Abstract

Complementary therapies are often used during in-vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment. The aim of this study was to determine how UK fertility clinic websites are advertising complementary therapy add-ons. The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority’s (HFEA) ‘Choose a Fertility Clinic’ website was used to identify fertility clinics and their websites. Acupuncture, reflexology, nutritional advice and miscellaneous complementary therapies were examined to determine treatment provision and costs. Treatment claims for acupuncture and reflexology were analysed using an inductive coding approach, and categorized depending on whether they pertained to holistic benefits, physiological benefits or improvements to IVF treatment outcome. At least one complementary therapy was advertised by 17 of 66 (26%) websites. Acupuncture was the most commonly advertised complementary therapy (16/66 clinic websites, 24%), followed by nutritionist services (11/66, 17%), reflexology (10/66, 15%) and other miscellaneous complementary therapies (9/66, 14%). Treatment costs were found to range from less than £50 for individual appointments to hundreds of pounds for treatment packages. Treatments were not always offered in-house at the fertility clinic, but rather patients were referred to an affiliated practitioner. Analysing claims relating to the complementary therapies highlighted that there were differences in the extent to which clinics claimed that complementary therapies benefited IVF, and that information occasionally acknowledged scientific research evidence but did not always present resources in an unbiased manner. Fertility clinic websites should provide accurate information for patients for complementary therapy add-ons. HFEA should add acupuncture and reflexology to their traffic-light system with amber and red ratings, respectively.

Keywords: acupuncture, complementary therapies, IVF, IVF add-ons, reflexology

Introduction

An in-vitro fertilization (IVF) add-on is defined as any technique that is a variation of, or add-on to, the ‘normal’ IVF cycle. This includes laboratory, clinical and complementary treatments (van de Wiel et al., 2020). With increasing demand for IVF, and competition between clinics to attract patients, it is unsurprising that a number of treatment add-ons are marketed to patients (Harper et al., 2017).

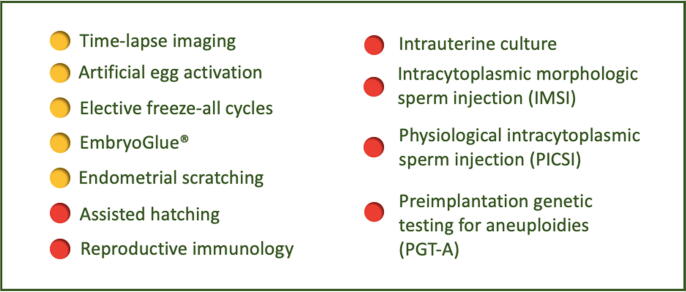

In the UK, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) has established a ‘traffic-light’ system covering some treatment add-ons to provide patients with information in a simple, accessible format. The rating provided is based on evidence-based medicine (EBM) research, mainly randomized controlled trials (HFEA, 2020, HFEA., 2020). The system grants a green rating to add-ons when more than one good-quality randomized controlled trial suggests that the procedure is both beneficial and safe. An amber rating is given to add-ons where more research is needed or there is contradictory evidence, and a red rating is allocated to those add-ons with no evidence of efficacy or safety (HFEA, 2020, HFEA., 2020). The add-ons currently listed on the HFEA website and corresponding traffic-light ratings are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority traffic-light system (HFEA, 2020). None of the add-ons have received a green rating, and over half have been ranked as red, illustrating the controversy of add-on services.

At present, complementary therapies are not included in the HFEA traffic-light add-on list. In 2018, an HFEA patient survey assessed which add-ons were being used by patients. The most commonly used add-on was endometrial scratch, which is included in the HFEA list, and the second most commonly used add-on was acupuncture, used by 26% of patients. Other complementary therapies were also identified by patients in the survey: 11% reported the use of massage, 9% reported the use of meditation and 7% reported that they had accessed ‘other complementary treatment add-ons’. This highlights the need for complementary therapies to receive the same regulatory treatment and EBM testing as laboratory and clinical add-ons (HFEA, 2018).

This study audited UK fertility clinic websites to explore which complementary therapies are being marketed, and their associated cost and treatment claims.

Methods

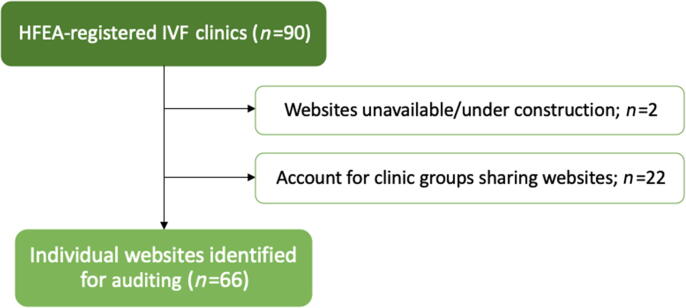

HFEA’s 'Find a Clinic' tool was used to identify all clinics and websites for the audit. The inclusion criteria were that the clinic: (i) offered IVF treatment and (ii) had a website. In cases where the HFEA tool did not provide a website link, an online search using the clinic name and additional information provided by HFEA (such as clinic postcode) was conducted to find the corresponding website.

Clinics that did not offer IVF but offered intrauterine insemination, cryostorage services or other fertility services were excluded. Satellite clinics were also excluded. This resulted in the identification of 90 clinics and 66 individual websites (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

In-vitro fertilization clinic websites identified using the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority’s (HFEA) ‘Find a Clinic’ tool and online search. IVF, in-vitro fertilization.

The clinic websites were audited between 2 and 4 December 2019. If information was not readily available, for example through a menu option relating to complementary therapies, search tools on the website were used with terms such as ‘complementary’, ‘holistic’, ‘acupuncture’ and ‘reflexology’ to see whether information was available on a subpage of the website. Whenever a complementary therapy was mentioned, a screenshot was taken. The price of treatments was recorded if provided. Occasionally, clinic price lists were available in a portable document format, and these were downloaded.

In cases where clinics provided complementary therapy in partnership with, or referred to, an external practitioner, the website of the external practitioner was similarly audited, and information on claims and prices was recorded as screenshots.

Data were grouped at website level to account for shared websites between groups of clinics. For treatment costs, information was recorded from the clinic website if available, or from the external practitioner website if not provided on the clinic website.

For treatment claims, screenshots were sorted into categories with respect to the type of complementary treatment referred to, and an inductive coding approach was used to identify themes in claims made. It was noted whether the claim made was on a clinic website or an external practitioner website.

Data anonymization

Websites and affiliated practitioner details were anonymized. This was achieved by randomizing the order of the 66 websites in Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA), and allocating identifiers ranging from ‘Website 1′ to ‘Website 66′ for use in quotes and treatment pricing information. Following clinic website auditing and initial data collection, a similar process was also performed with respect to external practitioner websites creating identifiers (each titled with respect to the complementary therapy that the practitioner offered).

Results

Analysis showed that although clinics belonging to the same group may have shared a website, complementary therapies were not always offered at all clinic locations. At times, it was unclear which locations offered each add-on. To account for this, and to avoid inaccuracies, data are presented as a percentage of the total number of clinic websites (n = 66) rather than as a percentage of the total number of clinics.

The number of different complementary therapies advertised on fertility clinic websites ranged from zero to four, with the majority (49/66, 74%) not advertising any complementary therapies. At least one complementary therapy was mentioned by 17 of 66 (26%) websites, whilst seven of 66 (11%) websites promoted all four types of complementary therapy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of complementary therapies advertised by clinics.

| Number of complementary therapies | Number of websites (%) n = 66 |

|---|---|

| 0 | 49 (74) |

| 1 | 4 (6) |

| 2 | 4 (6) |

| 3 | 2 (3) |

| 4 | 7 (11) |

| ≥1 | 17 (26) |

When only including websites that advertised one or more complementary therapies, the mean number of therapies advertised was 2.7, illustrating that clinics advertising complementary therapies in general tended to promote more than one type.

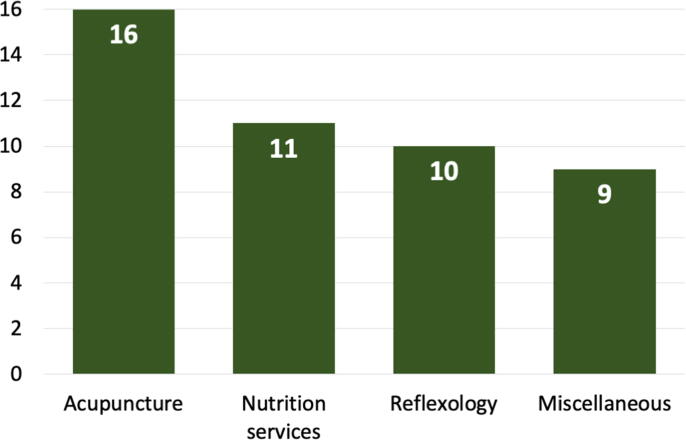

The most commonly advertised complementary therapy was acupuncture (16/66, 24% of clinic websites), followed by nutrition services (11/66, 17% of clinic websites) and reflexology (10/66, 15% of clinic websites). Miscellaneous complementary therapies advertised included massage, yoga, reiki healing, meditation and mindfulness (9/66, 14% of clinic websites) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Number of websites advertising different types of complementary therapies.

Treatment providers

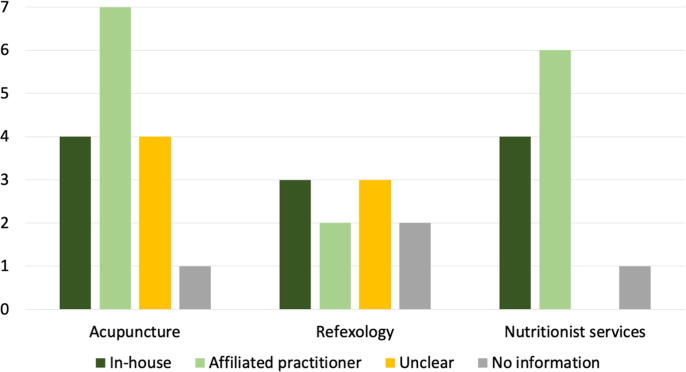

A number of fertility clinic websites referred patients to affiliated practitioner websites, as follows: acupuncture, 15; reflexology, nine; nutritionist services, six; and other/miscellaneous complementary therapies, seven. Some clinics were linked to more than one affiliated practitioner; therefore, numbers for clinics referring to affiliated practitioners and affiliated practitioner websites are not equal. For acupuncture, one fertility clinic promoted a network of ‘preferred providers’ including a total of 30 acupuncture practitioners. However, the clinic highlighted that these practitioners were in no way officially affiliated with them. For this reason, although the clinic was classed as advertising acupuncture and the treatment provider was classed as an ‘affiliated practitioner’, these 30 network websites were not included in the audit study as the link between them and the fertility clinic was not as clear cut. There was also some overlap in affiliated practitioners referred to by different clinics even when they did not belong to the same group.

Forty-four percent of clinics provided acupuncture in-house (7/16 websites), compared with 33% (3/10 websites) for reflexology, and 55% (6/11 websites) for nutritionist services.

In some cases, information was unclear regarding which party was responsible for providing treatment, and occasionally information provided regarding a complementary therapy was vague (e.g. stated its general usefulness, but with no further information regarding how treatment may be offered). In these cases, the information was recorded as ‘no information’ instead of ‘unclear’. Treatment provider data are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Treatment provider information for acupuncture, reflexology and nutritionist services.

Cost of complementary therapies

Acupuncture

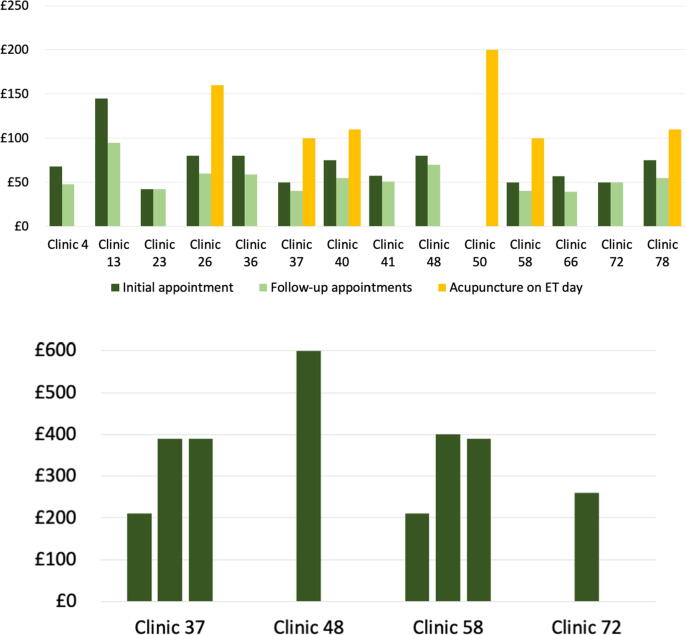

The costs of complementary therapies often differed between initial and follow-up appointments. For acupuncture, fertility- or IVF-specific treatment packages were available (n = 8 packages, advertised by four clinics). Treatment prices were not available online for three of the 17 clinics offering acupuncture.

The costs of acupuncture treatments per clinic are illustrated in Fig. 5. Eleven clinics offered acupuncture on the basis of an initial appointment costing more than follow-up appointments. The median costs of initial and follow-up acupuncture appointments were £68 [interquartile range (IQR) £50–80] and £51 (IQR £42–59), respectively. On average, the cost of acupuncture on the day of embryo transfer was higher (median cost £100, IQR £103–148), although some of these prices included two treatments (one before and one after embryo transfer). Some clinics also charged higher prices for weekend or evening appointments. The prices of packages offered ranged from £200 to £600 (median cost £290, IQR £248–393). Some clinics and affiliated practitioners also offered more than one type of package. The IQR illustrates the range of costs and represents the range for the middle 50% of data.

Fig. 5.

Acupuncture costs. Upper panel: Cost of initial, follow-up and embryo transfer (ET) day appointments. Lower panel: Cost of acupuncture packages. Each column represents the cost of a single package. Clinics 37 and 58 offered more than one package.

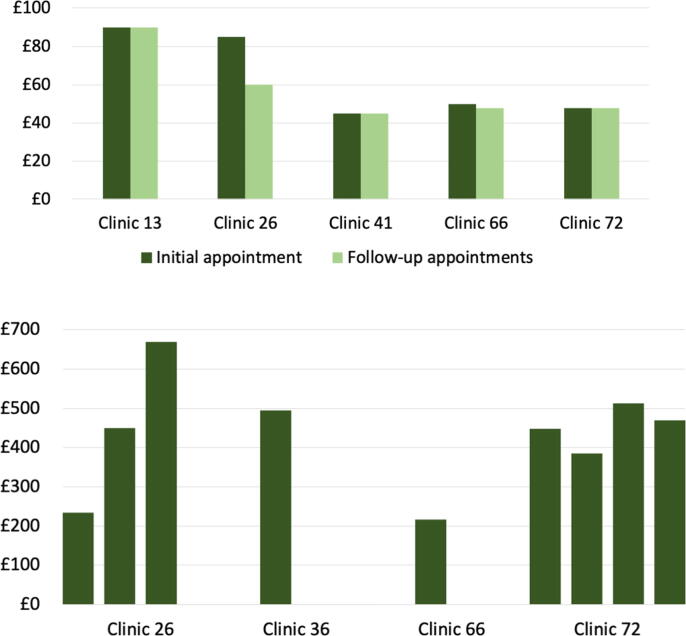

Reflexology

Reflexology appeared to be available more often as a treatment package, although this trend was largely facilitated by two specific external practitioners offering multiple different types of fertility reflexology treatment courses (Fig. 6). No pricing information was available for four of the 10 clinics advertising reflexology. Similarly to acupuncture, the cost of an initial appointment was sometimes more expensive than follow-up appointments [median £50 (IQR £48–85) versus mean £48 (IQR £48–60) for initial and follow-up appointments, respectively]. The median cost of treatment packages was £450 (IQR £386–495).

Fig. 6.

Reflexology costs. Upper panel: Cost of initial and follow-up reflexology appointments during in-vitro fertilization. Lower panel: Cost of reflexology treatment packages. Each column represents the cost of a single package. Clinics 26 and 72 offered more than one package.

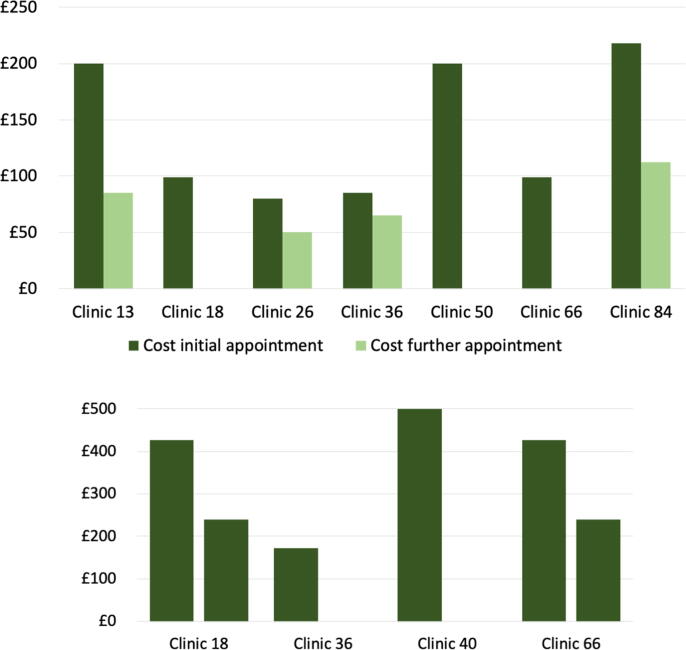

Nutritionist services

Price information for nutritionist services was available for eight of the 11 clinics advertising the service. The median cost of an initial appointment was £99 (IQR £92–200) and the median cost of a follow-up appointment was £75 (IQR £61–92) (Fig. 7). Packages were offered by two clinics. One clinic (Clinic 40) only advertised nutritionist services as a package. The median cost of a nutrition package treatment was £240 (IQR £223–305). Of the three main complementary services assessed, nutritionist services were, on average, more expensive than acupuncture and reflexology.

Fig. 7.

Nutritionist costs. Upper panel: Cost of initial and follow-up nutritionist appointments. Lower panel: Cost of nutritionist service packages. Each column represents the cost of a single package. Clinics 18 and 66 were partnered with the same affiliated practitioner, and both offered two packages costing £240 and £427.

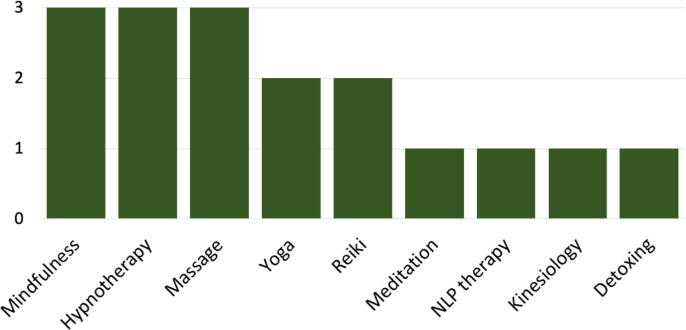

Miscellaneous complementary therapies and example costs

Other complementary therapies identified and the numbers of clinics offering them are illustrated in Fig. 8. Very few clinics quoted the cost of these treatments, but some examples are as follows: mindfulness course, £220; hypnotherapy, £70; Reiki, £40; meditation, £133; and neuro-linguistic programming therapy, £95.

Fig. 8.

Complementary therapies other than acupuncture, reflexology and nutritionist services advertised by clinics. NLP, neuro-linguistic programming.

Treatment claims

Only acupuncture and reflexology treatment claims were analysed. Nutritionist services and miscellaneous complementary therapies were too heterogeneous to obtain any useful information. The major themes were claims related to: (i) holistic wellbeing; (ii) physiological benefits; (iii) IVF outcomes; and (iv) other claims entailing themes such as treatment safety or protocols used.

Acupuncture

Holistic wellbeing

Holistic benefits were mentioned by both clinic websites (9/16, 56%) and external practitioner websites (12/15, 80%). Improved relaxation and de-stressing were the most common phrasing, although some clinic websites also highlighted the stress and emotional burden specifically associated with infertility and treatment, and suggested that acupuncture could help ‘cope with the process’ (Clinic 72) and that stress is ‘a big factor in sub fertility issues’ (Affiliated Acupuncture Provider 1). Benefits to sleep, ‘balance’ and anxiety were also mentioned by both clinics and affiliated practitioners.

Physiological benefits

Website claims regarding the physiological benefits of acupuncture are listed in Table 2. Clinic 26, for example, stated that acupuncture ‘can help decrease the effects of…fertility issues such as endometriosis, ovulation issues, menstrual cycle irregularities and recurrent miscarriages’. Other physiological claims suggested that acupuncture could ‘improve ovarian function to produce higher quality eggs’ (Clinic 1) and ‘increase blood flow to reproductive organs, balance hormone levels [and] regulate the menstrual cycle’ (Clinic 36). Both clinics and affiliated practitioners claimed that acupuncture may ‘improve sperm count, motility, and morphology, and reduce sperm DNA fragmentation’ (Clinic 40) and ‘[improve] delivery of nutrients to developing sperm promoting optimal sperm vitality (Affiliated Acupuncture Provider 1).

Table 2.

Acupuncture claims related to physiological benefits.

| Claim made | Number of clinic websites (%) n = 16 |

Number of affiliated practitioner websites (%) n = 15 |

|---|---|---|

| Improved blood flow to reproductive organs | 11 (69) | 5 (33) |

| Regulation of reproductive hormones | 9 (56) | 4 (27) |

| Improved endometrial/uterine conditions | 7 (44) | 11 (73) |

| Improved ovarian function/more or better-quality eggs | 6 (34) | 3 (20) |

| Improved sperm parameters | 6 (34) | 3 (20) |

| Help with other gynaecological conditions (e.g. PCOS, endometriosis) | 5 (31) | 4 (27) |

| Regulation of menstrual cycle | 4 (25) | 4 (27) |

| Aid to pregnancy symptoms (nausea, breech, pain) | 4 (25) | 1 (7) |

| Immune system benefits | 4 (25) | 1 (7) |

| Reduced ovarian contractions following embryo transfer | 3 (19) | 0 (0) |

| Reduced chances of ectopic pregnancy | 0 (0) | 1 (7) |

PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome.

IVF outcome

The claims regarding IVF outcome are listed in Table 3. One affiliated practitioner website directly stated that ‘[r]esearch shows acupuncture improves implantation rates by as much as 60%’ (Affiliated Acupuncture Provider 12). One clinic and their related affiliated practitioner website suggested that acupuncture could ‘significantly increase the chance of implantation and full-term pregnancy’ (Clinic 58 and Affiliated Acupuncture Provider 16).

Table 3.

Acupuncture claims related to in-vitro fertilization outcome.

| Claim made | Number of clinic websites (%) n = 16 |

Number of affiliated practitioner websites (%) n = 15 |

|---|---|---|

| Improved implantation | 5 (31) | 4 (27) |

| Vague wording of ‘success’ or ‘positive outcome’ | 4(25) | 3 (20) |

| Decreased chance of miscarriage | 3 (19) | 2 (13) |

| Increased chances of full-term pregnancy | 1 (6) | 1 (7) |

| ‘Increased chances of getting pregnant and having a baby’ | 0 (0) | 1 (7) |

| Improved live birth rates | 0 (0) | 1 (7) |

| Increased chances of a successful pregnancy | 0 (0) | 1 (7) |

Other claims

One of the most common other claims was the promotion of fertility-specific acupuncture protocols or emphasizing specialist training or certification in the field of acupuncture in infertility. This was more common on affiliated practitioner websites (12/15, 80%) than clinic websites (4/16, 25%). Claims included, for example, mentioning that treatment was provided ‘alongside the medical team at [clinic name redacted] fertility clinic’ (Affiliated Acupuncture Provider 4), or that practitioners have completed ‘integrated postgraduate-level training in gynaecology, with a specific emphasis on training to support assisted protocols’ (Affiliated Acupuncture Provider 3). Another affiliated practitioner also highlighted that they perform ‘over 3000 sessions of fertility-focused treatments each year’ and that they ‘update…methods in line with recent research’ (Affiliated Acupuncture Provider 14). Two providers also mentioned the ‘Paulus protocol’, with one citing the improved success rate found in the paper published in 2003 (Paulus et al., 2003) (Affiliated Acupuncture Providers 7 and 10).

Only a few websites stated that studies had shown improvements, or referenced specific studies (3/16 clinic websites, 4/15 affiliated practitioner websites). The papers referenced included, for example, Ho et al. (2009) and Paulus et al. (2009). The role of qualified acupuncturists was emphasized, with Clinic 37 stating that ‘acupuncture is a safe therapy when given by qualified acupuncturists’ and ‘[a]dverse effects are rare’. Clinic 50 stressed that qualified acupuncturists complete ‘at least 3600 hours of training at degree level’. Interestingly, the use of traditional Chinese medicine terminology such as ‘qi’ and ‘meridian channels’ was more common on clinic websites (4/16) than affiliated practitioner websites (2/15). The language used often aimed to communicate the historical nature of acupuncture, with Clinic 26 stating that acupuncture had ‘originated from China over 2000 years ago’, whilst Clinic 36 stated that acupuncture was discovered over 5000 years ago as a means of treating ‘the whole person – body, mind and spirit’.

The evidence of using acupuncture in IVF was said to be inconclusive by two clinics and two affiliated practitioner websites. Clinic 4 stated that ‘there is some medical evidence… [but] further studies are needed to understand exactly why’, whilst Clinic 13 advised patients to ‘treat research data as guidance only’ and highlighted the importance of trust in the ‘wide-ranging medical experience [of practitioners]’ Table 4.

Table 4.

Other acupuncture claims.

| Claim made | Number of clinic websites (%) n = 16 |

Number of affiliated practitioner websites (%) n = 15 |

|---|---|---|

| Specialist ‘fertility acupuncture’ protocols or training/certification | 4 (25) | 12 (80) |

| Say studies have shown improvements or references to specific studies | 3 (19) | 4 (27) |

| Use TCM terminology, magical/fantastical thinking | 4 (25) | 2 (13) |

| Reduced IVF medication side effects | 3 (19) | 3 (20) |

| Treatment is safe | 4 (25) | 1 (7) |

| Say evidence is inconclusive or insufficient | 2 (13) | 2 (13) |

| Improved response to IVF drugs | 1 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Benefits to relationship/sex life | 1 (6) | 0 (0) |

TCM, traditional Chinese medicine; IVF, in-vitro fertilization.

Reflexology claims

Holistic wellbeing

The feasibility of reflexology as a tool to help with general wellbeing and reduce stress was claimed by both clinic websites (7/10, 70%) and affiliated practitioner websites (7/9, 78%). Clinic 13 stated that ‘there is evidence that reflexology can have a positive effect on quality of life and reduce both stress and anxiety – which is key for fertility’, while Clinic 41 stated that reflexology could improve sleep. Improvements to holistic wellbeing were also said to be the result of ‘stimulation of the body’s own healing processes’ (Clinic 40). One clinic website also highlighted that ‘reflexology does not aim to diagnose or cure conditions but instead works on a holistic basis alongside other medical treatments to restore the body to its natural balance’ (Clinic 48).

Physiological benefits

The most common physiological benefit claim related to reflexology was that treatment could regulate hormonal imbalances (Table 5). Clinic 36 stated that ‘many different disorders, such as hormonal imbalances…have been successfully treated’, while Clinic 26 claimed reflexology to specifically ‘improve hormonal balance in pregnancy’. Interestingly, the term ‘balance’ was used by all websites but one. One affiliated practitioner (Affiliated Reflexology Provider 8) claimed specifically that their chosen ‘reflexology technique…works on all the endocrine glands and the hormones they produce’.

Table 5.

Claims regarding physiological benefits of reflexology.

| Claim made | Number of clinic websites (%) n = 10 |

Number of affiliated practitioner websites (%) n = 9 |

|---|---|---|

| Hormonal imbalance/regulation | 2 (20) | 4 (44) |

| Pregnancy-related claims (e.g. ‘healing’ processes during pregnancy, hormones, maintaining healthy pregnancy, term delivery) | 4 (40) | 2 (22) |

| Menstrual cycle regulation | 2 (20) | 3 (33) |

| Improvements to underlying conditions (e.g. PCOS, fibroids) | 2 (20) | 3 (33) |

| Blood circulation | 1 (10) | 2 (22) |

| Immune system benefits | 1 (10) | 1 (11) |

| Improvements to sperm parameters | 0 (0) | 2 (22) |

| Lower blood pressure | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

| IVF drug protocol efficacy improved and fewer side effects | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Ovulation | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Improved function of reproductive organs | 0 (0) | 1 (11) |

PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; IVF, in-vitro fertilization.

Improvements to menstrual cycle regulation were claimed by both clinic websites (2/10, 20%) and affiliated practitioner websites (3/9, 33%). For example, Clinic 26 stated that reflexology could ‘improve cycle irregularities’, and Clinic 66 stated that reflexology can ‘help to regulate periods and ovulation’. Claims regarding the ability of reflexology to aid with underlying conditions were made by two clinic websites and three affiliated practitioners. Curiously, the claim made by the two fertility clinics (Clinics 36 and 78) was identical [‘Specifically, [reflexology] may help with many of the medical conditions associated with fertility issues, such as endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), fibroids and unexplained fertility’] even though no relationship, such as belonging to the same group or sharing an affiliated practitioner, existed between them. Mentions of reflexology treating endometriosis, PCOS and fibroids were also common on affiliated practitioner websites, and Affiliated Reflexology Provider 6 stated that treatment could also prevent underlying conditions experienced by men.

IVF outcome

Claims regarding the effects of reflexology on IVF treatment success were vaguer than in the case of acupuncture (Table 6). No clinic websites said that reflexology was effective with respect to infertility, and even the affiliated practitioner claims were ambiguous. Affiliated Reflexology Providers 1, 6 and 8 simply stated that reflexology was ‘non-intrusive yet extremely effective’, ‘shown to be an effective treatment’ and ‘personal, holistic and effective’, respectively.

Table 6.

Claims related to reflexology and infertility treatment success.

| Claim made | Number of clinic websites (%) n = 10 |

Number of affiliated practitioner websites (%) n = 9 |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment is effective | 0 (0) | 3 (33) |

| Support IVF/ICSI | 1 (10) | 1 (11) |

| Encourage natural conception | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

IVF, in-vitro fertilization; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

One clinic website (Clinic 26) stated that reflexology treatment ‘may support assisted conception’, while Affiliated Reflexology Provider 5 highlighted that reflexology can support patients at different stages of their fertility journey, be it ‘at the stage of wanting a baby or trying to conceive, before during and after IVF’. The only direct claim regarding success was made by Clinic 26, which stated that reflexology ‘may encourage natural conception’.

Other claims

In general, less information tended to be available on websites regarding reflexology than acupuncture (Table 7). Specialist protocols, such as Reproreflexology, or training were mentioned on both clinic websites (3/10, 30%) and affiliated practitioner websites (4/9, 44%). Affiliated Reflexology Provider 8 also advertised their own ‘[Clinic name redacted] conception method’ involving bespoke tailoring to clients’ needs. Affiliated Reflexology Provider 3 highlighted that many of their staff had first-hand experience with the challenges of infertility, and emphasized the role of understanding this in their treatment approach.

Table 7.

Other reflexology claims.

| Claim made | Number of clinic websites (%) n = 10 |

Number of affiliated practitioner websites (%) n = 9 |

|---|---|---|

| Specialist protocols or training | 3 (30) | 4 (44) |

| State that reflexology cannot be claimed to cure or treat/ambiguity | 2 (20) | 2 (22) |

| State there are studies that have shown the benefit of reflexology | 1 (10) | 1 (11) |

| References to news articles/patient testimonies | 1 (10) | 1 (11) |

| Disclaimer that information is not medical advice | 0 (0) | 1 (11) |

Regarding evidence for the use of reflexology treatment, Clinic 36 stated that no studies have succeeded in demonstrating the benefits of reflexology to fertility and also cited two papers, and Clinic 48 emphasized that the role of reflexology is not to ‘diagnose or cure conditions’. On the other hand, affiliated practitioners (2/9, 22%) approached the topic slightly differently, stating, for example, that despite the lack of evidence, ‘many couples have found it an effective treatment on their journey to having a baby’ (Affiliated Reflexology Provider 6). This was similar in tone to one clinic (Clinic 73) which provided an emotional patient testimony of success, and one affiliated practitioner (Affiliated Reflexology Provider 6) which provided a link to emotional newspaper article success stories of patients who had achieved success after incorporating reflexology into their treatment programmes.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess complementary therapy IVF add-ons. We found that a range of complementary therapies, including acupuncture, reflexology, nutritionist services, mindfulness, hypnotherapy, massage, yoga, reiki healing, meditation, neuro-linguistic programming therapy, kinesiology and detoxing, are advertised by fertility clinics and are often accompanied by claims that they will improve IVF outcome.

One of the unique factors for complementary therapies illustrated in this study was that treatment was not always offered directly by or at the fertility clinic. Some clinics offered treatment in-house, some had affiliated practitioners who offered the treatment in-house as well as at their own clinic, and some were totally external.

Although this study found that clinics advertising complementary therapies were in the minority, and complementary therapies were not offered at the same level as laboratory or clinical add-ons (van de Wiel et al., 2020), the HFEA patient survey found that a significant proportion of patients incorporate complementary therapies into their IVF journey (HFEA, 2018). There are two possible reasons for this observed discrepancy. Firstly, UK fertility clinics differ in size, with some clinics initiating over 1000 cycles per year whereas some smaller clinics may only initiate a few hundred (HFEA, 2018, HFEA, 2020). Thus, if a larger clinic offers a complementary therapy add-on, a greater number of their patients are likely to take up this service, resulting in the number of clinics not being directly proportionate with the number of patients using the treatment. Secondly, it is possible that patients who were very proactively involved in their fertility journey and took all possible steps, such as incorporating complementary therapies, may have been more invested in responding to the HFEA survey, resulting in biased data. Although counterintuitive in the context of clinics competing to attract patients with successful advertising, it is also possible that promotion of complementary therapy to patients may happen in a non-overt way, behind clinic doors on a word-of-mouth basis. Therefore, future research could benefit from direct assessment of patients’ expectations, experiences and attitudes.

Cost of complementary therapy add-ons

IVF treatment is expensive, and although cost is rarely the main reason for treatment discontinuation, it contributes to the stress experienced by patients in general (Cousineau and Domar, 2006, Chauhan et al., 2020). In addition, limited National Health Service funding is driving people to access treatment in the private sector, and add-on services further complicate the financial aspects of IVF treatment (Harper et al., 2017). The HFEA code of practice outlines that patients should be provided with a personalized cost plan for all treatments, along with fair information of add-on success. However, the translation of this guideline into practice is poorly understood, particularly with respect to add-on services.

Initial appointments tended to be more expensive than follow-up appointments. The general pricing for complementary therapy treatments ranged from less than £50 for individual appointments to specific personalized treatment packages with large price tags exceeding £500. Considering the standard cost of IVF treatment of at least £3348 per cycle (Lay, 2018), adding a single acupuncture appointment would not have a major impact on the total price, but excessively priced treatment packages could easily further increase the financial burden experienced by patients.

Although it may be tempting to justify the pricing of add-on treatments as simply an addition to already expensive assisted reproductive technology treatment, the context and promise with which the add-on treatment is offered must also be considered. If a patient is spending money on a treatment, no matter how small the sum, it should be ensured that expectations of treatment success are supported by evidence in order to ensure satisfaction from a customer- and patient-rights perspective. This study found that practitioners occasionally offered a ‘fertility-specific’ treatment at a higher cost, without it being obvious that the treatment differed from the standard one in any other way than the type of patient to which it was administered. For example, Affiliated Acupuncture Provider 9 provided both standard acupuncture and fertility acupuncture, with the latter at nearly 1.5 times the cost. This can be considered to be representative of a larger trend, where fertility treatment has, in some ways, become depicted as a luxury item in the mainstream media.

Practitioner certification

In the UK, there is no legal regulation surrounding who can provide complementary therapies (National Health Service, 2019). The British Acupuncture Council maintains a list of accredited practitioners (British Acupuncture Council, 2016), although it is important to note that this accreditation is in no way as exhaustive as that required for Western medicine practitioners. For reflexology, there is a voluntary register for practitioners (Association of Reflexologists, 2019), but again this is not mandatory or regulated, and it could be argued that it almost represents a sense of quasi-medicalization that could be misleading for patients.

Claims

Claims for nutritional advice and miscellaneous therapies were not investigated as they were too heterogeneous. For example, nutritionist advice could range from information about a healthy diet to recommendation of ‘fertility’ supplements.

The most common claim for acupuncture is that it will improve holistic wellbeing. Clearly, this is a subjective outcome and therefore difficult to measure. However, a recent randomized controlled trial assessed stress levels and found that acupuncture seemed to reduce anxiety significantly compared with placebo (Smith et al., 2018).

Claims concerning IVF outcome tended to be very circumspect when mentioning success in terms such as live birth rate (LBR), and focused instead on less tangible outcomes such as ‘improved implantation’ or other vague wordings of success. It should be considered whether patients approaching information from a lay perspective are able to understand the significance of, for example, reporting improved LBR rather than improved implantation or other ambiguous success measures. In our view, acupuncture should be rated amber by HFEA, based on the inconsistency of evidence found in meta-analyses (e.g. El-Toukhy et al., 2008, Cheong et al., 2013, Xie et al., 2019). A green rating would not be correct, as there are significant inconsistencies in the quality of different studies. Affiliated Acupuncture Provider 7 went as far as referencing nine different studies suggesting an improvement due to acupuncture, but failed to mention any of the studies that suggested no positive effects. From the perspective of a patient accessing this information, it could easily be seen as manipulative: presenting credible scientific sources 'sells' the treatment, but is not unbiased because studies not favouring acupuncture were left unmentioned.

For physiological effects, the claims made ranged from improved blood flow and improved ovarian function and egg quality to factors such as regulation of menstrual cycle and improved symptoms during pregnancy and birth. Concerning improved blood flow, Ho (2009) showed that acupuncture, in general, is able to achieve this. Other studies have found that acupuncture is able to affect the apoptosis rates of granulosa cells in the ovary (Kusuma et al., 2019). For pregnancy symptoms, acupuncture has not been shown to have an impact; for example, breech presentation at term (Sananes et al., 2016).

For reflexology, there are no meta-analyses to compare website claims. Due to the lack of studies, it should be rated red by HFEA. No clinic websites stated that reflexology was ‘effective’ for anything. The website for Clinic 26 stated that reflexology could aid with ‘natural conception’, which seemed somewhat insensitive for the website of an infertility clinic. The Association of Reproductive Reflexologists (2020) confidently states on its website that ‘[reflexology] is one of the most effective forms of integrated medicine using results from medical testing to measure improvements’ without providing any external source materials. This website, as well as some reflexology and acupuncture sites, also relied heavily on patient testimonies as evidence. The problem with this approach is similar to those outlined above with respect to reporting the effects of acupuncture on IVF success. If a patient does not have knowledge of the true requirements underlying scientific research, for example, these testimonies being coined ‘evidence’ by an established treatment provider may be misleading.

Holistic claims suggesting that reflexology could aid aspects such as sleep, anxiety and relaxation are not necessarily unjustified. For example, studies in patients with cancer have shown that reflexology helped patients to cope mentally with their disease, and to help with sleep and anxiety (Wright et al., 2002). However, claims regarding the physiological benefits of reflexology must be interpreted carefully. For example, suggesting that reflexology could improve hormonal balance, benefit the immune system or aid with underlying chronic conditions such as endometriosis or PCOS seem erroneous.

The HFEA code of conduct requires clinics to provide treatments fairly, and the requirement of honest, unbiased information also extends to clinic websites (HFEA, 2019, HFEA., 2019). This study has shown that some of the information on clinic websites aligns with research evidence, but issues remain with vague wording and limited attention to ambiguity in the research evidence. The situation is also further complicated by clinics referring to (and thus, in a way, officially endorsing) affiliated non-medical practitioners. Overall, the quality of information online could be improved by regular audits by HFEA, with consequences for clinics found to be acting against the code of conduct.

The other authority in the UK that could have an impact on treatment provision is the Competition and Markets Authority, who have recently stated that they have ‘concerns about possible mis-selling of…add-on treatments’, and are therefore in the process of producing a guide for clinics as there is currently no official consumer protection law specific to the IVF sector (Competition and Markets Authority, 2020). Developing legal frameworks for patient protection in assisted reproductive technology should be a priority; there are insufficient consequences if current recommendations are not met, enabling clinics to act as they wish.

With complementary therapies having their roots in traditional Chinese medicine or in foundations pertaining to personal beliefs, the challenge of merging the narratives of the scientific community with personal philosophies must be addressed. Ultimately, patient welfare must not be compromised as a result of excessive competition and financial gain. It must also be remembered that irrespective of biomedical perspectives, holistic wellbeing can serve to remind those seeing treatment that their role as a sick patient, brought about by a diagnosis of infertility, covers more than faulty physiological functions and laboratory protocols. Although achieving this balance of holistic wellbeing and scientific evidence may be demanding, it should remain the gold-standard ambition of healthcare providers and policy makers alike to ensure integrity and fairness of all treatments provided.

Conclusion

This study aimed to elucidate the implications of not including popular complementary therapies, such as acupuncture and reflexology, in the HFEA traffic-light system. The evidence presented suggests that misleading advertising and high costs risk compromising patient welfare and consumer rights. Should HFEA be more stringent in its regulation of these complementary therapies, clinics must accept that any treatments they wish to offer, or be affiliated with, should adhere to EBM principles. This could cause challenges for clinics attempting to differentiate themselves when competing for patients, but would ensure that all treatments are provided in line with protecting the integrity of biomedical research evidence, and without the risk of sharing misinformation for the sake of financial gain.

Declaration

The author reports no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

Biography

Julia Stein has completed the MRes in Reproductive Science and Women’s Health at the Institute for Women’s Health, University College London (UK) following her interest in in-vitro fertilization and fair treatment provision. She is currently working for a value consultancy company specializing in clinical trials research and development.

References

- Association of Reflexologists, 2019. Reflexology regulation. Available at https://www.aor.org.uk/reflexology-regulation/ [Accessed 12 September 2020]

- Association of Reproductive Reflexologists, 2020. Success stories. Available at https://reproductivereflexologists.org/success-stories/ [Accessed 13 September 2020]

- British Acupuncture Council, 2016. Independent Accreditation Available at https://www.acupuncture.org.uk/public-content/about-the-bacc/3683-independent-accreditation.html [Accessed 14 September 2020]

- Chauhan, D, Jackson, E., Harper, J., 2020. Childless by circumstance – the fertility experiences of women who wanted children, RBM Society, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cheong, Y.C., Dix, S., Hung Yu Ng, E., Ledger, W.L., Farquhar, C., 2013. Acupuncture and assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013(7), CD006920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Competition and Markets Authority, 2020. CMA to issue consumer law guidelines for the IVF sector. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/cma-to-issue-consumer-law-guidelines-for-the-ivf-sector [Accessed 26 March 2020]

- Cousineau T.M., Domar A.D. Psychological impact of infertility. Best Practice Research: Clinical Obstetris & Gynaecology. 2006;21(2):293–308. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Toukhy T., Sunkara S.K., Khairy M., Dyer R., Khalaf Y., Coomarasamy A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of acupuncture in in vitro fertilisation. BJOG. 2008;115(10):1203–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper J., Jackson E., Sermon K., Aitken R.J., Harbottle S., Mocanu E., Hardarson T., Mathur R., Viville S., Vail A., Lundin K. Adjuncts in the IVF laboratory: where is the evidence for ‘add-on’ interventions? Human Reproduction. 2017;32(3):485–491. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HFEA, 2018. Pilot national fertility patient survey. Available at https://www.hfea.gov.uk/media/2702/pilot-national-fertility-patient-survey-2018.pdf [Accessed 19 March 2020]

- HFEA (2019). Inspection report and minutes – Interim (The Centre for Reproductive and Genetic Health). Available at https://www.hfea.gov.uk/choose-a-clinic/clinic-search/results/44/ [Accessed 12 September 2020]

- HFEA, 2019. Code of Practice. Sections 4.5-4.9. Available at https://www.hfea.gov.uk/media/2793/2019-01-03-code-of-practice-9th-edition-v2.pdf [Accessed 18 March 2020]

- HFEA, 2020a. Treatment add-ons. Available at https://www.hfea.gov.uk/treatments/explore-all-treatments/treatment-add-ons/ [Accessed 18 March 2020]

- HFEA, 2020b. Inspection report and minutes – Renewal (Harley Street Fertility Clinic. Available at https://www.hfea.gov.uk/choose-a-clinic/clinic-search/results/9113/

- Ho M., Huang L.C., Chang Y.Y. Electroacupuncture reduces uterine artery blood flow impedance in infertile women. Taiwanese J. Obstetrics Gynecology. 2009;48(2):148–151. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(09)60276-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuma A.C., Oktari N., Mihardja H., Srilestari A., Simadibrata C.L., Hestiantoro A., Wiweko B., Muna N. Electroacupuncture enhances number of mature oocytes and fertility rates for in vitro fertilization. Medical Acupuncture. 2019;31(5):289–297. doi: 10.1089/acu.2019.1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay, K., 2018. Huge disparity revealed in the cost of IVF treatment. Available at https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/huge-disparity-revealed-in-the-cost-of-private-ivf-treatment-58tjdhphj [Accessed 13 September 2020]

- National Health Service, 2019. Acupuncture. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/acupuncture/ [Accessed 12 September 2020]

- Paulus W.E., Zhang M., Strehler E., Seybold B., Sterzik K. Placebo-controlled trail of acupuncture effects in assisted reproduction therapy. Hum. Reprod. 2003;18:18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sananes N., Roth G.E., Aissi G.A., Meyer N., Bigler A., Bouschbacher J.-M., Helmlinger C., Viville B., Guilpain M., Gaudineau A., Akladios C.Y., Nisand I., Langer B., Vayssiere C., Favre R. Acupuncture version of breech presentation: a randomized sham-controlled single-blinded trial. Eur. J. Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biol. 2016;204:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.07.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.A., De Lacey S.I., Chapman M., Ratcliffe J., Norman R.J., Johnson N.P., Boothroyd C., Fahey P. Effect of acupuncture VS sham acupuncture on live births among women undergoing in vitro fertilization a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(19):1990–1998. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.5336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wiel L., Wilkinson J., Athanasiou P., Harper J. The prevalence, promotion and pricing of three IVF add-ons on fertility clinic websites. Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 2020:2020–2107. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S., Courtney U., Donnelly C., Kenny T., Lavin C. Clients' perceptions of the benefits of reflexology on their quality of life. Complementary Therapies in Nursing & Midwifery. 2002;8(2):69–76. doi: 10.1054/ctnm.2001.0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z.Y., Peng Z.H., Yao B., Chen L., Mu Y.Y., Cheng J., Li Q., Luo X., Yang P.Y., Xia Y.B. The effects of acupuncture on pregnancy outcomes of in vitro fertilization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2019;19(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2523-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]