Abstract

Background

Individuals infected by the novel coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐2) have experienced different psychiatric manifestations during the period of infectivity and post‐COVID‐19 infection. Fatigue and anhedonia are among the frequently reported manifestations after recovery from this novel viral pandemic, leading to early evaluation of those patients and proper management of their complaints which have a drastic burden on different domains of life. Also, the period after recovery might have an effect on the severity of these two psychiatric presentations.

Aim of the work

This cross‐sectional observational study aimed to investigate the occurrence of post‐COVID‐19 fatigue and anhedonia and whether the duration after 2 consecutive PCR‐negative tests has an implication on the severity of the above‐mentioned psychiatric manifestations.

Methods

Socio‐demographic characteristics of 200 post‐COVID‐19 patients were collected, and also, the self‐assessment anhedonia scale was used to evaluate the degree of anhedonia. Fatigue assessment scale used to investigate this domain. The study targeted to find a possible correlation between the period after recovery and the other variables including anhedonia and fatigue.

Results

The study revealed high scores of different subtypes of self‐assessment anhedonia scale (including total intensity, total frequency, and total changes scores) in the studied group, also high score of fatigue assessment scale in those patients. Positive statistically significant correlation between anhedonia and fatigue in post‐COVID‐19 group, also negative statistically significant correlation between duration after recovery and the other 2 variables(anhedonia and fatigue) in the examined patients.

Conclusion

Post‐COVID‐19 fatigue and anhedonia were prevalent and commonly reported in the post‐COVID‐19 period, also the duration after 2 consecutive negative PCR tests has an implication on the severity rating scale of both anhedonia and fatigue. These findings directed our attention to those reported manifestations which affected the socio‐occupational functioning of the individuals during this whole world pandemic.

Keywords: anhedonia, COVID‐19, fatigue, pandemic, post‐recovery

The post COVID‐19 manifestations including anhedonia and fatigue are very commonly reported in the duration after recovery ,they may affect the different domains of life,also these post COVID‐19 manifestions are negatively associated to the duration.

1. INTRODUCTION

Rothan and Byrareddy 1 noted COVID‐19 is a viral infection caused by SARS‐CoV‐2 that principally affects the pulmonology system with primary manifestations like fever, cough, and shortness of breath.

World Health Organization 2 declared until the end of May 2020, there were over 5.5 million confirmed cases of people who have been infected with COVID‐19 worldwide and over 353 000 death cases.

Xiang et al 9 highlighted infection symptoms including fever, hypoxia and dry cough, shortness of breath, and adverse effects of treatment like corticosteroids induced insomnia might lead to anxiety worsening and mental distress .

Rio and Malani 3 highlighted that fatigue is commonly seen in COVID‐19 epidemic, and also, the patients still have high levels of fatigue and anhedonia after recovery from infection.

Treadway and Zald 4 defined anhedonia as persistently and severely decreased interest or pleasure in most daily activities. It is also known as a decrement of pleasurable activities, or a loss of interest to action in order to get pleasure.

Brodaty et al 5 found that anhedonia and fatigue can also occur in patients without psychiatric disorders like in systemic illnesses ,viral infections, or chronic fatigue syndrome. Similarly, apathy and anhedonia were recognized to occur not only in the context of clinical diagnoses but also, in milder forms, in the general population, particularly with aging.

Brooks et al 6 noted the effect of quarantine on cases of COVID‐19 infection leading to development of psychological and cognitive manifestations of post‐COVID‐19 depressive symptoms, stress, anxiety, chronic fatigue, and anhedonic state.

Hives et al 7 evidenced pro‐inflammatory components like cytokines such as interferon gamma, and interleukin 7, which supposed to compromise the neurological regulation of the “Glymphatic System” as observed in chronic fatigue syndrome.

Perrin et al 8 found that many cases of COVID‐19 developed a drastic post‐viral syndrome named “post‐COVID‐19 Syndrome”—a persistent condition of chronic fatigue, disturbed sleep/wake cycle, neuro‐cognitive implications, and progressive anhedonia.

2. METHODS

2.1. Settings

This study was conducted in Hayat National Hospital, Psychiatry Department, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The study was conducted from 10th of July to 28th of July 2020.

2.2. Study design

This current methodological design is a cross‐sectional observational study with a longitudinal component for evaluation of prevalence of anhedonia and fatigue in post‐COVID‐19 patients and the effect of duration after recovery from infection on the above‐mentioned domains.

2.3. Study population

A convenience sample of 200 patients of COVID‐19 after 2 consecutive negative PCR tests who attended for pulmonology clinic for follow‐up and psychiatric department for assessment.

2.4. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All patients of both sexes, with age range from 18‐60 years, can read and write to complete the scales, 2 negative PCR tests for COVID‐19, those have major psychiatric disorders, other general medical conditions like chronic diseases that might be manifested by fatigue or under the effect of psychotropic medications were excluded from the study.

2.5. The self‐assessment anhedonia scale (SAAS)

This scale was developed by Olivares et al 10 The scale included 27 items each to be replied on three independent semantic differential lines: 1. Intensity (a lot—not at all), 2. Frequency (always—never), and 3. Change (the same as before—less than before). Each line was 10 cm long and could be scored on a Likert‐type scale ranging from 0 to 10. The higher the score, the greater the anhedonia. To avoid halo effects, the second line polarities were reversed.

2.6. Fatigue assessment scale(FAS)

This scale was originated by Michielsen et al 11 The FAS is a 10‐item scale evaluating symptoms of fatigue. Each item of the FAS is answered using a five‐point, Likert‐type scale ranging from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“always”). Items 4 and 10 are reverse‐scored. Total scores can range from 10, indicating the lowest level of fatigue, to 50, denoting the highest.

2.7. Ethical consideration

IRB approval was taken to conduct this study.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants after full explanation of the aim of the study.

Patients were confirmed about the confidentiality of their data collected and that they were able to withhold from the study at any time without giving reasons.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package of Social Science (SPSS) program for Windows (Standard version 24). The normality of data was first tested with one‐sample Kolmogorov‐Smirnov test. Qualitative data were described using number and percent. Continuous variables were presented as mean (SD) and two groups were compared by t test while ANOVA test was used to compare more than 2 group. The results were considered significant when (P ≤ .05).

Pearson correlation was used to correlate continuous data.

3. RESULTS

Table 1 shows socio‐demographic data and clinical characteristics: The mean age of the participants was 36.58(SD ± 9.85) years. The sample composed of 114 male patients (57%) and 86 female patients (43%), 135(67.5%) were married while single were 65 (32.5%). 81 (40.5%) had an University degree those with secondary school were 79 (39.5%) and with intermediate school were 40 (20%), 103 (51.5%) of the sample were employed and 97 (48.5%) were unemployed. 126 (63%) were from urban areas. Smoker participants were 132 (66%).The mean duration after recovery from COVID‐19 was 11.83(SD ± 3.77).

TABLE 1.

Socio‐demographic data among the studied group

| Socio‐demographic data | The studied group (n = 200) |

|---|---|

| Age/ years | |

| Mean ± SD | 36.58 ± 9.85 |

| ≤30 y | 65 (32.5%) |

| 30‐40 y | 61 (30.5%) |

| 40‐50 y | 54 (27%) |

| ≥ 50 y | 20 (10%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 114 (57%) |

| Female | 86 (43%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 135 (67.5%) |

| Single | 65 (32.5%) |

| Education | |

| Preparatory | 40 (20%) |

| Secondary | 79 (39.5%) |

| University | 81 (40.5%) |

| Occupation | |

| Worker | 103 (51.5%) |

| Non worker | 97 (48.5%) |

| Residence | |

| Urban | 126 (63%) |

| Rural | 74 (37%) |

| Smoking | |

| Smokers | 132 (66%) |

| Non smokers | 68 (34%) |

| Mean duration after recovery from COVID‐19 | |

| Mean ± SD | 11.83 ± 3.77 |

Table 2 shows results distribution of self‐assessment anhedonia scale domains in which mean total intensity score was 224.02 (SD ± 20.72), mean total frequency score was 229.89 (SD ± 18.80), mean total change score was 234.87(SD ± 16.58), and mean total anhedonia score was 688.41(SD ± 52.98). Mean fatigue score was 40.81(SD ± 5.75).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of self‐assessment anhedonia scale and fatigue assessment scale

| The studied group (n = 200) | |

|---|---|

| Mean total intensity score | 224.02 ± 20.72 |

| Mean total frequency score | 229.89 ± 18.80 |

| Mean total change score | 234.87 ± 16.58 |

| Mean total anhedonia score | 688.41 ± 52.98 |

| Mean Fatigue assessment scale score | 40.81 ± 5.75 |

Table 3 shows no statistically significant correlation between items of socio‐demographic data and mean total anhedonia score.

TABLE 3.

Association between socio‐demographic data and total anhedonia score

| Socio‐demographic data | Total | Total ANHEDONIA score | Test of significance | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/years | ||||

| <30 y | 65 | 684.45 ± 51.31 | F = 0.459 | .711 |

| 30‐40 y | 61 | 686.44 ± 50.46 | ||

| 40‐50 y | 54 | 695.41 ± 57.09 | ||

| >50 y | 20 | 688.45 ± 56.57 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 114 | 692.17 ± 53.17 | t = 1.16 | .249 |

| Female | 86 | 683.43 ± 52.63 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 135 | 689.15 ± 55.67 | t = 0.284 | .777 |

| Single | 65 | 686.87 ± 47.29 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 40 | 677.35 ± 51.88 | F = 1.37 | .257 |

| Secondary | 79 | 694.30 ± 47.26 | ||

| University | 81 | 688.13 ± 58.29 | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| Worker | 103 | 688.75 ± 51.43 | t = 0.094 | .925 |

| Non worker | 97 | 688.05 ± 54.85 | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 126 | 689.52 ± 55.64 | t = 0.385 | .700 |

| Rural | 74 | 686.52 ± 48.42 | ||

| Smoking | ||||

| Smokers | 132 | 687.15 ± 53.14 | t = 0.469 | .640 |

| Non smokers | 68 | 690.86 ± 52.98 | ||

F: ANOVA test, t: Student's t test.

Table 4 showed a statistically significant positive correlation between gender of the patient and fatigue assessment scale (t = 1.97, P value .05*).

TABLE 4.

Association between socio‐demographic data and fatigue assessment scale

| Socio‐demographic data | Total | Fatigue assessment scale | Test of significance | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/ years | ||||

| <30 y | 65 | 40.80 ± 5.39 | F = 0.378 | .769 |

| 30‐40 y | 61 | 40.39 ± 6.21 | ||

| 40‐50 y | 54 | 41.46 ± 5.94 | ||

| >50 y | 20 | 40.35 ± 5.10 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 114 | 41.50 ± 5.64 | t = 1.97 | .05* |

| Female | 86 | 39.89 ± 5.81 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 135 | 41.18 ± 5.72 | t = 1.33 | .184 |

| Single | 65 | 40.03 ± 5.77 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Preparatory | 40 | 39.52 ± 5.49 | F = 1.29 | .276 |

| Secondary | 79 | 41.26 ± 5.45 | ||

| University | 81 | 41.00 ± 6.13 | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| Worker | 103 | 41.24 ± 5.64 | t = 1.09 | .274 |

| Non worker | 97 | 40.35 ± 5.85 | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 126 | 40.66 ± 5.91 | t = 0.484 | .629 |

| Rural | 74 | 41.07 ± 5.49 | ||

| Smoking | ||||

| Smokers | 132 | 41.36 ± 5.56 | t = 1.91 | .058 |

| Non smokers | 68 | 39.73 ± 6.01 | ||

F: ANOVA test, t: Student.

Table 5 revealed a statistically significant negative correlation between mean duration after recovery from COVID‐19 and different domains of self‐assessment anhedonia scale and fatigue assessment scale. Also, there was a statistically significant positive correlation between domains of self‐assessment anhedonia scale (SAAS) and fatigue assessment scale (FAS).

TABLE 5.

Association between days after recovery from COVID‐19, fatigue assessment scale, and self‐assessment anhedonia scale

| Days after recovery from COVID‐19 | Fatigue assessment scale | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | r | P | |

| Mean total intensity score | −.760 | ≤.001* | .728 | ≤.001* |

| Mean total frequency score | −.631 | ≤.001* | .601 | ≤.001* |

| Mean total change score | −.559 | ≤.001* | .515 | ≤.001* |

| Mean total anhedonia score | −.711 | ≤.001* | .670 | ≤.001* |

| Mean fatigue assessment scale score | −.900 | ≤.001* | ‐ | ‐ |

The use of * means that this variable is statistically significant.

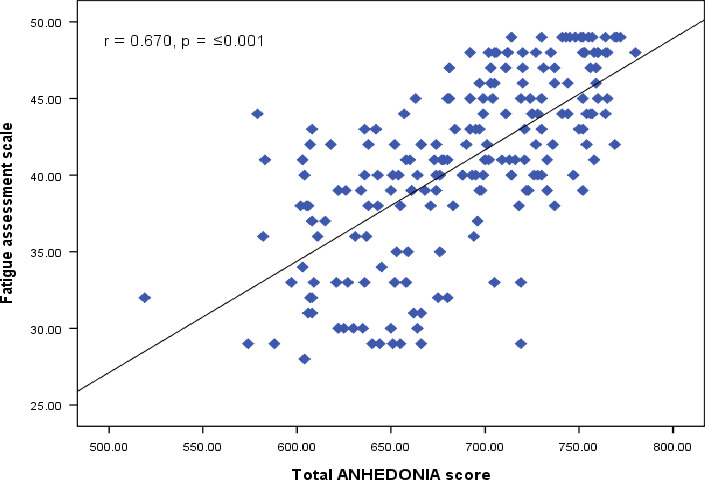

Figure 1 illustrated positive association between mean total anhedonia score and mean fatigue assessment scale which means both anhedonia and fatigue were commonly associated in the post‐COVID‐19 recovery period.

FIGURE 1.

illustrated the association between mean fatigue score and mean anhedonia score [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to assess the prevalence of post‐COVID‐19 fatigue and anhedonia and the possible effect of duration of recover from the coronavirus pandemic to both anhedonia and fatigue, and to our knowledge, it is among the leading published research investigating the prevalence of fatigue and anhedonia in post‐COVID‐19 period.

The current study found high score of fatigue in post‐COVID‐19 patients, this is in agreement with Huang, et al 12 who noted that most patients in post‐COVID‐19 period developed muscle ache, arthralgia, weakness, fatigue, or myalgia. Also, this study concluded high scores of different domains of anhedonia which is unique and novel, this is in accordance with Préau et al 13 study mentioned that anhedonia was very common in viral epidemic like HIV‐infected patients with highly active antiretroviral therapies.

Also, this study was unique regarding evaluation not only the total anhedonia score but also: total intensity, total frequency, and total change scores which were not assessed by other studies during the period after recovery from COVID‐19.

The current study evidenced positive correlation between fatigue and anhedonia in post‐COVID‐19 period, and this is in the same way of Zhang et al 14 who said that 38% of people stopped going to workplace due to the pandemic in China,25% stopped working at all and experienced high levels of psychological distress, fatigue anxiety, post‐traumatic stress disorder, and anhedonia.

Also, the study evaluated the onset of anhedonia and fatigue after 2 negative PCR tests of coronavirus leading to a finding of high scores of fatigue and anhedonia during the early days after recovery, this is in parallel with Goyal et al 15 mentioned during the period next 2 weeks after cure from COVID‐19, patients gradually developed sad mood, anhedonia, lethargy, anorexia, insomnia, and easy fatiguability.

In conclusion, post‐COVID‐19 fatigue and anhedonia were common after recovery from novel coronavirus infection that affecting the domains of life of the patients, also the duration after cure affected these 2 manifestations which evoked an important question: Are they a transient sequelae of infection or still persist even after recovery? , this needs more research.

4.1. Study limitations

The study needs more number of cases for more solid data, also the assessment was done once, and more frequent evaluation will be needed for further consolidated results.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

1‐Samir El Sayed (corresponding author): interviewing the patients, data collection, and writing the manuscript. 2‐Doaa Shokry: statistical analysis, biostatics, and helping in data interpretation. 3‐Sarah Gomaa: collection of patients’ data and revision of manuscript.

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from all participants after full explanation of the aim of the study.

APPROVAL OF THE RESEARCH PROTOCOL BY THE INSTITUTIONAL REVIEWER BOARD

IRB approval was taken to conduct this study.

REGISTRY AND REGISTRATION NO. OF THE STUDY/TRIAL

n/a.

ANIMAL STUDIES

n/a.

El Sayed S, Shokry D, Gomaa SM. Post‐COVID‐19 fatigue and anhedonia: A cross‐sectional study and their correlation to post‐recovery period. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep.2021;41:50–55. 10.1002/npr2.12154

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions because the disclosure of personal data was not included in the research protocol of the present study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) outbreak. J Autoimm. 2020;109:102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . WHO Director‐General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID‐19. Geneva; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3. del Rio C, Malani PN. New insights on a rapidly changing epidemic. J Amer Med Assoc. 2020;323(24):1339–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Treadway MT, Zald DH. Reconsidering anhedonia in depression: Lessons from translational neuroscience. NeurosciBiobehav Rev. 2011;35:537–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brodaty H, Altendorf A, Withall A, Sachdev P. Do people become more apathetic as they grow older? A longitudinal study in healthy individuals. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:426–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brooks K, Webster K, Smith E, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hives L, Bradley A, Richards J. Can physical assessment techniques aid diagnosisin people with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis? A diagnostic accuracy study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Perrin R, Riste L, Hann M. Into the looking glass: Post‐viral syndrome post COVID‐19. Med Hypo 2020;144:14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xiang Y‐T, Zhao Y‐J, Liu Z‐H, et al. TheCOVID‐19 outbreak and psychiatric hospitals in China: managing challenges throughmental health service reform. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(10):1741–1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Olivares JM, Berrios GE, Bousoño M. The self‐assessment anhedonia scale (SAAS). Neuro Psychia Brain Res. 2005;12(3):121–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Michielsen HJ, De Vries J, Van Heck GL Psychometric qualities of a brief self‐rated fatigue measure the fatigue assessment scale. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(4):345–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Préau M, Bonnet A, Bouhnik A‐D, Fernandez L, Obadia Y, Spire B. Anhedonia and depressive symptomatology among HIV‐infected patients with highly active antiretroviral therapies (ANRS‐EN12‐VESPA)]. Encephale 2008;34(4):385–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang S, Rauch WY, Rauch A, Wei F. Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: Health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID‐19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goyal K, Chauhan P, Chhikara K, Gupta P, Singh MP. Fear ofCOVID2019: First suicidal case in India. Asia J Psychia. 2020;49:101989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions because the disclosure of personal data was not included in the research protocol of the present study.