Key Points

Question

Is emergency department pediatric readiness associated with survival in US trauma centers?

Findings

In this cohort study of 372 004 injured children cared for in 832 emergency departments of trauma centers across the US, receiving initial care in an emergency department in the highest quartile of readiness was associated with a 42% lower odds of death. Increasing emergency department pediatric readiness among all trauma centers could save an additional 126 pediatric lives each year in these hospitals.

Meaning

The findings of this cohort study noted that emergency department readiness to care for children was independently associated with improved survival after injury in US trauma centers.

Abstract

Importance

The National Pediatric Readiness Project is a US initiative to improve emergency department (ED) readiness to care for acutely ill and injured children. However, it is unclear whether high ED pediatric readiness is associated with improved survival in US trauma centers.

Objective

To evaluate the association between ED pediatric readiness, in-hospital mortality, and in-hospital complications among injured children presenting to US trauma centers.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective cohort study of 832 EDs in US trauma centers in 50 states and the District of Columbia was conducted using data from January 1, 2012, through December 31, 2017. Injured children younger than 18 years who were admitted, transferred, or with injury-related death in a participating trauma center were included in the analysis. Subgroups included children with an Injury Severity Score (ISS) of 16 or above, indicating overall seriously injured (accounting for all injuries); any Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) score of 3 or above, indicating at least 1 serious injury; a head AIS score of 3 or above, indicating serious brain injury; and need for early use of critical resources.

Exposures

Emergency department pediatric readiness for the initial ED visit, measured through the weighted Pediatric Readiness Score (range, 0-100) from the 2013 National Pediatric Readiness Project ED pediatric readiness assessment.

Main Outcomes and Measures

In-hospital mortality, with a secondary composite outcome of in-hospital mortality or complication. For the primary measurement tools used, the possible range of the AIS is 0 to 6, with 3 or higher indicating a serious injury; the possible range of the ISS is 0 to 75, with 16 or higher indicating serious overall injury. The weighted Pediatric Readiness Score examines and scores 6 domains; in this study, the lowest quartile included scores of 29 to 62 and the highest quartile included scores of 93 to 100.

Results

There were 372 004 injured children (239 273 [64.3%] boys; median age, 10 years [interquartile range, 4-15 years]), including 5700 (1.5%) who died in-hospital and 5018 (1.3%) who developed in-hospital complications. Subgroups included 50 440 children (13.6%) with an ISS of 16 or higher, 124 507 (33.5%) with any AIS score of 3 or higher, 57 368 (15.4%) with a head AIS score of 3 or higher, and 32 671 (8.8%) requiring early use of critical resources. Compared with EDs in the lowest weighted Pediatric Readiness Score quartile, children cared for in the highest ED quartile had lower in-hospital mortality (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.58; 95% CI, 0.45-0.75), but not fewer complications (aOR for the composite outcome 0.88; 95% CI, 0.74-1.04). These findings were consistent across subgroups, strata, and multiple sensitivity analyses. If all children cared for in the lowest-readiness quartiles (1-3) were treated in an ED in the highest quartile of readiness, an additional 126 lives (95% CI, 97-154 lives) might be saved each year in these trauma centers.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, injured children treated in high-readiness EDs had lower mortality compared with similar children in low-readiness EDs, but not fewer complications. These findings support national efforts to increase ED pediatric readiness in US trauma centers that care for children.

This cohort study examines the in-hospital mortality rates of injured children treated in emergency departments within trauma centers by levels of pediatric readiness.

Introduction

Traumatic injury remains the leading cause of death and years of potential life lost among children in the US.1,2 Of the 30 million emergency department (ED) visits by children each year in the US, 27% are injury related.3 Based on a 2006 Institute of Medicine report highlighting disparities in pediatric emergency care,4 the National Pediatric Readiness Project (NPRP) was established as a US quality improvement initiative to ensure that all EDs have the readiness (care coordination, personnel, quality improvement processes, safety processes, policies and procedures, and equipment) to care for acutely ill and injured children.5 Although ED pediatric readiness is based on national guidelines,6 there is sparse evidence to suggest that increased readiness improves health outcomes among injured children.

Previous studies have noted the benefit of trauma systems, trauma centers, and particularly pediatric trauma centers among children with moderate to severe injuries.7,8,9,10,11,12 However, there is large variability in ED pediatric readiness among US trauma centers,13 which may explain some of the inconsistencies in survival between different types of trauma centers caring for children. To our knowledge, the only study to date linking ED pediatric readiness to improved survival included critically ill children in 5 states,14 but the study did not focus on trauma centers. Evaluating the association between ED care and outcomes for injured children could inform the organization and verification processes of US trauma systems. We evaluated the association between ED pediatric readiness, in-hospital mortality, and in-hospital complications among injured children presenting to 832 trauma center EDs across the US.

Methods

Design

We performed a retrospective cohort study that was reviewed and approved by institutional review boards at Oregon Health & Science University and the University of Utah School of Medicine, which waived the requirement for informed consent based on the use of existing data, observational study design, and minimal risk study. We used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.15

We included 832 trauma centers (levels 1 to 5, adult and pediatric) in 50 states and the District of Columbia that submitted pediatric data to the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB). In the US, trauma centers are categorized based on their resources and ability to care for injured patients, with level 1 hospitals providing the most comprehensive care and level 4 to 5 hospitals serving as smaller institutions to supplement care within larger trauma systems.16 The NTDB data are collected using the National Trauma Data Standard,17 which uses standardized inclusion criteria and data fields to capture information on initial ED presentation, physiology, injury severity, procedures, intensive care, complications, and mortality.

Patient Population

Patients included injured children younger than 18 years meeting standardized NTDB inclusion criteria (an injury diagnosis with hospital admission, interhospital transfer, or injury-related death in a participating trauma center)18 from January 1, 2012, through December 31, 2017, linked to the 2013 NPRP ED pediatric readiness assessment. For children subsequently transferred to another trauma center, we matched available records from the second hospital using probabilistic linkage.19 We excluded children who were dead on arrival, missing the initial ED record, or treated in EDs without a matched NPRP assessment (eFigure in Supplement 1). We prespecified 4 subgroups of seriously injured children likely to be sensitive to ED pediatric readiness: Injury Severity Score (ISS) of 16 or higher (score range, 0-75; ≥16 indicates serious overall injury)20,21,22 any injury of Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) score of 3 or higher severity (score range, 0-6; ≥3 indicates serious injury),21 head AIS score of 3 or higher (serious brain injury), and children requiring early use of critical resources.23 We defined early critical resources based on a consensus definition23 that included any of the following within 24 hours of ED presentation: advanced airway management; tube thoracostomy; blood transfusion; pericardiocentesis; thoracotomy; brain, chest, abdominal-pelvic, spine, vascular, or neck surgery; interventional radiologic procedure; emergent cesarean section; vasopressor support; intracranial pressure monitoring; or presence of spinal cord injury (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

The primary exposure variable was overall ED pediatric readiness for the initial ED, measured using the weighted Pediatric Readiness Score (wPRS) from the 2013 NPRP assessment.24 The NPRP assessment was a national 55-question assessment of US EDs providing emergency care 24 hours a day 7 days per week, based on the 2009 guidelines for children cared for in the ED.6 Emergency department nurse managers completed the assessment from January 1 through August 31, 2013 (1 state piloted the tool in 2012), with a 83% response rate.24 The wPRS is a weighted score from 0 to 100 based on questions in 6 domains, with 100 representing the highest level of ED pediatric readiness (meeting all ED guidelines).24 To develop the weighting scheme, a national work group of stakeholders and organizations assigned weights to each readiness domain and then used a modified Delphi process to generate a mean point score and relative value for each domain.25 Members graded questions based on clinical relevance, with retention of questions with moderate to high importance.25 The wPRS has been used to quantify ED pediatric readiness across US hospitals24 and trauma centers.13 The domains and maximum weighted point scores were care coordination, 19 points; physician/nurse ED personnel, 10 points; quality improvement, 7 points; patient safety, 14 points; policies and procedures, 17 points; and equipment and supplies, 33 points.24 We linked the NPRP assessment data to the initial trauma center ED using hospital name, address, and zip code.

Variables and Outcomes

Patient-level variables included demographic characteristics (age, sex, and race); comorbidities; initial ED systolic blood pressure and Glasgow Coma Scale score; emergent airway intervention; mechanism of injury; mode of arrival; AIS score21; ISS20,21; hospital procedures; blood transfusion; interhospital transfer; and length of hospital stay. To maximize information on ED and hospital procedures, we used a combination of abstracted NTDB data fields and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision procedure codes, categorized using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classification System.26 We then mapped Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classification System categories to standardized operative domains for trauma (brain, spine, neck, chest, abdominal-pelvic, and orthopedic), airway management, and blood transfusion.

To define trauma center level (1-5) and type (adult and pediatric), we used the following hierarchy: American College of Surgeons verification status, state-level designation, NPRP assessment, and the annual American Hospital Association survey.27 We also evaluated annual ED pediatric volume and pediatric trauma volume.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. We used a composite secondary outcome of in-hospital death or any in-hospital complication. Complications included standardized serious in-hospital events systematically recorded in the NTDB: acute respiratory distress syndrome, venous thromboembolism, acute kidney injury, surgical complications (eg, surgical site infections, graft failure, unplanned return to operating room), catheter-associated urinary tract infection, pneumonia (ventilator and nonventilator associated), decubitus ulcer, osteomyelitis, severe sepsis, and unplanned admission to the intensive care unit.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize children and hospitals by quartile of ED pediatric readiness. To evaluate the association between ED readiness and patient outcomes, we used a hierarchical, mixed-effects logistic regression model based on a standardized risk-adjustment model for trauma,28 with a random intercept to account for clustering by the initial ED (PROC GLIMMIX in SAS, version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc). The unit of analysis was the patient. The model included patient demographic characteristics; comorbidities; initial physiology (Glasgow Coma Scale score and age-adjusted hypotension29), emergent airway intervention, mechanism of injury, ISS, transfer status, blood transfusion, nonorthopedic surgery, orthopedic surgery, and geographic region. We evaluated ED pediatric readiness by quartile of wPRS at the ED level, using the lowest quartile as the reference group, and tested for linear trends across adjusted odds ratios (aORs). We also analyzed wPRS as a continuous variable using fractional polynomials30 to assess nonlinear associations with outcomes (Stata, version 15; StataCorp LLC). Fractional polynomials are a family of different curves, with a standardized process for testing and identifying the curve that best fits the adjusted association between predictor (wPRS) and outcome.30,31 To isolate the association between ED readiness and complications, we analyzed 2 additional models: restricted to survivors (outcome = in-hospital complications) and a multinomial logit model (outcomes = survival without complications, survival with complications, or death). We assessed model appropriateness and fit using the C statistic, tests for multicollinearity, assessment of influential values, and diagnostic plots. Preplanned subgroup and stratified analyses included seriously injured children, transfer status, age, and calendar year. We tested the robustness of our findings by adding hospital-level variables and calendar year sequentially to the models. For models with small cells owing to certain hospital characteristics, we used adaptive quadrature to minimize bias and provide efficient estimates.32

To quantify the potential outcome of ED pediatric readiness, we estimated the annual number of additional lives saved by increasing the proportion of children treated in EDs in the highest readiness quartile either by shifting the location of care or by raising the level of ED readiness. We estimated marginal predicted probabilities of mortality from the multivariable model to calculate additional lives saved if 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% of injured children originally cared for in lower readiness EDs (quartiles 1-3) had received care in a high-readiness ED (quartile 4). We calculated 95% CIs using the bootstrap method with an adjustment for correlation between regression coefficients.

Missingness for individual variables ranged from 0% to 10.4% (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). To reduce bias and preserve the study sample, we used multiple imputation33,34 to handle missing values, the validity of which has been reported for trauma data.35,36,37,38 We generated 10 multiply imputed data sets39 using multiple imputation via chained equations, as implemented by the mi impute chained command in Stata software,40,41 then combined the results using Rubin’s rules to account for within- and between-data set variance.34 The level of significance was designated α <.05.

Results

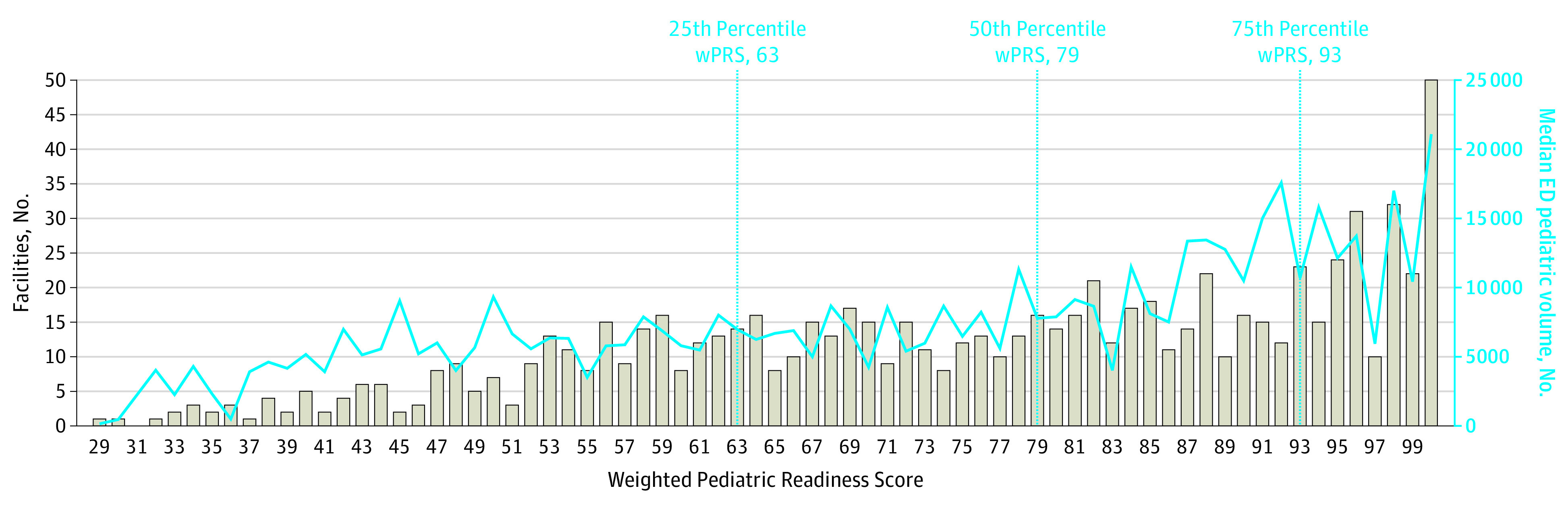

There were 372 004 children (239273 [64.3%] boys; 132 731 [35.7%] girls; median age, 10 years [interquartile range (IQR), 4-15 years]) included in the cohort. Of these, 5700 children (1.5%) died during their hospital stay, 5018 (1.3%) had in-hospital complications, and 10 375 (2.8%) died or had complications. Among the 5700 children who died, death occurred a median of 1 day (IQR, 0-3 days) after ED arrival. Subgroups included 50 440 children (13.6%) with an ISS of 16 or higher, 124 507 (33.5%) with any AIS score of 3 or higher, 57 368 (15.4%) with a head AIS score of 3 or higher, and 32 671 (8.8%) requiring early use of critical resources. The median ISS was 4 (IQR, 4-9). We characterize children in the sample in Table 1. Among the 832 trauma center EDs, the median wPRS was 79 (IQR, 63-93; range, 29-100) (Figure 1). For the 217 EDs in the lowest quartile of readiness (29-62), 77 (35.5%) were level 1 and 2 trauma centers (73 adult, 4 pediatric/adult). Among the 195 EDs in the highest quartile of readiness (93-100), 168 EDs (84.8%) were level 1 and 2 trauma centers (84 adult, 42 pediatric, 42 adult/pediatric). We describe the EDs in eTable 3 in Supplement 1.

Table 1. Injured Children Presenting to 832 US Trauma Center EDs by Quartile of ED Pediatric Readiness.

| Variable | Overall, No. (%) | ED pediatric readiness, quartile, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st, wPRS 29-62 | 2nd, wPRS 63-78 | 3rd, wPRS 79-92 | 4th, wPRS 93-100 | ||

| Patients | 372 004 (100) | 40 981 (11.0) | 48 459 (13.0) | 100 633 (27.1) | 181 931 (48.9) |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 10 (4-15) | 12 (5-16) | 11 (5-15) | 11 (5-15) | 9 (4-14) |

| Age group, y | |||||

| 0-4 | 97 431 (26.2) | 9258 (22.6) | 10 990 (22.7) | 24 484 (24.3) | 52 699 (28.9) |

| 5-12 | 130 614 (35.1) | 12 308 (30.0) | 15 611 (32.2) | 34 521 (34.3) | 68 174 (37.4) |

| 13-15 | 70 672 (19.0) | 8180 (20.0) | 9787 (20.2) | 19 625 (19.5) | 33 080 (18.1) |

| 16-17 | 73 287 (19.7) | 11 235 (27.4) | 12 071 (24.9) | 22 003 (21.9) | 27 978 (15.3) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||||

| Male | 239 273 (64.3) | 26 890 (65.6) | 31 563 (65.1) | 65 551 (65.1) | 115 269 (63.4) |

| Female | 132 731 (35.7) | 14 091 (34.4) | 16 896 (34.9) | 35 082 (34.9) | 66 662 (36.6) |

| Race | |||||

| Black | 77 976 (20.9) | 6679 (16.3) | 9347 (19.3) | 21 823 (21.7) | 40 127 (22.0) |

| Asian | 8206 (2.2) | 966 (2.4) | 791 (1.6) | 2339 (2.3) | 4111 (2.3) |

| Other/multiple | 56 377 (15.2) | 5693 (13.9) | 5441 (11.2) | 15 828 (15.7) | 29 414 (16.1) |

| White | 229 445 (61.7) | 27 643 (67.5) | 32 881 (67.9) | 60 643 (60.3) | 108 278 (59.4) |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| None | 340 026 (91.4) | 37 570 (91.7) | 43 998 (90.8) | 91 994 (91.4) | 166 464 (91.3) |

| 1 | 28 463 (7.7) | 3036 (7.4) | 3968 (8.2) | 7733 (7.7) | 13 726 (7.5) |

| ≥2 | 3515 (0.9) | 375 (0.9) | 493 (1.0) | 906 (0.9) | 1741 (1.0) |

| Mechanism of injury | |||||

| GSW | 13 708 (3.7) | 1923 (4.7) | 1941 (4.0) | 4490 (4.5) | 5354 (2.9) |

| Stab or penetrating injury | 11 417 (3.1) | 1249 (3.0) | 1382 (2.9) | 3065 (3.0) | 5721 (3.1) |

| Burn | 15 065 (4.0) | 1625 (4.0) | 1992 (4.1) | 3788 (3.8) | 7660 (4.2) |

| Assault | 40 816 (11.0) | 4585 (11.2) | 5256 (10.8) | 11 140 (11.1) | 19 837 (10.9) |

| Fall | 141 310 (37.9) | 14 931 (36.4) | 17 832 (36.8) | 36 225 (36.0) | 72 321 (39.7) |

| Motor vehicle | 68 248 (18.3) | 8235 (20.1) | 9751 (20.1) | 19 841 (19.7) | 30 421 (16.7) |

| Bicycle | 18 811 (5.1) | 2114 (5.2) | 2500 (5.2) | 5355 (5.3) | 8842 (4.8) |

| Pedestrian | 23 170 (6.2) | 2156 (5.3) | 2622 (5.4) | 6393 (6.4) | 11 998 (6.6) |

| Other | 39 459 (10.6) | 4164 (10.2) | 5182 (10.7) | 10 336 (10.3) | 19 777 (10.8) |

| Arrival by ambulance | 212 780 (57.1) | 22 233 (54.3) | 26 508 (54.7) | 58 901 (58.5) | 105 139 (57.7) |

| Initial hospital adult trauma level | |||||

| 1 | 119 369 (32.1) | 9560 (23.3) | 13 264 (27.4) | 40 734 (40.5) | 55 811 (30.6) |

| 2 | 93 681 (25.2) | 17 249 (42.1) | 20 256 (41.8) | 26 961 (26.8) | 29 215 (16.0) |

| 3/4 | 43 399 (11.7) | 14 172 (34.6) | 13 237 (27.3) | 12 256 (12.2) | 3734 (2.0) |

| NA (pediatric trauma centers) | 93 681 (25.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1702 (3.5) | 20 682 (20.6) | 29 215 (16.0) |

| Initial hospital pediatric trauma level | |||||

| 1 | 142 806 (38.4) | 1845 (4.5) | 3928 (8.1) | 24 571 (24.4) | 112 462 (61.8) |

| 2 | 62 455 (16.8) | 1948 (4.8) | 5688 (11.7) | 26 888 (26.7) | 27 931 (15.4) |

| 3-4 | 5666 (1.5) | 245 (0.6) | 2119 (4.4) | 1948 (1.9) | 1354 (0.7) |

| NA (adult trauma level only) | 161 077 (43.3) | 36 943 (90.1) | 36 724 (75.8) | 47 226 (46.9) | 40 184 (22.1) |

| ED initial physiology | |||||

| Age-adjusted hypotension | 5520 (1.5) | 667 (1.6) | 733 (1.5) | 1641 (1.6) | 2479 (1.4) |

| GCS | |||||

| 13-15 | 348 873 (93.7) | 38 575 (94.1) | 45 521 (93.9) | 94 000 (93.4) | 170 778 (93.7) |

| 9-12 | 8197 (2.2) | 849 (2.1) | 1072 (2.2) | 2267 (2.3) | 4008 (2.2) |

| ≤8 | 14 935 (4.0) | 1558 (3.8) | 1866 (3.9) | 4366 (4.3) | 7145 (3.9) |

| Injury severity | |||||

| ISS | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 4 (4-9) | 4 (4-9) | 4 (4-9) | 4 (4-9) | 4 (4-9) |

| 0-8 | 244 981 (65.9) | 27 049 (66.0) | 31 508 (65.0) | 65 958 (65.5) | 120 466 (66.2) |

| 9-15 | 76 972 (20.7) | 8457 (20.6) | 10 552 (21.8) | 20 834 (20.7) | 37 131 (20.4) |

| 16-24 | 30 649 (8.2) | 3377 (8.2) | 3861 (8.0) | 8374 (8.3) | 15 038 (8.3) |

| ≥25 | 19 402 (5.2) | 2099 (5.1) | 2539 (5.2) | 5468 (5.4) | 9296 (5.1) |

| AIS score ≥3 | |||||

| Head | 52 063 (14.0) | 5518 (13.5) | 6590 (13.6) | 14 299 (14.2) | 25 656 (14.1) |

| Chest | 30 225 (8.1) | 3855 (9.4) | 4585 (9.5) | 9033 (9.0) | 12 752 (7.0) |

| Abdominal-pelvic | 14 945 (4.0) | 1872 (4.6) | 2274 (4.7) | 4170 (4.1) | 6629 (3.6) |

| Extremity | 47 485 (12.8) | 5193 (12.7) | 6569 (13.6) | 12 531 (12.5) | 23 193 (12.7) |

| Hospitalization | |||||

| Emergent airway/mechanical ventilation | 34 803 (9.3) | 4416 (10.8) | 4924 (10.2) | 10 440 (10.4) | 15 023 (8.2) |

| Blood transfusion | 12 436 (3.3) | 1420 (3.5) | 1884 (3.9) | 3649 (3.6) | 5483 (3.0) |

| Nonorthopedic surgerya | 28 876 (7.8) | 3062 (7.5) | 3753 (7.7) | 7944 (7.9) | 14 118 (7.7) |

| Orthopedic surgery | 118 645 (31.9) | 11 587 (28.3) | 14 384 (29.7) | 31 277 (31.1) | 61 398 (33.7) |

| Interhospital transfer | |||||

| None | 317 005 (85.1) | 28 993 (70.7) | 32 905 (67.9) | 84 495 (84.0) | 170 612 (93.6) |

| From the ED | 51 048 (13.7) | 11 304 (27.6) | 14 937 (30.8) | 14 763 (14.7) | 10 044 (5.5) |

| From inpatient | 3951 (1.1) | 684 (1.7) | 617 (1.3) | 1375 (1.4) | 1275 (0.7) |

| Length of stay, median (IQR), d | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) |

| In-hospital outcomes | |||||

| Mortality | 5700 (1.5) | 570 (1.4) | 815 (1.7) | 2226 (2.2) | 2091 (1.1) |

| ≥1 Complication | 5018 (1.3) | 558 (1.4) | 635 (1.3) | 1520 (1.5) | 2305 (1.3) |

| Composite | |||||

| Alive with no complications | 361 629 (97.1) | 39 889 (97.3) | 47 043 (97.1) | 97 020 (96.4) | 177 677 (97.4) |

| Alive with ≥1 complication | 4675 (1.3) | 522 (1.3) | 601 (1.2) | 1388 (1.4) | 2164 (1.2) |

| Died with ≥1 complication | 343 (0.1) | 36 (0.1) | 33 (0.1) | 133 (0.1) | 142 (0.1) |

| Died with no complications | 5357 (1.4) | 534 (1.3) | 781 (1.6) | 2093 (2.1) | 1949 (1.1) |

Abbreviations: AIS, Abbreviated Injury Scale; ED, emergency department; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; GSW, gunshot wound; IQR, interquartile range; ISS, Injury Severity Score; NA, not applicable; wPRS, weighted Pediatric Readiness Score.

Nonorthopedic surgery included brain, spine, thoracic, abdominal, or neck surgeries.

Figure 1. Emergency Department (ED) Pediatric Readiness and Annual ED Pediatric Volume in 832 Trauma Center EDs.

Gray bars indicate the number of EDs at each weighted pediatric readiness score (wPRS) and the blue line indicates the median annual ED volume of children at each wPRS.

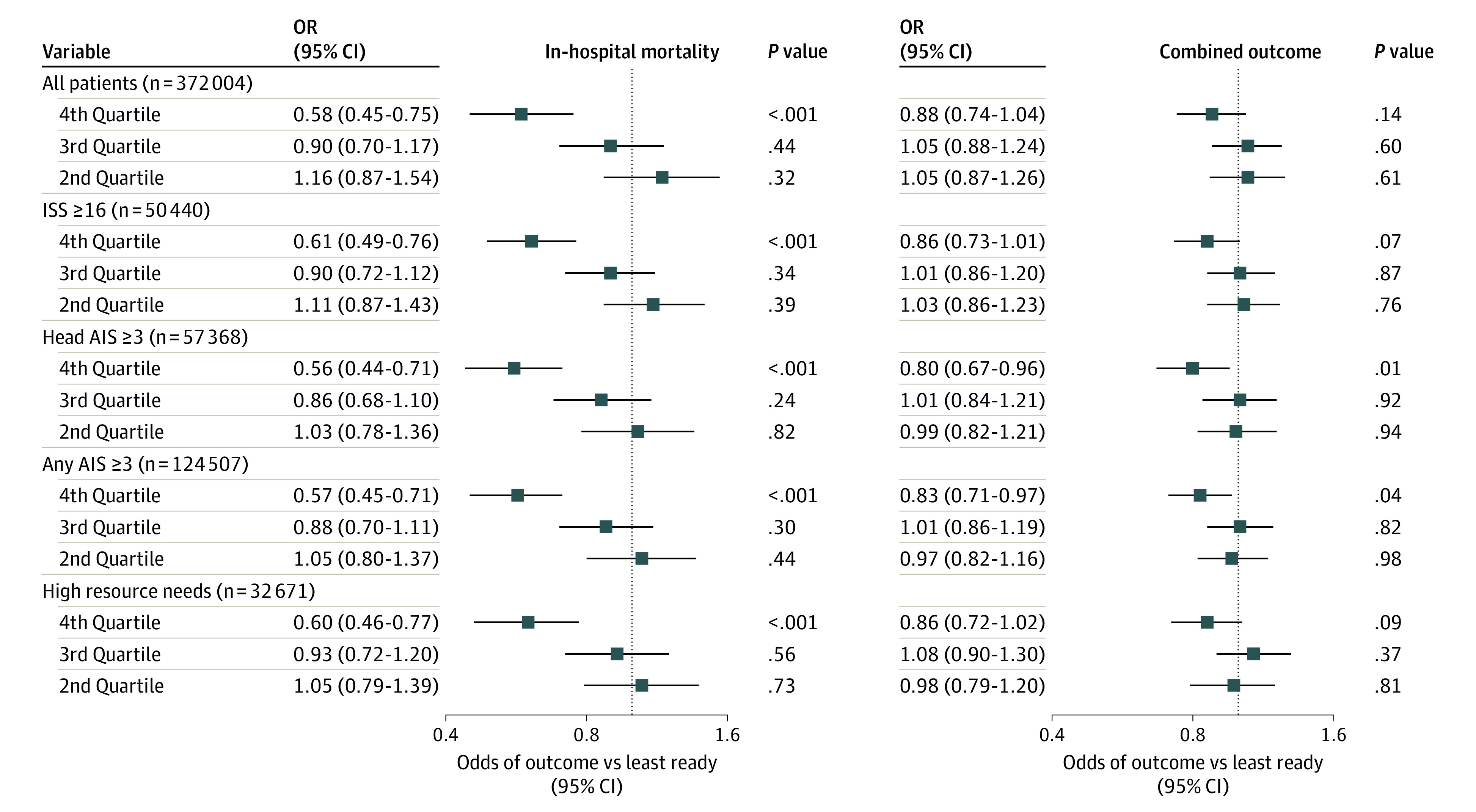

In-hospital mortality was lower among children initially cared for in EDs in the highest quartile of pediatric readiness compared with the lowest quartile (aOR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.45-0.75) (Table 2). Subgroup results were similar (Figure 2). There was no association between ED readiness and the composite outcome of in-hospital death or complications (aOR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.74-1.04), with similar findings in 2 of the 4 subgroups (Figure 2). There was a linear trend across aORs for decreasing mortality with increasing wPRS in the primary cohort (P = .001), but not for the composite outcome (P = .16). A model restricted to survivors (366 299 [98.5%] of the sample) did not show an association between ED pediatric readiness and complications (fourth vs first quartile ED pediatric readiness aOR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.95-1.36). Similarly, there was no association between ED readiness and complications in the multinomial logit model (aOR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.97-1.38 for survival with complications vs complication-free survival; aOR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.48-0.79 for mortality vs complication-free survival).

Table 2. Multivariable Models of ED Pediatric Readiness and Patient Outcomes for 372 004 Injured Children Presenting to 832 US Trauma Centers.

| Variable | In-hospital mortality, OR (95% CI) | In-hospital mortality or complication, OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| ED Pediatric Readiness Score, quartilea | ||

| 1st (Least ready) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 2nd | 1.16 (0.87-1.54) | 1.05 (0.87-1.26) |

| 3rd | 0.90 (0.70-1.17) | 1.05 (0.88-1.24) |

| 4th (Most ready) | 0.58 (0.45-0.75) | 0.88 (0.74-1.04) |

| Female sex | 0.99 (0.91-1.08) | 0.98 (0.92-1.04) |

| Age group, y | ||

| 0-4 | 1.37 (1.22-1.55) | 0.93 (0.85-1.01) |

| 5-12 | 1.35 (1.20-1.51) | 0.84 (0.78-0.91) |

| 13-15 | 1.02 (0.91-1.15) | 0.89 (0.82-0.97) |

| 16-17 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Race | ||

| White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Black | 0.94 (0.85-1.04) | 0.99 (0.92-1.06) |

| Asian | 0.92 (0.69-1.23) | 0.93 (0.75-1.16) |

| Other | 1.22 (1.10-1.36) | 1.16 (1.06-1.26) |

| Any comorbid condition | 0.62 (0.55-0.70) | 1.12 (1.04-1.21) |

| Injury mechanism | ||

| GSW | 4.68 (3.99-5.48) | 3.01 (2.67-3.40) |

| Stabbing or other penetrating injury | 1.15 (0.85-1.56) | 1.30 (1.07-1.58) |

| Burn, fire, flame | 1.83 (1.36-2.46) | 2.32 (1.91-2.81) |

| Assault | 1.10 (0.94-1.29) | 1.13 (0.98-1.29) |

| Fall | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Motor vehicle | 0.62 (0.54-0.71) | 0.94 (0.85-1.04) |

| Bicycle | 0.81 (0.65-1.02) | 1.02 (0.87-1.21) |

| Pedestrian vs motor vehicle | 0.99 (0.85-1.15) | 1.14 (1.01-1.30) |

| Other | 1.40 (1.23-1.61) | 1.73 (1.57-1.91) |

| Arrival by ambulance | 0.97 (0.85-1.09) | 1.40 (1.28-1.52) |

| Transfer to another hospital | 0.35 (0.30-0.40) | 0.97 (0.87-1.08) |

| Age-adjusted hypotension | 5.33 (4.72-6.02) | 3.23 (2.93-3.56) |

| GCS | ||

| ≤8 | 40.3 (33.65-48.26) | 6.04 (5.54-6.59) |

| 9-12 | 2.39 (1.74-3.29) | 1.38 (1.22-1.57) |

| ≥13 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Injury Severity Score | 1.05 (1.04-1.05) | 1.05 (1.04-1.05) |

| Orthopedic surgery | 0.62 (0.56-0.68) | 1.20 (1.13-1.28) |

| Airway or ventilation support | 2.66 (2.26-3.12) | 4.75 (4.34-5.19) |

| Major nonorthopedic surgery b | 1.07 (0.97-1.18) | 1.98 (1.85-2.11) |

| Blood transfusion (any) | 2.42 (2.18-2.67) | 2.34 (2.17-2.52) |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; GSW, gunshot wound; OR, odds ratio.

Pediatric readiness was measured using the weighted Pediatric Readiness Score. For in-hospital mortality, linear trend was significant at P = .001; for in-hospital mortality or complication, linear trend was nonsignificant at P = .16.

Major nonorthopedic surgery included brain, spine, neck, thoracic, or abdominal operations.

Figure 2. Adjusted In-Hospital Mortality and Composite Outcome (In-Hospital Mortality or Complication) Across Quartiles of Emergency Department (ED) Pediatric Readiness for Injured Children.

ED pediatric readiness was measured using the weighted Pediatric Readiness Score (wPRS). The x-axis is in the natural logarithm (ln) scale.

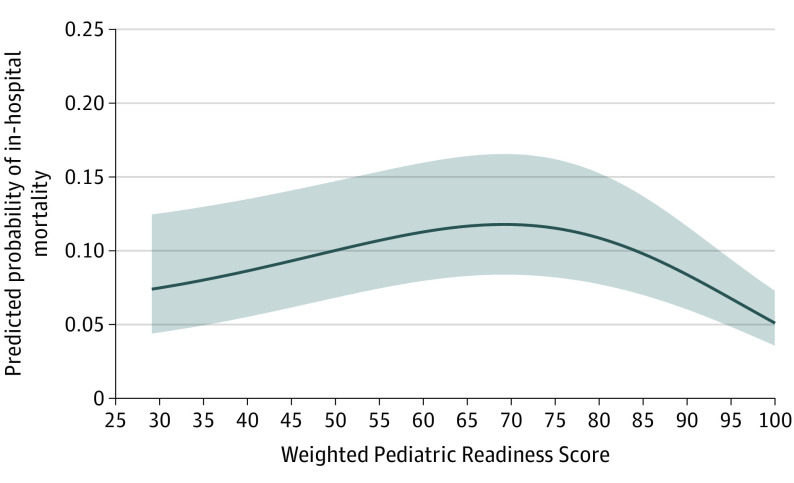

In a model using risk-adjusted best-fit fractional polynomials, the curves for wPRS vs predicted mortality for the full cohort demonstrated the most pronounced mortality reduction at the highest levels of ED pediatric readiness (Figure 3). In this curve, mortality reduction did not reach statistical significance until wPRS values were higher than 90, with continued mortality reduction to the maximum wPRS of 100.

Figure 3. Adjusted In-Hospital Mortality for 372 004 Injured Children Across the Spectrum of Emergency Department (ED) Pediatric Readiness Using Best-Fit Fractional Polynomials.

The figure was generated using best-fit fractional polynomials to model the association between the weighted Pediatric Readiness Score and in-hospital mortality from the risk-adjustment model using a patient with the following characteristics: male, age 5 to 12 years, White race, no comorbidities, no surgical intervention, mean Injury Severity Score (ISS), motor vehicle crash mechanism, arrival by ambulance, no transfer, hypotension, Glasgow Coma Scale score 9 to 12, intubation, and blood transfusion. Graphs generated using patients with different characteristics were similar in shape, but with higher or lower values for predicted in-hospital mortality.

To estimate the potential of increasing the proportion of children seen in high-readiness EDs, we calculated the mean number of additional lives saved per year if 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% of children cared for in lower-readiness quartile EDs were treated in an ED in the highest quartile of readiness. These scenarios would have resulted in 31 additional lives saved per year (95% CI, 23-38 lives) at the 25% level, 63 lives (95% CI, 49-77 lives) at the 50% level, 94 lives (95% CI, 72-116 lives) at the 75% level, and 126 lives (95% CI, 97-154 lives) at the 100% level among these trauma centers (eTable 4 in Supplement 1).

Emergency department pediatric readiness was associated with in-hospital mortality in analyses stratified by transfer status (eTable 5 in Supplement 1), age group (eTable 6 in Supplement 1), and calendar year (eTable 7 in Supplement 1), but not with the composite outcome. In age-stratified analyses, the survival benefit of ED readiness persisted through age 15 years, but was not evident among adolescents aged 16 to 17 years. Emergency department pediatric readiness was associated with mortality after accounting for pediatric trauma center level, annual pediatric trauma volume, annual overall ED pediatric volume, and year, but not when adult trauma center level was added (eTable 8 in Supplement 1). Model diagnostics indicated an appropriate model fit, lack of multicollinearity, and a C statistic of 0.98.

Discussion

In this study, we noted that injured children cared for in trauma center EDs with high pediatric readiness had improved in-hospital survival, but not fewer complications. These findings were consistent across multiple subgroups, strata, and after accounting for hospital-level characteristics. The results suggest that ED readiness is an important component of early trauma care in reducing preventable mortality among children.

Our findings could have implications for national trauma policy. Although previous research has shown large variability in ED pediatric readiness among US trauma centers,13 we suggest that this variability is associated with excess mortality. We also quantified the survival outcome of increasing ED pediatric readiness among US trauma centers. One option for encouraging high ED readiness is integration to the trauma center verification process. Requiring high ED pediatric readiness in all trauma centers would also ensure appropriate ED selection for injured children transported by emergency medical services using the national field trauma triage guidelines.42 Other national efforts, such as the American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program, could consider integrating measures of ED pediatric readiness to the assessment and comparison of trauma centers caring for children.

The study provides data on the level of readiness a trauma center ED needs to reduce mortality among injured children. A recent study of critically ill children found that in-hospital mortality began to decrease above an ED wPRS of 59, yet the study was not limited to trauma centers or injured children.14 The wPRS threshold to begin reducing mortality was notably higher in our sample. The fractional polynomial analyses generated parabolic curves, suggesting lower mortality in low-readiness EDs than EDs in the midrange of readiness, but this finding may reflect unmeasured confounding in the selection of the initial hospital. For example, if children with lower-acuity conditions with better prognosis tended to be transported to lower-readiness EDs (eg, due to parent preference, local field triage protocols, or proximity), this scenario could have created confounding. A previous study reported a similar phenomenon.14 A consistent finding, whether using quartiles or fractional polynomials, was the lack of a measurable mortality reduction until the highest levels of ED pediatric readiness (wPRS 93-100) were achieved, providing a benchmark for US trauma centers.

There were important differences in the association between ED readiness and varying outcomes. Although we found a consistent association between high ED readiness and reduced mortality, there was no consistent association with complications, likely reflecting a temporal association between ED care and different outcomes. Among children who died, mortality generally occurred early in the clinical course and in-hospital complications tended to occur later in a hospital course among survivors. That is, mortality is a more proximate outcome to ED care and more likely to be influenced by the quality of early care. This association further highlights the important role of the initial ED care, regardless of whether a child is subsequently transferred to another hospital.

The association between ED readiness and reduced mortality was not limited to seriously injured children; instead, the association was consistent across a heterogeneous cohort. Previous research showing the benefit of trauma centers and trauma systems has generally focused on more seriously injured children.7,8,9,10 Our findings suggest that ED pediatric readiness is associated with survival for children across a range of injury types and severities. Younger children appeared to derive greater benefit from high-readiness EDs, with a less-pronounced association among older adolescents. This finding might reflect the need for specialized training, personnel, experience, and equipment to care for younger children in emergency circumstances.

Limitations

There were limitations in our study. The sample was limited to US trauma centers and injured children requiring admission, representing a higher acuity patient population. These findings are not generalizable to EDs at nontrauma hospitals or to children with noninjury conditions. There was a possibility of unmeasured confounding related to selection of the initial ED. However, we would expect such confounding to bias the association between high ED readiness and mortality toward the null. In addition, ED nurse managers self-reported ED pediatric readiness, without independent verification. If readiness scores were inflated or otherwise inaccurate, we would not expect an association with mortality, particularly after accounting for other hospital-level factors known to be associated with mortality. It was not possible to evaluate the relative contribution of each readiness domain because the number of questions and weighting scheme differed for each domain. Because different aspects of ED readiness may be interrelated,25 it is possible that the bundled program is most important for improving outcomes.

In addition, ED pediatric readiness was measured in 2013. The readiness of individual EDs may have changed over time. Although our analysis stratified by year did not suggest such changes, updated measurement of ED readiness will be important to quantify potential changes to individual EDs over time and whether such changes have resulted in improved outcomes. The next national assessment of ED pediatric readiness is planned for 2021.

Conclusions

In this cohort study, high ED pediatric readiness was associated with improved survival in US trauma centers, but not fewer in-hospital complications There was preventable mortality from care in lower-readiness EDs. These findings support efforts to increase the levels of high-quality initial ED care for injured children.

eFigure. Schematic of Cohort Creation

eTable 1. Procedures and Diagnoses Among Injured Children Defining Need for “Early Critical Resources” Within 24 Hours of Emergency Department Presentation (n = 32 671)

eTable 2. Percent Missingness of Variables (n = 372 004)

eTable 3. Hospital Characteristics by Quartile of Emergency Department (ED) Pediatric Readiness Among 832 Trauma Center EDs

eTable 4. Estimated Annual Number of Lives Saved Among Injured Children by Shifting Their Care From Lower-Readiness Emergency Departments (EDs) to High-Readiness EDs

eTable 5. Stratified Analysis by Transfer Status for the Association Between ED Pediatric Readiness, In-Hospital Mortality, and In-Hospital Complications

eTable 6. Stratified Analysis by Age Group for the Association Between ED Pediatric Readiness, In-Hospital Mortality, and In-Hospital Complications.

eTable 7. Stratified Analysis by Calendar Year for the Association Between ED Pediatric Readiness, In-Hospital Mortality, and In-Hospital Complications

eTable 8. Sensitivity Analyses of Emergency Department Pediatric Readiness and In-Hospital Mortality, With the Sequential Addition of Hospital-Level Variables and Year in the Model (n = 372 004)

Nonauthor Collaborators. The Pediatric Readiness Study Group

References

- 1.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control CNVSS, National Center for Health Statistics . 10 Leading causes of death by age group, United States—2012. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control CNVSS, National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borse NNRR, Dellinger AM, Sleet DA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Years of potential life lost from unintentional injuries among persons aged 0-19 years—United States, 2000-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(41):830-833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDermott KW, Stocks C, Freeman WJ. Overview of Pediatric Emergency Department Visits, 2015. HCUP Statistical Brief #242. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; August 2018. [PubMed]

- 4.Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System . Emergency Care for Children: Growing Pains. National Academy Press; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The National Pediatric Readiness Project , Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC) National Resource Center. Accessed February 19, 2021. http://www.pediatricreadiness.org/

- 6.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine; American College of Emergency Physicians Pediatric Committee; Emergency Nurses Association Pediatric Committee . Joint policy statement—guidelines for care of children in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(4):543-552. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pracht EE, Tepas JJ III, Langland-Orban B, Simpson L, Pieper P, Flint LM. Do pediatric patients with trauma in Florida have reduced mortality rates when treated in designated trauma centers? J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(1):212-221. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.09.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper A, Barlow B, DiScala C, String D, Ray K, Mottley L. Efficacy of pediatric trauma care: results of a population-based study. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28(3):299-303. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(93)90221-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hulka F, Mullins RJ, Mann NC, et al. Influence of a statewide trauma system on pediatric hospitalization and outcome. J Trauma. 1997;42(3):514-519. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199703000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang NE, Saynina O, Vogel LD, Newgard CD, Bhattacharya J, Phibbs CS. The effect of trauma center care on pediatric injury mortality in California, 1999 to 2011. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(4):704-716. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31829a0a65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sathya C, Alali AS, Wales PW, et al. Mortality among injured children treated at different trauma center types. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(9):874-881. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webman RB, Carter EA, Mittal S, et al. Association between trauma center type and mortality among injured adolescent patients. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(8):780-786. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Remick K, Gaines B, Ely M, Richards R, Fendya D, Edgerton EA. Pediatric emergency department readiness among US trauma hospitals. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86(5):803-809. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ames SG, Davis BS, Marin JR, et al. Emergency department pediatric readiness and mortality in critically ill children. Pediatrics. 2019;144(3):e20190568. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344-349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient. 6th. Ed. American College of Surgeons; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American College of Surgeons National Trauma Data Bank National Trauma Data Standard : Data Dictionary 2016 admissions. Committee on Trauma, American College of Surgeons; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Trauma Data Standard Data Dictionary , 2020 Admissions. American College of Surgeons; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaro MA. Probabilistic linkage of large public health data files. Stat Med. 1995;14(5-7):491-498. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon W Jr, Long WB. The Injury Severity Score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974;14(3):187-196. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197403000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Abbreviated Injury Scale, 2005 Revision, Update 2008. Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Lepper RL, Atzinger EM, Copes WS, Prall RH. An anatomic index of injury severity. J Trauma. 1980;20(3):197-202. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198003000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lerner EB, Drendel AL, Falcone RA Jr, et al. A consensus-based criterion standard definition for pediatric patients who needed the highest-level trauma team activation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(3):634-638. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gausche-Hill M, Ely M, Schmuhl P, et al. A national assessment of pediatric readiness of emergency departments. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(6):527-534. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Remick K, Kaji AH, Olson L, et al. Pediatric readiness and facility verification. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67(3):320-328.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.07.500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM . 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp

- 27.American Hospital Association , AHA annual survey database. Accessed November 13, 2020. https://www.ahadata.com/aha-annual-survey-database

- 28.Newgard CD, Fildes JJ, Wu L, et al. Methodology and analytic rationale for the American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(1):147-157. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Advanced Trauma Life Support. 9 ed.American College of Surgeons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Royston P, Ambler G, Sauerbrei W. The use of fractional polynomials to model continuous risk variables in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(5):964-974. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.5.964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Royston P AD. Regression using fractional polynomials of continuous covariates: parsimonious parametric modelling. Appl Statist. 1994;43(3):429-467. doi: 10.2307/2986270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinheiro JC CE. Efficient Laplacian and adaptive gaussian quadrature algorithms for multilevel generalized linear mixed models. J Computational Graphical Stat. 2006;15(1):55-81. doi: 10.1198/106186006X96962 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Little RJA, Rubins DB. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1987. doi: 10.1002/9780470316696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newgard C, Malveau S, Staudenmayer K, et al. ; WESTRN investigators . Evaluating the use of existing data sources, probabilistic linkage, and multiple imputation to build population-based injury databases across phases of trauma care. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(4):469-480. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01324.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newgard CD. The validity of using multiple imputation for missing out-of-hospital data in a state trauma registry. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(3):314-324. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newgard CD, Haukoos JS. Advanced statistics: missing data in clinical research—part 2: multiple imputation. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(7):669-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newgard CD, Malveau S, Zive D, Lupton J, Lin A. Building a longitudinal cohort from 9-1-1 to 1-year using existing data sources, probabilistic linkage, and multiple imputation: a validation study. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25(11):1268-1283. doi: 10.1111/acem.13512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377-399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raghunathan T L, Van Hoewyk J, Solenberger P.. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Survey Methodology 2001;27:85-95. [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16(3):219-242. doi: 10.1177/0962280206074463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sasser SM, Hunt RC, Sullivent EE, et al. ; National Expert Panel on Field Triage, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Guidelines for field triage of injured patients. Recommendations of the National Expert Panel on Field Triage. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58(RR-1):1-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Schematic of Cohort Creation

eTable 1. Procedures and Diagnoses Among Injured Children Defining Need for “Early Critical Resources” Within 24 Hours of Emergency Department Presentation (n = 32 671)

eTable 2. Percent Missingness of Variables (n = 372 004)

eTable 3. Hospital Characteristics by Quartile of Emergency Department (ED) Pediatric Readiness Among 832 Trauma Center EDs

eTable 4. Estimated Annual Number of Lives Saved Among Injured Children by Shifting Their Care From Lower-Readiness Emergency Departments (EDs) to High-Readiness EDs

eTable 5. Stratified Analysis by Transfer Status for the Association Between ED Pediatric Readiness, In-Hospital Mortality, and In-Hospital Complications

eTable 6. Stratified Analysis by Age Group for the Association Between ED Pediatric Readiness, In-Hospital Mortality, and In-Hospital Complications.

eTable 7. Stratified Analysis by Calendar Year for the Association Between ED Pediatric Readiness, In-Hospital Mortality, and In-Hospital Complications

eTable 8. Sensitivity Analyses of Emergency Department Pediatric Readiness and In-Hospital Mortality, With the Sequential Addition of Hospital-Level Variables and Year in the Model (n = 372 004)

Nonauthor Collaborators. The Pediatric Readiness Study Group