Abstract

Introduction

Debate around a common definition of global health has seen extensive scholarly interest within the last two decades; however, consensus around a precise definition remains elusive. The objective of this study was to systematically review definitions of global health in the literature and offer grounded theoretical insights into what might be seen as relevant for establishing a common definition of global health.

Method

A systematic review was conducted with qualitative synthesis of findings using peer-reviewed literature from key databases. Publications were identified by the keywords of ‘global health’ and ‘define’ or ‘definition’ or ‘defining’. Coding methods were used for qualitative analysis to identify recurring themes in definitions of global health published between 2009 and 2019.

Results

The search resulted in 1363 publications, of which 78 were included. Qualitative analysis of the data generated four theoretical categories and associated subthemes delineating key aspects of global health. These included: (1) global health is a multiplex approach to worldwide health improvement taught and pursued at research institutions; (2) global health is an ethically oriented initiative that is guided by justice principles; (3) global health is a mode of governance that yields influence through problem identification, political decision-making, as well as the allocation and exchange of resources across borders and (4) global health is a vague yet versatile concept with multiple meanings, historical antecedents and an emergent future.

Conclusion

Extant definitions of global health can be categorised thematically to designate areas of importance for stakeholders and to organise future debates on its definition. Future contributions to this debate may consider shifting from questioning the abstract ‘what’ of global health towards more pragmatic and reflexive questions about ‘who’ defines global health and towards what ends.

Keywords: health education and promotion, health policy, public health, qualitative study, systematic review

Key questions.

What is already known?

Debate around a common definition of global health has seen extensive scholarly interest within the last two decades; despite the abundance of literature, ambiguity still persists around its precise definition.

No systematic reviews with thematic analysis have been conducted to explore extant definitions of global health nor to contribute to a comprehensive definition of global health.

What are the new findings?

We compile and thematically analyse extant definitions of global health and propose grounded theoretical insights into what might be seen as relevant for establishing a common definition of global health moving forward.

The need for a clear and concise definition of global health has the highest stakes in the domain of global health policy governance.

What do the new findings imply?

Stakeholders tend to define the ‘what’ of global health: its spaces, objects and practices. Our findings suggest that the debate around definition should shift to more pragmatic and reflexive questions regarding ‘who’ defines global health and towards what ends.

Introduction

Debate around a common definition of global health (GH) has seen extensive scholarly interest within the last two decades. In 2009, a widely circulated paper by Koplan and colleagues aimed to establish ‘a common definition of global health’ as distinct from its derivations in public health (PH) and international health (IH).1 They rooted the definition of PH in the mid-19th century social reform movements of Europe and the USA, the growth of biological and medical knowledge, and the discipline’s emphasis on population-level health management. Similarly, they traced the evolution of IH back to its colonial roots in hygiene and tropical medicine (TM) through to the mid-20th century with its geographic focus on developing countries. GH, they argued, would require a distinctive definition of its own to be ‘more than a rephrasing of a common definition of PH or a politically correct updating of international health’. Their intervention built on prior research noting confusion and overlap among the three terms and thus a need to carefully articulate the important differences between them.2–5 Additional stakeholders have since elaborated varied definitions of GH, yet consensus around its precise definition remains elusive.

To determine how GH is presently defined and to identify whether a common conceptualisation has been established, we conducted a qualitative systematic literature review (SLR) of the GH literature between 2009 and 2019. SLRs are a methodology used ‘to identify, appraise and synthesize all the empirical evidence that meets pre-specified eligibility criteria to answer a given research question’.6 Unlike unsystematic narrative reviews, SLRs use formal, repeatable and transparent, procedures for identifying, evaluating and interpreting available research, thus ensuring robust coverage of the current literature while reducing the biased presentation of available evidence.7–9 Medical researchers and policy-makers have long relied on SLRs because they integrate and critically evaluate current knowledge to support decisions about important issues.10 However, very few SLRs exploring aspects of GH have yet been published,11–13 and no SLRs focusing on extant definitions of GH have been conducted. This paper fills that gap by exploring the thematic components of extant definitions and thereby contributes towards a comprehensive definition of GH.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this review is: (a) to examine how GH has been defined in the literature between 2009 and 2019, (b) to systematically analyse the core thematic categories undergirding extant definitions of GH and (c) to offer grounded theoretical insights into what might be seen as relevant for establishing a common definition of GH.

Methods

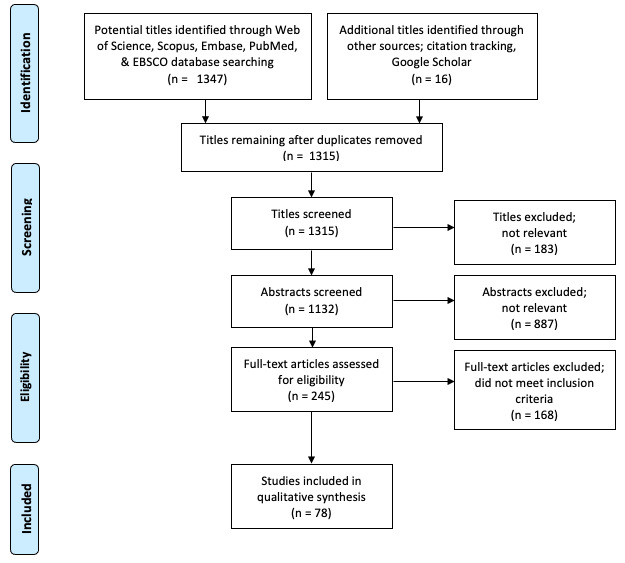

Aiming to capture definitions of GH in literature between 2009 and 2019, our team conducted a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (figure 1).14 The sequential steps of our review process included the following.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of citation analysis and systematic literature review. 14

Search strategy: identify papers and relevant databases

Search technique

The terms ‘global health’ AND ‘define’ OR ‘definition’ OR ‘defining’ were queried when they appeared in the title, abstract or keyword of studies. Published studies were identified through comprehensive searches of electronic databases accessible through the authors’ university library system (Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, PubMed, EBSCO). Citation tracking through Google Scholar was also completed.

Study selection criteria

Articles published in international peer-reviewed journals, including conference papers, book chapters and editorial material, were reviewed. The studies included were written in English and published between 2009 and 2019. The year 2009 was chosen as a starting point because this is the year in which Koplan et al published ‘Towards a Common Definition of Global Health’. For this review, the team excluded news articles, theses, book reviews and published papers that were not written in English.

Assessment strategy: appraise which papers to include in review

The protocol-driven search strategy required that articles included in the review must: (a) contain the keywords ‘global health’ and ‘definition’ and/or ‘define’; (b) be in the English language and (c) be published between 2009 and 2019. The number of articles containing these keywords was recorded, and all the titles uncovered in the search were imported into Mendeley, a software for managing citations. Duplicates were identified and removed, after which abstracts were screened to assess eligibility against the inclusion criteria. Full-text articles were retrieved for those that met the inclusion criteria and three team members read a designated number of the articles selected for full review. To be included in the data extraction sheet, each article needed to: (a) focus on and explicitly name GH, (b) offer an original definition or description of GH and/or (c) cite an already-existing definition of GH. Articles that mentioned the query terms without any relation to these requirements (eg, did not provide a definition of GH or descriptive data to support interpretations of a GH definition) were excluded. Assessment for relevance and content was conducted by two investigators who reviewed all identified articles independently. Disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third investigator.

Synthesis strategy: extract the data

Based on the research goals, the team designed an initial coding template in Google Sheets as a method of documentation, with the following coding variables: author, title, typology, definition(s), conclusions and conceptual dimensions. To achieve a high level of reliability, the review team open-coded the same five articles, compared their coding experiences, and reconciled differences before adopting a final coding template and evenly dividing the remaining articles to be analysed. Extracted data included the type of study or research paradigm of each publication, the location and disciplinary affiliation of each study based on the contact information of the corresponding author, definitions and descriptions of GH and specialised dimensions of GH. Whenever articles contained more than one definition or description of GH, those items were organised line-by-line under the author on the data extraction sheet.

Analysis strategy: analyse the data

The team conducted thematic analysis of the data to understand how GH has been defined since 2009. Our approach to thematic analysis was based on the guidelines described by Thomas and Harden15 and further informed by principles in grounded theory.16 Our strategy consisted of three main stages: Initial Coding—remaining open to all possible emergent themes indicated by readings of the data;16 17 Focused Coding—categorising the data inductively based on thematic similarity at the level of description17 and finally, Theoretical Coding—integrating thematic categories into core theoretical constructs at a higher level of analysis.18

In the first cycle, open descriptive codes were generated (eg, differences between PH and IH, GH education requirements, social justice values) directly from the definitions and descriptions of GH found in the articles. Individual sentences defining or describing GH were treated as unique line items on the data extraction sheet and coded accordingly in order to generate a range of ideas and information on which to build.

In the second cycle, a focused thematic analysis was carried out to identify general relationships and patterns among definitions in the literature and to confirm significant links between the openly coded data. Thematic phrases (eg, GH is multidisciplinary, GH promotes equity) were developed and reapplied to coded definitions on the data extraction sheet. Team members wrote and attached analytic memos to each coded datum—reflecting on emergent patterns and further ‘codeweaving’,18 which is a term for charting possible relationships among the coded data. At this stage, additional coding techniques were utilised. Attribute coding was applied as a management technique for logging information about the characteristics of each publication.19 Data segments coded in this manner were extracted from the main data extraction form and reassembled together in a separate Google Sheet for further analysis. The team also coded extracted definitions of GH by type: (a) original definition, (b) cited definition, (c) original description to track possible relationships between citational practices and developments in the conceptualisation and definition of GH.

In the third cycle, thematic phrases were ordered according to frequency then commonality and abstracted for overriding significance into theoretical categories. At this stage, the conceptual level of analysis was raised from description to a more abstract, theoretical level leading to a grounded theory. This resulted in the construction of four thematic categories, which are presented below with their supporting subthemes.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not directly involved in this review; we used publicly available data for the analysis.

Results

The search strategy retrieved bibliographic records for 1363 papers. The assessment strategy resulted in the elimination of 1237 papers after the removal of duplicates. Consequently, 78 papers were subjected to our strategies of synthesis (data extraction) and analysis.

Characteristics of study

A variety of studies were included in this review. The majority (27) were commentaries, viewpoints or debates.1 20–48 Twenty-four were grouped as review/overview articles.45–68 There were 25 original research articles, of which 13 used qualitative methods,69–81 11 used mixed-methods82–92 and one93 used quantitative data from a survey to proffer definitions of GH. Two studies included in the review were book chapters.94 95

The typologic, geographic and disciplinary distribution of the studies in this review are shown in table 1. Most studies were authored in North America (40), 1 20–31 39–41 43 46 47 50 54–58 61 63 66 68 70 73 74 76–80 83 84 86 87 89–91 94 followed by European countries (29),22 26 28 32 34–38 42 44 45 48 51 52 59 62 64 65 67 71 75 82 85 88 92 93 95 96 countries in Asia (2), 33 72 Latin America and the Caribbean (2), 60 81 and New Zealand (1).20 Disciplinary fields represented in our sample included health (56), 20 22–27 30–32 34–40 42 43 45–51 54–56 58–61 63–69 72 74 75 77–79 82–84 86 88–91 93 95 law, social and cultural professions (19), 1 20 28 29 33 41 44 52 53 57 62 70 71 73 76 80 81 87 92 94 and education (2).20 31

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics of retrieved publications

| Study type | Publications (n=78) |

| Perspective/commentary | 27 |

| Review/overview article | 24 |

| Mixed methods | 11 |

| Qualitative methods | 13 |

| Quantitative methods | 1 |

| Book chapter | 2 |

| Study setting (region/country) | |

| North America | n=40 |

| USA | 30 |

| Canada | 10 |

| Europe | n=29 |

| England | 16 |

| Netherlands | 1 |

| Switzerland | 2 |

| Germany | 6 |

| Norway | 2 |

| Croatia | 1 |

| Spain | 1 |

| Belgium | 1 |

| Africa | n=3 |

| South Africa | 3 |

| Latin America & Caribbean | n=2 |

| Brazil | 1 |

| Caribbean, Trinidad & Tobago | 1 |

| Asia | n=2 |

| Bangladesh | 1 |

| Israel | 1 |

| Oceania | n=1 |

| New Zealand | 1 |

| Authors’ departmental affiliation | |

| Health | n=61 |

| Medicine | 27 |

| Global health | 10 |

| Public health | 10 |

| International health | 6 |

| Nursing | 3 |

| Tropical medicine and hygiene | 1 |

| Global public health | 1 |

| Epidemiology | 1 |

| Other (health science, health admin, etc.) | 3 |

| Legal, social, cultural | n=14 |

| Policy/political science | 6 |

| Anthropology | 4 |

| Sociology | 3 |

| Law | 1 |

| Education | n=2 |

| Engineering education | 1 |

| Medical education | 1 |

Attributes of definitions

All 78 studies under review defined, described and/or cited extant definitions of GH. The 34 papers shown in table 2 included descriptive definitions of GH that were formulated distinctly by its authors, that is, they were presented as original and without direct reference to other definitions.

Table 2.

How global health has been defined by academics since 2009

| Year | Reference | Author | Definition |

| 2009 | 1 | Koplan et al | Global health is an area of study, research and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide. Global health emphasises transnational health issues, determinants and solutions; involves many disciplines within and beyond the health sciences and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration and is a synthesis of population-based prevention with individual-level clinical care. |

| 2009 | 56 | Janes and Corbett | Global health is an area of research and practice that endeavours to link health, broadly conceived as a dynamic state that is an essential resource for life and well-being, to assemblages of global processes, recognising that these assemblages are complex, diverse, temporally unstable, contingent and often contested or resisted at different social scales. |

| 2010 | 20 | Beaglehole and Bonita | Our proposed definition for global health is collaborative transnational research and action for promoting health for all. |

| 2010 | 22 | Bozorgmehr | The field is about building and rebuilding, researching and analysing, teaching and learning the links between social determinants of people’s health anywhere in the world. |

| 2010 | 49 | Crump and Sugarman | Multiple disciplines and multiple activities take place under the umbrella of global health including in the clinical, public health, research and education arenas. |

| 2010 | 50 | Frenk et al | Global health is the goal of improving health for all people in all nations by promoting wellness and eliminating avoidable disease, disability and death. It can be attained by combining population-based health promotion and disease prevention measures with individual-level clinical care (US Institute of Medicine, 2009). |

| 2010 | 27 | Fried et al | Global health and public health are indistinguishable. Both view health in terms of physical, mental and social well-being, rather than merely the absence of disease. Both emphasise population-level policies, as well as individual approaches to health promotion. And both address the root causes of ill-health through a broad array of scientific, social, cultural, and economic strategies. |

| 2010 | 51 | Haffeld et al | The term ‘global health’ implies a globally shared responsibility to provide health as a public good through an expansive number of initiatives. |

| 2010 | 76 | Lakoff | Global Health is a contested ethical, political and technical zone whose contours are still under construction. |

| 2011 | 46 | Arthur et al | Global health issues of the modern world require coordinated multisectoral, multidisciplinary and multinational efforts to achieve effective resolutions to new multidisciplinary multinational health challenges produced by globalisation. |

| 2011 | 70 | Brada | ‘Global health’ is an argument, a position, as much as, if not more than, a thing-in-the-world. The terms of ‘global health’ are best understood as chronotropic, and demonstrate how actors orient themselves and others spatio-temporally, morally and professionally |

| 2011 | 89 | Redwood-Campbell et al | The 11 defining values and principles for global health are: social justice, sustainability, reciprocity, respect, honesty and openness, humility, responsiveness and accountability, equity and solidarity. |

| 2012 | 23 | Campbell et al | The primary characteristics of a global health definition—that it crosses borders, has a multitude of causes and involves a range of means and solutions—imply the need for multiple professionals and disciplines in addition to medical professionals… but may not always be needed. A multidisciplinary approach is often, but not always, needed and beneficial and is therefore not an essential component of the field of the definition. |

| 2012 | 78 | Peluso et al | The definition of global health must be rooted in health equity and focus on the collaborative and multidisciplinary nature of global health, with an emphasis on cross-cultural interactions. |

| 2013 | 86 | Garay et al | We articulate principles that should apply to collective action on global health. These three principles are health for all (for all people worldwide), health by all (by a representative range of stakeholders and actors) and health in all (multisectoral efforts to increase health, with special attention to social determinants of health). |

| 2012 | 32 | Rowson et al | Global health is a field that is characterised by vast differences in the phenomena that can be studied, stretching from economic, political and social relationships to biological processes and even to the technologies that deliver health-sustaining resources such as water, sanitation and agricultural improvements. |

| 2013 | 94 | Farmer et al | Global health is not yet a discipline but rather a collection of problems. The authors of this volume believe that the process of rigorously analysing these problems, of working to solve them and of transforming the field of global health into a coherent discipline demands an interdisciplinary approach. |

| 2013 | 25 | De Cock et al | The New Global Health concerns health in all countries and encompasses poverty alleviation, universal health security and delivery of appropriate public health and clinical services, including for the increasing prevalence of noncommunicable diseases. |

| 2013 | 33 | Margolis | Global Health cannot be defined precisely, but several different authoritative bodies have agreed on key elements to a valid definition. These four key elements—(1) equity, (2) global preventive medicine, public health and primary care, (3) cross-cultural sensitivity and (4) interaction of medicine and supporting disciplines, for example, anthropology, engineering, healthcare administration, agriculture, etc.,—can be used to guide curriculum development. |

| 2014 | 45 | Aluttis et al | Worldwide improvement of health, reduction of disparities, and protection against global health threats (The European Commission, 2009). |

| 2014 | 95 | Haines & Berlin | The term ‘global health’ describes the phenomenon of determinants of health transcending national boundaries due to unprecedented growth in international travel, global trade and investment, and an increased flow of information and technology having a pervasive impact on the determinants of health, the spread of disease and the functioning of health systems |

| 2014 | 31 | Kuhlmann | (T)he term ‘global health’ seeks to convey that health issues are universal, that health issues transcend national boundaries, and that diseases can and often do spread quickly (and often without respect for political boundaries) |

| 2014 | 60 | Nascimento et al | Global Health, formerly ‘International Health’, involves numerous aspects of health policies, epidemiology, prevention, diagnosis and therapy for neglected diseases and is not restricted to low resource regions. It is supported by four main bases: (A) clinical decision based on data and evidence; (B) population-based rather than individual focus; (C) social goals; (D) preventive rather than curative care. |

| 2014 | 91 | Rowthorn and Olsen | Global health is by definition and necessity a collaborative field; one that requires diverse professionals to address the clinical, biological, social and political factors that contribute to the health of communities, regions and nations. |

| 2014 | 43 | Steeb et al | Similar to public health, global health focuses on preventive measures, population-based care and health equity, including social and economic determinants of health. |

| 2015 | 26 | Engebretsen and Heggen | By adding ‘global’ to ‘health’, we presume that there is a universal health standard. Thus, global health both alludes to supranational dependency within the health field and refers to a norm or vision for health with global ambitions. It implies a homogenisation of a world view of health with someone in the role as Cosmotheros (world viewer). |

| 2015 | 87 | Gostin and Friedman | Global health entails ensuring the conditions of good health—public health, universal health coverage and the social determinants of health—while justice requires closing today’s vast domestic and global health inequities. |

| 2015 | 35 | Marten | Whereas public health acknowledges the state as a dominant actor, global health recognises the rise of other actors like international institutions, civil society and the private sector affecting health and health policies transcending states. |

| 2016 | 21 | Benatar | Global health, appropriately understood as an ecocentric concept, embraces the idea of healthy people on a healthy planet. This notion goes beyond anthropocentric considerations on health to include the importance of the interconnectedness of all life-forms and human well-being on an ecologically threatened planet. |

| 2016 | 67 | Wernli et al | We propose here a definition of global health based on six core principles: (1) cross-border/multilevel approach, (2) interdisciplinarity/transdisciplinarity, (3) systems thinking, (4) innovation, (5) sustainability and (6) human rights/equity. |

| 2016 | 68 | Wilson et al | We define global health as health problems, issues and concerns that transcend national boundaries, may be influenced by circumstances or experiences in other countries and are best addressed by cooperative actions and solutions. |

| 2018 | 75 | Havemann and Bösner | Global health comprises aspects of (tropical) medicine, international health, public health and other disciplines. Additionally, it includes global aspects in the sense of ‘global as supraterritorial’. |

| 2018 | 28 | Horton | Global health is not about equity. It is about power. |

| 2018 | 59 | Mews et al | The following three core elements form a working definition of global health and constitute an innovative and necessary perspective for medical education: health as a human right; global perspective; interdisciplinarity |

Several scholars engaged directly with the Koplan et al definition of GH1 to stipulate definitions of their own. For example, some authors proposed amendments to Koplan et al that would place greater emphasis on inequity reduction and the need for collaboration,20 particularly with institutional partners from developing countries.73 Others were more critical of the broad yet weak conceptual idealism86 of Koplan et al and recommended detaching normative objectives from its definition,26 such as the value-laden concept of equity, which could compromise the definition’s technical neutrality by rendering it ideological.91 Other authors sought to analytically clarify the meaning of ‘the global’26 in the definition provided by Koplan et al, distinguish it more clearly from IH78 or dispute their distinction between GH and PH.27 Indeed, the impact of the definition of GH proposed by Koplan et al has been substantial. It was variously adopted by the Consortium of Universities for Global Health,47 the Canadian government,23 Global Health for Family Medicine,89 the German Academy of Sciences75 and the Chinese Consortium of Universities for Global Health.77

In general, GH was defined as a term,37 51 95 and in particular, an umbrella term49 75 or a concept;69 and more broadly as a zone76 or field32 48 91 94 or area of research and practice,1 56 as an achievable goal,50 an approach,48 82 a set of principles,45 83 an organising framework for thinking and action96 or a collection of problems.35 94 GH was frequently contrasted to IH32 35 68 69 94 95 and PH,20 21 31 32 35 or else seen as indistinguishably from PH and IH.27 Additionally, several papers explicitly specified and subsequently defined certain dimensions of GH, such as ‘global health governance’ (GHG),32 33 35 38 42 51 52 58 69 80 81 87 ‘global health diplomacy’ (GHD),24 28 95 ‘global health education’,36 39 46–49 59 70 74 75 77 78 82 89 93 ‘global health security’,26 41 76 88 92 97 98 ‘global health network’,41 81 ‘global health actor’,52 ‘global health ethics’,69 ‘global health academics’64 67 and ‘global health social justice’61 (see table 3).

Table 3.

Frequently defined facets of ‘Global Health’ with exemplary definitions

| Defined dimensions of global health (GH) | No. of publications defining this dimension | One exemplary definition for each dimension |

| GH governance | 12 | Global health governance refers to ‘trans-border agreements of initiatives between states and/or non-state actors to the control of public health and infectious disease and the protection of people from health risks or threats’, it involves multilateral and bilateral agencies, scientific and public health epistemic communities, private philanthropists, the private sector and public–private initiatives, and a range of community and international non-governmental organisations.52 |

| GH diplomacy | 3 | There is also growing activity in the field of global health diplomacy which ‘brings together the disciplines of public health, international affairs, management, law and economics and focuses on negotiations that shape and manage the global policy environment for health’. It encompasses interdisciplinary study of the two-way relationship between diplomacy and foreign policy on the one hand and health on the other and promotes education of diplomats in global health together with educational initiatives to improve mutual understanding with a special focus on the negotiation process—particularly the interface between technical and political issues that arise in global health agreement.95 |

| GH education | 14 | We propose an accepted definition of paediatric GH tracks as ‘a longitudinal area of concentration dedicated to global child health, offered within a residency program, which includes a formal curriculum and mentorship with required scholarly output for a defined cohort of pediatric residents’.74 |

| GH security | 6 | The WHO defines global health security as: The activities required, both proactive and reactive, to minimise vulnerability to acute public health events that endanger the collective health of national populations, as well as collective health of populations living across geographical regions and international boundaries.41 |

| GH network | 2 | Global health networks are webs of individuals and organisations linked by a shared concern to address a condition that affects or potentially affects a sizeable portion of the world’s population.41 |

| GH actor | 1 | Accordingly, a global health actor is defined as an individual or organisation that operates transnationally with a primary intent to improve health.54 |

| GH ethics | 1 | A new shared paradigm for global health ethics would increase capacity for all decision-makers involved in global health research and practice by combining moral and scientific starting points for research with a more comprehensive relationship model inclusive of solidarity and social justice.69 |

| Academic GH | 2 | We propose the following definition of academic global health: within the normative framework of human rights, global health is a system-based, ecological and transdisciplinary approach to research, education and practice which seeks to provide innovative, integrated and sustainable solutions to address complex health problems across national boundaries and improve health for all.67 |

| GH social justice | 1 | Defining attributes of social justice in global health include (a) equity in opportunity for health, and (b) caring and cooperative societal relationships.61 |

Grounded theory approach based on thematic analysis

Definitions and descriptions of GH were aggregated into nine thematic codes reflecting the contents and scope of GH definitions, the functionality of those definitions and/or perceptions about defining GH. Codes were: (1) GH is a domain of research, healthcare and education, (2) GH is multifaceted (disciplinary, sectoral, cultural, national), (3) GH is rooted in a commitment to equity, (4) GH is a political field comprising power relations, (5) GH is problem-oriented, (6) GH transcends national borders, (7) GH is determined by globalisation and international interdependence, (8) conceptually, GH is either similar or dissimilar to PH, IH and TM and (9) GH is perceived as definitionally vague.

These codes were grouped selectively into higher analytical categories or theoretical statements as grounded in the literature: (1) GH is a multiplex approach to worldwide health improvement and form of expertise taught and researched through academic institutions, (2) GH is an ethos (ethical orientation and appeal) that is guided by justice principles, (3) GH is a mode of governance that yields degrees of national, international, transnational and supranational influence through political decision-making, problem identification, the allocation and exchange of resources across borders, (4) GH is a polysemous concept with many meanings and historical antecedents, and which has an emergent future (table 4).

Table 4.

Defining global health with grounded theory analysis—table of themes, code categories and quotes from text

| Key emergent themes |

Selective codes |

Quotes from literature |

| Global health is a multiplex approach to worldwide health improvement and a form of expertise taught and pursued through research institutions | Research, healthcare, education multi- (disciplinary, cultural, sectoral, national) |

‘Global health remains a diffuse and highly diverse arena of scholarship and practice’56 ‘Because global health is composed of, and relies on, multiple disciplines and sectors of society—which work from different languages, values, motivations and perspectives—it is important that at the very least there be a clear communication of what each actor is referring to when they use the term global health’23 ‘The term Global Health has become increasingly used over the last decade; while some debate remains about its meaning and how it has emerged, there is a growing consensus that it applies to the health needs of all the people on the planet and the socioeconomic frameworks that influence these’37 |

| Global health is an ethical initiative that is guided by justice principles | Values of equity and social justice | ‘The goal of global health is to improve health and achieve equity in health for all people worldwide’77 ‘These (global health principles) can be summarized as health for all people, through health by all actors, and health in all policies’86 ‘More today than ever, global health is in need of a renewed ethic, the ethic of universal rights, so that every human being may have an opportunity to achieve his or her full potential’66 |

| Global health is a mode of governance that yields influence through political decision-making, problem identification, the allocation and exchange of resources across borders | Power and politics, identifying problem and solutions, transcends national borders, globalisation, and international interdependence | ‘At the bottom line: “global health”, research, education and practice are nested in a highly “politicised” environment, locally as well as supraterritorially. All areas accommodate their own, but interdependent political economy’22 ‘A strong internal frame unifies the policy community through an agreed-upon definition and cause of the problem as well consensus on the preferred solutions’29 ‘Unprecedented growth in international travel, global trade and investment and an increased flow of information and technology are having a pervasive impact on the determinants of health, the spread of disease and the functioning of health systems. As a consequence, it is increasingly recognised that many determinants of health transcend national boundaries and the term “global health” is increasingly used to describe this phenomenon’95 |

| Global health is a vague yet versatile concept with historical antecedents and an emergent future | Dis/similar to PH, IH and TM; literally defined as ‘vague’ and/or in need of further definition | ‘The term global health is relatively new and overlaps with the preexisting fields of international health, public health, and tropical medicine’57 ‘There are multiple expressions of global health in the international literature, and it is useful to review selected examples, because they call attention to diverse dimensions of global health.’64 ‘There has been a tremendous amount of discussion about global health without rooting the term itself to a common definition. Countless books and journal articles have been written and university programs have been designed around global health without a definition of the term. There are numerous examples of work being done in this field without a clear definition in place. Indeed, it is often not clear how people and organizations engaged in global health are using the term’23 |

IH, international health; PH, public health; TM, tropical medicine.

Theme: global health is a multiplex approach to worldwide health improvement taught and pursued through research institutions

Subtheme: GH is a domain of research, healthcare, education

GH was repeatedly defined as an active field of knowledge production that is composed of the following key elements: research, education, training and practice related to health improvement.1 20 21 23 32 33 35 38 40 44–49 52 55–58 61 63–69 72 74 75 77 78 80 82 90–92 94 Few authors defined GH as a new, independent discipline within the broader domain of medical knowledge,17 33 38 46 63 74 80 82 90 and some outlined discipline-specific competencies that were considered integral to the definition of GH, at least in curriculum development; for example: clinical literacy,80 medical humanities,82 cross-cultural sensitivity,33 38 46 59 63 80 90 experiential learning47 and critical thinking skills.72 82 Several authors defined GH as a diffuse arena of scholarship that spans an array of academic disciplines, including anthropology, engineering, law, agriculture and healthcare administration.44 56 59 63–65 78 91 94 Others defined GH explicitly as a ‘transdiscipline’ that seeks to transcend the restricted gaze of any single discipline and consequently integrate knowledge from a variety of sources.67 94 Several authors explicitly defined GH as a necessarily collaborative field.1 20 22 24 36 43 45 47 57 61 63 68 77 78 80 91

Subtheme: GH is multifaceted (disciplinary, sectoral, cultural, national)

The prefix ‘multi-’ was consistently applied in definitions of GH to describe a perspective that focuses on the multitude of interrelated factors, dimensions, values and features that underpin health as well as efforts to improve and study it. There was broad agreement that multidisciplinarity is a defining characteristic of GH.1 23 25 32–34 36 38 40 45–47 49 52 55–57 59 60 64–69 72 75 77 78 80 82 91 However, there was some debate whether multiple disciplines are always needed and beneficial—and therefore essential—to the definition of GH.23 One author argued that the multidisciplinary nature of GH is precisely what differentiates it from PH and IH.68 Although some claimed that GH, with its focus on social and economic determinants, is inherently ‘predisposed to include aspects of the liberal arts and social sciences’,75 others critically observed that most GH educational opportunities still cater predominantly to medical students,32 35 48 72 which suggests that greater efforts will be required to achieve multidisciplinarity in the field moving forward.

There was a correspondence between GH definitions citing multidisciplinarity and cultural competency.32 33 38 48 49 56 78 82 90 Curiously, multisectorality was less frequently mentioned than multidisciplinarity in definitions of GH, though it was referenced in some papers.20 22 43 52 66 83 86 95

Theme: global health is an ethical initiative that is guided by justice principles

Subtheme: GH is rooted in values of equity and social justice

Equity and social justice were the two most commonly and explicitly referenced values undergirding GH definitions and goals. Equity was repeatedly framed as a ‘main objective’60 and core component of GH research and practice.23 25 43 46 48 53 66 67 77 78 84 However, it remains unclear whether the authors in our sample share the same meaning of equity. Velji and Bryant defined equity broadly as ‘ensuring equal opportunities and resources to enable all people to achieve their fullest health potential’.66 Meanwhile, others rooted their conceptualisation of equity more specifically in the principles of social justice30 61 69 88 89 or the human rights concept of equality,54 62 67 83 86 which asserts that ‘all people are equal in regard to dignity and rights, regardless of their origin and all biological, social or other specific differences’.59 This postwar sensibility echoes the 1978 Alma Ata Declaration of ‘health for all’,20 24 as well as a traditional humanitarian ideal, even if now associated with principles grounded in national and global security.24 54 88

Occasionally, the terms ‘equity’ and ‘equality’ were used interchangeably, suggesting they possess a commonly shared valence and reciprocal relationship despite slight differences in signification. Whereas equity refers to the provision of resources and opportunity based on specific needs, equality connotes providing the same level of resources and opportunities for all.86 Nevertheless, other scholars questioned whether equity or equality should be included in official definitions of GH, at all,27 48 75 insofar as what counts as ‘equitable’ for one country may be different for another.26 32 48

Theme: global health is a form of governance that yields national, international, transnational and supranational influence through political decision-making, problem identification, the allocation and exchange of resources across borders

Subtheme: GH is a political field comprising power relations at multiple scales

Numerous papers defined GH as embedded within a political field comprising power relations at multiple scales.20 22–24 26 28 29 31–33 35 41 42 45 48 51–54 56 58 60 63 66 70 72 76 79 87 95 ‘Political field’ refers here to a sphere of influence and jurisdiction wherein institutions determine governing modalities (eg, laws, policies, instruments) to assure a range of activities, such as determining priorities, coordinating stakeholders, regulating funding mechanisms, establishing accountability, allocating resources and providing access to health services for the general public. ‘Power relations’ refers to the capacity of institutions, individuals, instruments and ideas to affect the actions of others; and ‘at multiple scales’ refers to levels of analysis (ie, worldwide, regional, national, local, etc.).

Within the literature on GHG and GH security, authors argued the need for a universal definition of GH to shape policy frameworks that ensure compliance with IH law.32 45 51 88 95 Here, it is important to note that the ability to shape GH policy is, itself, an exercise in power: some GH actors, defined as ‘individuals or organizations that operate transnationally with a primary intent to improve health’,56 are more capacitated than others to impact the formulation of policies and amount of attention and resources that certain GH issues receive.32 41 45 52 95 For example, several papers discussed how ‘GH actors’ like the World Bank and the WHO shaped discussions around the response to Ebola, leading to refined definitions of GHG35 87 88 and GH security.41 Similarly, definitions of GH in line with the 2015 United Nations Millennium Development Goals, were also commonly referenced,25 35 45 51 reflecting the influence of certain GH actors on the conceptualisation of GH.

Subtheme: GH is determined by globalisation and international interdependence

Numerous authors linked interdependence and accelerating globalisation (the process of integrating governments and markets, and of connecting people worldwide) with the need for a cohesive definition of GH, particularly to address issues of governance.24 32 35 45 68 88 GHG and GHD were outlined as two influential subdomains in which the interconnections between globalisation, foreign policy and international relations were viewed as indispensable to definitions of GH. Two articles quoted David P Fidler’s definition of GHG as ‘the use of formal and informal institutions, rules, and processes by states, intergovernmental organizations, and nonstate actors to deal with challenges to health that require cross-border collective action to address effectively’.35 58 Elsewhere, GHD was described as ‘bringing together the disciplines of public health, international affairs, management, law and economics and focuses on negotiations that shape and manage the global policy environment for health’.95

Subtheme: GH issues transcend national borders

Across several papers, we observed a common refrain that GH ‘crosses borders’ and ‘transcends national boundaries’.1 20 23 42 45 52 60 67 68 74 Authors frequently described GH concerns as those exceeding the jurisdictional reaches of any individual nation-state alone.34 42 45 51 52 54 77 95 One paper claimed that GH is ‘transnational by definition’,74 and others characterised GH problems as those experienced transnationally.20 32 48 50 68

Studies focusing on GH research and training frequently referenced specific diseases and health risks that ‘transcend national borders’ alongside parallel recommendations to include an international component in the development of GH curricula.16 48 49 63 74 93 While crossing national borders to research and promote health for all is widely perceived as an historical condition for GH24 that has led to GH’s emergence as an academic discipline,63 several scholars argued that GH should also focus on domestic health disparities1 27 38 46 and for local issues to be simultaneously understood as universal or worldwide48 74 75 to the extent they may occur anywhere22 and are almost always impacted by global phenomena.56

Subtheme: GH is problem-oriented

Medical anthropologists, Arthur Kleinman and Paul Farmer, described GH as a collection of problems rather than a distinct discipline.35 94 Several authors in our review delineated GH problems through identification of specific diseases, such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, TB, Zika and Ebola.24 29 30 35 45 83 Lee and Brumme noted that it has become common for experts to define GH problems by identifying their objects, namely diseases, population groups and locations.58 Indeed, some authors outlined GH problems as the set of challenges ‘among those most neglected in developing countries’,86 among them: emerging infectious diseases and maternal and child health;43 65 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and other noncommunicable diseases in ‘local’ communities25 63 and even neurological disorders among refugees arriving in Europe.93 How these types of object-based definitions of GH problems come to shape GH agendum is important to note.

Clark made a compelling argument against the definition of GH problems in terms of specific diseases, writing that such ‘medicalisation’ may ‘prove detrimental for how the world responds and resources actions designed to alleviate poor health and poverty, redress inequities, and save lives’.72 Brada also argued against defining GH problems geographically and instead urged experts to consider how the processes by which GH and its quintessential spaces, namely ‘resource-limited’ and ‘resource-poor settings’, are actively constituted, reinforced and contested.70 Several authors similarly suggested that focusing on the social, political, economic and cultural forces contributing to health inequity and diseases of poverty better captured the scope of GH problems than naming any particular set of diseases or places in the world.33 43 56 58 69 72 73 86 92

Lack of consensus regarding what counts as a ‘true’ GH problem was linked to the lack of a clear and concise definition of GH. Indeed, several scholars argued that the current inability to define GH made it difficult for stakeholders to define precisely what the ‘problem’ is.44 45 48 86 Furthermore, the diagnosis of GH problems determined what types of GH ‘solutions’ were proposed in response. For example, when GH problems were defined as universally shared and transnational, then cross-border solutions were developed; when GH issues were framed epidemiologically in terms of distributed risk, then actions targeting specific determinants and burdens were proposed.1 20 23 67 68 92 When GH problems were framed as threats to inter/national security, strategies were formulated to protect borders, economies, health systems and to improve surveillance mechanisms.41 45 54 76 80 88 When the problem of inequality drove definitions of GH, recommendations to alleviate poverty, food insecurity, poor sanitation, etc. were proposed.32 53 60 72

Although Kuhlmann suggested that GH tends to over-prioritise problem-identification to the detriment of critical solution-oriented work,31 our analysis suggests that the type, scope and quality of solutions proposed are contingent on the elaboration of problems. Similarly, Campbell wrote, ‘Unlike a science or an art, the field of global health is very much about providing solutions to current problems. As such, it would be short-sighted not to consider the causes of global health problems in order to better formulate the solutions. The causes ought to be included in a comprehensive and complete definition of the field’.23

Theme: global health is a polysemous concept with historical antecedents and an emergent future

Subtheme: GH is conceptually dis/similar to PH, IH and TM

GH was consistently traced back to and compared with PH, IH and TM.1 20 27 32–34 43 57 69 71 75 84 86 88 Disagreement or confusion regarding the degrees of similarity and difference between these domains seemed to stem from a shared understanding that GH, in fact, evolved to a varying degree from each of these fields and does not, therefore, denote a clear-cut break with nor full-blown departure from any of them.84 94

Several authors argued that the scope and scale of GH is distinct from PH.1 20 32 69 71 Some argued that ‘public health is equated primarily with population-wide interventions; global health is concerned with all strategies for health improvement,’ including clinical care;20 and that ‘public health acknowledges the state as a dominant actor, (while) global health recognizes the rise of other actors like international institutions’.35 GH was also seen as placing a greater emphasis on multidisciplinarity and promoting a more expansive conceptualisation of ‘health’, itself, compared with PH.69 Beyond the prevention of and response to biomedicalised health risks at the population level, Rowson defined GH as oriented towards the ‘underlying determinants of those problems, which are social, political and economic in nature.’32 It is questionable, however, to assume similar notions of health have not also been pursued in PH. Meanwhile, opposing views found GH and PH conceptually indistinguishable,27 43 86 either as terms that could be used interchangeably,95 or else as coconstitutive of one another, such that PH could be understood as a descriptive component of GH.33 86

Differences between GH and IH echoed those drawn between GH and PH. For example, GH was characterised as more attentive to multidisciplinarity, while IH was said to implement a more limited biomedical approach to healthcare and health research.1 69 95 Undergirding a major point of distinction between GH and IH was the belief that IH focuses on health problems in developing countries1 22 32 43 45 48 54 83 86 93 and relies on ‘the flow of resources and knowledge from the developed to the developing world’,32 whereas GH either is, or should be, more bidirectional.1 45 84 In other cases, GH was described as comparable to IH, for example, when countries link GH efforts with development aid.86 This is because the emphasis on delivering aid to poor countries reinforces an image of the world’s poor as needy subjects and, therefore, marks a continuation of IH and its sentiments under the guise of GH.35

Finally, the field of TM was referenced to describe the evolutionary track of GH, particularly that GH is a modern-day product of the former.20 25 57 69 75 84 A few authors critically pointed out that although GH has generally replaced TM and IH as terms embedded in histories of colonial power relations, many of the contemporary structures for governing and/or facilitating GH between countries today have remained largely the same,25 48 54 62 suggesting that distinguishability between these terms too often occurs at the level of semantics.

Subtheme: GH is still vaguely defined

While GH was often described as a popular and well-established term, another key attribute repeated across the literature was its enduring vagueness.23 25 26 31 33 43 45 48 52 62 74–77 81 86 Indeed, most papers commented on the term’s defiance of easy definition, its ambiguity and the lack of clarity regarding how people and organisations engaged in GH are using (or not using) the term to describe their interests. For example, Beaglehole and Bonita pointed out that research centres in low-income and middle-income countries are often engaged in GH issues but under other labels.20 Some authors viewed the present lack of a clear and common definition as an obstacle endangering the coherence and maturation of the field.33 35 45 For others, this indistinctness was thought to be precisely what gives GH such wide applicability, a certain degree of currency and political expediency.45 76 81 86

A major concern cited was the lack of guidance for defining the term ‘global’ in GH.26 34 43 48 75 As Bozorgmehr has outlined, the term is often used interchangeably within the GH community to mean ‘worldwide’, ‘everywhere’, ‘holistic’ and/or ‘issues that transcend national boundaries’.48 This trend was noticeable within our review, as well. Engebretsen emphasised that GH ‘does not only allude to supranational dependency within the health field, but refers to a norm or vision for health with global ambitions’.26 This view suggests that because the planet is populated by a multiplicity of positionings, perspectives and diverse world views, there can never be a truly a universal definition of ‘the global’ nor a global consensus around the definition of GH.

Finally, among studies that conducted original research into the definition of GH, several reported that study participants could not reach consensus on a definition.52 74 75 77 Many thought it would be difficult if not impossible to arrive at a single, unified theoretical definition of GH, yet considered it important to formulate an operational definition of GH for guiding emerging activities related to GH.23 45 77

Discussion

This is the first study to systematically synthesise the literature defining GH and analyse the definitions found therein. All of the articles included in this study were published in peer-reviewed journals since 2009 indicating recent and steadfast interest in the topic of GH’s definition. This review examined GH definitions in the literature, and our thematic analysis focused on identifying recurrent themes across different definitions of GH.

Of the 78 articles included in this study, approximately one-third utilised empirical research methodologies to posit definitions of GH or else directly contribute towards the establishment of a common definition. Another one-third of papers summarised and discussed previously published definitions of GH (eg, reviews/overviews), while the remaining one-third suggested definitions of GH that were less grounded in analysis of empirical data than in the perspectives of its authors (eg, editorials, viewpoints). This systematic analysis indicated that the question of GH’s precise definition marks a point of controversy across fields of expertise. The variety of GH definitions posited by diverse experts in search of a common definition indicate that GH is multifaceted and polysemous.

In its broadest sense, GH can be defined as an area of research and practice committed to the application of overtly multidisciplinary, multisectoral and culturally sensitive approaches for reducing health disparities that transcend national borders. Indeed, it was most commonly defined across the literature in such general terms.

More specific definitions of GH were, of course, proposed by and considered valuable for many stakeholders in our review. Our analysis indicates that the precise definitions proposed by different experts were devised to serve particular functions. For example, narrow and concise definitions of GH were most frequently sought in the domains of governance and education, primarily for steering the development of policy frameworks and curricula, respectively. The imperative for an exact definition of GH in these subfields may be linked to bureaucratic demands for demarcating a technical term under which to classify specific activities, standardise certain functions, administer funds and direct workflow accordingly. It is also in this domain that authors most vociferously decried the absence of a unified and concise definition of GH, arguing this lack has led to ineffective initiatives, elusive methods for establishing accountability and instances of resource allocation based on ad hoc criteria—attractiveness to donors, public opinion, development agendum, foreign, economic or security policy priorities and so on—rather than via transparent mechanisms for adjudicating health need.28 54 58 65 83 In contexts where health needs and upstream challenges were articulated, the lack of an agreed-upon definition oft impeded the policy process because stakeholders could not discern which GH issues among the multitude of different problems labelled as important were, in fact, the most pressing.24 45 52 Because political indecision ramifies disproportionately for publics in countries where reliance on GH aid is a matter of life and death, establishing a clear definition of GH seems most crucial for the domain of governance.

We also found that detailed descriptions of GH’s specific conceptual and functional dimensions tended to reflect the specialisations or discipline-specific priorities of their authors. For example, definitions of GH stipulating the primacy of ‘cultural competency’ and ‘multidisciplinarity’ were more commonly proposed by interdisciplinary professionals in the literature on GH education than in journals of health policy, where definitions of GH were oriented more toward ‘security’ and ‘governance’ concerns. This suggests a correspondence between the subjective, experiential positions of the definers and the vocabulary they used to define or frame the need to define GH.

Unsurprisingly, we found that health professionals proposed the majority of definitions of GH in the literature. Additionally, the majority of publications and their authors were from higher income countries. Several authors in our review critically observed that GH has become institutionalised at a faster rate in higher income countries compared with lower and middle-income countries.20 48 63 72 77 82 Their observations combined with our findings suggest that extant definitions of GH published in the literature or otherwise circulating in academic and professionalised spaces may unevenly reflect the interests and priorities of stakeholders from higher income countries. This suggests a need for greater diversity and inclusion in the debate on GH’s definition, as well as further reflexivity regarding who is defining GH, their means and motivations for doing so, and what these definitions put into action.

Interestingly, several articles published since 2019 have extended the debate on this topic of GH’s definition by directly engaging questions of geography and positionality: a recent commentary by King and Kolski defining GH ‘as public health somewhere else’ was met with pushback by those who argue that spatial definitions of GH are limited and limiting.99–102

Limitations

To determine how GH is defined by experts in the literature, we ensured that the selection criteria developed for this study were broad enough to include a wide range of perspectives. Therefore, we included articles with varying degrees of evidentiary support, such as viewpoints, commentaries and editorials. Consequently, the results may be influenced by some of the primary researchers’ assumptions, projections, and biases. Backward citation tracking was used to add relevant articles to the review that had not been initially identified through database searching. This ensured that the review was exhaustive, however it also means that some conclusions drawn in the thematic analysis may have been influenced by this manual search strategy. By applying qualitative methods, this review provided a robust analysis of the thematic categories undergirding extant definitions of GH. A major limitation of this form of analysis is the extensive time required to develop and establish a code book and standardise the three coders’ use of the code book. However, this was deemed necessary to ensure consistency of judgement and intercoder reliability at each stage in the analysis. Another limitation of this study is that only articles written in English were included. To enhance the generalisability of results, future reviews should include data from non-English articles, especially if an inclusive, common definition of GH is to be achieved. Finally, this review was finalised prior to the emergence of the novel coronavirus. As such, future research should take into account new definitions of GH that emerge in light of the pandemic and lessons learnt.

Conclusion

Between 2009 and 2019, GH was most commonly defined in the literature in broad and general terms: as an area of research and practice committed to the application of multidisciplinary, multisectoral and culturally sensitive approaches for reducing health disparities that transcend national borders. More precise definitions exist to serve particular functions and tend to reflect the priorities of its definers. The four key themes that emerged from the present analysis are that GH is: (1) a multiplex approach to worldwide health improvement taught and researched through academic institutions; (2) an ethos that is guided by justice principles; (3) a mode of governance that yields influence through political decision-making, problem identification, the allocation and exchange of resources across borders and (4) a polysemous concept with historical antecedents and an emergent future. Findings from this thematic analysis have the potential to organise future conversations about which definition of GH is most common and/or most useful. Future discussions on the topic might shift from questioning the abstract ‘what’ of GH to more pragmatic and reflexive questions about ‘who’ defines GH and towards what ends.

Acknowledgments

Helpful comments by anonymous reviewers are acknowledged with thanks.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: MS initiated and designed the project. MS, MA and MM contributed to the implementation of the research, to the collection of data, analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript. PC supervised the project and provided feedback on the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

No data are available. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. n/a.

References

- 1.Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, et al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet 2009;373:1993–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macfarlane SB, Jacobs M, Kaaya EE. In the name of global health: trends in academic institutions. J Public Health Policy 2008;29:383–401. 10.1057/jphp.2008.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kickbusch I. The need for a European strategy on global health. Scand J Public Health 2006;34:561–5. 10.1080/14034940600973059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee K. Globalization and health: an introduction. Springer, 2003. Dec 9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain SC. Global health: emerging frontier of international health. Asia Pac J Public Health 1991;5:112–4. 10.1177/101053959100500202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dewey A, Drahota A. Introduction to systematic reviews: online learning module. Cochrane training, 2016. Available: https://training.cochrane.org/interactivelearning/module-1-introduction-conducting-systematic-reviews

- 7.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:e1–34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piper RJ. How to write a systematic literature review: a guide for medical students. In: National AMR, fostering medical research. 1, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mengist W, Soromessa T, Legese G. Method for conducting systematic literature review and meta-analysis for environmental science research. MethodsX 2020;7:100777. 10.1016/j.mex.2019.100777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carver JC, Hassler E, Hernandes E. Identifying barriers to the systematic literature review process. ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement; 10 Oct, 2013:203–12. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harmer A, Xiao Y, Missoni E, et al. 'BRICS without straw'? A systematic literature review of newly emerging economies' influence in global health. Global Health 2013;9:15. 10.1186/1744-8603-9-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bills CB, Ahn J. Global health and graduate medical education: a systematic review of the literature. J Grad Med Educ 2016;8:685–91. 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00774.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hau DK, Smart LR, DiPace JI, et al. Global health training among U.S. residency specialties: a systematic literature review. Med Educ Online 2017;22:1270020. 10.1080/10872981.2016.1270020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1:1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corbin J, Strauss A. Strategies for qualitative data analysis. basics of qualitative research. : Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publicating, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charmaz K. Coding in grounded theory practice. : Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publicating, 2006: 42–71. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publicating, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bazeley P. Computerized data analysis for mixed methods research. In: Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. 1, 2003: 385–422. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beaglehole R, Bonita R. What is global health? Glob Health Action 2010;3. 10.3402/gha.v3i0.5142. [Epub ahead of print: 06 Apr 2010]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benatar S. Politics, power, poverty and global health: systems and frames. Int J Health Policy Manag 2016;5:599–604. 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bozorgmehr K. Rethinking the 'global' in global health: a dialectic approach. Global Health 2010;6:19. 10.1186/1744-8603-6-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell RM, Pleic M, Connolly H. The importance of a common global health definition: How Canada’s definition influences its strategic direction in global health. J Glob Health 2012;2. 10.7189/jogh.01.010301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chattu VK. The rise of global health diplomacy: an interdisciplinary concept linking health and international relations. Indian J Public Health 2017;61:134–6. 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_67_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Cock KM, Simone PM, Davison V, et al. The new global health. Emerg Infect Dis 2013;19:1192–7. 10.3201/eid1908.130121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engebretsen E, Heggen K. Powerful concepts in global health: Comment on "Knowledge, moral claims and the exercise of power in global health". Int J Health Policy Manag 2015;4:115–7. 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fried LP, Bentley ME, Buekens P, et al. Global health is public health. Lancet 2010;375:535–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60203-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horton R. Offline: liberty vs equity in global health. Lancet 2018;391:1134. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30724-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnston BD. Injury prevention as a global health Initiative. 14. London, UK: BMA House, 2008: 145–6 10.1136/ip.2008.019265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jordan K, Marten R, Gureje O, et al. Where is quality in health systems policy? an analysis of global policy documents. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e1158–61. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30375-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuhlmann AS, Iannotti L. Resurrecting "international" and "public" in global health: has the pendulum swung too far? Am J Public Health 2014;104:583–5. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rowson M, Willott C, Hughes R, et al. Conceptualising global health: theoretical issues and their relevance for teaching. Global Health 2012;8:36. 10.1186/1744-8603-8-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Margolis CZ. Evaluating global health education. Med Teach 2013;35:181–3. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.758837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marten R, Kadandale S, Nordström A, et al. Shifting global health governance towards the sustainable development goals. Bull World Health Organ 2018;96:798–798A. 10.2471/BLT.18.209668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marten R. Global health warning: definitions wield power comment on "navigating between stealth advocacy and unconscious dogmatism: the challenge of researching the norms, politics and power of global health". Int J Health Policy Manag 2015;5:207–9. 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marušić A. Global health--multiple definitions, single goal. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2013;49:2–3. 10.4415/ANN_13_01_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piachaud J. Global health and human security. Med Confl Surviv 2008;24:1–4. 10.1080/13623690701775155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pitt MB, Moore MA, John CC, et al. Supporting global health at the pediatric department level: why and how. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20163939–3939. 10.1542/peds.2016-3939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quissell K. Additional insights into problem definition and positioning from social science comment on "four challenges that global health networks face". Int J Health Policy Manag 2017;7:362–4. 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ridde V. Need for more and better implementation science in global health. BMJ Glob Health 2016;1:e000115. 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shiffman J. Four challenges that global health networks face. Int J Health Policy Manag 2017;6:183–9. 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Speakman EM, McKee M, Coker R. If not now, when? time for the European Union to define a global health strategy. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e392–3. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30085-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steeb DR, Joyner PU, Thakker DR. Exploring the role of the pharmacist in global health. J Am Pharm Assoc 2014;54:552–5. 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.13251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tosun J. Polycentrism in global health Governance scholarship comment on "four challenges that global health networks face". Int J Health Policy Manag 2017;7:78–80. 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aluttis C, Krafft T, Brand H. Global health in the European Union--a review from an agenda-setting perspective. Glob Health Action 2014;7:23610–6. 10.3402/gha.v7.23610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arthur MAM, Battat R, Brewer TF. Teaching the basics: core competencies in global health. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2011;25:347–58. 10.1016/j.idc.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Battat R, Seidman G, Chadi N, et al. Global health competencies and approaches in medical education: a literature review. BMC Med Educ 2010;10:94. 10.1186/1472-6920-10-94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bozorgmehr K, Saint VA, Tinnemann P. The 'global health' education framework: a conceptual guide for monitoring, evaluation and practice. Global Health 2011;7:8. 10.1186/1744-8603-7-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crump JA, Sugarman J, Working Group on Ethics Guidelines for Global Health Training (WEIGHT) . Ethics and best practice guidelines for training experiences in global health. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010;83:1178–82. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010;376:1923–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haffeld JB, Siem H, Røttingen J-A. Examining the global health arena: strengths and weaknesses of a convention approach to global health challenges. J Law Med Ethics 2010;38:614–28. 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2010.00515.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harman S, Davies SE. President Donald Trump as global health’s displacement activity. Rev Int Stud 2019;45:491–501. 10.1017/S026021051800027X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heywood M. Drug access, patents and global health: ‘Chaffed and waxed sufficient’. Third World Q 2002;23:217–31. 10.1080/01436590220126603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoffman SJ, Cole CB. Defining the global health system and systematically mapping its network of actors. Global Health 2018;14:38. 10.1186/s12992-018-0340-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hunter A, Wilson L, Stanhope M, et al. Global health diplomacy: an integrative review of the literature and implications for nursing. Nurs Outlook 2013;61:85–92. 10.1016/j.outlook.2012.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Janes CR, Corbett KK. Anthropology and global health. Annu Rev 2010;38:167–83. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jogerst K, Callender B, Adams V, et al. Identifying interprofessional global health competencies for 21st-century health professionals. Ann Glob Health 2015;81:239–47. 10.1016/j.aogh.2015.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee K, Brumme ZL. Operationalizing the one health approach: the global governance challenges. Health Policy Plan 2013;28:778–85. 10.1093/heapol/czs127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mews C, Schuster S, Vajda C, et al. Cultural competence and global health: perspectives for medical education - position paper of the GMA Committee on cultural competence and global health. GMS J Med Educ 2018;35:Doc28. 10.3205/zma001174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nascimento BR, Brant LCC, Moraes DN, et al. Global health and cardiovascular disease. Heart 2014;100:1743–9. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nemetchek B. A concept analysis of social justice in global health. Nurs Outlook 2019;67:244–51. 10.1016/j.outlook.2018.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Šehović AB. Towards a new definition of health security: a three-part rationale for the twenty-first century. Glob Public Health 2020;15:1-12. 10.1080/17441692.2019.1634119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Steenhoff AP, Crouse HL, Lukolyo H, et al. Partnerships for global child health. Pediatrics 2017;140. 10.1542/peds.2016-3823. [Epub ahead of print: 20 Sept 2017]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.The International health regulations (IHR) – 10 years of global public health security. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2017;92:534–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van Belle S, Mayhew SH. What can we learn on public accountability from non-health disciplines: a meta-narrative review. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010425. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Velji A, Bryant JH. Global health: evolving meanings. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2011;25:299–309. 10.1016/j.idc.2011.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wernli D, Tanner M, Kickbusch I, et al. Moving global health forward in academic institutions. J Glob Health 2016;6:010409. 10.7189/jogh.06.010409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson L, Mendes IAC, Klopper H, et al. 'Global health' and 'global nursing': proposed definitions from The Global Advisory Panel on the Future of Nursing. J Adv Nurs 2016;72:1529–40. 10.1111/jan.12973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Benatar S, Daibes I, Tomsons S. Inter-Philosophies dialogue: creating a paradigm for global health ethics. Kennedy Inst Ethics J 2016;26:323–46. 10.1353/ken.2016.0027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brada B. "Not here": making the spaces and subjects of "global health" in Botswana. Cult Med Psychiatry 2011;35:285–312. 10.1007/s11013-011-9209-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brown T, Tim B. 'Vulnerability is universal': considering the place of 'security' and 'vulnerability' within contemporary global health discourse. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:319–26. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]