Abstract

This study was designed to assess the psychometric properties of a pictorial scale of correct condom use (PSCCU) using data from female sex workers (FSWs) in China. The psychometric properties assessed in this study include construct validity by correlations and known-group validation. The study sample included 396 FSWs in Guangxi, China. The results demonstrate adequate validity of the PSCCU among the study population. FSWs with a higher level of education scored significantly higher on the PSCCU than those with a lower level of education. FSWs who self-reported appropriate condom use with stable partners scored significantly higher on PSCCU than their counterparts. The PSCCU should provide HIV/STI prevention researchers and practitioners with a valid alternative assessment tool among high-risk populations, especially in resource-limited settings.

Keywords: Pictorial scale, Validity, Condom use, Female sex workers, China

Introduction

Behavioral skills to correctly use a male latex condom are critical to the prevention of HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Other than abstinence, protected sex with correct condom use (proper use without error) and consistent condom use (defined as using a condom for each act of sexual intercourse) [1] is the most effective preventive behavior against HIV and certain types of STIs (including gonorrhea, Chlamydia., etc.) [2–4]. Condom use errors have been noted to be prevalent among both general populations and high-risk groups (e.g., college students, STI clinic patients) [5–7].

While intervention studies often assess consistency of condom use, there has been relatively less emphasis placed on correct condom use in research and prevention [8, 9]. For example, in a review of 45 studies published during 1966–2004 regarding the effectiveness of condom use against the transmission of gonorrhea and/or chlamydia, only two (4%) studies reported the incorrect use of condom (e.g., failure to use throughout genital contact), while 28 studies (62%) assessed consistent condom use [2]. In another review of 12 studies published during 1972–2008 assessing the effectiveness of condom use against the transmission of syphilis, none of them assessed correct use or condom use problems, while 11 studies assessed consistent use of condom [10]. Concerns have been raised that promoting condom use without ensuring necessary skills for correct use may result in increased exposure to HIV/STI [11, 12].

Valid, reliable, and simple assessment tools of correct condom use are needed to monitor and evaluate condom use behaviors in HIV/STI prevention programs [8, 9]. Correct condom use was operationalized as proper steps and skills of condom use and successful prevention of inadvertent or advertent condom use errors and failures (e.g., breakage and slippage) [13]. Generally, the methods of assessing correct condom use have included self-reports and direct observation of condom use behaviors and errors, with direct observation as the gold standard [14, 15]. Some self-report measures assess a single step in condom use, such as putting on a condom before penetration [16], while some other self-report measures assess knowledge of multiple important steps in condom use (e.g., checklists). For example, one study among the Bahamaion adolescents used a checklist of 17 items and reported high agreement between the checklist and the observed condom use skills [14]. Checklists were also used to assess specific errors in condom use, such as “beginning sex without a condom, taking it off before finishing sex, flipping it over, condom breakage, or condom slippage” [1, p. 536]. The direct observation typically involves behavioral assessment of correct condom skills on a penile model [12].

Both self-report and direct observation of correct condom use are subject to some methodological or logistic limitations. Self-report of correct use of condoms is subject to potential biases due to socially desirable response and the error of recall [17]. Direct observation may be difficult to implement and participants may perform this sensitive behavior differently in a research condition than they would in actual sexual encounters [17]. Direct observations of condom use in a penile model may also not be feasible in group settings or with limited research personnel [14]. Direct observation in a large group of high-risk populations would require substantial time and resources, and specifically trained personnel. In contrast, research in other fields has demonstrated that a pictorial assessment scale was simple and easy to administer, held participants’ attention, and led to reliable response among populations with low literacy [18]. Therefore, it is reasonable to propose the pictorial assessment as a practical tool and a proxy measure of knowledge of correct condom use. The pictorial assessment of correct condom use could be particularly useful in large group settings, where direct observation of the condom use skills is not feasible, or for some vulnerable or at-risk populations with limited literacy including rural residents, rural-to-urban migrants, and commercial sex workers.

Previous studies have suggested that correct use of condoms is associated with multiple constructs. Condom use is a motivated behavior between sexual partners, achieved through communication and negotiation. According to Bandura [19], executing self-protective behaviors to prevent HIV/STI infection relies on the knowledge of health risk, skills to translate health concerns into preventive action, and perceived self-efficacy and confidence about the ability to perform a behavior in challenges [19]. At the individual level, educational attainment is associated with self-protective behaviors. One study among Malawian young women reported that those with at least secondary school education were 40% more likely to report correct condom use than those with less than a secondary education [20]. Previous studies have reported significant correlations between condom use skills and condom use self-efficacy among female college students [17]. Another study reported that men’s motivation to use condoms had a direct and positive effect on perceived skills to use condoms correctly, perhaps resulting from perceived susceptibility and severity regarding the risk of HIV/STI and pregnancy [21]. However, some studies have found no correlation between condom use skills (e.g., directly observed or self-report checklist) and condom use self-efficacy [14, 15]. Existing research indicates that HIV/STI knowledge is positively associated with condom use skills and perceived benefits of unprotected sex were negatively associated with condom use [22]. In the interpersonal level, condom use communication is critical for condom use [23], and especially for correct condom use [15, 24]. Condom use negotiation may be particularly important for correct condom use in the context where there was gender inequality in power, control, and resource between the sexual partners, as, for example, in the context of commercial sex.

Female sex workers (FSWs) in China require special attention on assessing correct condom use because of low education and gender inequality in the negotiation of condom use with clients [25]. Entertainment establishments have become the common form of commercial sex in China in the past three decades [26]. FSWs were under varied control by entertainment establishments’ managers and gatekeepers; and lack of gatekeeper support and abusive FSW-gatekeeper relationships were barriers to condom use [27]. Unlike the Philippines or the Dominican Republic, China has no mandatory condom use policy or HIV/STI testing programs by the government to protect the FSWs [26]. Consistent and correct condom use becomes the last means of vulnerable FSWs in China to protect themselves.

The main objective of this study was to assess the psychometric properties of a pictorial scale of correct condom use (PSCCU) using data from FSWs in Guangxi. The psychometric properties included construct validity by correlations and by known-group validation. Based on the findings from the previous studies, we hypothesized that HIV/STI knowledge, perceived susceptibility and severity, condom use self-efficacy, and condom use communication will be positively associated with PSCCU scores; perceived benefits of unprotected sex and misconception of HIV transmission will be negatively associated with PSCCU scores; and FSWs with less education will have lower scores of PSCCU then those with more education.

Method

Study Site

The data in the current study were derived from the baseline assessment of a community-based voluntary counseling and testing intervention study in 2004 in a rural county in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (“Guangxi”) [28]. Being one of five autonomous and multiethnic regions and located in southern China, Guangxi has experienced an alarming rise in HIV prevalence in the past decade. A total of 48,703 HIV/AIDS cases were reported as of June 2009, which placed Guangxi second among Chinese provinces in terms of cumulative numbers of reported HIV cases [29]. A prosperous economy, increased international contact, and booming tourism in Guangxi have created a market for commercial sex. According to the statistics from the public security agency, there are at least 50,000 FSWs in Guangxi. The participating country had an estimated 200 commercial sex establishments, with more than 2,000 women engaging in commercial sex service at the time of the study.

Participants and Survey

Detailed recruitment and survey procedures have been described elsewhere [16, 22, 28]. Briefly, the research team conducted an ethnographic mapping [30] of entertainment establishments providing sexual services and identified 85 such establishments (i.e., restaurants, barbershops, and hairwashing rooms) in the survey areas, among which 57 (67%) agreed to allow the researchers to contact the FSWs in their establishments. Trained outreach health workers from the county anti-epidemic station and local hospitals contacted 582 women in these establishments, of whom 454 (78%) agreed to participate, provided written informed consent, and completed a self-administered questionnaire. Because 59 women (13.0%) had missing values on the pictorial assessment, the final sample in the current study included 395 women.

The survey, including the pictorial assessment of correct condom use, was confidential and conducted in private spaces. No one was allowed to stay with the participant during the survey except the interviewer who provided the participant with necessary assistance. The survey took about 1 h to complete. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at Wayne State University in the U.S., Beijing Normal University, and Guangxi Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in China.

Pictorial Scale of Correct Condom Use (PSCCU)

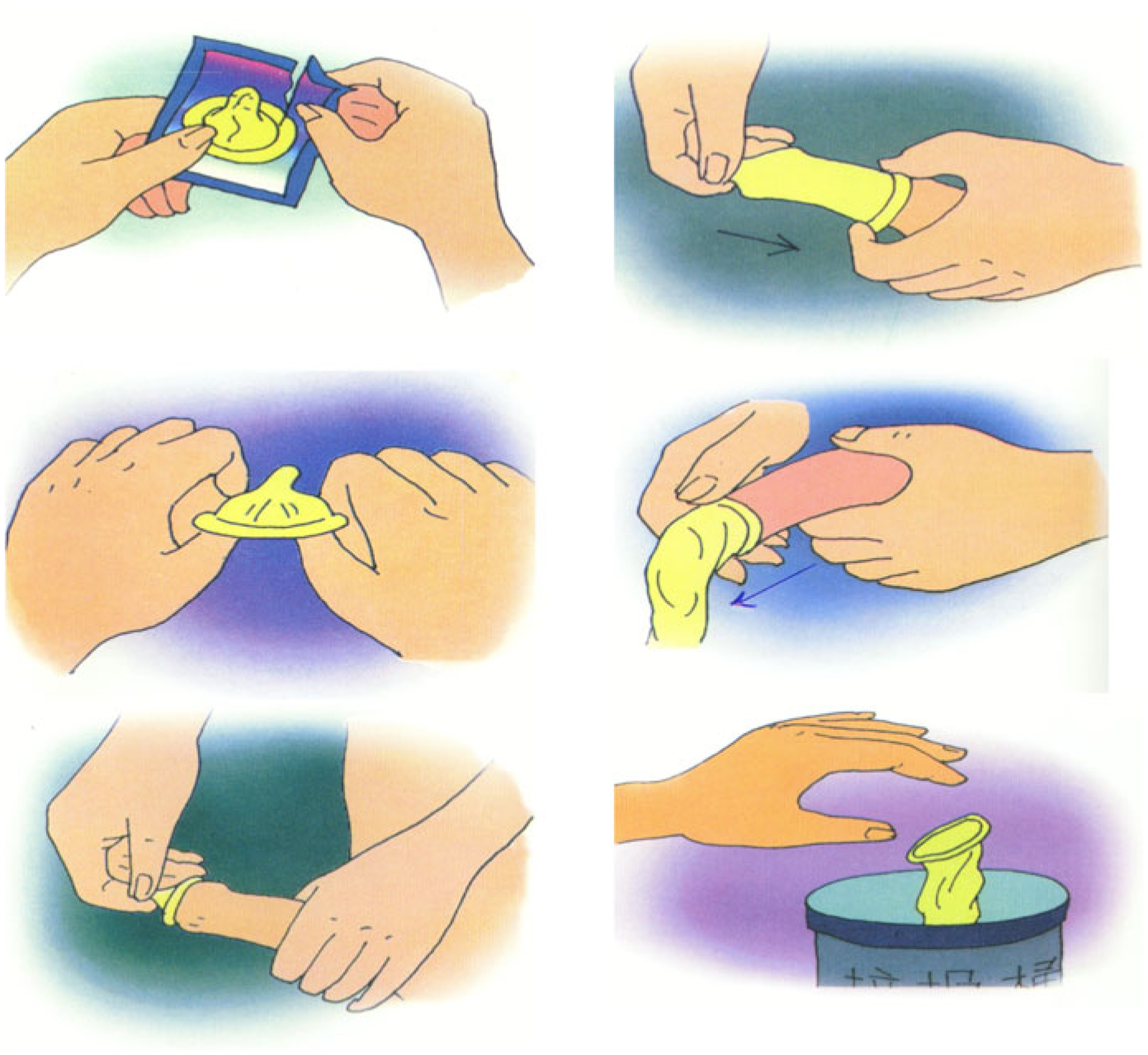

Participants were asked to sort six preprinted pictorial cards describing six major steps of condom use. As shown in Fig. 1, the six steps were (1) tear the condom package carefully; (2) identify the rolling direction of the condom; (3) pinch the air out of the tip and roll the condom down the erect penis before sexual intercourse; (4) roll the condom all the way down until it wraps the whole penis; (5) after sexual intercourse, withdraw the penis before it gets soft, hold the base when doing so, and then roll the condom off; and (6) tie the used condom and throw it away in a trash can. The participants were presented with the cards in a random order and were asked to arrange all cards in the correct order. These steps are commonly used in many condom use guidelines or handbooks in the field of HIV/ STD education and prevention [31].

Fig. 1.

Six cards in the pictorial scale of correct condom use

Using a procedure developed by Wright and colleagues [32], a picture sequencing score can be calculated for each participant based on two criteria: closeness of each picture was to its correct absolute position and number of pictures that were sequenced correctly, regardless of their absolute position. To calculate these scores, each picture was initially numbered from 1 to 6 indicating its correct order. One point was given for every picture with a lower number that was placed to its left (maximum possible score of 15), and one point was given for each correctly adjacent pairs of pictures (maximum possible score of 5). The two scores were added, yielding a maximum score of 20, with higher scores indicating higher knowledge of correct condom use [22]. Because of the relative complexity of calculating the picture sequencing score, we also employed a dichotomous scale (yes/no) which has been employed previously [16], in which only those participants who arranged all cards in the correct order were credited with correct condom use.

Other Measures

Demographic and Working Characteristics

Demographic information collected included age, ethnicity including Han or non-Han (e.g., Zhuang, Jingpo, Tong, and other ethnical minorities), literacy level in terms of years of formal schooling, marital status (i.e., currently married, unmarried or divorce), and having children. Working characteristics included how long they had been working in commercial sex, monthly income, and average clients per week.

Consistent Condom Use with Clients or Stable Partners

Participants were asked whether they always used a condom with clients or stable partners (ever or during the 3 most recent sexual encounters). Stable partners included husband, fiancé, boyfriend, or long-term commercial partners.

Appropriate Use of Condoms with Clients or Stable Partners

Participants were asked how often they and their clients (or stable partners) put on a condom before penetration (never, occasionally, sometimes, often, or always).

HIV/STI Knowledge

Twenty-two items were employed to assess participants’ knowledge of STI symptoms (10 items), HIV transmission modes (6 items), and misconception of HIV transmission through routine daily contact (6 items). The internal consistency estimates (Cronbach α) for three knowledge subscales were 0.87, 0.90, and 0.83, respectively. The sum of the number of correct answers to each subscale as well as the 22 knowledge questions were retained as a composite score for each relevant subscale and overall STI/HIV knowledge, with higher scores reflecting increased knowledge about the transmission and symptoms of HIV/STI.

Condom Use Communication with Clients or Stable Partners

Participants were asked whether they have ever discussed condom use with their clients or stable partners (yes/no).

Condom Use Intention

It was measured by a single item asking participants how often they would use a condom in the future (never, occasionally, sometimes, often, and always).

Susceptibility

It was assessed by asking participants to rate their perceptions regarding the likelihood of acquiring HIV and STI infection (e.g., “how likely do you think it is that you would get an STI [HIV] in the future?”). This 2-item scale had a Cronbach α of 0.65. A composite score was created by summing the numbers of positive responses (e.g., likely) across 2 items. A higher score indicated a higher level of perceived susceptibility.

Severity

Participants were asked to assess their perceptions regarding negative consequences resulting from being infected with HIV (e.g., “one will lose his/her friends if he/she becomes infected with HIV”). The Cronbach α for this 3-item scale was 0.71. A composite score was created by summing the numbers of positive responses (e.g., agree) across the 3 items. A higher score indicated a higher level of perceived severity.

Condom Use Self-Efficacy

Four items were used to assess personal belief about one’s ability to use a condom (e.g., “I can persuade my client to use a condom if he is unwilling to use it;” “I will refuse to have sex if my client does not want to use a condom.”) The Cronbach α for this scale was 0.47. A composite score was created by summing the numbers of positive responses (e.g., agree) of the 4 items. A higher score indicated a higher level of self-efficacy.

Perceived Benefits

Five items were employed to measure perceived benefits of unprotected sex (e.g., “if I do not use condoms, my clients will pay me more;” “if I do not use condoms, my clients will come back in the future”). The Cronbach α was 0.75. A composite score was created by summing the numbers of positive responses (e.g., agree) of the 5 items. A higher score reflected a higher level of perceived benefits of unprotected sex.

STI Biomarkers

Screening was conducted by trained STI clinicians and laboratory technicians for five common STIs (Neisseria gonorrhoeae, chlamydia trachomatis, trichomoniasis, syphilis, and genital warts). STI Biomarkers were defined as being positive for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, chlamydia trachomatis, or trichomoniasis. Because condom use could not completely prevent certain STIs (e.g., syphilis, genital warts) which might be transmitted through contact with skin or mucosal surfaces [2], syphilis and genital warts were excluded from the analysis. Cervical swab specimens were obtained from women to detect N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, and trichomonas vaginalis. N. gonorrhoeae was identified using the standard culture procedure. Chlamydial infection was detected by rapid antigen test (Clearview, Unipath, UK). Trichomoniasis was diagnosed by detecting the motile parasite under a microscope. All STI assays were conducted at the county antiepidemic station STI Laboratory. Investigators from the China CDC National Resource Center for STI Control provided training, supervision and quality control for all STI testing and diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

The SAS Version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to manage and analyze data. The differences in socio-demographic, knowledge and perceptions, attitudes, behavioral characteristics, and STI biomarkers between two groups in the dichotomous score of PSCCU were assessed by χ2 (for categorical variables) and analysis of variance (for continuous variables). Construct validity was assessed using Pearson correlation coefficients and χ2 tests between PSCCU and other related measures (knowledge, attitudes and perceptions, behavioral characteristics, STI biomarker, condom communication skills, and condom use intention). We anticipated that the PSCCU scale would have a relatively higher correlation with scales measuring constructs in social cognitive theory (e.g., HIV/STI knowledge, condom use self-efficacy, susceptibility, severity, perceived benefits) and a relatively lower correlation with other scales (e.g., condom use intention). The construct validity of PSCCU was assessed using the known-group validation procedure [33]. We anticipated that FSWs with more education or those who reported appropriate condom use (e.g., always putting a condom on before penetration) with either clients or stable partners would be more likely to achieve a higher score on the PSCCU. To explore the possible difference in the two scoring systems of PSCCU, the analyses were conducted with both the picture sequencing (continuous) score and the dichotomous score of PSCCU.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the sample of 395 FSWs, 60.3% demonstrated correct use of condoms based on dichotomous scoring of the PSCCU and had a mean score of 17.7 (SD = 3.2) with the continuous scoring of the PSCCU. The continuous and dichotomous scoring of the PSCCU were highly correlated (correlation coefficient = 0.88, P < 0.0001). Most participants were Han ethnicity (55.7%), unmarried or divorce (63.8%), and young (23.7, SD = 5.0 years old) (Table 1). Mean education was 6.0 (SD = 3.2) years; 54% had no more than 6 years of education and 39.7% had a child. They had worked as sex workers for an average of 13.0 months and each woman had an average of 2.1 clients per week. Compared with their counterparts who did not demonstrate correct condom use, FSWs with a correct score were more likely to be Han ethnicity and have more than 6 years of education (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and work-related characteristic of 395 female sex workers, stratified by dichotomous scale of pictorial scale of condom use, Guangxi, China, 2004

| Characteristics N (%) | Total (n = 395) | Correct condom use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 157) | Yes (n = 238) | ||

| Age (SD) | 23.7 (5.0) | 23.3 (4.9) | 24.0 (5.0) |

| Han ethnicity | 55.7% | 49.4% | 60.1%* |

| Education >6 years | 46.3% | 33.5% | 54.9%* |

| Having a child | 39.7% | 39.2% | 39.7% |

| Unmarried or divorce | 63.8% | 64.7% | 63.5% |

| Average clients per weeks (SD) | 2.1 (1.8) | 2.0 (1.7) | 2.1 (2.0) |

| Work length in months (SD) | 13.0 (12.5) | 11.7 (12.0) | 13.9 (12.8) |

P < 0.01

Correlations Between PSCCU and Other Condom Use Measures

The associations of the dichotomous PSCCU score with various measures are shown in Table 2. The average condom use self-efficacy score was 2.6 (±1.2). The average susceptibility score was 0.3 (±0.6). The average severity score was 1.8 (±1.2). The average HIV/STI knowledge score was 10.6 (±5.2). The average perceived benefits score was 1.8 (±1.7). Compared with their counterparts whose PSCCU score indicated incorrect condom use, FSWs with correct use of condom were more likely to have higher condom use self-efficacy (P < 0.01), higher HIV/STI knowledge, high knowledge about STI symptoms, self-reported appropriate use of condoms with stable partners, more condom use communication with stable partners, and lower rates of STI biomarkers (each P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Knowledge, perceptions, behaviors, and infectious biomarkers of 395 female sex workers, stratified by dichotomous scale of pictorial scale of condom use skill, Guangxi, China, 2004

| Characteristics N (%) | Total (n = 395) | Correct condom use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 157) | Yes (n = 238) | ||

| HIV/STI knowledge (SD) | 10.6 (5.2) | 9.9 (5.2) | 11.1 (5.2)* |

| STI symptoms (SD) | 3.5 (2.9) | 3.1 (2.7) | 3.7 (2.9)* |

| HIV transmission modes (SD) | 4.7 (2.0) | 4.4 (2.1) | 4.9 (1.9) |

| Misconception of HIV transmission (SD) | 2.7 (2.0) | 2.8 (2.1) | 2.7 (2.0) |

| Susceptibility (SD) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.6) |

| Severity (SD) | 1.8 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.2) |

| Perceived benefits (SD) | 1.8 (1.7) | 1.9 (1.7) | 1.8 (1.7) |

| Condom use self-efficacy (SD) | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.4 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.1)** |

| Consistent condom use with clients ever | 16.2% | 17.3% | 15.6% |

| Consistent condom use with clients P3T | 26.2% | 25.2% | 27.0% |

| Appropriate condom use with clients | 72.3% | 67.7% | 75.2% |

| Condom use communication with clients | 81.3% | 80.0% | 82.1% |

| Consistent condom use with stable partners evera | 9.2% | 9.0% | 9.4% |

| Consistent condom use with stable partners P3Ta | 15.2% | 14.4% | 15.8% |

| Appropriate condom use with stable partnersa | 61.6% | 46.8% | 70.0%* |

| Condom use communication with stable partnersa | 62.4% | 54.1% | 68.2%* |

| Condom use intention | 56.7% | 54.5% | 58.0% |

| Any STI biomarker | 43.2% | 51.1% | 38.3%** |

P < 0.01,

P < 0.05;

P3T = in past 3 times

Data were only available for 283 female sex workers with stable partners

The correlations of continuous and dichotomous scores of PSCCU with relevant measures (Table 3) were similar. Significant correlations were found between the PSCCU and condom use self-efficacy, condom use communication with stable partners, and appropriate condom use with stable partners (each P ≤ 0.01). Significant but relatively weak correlations occurred between the continuous score of PSCCU and HIV/STI knowledge and two subscales (STI symptoms and HIV transmission modes), and STI biomarkers (each P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Knowledge, perceptions, behaviors, and infectious biomarkers of 395 female sex workers, stratified by continuous scale of pictorial scale of condom use skill, Guangxi, China, 2004

| Characteristics | Total | <16 n = 66 |

=16 n = 91 |

=20 n = 238 |

Correlation coefficients | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV/STI knowledge | 10.6 (5.2) | 9.6 (4.8) | 10.5 (5.4) | 11.1(5.2) | 0.118 | 0.017 |

| STI symptoms | 3.5 (2.9) | 2.8 (2.7) | 3.3 (2.7) | 3.7 (2.9) | 0.125 | 0.013 |

| HIV transmission modes | 4.7 (2.0) | 4.5 (1.8) | 4.3 (2.3) | 4.9 (1.9) | 0.119 | 0.020 |

| Misconception of HIV transmission | 2.7 (2.0) | 2.8 (2.0) | 2.8 (2.1) | 2.7 (2.0) | −0.026 | 0.614 |

| Susceptibility | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.6) | −0.018 | 0.725 |

| Severity | 1.8 (1.2) | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.2) | 0.044 | 0.382 |

| Perceived benefits | 1.8 (1.7) | 2.1 (1.7) | 1.8 (1.7) | 1.8 (1.7) | −0.015 | 0.766 |

| Condom use self-efficacy | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.8 (1.1) | 0.211 | 0.001 |

| Consistent condom use with clients ever | 16.2% | 13.6% | 19.8% | 15.6% | 0.008 | 0.539 |

| Consistent condom use with clients P3T | 26.2% | 18.5% | 29.7% | 27.0% | 0.046 | 0.265 |

| Appropriate condom use with clients | 72.3% | 74.5% | 63.4% | 75.2% | 0.050 | 0.118 |

| Condom use communication with clients | 81.3% | 75.8% | 83.3% | 82.1% | 0.019 | 0.430 |

| Consistent condom use with stable partners evera | 9.2% | 2.4% | 12.9% | 9.4% | 0.062 | 0.176 |

| Consistent condom use with stable partners P3Ta | 15.2% | 7.1% | 18.6% | 15.8% | 0.059 | 0.249 |

| Appropriate condom use with stable partnersa | 61.6% | 50.0% | 45.5% | 70.0% | 0.192 | 0.010 |

| Condom use communication with stable partnersa | 62.4% | 40.5% | 61.4% | 68.2% | 0.170 | 0.002 |

| Condom use intention | 56.7% | 51.5% | 57.1% | 58.0% | 0.046 | 0.641 |

| Any STI biomarker | 43.2% | 57.7% | 47.0% | 38.3% | −0.130 | 0.029 |

P3T in past 3 times

Data were only available for 283 female sex workers with stable partners

Known-Group Validation

FSWs with more than 6 years of education were more likely to demonstrate correct condom use according to the dichotomously scored PSCCU (71.3%) than their counterparts (50.5%) (P < 0.0001). Likewise, FSWs with more than 6 years of education scored significantly higher on the continuous score of PSCCU (18.6 ± 2.4) than their counterparts with no more than 6 years of education (17.0 ± 3.5) (P < 0.0001). FSWs who reported appropriate condom use with clients scored similar with their counterparts on the continuous score of PSCCU (17.6 vs. 18.0, P = 0.35) and on the dichotomous score of PSCCU (75.2% vs. 67.7%, P = 0.13). However, FSWs who reported appropriate condom use with stable partners scored significantly higher than their counterparts on the continuous score of the PSCCU (18.6 vs. 17.5, P = 0.01) and correctly on the dichotomously scored PSCCU (70.0% vs. 46.8%, P < 0.01).

Discussion

Our analyses provide preliminary data that support the validity of the PSCCU as a measurement scale assessing the knowledge of correct condom use among a sample of FSWs with low literacy. The construct validity of the PSCCU was supported by the correlations between the PSCCU and measures with conceptually relevant constructs. The PSCCU showed reasonable psychometric properties with significant correlations with condom use self-efficacy, condom use communication with stable partners, and appropriate condom use with stable partners, and relatively weak correlations with HIV/STI knowledge and two of its subscales, and consistent condom use with stable partners. The construct validity of the PSCCU was also supported by known-group validation procedure. Consistent with the findings among Malawian young women [20]. FSWs with a higher level of education scored significantly higher on the PSCCU than those with a lower level of education.

While the continuous and dichotomous scoring of the PSCCU showed similar patterns in their psychometric properties, there were some small differences. The HIV transmission modes were not significantly correlated with the dichotomous scoring but were with the continuous scoring of the PSCCU. The correlation of self-reported appropriate use of condom with stable partners was weaker with the dichotomous score than with the continuous score. The continuous score of PSCCU is complex to calculate but provides more variance. The dichotomous score of PSCCU is simple but provides limited variance. The choice of the scoring system will depend on the computational capacity of a research team (e.g., feeling conformable with the calculation of the picture continuous score) or the target population (the more homogenous the sample is, the more similar the two scores will be). However, either of the scoring systems should provide a reasonable estimate of the knowledge of correct condom use as measured by the PSCCU.

The differences in condom use between FSWs with clients and stable partners, including husband, fiancé, boyfriend, or long-term commercial partners, have been reported previously [16, 34]. Our results of known-group validation of PSCCU confirmed such differences. While there was no significant overall association between PSCCU scores and self-reported appropriate condom use, the PSCCU scores were significantly associated with appropriate condom use with stable partners. FSWs who self-reported appropriate condom use with stable partners scored significantly higher on the PSCCU than their counterparts who did not report appropriate condom use with stable partners. Likewise, PSCCU scores were found to be significantly associated with condom use communication with stable partners. These differential patterns in the association between PSCCU score and other condom use measures might reflect limitations of the FSW’s control over condom use with clients compared with that with stable partners. Although some FSWs might know how to correctly use a condom, they might not be able to negotiate correct use with their clients.

This study is subject to several limitations. The PSCCU is an assessment of knowledge of condom use steps rather than the actual condom use skills. Therefore, it is a proxy measure of actual skills. Internal consistency estimates (Cronbach α) could not be calculated because of the single score produced by this pictorial scale. Incorrect items cannot be placed on the scale. In addition, direct condom use observation data was unavailable in the current study to further validate the PSCCU scores. Other limitations include the relatively homogeneous sample of FSWs from a single rural county in China, and relatively low reliability estimates for some of the measures (e.g., Cronbach α = 0.47 for condom use self-efficacy and 0.65 for susceptibility). Women’s HIV status was not assessed due to both low estimate infection rate (<1%) during the time of the survey and ethic consideration (i.e., no free or affordable treatment was available to these participants at the time of the study). Despite these potential limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the first efforts to evaluate the psychometric properties of a pictorial scale measuring correct condom use among a high-risk population with low literacy. The PSCCU could provide HIV/STI prevention researchers and practitioners with a valid assessment instrument in knowledge of correct steps of condom use. Further research is clearly needed to address these limitations, enhance the psychometric properties of the PSCCU, and ensure its reliability in other populations with low literacy, before being generalized to them.

In conclusion, correct condom use has been important for HIV/STI prevention. It is important to assess correct condom use among various at-risk or vulnerable populations. The PSCCU offers a reasonable alterative assessment tool for measuring condom use among those populations, especially in resource-limited settings.

Acknowledgments

The data analysis and preparation of this paper were supported by Grant R01AA018090 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health. Financial support for undertaking the survey was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health and the NIH Office of AIDS Research (R01MH064878-3S1).

References

- 1.Paz-Bailey G, Koumans EH, Sternberg M, et al. The effect of correct and consistent condom use on chlamydial and gonococcal infection among urban adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(6):536–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warner L, Stone KM, Macaluso M, Buehler JW, Austin HD. Condom use and risk of gonorrhea and Chlamydia: a systematic review of design and measurement factors assessed in epidemiologic studies. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(1):36–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmes KK, Levine R, Weaver M. Effectiveness of condoms in preventing sexually transmitted infections. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(6):454–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sparrow MJ. Condom failures in women presenting for abortion. N Z Med J. 1999;112(1094):319–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanders SA, Graham CA, Yarber WL, Crosby RA. Condom use errors and problems among young women who put condoms on their male partners. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58(2):95–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crosby RA, Sanders SA, Yarber WL, Graham CA, Dodge B. Condom use errors and problems among college men. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(9):552–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grimley DM, Annang L, Houser S, Chen H. Prevalence of condom use errors among STD clinic patients. Am J Health Behav. 2005;29(4):324–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sex Information and Education Council of the U.S. SIECUS fact sheet: comprehensive sexuality education. The truth about latex condoms. SIECUS Rep. 1993;21:17–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease Workshop Summary. Scientific evidence on condom effectiveness for sexually transmitted disease (STD) prevention. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services; Available at: http://www.niaid.nih.gov/dmid/stds/condomreport.pdf (2001). Accessed 21 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koss CA, Dunne EF, Warner L. A systematic review of epidemiologic studies assessing condom use and risk of syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(7):401–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindemann DF, Brigham TA, Harbke CR, Alexander T. Toward errorless condom use: a comparison of two courses to improve condom use skills. AIDS Behav. 2005;9(4):451–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.St Lawrence JS, Eldridge GD, Reitman D, Little CE, Shelby MC, Brasfield TL. Factors influencing condom use among African American women: implications for risk reduction interventions. Am J Community Psychol. 1998;26(1):7–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yarber WL, Graham CA, Sanders SA, Crosby RA. Correlates of condom breakage and slippage among university undergraduates. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15(7):467–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanton B, Deveaux L, Lunn S, et al. Condom-use skills checklist: a proxy for assessing condom-use knowledge and skills when direct observation is not possible. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009; 27(3):406–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langer LM, Zimmerman RS, Cabral RJ. Perceived versus actual condom skills among clients at sexually transmitted disease clinics. Public Health Rep. 1994;109(5):683–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang H, Li X, Stanton B, et al. Condom use among female sex workers in China: role of gatekeepers. Sex Transm Dis. 2005; 32(9):572–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindemann DF, Brigham TA. A Guttman scale for assessing condom use skills among college students. AIDS Behav. 2003; 7(1):23–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Everhart RS, Fiese BH. Development and initial validation of a pictorial quality of life measure for young children with asthma. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(9):966–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bandura A Perceived self-efficacy in the exercise of control over AIDS infection. Eval Program Plann. 1990;13:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bankole A, Ahmed FH, Neema S, Ouedraogo C, Konyani S. Knowledge of correct condom use and consistency of use among adolescents in four countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Afr J Reprod Health. 2007;11(3):197–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crosby RA, Salazar LF, Yarber WL, et al. A theory-based approach to understanding condom errors and problems reported by men attending an STI clinic. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(3):412–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang B, Li X, McGuire J, Kamali V, Fang X, Stanton B. Understanding the dynamics of condom use among female sex workers in China. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(3):134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noar SM, Carlyle K, Cole C. Why communication is crucial: meta-analysis of the relationship between safer sexual communication and condom use. J Health Commun. 2006;11(4):365–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Free C, Roberts I, McGuire M. Sex workers’ accounts of condom use: implications for condom production, promotion and health policy. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2007;33(2):107–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang X, Li X, Yang H, et al. Profile of female sex workers in a Chinese county: does it differ by where they came from and where they work? World Health Popul. 2007;9(1):46–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong Y, Fang X, Li X, Liu Y, Li M. Environmental support and HIV prevention behaviors among female sex workers in China. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(7):662–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia G, Yang X. Risky sexual behavior among female entertainment workers in China: implications for HIV/STD prevention intervention. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17(2):143–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li X, Wang B, Fang X, et al. Short-term effect of a cultural adaptation of voluntary counseling and testing among female sex workers in China: a quasi-experimental trial. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(5):406–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu W Brief of HIV/AIDS epidemic in Guangxi. Workshop on venue-based alcohol and sexual risk reduction intervention; Guilin, Guangxi, China; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlson RG, Wang J, Siegal HA, Falck RS, Guo J. An ethnographic approach to targeted sampling: problems and solutions in AIDS prevention research among injection drug and crack-cocaine users. Hum Organ. 1994;53:279–86. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 55 (No. RR-11). 1–100; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2006/rr5511.pdf (2006). Accessed 1 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright JC, Huston AC, Ross RP, et al. Pace and continuity of television programs: effects on children’s attention and comprehension. Dev Psychol. 1984;20:653–66. [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeVellis RF. Scale development: theory and application. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao R, Wang B, Fang X, Li X, Stanton B. Condom use and self-efficacy among female sex workers with steady partners in China. AIDS Care. 2008;20(7):782–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]