Abstract

Variations in infant and neonatal mortality continue to persist in the United States and in other countries based on both socio-demographic characteristics, such as race and ethnicity, and geographic location. One potential driver of these differences is variations in access to risk-appropriate delivery care. The purpose of this article is to present the importance of delivery hospitals on neonatal outcomes, discuss variation in access to these hospitals for high-risk infants and their mothers, and to provide insight into drivers for differences in access to high-quality perinatal care using the available literature. This review also illustrates the lack of information on a number of topics that are crucial to the development of evidence-based interventions to improve access to appropriate delivery hospital services and thus optimize the outcomes of high-risk mothers and their newborns.

Overview of racial/ethnic disparities in infant and neonatal mortality

Variations in infant and neonatal mortality continue to persist in the United States (US) and in other countries based on both socio-demographic characteristics, such as race and ethnicity, and geographic location. In the United States, non-Hispanic black infants have an almost two-fold higher rate of infant mortality and a similar increase in neonatal mortality1. Similarly, infants residing in rural locations have higher rates of infant and neonatal mortality2. One potential driver of these differences is variations in access to risk-appropriate delivery care. Risk-appropriate care refers to the delivery of an infant at a hospital with the appropriate technology and staffing to care for the mother, to optimize delivery, and to care for a specific infant immediately after birth. This is typically captured by a hospital’s level of maternity care and neonatal intensive care. Another less studied aspect is variations in the quality of either maternity or neonatal care delivered to mothers and infants of different socio-demographic characteristics or residing in different geographic areas. The purpose of this article is to present the importance of delivery hospitals on neonatal outcomes, discuss variation in access to these hospitals by high-risk infants and their mothers, and to provide insight into drivers for differences in access to high-quality perinatal care using the available literature. We will conclude with areas for future research and challenges to these drivers, which is needed for policymakers to develop strategies to improve access to such care.

Why access to care matters: the impact of delivery hospital on neonatal outcomes

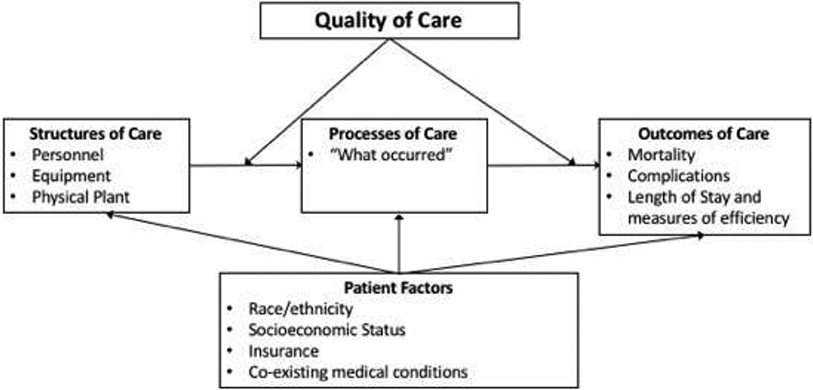

An extensive literature supports the concept that the capabilities and care provided by a hospital delivering an infant significantly influence the overall outcomes of that infant. This concept is based on a modification of the Donabedian framework describing the impact of structure and process on patient outcomes (Figure 1)3. In this framework, we see that structure, denoted by the capabilities of the delivery hospital to manage laboring women and their infants, influences the processes of care that the patients receive, which in turn affects the overall outcomes of the infant. In most of the literature on this topic, the structure of delivery care is defined by hospital level of care. Levels of care typically are assessed by a list of characteristics that a facility must have, with the most widely used list defined by the American Academy of Pediatrics4. These guidelines define a level 1 neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) as a hospital with the capacity to care for only well infants, while a level 4 unit can manage the sickest infants, including those that require major pediatric surgery, cardiopulmonary bypass, and ECMO.

Figure 1:

Donabedian framework describing the impact of structure and process on patient outcomes. Here, structure of care, typically in perinatal medicine defined as a maternal or neonatal level of care, influences the processes of care delivered to an infant, which then influence the outcome of an infant. Quality of care at a specific hospital may modify these associations, while infant characteristics may influence where an infant receives care, what processes of care may be delivered, and the infant’s outcome.

Studies demonstrate improved survival rates for infants delivered at hospitals with the resources to manage them during the initial resuscitation. The first study was undertaken in 1975, when eight geographic areas were randomly selected to receive funding to develop a regionalized system of perinatal care. Data on low-birth weight deliveries and neonatal outcomes in these regions were compared to similar areas that did not receive such funding. In the eight selected regions, 60% of infants weighing less than 1,500 grams were born at the appropriate, “high-level” center compared to 47% in the comparison regions. Mortality rates only changed marginally, because of an unexpectedly higher delivery rate at the high-level center in the control region5,6. However, other studies during this initial period of expansion of NICUs showed substantial improvement in neonatal survival when very-low birth weight infants were delivered at a hospital with a high-level unit. For 12,771 infants weighing less than 2,250 grams born in New York City between 1976 and 1978, delivery at a local hospital was associated with a 24% increase in mortality7. For low birth weight infants delivered at the highest level, similar improvements in survival were observed in the United States7-13, Australia14, Canada15, and the Netherlands16.

More recent studies support these older studies. In general, there was a 30 to 75% increase in mortality when infants with a birth weight under 1,500 grams were delivered at lower level or lower volume hospitals9,10,12,17-36. A meta-analysis of the evidence published through 2010 summarized these results, showing increased odds of death for very low birth weight infants born outside of hospitals with a level 3 or level 4 NICU, an odds ratio of 1.62. For infants with a birth weight less than 1,000 grams, this increase in odds of death was higher (odds ratio 1.80)32.

One important reason for this observed difference in outcomes is evidence that neonatal transfer after delivery, compared to maternal transfer prior to delivery, is associated with increased mortality and morbidity for the newborn. Bowman et al examined a natural experiment in Melbourne, Australia37. One of the two large tertiary NICUs in Melbourne was being remodeled a half of the unit at a time. Infants were randomly transferred to the other NICU depending of bed availability at the remodeled NICU. Even though the transferred infants had received tertiary obstetric care and immediate NICU care from the team at a high-volume NICU, those who were transferred had significantly worse outcomes including higher mortality. The paper discussion acknowledged that there was probably favorable selection among the transferred infants as they attempted to not move the most critical infants if it was at all possible. Further evidence of the adverse effects of the transport itself is seen in studies that formally assessed the physiological stability of infants using scales such as the Transport Risk Index of Physiologic Stability38-41. These studies find a measured decline in physiologic stability of infants between when they left the delivery hospital to arrival at the NICU41. Finally, Shaw and colleagues, examining data from Illinois between 2015 and 2016, found similar neonatal mortality rate for infants who delivered at a level 3 hospital after presenting at such a hospital initially for delivery, or delivered at such a hospital after antenatal maternal transfer (10.7% and 9.8%, respectively). However, infants transferred to a level 3 NICU after delivering at a hospital with a non-level 3 NICU had a mortality rate of 17.3%. After adjustment for patient characteristics, infants transferred after delivery had a 52% higher odds of death compared to infants born at a level 3 hospital regardless of whether mothers were transferred antenatally42.

The benefit of delivery hospital on outcomes may differ between different geographic locations. In a study of the effects of delivery hospital in three US states, authors found wide inter-state differences in the reduction in in-hospital death and several common morbidities of preterm birth. For instance, in Pennsylvania, there was a 65% reduction in all hospital deaths and a 73% reduction in neonatal deaths when a preterm infant delivered at a hospital with a high-level NICU, compared to an 18% reduction in all-hospital deaths in California and a 50% reduction in Missouri. Similarly, the reduction in bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) ranged from no change in Pennsylvania and California to 95% reduction in Missouri43,44. These results may reflect the differences in the perinatal regionalization program within each state, or differences in the quality of care either of the high-level, high-volume hospitals or at the lower level hospitals.

One natural experiment exists that demonstrates the impact of a shift to a fully regionalized system of perinatal care. Portugal has a national health system where there is no private sector alternative. In 1990, Portugal closed all small delivery services and low volume NICUs, while setting up a nationwide maternal referral/transport system. After full implementation almost 95% of the very preterm infants were delivering in a hospital with a high-volume NICU, and neonatal mortality fell from 8.1/1000 to 2.9/1000. Portugal’s neonatal mortality rate shifted from one of the worst in Europe to 3rd best in the World. Portugal also addressed the issue of rural access; they did not close the low-volume NICUs in the Azores or on Madeira45. Overall, the literature supports the important role of delivery hospital on patient outcomes, but that impact may vary depending on geographic site and the outcome examined.

It is important to note that level of care does not perfectly correlate with quality of care delivered by the hospital. There remain significant variations in hospital quality among hospitals of the same level, as demonstrated by Profit et al. in data from California46. Recently, the Vermont Oxford Network published data on the rates of mortality and common neonatal morbidity in 756 NICUs between 2005 and 2014. Each of their outcomes, except for bronchopulmonary dysplasia, substantially improved over this 10-year period. However, variations in inter-hospital rates persisted in all of these outcomes both in 2005 and 2014, with standardized differences between the 10th and 90th percentile hospitals remaining constant for mortality and all five morbidities studied (BPD, late-onset infection, NEC, severe IVH, and severe ROP)47.

One challenge with all of the available literature is the inherent selection bias in these studies. In general, hospitals with a higher level of care treat sicker mothers and infants. While studies use sophisticated and validated models to adjust for these differences in patient risk between hospitals, underlying unmeasured differences persist. This feature was best shown by studies by Lorch et al, which found a 3-fold increase in the benefit of delivering at a high-level, high-volume hospital for infants born at a gestational age of 35 weeks or less when techniques that account for these unmeasured differences were employed43,44. In that study, the authors showed no benefit to delivering at a high-level, high-volume hospital when unmeasured differences were not accounted for. As a result, interpreting the true impact of delivery hospital on neonatal outcomes may be challenging without adjusting for these differences in casemix between types of hospitals.

Models for Studying Access to Care

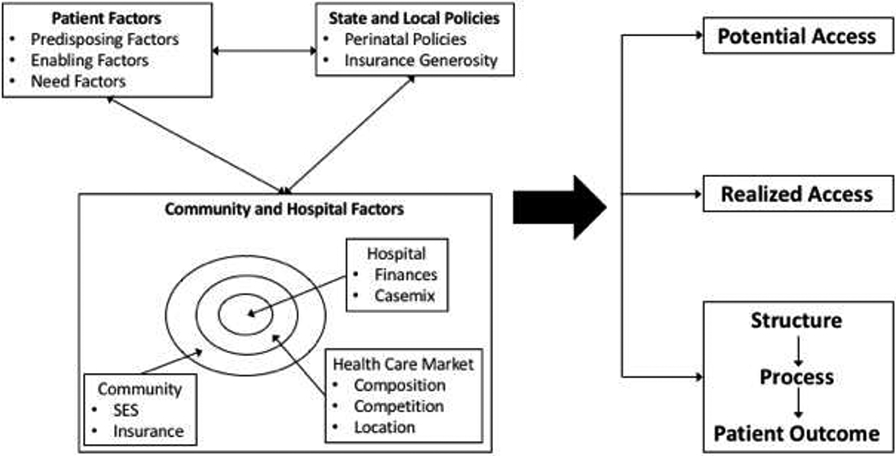

One hurdle to optimizing the care that high-risk newborns receive immediately after birth is appropriate access to hospitals with high-level, high-volume hospitals. Access to health care is a complicated process that involves the complex interplay of patient, community, and policy factors to determine whether a patient could have received care at the appropriate place (potential access to risk-appropriate care), and whether a patient actually received care at the appropriate place (realized access to risk-appropriate care). This framework can be illustrated with the Anderson-Aday behavioral model of health service use 48-53. Briefly, this model identifies sets of patient, community, and policy factors that may influence what access to health care a given patient receives (Figure 2). For the patient, the factors are divided into three groups:

Figure 2:

Anderson-Aday behavioral model of health service use for perinatal health care access. Patient factors; community, hospital, and market factors; and state policies interact to determine a patient’s potential access to risk-appropriate care; a patient’s realized access to risk-appropriate care; and an infant’s outcome as modified by the Donabedian framework highlighted in Figure 1.

Predisposing factors, including demographic information such as race/ethnicity, education, and patient beliefs about health care use

Enabling factors, such as health insurance and income

Need factors, which encompass health status and co-existing medical conditions

Based on a modification of the model published by Davidson, et al51, community factors encompass an array of health system and community-level factors that may promote or inhibit the ability of a patient to access a specific element of the health care system, such as geographic location of high-level hospitals, individual hospital quality, adequate supply of appropriate health care providers with specific characteristics to provide risk-appropriate care, and characteristics of the market that encourage appropriate access. An example of perinatal policy-level impacts could be national guidelines for the organization of perinatal care. The latter recommend the development of a regionalized perinatal system that matches the needs of the infant with the capabilities of the hospital54-56. This model has been applied to numerous studies of health care access, with more recent applications to specific patient populations such as rural patients57,58, immigrant populations, and women of minority racial/ethnic health status59.

One prior study of lower income adults aged 19-64 in 54 metropolitan statistical areas found that community factors may act differently for patients of different racial/ethnicities or with different types of health insurance. Here, community factors such as HMO penetration and the size of the lower-income and immigrant populations affected both potential access, as assessed by the percentage of the community reporting a usual source of care, and realized accessed, as assessed by the percentage of the community reporting at least 1 physician visit in a 12-month period, differently depending on whether the patient had health insurance. For example, potential access for insured patients was higher with greater HMO penetration in the community and a greater percentage of non-citizens in the area, while uninsured Latino patients were less likely to have potential access with greater HMO penetration 60. This study highlights the way that patient factors and community factors interact determine the ultimate access to risk-appropriate care.

Variations in accessing risk-appropriate perinatal care, by geography and race/ethnicity

No descriptions exist of variation in potential access to perinatal or neonatal care by race/ethnicity or rural-urban status, either within or across different regions or states in the United States. However, there have been studies of the realized access, or where patients of different racial/ethnic backgrounds or rurality receive care. This section will evaluate the available literature on racial ethnic and geographic variations in perinatal care access.

Race/ethnicity

Women of different racial and ethnic groups deliver their infants at different hospitals, and these hospitals may provide lower quality of care. This concept is best exemplified by a study of 743 NICUs in the Vermont Oxford Network from January 2014 to December 201661. Horbar and authors showed that infants were significantly segregated among the 743 NICUs by race and ethnicity. Using a Gini coefficient to calculate a segregation index, where 0 denotes no segregation across NICU use, and 1 denotes NICUs that only care for infants of one racial/ethnic background, black infants had a segregation index of 0.50 and Hispanic infants had a segregation index of 0.58. Hospitals that cared for a greater proportion of non-Hispanic black infants were more likely to have lower quality regardless of which region in the United States they lived in. Similar results were observed in an older study of Vermont Oxford Network hospitals, where hospitals with a higher proportion of non-Hispanic black very-low-birth weight infants had a 30% higher neonatal mortality rate than hospitals with a lower proportion of non-Hispanic black very-low-birth weight infants62. This increase in mortality at hospitals caring for a greater proportion of non-Hispanic black infants was seen in both White and Black infants at similar rates. Such data suggest that Minorityserving hospitals may have provided lower quality of care during the late 1990s.

Data from all delivery hospitals in New York City between 2006 and 2014 show similar results63. Using cluster analysis to categorize hospitals based on risk-adjusted rates of severe maternal morbidity, very preterm morbidity, and very preterm mortality, non-Hispanic black and Hispanic women were less likely to deliver at a hospital with the best rates compared to non-Hispanic white women (11%, 18%, and 28%, respectively), and more likely to deliver at a hospital in the worst rates (28%, 20%, and 4%, respectively). These data include Vermont Oxford Network members, who typically have a NICU, but also delivery hospitals that primarily deliver infants of term gestation without access to specialized neonatal intensive care services.

Geography

The extent to which access to risk-appropriate perinatal care prevents infant mortality in rural American is not well quantified. Two studies, one in Washington state in the 1980s and another in Canada, suggest that communities without nearby access to obstetric services were more likely to deliver preterm64 and have a higher rate of adverse perinatal outcomes.65 However, over the past 20 years, such access to obstetric and pediatric health care in rural communities has decreased even further. This decline is widely variable across states and regions.66,67 In 2014, 54% of rural counties had no access to obstetric or neonatal services, a 9% decline since 2004.66 The reason for such changes is unclear. However, growing financial pressures on rural-serving hospitals may contribute to these observed changes. Obstetric services tend to be one of the first hospital-based services to be eliminated when a hospital faces growing financial stress. The growing demographic and economic changes experienced by rural communities has contributed to more pressure on these hospitals, which could explain the observed decline in access to obstetric services in rural communities.

As a result, in a study of pregnant rural women in nine US states, only 43.1% of rural women with multiple gestation pregnancy and 40% of rural women with a preterm birth delivered in a hospital with a level 2 or higher NICU. This likelihood varies tremendously depending on whether the local hospital had a NICU compared to women whose local hospital did not. For mothers with multiple gestation whose local hospital had a level 2 or higher NICU, 69.9% delivered at a hospital with such capacity, compared to 37.6% of women whose local hospital did not have a NICU. Among mothers with a preterm delivery, 63.2% delivered at a hospital with a NICU if their local hospital had such capacity, compared to 35% of women who delivered at a hospital with a NICU when their local hospital did not have such capacity. Teenaged mothers, women without health insurance, and Medicaid beneficiaries were at the highest risk.68 In addition, non-Hispanic black women had a 40% lower likelihood of delivering at a hospital with a NICU compared to rural, non-Hispanic white women.

Further evidence for the importance of access to obstetric services is seen when obstetric units close in a specific community. The loss of urban obstetric units has been associated with an increase in neonatal mortality, specifically for infants at the extremes of the birth weight distribution.69 Loss of hospital-based obstetric care in rural communities is associated with increases in out-of-hospital birth and emergency birth, and with elevated rates of preterm birth in rural counties with fewer than 10,000 residents.70

In summary, rural Americans display limited potential and realized access to high-level neonatal intensive care for high-risk pregnancies. Such decline in access parallels a decline in access to any obstetric services observed in rural settings over the past 20 years. Women of minority racial/ethnic status, specifically non-Hispanic black women, have a disproportionately lower likelihood of receiving care at a hospital with a NICU compared to women of other racial/ethnic status. Some countries with more oversight into the placement of NICUs have addressed the issue of remote rural access by leaving low volume NICUs open in remote areas to facilitate access, such as units in the Azores and Madeira, two island groups of Portugal45, and a small NICU in the far north of Finland17,71.

Drivers of differences in realized access to high level, high quality neonatal care

As with descriptive studies of variations in realized access to perinatal care, few studies explore the drivers of observed variations in access by racial/ethnic status or geographic area of residence of the mother. This section will evaluate drivers using our conceptual framework outline in Figure 2. The majority of studies examine patient factors, specifically insurance, socioeconomic factors, and maternal or infant risk of an adverse outcome of pregnancy. This section will also examine differences secondary to the organization of healthcare, particularly the observation that many women deliver in hospitals close to their residence.

Patient-level drivers

Sociodemographic factors and insurance status

Public insurance and early receipt of prenatal care have been identified as key factors in determining where women initially opt to deliver. Data from California found that for high-risk deliveries, such as those with maternal chronic medical conditions or preterm labor, insurance coverage through public sources was associated with a greater likelihood of delivery at a hospital with worse outcomes and a lower likelihood of having a NICU72.

This pattern is also found in two studies of the drivers of racial/ethnic differences in the receipt of care at a risk-appropriate hospital. In the first study, Hebert et al, analyzed deliveries for mothers who delivered a very-low-birth weight infant in New York City between 1996 and 2001. They found that non-Hispanic black women were marginally more likely to reside closer to a hospital with a high-level NICU, but less likely to deliver at such a hospital compared to non-Hispanic white women73. One driver of this choice of hospital was the type of insurance used by non-Hispanic black women, as the racial disparity in delivery at a hospital with a high level NICU was eliminated when insurance status was accounted for in the analysis. The second study by Bronstein et al was based on women who delivered in Alabama between 1988 and 1990. They found that in women who were at risk for delivering prematurely, those who presented late to prenatal care were less likely to be transferred before delivery to hospitals with a NICU than those who received early prenatal care74. Overall, the protective effect of early prenatal care differed by racial/ethnic status: compared to non-Hispanic white privately insured women with early prenatal care, non-Hispanic white women with Medicaid insurance were more likely to present to a hospital without a NICU, and then be transferred prior to delivery.

For rural women, although medical risk is strongly associated with delivery at a hospital with a NICU, there are sociodemographic factors that alter this risk. In a study of rural residents in nine states in 2010 and 2012, high-risk (multiple gestation, preterm labor) rural women with Medicaid had a 19% lower odds of delivering at a hospital with a NICU compared to privately insured women, in an adjusted analysis. Uninsured women had even lower odds of delivering at such hospitals. Non-Hispanic black race was also an independent predictor of delivery at a hospital without a NICU68.

Health risk

As noted above, medical risk, whether the result of pre-existing maternal medical conditions or risk secondary to preterm birth, is strongly associated with delivery at a hospital with a high-level NICU regardless of patient population35,36,43,72. For example, in rural women, multiple gestation (OR 1.82) preterm delivery (OR 2.4) and conditions that may require consultation by a maternal-fetal medicine specialist (OR 1.28) were all associated with a higher likelihood of delivering at a hospital more than 30 miles from a patient’s residence, defined as a “nonlocal” hospital, compared to women with a singleton pregnancy delivering at term gestation without any co-existing medical conditions. These women made up the 25% of the total population of rural women that delivered at a nonlocal hospital75. Similar associations between patient or pregnancy risk and delivery at a hospital with a high-level NICU has been seen consistently in multiple studies spanning many areas in the United States.

Hospital-level Factors

While studies in adult patients have shown that public reporting of hospital quality may influence patient choice, there is limited data on the role that hospital quality plays in determining either the choice of delivery hospital or disparities in such decisions. In the aforementioned study of hospital choice for non-Hispanic black and white women delivering a very-low birth weight infant in New York City, the odds of delivering at a hospital with either a high-level NICU or higher delivery volume was greater in non-Hispanic white women compared to non-Hispanic black women (OR 2.6 vs. 1.7, respectively). As noted above, insurance status appears to mediate this choice73. Other measures of quality have not been examined as drivers of the choice of delivery hospital, or as drivers for differences in this choice by race/ethnicity or rural-urban status.

Geographic access to risk-appropriate perinatal hospitals

One of the strongest predictors of delivery hospital choice is the travel distance to the hospital. Most women tend to deliver at hospitals that are near their residence43,72. Factors such as medical risk and risk for preterm birth are associated with a higher likelihood to bypass the nearest delivery hospital regardless of race/ethnicity or rural-urban status. Women who bypass nearby hospitals in general deliver at hospitals with specialized maternal services and a high-level NICU. In contrast, studies suggest that late presentation to prenatal care and fewer prenatal visits are associated with a lower likelihood of bypass of the nearest delivery hospital after adjusting for medical risk43,72. These data are also consistent with the behavior of rural Medicare patients, where bypass behavior is observed in patients with complex medical conditions or patients who require complex medical or surgical management not available at their local hospital76-78.

Additional Predictors

In other patient populations additional barriers to access to risk-appropriate care have been identified that have not been studied in perinatal care. For example, a recent systematic review of the drivers for access to specialty healthcare in urban and rural populations identified key dimensions such as state or Federal government and insurance policies stigma, and primary and specialty physician influence79. These drivers have not yet been explored in maternal or neonatal care but have substantial face validity. In addition, few qualitative studies have collected information on the barriers or facilitators to receipt of risk-appropriate perinatal care by women of different sociodemographic or rural-urban backgrounds.

Impact of variations in access on outcomes of high-risk infants

Few studies have examined how disparities in access to high-quality hospital care impact newborn outcomes. One study from New York City showed that Non-Hispanic white infants were more likely to be born in the lowest mortality tertile hospitals in the city (49%), compared to non-Hispanic black infants (29%), using data on births in New York City from January 1, 1996, to December 31, 2001. The study estimated that 34.5% of the black-white disparity in very low birth weight neonatal mortality rates would be eliminated if non-Hispanic black infants delivered at the same hospitals as non-Hispanic white infants80. A follow-up study assessing infants born between 24 and 31 weeks gestational age in 39 New York City hospitals from 2010 and 2014 found similar clustering of non-Hispanic black and Hispanic infants admitted into hospitals with the highest morbidity and mortality. As a result, 40% of the black-white disparity in morbidity and mortality and 30% of the Hispanic white disparity in morbidity and mortality were explained by disparities in birth hospital quality81. In these studies, hospital quality was assessed by risk-adjusted morbidity and or mortality rates rather than the structural characteristics of the hospital, such as level of care. In contrast, such results were not found in a recent study of California births, which estimated that only 7-10% of the racial/ethnic disparity in neonatal mortality and morbidity could be assigned to differences in delivery hospital82. These results suggest that further work is needed to define these risks across different geographic regions with different perinatal health care systems.

The effect of delivering at a high-level hospital may be larger for non-Hispanic black or Hispanic infants born prematurely compared to non-Hispanic white infants. Using data from all infants born between 24 and 32 weeks gestational age or a birth weight less than 2,500 grams in California, Missouri, and Pennsylvania between 1995 and 2009, Yannekis et al showed that, compared to non-Hispanic white infants, non-Hispanic black and Hispanic infants had a greater reduction in the risk of developing a common complications of preterm birth such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotizing enterocolitis, intraventricular hemorrhage, or retinopathy of prematurity when they delivered at a hospital with a high volume, high-level NICU83. The largest reduction was seen in the extremely low birth weight cohort and the cohort of infants with a gestational age between 24 and 28 weeks with an approximate 25% reduction in the prevalence of these morbidities. In contrast to these findings, there was no differential effect of delivering at a hospital with a high-volume, high-level NICU based on an infant’s insurance status. Such results may occur either if high-level, high-volume hospitals provide superior care to infants of minority racial/ethnic status, or if minority-serving delivery hospitals that are lower level or volume provide lesser quality of care than such hospitals serving primarily non-Hispanic white populations.

Only one study has examined differences between hospitals that primarily care for non-Hispanic black infants versus those hospitals that primarily care for non-Hispanic white populations. Such structural differences may explain both the increased mortality and morbidity observed in the population studies from New York City, and the greater improvement in neonatal outcomes when non-Hispanic black infants deliver at high-level, high-volume hospitals. Lake et al classified 98 Vermont Oxford Network hospitals based on the percentage of infants they deliver of non-Hispanic black race84. Compared to the hospitals that cared for the lowest tertile of non-Hispanic black infants, hospitals in the highest tertile were more likely to report nurse understaffing and more adverse nurse practice environments. These nursing features accounted for one-third to one-half of observed disparities in nosocomial infection rates and discharge with breast milk between these hospitals.

Limitations to the literature base and next steps

As this literature review demonstrates, there is evidence for racial/ethnic and rural-urban variation in delivery hospitals, and that these variations contribute substantially to observed disparities in outcomes among women of minority racial/ethnic status or women who reside in rural communities. However, this review also illustrates the lack of information on a number of topics that are crucial to the development of evidence-based interventions to improve access to appropriate delivery hospital services and thus optimize the outcomes of high-risk mothers and their newborns. Some areas for further research are listed below.

Lack of studies on factors that encourage access to risk-appropriate delivery hospital care:

In our conceptual framework presented in figure 2, factors may either influence the potential access to risk-appropriate perinatal care, or impact the actual location that a woman receives care (realized access). The few studies of drivers for risk appropriate perinatal care in rural-urban or different racial/ethnic groups focus primarily on factors that influence realized access to care. As a result, we have no data to determine how factors such as governmental policies, geographic locations of hospitals, and other sociodemographic factors such as transportation policies and the health of the perinatal system affect the potential access to such hospitals for various rural urban or racial ethnic groups. In addition, insurance contracts, integrated delivery systems, and less formal hospital contracts dictate where patients in other specialties receive care, but little is known about how these financial arrangements impact access to risk-appropriate perinatal care. As most policies do not dictate where a woman may receive care, but rather influence the likelihood that she can receive care at a specific location55, such lack of data hampers our ability to develop risk appropriate and evidence-based policies to encourage women to receive care at a risk appropriate location.

Few studies of the patient or hospital factors influencing the choice of delivery hospital for different racial/ethnic or rural-urban groups:

There are few studies of degree to which specific patient or hospital factors impact access to risk appropriate perinatal care for various socio- demographic groups. These studies are limited to specific geographic areas, such as New York City or Alabama. Prior work from our group suggests that the benefit of delivery at a hospital with a high-level NICU difference between regions and states, is potentially the result of dissimilar perinatal systems and how they interact between hospitals to optimize the care and outcomes of women at high risk of an adverse pregnancy outcome43. Future work to expand the geographic scope of studies of the prevalence of delivering at a risk appropriate hospital for various patient populations is needed to determine whether there are generalizable factors, either at the patient or hospital-level, that affect the likelihood of delivering at an appropriate hospital, or whether such factors vary across geographic regions.

Few studies of the potential benefit of improving access to risk appropriate perinatal care:

Only two studies so far have attempted to define the benefit for disparities in neonatal outcomes when access to high-level neonatal care is improved. These studies suggest that the impact could be significant, although the degree of benefit varied between New York City and California. Such work emphasizes the need to incorporate characteristics of the healthcare system, as well as a more accurate measurement of the quality of care at an individual hospital. Levels of care designations may obscure substantial variations in care quality between hospitals of similar levels85. Such variation may differ between geographic areas, which would explain these disparate results in different studies. Similarly, the differential improvement in outcomes between non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white women when delivering at a hospital with a high-level NICU supports the premise that lower level hospitals attended by women of different racial/ethnic backgrounds may not provide the same quality of care83. Further studies are needed to clarify this issue, and to provide policymakers with evidence to develop strategies specific for a given geographic area to optimize perinatal outcomes. Finally, the recent publication of suggested levels of maternity care by both the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology and the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine point to a new avenue to provide access to risk-appropriate perinatal care86. Formal studies of the impact of care at different levels of maternity care are needed.

The need to study high-risk populations in rural communities:

The few studies of minority racial/ethnic patients in rural communities provide sobering information on both their access to healthcare and elevated risk of adverse neonatal and maternal outcomes. However, few studies of this topic exist, particularly in areas of the country with a relatively large population of rural minority racial/ethnic women and children. Studies of the unique needs of this population are necessary to mitigate the heightened risk of adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes.

Conclusion

This review provides information on variations in access to risk appropriate perinatal care, the drivers of this disparity, and the impact on perinatal outcomes of such disparities in access to care. As our conceptual framework demonstrates, many questions remain about the drivers of these disparities, the evidence-based policy solutions needed to improve potential access for these patient populations to risk appropriate perinatal care, and how to improve the realized access for these women who choose such risk appropriate care. Expanding the evidence base to diverse populations in varying geographic areas who experience different perinatal healthcare systems is imperative to optimizing the outcomes of these high-risk populations.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This study is supported in part by R01HD084819-01A1 from the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement:

The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Xu J, Murphy SL, Kockanek KD, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2018. NCHS data brief. 2020(355): 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ely DM, Driscoll AK, Matthews TJ. Infant Mortality Rates in Rural and Urban Areas in the United States, 2014. NCHS data brief. 2017(285): 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donabedian A Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):691–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):587–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormick MC, Shapiro S, Starfield BH. The regionalization of perinatal services. Summary of the evaluation of a national demonstration program. JAMA. 1985;253(6):799–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Committee on Perinatal Health. Toward Improving the Outcome of Pregnancy: Recommendations for the Regional Development of Maternal and Perinatal Health Sercies. White Plains, NY: March of Dimes National Foundation. 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paneth N, Kiely JL, Wallenstein S, Susser M. The choice of place of delivery. Effect of hospital level on mortality in all singleton births in New York City. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1987;141(1):60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Modanlou HD, Dorchester W, Freeman RK, Rommal C. Perinatal transport to a regional perinatal center in a metropolitan area: Maternal versus neonatal transport. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1980; 138(8): 1157–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gortmaker S, Sobol A, Clark C, Walker DK, Geronimus A. The survival of very low-birth weight infants by level of hospital of birth: A population study of perinatal systems in four states. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1985; 152(5):517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powell SL, Holt VL, Hickok DE, Easterling T, Connell FA. Recent changes in delivery site of low-birth-weight infants in Washington: Impact on birth weight-specific mortality. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995; 173(5): 1585–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bode MM, O'Shea TM, Metzguer KR, Stiles AD. Perinatal regionalization and neonatal mortality in North Carolina, 1968–1994. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;184(6): 1302–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeast JD, Poskin M, Stockbauer JW, Shaffer S. Changing patterns in regionalization of perinatal care and the impact on neonatal mortality. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998; 178(1 Pt 1): 131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berg CJ, Druschel CM, McCarthy BJ, LaVoie M, Floyd RL. Neonatal mortality in normal birth weight babies: Does the level of hospital care make a difference? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1989;161(1):86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group. Changing outcome for infants of birth-weight 500–999g born outside level 3 centres in Victoria. The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;37(3):253–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peddle LJ, Brown H, Buckley J, et al. Voluntary regionalization and associated trends in perinatal care: The Nova Scotia Reproductive Care Program. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1983;145(2):170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kollee LA, Verloove-Vanhorick PP, Verwey RA, Brand R, Ruys JH. Maternal and neonatal transport: Results of a national collaborative survey of preterm and very low birth weight infants in The Netherlands. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72(5):729–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rautava L, Lehtonen L, Peltola M, et al. The effect of birth in secondary- or tertiary-level hospitals in Finland on mortality in very preterm infants: A birth-register study. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):e257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Empana JP, Subtil D, Truffert P. In-hospital mortality of newborn infants born before 33 weeks of gestation depends on the initial level of neonatal care: The EPIPAGE study. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92(3):346–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johansson S, Montgomery SM, Ekbom A, et al. Preterm delivery, level of care, and infant death in sweden: A population-based study. Pediatrics. 2004; 113(5): 1230–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirby RS. Perinatal mortality: The role of hospital of birth. J Perinatol. 1996; 16(1):43–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marlow N, Bennett C, Draper ES, Hennessy EM, Morgan AS, Costeloe KL. Perinatal outcomes for extremely preterm babies in relation to place of birth in England: The EPICure 2 study. Archives of Diseases of Childhood Fetal Neonatal Edition. 2014;99(3):F181–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayfield JA, Rosenblatt RA, Baldwin LM, Chu J, Logerfo JP. The relation of obstetrical volume and nursery level to perinatal mortality. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(7):819–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menard MK, Liu Q, Holgren EA, Sappenfield WM. Neonatal mortality for very low birth weight deliveries in South Carolina by level of hospital perinatal service. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998; 179(2):374–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merlo J, Gerdtham UG, Eckerlund I, et al. Hospital level of care and neonatal mortality in low- and high-risk deliveries: Reassessing the question in Sweden by multilevel analysis. Med Care. 2005;43(11): 1092–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paneth N, Kiely JL, Susser M. Age at death used to assess the effect of interhospital transfer of newborns. Pediatrics. 1984;73(6):854–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paneth N, Kiely JL, Wallenstein S, Marcus M, Pakter J, Susser M. Newborn intensive care and neonatal mortality in low-birth-weight infants: A population study. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(3): 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samuelson JL, Buehler JW, Norris D, Sadek R. Maternal characteristics associated with place of delivery and neonatal mortality rates among very-low-birthweight infants, Georgia. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2002;16(4):305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanderson M, Sappenfield WM, Jespersen KM, Liu Q, Baker SL. Association between level of delivery hospital and neonatal outcomes among South Carolina Medicaid recipients. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000; 183(6): 1504–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Towers CV, Bonebrake R, Padilla G, Rumney P. The effect of transport on the rate of severe intraventricular hemorrhage in very low birth weight infants. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(2):291–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verloove-Vanhorick SP, Verwey RA, Ebeling MC, Brand R, Ruys JH. Mortality in very preterm and very low birth weight infants according to place of birth and level of care: Results of a national collaborative survey of preterm and very low birth weight infants in The Netherlands. Pediatrics. 1988;81(3):404–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warner B, Musial MJ, Chenier T, Donovan E. The effect of birth hospital type on the outcome of very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2004; 113(1 Pt 1):35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lasswell SM, Barfield WD, Rochat RW, Blackmon L. Perinatal regionalization for very low-birth-weight and very preterm infants: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(9):992–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung JH, Phibbs CS, Boscardin WJ, et al. Examining the effect of hospital-level factors on mortality of very low birth weight infants using multilevel modeling. J Perinatol. 2011;31(12):770–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung JH, Phibbs CS, Boscardin WJ, Kominski GF, Ortega AN, Needleman J. The effect of neonatal intensive care level and hospital volume on mortality of very low birth weight infants. Med Care. 2010;48(7):635–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phibbs CS, Baker LC, Caughey AB, Danielsen B, Schmitt SK, Phibbs RH. Level and volume of neonatal intensive care and mortality in very-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(21):2165–2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phibbs CS, Bronstein JM, Buxton E, Phibbs RH. The effects of patient volume and level of care at the hospital of birth on neonatal mortality. JAMA. 1996;276(13):1054–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bowman E, Doyle LW, Murton LJ, Roy RN, Kitchen WH. Increased mortality of preterm infants transferred between tertiary perinatal centres. BMJ. 1988;297(6656):1098–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SK, Zupancic JA, Pendray M, et al. Transport risk index of physiologic stability: A practical system for assessing infant transport care. J Pediatr. 2001;139(2):220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eliason SH, Whyte H, Dow K, Cronin CM, Lee S. Variations in transport outcomes of outborn infants among Canadian neonatal intensive care units. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30(5):377–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gould JB, Danielsen BH, Bollman L, Hackel A, Murphy B. Estimating the quality of neonatal transport in California. J Perinatol. 2013;33(12):964–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arora P, Bajaj M, Natarajan G, et al. Impact of interhospital transport on the physiologic status of very low-birth-weight infants. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31(3):237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shah KP, deRegnier RO, Grobman WA, Bennett AC. Neonatal Mortality After Interhospital Transfer of Pregnant Women for Imminent Very Preterm Birth in Illinois. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(4):358–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lorch SA, Baiocchi M, Ahlberg CE, Small DS. The differential impact of delivery hospital on the outcomes of premature infants. Pediatrics. 2012;130(2):270–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baiocchi M, Small DS, Lorch SA, Rosenbaum PR. Building a stronger instrument in an observational study of perinatal care for premature infants. J Am Stat Assoc. 2010; 105(492): 1285–1296. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neto MT. Perinatal care in Portugal: effects of 15 years of a regionalized system. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95(11): 1349–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Profit J, Gould JB, Bennett M, et al. The association of level of care with NICU quality. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20144210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Horbar JD, Edwards EM, Greenberg LT, et al. Variation in performance of Neonatal Intensive Care Units in the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2017:e164396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res 1974;9(3):208–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aday LA, Andersen RM. Equity of access to medical care: a conceptual and empirical overview Med Care. 1981;19(Suppl 12):4–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andersen JG. Demographic factors affecting health services utilization: a causal model. Med Care. 1973;11(2): 104–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davidson PL AR, Wyn R, Brown ER A framework for evaluating safety-net and other community-level factors on access for low income populations. Inquiry. 2004;41(1):21–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phillips KA MK, Andersen R, Aday LA. Understanding the context of healthcare utilization: assessing environmental and provider-related variables in the behavioral model of utilization. Health Serv Res. 1998;33(3):571–598. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davidson PL AR, Wyn R, Brown ER. A framework for evaluating safety-net and other community- level factors on access for lowincome populations. Inquiry. 2004;41(1):21–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lorch SA, Myers S, Carr B. The regionalization of pediatric health care: A state of the art review. Pediatrics. 2010; 126(6): 1182–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lorch SA. Perinatal legislative policies and health outcomes. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(6):375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stark AR. Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):587–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.RT S Developing policies responsive to barriers to health care among rural residents: What do we need to know? J Rural Health. 2002;18(Suppl):233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.KD. Generational cohorts, age at arrival, and access to health services among Asian and Latino immigrant adults. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(2):395–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Copeland VC BJ. Reconceptualizing access: a cultural competence approach to improving the mental health of African American women. Soc Work Public Health. 2007;23(2–3):35–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown ER DP, Yu H, Wyn R, Anderson RM, Becerra L, Razack N. . Effects of Community Factors on Access to Ambulatory Care for Lower-Income Adults in Large Urban Communities Inquiry. 2004. 41:39–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Horbar JD, Edwards EM, Greenberg LT, et al. Racial Segregation and Inequality in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit for Very Low-Birth-Weight and Very Preterm Infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2019; 173(5):455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morales LS, Staiger D, Horbar JD, et al. Mortality among very low-birthweight infants in hospitals serving minority populations. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(12):2206–2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Howell EA JT, Blum J, et al. Double Disadvantage in Delivery Hospital for Black and Hispanic Women and High-Risk Infants. . Matern Child Health J 2020;24(6):687–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nesbitt TS, Connell FA, Hart LG, Rosenblatt RA. Access to obstetric care in rural areas: effect on birth outcomes. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(7):814–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grzybowski S, Stoll K, Kornelsen J. Distance matters: a population based study examining access to maternity services for rural women. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hung P, Henning-Smith CE, Casey MM, Kozhimannil KB. Access To Obstetric Services In Rural Counties Still Declining, With 9 Percent Losing Services, 2004–14. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(9): 1663–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hung P, Kozhimannil KB, Casey MM, Moscovice IS. Why Are Obstetric Units in Rural Hospitals Closing Their Doors? Health Serv Res. 2016;51(4): 1546–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kozhimannil KB, Hung P, Casey MM, Lorch SA. Factors associated with high-risk rural women giving birth in non-NICU hospital settings. J Perinatol. 2016;36(7):510–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lorch SA, Srinivas SK, Ahlberg C, Small DS. The impact of obstetric unit closures on maternal and infant pregnancy outcomes. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(2 Pt 1):455–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kozhimannil KB, Hung P, Henning-Smith C, Casey MM, Prasad S. Association Between Loss of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services and Birth Outcomes in Rural Counties in the United States. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1239–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Helenius K, Gissler M, Lehtonen L. Trends in centralization of very preterm deliveries and neonatal survival in Finland in 1987–2017. Transl Pediatr. 2019;8(3):227–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Phibbs CS, Mark DH, Luft HS, et al. Choice of hospital for delivery: A comparison of high-risk and low-risk women. Health Serv Res. 1993;28(2):201–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hebert PL CM, Howell EA. The contribution of geography to black/white differences in the use of low neonatal mortality hospitals in New York City. Med Care 2011;49(2):200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bronstein JM, Capilouto E, Carlo WA, Haywood JL, Goldenberg RL. Access to neonatal intensive care for low-birthweight infants: The role of maternal characteristics. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(3):357–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kozhimannil KB CM, Hung P, Prasad S, Moscovice IS. Location of childbirth for rural women: implications for maternal levels of care. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016;214(5):661.e661–661.e610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adams EK, Houchens R, Wright GE, Robbins J. Predicting hospital choice for rural Medicare beneficiaries: The role of severity of illness. Health Serv Res. 1991;26(5):583–612. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tai WT, Porell FW, Adams EK. Hospital choice of rural Medicare beneficiaries: Patient, hospital attributes, and the patient-physician relationship. Health Serv Res. 2004;39((6 Pt 1)): 1903–1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Adams EK, Wright GE. Hospital choice of Medicare beneficiaries in a rural market: Why not the closest? J Rural Health. 1991;7(2): 134–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cyr ME EA, Guthrie BJ, Benneyan JC. Access to specialty healthcare in urban versus rural US populations: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Howell EA, Hebert P, Chatterjee S, Kleinman LC, Chassin MR. Black/white differences in very low birth weight neonatal mortality rates among New York City hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):e407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Howell EA JT, Hebert PL, Egorova NN, Balbierz A. Differences in Morbidity and Mortality Rates in Black, White, and Hispanic Very Preterm Infants Among New York City Hospitals. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(3):269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mujahid MS, Kan P, Leonard SA, et al. Birth hospital and racial and ethnic differences in severe maternal morbidity in the state of California. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yannekis G, Passarella M, Lorch S. Differential effects of delivery hospital on mortality and morbidity in minority premature and low birth weight neonates. J Perinatol. 2020;40(3):404–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lake ET, Staiger D, Horbar J, Kenny MJ, Patrick T, Rogowski JA. Disparities in perinatal quality outcomes for very low birth weight infants in neonatal intensive care. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(2):374–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Horbar JD, Edwards EM, Greenberg LT, et al. Variation in Performance of Neonatal Intensive Care Units in the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(3):e164396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Obstetric Care Consensus #9: Levels of Maternal Care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221(6): B19–B30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]