left out of consideration, as were those with convenience sampling of the study groups. A decisive factor was the proportion of individual soccer players that participated: a study based on a self-selected group of soccer clubs was included if the response rate for the individual players was at least 10% (etable 1).

Search strings for the electronic database survey

The electronic databases MEDLINE, EMBASE (via Ovid), and Web of Science were searched on 26 March 2019. The search period was defined as beginning in 1980.

The search strategy, designed to be sensitive, contained terms concerning exposure and outcome. The results of the electronic literature search were checked for duplicates. The three search strings were validated against 12 predefined key studies (1, 17 – 19, 22, 23, 30 – 32, e14, e68, e69)—two of which, however, were not indexed in any of the three databases searched (17, 22). The remaining 10 publications were found by the search strings.

EMBASE (Ovid):

MEDLINE (Ovid):

Web of Science Core Collection:

Studies used for forward searching

A forward search was conducted in the Web of Science database, using the included full texts and other primary studies relevant to the topic (etable 2).

Studies used for reference list searching

The reference lists of all finally included full texts and relevant primary studies and review articles were screened (etable 3).

Study selection

The titles, abstracts, and full texts of the references identified by the database search were screened by two reviewers working independently of each other (UBA, AF). Discrepant assessments were discussed, and if no consensus could be reached a third reviewer (AS) was consulted. A single reviewer (AF) screened the reference lists of the titles and/or abstracts identified by forward searching or reference list inspection. If on this basis an article appeared potentially suitable for inclusion, the corresponding full text was examined by the same reviewer. The articles she determined to be suitable were then checked by a second reviewer (UBA). A set of rules was followed for screening of titles, abstracts, and full texts. Both parts of screening began with a pilot phase. The extent of agreement between the two reviewers was assessed using Cohen’s kappa (e70).

Data extraction

The data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers (UBA, AF), who recorded study data on reference, methods, population, exposure, and outcome in standardized data extraction tables.

The following details were documented in the standardized data extraction tables:

The following risk estimators were used to measure the relative risk of knee osteoarthritis: prevalence ratio, relative risk, odds ratio, hazard ratio.

In a pilot phase, the data extraction was tested independently by two reviewers in one of the studies selected for inclusion (29). The extractions were compared and any discrepancies discussed.

Critical evaluation of methods

Critical evaluation of the primary studies was carried out by two reviewers independently of each other (UBA, AF). Discordances were resolved in consensus. A risk of bias procedure based on Ijaz et al. and Kuijer et al. was used (12, 13).

Validated checklists were used to assess the risk of bias in nine important areas, classing the risk as low, high, or unclear.

The following six domains were defined as major domains:

Three domains were considered minor:

A study’s overall risk of bias was determined on the basis of the six major domains. If the risk was classified as low in each of the major domains, then the overall risk of bias was low. Otherwise, the overall risk of bias was classed as high.

Statistical analysis

The study results were summarized descriptively and in meta-analyses. Meta-analyses were conducted whenever at least three primary studies could be included. Owing to the heterogeneity of the studies, the random effects model was used for this purpose. The stated measure of heterogeneity was the I2 value. The presence of publication bias was assessed with funnel plots. The analyses were carried out using RevMan 5.3.

For research question 1, a meta-analysis on objectively confirmed knee osteoarthritis was performed (meta-analysis 1). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to explore radiographically confirmed knee osteoarthritis (sensitivity analysis 1), the additional inclusion of studies that did not differential between professional and amateur soccer (sensitivity analysis 2), the influence of study quality (sensitivity analysis 3), and the effect of self-reporting (sensitivity analysis 4).

To answer research question 1a, the pooled risk estimators of the studies that excluded macrotrauma (meta-analysis 2) were compared with the corresponding risk estimators of the studies that did not exclude macrotrauma (meta-analysis 3). Furthermore, the pooled risk estimators were compared between professional soccer players with and without adjustment for knee joint injuries (meta-analyses 4 and 5). For this purpose, the only studies included were those featuring models both with and without such adjustment. As surrogate for a dose–effect gradient, amateur and professional soccer players were compared separately with a non-soccer-playing group.

Determination of evidence quality

The GRADE procedure (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) was used to assess the overall quality of the evidence, using an adapted version of the navigation guide for epidemiological observational studies (14, 15). Three quality classes were distinguished: high, moderate, and low. The studies were initially credited with moderate quality, because the evidence came from observational studies. On the basis of the following criteria, the evidence quality could be lowered by one or two levels (level: 0, -1, or -2):

Results

The agreement between the two reviewers who screened the titles and abstracts identified by the database search was classified as moderate, with a kappa of 0.44 (e73), despite 99.5% concordance. For full texts, the agreement between the two reviewers was substantial, with a kappa of 0.75 (efigure 1) (e73).

Calculation of doubling dose

The doubling dose is calculated on the basis of those among the studies included for analysis in which the exposure–risk relationship between the cumulative exposure to soccer and the diagnosis of radiographically confirmed osteoarthritis of the knee was known. In fact, this was the case only for one study (26, e74). In this study, no differentiation was made between professional and amateur soccer. The inverse U-shaped risk curve for soccer described in the publication, which suggests a healthy-athlete effect, cannot be portrayed properly with a linear model, and for this reason two other routes were followed to calculate the doubling dose:

1. From the publication concerned (26), the category of exposure was chosen for which the resulting risk estimator was closest to the doubling risk —an odds ratio of 2.0. This was the second category (1660 ≤ 4000 h). The median exposure of the control probands in this category was then taken as the doubling dose.

2. The exposure–risk relationship was depicted in a reanalysis of the primary data (AS) with a second-degree polynomial. The first intersection of the risk curve with the parallels to the x-axis at Y = 2 was taken as the doubling dose (eTable 8, eFigure 7).

exp soccer/

soccer.mp.

exp football/

football.mp.

sport$.mp.

exp athlete/

athlete$.mp.

exp soccer player/

soccer player$.mp.

exp football player

football player$.mp.

sportsm?n.mp.

or/1–12

exp knee osteoarthritis/

knee osteoarthriti$.mp.

knee osteoarthro$.mp.

knee OA.mp.

gonarthro$.mp.

gonarthriti$.mp.

knee arthriti$.mp.

knee arthro$.mp.

((knee$ or joint$ or femorotibia$) adj3 (pain$ or ach$ or discomfort$ or stiff$)).mp.

((knee or femorotibia$ or joint) adj5 (osteoarthritis or osteoarthrosis or cartilage or joint degeneration or cartilage degeneration or degenerative joint disease or degenerative arthritis)).mp.

or/14–23

and/13,24

limit 25 to yr=“1980 -Current“

exp SOCCER/

soccer.mp.

exp FOOTBALL/

football.mp.

sport$.mp.

exp athletes/

athlete$.mp.

soccer player$.mp.

football player$.mp.

sportsm?n.mp.

or/1–10

exp Osteoarthritis, Knee/

knee osteoarthriti$.mp.

knee osteoarthro$.mp.

knee OA.mp.

gonarthro$.mp.

gonarthriti$.mp.

knee arthriti$.mp.

knee arthro$.mp.

((knee$ or joint$ or femorotibia$) adj3 (pain$ or ach$ or discomfort$ or stiff$)).mp.

((knee or femorotibia$ or joint) adj5 (osteoarthritis or osteoarthrosis or cartilage or joint degeneration or cartilage degeneration or degenerative joint disease or degenerative arthritis)).mp.

or/12–21

and/11,22

limit 23 to yr=“1980 -Current“

TS=(soccer OR football OR athlete* OR sport* OR “soccer player” OR “soccer players” OR ”football player” OR ”football players” OR sportsman OR sportsmen)

TS=(“knee osteoarthrosis” OR “knee osteoarthritis” OR gonarthrosis OR gonarthritis)

TS=(knee OR joint OR femorotibia*)

TS=(pain OR ach* OR discomfort* OR stiff* OR osteoarthritis OR osteoarthrosis OR cartilage OR “joint degeneration” OR “cartilage degeneration” OR “degenerative joint disease” OR “degenerative arthritis”)

#3 AND #4

#2 OR #5

#1 AND #6

Reference: study authors, year of publication

Methods: study design, study location, time of recruitment and follow-up

Population: number of participants, response rate, follow-up rate, sex, age, inclusion and exclusion criteria

Exposure: type of exposure, duration of exposure, league

Outcome: How diagnosis was made, severity of osteoarthritis, symptoms

Results: Prevalence or incidence data, risk estimators (including listing of confounders)

Recruitment prodecure and follow-up (in cohort studies)

Exposure definition and measurement

Outcome: source and validation

Confounding

Analysis method

Chronology

Blinding of assessors

Funding

Conflict of interest

The overall risk of a study (study limitations)

Indirectness

Inconsistency

Imprecision

-

Publication bias

With the following criteria, the evidence quality could be raised by one or two levels (level: 0, +1, or +2):

Large magnitude of effect

Residual confounding

-

Dose–response gradient

Starting from the baseline level (moderate), the levels for all criteria were added together to determine the overall quality of the evidence.

The Clinical Perspective.

The cartilage of professional soccer players’ femorotibial and femoropatellar joints is exposed to extreme stress from various sport-specific actions. These include running fast, stepping sideways when dribbling the ball around an opponent, shooting the ball, and continual accelerations and abrupt stops. Furthermore, macrotraumas of the knee joint such as ruptures of the cruciate and lateral ligaments, meniscus ruptures, and fractures involving the knee joint may damage the articular cartilage. One possible consequence is knee osteoarthritis. This is also indicated by the results of epidemiological studies, which have shown that the risk of knee osteoarthritis in male professional soccer players is at least double that in the male general population.

eFigure 7.

Exposure–risk gradient for soccer playing and knee osteoarthritis (second-degree polynomial), calculated according to Vrezas et al. (2010) and Seidler et al. (2008)

eTable 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

| Population | ● Professional soccer players ● No age limit |

● Amateur soccer players (some studies on amateur soccer were included in order to calculate a dose–response gradient) |

| Exposure | ● Soccer | ● American football and Australian rules football |

| Comparison | ● Persons in other employment, including in some cases occupations involving no major strain on the knee, e.g., office work | / |

| Outcome | ● Knee osteoarthritis ● Principal analysis: – Radiologically and arthroscopically diagnosed – Status post knee joint replacement ● Sensitivity analyses – Diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis solely on basis of clinical examination – Radiologically, low-grade osteoarthritis of knee joint – Diagnoses based on disease codes in registry data – Subordinate: purely subjective information that diagnosis was made |

● Knee joint symptoms with no evidence of the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis ● Other diseases of the knee such as meniscus lesions, cruciate ligament ruptures, or lateral ligament ruptures |

| Study design | ● Epidemiological observational studies – Cohort studies – Cross-sectional studies – Case–control studies ● Study period: from 1980 ● Study region: all ● Languages: all ● Studies with response rate ≥ 10 % among both the professional soccer players and the comparison probands, as well as representative recruitment of the study groups |

● Clinical observational studies (case series, case reports) ● Qualitative studies ● Only abstract available ● Studies with no English abstract ● Popular science media ● Studies with no data on response rate and studies with response rate < 10 % among both the professional soccer players and the comparison probands, as well as convenience sampling of the study groups |

eTable 2. Studies used for forward searching.

| Study | Date | Number of studies citing the study |

| Studies included for analysis | ||

| Fernandes et al. (2018) (29) | 18 June 2019 | n = 5 |

| Iosifidis et al. (2015) (30) | 18 June 2019 | n = 9 |

| Kujala et al. (1994) (25) | 18 June 2019 | n = 162 |

| Kujala et al. (1995) (31) | 18 June 2019 | n = 266 |

| Roos et al. (1994) (1) | 18 June 2019 | n = 112 |

| Sandmark & Vingard (1999) (27) | 18 June 2019 | n = 46 |

| Thelin et al. (2006) (28) | 18 June 2019 | n = 56 |

| Tveit et al. (2012) (32) | 18 June 2019 | n = 59 |

| Vrezas et al. (2010) (26) | 18 June 2019 | n = 43 |

| Primary studies relevant to topic* | ||

| Arliani et al. (2014) (16) | 11 September 2019 | n = 16 |

| Arliani et al. (2016) (e14) | 11 September 2019 | n = 0 |

| Behzadi et al. (2017) (e15) | 11 September 2019 | n = 2 |

| Brouwer et al. (1981) (17) | 11 September 2019 | n = 4 |

| Elleuch et al. (2008) (18) | 11 September 2019 | n = 32 |

| Klünder et al. (1980) (19) | 11 September 2019 | n = 92 |

| Lau et al. (2000) (20) | 11 September 2019 | n = 144 |

| Lv et al. (2018) (21) | 11 September 2019 | n = 0 |

| Matiotti et al. (2017) (e22) | 11 September 2019 | n = 1 |

| Östenberg (2001) (22) | 11 September 2019 | n = 0 |

| Paxinos et al. (2016) (23) | 11 September 2019 | n = 6 |

| Söder et al. (2011) (e27) | 11 September 2019 | n = 15 |

| Volpi et al. (2019) (24) | 11 September 2019 | n = 0 |

* Excluded on grounds of recruitment method and/or response rate

eTable 3. Studies used for reference screening.

| Study | Date | Number of references in reference list |

| Studies included for analysis | ||

| Fernandes et al. (2018) (29) | 19 June 2019 | n = 32 |

| Iosifidis et al. (2015) (30) | 19 June 2019 | n = 41 |

| Kujala et al. (1994) (25) | 19 June 2019 | n = 21 |

| Kujala et al. (1995) (31) | 19 June 2019 | n = 30 |

| Roos et al. (1994) (1) | 19 June 2019 | n = 30 |

| Sandmark & Vingard (1999) (27) | 19 June 2019 | n = 16 |

| Thelin et al. (2006) (28) | 19 June 2019 | n = 19 |

| Tveit et al. (2012) (32) | 19 June 2019 | n = 34 |

| Vrezas et al. (2010) (26) | 19 June 2019 | n = 30 |

| Primary studies relevant to topic* | ||

| Arliani et al. (2014) (16) | 19 June 2019 | n = 20 |

| Arliani et al. (2016) (e14) | 19 August 2019 | n = 17 |

| Behzadi et al. (2017) (e15) | 26 June 2019 | n = 30 |

| Brouwer et al. (1981) (17) | 19 August 2019 | n = 17 |

| Elleuch et al. (2008) (18) | 26 June 2019 | n = 17 |

| Klünder et al. (1980) (19) | 19 August 2019 | n = 11 |

| Lau et al. (2000) (20) | 26 June 2019 | n = 38 |

| Lv et al. (2018) (21) | 19 August 2019 | n = 22 |

| Matiotti et al. (2017) (e22) | 19 August 2019 | n = 40 |

| Östenberg (2001) (22) | 19 August 2019 | n = 153 |

| Paxinos et al. (2016) (23) | 19 August 2019 | n = 76 |

| Söder et al. (2011) (e27) | 19 August 2019 | n = 24 |

| Volpi et al (2018) (24) | 19 August 2019 | n = 32 |

| Review articles relevant to topic | ||

| Ali Kahn et al. (2018) (e75) | 21 June 2019 | n = 45 |

| Andrade et al. (2016) (e76) | 19 June 2019 | n = 75 |

| Bolm-Audorff (2019) (e77) | 19 June 2019 | n = 85 |

| Driban et al. (2017) (7) | 19 June 2019 | n = 46 |

| Gouttebarge et al. (2015) (e78) | 19 June 2019 | n = 60 |

| Kuijt et al. (2012) (4) | 21 June 2019 | n = 50 |

| Lee & Chu (2012) (e79) | 21 June 2019 | n = 59 |

| Lefevre-Colau et al. (2016) (e80) | 21 June 2019 | n = 88 |

| Lequesne et al. (1997) (e81) | 21 June 2019 | n = 68 |

| Lohkamp et al. (2017) (e82) | 21 June 2019 | n = 67 |

| McAdams et al. (2010) (e83) | 26 June 2019 | n = 143 |

| McWilliams et al. (2011) (e84) | 26 June 2019 | n = 90 |

| Petrillo et al. (2018) (9) | 26 June 2019 | n = 83 |

| Richmond et al. (2013) (5) | 26 June 2019 | n = 73 |

| Salzmann et al. (2017) (e85) | 27 June 2019 | n = 108 |

| Spahn et al. (2015) (3) | 27 June 2019 | n = 85 |

| Tran et al. (2016) (e86) | 27 June 2019 | n = 68 |

| Vannini et al. (2016) (e87) | 27 June 2019 | n = 95 |

*Excluded on grounds of recruitment method and/or response rate

eTable 4. List of studies excluded after full-text screening.

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Anderson, 1986 (e13) | Study design: letter to editor |

| Arliani et al., 2014 (16) | Convenience sampling of comparison group |

| Arliani et al., 2016 (e14) | Outcome: MRI scan without diagnostic criteria for knee osteoarthritis |

| Behzadi et al., 2017 (e15) | Outcome: cartilage lesions, no reference to knee osteoarthritis |

| Ben Abdelghani et al. 2014 (e16) | Study design: abstract only |

| Brouwer et al. 1981 (17) | Convenience sampling of comparison group |

| Cooper et al., 2000 (e17) | Population: general population |

| Dahaghin et al., 2009 (e18) | Exposure: no differentiation between soccer and volleyball |

| Elleuch et al., 2008 (18) | No data on recruitment method for comparison group or for response rate in either exposure group or comparison group |

| Fernandes et al., 2016 (e19) | Study design: abstract only |

| Joensen et al., 2001 (e20) | Population: athletes in general, no differentiation among sports |

| Klünder et al., 1980 (19) | No data on recruitment method or response rate in comparison group |

| Lau et al., 2000 (20) | No data on response rate in either exposure group or comparison group |

| Li et al., 2007 (e21) | Population: athletes in general, no differentiation among sports |

| Lv et al., 2018 (21) | No data on recruitment method or response rate in either exposure group or comparison group |

| Matiotti et al., 2017 (e22) | Outcome: cartilage lesions, no reference to knee osteoarthritis |

| Östenberg, 2001 (22) | Convenience sampling of comparison group |

| Parekh et al., 2016 (e23) | Study design: abstract only |

| Paxinos et al., 2016 (23) | Convenience sampling of exposure group and comparison group |

| Regier et al., 2017 (e24) | Study design: abstract only |

| Roemer et al., 2015 (e25) | Population: athletes in general, no differentiation among sports (82% of cohort were soccer players) |

| Roemer et al., 2015 (e26) | Study design: abstract only |

| Söder et al., 2011 (e27) | Outcome: cartilage lesions, no reference to knee osteoarthritis |

| Spahn et al., 2013 (e28) | Population: athletes in general, no differentiation among sports |

| Volpi et al., 2019 (24) | No data on either recruitment method or response rate in comparison group |

| Whittaker et al., 2014 (e29) | Study design: abstract only |

| Whittaker et al., 2015 (e31) | Study design: abstract only |

| Whittaker et al., 2015 (e32) | Study design: abstract only |

| Whittaker et al., 2015 (e33) | Population: athletes in general, no differentiation among sports |

| Whittaker et al., 2016 (e30) | Study design: abstract only |

eTable 8. Soccer and the relative risk of knee osteoarthritis (Vrezas et al. [2010]), Seidler et al. [2008]).

|

Overall dose: amount of soccer ever played*1 (median M relates to median exposure in corresponding category among control persons) |

Cases | % | Controls | % | OR1 *2 | [95% CI] | OR2 *3 | [95% CI] |

| No soccer (M: 0 h) |

178 | 60.3 | 208 | 63.6 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| > 0 to < 1660 h (M: 1040 h) |

29 | 9.8 | 35 | 10.7 | 1.3 | [0.7; 2.3] | 1.1 | [0.5; 2.1] |

| 1660 to < 4000 h (M: 2652 h) |

41 | 13.9 | 34 | 10.4 | 1.9 | [1.0; 3.4] | 2.0 | [1.0; 3.8] |

| 4000 to < 7800 h (M: 5460 h) |

32 | 10.8 | 19 | 5.8 | 2.2 | [1.1; 4.4] | 2.2 | [1.0; 5.0] |

| ≥ 7800 h (M: 9984 h) |

15 | 5.1 | 16 | 4.9 | 1.2 | [0.5; 2.8] | 1.4 | [0.6; 3.6] |

*1 The overall dose of soccer ever played relates to both amateur and professional soccer. For the cases, the exposure up to the first diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis was included; for the controls, up to the time of questioning for the purposes of the study.

*2 OR 1: Odds ratio adjusted for age and study center

*3 OR 2: Odds ratio adjusted for age, study center, weight (BMI), jogging/athletics, cumulative kneeling, and cumulative lifting/carrying CI, Confidence interval; h, total hours of soccer; OR, odds ratio

Questions on the article from issue 4/2021:

The Risk of Knee Osteoarthritis in Professional Soccer Players

CME credit for this unit can be obtained via cme.aerzteblatt.de until 28 January 2022. Only one answer is possible per question.

Please choose the most appropriate answer.

Question 1

Which of the following is, to date, recognized as an occupational disease for professional soccer players?

Osteoarthritis secondary to knee joint trauma

Primary knee osteoarthritis after 10 years of professional sport

Secondary knee osteoarthritis after 10 years of professional sport

Primary knee osteoarthritis after 1 year of professional sport

No form of knee osteoarthritis

Question 2

In the Kellgren and Lawrence classification, what are the criteria for radiographic confirmation of knee osteoarthritis grade ≥ 2 in the tibiofemoral joint?

Osteophytes, tears of medial meniscus, joint space widening

Osteoclasts, joint space widening, and joint deformity

Osteoclasts, tears of medial meniscus, increased synovial fluid

Osteophytes, joint space widening, or joint deformity

Osteophytes, joint space narrowing, or joint deformity

Question 3

According to the meta-analysis carried out in this review, what is the odds ratio (OR) for objectively confirmed knee osteoarthritis in soccer players?

OR = 1.00

OR = 2.25

OR = 1.23

OR = 0.80

OR = 5.85

Question 4

In the studies included for analysis, what is the quality of the evidence, assessed using the GRADE system, regarding objectively confirmed knee osteoarthritis (research question 1)?

High quality

Low quality

Very low quality

Very high quality

Moderate quality

Question 5

To what extent is the risk of knee osteoarthritis in soccer players increased if only radiologically confirmed knee osteoarthritis is included for analysis?

Around fourfold

Around sixfold

Around eightfold

Around tenfold

Around twelvefold

Question 6

Which of the following activities is also considered as a stress factor that may also favor knee osteoarthritis?

Trampolining

Swimming training

Rowing

Running fast

Cycling

Question 7

How far do male soccer players run during the 90 min of a game?

Around 5 km

Around 2 km

Around 20 km

Around 11 km

Around 17 km

Question 8

A study that predominantly included amateur soccer players investigated the doubling dose of soccer for the development of knee osteoarthritis. How many hours represented the doubling dose in non-linear analysis of the continuous data?

7100 h

5900 h

9300 h

10 600 h

8500 h

Question 9

How high is the risk estimator for knee osteoarthritis in soccer players, excluding those with macrotrauma?

OR = 2.81

OR = 1.8

OR = 1.2

OR = 0.95

OR = 2.12

Question 10

A warm-up program developed for prevention of knee joint injuries in professional and amateur soccer has been shown to be effective in randomized controlled trials. What is it called?

UEFA 11+

DFB 11+

SOCCER 11+

FIFA 11+

KNEE 11+

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare

Acknowledgment

This study was conducted on behalf of the German Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (BMAS) with expert assistance from the Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (BAuA).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Roos H, Lindberg H, Gardsell P, Lohmander LS, Wingstrand H. The prevalence of gonarthrosis and its relation to meniscectomy in former soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:219–222. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larsen E, Jensen PK, Jensen PR. Long-term outcome of knee and ankle injuries in elite football. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1999;9:285–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1999.tb00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spahn G, Grosser V, Schiltenwolf M, Schröter F, Grifka J. Fußballsport als Risikofaktor für nicht unfallbedingte Gonarthrose: Ergebnisse eines systematischen Review mit Metaanalyse. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 2015;29:27–39. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1385731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuijt MT, Inklaar H, Gouttebarge V, Frings-Dresen MH. Knee and ankle osteoarthritis in former elite soccer players: a systematic review of the recent literature. J Sci Med Sport. 2012;15:480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]