Abstract

Aims

Neurogranin (NRGN) is a postsynaptic protein kinase substrate that binds calmodulin in the absence of calcium. Recent studies suggest that NRGN is involved in neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, ADHD, and Alzheimer's disease. Previous behavioral studies of Nrgn knockout (Nrgn KO) mice identified hyperactivity, deficits in spatial learning, impaired sociability, and decreased prepulse inhibition, which suggest that these mice recapitulate some symptoms of neuropsychiatric disorders. To further validate Nrgn KO mice as a model of neuropsychiatric disorders, we assessed multiple domains of behavioral phenotypes in Nrgn KO mice using a comprehensive behavioral test battery including tests of homecage locomotor activity and nesting behavior.

Methods

Adult Nrgn KO mice (28‐54 weeks old) were subjected to a battery of comprehensive behavioral tests, which examined general health, nesting behavior, neurological characteristics, motor function, pain sensitivity, locomotor activity, anxiety‐like behavior, social behavior, sensorimotor gating, depression‐like behavior, and working memory.

Results

The Nrgn KO mice displayed a pronounced decrease in nesting behavior, impaired motor function, and elevated pain sensitivity. While the Nrgn KO mice showed increased locomotor activity in the open field test, these mice did not show hyperactivity in a familiar environment as measured in the homecage locomotor activity test. The Nrgn KO mice exhibited a decreased number of transitions in the light‐dark transition test and decreased stay time in the center of the open field test, which is consistent with previous reports of increased anxiety‐like behavior. Interestingly, however, these mice stayed on open arms significantly longer than wild‐type mice in the elevated plus maze. Consistent with previous studies, the mutant mice exhibited decreased prepulse inhibition, impaired working memory, and decreased sociability.

Conclusions

In the current study, we identified behavioral phenotypes of Nrgn KO mice that mimic some of the typical symptoms of neuropsychiatric diseases, including impaired executive function, motor dysfunction, and altered anxiety. Most behavioral phenotypes that had been previously identified, such as hyperlocomotor activity, impaired sociability, tendency for working memory deficiency, and altered sensorimotor gating, were reproduced in the present study. Collectively, the behavioral phenotypes of Nrgn KO mice detected in the present study indicate that Nrgn KO mice are a valuable animal model that recapitulates a variety of symptoms of neuropsychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, ADHD, and Alzheimer's disease.

Keywords: ADHD, Alzheimer's disease, animal model, neurogranin, schizophrenia

We found that Neurogranin knockout mice exhibit decreased nesting behavior, selective increases in locomotor activity in a novel environment, and paradoxically increased open arm exploration. Considering the behavioral phenotypes that had been previously identified, we propose that Neurogranin KO mice are a valuable animal model that recapitulates a variety of symptoms of neuropsychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, ADHD, and Alzheimer's disease.

1.

Neurogranin (NRGN) is a neuron‐specific protein that regulates calmodulin availability. Increases in postsynaptic calcium result in the release of calmodulin from neurogranin and participates in the protein kinase C signaling pathway. 1 , 2 A genome‐wide association study identified a significant association with schizophrenia at a locus near the NRGN gene in European populations. 3 Children with Jacobsen syndrome, which involves attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), have a deletion in the NRGN gene. 4 , 5 In patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD), NRGN protein levels are decreased in the brain tissue 6 , 7 and increased in the cerebrospinal fluid, 8 , 9 compared with healthy controls. Elevated NRGN peptide levels in the cerebrospinal fluid, which may reflect decreased NRGN protein levels in the brain, 10 have also been reported in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 These findings imply that NRGN might be involved in the pathophysiology and pathogenesis of various neuropsychiatric disorders. Since the generation of Nrgn knockout (Nrgn KO) mice, 1 several behavioral studies have been carried out on these mice, and hyperactivity, 15 deficits in spatial learning, 16 , 17 impaired sociability, 15 and decreased prepulse inhibition 18 were identified, suggesting that these mice recapitulate some symptoms of neuropsychiatric disorders. To further validate Nrgn KO mice as a model of certain neuropsychiatric diseases, we assessed various behavioral domains in aged Nrgn KO mice using a comprehensive behavioral test battery 19 , 20 , 21 (summary of the results and ages of the mice are available in the supplementary table).

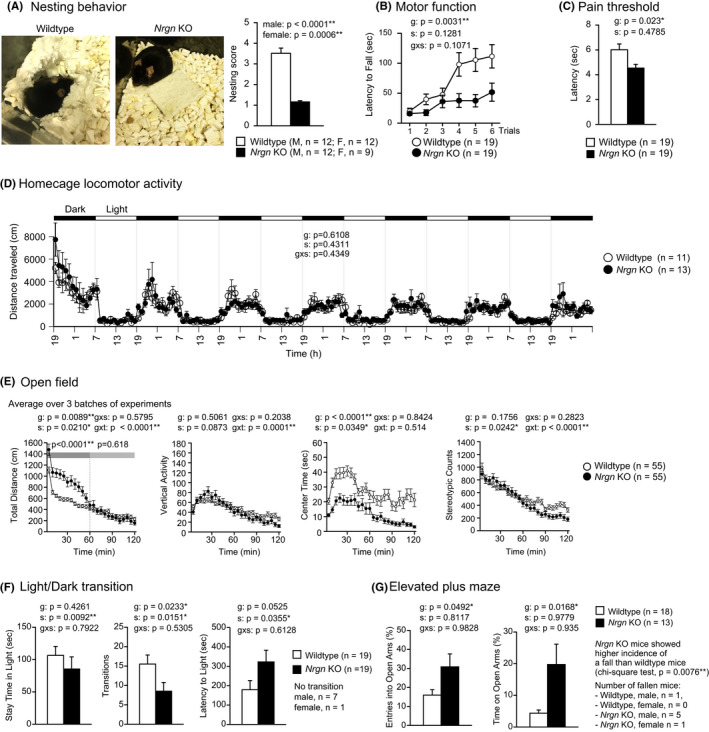

We found that Nrgn KO mice exhibited a clear decrease in nesting behavior compared with that in wild‐type mice (Figure 1A; male, P < 0.0001; female, P = 0.0006), which may be analogous to the impaired executive function 22 , 23 seen in patients with schizophrenia, 24 , 25 ADHD, 26 , 27 and AD. 28 In the rotarod test, the mutant mice exhibited a shorter latency to fall than that of the control mice (Figure 1B; P = 0.0031), which may be analogous to the motor dysfunctions in schizophrenia, ADHD, and AD. 25 , 29 , 30 The Nrgn KO mice showed a slight but significant decrease in the latency of the paw response in the hot plate test (Figure 1C; P = 0.023).

FIGURE 1.

Decreased nesting behavior, selective increase of locomotor activity in a novel environment, and paradoxically increased open arm exploration in Nrgn KO mice (A) Nesting behavior. (B) Motor function. (C) Latency of the first fore or hind paw response in the hot plate test. (D) Locomotor activity in homecage. (E) Locomotor activity, vertical activity, time stayed in the central area, and number of stereotypic behaviors in the open field test. (F) Time spent in the light compartment, number of light‐dark transitions, and latency to enter the light compartment in the light‐dark transition test. (G) Percentage entries into open arms of the total number of entries to all arms and percentage of time on open arms of the total duration of the experiment in the elevated plus maze test. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ANOVA (in A, C, F, and G) or repeated measures ANOVA (in B, D, E) were used for the statistical analysis. g: genotype effect; s: sex effect; g × s: genotype and sex interaction; g × t: genotype and time interaction. For data where a significant sex effect was observed (body weight, body temperature; indexes in light/dark transition test, T‐maze test, and open field test), the male and female data are shown separately in the supplementary figures. Significant interactions between genotype and sex effects, which suggest the sex dependence of the expression of the genotype effect, were not detected in any of the tests (see supplementary table for the summary of all the results) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In the open field test, mutants were significantly more active than controls in the first 60 minutes of the test (Figure 1E; whole period, genotype effect, P = 0.0089; the first 60 minutes, P < 0.0001; the last 60 minutes, P = 0.618; time × genotype interaction, P < 0.0001), suggesting that the expression of hyperlocomotor activity in Nrgn KO mice was limited to novel environments. This finding is further supported by the results from the homecage locomotor activity test, which did not detect a significant genotype effect on distance traveled (Figure 1D; P = 0.6108), indicating that the hyperactivity of Nrgn KO mice disappeared in a familiar environment. Concordantly, the results from the open field test and homecage locomotor activity test indicate that Nrgn KO mice show increased locomotor activity in response to a novel but not to a familiar environment. Increased locomotor activity is also a common characteristic seen in other schizophrenia 23 and AD 31 mouse models.

In the open field test, the Nrgn KO mice spent significantly less time in the center of the field during the 2‐hours session than the control mice (Figure 1E; P < 0.0001), which is generally interpreted as increased anxiety‐like behavior. In the light‐dark transition test, Nrgn KO mice tended to stay in the light compartment for less time than the control mice, but the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 1F, left panel; P = 0.4261). In the same test, Nrgn KO mice also exhibited a decreased number of transitions between light‐dark compartments (Figure 1F, middle panel; P = 0.0233) and a tendency of increased latency to enter the light chamber (Figure 1F, right panel; P = 0.0525), suggesting increased anxiety‐like behavior in the mutant mice, which has also been reported previously. 16 In contrast, in the elevated plus maze, Nrgn KO mice showed significantly increased entries into open arms and time on open arms (Figure 1G; P = 0.0492 and P = 0.0168, respectively). The paradoxical changes in behavioral measures for anxiety‐like behavior in Nrgn KO mice may be attributed to the increased reactivity to novelty that we found in the present study, panic‐like behavior, 23 or elevated impulsivity. 32 The blood corticosterone concentration in the Nrgn KO mice after the elevated plus maze was not significantly different from that in the wild‐type mice (Figure S2C, P = 0.5517). The Nrgn KO mice also showed a significantly higher incidence of falling from the maze than the control mice (Figure 1G; P = 0.0076; chi‐square test). All of the Nrgn KO mice that fell stepped off the open arms backwards rather than forwards and clung to the arms to prevent the fall, suggesting that the increased incidence of falls in mutant mice is likely accidental and due to impaired motor function, as seen in the rotarod test. These behavioral phenotypes may recapitulate the altered anxiety states seen in patients with neuropsychiatric disorders. 33 , 34

We also reproduced behavioral phenotypes in the mutant mice that have been reported (available as supplementary materials). The Nrgn KO mice exhibited decreased prepulse inhibition 18 (Figure S5; prepulse inhibition [%]; P = 0.0315), decreased immobility 15 in the Porsolt forced swim test (Figure S5; immobility [%] on day 2; P = 0.067), and a tendency of decreased sociability and social preference in male mice 15 (Figure S4, F, and G; time spent around a stranger cage [ratio]; P = 0.2069 and P = 0.3295, respectively). Female mutant mice showed a significantly decreased ratio of time spent around stranger cage both in sociability and social preference tests, while sexual attraction of the male stranger mice might have confounded their social behaviors (Figure S4, H and I; time spent around a stranger cage [ratio]; P = 0.0054 and P = 0.0145, respectively). Consistent with the tendency of impaired working memory in the radial‐arm maze reported previously, 17 in the present study, Nrgn KO mice showed a statistically significant decrease in correct responses (Figure S6; correct responses [%]; P = 0.0062) as measured by the T‐maze spontaneous alternation test.

Overall, Nrgn KO mice recapitulate a variety of the typical symptoms of schizophrenia, ADHD, and AD, including impaired executive functions, motor dysfunction, increased activity in response to novelty, and altered anxiety levels, which we found in the present study. We also reproduced most of the behavioral phenotypes that were previously reported. Until recently, Nrgn KO mice have been suggested to be an animal model of schizophrenia and Jacobsen's syndrome with ADHD symptoms, 15 as these mice show hyperactivity, 15 altered anxiety‐like behavior, 16 decreased sociability, 15 impaired reference memory, 15 , 16 , 17 and impaired sensorimotor gating. 18 Behavioral phenotypes of commonly used AD model mice such as decreased nesting behavior, 31 , 35 , 36 , 37 hyperactivity, 31 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 impaired sociability, 35 impaired working/reference memory, 31 , 35 , 38 , 39 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 and abnormal sensorimotor gating 46 , 47 overlap with those of Nrgn KO mice, which suggests the potential of Nrgn KO as a model of AD. Considering this, a decrease in NRGN in the brains of AD model mice 48 and AD patients 6 , 7 may potentially explain some of the phenotypes or symptoms, respectively. Taken together, the behavioral phenotypes of Nrgn KO mice indicate that Nrgn KO mice might be a valuable animal model for further investigation of the pathophysiology and pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, ADHD, and AD.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest with regard to the present article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RN wrote the manuscript. SH, FLH, and TM helped draft the manuscript. SH, TF, and RN performed the behavioral tests and analyzed the data. TM supervised all aspects of the present study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

APPROVAL OF THE RESEARCH PROTOCOL BY AN INSTITUTIONAL REVIEWER BOARD

n/a.

INFORMED CONSENT

n/a.

REGISTRY AND THE REGISTRATION NO. OF THE STUDY/TRIAL

n/a.

ANIMAL STUDIES

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Fujita Health University.

Supporting information

Fig S1‐6

Table S1

Method S1

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kuo‐Ping Huang for providing us with the Nrgn KO mice, Giovanni Sala for invaluable comments on statistics, Hirotaka Shoji for technical instructions on corticosterone quantification, Hideo Hagihara for advice on the discussion part, and Hisatsugu Koshimizu for general comments on the present report. We also thank Wakako Hasegawa, Yumiko Mobayashi, Misako Murai, Tamaki Murakami, Miwa Takeuchi, Yoko Kagami, Harumi Mitsuya, and Yoshihiro Takamiya for their technical assistance.

Nakajima R, Hattori S, Funasaka T, Huang FL, Miyakawa T. Decreased nesting behavior, selective increases in locomotor activity in a novel environment, and paradoxically increased open arm exploration in Neurogranin knockout mice. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep.2021;41:111–116. 10.1002/npr2.12150

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in “Mouse Phenotype Database” at [http://www.mouse‐phenotype.org/], reference number. 49

REFERENCES

- 1. Pak JH, Huang FL, Li J, Balschun D, Reymann KG, Chiang C, et al. Involvement of neurogranin in the modulation of calcium/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II, synaptic plasticity, and spatial learning: a study with knockout mice. PNAS. 2000;97(21):11232–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Xia Z, Storm DR. The role of calmodulin as a signal integrator for synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(4):267–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stefansson H, Ophoff RA, Steinberg S, Andreassen OA, Cichon S, Rujescu D, et al. Common variants conferring risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2009;460(7256):744–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coldren CD, Lai Z, Shragg P, Rossi E, Glidewell SC, Zuffardi O, et al. Chromosomal microarray mapping suggests a role for BSX and Neurogranin in neurocognitive and behavioral defects in the 11q terminal deletion disorder (Jacobsen syndrome). Neurogenetics. 2009;10(2):89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grossfeld PD, Mattina T, Lai Z, Favier R, Jones KL, Cotter F, et al. The 11q terminal deletion disorder: a prospective study of 110 cases. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2004;129A(1):51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davidsson P, Blennow K. Neurochemical dissection of synaptic pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 1998;10(1):11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reddy PH, Mani G, Park BS, Jacques J, Murdoch G, Whetsell W, et al. Differential loss of synaptic proteins in Alzheimer's disease: implications for synaptic dysfunction. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7(2):103–17; discussion 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thorsell A, Bjerke M, Gobom J, Brunhage E, Vanmechelen E, Andreasen N, et al. Neurogranin in cerebrospinal fluid as a marker of synaptic degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 2010;1362:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fyfe I. Alzheimer disease: neurogranin in the CSF signals early Alzheimer disease and predicts disease progression. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(11):609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kvartsberg H, Lashley T, Murray CE, Brinkmalm G, Cullen NC, Höglund K, et al. The intact postsynaptic protein neurogranin is reduced in brain tissue from patients with familial and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;137(1):89–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Portelius E, Zetterberg H, Skillbäck T, Törnqvist U, Andreasson U, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neurogranin: relation to cognition and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2015;138(11):3373–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Headley A, De Leon‐Benedetti A, Dong C, Levin B, Loewenstein D, Camargo C, et al. Neurogranin as a predictor of memory and executive function decline in MCI patients. Neurology. 2018;90(10):e887–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kvartsberg H, Duits FH, Ingelsson M, Andreasen N, Öhrfelt A, Andersson K, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of the synaptic protein neurogranin correlates with cognitive decline in prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(10):1180–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mavroudis IA, Petridis F, Chatzikonstantinou S, Kazis D. A meta‐analysis on CSF neurogranin levels for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;32(9):1639–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang FL, Huang K‐P. Methylphenidate improves the behavioral and cognitive deficits of neurogranin knockout mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2012;11(7):794–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miyakawa T, Yared E, Pak JH, Huang FL, Huang KP, Crawley JN. Neurogranin null mutant mice display performance deficits on spatial learning tasks with anxiety related components. Hippocampus. 2001;11(6):763–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang FL, Huang K‐P, Wu J, Boucheron C. Environmental enrichment enhances neurogranin expression and hippocampal learning and memory but fails to rescue the impairments of neurogranin null mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26(23):6230–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sullivan JM, Grant CA, Reker AN, Nahar L, Goeders NE, Nam HW. Neurogranin regulates sensorimotor gating through cortico‐striatal circuitry. Neuropharmacology. 2019;150:91–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yamasaki N, Maekawa M, Kobayashi K, Kajii Y, Maeda J, Soma M, et al. Alpha‐CaMKII deficiency causes immature dentate gyrus, a novel candidate endophenotype of psychiatric disorders. Molecular Brain. 2008;1(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nakajima R, Takao K, Huang S‐M, Takano J, Iwata N, Miyakawa T, et al. Comprehensive behavioral phenotyping of calpastatin‐knockout mice. Mol Brain. 2008;1(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nakajima R, Takao K, Hattori S, Shoji H, Komiyama NH, Grant SGN, et al. Comprehensive behavioral analysis of heterozygous Syngap1 knockout mice. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2019;39(3):223–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Filali M, Lalonde R. Age‐related cognitive decline and nesting behavior in an APPswe/PS1 bigenic model of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 2009;1292:93–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miyakawa T, Leiter LM, Gerber DJ, Gainetdinov RR, Sotnikova TD, Zeng H, et al. Conditional calcineurin knockout mice exhibit multiple abnormal behaviors related to schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(15):8987–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Orellana G, Slachevsky A. Executive functioning in schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hidese S, Matsuo J, Ishida I, Hiraishi M, Teraishi T, Ota M, et al. Relationship of handgrip strength and body mass index with cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martel M, Nikolas M, Nigg JT. Executive Function in Adolescents With ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(11):1437–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Doyle AE, Seidman LJ, Wilens TE, Ferrero F, et al. Impact of executive function deficits and attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on academic outcomes in children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(5):757–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guarino A, Favieri F, Boncompagni I, Agostini F, Cantone M, Casagrande M. Executive functions in Alzheimer disease: a systematic review. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;10:437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. For the NILVAD Study Group , Dyer AH, Lawlor B, Kennelly SP. Gait speed, cognition and falls in people living with mild‐to‐moderate Alzheimer disease: data from NILVAD. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stray L, Stray T, Iversen S, Ruud A, Ellertsen B, Tønnessen F. The Motor Function Neurological Assessment (MFNU) as an indicator of motor function problems in boys with ADHD. Behav Brain Funct. 2009;5(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lippi SLP, Smith ML, Flinn JM. A novel hAPP/htau mouse model of Alzheimer's disease: inclusion of APP with Tau exacerbates behavioral deficits and zinc administration heightens tangle pathology. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Isles AR. Common genetic effects on variation in impulsivity and activity in mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24(30):6733–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ferretti L, McCurry SM, Logsdon R, Gibbons L, Teri L. Anxiety and Alzheimer's disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2001;14(1):52–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Turnbull G, Bebbington P. Anxiety and the schizophrenic process: clinical and epidemiological evidence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36(5):235–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Samaey C, Schreurs A, Stroobants S, Balschun D. Early cognitive and behavioral deficits in mouse models for Tauopathy and Alzheimer's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Orta‐Salazar E, Feria‐Velasco A, Medina‐Aguirre GI, Díaz‐Cintra S. Morphological analysis of the hippocampal region associated with an innate behaviour task in the transgenic mouse model (3xTg‐AD) for Alzheimer disease. Neurología (English Edition). 2013;28(8):497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Deacon RMJ, Cholerton LL, Talbot K, Nair‐Roberts RG, Sanderson DJ, Romberg C, et al. Age‐dependent and ‐independent behavioral deficits in Tg2576 mice. Behav Brain Res. 2008;189(1):126–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mucke L, Masliah E, Yu G‐Q, Mallory M, Rockenstein EM, Tatsuno G, et al. High‐level neuronal expression of Aβ1–42 in wild‐type human amyloid protein precursor transgenic mice: synaptotoxicity without plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2000;20(11):4050–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wright AL, Zinn R, Hohensinn B, Konen LM, Beynon SB, Tan RP, et al. Neuroinflammation and neuronal loss precede Aβ plaque deposition in the hAPP‐J20 mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Guillemin GJ, editor. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e59586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ramsden M, Kotilinek L, Forster C, Paulson J, McGowan E, SantaCruz K, et al. Age‐dependent neurofibrillary tangle formation, neuron loss, and memory impairment in a mouse model of human tauopathy (P301L). J Neurosci. 2005;25(46):10637–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chabrier MA, Cheng D, Castello NA, Green KN, LaFerla FM. Synergistic effects of amyloid‐beta and wild‐type human tau on dendritic spine loss in a floxed double transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;64:107–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hunsberger HC, Rudy CC, Batten SR, Gerhardt GA, Reed MN. P301L Tau expression affects glutamate release and clearance in the hippocampal trisynaptic pathway. J Neurochem. 2015;132(2):169–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stover KR, Campbell MA, Van Winssen CM, Brown RE. Early detection of cognitive deficits in the 3xTg‐AD mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Behav Brain Res. 2015;289:29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pérez M, Ribe E, Rubio A, Lim F, Morán MA, Ramos PG, et al. Characterization of a double (amyloid precursor protein‐tau) transgenic: tau phosphorylation and aggregation. Neuroscience. 2005;130(2):339–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ribé EM, Pérez M, Puig B, Gich I, Lim F, Cuadrado M, et al. Accelerated amyloid deposition, neurofibrillary degeneration and neuronal loss in double mutant APP/tau transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20(3):814–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Story D, Chan E, Munro N, Rossignol J, Dunbar GL. Latency to startle is increased in the 5xFAD mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Behav Brain Res. 2019;01(359):823–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sichler ME, Löw MJ, Schleicher EM, Bayer TA, Bouter Y. Reduced acoustic startle response and prepulse inhibition in the Tg4‐42 model of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimer's Dis Rep. 2019;3(1):269–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jeon SG, Kang M, Kim Y‐S, Kim D‐H, Nam DW, Song EJ, et al. Intrahippocampal injection of a lentiviral vector expressing neurogranin enhances cognitive function in 5XFAD mice. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50(3):e461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nakajima R, Hattori S, Funasaka T, Miyakawa T. 2020; Nrgn; Mouse Phenotype Database; http://www.mouse‐phenotype.org/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1‐6

Table S1

Method S1

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in “Mouse Phenotype Database” at [http://www.mouse‐phenotype.org/], reference number. 49