Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cell development is a multistep process that requires a variety of signals and transcription factors. The lack of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) kinase severely impairs NK cell development in mice. mTOR binds to Raptor and Rictor to form two complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2, respectively. How mTOR and its two complexes regulate NK cell development is not fully understood. Here, we developed two methods to inactivate mTOR, Raptor, or Rictor in early stage NK cells (using CD122-Cre) or in late-stage NK cells (using Ncr1-CreTg). First, we found that when mTOR was deleted by CD122-Cre during and after NK cell commitment, NK cell development was severely impaired, while Ncr1-CreTg mediated mTOR deletion slightly affected NK cell terminal differentiation, suggesting that mTOR is essential for early NK cell differentiation. Second, we found that CD122-mediated deletion of Raptor significantly limited the differentiation of CD27+CD11b− immature NK (iNK) cell into mature NK cells. In contrast, the absence of Rictor significantly interfered with the differentiation of CD27−CD11b− early iNK cells. Third, Ncr1-mediated deletion of Raptor, rather than Rictor, moderately affected NK cell terminal differentiation. In terms of mechanism, mTORC1 mainly promotes the expression of NK cell-specific transcription factor E4 promoter-binding protein 4 (E4BP4), while both mTORC1 and mTORC2 can enhance the expression of T-bet. Therefore, mTORC1 and mTORC2 subtly coordinate NK cell development by differentially inducing E4BP4 and T-bet.

Subject terms: Immunology, Cell death and immune response

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells are derived from hematopoietic stem cells through multiple developmental stages, including common lymphoid progenitor cells (CLP), NK progenitor cells (NKp), immature NK (iNK) cells, and mature NK (mNK) cells. The expression of IL-15/IL-2 receptor β chain (CD122) determines the commitment of CLP to NK cell lineage. Along with acquisition of NK1.1, mouse NKp differentiates into iNK and eventually mNK. The expression of NKp46 encoded by the gene Ncr1 occurs at the stage of iNK cells [1], and Ncr1-Cre mice have widely been used as tools for genetic study of gene regulation in NK cells. Based on the expression of CD27 and CD11b, iNK cells can be further defined as CD27−CD11b− (DN, here refers to early stage of iNK) and CD27+CD11b− subsets, whereas mNK cells include CD27+CD11b+ and CD27−CD11b+ subsets [2].

NK cell differentiation is driven by many transcription factors, such as E4 promoter-binding protein 4 (E4BP4), Eomesodermin (Eomes), and T-bet [3]. The germline deletion of E4BP4 leads to no detectable NK cells in mice [4, 5], but Ncr1-Cre mediated deletion of E4BP4 at the late stage has no effect on NK cell development [6], suggesting a stage-specific role of E4BP4 on NK cell differentiation. The germline deletion of two T-box family transcription factors, Eomes or T-bet, severely hinders NK cell development [7–9]. We and other groups previously proposed that Eomes was likely regulated by E4BP4 and can directly promote the expression of IL-15 receptor β (CD122) through binding to the promoter of CD122 [10]. How the upstream signaling regulates these transcription factors remains to be further investigated.

NK cell development is mainly dependent on IL-15 receptor signaling [11, 12]. Engagement of the IL-15 receptor on NK cells activates two downstream signaling pathways, JAK-STAT and PI3K-mTOR pathway [13, 14]. The deficiency of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) kinase severely impairs NK cell development in mice [15]. mTOR binds to Raptor and Rictor to form two complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2, respectively. Using gene-targeting technique based on Ncr1-Cre mice, recent studies have demonstrated the different roles of mTORC1 and mTORC2 in terminal NK cell maturation [16, 17]. However, it is not clear whether these two complexes regulate early NK cell development before NK cells acquire NKp46.

To investigate the role of mTOR and its complexes in early NK cell development, we use newly generated CD122Cre/+ mice to delete mTOR, Raptor, or Rictor. In CD122Cre/+ mice, Cre begins to be expressed during and after NK cell commitment. We reveal that when mTOR is deleted by CD122-Cre, the terminal development of NK cells is severely impaired, and when mTOR is deleted by Ncr1-Cre, the terminal development of NK cells is moderately impaired, suggesting that mTOR is indispensable in the differentiation of early NK cells and also impacts late development of NK cells. CD122-mediated Raptor deletion markedly delays the differentiation of CD27+CD11b− iNK into mNK cells, while Rictor deletion significantly disturbs the differentiation of CD27−CD11b− early iNK cells into cells that have become CD27+CD11b− iNK or mNK cells. Mechanistically, mTORC1 and mTORC2 spatiotemporally coordinate early NK cell development through differentially inducing E4BP4 and T-bet.

Results

mTOR deletion hinders the differentiation of immature NK cells

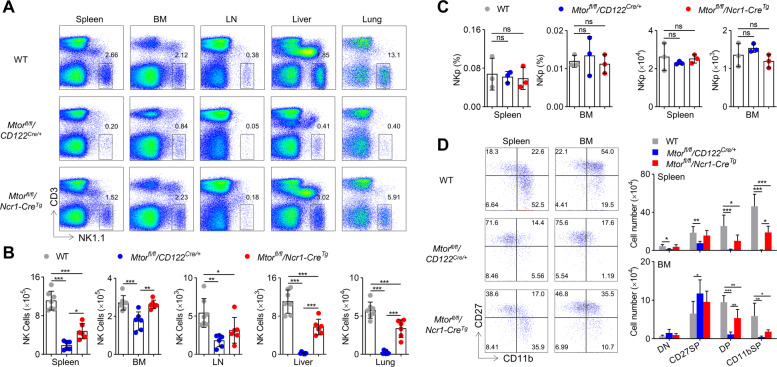

In order to understand the stage-specific role of mTOR in NK cell development before and after NKp46 expression, we generated two mTOR-deficient mouse models, Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ and Mtorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg, respectively. In Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice, Mtor begins to be deleted when NKp cells acquire CD122. In contrast, mTOR expression was deleted during the terminal stage of NK cell development after acquisition of NKp46 in Mtorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg mice. Given that NK cells in CD122Cre/+, Ncr1-CreTg, and Mtorfl/fl mice had intact NK cell development, Mtorfl/fl mice were selected as controls. We initially found that the proportion of NK cells (CD3−NK1.1+) was greatly decreased in the tissues and organs that were examined, including spleen, BM, lymph nodes, liver and lungs, of the Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice (Fig. 1A, B). Consistently, the numbers of NK cells were also greatly reduced in these mTOR-deficient mice. In contrast to the severe impairment of NK cell development in Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice, NK cell percentage and absolute number were significantly affected but to a lesser extent in Mtorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg mice (Fig. 1A, B). These data indicate that mTOR kinase not only regulates the differentiation of NK cells after NKp46 expression, but also plays a critical role in NK cell development before NKp46 acquisition.

Fig. 1. mTOR deletion hinders the differentiation of immature NK cells.

Flow cytometric analysis (A) and the numbers (B) of NK cells (CD3−NK1.1+) in the spleen, bone marrow (BM), lymph nodes (LN), livers, and lungs of WT (n = 7), Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 6), and Mtorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg (n = 6) mice are illustrated. C The percentage (left) and the number (right) of NK progenitor (CD3−CD122+NK1.1−) in spleen and bone marrow of WT, Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ and Mtorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg mice are illustrated (n = 3/genotype). D Flow cytometry analysis of the CD27 and CD11b expression on gated NK cells from spleen and BM of WT (n = 7), Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 5), and Mtorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg (n = 4) mice (left) are illustrated. The numbers of each subset were quantified (right). DN (CD27−CD11b−), CD27 SP (CD27+CD11b−), DP (CD27+CD11b+), and CD11b SP (CD27−CD11b+) cells. For the bar graphs, each dot represents one mouse and the data represent at least three independent experiments, and one (C, D) or two-pooled (B) independent experiments are illustrated. Data are indicated as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. ns not significant.

We further explored which stage(s) was affected by mTOR deletion in mice. CD122-Cre-mediated deletion of mTOR did not significantly reduces the proportion and number of NK cell progenitors (Fig. 1C). In Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice, the proportion of CD27+CD11b− cells at the iNK stage was greatly increased, while mNK cells (including CD27+CD11b+ and CD27−CD11b+) were rarely detectable in the spleen and BM. In line with published data [15], the transition of iNK cells to mNK cells in Mtorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg mice was also impaired, albeit to a lesser extent to that observed in Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that mTOR expression in early differentiation of NK cells is necessary for the iNK cells transition into mNK cells.

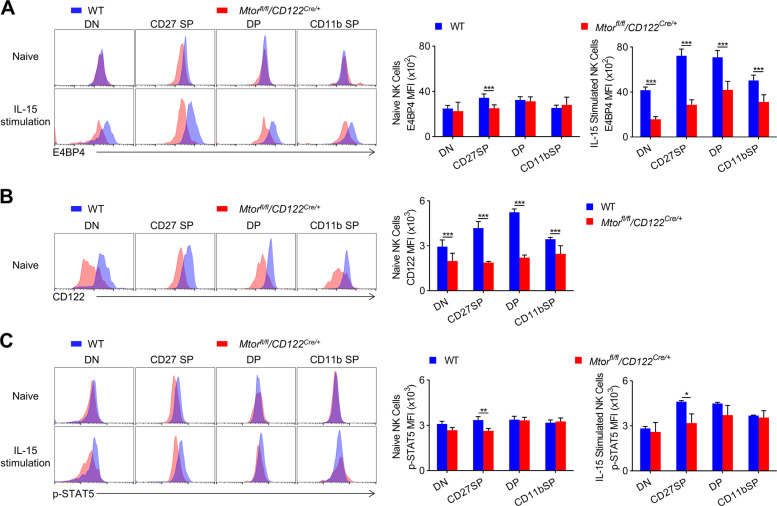

mTOR promotes E4BP4 expression and IL-15 responsiveness

E4BP4 is a key transcription factor in NK cell development and is mainly induced by IL-15. We thus examined this transcription factor in NK cells stimulated with IL-15 or not. Intracellular staining revealed a significant decrease in E4BP4 in the subsets of NK cells of Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice after IL-15 stimulation (Fig. 2A). In parallel, the expression of CD122 on the mTOR-deficient NK cells was significantly reduced (Fig. 2B). Consistent with published data [15], we noticed that the STAT5 phosphorylation of CD27+CD11b− iNK cells was decreased in Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. The induction of E4BP4 by IL-15 requires mTOR.

A Representative overlaid histograms demonstrate the E4BP4 expression level of naïve and IL-15 complex (50 ng/ml) stimulated NK cell subsets in the spleens from WT (n = 6) and Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 9) mice (left). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was quantified (right). B Representative overlaid histograms demonstrate CD122 expression level (left) of gated NK cell subsets in the spleen from WT (n = 12) and Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 8) mice. The MFI was quantified (right). C Representative overlaid histograms show the phosphorylation level of STAT5 in naive and IL-15 complex (50 ng/ml) stimulated NK cell subsets in the spleen from WT (n = 4) and Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 5) mice (left). The MFI was quantified (right). The data represent four independent experiments, and one (A, C) or two-pooled (B) independent experiments are shown. Data are indicated as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was calculated using unpaired Student’s t tests (two tailed). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

To further confirm whether the failure of NK cells to induce E4BP4 would lead to impaired NK cell development, Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ BM cells were infected with a retrovirus expressing E4BP4. After BM reconstitution, we found that the exogenous expression of E4BP4 significantly rescued the impaired development of NK cells from Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice (Fig. 3A, B). Notably, the ectopic expression of E4BP4 partially alleviated the developmental arrest in CD27+CD11b− stage (Fig. 3C), and therefore, it significantly improved the expression level of Eomes and CD122 on Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ NK cells (Fig. 3D). Thus, the expression of mTOR in early NK cells is critical for induction of E4BP4 and maintenance of IL-15 responsiveness.

Fig. 3. Ectopic expression of E4BP4 significantly rescues mTOR-deficient NK cell development.

A, B WT and Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice were treated with 5-FU for 4 days, and bone marrow cells were collected for spin infection with MSCV retrovirus that encoded control GFP or E4BP4. The infected BM cells were then transferred into RAG1−/−γc− mice. After 6 weeks, NK cells (CD3−NK1.1+) that were gated GFP+ cells in the spleen (A) and bone marrow (B) were analyzed by flow cytometry. The representative flow cytometric profiles (left) and the percentage of NK cells (right) are illustrated (A, n = 2–4/genotype; B, n = 6–7/genotype). C The percentages of NK cell subsets in spleen (left) and bone marrow (right) from the indicated mice were quantified (n = 3–7/genotype). D The MFIs of Eomes (left) or CD122 (right) of NK cell subsets in spleen from the indicated mice were quantified (left panel, n = 3–4/genotype; right panel, n = 3–7/genotype). One ((A, D), left panel) or two-pooled ((B–D), right panel) independent experiments are shown. The data represent at least three independent experiments. Data are indicated as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was calculated using two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

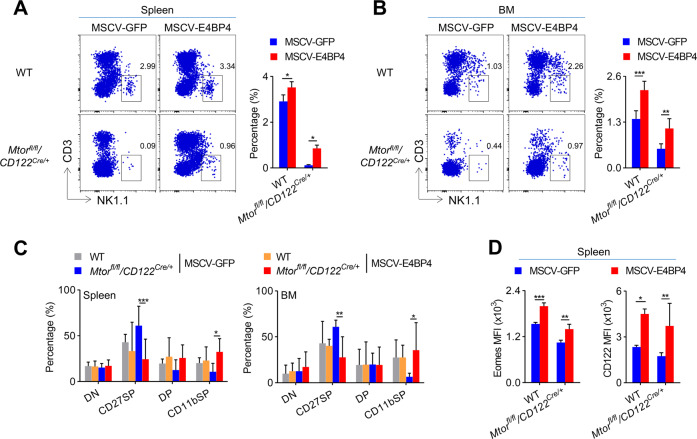

mTOR regulates NK cell development through mTORC1 and mTORC2

To dissect which mTOR complexes are primarily required for iNK cell transition to mNK cells, Rptorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+and Rictorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice were generated, respectively, to delete Raptor and Rictor. We noticed that CD122-Cre-mediated Raptor deletion significantly reduced the percentage of and the absolute number of NK cells in spleen, lymph nodes, liver, and lungs, but not BM. Interestingly, Rictor deficiency led to a decrease in the proportion and number of NK cells in the bone marrow as well as the spleen, liver, and lungs. The decrease of NK cells in the bone marrow associated with Rictor deficiency was to 27% of the WT control (Fig. 4A, B). Therefore, NK cell development requires both mTORC1 and mTORC2.

Fig. 4. mTORC1 and mTORC2 differentially dictate NK cell differentiation.

Representative flow cytometric profiles (A) and the absolute number (B) of NK cells (CD3−NK1.1+) in the spleen, bone marrow (BM), lymph nodes (LN), livers, and lungs of WT (n = 7), Rptorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 5), Rictorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 5), and Rptorfl/fl/Rictorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 4) mice are illustrated. Representative flow cytometric profiles (C) and the absolute number (D) of NK cells (CD3−NK1.1+) in the spleen and bone marrow (BM) of WT (n = 5), Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 4), and Rptorfl/fl/Rictorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 4) mice are illustrated. Representative flow cytometric profiles (E) and enumeration (F) of each subset of NK cell subsets on gated CD3−NK1.1+ splenocyte and bone marrow cells from the WT (n = 7), Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 6), and Rptorfl/fl/Rictorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 6) mice are illustrated. Representative flow cytometric profiles (G) and enumeration (H) of NK cell subsets in the spleen and BM from the WT (n = 7), Rptorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 6), and Rictorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 6) mice are illustrated. I The percentages of development-related NK cell receptors on CD3−NK1.1+ cells in the spleen from the WT (n = 4), Rptorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 3), and Rictorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 3) mice are illustrated. DN (CD27−CD11b−), CD27 SP (CD27+CD11b−), DP (CD27+CD11b+), and CD11b SP (CD27−CD11b+) cells. For the bar graphs, each dot represents one mouse. The data represent at least three independent experiments, and one (D, I) or two-pooled (B, F, H) independent experiments are illustrated. Data are indicated as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. ns not significant.

To rule out the possibility of mTOR signaling independent of mTORC1/mTORC2 [18], we compared the phenotype of NK cells in Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice with that in Rptorfl/fl/Rictorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice. Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ and Rptorfl/fl/Rictorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice showed similar reductions in NK cells (Fig. 4C, D). We also found that the developmental arrest of CD27+CD11b− NK cells was also comparable between the two genotypes (Fig. 4E, F). Therefore, NK cell development is regulated by Raptor- and Rictor-dependent mTOR signaling.

mTORC1 and mTORC2 differentially dictate NK cell differentiation

We then analyzed whether Raptor deficiency or Rictor deficiency differed in their effects on NK cell differentiation. Through in-depth analysis of NK cell subsets, we found that Raptor deficiency resulted in the blockage of most of the NK cells at the CD27+CD11b− iNK stage, and therefore, the number of mNK cells (including CD27+CD11b+ and CD27−CD11b+) decreased greatly (Fig. 4G, H). Unlike Raptor deletion, the lack of Rictor altered NK cell subpopulation to a lesser extent (Fig. 4G). However, we observed that Rictor deletion resulted in a dramatic reduction of the numbers of CD27+CD11b− iNK and mNK cells (Fig. 4H). Based on the numbers of NK cell subsets in the developmental stages, we suggest that Rictor deficiency may disturb the differentiation of CD27−CD11b− early iNK cells into CD27+CD11b− iNK and mNK cells. Collectively, mTORC1 and mTORC2 are different in regulation of the development of NK cells, and mTORC2 seems to regulate NK cell development earlier than mTORC1.

The NK cell receptor profile further supported the developmental disorder observed in Rptorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice and Rictorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice. CD117 and CD127 are two early NK cell markers. We found that the proportion of CD127+ NK cells increased significantly in both genotypes, but a higher proportion of CD117+ NK cells were observed only in Rictorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice, suggesting that mTORC2 may affect the development of NK cells earlier than mTORC1. In both Raptor and Rictor depleted genotypes, the Ly49 family receptors (except Ly49A) and KLRG1 were less expressed in most NK cells, which, respectively, represented NK cell maturation (Fig. 4I).

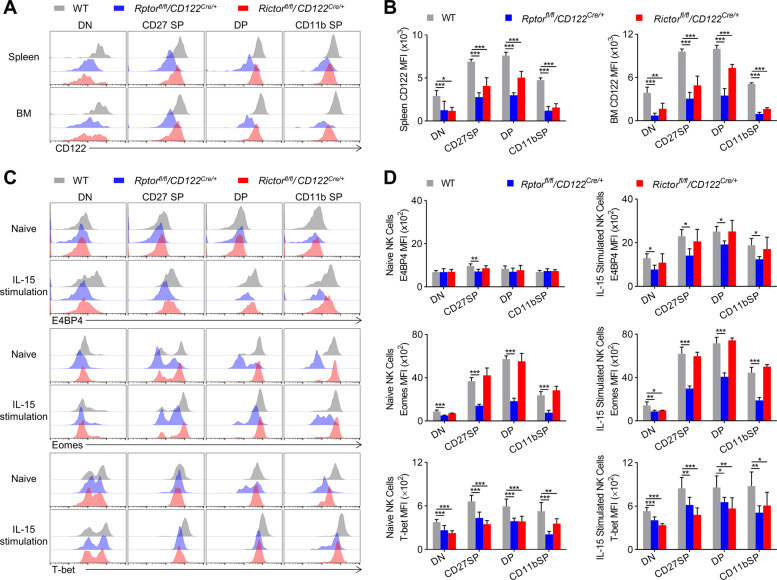

mTORC1 and mTORC2 have different regulatory effects on E4BP4 and T-bet

Since the expression of E4BP4 and Eomes triggered by IL-15 is important for maintaining IL-15 responsiveness, we detected the surface expression of CD122, which determines the sensitivity of NK cells to IL-15. Mice lacking Raptor or Rictor showed a significant reduction in CD122 (Fig. 5A, B). In order to further investigate whether the two mTOR complexes are different in regulating transcription factor expression and subsequent iNK cell differentiation into mNK cells, we examined the amount of E4BP4, Eomes, and T-bet in each subset of splenic NK cells. In the resting state, we noticed that Eomes and T-bet were less expressed in Rptorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ NK cells than WT (Fig. 5C, D). In contrast, Rictor deficiency could only lower the expression of T-bet compared to both transcription factors expressed in WT (Fig. 5C, D). In addition, WT NK cells could induce E4BP4, Eomes, and T-bet after IL-15 stimulation, while Raptor-deficient NK cells failed to act sufficiently. Unexpectedly, Rictor deficiency only affected the expression level of T-bet after IL-15 stimulation (Fig. 5C, D). These data suggest that mTORC1 and mTORC2 play different roles in early NK cell differentiation, most likely by inducing E4BP4 and T-bet.

Fig. 5. mTORC1 and mTORC2 have different regulatory effects on E4BP4 and T-bet.

Representative overlaid histograms demonstrate CD122 expression level (A) by gated NK cells in the spleen and BM from WT (n = 6), Rptorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 4), and Rictorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ (n = 4) mice, and the MFIs were quantified (B). C, D Representative overlaid histograms indicate the E4BP4, Eomes, and T-bet expression levels of naive or IL-15 complex (50 ng/ml) stimulated NK cells in the spleen from WT, Rptorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+, and Rictorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice (C), and the MFIs (D) (top panel, n = 3–5/genotype; middle panel, n = 3–6/genotype; bottom panel, n = 5–8/genotype). All data represent four independent experiments, and one ((B); top and middle panels of (D)) or two-pooled (bottom panel of (D)) independent experiments are illustrated. All data are indicated as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

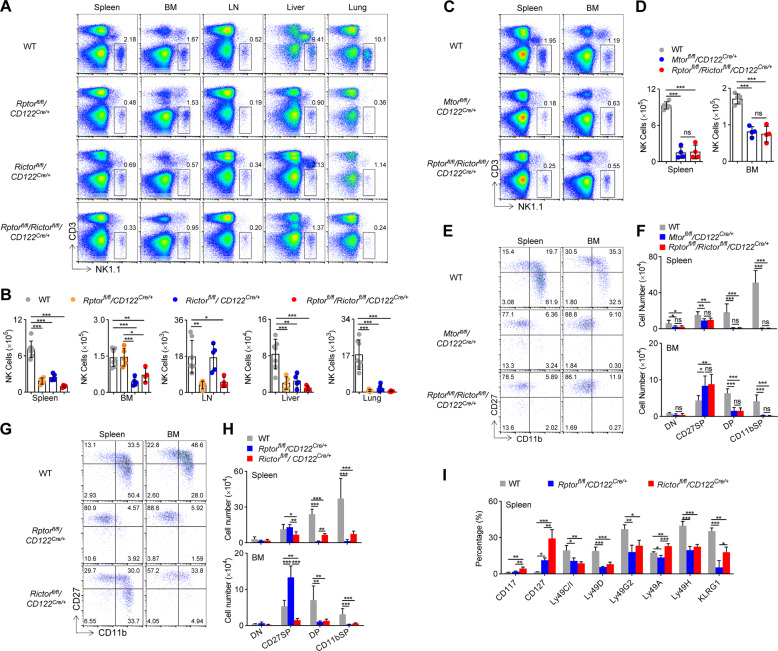

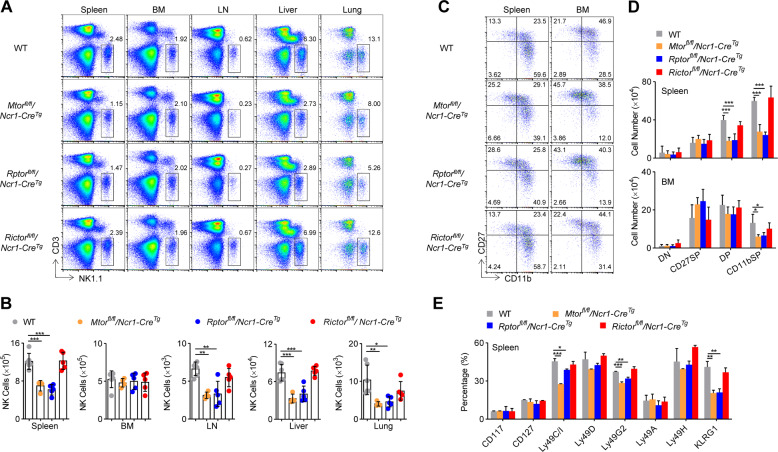

Terminal differentiation of NK cells requires mTORC1 rather than mTORC2

The above data revealed the divergent roles of mTORC1 and mTORC2 in the early stage development of NK cells. To investigate whether these two mTOR complexes were required for terminal maturation of NK cells, we generated Rptorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg and Rictorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg mice, in which Raptor and Rictor were deleted after expression of NKp46 on NK cells. It was noted that the proportion and number of NK cells were significantly reduced in the spleen, lymph nodes, lung, livers, but not BM, from Rptorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg mice, to a similar degree to Mtorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg (Fig. 6A, B). However, Rictor deficiency did not alter NK cell populations in any of the peripheral organs and tissues (Fig. 6A, B). The deficiency of mTOR or Raptor but not Rictor, significantly decreased the percentages and numbers of mNK cells subsets (CD27+CD11b+ and CD27−CD11b+) (Fig. 6C, D). In addition, we observed that KLRG1-positive or part of Ly49 family-positive NK cells were also less present in Mtorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg and Rptorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg mice (Fig. 6E). Thus, mTORC1 is also necessary for the terminal differentiation of NK cells.

Fig. 6. Terminal differentiation of NK cells requires mTORC1 rather than mTORC2.

Representative flow cytometric profiles (A) and the absolute number (B) of NK cells in the spleen, bone marrow (BM), lymph nodes (LN), livers, and lungs from WT (n = 6), Mtorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg (n = 4), Rptorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg (n = 5), and Rictorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg (n = 5) mice are illustrated. Representative flow cytometric profiles (C) and enumeration (D) of NK cell subsets in the spleen and BM from the WT (n = 6), Mtorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg (n = 4), Rptorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg (n = 5), and Rictorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg (n = 5) mice are illustrated. E Flow cytometry analysis of development-related NK cell receptors of CD3−NK1.1+ cells in the spleen is illustrated (n = 2–3/genotype). For the bar graphs, each dot represents one mouse. All data represent three independent experiments, and one (E) or two-pooled (B, D) independent experiments are illustrated. All data are indicated as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

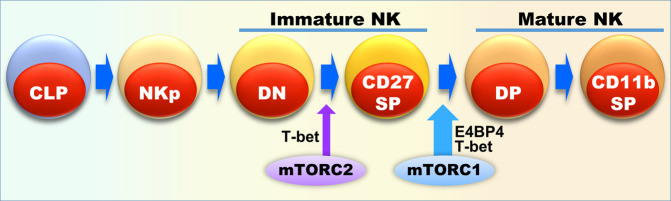

In summary, our data indicate that mTORC1 is essential for early and late-stage development of NK cells most likely by regulating E4BP4 and T-bet, while mTORC2 is only necessary for very early NK cell development through regulating T-bet, as depicted in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. A schematic for mTORC1 and mTORC2 spatiotemporal coordination of NK cell development by regulating E4BP4 and T-bet expression.

Mature NK cells (mNK) are derived from common lymphoid progenitor cells (CLP) through multiple developmental stages, including NK progenitor cells (NKp) and immature NK cells (iNK). Immature NK cells can be further defined into CD27−CD11b− (DN) and CD27+CD11b− (CD27 SP) subsets, whereas mature NK cells include CD27+CD11b+ (DP) and CD27−CD11b+ (CD11b SP) subsets. mTORC1 is essential for the progression of iNK to mNK, while mTORC2 is required for early iNK transition. In terms of mechanisms, mTORC1 mainly promotes immature NK cell transition by inducing the expression of the master transcription factor E4BP4, while mTORC2 promotes T-bet expression along with mTORC1.

Discussion

NK cell development is a sequential progress that is strictly dependent on the activation of mTOR kinase by IL-15 [11, 12]. How mTOR spatiotemporally regulates NK cell development is not clear. In the present study, we used two genetic methods to delete mTOR and its two complexes. We first demonstrated that mTOR kinase not only regulates the differentiation of NK cells at the late stage, but also determines NK cell development at early stage. Then, we revealed that both mTORC1 and mTORC2 are necessary for the development of early NK cells. The effect of mTORC1 deficiency on the development of early NK cells is different from mTORC2 deficiency. mTORC1 inactivation mainly blocks the transition of CD27+CD11b− iNK cells to mNK cells, while mTORC2 inactivation interferes with the transition from DN NK cells to CD27+CD11b− iNK cells. We also showed that induction of E4BP4 primarily requires mTORC1, while the expression of T-bet requires mTORC1 and mTORC2. Therefore, our data provide further evidence that mTOR and its complexes fine-tune NK cell differentiation.

The regulation of immune cell development is usually studied in a variety of mice with Cre expression at different temporal and spatial levels. For example, MB1-Cre mice are used for in the early stages of B-cell development; CD19-Cre mice are used for relatively mature B cells, while AID-Cre mice are used specifically for the mature B cells within germinal centers. Due to the restrictive time limit imposed by Ncr1-Cre mice, whose Cre is only expressed after NKp46 is expressed by NK cells, how NKp and early iNK cells differentiate at the early development of NK cells has not been studied well. CD122 is a hallmark of NKp. CD122-Cre mice, whose Cre is expressed during and after NK cell lineage is committed, is very suitable for studying the early development of NK cells. On this basis, we reveal here the important roles of mTOR and its two complexes in early NK cell development. Compared with Mtorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg mice with moderate NK cell development defect, the development of early NK cells seems to be more dependent on the early expression of mTOR. Therefore, we believe that the spatiotemporal regulation of NK cell development can be more accurately solved through the combined use of these two Cre mice.

E4BP4 is essential for NK cell development. We previously found that PDK1 kinase orchestrates NK cell development by inducing E4BP4 expression and the pharmaceutical inactivation of mTORC1 by rapamycin inhibits the expression of E4BP4 induced by IL-15 [10]. Here, we provide critical genetic evidence for the induction of E4BP4 by mTORC1. Thus, the PDK1/mTORC1/E4BP4 pathway is crucial for the early development of NK cells, especially the transition from iNK to mNK cells. This hypothesis is further supported by the previous finding that Ncr1-mediated disruption of E4BP4 does not affect NK cell development. However, the ectopic expression of E4BP4 only partially rescues NK cell development in mTOR-deficient mice [6]. Therefore, in addition to E4BP4, mTORC1 may regulate the development of NK cells through other transcription factors such as Eomes.

In this study, based on the Ncr1-CreTg mice generated in our laboratory, we found that the mTORC1 is necessary for the maturation of terminal NK cells. However, the phenotypes we observed in Mtorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg mice or Rptorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg mice were less than the previous studies by other groups [16, 17]. Ncr1-Cre mice have been widely used as a powerful tool for NK cell research. There are several lines of mice with the expression of Cre under the control of Ncr1 promoter. Most of previous studies used mice originally produced in the laboratory of Eric Vivier, whose Cre was knocked-in the 5-UTR of Ncr1 [1]. However, in the Ncr1-CreTg mice used in this study, Cre was controlled by a portion of Ncr1 promoter (~400 bp), so Cre is only expressed by the most mNK cells. This may explain why we observed a moderate reduction in the number of NK cells from Mtorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg mice or Rptorfl/fl/Ncr1-CreTg. The difference between our studies with previous studies suggests that mTORC1 is likely to be less important as NK cells maturation [16, 17]. This possibility may be examined by newly generated Ncr1-CreERT2 mice [19].

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6, H-2b) mice, Mtorfl/fl mice, Rptorfl/fl mice, Rictorfl/fl mice were purchased from Jackson lab. Ncr1-CreTg mice and CD122Cre/+ mice were generated in our lab. Sex- and age-matched animals (8–12 weeks) were used in our experiment. All the mice were C57BL/6 background and maintained under specific pathogen-free animal facilities of Tsinghua University. All procedures of animals were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Tsinghua University.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was conducted using a BD LSR II flow cytometry (BD Biosciences). Monoclonal antibodies against mouse CD3e (eBio500A2), NK1.1 (PK136), CD117 (2B8), CD127 (A7R34), Ly49A (A1(Ly49A)), Ly49C/I (5E6), Ly49H (3D10), Ly49G2 (eBio4D11), Ly49D (eBio4E5), CD11b (M1/70), CD27 (LG.7F9), E4BP4 (S2M-E19), Eomes (Dan11mag), T-bet (eBio4B10), p-STAT5 (47/Stat5(pY694)), KLRG1 (2F1), CD122 (TM-betal), and isotype controls were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) or BD Biosciences (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). For analysis of surface markers, cells were stained with the indicated antibodies in PBS containing 2% fetal bovine serum. The expression level was presented as relative ratio or net mean fluorescence intensity (△MFI), which was determined by subtracting the mean fluorescence intensity of isotype control. For the detection of transcription factors, the NK cells were fixed, permeabilized, and then stained with antibodies.

In vitro IL-15 treatment

Splenocytes from the indicated mice were depleted of red blood cells by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation. The cells were prepared for analyzing before and after overnight stimulation with IL-15/IL-15Rα complex protein. This recombinant protein is the heterocomplex of the mouse IL-15 linked to soluble IL-15 receptor alpha chain via a GS linker (eBioscience, catalog # 14-8152-80).

Adoptive cell transfer

Bone marrow chimera experiments have been previously described [10]. WT and Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice were treated with 5-FU for 4 days, and bone marrow cells were collected for spin infection with MSCV retrovirus encoding control GFP or E4BP4. The MSCV-E4BP4-encoding viral vector also encodes for GFP. 1 × 106 retrovirally transduced bone marrow cells from 5-FU-treated WT or Mtorfl/fl/CD122Cre/+ mice were transplanted into sublethally irradiated RAG1−/−γc− recipient mice. Reconstitution of recipients was assessed by flow cytometry of spleen and bone marrow at 6 weeks after transplantation.

Statistical analyses

Unpaired Student’s t tests (two tailed) or ANOVA (one way or two way) were performed using the Prism software. ns not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (to ZD, 81725007, 31830027, 31821003, and 91942308; to MY, 81771666, and 81471523; to WX, 31700771), National Key Research & Developmental Program of China (to ZD, 2018YFC1003900), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (to MY, 2019A1515011707), Guangzhou Science and Technology Project (to MY, 201707010395), and by 111 Project (B16201).

Author contributions

DL and YW performed and analyzed experiments; DL, MY, and ZD designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures of animals were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Tsinghua University.

Footnotes

Edited by G. Melino

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Meixiang Yang, Email: yangmxqilu@163.com.

Zhongjun Dong, Email: dongzj@mail.tsinghua.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Narni-Mancinelli E, Chaix J, Fenis A, Kerdiles YM, Yessaad N, Reynders A, et al. Fate mapping analysis of lymphoid cells expressing the NKp46 cell surface receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18324–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112064108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiossone L, Chaix J, Fuseri N, Roth C, Vivier E, Walzer T. Maturation of mouse NK cells is a 4-stage developmental program. Blood. 2009;113:5488–96. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-187179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goh W, Huntington ND. Regulation of murine natural killer cell development. Front Immunol. 2017;8:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Male V, Nisoli I, Kostrzewski T, Allan DS, Carlyle JR, Lord GM, et al. The transcription factor E4bp4/Nfil3 controls commitment to the NK lineage and directly regulates Eomes and Id2 expression. J Exp Med. 2014;211:635–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gascoyne DM, Long E, Veiga-Fernandes H, de Boer J, Williams O, Seddon B, et al. The basic leucine zipper transcription factor E4BP4 is essential for natural killer cell development. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1118–24. doi: 10.1038/ni.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crotta S, Gkioka A, Male V, Duarte JH, Davidson S, Nisoli I, et al. The transcription factor E4BP4 is not required for extramedullary pathways of NK cell development. J Immunol. 2014;192:2677–88. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon SM, Chaix J, Rupp LJ, Wu J, Madera S, Sun JC, et al. The transcription factors T-bet and Eomes control key checkpoints of natural killer cell maturation. Immunity. 2012;36:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simonetta F, Pradier A, Roosnek E. T-bet and Eomesodermin in NK cell development, maturation, and function. Front Immunol. 2016;7:241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Daussy C, Faure F, Mayol K, Viel S, Gasteiger G, Charrier E, et al. T-bet and Eomes instruct the development of two distinct natural killer cell lineages in the liver and in the bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2014;211:563–77. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang M, Li D, Chang Z, Yang Z, Tian Z, Dong Z. PDK1 orchestrates early NK cell development through induction of E4BP4 expression and maintenance of IL-15 responsiveness. J Exp Med. 2015;212:253–65. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovanen PE, Leonard WJ. Cytokines and immunodeficiency diseases: critical roles of the gamma(c)-dependent cytokines interleukins 2, 4, 7, 9, 15, and 21, and their signaling pathways. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:67–83. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennedy MK, Glaccum M, Brown SN, Butz EA, Viney JL, Embers M, et al. Reversible defects in natural killer and memory CD8 T cell lineages in interleukin 15-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2000;191:771–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donnelly RP, Loftus RM, Keating SE, Liou KT, Biron CA, Gardiner CM, et al. mTORC1-dependent metabolic reprogramming is a prerequisite for NK cell effector function. J Immunol. 2014;193:4477–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nandagopal N, Ali AK, Komal AK, Lee SH. The critical role of IL-15-PI3K-mTOR pathway in natural killer cell effector functions. Front Immunol. 2014;5:187. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcais A, Cherfils-Vicini J, Viant C, Degouve S, Viel S, Fenis A, et al. The metabolic checkpoint kinase mTOR is essential for IL-15 signaling during the development and activation of NK cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:749–57. doi: 10.1038/ni.2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang C, Tsaih SW, Lemke A, Flister MJ, Thakar MS, Malarkannan S. mTORC1 and mTORC2 differentially promote natural killer cell development. Elife. 2018;7:e35619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Wang F, Meng M, Mo B, Yang Y, Ji Y, Huang P, et al. Crosstalks between mTORC1 and mTORC2 variagate cytokine signaling to control NK maturation and effector function. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4874. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07277-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalim KW, Zhang S, Chen X, Li Y, Yang JQ, Zheng Y, et al. mTOR has a developmental stage-specific role in mitochondrial fitness independent of conventional mTORC1 and mTORC2 and the kinase activity. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0183266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pimeisl IM, Tanriver Y, Daza RA, Vauti F, Hevner RF, Arnold HH, et al. Generation and characterization of a tamoxifen-inducible Eomes (CreER) mouse line. Genesis. 2013;51:725–33. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]