Abstract

Upon Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection, protein kinase G (PknG), a eukaryotic‐type serine‐threonine protein kinase (STPK), is secreted into host macrophages to promote intracellular survival of the pathogen. However, the mechanisms underlying this PknG–host interaction remain unclear. Here, we demonstrate that PknG serves both as a ubiquitin‐activating enzyme (E1) and a ubiquitin ligase (E3) to trigger the ubiquitination and degradation of tumor necrosis factor receptor‐associated factor 2 (TRAF2) and TGF‐β‐activated kinase 1 (TAK1), thereby inhibiting the activation of NF‐κB signaling and host innate responses. PknG promotes the attachment of ubiquitin (Ub) to the ubiquitin‐conjugating enzyme (E2) UbcH7 via an isopeptide bond (UbcH7 K82‐Ub), rather than the usual C86‐Ub thiol‐ester bond. PknG induces the discharge of Ub from UbcH7 by acting as an isopeptidase, before attaching Ub to its substrates. These results demonstrate that PknG acts as an unusual ubiquitinating enzyme to remove key components of the innate immunity system, thus providing a potential target for tuberculosis treatment.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, NF‐κB signaling, protein kinase G, ubiquitin ligase, ubiquitin‐activating enzyme

Subject Categories: Microbiology, Virology & Host Pathogen Interaction; Post-translational Modifications, Proteolysis & Proteomics; Signal Transduction

The Mycobaterium tuberculosis effector protein PknG acts as an unusual ubiquitinating enzyme to promote the polyubiquitination and degradation of its substrates TRAF2 and TAK1 via a two‐step cascade, thereby suppressing host innate immune responses.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), which is caused by the pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), remains the leading cause of human mortality due to a single infectious agent. This pathogen was responsible for approximately 10 million new infections and 1.41 million deaths globally in 2019 (World Health Organization, 2020). Additionally, the widespread of drug‐resistant Mtb strains has rendered the currently available TB drugs ineffective. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop new TB drugs based on novel strategies and targets that are effective against drug‐resistant TB. As a typical intracellular pathogen, Mtb can persist in host macrophages due to its ability to manipulate host signaling pathways and cellular processes, such as innate immune signaling pathways and phagocytosis (Kyei et al, 2006; Liu et al, 2017). Therefore, information regarding the molecular mechanisms underlying Mtb–host interactions will be valuable for developing novel effective and selective TB therapies based on Mtb‐host interfaces.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis eukaryotic‐type serine/threonine protein kinases (STPKs) (Wehenkel et al, 2008), which are speculated to mediate cross‐talk between mycobacteria and host macrophage signaling pathways, have become prime targets for the development of novel TB therapeutics. However, their exact regulatory functions in host cells remain largely unknown. Among eleven Mtb STPKs, the mycobacterial serine/threonine protein kinase G (PknG) is of particular interest due to its critical role in Mtb intracellular survival and pathogenicity. Moreover, it is a secreted effector protein and thus can be easily targeted (Av‐Gay & Everett, 2000; Walburger et al, 2004; Prisic & Husson, 2014). PknG promotes the intracellular survival of Mtb by inhibiting host phagosomal maturation (Pradhan et al, 2018). Additionally, it has been shown to regulate glutamate metabolism and to promote intrinsic antibiotic resistance, stress response, and biofilm formation in mycobacteria (Wolff et al, 2009; Ventura et al, 2013; Wolff et al, 2015). Indeed, blocking PknG kinase activity by the tetrahydrobenzothiophene inhibitor AX20017 enhanced clearance of intracellular mycobacteria (Scherr et al, 2007). However, Mtb PknG possesses relatively high amino acid sequence homology (37%) with human protein kinase C‐α (PKC‐α) (Nguyen & Pieters, 2005; Chaurasiya & Srivastava, 2009), thus suggesting the potential for off‐target adverse effects resulting from AX20017 inhibition. Therefore, it is important to elucidate the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying Mtb PknG‐mediated host–pathogen interactions to identify distinct targeting regions in PknG to ultimately improve the selectivity of TB treatment.

Protein ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin (Ub) to a protein target and regulates a variety of cellular activities, including host innate immune signaling (such as NF‐κB signaling) during infection (Li et al, 2016). The typical ubiquitination attaches Ub to substrate proteins via an isopeptide bond that is typically catalyzed through sequential actions of three enzymes, including ubiquitin‐activating enzyme (E1), ubiquitin‐conjugating enzyme (E2), and ubiquitin ligase (E3). During this process, E1 couples ATP hydrolysis to form a thiol‐ester bond between the cysteine (Cys) at its active site and the C‐terminal glycine (Gly) of Ub. Ub is then transferred onto the Cys at the active site of E2, which then cooperates with an E3 to complete the ubiquitination reaction (Hershko & Ciechanover, 1998; Kerscher et al, 2006; Zheng & Shabek, 2017). Ubiquitination can be reversed by a deubiquitinase (DUB), which specifically cleaves the isopeptide bond between Ub and the modified protein. During infection, ubiquitination can be targeted by effector proteins secreted by intracellular pathogens to subvert host innate immunity, thus promoting pathogen intracellular survival and proliferation. For example, the SidE family effectors from Legionella pneumophila could function as E3s to ubiquitinate host proteins using NAD as the energy source in the absence of E1 and E2 enzymes (Qiu et al, 2016), and this activity could be inhibited by another L. pneumophila effector protein (SidJ) that acts as a polyglutamylase to regulate SidE glutamylation (Bhogaraju et al, 2019). Moreover, two Legionella pneumophila effectors (DupA and DupB) have been reported to function as PR‐Ub (a type of Ub‐dependent posttranslational modification)‐specific DUBs that regulate the PR‐ubiquitination levels of host targets (Wan et al, 2019a). However, the manner in which Mtb effector proteins regulate the host ubiquitination system remains unclear.

Surprisingly, in our efforts to explore the molecular mechanisms underlying Mtb PknG‐host interactions, we discovered that Mtb PknG binds to the host E2 protein UbcH7 via a novel ubiquitin‐like (Ubl) domain and catalyzes the attachment of Ub to UbcH7 via an isopeptide bond (UbcH7 K82‐Ub), instead of a usual C86‐Ub thiol‐ester bond. This protein then promotes the discharge of Ub from UbcH7 by acting as an isopeptidase before attaching Ub to host target proteins, including tumor necrosis factor receptor‐associated factor 2 (TRAF2) and TGF‐β‐activated kinase 1 (TAK1), for ubiquitination and degradation by acting as an unconventional E3 enzyme, thus leading to inhibition of NF‐κB signaling. Taken together, these results indicate that Mtb PknG functions as an unusual ubiquitinating enzyme that suppresses host innate immunity. Our findings reveal novel insights into the intricate interactions between Mtb and its host, thus providing a potential TB treatment by targeting the unconventional ubiquitinating activity of Mtb PknG.

Results

Mtb PknG interacts with the E2 protein UbcH7 during mycobacterial infection

In an attempt to better understand the regulatory roles and to identify host targets of Mtb PknG during mycobacterial infection, we screened its interacting proteins within the host using yeast two‐hybrid assay, and we found that the host E2 protein UbcH7 interacted directly with Mtb PknG (Fig 1A and Appendix Table S1). To verify this interaction, we deleted the gene encoding PknG (pknG) in the M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv (Mtb ΔpknG) and challenged macrophage‐like U937 cells with wild‐type (WT) Mtb or Mtb ΔpknG strains for immunoprecipitation assays. The results revealed that Mtb PknG interacted with UbcH7 in infected macrophages (Fig 1B). To determine the direct and specific interactions of PknG with UbcH7, we also performed pull‐down assays using recombinant proteins, and we demonstrated that PknG exhibited a strong interaction with UbcH7, but not with other E2s including UbcH5a or UbcH8 (Fig 1C). We then re‐examined the structure of Mtb PknG (PDB ID: 2PZI) to identify their potential interacting motifs. Mammalian ubiquitin and ubiquitin‐like (Ubl) proteins usually contain a β‐grasp fold (Hochstrasser, 2009), which is found in at least 70 distinct families of proteins in eukaryotes (Burroughs et al, 2012). Notably, in addition to the conserved kinase domain (amino acids 151–396) and tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain (amino acids 506–568), a β‐grasp fold‐like region was identified at the N‐terminal region of PknG (amino acids 140–234) (Fig 1D). Similar to in Ub and the ubiquitin‐fold domain (UFD) of E1 (Fig 1E), this PknG region contains five β‐strands and an α‐helix (Fig 1F). The orientation of the five strands in PknG is highly similar to that of Ub or the UFD of E1, although its α‐helix lies in a different orientation. Given the high diversity of β‐grasp folds, even in eukaryotes, we wondered if the prokaryotic β‐grasp fold‐like region of PknG could serve as a ubiquitin‐like domain. Because UbcH7 can bind the α‐helix of Ub (Dove et al, 2017), we thus hypothesized that the α‐helix (amino acids 188–204) in the β‐grasp‐fold‐like region may act as the potential binding region for the interaction of PknG with UbcH7 (Fig EV1A). Indeed, this PknG region exhibited a strong interaction with UbcH7, while the deletion of its β‐grasp‐fold‐like region abolished this interaction in infected macrophages and transfected HEK293T cells (Figs 1G and EV1B). We then did serial mutation screening in the potential UbcH7‐interacting region of PknG by constructing a number of PknG mutants in which the residues covering the potential binding sites were mutated into alanine (Ala) (Fig EV1C). We found that PknG Glu190Ala (PknG E190A) mutation did not affect the kinase activity of PknG (Fig EV1D); however, it abolished the interaction of PknG with UbcH7 (Fig 1H and EV1E). Taken together, our data indicate that Mtb PknG interacts with host E2 protein UbcH7 via a novel Ubl domain during mycobacterial infection.

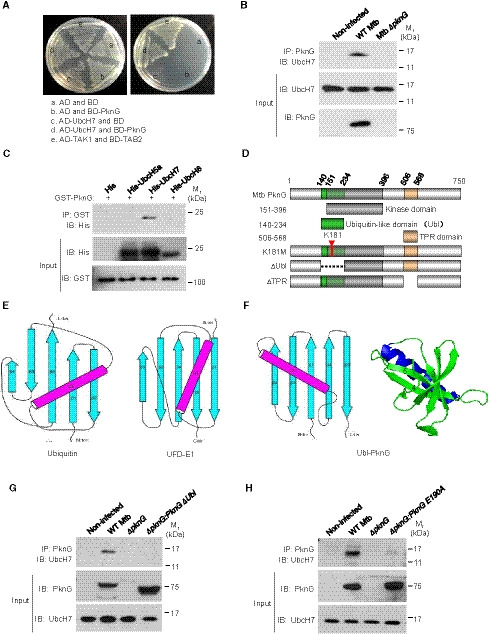

Figure 1. Mtb PknG interacts with the E2 protein UbcH7 through the Ubl domain.

-

AYeast two‐hybrid assay for the interaction of PknG with UbcH7. Yeast strains were transformed with the indicated plasmids, where the TAK1–TAB2 interaction served as a positive control. Left, low stringency. Right, high stringency.

-

BImmunoprecipitation (IP) of UbcH7 by Mtb PknG in U937 cells. Cells were infected with wild‐type (WT) Mtb or Mtb ΔpknG at an MOI of 1. Non‐infected cells were used as controls. After 4 h, the cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with the antibody against PknG. IP products were immunoblotted with the antibody against UbcH7.

-

CPull‐down of His‐tagged E2s (5 μg each) by GST‐PknG (10 μg each). Pull‐down products were immunoblotted using the antibody against the His‐tag.

-

DSchematic diagram of the Mtb PknG domains.

-

E, FTopology diagrams of the β‐grasp folds of ubiquitin (E, left), the ubiquitin‐fold domain (UFD) of the E1 enzyme (E, right), and the putative Ubl domain in PknG (F, left) are shown, and a cartoon depiction of the β‐grasp fold of PknG is included (F, right). Strands in the topology diagrams are illustrated as cyan arrows, and the helices are highlighted in magenta.

-

GIP of UbcH7 by PknG or PknGΔUbl in U937 cells. Cells were infected with WT, ΔpknG, or ΔpknG:pknGΔUbl Mtb strains as in (B).

-

HIP of UbcH7 by PknG or PknG E190A in U937 cells. Cells were infected with WT, ΔpknG, or ΔpknG:pknG E190A Mtb strains as in (B).

Source data are available online for this figure.

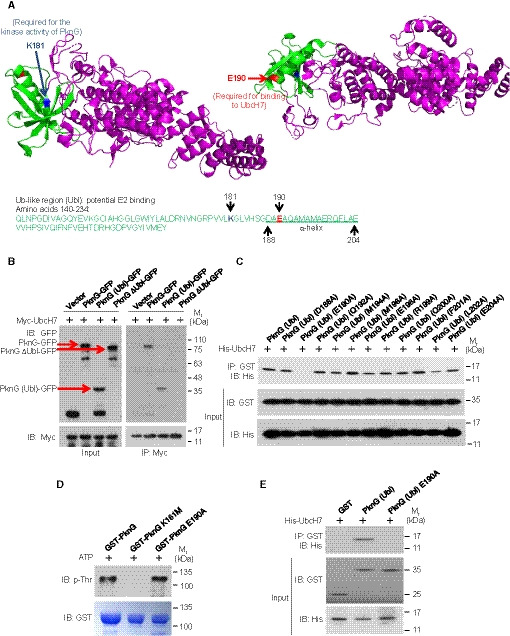

Figure EV1. Mtb PknG interacts with UbcH7 via Glu190 in the Ub‐like (Ubl) domain.

- The predicted region for UbcH7 interaction in PknG (green, Ubl‐like region; magenta, other regions) with the K181 and E190 sites highlighted (blue, K181 site; red, E190 site). The Mtb PknG PDB accession code is 2PZI.

- IP of GFP‐tagged Mtb PknG or its truncated forms using Myc‐UbcH7 in HEK293T cells. Red arrows indicate the bands of PknG‐GFP, PknG (Ubl)‐GFP, or PknG ΔUbl‐GFP. The immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted using the antibodies against GFP‐tag on PknG and Myc‐tag on UbcH7.

- Pull‐down of His‐UbcH7 (2 μg each) by the GST‐tagged Ubl domain of PknG and its mutants (7 μg each). Pull‐down products were immunoblotted using the antibody against the His‐tag on UbcH7.

- Autophosphorylation levels of PknG and its mutants in vitro. The autophosphorylation activity of recombinant GST‐tagged PknG, PknG K181M, and PknG E190A was detected using the anti‐p‐Thr antibody. Coomassie brilliant blue staining shows the loading of the recombinant proteins.

- Pull‐down of His‐tagged UbcH7 (2 μg each) by GST (6 μg), GST‐tagged Mtb PknG (Ubl), or its E190A mutant (7 μg each). Pull‐down products were immunoblotted using the antibody against the His‐tag on UbcH7.

Source data are available online for this figure.

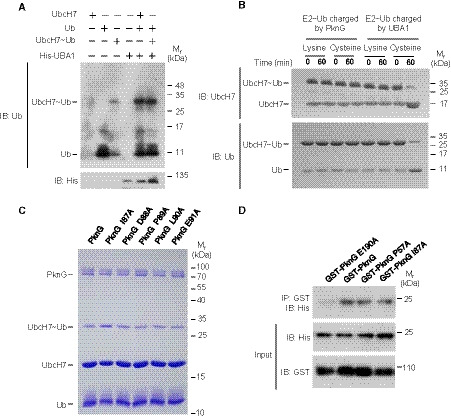

Mtb PknG acts as an unconventional E1 with isopeptidase activity

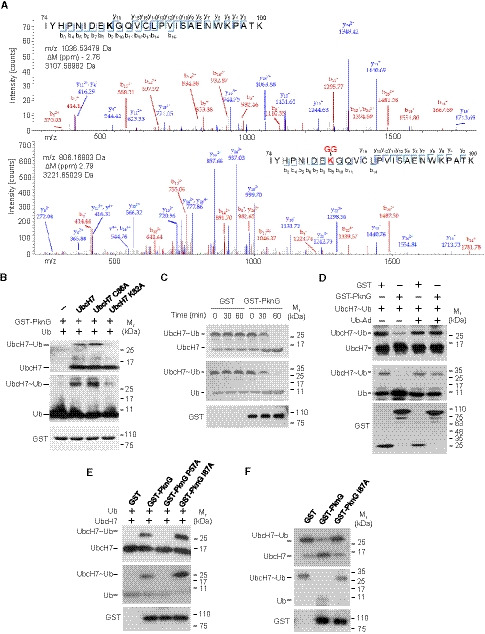

The typical ubiquitination process requires a cascade of three enzymes (E1, E2, and E3) that activate, conjugate, and transfer Ub to the substrate sequentially (Hershko & Ciechanover, 1998). Normally, the E2 protein UbcH7 is charged with Ub by an E1 and subsequently interacts with E3s such as Parkin and HHAIR to mediate substrate ubiquitination (Wenzel et al, 2011). Thus, we sought to determine if Mtb PknG interacts with UbcH7 to mimic a eukaryotic E1 or E3 during mycobacterial infection. We began by conducting a ubiquitin conjugation assay for UbcH7, and we found that PknG could function as an unconventional E1 to promote the loading of Ub onto UbcH7 using ATP as the source of energy, a process that is indicated by a molecular weight shift of UbcH7 in SDS‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) (Fig 2A). A time course analysis for Ub conjugation of UbcH7 catalyzed by PknG further revealed that the level of Ub‐conjugated UbcH7 increased over time within 30 min (Fig 2B). We next performed liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC‐MS) using PknG Lys181Met (K181M), a kinase‐dead mutant (Walburger et al, 2004), to exclude the potential interference of the kinase activity of PknG on its ubiquitination function. We observed that PknG K181M could utilize ATP for the ubiquitination reaction with the release of ADP (Fig 2C), a process different from the reaction catalyzed by the conventional E1, which uses ATP to form the Ub‐AMP adduct, and is then followed by the production of E1‐Ub with the release of AMP (Haas & Rose, 1982; Haas et al, 1982; Schulman & Harper, 2009; Gavin et al, 2012). Consistently, by performing Western blotting analysis using ATP analogs (including ATP‐γ‐S, AMPCPP, and AMPPNP) to replace ATP, we determined that PknG could use AMPCPP and AMPPNP, but not ATP‐γ‐S, to catalyze Ub conjugation onto UbcH7, thus suggesting that ATP is hydrolyzed at the γ site during the reaction (Fig EV2A). Unlike the classic Ub conjugation of E2s that require the E1 to form a thiol‐ester bond between their active Cys and the C‐terminal Gly of Ub, PknG could directly catalyze Ub conjugation onto UbcH7 in a kinase activity‐independent and Ubl domain‐dependent manner (Figs 2D and EV2B) in the presence or absence of the reducing agent β‐mercaptoethanol, bypassing the formation of the PknG‐Ub linkage step (Figs 2E and EV2C). These results raise the possibility that ubiquitin is linked to UbcH7 by the isopeptide bond, rather than by the thioester bond. Serial mutation screening was performed by constructing a number of PknG truncations or mutants, and we determined that the Pro57Ala mutation in the N‐terminal region of PknG (PknG P57A) abolished its E1‐like activity, thus suggesting that Pro57 is required for the E1‐like activity of PknG toward UbcH7 (Figs 2F and EV2, EV3, EV4, EV5). In a canonical ubiquitination reaction, the charged E1~Ub recruits cognate E2s, and Ub is then transferred from the catalytic Cys of E1 to the E2 catalytic Cys residue (Hershko & Ciechanover, 1998). We next sought to identify the residue of PknG that mediates UbcH7 ubiquitin conjugation. When the Cys residues of PknG were replaced by Ala, Ub conjugation of UbcH7 could still be easily detected, thus indicating that PknG may catalyze ubiquitin conjugation of UbcH7 in a manner that is independent of the formation of a Cys~Ub linkage (Fig EV2G). We then performed mass spectrometry (MS) analysis to identify the Ub‐binding sites of the charged UbcH7~Ub mediated by PknG, and based on this analysis, GlyGly or LeuArgGlyGly modification was detected at the residues of UbcH7. Specifically, we determined that Lys82 was the Ub modification site catalyzed by Mtb PknG (Fig 3A and Dataset EV1). We then replaced Lys82 or Cys86 (a canonical catalytic residue of the E2 pre‐charged with Ub by E1) (Hershko & Ciechanover, 1998) with Ala in UbcH7 (UbcH7 K82A and C86A) for the ubiquitin conjugation assays of UbcH7, and we determined that Lys82, but not Cys86, of UbcH7 was a crucial site for PknG‐catalyzed ubiquitin conjugation (Fig 3B). To test if the ubiquitin modification of the Lys82 site in UbcH7 inhibits its canonical E2 activity, we prepared a large quantity of UbcH7 K82‐Ub catalyzed by PknG, and we then performed a ubiquitin conjugation assay of UbcH7 K82‐Ub catalyzed by UBA1 in vitro. The results revealed that UbcH7 K82‐Ub could not be further modified with ubiquitin on the Cys86 site by UBA1 (Fig EV3A). Taken together, these results indicate that PknG exhibits a Ubl domain‐dependent unconventional E1 activity that could directly catalyze Ub conjugation onto the Lys82 of UbcH7 in the presence of ATP, thus subsequently abrogating the canonical E2 activity of UbcH7.

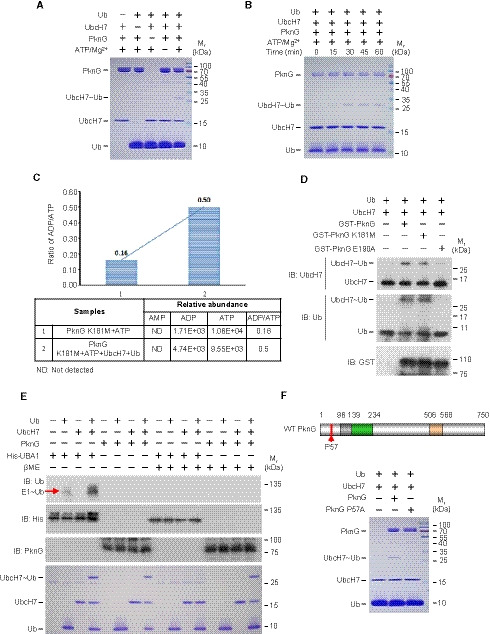

Figure 2. Mtb PknG catalyzes the conjugation of ubiquitin onto UbcH7 in vitro .

- In vitro ubiquitin conjugation assay of UbcH7. UbcH7 was incubated with PknG, Ub, and ATP/Mg2+ at 37°C for 30 min. Reaction products were analyzed on a 12% SDS–PAGE gel and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

- In vitro ubiquitin conjugation assay of UbcH7 catalyzed by PknG over time. The reaction products were analyzed as in (A).

- The ADP/ATP ratios in the ubiquitination reaction mixtures. The reaction mixtures containing 2 μM PknG K181M and 5 μM ATP were incubated at 37°C for 30 min in the absence (reaction 1) or presence (reaction 2) of 5 μM Ub and 5 μM UbcH7. LC‐MS MultiQuant software was used to calculate the normalized abundance of each compound (including AMP, ADP, and ATP) by measuring the peak area intensity.

- In vitro ubiquitin conjugation assay of UbcH7 catalyzed by GST‐tagged PknG or its mutants at 37°C for 30 min. Reaction products were immunoblotted with antibodies against UbcH7 (top panel), Ub (middle panel), and the GST tag on PknG (bottom panel).

- In vitro ubiquitin conjugation assay of UbcH7 catalyzed by PknG or His‐UBA1 at 37°C for 30 min. The reaction products were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against Ub (top panel), the His‐tag on UBA1 (middle panel), and PknG (bottom panel), or by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (bottom). For reducing conditions, samples were treated with 500 mM β‐mercaptoethanol (βME) prior to SDS–PAGE gel analysis.

- In vitro ubiquitin conjugation assay of UbcH7 catalyzed by PknG or its E1 activity‐dead mutant (PknG P57A). Top, the schematic of Mtb PknG. Red arrow, Pro57 site; Bottom, reaction products were analyzed as in (A).

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure EV2. Mtb PknG possesses unconventional Ub‐activating enzyme activity.

- In vitro ubiquitin conjugation assay of UbcH7. UbcH7 was incubated with GST‐tagged PknG or PknG K181M, and Ub at 37°C for 30 min in the presence of ATP or ATP analogs, including AMPCPP, AMPPNP, and ATP‐γ‐S. The reaction products were immunoblotted using antibodies against UbcH7 (top panel), Ub (middle panel), and the GST tag on PknG (bottom panel).

- UbcH7 ubiquitin conjugation assay catalyzed by PknG or its mutants at 37°C for 30 min. Reaction products were immunoblotted using antibodies against UbcH7 (top panel), Ub (middle panel), and PknG (bottom panel).

- UbcH7 ubiquitin conjugation assay in vitro. GST‐tagged PknG was incubated with UbcH7 and Ub at 37°C for 30 min in the presence of ATP. The reaction products were immunoblotted using antibodies against the GST tag on PknG (top panel), UbcH7 (middle panel), and Ub (bottom panel).

- UbcH7 ubiquitin conjugation assay in vitro by GST‐tagged PknG or its truncations. Top, schematic diagram of Mtb PknG domains. PknG ΔN, N‐terminal region (which was reported to be essential for Mtb intracellular survival)‐deleted PknG; PknG ΔRdl, rubredoxin‐like domain‐deleted PknG; PknG ΔUbl, ubiquitin‐like domain‐deleted PknG; PknG ΔTPR, TRP domain‐deleted PknG. Bottom, reaction products were analyzed on a 12% SDS–PAGE gel and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

- UbcH7 ubiquitin conjugation assay in vitro using GST‐tagged PknG or its mutants (the residues covering the potential unconventional E1 activity sites were mutated into alanines). The reactions products were analyzed as in (D).

- UbcH7 ubiquitin conjugation assay in vitro using PknG or its mutants. The reactions products were analyzed as in (D).

- UbcH7 ubiquitin conjugation assay in vitro using GST‐tagged PknG or its mutants (the cystine residues were mutated into alanine residues). The reaction products were analyzed as in (D).

Source data are available online for this figure.

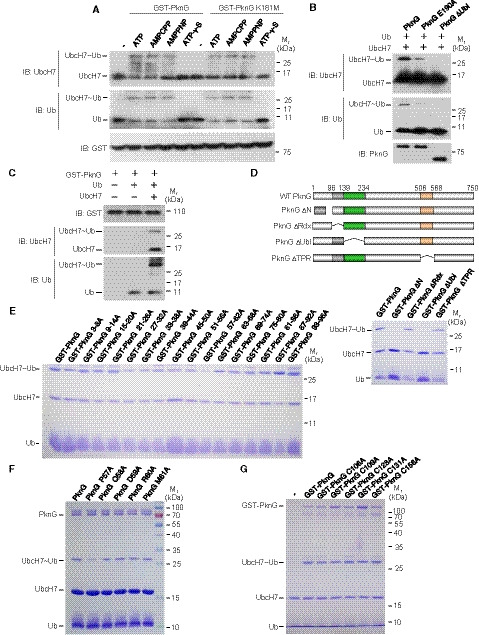

Figure EV3. Mtb PknG possesses unconventional Ub‐activating enzyme and isopeptidase activities.

- Ubiquitin conjugation assay of Ub‐conjugated UbcH7 (UbcH7 K82‐Ub) catalyzed by UBA1 at 37°C for 30 min. We obtained a large quantity of UbcH7‐Ub (K82) catalyzed by PknG, purified the conjugate, and performed the ubiquitin conjugation assay in the presence of His‐UBA1 and ATP. The reaction products were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against Ub (top panel) and the His tag on UBA1 (bottom panel).

- In vitro ubiquitin discharge assay of UbcH7~Ub charged by PknG or E1 at 37°C in buffers containing 50 mM free lysine or cysteine. The reaction products were immunoblotted using antibodies against UbcH7 (top panel) and Ub (bottom panel).

- UbcH7 ubiquitin conjugation assay in vitro using PknG or its mutants. Reaction products were analyzed on a 12% SDS–PAGE gel and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

- Pull‐down of His‐UbcH7 (2 μg each) using GST‐tagged PknG, PknG P57A (an E1 activity‐dead mutant), or PknG I87A (an isopeptidase activity‐dead mutant) (10 μg each). Pull‐down products were immunoblotted using the antibody against the His‐tag on UbcH7.

Source data are available online for this figure.

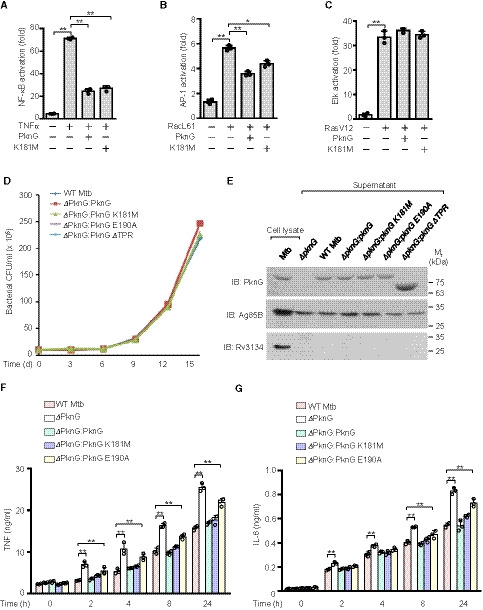

Figure EV4. Mtb PknG inhibits NF‐κB signaling activation and cytokine production.

-

A–CLuciferase assay of TNFα‐induced NF‐κB activation (A), RacL61‐induced AP‐1 activation (B), and RasV12‐induced Elk activation (C) in the absence or presence of WT Mtb PknG or its K181M mutant form in HEK293T cells. The cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM of three independent biological replicates, n = 3. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (one‐way ANOVA).

-

DThe PknG‐mutant strain exhibited no growth defects compared to the growth of the WT Mtb strain. A total of 2 × 106 CFUs of Mtb strains were inoculated into Middlebrook 7H9 broth and cultivated at 37°C, and the cultures from each time point were then plated onto 7H10 agar for bacterial CFU counting.

-

EImmunoblotting analysis of PknG protein levels in culture supernatants of the indicated Mtb strains. Cultures were grown in 50 ml of Sauton medium for 2 days, and the supernatants were then collected for precipitation using 10% trichloroacetic acid. The secreted protein Ag85B was used as the loading control, and the non‐secreted protein Rv3134 was used to confirm that the supernatants were free of contamination due to cell lysis.

-

F, GELISA of TNF (F) and IL‐6 (G) in the medium from colony‐stimulating factor‐induced human primary monocyte‐derived macrophages. The cells were infected with WT, ΔpknG, ΔpknG:pknG, ΔpknG:pknG K181M, or ΔpknG:pknG E190A Mtb strains at an MOI of 1 for 0–24 h. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM of three independent biological replicates, n = 3. **P < 0.01 (one‐way ANOVA).

Source data are available online for this figure.

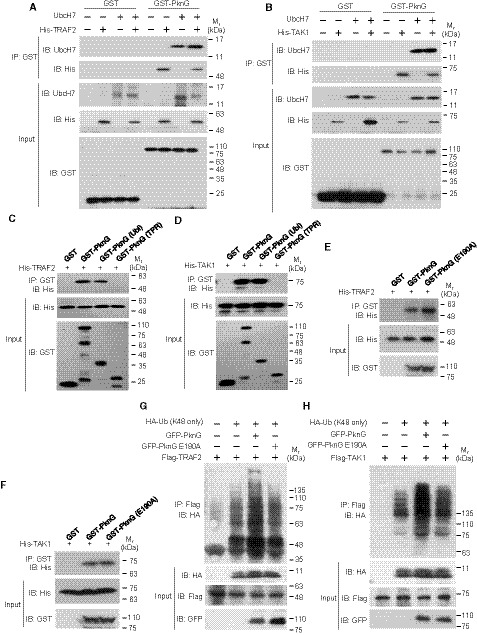

Figure EV5. Mtb PknG targets TRAF2 and TAK1 for degradation by binding to UbcH7.

-

A, BPull‐down of TRAF2 (6 μg each) (A) or TAK1 (8 μg each) (B) by GST (3 μg each) or GST‐tagged WT PknG (10 μg each) with or without purified UbcH7 (2 μg each). Pull‐down products were immunoblotted using antibodies against UbcH7 and the His‐tag on TRAF2 or TAK1.

-

C, DPull‐down of His‐tagged TRAF2 (6 μg each) (C) or TAK1 (8 μg each) (D) using GST‐tagged WT PknG (10 μg each) or its truncated forms (3 μg each). Pull‐down products were immunoblotted using antibody against the His‐tag on TRAF2 or TAK1.

-

E, FPull‐down of His‐tagged TRAF2 (6 μg each) (E) or TAK1 (8 μg each) (F) using GST‐tagged WT PknG or PknG E190A (10 μg each). Pull‐down products were immunoblotted using antibodies against the His‐tag on TRAF2 or TAK1.

-

G, HIn vivo ubiquitination assay of TRAF2 (G) and TAK1 (H) in HEK293T cells. Cells were transfected with vectors encoding Flag‐TRAF2, HA‐Ub (K48 only), and GFP‐tagged Mtb PknG or its E190A mutant form for 24 h. The reaction products were immunoblotted using the antibody against the HA‐tag on Ub.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure 3. Mtb PknG is an unconventional E1 with isopeptidase activity in vitro .

- MS/MS analysis of UbcH7 in the absence (top) or presence (bottom) of PknG to reveal ubiquitination sites. Tryptic peptides spanning residues ranging from 74 to 100 were identified as the high‐confidence peptides possessing di‐Gly modifications. The ubiquitinated residue (Lys82) in the peptide sequence is highlighted in red. The peak heights are the relative abundances of the corresponding fragmentation ions. Matched amino terminus‐containing ions (b ions) are indicated in red, and matched carboxyl terminus‐containing ions (y ions) are indicated in blue. Only the major peaks that were identified are labeled.

- Ubiquitin conjugation assay of UbcH7 or its mutants catalyzed by GST‐tagged PknG at 37°C for 30 min. Reaction products were immunoblotted using antibodies against UbcH7 (top panel), Ub (middle panel), and the GST tag on PknG (bottom panel).

- In vitro ubiquitin discharge assay of UbcH7~Ub with or without PknG. The reaction products were immunoblotted as in (B).

- In vitro isopeptidase assays of PknG with or without ubiquitin‐aldehyde (Ub‐Ad). The reactions were performed at 37°C for 30 min and analyzed as in (B).

- In vitro ubiquitin conjugation assay of UbcH7 by PknG, PknG P57A, or PknG I87A. The reaction products were immunoblotted as in (B).

- In vitro ubiquitin discharge assay of UbcH7~Ub by PknG or its isopeptidase activity‐dead mutant (PknG I87A). The reaction products were immunoblotted as in (B).

Source data are available online for this figure.

UbcH7~Ub charged by canonical E1 (UbcH7 C86‐Ub) can transfer Ub to free Cys amino acids, but not Lys amino acids, independently of an E3 (Wenzel et al, 2011; Yuan et al, 2017). We then further incubated UbcH7~Ub charged by PknG (UbcH7 K82‐Ub) with free Lys or Cys, and we found that UbcH7 K82‐Ub cannot directly transfer Ub to free Lys or Cys in vitro (Fig EV3B). Next, we demonstrated that PknG could remove Ub from UbcH7 K82‐Ub (Fig 3C). As K82‐Ub is linked by an isopeptide bond, this removal was likely caused by the isopeptidase activity of PknG. Indeed, the removal of Ub by PknG could be greatly reduced by ubiquitin‐aldehyde (Ub‐Ad), a general inhibitor of isopeptidases (Fig 3D). Thus, we attempted to identify key sites for the potential isopeptidase activity of PknG. Among all the tested mutations, the PknG Ile87Ala (PknG I87A) mutation led to the accumulation of a larger quantity of UbcH7 Lys82‐Ub, thus suggesting that Ile87 is required for the Ub‐removing activity of PknG (Figs 3E and EV3C). It should be mentioned that PknG P57 and PknG I87 contribute to the E1‐like or isopeptidase activity of PknG, respectively, but they do not affect its interaction with UbcH7 (Fig EV3D). We also repeated the Ub discharge assay in vitro, and we further confirmed that the PknG I87A mutation indeed abolished the Ub‐removing activity of PknG (Fig 3F). Taken together, our data indicate that Mtb PknG possesses an isopeptidase activity that relies on the Ile87 residue.

Mtb PknG inhibits host innate immunity by preventing NF‐κB activation

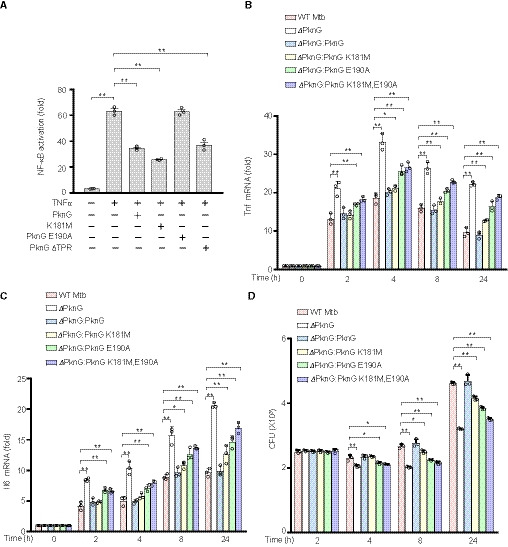

The ubiquitination system plays an important role in host innate immune responses and thus represents a prime eukaryotic host target for bacterial pathogens (Vergne et al, 2005; Wang et al, 2015). We next investigated if Mtb PknG modulates host innate immune signaling pathways, including the NF‐κB and MAPK pathways. Luciferase reporter assays were performed in human HEK293T cells transfected with vectors encoding different mutants of PknG as well as fluorescent protein‐reporting vectors. Transient expression of Mtb PknG in HEK293T cells markedly suppressed the TNFα‐induced NF‐κB signaling, while it exerted a slight effect on the RacL61‐induced AP‐1 (a transcription factor in JNK and p38 MAPK pathways) activation and no effect on the RasV12‐induced Erk pathway activation (Fig EV4, EV5). Notably, the E190A mutation, which disrupted the interaction between PknG and UbcH7, abolished PknG‐mediated suppression of the NF‐κB activation, while other PknG mutations, including K181M and PknG ΔTPR, did not cause such effects (Fig 4A). To better elucidate the specific regulatory function of PknG, we constructed multiple PknG mutants and complemented them with ΔpknG Mtb strains. The results demonstrated that the PknG‐mutant Mtb strains grew at similar rates compared to that of the WT Mtb strain in 7H9 medium, and the PknG protein levels secreted by these mutants were also comparable to those from the WT Mtb strain (Fig EV4D and E). We then performed quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analyses to examine whether the expression of cytokines was regulated by Mtb PknG or its mutants during Mtb infection. Deletion of PknG in Mtb promoted the production of inflammatory cytokines including TNF and IL‐6 and decreased bacterial survival in primary human monocyte‐derived macrophage cells, thus suggesting that PknG inhibits inflammatory cytokine production and enhances bacterial intracellular survival. The E190A mutation, but not the K181M mutation, largely abolished the Mtb PknG‐mediated suppression of inflammatory cytokine production in macrophage cells, particularly at 0–8 h after infection, thus indicating that PknG inhibits inflammatory cytokine production in Mtb‐infected macrophage cells depending on its Ubl domain, but not its kinase activity, in the early stage of infection (Figs 4B and C, and EV4F and G). We also observed that the E190A mutation largely abrogated, while the K181M mutation partially abrogated, the Mtb PknG‐mediated inhibition of cytokine production and promotion of bacterial survival in macrophage cells, particularly after 8 h post‐infection, thus indicating that PknG promotes the intracellular survival of Mtb in a manner that is primarily dependent upon its Ubl domain and partially dependent upon its kinase activity, where the latter may regulate other cellular functions such as pathogen clearance rather than the NF‐κB pathway (Fig 4B–D). Consistently, the PknG E190A and K181M double‐mutant Mtb strain (ΔpknG:pknG K181M, E190A) exhibited higher cytokine production and lower bacterial loads than did either the ΔpknG:pknG K181M strain or the ΔpknG:pknG E190A strain, particularly at 8–24 h post‐infection. This may have been caused by accelerated pathogen clearance followed by the release of NF‐κB pathway inhibition (Fig 4B–D). Taken together, our data indicate that Mtb PknG can specifically inhibit NF‐κB activation in a manner that is dependent upon its Ubl domain.

Figure 4. Mtb PknG inhibits NF‐κB activation in a E190 residue‐dependent manner.

-

ALuciferase assay of NF‐κB activation in HEK293T cells transfected with WT or mutant Mtb PknG. The graph shows the mean ± SEM of three independent biological replicates, n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Data were analyzed according to one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using GraphPad Prism 7.

-

B, CqPCR analysis of Tnf mRNA (B) and Il6 mRNA (C) in primary human monocyte‐derived macrophages. Cells were infected with WT, ΔpknG, ΔpknG:pknG, ΔpknG:pknG K181M, ΔpknG:pknG E190A, or ΔpknG:pknG K181M, E190A Mtb strains at an MOI of 1 for 0–24 h. The fold changes obtained from each sample were normalized to those of GAPDH. The graph shows the mean ± SEM of three independent biological replicates, n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Data were analyzed according to one‐way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism 7.

-

DSurvival of Mtb strains in primary human monocyte‐derived macrophages treated as in (B) and (C). The graph shows the mean ± SEM of three independent biological replicates, n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Data were analyzed according to one‐way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism 7.

Mtb PknG promotes the degradation of TRAF2 and TAK1 by serving as unconventional E1 and E3

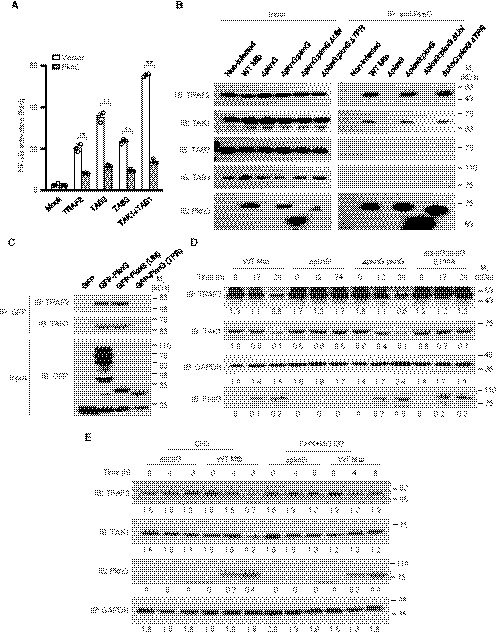

To explore the molecular mechanism by which PknG inhibits NF‐κB activation, we conducted luciferase reporter assays in HEK293T cells, and we determined that PknG suppressed TAK1 or TAB1‐mediated activation of NF‐κB (Fig 5A). Co‐immunoprecipitation analysis in both transfected HEK293T cells and infected macrophages further demonstrated that PknG interacted with TRAF2 and TAK1, but not TAB2 and TAB3, all of which are key components of the NF‐κB signaling (Napetschnig & Wu, 2013), through its UbcH7‐binding domain (Fig 5B and C). Consistently, pull‐down assays also revealed that TRAF2 and TAK1 bound to the Ubl domain of PknG both in the absence and presence of UbcH7 (Fig EV5A–D). Meanwhile, immunoblotting analyses indicated that the PknG E190A mutant did not affect the interaction with TRAF2 or TAK1 (Fig EV5E and F). Furthermore, we found that the protein levels of TRAF2 and TAK1 were markedly decreased in U937 cells infected with WT Mtb or with the Mtb ΔpknG:pknG strain, but not with the Mtb ΔpknG or Mtb ΔpknG:pknG E190A strains (Fig 5D). This effect was abolished in the cells treated with proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig 5E), thus indicating that the PknG‐mediated decrease in the protein levels of TRAF2 and TAK1 was caused by proteasomal degradation. Together, these results suggest that PknG may promote the proteasome‐based degradation of TRAF2 and TAK1 by interacting with UbcH7.

Figure 5. Mtb PknG targets TRAF2 and TAK1 for degradation by binding to UbcH7.

- Dual‐luciferase assay of TRAF2‐, TAB2‐, TAB3‐, TAK1‐, or TAB1‐induced NF‐κB activation in the absence or presence of Mtb PknG in HEK293T cells. The graph shows the mean ± SEM of three independent biological replicates, n = 3. **P < 0.05. Data were analyzed according to a two‐tailed unpaired t‐test using GraphPad Prism 7.

- IP of TRAF2 and TAK1 by Mtb PknG in U937 cells. Cells were infected with the indicated Mtb strains at an MOI of 1. Non‐infected cells were used as controls. After 4 h, the cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with the antibody against PknG. The immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted with TRAF2, TAK1, TAB2 (negative control), or TAB3 (negative control) antibodies.

- IP of TRAF2 and TAK1 by GFP‐tagged Mtb PknG or its truncated forms in transfected HEK293T cells.

- Immunoblotting analysis of TRAF2, TAK1, and PknG from lysates of U937 cells infected with the indicated Mtb strains at an MOI of 1 for 0–24 h. GAPDH was used as the loading control. Densitometric quantification of immunoblots is indicated below the immunoblots.

- Immunoblotting of TRAF2, TAK1, and PknG from lysates of U937 cells infected with the indicated Mtb strains at an MOI of 1 for 8 h. Cells were treated with CHX (50 μg/ml) with or without MG132 (5 μM). Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting for TRAF2 (anti‐TRAF2), TAK1 (anti‐TAK1), and PknG (anti‐PknG). GAPDH was used as the loading control. Densitometric quantification of immunoblots is indicated below the immunoblots.

Source data are available online for this figure.

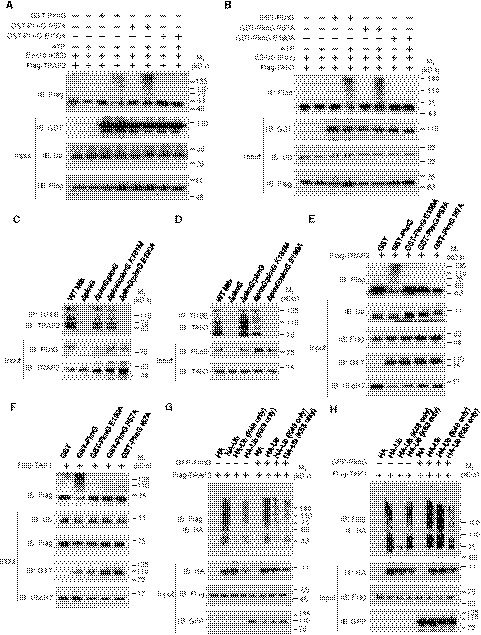

To investigate the E3 activity of PknG toward TRAF2 and TAK1, we first obtained large quantities of UbcH7 K82‐Ub in the reaction catalyzed by PknG, and we then purified the conjugate and performed an in vitro ubiquitination assay for TRAF2 or TAK1 using WT PknG or its mutants including PknG E190A (defective in interacting with UbcH7) and PknG P57A (defective in charging UbcH7 at Lys82 but still retaining the E3 activity). We observed an obvious ubiquitination of TRAF2 and TAK1 in the presence of PknG or the PknG P57A mutant, but not in the presence of the PknG E190A mutant (Fig 6A and B), thus indicating that PknG possesses E3 activity to promote the ubiquitination of TRAF2 and TAK1 in a UbcH7 binding‐dependent manner. Accordingly, WT PknG and PknG K181M, but not its E190A mutant, promoted UbcH7‐dependent polyubiquitination of TRAF2 and TAK1 in the infected macrophages (Fig 6C and D). Furthermore, the addition of UbcH7 and Ub to the purified TRAF2 or TAK1 proteins promoted the ubiquitination of TRAF2 or TAK1 in vitro in the presence of WT PknG, but not its unconventional E1 or isopeptidase activity‐dead mutant (Fig 6E and F). We then demonstrated that PknG promoted the K48‐linked, but not the K63‐linked, polyubiquitination of TRAF2 and TAK1 (Fig 6G and H), and we further confirmed that the activity of PknG relied on its interaction with UbcH7 (Fig EV5G and H). Taken together, our data indicate that Mtb PknG processes unconventional E1 and E3 activities to promote ubiquitination of TRAF2 and TAK1, ultimately leading to their ubiquitination‐mediated degradation and inhibition of the NF‐κB pathway.

Figure 6. Mtb PknG promotes Lys48‐linked polyubiquitination of TRAF2 and TAK1 depending on UbcH7‐binding.

-

A, BIn vitro ubiquitination of Flag‐TRAF2 (A) and Flag‐TAK1 (B) in the presence of Ub‐conjugated UbcH7 (catalyzed by PknG) and PknG or its mutants, with or without ATP as an energy source. The reaction products were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against Flag‐tagged TRAF2 and TAK1.

-

C, DIn vivo ubiquitination assay of TRAF2 (C) and TAK1 (D) in U937 cells infected with WT, ΔpknG, ΔpknG:pknG, ΔpknG:pknG K181M, or ΔpknG:pknG E190A Mtb strains at an MOI of 1 for 6 h. Endogenous ubiquitinated proteins were enriched using TUBE reagents and immunoblotted with antibodies against TRAF2 (C, top panel) or TAK1 (D, top panel).

-

E, FIn vitro ubiquitination of TRAF2 (E) and TAK1 (F) in the presence of UbcH7, Ub, and PknG or its mutants. The reaction products were immunoblotted using antibodies against TRAF2 or TAK1.

-

G, HIn vivo ubiquitination assay of TRAF2 (G) and TAK1 (H) in the absence or presence of PknG in HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h. Cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated using the antibody against Flag. Immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted with the antibody against HA.

Source data are available online for this figure.

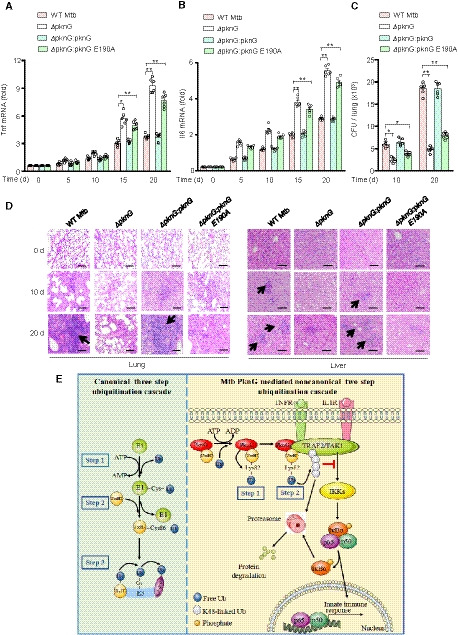

Mtb PknG suppresses immune responses to mycobacteria in vivo

To further examine the contribution of the unconventional E1 and E3 activities of PknG in host innate immune suppression during mycobacterial infection in vivo, C57BL/6 mice were intratracheally challenged with WT Mtb and different PknG‐mutant Mtb strains. Lungs, livers, and spleens were harvested and analyzed at 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20 days after infection. qPCR analyses of splenic cells revealed that the ΔpknG:pknG E190A strain markedly increased Tnf and Il6 mRNA levels in the spleens of infected mice compared to levels in the WT Mtb strain (Fig 7A and B). CFU counting and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining were then performed to evaluate pathologic changes in the lungs and livers. Consistently, the ΔpknG:pknG E190A strain exhibited a decreased bacterial load in the lungs and a reduced cellular infiltration in the lungs and livers of the infected mice at 10 days after infection as compared to levels in the WT Mtb strain (Fig 7C and D). Collectively, these data indicate that the UbcH7 binding‐dependent E1 and E3 enzyme activities of PknG contribute to suppression of innate immune responses in vivo.

Figure 7. The Ubl domain of PknG contributes to host innate immune suppression in vivo .

-

A, BqPCR analysis of Tnf mRNA (A) and Il6 mRNA (B) in splenic cells from C57BL/6 mice infected with WT or mutant Mtb stains for 0–20 days. Data are representative of one experiment with two independent biological replicates (mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice per group). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. Data were analyzed according to one‐way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism 7.

-

CBacterial load in lungs from C57BL/6 mice treated as in (A). Data are representative of one experiment with two independent biological replicates (mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice per group). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. Data were analyzed according to one‐way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism 7.

-

DH&E staining of lungs and livers of C57BL/6 mice treated as in (A). Arrows indicate puncta of cellular infiltration. Scale bars, 200 μm.

-

EProposed model depicting Mtb PknG‐mediated host innate immune suppression. During mycobacterial infection, PknG binds to ATP to catalyze a unique two‐step ubiquitination cascade through unconventional E1 and E3 enzyme activities with the release of ADP instead of AMP, ultimately leading to degradation of TRAF2 and TAK1 and suppression of host innate immune responses.

Discussion

Mycobacterium tuberculosis encounters a hostile environment within the host cells during infection. As the most successful intracellular bacterial pathogen, Mtb not only possesses the ability to adapt to a changing host environment, but also actively interferes with various host signaling pathways and cellular functions to counteract, inhibit, or hijack various killing apparatuses employed by host cells (Cambier et al, 2014; Xu et al, 2014; Brites & Gagneux, 2015; Liu et al, 2017). The intimate and extensive association of Mtb with its host appears to be the driving force in the evolution of its pathogenicity and offers fascinating insight into how pathogens exploit host cellular functions to their advantage (Brites & Gagneux, 2015). One type of powerful tool developed by Mtb to sense and interact with its host is a set of eukaryotic‐type serine/threonine protein kinases and protein tyrosine phosphatases that are potential targets for TB treatment (Av‐Gay & Everett, 2000; Vergne et al, 2005; Soellner et al, 2007; Chao et al, 2010). Mtb PknG has been shown to block phagosome maturation and pathogen clearance in a kinase activity‐dependent manner (Kyei et al, 2006; Pradhan et al, 2018). In this study, by adopting a multidisciplinary approach involving multiple molecular and cellular methodologies as well as mouse infection models, we revealed additional important host‐regulatory roles for Mtb PknG in suppressing innate immune signaling. More strikingly, we determined that the eukaryotic‐type kinase PknG exhibits additional unconventional E1 and E3 enzyme activities that impair innate immune responses during Mtb infection. Thus, PknG represents a powerful mycobacterial effector protein that exerts multifaceted activities in attacking host cellular defense functions including innate immune signaling and phagosome maturation, depending on its distinct eukaryotic‐like enzymatic activities conferred by its specific eukaryotic‐like domains. Such highly flexible and multipronged host‐regulatory functions of the pathogen effector protein may help the pathogen to adapt to and survive within the highly changeable and complicated intracellular environment (Chai et al, 2018). The intricate tactics adopted by these pathogen effector proteins could also reveal new knowledge regarding cell biology, as they act as natural inhibitors or agonists that target host signaling pathways and cellular functions in an unusual but often highly efficient manner.

One of the strategies adopted by pathogenic bacteria to promote their intracellular survival is to secrete diverse effector proteins into host cells. Once they enter into the host cells, these effectors can subvert various cellular processes to destroy host immune defenses. Notably, the ubiquitination pathway is one of the major targets of many bacterial effectors, as ubiquitination is indispensable for eukaryotic cells to regulate diverse immune responses. In addition to regulating the function of crucial enzymes (such as host E1s, E2s, E3s, and DUBs) involved in the host ubiquitination pathway, bacterial pathogens have evolved certain enzymes that function as E3 ligases or DUBs to exploit ubiquitin signaling (Zhou & Zhu, 2015; Qiu et al, 2016; Wan et al, 2019b). Previous studies have suggested that the charged E1~Ub recruits UbcH7 and transfers Ub to the conserved Cys86 residue of UbcH7 (UbcH7 C86‐Ub), which then interacts with HECT (homologous with E6‐associated protein C‐terminus)‐ and RBR (RING‐Between‐RING)‐type E3s to form an intermediate E3~Ub thiol‐ester bond on the conserved cysteine residues in the E3s (Wenzel et al, 2011). Here, we determined that Mtb PknG possesses unconventional E1 and E3 enzymatic activities toward host substrate proteins, including TRAF2 and TAK1, during Mtb infection. Furthermore, unlike any of the previously reported E1s and E3s, Mtb PknG exerts dual‐functional E1 and E3 activities in a unique and sequential manner. Specifically, PknG initially binds to the E2 protein UbcH7 via a novel Ubl domain and exerts unconventional E1 activity to directly catalyze the covalent conjugation of Ub to the Lys82 site of UbcH7 (UbcH7 K82‐Ub), instead of forming a UbcH7 C86‐Ub thiol‐ester bond. PknG further acts as an isopeptidase to discharge Ub from UbcH7 K82‐Ub and then transfers Ub to the recruited substrates (including TRAF2 and TAK1), ultimately leading to ubiquitination‐mediated degradation of TRAF2 and TAK1 and the suppression of NF‐κB signaling. A typical E3 usually binds to its E2 and substrates using distinct domains or regions. Notably, the Ubl domain of PknG binds to its substrates in addition to its E2 UbcH7, thus suggesting that the Ubl domain of PknG possesses an unidentified substrate‐binding region. More strikingly, PknG functions as an unconventional E1 that uses ATP to catalyze E2‐Ub conjugation via an isopeptide bond with the release of ADP instead of AMP, a phenomenon different from that of the conventional E1s that usually use ATP to form Ub‐AMP adducts to facilitate the production of E1‐Ub with the release of AMP (Haas & Rose, 1982; Haas et al, 1982; Schulman & Harper, 2009; Gavin et al, 2012). Furthermore, both WT PknG and the PknG K181M mutant could use ATP to catalyze E2‐Ub conjugation, suggesting that in addition to the previously known ATP‐binding site (Lys 181), there may be a second ATP‐binding motif in PknG that may contribute to the ubiquitinating activity, but not the kinase activity, of PknG. Taken together, during mycobacterial infection, PknG is secreted into host cells to exert multiple enzyme activities (including E1, isopeptidase, and E3 activities) to activate Ub and then promote the ubiquitination of the substrates through two sequential steps. In the first step, PknG acts as an unconventional E1 to catalyze the covalent conjugation of Ub with UbcH7, an E2 protein that is present in high abundance within cells (Clague et al, 2015). PknG then functions as an isopeptidase to release Ub from UbcH7. In the second step, the released Ub is transferred to the substrate by PknG through its E3 activity. Although the net gain of the two reactions in the first step appears to be futile, they provide the activated Ub for the second reaction that requires Ub to ubiquitinate the substrates by E3 activity.

A better understanding of the intimate cross‐talk, antagonism, and co‐evolution of Mtb with its host could be exploited for the development of novel TB treatments. Such pathogen–host interface‐based novel therapies could be effective for both drug‐susceptible and drug‐resistant TB. Such a strategy of targeting secreted pathogen effectors instead of pathogen essential genes could help minimize further development of mycobacterial drug resistance, and this is important considering the growing challenges regarding antibacterial drug resistance worldwide (Machelart et al, 2017; Lange et al, 2018).

In summary, our study demonstrates that Mtb PknG possesses unconventional E1 and E3 activities that allow it to attack host innate immunity by catalyzing a novel two‐step ubiquitination cascade (Fig 7E). Importantly, we determined that the Ubl domain of Mtb PknG was highly conserved among Mtb clinical isolates, as analyzed using the GMTV database (http://mtb.dobzhanskycenter.org) (Dataset EV2) (Chernyaeva et al, 2014). We also revealed that the Ubl domain (particularly its E190 site) of Mtb PknG exhibited high homology to some other pathogenic mycobacteria, little homology to non‐pathogenic mycobacteria, and no homology to human hosts as analyzed against the Uniport Reference Proteomes database (Dataset EV3). These features may make PknG selectively targeted. The findings from this study suggest a potential TB treatment that involves targeting the unconventional E1 and E3 activities of Mtb PknG.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, mammalian cell lines, and plasmids

Escherichia coli DH5α and BL21 (DE3) strains were used for genetic manipulation and protein overexpression, respectively. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) H37Rv was used for infection. PknG deletion and mutant strains of Mtb were created as described previously (Wang et al, 2015). Mtb strains included wild‐type (WT) Mtb, pknG‐deleted Mtb (ΔpknG), Mtb ΔpknG complemented with WT pknG (ΔpknG:pknG), pknG K181M (ΔpknG:pknG K181M, which is a kinase‐dead mutant), pknG E190A (ΔpknG:pknG E190A, which is a mutant that does not interact with UbcH7), pknG ΔTPR (ΔpknG:pknG ΔTPR, from which the TPR domain was deleted), and pknG K181M, E190A (ΔpknG:pknG K181M, E190A, which does not possess kinase activity and does not interact with UbcH7). Gene sequencing was used to confirm the mutation, deletion, or truncation of PknG in Mtb strains. The expression of PknG in infected host cells was examined by immunoblotting. HEK293T cells (ATCC CRL‐3216) and the human monocytic cell line U937 cells (ATCC CRL‐1593.2) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). For expression in mammalian cells, pknG or its mutants were amplified by PCR and cloned into pEGFP‐N1 (with GFP‐tag) or p3xFlag‐CMV14 (with Flag‐tag) vectors. Bacterial expression plasmids were constructed by cloning cDNA into pET30a (with His6‐tag) or pGEX‐6P‐1 (with GST tag). Site‐directed mutagenesis of pknG was performed using the Mut Express II Fast Mutagenesis Kit V2 (Vazyme). All plasmids were sequenced at the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) for verification. The strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Appendix Table S1.

Antibodies

All antibodies were used according to the manufacturer's instructions and based on previous experiences in the laboratory. Rabbit anti‐PknG antibody was produced and purified by GenScript Biotechnology with the recombinant GST‐tagged PknG protein as an immunogen (1/10,000 for immunoblotting, 1/200 for immunohistochemistry). The following commercial antibodies were used: anti‐UbcH7 (A300‐737A, Bethyl), 1:2,000 for immunoblotting; anti‐Flag (F1804, Sigma), 1:5,000 for immunoblotting; anti‐GST (TA‐03, ZSGB‐BIO), 1:5,000 for immunoblotting; anti‐ubiquitin (131600, Invitrogen), 1:2,000 for immunoblotting; anti‐His (TA‐02, ZSGB‐BIO), 1:2,000 for immunoblotting; anti‐GFP (ab1218, Abcam), 1:2,000 for immunoblotting; anti‐TRAF2 (SAB3500375, Sigma), 1:2,000 for immunoblotting; anti‐TAK1 (12330‐2‐AP, Proteintech), 1:1,000 for immunoblotting; anti‐GAPDH (sc‐25778, Santa Cruz), 1:5,000 for immunoblotting; anti‐HA (3724, Cell signaling), 1:2,000 for immunoblotting; anti‐Rv3134 (sc‐52107, Santa Cruz), 1:1,000 for immunoblotting; anti‐Ag85B (ab43019, Abcam), 1:1,000 for immunoblotting; anti‐TAB3 (sc‐67112, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 1:1,000 for immunoblotting; anti‐TAB2 (BF 0376, Affinity Biosciences), and 1:1,000 for immunoblotting.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

For GST or His fusion proteins, E. coli BL21 (DE3) strains harboring pGEX‐6P‐1 or pET30a derivatives were cultivated in LB medium supplemented with antibiotics for 3 h at 30°C. Protein expression was induced using 1 mM IPTG for 3 h at 30°C. GST fusion protein and His fusion protein were purified with glutathione‐Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) and Ni‐NTA Agarose (QIAGEN), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Protein concentrations were determined by the BCA protein assay (Pierce), and protein purity was examined by SDS–PAGE analysis.

For Flag fusion proteins, HEK293T cells transfected with pCMV14‐3flag‐TARF2 or pCMV14‐3flag‐TAK1 were lysed and incubated with ANTI‐FLAG M2 affinity gel (A2220, Sigma) for 6 h at 4°C. After washing away residual impurities, bound Flag‐tagged proteins were eluted from the affinity column using high concentrations of the Flag‐tag peptide. The eluent was then concentrated to remove the detergent and Flag‐tag peptide using a centrifugal filter (MW 30000, Amicon Ultra, Millipore). The concentrated proteins were then diluted to 1 ml and incubated with ANTI‐FLAG M2 affinity gel at 4°C. After 6 h, the above elution and concentration steps were repeated to obtain Flag fusion proteins.

Cell culture and bacteria cultivation

HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FBS). U937 cells were maintained in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Prior to infection, U937 cells were differentiated into adherent macrophage‐like cells using 10 ng/ml PMA (Sigma) for 24 h. Escherichia coli DH5α and BL21 (DE3) cells were grown in LB medium. Mtb strains were cultivated in Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with 10% oleic acid‐albumin‐dextrose‐catalase (OADC) and 0.05% Tween‐80 (Sigma) or on Middlebrook 7H10 agar (BD) supplemented with 10% OADC.

Preparation of U937 cells and primary human monocyte‐derived macrophage cells

U937 cells were differentiated by treatment with 10 ng/ml PMA, washed twice with PBS, and further cultured in fresh medium for an additional 2 h prior to infection. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were prepared from venous blood obtained from healthy volunteer donors using density gradient centrifugation. All experiments involving human subjects were approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Written informed consent was obtained from all donors. For differentiation into macrophages, monocytes (2 × 106) were cultured in 500 µl RPMI1640 with 10% FBS, 4 mM l‐glutamine, and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Invitrogen) in 24‐well plates for 7 days. Recombinant human macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (M‐CSF) was added at days 0, 2, and 4. After 7 days, macrophages were used for mycobacterial infection.

qPCR

Primary human monocyte‐derived macrophages were infected with WT, ΔpknG, ΔpknG:pknG, ΔpknG:pknG K181M, ΔpknG:pknG E190A, or ΔpknG:pknG K181M, E190A Mtb strains at an MOI of 1 for 0–24 h. Total RNA was extracted from the infected cells using a Total mRNA isolation kit (R1061, Dongsheng), and the RNA was reverse‐transcribed into cDNA using the Hieff First Strand cDNA Synthesis Super Mix (11103ES70, YEASEN). The cDNA was then analyzed by qPCR using Hieff qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (11202ES08, YEASEN) on an ABI 7500 system (Applied Biosystems). Each experiment was performed in triplicate was repeated at least three times. Data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method and normalized to the expression of the control gene GAPDH.

Ub‐charging reaction

Reaction mixtures containing 2 µM PknG or its mutants (purified from E. coli), 5 µM Ub (U‐100H, Boston Biochem), 5 µM UbcH7 (E2‐640, BostonBiochem) in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP (A6559, Sigma) or the ATP analogs including APCPP (M6517, Sigma), AMPPNP (A2647, Sigma), and ATP‐γ‐S (A1388, Sigma) were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Samples were quenched in a non‐reducing loading buffer and analyzed by SDS–PAGE.

In vitro autophosphorylation of PknG and its mutants

GST‐tagged PknG or its mutants (5 µg) were incubated in 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 2 mM MnCl2, 1 mM DTT, and 200 µM ATP for 30 min at 37°C. The reactions were halted by adding sample buffer and boiling for 10 min at 95°C. The samples were resolved by SDS–PAGE on 10% gels and subjected to immunoblotting.

LC‐MS

Reaction mixtures containing 2 µM GST‐tagged PknG K181M (purified from E. coli) and 5 µM ATP (A6559, Sigma) in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2) were incubated at 37°C for 30 min in the presence or absence of 5 µM Ub (U‐100H, Boston Biochem) and 5 µM UbcH7 (E2‐640, BostonBiochem). Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC‐MS) data were acquired using a 6500 QTRAP triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems/Sciex) coupled to an ExionLC LC system (Applied Biosystems/Sciex) using Rezex RCM‐Monosaccharide Ca+ (Phenomenex, 300 × 7.8 mm). Compounds were eluted with isocratic elution of water at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min over 40 min. MS analyses were performed using electrospray ionization (ESI) and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) scans in the negative‐ion mode. The injection volume was 5.0 µl. The dwell time for each transition was 50 ms, the ion spray voltage was 4.5 kV, and the source temperature was 550°C. The file was created using the Analyst software (version 1.6.3, Applied Biosystems/Sciex). The peak area ratios of the compounds were calculated using the MultiQuant software (Version 3.0.2; Applied Biosystems/Sciex).

Mass spectrometry for determination of ubiquitination sites

Bands were excised from the SDS–PAGE gel, rinsed with 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, dried, and reduced using 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate at 56°C, and then alkylated with 55 mM iodoacetamide. Proteins were then digested with 12.5 ng/µl trypsin overnight at room temperature. After trypsinization, the proteins were eluted from the gel by alternating four times between 50% acetonitrile, 5% formic acid, and 50 mM sodium bicarbonate, and then an additional three times alternating between 100% acetonitrile and 50 mM NH4CO3. Samples were next desalted on a C18 ZipTip pipette tip (Millipore) and lyophilized for mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. Peptides were separated via Nano LC‐MS/MS analysis on a NanoAcquity system (Waters, Milford, MA) connected to an LTQ‐Orbitrap XL hybrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). The MS and MS/MS raw data were processed using Proteome Discoverer (Version 1.4.0.288, Thermo Fischer Scientific) and searched against the customized Uniprot_M. tuberculosis_GNCC_2019 database. Peptide ubiquitination sites were identified via protein database searching of the resulting tandem mass spectra using Mascot. The Mascot search engine was used to identify ubiquitinated residues marked as LeuArgGlyGly (LRGG) or GlyGly (GG). The mass spectrometry data were deposited in the Proteomics Identification Database (PRIDE) under the accession number PXD020982.

Nucleophile reactivity assays

Reactions containing 2 µM GST‐tagged PknG or E1 (purified from E. coli), 5 µM Ub (U‐100H, Boston Biochem), and 5 µM UbcH7 (E2‐640, BostonBiochem) in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2/ATP) were incubated at 37°C. After 30 min, GST‐E1 and GST‐PknG were removed from the reaction using glutathione‐Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare). Next, reaction mixtures containing 5 µM ubiquitin conjugation UbcH7 (UbcH7~Ub) (charged by GST‐tagged E1 or Mtb PknG) and 20 mM of l‐lysine monohydrochloride in 50 mM Tris/HCl buffer (pH 7.4) in the presence or absence of PknG or PknG I87A mutant were incubated for 0–60 min at 37°C. The samples were quenched in a non‐reducing loading buffer and analyzed by SDS–PAGE.

In vitro isopeptidase activity assay

Reaction mixtures containing 1 µM ubiquitin‐conjugated UbcH7 (UbcH7~Ub) (which is charged by GST‐tagged Mtb PknG), 2 nM purified GST or GST‐PknG, and 20 mM l‐lysine monohydrochloride in 50 mM Tris/HCl buffer (pH 7.4) were incubated in the presence or absence of ubiquitin–aldehyde (6 nM, Abcam) for 30 min at 37°C. The samples were resolved using 10% SDS–PAGE.

Luciferase reporter assay

Luciferase reporter assays were performed in the presence or absence of 1 μg of PknG plasmid as described previously (Wang et al, 2015). The fold induction was calculated as [relative FU stimulated]/ [relative FU unstimulated].

Pull‐down assay

The recombinant proteins were added to 20 μl of glutathione resin (for GST‐tagged proteins) in 500 μl of binding buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, and 0.1% NP‐40) supplemented with 1% protease inhibitors for 1 h at 2°C. The beads were washed five times with binding buffer and further incubated with prey protein supplemented with 0.1 mg/ml of BSA (the molar ratio of GST‐tagged protein and prey protein is 1:1). After 2 h of incubation at 4°C, the beads were washed and subjected to immunoblotting.

Immunoblotting, CFU counting, qPCR, and enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analyses of infected macrophage cells

Macrophage cells were infected with Mtb strains at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 for 0–24 h. Immunoblotting, CFU counting, qPCR, and ELISA analyses of infected macrophage cells were all performed as described previously (Wang et al, 2015). The PCR primers used are listed in Appendix Table S1. ELISA kits (Human TNF ELISA kit: ELH‐TNF‐1, Ray Biotech; Human IL‐6 ELISA kit: ELH‐IL6‐1, Ray Biotech) were used for ELISA analysis according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunoprecipitation

For assays using HEK293T, the cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 24 h. For assays using U937 cells, the cells were infected with Mtb strains at an MOI of 1. After 1 h, the cells were washed with 1× PBS three times to exclude non‐internalized bacteria, and they were then incubated in the fresh RPMI 1640 medium for an additional 4 h. HEK293T and U937 cells were both lysed in western and immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (Beyotime) for 10 min at 4°C. Cell lysates were then incubated with Flag M2 beads (Sigma), anti‐HA affinity matrix (Roche), GFP‐Nanoab‐Agarose (V‐Nanoab), or PknG antibody‐protein A/G agarose at 4°C, and this was followed by extensive washing with Western and IP buffer. Immunoprecipitated samples were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies.

Yeast two‐hybrid assay

The yeast two‐hybrid assay was performed using the Matchmaker Two‐Hybrid System (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A mouse 7‐day embryo cDNA library (CATALOG No. 630478; Clontech Laboratories, Inc.) was used to identify host interaction proteins of Mtb PknG using a yeast two‐hybrid assay. The Mtb PknG gene was subcloned into the plasmid pGBKT7 as the bait plasmid. Saccharomyces cerevisiae AH109 cells were co‐transduced with bait plasmids and prey plasmids using the lithium acetate method. To test the interactions between proteins, the transformants were streaked onto low‐stringency (lacking leucine and tryptophan) and high‐stringency (lacking adenine, histidine, leucine, and tryptophan) selection plates.

In vitro ubiquitination assays

In vitro ubiquitination assays of Flag‐tagged TRAF2 and TAK1 were performed in 40 μl reaction mixtures containing reaction buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, with or without ATP), 1 μg of TRAF2 or TAK1, 2 μg of UbcH7, and 2 μg of His‐Ub (or 4 μg Ub‐conjugated UbcH7) in the presence or absence of WT PknG or its mutants. To obtain Ub‐conjugated UbcH7, reactions containing 2 µM GST‐tagged PknG (purified from E. coli), 5 µM Ub (U‐100H, Boston Biochem), and 5 µM UbcH7 (E2‐640, BostonBiochem) in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2/ATP) were incubated at 37°C. After 30 min, GST‐PknG was removed from the reaction using glutathione‐Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare). The reactions were incubated at 30°C for 2 h, and the reactions were terminated by adding SDS sample buffer without β‐mercaptoethanol and heating at 100°C for 5 min. The samples were resolved by SDS–PAGE and then subjected to immunoblotting.

In vivo ubiquitination assays

In vivo ubiquitination assays were performed using U937 or HEK293T cells. For assays with U937 cells, and the cells were infected with WT, ΔpknG, ΔpknG:pknG, or ΔpknG:pknG E190A Mtb strains at an MOI of 1 for 2 h. After another 2 h, the medium was discarded. The cells were then washed three times with PBS to exclude non‐internalized bacteria and cultured in fresh RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 5 μM MG132 for an additional 4 h. Cells were lysed in Western and IP buffer (Beyotime) and centrifuged at 12,000 g, and the equilibrated agarose‐TUBEs (10–20 µl) were then incubated with lysate at 4°C. After 4 h, the agarose‐TUBEs were washed for five times with TBS–T buffer and treated with 0.2 M glycine HCl (pH 2.5) for at least 1 h on a rocking platform at 4°C. The agarose‐TUBEs were then collected by high‐speed centrifugation (13,000 g) for 5 min, and the supernatants were resolved by SDS–PAGE and subsequently subjected to immunoblotting.

For assays using HEK293T cells, the cells were transfected with Flag‐TRAF2 (or Flag‐TAK1) and other indicated plasmids for 24 h. Cells were lysed in western and IP buffer (Beyotime) and centrifuged at 12,000 g. The pre‐washed anti‐FLAG M2 beads were incubated with the supernatant for 2 h at 4°C to pull‐down Flag‐tagged TRAF2 (or TAK1) and its conjugated proteins. The beads were then washed with western and IP buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Murine infection

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Vital River (Beijing) and were maintained using standard humane animal husbandry protocols. The mice were 6–8 weeks old during the course of the experiments and were age‐ and sex‐matched in each experiment. The sample size was based on empirical data from the pilot experiments. No additional randomization or blinding was performed to allocate the experimental groups. All experimental protocols were performed in accordance with the instructional guidelines of the China Council on Animal Care and were approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the Beijing Chest Hospital, Capital Medical University. The mice were intratracheally infected with 1 × 105 CFU of Mtb per mouse in 25 µl PBST. Lungs, livers, and spleens were harvested and analyzed as previously described (Wang et al, 2015). Staining with H&E staining was performed to evaluate tissue pathologic changes in a blinded fashion by a pathologist. Splenic cells were used for qPCR, and lung cells were used for CFU analysis.

Data analysis

We analyzed Mtb pknG gene sequence conservation among Mtb clinical isolates using the GMTV database (http://mtb.dobzhanskycenter.org). To acquire greater specificity and a lower rate of false‐positive homologous proteins, we used the phmmer tool based on the hidden Markov model against the Uniport Reference Proteomes database to predict homologous proteins of Mtb PknG in Homo sapiens and all bacterial species. Only alignments with E‐values of < 10−2 were considered to represent homologous proteins.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7. All data were analyzed using an unpaired Student’s t‐test or one‐way ANOVA with Bonferroni post‐test to correct for multiple comparisons, as indicated in the corresponding figure legends. The results were averaged and are expressed as mean values with SEM. Values of *P < 0.05 or **P < 0.01 were considered statistically significant.

Author contributions

CHL conceived and supervised the study. CHL, JW, X‐BQ, and GFG designed the experiments. JW, PG, and ZHL performed the majority of the experiments. ZL, LQ, QC, YZ, DZ, BL, JS, RP, YP, YS, and YZ were involved in specific experiments. CHL, JW, and X‐BQ analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Dataset EV1

Dataset EV2

Dataset EV3

Source Data for Figures

Source Data for Expanded View and Appendix

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 1

Source Data for Figure 2

Source Data for Figure 3

Source Data for Figure 5

Source Data for Figure 6

Acknowledgements

We thank Xiang Ding (Laboratory of Proteomics, Core Facility of Protein Science, Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences) and Ying Fu (Public Technology Service Center, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for the ubiquitination modification analysis with mass spectrometry. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31830003, 81825014, 82022041, and 81871616), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB29020000), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2019YFA0802100, 2017YFA0505900 and 2017YFD0500300), the National Science and Technology Major Project (2018ZX10101004), and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (Y82R011CX3).

EMBO reports (2021) 22: e52175.

See also: L Song & ZQ Luo (June 2021)

Contributor Information

George Fu Gao, Email: gaof@im.ac.cn.

Xiao‐Bo Qiu, Email: xqiu@bnu.edu.cn.

Cui Hua Liu, Email: liucuihua@im.ac.cn.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry data were deposited in the Proteomics Identification Database (PRIDE) under the accession number PXD020982 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD020982).

References

- Av‐Gay Y, Everett M (2000) The eukaryotic‐like Ser/Thr protein kinases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Trends Microbiol 8: 238–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhogaraju S, Bonn F, Mukherjee R, Adams M, Pfleiderer MM, Galej WP, Matkovic V, Lopez‐Mosqueda J, Kalayil S, Shin D et al (2019) Inhibition of bacterial ubiquitin ligases by SidJ‐calmodulin catalysed glutamylation. Nature 572: 382–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brites D, Gagneux S (2015) Co‐evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Homo sapiens. Immunol Rev 264: 6–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs AM, Iyer LM, Aravind L (2012) The natural history of ubiquitin and ubiquitin‐related domains. Front Biosci 17: 1433–1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambier CJ, Falkow S, Ramakrishnan L (2014) Host evasion and exploitation schemes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Cell 159: 1497–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Q, Zhang Y, Liu CH (2018) Mycobacterium tuberculosis: an adaptable pathogen associated with multiple human diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8: 158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao J, Wong D, Zheng X, Poirier V, Bach H, Hmama Z, Av‐Gay Y (2010) Protein kinase and phosphatase signaling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis physiology and pathogenesis. Biochem Biophys Acta 1804: 620–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaurasiya SK, Srivastava KK (2009) Downregulation of protein kinase C‐alpha enhances intracellular survival of Mycobacteria: role of PknG. BMC Microbiol 9: 271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernyaeva EN, Shulgina MV, Rotkevich MS, Dobrynin PV, Simonov SA, Shitikov EA, Ischenko DS, Karpova IY, Kostryukova ES, Ilina EN et al (2014) Genome‐wide Mycobacterium tuberculosis variation (GMTV) database: a new tool for integrating sequence variations and epidemiology. BMC Genom 15: 308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clague MJ, Heride C, Urbe S (2015) The demographics of the ubiquitin system. Trends Cell Biol 25: 417–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dove KK, Olszewski JL, Martino L, Duda DM, Wu XS, Miller DJ, Reiter KH, Rittinger K, Schulman BA, Klevit RE (2017) Structural studies of HHARI/UbcH7 approximately Ub reveal unique E2 approximately Ub conformational restriction by RBR RING1. Structure 25: 890–900.e895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin JM, Chen JJ, Liao H, Rollins N, Yang X, Xu Q, Ma J, Loke H‐K, Lingaraj T, Brownell JE et al (2012) Mechanistic studies on activation of ubiquitin and di‐ubiquitin‐like protein, FAT10, by ubiquitin‐like modifier activating enzyme 6, Uba6. J Biol Chem 287: 15512–15522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AL, Rose IA (1982) The mechanism of ubiquitin activating enzyme. A kinetic and equilibrium analysis. J Biol Chem 257: 10329–10337 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AL, Warms JV, Hershko A, Rose IA (1982) Ubiquitin‐activating enzyme. Mechanism and role in protein‐ubiquitin conjugation. J Biol Chem 257: 2543–2548 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A, Ciechanover A (1998) The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem 67: 425–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser M (2009) Origin and function of ubiquitin‐like proteins. Nature 458: 422–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerscher O, Felberbaum R, Hochstrasser M (2006) Modification of proteins by ubiquitin and ubiquitin‐like proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 22: 159–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyei GB, Vergne I, Chua J, Roberts E, Harris J, Junutula JR, Deretic V (2006) Rab14 is critical for maintenance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome maturation arrest. EMBO J 25: 5250–5259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange C, Chesov D, Heyckendorf J, Leung CC, Udwadia Z, Dheda K (2018) Drug‐resistant tuberculosis: an update on disease burden, diagnosis and treatment. Respirology 23: 656–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Chai QY, Liu CH (2016) The ubiquitin system: a critical regulator of innate immunity and pathogen‐host interactions. Cell Mol Immunol 13: 560–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CH, Liu H, Ge B (2017) Innate immunity in tuberculosis: host defense vs pathogen evasion. Cell Mol Immunol 14: 963–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machelart A, Song OR, Hoffmann E, Brodin P (2017) Host‐directed therapies offer novel opportunities for the fight against tuberculosis. Drug Discovery Today 22: 1250–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napetschnig J, Wu H (2013) Molecular basis of NF‐kappaB signaling. Annu Rev Biophys 42: 443–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L, Pieters J (2005) The Trojan horse: survival tactics of pathogenic mycobacteria in macrophages. Trends Cell Biol 15: 269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan G, Shrivastva R, Mukhopadhyay S (2018) Mycobacterial PknG targets the Rab7l1 signaling pathway to inhibit phagosome‐lysosome fusion. J Immunol 201: 1421–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prisic S, Husson RN (2014) Mycobacterium tuberculosis serine/threonine protein kinases. Microbiol Spectr 2: 681–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Sheedlo MJ, Yu K, Tan Y, Nakayasu ES, Das C, Liu X, Luo ZQ (2016) Ubiquitination independent of E1 and E2 enzymes by bacterial effectors. Nature 533: 120–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherr N, Honnappa S, Kunz G, Mueller P, Jayachandran R, Winkler F, Pieters J, Steinmetz MO (2007) Structural basis for the specific inhibition of protein kinase G, a virulence factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 12151–12156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman BA, Harper JW (2009) Ubiquitin‐like protein activation by E1 enzymes: the apex for downstream signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 319–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soellner MB, Rawls KA, Grundner C, Alber T, Ellman JA (2007) Fragment‐based substrate activity screening method for the identification of potent inhibitors of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis phosphatase PtpB. J Am Chem Soc 129: 9613–9615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura M, Rieck B, Boldrin F, Degiacomi G, Bellinzoni M, Barilone N, Alzaidi F, Alzari PM, Manganelli R, O'Hare HM (2013) GarA is an essential regulator of metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Mol Microbiol 90: 356–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergne I, Chua J, Lee HH, Lucas M, Belisle J, Deretic V (2005) Mechanism of phagolysosome biogenesis block by viable Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 4033–4038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walburger A, Koul A, Ferrari G, Nguyen L, Prescianotto‐Baschong C, Huygen K, Klebl B, Thompson C, Bacher G, Pieters J (2004) Protein kinase G from pathogenic mycobacteria promotes survival within macrophages. Science 304: 1800–1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan M, Sulpizio AG, Akturk A, Beck WHJ, Lanz M, Faca VM, Smolka MB, Vogel JP, Mao Y (2019a) Deubiquitination of phosphoribosyl‐ubiquitin conjugates by phosphodiesterase‐domain‐containing Legionella effectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116: 23518–23526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan M, Wang X, Huang C, Xu D, Wang Z, Zhou Y, Zhu Y (2019b) A bacterial effector deubiquitinase specifically hydrolyses linear ubiquitin chains to inhibit host inflammatory signalling. Nat Microbiol 4: 1282–1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Li BX, Ge PP, Li J, Wang Q, Gao GF, Qiu XB, Liu CH (2015) Mycobacterium tuberculosis suppresses innate immunity by coopting the host ubiquitin system. Nat Immunol 16: 237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehenkel A, Bellinzoni M, Graña M, Duran R, Villarino A, Fernandez P, Andre‐Leroux G, England P, Takiff H, Cerveñansky C et al (2008) Mycobacterial Ser/Thr protein kinases and phosphatases: physiological roles and therapeutic potential. Biochem Biophys Acta 1784: 193–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]