To the Editor—In December 2019, the first cases of a new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) were reported in Wuhan.1 This infectious disease spread rapidly and led to the current global pandemic. Even though COVID-19 is a viral disease, the use of antibiotics in these patients has been a common practice, especially at the beginning of the pandemic. In published series of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, the prevalence of antibiotic use ranges from 72% to 95%.2,3 However, in published reviews, the prevalence of bacterial coinfection in these patients is 8% and that of superinfection is 14.3%.4,5 Therefore, the systematic use of antibiotics does not seem to be an adequate strategy and can lead to toxicity and resistance issues.6

In our center, Moisès Broggi Hospital (a 380-bed regional hospital, located in Barcelona, that serves an area of 425,000 inhabitants), we conducted a before-and-after study to compare the evolution of antibiotic consumption in conventional hospitalization between 2019 (pre–COVID-19) and 2020 (COVID-19), and to analyze the effect of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) team strategies applied during the COVID period.

Between March and May 2020 the AMS team was unable to conducte its usual activities, but the following measures were implemented to avoid antibiotic overuse. First, a multidisciplinary work team (intensive care, anesthesia, internal medicine, pharmacy and emergency medicine departments), led by members of the AMS team, was created to draw up a protocol for the management of COVID-19 patients. This document included recommended antibiotic regimens (ceftriaxone and azithromycin) and their duration (5 and 3 days, respectively). Second, in the computer system, the duration of these treatments was fixed by default to the days defined in the protocol (with prior notification of this measure to all professionals). Prior to completion, antibiotic treatments were reviewed by the clinical pharmacist of the AMS team. After the first COVID-19 wave, the limited duration of treatments in the computer system and the recommendation to use azithromycin were removed from the protocol.

To analyze the evolution of consumption within the hospital and to be able to compare it with that of other hospitals, we used the consumption of antibiotics calculated as defined daily dose (DDD)/100 bed days as an indicator.

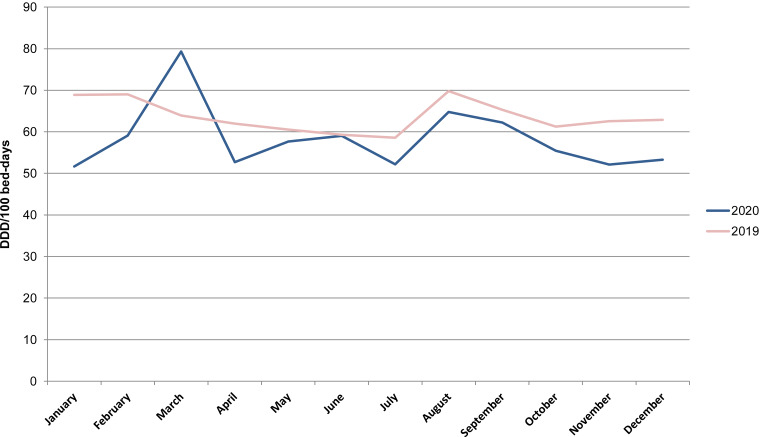

Figure 1 shows the monthly consumption of antibiotics in our center in 2019 and 2020, expressed in DDD/100 bed days. During 2020 antibiotic consumption was lower than in 2019 except for March 2020, when the onset of the pandemic caused a punctual increase of the indicator. The mean global consumption of antibiotics during hospitalization was lower in 2020 than in 2019, with statistically significant differences between both periods (57.8 DDD/100 bed days vs 64.7 DDD/100 bed days; t test P = 0.045). From March to April 2020, the most used antibiotics were azithromycin (16.1 DDD/100 bed days) and ceftriaxone (5.8 DDD/100 bed days). However, piperacillin-tazobactam ranked first in antibiotic use (5.4 DDD/100 bed days) in May 2020.

Fig. 1.

Global antibiotic consumption.

Previous studies conducted by Abelenda-Alonso et al7 and Grau et al8 analyzed antibiotic use measured with this indicator during the first wave of the pandemic. Unlike our study, the researchers observed an increase in overall antibiotic use, although our data do not include antibiotic use in critical patients. On the other hand, our study does coincide with the previous studies in the identification of a biphasic pattern of antibiotic use with a first peak, during which a higher antibiotic use was detected due to community infections and, later, a second peak during which the increase in antibiotic use included and increase in broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Our experience shows how the adaptation of AMS to the new healthcare reality through the implementation of macro strategies made it possible to control antibiotic use during the first wave when the healthcare pressure did not allow the activity of the AMS team. After the first pandemic wave, hospital activity began to normalize and allowed the usual individualized AMS interventions, which also made it possible to maintain the levels of antibiotic use below those observed in the previous year.

In conclusion, the in-hospital strategies implemented during 2020 by the AMS team contributed to reduce antibiotic use in noncritical patients despite the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all our colleagues: doctors, pharmacists, nurses, microbiologists, cleaning staff and other hospital staff for their work and involvement in facing the COVID-19 pandemic.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Langford BJ, So M, Raybardhan S, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in patients with COVID-19: rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021;27:520–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rawson TM, Moore LSP, Zhu N, et al. Bacterial and fungal coinfection in individuals with coronavirus: a rapid review to support COVID-19 antimicrobial prescribing. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71:2459–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Langford BJ, So M, Raybardhan S, et al. Bacterial coinfection and secondary infection in patients with COVID-19: a living rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020;26:1622–1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rawson TM, Moore LSP, Castro-Sanchez E, et al. COVID-19 and the potential long-term impact on antimicrobial resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020;75:1681–1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abelenda-Alonso G, Padullés A, Rombauts A, et al. Antibiotic prescription during the COVID-19 pandemic: a biphasic pattern. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2020;41:1371–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grau S, Echeverria-Esnal D, Gómez-Zorrilla S, et al. Evolution of antimicrobial consumption during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021;10(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]