Abstract

This review aims to evaluate whether root canal obturation with calcium silicate-based (CSB) sealers reduces the risk and intensity of endodontic postoperative pain when compared to epoxy resin-based (ERB) sealers. The review was registered at PROSPERO (CRD42020169255). Two independent reviewers conducted an electronic search in PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane Library and LILACS until November 2020 and included only randomized clinical trials with adult health participants undergoing root canal treatment. After selection, the JBI Critical Appraisal tool was used to assess the risk of bias. A fixed-effect meta-analysis was performed to summarize the results of pain risk and pain intensity at time intervals of 24 and 48 hours. Finally, the certainty of evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach. The search resulted in 1,206 records, of which five studies ( n = 421 patients) met the eligibility criteria and presented moderate to low risk of bias. There was no significant difference between groups in the risk of pain in the first 24 hours (relative risk or RR = 0.83, 95% confidence interval or CI: 0.60, 1.16, I 2 =) or 48 hours (RR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.26, 1.21, I 2 =). Silicate-based sealers led to lower pain intensity only at 48 hours (mean and standard deviation = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.69, 0.05). All analyses revealed low heterogeneity ( I 2 < 25%). The evidence presented moderate level of certainty. Currently available evidence has shown that there is no difference between CSB and ERB sealers in the risk or intensity of postoperative pain.

Keywords: endodontic pain, endodontic sealers, postoperative pain, root canal obturation, systematic review

Introduction

Theories suggest that postoperative pain in endodontic treatment may be caused mainly by the exacerbation of the inflammatory process in the periapical region due to the possible extrusion of root canal irrigants, materials, or contaminated dentine debris from the apical foramen during endodontic procedures, as they increase the neuropeptide expression of nerve fibers present in the periodontal ligament. 1 2

In recent randomized clinical trials (RCTs), approximately 40 to 80% of patients report same discomfort after endodontic interventions. 3 4 5 6 Pain evolution reaches its maximum peak in 24 hours and begins to decrease after the second day, reaching minimum levels in 7 days. 7

Some factors are studied to understand their relationship with the occurrence and intensity of postoperative pain, such as extrusion of chemical solutions, 8 type of instrumentation, 3 9 dental pulp status, 1 preoperative pain, 10 11 apical extrusion of filling material, 12 13 occlusal adjustment procedures, 6 14 and photobiomodulation therapy, 4 5 or infrared rays therapy to minimize pain occurrence. 15

Obturation techniques that use thermoplasticized gutta-percha have become more frequent because they result in homogeneous fillings and satisfactory sealing against marginal infiltration, 16 but may favor apical extrusion of filling material. 17 18

The filling material when in contact with the periodontal tissues through the apical foramen can potentially modify the healing process in the periodontium 19 and interfere with the occurrence of postoperative pain. 4 The intensity of inflammatory reactions in the apical region depends on several factors, one of these being the composition of the sealer. 20

Cytotoxicity studies have found that epoxy resin-based (ERB) sealers release toxic monomers that can increase oxidative stress in human cells, which could be associated with the release of reactive oxygen species that provoke pain due to tissue inflammation. 21 Calcium silicate-based (CSB) sealers, on the other hand, present less cytotoxicity when compared to ERB sealers, but they also present a certain degree of cytotoxicity. 22 23

Although there is a growing number of clinicians who have adhered to CSB sealers in their clinical protocols, there is no summarized evidence to prove their superiority to ERB sealers in reducing pain after nonsurgical endodontic treatment. Therefore, the objective of this study was to systematically review the current scientific evidence regarding the influence of epoxy-resin and calcium silicate sealers on the risk and intensity of postoperative pain after root canal treatment.

Methods

Registration of the Protocol

This systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines 24 25 and the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for systematic reviews of effectiveness evidence 26 and registered at PROSPERO (CRD42020169255) and at the Open Science Framework database ( https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/VDM2G ).

Research Question and Outcome

The focused question (PICO) was developed as follows: Does obturation with CSB sealers (intervention) cause less postoperative pain (outcome) than ERB sealers (comparison) in patients undergoing nonsurgical root canal treatment (population)?

The primary outcome of this systematic review was to compare the risk and intensity of postoperative pain after obturation using CSB or epoxy resin sealers.

Selection Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

Population: Healthy patients (>15 years old) undergoing nonsurgical root canal treatment, without restrictions concerning sex, type of endodontic diagnosis, or type of tooth treated.

Intervention: Any CSB sealer.

Comparison: Any ERB sealer.

Outcome: Risk and intensity of postoperative pain at any time interval. The risk of pain was defined as the report of any discomfort after endodontic treatment, regardless of severity; studies should describe the number of patients with and without postoperative pain for both groups. On the other hand, pain intensity was defined as pain severity according to patient-reported pain scales after root canal obturation.

Study design: RCTs.

Exclusion Criteria

Case reports, case series, conference abstracts, or in vivo studies that were not characterized as RCTs.

Studies with pregnant, immunocompromised patients on anti-inflammatory drugs, patients with occlusal disorders, or any type of periodontitis that could interfere with the analysis of the presence of pain after endodontic treatment.

Studies with incomplete data regarding methods for measuring postoperative pain outcomes.

Search Strategy in the Databases and Selection of Studies

PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and LILACS were used for electronic search. The research was carried out until November 2020 with search alerts as a self-updating tool. Open Thesis and Open Grey allowed access to the “gray literature” to avoid publication bias. Moreover, any relevant article obtained from cross-referencing the screened articles was also included.

The following MeSH terms and synonyms were used for the initial search: (“pain, postoperative” OR “postoperative pain” OR “postoperative pains”) AND (“root canal obturation” OR “root canal obturations” OR “endodontic obturation” OR “endodontic obturations” OR “root canal sealer” OR “root canal sealant” OR “root canal filling materials”). The search terms and entry terms were adapted for each database searched (Appendix 1) .

The records were exported to the EndNote X9 program (Thomson Reuters, Toronto, Canada) and the duplicate records were considered only once.

The studies were independently selected by two reviewers for eligibility (E.C.S. and J.V.P.), who analyzed the title and abstract of all studies retrieved. In case of disagreements, a third reviewer (W.A.V.) was consulted. Next, the full texts of the eligible articles were independently retrieved and selected based on the eligibility criteria by the same reviewers from the initial phase. If an article could not be obtained, other study centers were contacted to retrieve the articles from their libraries. In case of studies published in languages other than English or Portuguese, the full text was translated.

Data Extraction from Eligible Studies

After selecting the eligible articles, two independent reviewers (E.C.S. and W.A.V.) extracted the following data: (a) authors, year of publication, and country; (b) sealer groups and sample size; (c) age range and sex distribution; (d) endodontic diagnosis; (e) types of teeth; (f) obturation technique; (g) pain assessment method; (h) assessment interval; (i) results of prevalence and intensity of postoperative pain; and (j) the number of patients on analgesics. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

The correspondent authors were contacted by email (up to three times over 2 weeks) to obtain relevant information in the case of missing or unclear data. Studies that used the visual analogue scale (VAS) with scales from 0 to 100 mm were converted to 0 to 10 cm to the standardization of quantitative analysis.

Risk of Bias of Eligible Studies

Two reviewers (E.C.S. and W.A.V.) assessed the quality of the studies included using the JBI critical assessment tool for RCTs for 13 domains. 26 Lack of agreement between reviewers for any of the questions within the JBI tool was solved by a third examiner (J.V.P.).

The percentage of positive answers to the questions led to the final score of the studies. Studies that scored up to 49% of positive answers were classified as “high risk of bias.” Studies with positive answers between 50 and 69% were classified as “moderate risk of bias,” while studies that scored positive answers above 70% were classified as “low risk of bias.”

Meta-Analysis

The Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 5.3, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used to conduct the meta-analysis. For the dichotomous outcome (risk of postoperative pain), the relative risk (RR) was used, and for the continuous outcome (pain intensity), the mean and standard deviation (MD) presented in the results of the eligible studies were used, with the 95% confidence interval (CI). 27 Subgroup analyses were performed in which the outcomes were organized by the time intervals described in the studies.

Heterogeneity was determined by I 2 test and was classified as: low ( I 2 < 50%), moderate ( I 2 = 50–75%), or high ( I 2 > 75%). A fixed-effect meta-analysis was performed when I 2 was ≤50%.

Supplementary Analysis

A sensitivity analysis was planned to explore the influence of the pulp diagnosis (necrotic and vital teeth) on outcomes; thus, a new meta-analysis was conducted including only one type of pulp diagnosis.

Assessment of Certainty of Evidence (GRADE Approach)

The certainty of the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. The GRADE Pro GDT software ( http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org ) was used to summarize the results. The certainty can be downgraded due to risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. To examine for imprecision of continuous data (pain intensity), we used a threshold of 1 point in the 10-point VAS 28 29 and a minimum OIS of 400 teeth. The level of certainty among the identified evidence can be characterized as very low to high. 30

Results

Selection Process

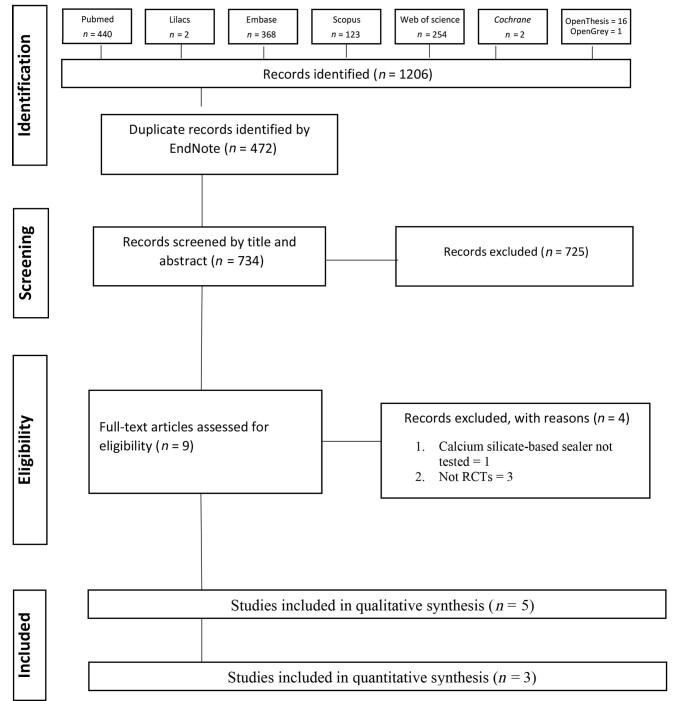

The electronic search identified a total of 1,206 studies, then 472 duplicate studies were removed, resulting in 734 studies for screening. After analyzing the titles and abstracts, nine publications were selected for full-text reading. After reading the articles in full, five studies were finally included in this qualitative analysis 31 32 33 34 35 ( Fig. 1 ). The studies excluded in the full-text analysis and exclusion criteria are shown in ( Appendix 2 ).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart diagram of the study selection process.

Overview of the Included Studies

The studies were published between 2018 and 2020. 31 32 33 34 35 Four studies were parallel-design clinical trials, and one of them was a split-mouth clinical trial. 33 All studies described ethical approval, 31 32 33 34 35 but no studies mentioned CONSORT and only two studies 34 35 mentioned the registration of the clinical trial protocol.

The total analyzed sample was 581 teeth in 421 patients; women were predominant; the mean age was reported in all studies and ranged from 30.69 to 52.6 years ( Table 1 ). Regarding the endodontic diagnosis, four studies included teeth with pulp necrosis, 31 32 33 35 one of which was retreatment. 33 Three studies included patients with irreversible pulpitis. 32 34 35 All articles used AH-Plus as a standard sealer to compare with CSB sealers. All CSB sealers used in the studies presented similar compositions (Appendix 3) .

Table 1. Main characteristics of eligible studies.

| Author, year, country | Sealer/Sample ( n ) | Age (mean in years) | Teeth diagnosis | Type of teeth | Obturation technique | Rescue medication | Pain scale assessment | Interval (in hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; VAS, visual analogic scale. 1 The study performed a split-mouth RCT. 2 The study did not separate the average age per group. 3 Retreatment. 4 It was not presented at the dosage of the drug. + It is not possible to extract the numerical results. | ||||||||

| Fonseca et al, 2019. Brazil | AHPlus: 32 (18F 14M) Sealer Plus BC: 32 (20F 12M) |

AHPlus: 37.09 ± 13.10 Sealer Plus BC: 38.5 ± 14.18 |

Pulp necrosis | Anterior teeth | Single-cone technique filling | 600 mg ibuprofen | VAS | 24, 48, 72, 168 |

| Ates et al, 2019. Turkey | AHPlus: 78 (47F 31M) iRoot SP: 78 (42F 36M) |

AHplus: 30.69 ± 10.39 (Vital teeth) 36.33 ± 11.08 (Necrotic teeth) iRoot SP: 35.00 ± 12.55 (Vital teeth) 40.69 ± 11.87 (Necrotic teeth) |

Pulp necrosis and vital teeth | Posterior teeth | Carrier-based system (Herofill SoftCore) |

200 mg ibuprofen | VAS | 6, 12, 24, 72 |

| Graunaite et al, 2018. Lithuania | AHPlus: 61 (36F 25M) Total Fill BC: 61 (36F 25M) 1 |

49.5 ± 12.82 2 | Asymptomatic apical periodontitis 3 | Anterior or posterior teeth | Warm vertical condensation (Calamus) | Nonsteroid analgesics | VAS | 24, 48, 72, 168 |

| Aslan and Dönmez Özkan, 2020. Turkey. | AHPlus: 30 BC Sealer: 30 EndoSeal MTA: 30 |

AHPlus: 37.15 ± 11.93 BC Sealer: 32.46 ± 13.20 EndoSeal MTA: 39.57 ± 13.09 |

Asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis | Posterior inferior molars | Single-cone technique filling | ibuprofen 400 mg | VAS | 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96,120,144 |

| Seh et al, 2020 Singapore |

AHPlus: 83 (45F 38M) Total Fill BC: 80 (42F 38M) |

+ | Pulp necrosis and vital teeth | Anterior or posterior teeth | Warm vertical condensation (System B) | Ibuprofen 4 | Likert scale |

24, 72, 168 |

Four studies 31 32 33 34 analyzed the pain outcome using numerical scales (VAS 0–10 cm) at intervals ranging from 6 hours to 7 days after procedure, and only one study 35 used the Likert scale. All studies reported the number of patients who were on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) for pain relief. 31 32 33 34 35

Individual Results of Eligible Studies

Pain Occurrence

Only one study 32 assessed the incidence of pain within the first 6 and 12 hours after the procedure, and pain risk was similar between the groups for both time intervals (Appendix 4) .

Four eligible studies 31 32 33 35 assessed the incidence of pain 24 hours after the procedure. The occurrence of pain ranged from 21.1 to 46.9% in the ERB sealer group and from 17.5 to 30.8% in the CSB sealer group. Only two eligible studies 31 33 assessed the occurrence of pain 48 hours after the procedure. Both studies reported a similar reduction in postoperative pain when comparing the 24-hour time interval, but without statistical differences between groups.

In addition, four eligible studies also assessed the occurrence of pain 72 hours after the procedure. 31 32 33 35 There were no reports of pain in two studies 31 33 and there were no statistical differences between the sealers in the other two. 32 35

Pain Intensity

Two studies assessed pain intensity at 6 and 12 hours after the procedure. 32 34 In both time intervals, the authors observed no statistical differences.

All eligible studies 31 32 33 34 35 assessed postoperative pain intensity 24 hours after endodontic treatment. In studies using the VAS scale, the mean scores ranged from 0.46 to 1.46 in patients in the ERB sealer group and from 0.32 to 1.21 in patients in the CSB sealer group. In the other study, 35 which used the Likert scale, few patients reported pain and intensity ranged from very mild pain to severe pain in both groups, with no statistical difference between them. Only three studies 31 33 34 assessed pain intensity after 48 hours and observed similar mean pain scores between the groups (Appendix 5) . After 72 hours, all studies found mean scores close to or equal to zero.

NSAID Intake

Only three studies assessed NSAID intake at 6 and 12 hours after the procedure. 32 34 In both time intervals, the authors observed no statistical differences between groups.

All eligible studies 31 32 33 34 35 assessed NSAID intake 24 hours after endodontic treatment. The number of patients that took at least one tablet of NSAID ranged from two to ten, with no statistical differences between groups in all studies. No patients required any medication after 48 hours in the three eligible studies, 31 32 33 while in one study 34 three patients took at least one tablet after 48 hours.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Four studies presented low bias risk of 31 32 33 34 and one study 35 was classified as moderate risk of bias ( Table 2 ). The main shortcomings were related to blinding. Only two articles did not provide sufficient information if the patients were blinded 32 34 ; three studies did not perform blinding procedures of operators 31 33 and this information was unclear in three studies. 32 34 35 In addition, the blinding procedures for the outcome analysis in four studies were uncertain/not clearly stated in four studies. 31 32 33 34 Moreover, one study 35 presented some deviations from the standard RCT design (Question 13) and reported that the treatment protocol varied according to the complexity of the tooth, so there was no way to ensure that all patients were treated identically (Question 7).

Table 2. Risk of bias assessed by the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools for use in JBI systematic reviews for randomized controlled trials.

| Authors | Q.1 | Q.2 | Q.3 | Q.4 | Q.5 | Q.6 | Q.7 | Q.8 | Q.9 | Q.10 | Q.11 | Q.12 | Q.13 | % yes/risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbreviations: √, Yes; , No; U, unclear. Q1. Was true randomization used for assignment of participants to treatment groups? Q2. Was allocation to treatment groups concealed? Q3. Were treatment groups similar at the baseline? Q4. Were participants blind to treatment assignment? Q5. Were those delivering treatment blind to treatment assignment? Q6. Were outcomes assessors blind to treatment assignment? Q7. Were treatment groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest? Q8. Was follow-up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow-up adequately described and analyzed? Q9. Were participants analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized? Q10. Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups? Q11. Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? Q12. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? Q13. Was the trial design appropriate, and any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomization, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial? | ||||||||||||||

| Seh et al, 2020 | U | √ | U | √ | U | √ | – | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | – | 61.5%/moderate risk |

| Aslan and Dönmez Özkan, 2020 | √ | √ | √ | U | U | U | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 76.9%/low risk |

| Fonseca et al, 2019 | √ | √ | √ | √ | – | U | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 84.6%/low risk |

| Ates et al, 2019 | √ | √ | √ | U | U | U | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 76.9%/low risk |

| Graunaite et al, 2018 | √ | √ | √ | √ | – | U | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 84.6%/low risk |

Summary of Results and Meta-Analysis

A meta-analysis for the NSAIDs intake was not performed due to the low number of events reported in the eligible studies and the different periods evaluated. Thus, three studies were included in the quantitative analysis of risk and intensity of postoperative pain. 31 32 33 One study did not present extractable data 34 and it was excluded from the analysis; the corresponding author was contacted but the missing data was not provided. Moreover, we decided not to include one study 35 because other clinical factors that could have influenced pain (number of visits, severity of the cases, experience of operators, and sonic activation) were not controlled during the root canal treatment.

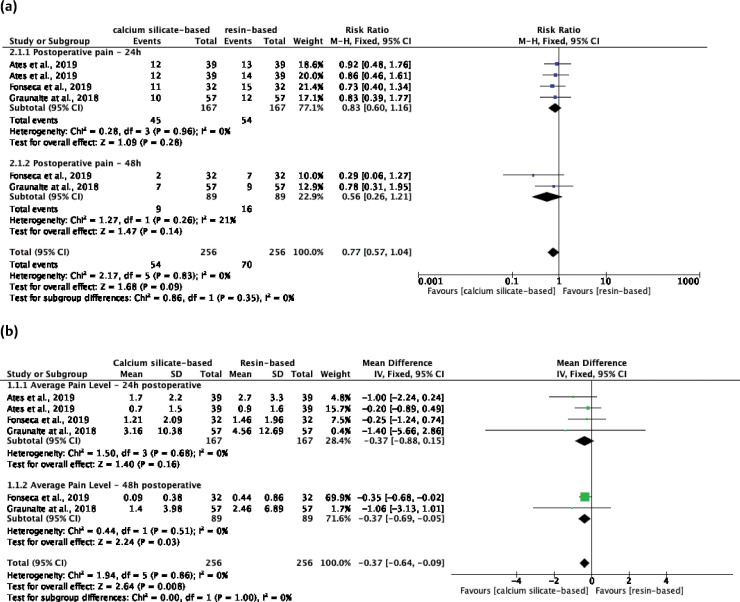

Risk of Pain

The meta-analysis that assessed the RR for developing postoperative pain between the types of sealers was carried out in subgroups according to the time intervals of 24 and 48 hours. The heterogeneity ( I 2 ) in both subgroups was low (0 and 21%, respectively), leading to the fixed-effect model. No significant difference was observed in the risk of pain at 24 hours (RR: 0.83 95% CI = 0.60, 1.16, p = 0.28) or 48 hours (RR: 0.56 95% CI = 0.26, 1.21, p = 0.14) after treatment in patients who received different types of endodontic sealers ( Fig. 2A ).

Fig. 2.

( A ) Meta-analysis of the relative risk (RR) for developing postoperative pain among types of sealers. ( B ) Meta-analysis that assessed the intensity of pain among different types of sealers.

It was not possible to perform a meta-analysis for the time interval of 72 hours because only one study 32 reported the occurrence of pain within that period.

Pain Intensity

The meta-analysis that assessed the intensity of pain between different types of sealers was carried out in the subgroups at 24 and 48 hours and showed low heterogeneity in both subgroups ( I 2 = 0%), leading to the fixed-effect model. Within the first 24 hours, there was no significant difference in mean pain intensity among patients who were treated with different types of sealers (MD, 0.37, 95% CI = 0.88, 0.15, p = 0.16). However, at 48 hours, lower intensity of pain was associated with CSB sealers (MD, 0.37,95% CI = 0.69, 0.05, p = 0.03) ( Fig. 2B ).

The meta-analysis that assessed the intensity of pain at 72 hours was not performed because all studies found mean scores close to or equal to 0.

Sensitivity Tests

No differences in risk or intensity of pain after 24 hours were observed through the sensitivity test of patients with necrotic teeth. The sensitivity test with patients with vital pulp was not performed because only one study 32 presented the data. There was no change in the results in the 48-hour subgroups of both outcomes because only necrotic teeth were included in the primary analyses ( Supplementary Fig. 1A 1B ).

Certainty of Evidence

For each outcome two analyses of certainty of evidence were performed based on the time intervals investigated (24 and 48 hours). All analyses presented moderate level of certainty ( Table 3 ). All analyses were downgraded due to imprecision (wide credible intervals and/or low number of participants).

Table 3. Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) summary of findings and table for the outcomes of the systematic review.

| Certainty assessment | Summary of results | Certainty | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies (sample) | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Effect | |

| Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval. ¶ Effect estimate (MD: mean and standard deviation). ≠ Effect estimate (RR: relative risk). a All studies presented at low risk of bias. b Similar effect estimates among different studies, overlap of 95% CI, low I 2 , and nonsignificant p -value. c The evidence comes from adults undergoing root canal treatment, and we can apply to the patients of our PICO question. d Total number of teeth is lower than optimal information size (OIS) considered the minimum ideal (400)—rated down one level due to imprecision. e 95% CI cross-the line of null effect (1.0)—rated down one level due imprecision. Note: GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty : We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty : We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||||

| Pain intensity—24 h after root canal treatment | ||||||||

| 3 ( n = 342 teeth) | Randomized trials | Not serious a | Not serious b | Not serious c | Serious d | None |

MD

¶

(95% CI)

0.37 (0.88, 0.15) |

⊕⊕⊕ MODERATE |

| Pain intensity—48 h after root canal treatment | ||||||||

| 2 ( n = 186 teeth) | Randomized trials | Not serious a | Not serious b | Not serious c | Serious d | None |

MD

¶

(95% CI)

0.37 (0.69, 0.05) |

⊕⊕⊕ MODERATE |

| Pain risk—24 h after root canal treatment | ||||||||

| 3 ( n = 342 teeth) | Randomized trials | Not serious a | Not serious b | Not serious c | Serious e | None |

RR

≠

(95% CI)

0.83 (0.60, 1.16) |

⊕⊕⊕ MODERATE |

| Pain risk—48 h after root canal treatment | ||||||||

| 2 ( n = 186 teeth) | Randomized trials | Not serious a | Not serious b | Not serious c | Serious e | None |

RR

≠

(95% CI)

0.56 (0.26, 1.21) |

⊕⊕⊕ MODERATE |

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to answer whether CSB sealers are related to lower pain risk and intensity after root canal treatment when compared with ERB sealers. The meta-analysis showed that CSB sealers are not associated with lower risk or clinically significant less intensity of pain following root canal treatment after 24 or 48 hours.

Root canal treatment comprises several procedures that can cause an inflammatory response in the periapical region, 36 known to be associated with the release of biochemical mediators, such as reactive oxygen species that are responsible for in vivo inflammatory pain. 37 In this systematic review, the type of sealers was the variable chosen to analyze the pain outcome between the intervention and control groups, since the contact of the filling material with the periapical tissues may lead to an inflammatory response. 38

Although some studies have reported that sealer extrusion can cause postoperative complications, 39 40 the individual results of the eligible studies showed no association between cases of sealer extrusion and the occurrence and intensity of postoperative pain, 31 32 33 34 35 regardless of the type of sealer. This result can be justified by the fact that the amount of extruded cement reported in the studies was small, not enough to promote a significant inflammatory response in the periapical tissues. 41 However, this is a variable that requires further clinical studies, and it was not assessed in our meta-analyses due to the lack of information regarding sealer extrusion and pain incidence within the groups in the eligible studies.

Regarding the type of sealers used, the ERB sealer chosen for the control group in all eligible studies 31 32 33 34 35 was AH-Plus (Dentsply Maillefer), which is slightly cytotoxic as it releases monomers such as bisphenol A diglycidyl ether 22 42 and its extrusion can delay periapical recovery. 19 On the other hand, the CSB sealers used in the eligible studies (Total Fill BC, Sealer Plus BC, iRoot SP EndoSequence BC, and Endoseal MTA) have no resin in their composition, they have a shorter setting time, better cell viability and cell migration ability in comparison with AH-Plus. 43

Despite this, in none of eligible clinical trials in this systematic review there were statistically significant differences in terms of the incidence among the studied sealers. These data were confirmed in the results of this meta-analysis in which the relative risk for the occurrence of pain was not significant among the groups.

Additionally, another interesting finding of our review is that in the individual results of the eligible studies there was no statistical differences in pain intensity between the groups, at any time interval. However, in the results of our meta-analysis, the association of lower intensity of postoperative pain occurred within 48 hours in favor of CSB sealers; this result can be explained by the fact that the meta-analysis is composed of a larger sample and results in a decreased accuracy of the effect estimates. Yet, this difference observed in our meta-analysis cannot be interpreted as clinically significant, since it does not cross the limit established as relevant for patients. 28 29

Both meta-analyses emphasize the limitations of interpreting in vitro results, in which CSB sealers show superior biological results when compared with ERB sealers, suggesting better inflammatory responses after endodontic treatment. 20 44 However, the results observed in the present meta-analyses go against these laboratory findings, since both groups of sealers did not differ in terms of the incidence and intensity of postoperative pain presented by patients. We believe that these data can be attributed to the fact that although ERB sealers have greater cytotoxicity, this characteristic is not clinically sufficient to promote a more intense inflammatory process when in contact with periapical tissues, which may justify the nondifference between groups in the present meta-analyses.

It is common in clinical trials to assess postoperative pain to use a rescue medication when discomfort is greater than the one expected by the patient. The results of the included studies show that a small number of the patients needed analgesics/anti-inflammatory drugs during their postoperative period, irrespective of the group in which they were allocated. These findings reinforce the nondifference in postoperative pain risk or intensity between ERB and CSB sealers and also highlight the fact that the incidence of relevant postoperative pain after root canal treatment was too low when these sealers were used, which suggests that both sealers were adequate. Yet, in future studies, we suggest standardizing the dosage and the type of anti-inflammatory drug used, in addition to assessing the impact of its consumption as a possible confounding factor in the analysis.

This study is not free of limitations. Although studies assess postoperative pain, the reported data regarding sealer extrusion and the lack of standardization in the rescue medication doses have made it impossible to perform a meta-analysis for these events. Another limitation was the small number of articles and participants included in the quantitative analysis, which limited the certainty of the body of evidence. On the other hand, this is the first meta-analysis that compares postoperative pain caused by root canal obturation with CSB or ERB sealers.

Future CTs should be prioritized following the recommendations of CONSORT 45 or PRIRATE 46 and standardizing the blinding of participants during selection, measurement, and data analysis, since blinding the operator can be difficult in endodontic interventions. Preference should be given to standardizing the use of numerical rating scales (0–10 cm) to analyze pain intensity, as they are more statistically sensitive than visual analogue scales that use scores. 47 The assessment periods should seek time intervals of 06, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours, since postoperative discomfort is more frequent within the first 2 days. 7 36

Conclusion

Based on a moderate certainty, currently available evidence has shown that CSB sealers do not decrease the risk and intensity of postoperative pain when compared with ERB sealers after 24 or 48 hours. Future well-designed RCTs should be performed to increase the precision and certainty of future meta-analysis and evaluate postoperative pain in different pulp and periodontal status.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the public funding agency, Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel of the Ministry of Education (CAPES), for support by PROCAD notice (grant number: 88887.473221/2020-00) and PROEX (grant number: 001). The sponsors had no role in study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing the report, or decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Appendix and Supplementary

References

- 1.Gotler M, Bar-Gil B, Ashkenazi M. Postoperative pain after root canal treatment: a prospective cohort study. Int J Dent. 2012;2012:310467. doi: 10.1155/2012/310467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sipavičiūtė E, Manelienė R. Pain and flare-up after endodontic treatment procedures. Stomatologija. 2014;16(01):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Relvas JB, Bastos MM, Marques AA, Garrido AD, Sponchiado EC., Jr. Assessment of postoperative pain after reciprocating or rotary NiTi instrumentation of root canals: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2016;20(08):1987–1993. doi: 10.1007/s00784-015-1692-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopes LPB, Herkrath FJ, Vianna ECB, Gualberto Júnior EC, Marques AAF, Sponchiado Júnior EC. Effect of photobiomodulation therapy on postoperative pain after endodontic treatment: a randomized, controlled, clinical study. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23(01):285–292. doi: 10.1007/s00784-018-2435-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nunes EC, Herkrath FJ, Suzuki EH, Gualberto Júnior EC, Marques AAF, Sponchiado Júnior EC. Comparison of the effect of photobiomodulation therapy and Ibuprofen on postoperative pain after endodontic treatment: randomized, controlled, clinical study. Lasers Med Sci. 2020;35(04):971–978. doi: 10.1007/s10103-019-02929-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vianna ECB, Herkrath FJ, Martins IEB, Lopes LPB, Marques AAF, Sponchiado Júnior EC. Effect of occlusal adjustment on postoperative pain after root canal treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Braz Dent J. 2020;31(04):353–359. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440202003248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pak JG, White SN. Pain prevalence and severity before, during, and after root canal treatment: a systematic review. J Endod. 2011;37(04):429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mostafa MEHAA, El-Shrief YAI, Anous WIO et al. Postoperative pain following endodontic irrigation using 1.3% versus 5.25% sodium hypochlorite in mandibular molars with necrotic pulps: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Int Endod J. 2020;53(02):154–166. doi: 10.1111/iej.13222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comparin D, Moreira EJL, Souza EM, De-Deus G, Arias A, Silva EJNL. Postoperative pain after endodontic retreatment using rotary or reciprocating instruments: a randomized clinical trial. J Endod. 2017;43(07):1084–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elzaki WM, Abubakr NH, Ziada HM, Ibrahim YE. Double-blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of efficiency of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the control of post-endodontic pain. J Endod. 2016;42(06):835–842. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadaf D, Ahmad MZ. Factors associated with postoperative pain in endodontic therapy. Int J Biomed Sci. 2014;10(04):243–247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alonso-Ezpeleta LO, Gasco-Garcia C, Castellanos-Cosano L, Martín-González J, López-Frías FJ, Segura-Egea JJ. Postoperative pain after one-visit root-canal treatment on teeth with vital pulps: comparison of three different obturation techniques. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17(04):e721–e727. doi: 10.4317/medoral.17898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng L, Ye L, Tan H, Zhou X. Outcome of root canal obturation by warm gutta-percha versus cold lateral condensation: a meta-analysis. J Endod. 2007;33(02):106–109. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emara RS, Abou El Nasr HM, El Boghdadi RM. Evaluation of postoperative pain intensity following occlusal reduction in teeth associated with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis and symptomatic apical periodontitis: a randomized clinical study. Int Endod J. 2019;52(03):288–296. doi: 10.1111/iej.13012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anitasari S, Wahab DE, Barlianta B, Budi HS. Determining the effectivity of infrared distance to eliminate dental pain due to pulpitis and periodontitis. Eur J Dent. 2020;14(03):360–365. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1714454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gençoglu N, Oruçoglu H, Helvacıoḡlu D. Apical leakage of different gutta-percha techniques: thermafil, js quick-fill, soft core, microseal, system B and lateral condensation with a computerized fluid filtration meter. Eur J Dent. 2007;1(02):97–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tennert C, Jungbäck IL, Wrbas KT. Comparison between two thermoplastic root canal obturation techniques regarding extrusion of root canal filling—a retrospective in vivo study . Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17(02):449–454. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0726-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong AW, Zhang S, Li SK, Zhang C, Chu CH. Clinical studies on core-carrier obturation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17(01):167. doi: 10.1186/s12903-017-0459-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sari S, Duruturk L. Radiographic evaluation of periapical healing of permanent teeth with periapical lesions after extrusion of AH Plus sealer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104(03):e54–e59. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang W, Peng B. Tissue reactions after subcutaneous and intraosseous implantation of iRoot SP, MTA and AH Plus. Dent Mater J. 2015;34(06):774–780. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2014-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camargo CH, Camargo SE, Valera MC, Hiller KA, Schmalz G, Schweikl H. The induction of cytotoxicity, oxidative stress, and genotoxicity by root canal sealers in mammalian cells. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108(06):952–960. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang W, Li Z, Peng B. Ex vivo cytotoxicity of a new calcium silicate-based canal filling material. Int Endod J. 2010;43(09):769–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fonseca DA, Paula AB, Marto CM et al. Biocompatibility of root canal sealers: a systematic review of in vitro and in vivo studies. Materials (Basel) 2019;12(24):E4113. doi: 10.3390/ma12244113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.PRISMA Group . Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(07):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(07):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tufanaru CMZ, Aromataris E, Campbell J, Hopp L.Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute2017 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. Available at: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bodian CA, Freedman G, Hossain S, Eisenkraft JB, Beilin Y. The visual analog scale for pain: clinical significance in postoperative patients. Anesthesiology. 2001;95(06):1356–1361. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200112000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dawdy J, Halladay J, Carrasco-Labra A, Araya I, Yanine N, Brignardello-Petersen R. Efficacy of adjuvant laser therapy in reducing postsurgical complications after the removal of impacted mandibular third molars: a systematic review update and meta-analysis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148(12):887–9.02E6. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2017.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balshema H, Helfand M, Scheunemannc HJ et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. original. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:5. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fonseca B, Coelho MS, Bueno CEDS, Fontana CE, Martin AS, Rocha DGP. Assessment of extrusion and postoperative pain of a bioceramic and resin-based root canal sealer. Eur J Dent. 2019;13(03):343–348. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3399457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atav Ates A, Dumani A, Yoldas O, Unal I. Post-obturation pain following the use of carrier-based system with AH Plus or iRoot SP sealers: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23(07):3053–3061. doi: 10.1007/s00784-018-2721-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graunaite I, Skucaite N, Lodiene G, Agentiene I, Machiulskiene V. Effect of resin-based and bioceramic root canal sealers on postoperative pain: a split-mouth randomized controlled trial. J Endod. 2018;44(05):689–693. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aslan T, Dönmez Özkan H. The effect of two calcium silicate-based and one epoxy resin-based root canal sealer on postoperative pain: a randomized controlled trial. Int Endod J. 2020;54:190–197. doi: 10.1111/iej.13411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seh Gabriel TH, Chong LK, Nee LJ, Ming Clement LW, Hoon Yu VS.Post-obturation pain associated with tricalcium silicate and resin-based sealer techniques - a randomized clinical trial J Endod 2020(e-pub ahead of print) 10.1016/j.joen.2020.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagendrababu V, Gutmann JL. Factors associated with postobturation pain following single-visit nonsurgical root canal treatment: a systematic review. Quintessence Int. 2017;48(03):193–208. doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a36894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vengerfeldt V, Mändar R, Saag M, Piir A, Kullisaar T. Oxidative stress in patients with endodontic pathologies. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2031–2040. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S141366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosen E, Goldberger T, Taschieri S, Del Fabbro M, Corbella S, Tsesis I. The prognosis of altered sensation after extrusion of root canal filling materials: a systematic review of the literature. J Endod. 2016;42(06):873–879. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.González-Martín M, Torres-Lagares D, Gutiérrez-Pérez JL, Segura-Egea JJ. Inferior alveolar nerve paresthesia after overfilling of endodontic sealer into the mandibular canal. J Endod. 2010;36(08):1419–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alves FR, Coutinho MS, Gonçalves LS. Endodontic-related facial paresthesia: systematic review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2014;80:e13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santoro V, Lozito P, Donno AD, Grassi FR, Introna F. Extrusion of endodontic filling materials: medico-legal aspects. two cases. Open Dent J. 2009;3:68–73. doi: 10.2174/1874210600903010068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lodienė G, Kopperud HM, Ørstavik D, Bruzell EM. Detection of leachables and cytotoxicity after exposure to methacrylate- and epoxy-based root canal sealers in vitro. Eur J Oral Sci. 2013;121(05):488–496. doi: 10.1111/eos.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seo DG, Lee D, Kim YM, Song D, Kim SY. Biocompatibility and mineralization activity of three calcium silicate-based root canal sealers compared to conventional resin-based sealer in human dental pulp stem cells. Materials (Basel) 2019;12(15):E2482. doi: 10.3390/ma12152482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodríguez-Lozano FJ, García-Bernal D, Oñate-Sánchez RE, Ortolani-Seltenerich PS, Forner L, Moraleda JM. Evaluation of cytocompatibility of calcium silicate-based endodontic sealers and their effects on the biological responses of mesenchymal dental stem cells. Int Endod J. 2017;50(01):67–76. doi: 10.1111/iej.12596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF et al. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Group. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(08):e1–e37. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagendrababu V, Duncan HF, Bjørndal L et al. PRIRATE 2020 guidelines for reporting randomized trials in Endodontics: a consensus-based development. Int Endod J. 2020;53(06):764–773. doi: 10.1111/iej.13294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(07):798–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.