Abstract

BACKGROUND

Post-operative atrial fibrillation (POAF) is a common yet understudied clinical issue after coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) leading to higher mortality rates and stroke. This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the rates of adverse outcomes between patients with and without POAF in patients treated with CABG or combined procedures.

METHODS

The search period was from the beginning of PubMed and Embase to May 18th, 2020 with no language restrictions. The inclusion criteria were: (1) studies comparing new onset atrial fibrillation before or after revascularization vs. no new onset AF before or after revascularization. The outcomes assessed included all-cause mortality, cardiac death, cerebral vascular accident (CVA), myocardial infarction (MI), repeated revascularization, major adverse cardiac event (MACE), and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCEs).

RESULTS

Of the 7,279 entries screened, 11 studies comprising of 57,384 patients were included. Compared to non-POAF, POAF was significantly associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality (Risk Ratio (RR) = 1.58; 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.42−1.76, P < 0.00001) with accompanying high level of heterogeneity ( I2 = 62%).

Conclusions

Patients with POAF after CABG or combined procedures are at an increased risk of all-cause mortality or CVAs. Therefore, POAF after such procedures should be closely monitored and treated judiciously to minimize risk of further complications. While there are studies on POAF versus no POAF on outcomes, the heterogeneity suggests that further studies are needed.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common type of arrhythmia associated with serious outcomes such as stroke.[1] AF also happens to be a common outcome after coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) and is seen in roughly 20%−40% of patients, particularly during the first week after surgery.[2] In contrast, the incidence of post-operative AF (POAF) following other procedures such as thoracic surgery and non-cardiac, non-thoracic surgery are much lower, ranging from 10% to 30% and 1% to 15%, respectively.[3] These figures are expected to rise in the foreseeable future as the incidence of AF in the general population is strongly age-dependent and the population undergoing cardiac surgery continues to age.[4] This poses a significant challenge for both patients and clinicians as AF is associated with numerous detrimental sequelae, such as worsening of a patient’s hemodynamic status, increased risk of congestive heart failure (CHF), embolic events, and longer intensive care unit stay.

AF may also necessitate further medical intervention, such as the use of atrioventricular nodal blocking and antiarrhythmics. These interventions are not without consequence, as they may increase the need for cardiac pacing. While POAF may not be the sole perpetrator of detrimental outcomes like a higher risk of stroke, greater in-hospital mortality and worse survival at long-term follow-up, it is most likely a significant contributing factor that demands a closer examination.[3, 5] Despite efforts to elucidate the optimal management of POAF, incidence following cardiac surgery has remained relatively consistent in the past several decades, suggesting that greater efforts must be made in understanding its treatment and cause.[6, 7] To assess the clinical significance of POAF, the present study aims to evaluate the occurrence of adverse outcomes between patients with and without POAF.

METHODS

Search Strategy, Inclusion & Exclusion Criteria

This study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. PubMed and Embase were searched for studies that compared POAF to non-POAF patients after revascularization. Other meta-analyses and systematic reviews were excluded from the search. The following search terms were used for both databases: [(‘atrial fibrillation’) AND (‘revascularization’) OR (‘percutaneous coronary intervention’) OR (‘PCI’) OR (‘coronary artery bypass graft’) OR (‘CABG’)]. The search period was from the beginning of the database through May 18th, 2020 with no language restrictions. Both fully published studies and abstracts were used. The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) studies comparing new onset AF before or after revascularization vs. no new onset AF before or after revascularization. The outcomes assessed included all-cause mortality, cardiac death, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), myocardial infarction (MI), repeated revascularization, major adverse cardiac event (MACE), and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCEs). MACE was defined as a composite of non-fatal stroke, non-fatal MI, and cardiovascular death, whereas MACCE was defined as a composite of all-cause mortality, MI, stroke, or ischemia-driven target vessel revascularization.

Data Extraction and Statistical Analysis

Collected data from the studies were entered into pre-specified spreadsheets in Microsoft Excel. All potentially relevant studies were retrieved as complete manuscripts, which were assessed fully to determine their sufficiency with the inclusion criteria. We extracted the following data from the included studies: (1) publication details: last name of the first author, publication year; (2) study design; (3) outcome(s); (4) characteristics of the population including sample size, gender, age, and the number of subjects; (5) follow up duration and adequacy; and (6) post-surgical treatment and monitoring. T-test was used to compare age between subgroups, while Fisher’s Exact Test was used to compare other baseline characteristics between the subgroups. Risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) was reported from the analysis. Due to a lack of consistency and omittance of data between studies, we only used a baseline characteristic from a study if there was one matching it in both subgroups. Statistical significance was defined as P-value < 0.05.

Heterogeneity across studies was determined using the I2 statistic from the standard X2 test. The I2 statistic from the standard X2 test describes the percentage of variability in the effect estimates resulting from heterogeneity. I2 > 50% was considered to reflect significant statistical heterogeneity. The random-effects model using the inverse variance heterogeneity method was used with I2 > 50% whilst the fixed-effects model was used when I2 < 50%. To locate the origin of the heterogeneity, sensitivity analysis excluding one study at a time was also performed.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

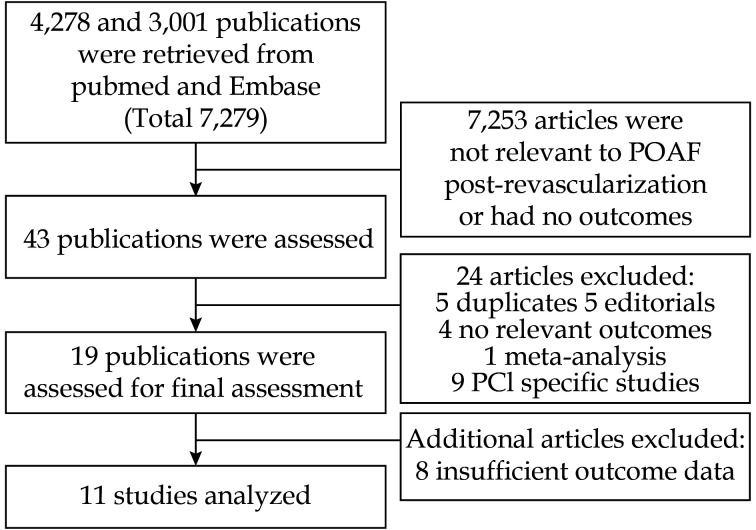

The meta-analysis consists of 11 studies involving 57,384 participants (40,142 from CABG only, 17,242 from combined procedures). A flow diagram detailing the search and study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1. The prevalence of older age (P = 0.001), hypertension (P < 0.00001), male sex ( P < 0.00001), hyperlipidemia ( P < 0.00001), renal failure ( P < 0.00001), congestive heart failure ( P < 0.00001), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease ( P < 0.00001), and current smokers ( P < 0.00001) were higher in the POAF group. In contrast, diabetes ( P = 0.58) was not found to be associated with POAF. Baseline characteristics for patients with POAF from the included studies are illustrated in Table 1. Baseline characteristics for patients without POAF from the included studies are illustrated in Table 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for the study selection process.

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; POAF: post-operative atrial fibrillation.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients with POAF from the included studies.

| Study | Sample size

(n) |

Age

(mean ± SD) |

Male

n (%) |

Hypertension

n (%) |

Diabetes

n (%) |

Hyperlipidemia

n (%) |

Renal

failure n(%) |

CHF

n (%) |

COPD

n (%) |

Current

Smoker n (%) |

Follow up

duration (yrs) |

| CHF: congestive heart failure; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; POAF: postoperative atrial fibrillation. | |||||||||||

| Almassi 2012[8] | 551 | 65.3 ± 8.5 | 551

(100%) |

494

(90%) |

254

(46%) |

− (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 130

(24%) |

154

(28%) |

1 |

| Almassi 2014[9] | 549 | 65.8 ± 8.5 | 549

(100%) |

492

(89.6%) |

216

(39.3%) |

− (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 130

(23.7%) |

153

(27.9%) |

1 |

| Batra 2019[10] | 2290 | 70 ± 5 | 1884

(82.3%) |

1697

(74.1%) |

675

(29.5%) |

− (−) | 56

(2.4%) |

406

(17.7%) |

138

(6%) |

− (−) | 2.2 |

| Bramer 2010[11] | 1122 | 68.5 ± 8.1 | 884

(78.8%) |

578

(54.5%) |

232

(20.7%) |

− (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 130

(11.6%) |

− (−) | 2.5 |

| de Oliveira 2007[12] | 397 | 67.6 ± 8.7 | 297

(75%) |

301

(75.8%) |

119

(29.9%) |

194

(48.8%) |

− (−) | 68

(17.1%) |

− (−) | 145

(36.5%) |

Unspecified |

| Fensgrud 2017[13] | 165 | 69.2 ± 7.6 | 134

(81%) |

59

(36%) |

28

(17%) |

− (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 94

(57%) |

15 |

| Kalavrouziotis 2007[15] | 2047 | < 60 16.2%

60−69 31.9% 70−79 40.6% > 80 11.4% |

1537

(75.1%) |

1310

(64%) |

692

(33.8%) |

− (−) | 151

(7.4%) |

348

(17%) |

342

(16.7%) |

− (−) | Unspecified |

| Konstantino 2016[2] | 37 | 76 ± 7 | 25

(68%) |

31

(84%) |

13

(35%) |

37

(100%) |

− (−) | − (−) | 6

(16%) |

8

(22%) |

8.5 |

| Mankad 2019[16] | 400 | 68.9 | 200

(100%) |

171

(85.5%) |

83

(41.5%) |

− (−) | − (−) | 113

(56.5%) |

− (−) | − (−) | 5 |

| Mariscalco 2009[17] | 2535 | 69.3 ± 7.9 | 1778

(70.1%) |

1554

(61.3%) |

487

(19.2%) |

− (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 7.9 |

| Saxena 2012[14] | 5547 | 69.04 ± 9.03 | − (−) | 4425

(79.8%) |

1786

(32.2%) |

4500

(81.1%) |

200

(3.6%) |

967

(17.4%) |

773

(13.9%) |

− (−) | 3.66 |

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of patients without POAF from the included studies.

| Study | Sample size

(n) |

Age

(mean ± SD) |

Male

n(%) |

Hypertension

n (%) |

Diabetes

n (%) |

Hyperlipidemia

n (%) |

Renal failure

n (%) |

CHF

n (%) |

COPD

n (%) |

Current Smoker

n (%) |

Follow up

duration (yrs) |

| CHF: congestive heart failure; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; POAF: post-operative atrial fibrillation. | |||||||||||

| Almassi 2012[8] | 1552 | 61.6 ± 8.2 | 1552

(100%) |

1218

(85%) |

664

(43%) |

− (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 297

(19%) |

561

(36%) |

1 |

| Almassi 2014[9] | 1547 | 62.4 ± 8.2 | 1547

(100%) |

1313

(84.9%) |

582

(37.6%) |

− (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 295

(19.1%) |

557

(36%) |

1 |

| Batra 2019[10] | 6080 | 66 ± 6 | 4909

(81.7%) |

4128

(67.9%) |

1851

(30.4%) |

− (−) | 125

(2.1%) |

974

(16%) |

319

(5.2%) |

− (−) | 2.2 |

| Bramer 2010[11] | 3976 | 64 ± 9.7 | 3081

(77.5%) |

1885

(47.4%) |

914

(23%) |

− (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 386

(9.7%) |

− (−) | 2.5 |

| de Oliveira 2007[12] | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | Unspecified |

| Fensgrud 2017[13] | 406 | 64.6±9.4 | 313

(77%) |

123

(30%) |

77

(19%) |

− (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 251

(62%) |

15 |

| Kalavrouziotis 2007[15] | 5300 | < 60 37.1%

60−69 32% 70−79 25.8% > 80 5.1% |

1404

(73.5%) |

3169

(59.8%) |

1738

(32.8%) |

− (−) | 254

(4.8%) |

663

(12.5%) |

652

(12.3%) |

− (−) | Unspecified |

| Konstantino 2016[2] | 99 | 70±9 | 80

(81%) |

66

(67%) |

38

(39%) |

83

(84%) |

− (−) | − (−) | 12

(12%) |

38

(39%) |

8.5 |

| Mankad 2019[16] | 200 | 64 | 198 | 184

(92%) |

84

(42.2%) |

− (−) | − (−) | 63

(31.5%) |

− (−) | − (−) | 5 |

| Mariscalco 2009[17] | 6960 | 64.5 ± 9.5 | 5168

(74.2%) |

4109

(59%) |

1450

(20.8%) |

− (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 7.9 |

| Saxena 2012[14] | 13950 | 64.02 ± 10.72 | − (−) | 10561

(75.7%) |

4580

(32.8%) |

11277

(80.3%) |

424

(3%) |

1874

(13.4%) |

1477

(10.6%) |

− (−) | 3.66 |

POAF vs. no POAF in CABG only Patients: All-Cause Mortality

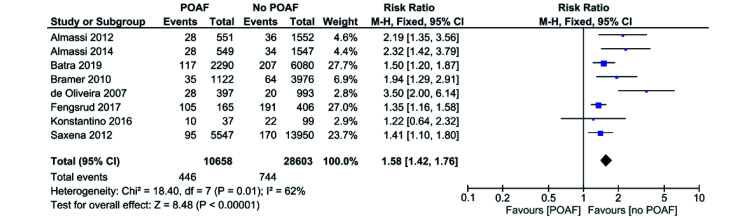

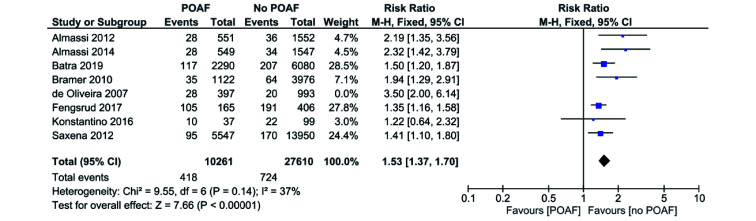

Eight out of 11 studies reported all-cause mortality in CABG only patients.[2, 8-14] All studies included favored no POAF apart from Konstantino, 2016.[2] Pooled analysis of all the included studies demonstrated that patients with POAF have a significantly higher risk of all-cause mortality when compared to the no POAF patients (RR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.42−1.76,P < 0.00001; Figure 2). I2 was 62% across all studies, indicating a significant level of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis showed that the major source of heterogeneity was due to de Oliveira 2007. Elimination of the study from the pooled analysis decreases the I2 value to 37% and risk of all-cause mortality (RR = 1.53, 95% CI: 1.37−1.70,P < 0.00001; Figure 3), though the risk remains high.

Figure 2.

POAF vs. no POAF in CABG only patients: all-cause mortality.

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; POAF: post-operative atrial fibrillation.

Figure 3.

POAF vs. no POAF in CABG only patients: all-cause (sensitivity analysis by exclusion of each study).

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; POAF: post-operative atrial fibrillation.

POAF vs. no POAF in CABG only Patients: CVA

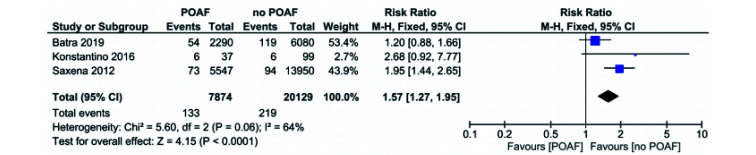

Three studies reported CVA as an outcome in CABG only patients.[2, 10, 14] All three studies reported in favor of no POAF (Figure 4). Pooled analysis of the included studies showed that POAF patients have a significantly higher risk of CVA when compared to the no POAF patients (RR = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.27−1.95,P < 0.0001). I2 value was 64% across all studies, which represents significant heterogeneity. Removal of either Saxena 2012 or Batra 2019 reduces heterogeneity significantly, I2 = 49% and I2 = 0, respectively.

Figure 4.

POAF vs. no POAF in CABG only patients: cerebral vascular accident.

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; POAF: post-operative atrial fibrillation.

POAF vs. no POAF in CABG or combined procedures patients: All-cause mortality

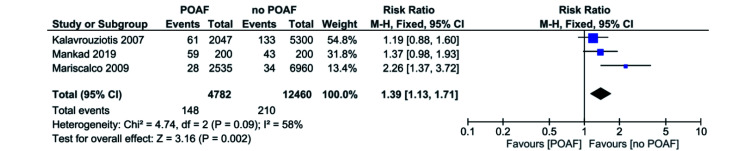

A total of three out of 11 studies reported all-cause mortality regarding CABG or combined procedures (CABG and valvular surgery).[15-17] Mariscalco 2009 favoured no POAF,[17] while Kalavrouziotis 2007[15] and Mankad 2019[16] were inconclusive. Pooled analysis of all the included studies demonstrated that patients with POAF have a significantly higher risk of all-cause mortality when compared to the no POAF patients (RR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.13−1.71, P = 0.002). I2 was 58% across all studies, indicating a significant level of heterogeneity. The major source of heterogeneity was due to Mariscalco 2009. Elimination of the study from the pooled analysis decreases the I2 value to 0 and risk of all-cause mortality (RR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.00−1.57, P = 0.05; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

POAF vs. no POAF in CABG or combined procedures patients: all-cause mortality.

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; POAF: post-operative atrial fibrillation.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, there were no existing systematic reviews or meta-analyses that focused on the outcomes of POAF from neither CABG nor combined procedures. Older age, male gender, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, renal failure, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and current smokers were identified as the main significant predictors of POAF in our baseline populations. Our statistical analysis determined that POAF increased the risk of all-cause mortality and CVA in patients undergoing CABG only and increased the risk of all-cause mortality in patients undergoing CABG or combined procedures.

In our analysis, advanced age was consistently identified as a significant predictor of POAF in all of our included studies, consistent with findings in the literature.[18] Advanced age is widely recognized as a POAF risk factor due to the physiological changes associated with aging. These changes, such as loss of myocardial fibers, increased fibrosis and collagen deposition in the atria set the stage for POAF by altering atrial electrical properties.[3] Consequently, POAF could precipitate in patients with advanced ages when exposed to POAF inducing situations, such as surgery-related metabolic alterations.[19] Other significant predictors of POAF that were identified included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and smoking, which are also traditional risk factors for cardiovascular mortality.[20] Patients afflicted with these conditions were more likely to have POAF, but their cardiovascular risk factors may be a contributor to their higher mortality from POAF. A meta-analysis on POAF after general cardiac surgery similarly found that while POAF patients tended to be older, diabetes was not associated with POAF.[21] However, they also found that other risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, or smoking were not associated with POAF.[21] One possible explanation is that the number of studies regarding POAF after CABG remains few, leaving the possibility of underpowered data overall. In addition, many of the studies that we included used different thresholds to measure baseline characteristics or omitted the data entirely.

Patients with new-onset POAF after cardiac operations may have poorer outcomes for the following reasons. POAF is more commonly seen in frail patients and it is possible that older age plays a large role in increasing the likelihood of mortality and CVA after significant cardiac procedures.[22-28] Indeed, the CHA2DS2-VASc score has been identified as a predictor of ischemic stroke in patients undergoing CABG and PCI.[29] Although the use of this score should be limited to the original intentions, it has also been shown to predict POAF after cardiac procedures.[30, 31] At this time, a more robust understanding of the pathophysiology and risk factors surrounding POAF is necessary to further examine this hypothesis. While there are many ideas proposed for the pathophysiology underlying POAF, inflammation as the major mechanism may soon be the leading hypothesis due to an increasing body of evidence to suggest its importance.[32] In one animal study, it was established that the degree of atrial inflammation in mongrel canines was associated with a proportional increase in the inhomogeneity of atrial conduction and AF duration, potentially playing a role in the pathogenesis of early postoperative AF.[33] These findings are corroborated by a different study which found that acute inflammation as mimicked by arachidonic acid slows conduction anisotropically, which may set the stage for re-entry.[34] In human studies, patients who have higher postoperative leukocyte counts are significantly more likely to develop POAF and elevated pre- and post-operative neutrophils/lymphocytes ratio in patients undergoing CABG can be associated with an increased incidence of POAF.[35] While the exact mechanism by which these blood components can trigger POAF is unknown, systemic and local inflammation due to surgical stress are unavoidable consequences of cardiothoracic procedures, thus further research should examine exactly how inflammation plays a role. Current risk prediction models for POAF are derived from epidemiologic studies and are not based on the aforementioned pathophysiologic mechanisms.[21] These models are infrequently used in clinical settings, thus additional investigations may also facilitate the production of more accurate risk prediction models, both for POAF and for morbidity and mortality after cardiac surgery.

An alternative explanation for the increased risk of mortality and CVA could be attributed to persistent or recurrent AF and consequent cardioembolic stroke. In one review examining POAF, it was found to occur in 25%−60% of cardiac surgery patients depending on the procedure performed, with incidence highest in patients who have CABG and concomitant valve surgery.[36] These results are also supported by another study which found a POAF recurrence rate of 28.3% in the first 2−4 weeks post-discharge, despite patients leaving in sinus rhythm.[37] Due to inconsistencies in follow-up between the different practice environments in the included studies, and that 40,142 out of 57,384 patients included in this study underwent one of the procedures with the highest incidence of POAF, it is entirely possible that asymptomatic POAF developing weeks post-discharge is a plausible source of the risk.

Limitations

The main limitation of this review is the degree of heterogeneity detected across the studies. A significant degree of 62% was discovered during the analysis of all-cause mortality and an exclude-one sensitivity analysis was subsequently performed to isolate and remove the source. Even after the analysis, there was still a small degree of heterogeneity remaining at 37%. It is also important to note that the removal of de Oliveira, et al.[12] with sensitivity analysis dropped heterogeneity below 50% for all-cause mortality for CABG only procedures, implying that a single study may be strongly and disproportionately impacting the data. However, with or without de Oliveira et al,[12] the significance of the data remains (P < 0.00001, Figure 4).

Additionally, it should be noted that all-cause mortality in the included studies varied in their time of follow up, with some studies including only 30 days all-cause mortality data while some studies reported long term mortality data over several years of follow up. In this pooled analysis, the longest given outcome data was used.

Post treatment models also varied between studies, as different hospitals and regions had different guidelines in monitoring and preferred treatment, doses, and duration. It would be prudent for future studies to implement prophylaxis guided by newer meta-analyses to gauge its impact on outcomes.[38]

Conclusion

Patients with POAF after CABG or combined procedures are at an increased risk of all-cause mortality or CVA. Hence, the incidence of POAF after such procedures should be monitored and treated appropriately to minimize the risk of complications. While studies have been done on POAF vs. no POAF on outcomes, the heterogeneity suggests that more can be done regarding consistency in follow up and outcome data.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

None.

Contributor Information

Sharen Lee, Email: sharen212@gmail.com.

Ka Hou Christien Li, Email: lijiahao218@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Gutierrez C, Blanchard DG Diagnosis and Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:442–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konstantino Y, Zelnik Yovel D, Friger MD, et al Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation Following Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery Predicts Long-Term Atrial Fibrillation and Stroke. Isr Med Assoc J. 2016;18:744–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg JW, Lancaster TS, Schuessler RB, Melby SJ Postoperative atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery: a persistent complication. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;52:665–672. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Echahidi N, Pibarot P, O'Hara G, Mathieu P Mechanisms, prevention, and treatment of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:793–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mostafa A, El-Haddad MA, Shenoy M, Tuliani T Atrial fibrillation post cardiac bypass surgery. Avicenna J Med. 2012;2:65–70. doi: 10.4103/2231-0770.102280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen J, Lall S, Zheng V, et al The persistent problem of new-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation: a single-institution experience over two decades. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:559–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melby SJ Might a beta blocker finally provide some relief from postoperative atrial fibrillation? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:965–966. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.06.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almassi GH, Pecsi SA, Collins JF, et al Predictors and impact of postoperative atrial fibrillation on patients' outcomes: a report from the Randomized On Versus Off Bypass trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almassi GH, Wagner TH, Carr B, et al Postoperative atrial fibrillation impacts on costs and one-year clinical outcomes: the Veterans Affairs Randomized On/Off Bypass Trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batra G, Ahlsson A, Lindahl B, et al Atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing coronary artery surgery is associated with adverse outcome. Ups J Med Sci. 2019;124:70–77. doi: 10.1080/03009734.2018.1504148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bramer S, van Straten AH, Soliman Hamad MA, et al The impact of new-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation on mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliveira DC, Ferro CR, Oliveira JB, et al Postoperative atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass graft: clinical factors associated with in-hospital death. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2007;89:16–21. doi: 10.1590/S0066-782X2007001400016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fengsrud E, Englund A, Ahlsson A Pre- and post-operative atrial fibrillation in CABG patients have similar prognostic impact. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2017;51:21–27. doi: 10.1080/14017431.2016.1234065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saxena A, Dinh DT, Smith JA, et al Usefulness of postoperative atrial fibrillation as an independent predictor for worse early and late outcomes after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (multicenter Australian study of 19, 497 patients) Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalavrouziotis D, Buth KJ, Ali IS The impact of new-onset atrial fibrillation on in-hospital mortality following cardiac surgery. Chest. 2007;131:833–839. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mankad P, Kalva T, Earasi M, et al Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation Predicts Late Atrial Fibrillation in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting and/or Valve Surgery. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16(5 Supplement):S497. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mariscalco G, Engström KG Postoperative atrial fibrillation is associated with late mortality after coronary surgery, but not after valvular surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1871–1876. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorczyca I, Michta K, Pietrzyk E, Wożakowska-Kapłon B Predictors of post-operative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Kardiol Pol. 2018;76:195–201. doi: 10.5603/KP.a2017.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chelazzi C, Villa G, De Gaudio AR Postoperative atrial fibrillation. ISRN Cardiol. 2011;2011:203179. doi: 10.5402/2011/203179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carnethon MR, Lynch EB, Dyer AR, et al Comparison of risk factors for cardiovascular mortality in black and white adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1196–1202. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.11.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eikelboom R, Sanjanwala R, Le ML, et al Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation After Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;111:544–554. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.05.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tse G, Gong M, Nunez J, et al Frailty and Mortality Outcomes After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:1097 e1–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tse G, Gong M, Wong SH, et al Frailty and Clinical Outcomes in Advanced Heart Failure Patients Undergoing Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:255–261 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Yuan M, Gong M, Li G, Liu T, Tse G Associations Between Prefrailty or Frailty Components and Clinical Outcomes in Heart Failure: A Follow-up Meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:509–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Yuan M, Gong M, Tse G, Li G, Liu T Frailty and Clinical Outcomes in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:1003–1008 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dobaria V, Hadaya J, Sanaiha Y, et al. The Pragmatic Impact of Frailty on Outcomes of Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Ann Thorac Surg 2020. Published Online First: Oct 17, 2020.DOI: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.08.028.

- 27.Okamura H, Kimura N, Mieno M, et al Preoperative sarcopenia is associated with late mortality after off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;58:121–129. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezz378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henry L, Halpin L, Barnett SD, et al Frailty in the Cardiac Surgical Patient: Comparison of Frailty Tools and Associated Outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;108:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian Y, Yang C, Liu H CHA2DS2-VASc score as predictor of ischemic stroke in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting and percutaneous coronary intervention. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11404. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11923-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu F, Xin Z, Bin Waleed K, et al CHA2DS2-VASc Score as a Predictor of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation After Catheter Ablation of Typical Atrial Flutter. Front Physiol. 2020;11:558. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chua SK, Shyu KG, Lu MJ, et al Clinical utility of CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scoring systems for predicting postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:919–926 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korantzopoulos P, Letsas KP, Tse G, et al Inflammation and atrial fibrillation: A comprehensive review. J Arrhythm. 2018;34:394–401. doi: 10.1002/joa3.12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishii Y, Schuessler RB, Gaynor SL, et al Inflammation of atrium after cardiac surgery is associated with inhomogeneity of atrial conduction and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2005;111:2881–2888. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.475194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tselentakis EV, Woodford E, Chandy J, et al Inflammation effects on the electrical properties of atrial tissue and inducibility of postoperative atrial fibrillation. J Surg Res. 2006;135:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zakkar M, Ascione R, James AF, et al Inflammation, oxidative stress and postoperative atrial fibrillation in cardiac surgery. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;154:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel D, Gillinov MA, Natale A Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: where are we now? Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2008;8:281–291. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowres N, Mulcahy G, Jin K, Gallagher R, Neubeck L, Freedman B Incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation recurrence in patients discharged in sinus rhythm after cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2018;26:504–511. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivx348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gudbjartsson T, Helgadottir S, Sigurdsson MI, et al New-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation after heart surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2020;64:145–155. doi: 10.1111/aas.13507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]