Abstract

This case report describes the use of a miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expander and aligners to correct bilateral cross-bite and crowding in an adult patient with a Class III skeletal pattern. A digitally designed surgical guide was three-dimensionally printed and used to accurately insert four miniscrews into the palate; these were employed to anchor a novel miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expander appliance without any dental anchorage. Cone-beam computed tomograms before and after miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expander treatment demonstrated the orthopedic expansion of the maxilla without dental tipping. The patient was then fitted with aligners to correct crowding and malocclusion. This case report demonstrates the successful treatment of an adult patient with a narrow maxilla and bilateral cross-bite using a nonsurgical, conservative treatment.

Keywords: Rapid palatal expander, Aligners, Miniscrew

INTRODUCTION

Nearly 30% of adult orthodontic patients present with a transverse maxillary deficiency and posterior cross-bite. For many years, surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion has been the treatment of choice to resolve maxillary constriction in young adults, although several authors have reported successful nonsurgical expansion in young and adult patients.1–5 However, Chang et al.6 described possible side effects in nonsurgical palatal expansion that, in adult patients, may produce dentoalveolar tipping with unfavorable periodontal effects.

In 2010, Lee et al.7 introduced an appliance secured to the palate by means of miniscrews, the miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expander (MARPE), which was used to treat a 20-year-old patient with transverse discrepancy for mandibular prognathism, obviating the need for orthognathic surgery. Expansion was successfully achieved with minimal damage to the teeth and periodontium, and the authors concluded that MARPE was an effective means of correcting transverse deficits. Moreover, as the miniscrews are anchored to the basal bone, the orthopedic force exerted by the appliance results in pure skeletal movement while minimizing unwanted dental effects.8

Based on the study by Lee et al., many authors have recently developed novel skeletal expanders with the aid of miniscrews, and new MARPE devices have been used to correct maxillary constriction in patients of various ages.9–11 In addition, other authors have developed a hybrid palatal expander, introducing surgical guides (Miniscrew Assisted Palatal Appliance, MAPA system) for miniscrew insertion into the palate to prevent damage to the anatomical structures.12,13 Furthermore, to prevent undesirable tooth anchorage effects at high risk of causing periodontal or root damage, a pure skeletal anchorage expander called the bone-anchored maxillary expander has been described.14

CASE REPORT

This case report describes an adult female patient with Class III malocclusion and bilateral cross-bite treated successfully with a pure skeletal anchorage maxillary expander and aligners.

Diagnosis and Etiology

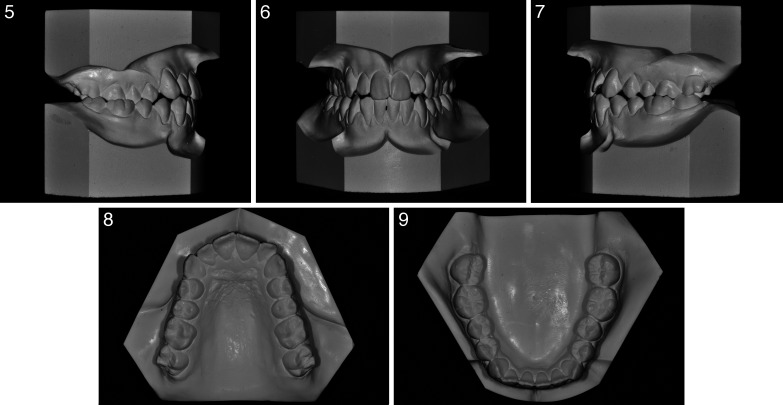

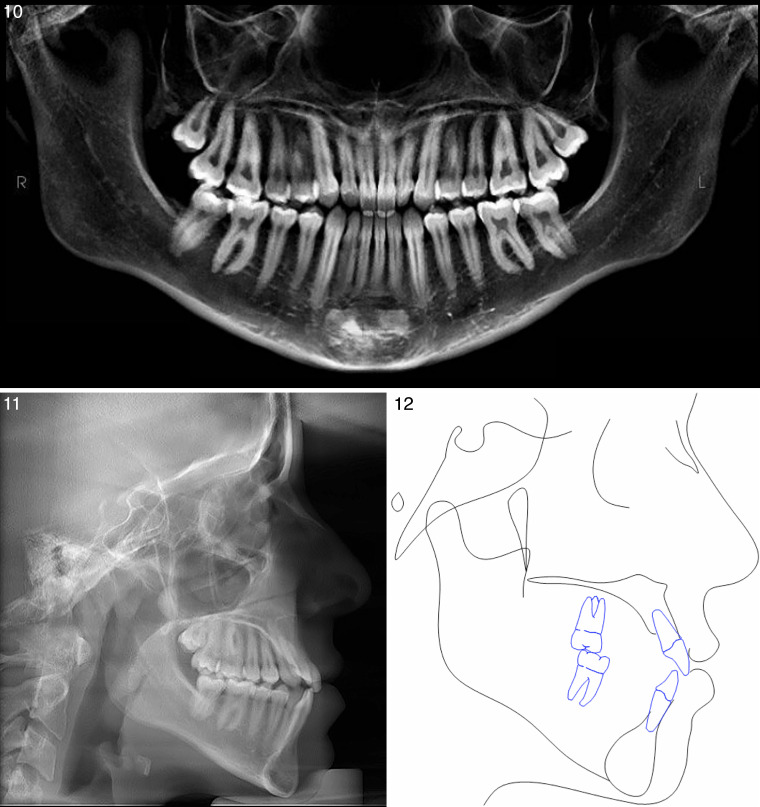

The patient, a 23-year-old woman, presented with a Class III malocclusion, transverse maxillary deficiency, and bilateral cross-bite (Figures 1a–e). Maxillary and mandibular intermolar widths15 were 32 and 38 mm, respectively, and the patient displayed a flat profile and skeletal asymmetry, featuring a deviation of the mandible toward the right (Figures 2–4). Cephalometric analysis showed a Class III relationship (ANB 0, WITS appraisal −5) with a long face (FMA 30.8°). Maxillary incisors were proclined (maxillary central incisor to SN 117°), and the mandibular incisors had a lingual inclination (IMPA 82°) as reported in Table 1. Overjet and overbite were reduced, and the lower dental midline was deviated 3 mm to the right (Figures 5–9).

Figures 1–4.

Initial photographs.

Table 1.

Cephalometric Assessment

| Measurement |

Pretreatment |

Posttreatment |

Change |

| SNA (°) | 82 | 82 | 0 |

| SNB (°) | 81 | 80 | −1 |

| ANB (°) | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| WITS appraisal | −5 | −5 | 0 |

| SN MP (°) | 40 | 41 | 1 |

| FMA (°) | 30.8 | 31.7 | 0.9 |

| Upper 1 to SN (°) | 117 | 107 | 10 |

| Upper 1 to APo (mm) | 7.4 | 6.5 | 0.9 |

| Lower 1 o APo (mm) | 5.3 | 4.4 | 0.8 |

| Lower 1 to MP (°) | 82 | 81 | 1 |

Figures 5–9.

Initial study models.

The patient's gum was delicate, friable, and translucent, demonstrating a thin gingival biotype. Recession was visible at the maxillary and mandibular cuspids and bicuspids, and minor recession at the lower incisors (Figure 1).

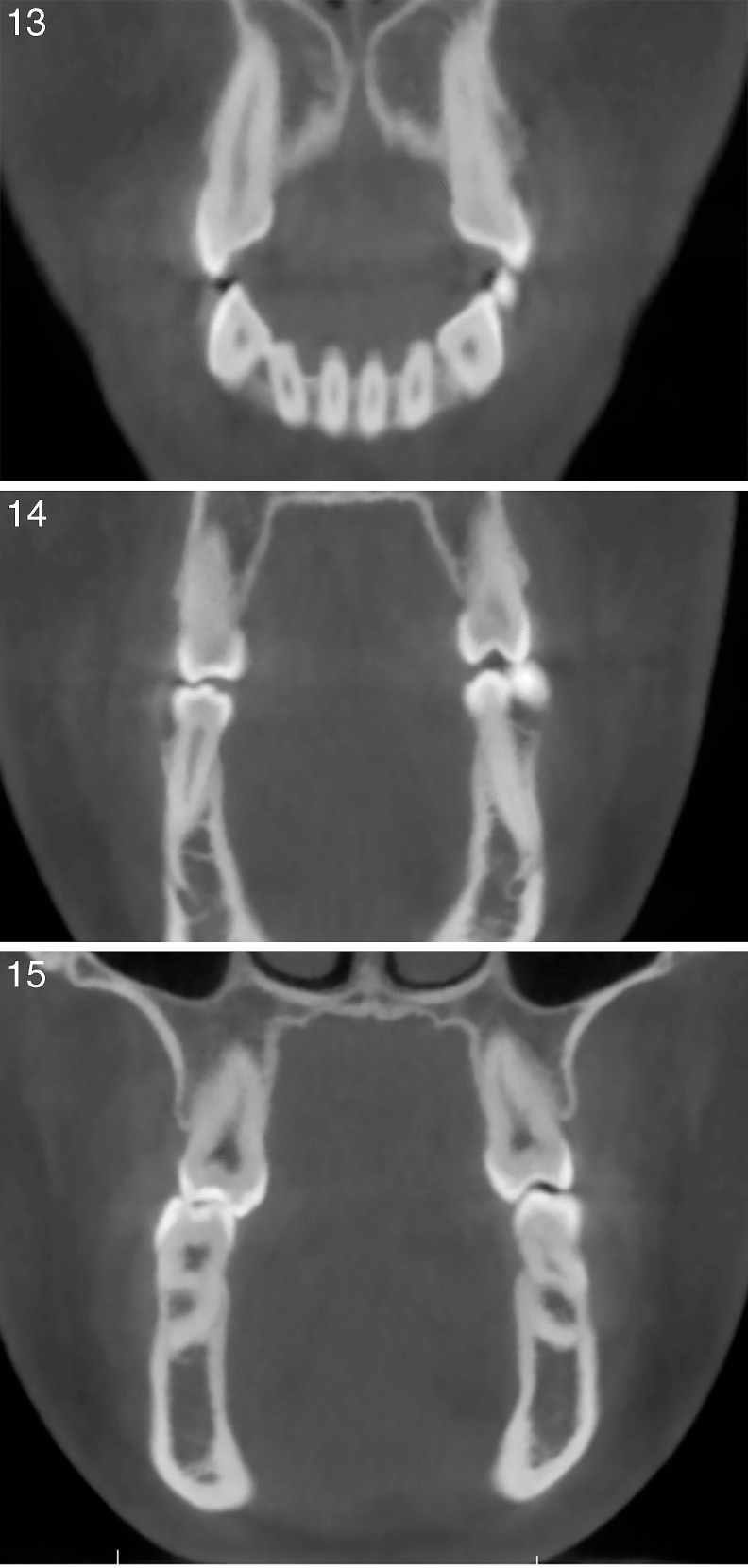

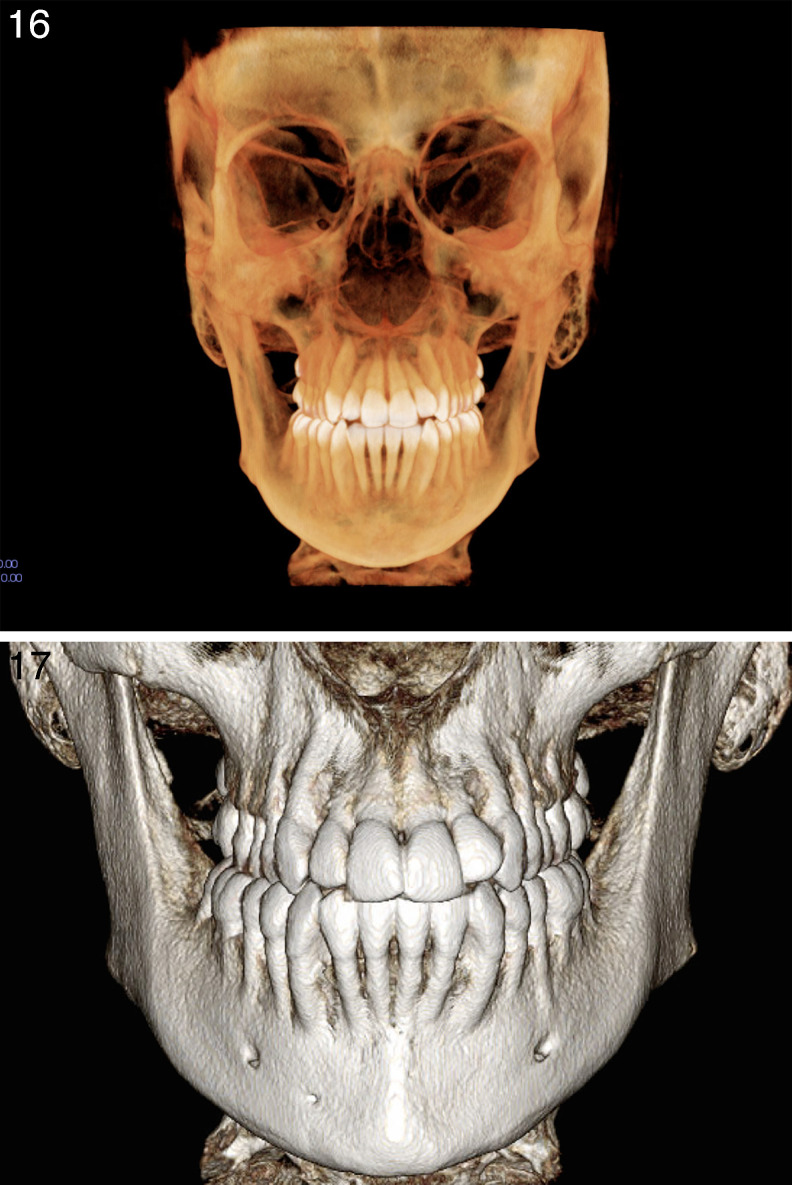

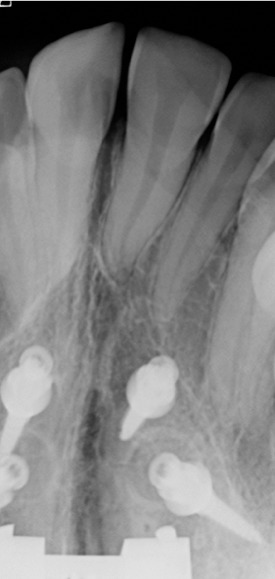

Panoramic and laterolateral teleradiographs were taken by means of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT; Figures 10–12), and an intraoral scan of the dental arches was performed. Axial CBCT slices at the upper cuspids and bicuspids and at the furcation of first molars clearly showed a maxillary traverse deficiency with bilateral cross-bite (Figures 13–15). A three-dimensional skull model also revealed a diffuse paucity of buccal alveolar bone, in accordance with the clinical finding of gingival recession (Figures 16–17). Coronal and sagittal cross-sections were used to measure palatal bone thickness (Figure 18). The patient reported a pronounced family history (both parents) of Class III and maxillary constriction, indicating that the malocclusion was genetic in origin.

Figures 10–12.

Initial radiographs and cephalometric tracing.

Figures 13–15.

Initial cone-beam computed tomography axial slices.

Figures 16–17.

Three-dimensional skull model showing diffuse paucity of buccal alveolar bone.

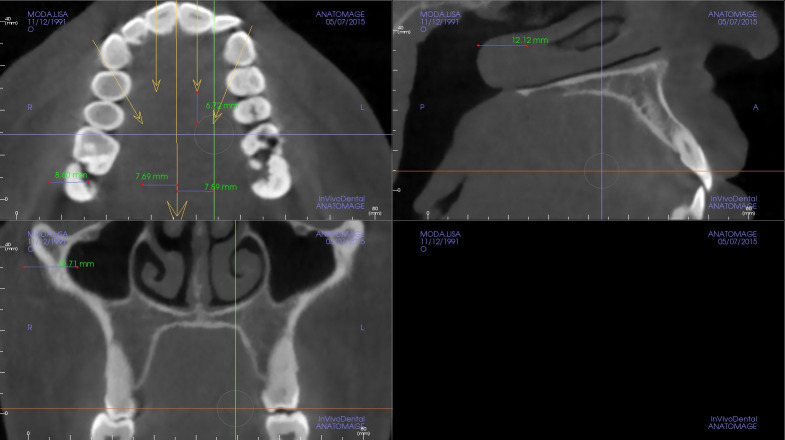

Figure 18.

Cone-beam computed tomography cross-sections showing palatal bone thickness.

Treatment Objectives

The primary objective was orthopedic correction of the posterior cross-bite by skeletal maxillary expansion without any dental compensation or worsening of the periodontal situation. Additional objectives were to achieve molar and canine Class I, correct the crowding, obtain ideal overjet (about 2.5 mm) and overbite (about 2 mm), improve facial esthetics and incisor projection, and reduce black buccal corridors during smile.

Treatment Progress

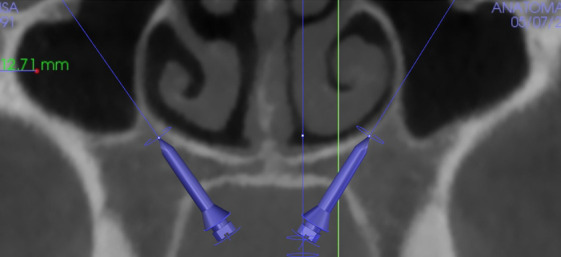

To avoid any adverse effects on the upper teeth, a bone-borne rapid palatal expander was selected. Because the maxilla was narrow and thin in the vertical dimension, the MAPA system protocol was used to insert four miniscrews into the palate.12,13 This protocol enabled bicortical anchorage guaranteeing greater resistance than that provided by orthopedic-loading devices.16

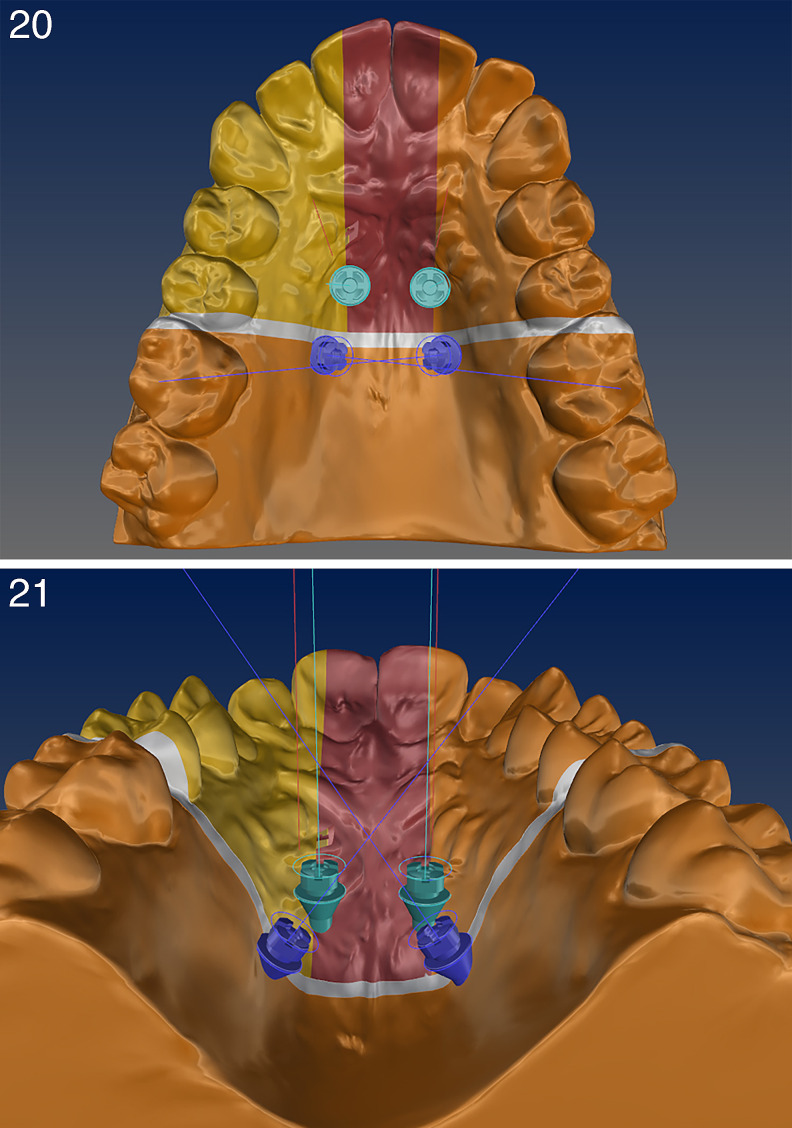

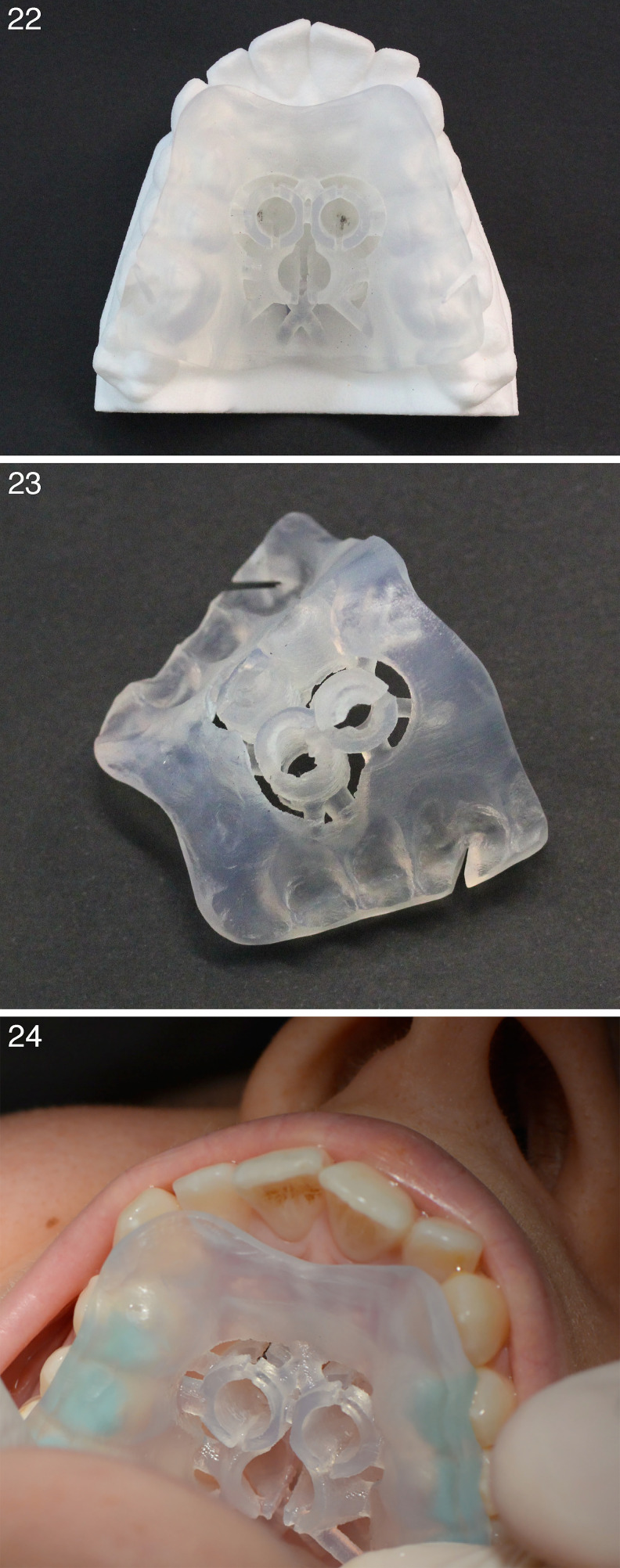

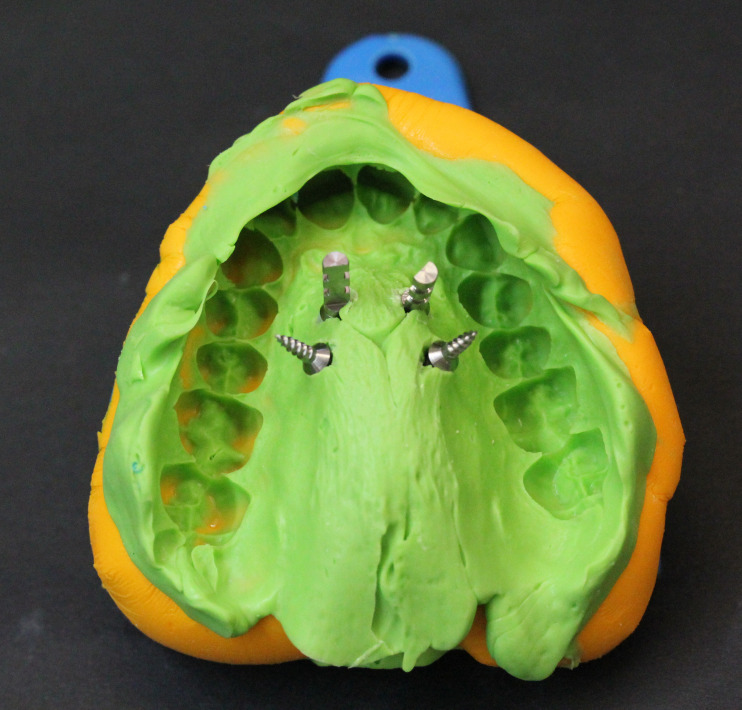

First, the Standard Triangulation Language (STL) files obtained from intraoral scans of the patient were superimposed onto the CBCT Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) files. The thicknesses of the palate were measured, and the ideal positions for four virtual miniscrews were identified (Figures 19–21). A three-dimensional template was then designed and three-dimensionally printed (MAPA system).12,13 It featured precisely positioned cylindrical guide sleeves to enable the correct placement of four miniscrews and rigorous control of the direction of insertion (two 11-mm and two 9-mm miniscrews, Ø 2 mm, Spider Screw, Regular plus, HdC, Thiene, Italy; Figures 22–25). A Polyvinyl Siloxane (PVS) impression of the upper arch was then used to create the expansion device (Figures 26–28). The treatment protocol included two activations per day17 until the mid-palatal suture had opened and the constriction was corrected (Figure 29). With 9 mm of appliance expansion, 7 mm of expansion was obtained at the maxillary first molars, and 4 mm at the maxillary canines (Figure 30). Due to early contact between the upper and lower second molars, the open bite was increased and the device was left in situ for 2 months to stabilize the expansion.

Figure 19.

Cross-section of the maxilla and virtual position of the miniscrews.

Figures 20–21.

Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) and Standard Triangulation Language (STL) file superimposition of intraoral patient maxilla.

Figures 22–24.

Miniscrew Assisted Palatal Appliance (MAPA) creation: three-dimensional–printed template for correct miniscrew placement.

Figure 25.

Miniscrews inserted into the palate after surgical guide removal.

Figure 26.

Polyvinyl Siloxane (PVS) impression showing the position of the miniscrews.

Figure 28.

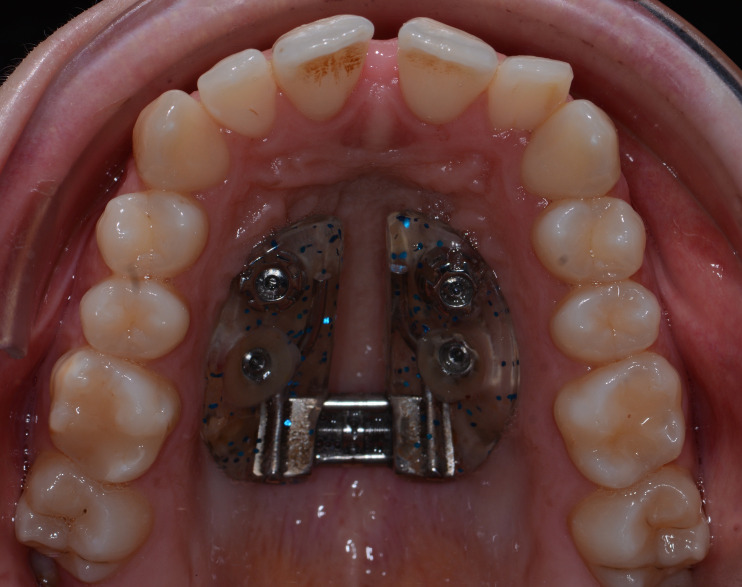

Miniscrew Assisted Palatal Appliance (MAPA) appliance connected only to the four miniscrews.

Figure 29.

Occlusal radiograph demonstrating the mid-palatal suture opening.

Figure 30.

Mid-palatal suture opening.

Figure 27.

Model of the patient's maxilla used for appliance creation.

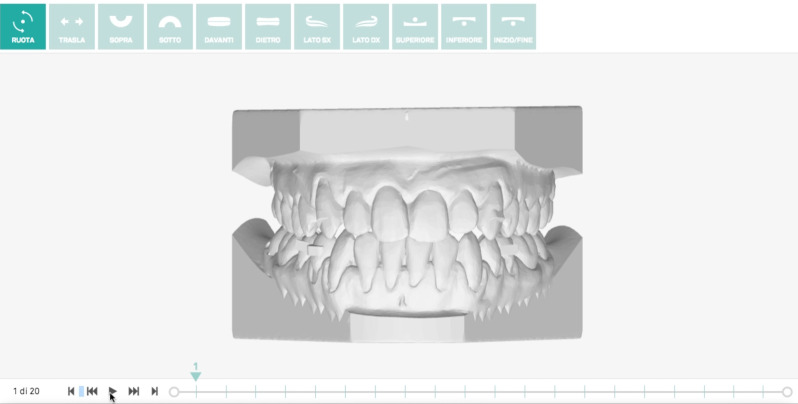

Postexpansion intraoral scans were taken and used to plan aligner treatment. In this phase, interproximal reduction to teeth 13 and 22, 35 and 43 was performed to gain space and facilitate the derotation movements.18–20 Then, 20 upper and lower individualized F22 aligners (Sweden & Martina, Due Carrare, Italy) were delivered to the patient after composite grip points had been attached to the buccal surfaces of teeth 13, 22, 23, 35, 44, and 45 and the lingual surfaces of teeth 12, 11, 21, from 31 to 42 (Figures 31–34), as prescribed by the digital set-up.

Figure 31.

F22 virtual set-up.

Figures 32–34.

Grip-points and Interproximal reduction (IPR).

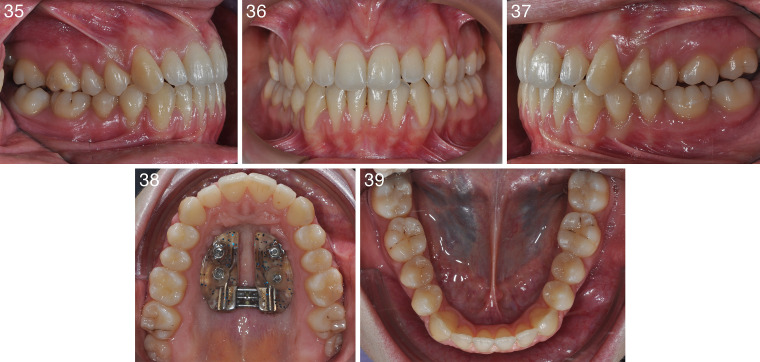

Each aligner was worn for 7 days and, after this series, five upper and lower refinement aligners were prescribed so that an acceptable result could be achieved. Aligner treatment, therefore, lasted slighly longer than 6 months (Figures 35–41). At the end of this phase, the four miniscrews were removed from the palate. After 2 weeks, the peri-implant tissues had completely healed (Figure 42).

Figures 35–39.

Intraoral photograph after the 20-aligner series.

Figures 40–41.

Aligners in place.

Figure 42.

Occlusal photograph after Miniscrew Assisted Palatal Appliance (MAPA) and miniscrew removal.

Treatment Results

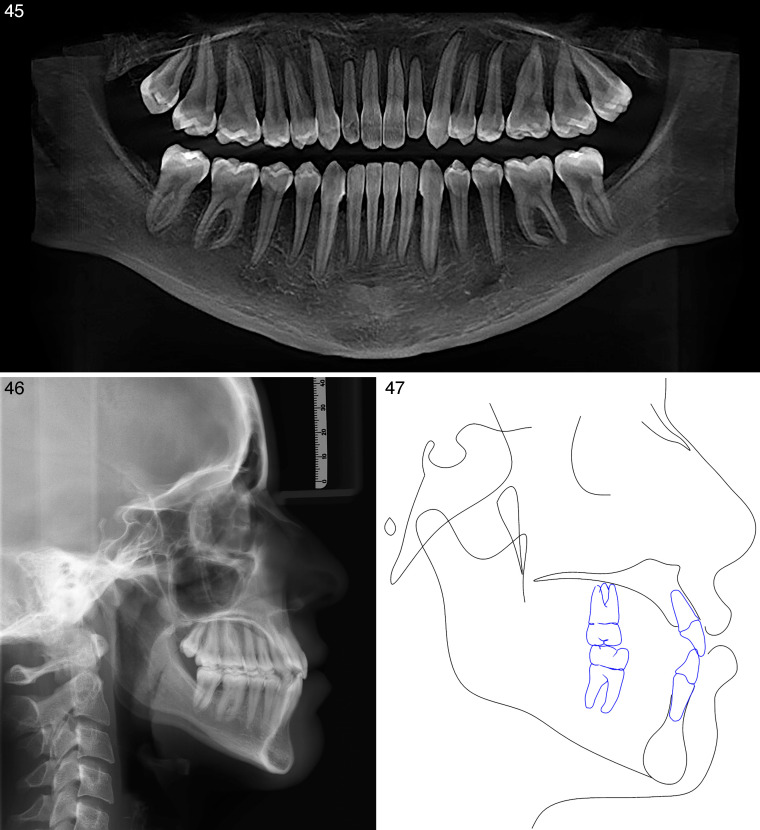

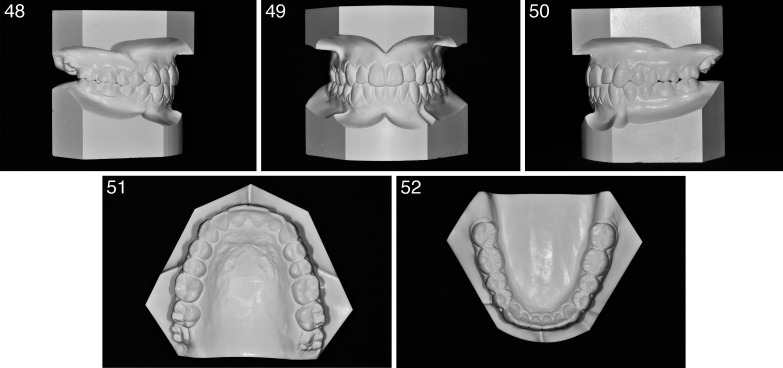

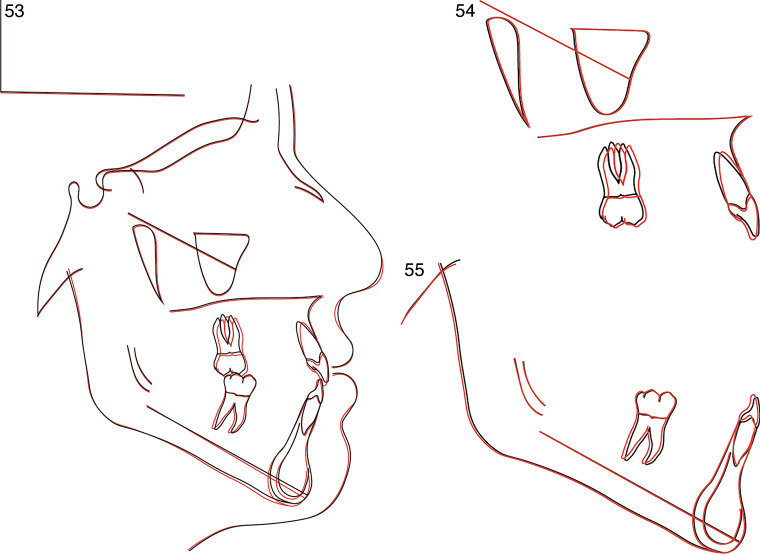

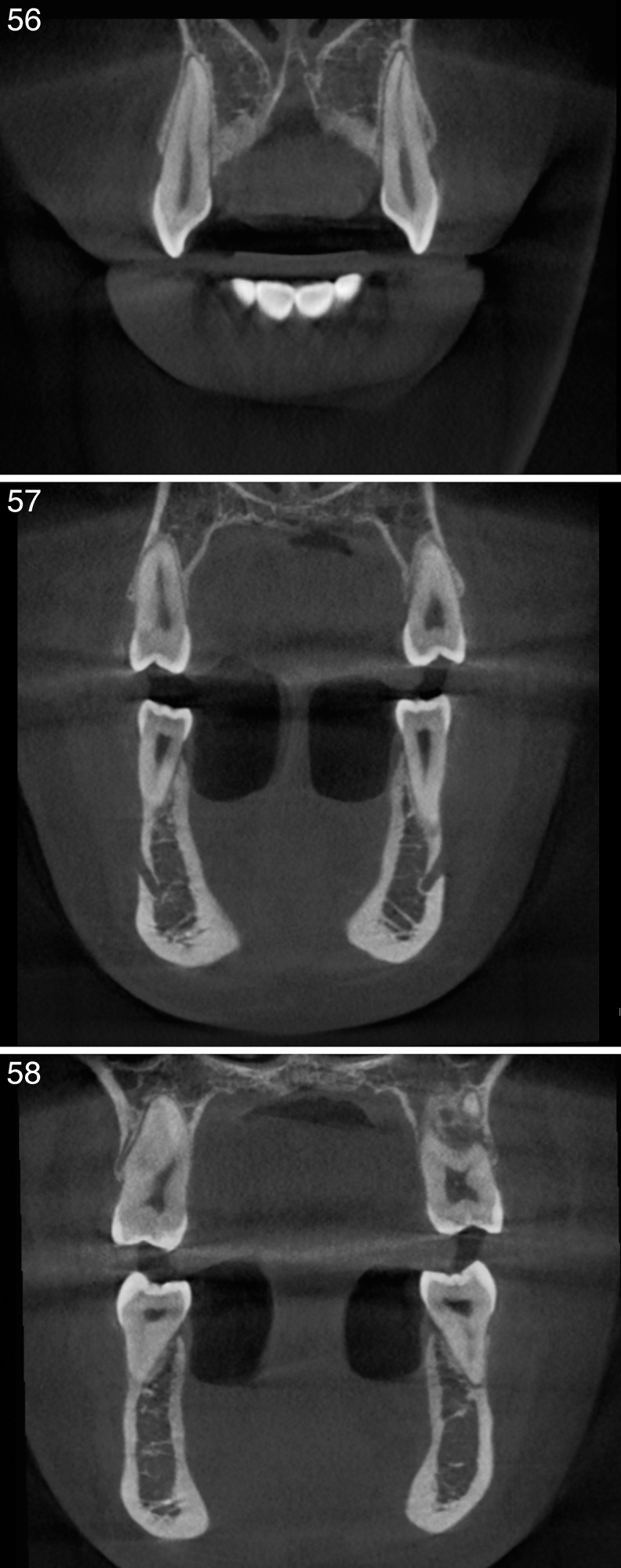

After 10 months, the treatment was complete. The transverse constriction of the upper jaw had been corrected and the bilateral cross-bite resolved. Comparison of the pre- and postoperative radiographs and CBCT images reveal the maxillary expansion (Figures 43–47), which was also visible on dental casts (Figures 48–52). At the end of treatment, the patient displayed Class I molar and canine relationships (due to an increased positive tip, a slight edge-to-edge tendency at the level of the canine was detectable). Cephalometric data revealed an increase in the SNA (82°) and a reduction of the WITS index (Table 1). The data reported in Table 1 also show that the vertical position of the maxilla was relatively unchanged, but that the FMA was slightly increased (31.7°), as demonstrated by the overall superimpositions (Figures 53–55). The upper incisors had been extruded and uprighted while the lower incisors remained unchanged (Table 1). Measures of intermolar widths on the upper arches before and after treatment showed an overall increase in width of 6 mm (at the level of the palatal cusps of the upper first molars; Table 2). Furthermore, all dental and skeletal objectives had been achieved and a satisfactory occlusal outcome was evident with no further increase in recession. Although there had been some thinning of the buccal plates, there was still adequate coverage of the maxillary cuspids, bicuspids, and molar roots even after expansion, as shown in the CBCT slices (Figures 56–58).

Figures 43–44.

Final photographs.

Figures 45–47.

Final radiographs and cephalometric tracing.

Figures 48–52.

Final models.

Figures 53–55.

Superimpositions.

Table 2.

Skeletal Effects of Bone-Borne Rapid Maxillary Expander Interdental Widthsa

| Pretreatment |

Posttreatment |

Difference |

|

| U6 diameter (palatal crown) | 32 mm | 38 mm | 6 mm |

| U6 diameter (apex) | 32.4 mm | 38.1 mm | 5.7 mm |

| U5 diameter (palatal crown) | 28.2 mm | 33.6 mm | 5.4 mm |

| U5 diameter (apex) | 31.4 mm | 37.4 mm | 6 mm |

| U3 diameter (palatal crown) | 31 mm | 34.4 mm | 3.4 mm |

U5: Upper second premolar; U6: Upper first molar; U3: Upper canine.

Figures 56–58.

Final cone-beam computed tomography axial slices showing the final angulation of the dentition.

The face appeared more symmetric, the patient's profile had been maintained, and the overall esthetics had been improved. The patient displayed a nice, broad smile, with improved incisor exposure and no buccal corridors. The patient was instructed to wear the last pair of aligners for retention due to the elastic propriety of the thermoplastic material,21 and slight restoration of tooth 22 was performed to achieve optimal anterior tooth proportions.22 Upon completion of orthodontic treatment, the patient was offered several periodontal surgery interventions to improve the esthetics of the periodontal tissues. This multidisciplinary approach would have further enhanced the final outcome, providing results that could not be achieved by means of orthodontic treatment alone. Unfortunately, however, the patient refused surgery.

DISCUSSION

There is a strong consensus in the literature as to the efficacy of rapid maxillary expansion in growing patients. However, in about 50% of cases, the reported expansion occurred at the mid-palatal suture, whereas in the remaining 50% of cases it was brought about by displacement of the dentoalveolar complex.4 Age is considered a primary factor in the success of palatal expansion, and this is based on the idea that it rapidly becomes inefficient after the early teens.23–25 In adults, surgery had long been considered the only option for orthopedic transverse correction. Nevertheless, many authors have reported cases of rapid maxillary expansion in adult patients based on the assumption that the correction of maxillary constriction results in a displacement of the alveolar process associated with buccal displacement of the teeth.26 However, rapid maxillary expansion in adults can produce unwanted effects, including lateral tipping of the posterior teeth,27,28 extrusion,29,30 buccal root resorption,31,32 alveolar bone bending,33 fenestration of the buccal cortex,34,35 pain, and instability of the expansion.28,30,35

Carlson et al.17 and Mosleh et al.36 have reported successful outcomes in patients treated with MARPE, but these authors relied on an appliance anchored partially to the teeth. Winsauer et al.,14 on the other hand, reported one case of a 30-year-old patient successfully treated with bone-borne anchorage without unwanted dental effects.

To achieve true skeletal expansion, in this case a pure skeletal anchorage expander was designed using a MAPA system to prevent any possible damage to the anatomical structures. Contrary to the belief that nonsurgical palatal expansion is impossible in adult patients, the posttreatment records of this adult patient clearly show skeletal expansion, verified by measurements of CBCT images and models (Table 2). The posttreatment records of the patient show that the buccal tipping of the teeth was well controlled37,38 (Figures 56–58; Table 3). The careful MARPE design and expansion protocol also resulted in a notable improvement in the patient's esthetics.39 Once orthopedic expansion of the upper jaw had been achieved, fully resolving the bilateral cross-bite, the patient was then fitted with aligners40; this confined the dental movements to the required teeth.

Table 3.

Skeletal Effects of Bone-Borne Rapid Maxillary Expander Buccolingual Angulation

| Pretreatment |

Posttreatment |

Difference |

|

| 16 angulation | 99.1° | 99.7° | 0.6° |

| 26 angulation | 99.1° | 99.2° | 0.1° |

| 15 angulation | 92.2° | 92.2° | 0° |

| 25 angulation | 90.6° | 92° | 1.4° |

| 13 angulation | 102.2° | 100° | 2.2° |

| 23 angulation | 104.2° | 101° | 3.2° |

Such appliances as aligners can be extremely useful in adult patients, especially in those with Class III or vertical discrepancy issues, as they maintain dental compensation without the need for other sources of anchorage.41 Aligners also enable optimal oral hygiene, especially in adults, in whom there is a greater risk of periodontal problems and a greater likelihood of having a thin gingival biotype.42–44 A further advantage of aligner treatment is the favorable esthetics, which makes them better tolerated in patients, especially adults.

CONCLUSIONS

The successful resolution of this case shows the efficacy of a combined protocol involving miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expander and aligner treatment to resolve Class III malocclusion with bilateral cross-bite in an adult patient, despite the widespread belief that nonsurgical correction of such cases is impossible. This orthopedic approach resulted in a better outcome than that previously reported in the literature, even those pertaining to younger patients.

This new MARPE design and protocol is a promising addition to the range of orthopedic expansion options, with lower risks and costs than other surgical approaches.

Further studies are required to confirm the findings in a larger sample of patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brunelle JA, Bhat M, Lipton JA. Prevalence and distribution of selected occlusal characteristics in the US population, 1988-1991. J Dent Res. 1996;75:706–713. doi: 10.1177/002203459607502S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shetty V, Caridad JM, Caputo AA, Chaconas SJ. Biomechanical rationale for surgical-orthodontic expansion of the adult maxilla. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52:742–749. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stuart DA, Wiltshire WA. Rapid palatal expansion in the young adult: time for a paradigm shift? J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:374–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Handelman CS, Wang L, BeGole EA, Haas AJ. Nonsurgical rapid maxillary expansion in adults: report on 47 cases using the Haas expander. Angle Orthod. 2000;70:129–144. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2000)070<0129:NRMEIA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capelozza Filho L, Cardoso Neto J, da Silva Filho OG, Ursi WJ. Non-surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion in adults. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1996;11:57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang JY, McNamara JA, Jr, Herberger TA. A longitudinal study of skeletal side effects induced by rapid maxillary expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;112:330–337. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(97)70264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee KJ, Park YC, Park JY, Hwang WS. Miniscrew-assisted nonsurgical palatal expansion before orthognathic surgery for a patient with severe mandibular prognathism. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:830–839. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ludwig B, Baumgaertel S, Zorkun B, et al. Application of a new viscoelastic finite element method model and analysis of miniscrew-supported hybrid Hyrax treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;143:426–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moon W, Machado A. Interview with Won Moon. Dental Press J Orthod. 2013;18:12–28. doi: 10.1590/s2176-94512013000300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curado MM, Suzuki SS, Suzuki H, Garcez AS. Uma nova alternativa para a expansão rápida da maxila assistida por mini-implantes usada para a correção ortopédica em paciente Classe III esquelética em crescimento. In: Junqueira JLC, Napimoga MH, editors. Ciência e Odontologia casos clínicos baseado em evidências científica. Campinas: Mundi Brasil;; 2015. pp. 232–237. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki H, Moon W, Previdente LH, Suzuki SS, Garcez AS, Consolaro A. Expansão rápida da maxila assistida com mini-implantes ou MARPE: em busca de um movimento ortopédico puro. Rev Clín Ortod Dental Press. 2016;15:110–125. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maino G, Paoletto E, Lombardo L, Siciliani G. MAPA: a new high-precisiom 3d method of palatal miniscrew placement. EJCO. 2015;3:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maino BG, Paoletto E, Lombardo L, Siciliani G. A three-dimensional digital insertion guide for palatal miniscrew placement. J Clin Orthod. 2016;50:12–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winsauer H, Vlachojannis J, Winsauer C, Ludwig B, Walter A. A bone-borne appliance for rapid maxillary expansion. J Clin Orthod. 2013;47:375–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lombardo L, Setti S, Molinari C, Siciliani G. Intra-arch widths: a meta-analysis. Int Orthod. 2013 Jun;11(2):177–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ortho.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lombardo L, Gracco A, Zampini F, Stefanoni F, Mollica F. Optimal palatal configuration for miniscrew applications. Angle Orthod. 2010;80:145–152. doi: 10.2319/122908-662.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlson C, Sung J, McComb RW, Machado AW, Moon W. Microimplant-assisted rapid palatal expansion appliance to orthopedically correct transverse maxillary deficiency in an adult. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2016;149:716–728. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheridan JJ. Air-rotor stripping. J Clin Orthod. 1985;19:43–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheridan JJ. Air-rotor stripping update. J Clin Orthod. 1987;21:781–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossini G, Parrini S, Castroflorio T, Deregibus A, Debernardi CL. Efficacy of clear aligners in controlling orthodontic tooth movement: a systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2015;85:881–889. doi: 10.2319/061614-436.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lombardo L, Martines E, Mazzanti V, Arreghini A, Mollica F, Siciliani G. Stress relaxation properties of four orthodontic aligner materials: a 24-hour in vitro study. Angle Orthod. 2017;87:11–18. doi: 10.2319/113015-813.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolton WA. Disharmony in tooth size and its relation to the analysis and treatment of malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 1958;28:113–130. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNamara JA, Jr, Brudon WL. Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. Needham, MA: Needham Press;; 2001. pp. 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerbs A. Midpalatal suture expansion studies by the implant method over a seven-year period. Rep Congr Eur Orthod Soc. 1964;40:131–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Handelman CS. Nonsurgical rapid maxillary alveolar expansion in adults: a clinical evaluation. Angle Orthod. 1997;67:291–308. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1997)067<0291:NRMAEI>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Handelman C. Palatal expansion in adults: the nonsurgical approach. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011. 140:462, 464, 466, 468. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Timms DJ. A study of basal movement with rapid maxillary expansion. Am J Orthod. 1980;77:500–507. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(80)90129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wertz RA. Skeletal and dental changes accompanying rapid midpalatal suture opening. Am J Orthod. 1970;58:41–66. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(70)90127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mommaerts MY. Transpalatal distraction as a method of maxillary expansion. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;37:268–272. doi: 10.1054/bjom.1999.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zimring JF, Isaacson RJ. Forces produced by rapid maxillary expansion. 3. Forces present during retention. Angle Orthod. 1965;35:178–186. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1965)035<0178:FPBRME>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barber AF, Sims MR. Rapid maxillary expansion and external root resorption in man: a scanning electron microscope study. Am J Orthod. 1981;79:630–652. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(81)90356-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langford SR, Sims MR. Root surface resorption, repair, and periodontal attachment following rapid maxillary expansion in man. Am J Orthod. 1982;81:108–115. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shetty V, Caridad JM, Caputo AA, Chaconas SJ. Biomechanical rationale for surgical-orthodontic expansion of the adult maxilla. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52:742–749. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alpern MC, Yurosko JJ. Rapid palatal expansion in adults with and without surgery. Angle Orthod. 1987;57:245–263. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1987)057<0245:RPEIA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenbaum KR, Zachrisson BU. The effect of palatal expansion therapy on the periodontal supporting tissues. Am J Orthod. 1982;81:12–21. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosleh MI, Kaddah MA, ElSayed FAA, ElSayed HS. Comparison of transverse changes during maxillary expansion with 4-point bone-borne and tooth-borne maxillary expanders. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2015;148:599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christie KF, Boucher N, Chung CH. Effects of bonded rapid palatal expansion on the transverse dimensions of the maxilla: a cone-beam computed tomography study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137(suppl):S79–S85. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lagravere MO, Carey J, Heo G, Toogood RW, Major PW. Transverse, vertical, and anteroposterior changes from bone-anchored maxillary expansion vs traditional rapid maxillary expansion: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:304.e1–e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mirabella D1, Bacconi S, Gracco A, Lombardo L, Siciliani G. Upper lip changes correlated with maxillary incisor movement in 65 orthodontically treated adult patients. World J Orthod. 2008;9:337–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gu J, Tang JS, Skulski B, et al. Evaluation of Invisalign treatment effectiveness and efficiency compared with conventional fixed appliances using the Peer Assessment Rating index. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;151:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guarneri MP, Oliverio T, Silvestre I, Lombardo L, Siciliani G. Open bite treatment using clear aligners. Angle Orthod. 2013;83:913–919. doi: 10.2319/080212-627.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Azaripour A, Weusmann J, Mahmoodi B, et al. Braces versus Invisalign®: gingival parameters and patients' satisfaction during treatment: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:69. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0060-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abbate GM, Caria MP, Montanari P, et al. Periodontal health in teenagers treated with removable aligners and fixed orthodontic appliances. J Orofac Orthop. 2015;76:240–250. doi: 10.1007/s00056-015-0285-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lombardo L, Ortan YÖ, Gorgun Ö, Panza C, Scuzzo G, Siciliani G. Changes in the oral environment after placement of lingual and labial orthodontic appliances. Prog Orthod. 2013;14:28. doi: 10.1186/2196-1042-14-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]