Key Points

Question

What is the association between fetal exposure to antiseizure medication (ASM) and subsequent cognitive abilities of the child?

Findings

This multicenter cohort study found no differences in 2-year-old children of women with epilepsy vs healthy women on the primary outcome of language domain scores of the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition. However, secondary analyses revealed that higher ASM levels and doses in the third trimester were associated with lower scores for other domains.

Meaning

Overall, in this study, outcomes at 2 years of age did not differ by ASM exposures.

This multicenter cohort study compares children at 2 years of age with and without fetal exposure to antiseizure medications and assesses the association of maximum exposure to these medications in the third trimester of pregnancy with neurodevelopment.

Abstract

Importance

The neurodevelopmental risks of fetal exposure are uncertain for many antiseizure medications (ASMs).

Objective

To compare children at 2 years of age who were born to women with epilepsy (WWE) vs healthy women and assess the association of maximum ASM exposure in the third trimester and subsequent cognitive abilities among children of WWE.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) study is a prospective, observational, multicenter investigation of pregnancy outcomes that enrolled women from December 19, 2012, to January 13, 2016, at 20 US epilepsy centers. Children are followed up from birth to 6 years of age, with assessment at 2 years of age for this study. Of 1123 pregnant women assessed, 456 were enrolled; 426 did not meet criteria, and 241 chose not to participate. Data were analyzed from February 20 to December 4, 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Language domain score according to the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (BSID-III), which incorporates 5 domain scores (language, motor, cognitive, social-emotional, and general adaptive), and association between BSID-III language domain and ASM blood levels in the third trimester in children of WWE. Analyses were adjusted for multiple potential confounding factors, and measures of ASM exposure were assessed.

Results

The BSID-III assessments were analyzed in 292 children of WWE (median age, 2.1 [range, 1.9-2.5] years; 155 female [53.1%] and 137 male [46.9%]) and 90 children of healthy women (median age, 2.1 [range, 2.0-2.4] years; 43 female [47.8%] and 47 male [52.2%]). No differences were found between groups on the primary outcome of language domain (−0.5; 95% CI, −4.1 to 3.2). None of the other 4 BSID-III domains differed between children of WWE vs healthy women. Most WWE were taking lamotrigine and/or levetiracetam. Exposure to ASMs in children of WWE showed no association with the language domain. However, secondary analyses revealed that higher maximum observed ASM levels in the third trimester were associated with lower BSID-III scores for the motor domain (−5.6; 95% CI, −10.7 to −0.5), and higher maximum ASM doses in the third trimester were associated with lower scores in the general adaptive domain (−1.4; 95% CI, −2.8 to −0.05).

Conclusions and Relevance

Outcomes of children at 2 years of age did not differ between children of WWE taking ASMs and children of healthy women.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01730170

Introduction

Antiseizure medications (ASMs) are among the most commonly prescribed teratogens. Although our knowledge of ASM teratogenesis has increased during the last 2 decades, the risks of fetal exposure are known for only a few ASMs.1,2 Meador et al3,4 previously reported greater neurodevelopmental risk for valproate compared with carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and phenytoin, but these risks remain uncertain for most ASMs1,2 except for levetiracetam, which also appears to have less risk than valproate.5,6,7,8 Further, ASM prescription practices have changed.9

The risks of teratogens are dose dependent, so understanding the risks of higher exposure can direct dose management. When sample sizes are large, dose-dependent associations with malformations are seen across ASMs, suggesting that all ASMs may exhibit dose-dependent effects.10 Similarly, teratogenic effects on neuropsychological functions would be expected to exhibit dose-dependent effects, but dose-dependent cognitive/behavioral effects have been demonstrated in humans only for valproate. Substantial and variable changes in clearance occur during pregnancy for several ASMs,11,12 which could obscure dose-dependent effects. The present study compares children at 2 years of age who were born to women with epilepsy (WWE) vs healthy women and assesses the association of ASM exposure with neurodevelopment in children of WWE using both ASM blood levels (ABLs) and dosage.

Methods

Design

The Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) study is a prospective, observational, multicenter investigation of pregnancy outcomes for both WWE and their children. The MONEAD study is a continuation of the Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (NEAD) study, enrolling a new cohort representative of the ASMs currently being used at tertiary epilepsy centers. Our primary objective for neurodevelopmental outcomes is to assess children of WWE and healthy women and the association of fetal ASM exposure with cognitive/behavioral outcomes in children of WWE. The ultimate primary neurodevelopmental outcome will be verbal abilities at 6 years of age. This study presents the outcomes at 2 years of age, which represent the first MONEAD cognitive data. Our a priori hypothesis is that children exposed in utero to certain ASMs will exhibit a concentration-dependent impairment in verbal intellectual abilities.

Enrollment occurred from December 19, 2012, to January 13, 2016, at 20 epilepsy centers in the US (listed in eMethods 1 in Supplement 1). Local institutional review boards approved the study, and informed consent was obtained from all adult participants. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Pregnant WWE and healthy women were recruited from the 20 epilepsy practices and through referral from obstetricians and other physicians as well as self-referral. Inclusion criteria for WWE were ages 14 to 45 years and gestational age of 20 weeks or less. Exclusion criteria included history of psychogenic nonepileptic spells, expected IQ of less than 70, other major medical illness, progressive cerebral disease, and switching of ASMs in pregnancy before enrollment. Unlike the NEAD study, which enrolled only WWE who used any of 4 monotherapies, MONEAD enrolled all WWE regardless of ASM regimen to provide a more representative sample. Pregnant healthy women were enrolled with criteria adjusted during the study to maintain relative similarity to the pregnant WWE group. Children born to WWE and healthy women, their fathers, and maternal relatives were also enrolled. Data were collected from participants using a daily electronic diary that was verified at study visits and with medical records.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcomes for this analysis were the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (BSID-III)13 language domain score at 2 years of age in children of WWE vs healthy women, controlling for potential confounding factors, and the association between the BSID-III language domain and ABLs in the third trimester in children of WWE. Because these primary outcomes address different research questions, no adjustment of type I error rate for multiple comparisons was applied. Exposure to ASM during the third trimester was used for the primary analysis because ASM associations with the immature animal brain are similar to those of alcohol, and fetal alcohol effects are primarily due to exposure during the third trimester.1,14

Potential confounding maternal variables included age, IQ score, gestational age in weeks at enrollment, educational level, employment status at enrollment, household income, planned/welcomed pregnancy, major depressive episode during pregnancy, smoking, alcohol use, and illicit substance use. Potential confounding variables related to the child included sex, race/ethnicity, gestational age at birth, birth weight, small for gestational age, and major congenital malformations. Additional potential confounding variables for children of WWE included mother’s epilepsy type and 5 or more convulsions during pregnancy, which have been reported to be associated with poorer outcomes.15

Risk factors assessed for potential confounding and in secondary analyses included breastfeeding status, periconceptional folate use, folate dose (none, >0 to 0.4 mg, >0.4 to 1.0 mg, >1.0 to 4.0 mg, and >4.0 mg), mean anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory score),16 depression (Beck Depression Inventory II),17 and perceived stress (14-item Perceived Stress Scale)18 during pregnancy and/or post partum through the child’s visit at 2 years of age. An exploratory factor was mean maternal sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index).19 Additional risk factors for children of WWE using ASM included ASM group (monotherapy vs polytherapy), ASM category (lamotrigine monotherapy, levetiracetam monotherapy, other monotherapy, lamotrigine plus levetiracetam polytherapy, and other polytherapy), and ASM dose. Additional details regarding the covariates and risk factors are found in eMethods 2 in Supplement 1.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from February 20 to December 4, 2020. Language domain scores were compared between children of WWE and children of healthy women using an unadjusted linear regression model and a multiple regression model adjusted for the mother’s IQ, educational level, and postpartum maternal anxiety and the child’s sex, ethnicity, and birth weight. Covariates for the adjusted model were selected using a forward selection algorithm with language domain score as the outcome. Mother’s IQ and study group were included in the model a priori. For selection of additional covariates, the Akaike information criterion was used to compare models, and the significance level for covariate entry was set to P = .10 (2-tailed test).

Analyses for ASM exposure variables and risk factors were restricted to the subset of children of WWE with mothers on ASM at enrollment. To allow comparison of exposure across ASMs, the ratio of ABL was calculated for each ASM by dividing the mother’s ABL by the upper limit of the suggested therapeutic ranges, mostly taken from published ranges,20 or clinical laboratory references used by Stanford University clinics. For polytherapy, the sum of the ratio of ABL across all ASMs was used. To conduct a similar comparison of ASM dosages, the ratio of the defined daily dose (DDD) was calculated by dividing the mother’s ASM dose by the World Health Organization DDD values21 or derived from package inserts. For polytherapy, the sum of the ratio of DDDs across all ASMs was used. Because women could have more than 1 ABL measurement, the maximum observed ratio of ABL within the third trimester, including the ABL from the day of delivery, was used for analysis. The maximum ratio of DDD within the third trimester was used for analyses with dose.

To assess the association of maximum observed third-trimester ratio of ABL with the language domain score, both an unadjusted linear regression model and a multiple regression model adjusting for the mother’s IQ, educational level, enrollment ASM group, weeks of gestational age at enrollment, and postpartum maternal anxiety and the child’s ethnicity and sex were used. Covariates were selected using a forward selection algorithm with the same criteria as the analysis of WWE vs healthy women but restricting the population to children of WWE using ASM. The mother’s IQ and ASM group at enrollment were included in the model a priori. To assess whether the association between maximum third-trimester ratio of ABL and the language domain score were different for different ASMs, interaction models were run for the third-trimester ASM group and ASM category.

Analyses of the 4 additional BSID-III domains (motor, cognitive, social-emotional, and general adaptive) were included as secondary analyses using the same analytical methods. Details of these statistical analyses and the analyses for the secondary and exploratory risk factors are included in eMethods 2 in Supplement 1.

To evaluate the potential impact of missing data, a sensitivity analysis was run to compare risk factors and potential confounding variables between the analysis population and those excluded. Additional sensitivity analyses for the primary outcomes were run excluding children with major congenital malformations. To assess the impact of twins, sensitivity analyses for the primary analyses were run excluding 1 twin, excluding all twins, and using a regression model with generalized estimating equations to account for the correlation within twin pairs.

Results

Of 1123 pregnant women assessed, 456 were enrolled; 426 did not meet the study criteria, and 241 chose not to participate. A total of 345 children of WWE and 106 children of healthy women were born and enrolled in the study. Of these, 292 children of WWE (84.6%; median age, 2.1 [range, 1.9-2.5] years; 155 female [53.1%] and 137 male [46.9%]) and 90 children of healthy women (84.9%; median age, 2.1 [range, 2.0-2.4] years; 43 female [47.8%] and 47 male [52.2%]) had at least 1 BSID-III domain score. For the primary analyses, 282 children of WWE and 87 children of healthy women had a language domain score at 2 years of age, and 258 children of WWE had both a third-trimester ABL and language domain score. A flowchart of enrollment and reasons for exclusions is depicted in eFigure 1 in Supplement 1.

Demographic characteristics and risk factors for children of WWE and healthy women are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2. The details of MONEAD enrollment and ASM groups have been reported previously.9,22 In brief, of the 266 children who had maternal third-trimester ABLs measured, 157 (59.0%) had mothers with focal epilepsy, and 211 (79.3%) had mothers using monotherapy in the third trimester. Among those receiving monotherapy, 97 (46.0%) used lamotrigine and 70 (33.2%) used levetiracetam. Twenty-five of 55 using polytherapy (45.5%) were using dual therapy with lamotrigine plus levetiracetam (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of 382 Children of WWE and Healthy Women Who Underwent BSID-III Assessment at 2 Years of Age.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of children by maternal group | |

|---|---|---|

| WWE (n = 292) | Healthy women (n = 90) | |

| Child’s sex | ||

| Female | 155 (53.1) | 43 (47.8) |

| Male | 137 (46.9) | 47 (52.2) |

| Child’s race | ||

| White | 236 (80.8) | 58 (64.4) |

| Black or African American | 15 (5.1) | 13 (14.4) |

| Other/unknowna | 41 (14.0) | 19 (21.1) |

| Child’s ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 60 (20.5) | 21 (23.3) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 232 (79.5) | 69 (76.7) |

| Small for gestational age | 17 (6.0) | 9 (10.1) |

| No. missing | 7 | 1 |

| Any breastfeeding | 225 (77.1) | 80 (88.9) |

| Periconceptional folate use | 256 (87.7) | 61 (67.8) |

| Periconceptional folate dose, mg | ||

| 0 | 36 (12.5) | 29 (33.0) |

| >0-0.4 | 23 (8.0) | 12 (13.6) |

| >0.4-1 | 53 (18.3) | 34 (38.6) |

| >1-4 | 155 (53.6) | 13 (14.8) |

| >4 | 22 (7.6) | 0 |

| Missing | 3 | 2 |

| Major congenital malformationsb | 15 (5.1) | 0 |

| Pregnancy planned/welcomed | ||

| Planned | 206 (70.5) | 61 (67.8) |

| Unplanned/welcome | 78 (26.7) | 27 (30.0) |

| Unplanned/unwelcome | 8 (2.7) | 2 (2.2) |

| Depression during pregnancyc | 11 (3.8) | 4 (4.4) |

| Mother’s education | ||

| College degree | ||

| Advanced | 75 (25.7) | 29 (32.2) |

| Not advanced | 135 (46.2) | 36 (40.0) |

| No college degree | 82 (28.1) | 25 (27.8) |

| Mother’s employment | ||

| Unemployedd | 91 (31.2) | 24 (26.7) |

| Employed | ||

| Part-time | 41 (14.0) | 17 (18.9) |

| Full-time | 160 (54.8) | 49 (54.4) |

| Household income, $ | ||

| Declined to answer | 16 (5.5) | 7 (7.8) |

| ≤24 999 | 50 (17.1) | 15 (16.7) |

| 25 000-49 999 | 31 (10.6) | 8 (8.9) |

| 50 000-74 999 | 43 (14.7) | 10 (11.1) |

| 75 000-99 999 | 49 (16.8) | 16 (17.8) |

| ≥100 000 | 103 (35.3) | 34 (37.8) |

| Smokinge | 17 (5.8) | 5 (5.6) |

| Alcohol usee | 67 (22.9) | 32 (35.6) |

| Illicit substance usef | 2 (0.7) | 1 (1.1) |

| No. missing | 0 | 1 |

Abbreviations: BSID-III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition; WWE, women with epilepsy.

Includes Asian/Pacific Islander, multiracial, other/unknown, and declined to answer.

Unlike the present cohort, prior analysis with all children born was not significant.15

Depression based on Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Mood Module at any depression assessment during the pregnancy.

Includes stay-at-home parent without outside job, unemployed due to disability, full-time student, and seeking employment.

Self-reported at any time during pregnancy.

Indicates at any time during pregnancy, excluding marijuana.

Table 2. Continuous Variable Summary for 382 Children of WWE and Healthy Women Who Were Assessed for at Least 1 BSID-III Domain at 2 Years of Age .

| Variable | Maternal group | P valuea | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WWE (n = 292) | Healthy women (n = 90) | |||||||

| No. of children | Mean (SD) | Median (range) | No. of children | Mean (SD) | Median (range) | |||

| Gestational age at birth, wk | 292 | 38.4 (2.1) | 39 (24-42) | 90 | 38.5 (2.0) | 39 (26-43) | .67 | |

| Gestational age at enrollment, wk | 292 | 13.5 (4.5) | 14 (4-27) | 90 | 15.4 (3.9) | 16 (5-23) | <.001 | |

| Birth weight, kg | 286 | 3.20 (0.60) | 3.2 (0.6-4.9) | 90 | 3.21 (0.60) | 3.2 (1.1-5.0) | .93 | |

| Mother’s age at enrollment, y | 292 | 30.9 (5.2) | 31 (18-46) | 90 | 29.8 (5.2) | 31 (15-40) | .07 | |

| Mother’s IQ | 292 | 98.0 (13.0) | 100 (58-123) | 90 | 104.4 (13.1) | 105 (72-131) | <.001 | |

| Father’s IQb | 197 | 104.5 (13.7) | 105 (58-140) | 54 | 102.6 (15.3) | 101 (60-136) | .39 | |

| Maternal relative’s IQb | 109 | 99.9 (16.2) | 101 (51-133) | 30 | 103.0 (11.2) | 103 (74-125) | .32 | |

| Beck Depression Inventory II c | ||||||||

| Enrollment to 2-y visit | 292 | 6.2 (4.9) | 5 (0-31) | 90 | 5.1 (3.8) | 5 (0-24) | .08 | |

| Pregnancy | 292 | 7.0 (5.4) | 6 (0-37) | 90 | 6.0 (4.1) | 5 (0-19) | .17 | |

| Post partum | 292 | 5.8 (5.4) | 4 (0-33) | 90 | 4.4 (4.3) | 4 (0-29) | .04 | |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory c | ||||||||

| Enrollment to 2-y visit | 292 | 5.1 (4.6) | 4 (0-28) | 90 | 3.4 (3.6) | 3 (0-26) | <.001 | |

| Pregnancy | 292 | 6.3 (5.6) | 5 (0-37) | 90 | 4.9 (4.3) | 4 (0-29) | .06 | |

| Post partum | 292 | 4.3 (4.6) | 3 (0-26) | 90 | 2.5 (3.7) | 1 (0-24) | <.001 | |

| 14-Item Perceived Stress Scale c | ||||||||

| Enrollment to 2-y visit | 292 | 17.9 (6.3) | 18 (5-41) | 90 | 16.8 (5.1) | 17 (6-29) | .19 | |

| Pregnancy | 292 | 18.0 (7.0) | 18 (3-40) | 90 | 16.4 (6.0) | 16 (3-31) | .08 | |

| Post partum | 292 | 17.9 (6.8) | 18 (3-41) | 90 | 16.9 (5.5) | 17 (6-33) | .28 | |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index d | ||||||||

| Pregnancy plus postpartum | 226 | 5.7 (2.6) | 5 (0-14) | 70 | 5.1 (2.2) | 5 (1-11) | .08 | |

| Pregnancy | 267 | 5.7 (3.0) | 5 (0-16) | 81 | 4.6 (2.4) | 4 (1-12) | .004 | |

| Post partum | 230 | 5.7 (2.7) | 5 (0-14) | 70 | 5.6 (2.7) | 6 (0-11) | .66 | |

Abbreviations: BSID-III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition; WWE, women with epilepsy.

Calculated from unpaired (independent samples) 2-tailed t test (gestational age at birth, birth weight, IQ scores, age, gestational age at enrollment, and sleep quality) and Wilcoxon rank sum test (depression, anxiety, and stress).

Not included in the forward selection algorithm owing to extensive missing data.

Indicates mean of all assessments completed during the study period. Pregnancy indicates enrollment through day of delivery; post partum, after delivery through 2-year visit.

Indicates mean of all assessments completed during the study period. Pregnancy indicates enrollment through day before delivery; post partum, 6 weeks after delivery through 9 months. Scores are not included in the forward selection algorithm owing to the post hoc nature of the analysis.

No significant differences were observed between children of WWE vs healthy women for the primary language domain outcome (Table 3); significant factors in the full model included the mother’s IQ, educational level, and postpartum anxiety and the child’s ethnicity, sex, and birth weight. Higher maternal IQ (0.3; 95% CI, 0.1-0.4) and child birth weight (3.0; 95% CI, 0.3-5.6) and female child sex (6.4; 95% CI, 3.3-9.4) were associated with higher language domain scores. Children of mothers with lower educational level had lower scores (college degree [not advanced] vs college degree [advanced]: −5.0 [95% CI, −8.8 to −1.2]; no college degree vs college degree [advanced]: −8.3 [95% CI, −13.3 to −3.4]), child Hispanic ethnicity (−9.2; 95% CI, −13.3 to −5.1) and higher postpartum maternal anxiety (−0.5; 95% CI, −0.9 to −0.2) were associated with lower scores. None of the other 4 BSID-III domains differed between children of WWE vs healthy women (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). Findings of sensitivity analyses addressing twins and malformations did not differ from the main results.

Table 3. Full Model Summary: BSID-III Language Domain Scores for Children of WWE and Healthy Women at 2 Years of Age.

| Model parameter | Parameter estimate (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Mother’s study group: WWE vs healthy women | −0.5 (−4.1 to 3.2) | .81 |

| Mother’s IQ | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.4) | <.001 |

| Child’s sex: female vs male | 6.4 (3.3 to 9.4) | <.001 |

| Child’s ethnicity: Hispanic or Latino vs non-Hispanic | −9.2 (−13.3 to −5.1) | <.001 |

| Educational level (3 groups) | .004 | |

| College degree | ||

| Advanced | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Not advanced | −5.0 (−8.8 to −1.2) | .01 |

| No college degree | −8.3 (−13.3 to −3.4) | .001 |

| Postpartum mean BAI score | −0.5 (−0.9 to −0.2) | .004 |

| Birth weight in kilograms | 3.0 (0.3 to 5.6) | .03 |

Abbreviations: BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BSID-III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition; NA, not applicable; WWE, women with epilepsy.

Model R2 = 0.282; variables selected into model using a forward selection algorithm. Mother’s IQ and mother’s study group were included in the model a priori. The Akaike information criterion was used to compare models, and the significance level for covariate entry was set at P = .10.

The mean scores for most domains were higher for children who were receiving folate or breastfeeding, but significant findings were limited to an association between breastfeeding and higher social-emotional domain scores among children of WWE and healthy women (mean social-domain scores for children breastfed vs not breastfed, 107.2 [95% CI, 105.4-109.0] vs 102.7 [95% CI, 98.9-106.5]). Neither periconceptional folate use nor breastfeeding were associated with scores for any of the other BSID-III domains among all children or separately among children of WWE using ASM (eTables 3 and 4 in Supplement 1).

Of the mood measures (for anxiety, depression, and perceived stress), only postpartum anxiety was selected into the language domain main model for both primary analyses using the forward selection algorithm. Postpartum maternal depression was associated with a lower language domain score (−0.41; 95% CI, −0.72 to −0.11). Postpartum maternal anxiety was associated with lower scores in the cognitive (−0.44; 95% CI, −0.73 to −0.15), social-emotional (−0.61; 95% CI, −0.99 to −0.23), and general adaptive (−0.70; 95% CI, −1.06 to −0.33) domains, as were depression (cognitive, −0.48 [95% CI, −0.73 to −0.24]; social-emotional, 0.48 [95% CI, −0.73 to −0.24]; and general adaptive, −0.66 [95% CI, −0.97 to −0.36]) and perceived stress (cognitive, −0.23 [95% CI, −0.41 to −0.04]; social-emotional, −0.67 [95% CI, −0.91 to −0.43]; and general adaptive, −0.37 [95% CI, −0.61 to −0.14]) (eTable 5 in Supplement 1). Poorer postpartum sleep quality was associated with lower scores in the cognitive (−0.63; 95% CI, −1.17 to −0.09), social-emotional (−0.85; 95% CI, −1.56 to −0.14), and general adaptive (−0.75; 95% CI, −1.42 to −0.07) domains among all children (eTable 6A in Supplement 1), but not when restricted to children of WWE on ASM (eTable 6B in Supplement 1).

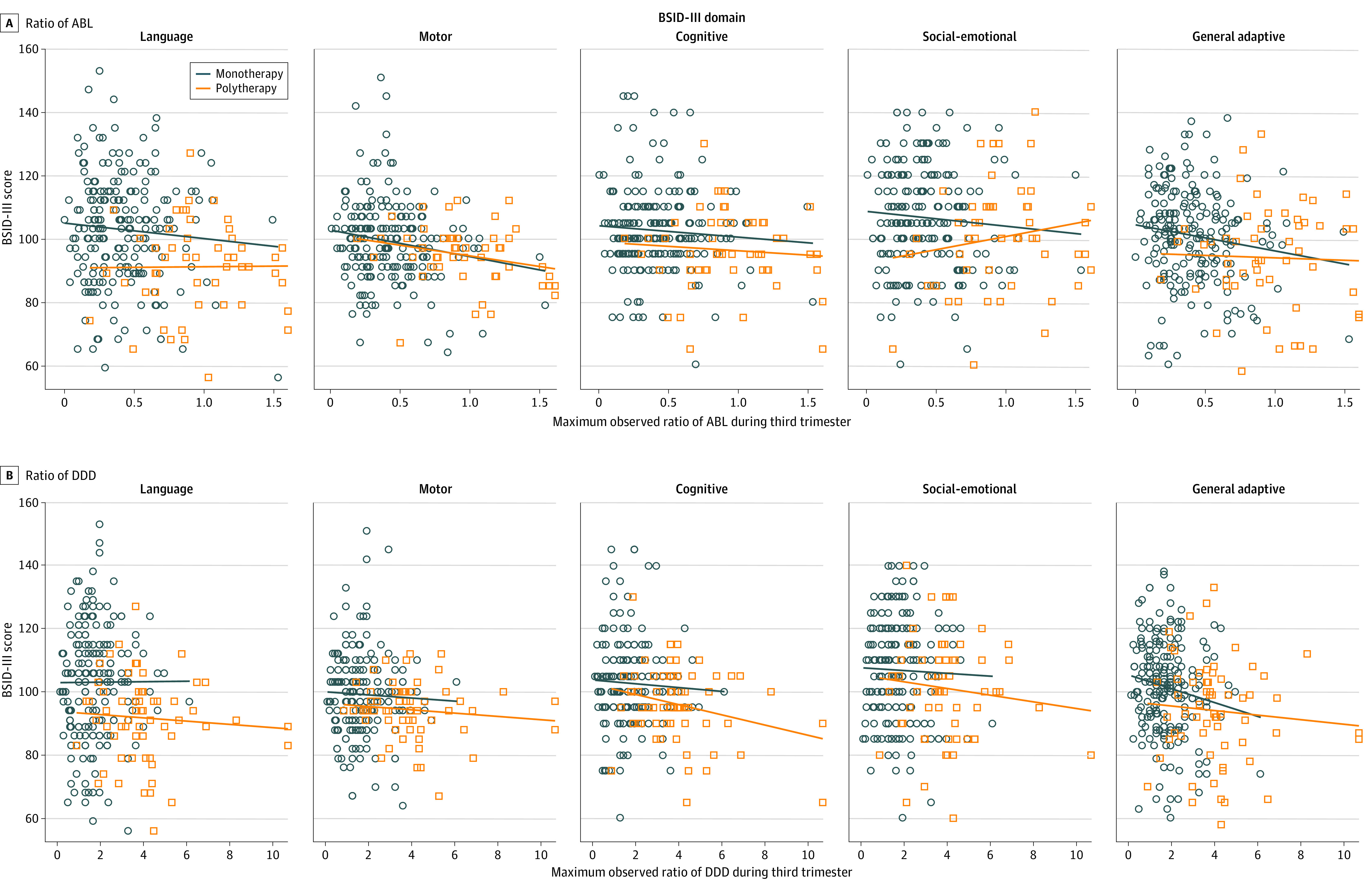

The primary language domain outcome was not associated with third-trimester ratio of ABL. In adjusted analyses, higher maximum third-trimester ABLs were associated with significantly lower BSID-III scores for the motor domain (−5.6; 95% CI, −10.7 to −0.5) and lower scores for the general adaptive domain (−6.1; 95% CI, −12.3 to 0.05) (Table 4 and Figure). In the motor domain, these associations were observed for children of women receiving monotherapy (−8.1; 95% CI, −14.4 to −1.8) and individually for levetiracetam monotherapy during the third trimester (−13.0; 95% CI, −22.1 to −4.0) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1). Similar associations were not significant for the general adaptive domain. In all sensitivity analyses with twins, the association between maximum third-trimester ABLs was significant with the general adaptive domain score (−7.2; 95% CI, −13.9 to −0.5) and with the motor domain score (−6.6; 95% CI, −12.0 to −1.3), when excluding all twins. All other results were similar with the second twin excluded or using the generalized estimating equation model to account for the non-independence of twin pairs. All other results were similar. Analyses of ASM doses revealed that higher maximum ratio of DDD in the third trimester was associated with lower scores in the general adaptive domain (−1.4; 95% CI, −2.8 to −0.05) (Table 4 and Figure).

Table 4. Maximum Observed ABL and ASM Dose During Third Trimester in Children of WWE at BSID-III Domain Assessment at 2 Years of Age.

| BSID-III domain | No. of childrena | Unadjusted analysisb | Adjusted analysisc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter estimate (95% CI) | P value | Parameter estimate (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Maximum ratio of ABL d | |||||

| Language | 258 | −10.3 (−16.2 to −4.3) | <.001 | −4.2 (−10.5 to 2.2) | .20 |

| Motor | 256 | −7.9 (−12.2 to −3.7) | <.001 | −5.6 (−10.7 to −0.5) | .03 |

| Cognitive | 261 | −6.5 (−11.0 to −1.9) | .005 | −2.8 (−7.9 to 2.3) | .28 |

| Social-emotional | 261 | −4.9 (−10.6 to 0.7) | .09 | −0.4 (−6.9 to 6.1) | .90 |

| General adaptive | 259 | −8.8 (−14.0 to −3.5) | .001 | −6.1 (−12.3 to 0.05) | .052 |

| Maximum ratio of DDD e | |||||

| Language | 270 | −1.9 (−3.2 to −0.7) | .003 | −0.3 (−1.7 to 1.0) | .62 |

| Motor | 267 | −1.1 (−2.0 to −0.2) | .03 | −0.1 (−1.2 to 1.0) | .87 |

| Cognitive | 274 | −1.8 (−2.8 to −0.8) | <.001 | −0.9 (−2.0 to 0.3) | .14 |

| Social-emotional | 272 | −1.4 (−2.6 to −0.2) | .03 | −0.5 (−2.0 to 0.9) | .49 |

| General adaptive | 270 | −2.1 (−3.2 to −1.0) | <.001 | −1.4 (−2.8 to −0.05) | .049 |

Abbreviations: ABL, antiseizure medication blood levels; ASM, antiseizure medication; BSID-III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition; DDD, defined daily dose; WWE, women with epilepsy.

Varied owing to missing data.

P values are calculated from the linear regression model.

P values are calculated from the multiple regression model adjusted for the mother’s IQ, educational level, ASM group at enrollment, and postpartum mean Beck Anxiety Inventory score and the child’s ethnicity and sex.

Indicates maximum observed ratio of ABL during the third trimester, calculated as the ratio of the upper limit for therapeutic range. For mothers using polytherapy, the ratio of ABL is calculated as the sum of the ratio of ABL for each ASM. The maximum observed value is recorded during the third trimester (includes day of delivery).

Indicates maximum observed ratio of DDD during the third trimester. For mothers using polytherapy, the ratio of DDD equals the sum across the ratio of DDD for all ASMs.

Figure. Ratios of Antiseizure Medication (ASM) Blood Level (ABL) and Defined Daily Dose (DDD) of ASM.

Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (BSID-III), domain scores vs maximum observed ratios of ABL and DDD during the third trimester by the mother’s ASM group at time of maximum observed level.

Analyses comparing monotherapy vs polytherapy at enrollment were not significant for the language domain or other BSID-III domains (eTables 7 and 8 in Supplement 1). In addition, no significant differences were observed in language domain score across individual ASMs at enrollment (eTable 9 in Supplement 1); however, the sample sizes for several ASMs are small. In sensitivity analyses addressing missing data concerns, children excluded from the analysis population were less likely to have been breastfed (38 of 69 [55.1%] vs 305 of 382 [79.8%]) and were more likely to have mothers with a higher gestational age at enrollment (mean [SD], 15.3 [4.5] vs 13.9 [4.5] weeks), poorer sleep quality scores (mean [SD], 6.4 [2.9] vs 5.5 [2.9]), and higher levels of anxiety (median, 6 [range, 1-38] vs 4 [range, 0-37]) and depression (median, 8 [range, 0-39] vs 6 [range, 0-37]) (eTable 10 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

There was no significant difference in cognitive outcomes at 2 years of age between children of WWE and children of healthy women. This encouraging finding may be due to the use of newer ASMs with lower risk of affecting the immature brain. However, these findings must be interpreted within the context that neuropsychological assessments conducted at 2 years of age are not as strongly associated with adolescent/adult functioning as assessments performed in older children, which will be conducted subsequently in the MONEAD study. The magnitude of these associations is less than that found in previous reports for valproate.3,4,5 Exposure-dependent effects are expected for drug-induced teratogenic effects. Assessments at older ages and in other cohorts are critical.

Language at 2 years of age was associated with higher maternal IQ, maternal educational level, and birth weight, and boys had poorer outcomes. All of these factors are known to be associated with child cognitive outcomes. Hispanic children had lower language scores, a finding that may be related to the family’s primary language. Increased maternal anxiety was associated with poorer child language scores. Although not significant in the full model, maternal depression was associated with language scores. In addition, maternal anxiety, depression, and perceived stress were all associated with child outcomes for the cognitive, social-emotional, and general adaptive domains. As with prior studies,23 these findings highlight the association between maternal mood and child outcomes. Multiple types of therapies can be effective for mood disorders during pregnancy and post partum,24 but the safety of pharmacological therapies is not clear.25 Future studies are needed to examine whether prevention or early intervention in mothers can improve outcomes in their offspring.

Because ASM studies in pregnancy are not randomized, it is important to compare neurodevelopmental outcomes in children of WWE across the available observational studies to seek consistent patterns. Overall, we found no differences at 2 years of age between children of WWE vs children of healthy women. Excluding valproate and phenobarbital,1,2 several studies have found no differences comparing children of WWE with those of healthy women or with normative data from general populations,5,8,26,27,28 but some studies6,29,30,31,32 have found impairments compared with children of healthy women, and another study33 found mixed results. Thus, the association of neurodevelopment with fetal exposure for most ASMs remain uncertain.1

Several studies have demonstrated that valproate poses special risks for both anatomical and neuropsychological outcomes.1 Dose-dependent associations for both malformations and neurodevelopmental deficits have been seen for valproate.1,2,3,4,8,10 The associations with other ASMs are less clear, but data support lower cognitive/behavioral risks for carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and levetiracetam.1,2,5,8 With large samples, dose-dependent associations with congenital malformations have been seen for carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and phenobarbital,10 but exposure-dependent associations with neurobehavioral outcomes have not been reported except for valproate. The present study found exposure-dependent associations with some measures for combined ASM monotherapies and for levetiracetam monotherapy.

Periconceptional folate use has been associated with higher intelligence scores and reduced risk of language delay and autistic behaviors in children of WWE taking ASMs during pregnancy.2,3,4,31,32 In the present study, periconceptional folate use did not show a significant association in children at 2 years of age, but assessment at this age may be less sensitive than at older ages. Previous studies have reported that the magnitude of effects of periconceptional folate is larger at 6 years of age than at 3 years of age.3,4

The previous NEAD study34 found no adverse association with cognitive outcomes of breastfed children of mothers taking ASMs at 3 years of age, which was confirmed in a separate cohort in Norway.35 Subsequently, the NEAD cohort actually showed positive effects of breastfeeding on cognition when tested at 6 years of age.36 In a new cohort in the present study, we found no negative association of breastfeeding with cognition at 2 years of age. Further, we have shown in the MONEAD cohort that ABLs are usually low in nursing infants of mothers using ASMs.37 Thus, it appears that breastfeeding while the mother is taking ASMs is safe and will provide benefits similar to breastfeeding in the general population.

The teratogenic risks for most ASMs are unknown, including long-term neurodevelopmental effects.1 Of the approximately 30 available ASMs, considerable data are available for only 8 ASMs for malformation risks and only 6 ASMs for neurodevelopmental risks. However, even the evidence for those ASMs with considerable data is incomplete, and the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown. For example, teratogens act on a susceptible genetic substrate, but the underlying genetic risk factors are not identified. Progress remains slow given the potential lifelong consequences of fetal ASM-induced deficits.1 Information must be garnered more expediently to reduce unnecessary ASM exposures. Thus, new approaches should be used.1

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include its prospective design with detailed observational data, including multiple confounding factors and formal objective assessment of cognitive abilities in children and their mothers. We used ABLs to assess the association of ASM exposure with outcomes, which is especially important given the clearance changes during pregnancy for most ASMs.

Limitations include a lack of randomization, although ethical and practical issues restrict such studies in pregnancy. Cognitive/behavioral assessments at 2 years of age do not yield associations that are as strong as assessments performed at older ages. Although the distribution of ASMs in the MONEAD study likely reflects current prescribing patterns for WWE at US epilepsy centers,9 it may not reflect that of the general population. Most of the women were taking lamotrigine and/or levetiracetam, and these were the 2 most common ASMs in a large database study,38 but more topiramate and valproate were used than in the MONEAD trial. The sample sizes for many ASMs in the present study were small, precluding individual evaluations.

Conclusions

The results of this observational, multicenter cohort study show no differences between children of WWE and children of healthy women. Further studies in our cohort in children of older ages and in other cohorts are needed to fully delineate the effects of ASM exposure on the immature brain.

eMethods 1. MONEAD Clinical Sites

eMethods 2. Additional Details of Statistical Analyses

eTable 1. ASM and Seizure Variable Summary—Children of WWE With Third-Trimester ASM Blood Levels (ABLs)

eTable 2. 2-Year BSID-III Domain Scores for Children of Women With Epilepsy (WWE) and Healthy Women (HW)

eTable 3. 2-Year BSID-III Domain Scores by Periconceptional Folate Use

eTable 4. 2-Year BSID-III Domain Scores by Breastfeeding

eTable 5. Mother’s Mood Measures (Pregnancy and Post Partum) and 2-Year BSID-III Domain Scores in Children of WWE and HW (n = 382)

eTable 6. Mother’s Sleep Quality (Pregnancy and Post Partum) and 2-Year BSID-III Domain Scores

eTable 7. Full Model Summary: 2-Year BSID-III Language Scores for Children of WWE on ASM

eTable 8. 2-Year BSID-III Domain Scores of Children of Women With Epilepsy on Monotherapy vs Polytherapy Antiseizure Medications at Enrollment

eTable 9. 2-Year BSID-III Language Score in Children of WWE on ASM (n = 271) by Mother's ASM at Enrollment

eTable 10. Variable Summary: Included vs Excluded Subjects, Children of Women With Epilepsy (WWE) and Healthy Women (HW) (N = 451)

eFigure 1. Flowchart of Enrollment and Exclusions

eFigure 2. BSID-III Age 2 Motor Domain Score vs Maximum Observed ASM Blood Levels During the Third Trimester by ASM at Time of Maximum Observed Level

Nonauthor Collaborators. Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) Investigator Group

References

- 1.Meador KJ, Loring DW. Developmental effects of antiepileptic drugs and the need for improved regulations. Neurology. 2016;86(3):297-306. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomson T, Battino D, Bromley R, et al. Management of epilepsy in pregnancy: a report from the International League Against Epilepsy Task Force on Women and Pregnancy. Epileptic Disord. 2019;21(6):497-517. doi: 10.1111/epi.16395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. ; NEAD Study Group . Cognitive function at 3 years of age after fetal exposure to antiepileptic drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1597-1605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. ; NEAD Study Group . Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure and cognitive outcomes at age 6 years (NEAD study): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(3):244-252. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70323-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bromley RL, Calderbank R, Cheyne CP, et al. ; UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register . Cognition in school-age children exposed to levetiracetam, topiramate, or sodium valproate. Neurology. 2016;87(18):1943-1953. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huber-Mollema Y, Oort FJ, Lindhout D, Rodenburg R. Behavioral problems in children of mothers with epilepsy prenatally exposed to valproate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, or levetiracetam monotherapy. Epilepsia. 2019;60(6):1069-1082. doi: 10.1111/epi.15968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huber-Mollema Y, van Iterson L, Oort FJ, Lindhout D, Rodenburg R. Neurocognition after prenatal levetiracetam, lamotrigine, carbamazepine or valproate exposure. J Neurol. 2020;267(6):1724-1736. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09764-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blotière PO, Miranda S, Weill A, et al. Risk of early neurodevelopmental outcomes associated with prenatal exposure to the antiepileptic drugs most commonly used during pregnancy: a French nationwide population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e034829. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meador KJ, Pennell PB, May RC, et al. ; MONEAD Investigator Group . Changes in antiepileptic drug-prescribing patterns in pregnant women with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;84:10-14. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al. ; EURAP Study Group . Dose-dependent risk of malformations with antiepileptic drugs: an analysis of data from the EURAP epilepsy and pregnancy registry. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(7):609-617. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70107-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reisinger TL, Newman M, Loring DW, Pennell PB, Meador KJ. Antiepileptic drug clearance and seizure frequency during pregnancy in women with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;29(1):13-18. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voinescu PE, Park S, Chen LQ, et al. Antiepileptic drug clearances during pregnancy and clinical implications for women with epilepsy. Neurology. 2018;91(13):e1228-e1236. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. 3rd ed. The Psychological Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikonomidou C, Bittigau P, Ishimaru MJ, et al. Ethanol-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration and fetal alcohol syndrome. Science. 2000;287(5455):1056-1060. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adab N, Kini U, Vinten J, et al. The longer term outcome of children born to mothers with epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(11):1575-1583. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.029132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck AT. Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). The Psychological Corporation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory Manual–Revised. The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385-396. doi: 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A, Riemann D, Hohagen F. Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(3):737-740. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00330-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.St Louis EK. Minimizing AED adverse effects: improving quality of life in the interictal state in epilepsy care [published correction appears in Curr Neuropharmacol. 2010;8(1):82]. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2009;7(2):106-114. doi: 10.2174/157015909788848857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology . WHO ATC/DDD Index 2021. Updated December 17, 2020. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/

- 22.Meador KJ, Pennell PB, May RC, et al. ; MONEAD Investigator Group . Fetal loss and malformations in the MONEAD study of pregnant women with epilepsy. Neurology. 2020;94(14):e1502-e1511. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers A, Obst S, Teague SJ, et al. Association between maternal perinatal depression and anxiety and child and adolescent development: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(11):1-11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nillni YI, Mehralizade A, Mayer L, Milanovic S. Treatment of depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders during the perinatal period: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;66:136-148. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutchison SM, Mâsse LC, Pawluski JL, Oberlander TF. Perinatal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and other antidepressant exposure effects on anxiety and depressive behaviors in offspring: a review of findings in humans and rodent models. Reprod Toxicol. 2021;99:80-95. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2020.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaily E, Kantola-Sorsa E, Hiilesmaa V, et al. Normal intelligence in children with prenatal exposure to carbamazepine. Neurology. 2004;62(1):28-32. doi: 10.1212/WNL.62.1.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shallcross R, Bromley RL, Cheyne CP, et al. ; Liverpool and Manchester Neurodevelopment Group; UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register . In utero exposure to levetiracetam vs valproate: development and language at 3 years of age. Neurology. 2014;82(3):213-221. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker GA, Bromley RL, Briggs M, et al. ; Liverpool and Manchester Neurodevelopment Group . IQ at 6 years after in utero exposure to antiepileptic drugs: a controlled cohort study. Neurology. 2015;84(4):382-390. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veiby G, Daltveit AK, Schjølberg S, et al. Exposure to antiepileptic drugs in utero and child development: a prospective population-based study. Epilepsia. 2013;54(8):1462-1472. doi: 10.1111/epi.12226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bjørk M, Riedel B, Spigset O, et al. Association of folic acid supplementation during pregnancy with the risk of autistic traits in children exposed to antiepileptic drugs in utero. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(2):160-168. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.3897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Husebye ESN, Gilhus NE, Riedel B, Spigset O, Daltveit AK, Bjørk MH. Verbal abilities in children of mothers with epilepsy: association to maternal folate status. Neurology. 2018;91(9):e811-e821. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Husebye ESN, Gilhus NE, Spigset O, Daltveit AK, Bjørk MH. Language impairment in children aged 5 and 8 years after antiepileptic drug exposure in utero—the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27(4):667-675. doi: 10.1111/ene.14140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cummings C, Stewart M, Stevenson M, Morrow J, Nelson J. Neurodevelopment of children exposed in utero to lamotrigine, sodium valproate and carbamazepine. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(7):643-647. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.176990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. ; NEAD Study Group . Effects of breastfeeding in children of women taking antiepileptic drugs. Neurology. 2010;75(22):1954-1960. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ffe4a9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veiby G, Engelsen BA, Gilhus NE. Early child development and exposure to antiepileptic drugs prenatally and through breastfeeding: a prospective cohort study on children of women with epilepsy. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(11):1367-1374. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.4290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. ; Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (NEAD) Study Group . Breastfeeding in children of women taking antiepileptic drugs: cognitive outcomes at age 6 years. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(8):729-736. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birnbaum AK, Meador KJ, Karanam A, et al. ; MONEAD Investigator Group . Antiepileptic drug exposure in infants of breastfeeding mothers with epilepsy. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(4):441-450. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim H, Faught E, Thurman DJ, Fishman J, Kalilani L. Antiepileptic drug treatment patterns in women of childbearing age with epilepsy. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(7):783-790. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. MONEAD Clinical Sites

eMethods 2. Additional Details of Statistical Analyses

eTable 1. ASM and Seizure Variable Summary—Children of WWE With Third-Trimester ASM Blood Levels (ABLs)

eTable 2. 2-Year BSID-III Domain Scores for Children of Women With Epilepsy (WWE) and Healthy Women (HW)

eTable 3. 2-Year BSID-III Domain Scores by Periconceptional Folate Use

eTable 4. 2-Year BSID-III Domain Scores by Breastfeeding

eTable 5. Mother’s Mood Measures (Pregnancy and Post Partum) and 2-Year BSID-III Domain Scores in Children of WWE and HW (n = 382)

eTable 6. Mother’s Sleep Quality (Pregnancy and Post Partum) and 2-Year BSID-III Domain Scores

eTable 7. Full Model Summary: 2-Year BSID-III Language Scores for Children of WWE on ASM

eTable 8. 2-Year BSID-III Domain Scores of Children of Women With Epilepsy on Monotherapy vs Polytherapy Antiseizure Medications at Enrollment

eTable 9. 2-Year BSID-III Language Score in Children of WWE on ASM (n = 271) by Mother's ASM at Enrollment

eTable 10. Variable Summary: Included vs Excluded Subjects, Children of Women With Epilepsy (WWE) and Healthy Women (HW) (N = 451)

eFigure 1. Flowchart of Enrollment and Exclusions

eFigure 2. BSID-III Age 2 Motor Domain Score vs Maximum Observed ASM Blood Levels During the Third Trimester by ASM at Time of Maximum Observed Level

Nonauthor Collaborators. Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) Investigator Group