Abstract

The study of the disorders of ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation may unravel the molecular basis of human diseases, such as cancer (prostate cancer, lung cancer and liver cancer, etc.) and nervous system disease (Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease and Huntington's disease, etc.) and help in the design of new therapeutic methods. Leucine zipper-like transcription regulator 1 (LZTR1) is an important substrate recognition subunit of cullin-RING E3 ligase that plays an important role in the regulation of cellular functions. Mutations in LZTR1 and dysregulation of associated downstream signaling pathways contribute to the pathogenesis of Noonan syndrome (NS), glioblastoma and chronic myeloid leukemia. Understanding the molecular mechanism of the normal function of LZTR1 is thus critical for its eventual therapeutic targeting. In the present review, the structure and function of LZTR1 are described. Moreover, recent advances in the current knowledge of the functions of LZTR1 in NS, glioblastoma (GBM), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and schwannomatosis and the influence of LZTR1 mutations are also discussed, providing insight into how LZTR1 may be targeted for therapeutic purposes.

Keywords: Noonan syndrome, glioblastoma, LZTR1, CUL3, ubiquitin ligase, ubiquitination, RAS/MAPK signaling pathway

1. Introduction

Ubiquitylation is a key post-translational modification that plays a significant role in the stability of the intracellular environment, cell proliferation and differentiation, as well as various other cellular functions (1). An imbalance in ubiquitination-mediated protein degradation can represent the molecular basis of certain human diseases, such as cancers (prostate cancer, lung cancer and liver cancer) and nervous system diseases (Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease and Huntington's disease) (1). Ubiquitin is activated in an ATP-dependent reaction catalyzed by the ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 (2,3). Subsequently, under the action of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2, activated ubiquitin is transferred to a specific substrate along with E3 ubiquitin ligase (1). Substrate recognition for ubiquitin ligation is determined by E3 ubiquitin ligase (2,3), thus E3 ubiquitin ligase is specific compared with E1 and E2 enzymes and constitutes an important topic in medical research. One of the best known E3 ligase family is cullin (CUL)-RING E3 ubiquitin ligase, which consists of a molecular scaffold connecting a substrate-specific adaptor protein to a catalytic component comprising a RING finger domain and an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (4–8). The human genome contains eight CUL family members, namely, CUL1, −2, −3, −4A, −4B, −5, −7 and −9, all of which have an evolutionarily conserved CUL homology domain at the C-terminus, which promotes the interaction of CUL with RING box protein (RBX)1 or RBX2 (9–18). E3 adaptors of CUL3, such as speckle-type protein (SPOP) (19–29), Kelch repeat and BTB domain-containing protein 8 (KBTBD8) (30–32) and Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) (33–35), are composed of a similar structure called broad-complex, tramtrack and bric-a-brac (BTB) domain (15–18), which combines the substrate receptor and adaptor functions into the CUL3-RBX1 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (36,37).

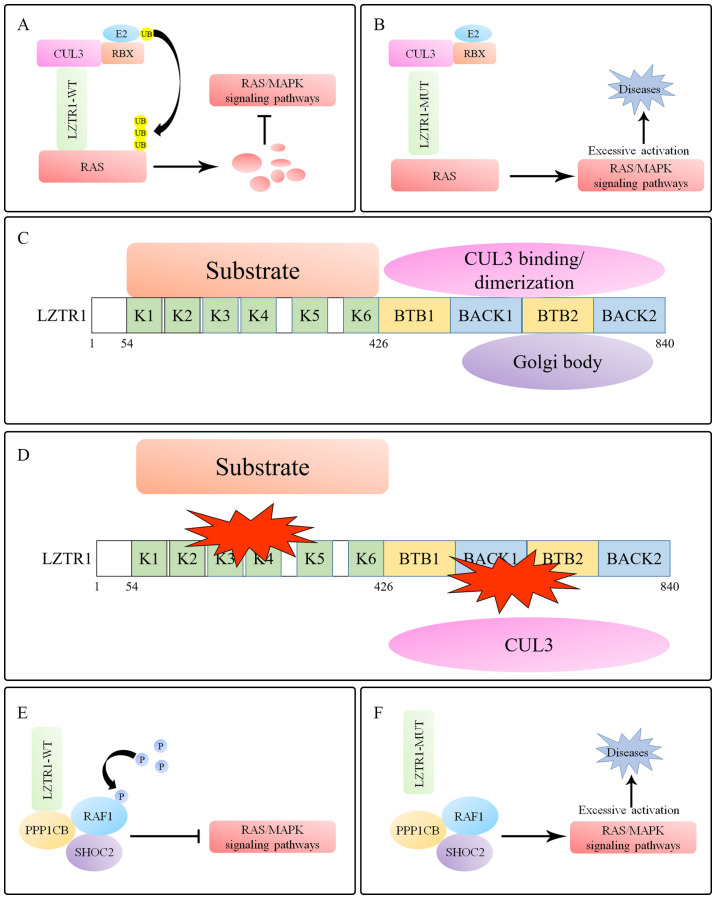

Recently, increased attention has been paid to leucine zipper-like transcription regulator 1 (LZTR1), due to its far-reaching implications in physiological and pathological conditions of cells and human diseases, such as Noonan syndrome (NS), glioblastoma (GBM), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and schwannomatosis (38,39). LZTR1, also a member of the BTB-Kelch superfamily proteins, is the substrate-specific adaptor for CUL3 ubiquitin ligase complex (38–40). Given its weak homology to known members of the basic leucine zipper-like family, LZTR1 was initially identified as a transcriptional regulator (40). Proteins of the BTB-Kelch superfamily often interact with actin filaments and play important roles in fundamental cell functions, such as transcriptional regulation and protein ubiquitination (41–45). However, unlike other BTB-Kelch proteins, LZTR1 shows no interaction with actin but is localized on the Golgi complex (40), suggesting a unique function and status. Mutations in the LZTR1 gene occur in ≤8% of patients with NS (46,47), 4.4% of those with GBM (39,48) and 24.4% of those with schwannomatosis (Table I) (49–51). The occurrence of these diseases is related to abnormal function of RAS proteins, demonstrating a close relationship between LZTR1 and proteins of the RAS superfamily (38,52–54). Notably, almost all members of the RAS superfamily, including KRAS, NRAS, RAS-like without CAAX1 (RIT1) and RAF1, are substrates of LZTR1 (38,55,56). LZTR1 regulates the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway by inducing the polyubiquitination and degradation of RAS-superfamily proteins (KRAS, MRAS, NRAS and RAF1) (Fig. 1A) (57), whereas disease-associated LZTR1 mutations lose this capability, leading to excessive activation of RAS/MAPK signaling (Fig. 1B). The effect of LZTR1 on RAS/MAPK signaling is specific as demonstrated by the failure of the other two prominent CUL3 adaptors (KEAP1 and SPOP) in the process of RAS ubiquitination (38).

Table I.

Leucine zipper-like transcription regulator 1 mutations.

| Disease | Mutation frequency in disease (%) | Mutations in Kelch domains | Mutations in BTB-BACK domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noonan syndrome | 8.0 | Arg97Leu, His121Asp, Tyr136Cys, Tyr136His, Asn145Ile, Arg170Trp, Ile205Thr, Arg210*, Glu217Ala, Ser244Cys, Ser247Asn, Gly248Arg, Arg284Cys, His287Tyr | Trp437*, Ala461Asp, Ile462Thr, Trp469*, Glu563Gln, Val579Met, Arg688Gly(Cys), Arg688Cys, Asp531Asn, Arg697Glu, Tyr749Cys, Arg755Gln, Ile821Thr |

| Glioblastoma | 4.4 | Trp105Arg, Asp139Ala, Asn143Thr, Gly195Ser, Arg198Gly, Gly248Arg, Arg284Ser, Thr288Ile, G404Glu | Arg810Trp |

| Schwannomatosis | 24.4 | His71Arg, Pro115Leu, Ser122Leu, Arg170Gln, Leu187Leu, Met202Arg, Arg284Cys, Gly285Arg, Met400Arg, Gly404Arg | Val456Gly, Arg466Gln(Trp), Pro520Leu, Met665Lys, Arg688His(Cys), Leu812Pro, Ser813Leu |

BACK, broad-complex, tramtrack, and bric-a-brac and C-terminal Kelch.

Figure 1.

LZTR1 regulates RAS/MAPK signaling. (A) LZTR1 induces polyubiquitination and degradation of RAS proteins to inhibit the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway. (B) Mutated LZTR1 loses the ability to regulate RAS superfamily proteins, leading to excessive activation of the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway. (C) A total of six N-terminal Kelch motifs and two BACK domains are located at the C-terminus within LZTR1. The Kelch domains selectively recruit substrates, whereas the BACK domains are predicted to mediate dimerization and CUL3 binding. (D) Mutations in Kelch domains decrease binding to substrates. The mutations located in the BTB/BACK domains of LZTR1 prevent the binding of LZTR1 to CUL3. All of these mutations prevent the formation of the substrate-LZTR1-CUL3 complex. (E) LZTR1 mediates RAF phosphorylation by binding to the RAF1/PPP1CB/SHOC2 complex to inhibit the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway. (F) Mutations in LZTR1 lead to loss of RAF1 regulation, leading to excessive activation of the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway, eventually resulting in Noonan syndrome. LZTR1, leucine zipper-like transcription regulator 1; BTB, broad-complex, tramtrack, and bric-a-brac; BACK, BTB and C-terminal Kelch; CUL, cullin; PPP1CB, protein phosphatase 1 catalytic subunit β; RBX, RING box protein; WT wild-type; Mut, mutant; UB, ubiquitin; P, pyrophosphate.

2. Structure and mutations of the LZTR1 protein

The Kelch domains of the BTB-Kelch superfamily proteins are located at the C-terminus of the BTB domains, and the conserved BACK domains are present in almost all members (17). Different from the general BTB-Kelch-superfamily proteins, the primary structure of LZTR1 includes six Kelch motifs at the N-terminus and two C-terminal BTB-BACK domains (40). The Kelch domains selectively recruit substrates, whereas the BACK domains are considered to mediate dimerization and the binding to CUL3 (58). Furthermore, the second BTB domain (from N to C) mediates the interaction between the Golgi complex and LZTR1, suggesting that LZTR1 may be a novel Golgi matrix-associated protein (Fig. 1C) (40).

The majority of NS- and GBM-related LZTR1 mutations are clustered in the Kelch domains (Table I), and these mutations are defective in LZTR1-mediated substrate binding, thus preventing the formation of substrate-LZTR1-CUL3 complexes and their efficient ubiquitination and degradation, which results in excessive activation of RAS/MAPK signaling in NS or GBM (39,55,58). Furthermore, except for the Leu812Pro mutation, mutations in the LZTR1 BACK domains exhibit reduced interaction with CUL3 and although LZTR1-L812P retains the ability to bind to CUL3, it fails to dimerize LZTR1 (38). The endogenous and exogenous expression of wild-type LZTR1 displays punctate endomembrane immunostaining, but diffuse and uniform cytoplasmic staining when LZTR1 mutations occur in the BACK domains, including in the Leu812Pro mutant (58). Interestingly, unlike NS- and GBM-associated LZTR1 mutations, which are concentrated in the Kelch domains, schwannomatosis-associated LZTR1 mutations are more evenly distributed across all domains, and these mutations may result in failure to bind with CUL3 (38,39,46–48). In summary, disease-related LZTR1 mutations are defective in mediating substrate ubiquitination by disrupting the formation of substrate-LZTR1-CUL3 complexes (Fig. 1D; Table I).

3. LZTR1 in Noonan syndrome

RASopathies are defined as a class of inherited diseases with germline mutations in genes encoding components of the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway (58). RAS-superfamily proteins are a class of evolutionarily conserved proteins with high affinity for GDP and GTP (52,59,60). RAS proteins, similar to molecular switches, are activated when interacting with GTP and serve as positive regulators in the physiological activities of cells, such as proliferation and cell division (59,61–64). RASopathy-associated RAS mutations located in the secondary locus (mutations at these loci only slightly affect the physiological function of RAS superfamily proteins) weakly affect GTPase activity without causing embryonic-lethal death (53,54,65–69). NS, one of the most common and typical RASopathies, is caused by germline gain-of-function pathogenic RAS variants affecting the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway (38).

The pathogenesis of NS depends on abnormal protein degradation of RAS-superfamily proteins, including KRAS, NRAS, RIT1 and RAF1 (38,55,56,58). LZTR1 has also been added to the list of genes causing NS, and mutations in LZTR1 are present in ≤8% of patients with NS (46,70). NS patients harboring LZTR1 mutations present typical NS facial features, a webbed neck, cardiovascular defects and coagulation dysfunction (71).

Previous studies have suggested that almost all NS-related mutations in LZTR1 are dominant mutations that occur mainly in the Kelch domains (38,58,70). These mutations neither alter CUL3 binding nor affect subcellular localization and stability of LZTR1 (72), although they may impair its ability to specifically recognize substrates, such as KRAS, NRAS and HRAS, ultimately contributing to the excessive activation of RAS/MAPK signaling (58,72). However, a recent study reported biallelic loss-of-function LZTR1 mutations in three patients NS (Table I), suggesting recessive inheritance of some NS cases (73). Thus, considering the different effects of LZTR1 mutations, determining the association between LZTR1 and the autosomal-dominant and autosomal-recessive forms of NS may prove useful.

RAF1 is the downstream substrate of most classical RAS proteins, mediating the activation of the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway. Protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), which interacts with the leucine-rich repeat protein SHOC2 to form a complex encoded by an NS-causing gene, dephosphorylates RAF1 to activate ERK (74,75). A recent study on a case report identified eight LZTR1 variants, including a de novo variant, in seven probands who were susceptible to NS and one known de novo PP1 catalytic subunit β (PPP1CB) variant in a patient with NS, indicating that LZTR1 and PPP1CB may be closely related to the pathogenesis of NS (56). Moreover, co-immunoprecipitation demonstrated that endogenous LZTR1 interacted with the RAF1-PPP1CB complex and that RAF1 phosphorylation levels (Ser259), but not ubiquitination, suggesting that LZTR1 may be involved in additional pathways that mediate the phosphorylation of RAF1 to regulate its activity (Fig. 1E and F) (56).

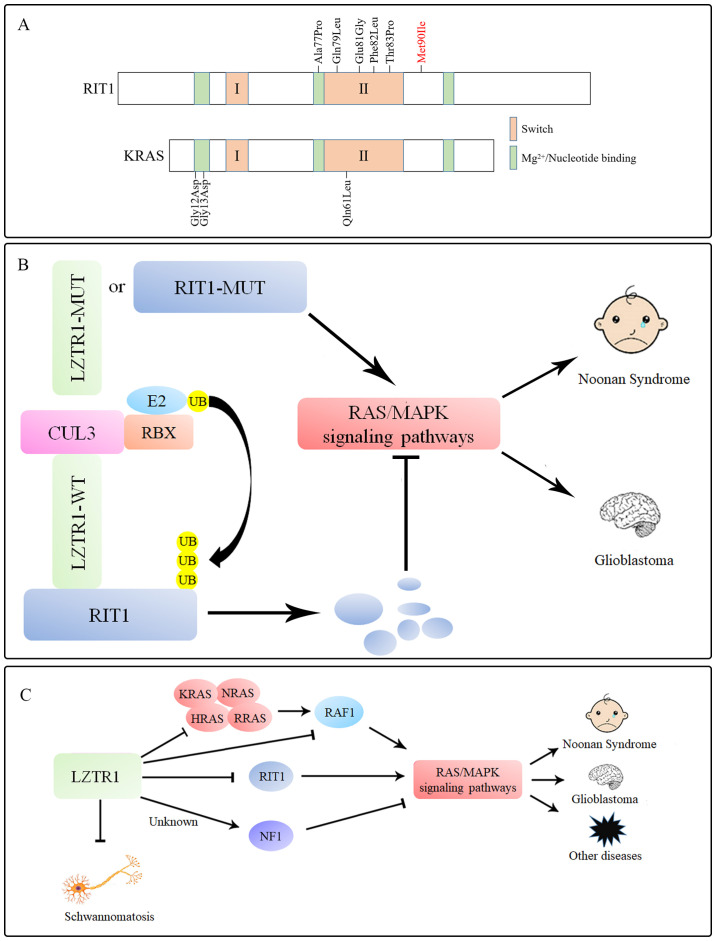

RIT1 also belongs to the RAS superfamily and is highly similar to other members (K-, H-, R- and NRAS), regulating the physiological activity of cells (76–79). Germline mutations in RIT1 account for 5–9% of mutations in patients with NS (54,80). The NS-associated mutation Met90Ile in RIT1 (Fig. 2A), which is located in an atypical site around the switch II region, contributes to the symptoms of typical NS, suggesting a strong association between RIT1 and NS (55). LZTR1 acts a negative regulator in the control of RIT1 activity by inducing RIT1 ubiquitination via K48 (Lys48)-linked ubiquitination and degradation (Fig. 2B). The exogenous overexpression of LZTR1 in 293T cells leads to a reduction in RIT1 protein levels, which is reversed by the proteasomal inhibitor bortezomib and by the CUL3 inhibitor MLN4924, but not by the lysosomal inhibitor bafilomycin (81,82).

Figure 2.

LZTR1 inhibits the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway by regulating RIT1 in NS and GBM. (A) NS-related RIT1 mutations do not occur in codons analogous to the classic Gly12, Gly13, and Gln61 alleles compared with other RAS-superfamily proteins, although they are clustered around the switch II region. (B) LZTR1 induces polyubiquitination and degradation of RIT1 to inhibit the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway. By contrast, mutations in LZTR1 or RIT1 prevent the formation of the substrate-LZTR1-CUL3 complex, resulting in insufficient degradation of RIT1, abnormal activation of RAS/MAPK signaling, leading to the occurrence of NS or GBM. (C) LZTR1 regulates RAS/MAPK signaling, and mutations in LZTR1 or RAS-superfamily proteins lead to excessive activation of the RAS/MAPK signaling pathways, eventually resulting in NS and GBM. LZTR1 inhibits the occurrence of schwannomatosis, although the specific mechanism remains unclear. The relationship between NF1, which serves as a negative regulator of the RAS signaling pathway, and LZTR1 remains to be studied. LZTR1, leucine zipper-like transcription regulator 1; RIT1, RAS-like without CAAX1; CUL, cullin; NS, Noonan syndrome; GBM, glioblastoma; NF1, neurofibromin 1; RBX, RING box protein; WT, wild-type; Mut, mutant; UB, ubiquitin; P, pyrophosphate.

Notably, almost all NS-associated RIT1 mutants are defective in their interaction with endogenous LZTR1 compared with the wild-type RIT1, thus preventing the proteolysis and ubiquitination of RIT1 mutants (39,54,55,77). Similarly, a group of NS-associated LZTR1 mutations are associated with impaired RIT1 degradation, thus revealing the close relationship between LZTR1 and RIT1 (49,55). Under physiological conditions, RIT1 is ubiquitinated by the LZTR-CUL3 complex, then degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS). Moreover, under pathological conditions, RIT1 escapes from UPS-mediated degradation, thus leading to significant enhancement of MAPK signaling in NS (Fig. 2B). This suggests that LZTR1 serves a negative role in MAPK signaling, whereas mutations in LZTR1 or members of the RAS superfamily affect MAPK signaling and contribute to NS.

4. LZTR1 in glioblastoma (GBM)

RAS is considered the most closely related oncoprotein to human cancer (such as pancreatic, lung and colon cancer, as well as hematological malignancies) and is commonly activated in tumor cells (47,59,64,83). Given their vital effects on GTPase activity, cancer-related RAS mutations are often lethal in embryos, avoiding the transmission of germline (60,84–86).

Brain cancer is one of the most common tumors in adults; among the different types of brain cancer, GBM is the most common (48%) and deadliest (median overall survival of 12–14 months) given its high tumor heterogeneity and poor survival (87–93). Numerous genetic mutations, including those in the LZTR1 gene, have been identified in GBM using whole-exome sequencing. LZTR1 mutations in GBM include 4.4% non-synonymous mutations and 22.4% focal deletions in the coding sequence (94). RIT1 is regarded as an important pathogenic factor of GBM, which participates in the activation of the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway and plays crucial roles in various physiological processes, including cell survival, proliferation and differentiation (95–99). Moreover, LZTR1 can interact with endogenous RIT1, which is considered a tumor promoter in GBM (39,94). Frattini et al (94) demonstrated that 9 out of 10 LZTR1 mutations occur in the Kelch domains and greatly impair the RIT1-LZTR1 interaction. Thus, LZTR1 suppresses the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway by degrading RIT1 to inhibit proliferation and migration of GBM cells; however, GBM-associated LZTR1 mutations impair this function (Fig. 2B) (39,77,94). Moreover, LZTR1 decreases tumor size by inducing glioma spheres, enhancing glioma cell adhesion and reducing cell cycle progression-related proteins (such as cyclin A, PLK1 and p107), whereas mutations or deletions in LZTR1 impair glioma sphere formation and promote the self-renewal ability of GBM cells (39,77). These findings suggest that GBM-associated LZTR1 mutations in human GBM drive self-renewal and the growth of glioma spheres (39,55,77). Moreover, LZTR1 simultaneously found in GBM with mutations and deletions confirms the two-hit hypothesis of cancer (the two alleles of tumor suppressor genes are required to be mutated into ‘loss of function’ in one cell (100). When a cell in a person is heterozygous for a germline mutation (‘one hit’), it is required to undergo a second, somatic event (‘second hit’) that inactivates the other allele to initiate cancers (100), further indicating that LZTR1 acts as a tumor suppressor in GBM (89–91,94). Given the significance of LZTR1-RIT1 signaling in GBM, LZTR1 and RIT1 may represent promising therapeutic targets for GBM.

5. LZTR1 in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)

The activation of key cellular pathways, including the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway, affects the survival and proliferation of BCR-ABL+ CML cells (101–103). The occurrence of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) resistance is also associated with dysregulation of RAS/MAPK signaling (38). In recent studies, the inactivation of endogenous or exogenous LZTR1 increased the phosphorylation of MAPK kinase 1 and −2, as well as ERK1 and −2 in CML cells (indicating enhanced RAS/MAPK signaling activation) and promoted the resistance of these cells to TKIs (104,105). This phenotype may depend on the failed formation of the CUL3 ligase complex, as similar phenotypic changes were also observed when CUL3 was genetically silenced (38). Thus, there is limited knowledge of the link between LZTR1 inactivation and TKI resistance, and further study of this molecular mechanism may help alleviate TKI resistance in CML.

6. LZTR1 in schwannomatosis

Schwannomatosis is a hereditary disease characterized by schwannomas in the spinal and peripheral nerves and predisposition to benign tumors throughout the nervous system (106–108). Local or diffuse chronic pain is the most common symptom reported by patients with schwannomatosis (49). Germline mutations in the LZTR1 gene occur in 41 out of 168 sporadic patients with schwannomatosis (24.4%), highlighting the complex heterogeneity of schwannomatosis (106,108). Interestingly, schwannomatosis-associated LZTR1 mutations are uniformly located in almost every domain (Table I). Thus, in contrast with the mutations in NS and GBM, there is no positional preference for LZTR1 mutations in schwannomatosis (50). Notably, the occurrence of schwannomatosis-associated LZTR1 mutations at the same genetic locus as NS-associated ones and the coexistence of NS and schwannomatosis in some patients have also been reported in previous studies (108,109). According to the two-hit hypothesis, biallelic loss of a tumor suppressor gene can lead to tumorigenesis; hence, according to the two-hit hypothesis, the NS patients carrying LZTR1 germline mutations are more likely to have schwannomatosis (50,109,110). However, the pathogenesis of this disease and the signaling pathways involving LZTR1 have rarely been rarely studied.

SWI/SNF-related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin subfamily B member 1 (SMARCB1) was identified as the first predisposing gene for schwannomatosis (111). Both SMARCB1 and LZTR1 are located at the 22q centromere, and a previous study identified germline variants of LZTR1 in 24 patients with SMARCB1-negative schwannomatosis from 22 unrelated families (112). Notably, recent studies reported the occurrence of GBM in patients with schwannomatosis and germline LZTR1 mutations or SMARCB1 mutations (48,113,114). Given the lack of evidence of protein interaction between SMARCB1 and LZTR1 or their participation in specific signaling pathways, further research on LZTR1 and SMARCB1 may clarify the molecular basis of schwannomatosis and GBM.

7. Conclusions and prospects

LZTR1 acts as a negative factor that suppresses RAS function and MAPK signaling; mutations in this protein may dysregulate RAS ubiquitination and lead to impaired protein degradation of RAS superfamily proteins, leading to NS, GBM, schwannomatosis and CML cell resistance to TKIs (Fig. 2C) (38,39,58). Notably, NS- and GBM-related LZTR1 mutations are concentrated in the Kelch domains, whereas schwannomatosis-associated LZTR1 mutations are uniformly located in almost every domain (38,50.58.106,107,113-115). The distribution of these mutations is associated with the severity of these diseases. Indeed, LZTR1 mutations located in Kelch domains directly affect the substrate binding of the LZTR1 (40,58), which has the greatest effect on the degradation level of the substrate, thus leading to more serious diseases, such NS and GBM. However, schwannomatosis-associated LZTR1 mutations occur in sites that only slightly affect the function of LZTR1 and to some extent, substrate-LZTR1-CUL3 complexes still work. This hypothesis may be tested by studying LZTR1 mutations in patients with concurrent GBM and schwannomatosis.

For several genetic diseases, such as NS, early detection may be more important than treatment. LZTR1 has also been added to the list of genes causing NS and is present in ≤8% of NS patients (46,70). Thus, prenatal screening for LZTR1 mutations and prophylactic use of RAS inhibitors may be a possible way to avoid the occurrence of NS after birth. Moreover, for patients with LZTR1 mutations in GBM and other cancer types, RAS pathway inhibitors may be a good choice for treatment. Thus, comprehensive understanding of other mechanisms of RAS activation may benefit patients carrying LZTR1 mutations and offer new therapeutic strategies (38,58).

LZTR1 is also closely related to the central nervous system. LZTR1 interacts with CUL3 and neurofibromin 1 (NF1) to regulate night-time sleep by increasing GABA receptor signaling and has been associated with RAS-related neurological diseases created by Nf1 deficiency (116). NF1 is a negative growth factor of the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway, which, together with LZTR1, may inhibit RAS/MAPK signaling pathways (117). However, the molecular mechanism of the interaction between LZTR1 and NF1 remains unknown. The functions of LZTR1 in the nervous system are not restricted to those already described and may be closely related to neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease (117). Notably, the frequency of LZTR1 mutations in schwannomatosis are as high as 25% (49), yet the specific molecular mechanism of the disease has not been explored. Characterizing LZTR1-associated functional changes in schwannomatosis will provide additional insights into the disease and design of new therapeutic strategies, thus benefitting patients carrying LZTR1 mutations.

LZTR1 has previously been considered as a ubiquitin-ligase enzyme, rather than phosphokinase; however, it also regulates the phosphorylation but not the ubiquitination of RAF1 (56). LZTR1 could mediate the phosphorylation of RAF1 by inducing ubiquitination of PPP1CB in complexes, and LZTR1 itself may also phosphorylate substrates. However, such phenomenon has not been confirmed. Phosphorylation and ubiquitination are common post-translational protein modifications that play crucial roles in the functions of substrates. Thus, the molecular basis of determining whether LZTR1 is capable of phosphorylating substrates directly is worth exploring in the future.

Compared with the current knowledge of SPOP, another E3 adaptor of CUL3 (2,15,19–29), our understanding of LZTR1 substrates is still limited. The interaction between proteins depends on their specific structure, and a class of proteins that interacts with the same protein often share similar domains, such as SPOP-binding consensus motifs (Φ-π-S-S/T-S/T, where Φ: nonpolar residues; π: polar residue; S: Ser and T:Thr) (22). Searching for regions on the substrates that bind to LZTR1 from the existing known substrates (RAS superfamily proteins) will accelerate LZTR1 research, together with structural studies to identify interacting domains in LZTR1-mediated substrates (38,39,55–58,116). Currently, the known substrates of LZTR1 are restricted to the RAS superfamily (Table II). Therefore, additional potential substrates for LZTR1 should be further studied.

Table II.

Leucine zipper-like transcription regulator 1 substrates.

| Substrate name | Substrate function |

|---|---|

| KRAS | Cell division, angiogenesis |

| NRAS | Cell division, angiogenesis |

| HRAS | Cell division, angiogenesis |

| RRAS | Vascular homeostasis and regeneration, angiogenesis, cell adhesion |

| RIT1 | Neuronal development and regeneration |

| RAF1/PPP1CB/SHOC2 | Cell cycle, cell division, glycometabolism, angiogenesis |

| NF1 | Cell division |

RIT1, RAS-like without CAAX1; PPP1CB, protein phosphatase 1 catalytic subunit β; NF1, neurofibromin 1.

Additionally, studying alternative mechanisms of RAS regulation will also assist with the development of new treatments for RAS-driven diseases. Notably, although KRAS is the most frequently mutated member of the RAS family and is closely related to human malignant tumors, it has long been considered to be untargetable (23,53,118–125). LZTR1 is the most specific and potent regulator of KRAS (38). Thus, further research on LZTR1 may help in the successful targeting of KRAS in the future.

Notably, LZTR1 is a novel Golgi matrix-associated protein (40), and it may be closely related to the function of Golgi body. The Golgi body is responsible for the processing, sorting and transportation of proteins and plays an important role in tumorigenesis, progression and invasion (126). The functional changes in the Golgi body caused by LZTR1 variants should also be further studied.

In conclusion, LZTR1 might become an important focus of biomedical research. Further studies are required for improved understanding of the biological function of LZTR1 and its role in the occurrence of diseases, as well as the development of disease treatments, such as rational design of LZTR1 promoters for patients harboring loss-of-function LZTR1 mutations.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Yuqi Wang (West Lake University, China) for the kind help and good advice provided.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by The Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (grant no. LY20C070001), The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31801165), The Natural Science Foundation of Ningbo (grant no. 2018A610213), The National Undergraduate Training Program for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (grant no. 202011646030), The Program of Xinmiao (Potential) Talents in Zhejiang Province (grant nos. 2019R405061, 2019R405011 and 2020R405039), The Student Research and Innovation Program of Ningbo University (grant nos. 2020SRIP1923, 2020SRIP1919, 2020SRIP1902 and 2020SRIP1901) and The K.C. Wong Magna Fund in Ningbo University.

Funding

This work was supported by The Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (grant no. LY20C070001), The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31801165), The Natural Science Foundation of Ningbo (grant no. 2018A610213), The National Undergraduate Training Program for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (grant no. 202011646030), The Program of Xinmiao (Potential) Talents in Zhejiang Province (grant nos. 2019R405061, 2019R405011 and 2020R405039), The Student Research and Innovation Program of Ningbo University (grant nos. 2020SRIP1923, 2020SRIP1919, 2020SRIP1902 and 2020SRIP1901) and The K.C. Wong Magna Fund in Ningbo University.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

XJ conceived the present study. HZ and XC drafted the manuscript. QL, JW and YZ made substantial contributions to the interpretation, drafting the study and revising it critically for important intellectual content. XJ, HZ and XC were major contributors in the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mani RS. The emerging role of speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP) in cancer development. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19:1498–1502. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zou T, Zhang J. Diverse and pivotal roles of neddylation in metabolism and immunity. FEBS J. Oct 6;:s2020. doi: 10.1111/febs.15584. doi: 10.1111/febs.15584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asmar AJ, Beck DB, Werner A. Control of craniofacial and brain development by Cullin3-RING ubiquitin ligases: Lessons from human disease genetics. Exp Cell Res. 2020;396:112300. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2020.112300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Achim W, Regina B, Nia T, Kaya DU, Michael R. Multisite dependency of an E3 ligase controls monoubiquitylation-dependent cell fate decisions. Elife. 2018;7:e35407. doi: 10.7554/eLife.35407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senft D, Qi J, Ronai ZA. Ubiquitin ligases in oncogenic transformation and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:69–88. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rape M. Ubiquitylation at the crossroads of development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19:59–70. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng N, Schulman BA, Song L, Miller JJ, Jeffrey PD, Wang P, Chu C, Koepp DM, Elledge SJ, Pagano M, et al. Structure of the Cul1-Rbx1-Skp1-F boxSkp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Nature. 2002;416:703–709. doi: 10.1038/416703a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enchev RI, Schulman BA, Peter M. Protein neddylation: Beyond cullin-RING ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:30–44. doi: 10.1038/nrm3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Liu P, Inuzuka H, Wei W. Roles of F-box proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:233–247. doi: 10.1038/nrc3700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teixeira LK, Reed SI. Ubiquitin ligases and cell cycle control. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:387–414. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060410-105307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipkowitz S, Weissman AM. RINGs of good and evil: RING finger ubiquitin ligases at the crossroads of tumour suppression and oncogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:629–643. doi: 10.1038/nrc3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornelius RJ, Ferdaus MZ, Nelson JW, McCormick JA. Cullin-Ring ubiquitin ligases in kidney health and disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2019;28:490–497. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen RH. Cullin 3 and its role in tumorigenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1217:187–210. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-1025-0_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J, McCormick JA, Sigmund CD. Cullin-3: Renal and vascular mechanisms regulating blood pressure. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2020;22:61. doi: 10.1007/s11906-020-01076-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang P, Song J, Ye D. CRL3s: The BTB-CUL3-RING E3 ubiquitin Ligases. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1217:211–223. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-1025-0_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornelius RJ, Yang CL, Ellison DH. Hypertension-causing cullin 3 mutations disrupt COP9 signalosome binding. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2020;318:F204–F208. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00497.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin X, Shi Q, Li Q, Zhou L, Wang J, Jiang L, Zhao X, Feng K, Lin T, Lin Z, et al. CRL3-SPOP ubiquitin ligase complex suppresses the growth of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by negatively regulating the MyD88/NF-κB signaling. Leukemia. 2020;34:1305–1314. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0661-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbieri CE, Baca SC, Lawrence MS, Demichelis F, Blattner M, Theurillat JP, White TA, Stojanov P, Van Allen E, Stransky N, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent SPOP, FOXA1 and MED12 mutations in prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44:685–689. doi: 10.1038/ng.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Gallo M, O'Hara AJ, Rudd ML, Urick ME, Hansen NF, O'Neil NJ, Price JC, Zhang S, England BM, Godwin AK, et al. NIH Intramural Sequencing Center (NISC) Comparative Sequencing Program Exome sequencing of serous endometrial tumors identifies recurrent somatic mutations in chromatin-remodeling and ubiquitin ligase complex genes. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1310–1315. doi: 10.1038/ng.2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin X, Wang J, Gao K, Zhang P, Yao L, Tang Y, Tang L, Ma J, Xiao J, Zhang E, et al. Dysregulation of INF2-mediated mitochondrial fission in SPOP-mutated prostate cancer. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei X, Fried J, Li Y, Hu L, Gao M, Zhang S, Xu B. Functional roles of Speckle-Type Poz (SPOP) protein in genomic stability. J Cancer. 2018;9:3257–3262. doi: 10.7150/jca.25930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuneo MJ, Mittag T. The ubiquitin ligase adaptor SPOP in cancer. FEBS J. 2019;286:3946–3958. doi: 10.1111/febs.15056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin X, Wang J, Li Q, Zhuang H, Yang J, Lin Z, Lin T, Lv Z, Shen L, Yan C, et al. SPOP targets oncogenic protein ZBTB3 for destruction to suppress endometrial cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:2797–2812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Z, Song Y, Ye M, Dai X, Zhu X, Wei W. The diverse roles of SPOP in prostate cancer and kidney cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2020;17:339–350. doi: 10.1038/s41585-020-0314-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song Y, Xu Y, Pan C, Yan L, Wang ZW, Zhu X. The emerging role of SPOP protein in tumorigenesis and cancer therapy. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:2. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark A, Burleson M. SPOP and cancer: A systematic review. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10:704–726. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maekawa M, Higashiyama S. The roles of SPOP in DNA damage response and DNA replication. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:7293. doi: 10.3390/ijms21197293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werner A, Iwasaki S, McGourty CA, Medina-Ruiz S, Teerikorpi N, Fedrigo I, Ingolia NT, Rape M. Cell-fate determination by ubiquitin-dependent regulation of translation. Nature. 2015;525:523–527. doi: 10.1038/nature14978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li YR, Peng RR, Gao WY, Liu P, Chen LJ, Zhang XL, Zhang NN, Wang Y, Du L, Zhu FY, et al. The ubiquitin ligase KBTBD8 regulates PKM1 levels via Erk1/2 and Aurora A to ensure oocyte quality. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11:1110–1128. doi: 10.18632/aging.101802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lührig S, Kolb S, Mellies N, Nolte J. The novel BTB-kelch protein, KBTBD8, is located in the Golgi apparatus and translocates to the spindle apparatus during mitosis. Cell Div. 2013;8:3. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-8-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang T, Sánchez-Rivera F, Soto-Feliciano Y, Yang Q, Song CQ, Bhuatkar A, Haynes CM, Hemann MT, Xue W. Targeting de novo purine synthesis pathway via ADSL depletion impairs liver cancer growth by perturbing mitochondrial function. Hepatology. 2020 Dec 17; doi: 10.1002/hep.31685. (Epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1002/hep.31685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madden S, Itzhaki L. Structural and mechanistic insights into the Keap1-Nrf2 system as a route to drug discovery. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom. 2020;1868:140405. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2020.140405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhamodharan U, Ponjayanthi B, Sireesh D, Bhakkiyalakshmi E, Ramkumar KM. Association of single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the KEAP1 gene with the risk of various human diseases and its functional impact using in silico analysis. Pharmacol Res. 2018;137:205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pintard L, Kurz T, Glaser S, Willis JH, Peter M, Bowerman B. Neddylation and deneddylation of CUL-3 is required to target MEI-1/Katanin for degradation at the meiosis-to-mitosis transition in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2003;13:911–921. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gray WM, Hellmann H, Dharmasiri S, Estelle M. Role of the Arabidopsis RING-H2 protein RBX1 in RUB modification and SCF function. Plant Cell. 2002;14:2137–2144. doi: 10.1105/tpc.003178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bigenzahn JW, Collu GM, Kartnig F, Pieraks M, Vladimer GI, Heinz LX, Sedlyarov V, Schischlik F, Fauster A, Rebsamen M. LZTR1 is a regulator of RAS ubiquitination and signaling. Science. 2018;362:1171–1177. doi: 10.1126/science.aap8210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Zhang J, Zhang P, Zhao Z, Huang Q, Yun D, Chen J, Chen H, Wang C, Lu D. LZTR1 inactivation promotes MAPK/ERK pathway activation in glioblastoma by stabilizing oncoprotein RIT1. bioRxiv. 2020 Mar 15; (Epub ahead of print) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nacak TG, Leptien K, Fellner D, Augustin HG, Kroll J. The BTB-kelch protein LZTR-1 is a novel Golgi protein that is degraded upon induction of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5065–5071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams J, Kelso R, Cooley L. The kelch repeat superfamily of proteins: Propellers of cell function. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:17–24. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(99)01673-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Z, Wasney GA, Picaud S, Filippakopoulos P, Vedadi M, D'Angiolella V, Bullock AN. Identification of a PGXPP degron motif in dishevelled and structural basis for its binding to the E3 ligase KLHL12. Open Biol. 2020;10:200041. doi: 10.1098/rsob.200041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heng LZ, Kennedy J, Smithson S, Newbury-Ecob R, Churchill A. New macular findings in individuals with biallelic KLHL7 gene mutation. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2019;4:e000234. doi: 10.1136/bmjophth-2018-000234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Narahara S, Sakai E, Kadowaki T, Yamaguchi Y, Narahara H, Okamoto K, Asahina I, Tsukuba T. KBTBD11, a novel BTB-Kelch protein, is a negative regulator of osteoclastogenesis through controlling Cullin3-mediated ubiquitination of NFATc1. Sci Rep. 2019;9:3523. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40240-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao C, Pallett MA, Croll TI, Smith GL, Graham SC. Molecular basis of cullin-3 (Cul3) ubiquitin ligase subversion by vaccinia virus protein A55. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:6416–6429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.006561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakaguma M, Jorge AA, Arnhold IJ. Noonan syndrome associated with growth hormone deficiency with biallelic LZTR1 variants. Genet Med: 2019;21:260. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacquinet A, Bonnard A, Capri Y, Martin D, Sadzot B, Bianchi E, Servais L, Sacré JP, Cavé H, Verloes A. Oligo-astrocytoma in LZTR1-related Noonan syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 2020;63:103617. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deiller C, Van-Gils J, Zordan C, Tinat J, Loiseau H, Fabre T, Delleci C, Cohen J, Vidaud M, Parfait B, et al. Coexistence of schwannomatosis and glioblastoma in two families. Eur J Med Genet. 2019;62:103680. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2019.103680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merker VL, Esparza S, Smith MJ, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, Plotkin SR. Clinical features of schwannomatosis: A retrospective analysis of 87 patients. Oncologist. 2012;17:1317–1322. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Farschtschi S, Mautner VF, Cooper DN. The molecular pathogenesis of schwannomatosis, a paradigm for the co-involvement of multiple tumour suppressor genes in tumorigenesis. Hum Genet. 2017;136:129–148. doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1753-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mansouri S, Suppiah S, Mamatjan Y, Paganini I, Liu JC, Karimi S, Patil V, Nassiri F, Singh O, Sundaravadanam Y, et al. Epigenomic, genomic, and transcriptomic landscape of schwannomatosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;141:101–116. doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02230-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simanshu DK, Nissley DV, McCormick F. RAS proteins and their regulators in human disease. Cell. 2017;170:17–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schubbert S, Zenker M, Rowe SL, Böll S, Klein C, Bollag G, van der Burgt I, Musante L, Kalscheuer V, Wehner LE, et al. Germline KRAS mutations cause Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:331–336. doi: 10.1038/ng1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aoki Y, Niihori T, Banjo T, Okamoto N, Mizuno S, Kurosawa K, Ogata T, Takada F, Yano M, Ando T, et al. Gain-of-function mutations in RIT1 cause Noonan syndrome, a RAS/MAPK pathway syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castel P, Cheng A, Cuevas-Navarro A, Everman DB, Papageorge AG, Simanshu DK, Tankka A, Galeas J, Urisman A, McCormick F. RIT1 oncoproteins escape LZTR1-mediated proteolysis. Science. 2019;363:1226–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.aav1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Umeki I, Niihori T, Abe T, Kanno SI, Okamoto N, Mizuno S, Kurosawa K, Nagasaki K, Yoshida M, Ohashi H, et al. Delineation of LZTR1 mutation-positive patients with Noonan syndrome and identification of LZTR1 binding to RAF1-PPP1CB complexes. Hum Genet. 2019;138:21–35. doi: 10.1007/s00439-018-1951-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abe T, Umeki I, Kanno SI, Inoue SI, Niihori T, Aoki Y. LZTR1 facilitates polyubiquitination and degradation of RAS-GTPases. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:1023–1035. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0395-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steklov M, Pandolf S, Baietti MF, Batiuk A, Carai P, Najm P, Zhang M, Jang H, Renzi F, Cai Y, et al. Mutations in LZTR1 drive human disease by dysregulating RAS ubiquitination. Science. 2018;362:1177–1182. doi: 10.1126/science.aap7607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zinatizadeh MR, Momeni SA, Zarandi PK, Chalbatani GM, Dana H, Mirzaei HR, Akbari ME, Miri SR. The role and function of Ras-association domain family in cancer: A Review. Genes Dis. 2019;6:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2019.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tidyman WE, Rauen KA. Pathogenetics of the RASopathies. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:R123–R132. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Malaquias AC, Jorge AAL. Activation of the MAPK pathway (RASopathies) and partial growth hormone insensitivity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2021;519:111040. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2020.111040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Humphries B, Wang Z, Yang C. Rho GTPases: Big Players in Breast Cancer Initiation, Metastasis and Therapeutic Responses. Cells. 2020;9:2167. doi: 10.3390/cells9102167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lavoie H, Gagnon J, Therrien M. ERK signalling: A master regulator of cell behaviour, life and fate. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:607–632. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moore AR, Rosenberg SC, McCormick F, Malek S. RAS-targeted therapies: Is the undruggable drugged? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:533–552. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-0089-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cirstea IC, Kutsche K, Dvorsky R, Gremer L, Carta C, Horn D, Roberts AE, Lepri F, Merbitz-Zahradnik T, König R, et al. A restricted spectrum of NRAS mutations causes Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2010;42:27–29. doi: 10.1038/ng.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Higgins EM, Bos JM, Mason-Suares H, Tester DJ, Ackerman JP, MacRae CA, Sol-Church K, Gripp KW, Urrutia R, Ackerman MJ. Elucidation of MRAS-mediated Noonan syndrome with cardiac hypertrophy. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e91225. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.91225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Flex E, Jaiswal M, Pantaleoni F, Martinelli S, Strullu M, Fansa EK, Caye A, De Luca A, Lepri F, Dvorsky R, et al. Activating mutations in RRAS underlie a phenotype within the RASopathy spectrum and contribute to leukaemogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:4315–4327. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ratner N, Miller SJ. A RASopathy gene commonly mutated in cancer: The neurofibromatosis type 1 tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:290–301. doi: 10.1038/nrc3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dunnett-Kane V, Burkitt-Wright E, Blackhall FH, Malliri A, Evans DG, Lindsay CR. Germline and sporadic cancers driven by the RAS pathway: Parallels and contrasts. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:873–883. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Johnston JJ, van der Smagt JJ, Rosenfeld JA, Pagnamenta AT, Alswaid A, Baker EH, Blair E, Borck G, Brinkmann J, Craigen W, et al. Members of the Undiagnosed Diseases Network Autosomal recessive Noonan syndrome associated with biallelic LZTR1 variants. Genet Med. 2018;20:1175–1185. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aoki Y, Niihori T, Inoue S, Matsubara Y. Recent advances in RASopathies. J Hum Genet. 2016;61:33–39. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2015.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Motta M, Fidan M, Bellacchio E, Pantaleoni F, Schneider-Heieck K, Coppola S, Borck G, Salviati L, Zenker M, Cirstea IC, et al. Dominant Noonan syndrome-causing LZTR1 mutations specifically affect the Kelch domain substrate-recognition surface and enhance RAS-MAPK signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2019;28:1007–1022. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pagnamenta AT, Kaisaki PJ, Bennett F, Burkitt-Wright E, Martin HC, Ferla MP, Taylor JM, Gompertz L, Lahiri N, Tatton-Brown K, et al. DDD Study Delineation of dominant and recessive forms of LZTR1-associated Noonan syndrome. Clin Genet. 2019;95:693–703. doi: 10.1111/cge.13533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rodriguez-Viciana P, Oses-Prieto J, Burlingame A, Fried M, McCormick F. A phosphatase holoenzyme comprised of Shoc2/Sur8 and the catalytic subunit of PP1 functions as an M-Ras effector to modulate Raf activity. Mol Cell. 2006;22:217–230. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Young LC, Hartig N, Muñoz-Alegre M, Oses-Prieto JA, Durdu S, Bender S, Vijayakumar V, Vietri Rudan M, Gewinner C, Henderson S, et al. An MRAS, SHOC2, and SCRIB complex coordinates ERK pathway activation with polarity and tumorigenic growth. Mol Cell. 2013;52:679–692. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shi GX, Cai W, Andres DA. Rit subfamily small GTPases: Regulators in neuronal differentiation and survival. Cell Signal. 2013;25:2060–2068. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khalil A, Nemer G. The potential oncogenic role of the RAS-like GTP-binding gene RIT1 in glioblastoma. Cancer Biomark. 2020;29:509–519. doi: 10.3233/CBM-191264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Van R, Cuevas-Navarro A, Castel P, McCormick F. The molecular functions of RIT1 and its contribution to human disease. Biochem J. 2020;477:2755–2770. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20200442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Song Z, Liu T, Chen J, Ge C, Zhao F, Zhu M, Chen T, Cui Y, Tian H, Yao M, et al. HIF-1α-induced RIT1 promotes liver cancer growth and metastasis and its deficiency increases sensitivity to sorafenib. Cancer Lett. 2019;460:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Venugopal V, Romero CJ. Endocrine complications of Noonan syndrome beyond short stature. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2019;16(Suppl 2):465–470. doi: 10.17458/per.vol16.2019.vr.endocrinecomplicationsnoonan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Soucy TA, Smith PG, Milhollen MA, Berger AJ, Gavin JM, Adhikari S, Brownell JE, Burke KE, Cardin DP, Critchley S, et al. An inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme as a new approach to treat cancer. Nature. 2009;458:732–736. doi: 10.1038/nature07884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jin J, Ang XL, Shirogane T, Wade Harper J. Identification of substrates for F-box proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2005;399:287–309. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)99020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li S, Balmain A, Counter CM. A model for RAS mutation patterns in cancers: Finding the sweet spot. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:767–777. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pierpont ME, Brueckner M, Chung WK, Garg V, Lacro RV, McGuire AL, Mital S, Priest JR, Pu WT, Roberts A, et al. American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine Genetic Basis for Congenital Heart Disease: Revisited: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;138:e653–e711. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tajan M, Paccoud R, Branka S, Edouard T, Yart A. The RASopathy family: Consequences of germline activation of the RAS/MAPK pathway. Endocr Rev. 2018;39:676–700. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kamihara J, Bourdeaut F, Foulkes WD, Molenaar JJ, Mossé YP, Nakagawara A, Parareda A, Scollon SR, Schneider KW, Skalet AH, et al. Retinoblastoma and neuroblastoma predisposition and surveillance. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:e98–e106. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dolecek TA, Propp JM, Stroup NE, Kruchko C. CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2005–2009. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(Suppl 5):v1–v49. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dunn GP, Rinne ML, Wykosky J, Genovese G, Quayle SN, Dunn IF, Agarwalla PK, Chheda MG, Campos B, Wang A, et al. Emerging insights into the molecular and cellular basis of glioblastoma. Genes Dev. 2012;26:756–784. doi: 10.1101/gad.187922.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee E, Yong RL, Paddison P, Zhu J. Comparison of glioblastoma (GBM) molecular classification methods. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018;53:201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liang Y, Diehn M, Watson N, Bollen AW, Aldape KD, Nicholas MK, Lamborn KR, Berger MS, Botstein D, Brown PO, et al. Gene expression profiling reveals molecularly and clinically distinct subtypes of glioblastoma multiforme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5814–5819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402870102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mischel PS, Nelson SF, Cloughesy TF. Molecular analysis of glioblastoma: Pathway profiling and its implications for patient therapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:242–247. doi: 10.4161/cbt.2.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Diehn M, Nardini C, Wang DS, McGovern S, Jayaraman M, Liang Y, Aldape K, Cha S, Kuo MD. Identification of noninvasive imaging surrogates for brain tumor gene-expression modules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5213–5218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801279105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Phillips HS, Kharbanda S, Chen R, Forrest WF, Soriano RH, Wu TD, Misra A, Nigro JM, Colman H, Soroceanu L, et al. Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:157–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Frattini V, Trifonov V, Chan JM, Castano A, Lia M, Abate F, Keir ST, Ji AX, Zoppoli P, Niola F, et al. The integrated landscape of driver genomic alterations in glioblastoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1141–1149. doi: 10.1038/ng.2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lein PJ, Guo X, Shi GX, Moholt-Siebert M, Bruun D, Andres DA. The novel GTPase Rit differentially regulates axonal and dendritic growth. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4725–4736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5633-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cai W, Rudolph JL, Harrison SM, Jin L, Frantz AL, Harrison DA, Andres DA. An evolutionarily conserved Rit GTPase-p38 MAPK signaling pathway mediates oxidative stress resistance. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:3231–3241. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e11-05-0400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shi GX, Andres DA. Rit contributes to nerve growth factor-induced neuronal differentiation via activation of B-Raf-extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:830–846. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.830-846.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shi GX, Han J, Andres DA. Rin GTPase couples nerve growth factor signaling to p38 and b-Raf/ERK pathways to promote neuronal differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37599–37609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507364200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rusyn EV, Reynolds ER, Shao H, Grana TM, Chan TO, Andres DA, Cox AD. Rit, a non-lipid-modified Ras-related protein, transforms NIH3T3 cells without activating the ERK, JNK, p38 MAPK or PI3K/Akt pathways. Oncogene. 2000;19:4685–4694. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Knudson AG., Jr Mutation and cancer: Statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:820–823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ren R. Mechanisms of BCR-ABL in the pathogenesis of chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:172–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Garcia-Horton A, Lipton JH. Treatment outcomes in chronic myeloid leukemia: Does one size fit all? J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18:1421–1428. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Crisà E, Nicolosi M, Ferri V, Favini C, Gaidano G, Patriarca A. Atypical chronic myeloid leukemia: Where are we now? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:6862. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Braun TP, Eide CA, Druker BJ. Response and resistance to BCR-ABL1-targeted therapies. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:530–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Vetrie D, Helgason GV, Copland M. The leukaemia stem cell: Similarities, differences and clinical prospects in CML and AML. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:158–173. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Evans DG, Bowers NL, Tobi S, Hartley C, Wallace AJ, King AT, Lloyd SK, Rutherford SA, Hammerbeck-Ward C, Pathmanaban ON, et al. Schwannomatosis: A genetic and epidemiological study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89:1215–1219. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Farschtschi S, Mautner VF, Cooper DN. The molecular pathogenesis of schwannomatosis, a paradigm for the co-involvement of multiple tumour suppressor genes in tumorigenesis. Hum Genet. 2017;136:129–148. doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1753-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Smith MJ, Isidor B, Beetz C, Williams SG, Bhaskar SS, Richer W, O'Sullivan J, Anderson B, Daly SB, Urquhart JE, et al. Mutations in LZTR1 add to the complex heterogeneity of schwannomatosis. Neurology. 2015;84:141–147. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yamamoto GL, Aguena M, Gos M, Hung C, Pilch J, Fahiminiya S, Abramowicz A, Cristian I, Buscarilli M, Naslavsky MS, et al. Rare variants in SOS2 and LZTR1 are associated with Noonan syndrome. J Med Genet. 2015;52:413–421. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lamlum H, Ilyas M, Rowan A, Clark S, Johnson V, Bell J, Frayling I, Efstathiou J, Pack K, Payne S, et al. The type of somatic mutation at APC in familial adenomatous polyposis is determined by the site of the germline mutation: A new facet to Knudson's ‘two-hit’ hypothesis. Nat Med. 1999;5:1071–1075. doi: 10.1038/12511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hulsebos TJ, Plomp AS, Wolterman RA, Robanus-Maandag EC, Baas F, Wesseling P. Germline mutation of INI1/SMARCB1 in familial schwannomatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:805–810. doi: 10.1086/513207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Paganini I, Chang VY, Capone GL, Vitte J, Benelli M, Barbetti L, Sestini R, Trevisson E, Hulsebos TJ, Giovannini M, et al. Expanding the mutational spectrum of LZTR1 in schwannomatosis. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:963–968. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Smith MJ, Pathmanaban ON, Coope DJ, King AT, Evans DG. Comment on: SMARCB1 gene mutation predisposes to earlier development of glioblastoma: A case report of familial GBM. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2021;80:289–290. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlaa105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Fonkem E, Peng S, Berens M, Mukherjee S. Authors' reply: SMARCB1 gene mutation predisposes to earlier development of glioblastoma: A case report of familial GBM. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2021;80:290–291. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlaa105.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Louvrier C, Pasmant E, Briand-Suleau A, Cohen J, Nitschké P, Nectoux J, Orhant L, Zordan C, Goizet C, Goutagny S, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing for differential diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 2, schwannomatosis, and meningiomatosis. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20:917–929. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Maurer GW, Malita A, Nagy S, Koyama T, Werge TM, Halberg KA, Texada MJ, Rewitz K. Analysis of genes within the schizophrenia-linked 22q11.2 deletion identifies interaction of night owl/LZTR1 and NF1 in GABAergic sleep control. PLoS Genet. 2020;16:e1008727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ballester R, Marchuk D, Boguski M, Saulino A, Letcher R, Wigler M, Collins F. The NF1 locus encodes a protein functionally related to mammalian GAP and yeast IRA proteins. Cell. 1990;63:851–859. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Liu P, Wang Y, Li X. Targeting the untargetable KRAS in cancer therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019;9:871–879. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Buscail L, Bournet B, Cordelier P. Role of oncogenic KRAS in the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:153–168. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Krastev DB, Buchholz F. Ribosome biogenesis and p53: Who is regulating whom? Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3417–3418. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.20.17687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Weiss RA. A perspective on the early days of RAS research. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020;39:1023–1028. doi: 10.1007/s10555-020-09919-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Uprety D, Adjei AA. KRAS: From undruggable to a druggable cancer target. Cancer Treat Rev. 2020;89:102070. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chen H, Zhao J. KRAS oncogene may be another target conquered in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Thorac Cancer. 2020;11:3425–3435. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Goulding RE, Chenoweth M, Carter GC, Boye ME, Sheffield KM, John WJ, Leusch MS, Muehlenbein CE, Li L, Jen MH, et al. KRAS mutation as a prognostic factor and predictive factor in advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2020;24:100200. doi: 10.1016/j.ctarc.2020.100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Passiglia F, Malapelle U, Del Re M, Righi L, Pagni F, Furlan D, Danesi R, Troncone G, Novello S. KRAS inhibition in non-small cell lung cancer: Past failures, new findings and upcoming challenges. Eur J Cancer. 2020;137:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Matthew B, Juliati R, Field SJ. GOLPH3 links the Golgi, DNA damage, and cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:624–627. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.