Abstract

Background

Advertising of less healthy foods and drinks is hypothesised to be associated with obesity in adults and children. In February 2019, Transport for London implemented restrictions on advertisements for foods and beverages high in fat, salt or sugar across its network as part of a city-wide strategy to tackle childhood obesity. The policy was extensively debated in the press. This paper identifies arguments for and against the restrictions. Focusing on arguments against the restrictions, it then goes on to deconstruct the discursive strategies underpinning them.

Methods

A qualitative thematic content analysis of media coverage of the restrictions (the ‘ban’) in UK newspapers and trade press was followed by a document analysis of arguments against the ban. A search period of March 1, 2018 to May 31, 2019 covered: (i) the launch of the public consultation on the ban in May 2018; (ii) the announcement of the ban in November 2018; and (iii) its implementation in February 2019. A systematic search of printed and online publications in English distributed in the UK or published on UK-specific websites identified 152 articles.

Results

Arguments in favour of the ban focused on inequalities and childhood obesity. Arguments against the ban centred on two claims: that childhood obesity was not the ‘right’ priority; and that an advertising ban was not an effective way to address childhood obesity. These claims were justified via three discursive approaches: (i) claiming more ‘important’ priorities for action; (ii) disputing the science behind the ban; (iii) emphasising potential financial costs of the ban.

Conclusion

The discursive tactics used in media sources to argue against the ban draw on frames widely used by unhealthy commodities industries in response to structural public health interventions. Our analyses highlight the need for interventions to be framed in ways that can pre-emptively counter common criticisms.

Keywords: Advertising, Regulation, Childhood obesity, Media

Highlights

-

•

The first analysis of news coverage of regulation of food advertisements on public transport.

-

•

Arguments against the ban claimed childhood obesity was not a valid priority and restricting advertising was ill advised.

-

•

Public health interventions need to be framed in ways that can pre-emptively counter opposition.

1. Introduction

1.1. Diet, health and advertising

Poor diet is a key modifiable determinant of childhood obesity (Jennings, Welch, van Sluijs, Griffin, & Cassidy, 2011). In the UK, children's average intakes of free sugars and saturated fat exceed Government recommendations, while consumption of fruits and vegetables is lower than recommended levels (Bates et al., 2016). The latest figures show that in the UK one in five children in year 6 (age 10–11 years) are obese (NHS Digital, 2020). Children living with overweight or obesity suffer physical and psychological ill health, are more likely to remain obese or overweight in adulthood, and develop chronic disease at a younger age (Sahoo et al., 2015).

Food advertising has a direct effect on children's nutrition knowledge, preferences, consumption patterns and diet-related health. Advertising on television and other marketing practices predominantly promote less healthy products (Cairns, Angus, Hastings, & Caraher, 2013). It has been shown that for children aged 4–12 years, exposure to advertising for high fat, salt and sugar (HFSS) foods and beverages (hereafter referred to as ‘food’) is significantly related to consumption of advertised brands and energy-dense product categories more generally (Buijzen, Schuurman, & Bomhof, 2008). Since 2007, television advertisements within children's programming are not permitted to show HFSS food advertisements (Galbraith-Emami & Lobstein, 2013Galbraith‐Emami & Lobstein, 2013). Stricter restrictions both on television and online are currently being considered (Department of Health and Social Care, 2020). Such policies are predicted to have important impacts on population health (Mytton et al., 2020). However, children are still exposed to high amounts of less healthy food advertising beyond television (Whalen, Harrold, Child, Halford, & Boyland, 2017) and evidence suggests that stronger restrictions targeting a wider range of media channels are required to reduce exposure of children to marketing of less healthy foods (Adams, Tyrrell, Adamson, & White, 2012).

The majority of research on food advertising and diet has focused on television while outdoor food advertising has received little attention (Adams, Ganiti, & White, 2011). A high proportion of outdoor advertising in the UK appears in spaces linked to public transportation, such as subway and rail stations, bus-stops and transport hubs. Research in the US found that subway-station advertisements for “less-healthful” foods were disproportionately located in more disadvantaged areas (Lucan, Maroko, Sanon, & Schechter, 2017) and this may also be the case in the UK. Research on advertising specific to transport hubs remains very much under researched (Gentry et al., 2011).

1.2. TfL and restrictions on advertisements for HFSS products

Greater London is the largest metropolitan area in the UK and home to 16% of England's population. Transport for London (TfL) is the local government body responsible for the transport system in Greater London and is under the control of the Mayor of London. It has responsibility for London's network of principal road routes and for various rail networks. TfL has one of the most valuable advertising estates in the world and makes up 20% of the UK's outdoor advertising by value (Mayor of London, 2018).

In February 2019, TfL implemented restrictions on advertisements for HFSS foods across its network (see Table 1) – or a ‘junk food ad ban’ as it was widely referred to in the media – as part of the Mayor's strategy to tackle childhood obesity (Mayor of London Transport for London). Under the policy, food products were subject to the advertising restrictions if they were classified as HFSS under a points-based nutrient profiling model (NPM). The final nutrient profile score is calculated by subtracting the fruit, vegetable, nut, fibre and protein content score from the energy sugar, salt and saturated fats score. Foods with a final score of 4 or more and drinks with a final score of 1 or more are classified as HFSS (Advertising Standards Authority, 2017; Department of Health, 2011). The NPM model has been in use since 2007 in the UK to determine what foods can be advertised on television.

Table 1.

Timeline and details of the TfL HFSS advertising restrictions.

| Date | Development |

|---|---|

| May 2018 | Launch of the public consultation on the ban |

| November 2018 | Announcement of the ban |

| February 2019 | Implementation of the ban. No foods are banned automatically, rather individual products are objectively assessed against the NPM. A score of 4+ for foods and 1+ for drinks classifies them as HFSS. |

| Products classified as HFSS can be considered for an exception if the advertiser can demonstrate that the product does not contribute to consumption of HFSS foods by children. | |

| June 2019 | TfL issues updated guidance to advertisers on what is acceptable to advertise |

Policies that seek to regulate commercial behaviours, like the ‘junk food ad ban’, are controversial. Regulation of the commercial sector for public health purposes often generates resistance from corporations involved in the production, marketing and retailing of the targeted commodities (BBC News, 2012; Food and Drink Federation, 2019). These corporations are typically unhealthy commodities industries (UCIs): processed foods, tobacco and alcohol (Stuckler, McKee, Ebrahim, & Basu, 2012). The strategies that UCIs use to oppose regulation are increasingly the subject of research (The PLoS Medicine Editors, 2012), which has demonstrated the existence of a cross-industry ‘playbook’ of arguments and strategies, use of which results in the undermining of proposals for effective public health policies (Petticrew et al., 2017).

Arguments from this playbook include claims that: certain public health issues are not severe enough to warrant intervention; intervening in the market will not prompt behaviour change; proposed interventions will not be effective; the science or evidence underpinning proposed interventions is lacking or flawed; proposed interventions will have dire economic consequences; and proposed interventions are potentially illegal and/or anti-competitive (Hilton et al., 2019).

By contrast, proponents of public health interventions aimed at unhealthy commodities emphasise health-related harms and risks (Weerasinghe et al., 2020). Advocates tend to stress: the social and political determinants of health; the need for regulation and population-based interventions; and industry's focus on profits and economic interests ahead of any moral considerations (Wakefield, Mcleod, & Smith, 2003). Arguments for regulation highlight the social environment and position industry and its profit-driven priorities as a part of that environment that can and should be modified (Weishaar et al., 2016).

Research into how public health policy debates are framed in the media may help to inform media advocacy strategies (Katikireddi & Hilton, 2015). Given that news media has a strong influence on public debate and policy making, and UCIs have shown great adeptness at having their perspectives regularly included in news media coverage (Vallance et al., 2020), news coverage can be understood as a contested space in which power relations and opposing interests are played out.

Public acceptability of interventions are influenced by a range of factors including how they are felt to intrude on personal autonomy and the perceived importance of the public health problem being targeted (Adams, Mytton, White, & Monsivais, 2016; Diepeveen, Ling, Suhrcke, Roland, & Marteau, 2013). News coverage independently shapes and frames public discourses around factors that influence public support of or opposition to public health interventions (Cameron Wild et al., 2019). The specific framing of issues influences whether or not they are identified as problems worthy of political action and can help legitimise or preclude certain responses to perceived problems (Hawkins & Holden, 2013). This paper aims to explore how the TfL advertising restrictions were covered in the press and how the factors that could influence public acceptability were framed within that coverage. In doing so, it will address the following research questions:

-

i)

What were the arguments made in favour of and against the TfL HFSS advertising restrictions in UK newspapers and trade press?

-

ii)

How were arguments against the restrictions constructed and framed?

Addressing these questions will provide insights as to the implications of these frames for the design and communication of public health interventions around unhealthy commodities.

1.3. Conceptual framework

Media coverage of policy measures related to unhealthy commodities, and control of unhealthy commodity industries, can influence public debate and is often more aligned with the interests of the relevant industries than those of public health (Mercille, 2017). Newsprint coverage of interventions to address obesity tend to favour accounts of individual responsibility for obesity (Ries, Rachul, & Caulfied, 2011). We use Framing Theory (Chong & Druckman, 2007) to explore the mechanisms through which media coverage of interventions affecting UCIs are aligned with industry interests and Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) to examine how this alignment is achieved and the key strategies used.

How a topic is presented to audiences, the frame, influences how those audiences process that information. Frames help to consistently structure meanings and arguments (Schön & Rein, 1996). Framing theory offers insights into how policy problems and solutions are conceptualised (Hawkins & Holden, 2013). The main premise of framing theory is that a topic can be viewed from a range of perspectives which have implications for values and interpretations (Chong & Druckman, 2007). The public participates in the framing of issues via the media. They develop their own interpretation of media messages and discuss the issues reported by making use of the resources available to them (including those from the media) (Pan & Kosicki, 2005). By identifying and understanding the dominant framings of public health issues, framing theory can help make those debates comprehensible and illuminates the processes through which specific responses and interventions emerge (Hawkins & Holden, 2013).

This conceptual framework (framing theory) informed the application of CDA, which systematically investigates hidden power relations and ideologies embedded in discourse and examines the social and material consequences of discourse (Johnson & McLean, 2020). CDA is concerned with exploring how ideology, power and stake are reproduced in language and is, therefore, well suited to an examination of media frames that encompass ideologies of the market, individual agency, and socio-structural inequalities (Sriwimon & Jimarkon Zilli, 2017). Efforts to frame particular issues and policies are political acts (Hawkins & Holden, 2013) and, as such, are rooted in power relations and competing interests. In this paper, we used framing theory to describe how the media focuses attention on particular issues around the advertising restrictions and places them within a specific field of meaning for the public.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

We conducted a qualitative thematic content analysis (Roberts & Pettigrew, 2007) of all media coverage in UK newspapers and trade press in the period surrounding the TfL advertising ban in order to identify and categorise arguments for and against it, followed by a document analysis (MacKenzie & Holden, 2017) focusing only on coverage opposing the ban in order to deconstruct the arguments made.

2.2. Search criteria

We searched English-language written, printed and online newspapers, and trade publications that were distributed in the UK or published on a UK-specific website. The search period of March 1, 2018 to May 31, 2019 was chosen to include coverage driven by: (i) the launch of the public consultation on the ban in May 2018; (ii) the confirmation of the ban in November 2018; and (iii) the implementation of the ban in February 2019. The Factiva database (https://professional.dowjones.com/factiva/) was searched for all articles published during this period. This database aggregates content from both licensed and free sources, including newspapers, journals, and more than 600 continuously updated newswires. To identify relevant articles, a search string was developed as follows: (“Transport for London” or “TfL” or “Mayor of London” or “Khan”) and (ban) and (advert*or ads) and (junk or HFSS) and (food* or beverage or drink*). The search terms where applied to the whole text (not just the headlines). To support triangulation, the database search was complemented by a more targeted manual search on: Google News; UK-specific newspapers and UK-specific editions of newspapers (Metro, Spiked, Huffington Post, Breitbart, The Spectator, iNews); trade press (Campaign Live, The Drum, Farmers Guardian, Eater London, and The Caterer); and news websites absent from Factiva. The particular metadata extracted were: publication date; publication name; headline; journalist's name (if given). These were extracted so that we could: ensure that the date of publication fell within our search period; accurately quote the publication name in our results; and ascertain whether the whole article was about the ban or a reference to the ban was made when reporting on something else.

2.3. Article selection

The search elicited a total of 343 articles, which were reviewed independently by two researchers (CC and VE) for relevance. Articles were excluded if they did not explicitly mention the ban. Articles published in non-news sections, including letters and opinion pages, were retained only if they reported on or referenced the views of prominent stakeholders and commentators (including celebrities, high-profile commercial spokespeople, and public sector leaders). Where discrepancies between the reviewers about whether to include an article occurred, articles were discussed with the wider group of researchers and consensus was reached. A total of 221 articles were retained, from which the following metadata were extracted: publication date; publication name; headline; journalist's name (if given). Among the 221 articles meeting the inclusion criteria, 69 were syndicated (i.e. similar article published in a different geographic zone or sister publication). In these instances, we always selected the longest version of the article and excluded its shorter, syndicated variations. A final sample of 152 articles was analysed (see appendix 1).

2.4. Analysis

2.4.1. Overview

The analysis was conducted in two stages. Firstly, a thematic content analysis was used to identify and categorise arguments for and against the restrictions. Secondly, a further document analysis, informed by CDA and Framing Theory principles, was applied solely to arguments against the restrictions. Our approach is outlined below.

2.4.2. Qualitative thematic content analysis

Articles were uploaded to NVivo 12 and initially subject to a thematic content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). First, a coding framework was developed by four researchers (CC, CT, VE, and SC) after they read and compared their views on a random subsample of 15 articles. Second, independent review and coding of the remaining 137 articles was split equally between the four researchers. Codes were refined iteratively, where needed, during analysis. The goal of the analysis was to identify and categorise all instances of a particular phenomenon (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005), in this case arguments for and against the restrictions (see appendix 2 for details of the codes and themes).

2.4.3. Document analysis

The second stage of the analysis focused solely on arguments against the ban identified in the initial thematic content analysis. In order to achieve this, we conducted a further document analysis informed by CDA principles, which focused on power relations, stake (interest), and influence (I. Fairclough & Fairclough, 2012; N. Fairclough, 2001). The document analysis sought to examine the ways in which concepts and arguments were constructed and how they were reproduced through discourse. As such, the discourse (i.e. the arguments presented) is examined in the data set as a whole; how it creates an effect, rather than a more interpretive or thematic approach which explicitly highlights and contrasts different perspectives (Savona, Thompson, Smith, & Cummins, 2020). We focused solely on arguments against the ban here because these are the subject of the ‘research problem’ we sought to address: media coverage of interventions affecting UCIs are often more aligned with the interests of industry than those of public health can influence public debate and understanding the pro-industry arguments deployed in these debates is key to anticipating and countering them (Mercille, 2017).

The document analysis of arguments against the ban was informed by our conceptual framework (Framing Theory - see section 1.3) and, thereby, CDA approaches to discourse (Carabine, 2001) which are underpinned by the following analytic steps:

-

1.

Identify the discursive strategies used (highlighting claims that are made to appear ‘true’ or ‘common sense’ to the reader)

-

2.

Ask how they work to persuade and create effects of ‘truth’?

-

3.

Look for ‘rupture and resilience’, complexity and counter-discourses (identifying contradictions and inconsistencies within those discursive strategies, thereby destabilising the associated effects of ‘truth’)

-

4.

Look for the absences and silences (identifying: relevant aspects of issues being discussed that are not mentioned; and debates that are not engaged with)

-

5.

Identify key strategies – both for organisation and interpretation (attempting to characterise the overall rhetorical approach taken in a text or groups of texts as laid out in steps 1–4) (Savona et al., 2020)

This analytic approach allowed us to explore how media frames were rhetorically constructed and justified.

3. Results

3.1. Data

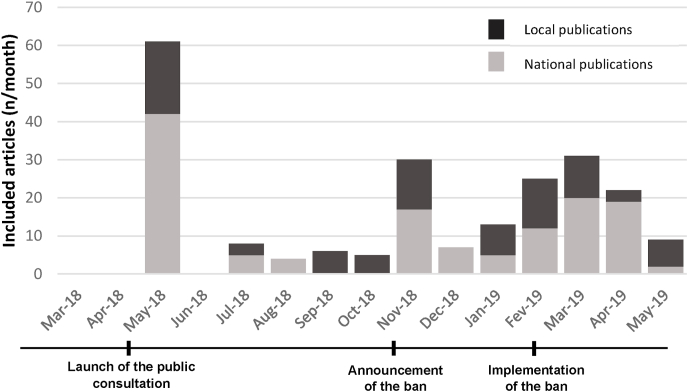

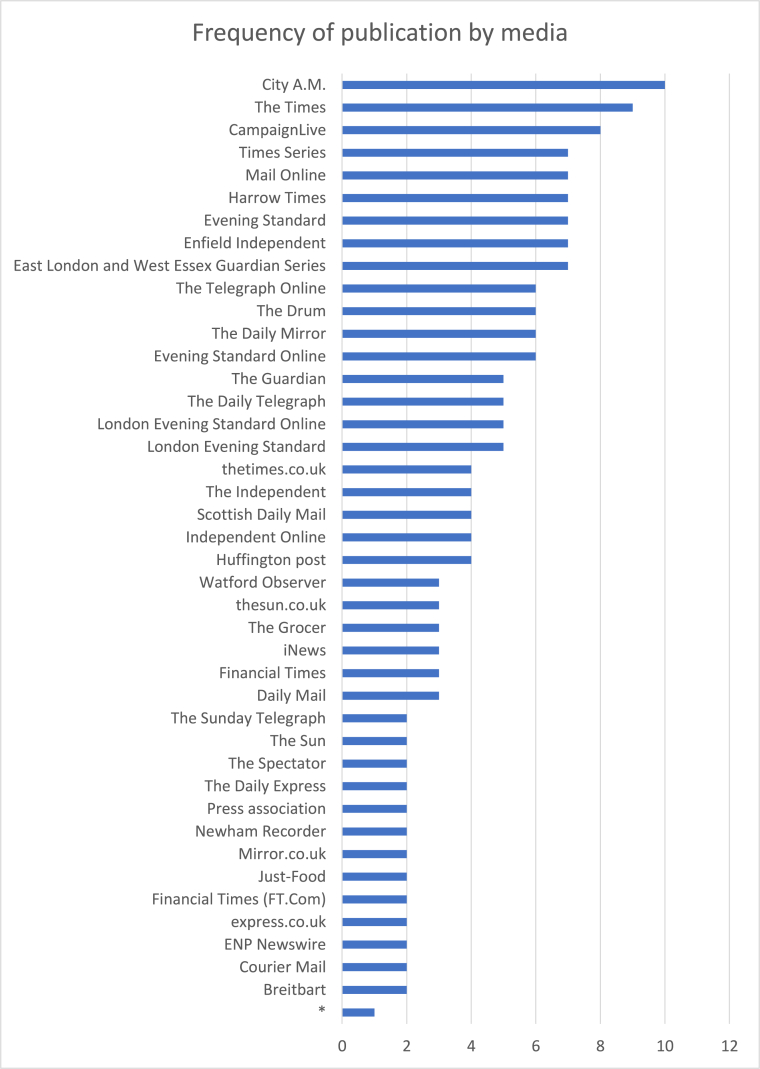

The 152 included articles were from 72 online or print newspapers and trade press publications (see appendix 1). Of these, 60% were published in national media and 40% in the local press (both London and other regions). Fig. 1 shows the number of articles over time and demonstrates peaks in the volume of coverage around launch of the public consultation (May 2018), announcement of the ban (November 2018), and its implementation (February 2019).

Fig. 1.

Coverage of the ban between March 2018 and May 2019.

In the subsections that follow, we first present the arguments made for the ban (which were identified using thematic content analysis), then the arguments made against the ban (also identified using thematic content analysis) which are explored in greater detail (using a document analysis). See appendix two for a breakdown of codes, themes and arguments.

3.2. Arguments for the ban

Arguments in favour of the ban were based on three broad assertions: the need to address health and social inequalities; childhood obesity as a public health crisis, and the economic burden obesity places on health services. Support for the ban was more prevalent in local (including London and other regions) than national publications. Local publications were more likely to present arguments that depicted the ban, and by association the Mayor and the Mayor's office, in a positive light. Childhood obesity is long-standing public health problem for local government in the UK (Public Health England, 2020) and the UK Government is committed to a range of local-level measures to tackle it (Cabinet Office, Department of Health and Social Care, & HM Treasury, 2017). The Mayor championing a local intervention to reduce childhood obesity was framed as a responsible and even moral undertaking. For example:

The proposals, unveiled by London Mayor Sadiq Khan, would also extend to the capital's buses and bus shelters, as well as the London Overground [trains]. Mr Khan said “bold steps” were needed to “do right” by young people, and to minimise the strain being placed on an under-pressure health service. (Birmingham Mail)

In light of these ‘bold steps’, depictions of the Mayor as a trail blazer and the ban as progressive were based on either assertions that other localities were adopting, or considering adopting, similar policies following the TfL example, and by contextualising the ban as part of a movement or trend in public health. TfL and the Mayor were this positioned as leading the way with the ban and making it possible and acceptable for other localities to implement similar measures.

Local authorities should be given greater powers to make it easier for them to impose restrictions on junk food advertising in their areas, a report has recommended … … The report from the health campaign groups Sustain and Food Active hailed the “belt and braces” ban on junk food adverts on London Underground, rail, tram and bus services introduced by the city's mayor, Sadiq Khan … … At a workshop on Wednesday, public health policy experts from the mayor's office will discuss the implications of the move with other local authorities, in the anticipation that other areas of the UK will follow London's lead … …. The London borough of Haringey and Edinburgh are both due to follow suit. (The Guardian)

This was nearly always linked to statistics on local health inequalities. Arguments for the ban were based almost exclusively on childhood obesity as a public health issue.

Justine Roberts, founder of Mumsnet, said parents would be grateful for measures that reduce “pester power” … … London has one of the highest child overweight and obesity rates in Europe, with 38.6% of children aged 10 and 11 across the capital overweight or obese. East London boroughs in particular have struggled to take on the problem. Shockingly, 44.3% of Year 6 pupils in Barking and Dagenham are classed as overweight or obese – the joint worst record in London. (Barking and Dagenham Post)

Arguments for the ban stressed the moral imperative to tackle childhood obesity and, typically, directly quoted Mayor Khan himself (as in the earlier extract from Birmingham Mail) and celebrities or other key public health figures who were supportive of the ban.

Mr Oliver [celebrity chef and restauranteur Jamie Oliver] took another swipe at the prime minister as he praised Mr Khan for “a massive and bold step forward for child health” … …. And Dame Sally Davies, the chief medical officer, said: “The evidence is clear that, although it is not a silver bullet, restricting the amount of junk food adverts children are exposed to will help reduce obesity.” (The Independent)

3.3. Arguments against the ban

Arguments against the ban converged on two central claims: that childhood obesity was not an ‘appropriate’ problem for TfL and the Mayor to try to tackle, and that an advertising ban was an ineffective way to address childhood obesity. The document analysis identified three main discursive approaches used to attempt to justify these claims:

-

i)

Identifying more ‘important’ or alternative priorities for action

-

ii)

Casting doubt on the evidence and science behind the ban and its implementation

-

iii)

Highlighting the potential costs of the ban

3.3.1. Challenging childhood obesity as a policy priority

TfL and the Mayor were extensively criticised for focusing on childhood obesity at the expense of what were described as more pressing issues, such as air pollution, smoking, alcohol consumption, body image, gambling, and law and order. By highlighting these potential alternatives, commentators framed the ban as ill-advised and irrelevant and the Mayor, by association, as out-of-touch with the problems faced by Londoners. The most prominent and widely cited alternative “pressing priority” (Breitbart) was that of youth violence and knife crime.

Other viewers were outraged that Sadiq's interview was focused on junk food ads, rather than the shocking knife crime rates in the capital city. One critic tweeted: “Sadiq Khan's interview …. about banning fast food adverts is not worthy as the main talking point of the interview. What about telling the nation what you plan to do to combat knife crime? … … I think that is more important than fast food?” (Daily Star)

In referencing violent crime and presenting these issues as a binary policy choice, they are pitted against each other with knife crime presented as more urgent and the relative importance of childhood obesity downplayed. This promotes the idea of a false dichotomy where only one issue can be dealt with any given time.

The portrayal of childhood obesity as the ‘wrong’ policy priority is presented alongside ad hominem attacks on the Mayor himself and as a synecdoche for City Hall in general, emphasising his championing of the ban and criticising him for not pursuing more important problems.

The Mayor of London was recently criticised for his ‘hypocritical’ ad policies. Previously, Sadiq Khan has banned advertisements for junk food on the Tube. Gambling advertisements however appear to have been allowed to double. (The Daily Mail)

This has the rhetorical effect of positioning the Mayor and City Hall in a double-bind, where there is no correct course of action. He is described as going too far by trying to address childhood obesity via the advertising ban. At the same time, it is also implied that he is a hypocrite for not going far enough by allowing advertisements for gambling, which are required not to be appealing to children (Committee of Advertising Practice, 2019), to double on public transport.

3.3.2. Questioning the scientific evidence

Undermining the scientific evidence was used as a way of challenging both the validity and authenticity of childhood obesity as a legitimate problem and the effectiveness of the ban as a solution. The extract below is an exemplar of this.

Supporters of the ban point to our supposed childhood obesity crisis as justification for such recklessness, but there is no solid evidence to show that a similar ban in Amsterdam has had any effect on their children's waistlines. (London Evening Standard)

Narratives around the (lack of) evidence implicitly overstate the purpose and scope of the ban and ignore the fact that most public health interventions only work for a proportion of people exposed to them and so must be part of a package of solutions. Where arguments in favour of the ban contextualised it as part of a wider movement, arguments against the ban considered it in isolation and, in doing so, judged it to be inadequate.

Stephen Woodford, chief executive of the Advertising Association, argued there was “no clear evidence” that the ban would solve the problem. He said: “We all want to see rates of childhood obesity dropping but believe there are far better ways to achieve this goal. (The Drum).

This kind of device is known as a nirvana fallacy, comparing the ban with unspecified and idealised alternatives and implying that a guaranteed solution to the problem of childhood obesity is possible. Potentially more suitable and effective ways of addressing the problem are alluded to – but rarely specified.

In terms of the science underpinning the implementation of the policy, the use of the NPM as the evidence-based tool to identify HFSS products is similarly represented as problematic. Instances where the NPM ‘doesn't work’ are highlighted and used as devices to argue against the policy.

[the] … marketing manager of Farmdrop, said: "[…] It's nonsense to score [jam, butter and bacon] product in its raw form. You eat them with other products. It's the basics of cooking.” (London Evening Standard)

The quote above is commenting on images of jam, butter and bacon (in an advertisement for Farmdrop) being deemed non-compliant by TfL and its application of the NPM. Focusing on specific foods that were banned – or not banned – was the most widely reported aspect of the policy. In some cases, HFSS foods were described affectionately as traditional and the banning of them as inappropriate and unfair.

In practice, the legislation will apply to all food or drink considered to be high in fat, salt or sugar (HFSS) — and that includes the kind of food your grandmother would have approved of, such as butter and jam (The Sun)

In fact, the policy did have a process to deal with condiments and cooking ingredients (like ketchup, mayonnaise and vegetable oil). Companies and brands could apply for an exception to the policy if they could demonstrate that their product does not contribute to childhood obesity (Exterion Media, 2018) (see Table 1). However, the exception process was not widely reported.

Criticisms of banning ‘good’ ingredients like these were juxtaposed against the failure of the NPM to restrict the advertisement of what is popularly considered to be ‘junk food’, such as fried chicken or specific fast-food brands.

And the points-based system [NPM] is product, not brand based, which means that McDonald's can't promote a Big Mac and fries but can [promote] its salads. But how many people associate McDonald's with salads? Isn't the likelihood that a family travelling on a London bus will glaze over the image of the salad and just see McDonald's famous golden arches, next to which is a sign directing them to the nearest McDonald's, where they will go to eat Big Macs? (The Drum)

3.3.3. Costs and unintended consequences of the ban

It was claimed that the ban would substantially reduce the TfL budget through loss of advertising revenue, with potential repercussions for commuters including fare increases and a deterioration in the quality of transport services.

Khan's plan is not just an idiotic idea but it will cost TFL (sic) millions in lost revenue. TFL (sic) needs more money. The system is running on a shoestring … A fast food ban simply won't help.” (Huffington Post)

Such claims were used as part of an overall framing of TfL as an under-funded and struggling public service being actively made worse as the result of an ill-advised policy.

Conservative critics in City Hall said the ban would cost a cash-strapped Transport for London (TfL) £13m a year and could mean there will be less money for infrastructure upgrades. Polling carried out by YouGov in November found that 62 per cent of Londoners would not support the ban if it meant an increase in fares. (City AM)

These arguments were used to frame the policy, and the Mayor himself, often via ad hominem attacks, as anti-business – with the ultimate victims being commuters and Londoners. Although fare increases in relation to the ban were never mentioned by the Mayor's office or TfL, speculation about them was used to evoke distrust and negative connotations about the ban. Critics predicted job losses and speculated on the potential for concurrent negative economic impacts of Brexit, thereby catastrophising the possible economic impact of the ban and employing a ‘slippery slope’ fallacy: positioning the ban as part of a suite of looming problems.

The result is that his [Sadiq Khan's] policy is likely to come into force in March next year, at exactly the same time as the Brexit impacts will hit, cutting industry (and TfL) revenues still further and potentially leading to job losses in London. (City AM)

Discussion

4.1. Summary of main findings

In this paper we identified the arguments made in favour of and against the TfL advertising restrictions in UK newspapers and trade press and explored how arguments against the restrictions were constructed and framed. We used Framing Theory (Chong & Druckman, 2007) to explore the mechanisms through which media coverage of interventions affecting UCIs are aligned with industry. Arguments in favour of the ban centred around health inequalities and the structural drivers of childhood obesity. Arguments against the ban were based on two central claims: that childhood obesity was not an appropriate policy priority; and that restricting advertising was not an appropriate way of addressing childhood obesity. These claims were justified by identifying alternative policy priorities, casting doubt on the science underpinning the ban, and speculating about the potential economic costs. In doing so, media frames opposing the ban drew on frames used by the unhealthy commodity industries more widely and took an implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) pro-industry stance. In the sections below we explore the implications and insights of these frames for the design and communication of public health interventions around unhealthy commodities.

4.2. Drawing from the unhealthy commodity industries’ playbook

Identifying and pushing for alternative policy priorities (in this case, priorities other than childhood obesity – such as knife crime) is a strategy long used by both the food, tobacco and alcohol industries (Bero, 2003; Brownell & Warner, 2009). Claims that the intervention will not work and demands for better, but unspecified, evidence and solutions are a parallel to those used by the tobacco (Ulucanlar, Fooks, Hatchard, & Gilmore, 2014) and alcohol (Hawkins, Holden, & McCambridge, 2012) industries. Dire predictions of the economic damage of interventions is a commonly used strategy (Bhattacharya, 2017) in order to argue for a ‘go slow’ approach to regulation (Warner, 2000). However, most public health interventions, in the longer term, are substantially cost saving and result in less pressure on services (Masters, Anwar, Collins, Cookson, & Capewell, 2017). Added to which, public health interventions that target industry tend not to result in long-term negative impacts for industry (Larcker, Ormazabala, & Taylor, 2011; Law et al., 2020).

What is notably absent from the arguments used against the ban is an acknowledgement of the finer details of the policy, including both the role of the exceptions process (see Table 1) and technical information on the NPM. This is a relevant aspect of the policy that is neither mentioned nor discussed in texts opposing the restriction – in effect a rhetorical silence (Savona et al., 2020). The use of tools, such as the NPM, underpinning interventions cannot be a panacea. They are works in progress that need to be updated, adapted and modified for specific uses and contexts. Well-designed interventions have processes to accommodate this (i.e. the exceptions process). A further silence, by omission, is the lack of acknowledgement that most public health interventions only work for a proportion of people exposed to them. This implicitly allows the purpose and scope of the restrictions to be overstated and facilitates a framing of them as inadequate to achieve the overstated aims.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

This paper adds to the evidence base on media framing of dietary public health interventions. As far as we are aware, it is the first analysis of its kind on the regulation of unhealthy food advertisements on public transport. We included all relevant articles in our analysis, rather than just a sample, and have explored how media coverage draws on frames used by UCIs and how they might be rebutted.

The search period of March 1, 2018 to May 31, 2019 stopped short of the updated guidance to advertisers issued by TfL in June 2019. While this represented a refinement of, rather than change to, the restrictions, it is possible that examining news coverage over this period would have indicated that media coverage in the preceding period informed the updated guidance.

The subject of analysis is news and trade press articles. The internal processes and conflicts over reporting health-related issues and the politics of editorial decisions in prominent London-based publications were likely relevant to how the ban was portrayed, but not something we explored. Additionally, we did not have the scope here to explore the differences in coverage between local papers in more deprived areas and those in local papers for the (wealthier and business centred) City of London. The focus of the analysis and the paper was on arguments against the ban. A valuable addition to findings presented in this paper would be a further analysis mapping the actors involved and quoted in the news coverage presenting arguments against the ban.

4.4. Implications for policy and practice – pre-empting and countering opposition

The restrictions were extensively and vigorously criticised. Such criticism can, and is indeed intended to, impact negatively on public perceptions and subsequently on public acceptability, which may result in a reduced impact for the intervention (Petticrew et al., 2017). Public acceptance of a specific policy solution is often a prerequisite for decision-makers to implement an evidence-based health policy. Media framing of health problems and solutions can play a key role in determining that acceptability and hence policy implementation (Hilton et al., 2019).

The stability of public attitudes towards public health interventions is little studied (Diepeveen et al., 2013) and careful consideration is required to anticipate and address aspects of interventions that may be easy targets for criticism (Willmott, Womack, Hollingworth, & Campbell, 2015). Hilton et al. (2019) stress that public health advocates need to clearly and consistently identify the multiple outcomes of proposed interventions. For the TfL advertising restrictions this includes lessening advertising of HFSS products and, at the same time, increasing space for advertising of healthier foods and encouraging brands to reformulate and produce healthier versions of their products. Currently, there is not a strong evidence base on how to counter industry frames. The findings of this study offer some insights as to how public health interventions may be opposed and how these oppositions could be negated. Public health advocates should anticipate the strategic simplification (in this case the nirvana fallacy of comparing the ban with idealised and unspecified alternatives) and counter this by focusing on the health-harming effects of the problem that the intervention is addressing (Hilton et al., 2019). Arguments in support of the restrictions did incorporate some of these aspects – stressing the harms of childhood obesity and presenting the ban as part of a suite of measures. For policymakers, child health, and particularly addressing childhood obesity, is a powerful justification for action (Keeble et al., 2020). Statutory regulation could help to achieve a reduction in exposure to HFSS advertising and subsequently improve the health of children (Mytton et al., 2020).

More neo-liberal approaches to governance that position public health issues, including obesity, largely in terms of lifestyle risk and individual responsibility can overshadow and undermine arguments for structural change and regulation in the wider public interest (Henderson, Coveney, Ward, & Taylor, 2009). Population interventions that position public health issues in terms of individual responsibility tend to require that individuals use a high level of agency to benefit. By contrast, population interventions that require individuals to use a low level of agency to benefit, like the TfL advertising restrictions, are more equitable and likely to be more effective. The amount of agency individuals must use to benefit from an intervention is a fundamental determinant of how, and for whom, it will work. High-agency population interventions may reinforce socioeconomic inequalities, while low-agency interventions are more likely to achieve the twin public health aims of preventing disease and minimising inequalities (Adams et al., 2016).

Authors’ contributions

All of the authors made substantial contributions to the design of the study and the analysis and interpretation of the findings. All authors contributed to the development of the research questions. CC led the article search, assisted by VE. SC and CT contributed to wider discussions to resolve discrepancies over article selection. CC, CT, VE and SC conducted the thematic content analysis. CT led the document analysis with contributions from all the authors. CT drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed successive drafts, provided substantive intellectual input, and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee (Application No. 16297/RR/11721). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare and full information on the funding of the study and for the authors is stated in the acknowledgements section.

Acknowledgements

This study is funded by the NIHR School for Public Health Research (SPHR) (Grant Reference Number PD-SPH-2015).

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Public Health Research is a partnership between the Universities of Sheffield; Bristol; Cambridge; Imperial; and University College London; The London School for Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM); LiLaC – a collaboration between the Universities of Liverpool and Lancaster; and Fuse - The Centre for Translational Research in Public Health, a collaboration between Newcastle, Durham, Northumbria, Sunderland and Teesside Universities.

CT is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East of England. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

JA, MW and TB are supported by the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge [grant number MC/UU/12015/6] and Centre for Diet and Activity Research (CEDAR), a UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC) Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Funding for CEDAR from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research [grant numbers ES/G007462/1 and MR/K023187/1], and the Wellcome Trust [grant number 087636/Z/08/Z], under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged.

FdV is partly funded by National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration West (NIHR ARC West) at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust.

AAL is a member of Fuse, the Centre for Translational Research in Public Health (www.fuse.ac.uk). Fuse is a Public Health Research Centre of Excellence funded by the five North East Universities of Durham, Newcastle, Northumbria, Sunderland and Teesside.

SC is funded by Health Data Research UK (HDR-UK). HDR-UK is an initiative funded by the UK Research and Innovation, Department of Health and Social Care (England) and the devolved administrations, and leading medical research charities.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of any of the above named funders. The funders had no role in the design of the study, or collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, or in the decision to publish, or in writing the manuscript.

Appendix 1.

* Barking & Dagenham Post, Birmingham Mail, Borehamwood Times, Coventry Telegraph, Croydon Advertiser, Daily Post, Daily Telegraph, dailystar. co.uk, Eastern Eye, Eater London, Euronews, Farmers Guardian, Farmers Weekly, Herald-Sun, Huddersfield Examiner, Investors Chronicle - Magazine and Web Content, Irish Daily Mail, Kantar Media – Precise, Lancashire Telegraph, Liverpool Echo, M2 Presswire, Manchester Evening News, Metro, News Shopper, Press Association National Newswire, Reuters Health E-Line, Reuters News, Spiked, sundaytimes. co.uk, The Advertiser, The Caterer, The Evening Chronicle Newcastle, The Gazette (Blackpool), The Herald, The independent, The Scotsman, The Sunday Independent, The Sunday Times, The Western Mail, thescottishsun. co.uk, WRBM Global Food, Yorkshire Evening Post, Yorkshire Post, Your Local Guardian.

Appendix 2.

Codes and themes.

| Global | Descriptors |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| Arguments for the ban | Arguments against the ban |

|---|---|

| Health and social inequalities | Childhood obesity not the ‘right’ problem |

| - Moral responsibility | - Trivial |

| Childhood obesity as a public health crisis | - Bigger problems |

| - Collective good | Advertising ban will not work/effect change |

| - Averting crisis/harm | - Irresponsible |

| - Proactive | - Costly |

| Economic burden on health services. | - Damaging |

| Major themes underpinning arguments |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

- Adams J., Ganiti E., White M. Socio-economic differences in outdoor food advertising in a city in Northern England. Public Health Nutrition. 2011;14(6):945–950. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010003332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams J., Mytton O., White M., Monsivais P. Why are some population interventions for diet and obesity more equitable and effective than others? The role of individual agency. PLoS Medicine. 2016;13(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams J., Tyrrell R., Adamson A.J., White M. Effect of restrictions on television food advertising to children on exposure to advertisements for ‘less healthy’ foods: Repeat cross-sectional study. PloS One. 2012;7(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Advertising Standards Authority . 2017. Food: HFSS nutrient profiling.https://www.asa.org.uk/advice-online/food-hfss-nutrient-profiling.html#:~:text=HFSS%20products%20are%20food%20and,as%20identified%20using%20nutrient%20profiling.&text=Points%20are%20awarded%20for%20'A,content%2C%20fibre%20and%20protein Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Bates B.C.L., Nicholson S., Page P., Prentice A., Steer T., Swan G. 2016. National diet and nutrition Survey results from Years 5 and 6 (combined) of the Rolling Programme. 2012/2013–2013/2014. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News . 2012. Scotch Whisky Association challenges Scotland's minimum alcohol price law.https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-18898024 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Bero L. Implications of the tobacco industry documents for public health and policy. Annual Review of Public Health. 2003;24:267–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.140813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya A. 2017. Why we don't need the alcohol industry for a strong economy.https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/why-we-dont-need-the-alcohol-industry-for-a-strong-economy/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell K.D., Warner K.E. The perils of ignoring history: Big tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is Big food? The Milbank Quarterly. 2009;87(1):259–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijzen M., Schuurman J., Bomhof E. Associations between children's television advertising exposure and their food consumption patterns: A household diary–survey study. Appetite. 2008;50(2–3):231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office, Department of Health and Social Care, & HM Treasury . 2017. Childhood obesity: A plan for action.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/childhood-obesity-a-plan-for-action/childhood-obesity-a-plan-for-action#fn:10 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns G., Angus K., Hastings G., Caraher M. Systematic reviews of the evidence on the nature, extent and effects of food marketing to children. A retrospective summary. Appetite. 2013;62:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron Wild T., Koziel J., Anderson-Baron J., Hathaway J., McCurdy A., Xu X.…Hyshka E. Media coverage of harm reduction, 2000-2016: A content analysis of tone, topics, and interventions in Canadian print news. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2019;1(205) doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabine J. Unmarried motherhood 1830-1990: A genealogical analysis. In: Wetherall M., Taylor S., editors. Discourse as data: A guide for analysis. Sage; London: 2001. pp. 267–310. [Google Scholar]

- Chong D., Druckman J.N. Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science. 2007;10:103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Committee of Advertising Practice . 2019. Regulatory statement: Gambling advertising guidance. Protecting children and young people. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . 2011. Nutrient profiling technical guidance.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216094/dh_123492.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Social Care . 2020. New obesity strategy unveiled as country urged to lose weight to beat coronavirus (COVID-19) and protect the NHS [Press release]https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-obesity-strategy-unveiled-as-country-urged-to-lose-weight-to-beat-coronavirus-covid-19-and-protect-the-nhs Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Diepeveen S., Ling T., Suhrcke M., Roland M., Marteau T.M. Public acceptability of government intervention to change health-related behaviours: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:756. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exterion Media . 2018. An Exterion media guide to the TfL HFSS policy for out-of-home advertising.https://outdoor.global.com/~/media/files/uk/brochures/hfss-brochure-exterion-media.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough N. The discourse of new labour: Critical discourse analysis. In: Wetherell M., Taylor S., Yates S.J., editors. Discourse as data: A guide for analysis. Sage and The Open University; London: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough I., Fairclough N. Routledge; London: 2012. Political discourse analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drink Federation . 2019. Advertising and Promotions - policy position.http://www.fdf.org.uk/keyissues_hw.aspx?issue=644 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith‐Emami S., Lobstein T. The impact of initiatives to limit the advertising of food and beverage products to children: A systematic review. Obesity Reviews. 2013;14:960–974. doi: 10.1111/obr.12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry E., Poirier K., Wilkinson T., Nhean S., Nyborn J., Siegel M. Alcohol advertising at boston subway stations: An assessment of exposure by race and socioeconomic status. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(10):1936–1941. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins B., Holden C. Framing the alcohol policy debate: Industry actors and the regulation of the UK beverage alcohol market. Critical Policy Studies. 2013;7(1):53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins B., Holden C., McCambridge J. Alcohol industry influence on UK alcohol policy: A new research agenda for public health. Critical Public Health. 2012;22(3):297–305. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2012.658027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J., Coveney J., Ward P., Taylor A. Governing childhood obesity: Framing regulation of fast food advertising in the Australian print media. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69:1402–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton S., Buckton C.H., Patterson C., Katikireddi S.V., Lloyd-Williams F., Hyseni L.…Capewell S. Following in the footsteps of tobacco and alcohol? Stakeholder discourse in UK newspaper coverage of the soft drinks industry levy. Public Health Nutrition. 2019;22(12):2317–2328. doi: 10.1017/S1368980019000739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H.F., Shannon S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings A., Welch A., van Sluijs E.M., Griffin S.J., Cassidy A. Diet quality is independently associated with weight status in children aged 9–10 years. Journal of Nutrition. 2011;141(3):453–459. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.131441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.N.P., McLean E. Critical discourse analysis. In: Kobayashi A., editor. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography. 2nd ed. Elsevier; Kingston: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Katikireddi S.V., Hilton S. How did policy actors use mass media to influence the scottish alcohol minimum unit pricing debate? Comparative analysis of newspapers, evidence submissions and interviews. Drugs. 2015;22:125–134. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2014.977228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeble M., Burgoine T., White M., Summerbell C., Cummins S., Adams J. Health and Place, In Press; 2020. Planning and public health professionals' experiences of using the planning system to regulate hot food takeaway outlets in England: A qualitative study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larcker D.F., Ormazabala G., Taylor D.L. The market reaction to corporate governance regulation. Journal of Financial Economics. 2011;101(2):431–448. [Google Scholar]

- Law C., Cornelsen L., Adams J., Penney T., Rutter H., White M. An analysis of the stock market reaction to the announcements of the UK Soft Drinks Industry Levy. Economics and Human Biology. 2020;38 doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2019.100834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucan S.C., Maroko A.R., Sanon O.C., Schechter C.B. Unhealthful food-and-beverage advertising in subway stations: Targeted marketing, vulnerable groups, dietary intake, and poor health. Journal of Urban Health. 2017;94:220–232. doi: 10.1007/s11524-016-0127-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie R., Holden C. Analysing corporate documents. In: Lee K., Hawkins B., editors. Researching corporations and Global health governance: An interdisciplinary guide. Rowman and Littlefield; London: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Masters R., Anwar E., Collins B., Cookson R., Capewell S. Return on investment of public health interventions: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2017;71:827–834. doi: 10.1136/jech-2016-208141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor of London . Transport for London. 2018. Annual report and statement of accounts 2017/18. [Google Scholar]

- Mayor of London. Transport for London annual advertising report 2017/18.

- Mercille J. Media coverage of alcohol issues: A critical political economy framework—a case study from Ireland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017;14(6) doi: 10.3390/ijerph14060650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mytton O.T., Boyland E., Adams J., Collins B., O'Connell M., Russell S.J. The potential health impact of restricting less-healthy food and beverage advertising on UK television between 05.30 and 21.00 hours: A modelling study. PLoS Medicine. 2020;17(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS Digital . 2020. National child Measurement Programme, England 2019/20 School Year.https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/national-child-measurement-programme/2019-20-school-year Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z., Kosicki G. Framing and the understanding of citizenship. In: Dunwoody S., Backer L., McLeod D., Kosicki G., editors. The evolution of key mass communication concepts. Hampton Press; Cresskill: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew M., Vittal Katikireddi S., Knai C., Cassidy R., Maani Hessari N., Thomas J. ‘Nothing can be done until everything is done’: The use of complexity arguments by food, beverage, alcohol and gambling industries. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2017;71(11):1078–1083. doi: 10.1136/jech-2017-209710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England . 2020. Executive summary: Learning from local authorities with downward trends in childhood obesity.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-child-measurement-programme-childhood-obesity/executive-summary-learning-from-local-authorities-with-downward-trends-in-childhood-obesity#fn:1 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ries N.M., Rachul C., Caulfied T. Newspaper reporting on legislative and policy interventions to address obesity: United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2011;32:73–90. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2010.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M., Pettigrew S. A thematic content analysis of children's food advertising. International Journal of Advertising. 2007;26(3):357–367. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo K., Sahoo B., Kumar Choudhury A., Yasin Sofi N., Kumar R., Singh Bhadoria A. Childhood obesity: Causes and consequences. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2015;4(2):187–192. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.154628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savona N., Thompson C., Smith D., Cummins S. ‘Complexity’ as a rhetorical smokescreen for UK public health inaction on diet. Critical Public Health. 2020:1–11. April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schön D., Rein M. Frame-critical policy analysis and frame-reflective policy practice. Knowledge and Policy. 1996;9(1):85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Sriwimon L., Jimarkon Zilli P. Applying Critical Discourse Analysis as a conceptual framework for investigating gender stereotypes in political media discourse. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences. 2017;38(2):136–142. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckler D., McKee M., Ebrahim S., Basu S. Manufacturing epidemics: The role of global producers in increased consumption of unhealthy commodities including processed foods, alcohol, and tobacco. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The PLoS Medicine Editors Editorial. Big food: The food industry is ripe for scrutiny. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulucanlar S., Fooks G.J., Hatchard J.L., Gilmore A.B. Representation and misrepresentation of scientific evidence in contemporary tobacco regulation: A review of tobacco industry submissions to the UK government consultation on standardised packaging. PLoS Medicine. 2014;11(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallance K., Vincent A., Schoueri-Mychasiw N., Stockwell T., Hammond D., Greenfield T.K.…Hobin E. News media and the influence of the alcohol industry: An analysis of media coverage of alcohol warning labels with a cancer message in Canada and Ireland. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2020;81(2):273–283. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2020.81.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield M., Mcleod K., Smith K.C. Individual versus corporate responsibility for smoking-related illness: Australian press coverage of the rolah McCabe trial. Health Promotion International. 2003;18(4):297–305. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dag413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner K.E. The economics of tobacco: Myths and realities. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:78–89. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerasinghe A., Schoueri-Mychasiw N., Vallance K., Stockwell T., Hammond D., McGavock J.…Hobin E. Improving knowledge that alcohol can cause cancer is associated with consumer support for alcohol policies: Findings from a real-world alcohol labelling study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(2) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17020398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weishaar H., Dorfman L., Freudenberg N., Hawkins B., Smith K., Razum O. Why media representations of corporations matter for public health policy: A scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3594-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen R., Harrold J., Child S., Halford J., Boyland E. Children's exposure to food advertising: The impact of statutory restrictions. Health Promotion International. 2017;34(2):227–235. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dax044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmott M., Womack J., Hollingworth W., Campbell R. Making the case for investment in public health: Experiences of directors of public health in English local government. Journal of Public Health. 2015;38:237–242. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]