Abstract

We present three studies examining death in children’s animated films. Study 1 is a content analysis of 49 films. We found that death is often portrayed in films, but many deaths occurred off-screen. Deaths were mostly portrayed in a biologically accurate manner, but some films portrayed biological misconceptions. Study 2 (n = 433) reports on parents’ attitudes and parent-child conversations about death in films. Children’s questions about death in animated films were similar to their questions about death more generally. Animated films may provide a context for parent-child conversations about death, as parents often watched these films with their children. However, it appeared that few parents took advantage of this opportunity to talk about death with their children.

Keywords: death, media, conceptual development, parent-child conversations

Children’s understanding of death has received considerable attention in the cognitive developmental literature as it is critical for children’s understanding of the biological world (Inagaki & Hatano, 1993). Focusing on this domain also enables researchers to examine how children’s thinking varies as a function of cultural and religious practices (e.g., Bering et al., 2005; Gutiérrez et al., 2020; Panagiotaki et al., 2015). One potential manner in which cultural views on death may be conveyed to children is through animated media, and some researchers (Cox et al., 2005) have suggested that animated films may be a useful tool for parents to start conversations about death. The goal of the present research was to explore how death is portrayed in animated films targeted to children and whether parents actually use these films to talk about death.

Understanding of Death

To study children’s understanding of death, researchers have focused on four biological sub-concepts (Speece & Brent, 1984): (1) finality/irreversibility (i.e., when something dies, it cannot come back to life), (2) universality (i.e., all living things die), (3) non-functionality (i.e., biological and psychological functions cease at death), and (4) causality (i.e., death can occur in many ways). Past research suggests that children’s understanding of these sub-concepts increases with age, but that they have some understanding of universality and finality by the age of 3 (Panagiotaki et al., 2018; Rosengren et al., 2014). A few researchers have examined religious/spiritual perspectives of death, such as the continued existence of the soul after death, which tend to appear later in life (e.g., Bering et al., 2005; Busch et al., 2017; Harris & Giménez, 2005; Rosengren et al., 2014). Researchers have also examined how these biological and spiritual models of death co-exist in the minds of children (Gutiérrez et al., 2020; Legare et al., 2012).

Researchers have identified differences in how children are socialized with respect to the concept of death. For example, parents in the United States often shield young children from information about death (Rosengren et al., 2014), while parents in Mexico talk openly about death and actively engage children in death rituals (Gutiérrez et al., 2015; Gutiérrez et al., 2020). Given the cultural similarities and differences in children’s understanding of death, more recent research has focused on how children come to learn about death.

How Might Children Learn about Death?

Current theoretical accounts of children’s understanding of death posit that children learn about death as they gain a richer understanding of biological phenomena, and more specifically through direct experiences with dead organisms. For example, teaching children about biological phenomena such as what functions are necessary for life promotes children’s understanding of death, suggesting that advances in their understanding of death is related to advances in their biological reasoning (Slaughter & Lyons, 2003). Research has also examined how children’s experiences with the death of a pet or a loved one influences their understanding of death (Panagiotaki et al., 2018; Rosengren et al., 2014). Children may also come to gain a better understanding of death from their experiences with representations of death in different forms of media, conversations with parents, and participation in cultural rituals (Longbottom & Slaughter, 2018; Menendez et al., 2020). In this paper, we focus on one factor that has received relatively little attention in empirical literature, namely children’s experience with animated films.

Taking a sociocultural approach, we examine how representations of death in children’s media might influence their understanding of death. Similar to how parents’ attitudes towards talking to their children about death are reflective of broader cultural norms (Rosengren et al., 2014), children’s animated films, as cultural products, likely reflect cultural norms and values about death. Therefore, children might be learning culturally appropriate information about death by watching these films. In addition, children likely do not watch animated films in isolation, but rather they might watch them with their parents. Thus, in this paper, we examine how death is represented in children’s media and how parents and children interact in the context of these representations.

Death in Children’s Media

There is a long history in developmental psychology of characterizing the information in children’s environments as a way to understand child development within a specific context (e.g., Mix, 2009; Tomasello, 1992; Walsh & Leaper, 2020). The media produced within a culture often reflects the norms and values of that culture (Lee et al., 2014). One form of media, children’s books, has received some attention with respect to how death is portrayed. In general, analyses of children’s books produced in the United States have shown a lack of death portrayals. For example, Gutiérrez et al. (2014) analyzed US children's favorite books and Caldecott Medal winners and found that only 6 of 198 (3%) of the books contained deaths. This lack of deaths in mainstream children’s books matches US parents’ tendency to shield their children from death-related information, suggesting that parents and the larger culture implicitly and explicitly shield young children from images and experiences related to death.

Representations of death are more common in books designed to discuss death with children who have recently lost a loved one. However, there are interesting differences across cultures in these death-themed books. Death-themed books from countries like China display fewer supernatural aspects of death compared to books from countries like the United States (Lee et al., 2014). This matches the frequency of supernatural explanations of death provided by individuals in China and the United States (Lane et al., 2016). This research suggests that death representations in media reflect to some degree the prevalent cultural attitudes and beliefs towards how and what is discussed in parent-child conversations about death.

Given that parents in the United States often attempt to shield children from death under the assumption that children are too young to cognitively and emotionally cope with death, we might expect that this shielding of children from death would be reflected in few deaths being presented in animated films designed for young children.

Past research on animated films focused only on films that contain death scenes (Cox et al., 2005; Tenzek & Nickels, 2017). These studies found that the majority of deaths in animated films are implicit (i.e., they do not actually show the character dying and leave open whether the individual died or not) and occur to minor characters (Cox et al., 2005; Tenzek & Nickels, 2017). These two facts suggest that children might not realize a character died. Additionally, some films contained misconceptions about death such as presenting death as a deep sleep or having the deceased come back to life, either as the same person or in an altered form (Tenzek & Nickels, 2017). However, because Cox et al. (2005) and Tenzek and Nickels (2017) only focused on films that contained deaths, it is impossible to determine how prevalent deaths are in animated films. Additionally, the presence of misconceptions suggests that it is important to examine not only whether death is portrayed but how it is portrayed.

In order to examine how death is portrayed in animated films, we focused on dimensions that are most relevant to children’s understanding of death. In particular, we examined how films represent the sub-concepts of death and whether they contain any spiritual or religious information. We also examined whether films display some common misconceptions about death such as equating death with sleep.

Parent-Child Conversations

Parent-child interactions have been found to be critical in many areas of development. For example, Callanan et al. (2017), showed that parents’ causal talk is related to their children’s exploration of museum exhibits. Additionally, parents’ correct responses to biology questions predicts their children’s biological knowledge (Mills et al., 2020). Parents’ beliefs are also important as parents often convey information to their children that is consistent with their own beliefs and broader cultural beliefs (Hernandez et al., 2020). Harris and Koenig (2006) have suggested that testimony from adults may help children learn about concepts such as death, which are partly unobservable. Therefore, how parents interact with their children might shape children’s thinking and behavior in important ways.

Parent-child interactions are also critical in determining how much children will learn from media. Children younger than nine tend to focus on the concrete elements of a story and miss the bigger picture such as the moral of the story (Goldman et al., 1984). While children can understand broader messages contained in media, they require adult scaffolding to do so effectively (e.g., Mares & Acosta, 2010). Parents can provide this scaffolding and help children learn from media (Kirkorian et al., 2008; Sheehan et al., 2019; Valkenburg et al., 1998). This means that whether or not children learn about death from films might depend on whether parents watch the films with them and are willing to have discussions with their children.

Research on parent-child conversations about death has primarily focused on clinical outcomes. These studies suggest that open communication between children and parents aids children to cope with the death of a loved one (Field et al., 2014; Martinčeková et al., 2020). For this reason, parent-child conversations have been identified as a key mechanism in children’s development of an understanding of death (Menendez et al., 2020; Rosengren et al., 2014). Indeed, past clinical work with bereaved families has identified parents as a key resource in helping children to cope with the emotional aspects of death (Grollman, 2011; Webb, 2010).

In the cognitive developmental literature, work on parent-child conversations about death has focused on children’s questions and parents’ responses (Renaud et al., 2015; Rosengren et al., 2014). This focus on question-asking assumes that children ask questions to fill conceptual gaps and promote their own conceptual development (Chouinard, 2007). As children acquire more domain knowledge, their ability to ask questions improves and they ask more focused questions to fill specific knowledge gaps (Ronfard et al., 2018; Ruggeri & Feufel, 2015). Children have been shown to tailor their questions to the person they are asking (e.g., asking other children about toys, but asking adults about causal relations; VanderBorght & Jaswal, 2009). Gutiérrez et al. (2020) reported that children tend to ask parents questions about the sub-concepts of death, particularly causality. Similarly, Christ (2000) found that grieving children asked questions regarding the individual who had died and whether this individual could return (i.e., finality). Therefore, it seems that children do ask questions about death, and their questions are often focused on the biological aspects of death. However, it is unclear whether children ask similar questions about deaths that occur in animated films.

Although prior work has examined when children start asking questions about death and the content of these questions, no study has yet examined how their questions might vary depending on the context. In this paper, we examined children’s questions about death generally (similar to prior work by Gutiérrez et al., 2020 and Rosengren et al., 2014), but also their questions about death in the specific context of animated films. This allows us to examine how the content of death-related conversations might differ by context. Additionally, we examined parental responses in order to investigate how their responses to children’s questions might vary in different contexts.

Parental Attitudes

Given the importance of parent-child conversations, it is necessary to also examine when parents decide to engage in these conversations with their children. For example, parents who feel more efficacious are more likely to engage in educational activities with their children (Grolnick et al., 1997). Parents’ own motivations and their awareness that an issue is important also increases the likelihood that they engage in these conversations with their children (Perry et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2020). Additionally, whether parents engage in conversations with their children also seems to depend on sociodemographic factors. For example, parents in affluent communities tend to shield their children from information about violence more than parents in low-income communities (e.g., Miller, 1994; Miller et al., 2011; Miller & Sperry, 1987; Wiley et al., 1998).

Parental attitudes might also be important in predicting which parents talk about death. Many parents in the United States report shielding their children from information about death because they think their children are too young to understand and cope with this information (Rosengren et al., 2014). Therefore, parents’ willingness to engage in conversations about death with their children might depend on the age of their children. Additionally, some studies suggest that parents’ religious beliefs influence the information they convey to their children during death-related conversations, with religious parents being more likely to mention themes such as “God’s plans” (Zajac & Boyatzis, 2020). This research suggests that sociodemographic factors might affect both the likelihood that parents engage in conversations with their children and the content of the conversations they choose to engage in. Our study examined how parental attitudes towards death in animated films and factors such as parents’ socioeconomic status and religiosity, and children’s age, relate to parent-child conversations about death in animated films.

Current Studies

The current studies attempt to provide empirical support for theoretical accounts on how children come to understand death (e.g., Menendez et al., 2020). Study 1 examined what children might learn about death from children’s media through a detailed analysis of children’s animated films produced in the United States in order to characterize the frequency and content of death-related information that is presented to children in these films.

Study 2 focused on how parents talk to their children about death both in general terms and in the context of viewing animated films. This research expands on previous accounts of how children learn about death, by considering the intersection of different sources of information, namely cultural products and parent-child conversations. Study 2 also examined how parental attitudes and sociodemographic factors relate to parent-child conversations about death. While previous studies have suggested that parent-child conversations about death are relatively common (Renaud et al., 2015) and that parents could use animated films to talk to their children about death (Tenzek & Nickels, 2017), to our knowledge, no research has explicitly examined whether parents actually use films as a starting point to foster death-related conversations, or what factors make some parents more likely to use films to talk to their children about death.

Study 1

We analyzed 50 top-grossing children’s animated films from the past five decades to examine the prevalence of death scenes. Because previous research examining death in children’s animated films has focused only on films that contain death (Cox et al., 2005; Tenzek & Nickels, 2017), it is not possible to determine whether death is typically present in animated films or if there are only a small number of animated films that contain deaths. In order to understand how often death is present in these films, we did not restrict our analysis to only films that contained a death. We also used research on children’s conceptual development to perform a more in-depth analysis on how death is portrayed in animated films. Specifically, we explored whether the movies contained information related to the sub-concepts of death (i.e., finality, universality, non-functionality, and causality). We also examined whether these deaths were presented from a strictly biological perspective, included spiritual aspects of death (e.g., non-corporeal continuity), or involved misconceptions (e.g., death as sleep or reversible).

Method

Film Selection

Four criteria were used to select films:

Films had to be released between 1970 and 2016. Films produced before the 1970s were not included due to the relatively small number of animated films produced in the United States prior to this time (see point 2 below). This analysis was conducted in the summer of 2017, therefore we only included films that were released before this year.

Films had to be produced at least partially in the United States. As cultural products, films might reflect values of the culture they were created in. Because we were interested in the cultural context of the United States, we only included films produced in the United States.

Films had to have a rating of G or PG. Because we do not have clear information on what the target age was for each film, we used ratings given to the films by the Motion Picture Association (Dow, 2009). A film with a G rating suggests it is for a general audience, and a film with a PG rating suggests some parental supervision is suggested. Films with ratings higher than PG are considered inappropriate for children under the age of 13 to watch alone.

The film had to be one of the top 10 highest-grossing films in the U.S. based on box-office receipts (boxofficemojo.com) during the decade it was released. We focused on top-grossing films because of their popularity, making them more likely to have been viewed by parents and children.

There were 50 full-length children’s animated films that met these criteria. However, we excluded the 1977 film Wizards. Although this film was rated PG, we felt that it was inappropriate for children due to its vulgar language, excessive violence, and the use of real film clips from Nazi Germany. Therefore, our content analysis included 49 of the 50 films. See Table 1 for the list of films.

Table 1.

List of Animated Films Analyzed in Study 1

| Name of the Film | Year | Number of children in Phase 1 |

Number of children in Phase 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Finding Dory | 2016 | 192 | 189 |

| The Secret Life of Pets | 2016 | 149 | 159 |

| Zootopia | 2016 | 160 | 160 |

| Sing | 2016 | 102 | 115 |

| Minions | 2015 | 163 | 166 |

| Inside Out | 2015 | 126 | 125 |

| Monsters University | 2013 | 120 | 134 |

| Frozen | 2013 | 194 | 193 |

| Despicable Me 2 | 2013 | 146 | 159 |

| Toy Story 3 | 2010 | 152 | 139 |

| Up | 2009 | 121 | 131 |

| WALL-E | 2008 | 122 | 114 |

| Kung Fu Panda | 2008 | 118 | 128 |

| Shrek the Third | 2007 | 95 | 97 |

| Cars | 2006 | 147 | 149 |

| Shrek 2 | 2004 | 108 | 116 |

| The Incredibles | 2004 | 112 | 132 |

| Finding Nemo | 2003 | 188 | 186 |

| Monsters, Inc. | 2001 | 146 | 149 |

| Shrek | 2001 | 138 | 145 |

| Toy Story 2 | 1999 | 148 | 154 |

| Tarzan | 1999 | 58 | 60 |

| A Bug's Life | 1998 | 97 | 98 |

| Mulan | 1998 | 86 | 94 |

| The Prince of Egypt | 1998 | 21 | 30 |

| Pocahontas | 1995 | 76 | 92 |

| Toy Story | 1995 | 158 | 159 |

| The Lion King | 1994 | 173 | 170 |

| Aladdin | 1992 | 120 | 130 |

| Beauty and the Beast | 1991 | 125 | 133 |

| The Little Mermaid | 1989 | 130 | 133 |

| All Dogs Go to Heaven | 1989 | 65 | 66 |

| The Land Before Time | 1988 | 82 | 88 |

| Oliver & Company | 1988 | 22 | 24 |

| An American Tail | 1986 | 42 | 35 |

| The Great Mouse Detective | 1986 | 22 | 18 |

| The Care Bears Movie | 1985 | 35 | 31 |

| The Black Cauldron | 1985 | 10 | 10 |

| The Secret of NIMH | 1982 | 23 | 22 |

| The Fox and the Hound | 1981 | 69 | 52 |

| Watership Down | 1978 | 8 | 8 |

| The Lord of the Rings | 1978 | 11 | 18 |

| The Rescuers | 1977 | 24 | 38 |

| Oliver Twist | 1974 | 8 | 9 |

| Treasure Island | 1973 | 5 | 14 |

| Robin Hood | 1973 | 41 | 41 |

| Charlotte's Web | 1973 | 91 | 100 |

| Snoopy, Come Home | 1972 | 21 | 28 |

| The Aristocats | 1970 | 56 | 45 |

Note. The table also shows how many children from Study 2 have seen each film (based on their parent’s report).

Coding Process

Coding categories were developed based on past content analyses of children’s media (Cox et al., 2005; Tenzek & Nickels, 2017) and research investigating children’s understanding of death (Rosengren et al., 2014; Speece & Brent, 1984). We coded films at two levels of analysis. First, we coded specific characteristics of each movie (e.g., was there at least one death, presence of magic, personification, and spirits). Second, we coded characteristics of each death portrayal including the character status (i.e., protagonist, antagonist, or minor character) and how well the film represented the biological sub-concepts of death. In terms of sub-concepts, we coded the cause of death, whether the death was final, and whether psychological and physical functions stopped after the death. The sub-concept of universality was coded at the movie-level by examining whether there were statements within the film that suggested that not all living things must die (a violation of universality). See Tables 2 and 3 for the full coding scheme.

Table 2.

Codes Used to Analyze Movies

| Code | Explanation | % agreement |

Kappa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of death | There was a death depicted or implied in the film. | 89% | 0.80 |

| Death as a central theme | Whether the death of any character contributes significantly to the plot of the film (e.g., if a character’s death sets the basis for the movie). This death could occur at any point in the film. | 87% | 0.77 |

| Magical context | Whether magic is present in the film. | 100% | 1.00 |

| Personification | At any point during the movie where human characteristics were attributed to non-human characters such as cars, toys, animals, creatures, and monsters. | 100% | 1.00 |

| Non-Universality | The film conveyed the idea that not every living thing has to die. For example, it was explicitly mentioned that one character cannot die. | 89% | 0 |

| Pretend death | At any point during the movie, a character acted as if they were dead, but they were not. | 78% | 0 |

| Sleep death* | At any point during the movie, a dead character was portrayed as sleeping. | 100% | 1.00 |

| Death as a memory | At any point during the film, characters remembered and talked about a death that happened in their past, without using flashbacks. | 100% | 1.00 |

| Non-corporeal continuity | Spirits were present at any point during the film. | 100% | 1.00 |

| Group death | At any point during the movie, two or more characters died at the same time. | 78% | .52 |

Note. Codes marked with an * represent themes used in prior studies (Cox et al., 2005).

Table 3.

Codes Used to Analyze Deaths in Films

| Code | Explanation | % agreement |

Kappa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Character status* | The role of the deceased character in the film: protagonist, antagonist, or minor character. A protagonist is a character who is seen as the hero/heroine of the movie or the “good guy” and is normally the main character whom the story revolves around. An antagonist is a character who is seen as the villain or “bad guy” and is generally the enemy of the protagonist. A minor character is a character that does not have as much screen time as the protagonist or antagonist. | 87% | 0.86 |

| Depiction of death* | Whether a death was portrayed in an implicit or explicit manner. An explicit death is when it is clear that a character is dead because the viewer can see how the individual died or their dead body is present in the scene. An implicit death is when the viewer has to assume that a character is dead because they are no longer seen in the movie after a certain point. | 73% | 0.61 |

| Character gender | The gender of the deceased character: man, woman, or gender was unidentified. | 73% | 0.61 |

| Physical form of the deceased | Whether the deceased character was human or non-human. | 80% | 0.82 |

| Age of the deceased | The age of a deceased character: child, adult, or age was unidentified. | 73% | 0.71 |

| Emotional reaction* | The reactions of characters when a death occurs: negative emotion, positive emotion, mixed emotion, or lack of emotional reaction. Negative emotion is when a character(s) reacts to a death by showing sadness, anger, frustration, or by crying. Positive emotion is when a character(s) reacts to a death by showing relief or happiness. Mixed emotion is when some characters are angry, while others are happy, when a death occurs. Lacking emotion is when characters act as though the death is not important. | 87% | 0.75 |

| Biological functionality | When a character dies, their biological functions remain intact (e.g., they can still talk, eat, move around, etc.). | 87% | 0.88 |

| Psychological functionality | When a character dies, their psychological functions remain intact (e.g., they can still think, feel, dream, etc.). | 87% | 0.88 |

| Finality | The deceased character does not come back to life later in the film. | 87% | 0.88 |

| Cause of death | Was the death accidental, purposeful, or natural. An accidental death is when a character’s death occurs unintentionally (e.g., a death as a result of an unplanned event). A purposeful death is when a character dies because of another character’s intent to kill or harm them. A natural death is when a character dies of natural causes (e.g., as a result of an illness or an internal malfunction of the body). | 80% | 0.76 |

| Magical death | Was magic is involved in the character’s death. | 93% | 1.00 |

Note. Codes marked with an * represent themes used in prior studies (Cox et al., 2005).

Intercoder Reliability

Five coders rated the films. All coders were trained using three animated movies (i.e., Anastasia, Lilo & Stitch, and Moana) from different decades (i.e., 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s). These practice films were not included in the final 49 films as they did not meet our inclusion criteria of being among the top-grossing films (Moana would later be one of the top-grossing films, but because it was released in late 2016, a portion of its sales were made in 2017). A primary coder (first author) analyzed 25 films and the remaining films were assigned to the other four coders, with each coder analyzing eight or nine movies. Each of the coders overlapped with the primary coder on two different films included in the primary coder’s original 25 films. All five coders coded their assigned films independently of each other as is standard practice for content analyses (Lacy et al., 2015).

Intercoder reliability was deemed acceptable as the percent agreement between each of the coders and the main coder was above 80% (average percent agreement = 88%, and the agreement for every category was above 70%). Individual reliabilities (average percent agreement and kappas between the main coder and the other coders) are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Overall, reliability estimates for individual categories were deemed acceptable. Three categories (i.e., non-universality, pretend death, and group death) did not have good kappas, however this was due to the low frequency of these categories, as the percent agreements were high and there was a maximum of two disagreements in these categories. Prevalence and bias adjusted kappas suggest there was good reliability (non-universality = 0.85, pretend death = 0.80, group death = 0.70). All disagreements were resolved through discussion between all the coders and the second and third authors. This ensured that there was consensus with the entire research team about the codes used in the analysis.

Results

We found that 37 of the 49 films (76%) contained death scenes, with 118 death scenes in total and an average of three death scenes per film (SD = 3.2). Twenty-eight of these 37 films had a death that was central to the plot (e.g., Mufasa’s death in The Lion King). Minor characters died most frequently (n = 88), followed by antagonists (n = 24), and protagonists (n = 7). We found that, similarly to previous studies, about a third of the deaths (n = 41) were implicit suggesting it was not clear whether the character had actually died. The number of implicit deaths did not differ by character type, χ2 (2, N = 118) = 3.11, p = .211.

Biological Depictions of Death

Of the 37 films that contained a death, 30 always depicted finality accurately, 32 always depicted physical non-functionality accurately, and 31 always depicted psychological non-functionality accurately. Additionally, only four of these films made any suggestion that death was not universal. Of the 118 death scenes, 110 portrayed finality accurately, 112 portrayed physical non-functionality accurately, and 111 portrayed psychological non-functionality accurately. Next, we explored how characteristics of the movies influenced the likelihood that a death was coded as biologically accurate. For this, we ran a generalized linear mixed-effects model, using a binomial function. We predicted the likelihood that a death was biologically accurate from the film release year, the presence of magic or personification in the movie, and whether it was mentioned that not all living things die. We also included a by-movie random intercept. We found that movies that had magic or personification were less likely to portray death in a biologically accurate manner; χ2 (2, N = 118) = 4.38, p = .036, and χ2 (2, N = 118) = 4.12, p = .042, respectively. Fourteen films portrayed some form of magic and 45 films had personification; in fact, only two films in our sample did not include either element.

Non-Biological Views of Death

We also analyzed whether any of the films portrayed misconceptions about the four sub-concepts of death. Only four films expressed the idea that not all living things die (i.e., universality), and seven films had at least one scene that portrayed death in a biologically inaccurate manner (i.e., portrayed violations of finality or non-functionality). Two films equated death with sleep, treating death as something one can wake up from (violating finality). Additionally, we explored whether death was expressed in terms of non-corporeal continuity. Eight films portrayed deceased individuals in a spiritual form, while six films contained the notion of continuity after death, but in the memories of individuals who were still living.

Discussion

In Study 1, we found that death was portrayed quite frequently in the children’s animated films that we analyzed (76%), and death was generally portrayed in a biologically accurate manner. That is, death was treated as universal and final, and led to the cessation of psychological and biological processes. A large number of the death scenes depicted the concepts of finality and non-functionality in a biologically accurate manner. Few films treated death as not universal, and few films contained misconceptions, such as treating death as sleep. Although the majority of films included death scenes, many of them were conveyed implicitly, potentially leaving children unsure about whether the character actually died. We also replicated a previous finding that most of the deaths occurred to minor characters (Cox et al., 2005; Tenzek & Nickels, 2017). In contrast to children’s books, children’s animated films often display deaths.

We should acknowledge that although most of the death scenes we observed in these films involved minor characters, this does not mean that children were not paying attention to them. We determined character status based on how much screen time the character had. Therefore, the category of minor character is fairly heterogeneous. Minor characters could be companions or named characters that do not play a large role in the plot, unnamed characters in the background, or the parents of the protagonists who might play a big role in the plot but only in the beginning of the film. An analysis of 19 of the films (including 39 minor character deaths), showed that 7 parents died. These different types of minor characters might elicit different responses from children and parents. Parents might also be reluctant to discuss the death of the protagonists’ parents, while both children and parents might ignore the death of an unnamed character that occurred in the background. To the extent that parents use these films to have conversations about death with their children, future research could investigate whether these different characters elicit different reactions or conversations.

As mentioned in the introduction, children often have difficulties learning from media. Learning about death from animated films may be difficult as many of these films contain fantastical elements, such as magic, that could signal to children that the content of the film should not be generalized to real life. The likelihood that children learn from watching media is also increased if parents scaffold their understanding (Kirkorian et al., 2008; Sheehan et al., 2019). Therefore, it is important to not only consider animated films, but rather how animated films might create a socialization context for parents to talk to their children about death.

Examining the intersection of films and parent-child conversations is critical in order to interpret the findings of Study 1. For example, the finding that the majority of deaths in films occurred to minor characters could be a good thing as children might not feel emotionally connected to them, thus making it easier for parents to discuss these deaths. Conversely, parents and children might not attend to the death of minor characters given their relatively small role in the plot, and thus these deaths might not foster discussion. Additionally, a film displaying misconceptions about death (e.g., death as a deep sleep or death as reversible) might not be worrisome if parents correct these misconceptions.

Given the importance of parents in determining how much children will learn from watching deaths in animated films, it is also necessary to examine factors that make it more likely that parents engage in conversations with their children. Prior literature suggests that parents are more likely to engage in conversations if they find the topic important and are motivated (Perry et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2020). Thus, one important factor might be how much parents care about how death is represented in animated films. Parents who believe representing death accurately is important might be more likely to engage in conversations with their children or might be more likely to correct misconceptions when they appear. Additionally, factors like the age of the child and parental socioeconomic status might also influence how likely parents are to engage in these discussions (Rosengren et al., 2014; Wiley et al., 1998).

Study 2

Study 2 (n = 433) reports the results of an online survey examining parental attitudes toward death in animated films and how parents and children talk about deaths in these films. First, we examined whether children actually watch the films we coded in our content analysis. Given that we selected the top-grossing films of each decade, we expected that many children had seen the films we coded. We also focused on whether parents allow children to watch animated films that contain death, and whether they co-view these films with their children. This data provides us with information on whether there might be opportunities for parent-child conversations about the deaths during co-viewing. We also examined parental attitudes toward the representations of death in animated films and their willingness to use these films to talk to their children about death. Finally, we examined children’s questions and parental responses about death in animated films and death more generally. By doing so, this allows us to examine differences and commonalities in children’s questions.

Study 2 was designed to examine the extent to which parents of young children (3- to 10-year-olds) use animated films to spark conversations about death. We chose this age range for three reasons. First, this is the age range where children’s understanding of death undergoes significant development (Rosengren et al., 2014). Second, this is the target age range for a majority of children’s animated films. Third, during this age range, children might be more likely to watch films along with their parents.

We had parents complete an online questionnaire that asked whether they and their children had watched any of the films that we analyzed in Study 1. We also asked whether animated films stimulated death-related conversations. If these conversations had occurred, we then asked parents to provide details about them including the questions that were asked and the responses that were given.

Study 2 was conducted in two phases. During the first phase, we did not ask about parents’ gender for the first half of the participants due to an experimenter error. For the second phase of data collection, we added the gender question. Because we did not observe effects of parental gender in phase 2, we report the two phases together. A separate write up of the two phases along with the data files and codebooks for all studies can be found here: https://osf.io/e8xgn/?view_only=8064f75b5fea45a9ab370d096b0ec312.

Method

Participants

We recruited 250 parents of children 3- to 10-years of age in phase 1 and 253 parents in phase 2 through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. This sample size is larger than previous studies that sampled between 100 and 150 parents. We excluded 32 respondents because they failed an attention check, and six parents because they did not have a child within the desired age range. Thirty-two parents completed the study in both phase 1 and 2, so we removed their second response. Our final sample included 433 parents (336 White, 29 Black/African American, 19 Hispanic/Latinx, 21 Asian/Pacific Islander, 3 Native American/American Indian, 1 Arab, and 23 Biracial) and parents/caregivers ranged in ages from 21 to 62 years old (M = 35.03, SD = 7.04). In phase 2, the parents were primarily mothers (63.2%). Parents reported having 204 daughters and 224 sons (five parents did not report the gender for their child). The average age of the children was 5.94 years (SD = 2.31 years). On an 11-point scale, parental subjective socioeconomic status (SES; Goodman et al., 2001) ranged from 2 to 10 (M = 5.49, SD = 1.64). On average, participants took 7.5 minutes to complete the questionnaire and received one dollar for their participation.

Two hundred and twelve of the parents (49.0%) considered themselves religious. Nine parents (2.1%) identified as spiritual, but not religious. However, when asked which religion they practiced, 256 parents (59.1%) identified a religion. One hundred and fifty-one (34.9%) parents identified as Protestants, 80 (18.5%) as Catholics, 4 (0.9%) as Muslim, 4 (0.9%) as Jewish, 4 (0.9%) as Mormon, 3 (0.7%) as Baptist, 3 (0.7%) as non-denominational Christian, 2 (0.5%) as Wiccan, 1 (0.2%) as Buddhist, 1 (0.2%) as Hindu, 1 (0.2%) as Pagan, 1 (0.2%) as Deist, and 1 (0.2%) as Orthodox Christian. Parents also completed sub-scale 3 of the Duke University Religion Index, which measures the extent to which an individual’s religion permeates into their daily lives (Koenig & Büssing, 2010). We had parents spanning the full range of possible responses (M = 2.85, SD = 1.53).

Materials and Procedures

The survey was constructed using Qualtrics® (Provo, UT), an online survey software, with a link to the survey posted to Mechanical Turk. Before they could begin the questionnaire, parents completed screener questions designed to exclude anyone living outside of the United States or anyone who did not have at least one child between the ages of 3 and 10. Participants completed an online consent form after the screener. We included one attention check in the questionnaire and participants were dropped if they failed it.

Parents were asked to provide demographic information about their age, race/ethnicity, education level, and religious beliefs, as well as the age and gender of their children. If they had multiple children, we asked them to focus on their youngest child between the ages of 3 and 10. This is because most of the research on parent-child conversations about death has focused on the lower end of this age range (e.g., Gutiérrez et al., 2020; Renaud et al., 2015; Rosengren et al., 2014). We asked parents to report whether they had ever engaged in death-related conversations with their children and if so, how many times these conversations occurred. We also asked them to provide a list of questions their children had asked them about death and how they responded. Parents could report, at most, three questions with their respective answers. Those who indicated that they have talked to their children about death were then asked whether these questions were sparked by the recent death of a loved one.

In the next section, we asked parents to report whether they allowed their children to watch animated films that contained death scenes. Those who did were then asked whether they watched these movies with their children and how often they watched them together. Then, we asked parents to report whether their children had seen any of the 50 films included in Study 1 (even though one film was excluded from our coding, we still included it when asking parents which films their children had watched). Parents were then asked whether they believed that animated films portrayed death in an accurate manner, using a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not accurately at all) to 5 (extremely accurately). Following this, we asked participants to report whether their children had ever asked them questions about deaths portrayed in animated films. Then, parents had the opportunity to report up to three of the questions their child asked regarding deaths portrayed in the films and how they responded.

We also asked whether participants talked to their children about misconceptions regarding death present in these films (i.e., “Do you talk to your children about the misconceptions that may be presented in these death scenes?”), if they ever considered using animated films to talk to their children about death (i.e., “Have you ever considered using animated films to talk to your children about death?”), and the extent to which they cared about how death is portrayed in animated films (i.e., “How much do you care about how death is portrayed in animated films?”) on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (a great deal) to 5 (not at all). The purpose of asking parents how much they care about how death is portrayed was to measure individual differences on how interested parents were about representations of death, as parents who care a great deal might be more likely to discuss these representations with their children compared to parents who do not care.

Coding Process

To analyze the death-related conversations between parents and their children, we started with a coding scheme developed by Gutiérrez et al. (2020). These codes included: general information about death, universality, finality, non-functionality, causality, emotion, non-corporeal continuity, religion, death rituals, and consequences of the death. A summary of all the codes can be seen in Table 4. However, through our analysis, it became clear that there were additional topics discussed, requiring us to add new codes. Two coders read through each child’s questions and their parent’s responses in order to identify recurring themes not captured by the codes used by Gutiérrez et al. (2020). This process was completed separately for each question and answer. We identified three additional themes: clarifying the scenes, the intentions of characters/reason for death, and reference to the scene being in a movie (see Table 5).

Table 4.

Description of Codes Used to Describe Questions and Answers about Death in General

| Code | Description | Sample question |

Sample answer | Questions | Answers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General information | General details about a person’s death. | Is he dead? | Yes, he is no longer with us. | 106 | 59 |

| Universality | Mentioning that everyone dies or that death is a natural part of life. | Will I die? | Yes, someday, a long time from now, after you've lived a wonderful, long life | 60 | 84 |

| Finality | Mentioning that when a person dies, they cannot come back to life. | Do they come back? | No, it's a permanent thing but it's best for them. | 47 | 20 |

| Non-functionality | Reference to functions, biological or psychological, that a person can no longer perform because they are dead. | Can you hear anything when you die? | No you can not. Your body stops working and all your senses and feelings go away. | 15 | 23 |

| Causality | Mentioning the cause of a person’s death. | Do people die if nothing kills them? | Yes, if they get very old. | 205 | 68 |

| Noncorporeal continuity | Any mention that the person continues to exist after they die. | Where did Grandma go? | Grandma turned into the energy that creates things like the oceans and flowers. | 133 | 110 |

| Religion | Any mention of God, Heaven, or other religious references such as angels. | Where is heaven? | Heaven is far away where heavenly father lives. | 73 | 226 |

| Death rituals | Any reference to a ritual related to death. | Why do we put them in the ground? | That is where we put them to remember them and go talk to them whenever. | 11 | 24 |

| Emotions* | Any reference to the emotions experienced after a person dies. | Will everyone be sad when they die? | Yes very sad. | 34 | 43 |

| Consequences | Any mention of what happens to a person’s material possessions or relationships after they die. | What would happen to their toys if I died? | They would be able to take their toys with them. | 4 | 2 |

Note. Under questions and answers are the frequency of occurrence of each coding category. Categories marked with an * are categories in which the example answer was not in response to the example question.

Table 5.

Description of Codes Used for Questions and Answers about Deaths in Animated Films

| Code | Description | Sample question |

Sample answer | Questions | Answers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clarification on scene | Mention that a movie scene was not clear. | What happened to the dog? | He passed away. | 100 | 52 |

| Intentions of characters | Mention of why a character performed an action. | Why did Scar kill Mufasa? | He wanted to be king so badly that he killed his brother. | 18 | 23 |

| Movie | Any reference to a situation occurring because it is a movie. | Why did so and so have to die? | I just tell her that that's the way the movie was written and it's not real. | 20 | 37 |

| Universality* | Mentioning that everyone dies or that death is a natural part of life. | Am I going to die? | We all are going to die; we just don't know when? | 6 | 17 |

| Finality | Mentioning that when a person dies, they cannot come back to life. | Will they, come back | They won't come back | 22 | 8 |

| Non-functionality* | Reference to functions, biological or psychological, that a person can no longer perform because they are dead. | Why they can't live more | They can't open their eyes anymore. | 2 | 3 |

| Causality* | Mentioning the cause of a person’s death. | Why did Mufasa die. | He died when the animals in the stampede ran over him. | 70 | 26 |

| Non-corporeal continuity | Any mention that the person continues to exist after they die. | Where did that character go after they died. | There spirit went to another place & left there body behind. | 11 | 12 |

| Religion* | Any mention of God, Heaven, or other religious references such as angels. | Do dogs go to heaven | We join God if you believe in Jesus | 13 | 42 |

| Death rituals* | Any reference to a ritual related to death. | Are they going to be buried like Grandpa? | He was buried in the ground. | 2 | 1 |

| Consequences* | Any mention of what happens to a character’s material possessions or relationships after they die. | How can Simba survive without his dad? | Now he has to live without her. | 4 | 1 |

| Emotions | Any reference to the emotions experienced after a person dies. | Why is he/she so sad? | They are sad because the person died. | 38 | 38 |

Note. Under questions and answers are the frequency of occurrence of each. Categories marked with an * are categories in which the example answer was not in response to the example question.

The main coder (first author of the paper) coded all responses. Then, a second coder (second author) coded a portion of the responses to assess reliability. For the questions and answers about death in general, the second coder coded 25% of the responses. For the questions and answers about death in movies, the second coder coded 50% of the responses. The percentage of overlap was higher given that we identified additional themes and that this was the first study to examine questions about death in movies. The percent agreement between coders was above 80% for all codes. For phase 1, Cohen’s Kappa was above 0.70 and thus considered acceptable; 0.83 for questions about death, 0.75 for answers about death, 0.75 for questions about film deaths, and 0.78 for answers about film deaths. For phase 2, Cohen’s Kappa was also above 0.70; 0.76 for questions about death, 0.76 for answers about death, 0.77 for questions about film deaths, and 0.73 for answers about film deaths. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Results

We first discuss the extent to which children actually viewed the films that we analyzed in Study 1. Then, we present data on whether parents allow children to watch animated films that contain death, and if so, whether they watch the films with their children. Then, we explore details surrounding parental attitudes toward death in animated films. Finally, we present children’s questions about death in general and in animated films and their parents’ responses.

Children's Viewing of Animated Films

We asked parents whether their children had seen the movies coded in Study 1 and found that, on average, children had seen 20.38 (SD = 9.7) of the 50 films (even though one film was eliminated from the content analysis, we still included it in this parental survey). However, there was great variability, with one child having seen only one of the films and another child having seen 45 of the 50 films. Children’s age was positively related to parents reporting their children having seen more films, F(1, 416) = 24.59, p < .001, η2 = .056. The child’s gender, the parent’s SES, and parental education were not related to the number of movies watched, p’s > .10. In addition to the wide variability in the number of films children had seen, there was considerable variation in which films children watched, with more recent films being watched by more children, F(1, 47) = 69.16, p < .001, η2 = .595. However, all films were watched by at least 16 children in our sample, and films, on average, were watched by about 44% of children (SD = 26%) (See Table 1).

Do Parents and Children Watch Animated Films that Contain Death?

Thirty-eight parents in our sample (8.8%) said that they do not allow their children to watch animated films that contain death scenes. We examined whether parents allowing their children to watch movies that contain death scenes depended on child’s age (as a continuous variable), child’s gender, subjective SES, whether the parent is religious, or the parent’s age. None of these factors were significantly related to whether parents allowed their children to view these films, all p’s > .100. Of the 395 parents who allow their children to watch animated films containing death scenes, 265 (67%) responded that they always watched the films with their children and 123 parents (31%) said that they sometimes watched animated films that contain death with their children. Seven parents (2%) who allowed their children to watch these films said that they seldom or never watch these movies together. Overall, these results suggest that parents do generally co-view these films with their children, creating potential opportunities to discuss questions about death that may arise from watching these films.

Parental Attitudes towards Death in Animated Films

We explored parents’ attitudes towards death in animated films and whether their attitudes depended on demographic factors such as child’s age (as a continuous variable), child’s gender, parent’s age, religiosity, and subjective SES. About half of the parents (n = 238, 55%) said they cared little or did not care at all about how death is portrayed in children’s animated films. Religious parents cared more about how death is portrayed in films, when controlling for demographic factors, t(406) = 2.31, p = .022. The majority of parents (n = 365, 84%) responded that animated films portrayed death at least somewhat accurately. This aligns with Study 1 which shows that animated films tend to depict death in an accurate manner.

However, Study 1 also showed that animated films sometimes contain misconceptions about death. We examined whether parents ever talk to their children about these misconceptions. We found that 147 parents (34%) talked to their children about misconceptions present in the death scenes of animated films (at least sometimes). However, 283 parents (65%) said they do not correct these misconceptions. There was a positive relation between children’s age and parents’ likelihood of talking about misconceptions, when controlling for demographic factors and how much parents cared about how death is portrayed, t(406) = 2.13, p = .033.

Additionally, religious parents and parents who care more about how death is depicted in films were more likely to talk about misconceptions, when controlling for demographic factors and how much parents cared about how death is portrayed, t(406) = 2.57, p = .011, and t(406) = 4.74, p < .001 respectively. About a quarter of parents (105, 24%) had considered using animated films to talk to their children about death. Parents who cared more about how death is portrayed in animated films and parents who discuss misconceptions with their children were more likely to consider using animated films to talk about death with their children, when controlling for demographic factors, OR = 1.77, χ2(N = 412) = 20.94, p < .001 and OR = 2.30, χ2(N = 412) = 10.52, p = .001, respectively.

Conversations about Death

Death in general.

The majority of parents (316, 73%) reported having conversations with their children about death in general. However, the frequency of these conversations varied. Ninety-four (22%) parents said they had one conversation, 177 (41%) said they had two to three conversations, and 51 (12%) said they had four or more death-related conversations with their children. Additionally, 299 parents (69%) reported that their children had asked them questions about death. One hundred and seventy (39%) parents reported that the questions were sparked by a death in the family. Two hundred and ninety-five parents reported at least one of the questions that their child had asked them about deaths in animated films.

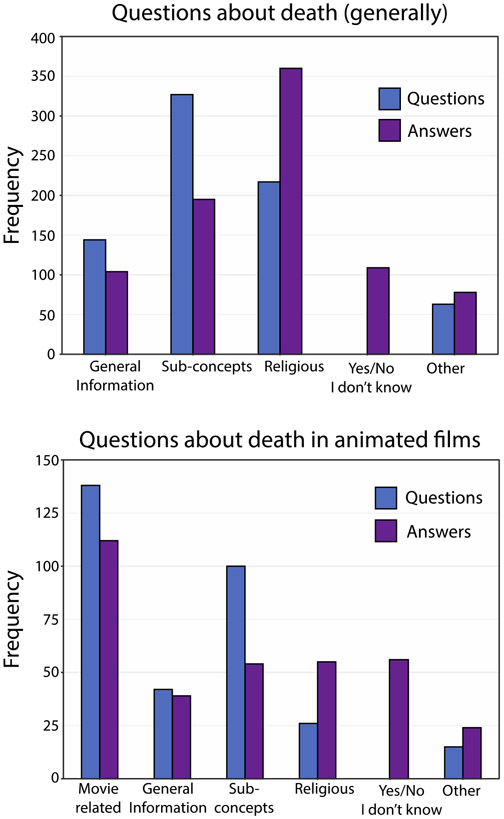

Overall, the pattern of children’s questions and parents’ answers resembles prior research (Gutiérrez et al., 2020; Rosengren et al., 2014). As shown in Figure 1, children predominantly asked questions about the sub-concepts of death, particularly causality (n = 205). Parental responses, on the other hand, primarily focused on religious (n = 227) or afterlife-related beliefs (n = 110). For example, a 3-year-old girl asked their mother “what happens when we die?” and their parent answered, “Some people believe we go to another place that is better, where we never experience any pain again. While others say we come back as another person or an animal.” However, many parents still conveyed information about the sub-concepts of death: universality (n = 84), finality (n = 20), biological/psychological non-functionality (n = 23), and causality (n = 68). For example, a 10-year-old boy asked, “Will I die, too?” and their mother responded, “Everyone will die, but usually people die when they are very old.”

Figure 1. Children’s Questions and Parents’ Answers about Death.

Frequency of themes found in children’s questions and parents’ answers about death in general (top panel) and death in animated films (bottom panel) in Study 2. For simplicity, we combined related categories. Movie-related categories include clarifying the scene, characters’ intentions, and references to the movie. General information includes general information about death, emotion, and consequences. Sub-concepts include universality, finality, non-functionality, and causality. Religious includes religion, non-corporeal continuity, and death rituals.

We also saw that parents provided both biological and spiritual information. One hundred and one parents (34.1%) provided details about the sub-concepts and religious information at least once across the three questions. Eighteen parents answered questions with a combination of biological and spiritual information. In some of these answers, parents provided information about one of the biological sub-concepts and then added information about afterlife beliefs. For example, the parent of a 3-year-old girl wrote “… they are all feeling no pain now they are in heaven with god.” This answer communicates information about non-functionality (dead people do not feel pain) but adds information about the continued existence of the soul in Heaven.

Other combinations used spiritual information to comfort the child. For example, the parent of a 3-year-old boy wrote “it is a part of life that is natural, just like the leaves fall off of the trees, and our flowers die. There is nothing to be scared of as a believer of Christ.” In this case, the religious information does not communicate an afterlife belief but reassures the child that they should not feel scared as they believe in Christ. This suggests that parents communicate both biological and spiritual models of death to their children, either in the same answer or over time.

We examined whether the questions children asked varied in a systematic way. We fit a logistic regression predicting whether children ever asked about any of the topics we coded and included child’s age (as a continuous variable) and gender, and parental subjective SES as predictors. We found that a year increase in children’s age was related to an increased likelihood that children asked about causality, OR = 1.13, χ2(N = 291) = 5.74, p = .017. No other effects were significant.

We also examined whether parents’ answers varied in a systematic way. We fit a logistic regression predicting whether parents ever mentioned any of the topics we coded in their answers and included child’s age (as a continuous variable) and gender, whether parents are religious, and parental subjective SES as predictors. Religious parents were less likely to provide general information, OR = 0.47, χ2(N = 283) = 5.79, p = .016, and more likely to provide religious information, OR = 12.72, χ2(N = 283) = 90.66, p < .001. Parents with higher subjective SES were less likely to provide information about non-functionality, OR = 0.63, χ2(N = 283) = 9.79, p = .002. No other effects were significant.

Death in animated films.

About a third of the parents (n = 161, 37%) reported that their children had asked them questions about deaths in animated films. One hundred and fifty parents reported at least one of the questions that their child had asked them about deaths in animated films. The majority of the children’s questions were centered on the content of the movie (see Figure 1). Several questions asked the parents to clarify the events that occurred in the movie (n = 100), asked about the intention of characters (n = 18), or why certain events happened (n = 20). A number of parents answered questions by clarifying the scene (n = 52), discussing the intentions of characters (n = 23), or by stating that the death occurred in a movie to explain details about the death (n = 37).

In some instances, children asked for clarification of the scene, and parents provided an answer related to the story. For example, when a 4-year-old girl asked, “What happened to Mufasa?” their parent answered, “He died when the animals in the stampede ran over him.” However, other times, parents used the fact that the death happened in a movie to not answer the child’s question. For example, when an 8-year-old girl asked, “Did [the character] really die?” their parent answered, “It's a movie.” Although not incorrect, the parent’s answer does not address the child’s question directly. The same parent also reported that their child asked them “Are they coming back to life?” referring to whether the deceased character will come back to life. Rather than discuss with the child that entities do not come back to life after they die or give the child an answer related to the plot of the movie, this parent, once again, dismissed the question by answering “It's a movie.”

When questions or answers did not focus on the movie-specific aspects of the deaths, we found similarities between the conversations about death in films and death more generally. Many non-movie questions were about causality (n = 70), emotions (n = 38), and finality (n = 22). Causality was also the most common topic of children’s questions about death. Non-movie responses focused on religious beliefs (n = 42), emotions (n = 38), and causality (n = 26). Religious beliefs were also the most common topic in parents’ answers about death. For example, the mother of a 10-year-old boy said, “They died and went to pet heaven” when their child asked, “What happened to them?” However, parents still conveyed biologically accurate information. For example, the parent of a 6-year-old boy reported that their child had asked them “why did the character die” to which they answered, “It was sad but it was his time to die”. The child then asked questions not about the death scene but about death more generally, specifically “does it hurt to die” and “will I die”. To this last question the parent answered, “Everyone dies but most people live a long time and I will do everything to keep you safe and healthy”. As shown by this interaction, some children ask about biological aspects of death (causality and universality in the examples above) when discussing death in animated films. And some parents use these questions to provide biologically accurate information, such as “Everyone dies.”

Additionally, 17 parents (11.3% of the parents who reported questions) provided details about the sub-concepts and religious information at least once across the three questions. As in the conversations about death more generally, four of the parents combined spiritual and biological information in the same answer. For example, when a 4-year-old girl asked “Why did his wife die? (Referring to the old man in Up)” their parent answered “We all get old and die. It's not something to be afraid of. It's natural. And it makes people sad to see us go, but we're going home to be with Jesus, so they shouldn't be too sad.” In this example, the parent is using religious information to comfort the child by telling them that they should not be afraid of death because they will be united with Jesus. However, other parents integrated religious information with biological information as when a 4-year-old boy asked their mother “What happened to Simba's dad?” and their mother answered, “He got hurt and wasn't able to get help so he passed away and went to heaven.” In this example, the parent used their child’s request of clarification to make it clear that the character died and used biologically accurate information about the death (that the character got hurt and died because of it) and religious information (that the character is now in heaven).

We fit a logistic regression predicting whether children ever asked about any of the topics we coded and included child’s age (as a continuous variable) and gender, and parental subjective SES as predictors. We found that girls were less likely to ask about universality than boys, OR < 0.001, χ2(N = 148) = 6.05, p = .014. No other effects were significant.

We also fit a logistic regression predicting whether parents ever mentioned any of the codes and included child’s age (as a continuous variable), child’s gender, whether parents were religious, parental subjective SES, how much parents cared about how death is portrayed in animated films, and whether parents talk about misconceptions about death present in films influenced the likelihood of parents providing a particular answer as predictors. We found that the more parents care about how death is portrayed in films, the less likely they were to say that the death is not real because it happened in a movie, OR = 0.58, χ2(N = 141) = 5.00, p = .025, and the more likely they were to talk about non-functionality, OR = 5.54, χ2(N = 141) = 6.20, p = .013. Parents who discussed misconceptions about death with their children were more likely to say that the death is not real because it happened in a movie, OR = 7.35, χ2(N = 141) = 13.22, p < .001, and more likely to talk about the afterlife, OR = 7.80, χ2(N = 141) = 5.16, p = .023. Religious parents were less likely to offer clarifications than non-religious parents, OR = 0.38, χ2(N = 141) = 5.73, p = .017, and more likely to provide a religious answer, OR = 8.57, χ2(N = 141) = 20.59, p < .001. No other effects were significant.

Discussion

In Study 2, we found that many children and their parents had watched the animated films analyzed in Study 1 and that they watched these films together. This suggests that there is a co-viewing opportunity where children might be able to ask their parents about a death that occurs in the film. When initiating conversations, children often asked questions about the sub-concepts of death. In fact, children’s questions about death in animated films (and their parents’ responses) greatly resembled the questions and answers that parents provided about death more generally. This suggests that children’s question-asking about death in animated films can elicit information about death more generally, and parents seem to be responding to these queries in a similar manner to questions about death in other contexts. This is important as some parents reported having considered using animated films to talk to their children about death.

We also found evidence that some parents are reluctant to discuss death in animated films with their children. Many parents (n = 126, 54%) said they did not care about how death was portrayed in children’s films, and many (n = 283, 65%) expressed that they do not attempt to correct misconceptions when they are present. Thus, even if there is an opportunity for parents to use films to talk to their children about death, parents might not take advantage of it. These differences in attitudes seemed to be related to demographic factors such as religiosity and subjective SES.

The idea that parents’ religiosity influences how they talk to their children about death has been supported in the literature (Zajac & Boyatzis, 2020), however, our study is the first to show that parents use religion when discussing death in domains such as animated films. We also found that religious parents cared more about how death is portrayed and in turn were more likely to discuss misconceptions that appeared in films. One possible explanation for this finding is that religious parents might be more interested in having their children watch media that aligns with their own beliefs and when this does not occur, they might be more motivated to discuss with their children these differences and state their religious views (as they were more likely to mention religious content when discussing death in movies).

We also found that parents’ subjective socioeconomic status influenced the content of parent-child conversations. Parents with higher subjective SES were more likely to mention religious information and less likely to talk about non-functionality. Prior research has found differences in how U.S. parents socialize their children based on SES (Miller, 1994; Wiley et al. 1998), however, none of these studies have focused on death. Those studies generally find that parents with low SES are less likely to shield their children from information about topics such as aggression, as a way to prepare them for the reality of their communities. If death is more prevalent in communities with lower SES, then parents in these communities might similarly feel like they need to prepare their children and talk to them about death rather than shield them. Parents from higher SES communities might want to shield their children as they might think that their children are unlikely to experience the death of a loved one. However, more work is needed on how community-level factors might influence parental attitudes towards death.

These differences in attitudes might also be important predictors of how parents talk to their children about deaths in animated films. Parents who cared more about how death is portrayed tended to discuss misconceptions present in films, tended to provide more non-functionality information, and tended to not just say that the death is not real because it happened in a movie. This means that parents who thought representations of death in films are important were more likely to correct any misconceptions present in films, use films to convey biologically accurate information about death, and take children’s questions about death in films seriously (rather than discounting them because “it is just a movie”). This suggests that conveying to parents that death scenes in films are a useful tool for talking to their children about death might lead them to engage in more conversations or make the most out of the questions that children are already asking with respect to deaths in films.

Additionally, parents who discussed misconceptions tended to talk more about afterlife beliefs and say that the death was just in the movie. Again, this suggests that parents who take the time to explain how the films may or may not be accurate also tend to engage with children’s questions about death in films. It is interesting that parents who discuss misconceptions also tended to mention afterlife beliefs more. It is possible that some of the parents tended to explain misconceptions present in films in terms of the afterlife, or that they used afterlife beliefs to comfort their children when explaining misconceptions. Regardless of the reason, our data show that parental attitudes towards death in animated films might be important predictors not only of whether parents talk about death in animated films, but also of what topics they discuss when they do engage in these conversations.

We also found that many parents responded to their children’s questions about death by making reference to the death being in a movie. Although this information is not incorrect, these answers avoid the child's question about death, by dismissing it as not relevant for the real world. For example, when an 8-year-old girl asked her parent “why did [the character] have to die?”, the parent responded, “It’s a movie”, not providing any resolution to their daughter’s question. More research is needed in order to determine when parents provide these answers. The example above shows how parents might use the fact that the death occurred in a movie to not have to discuss information about death. However, parents could also use it to explain why a misconception is present. Parents can say that a character came back to life because it is a movie. This might be the reason why parents who discussed misconceptions in films were more likely to provide movie-related answers to their children.

We also found that some parents reported that they did not allow their children to watch animated films that contain death scenes. This suggests that some parents explicitly shield their children from death-related information by prohibiting them from viewing media that contains death. However, this shielding might change with age, as parents were more likely to discuss misconceptions present in films with older children.

General Discussion

Depictions of Death in Children’s Media

Collectively, our two studies have shown that death is prevalent in many children’s animated films, and that many children co-view these films with their parents. Additionally, most of the deaths that we coded in Study 1 were portrayed in a biologically accurate manner. This fact does not go unnoticed by parents, as many of the parents in Study 2 said that they thought animated films portrayed death somewhat accurately. The presence of biologically accurate information might be useful for parents when talking to their children about death, as the majority of children’s death-related questions were about the biological sub-concepts. These findings suggest that films might serve as a vehicle for stimulating conversations about death.

We also found that some films included information about non-corporeal continuity, portraying deceased individuals as continuing to exist as spirits or in the memories of those who knew them. Given that parents often responded to children’s questions about death with religious/spiritual information, the presence of this information might be useful for parents to initiate conversations about death from a religious or spiritual perspective. These results suggest that animated films might be a good source of death-related information for children as they contain both biological and non-biological information that both children and parents might want to discuss.

However, we also have data suggesting that animated films are a less than ideal source of information about death. First, many of the deaths were implicit, which creates some ambiguity about whether the death occurred and what actually happened to the character. This might be one reason why parents often responded to questions about death in animated films by clarifying what happened in the scene. Second, we found that a number of films contained misconceptions about death. In some instances, characters came back to life, while in other instances, death was portrayed as a deep sleep.

Our content analysis also revealed that death is quite prevalent in children’s animated films and that this prevalence is much greater than in children’s books (Gutierrez et al., 2014). One possibility for the difference in the prevalence of death in the two mediums might be related to implicit deaths. Implying that a character died might be easier to do in a movie, where the camera can focus on a different part of the scene, compared to in a book. It could also be related to how easy it is for parents to skip the death scene. When watching films at home, parents can often fast forward the film to skip the death scene. In books, it might be more complicated or obvious to skip a couple of pages, while maintaining continuity.

In line with the higher prevalence of death in animated films, we also found differences in parental attitudes towards shielding children from death across mediums. Previous work (e.g., Rosengren et al., 2014) has suggested that many parents in the United States attempt to shield their children from death, whereas our results suggest that most of the parents we sampled do not attempt to shield their children from death in animated films. One possibility for this difference might be due to the prevalence of death. Because death is much more common in films, parents might feel more comfortable with allowing children to watch films that contain death, but less comfortable with their children reading books that contain death (as this is rarer).

Another possibility might be related to the social context in which the two activities occur. We found that parents typically watch these films with their children, and so parents might be more comfortable with children being exposed to depictions of death because they can comfort them if the children have a negative reaction. Although shared book reading is a common activity among certain groups in the United States, reading can also be a solitary activity. Rosengren et al (2014) did not ask parents whether they are present when their children read books about death, so it is possible that parents thought of their children reading these books without adult supervision, which might lead to more shielding. Finally, it could be that the difference in parental attitudes is also related to the number of implicit deaths. Because deaths in films are often implied rather than explicitly depicted, parents might be more comfortable with their children watching them. If deaths in books are often explicit, this might account for the different attitudes towards death in different mediums. Future work should examine why parents might treat death in different mediums (storybooks versus films) differently.

Learning about Death from Media