Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) genomes have been detected in wastewater worldwide. However, the assessment of SARS-CoV-2 infectivity in wastewater has been limited due to the stringent requirements of biosafety level 3. The main objective of this study is to investigate the applicability of capsid integrity RT-qPCR for the selective detection of intact SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater. Three capsid integrity reagents, namely ethidium monoazide (EMA, 0.1–100 μM), propidium monoazide (PMA, 0.1–100 μM), and cis-dichlorodiammineplatinum (CDDP, 0.1–1000 μM), were tested for their effects on different forms (including free genomes, intact and heat-inactivated) of murine hepatitis virus (MHV), which was used as a surrogate for SARS-CoV-2. CDDP at a concentration of 100 μM was identified as the most efficient reagent for the selective detection of infectious MHV by RT-qPCR (CDDP-RT-qPCR). Next, two common virus concentration methods including ultrafiltration (UF) and polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation were investigated for their compatibility with capsid integrity RT-qPCR. The UF method was more suitable than the PEG method since it recovered intact MHV (mean ± SD, 38% ± 29%) in wastewater much better than the PEG method did (0.013% ± 0.015%). Finally, CDDP-RT-qPCR was compared with RT-qPCR alone for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in 16 raw wastewater samples collected in the Greater Tokyo Area. Five samples were positive for SARS-CoV-2 when evaluated by RT-qPCR alone. However, intact SARS-CoV-2 was detected in only three positive samples when determined by CDDP-RT-qPCR. Although CDDP-RT-qPCR was unable to determine the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater, this method could improve the interpretation of positive results of SARS-CoV-2 obtained by RT-qPCR.

Keywords: Capsid integrity RT-qPCR, SARS-CoV-2, intact virus, concentration method, wastewater

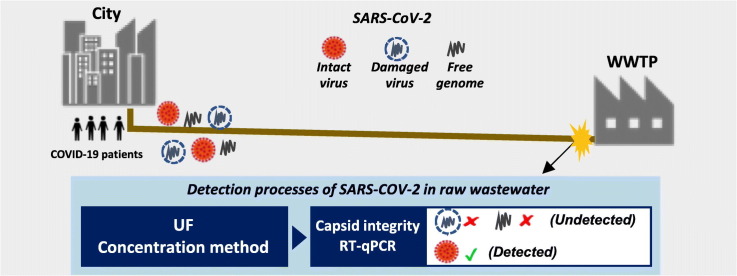

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a global concern that has spread throughout more than 200 countries and has caused approximately three million confirmed deaths worldwide (WHO, 2021). SARS-CoV-2 is mainly transmitted among people via respiratory droplets and contact routes. However, the presence of high concentrations (up to 108 copies/g of feces) of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of infected people has also been commonly reported (Chen et al., 2020; Cheung et al., 2020; Lescure et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020b). Several studies have successfully isolated viable SARS-CoV-2 from the urine and feces of COVID-19 patients (Sun et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020), thus raising concerns about the possible transmission of SARS-CoV-2 through the fecal-oral route. Recently, it was found that 1.5 and 1.7 days were required for a 1.0 log reduction (T90) of infectious SARS-CoV-2 at room temperature (20 °C) in wastewater and tap water, respectively (Bivins et al., 2020). At cool water temperatures, infectious SARS-CoV-2 was able to survive much longer. Indeed, Camilo et al. (2020) reported that the T90 values of infectious SARS-CoV-2 were 7.7 and 5.5 days and the T99 (time required for a 2 log reduction) values were 18.7 and 17.5 days in river water and wastewater at 4 °C, respectively. This evidence suggests that exposure to wastewater contaminated with SARS-CoV-2 might be associated with certain risks, particularly during the low-temperature season in places where sanitation infrastructure is not available or is insufficient (Bao and Canh, 2021; Pandey et al., 2021).

To date, in an attempt to monitor wastewater for tracking the spread of COVID-19 in human communities (wastewater surveillance), SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been detected in raw wastewater in many countries around the world, including in Japan, the United States, France, the Netherlands, Italy, Australia, Spain, India, Pakistan, and China, with concentrations ranging from 102 to 106 copies/L (Ahmed et al., 2020a; Haramoto et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2020; Medema et al., 2020; Randazzo et al., 2020; Rimoldi et al., 2020; Sharif et al., 2020; Sherchan et al., 2020; Trottier et al., 2020; Wurtzer et al., 2020b; Zhang et al., 2020a). Furthermore, several studies have reported the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in treated wastewater (<104–105 copies/L) (Wurtzer et al., 2020a), river water (105–106 copies/L) (Guerrero-Latorre et al., 2020), and sewage sludge (103–105 copies/mL of primary sludge) (Peccia et al., 2020). However, the infectivity or even the structure of SARS-CoV-2 (e.g., intact or compromised) was not assessed since most previous studies utilized RT-qPCR for virus detection. Although cell culture assays are the gold standard for detecting viable viruses, they are laborious, time-consuming, and expensive. More importantly, biosafety level 3 laboratories are required to incubate infective SARS-CoV-2 due to its high infection risk. Therefore, the assessment of SARS-CoV-2 infectivity in water environments remains limited (Rimoldi et al., 2020). To better understand the infection risks via water/wastewater contaminated with SARS-CoV-2, a simple, rapid, and reliable method is necessary for detecting infectious SARS-CoV-2.

Capsid integrity RT-qPCR has been recently developed to overcome the limitations of conventional RT-qPCR and thus to discriminate infectious from damaged viruses. In this approach, samples are pretreated with capsid integrity reagents such as monoazide dyes (e.g., ethidium monoazide (EMA), propidium monoazide (PMA) and PMAxx (a new version of PMA)), or more recently metal compounds (e.g., cis-dichlorodiammineplatinum (CDDP) and platinum (IV) chloride (PtCl4)) prior to RT-qPCR. These reagents can bind to the genomes of damaged viruses with a compromised capsid and subsequently inhibit their detection by RT-qPCR. Therefore, only the genomes of viruses with an intact capsid (potentially infectious viruses) can be detected by capsid integrity RT-qPCR. In recent decades, capsid integrity RT-qPCR has been intensively studied to assess the infectivity of various enteric viruses such as hepatitis A virus, hepatitis E virus, rotaviruses, adenoviruses, noroviruses, and the Aichi virus (AiV) in water and foodstuffs (Coudray-meunier et al., 2013; Fuster et al., 2016; Leifels et al., 2015, Leifels et al., 2021; Randazzo et al., 2018; Sangsanont et al., 2014). More recently, this method was also applied to assess the capsid integrity of enteric viruses in tap water (Canh et al., 2021; Prevost et al., 2016) and to predict the infectivity of noroviruses in bottled water associated with a gastroenteritis outbreak in an epidemiological investigation (Blanco et al., 2017). Therefore, capsid integrity RT-qPCR may be applicable for the selective detection of potentially infectious SARS-CoV-2 in environmental waters. However, most studies thus far have focused on non-enveloped enteric viruses, which have a different structure than that of SARS-CoV-2 (an enveloped virus). Indeed, enveloped viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 are coated with a lipid bilayer membrane that is not present in the structure of non-enveloped viruses. In a recent study, a propidium monoazide compound (PMAxx) combined with RT-qPCR (PMAxx-RT-qPCR) was compared with conventional RT-qPCR and infectivity assay to assess the persistence of different forms of SARS-CoV-2 (free RNA, protected RNA and infectious virus) in wastewater under the impact of water temperature (Wurtzer et al., 2021). However, this study directly applied 100 μM PMAxx without optimizing the PMAxx concentration. More recently, although capsid integrity reagents (monoazide dyes and platinum compounds) were optimized based on free RNA and inactivated SARS-CoV-2 suspended in buffer and urine and stool specimens, the effects of these reagents on infectious or intact SARS-CoV-2 were not investigated (Cuevas-ferrando et al., 2021). In a previous study, the MS2 bacteriophage was found to be inactivated after exposure to a high concentration of capsid integrity reagents (particularly, PMA > 125 μM) (Kim and Ko, 2012). Since little is known about the interaction of capsid integrity reagents on enveloped viruses, capsid integrity RT-qPCR must be developed/optimized for the detection of enveloped viruses, particularly SARS-CoV-2.

In wastewater surveillance strategies for SARS-CoV-2 conducted across the world, virus concentration methods such as ultrafiltration (UF) and polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation have been commonly used to recover SARS-CoV-2 RNA before the virus is quantified by RT-qPCR (Kitajima et al., 2020). These virus concentration methods were confirmed to be effective for the recovery of SARS-CoV-2 surrogates (such as murine hepatitis virus (MHV) and Pseudomonas phage φ6) in wastewater samples (Ahmed et al., 2020c; Torii et al., 2021). However, the compatibility of these virus concentration methods with capsid integrity RT-qPCR is concerning because if an intact capsid of the viruses is compromised, capsid integrity reagents could block those viruses from being detected by RT-qPCR and eventually cause false-negative results.

This current study aimed to investigate the applicability of capsid integrity RT-qPCR for the selective detection of intact SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater. Given the stringent requirements for handling SARS-CoV-2 (biosafety level 3), MHV was used as a model virus to optimize capsid integrity RT-qPCR since MHV also belongs to the genus Betacoronavirus and thus has a similar morphology to that of SARS-CoV-2 (Gorbalenya et al., 2020). Additionally, MHV has previously been used as a useful surrogate for investigating the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in water or evaluating the recovery efficiency of virus concentration methods for SARS-CoV-2 (Ahmed et al., 2020b; Bivins et al., 2020). We tested three capsid integrity reagents (including EMA, PMA, and CDDP) to determine the most effective one for the selective detection of intact MHV by RT-qPCR. Next, the effects of virus concentration methods (including the UF and PEG precipitation methods) on viral structure were evaluated using spiked MHV in raw wastewater. Finally, the optimal concentration method and effective capsid integrity RT-qPCR were applied to assess the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in raw wastewater.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of intact virus stock and infectivity assay

All the laboratory works were conducted at the Graduate School of Engineering, the University of Tokyo. MHV A59 strain (ATCC VR-764) was propagated using DBT cells. The DBT cells were grown in Eagle's minimum essential medium (MEM, Wako, Japan) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in a 75-cm2 flask. The semi-confluent DBT cells were inoculated with MHV and incubated in MEM with 1% FBS at 37 °C (5% CO2) for 3 days. Then, the flask was frozen and thawed once to recover the MHV. The recovered MHV was purified by membrane filtration with a cellulose acetate filter (0.2 μm, DISMIC-25CS, Advantec, Tokyo, Japan) and gel filtration with an Illustra Microspin S-300 HR column (GE Healthcare, Tokyo, Japan) (Kitajima et al., 2010; Sangsanont et al., 2014). The purified MHV was regarded as intact MHV stock. The intact virus stock was aliquoted and maintained at −80 °C until use.

The infective MHV was enumerated by the most probable number assay (Meister et al., 2018; Torii et al., 2020) using DBT cells on 96-well plates, with four serial dilutions and five replicates. The samples to be quantified were serially diluted by 10-fold using maintenance medium, supplemented with 1% FBS. Each well was inoculated with 150 μL of the diluted samples. After 3 days of incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2, the presence of cytopathic effects was monitored by microscopy. The number of positive wells of each dilution was counted and analyzed by an R package (Ferguson and Ihrie, 2019).

Murine norovirus (MNV, S7-PP3 strain) was propagated using RAW.264.7 cells as a host, as described elsewhere (Kitajima et al., 2008). The propagated stocks were stored at −80 °C prior to the experiment.

2.2. Preparation of free viral RNA

Free viral RNA was prepared from purified virus stocks after RNA extraction (as described below). Free viral RNA stock was aliquoted and maintained at −80 °C until use.

2.3. Capsid integrity treatments

EMA powder (phenanthiridium, 3-amino-8-azido-5-ethyl-6-phenyl, bromide; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) was dissolved in Milli-Q water to obtain a stock solution (10 mM). PMA solution (20 mM in H2O) was obtained from Biotium, Inc., Fremont, CA, USA. CDDP (powder form, Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in DMSO to obtain a concentration of 100 mM. After preparation, the EMA, PMA, and CDDP stock solutions were stored at −20 °C in the dark until use.

EMA, PMA, or CDDP treatment was conducted according to our previous study (Canh et al., 2019). Briefly, EMA, PMA, or CDDP stock solution (14 μL) was added to the water samples (126 μL) to obtain the desired concentration. EMA or PMA spiked samples were incubated in the dark at 4 °C for 30 min and then exposed to a halogen light (650 W, Selecon Pacific, Auckland, New Zealand) for 3 min at a distance of 15 cm from the light source. During the light exposure, the samples were placed on ice water to minimize heating effects. It was confirmed that the light exposure had no damage effects on viral capsid (data not shown). For the CDDP treatment, CDDP spiked samples were incubated at room temperature (20 °C) for 30 min. Light exposure was not required for the CDDP treatment. Then, the samples treated with EMA, PMA, or CDDP were subjected to nucleic acid extraction (as described below).

2.4. Nucleic acid extraction, reverse transcription, and qPCR detection

Viral RNA was extracted from 140-μL water samples using the QIAamp viral RNA Minikit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The extracted viral RNA was subjected to reverse transcription (RT) to synthesize cDNA using the high-capacity cDNA RT kit (Applied Biosystems, Tokyo, Japan).

Real-time PCR (qPCR) was conducted using 20 μL of a reaction mixture that contained cDNA (5 μL), TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (10 μL) (Applied Biosystems), forward primer and reverse primer (final concentration, 0.5 μM for MNV and SARS-CoV-2 or 0.3 μM for MHV), TaqMan probe (final concentration, 0.125 μM for MNV and SARS-CoV-2 or 0.4 μM for MHV), and nuclease-free water. Quantification of MHV and MNV was performed using a primer and probe set according to previous studies (Besselsen et al., 2002; Kitajima et al., 2008). SARS-CoV-2 quantification was performing using a primer and probe set (CDC_N1) according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the USA (CDC, 2020). The number of viral genome copies per qPCR reaction was determined from a standard curve using gBlocks or plasmid DNA (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, US) containing the target sequence for each amplification. Standard curves were generated by 10-fold serial dilutions (5 × 104–5 × 100 copies/reaction).

2.5. Heat treatment

Samples (200 μL each, approximately 103 plaque-forming units (PFU)/mL) in 1.5-mL microtubes were incubated at 50, 60, 70, and 80 °C for 2 min in a dry block heater (Nissin, Tokyo, Japan), and immediately placed on ice water at the end of the experiment. One sample was maintained at 4 °C as a control.

2.6. Virus concentration

2.6.1. Ultrafiltration (UF)

The wastewater samples (100 mL) were first centrifuged at 3,500 ×g for 15 min to remove particles. The supernatant was further concentrated using a UF device (Centricon Plus-70; Millipore) with a molecular weight cut-off of 30 kDa according to the manufacturer's protocol to obtain a final volume of 0.4–1.0 mL.

2.6.2. PEG precipitation

PEG precipitation was conducted as described in a previous study (Torii et al., 2021). Briefly, sample centrifugation (100 mL) was performed at 3,500 ×g for 15 min to remove particles. The supernatant (80 mL) was supplemented with 8 g of PEG8000 and 4.7 g of NaCl to reach final concentrations of 10% (w/v) and 1.0 M, respectively. The mixture was incubated at 4 °C overnight in a shaker. Then, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 ×g for 30 min. After carefully discarding the supernatant, the precipitate was resuspended with 10 mM phosphate buffer. The concentrate had a final volume of 1.0 mL.

2.7. Screening of capsid integrity reagents

First, three different capsid integrity reagents (including EMA, PMA, and CDDP) were tested to identify the most effective concentration for each capsid integrity reagent. For this purpose, intact MHV and its free RNA were treated with EMA (0.1, 1, 10, and 100 μM), PMA (0.1, 1, 10, and 100 μM), and CDDP (0.1, 1, 10, 100, 500, and 1,000 μM) and then subjected to RT-qPCR. The control was conducted without EMA/PMA/CDDP treatment. The highest concentration of EMA (100 μM), PMA (100 μM) and CDDP (1000 μM) was confirmed to have no inhibitory effects on RT-qPCR amplification (data not shown). All samples were tested in triplicate.

The most suitable concentration of each capsid integrity reagent was further tested with heat-inactivated MHV to determine the most effective capsid integrity reagent. The MHV sample (103 PFU/mL) was heated at 80 °C for 2 min. At this heat condition, all MHVs were inactivated according to the infectivity assay (data not shown). Then, heat-inactivated MHV was treated with EMA, PMA, or CDDP at its most effective concentration and subjected to RT-qPCR. All samples were tested in triplicate.

Since sodium deoxycholate (SD) pretreatment has been found to improve the performance of capsid integrity treatments (EMA, PMA, and CDPP) to remove inactivated viruses (e.g., AiV) (Canh et al., 2019), the current study also investigated the effect of SD pretreatment on the performance of optimal capsid integrity treatment on inactivated MHV. For this purpose, heat-inactivated MHV samples (at 80 °C for 2 min) were pretreated with 0.1% SD (final concentration) according to a previous study (Canh et al., 2019) and subjected to RT-qPCR with and without optimal capsid integrity treatment (as determined from the previous step). MHV samples without heat treatment (or incubated at 4 °C for 2 min) were used as the control. All samples were tested in triplicate.

2.8. Screening of virus concentration methods

The UF and PEG precipitation methods were evaluated using raw wastewater to determine the suitable virus concentration method for the application of capsid integrity RT-qPCR. Raw wastewater samples (approximately 500 mL) were collected in June 2020 from wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) located in the Greater Tokyo Area in Japan. The raw wastewater had the following water quality parameters: temperature, 22.9 °C; pH, 7.66; turbidity, 58.2 NTU; electrical conductivity, 556 μs/cm; and UV254 absorbance, 0.304 cm−1. The samples were maintained at −20 °C until use.

Raw wastewater samples (100 mL) spiked with MHV (approximately 108 copies/mL) were concentrated using UF or PEG precipitation (as described above) to obtain the final concentrated samples (0.4–1.0 mL). Then, the final concentrated samples were subjected to RT-qPCR and the most effective capsid integrity RT-qPCR (as determined from the previous section). The experiment was performed in triplicate.

2.9. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewaters

2.9.1. Sample collection and concentration

Sixteen raw wastewater samples were collected from six different WWTPs (A, B, C, D, E, and F) in the Greater Tokyo Area in Japan from January 7th to February 25th, 2021. The water samples were frozen at −20 °C until use (1–2 months). The capacity and detailed treatment processes of these WWTPs are shown in Table S1. The general information of COVID-19 epidemic in the Greater Tokyo Area was in the range between 100 and 600 cases per day per 1 million people and more details are shown in the supplemental information.

The most suitable concentration method (determined from the previous section) was used to concentrate the raw wastewater (100 mL) to obtain the final concentrated samples (0.4–1.0 mL). The final concentrated samples were immediately analyzed for SARS-CoV-2 by conventional RT-qPCR and the most effective capsid integrity RT-qPCR (determined from the previous section).

2.9.2. Process controls

The efficiency of the virus concentration process, RNA extraction, and RT-qPCR for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 was evaluated using spiked MHV (whole process control). Briefly, MHV (20 μL, approximately 108 copies/mL) was spiked into raw wastewater samples (100 mL) and Milli-Q water (100 mL) as a control. The MHV spiked samples were incubated at room temperature (20 °C) for 1.5 h before performing the most effective concentration method (as determined in the previous section). The concentrated samples (140 μL) were then subjected to RNA extraction and RT-qPCR detection. The MHV recovery efficiency (whole process control, EMHV) was calculated according the following equation: EMHV (%) = (C/C0) × (1/F) × 100, in which C0 and C are the concentrations of MHV in MilliQ-water sample (without conducting the virus concentration method) and the concentrated sample, respectively. F represents the concentration factor.

The effectiveness of the capsid integrity treatment to eliminate SARS-CoV-2 RNA in water samples was investigated using MNV RNA since MNV has a similar genome structure to SARS-CoV-2 (Positive single-strand RNA). Briefly, free genomes of MNV (1.4 μL, approximately 106 copies/mL) were spiked into the concentrated water samples and MilliQ-water samples as the control and was subsequently subjected to the most effective capsid integrity RT-qPCR (as determined from the previous section). The effectiveness of the capsid integrity treatment was identified based on a comparison between the reduction of MNV RNA in the target water samples and the reduction of MNV RNA in MilliQ-water (control).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effects of different capsid integrity reagents on intact MHV and its free RNA

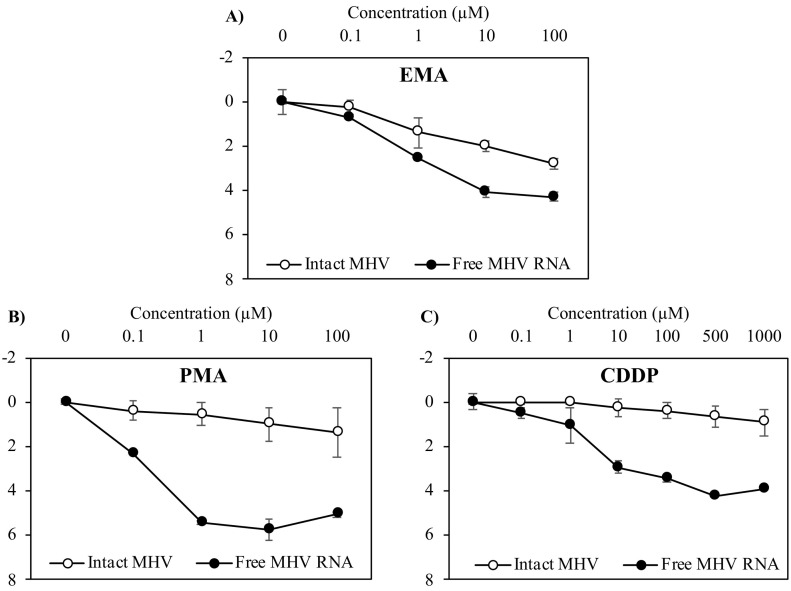

The effects of different capsid integrity reagents (EMA, PMA, and CDDP) at different concentrations on intact MHV and its free RNA are presented in Fig. 1 . As the EMA and PMA concentrations increased from 0.1 to 100 μM, the mean reductions of MHV RNA increased from 0.7 to 4.3 log10 and from 2.4 to 5.1 log10, respectively. CDDP also yielded a mean reduction from 0.5 to 4.2 log10 as its concentration increased from 0.1 to 1,000 μM. These findings indicate that all assessed capsid integrity reagents could reduce the detection signal of MHV RNA by RT-qPCR and were more effective at higher concentrations.

Fig. 1.

Effects of capsid integrity reagents at different concentrations on intact MHV and its free RNA. Log10 reduction of intact MHV and its free RNA after treatment with A) EMA (0, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 μM), B) PMA (0, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 μM), or C) CDDP (0, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, 500, and 1000 μM), followed by RT-qPCR. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (n = 3).

Adverse effects on intact MHV virions were also evaluated. At concentrations of 0.1, 1.0, 10, and 100 μM, EMA showed mean reductions of intact MHV of 0.3, 1.4, 2.0, and 2.8 log10 whereas PMA showed mean reductions of 0.4, 0.5, 0.8, and 1.0 log10, respectively. CDDP had smaller effects on intact MHV since less than a 0.9 log10 reduction was observed even at the highest concentration tested (1,000 μM). The reductions of intact MHV by PMA or CDDP were not significantly different from those of the control (in the absence of PMA or CDDP) (p > 0.05, t-test), indicating that these capsid integrity reagents did not affect the detection of intact MHV by RT-qPCR. This result also implies that the intact MHV stock did not greatly contain free genomes of MHV. However, the reduction of MHV was obtained by EMA at concentrations higher than 0.1 μM (p < 0.05). This result suggests that high concentrations of EMA can affect the detection of intact MHV by RT-qPCR.

Previous studies commonly used EMA and PMA at 100 μM and CDDP at 1,000 μM for performing capsid integrity RT-qPCR on non-enveloped enteric viruses without any effects on intact viral form (Canh et al., 2019; Fraisse et al., 2018). These concentrations also showed no inhibitory effects on RT-qPCR amplification. Therefore, it is possible that enveloped viruses such as MHV are more susceptible to capsid integrity reagents compared with non-enveloped enteric viruses. At high capsid integrity reagent concentrations (particularly EMA > 0.1 μM), the structure of MHV can be altered, which allows capsid integrity reagents to access its genomes so that subsequently these genomes are not detected by RT-qPCR. This result is consistent with a previous study indicating that PMA concentrations higher than 125 μM can cause a loss of infectivity for MS2 bacteriophages (Kim and Ko, 2012).

In the current study, the suitable concentration for each capsid integrity reagent was selected based on two criteria to rule out the effects of damage caused to the viral capsid: 1) the reduction of intact MHV did not differ significantly from that of the control and 2) the mean reduction was less than 0.5 log10. Based on these criteria, EMA and PMA at a concentration of 0.1 μM and CDDP at a concentration of 100 μM were selected and considered to have a negligible effect on intact MHV. At these concentrations, CDDP (100 μM) was able to result in a 3.4 log10 reduction of MHV RNA, which was higher than the 0.5 log10 and 2.4 log10 reductions obtained by EMA (0.1 μM) and PMA (0.1 μM), respectively.

In a previous study, platinum compounds (e.g., CDDP and PtCl4) was also found to remove SARS-CoV-2 RNA in PBS buffer more effectively than monoazide dyes (e.g., EMA, PEMAX and PMAxx) (Cuevas-ferrando et al., 2021). Furthermore, PtCl4 at 2.5 mM was recommended for the application of capsid integrity RT-qPCR because this concentration showed the highest reduction of gamma/heat-inactivated SARS-CoV-2 in fecal suspensions and nasopharyngeal swabs. However, the recommended concentration of PtCl4 was much higher than the optimal CDDP concentration (100 μM) in the current study. It is possible that complex matrices in the tested samples can interact with PtCl4 and reduce the effective concentration of PtCl4. Therefore, the high concentration of PtCl4 is needed to ensure the efficient performance of PtCl4-RT-qPCR.

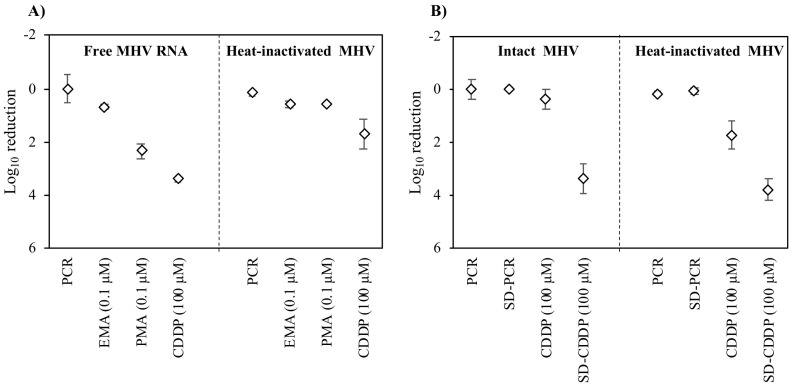

3.2. Determination of the optimal capsid integrity reagent

To determine the most effective capsid integrity reagent among EMA (0.1 μM), PMA (0.1 μM), and CDDP (100 μM), their performances were tested on heat-inactivated MHV (Fig. 2A). CDDP was able to remove heat-inactivated MHV (1.7 log10) more effectively than EMA (0.6 log10) and PMA (0.6 log10). In the previous section, CDDP (100 μM) was also more effective than EMA (0.1 μM) and PMA (0.1 μM) at removing MHV RNA (Fig. 1, Fig. 2A). Therefore, CDDP (100 μM) was considered the most effective among the tested capsid integrity reagents for discrimination of the damaged virus. This finding agrees with our previous study indicating that CDDP was more effective than EMA and PMA in discriminating between infectious and inactivated non-enveloped enteric viruses (e.g., AiV) (Canh et al., 2019).

Fig. 2.

Screening for the optimal capsid integrity reagent. A) Comparison of the abilities of EMA, PMA, and CDDP on the reduction of free MHV RNA and heat-inactivated MHV (80 °C for 2 min). B) Effects of SD on intact and heat-inactivated MHV (80 °C for 2 min). Error bars indicate the standard deviation (n = 3).

Moreover, the effects of SD surfactant on the performance of CDDP treatment were also investigated to improve the discrimination of inactivated MHV. As shown in Fig. 2B, SD surfactant (0.1%) combined with CDDP (100 μM) showed a higher reduction of inactivated MHV (3.8 log10) than CDDP alone (1.7 log10). However, the combination of SD and CDDP was found to greatly reduce the detection of intact MHV (3.4 log10). It is possible that SD surfactant might damage the MHV capsid since surfactants have been found to dissolve the lipid bilayer membrane of enveloped viruses (e.g., influenza virus) (Kawahara et al., 2018). Therefore, surfactants (particularly SD) should not be used in combination with CDDP for capsid integrity RT-qPCR to assess the infectivity of enveloped viruses. This finding is inconsistent with previous studies indicating that surfactants (e.g., SD and Trition X-100) can enhance the performance of capsid integrity RT-qPCR on non-enveloped enteric viruses with no impact on their capsid or infectivity (Canh et al., 2019). It is possible that non-enveloped viruses might not be susceptible to the effects of surfactant since they do not contain a lipid bilayer membrane in their structure.

Based on these results, capsid integrity RT-qPCR with 100 μM CDDP (CDDP-RT-qPCR) was selected as the most effective method and was used for further analyses in this study.

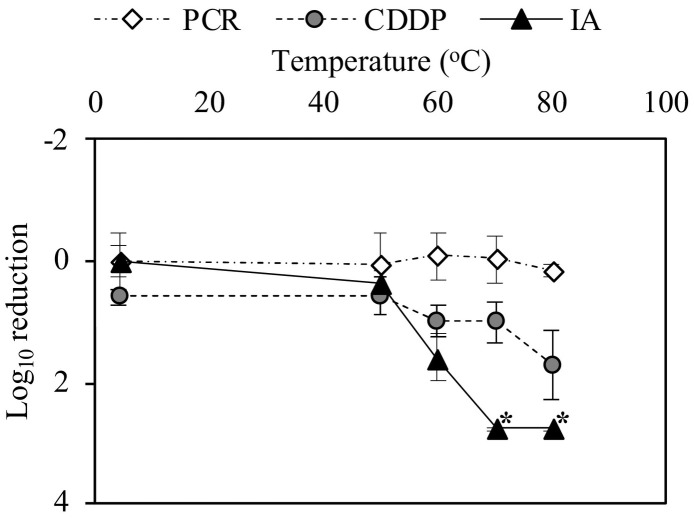

3.3. Performance of capsid integrity RT-qPCR to evaluate MHV inactivation by heat treatment

The performance of capsid integrity RT-qPCR using CDDP (CDDP-RT-qPCR) was compared to that of RT-qPCR alone and the infectivity assay to evaluate MHV inactivation after heat treatment at 50, 60, 70, or 80 °C (Fig. 3 ). Although RT-qPCR alone was unable to reduce MHV at any of the temperatures tested, loss of infectivity was observed at 1.6 log10 at 60 °C and more than 2.8 log10 (below the detection limit) at 70 and 80 °C. This result indicates that RT-qPCR alone was unable to discriminate between infectious and inactivated MHV. By contrast, CDDP-RT-qPCR showed a reduction of 1.0 log10, 1.0 log10, and 1.7 log10 at 60, 70, and 80 °C, respectively, indicating that CDDP-RT-qPCR was more effective in accessing the infectivity of MHV compared with RT-qPCR alone. This result also suggests that CDDP enters heat-inactivated MHV and subsequently blocks the viral genome from being detected by RT-qPCR. However, compared with the infectivity assay, CDDP-RT-qPCR still yielded a lower reduction of MHV, suggesting that CDDP-RT-qPCR did not fully differentiate between infectious and inactivated MHV. This is consistent with previous studies indicating that capsid integrity RT-qPCR overestimated the actual number of infectious viruses when examining non-enveloped enteric viruses after heat, chlorine, and UV treatments (Fuster et al., 2016; Leifels et al., 2015; Prevost et al., 2016; Randazzo et al., 2018). In fact, the loss of capsid integrity was not always correlated with the loss of viral infectivity (Hamza et al., 2011). Therefore, it is possible that viruses can lose their infectivity through alterations on viral capsid structures while still maintaining their capsid integrity to prevent the entry of capsid integrity reagents.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the performance of RT-qPCR alone (PCR), CDDP-RT-qPCR (CDDP), and infectivity assay (IA) to evaluate MHV inactivation at 50, 60, 70, or 80 °C for 2 min. Solid triangles with asterisk symbols indicate the negative results (>2.8 log10). The reduction limit of PCR-based assays and the IA was 4.6 log10 and 2.8 log10, respectively. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (n = 3).

Enveloped viruses such as MHV have an additional lipid bilayer membrane compared with non-enveloped viruses. After inactivation treatment, enveloped viruses might interact with capsid integrity reagents at different efficiencies compared with non-enveloped viruses. In the current study, CDDP-RT-qPCR was able to reduce 3.4 log10 of MHV RNA (maximum capacity) but only 1.7 log 10 of heat-inactivated MHV even at the highest temperature tested (80 °C for 2 min). Compared with our previous studies on enteric viruses (e.g., AiV), CDDP was capable of removing 5.7 log10 of AiV RNA and 4.8 log10 of heat-inactivated AiV (80 °C for 1 min) (Canh et al., 2019, Canh et al., 2020). In other words, CDDP yielded a 0.9 log10 difference in the reduction between inactivated AiV and its free RNA, which was smaller than the 1.7 log10 difference in the reduction between inactivated MHV and its free RNA. Most likely, the penetration of CDDP into the capsid of a non-enveloped virus (AiV) was more effective than that into in an enveloped virus (MHV) at a similar inactivation condition. However, more studies are necessary to accurately compare between enveloped and non-enveloped viruses to investigate the performance of capsid integrity of RT-qPCR at a similar concentration of virus stock and capsid integrity reagents.

3.4. Screening of virus concentration methods for the application of capsid integrity RT-qPCR

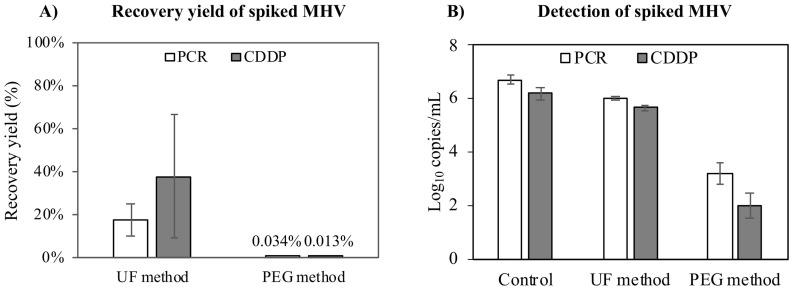

Two virus concentration methods (the UF and PEG methods) were investigated to recover MHV in raw wastewater (Fig. 4 ). The recovery yields were determined by RT-qPCR alone and CDDP-RT-qPCR (the most effective capsid integrity RT-qPCR determined from the previous section) (Fig. 4A). According to RT-qPCR alone, the UF method yielded a MHV recovery of 17.8% ± 7.4%, which was significantly higher than the recovery of 0.034% ± 0.024% obtained by the PEG method. This result agrees with findings from a previous study indicating a greater recovery of φ6 in wastewater samples by the UF method (6.4–35.8%) compared with the PEG method (1.4–3.0%) (Torii et al., 2021). When comparing the effectiveness of different concentration methods for quantifying SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater, LaTurner et al. (2021) also found that the UF method yielded a higher concentration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater concentrates than did the PEG method. However, the recovery of intact viruses or the effects on viral capsids by these concentration methods were not investigated since the previous studies applied only RT-qPCR or droplet digital RT-PCR to quantify viruses. In the current study, when determined by CDDP-RT-qPCR, the recovery yields of the UF method (38.0% ± 28.7%) were also greater than those obtained by the PEG method (0.013% ± 0.015%) (Fig. 4A). These results suggest that the UF method was able to recover intact MHV more effectively than the PEG method. In a previous study, the UF method was also found to recover infective MHV and Pseudomonas phage φ6 more effectively than the PEG method according to the infectivity assay (Ye et al., 2016). Therefore, it is better to apply the UF method for evaluating virus concentration when investigating the infectivity of enveloped viruses in wastewater.

Fig. 4.

Comparison between the UF and PEG methods for concentrating MHV in raw wastewater. A) Recovery yields of MHV determined by RT-qPCR (PCR) and CDDP-RT-qPCR (CDDP). B) Detection of MHV in the concentrated samples determined by PCR and CDDP. The control was MilliQ-water samples in which the virus had not been concentrated. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (n = 3).

Furthermore, for the UF method, the recovery efficiency of MHV determined by conventional RT-qPCR (17.8% ± 7.4%) did not differ significantly from the recovery efficiency of MHV determined by CDDP-RT-qPCR (38.0% ± 28.7%) (Fig. 4A). Additionally, the different levels obtained between RT-qPCR alone and CDDP-RT-qPCR in the samples concentrated by the UF method (0.4 log10) were comparable to those in the control (0.4 log10) (MilliQ-water samples without performing the virus concentration methods) (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that the UF method did not significantly affect the structure of MHV. However, in the samples concentrated by the PEG method, the difference (1.2 log10) between RT-qPCR alone and CDDP-RT-qPCR was significantly greater than that of the control (Fig. 4B). This may have occurred because the structure of MHV was partially destroyed by the PEG method. This finding is consistent with a previous study indicating that the PEG method could affect the infectivity of enveloped viruses. Indeed, Ye et al. (2016) found that the infectivity of MHV was decreased by 2 log10 when MHV was incubated with PEG for 16 h. In this current study, the mixing process of wastewater samples and PEG was conducted for approximately 20 h. Therefore, it is possible that the PEG method in this current study can cause a certain loss of MHV infectivity due to the disruption of PEG on their lipid bilayers (Ye et al., 2016). Besides, in the PEG method, MHV might also be inactivated when incubated in NaCl (1 M) owing to the impact of osmotic lysis (Cordova et al., 2003).

Since the UF method displayed a greater recovery of intact MHV and caused less damage to the MHV capsid than the PEG method, it was selected for concentrating SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater in the following steps of this study.

3.5. Application of capsid integrity RT-qPCR for the selective detection of SARS-COV-2 in wastewater samples

Sixteen raw wastewater samples collected from the Greater Tokyo Area were concentrated using the UF concentration method and were quantified for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-qPCR alone and CDDP-RT-qPCR (Table 1 ). The efficacy of the whole detection processes (including the UF concentration method, RNA extraction, and RT-qPCR amplification) was investigated for all wastewater samples using spiked MHV. The recovery efficiencies were mostly greater than 10%, indicating that the entire detection process was efficient for detecting viruses in the tested wastewater samples. Furthermore, the efficiency of CDDP treatment to eliminate free viral RNA present in wastewater was investigated using MNV RNA. The CDDP treatment was able to remove more than 5.7 log10 of MNV RNA in all concentrated samples, indicating that the CDDP treatment effectively removed free viral genomes present in the concentrated wastewater samples.

Table 1.

Process control and detection of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater by RT-qPCR alone (PCR) and CDDP-RT-qPCR (CDDP).

| Samples |

Process control |

SARS-CoV-2c |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Name | Plant | Recovery of spiked MHVa (%) |

Reduction of MNV RNAb (Log10) |

PCR (copies/L) |

CDDP (copies/L) |

LoD (copies/L) |

| 2021/1/7 | A1 | A | 17% | >6.3 | <LoD | <LoD | 5.0 × 103 |

| 2021/1/13 | A2 | 31% | >6.3 | <LoD | <LoD | 5.9 × 103 | |

| 2021/1/20 | A3 | 42% | >6.3 | <LoD | <LoD | 6.9 × 103 | |

| 2021/1/7 | B1 | B | 37% | >6.3 | 2.3 × 104d | <LoD | 4.9 × 103 |

| 2021/1/13 | B2 | 39% | >6.3 | <LoD | <LoD | 7.4 × 103 | |

| 2021/1/20 | B3 | 40% | 5.8 | <LoD | <LoD | 7.9 × 103 | |

| 2021/2/3 | C1 | C | 41% | >6.3 | 3.0 × 104d | <LoD | 1.0 × 104 |

| 2021/2/10 | C2 | 44% | >6.3 | <LoD | <LoD | 6.8 × 103 | |

| 2021/1/20 | D1 | D | 18% | >6.3 | 6.6 × 104e | 2.2 × 104e | 3.3 × 103 |

| 2021/1/28 | D2 | 25% | 5.7 | <LoD | <LoD | 3.9 × 103 | |

| 2021/2/17 | E1 | E | 10% | >6.3 | <LoD | <LoD | 5.1 × 103 |

| 2021/2/25 | E2 | 7% | >6.3 | <LoD | <LoD | 5.8 × 103 | |

| 2021/2/3 | F1 | F | 13% | >6.3 | 3.3 × 104d | 3.0 × 104d | 5.3 × 103 |

| 2021/2/10 | F2 | 14% | 5.9 | <LoD | <LoD | 5.1 × 103 | |

| 2021/2/17 | F3 | 11% | >6.3 | <LoD | <LoD | 5.8 × 103 | |

| 2021/2/24 | F4 | 5% | 6.0 | 1.4 × 104d | 2.2 × 104d | 5.3 × 103 | |

MHV was used to evaluate the recovery of the whole process control using RT-qPCR.

MNV RNA was used to evaluate the ability of CDDP treatment to eliminate free viral genomes in water samples. The reduction limit was 6.3 log10.

A primer and probe set (CDC_N1) was used to detect SARS-CoV-2.

SARS-CoV-2 was positive in one of two PCR reactions (Ct values: 36.5–39.1).

SARS-CoV-2 was positive in two of two PCR reactions (Ct values: 36.4–37.9).

Of the 16 raw wastewater samples, SARS-CoV-2 was detected in 5 samples (B1, C1, D1, F1, and F4) with concentrations ranging from 2.3 × 103 to 6.6 × 104 copies/L when determined by RT-qPCR alone (Table 1). This result is consistent with previous studies conducted in Japan indicating that the concentration of SARS-CoV-2 was <1.1–4.1 × 104 copies/L or higher than the detection limit (4.0 × 103–8.2 × 104 copies/L) in raw wastewater (Haramoto et al., 2020; Hata et al., 2021; Torii et al., 2021). A higher load of SARS-CoV-2 was also reported in raw wastewater collected in other countries, particularly loads of 1.1–3.2 × 105 copies/L in Spain (Randazzo et al., 2020), 104–106 copies/L in France (Wurtzer et al., 2020b), and 2.6 × 103–2.2 × 106 copies/L in the Netherlands (Medema et al., 2020). This could be due to differences in the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in communities among various countries or the different methodologies applied for virus detection. However, the capsid integrity of SARS-CoV-2 was not assessed in these previous studies because conventional RT-qPCR was applied.

In this current study, among the five samples that were positive for SARS-CoV-2 according to the RT-qPCR analysis, only three samples (D1, F1, and F4) remained positive at concentrations ranging from 2.2 × 104 to 3.0 × 104 copies/L when determined by CDDP-RT-qPCR (Table 1). Therefore, it is possible that SARS-CoV-2 in samples B1 and C1 (which were only positive according to RT-qPCR) had a compromised structure or was completely inactivated. Conversely, SARS-CoV-2 in samples D1, F1, and F4 (positive according to both RT-qPCR and CDDP-RT-qPCR) likely had intact capsids. Although SARS-CoV-2 with an intact capsid in wastewater was detected by CDDP-RT-qPCR, its infectivity was unknown. As discussed in a previous section (Section 3.3), CDDP-RT-qPCR cannot fully distinguish between infectious and inactivated MHV. Indeed, CDDP-RT-qPCR was able to discriminate only 1.7 log10 of inactivated MHV whereas all MHV (>2.8 log10) lost their infectivity at the high temperature (80 °C). Furthermore, the inactivation conditions in natural wastewater might differ from those evaluated in this current study (at high temperatures). In actual conditions, SARS-CoV-2 might lose its infectivity in wastewater at much lower temperatures (such as room temperature). The infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 could also be affected by biological activities or pH levels of wastewater. Therefore, more studies are necessary to accurately determine the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater and to investigate the ability of CDDP-RT-qPCR to discriminate between infectious and inactivated viruses under these inactivation conditions.

Although CDDP-RT-qPCR was unable to determine the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater, this method enhanced the accuracy of determining the probability of the presence of positive SARS-CoV-2 compared with that obtained by RT-qPCR. This finding is in agreement with a previous study suggesting that PMAxx-RT-qPCR could provide a better estimate of the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection through wastewater compared with conventional RT-qPCR when investigating the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater (Wurtzer et al., 2021). Furthermore, in a previous study, quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA) was used to estimate the potential risk of SARS-CoV-2 in natural water bodies (Kumar et al., 2021). In this study, viral RNA copies obtained by conventional RT-qPCR were assumed to reflect the maximum infectious concentration of SARS-CoV-2 as PFUs and were used for the risk assessment. Based on the outcome of our current study, it is possible that the previous study greatly overestimated the risk of SARS-CoV-2. Since the ratio of SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies to the infectious concentration (PFUs) is unknown in environmental waters, the use of SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies determined by CDDP-RT-qPCR for QMRA could provide a more accurate assessment of the potential risk of SARS-CoV-2 than the use of SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies determined by conventional RT-qPCR.

4. Conclusion

Among the capsid integrity reagents (EMA, PMA, and CDDP) tested at different concentrations, 100 μM CDDP was found to be the most suitable for determining viral infectivity since it showed a negligible effect on intact MHV and reduced a higher level of MHV RNA and heat-inactivated MHV. Compared with the PEG method to concentrate MHV in wastewater, the UF method yielded a higher recovery of MHV and caused less damage to the structure of MHV. Thus, the UF method appears to be more suitable for the application of capsid integrity RT-qPCR. The UF concentration method followed by CDDP-RT-qPCR was successfully applied for the selective detection of intact SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater collected in the Greater Tokyo Area. Although CDDP-RT-qPCR was unable to determine the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater, this method could improve the interpretation of positive SARS-CoV-2 results obtained by RT-qPCR.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Vu Duc Canh: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Shotaro Torii: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Midori Yasui: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Shigeru Kyuwa: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Hiroyuki Katayama: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (P20061), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) 20H00259. The authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Editor: Damià Barceló

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148342.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Ahmed W., Angel N., Edson J., Bibby K., Bivins A., O’Brien J.W., Choi P.M., Kitajima M., Simpson S.L., Li J., Tscharke B., Verhagen R., Smith W.J.M., Zaugg J., Dierens L., Hugenholtz P., Thomas K.V., Mueller J.F. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: A proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138,764. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Bertsch P.M., Bibby K., Haramoto E., Hewitt J., Huygens F., Gyawali P., Korajkic A., Riddell S., Sherchan S.P., Simpson S.L., Sirikanchana K., Symonds E.M., Verhagen R., Vasan S.S., Kitajima M., Bivins A. Decay of SARS-CoV-2 and surrogate murine hepatitis virus RNA in untreated wastewater to inform application in wastewater-based epidemiology. Environ. Res. 2020;191:110,092. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Bertsch P.M., Bivins A., Bibby K., Farkas K., Gathercole A., Haramoto E., Gyawali P., Korajkic A., McMinn B.R., Mueller J.F., Simpson S.L., Smith W.J.M., Symonds E.M., Thomas K.V., Verhagen R., Kitajima M. Comparison of virus concentration methods for the RT-qPCR-based recovery of murine hepatitis virus, a surrogate for SARS-CoV-2 from untreated wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;739:139,960. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao P.N., Canh V.D. Environmental Resilience and Transformation in Times of COVID-19. Elsevier Inc.; 2021. Addressing associated risks of COVID-19 infections across water and wastewater service chain in Asia; pp. 103–114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Besselsen D., Wagner A., Loganbill J. Detection of rodent coronaviruses by use of fluorogenic reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction analysis. Comp. Med. 2002;52:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bivins A., Greaves J., Fischer R., Yinda K.C., Ahmed W., Kitajima M., Munster V.J., Bibby K. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in water and wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7:937–942. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco A., Guix S., Fuster N., Fuentes C., Bartolomé R., Cornejo T., Pintó R.M., Bosch A. Norovirus in bottled water associated with gastroenteritis outbreak, Spain, 2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017;23:1531–1534. doi: 10.3201/eid2309.161489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilo L., Oliveira D., Torres-franco A.F., Coelho B., Senra B., Santos S., Azevedo E., Costa M.S., Tulius M., Reis P., Melo M.C., Bicalho R., Martins M., Rossas C. Viability of SARS-CoV-2 in river water and wastewater at different temperatures and solids content. Water Res. 2020;195:117,002. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canh V.D., Kasuga I., Furumai H., Katayama H. Viability RT-qPCR combined with sodium deoxycholate pre-treatment for selective quantification of infectious viruses in drinking water. Food Environ. Virol. 2019;11:40–51. doi: 10.1007/s12560-019-09368-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canh, V.D., Furumai, H., Katayama, H., 2020. Effect of viral genome property on the efficiency of viability (RT-)qPCR. J. Jpn. Soc. Civ. Eng. Ser. G Environ. Res. 76, III_189-III_196. doi: 10.2208/jscejer.76.7_iii_189 [DOI]

- Canh V.D., Torii S., Furumai H., Katayama H. Application of capsid integrity (RT-)qPCR to assessing occurrence of intact viruses in surface water and tap water in Japan. Water Res. 2021;189:116,674. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . Div. Viral Dis. Centers Dis. Control Prev. 2020. 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) real-time rRT-PCR panel primers and probes. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Chen L., Deng Q., Zhang G., Wu K., Ni L., Yang Y., Liu B., Wang W., Wei C., Yang J., Ye G., Cheng Z. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:833–840. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung K.S., Hung I.F.N., Chan P.P.Y., Lung K.C., Tso E., Liu R., Ng Y.Y., Chu M.Y., Chung T.W.H., Tam A.R., Yip C.C.Y., Leung K.H., Fung A.Y.F., Zhang R.R., Lin Y., Cheng H.M., Zhang A.J.X., To K.K.W., Chan K.H., Yuen K.Y., Leung W.K. Gastrointestinal manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection and virus load in fecal samples from a Hong Kong cohort: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:81–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova A., Deserno M., Gelbart W.M., Ben-Shaul A. Osmotic shock and the strength of viral capsids. Biophys. J. 2003;85:70–74. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74455-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coudray-meunier C., Fraisse A., Martin-latil S., Guillier L., Perelle S. Discrimination of infectious hepatitis A virus and rotavirus by combining dyes and surfactants with. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas-ferrando E., Randazzo W., Pérez-cataluña A., Navarro D., Martin-latin S., Díaz-reolid A., Girón-guzmán I., Allende A., Sánchez G. medRix. 2021. Viability RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2: a step forward to solve the infectivity quandary. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson M., Ihrie J. 2019. MPN: Most Probable Number and Other Microbial Enumeration Techniques. [Google Scholar]

- Fraisse A., Niveau F., Hennechart-collette C., Coudray-meunier C., Martin-latil S., Perelle S. International Journal of Food Microbiology Discrimination of infectious and heat-treated norovirus by combining platinum compounds and real-time RT-PCR. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018;269:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster N., Pinto R.M., Fuentes C., Beguiristain N., Bosch A., Guix S. Propidium monoazide RTqPCR assays for the assessment of hepatitis A inactivation and for a better estimation of the health risk of contaminated waters. Water Res. 2016;101:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.05.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbalenya A.E., Baker S.C., Baric R.S., de Groot R.J., Drosten C., Gulyaeva A.A., Haagmans B.L., Lauber C., Leontovich A.M., Neuman B.W., Penzar D., Perlman S., Poon L.L.M., Samborskiy D.V., Sidorov I.A., Sola I., Ziebuhr J. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Latorre L., Ballesteros I., Villacrés-Granda I., Granda M.G., Freire-Paspuel B., Ríos-Touma B. SARS-CoV-2 in river water: implications in low sanitation countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;743:140,832. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza I.A., Jurzik L., Überla K., Wilhelm M. Methods to detect infectious human enteric viruses in environmental water samples. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2011;214:424–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haramoto E., Malla B., Thakali O., Kitajima M. First environmental surveillance for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater and river water in Japan. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;737:140,405. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata A., Hara-Yamamura H., Meuchi Y., Imai S., Honda R. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater in Japan during a COVID-19 outbreak. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;758:143,578. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara T., Akiba I., Sakou M., Sakaguchi T., Taniguchi H. Inactivation of human and avian influenza viruses by potassium oleate of natural soap component through exothermic interaction. PLoS One. 2018;13:1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.Y., Ko G. Using propidium monoazide to distinguish between viable and nonviable bacteria, MS2 and murine norovirus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2012;55:182–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2012.03276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima M., Tohya Y., Matsubara K., Haramoto E., Utagawa E., Katayama H., Ohgaki S. Use of murine norovirus as a novel surrogate to evaluate resistance of human norovirus to free chlorine disinfection in drinking water supply system. Environ. Eng. Res. 2008;45:361–370. doi: 10.11532/proes1992.45.361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima M., Tohya Y., Matsubara K., Haramoto E., Utagawa E., Katayama H. Chlorine inactivation of human norovirus, murine norovirus and poliovirus in drinking water. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010;51:119–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima M., Ahmed W., Bibby K., Carducci A., Gerba C.P., Hamilton K.A., Haramoto E., Rose J.B. SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: state of the knowledge and research needs. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;739:139,076. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M., Patel A.K., Shah A.V., Raval J., Rajpara N., Joshi M., Joshi C.G. First proof of the capability of wastewater surveillance for COVID-19 in India through detection of genetic material of SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;746:141,326. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M., Alamin M., Kuroda K., Dhangar K., Hata A., Yamaguchi H., Honda R. Potential discharge, attenuation and exposure risk of SARS-CoV-2 in natural water bodies receiving treated wastewater. npj Clean Water. 2021;4:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41545-021-00098-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LaTurner Z.W., Zong D.M., Kalvapalle P., Gamas K.R., Terwilliger A., Crosby T., Ali P., Avadhanula V., Santos H.H., Weesner K., Hopkins L., Piedra P.A., Maresso A.W., Stadler L.B. Evaluating recovery, cost, and throughput of different concentration methods for SARS-CoV-2 wastewater-based epidemiology. Water Res. 2021;197:117,043. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leifels M., Jurzik L., Wilhelm M., Hamza I.A. Use of ethidium monoazide and propidium monoazide to determine viral infectivity upon inactivation by heat, UV- exposure and chlorine. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2015;218:686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leifels M., Cheng D., Sozzi E., Shoults D.C., Wuertz S., Mongkolsuk S., Sirikanchana K. Capsid integrity quantitative PCR to determine virus infectivity in environmental and food applications – a systematic review. Water Res. X. 2021;11:100,080. doi: 10.1016/j.wroa.2020.100080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescure F.-X., Bouadma L., Nguyen D., Parisey M., Wicky P.-H., Behillil S., Gaymard A., Bouscambert-Duchamp M., Donati F., Le Hingrat Q., Enouf V., Houhou-Fidouh N., Valette M., Mailles A., Lucet J.-C., Mentre F., Duval X., Descamps D., Malvy D., Timsit J.-F., Lina B., Van-der-Werf S., Yazdanpanah Y. Clinical and virological data of the first cases of COVID-19 in Europe: a case series. Lancet. 2020;20:697–706. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30200-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema G., Heijnen L., Elsinga G., Italiaander R., Brouwer A. Presence of SARS-Coronavirus-2 RNA in sewage and correlation with reported COVID-19 prevalence in the early stage of the epidemic in the Netherlands. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;7:511–516. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister S., Verbyla M.E., Klinger M., Kohn T. Variability in Disinfection Resistance between Currently Circulating Enterovirus B Serotypes and Strains. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52:3696–3705. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b00851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey D., Verma S., Verma P., Mahanty B., Dutta K., Daverey A., Arunachalam K. SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: Challenges for developing countries. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2021;231:113,634. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2020.113634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peccia J., Zulli A., Brackney D.E., Grubaugh N.D., Kaplan E.H., Casanovas-Massana A., Ko A.I., Malik A.A., Wang D., Wang M., Warren J.L., Weinberger D.M., Arnold W., Omer S.B. Measurement of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater tracks community infection dynamics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:1164–1167. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0684-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevost B., Goulet M., Lucas F.S., Joyeux M., Moulin L., Wurtzer S. Viral persistence in surface and drinking water: Suitability of PCR pre-treatment with intercalating dyes. Water Res. 2016;91:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo W., Vasquez-García A., Aznar R., Sánchez G. Viability RT-qPCR to distinguish between HEV and HAV with intact and altered capsids. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo W., Truchado P., Cuevas-Ferrando E., Simón P., Allende A., Sánchez G. SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater anticipated COVID-19 occurrence in a low prevalence area. Water Res. 2020;181:115,942. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimoldi S.G., Stefani F., Gigantiello A., Polesello S., Comandatore F., Mileto D., Maresca M., Longobardi C., Mancon A., Romeri F., Pagani C., Cappelli F., Roscioli C., Moja L., Gismondo M.R., Salerno F. Presence and infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 virus in wastewaters and rivers. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;744:140,911. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangsanont J., Katayama H., Kurisu F., Furumai H. Capsid-damaging effects of UV irradiation as measured by quantitative PCR coupled with ethidium monoazide treatment. Food Environ. Virol. 2014;6:269–275. doi: 10.1007/s12560-014-9162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif S., Ikram A., Khurshid A., Salman M., Mehmood N., Arshad Y., Ahmad J., Angez M., Alam M.M., Rehman L., Mujtaba G., Hussain J., Ali J., Akthar Ri, Malik M.W., Baig Z.I., Rana M.S., Usman M., Ali M.Q., Ahad A., Badar N., Umair M., Tamim S., Tahir F., Ali N. medRxiv. 2020. Detection of SARS-Coronavirus-2 in wastewater, using the existing environmental surveillance network: an epidemiological gateway to an early warning for COVID-19 in communities. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherchan S.P., Shahin S., Ward L.M., Tandukar S., Aw T.G., Schmitz B., Ahmed W., Kitajima M. First detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater in North America: a study in Louisiana, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;743:140,621. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Zhu A., Li H., Zheng K., Zhuang Z., Chen Z., Shi Y., Zhang Z., Chen S. bei, Liu X., Dai J., Li X., Huang S., Huang X., Luo L., Wen L., Zhuo J., Li Yuming, Wang Y., Zhang L., Zhang Y., Li F., Feng L., Chen X., Zhong N., Yang Z., Huang J., Zhao J., Li Yi min. Isolation of infectious SARS-CoV-2 from urine of a COVID-19 patient. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:991–993. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1760144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii S., Itamochi M., Katayama H. Inactivation kinetics of waterborne virus by ozone determined by a continuous quench flow system. Water Res. 2020;186:116,291. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii S., Furumai H., Katayama H. Applicability of polyethylene glycol precipitation followed by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from municipal wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;756:143,067. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trottier J., Darques R., Ait Mouheb N., Partiot E., Bakhache W., Deffieu M.S., Gaudin R. Post-lockdown detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the wastewater of Montpellier, France. One Heal. 2020;10:100,157. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update [WWW Document]. URL. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---13-april-2021

- Wurtzer, S., Marechal, V., J.M., M., Moulin, L., 2020a. Time course quantitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Parisian wastewaters correlates with COVID-19 confirmed cases. medRxiv (2020.04.12.20062679).

- Wurtzer S., Marechal V., Mouchel J.M., Maday Y., Teyssou R., Richard E., Almayrac J.L., Moulin L. Evaluation of lockdown effect on SARS-CoV-2 dynamics through viral genome quantification in waste water, Greater Paris, France, 5 March to 23 April 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.50.2000776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtzer S., Waldman P., Ferrier-Rembert A., Frenois-Veyrat G., Mouchel J.M., Boni M., Maday Y., Marechal V., Moulin L. Several forms of SARS-CoV-2 RNA can be detected in wastewaters: Implication for wastewater-based epidemiology and risk assessment. Water Res. 2021;117:183. doi: 10.1101/2020.12.19.20248508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F., Sun J., Xu Y., Li F., Huang X., Li H., Zhao Jingxian, Huang J., Zhao Jincun. Infectious SARS-CoV-2 in Feces of Patient with Severe COVID-19. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:1920–1922. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.200681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y., Ellenberg R.M., Graham K.E., Wigginton K.R. Survivability, partitioning, and recovery of enveloped viruses in untreated municipal wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:5077–5085. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b00876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Ling H., Huang X., Li J., Li W., Yi C., Zhang T., Jiang Y., He Y., Deng S., Zhang X., Wang X., Liu Y., Li G., Qu J. Potential spreading risks and disinfection challenges of medical wastewater by the presence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral RNA in septic tanks of Fangcang Hospital. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;741:140,445. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Chen C., Zhu S., Shu C., Wang D., Song J., Song Y., Zhen W., Feng Z., Wu G., Xu J., Xu W. China CDC Wkly. Vol. 2. 2020. Isolation of 2019-nCoV from a stool specimen of a laboratory-confirmed case of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pp. 123–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material