Abstract

Background

Whereas first-line bronchial artery embolisation (BAE) is considered standard of care for the management of severe haemoptysis, it is unknown whether this approach is warranted for non-severe haemoptysis.

Research question

To assess the efficacy on bleeding control and the safety of first-line BAE in non-severe haemoptysis of mild abundance.

Study design and methods

This multicentre, randomised controlled open-label trial enrolled adult patients without major comorbid condition and having mild haemoptysis (onset <72 hours, 100–200 mL estimated bleeding amount), related to a systemic arterial mechanism. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to BAE associated with medical therapy or to medical therapy alone.

Results

Bleeding recurrence at day 30 after randomisation (primary outcome) occurred in 4 (11.8%) of 34 patients in the BAE strategy and 17 (44.7%) of 38 patients in the medical strategy (difference −33%; 95% CI −13.8% to −52.1%, p=0.002). The 90-day bleeding recurrence-free survival rates were 91.2% (95% CI 75.1% to 97.1%) and 60.2% (95% CI 42.9% to 73.8%), respectively (HR=0.19, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.67, p=0.01). No death occurred during follow-up and no bleeding recurrence needed surgery.

Four adverse events (one major with systemic emboli) occurred during hospitalisation, all in the BAE strategy (11.8% vs 0%; difference 11.8%, 95% CI 0.9 to 22.6, p=0.045); all eventually resolved.

Conclusion

In non-severe haemoptysis of mild abundance, BAE associated with medical therapy had a superior efficacy for preventing bleeding recurrences at 30 and 90 days, as compared with medical therapy alone. However, it was associated with a higher rate of adverse events.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Massive Haemoptysis, Imaging/CT MRI etc, Bronchoscopy

Key messages.

To assess the efficacy on bleeding control and the safety of first-line bronchial artery embolisation (BAE) in patients with non-severe haemoptysis of mild abundance.

In non-severe haemoptysis of mild abundance, BAE associated with medical therapy has a superior efficacy for preventing bleeding recurrences at 30 and 90 days, as compared with medical therapy alone.

A first-line interventional radiology should be considered in the management of patients with haemoptysis, whichever its severity, bearing in mind the risk of adverse events associated with the procedure.

Introduction

Although rare, haemoptysis is a potentially life-threatening condition. In a recent 5-year French national study,1 haemoptysis accounted for 0.2% of all hospitalisations. Haemoptysis was associated with a substantial posthospital morbidity and health services consumption, in large part due to a 3-year bleeding recurrence rate of 16.3%, as well as with a high subsequent mortality rate of 21.6% and 27% at 1 and 3 years after the index hospitalisation.1

The therapeutic management of haemoptysis requires determining the most appropriate treatment, according to a rigorous assessment of the severity of haemoptysis, based on (1) the bleeding amount and the need for respiratory support, (2) the presence of comorbidities and (3) the cause and mechanism of bleeding.2 3 The therapeutic options may include medical measures,4–7 interventional radiology8 9 or emergency surgical lung resection.10–12 Bronchial artery embolisation (BAE) has gradually emerged as the first-line therapeutic measure in severe haemoptysis, achieving control of bleeding in 80%–90% of cases, with an acceptable risk:benefit ratio.9 13–15 Conversely, it is not known whether BAE is warranted in non-severe haemoptysis, whose prognosis may be less pejorative either spontaneously or with therapeutic interventions. In this context, the current therapeutic approach is guided by physicians’ preference integrating the risk:benefit ratio estimate and resources availability.

To date, no controlled study has compared the efficacy on bleeding control and the safety of a strategy using interventional radiology to medical therapy alone. The Arterio-embolisation in Hemoptysis of Mild Severity trial aimed to investigate the efficacy on the rate of bleeding recurrence of adding early first-line BAE to medical therapy in non-severe acute haemoptysis of mild abundance, as compared with medical therapy alone.

Methods

Study design and participants

The ARTEMHYS trial was an open-label multicenter, randomised controlled trial conducted in the intensive care unit (ICU) or intermediate care ward (ICW) of seven French university teaching hospitals.

Eligible patients were those presenting with non-severe acute haemoptysis of mild abundance, likely related to a systemic arterial mechanism. Acute haemoptysis of mild abundance was defined as an estimated cumulative bleeding amount ranging from 100 to 200 mL within 72 hours, using the following scale: a teaspoonful (5 mL), a spittoon (120 mL) and a large filled glass (200 mL).4 16 Non-severe haemoptysis was characterised by the absence of all of the following criteria related to (1) bleeding amount: acute respiratory failure with the need for mechanical ventilation; haemorrhagic shock, need for blood products transfusion, cardiac arrest; (2) bleeding aetiology or mechanism: mycetoma, pulmonary arterial vasculature involvement according to a pre-enrolment multidetector CT-angiography (MDCTA); and (3) severe baseline comorbid conditions: advanced chronic heart failure; chronic pulmonary disease (chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases Gold 3,3 17 pneumonectomy, tracheostomy, cystic fibrosis); chronic renal failure (creatinin clearance <30 mL/min or dialysis). Patients with the following conditions were also not eligible: traumatic haemoptysis; time to referral beyond 72 hours from bleeding onset; formal indication for anticoagulant therapy at therapeutic dosage; pregnant or lactating women, or patients having do-not-resuscitate order (moribund patient, life expectancy of <24 hours).2 4

Prior to enrolment, a MDCTA was required to identify the site, the cause and the mechanism of bleeding, and map the bronchial and non-bronchial systemic arteries.8

Randomisation and masking

Randomisation was performed within the first 16 hours of ICU/ICW admission, using a secure web-response system available in each study centre. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to BAE with medical therapy (interventional strategy) or medical therapy alone. Randomisation was stratified on centre and the permuted-block (different sizes of blocks) randomisation list was established by an independent statistician. Investigators had no access to the randomisation list and were blinded to the size of blocks.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of the research.

Interventions

Patients allocated to the interventional strategy received medical therapy as per current routine practice in each centre, in combination with BAE performed within 12 hours after randomisation, and at least 6 hours after intravenous infusion of terlipressin, if administered (online supplemental file). Those allocated to the medical strategy received medical therapy alone. Medical therapy included bed rest and fasting, continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, heart rate and arterial blood pressure in all patients regardless of the randomisation arm, as described elsewhere.4 The BAE procedure was performed by experienced radiologists and standardised in all centres.8 18

bmjresp-2021-000949supp001.pdf (85.9KB, pdf)

Outcomes

The percentage of bleeding recurrence at day 30 after randomisation was the primary efficacy endpoint, since two-thirds of bleeding recurrences occur within the month following initial management.4 Bleeding control was defined by bleeding cessation or bleeding of less than 50 mL during follow-up after the intervention, given that limited amount of bloody sputum that do not justify any additional therapeutic measure may be observed after effective initial management. Conversely, bleeding of 50 mL or more was considered as a failure of the intervention, as it would more likely lead to intensification or change in therapy. Patients allocated to the interventional strategy in whom the embolisation was technically impossible were also considered as failure.

The secondary endpoints were efficacy and safety endpoints: the rate of in-hospital adverse events related to the intervention, categorised into minor or major events (online supplemental file); the length of hospital stay; the percentage of bleeding recurrence at day 90 after randomisation; the 90-day rates of secondary hospitalisation or invasive interventions (BAE or surgery) for controlling bleeding recurrence after randomisation; and the overall death rates at 30 and 90 days after admission.

Statistical analysis

Assuming a bleeding recurrence rate of 26% at 30 days in the group treated with medical therapy alone,4 210 patients were needed to achieve 80% power to detect a 15% difference in the bleeding recurrence rate at 30 days between the two groups (ie, a reduction from 26% to 11% with BAE), considering a two-sided alpha of 5% and an expected dropout rate of 2%. Given the expected recruitment in each centre, the study was initially planned for 27 months’ duration, including a 3-month follow-up period.

Baseline characteristics were reported using frequencies and percentages or median and IQRs. The primary outcome was compared using Pearson χ2 test in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, including all patients randomised who did not withdraw consent. Patients with missing outcome data at day 30 were considered as failure in both groups, as well as patients for whom the embolisation was technically impossible in the intervention group. Those assumptions were adopted in a conservative approach to avoid favouring the intervention group. Sensitivity analyses were performed on the population with no missing primary outcome and on the per-protocol population, thus excluding patients with a missing primary outcome, or for whom the embolisation was technically impossible, as well as crossovers of the randomised strategy.

Bleeding recurrence at day 90 was analysed in the same way as the primary endpoint, including the aforementioned missing value dealing strategy. Other missing values were not replaced. A sensitivity analysis was performed on the per-protocol population. Time from randomisation to the first bleeding recurrence or to censoring was compared using a Cox proportional hazard model stratified by centre. Bleeding recurrence-free 90-day survival was represented using Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Ninety-day rate of rehospitalisation or invasive interventions for bleeding recurrence and in-hospital complications rate were compared using Pearson χ2 tests, and differences between groups were estimated with their 95% CI. Hospital length of stay was compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

All analyses were performed with the SAS V.9.4 statistical software. All tests were two-sided and a p value of less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance. No adjustment for multiple comparisons was made.

Results

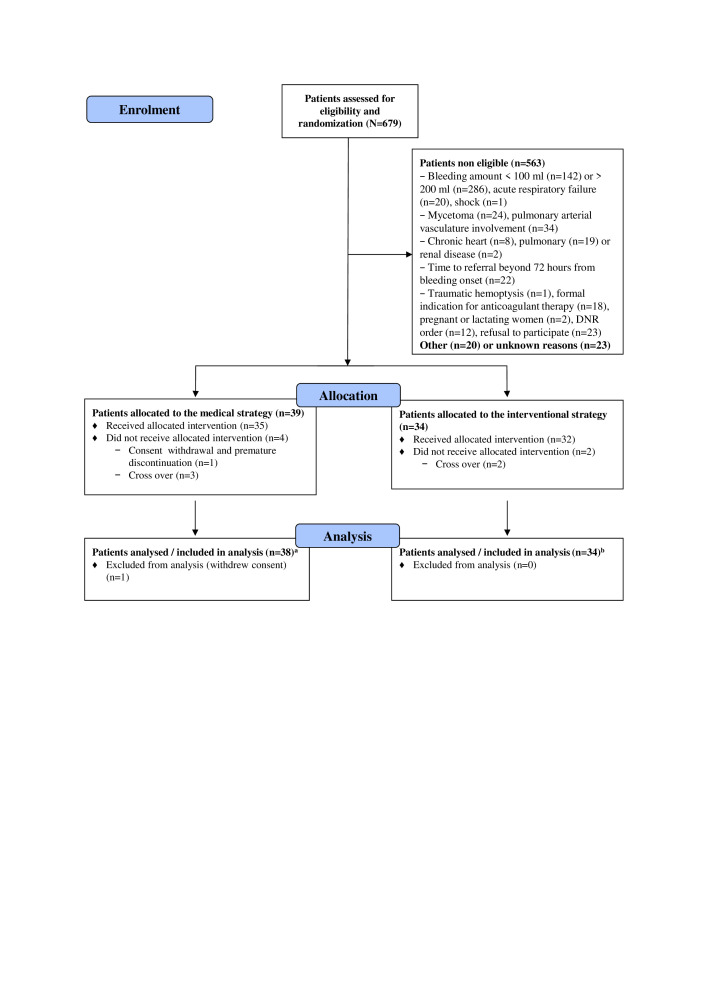

From 1 November 2011 to 30 November 2016, 679 patients with haemoptysis were screened in the participating centres; 606 (89%) patients were non-eligible, mostly (70%) because of bleeding amount outside of the targeted range (figure 1). Initially planned for 2 years, the study duration was extended by 2 years and terminated because of low enrolment rate and lack of additional funding after 73 patients had been randomised, with follow-up ending on 28 February 2017.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study population in the Arterio-embolisation in Hemoptysis of Mild Severity trial of medical management of mild-to-moderate haemoptysis with or without bronchial artery embolisation. aBleeding recurrence status was missing for two patients on day 30 (respective follow-up durations, 2 and 29 days) and for one other patient on day 90 (follow-up duration, 74 days); bbleeding recurrence status was missing for one patient on day 90 (follow-up duration, 67 days).

One patient withdrew consent immediately after randomisation and 72 patients were analysed, including 38 allocated to the medical strategy and 34 to the interventional strategy. Five crossovers occurred within groups: three (7.9%) patients in the medical strategy also received BAE during the 72 hours period after randomisation, whereas two (5.9%) patients randomised to the interventional strategy did not receive BAE (figure 1). In the primary ITT analysis, these crossovers were all analysed according to their randomisation group.

Characteristics of patients

Baseline characteristics did not differ between groups (table 1). Ground-glass opacities (37.5%) and alveolar consolidation (31.9%) accounted for the most frequent bleeding-related lung parenchymal findings on thoracic CT scan. The aetiology of bleeding was identified in 37 (51.4%) patients altogether and was dominated by bronchiectasis (25%) and active tuberculosis (5.6%) or tuberculosis sequels (8.3%); lung cancer accounted for only 5.6% of cases, and pneumonia or lung abscess accounted for 1.4%, with a similar distribution in both groups. Haemoptysis was cryptogenic in 48.6% of patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients enrolled in the Arterio-Embolisation in Hemoptysis of Mild Severity trial of first-line bronchial artery embolisation or medical therapy alone for management of mild acute haemoptysis

| Variable | Medical strategy (n=38) | Interventional strategy (n=34) |

| Age (years) | 54.5 (44–69) | 51.0 (40–66) |

| Sex (male) | 26 (68.4) | 25 (73.5) |

| Current smokers* | 23 (60.5) | 23 (69.7) |

| Never smokers | 11 (28.9) | 7 (21.2) |

| Referral from | ||

| Home | 3 (7.9) | 1 (2.9) |

| Emergency department | 28 (73.7) | 22 (64.7) |

| Out-of-hospital emergency services | 4 (10.5) | 6 (17.6) |

| Hospital ward | 3 (7.9) | 5 (14.7) |

| Performance status† | ||

| 0 | 25 (89.3) | 25 (86.2) |

| 1 | 2 (7.1) | 2 (6.9) |

| 2 | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.4) |

| 3 | 0 | 1 (3.4) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Pre-existing respiratory illness | ||

| At least one | 12 (31.6) | 13 (38.2) |

| Bronchiectasis | 4 (10.5) | 3 (8.8) |

| Lung cancer | 3 (7.9) | 1 (2.9) |

| Active tuberculosis | 2 (5.4) | 0 |

| Sequels of tuberculosis | 3 (7.9) | 7 (20.6) |

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Hypertension | 15 (39.5) | 9 (26.5) |

| Valvular disease | 1 (2.6) | 0 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 1 (2.6) | 3 (8.8) |

| Clinical physiological data during the first 24 hours of admission (minimal and maximal values) | ||

| Core temperature (°C)‡ | 36.6 (36.2–36.8) | 36.6 (36.3–36.9) |

| 37.1 (37.0–37.4) | 37.1 (36.9–37.4) | |

| Heart rate (beats/min)§ | 66 (57–80) | 69 (61–79) |

| 88 (77–97) | 86 (72–95) | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)¶ | 121 (105–134) | 125 (112–147) |

| 154 (138–171) | 160 (142–177) | |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min)** | 15 (14–20) | 15 (14–20) |

| 23 (20–30) | 25 (22–31) | |

| Pulse oxymetry (%)†† | 96 (93–97) | 95 (93–97) |

| 99 (98–100) | 99 (97–100) | |

| Bleeding on admission and persistence | ||

| Cumulated bleeding amount on admission (mL)‡‡ | 120 (110–150) | 150 (120–150) |

| Persistent bloody expectoration after admission§§ | ||

| Laboratory data on admission | 34 (91.9) | 27 (93.1) |

| Platelet count (giga/L)¶¶ | 233 (195–256) | 219 (184–258) |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL)*** | 13.7 (12.2–15.0) | 14.0 (12.5–15.1) |

| Prothrombin time (%)††† | 95 (84–100) | 97 (89.5–100.0) |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mmol/L)‡‡‡ | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L)§§§ | 67 (59–87) | 72 (64–1) |

Data are n (%) or median (IQR 25%–75%).

*Data are available for 71 patients (n1=38, n2=33).

†57 patients (n1=28, n2=29).

‡70 patients (n1=37, n2=33).

§71 patients (n1=38, n2=33).

¶70 patients (n1=37, n2=33).

**64 patients (n1=35, n2=29).

††68 patients (n1=36, n2=32).

‡‡71 patients (n1=38, n2=33).

§§66 patients (n1=37, n2=29).

¶¶70 patients (n1=37, n2=33).

***70 patients (n1=37, n2=33).

†††65 patients (n1=33, n2=32).

‡‡‡67 patients (n1=36, n2=31).

§§§70 patients (n1=37, n2=33).

Cointerventions

Supplemental oxygen was administered in 35 (49.3%) patients to obtain a pulse oxymetry of >90%. Bronchoscopic techniques were used in 32 (44.4%) patients, at a comparable rate in both groups (table 2). Intravenous terlipressin was administered at a dose of 1 mg every 4–6 hours to five and six patients in the medical strategy and interventional strategy, respectively, for a median total dosage of 2.5 (2.0–3.0) mg and 1.0 (1.0–1.0) mg, respectively.

Table 2.

Medical interventions performed in the medical or interventional strategy group

| Variable | Medical strategy (n=38) | Interventional strategy (n=34) |

| Medical treatment | ||

| None | 4 (10.5) | 11 (32.4) |

| Topical alone | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.9) |

| General alone | 16 (42.1) | 9 (26.5) |

| Both topical and general | 17 (44.7) | 13 (38.2) |

| Topical therapy* | ||

| Endobronchial suctioning | 18 (47.4) | 14 (41.2) |

| Chemical tamponade† | 4 (10.5) | 5 (14.7) |

| Mechanical tamponade‡ | 0 | 0 |

| General measures§ | ||

| Supplemental oxygen | 22 (57.9) | 13 (39.4) |

| Intravenous terlipressin | 5 (13.2) | 6 (18.2) |

| Cough suppression | 0 | 0 |

| Antimicrobial treatment | 15 (39.5) | 14 (42.4) |

Data are n (%).

*Topical measures performed using flexible fibreoptic bronchoscopy.

†Topical tamponade including cold saline solution lavage or epinephrine instillation.

‡Mechanical tamponade including bronchial blockers or Fogarty catheters at the segment or subsegment bronchial levels.

§Data are available for 71 patients (missing for one patient in the interventional strategy).

Primary outcome

At day 30, the bleeding recurrence status was unknown for two patients allocated to the medical strategy, with respective follow-up of 2 and 29 days (figure 1 and online supplemental e-Table 1). Altogether, the randomised strategy failed in 21 (29.2%) patients, including 17 (44.7%) of 38 patients in the medical strategy, and 4 (11.8%) of 34 patients in the interventional strategy (difference 33%, 95% CI 13.8% to 52.1%, p=0.002) (table 3). These results were consistent in the sensitivity analyses restricted to patients with available data (n=70, difference 29.9%, 95% CI 10.5% to 49.3%, p=0.005) and on the per-protocol population (n=63, difference 26.4%, 95% CI 6.7% to 46%, p=0.014).

Table 3.

Primary and secondary outcomes of patients

| Endpoints | Medical strategy (n=38) |

Interventional strategy (n=34) |

Absolute difference, % (95% CI) | P value |

| 30-day bleeding recurrence | 17 (44.7) | 4 (11.8) | 33.0 (13.8 to 52.1) | 0.002 |

| 90-day bleeding recurrence | 18 (47.4) | 5 (14.7) | 32.7 (12.8 to 52.5) | 0.003 |

| In-hospital complications rate | 0 | 4 (11.8) | 11.8 (0.9 to 22.6) | 0.045 |

| 90-day rate of rehospitalisation or invasive treatment for bleeding recurrence, n (%)* | 9/35 (25.7) | 2/32 (6.3) | 19.5 (2.7 to 36.2) | 0.032 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 4.0 (3.0–7.0) | 4.0 (3.0–9.0) | – | 0.75† |

| Mortality rate of 30 and 90 days‡ | 0 | 0 | – | – |

Data are n (%) or median (IQR 25%–75%).

*Analysis restricted to patients followed up to day 90. Bleeding recurrence status was missing at day 90 for four patients; invasive treatment was missing for one patient with bleeding recurrence during hospitalisation.

†Wilcoxon test.

‡Two patients in the medical strategy group were lost to follow-up at day 30 (at days 2 and 29, respectively); four other patients were lost to follow-up at day 90 (one patient in the medical strategy at day 74 and three patients in the interventional strategy at days 40, 48 and 67, respectively; see the online supplemental 2, e-Table 1). The mean/median duration of follow-up was 94.6±22.6 days/92 (90–99) days.

Secondary outcomes

The length of hospital stay did not differ among groups. No death occurred during follow-up (crude median duration 92 days, IQR 90–99.25) (table 3). At day 90, the bleeding recurrence status was unknown for two additional patients (one in each group, figure 1). Altogether, the treatment failed in 23 patients (31.9%). The percentage of bleeding recurrence was higher in the medical strategy than in the interventional strategy (47.4% vs 14.7%; difference 32.7%, 95% CI 12.8% to 52.5%, p=0.003) (table 3) and remained such in the per-protocol population (difference 27.5%, 95% CI 7.6% to 47.4%, p=0.012).

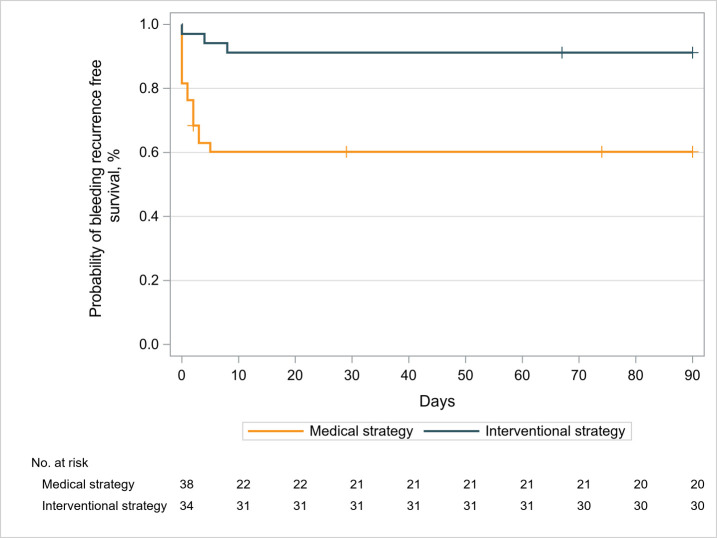

In the whole population, the 90-day bleeding recurrence-free survival rate was 74.9% (95% CI 63.1% to 83.4%). The risk of bleeding recurrence was more than fivefold lower in the interventional strategy than in the medical strategy (HR=0.19, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.67, p=0.01) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ninety-day bleeding recurrence-free survival after initiating therapy in patients with mild-to-moderately severe haemoptysis (Kaplan-Meier estimate). The 90-day bleeding recurrence-free survival rate was 91.2% (95% CI 75.1 to 97.1) in the interventional strategy and 60.2% (95% CI 42.9 to 73.8) in the medical strategy (HR=0.19, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.67, p=0.0101, by Cox proportional hazard model stratified by centre).

Failures of the intervention and management of recurrent bleeding episodes are detailed in online supplemental e-Table 1, together with the duration of follow-up. Five failures occurred in the interventional strategy, including one due to technical failure of BAE, one due to unknown status of bleeding recurrence, and three to recurrent bleedings, two of which required repeated BAE. Of the 18 failures in the medical strategy, 3 were due to unknown status of bleeding recurrence, and 15 were due to recurrent bleeding, 9 of which were treated with BAE. All documented recurrent bleedings (n=18) occurred during the first 8 days of the index hospitalisation. No hospital readmission occurred. None required emergent surgical lung resection. The rate of invasive treatment for bleeding recurrence (ie, BAE) in patients followed up to day 90 was 25.7% (9/35) in the medical strategy and 6.3% (2/32) in the interventional strategy (difference 19.5%, 95% CI 2.7% to 36.2%, p=0.032) (table 3).

The overall in-hospital complication rate related to the interventions was 5.6% (95% CI 1.8% to 14.4%). All adverse events (n=4) occurred in the interventional strategy (11.8% vs 0%; difference 11.8%, 95% CI 0.9% to 22.6%, p=0.045) and were considered to be related to the procedure (online supplemental eTable 2). Three patients (9%) had minor complications which resolved without further intervention; one patient (3%), however, had a paresis and several systemic emboli, which eventually resolved without long-term sequel.

Discussion

In this randomised trial, we aimed to investigate whether early first-line BAE had beneficial effects compared with medical therapy alone in the management of non-severe acute haemoptysis of mild abundance related to a systemic bronchial artery hypervascularisation. As compared with the medical strategy alone, the addition of early BAE achieved a higher efficacy in bleeding control at 1 and 3 months, but was associated with a higher rate of in-hospital complications.

The most difficult issues in the initial management of haemoptysis is to assess its severity and estimate the risk of bleeding recurrence, which condition the therapeutic decision and the time to its implementation. Life-threatening haemoptysis associated with high bleeding amounts, acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation or shock, which involve 10% of the patients with haemoptysis, mandate prompt management in an intensive care setting.1 2 In this context, the therapeutic management include the administration of inhaled or systemic vasoconstrictors or antifibrinolytic drugs, and the use of bronchoscopy-guided tamponade by flexible or rigid bronchoscope.7 19 The place of emergency surgery has gradually decreased because of high operative mortality rates,11 12 whereas interventional radiology has emerged worldwide as the most effective non-surgical first-line treatment, despite the lack of strong evidence from randomised trials. BAE results in immediate bleeding control in most of these severe cases with a satisfactory risk:benefit ratio.2 4 11 12 18

On the other hand, most patients presenting with mild-to-moderate haemoptysis are in the ‘grey zone’ of severity, considering the lack of usual severity criteria (bleeding amount or need for mechanical ventilation or vasopressors), although they unpredictably may progress to acute respiratory failure and ultimately die from massive bleeding recurrence.2 4 As a consequence, the most appropriate management of these patients at intermediate risk is still a matter of debate and the literature is scarce on this topic.3 4 In this study, which is to our knowledge the first randomised trial performed on the management of haemoptysis of mild severity, we focused on that latter population of patients by selecting those having haemoptysis of mild abundance (ie, bleeding amount ranging from 100 to 200 mL) on admission, not associated with acute respiratory failure or shock, and in whom the mechanism of bleeding involved the systemic bronchial artery vasculature. The main aetiologies were chronic inflammatory lung diseases and infectious illnesses, after excluding mycetomas. In this selected population, the use of BAE achieved a 33% absolute reduction of bleeding recurrence rate at 30 days, as compared with the medical strategy (11.8% vs 44.7%). These findings are consistent with a previous observational study from our group,4 which indicated a 11% recurrence rate at 1 month in the subset of patients admitted to the ICU and receiving a BAE for haemoptysis of mild abundance not related to mycetoma or pulmonary arterial vasculature involvement, as compared with a 26% rate with medical management alone.

The superior efficacy of the interventional strategy on bleeding control was sustained at 90 days, with a 91.2% bleeding recurrence-free survival rate compared with 60.2% with the medical strategy. This rate is in the higher range of those reported in uncontrolled series of severe haemoptysis treated with BAE.4 18 20 21 Bleeding recurrences mostly occur in lung cancer, mycetoma or cavitary lesions, and may be related to incomplete embolisation, recanalisation of previously embolised arteries, as well as to the recruitment of new collaterals due to the progression of the underlying disease.4 18 In the present study, lung cancer accounted for only 5.6% of all etiologies. This low rate may be explained by our selection criteria that targeted non-severe acute haemoptysis of mild abundance related to a systemic arterial mechanism. Haemoptysis related to lung cancer usually involve high bleeding amounts, high rate of acute respiratory failure and shock, as well as high rate of pulmonary arterial vasculature involvement.2 4 11 22 Altogether, the spectrum of the aetiologies of haemoptysis in the present study was similar to that recently described in two large European series of haemoptysis of mild severity, including bronchiectasis, pneumonia/lung abscess, acute tuberculosis and post-tuberculosis sequels, and differed from that of haemoptysis of large abundance or associated with other severity criteria.1 2 4 21–24 Cryptogenic haemoptysis also accounted for a large part of our population, and BAE has been shown to provide immediate control of bleeding in most of these cases, with few recurrences at both short and long terms.16 25 26

The overall rate of in-hospital complications related to the randomised strategy was 5.6%. All were reported in patients receiving BAE, including three minor complications and one major complication, all of which had favourable outcomes. These findings are in accordance with other series of the literature4 9 18 27: BAE should be performed by experienced personnel after a rigorous and multidisciplinary evaluation of the benefit:risk ratio. Guiding the procedure with imaging, specifically MDCTA, and the use of modern ionic contrast media and superselective catheterisation of bronchial arteries are essential to decrease the rate of complications related to the procedure.9 18 28–30 There were no complications related to the medical measures, particularly intravenous terlipressin. A recent Israeli study suggested that inhaled tranexamic acid may be helpful for controlling haemoptysis of low abundance.19 Its place in the treatment of moderate-to-severe abundance haemoptysis should be investigated.

Limitations of this study are related to the following: first, the achieved sample size matched to less than half of the expected sample. This discrepancy is in large part due to the fact that the targeted population was representative of less than 20% of the patients screened in the participating units, as most these patients had criteria favouring a first-line interventional radiology. However, to assess the applicability of a first-line interventional strategy outside of the intensive care environment was considered unrealistic. Despite the low recruitment rate, the effect size recorded in this trial, including the consistent results at 30-day and 3-month follow-up, strongly supports the efficacy of the interventional strategy tested. Second, the medical interventions were non-standardised to match routine practice in each centre, which may have favoured the interventional arm, but the use of these different interventions did not differ between groups. Last, due to the relatively small sample size and numbers of events, the trial lacks the power to confidently assess the risk:benefit ratio of BAE in patients with non-severe acute haemoptysis of mild abundance involving the systemic bronchial artery vasculature.

To summarise, BAE added to medical treatment reduced the risk of recurrent bleeding at 30 and 90 days in patients with non-severe acute haemoptysis of mild abundance involving the systemic bronchial artery vasculature, as compared with medical measures alone. In such a selected population presenting with haemoptysis revealing or complicating the course of bronchiectasis, pneumonia/lung abscess, acute tuberculosis and post-tuberculosis sequels, and cryptogenic haemoptysis, the indication of interventional radiology should be weighed with the estimate of the risk associated with the procedure, the risk estimate of bleeding recurrence and information from thoracic imaging.

Acknowledgments

MF takes responsibility for the content of the article, including the data and analysis.

Footnotes

Deceased: Dr Guy Meyer Deceased on 9 Dec 2020

Collaborators: The authors wish to thank the members of the ARTHEMYS trial group who contributed to the conduct of the trial in their respective centres: CHU Tenon, Paris: Michel Djibré, MD; Vincent Labbé, MD; Aude Gibelin, MD; Clarisse Blayau, MD; Guillaume Voiriot, MD, PhD; CHU Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris: Prof. Thomas Similowski, MD, PhD; Prof. Alexandre Duguet, MD, PhD; Hélène Prodanovik, MD; CHU HEGP, Paris: Guillaume Briend, MD; Anne Roche, MD; Benjamin Planquette, MD, PhD; Costantino Del Giudice, MD; Olivier Pellerin, MD, PhD; Prof. Marie-Pierre Revel, MD, PhD; CHU Caen: Prof. Gérard Zalcman, MD, PhD; Prof. Patrick Courtheoux, MD, PhD; CHU Poitiers: Prof Jean Claude Meurice, MD, PhD; Elise Antone, MD; CHU Amiens: Prof. Vincent Jounieaux, MD, PhD; Prof Alexandre Remond, MD, PhD;

CHU Toulouse: Valérie Chabbert, MD.

Contributors: MF takes responsibility for the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis. MF, JC, GM, M-FC, AK, AR and TS conceived and designed the study. MF, AP, MD, VL, AG, CB, AD, JM, HP, OS, EB, CG, SP-M, CA and AK collected the data. MF, ST, AR and TS analysed and interpreted the data. MF, ST, AR and TS drafted the article. All authors participated in the critical revision of the manuscript and provided final approval to submit this version of the manuscript and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: French Ministry of Health (grant PHRC N° 2009-172).

Competing interests: MF reports non-financial support from Biomerieux and personal fees from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. AD reports personal fees from Medtronic, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Philips, personal fees from Baxter and Hamilton, personal fees and non-financial support from Fisher & Paykel, grants from French Ministry of Health, personal fees from Getinge, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Respinor, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Lungpacer, personal fees from Lowenstein, outside the submitted work. OS reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Bayer, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from BMS Pfizer, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees and non-financial support from Boston Scientifics, personal fees and non-financial support from BTG, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from MSD, personal fees from Chiesi, grants from DAIICHI SANKYO, outside the submitted work. Dr. Meyer reports non-financial support from Leo Pharma, non-financial support from BMS-Pfizer, non-financial support from Stago, non-financial support from Bayer Healthcare, outside the submitted work.CG reports grants and personal fees from pfizer, grants and personal fees from MSD, grants and personal fees from SOS Oxygene, grants and non-financial support from Vivisol, grants from Elivie, personal fees from Pulmatrix, grants from Astellas, grants from Gilead, outside the submitted work. TS reports personal fees from Astrazeneca, Novartis, Sanofi, personal fees from Astrazeneca, Astellas, MSD, Sanofi, grants from Astrazeneca, Bayer, Boehringer, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, GSK, Novartis, Sanofi, outside the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

the ARTEMHYS trial group:

Michel Djibré, Vincent Labbé, Aude Gibelin, Clarisse Blayau, Guillaume Voiriot, Thomas Similowski, Alexandre Duguet, Hélène Prodanovik, Guillaume Briend, Anne Roche, Benjamin Planquette, Costantino Del Giudice, Olivier Pellerin, Marie-Pierre Revel, Gérard Zalcman, Patrick Courtheoux, Jean Claude Meurice, Elise Antone, Vincent Jounieaux, Alexandre Remond, and Valérie Chabbert

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Consultation by the editorial board or interested researchers may be considered, subject to prior determination of the terms and conditions of such consultation and with respect to compliance with the applicable regulations.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the ethical review committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile de France IX); written informed consent was obtained from all patients or next of kin before enrolment.

References

- 1. Abdulmalak C, Cottenet J, Beltramo G, et al. Haemoptysis in adults: a 5-year study using the French nationwide Hospital administrative database. Eur Respir J 2015;46:503–11. 10.1183/09031936.00218214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fartoukh M, Khoshnood B, Parrot A, et al. Early prediction of in-hospital mortality of patients with hemoptysis: an approach to defining severe hemoptysis. Respiration 2012;83:106–14. 10.1159/000331501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ibrahim WH. Massive haemoptysis: the definition should be revised. Eur Respir J 2008;32:1131–2. 10.1183/09031936.00080108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fartoukh M, Khalil A, Louis L, et al. An integrated approach to diagnosis and management of severe haemoptysis in patients admitted to the intensive care unit: a case series from a referral centre. Respir Res 2007;8:11. 10.1186/1465-9921-8-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moen CA, Burrell A, Dunning J. Does tranexamic acid stop haemoptysis? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2013;17:991–4. 10.1093/icvts/ivt383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ramon P, Wallaert B, Derollez M, et al. [Treatment of severe hemoptysis with terlipressin. Study of the efficacy and tolerance of this product]. Rev Mal Respir 1989;6:365–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sakr L, Dutau H. Massive hemoptysis: an update on the role of bronchoscopy in diagnosis and management. Respiration 2010;80:38–58. 10.1159/000274492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khalil A, Fedida B, Parrot A, et al. Severe hemoptysis: from diagnosis to embolization. Diagn Interv Imaging 2015;96:775–88. 10.1016/j.diii.2015.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Monroe EJ, Pierce DB, Ingraham CR, et al. An Interventionalist's guide to hemoptysis in cystic fibrosis. Radiographics 2018;38:624–41. 10.1148/rg.2018170122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jougon J, Ballester M, Delcambre F, et al. Massive hemoptysis: what place for medical and surgical treatment. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002;22:345–51. 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00337-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Andréjak C, Parrot A, Bazelly B, et al. Surgical lung resection for severe hemoptysis. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:1556–65. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shigemura N, Wan IY, Yu SCH, et al. Multidisciplinary management of life-threatening massive hemoptysis: a 10-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;87:849–53. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haponik EF, Chin R. Hemoptysis: clinicians' perspectives. Chest 1990;97:469–75. 10.1378/chest.97.2.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haponik EF, Fein A, Chin R. Managing life-threatening hemoptysis: has anything really changed? Chest 2000;118:1431–5. 10.1378/chest.118.5.1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rémy J, Arnaud A, Fardou H, et al. Treatment of hemoptysis by embolization of bronchial arteries. Radiology 1977;122:33–7. 10.1148/122.1.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Savale L, Parrot A, Khalil A, et al. Cryptogenic hemoptysis: from a benign to a life-threatening pathologic vascular condition. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:1181–5. 10.1164/rccm.200609-1362OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marçôa R, Rodrigues DM, Dias M, et al. Classification of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) according to the new global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (gold) 2017: comparison with gold 2011. COPD 2018;15:21–6. 10.1080/15412555.2017.1394285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Panda A, Bhalla AS, Goyal A. Bronchial artery embolization in hemoptysis: a systematic review. Diagn Interv Radiol 2017;23:307–17. 10.5152/dir.2017.16454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wand O, Guber E, Guber A, et al. Inhaled tranexamic acid for hemoptysis treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2018;154:1379–84. 10.1016/j.chest.2018.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chun J-Y, Belli A-M. Immediate and long-term outcomes of bronchial and non-bronchial systemic artery embolisation for the management of haemoptysis. Eur Radiol 2010;20:558–65. 10.1007/s00330-009-1591-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van den Heuvel MM, Els Z, Koegelenberg CF, et al. Risk factors for recurrence of haemoptysis following bronchial artery embolisation for life-threatening haemoptysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2007;11:909–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Razazi K, Parrot A, Khalil A, et al. Severe haemoptysis in patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Eur Respir J 2015;45:756–64. 10.1183/09031936.00010114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mondoni M, Carlucci P, Job S, et al. Observational, multicentre study on the epidemiology of haemoptysis. Eur Respir J 2018;51:1701813. 10.1183/13993003.01813-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ong T-H, Eng P. Massive hemoptysis requiring intensive care. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:317–20. 10.1007/s00134-002-1553-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Delage A, Tillie-Leblond I, Cavestri B, et al. Cryptogenic hemoptysis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: characteristics and outcome. Respiration 2010;80:387–92. 10.1159/000264921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Menchini L, Remy-Jardin M, Faivre J-B, et al. Cryptogenic haemoptysis in smokers: angiography and results of embolisation in 35 patients. Eur Respir J 2009;34:1031–9. 10.1183/09031936.00018709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mal H, Rullon I, Mellot F, et al. Immediate and long-term results of bronchial artery embolization for life-threatening hemoptysis. Chest 1999;115:996–1001. 10.1378/chest.115.4.996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Khalil A, Fartoukh M, Bazot M, et al. Systemic arterial embolization in patients with hemoptysis: initial experience with ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer in 15 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010;194:W104–10. 10.2214/AJR.09.2379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Khalil A, Fartoukh M, Parrot A, et al. Impact of MDCT angiography on the management of patients with hemoptysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010;195:772–8. 10.2214/AJR.09.4161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tanaka N, Yamakado K, Murashima S, et al. Superselective bronchial artery embolization for hemoptysis with a coaxial microcatheter system. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1997;8:65–70. 10.1016/s1051-0443(97)70517-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjresp-2021-000949supp001.pdf (85.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Consultation by the editorial board or interested researchers may be considered, subject to prior determination of the terms and conditions of such consultation and with respect to compliance with the applicable regulations.