Abstract

Acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are caused by an exaggerated inflammatory response arising from a wide variety of pulmonary and systemic insults. Lung tissue is composed of a variety of cell populations, including parenchymal and immune cells. Emerging evidence has revealed that multiple cell populations in the lung work in concert to regulate lung inflammation in response to both direct and indirect stimulations. To date, the question of how different types of pulmonary cells communicate with each other and subsequently regulate or modulate inflammatory cascades remains to be fully addressed. In this review, we provide an overview of current advancements in understanding the role of cell—cell interaction in the development of ALI and depict molecular mechanisms by which cell—cell interactions regulate lung inflammation, focusing on inter-cellular activities and signaling pathways that point to possible therapeutic opportunities for ALI/ARDS.

Keywords: Acute lung injury, cell–cell interaction, crosstalk mechanisms, inflammatory responses, pulmonary inflammatory cells

INTRODUCTION

The lung is an important target organ for pro-inflammatory mediators secreted and released globally during sepsis (1) and trauma (2–4). These severe pathologies are often followed by the development of acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), characterized by pulmonary infiltrates and damage to both the lung vascular endothelium and alveolar epithelium. Globally, ALI/ARDS affect approximately 3 million patients annually with mortality rates estimated to range between 35% and 46% (5). Clinically, ALI/ARDS manifests as hypoxemia, appearing as bilateral opacities on chest radiography. As such, ALI/ARDS are associated with decreased lung compliance and increased venous admixture and physiological dead space (6, 7). Aside from sepsis, trauma, and major surgery, ALI/ARDS can also result from numerous other direct pulmonary insults and indirect systemic inflammatory responses (8). The reciprocal relationship between pulmonary and systemic inflammation augments the inflammatory process in the lung and promotes the development of ALI (9).

Following infection or trauma, inflammatory cytokines from resident cells, such as alveolar macrophages (AMϕ) or alveolar epithelial cells (AEpC), are secreted into the alveoli. This in turn induces the migration of a large number of inflammatory cells into the alveolar space. Inflammatory mediators are released from the migrated inflammatory cells and further contribute to tissue damage and the development of ALI and ARDS (10). Many studies have aimed to address how lung inflammation is augmented in critical conditions; however, the mechanisms underlying this process have yet to be fully elucidated. Emerging evidence has revealed that different lung parenchymal and immune cell populations work in concert to regulate lung inflammation. In this review, we provide an overview of current advancements in understanding the role of cell—cell interaction in the development of ALI. Comprehensive understanding of cellular crosstalk and underlying molecular mechanisms implicated in ALI/ARDS will allow for the development of novel preventive and therapeutic strategies.

CELL—CELL INTERACTION MECHANISMS OF ACUTE LUNG INFLAMMATION

The lung is a complicated organ composed of various cell types. ALI is a disorder of acute inflammation that causes the disruption of lung endothelial and epithelial barriers (11, 12). Cellular characteristics of ALI include loss of alveolar—capillary membrane integrity, excessive transepithelial neutrophil migration, and release of pro-inflammatory cytotoxic mediators (13). Advancements in understanding the recognition systems by which cells of the innate immune system recognize and respond to microbial products are key to the understanding of host defenses in the lungs and other tissues (14). While lung leukocytes are the paradigmatic inflammatory cell type, they are not the only cells that function in defense and immunity. The epithelial lining of the lung forms a continuous barrier to the environment and thus is the first line of defense against infectious agents and toxins (15–17). Polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) infiltration into the alveolar space is critical for the development of ALI/ARDS (18, 19). AMϕ, including resident Mϕ and recruited Mϕ from the blood, are key regulatory factors in the pathogenesis of ALI/ARDS as well (20, 21). Furthermore, studies have suggested that innate lymphoid cells (ILC) play an important role in maintaining airway barrier integrity and lung tissue homeostasis during infection (22, 23).

Evidence suggests that pulmonary cell communication plays a crucial role in the development and progression of ALI (24–26). Interactions between pulmonary inflammatory cells, including PMN—endothelial cell (EC), PMN-Mϕ, Mϕ-EC, and Mϕ-lymphocyte interactions, significantly contribute to the regulation of cell inflammatory responses (27–29). Additionally, it has been recognized that cell death and tissue inflammation reciprocally affect each other, forming an auto-amplification loop between these two factors and thus exaggerate inflammation (30).

PMN-EC INTERACTION

PMN are the first cells to be recruited to the site of inflammation. Rapid infiltration and accumulation of PMN in both interstitial and alveolar spaces of the lungs is a hallmark of lung inflammation and plays a central role in the development of ALI (31). Both clinical data and animal models indicate the importance of PMN in ALI. In patients with ARDS, the number of PMN in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid correlates closely with poor outcomes (32–34). Depletion of PMN in animal models of LPS-induced ALI ameliorates lung injury with reduced endothelial and epithelial damage and capillary-alveolar permeability (35). Although rapid PMN influx from circulation into sites of infection is essential for host defense and the clearance of microbial pathogens, over-activation of PMN leads to additional injury to the lungs due to the over-production of cytotoxic and immune cell-activating agents such as proteinases, cationic polypeptides, cytokines, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (36). Understanding how PMN function will then facilitate the design of therapeutic strategies that retain the beneficial aspects of the inflammatory response while avoiding unnecessary tissue damage.

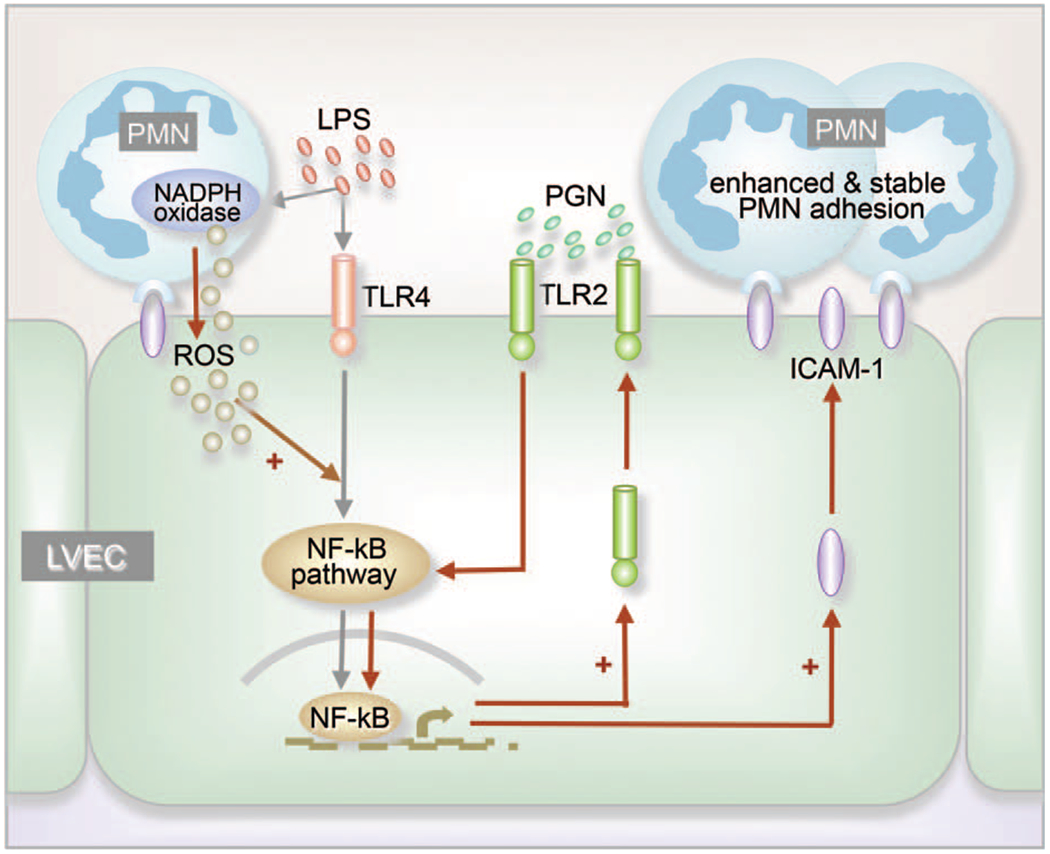

Vascular EC play a critical role in regulating PMN migration by the production of proinflammatory molecules, including leukocyte adhesion proteins, cytokines, and chemokines (37, 38). Lung vascular endothelial cells (LVEC) are a multifunctional cell monolayer that plays important roles in the regulation of vascular tone, coagulation and fibrinolysis, cellular growth, differentiation, and immune and inflammatory responses (39, 40). LVEC are critical for the regulation of lung inflammation and the development of ALI (41). LVEC death, inflammation, coagulation, and mechanical stretch are considered important mechanisms in the damage of AEpC in patients with ARDS (42). Interactions of PMN with EC contribute to the activation of specific EC responses involved in innate immunity. For example, we have reported that oxidant signal derived from the PMN NADPH oxidase complex mediates the interaction between PMN and LVEC and upregulates TLR2 expression in LVEC in response to LPS stimulation. Upregulation of TLR2 sensitizes LVEC to TLR2 ligand, i.e., peptidoglycan, and results in the stable and augmented expression of ICAM-1. This subsequently promotes PMN adhesion to the LVEC and enhances PMN transendothelial migration into the lungs (Fig. 1) (43, 44). These findings point to an important regulatory role of PMN-derived ROS in modulating LVEC activation and subsequent amplified PMN-EC adhesion.

Fig. 1. PMN-EC interaction enhances PMN adhesion to EC.

LPS stimulation causes NADPH oxidase activation and production of ROS in PMN, as well as initiation of NF-kB signaling in lung vascular EC (LVEC), and expression of TLR2 and ICAM-1. Adhesion of PMN to EC is primarily mediated by binding of constitutive ICAM-1 to CD11 b/CD18, which provides the appropriate coupling for PMN to transmit ROS signals to EC. The oxidants enhance NF-kB signaling and TLR2 expression (+). Increased TLR2 expression results in augmented response of the cell to peptidoglycan (PGN), thereby amplifies the ICAM-1 expression in LVEC (+) and provides stable adhesion of PMN to LVEC.

Studies have suggested that durability of the PMN sequestration is dependent on PMN-EC interactions. For example, mice deficient in L-selectin, an adhesion molecule expressed on PMN, experience only transient neutropenia after infusion of complement fragments: within minutes, the circulating PMN count returns to normal even if the complement infusion is continued (45). In another study, blockage of PMN L-selectin with a monoclonal antibody prevented PMN sequestration in alveolar capillaries induced by endotoxemia in rabbits (46). Further evidence for a potential role for ICAM-1 and CD11b/CD18 integrins, the adhesion molecules involved in mediating PMN-endothelial cell interactions, comes from a study that showed that cross-linking of CD18 and L-selectin could promote transcellular leukotriene biosynthesis during PMN-EC interactions (47).

LVEC are an important source of IL-1β. The production of active IL-1β is controlled by the inflammasome (41, 48). Our previous findings suggest that hemorrhagic shock (HS)-activated PMN and PMN NADPH oxidase are required for augmented activation of the endothelial inflammasome through enhanced ROS production in LVEC. High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), a ubiquitous nuclear protein that exists in virtually all cell types, is a DAMP molecule (49). In HS, released HMGB1 acting through TLR4 and a synergistic collaboration with TLR2 and receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) signaling activates LVEC NADPH oxidase. ROS derived from PMN NADPH oxidase further enhance the activation of LVEC NADPH oxidase, which results in marked increase of ROS in LVEC (50). In turn, intra-EC ROS promote the association of thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) with NLRP3 and subsequently induce inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion from the EC.

PMN-AMϕ INTERACTIONS

AMϕ account for approximately 95% of airspace leukocytes and are key to ALI pathogenesis through the secretion of various inflammatory mediators that regulate lung inflammation in response to pulmonary infection (51). There are two main types of Mϕ in the alveolus, resident AMϕ and recruited AMϕ (52). When a stimulus occurs, such as in ALI/ARDS, peripheral blood monocytes are recruited into the alveolar lumen. There, they differentiate into AMϕ with the M1 phenotype (53, 54). Resident AMϕ highly express receptors for pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) and damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecules. Resident AMϕ additionally work as antigen-presenting cells and release pro-inflammatory cytokines to drive the inflammatory response required to fight infection (55). The mediators generated and released from AMϕ include cytokines, chemokines, complement factors, alarmins, and arachidonic acid metabolites. These mediators may act as chemoattractants that promote leukocyte infiltration or stimulate local cells, such as epithelial cells and interstitial Mϕ, to build up a proinflammatory micromilieu (51, 56).

Rather than acting as isolated effector cells, Mϕ are in constant communication with other cells of the immune system. Studies suggest that Mϕ and PMN cooperate as key players in innate immune responses, both in protective processes and damage-associated pathogenesis.

Mϕ regulation of PMN migration

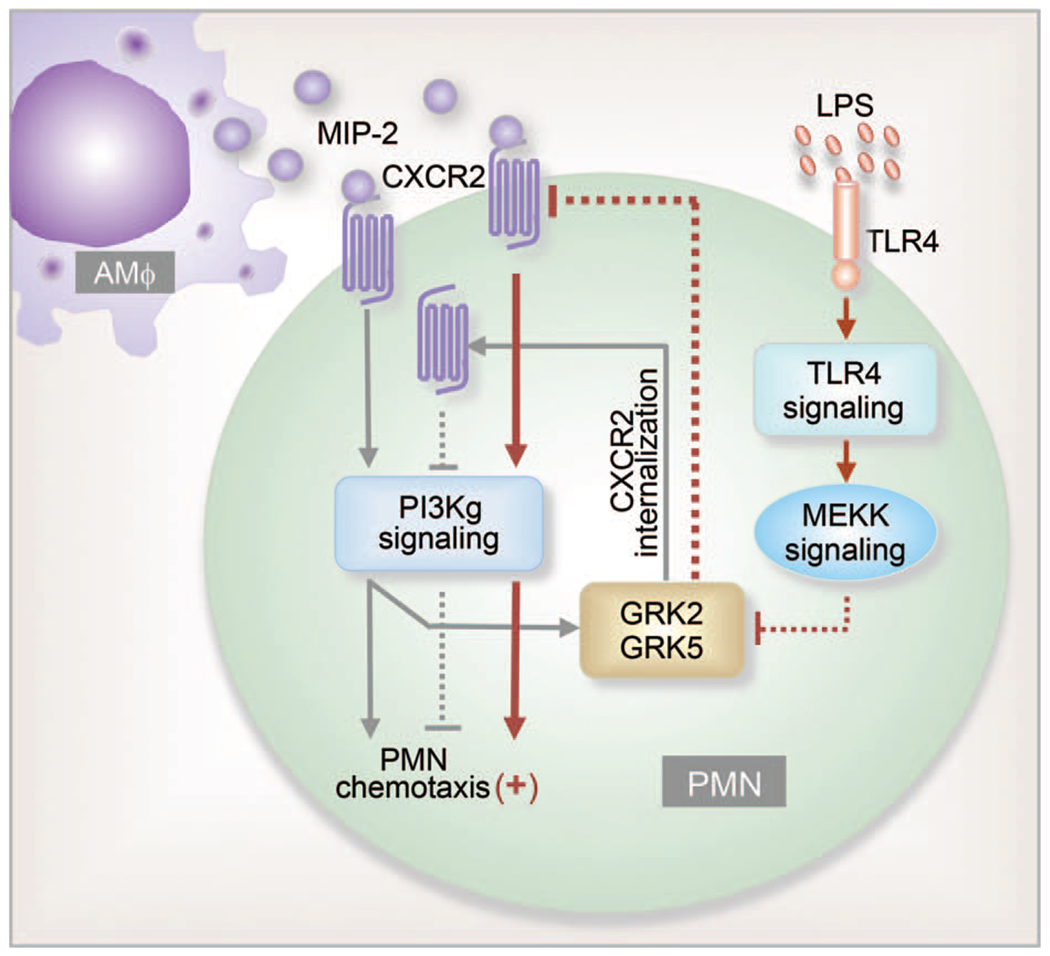

PMN migration is tightly regulated by signaling mechanisms activated by chemokines. These signaling mechanisms act through chemokine receptors to direct PMN migration along a concentration gradient (57). Chemokine receptors belong to the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family. In many cases, cellular response to an external signal decreases with time despite the continued presence of the signaling ligand. This attenuation of signaling is known as desensitization. Desensitization of chemokine receptors on PMN is an important determinant of the intensity and duration of agonist stimulation. Receptor desensitization regulates not only the number of migrating PMN but also their motility and ability to stop upon contact with pathogens or target cells (58). G-protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs), specific kinases that interact with GPCRs, induce receptor phosphorylation and thereby signal GPCR desensitization (59). We have shown that Mϕ-derived chemokine macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2) induces GRK2 and GRK5 expression in PMN through phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)-γsignaling. The induction of GRK2 and GRK5 forms a feedback mechanism that induces chemokine receptor desensitization in PMN and, thus, negatively regulates PMN migration. However, our study further showed that LPS-activated signaling through the TLR4 pathway transcriptionally downregulates the expression of GRK2 and GRK5 in response to MIP-2. The reduced expression of GRKs lowers chemokine receptor desensitization and markedly augments the PMN migratory response (Fig. 2) (60). The study demonstrates an important role for receptor cross-talk in mediating cell—cell interaction.

Fig. 2. Mϕ regulation of PMN chemotaxis.

Mϕ-derived chemokine MIP-2 binding to CXCR2 induces PMN migration as well as GRK2 and GRK5 expression through PI3Kγ signaling. Increased GRK2 and GRK5 expression results in chemokine receptor internalization and desensitization, thereby negatively regulating PMN migration. Thus, PI3Kγ-activated signaling is postulated to be a feedback mechanism regulating PMN migration. LPS acting through the TLR4 signaling pathway transcriptionally downregulates expression of GRK2 and GRK5 in response to MIP-2. This decreases chemokine receptor desensitization by preventing CXCR2 internalization and thus augments PMN migration. MEK kinase is involved in mediating the cross-talk between TLR4 and chemokine receptors. (Dashed lines show inhibitory signals).

In addition to secreting chemoattractants to drive PMN migration, Mϕ are in constant communication with PMN for the regulation of other immune responses. A recently published review article by Bouchery and Harris (61) summarized the roles of Mϕ-PMN cooperation in tissue repair and indicated that Mϕ-PMN cross-talk regulates the transition between the inflammatory, proliferative, and remodeling phases of repair.

Mϕ induce PMN necroptosis

Although the quick recruitment of PMN into sites of infection and injury is essential to the innate immune response, overproduction of hydrolytic enzymes and ROS by PMN has been considered a major cause of PMN-mediated damage to local surrounding tissues (62). PMN apoptosis, a form of regulated noninflammatory cell death, has been reported as an effective approach to control the number of local PMN. This facilitates a negative-feedback mechanism for inflammation and promoting its resolution (63, 64).

However, emerging evidence has shown that other types of regulated PMN death also occur during inflammation, exaggerating inflammation through release of DAMP molecules (65). We have reported a mechanism involved in how HS promotes lung inflammation through AMϕ-induced PMN necroptosis, a type of inflammatory cell death (66). Cell necroptosis is a pathway of regulated necrosis that requires the proteins RIK1, RIK3, and MLKL. We demonstrate that exosomes released from HS-activated AMϕ are engulfed by PMN and stimulate intra-PMN ROS production, which are mainly derived from NADPH oxidase and further promote PMN necroptosis. PMN necroptosis potentially influences the development of ALI. To determine the effect of AMϕ on PMN necroptosis, we used an in vivo HS mouse model and ex vivo hypoxia-reoxygenation model. We showed that AMϕ depletion significantly decreases HS-induced PMN necroptosis, and PMN cocultured with AMϕ demonstrate a significantly higher PMN necroptosis rate when compared to PMN cultured with no AMϕ in response to hypoxia-reoxygenation (66). Necroptosis plays a role in the initiation and amplification of inflammation by inducing immune activation and cytokine expression through release of DAMP (67). DAMP release, immune-cell activation, and release of death-inducing cytokines is an aggressive cycle of necroptosis and may fuel enhanced and prolonged inflammatory responses, contributing to the exaggerated lung inflammation following HS. The study provides insight into the mechanisms underlying the complicated reciprocal interaction between innate immune cells.

The role of extracellular vesicles (EV) in mediating cell—cell interaction has been well studied (68). Lee et al. (29) have shown the association between ALI and the generation of EV derived from platelets, neutrophils, monocytes, lymphocytes, red blood cells, EC, and EpC. Exosomes are one of the best-studied subpopulations of EV, generated by the reverse budding of multivesicular bodies within cells before their secretion. Exosomes contain a variety of molecules, including RNA, proteins, and lipids and have a bilipid membranous structure that can be taken up by recipient cells (69). As such, they mediate intercellular communication, stimulate target cells, promote antigen presentation, transfer pathogens, and regulate immune responses (70, 71).

PMN enhance Mϕ inflammatory responses

It has been reported that HS-resuscitation primes for exaggerated AMϕ activation, which contributes to augmented lung injury through increased release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and subsequent PMN sequestration (72, 73). The mechanisms underlying AMϕ priming are complicated and remain to be fully elucidated. PMN, through PMN—AMϕ interaction, enhance AMϕ inflammatory responses and serve as a significant priming mechanism in post-HS ALI. A study showed that in a mouse model of HS followed by intratracheal administration of LPS, HS-activated PMN play a critical role in TLR2 upregulation induced by LPS-TLR4 signaling in AMϕ (74). Antecedent HS primed for enhanced TLR2 upregulation in AMϕ in response to LPS stimulation. In neutropenic mice subjected to HS, LPS-induced TLR2 expression was significantly reduced. Additionally, TLR2 expression was restored upon repletion with PMN collected from HS mice but not by PMN from sham mice. These findings were recapitulated in mouse AMϕ cocultured with PMN. Enhanced TLR2 upregulation in AMϕ sensitized AMϕ to TLR2 ligand peptidoglycan and augmented the expression of MIP-2 and inflammatory cytokines, which is associated with amplified AMϕ-induced PMN migration into lung alveoli. Thus, TLR2 expression in AMϕ, signaled by TLR4 and regulated by HS-activated PMN, is an important positive-feedback mechanism responsible for HS-primed PMN infiltration into the lung after primary PMN sequestration (74).

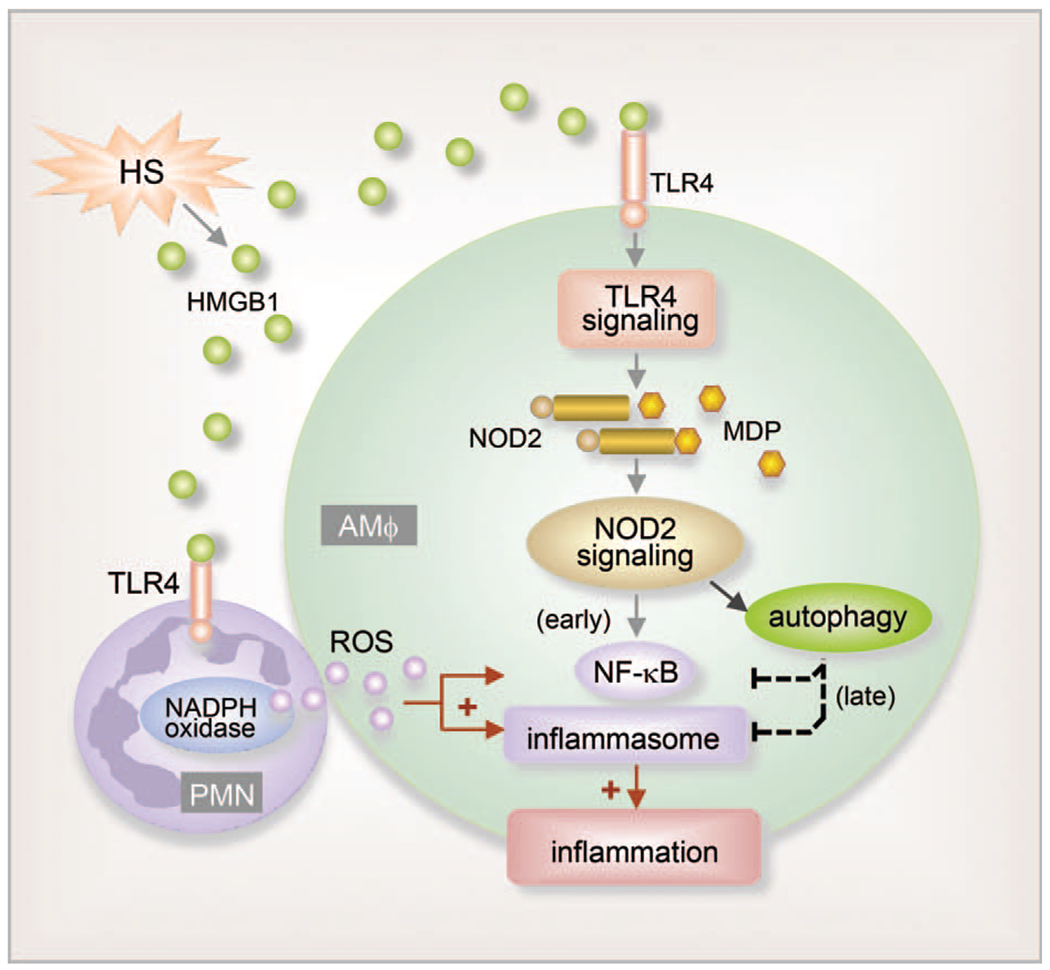

Furthermore, PMN are implicated in regulating AMϕ intracellular anti-inflammatory mechanisms involving autophagy. Using a mouse “two-hit” model of HS followed by intratracheal injection of muramyl dipeptide (MDP), a ligand of NOD2, we demonstrated that HS initiates HMGB1-TLR4 signaling, which upregulates NOD2 expression in AMϕ and sensitizes them to subsequent MDP challenge to augment lung inflammation (75). The results showed that upregulated NOD2 signaling induces autophagy in AMϕ, which negatively regulates lung inflammation through feedback suppression of NOD2-RIP2 signaling and inflammasome activation. However, HS-activated PMN that migrate into alveoli counteract the anti-inflammatory effect of autophagy in AMϕ, possibly through NADPH oxidase-mediated signaling, to enhance IKKγ phosphorylation, NF-κB activation, and NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and therefore augment post-HS lung inflammation. These findings show the complexity in the cell—cell interaction mechanisms of ALI (Fig. 3) (75).

Fig. 3. PMN counteraction of intra-Mϕ autophagic anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

HS increases HMGB1 release and HMGB1-TLR4 signaling, which upregulates NOD2 expression in AMϕ and a subsequent sensitization of AMϕ to NOD2 ligand MDP MDP-NOD2 signaling leads to augmented inflammation in the lung. Additionally, upregulated NOD2 signaling induces autophagy in AMϕ, which in turn negatively regulates lung inflammation by suppressing NOD2-RIP2 signaling and inflammasome activation. PMN counteract the anti-inflammatory effect of autophagy, possibly via NADPH oxidase-derived ROS, and therefore enhance post-HS lung inflammation.

PMN-enhanced Mϕ inflammatory responses were also observed in response to other infectious diseases. For example, Hsp72 released from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)-infected PMN can trigger Mϕ activation during the early stages of Mtb infections, creating a link between innate and adaptive immunity (76). Warnatsch et al. (77) reported that cholesterol crystals triggered PMN to release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). This primes Mϕ for cytokine release that amplifies immune cell recruitment in atherosclerotic plaques (77). In addition, lack of neutrophil-derived lipocalin (NGAL) reduces myeloid—epithelial—reproductive tyrosine kinase (MerTK) expression in cardiac Mϕ, thereby impairing Mϕ clearance of cellular debris. Cardiac Mϕ that proliferate in the absence of PMN adopt a reparative phenotype, inducing prominent fibrosis (78). These studies suggest an important role for PMN in regulating Mϕ function and behavior.

NETs induce Mϕ pyroptosis

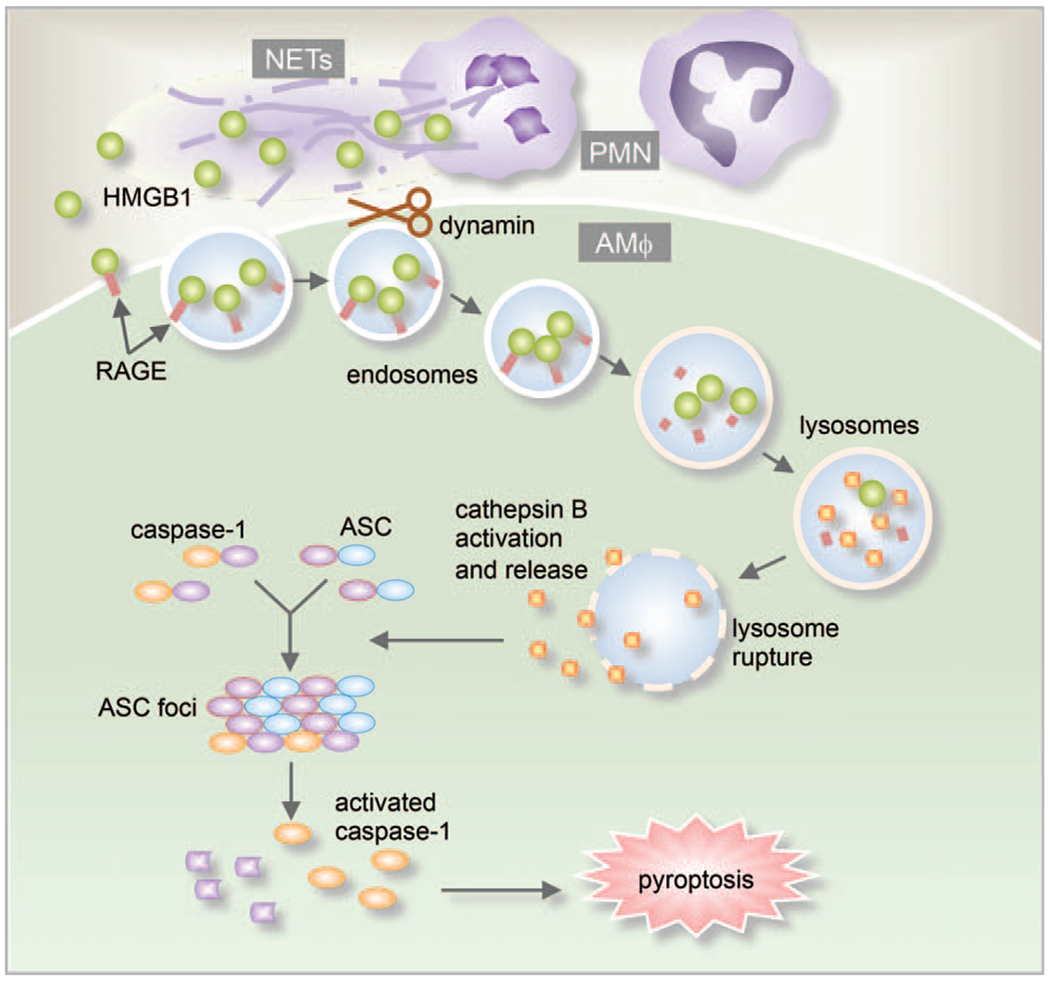

Emerging evidence has revealed that AMϕ death plays important roles in the progression of lung inflammation (79–81). Pyroptosis is a form of regulated cell death that is both inflammatory and immunogenic. Pyroptosis is triggered by various pathological stimuli, such as intracellular pathogens and extracytoplasmic stimuli. Cell pyroptosis is driven by the activation of inflammasome, a cytosolic multiprotein complex responsible for the release of IL-1 family members (e.g., IL-1β and IL-18), the formation of ASC specks, and the activation of pro-inflammatory caspases. The activation of caspase-1 or caspase 11/4/5 can cleave gasdermin D (GSDMD), a member of a conserved protein family which often exhibit pore-forming activity (82). Cleavage of GSDMD leads to the separation of its N-terminal pore-forming domain (PFD) from the C-terminal repressor domain followed by PFD oligomerization and the formation of large pores in the cell plasma membrane, causing cell swelling and membrane rupture (83). Inflammasome activation can be bypassed in HMGB1-induced Mϕ pyroptosis. HMGB1 is released from cells following infection and tissue injury and is a crucial inflammatory mediator in the induction of a range of cellular responses, including cell chemotaxis and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (84). HMGB1 binding to its cell surface receptors, including TLR2, TLR4, TLR9, and the RAGE, is necessary for initiating inflammatory responses (85, 86). We have reported an inflammasome-independent mechanism by which HMGB1 induces AMϕ pyroptosis. We demonstrated that HMGB1 acting through RAGE on AMϕ and dynamin-dependent signaling initiated HMGB1 endocytosis, which in turn induced cell pyroptosis. The endocytosis of HMGB1 triggered a cascade of molecular events including cathepsin B (CatB) release from ruptured lysosomes followed by pyroptosome formation and caspase-1 activation (79).

Our recent study showed that NETs also serve as a source of HMGB1, which triggers AMϕ pyroptosis (87). In response to microbial infection, the host releases NETs into the extracellular space to trap and kill the microbes (88, 89). NETs are composed of a meshwork of chromatin fibers mixed with granule-derived antimicrobial peptides and enzymes, such as elastase, cathepsin G, and myeloperoxidase. These structures play a critical role in the progression of host inflammation (90, 91). Our results show that NETs-derived HMGB1, acting through RAGE and dynamin-dependent signaling, triggers pyroptosome formation and caspase-1 activation, and subsequent Mϕ pyroptosis (Fig. 4) (87). Other studies have also supported the role for NETs in mediating PMN-Mϕ interaction. For example, NETs acting through inducing cytokine production from Mϕ promote inflammation and the development of atherosclerosis (77). These findings shed light on the proin-flammatory role of NETs in augmenting inflammation through mediating PMN-Mϕ interactions and provide us with new information for generating therapeutic strategies targeting NETs.

Fig. 4. NETs regulation of Mϕ pyroptosis.

NETs-derived HMGB1 acting through RAGE on macrophages triggers dynamin-dependent endocytosis of HMGB1, which in turn initiates a cascade of cellular and molecular events. These include CatB activation and release from ruptured lysosome followed by pyroptosome formation and caspase-1 activation, which serves as a mechanism underlying the HMGB1-induced pyroptosis.

ALVEOLAR EPITHELIAL CELL-Mϕ INTERACTION

AEpC serve as the first line of defense against pathogens in the alveolus and contribute to the integrity and respiratory function of the lungs during the development of ALI (17, 92). The alveolar epithelium is composed of two main cell types, alveolar epithelial type I cells (AEpC I) and type II cells (AEpC II) (11, 12). AEpC I account for ~80% of alveolar surface area, but only 20% of the total epithelial cells involved in mediating gas exchange and barrier function in the alveolus. In contrast, AEpC II are cuboidal and more numerous than AEpC I, making up ~80% of the total alveolar epithelium but only 20% of the surface area (93). Compared to AEpC I, AEpC II have many more important metabolic and biosynthetic functions, including the synthesis and secretion of the surfactant (94). AEpC II are also considered to be progenitors of the alveolar epithelium because of their ability to proliferate and differentiate into AEpC I (95). Recent evidence has suggested that AEpC are importantly involved in cell—cell crosstalk mechanisms of ALI.

Research from our group demonstrated a novel function of AEpC II in the regulation of AMϕ exosome release following LPS stimulation (96). We demonstrate that LPS induces AMϕ release of exosomes, which are internalized by neighboring AMϕ to promote TNF-α expression. Exosome secretion requires the fusion of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) with the cell plasma membrane. The Rab GTPases critically regulate the multiple steps of membrane trafficking, including vesicle budding, vesicle transport, and membrane fusion. It has been reported that knockdown of Rab family members, including Rab2b, Rab5a, Rab9a, Rab27a, or Rab27b, significantly decreases exosome secretion (97, 98). Rab27a and Rab27b have been reported as important regulatory factors governing intracellular vesicular trafficking critical for MVB docking to the plasma membrane (99). Secretion of IL-25 by AEpC II downregulates Rab27a and Rab27b expression in AMϕ, therefore suppressing AMϕ exosome release. This, in turn, decreases neighboring AMϕ internalization of exosomes and subsequent TNF-α expression and secretion (96). The IL-25-mediated downregulation of Rab27a and Rab27b expression serves as a mechanism underlying AEpC II suppression of AMϕ exosome release. These findings reveal a previously unidentified pathway of AEpC II-AMϕ cross-talk, which negatively regulates AMϕ inflammatory responses to LPS. Modulating IL-25 signaling and targeting exosome release may present a new therapeutic strategy for the treatment of ALI.

ILC2-EC INTERACTIONS

ILC are newly identified members of lymphoid lineage that have roles in innate immunity and host response to inflammation, infection, and tissue damage. ILC are defined by three main features: the absence of recombination activating gene (RAG)-dependent rearranged antigen receptors, lack of phenotypical markers of myeloid cell, and lymphoid morphology (100). ILC are further divided into three subgroups, ILC1, ILC2, and ILC3, based on their signature cytokine production and the transcription factors they use for regulating their development and function (101). ILC1 cells and natural killer (NK) cells share the ability to produce large amounts of interferon-γ (IFN-γ). ILC2 produce type 2 cytokines, e.g., interleukin (IL)-9 and IL-13, and are dependent on transcription factors GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA3) and retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor-α (ROR-α) for development and function. ILC3 include all ILC subtypes that produce IL-17 and/or IL-22. Their development and function depend on the transcription factor ROR-γt (23, 102).

As a major ILC population in the lungs, ILC2 are known to play an important role in maintaining airway barrier integrity and lung tissue homeostasis after virus infection, and thus have been suggested to be protective during infection (102). Studies have shown that epithelial- or myeloid cell-derived IL-25, IL-33, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) regulate ILC2 expansion and activation (103–105). Among these cytokines, IL-33 is a member of the IL-1 cytokine superfamily and functions as an alarmin when released from damaged or necrotic cells (106). Membrane-bound ST2, also referred to as IL1–1R4 serves as the cellular receptor for IL-33 on responsive cells, such as CD4 T-cell subsets, including Th2 and some T regulatory cells, mast cells, and ILC2. The expansion and activation of tissue-resident ILC2 is followed by increased hematogenous emigration and redistribution of ILC2 under physiologic or pathological conditions (107). ILC2 are noncytolytic but can be activated to produce type 2 cytokines, e.g., IL-9, IL-13, IL-5. We recently found that IL-33/ST2 signaling leads to a significant expansion of ILC2 cells in the lungs and peritoneal cavity following sepsis (108).

We investigated the role of ILC2 in the regulation of lung inflammation following sepsis and found that ILC2 protect lung EC from pyroptosis (108). Lung EC death has been reported to play an important role in the activation of a number of inflammatory cells, the release— of inflammatory mediators, and the induction of inflammation in sepsis (109). A previous report showed that TNF superfamily-associated pathways and activated caspases mediate EC death (110). We demonstrated that IL-33, released in response to sepsis, mediates ILC2 expansion in the lungs by acting through its receptor ST2. We further showed that the increased ILC2 in the lungs secrete IL-9, which prevents lung EC from undergoing pyroptosis by attenuating caspase-1 activation (108). These findings suggest a previously unidentified innate pathway that negatively regulates lung EC death and lung inflammation following sepsis.

CONCLUSION

ALI/ARDS are results of severe injury leading to dysfunction and compromised barrier properties of the pulmonary endothelium and epithelium due to an unregulated acute inflammatory response. Studies have shown a connection between cell—cell interaction and lung inflammation. Understanding the impact of cell—cell interaction on the progression of lung inflammation is critical in fully elucidating the mechanisms underlying ALI/ARDS. Other forms of cell—cell interaction that might be also implicated in ALI that are not discussed here, due to the lack of sufficient data, include AMϕ—T cell, ILC—T cell, PMN—EpC, and innate immune cells—fibroblast cells interactions. Gaps in knowledge on cell—cell interaction include whether different mechanisms of cell—cell interaction respond to specific triggers or general stimulations; how the different cell—cell interactions are dynamically developed during the progression of ALI; and how one type of cell—cell interaction may influence another type of cell—cell interaction and subsequently affect the outcomes. Comprehensive understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms that regulate cell—cell interaction will allow for the development of novel interventions for ALI/ARDS.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01-HL-079669 (JF), National Institutes of Health Grant R01-HL-139547 (JF), National Institutes of Health Grant R01HL076179 (JF), VA Merit Award 1I01BX002729 (JF), VA BLR&D Research Career Scientist Award BX004211 (JF), and the Jiangsu Scholarship for Overseas Studies JS-2018-123 (HZ).

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Winters BD, Eberlein M, Leung J, Needham DM, Pronovost PJ, Sevransky JE: Long-term mortality and quality of life in sepsis: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 38(5):1276–1283, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashbaugh DG, Bigelow DB, Petty TL, Levine BE: Acute respiratory distress in adults. Lancet 2(7511):319–323, 1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faist E, Baue AE, Dittmer H, Heberer G: Multiple organ failure in polytrauma patients. J Trauma 23(9):775–787, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowler AA, Hamman RF, Good JT, Benson KN, Baird M, Eberle DJ, Petty TL, Hyers TM: Adult respiratory distress syndrome: risk with common predispositions. Ann Intern Med 98(5 pt 1):593–597, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goss CH, Brower RG, Hudson LD, Rubenfeld GD: Incidence of acute lung injury in the United States. Crit Care Med 31(6):1607 —1611, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wheeler AP, Bernard GR: Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a clinical review. Lancet 369(9572):1553–1564, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erickson SE, Martin GS, Davis JL, Matthay MA, Eisner MD: Recent trends in acute lung injury mortality: 1996–2005. Crit Care Med 37(5):1574–1579,2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villar J, Sulemanji D, Kacmarek RM: The acute respiratory distress syndrome: incidence and mortality, has it changed? Curr Opin Crit Care 20(1):3–9, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan EK, Fan J: Regulation of alveolar macrophage death in acute lung inflammation. Res Res 19(1):50, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moldoveanu B, Otmishi P, Jani P, Walker J, Sarmiento X, Guardiola J, Saad M, Yu J: Inflammatory mechanisms in the lung. J Inflamm Res 2:1–11, 2009. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware LB, Matthay MA: The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 342(18):1334–1349, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matthay MA, Zimmerman GA: Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome: four decades of inquiry into pathogenesis and rational management. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 33(4):319–327, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herold S, Gabrielli NM, Vadász I: Novel concepts of acute lung injury and alveolar-capillary barrier dysfunction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 305(10):L665–L681, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castellheim A, Brekke OL, Espevik T, Harboe M, Mollnes T: Innate immune responses to danger signals in systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis. Scand J Immunol 69(6):479–491, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bals R, Hiemstra P: Innate immunity in the lung: how epithelial cells fight against respiratory pathogens. Eur Respir J 23(2):327–333, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasmussen SB, Reinert LS, Paludan SR: Innate recognition of intracellular pathogens: detection and activation of the first line of defense. Apmis 117(5–6):323–337, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manicone AM: Role of the pulmonary epithelium and inflammatory signals in acute lung injury. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 5(1):63–75, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zemans RL, Colgan SP, Downey GP: Transepithelial migration of neutrophils: mechanisms and implications for acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 40(5):519–535, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grommes J, Soehnlein O: Contribution of neutrophils to acute lung injury. Mol Med 17(3):293–307, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang X, Xiu H, Zhang S, Zhang G: The role of macrophages in the pathogenesis of ALI/ARDS. Mediators Inflammation 2018:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2018/1264913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaible B, Schaffer K, Taylor CT: Hypoxia, innate immunity and infection in the lung. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 174(3):235–243, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spits H, Artis D, Colonna M, Diefenbach A, Di Santo JP, Eberl G, Koyasu S, Locksley RM, McKenzie AN, Mebius RE: Innate lymphoid cells—a proposal for uniform nomenclature. Nature Rev Immunol 13(2):145, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonnenberg GF, Artis D: Innate lymphoid cells in the initiation, regulation and resolution of inflammation. Nat Med 21(7):698–708, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Liu JS, Peng SH, Deng XY, Zhu DM, Javidiparsijani S, Wang GR, Li DQ, Li LX, Wang YC: Gut-lung crosstalk in pulmonary involvement with inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol 19(40):6794–6804, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hines EA, Sun X: Tissue crosstalk in lung development. J Cell Biochem 115(9):1469–1477, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Linthout S, Miteva K, Tschöpe C: Crosstalk between fibroblasts and inflammatory cells. Cardiovasc Res 102(2):258–269, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva MT: Neutrophils and macrophages work in concert as inducers and effectors of adaptive immunity against extracellular and intracellular microbial pathogens. J Leukoc Biol 87(5):805–813, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lomas-Neira J, Venet F, Chung CS, Thakkar R, Heffernan D, Ayala A: Neutrophil—endothelial interactions mediate angiopoietin-2—associated pulmonary endothelial cell dysfunction in indirect acute lung injury in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 50(1):193–200, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee H, Abston E, Zhang D, Rai A, Jin Y: Extracellular vesicle: an emerging mediator of intercellular crosstalk in lung inflammation and injury. Front Immunol 9:924, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linkermann A, Stockwell BR, Krautwald S, Anders HJ: Regulated cell death and inflammation: an auto-amplification loop causes organ failure. Nat Rev Immunol 14(11):759–767, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abraham E: Neutrophils and acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 31(4):S195–S199, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthay MA, Eschenbacher WL, Goetzl EJ: Elevated concentrations of leukotriene D 4 in pulmonary edema fluid of patients with the adult respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Immunol 4(6):479–483, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parsons PE, Fowler AA, Hyers TM, Henson PM: Chemotactic activity in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis 132(3):490–493, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinberg KP, Milberg JA, Martin TR, Maunder RJ, Cockrill BA, Hudson LD: Evolution of bronchoalveolar cell populations in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 150(1):113–122, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abraham E, Carmody A, Shenkar R, Arcaroli J: Neutrophils as early immunologic effectors in hemorrhage-or endotoxemia-induced acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 279(6):L1137–L1145, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou X, Dai Q, Huang X: Neutrophils in acute lung injury. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 17:2278–2283, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ingber DE: Mechanical signaling and the cellular response to extracellular matrix in angiogenesis and cardiovascular physiology. Circ Res 91(10):877–887, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pober JS, Cotran RS: Cytokines and endothelial cell biology. Physiol Rev 70(2):427–451, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daniel TO, Abrahamson D: Endothelial signal integration in vascular assembly. Ann Rev Physiol 62(1):649–671, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iivanainen E, Kähäri VM, Heino J, Elenius K: Endothelial cell—matrix interactions. Microsc Res Tech 60(1):13–22, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orfanos S, Mavrommati I, Korovesi I, Roussos C. Pulmonary Endothelium in Acute Lung Injury: From Basic Science to the Critically Ill. Berlin: Springer, 2006, 171–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Standiford TJ, Ward PA: Therapeutic targeting of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Transl Res 167(1):183–191, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fan J, Frey RS, Rahman A, Malik AB: Role of neutrophil NADPH oxidase in the mechanism of TNFa-induced NF-kB activation and ICAM-1 expression in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 277:3404–3411, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fan J, Frey RS, Malik AB: TLR4 signaling induces TLR2 expression in endothelial cells via neutrophil NADPH oxidase. J Clin Invest 112(8):1234–1243, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doyle NA, Bhagwan SD, Meek BB, Kutkoski GJ, Steeber DA, Tedder TF, Doerschuk CM: Neutrophil margination, sequestration, and emigration in the lungs of L-selectin-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 99(3):526–533, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuebler WM, Borges J, Sckell A, Kuhnle GE, Bergh K, Messmer K, Goetz AE: Role of L-selectin in leukocyte sequestration in lung capillaries in a rabbit model of endotoxemia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161(1):36–43, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brady HR, Serhan CN: Adhesion promotes transcellular leukotriene biosynthesis during neutrophil-glomerular endothelial cell interactions: inhibition by antibodies against CD18 and L-selectin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 186(3):1307–1314, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rao DA, Tracey KJ, Pober JS: IL-1 α and IL-1β are endogenous mediators linking cell injury to the adaptive alloimmune response. J Immunol 179(10):6536–6546, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lotze MT, Tracey KJ: High-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1): nuclear weapon in the immune arsenal. Nat Rev Immunol 5(4):331–342, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiang M, Shi X, Li Y, Xu J, Yin L, Xiao G, Scott MJ, Billiar TR, Wilson MA, Fan J: Hemorrhagic shock activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in lung endothelial cells. J Immunol 187(9):4809–4817, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martin TR, Frevert CW: Innate immunity in the lungs. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2(5):403–411, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Short KR, Kroeze EJV, Fouchier RA, Kuiken T: Pathogenesis of influenza-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis 14(1):57–69, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duan M, Li WC, Vlahos R, Maxwell MJ, Anderson GP, Hibbs ML: Distinct macrophage subpopulations characterize acute infection and chronic inflammatory lung disease. J Immunol 189(2):946–955, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, Goerdt S, Gordon S, Hamilton JA, Ivashkiv LB, Lawrence T, et al. : Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity 41(1):14–20, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aggarwal NR, King LS, D’Alessio FR: Diverse macrophage populations mediate acute lung inflammation and resolution. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 306(8):L709–L725, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rivera A, Siracusa MC, Yap GS, Gause WC: Innate cell communication kick-starts pathogen-specific immunity. Nat Immunol 17(4):356–363, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baggiolini M: Chemokines and leukocyte traffic. Nature 392(6676):565–568, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lefkowitz RJ: G protein-coupled receptors. III. New roles for receptor kinases and beta-arrestins in receptor signaling and desensitization. J Biol Chem 273(30):18677–18680, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gainetdinov RR, Bohn LM, Walker JK, Laporte SA, Macrae AD, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ, Premont RT: Muscarinic supersensitivity and impaired receptor desensitization in G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5-deficient mice. Neuron 24(4):1029–1036, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fan J, Malik AB: Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) signaling augments chemokine-induced neutrophil migration by modulating cell surface expression of chemokine receptors. Nat Med 9(3):315–321, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bouchery T, Harris N: Neutrophil-macrophage cooperation and its impact on tissue repair. Immunol Cell Biol 97(3):289–298, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Imai Y, Kuba K, Neely GG, Yaghubian-Malhami R, Perkmann T, van Loo G, Ermolaeva M, Veldhuizen R, Leung YC, Wang H: Identification of oxidative stress and Toll-like receptor 4 signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury. Cell 133(2):235–249, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gilroy DW, Colville-Nash PR, McMaster S, Sawatzky DA, Willoughby DA, Lawrence T: Inducible cyclooxygenase-derived 15-deoxyΔ12-14PGJ2 brings about acute inflammatory resolution in rat pleurisy by inducing neutrophil and macrophage apoptosis. FASEB J 17(15):2269–2271, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fox S, Leitch AE, Duffin R, Haslett C, Rossi AG: Neutrophil apoptosis: relevance to the innate immune response and inflammatory disease. J Innate Immun 2(3):216–227, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vandenabeele P, Galluzzi L, Berghe TV, Kroemer G: Molecular mechanisms of necroptosis: an ordered cellular explosion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11(10):700–714, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiao Y, Li Z, Loughran PA, Fan EK, Scott MJ, Li Y, Billiar TR, Wilson MA, Shi X, Fan J: Frontline Science: macrophage-derived exosomes promote neutrophil necroptosis following hemorrhagic shock. J Leukoc Biol 103(2):175–183, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nagata S, Tanaka M: Programmed cell death and the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 17(5):333–340, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lace—donia D, Carpagnano GE, Trotta T, Palladino GP, Panaro MA, Zoppo LD, Foschino Barbaro MP, Porro C: Microparticles in sputum of COPD patients: a potential biomarker of the disease? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 11:527–533, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alexander M, Hu R, Runtsch MC, Kagele DA, Mosbruger TL, Tolmachova T, Seabra MC, Round JL, Ward DM, O’Connell RM: Exosome-delivered micro-RNAs modulate the inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nat Commun 6:7321, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fevrier B, Vilette D, Archer F, Loew D, Faigle W, Vidal M, Laude H, Raposo G: Cells release prions in association with exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101(26):9683–9688, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kojima M, Gimenes-Junior JA, Langness S, Morishita K, Lavoie-Gagne O, Eliceiri B, Costantini TW, Coimbra R: Exosomes, not protein or lipids, in mesenteric lymph activate inflammation: unlocking the mystery of post-shock multiple organ failure. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 82(1):42–50, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fan J, Kapus A, Li YH, Rizoli S, Marshall JC, Rotstein OD: Priming for enhanced alveolar fibrin deposition after hemorrhagic shock: role of tumor necrosis factor. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 22(4):412–421, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fan J, Kapus A, Marsden PA, Li YH, Oreopoulos G, Marshall JC, Frantz S, Kelly RA, Medzhitov R, Rotstein OD: Regulation of Toll-like receptor 4 expression in the lung following hemorrhagic shock and lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol 168(10):5252–5259, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fan J, Li Y, Vodovotz Y, Billiar TR, Wilson MA: Hemorrhagic shock-activated neutrophils augment TLR4 signaling-induced TLR2 upregulation in alveolar macrophages: role in hemorrhage-primed lung inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 290(4):L738–L746, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wen Z, Fan L, Li Y, Zou Z, Scott MJ, Xiao G, Li S, Billiar TR, Wilson MA, Shi X: Neutrophils counteract autophagy-mediated anti-inflammatory mechanisms in alveolar macrophage: role in posthemorrhagic shock acute lung inflammation. J Immunol 193(9):4623–4633, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Persson YAZ, Blomgran-Julinder R, Rahman S, Zheng L, Stendahl O: Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced apoptotic neutrophils trigger a pro-inflammatory response in macrophages through release of heat shock protein 72, acting in synergy with the bacteria. Microbes Infect 10(3):233–240, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Warnatsch A, Ioannou M, Wang Q, Papayannopoulos V: Neutrophil extracellular traps license macrophages for cytokine production in atherosclerosis. Science 349(6245):316–320, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Frodermann V, Nahrendorf M: Neutrophil-macrophage cross-talk in acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 38(3):198–200, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xu J, Jiang Y, Wang J, Shi X, Liu Q, Liu Z, Li Y, Scott M, Xiao G, Li S: Macrophage endocytosis of high-mobility group box 1 triggers pyroptosis. Cell Death Differ 21(8):1229–1239, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li Z, Scott M, Fan E, Li Y, Liu J, Xiao G, Li S, Billiar T, Wilson M, Jiang Y: Tissue damage negatively regulates LPS-induced macrophage necroptosis. Cell Death Differ 23(9):1428–1447, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang J, Zhao Y, Zhang P, Li Y, Yang Y, Yang Y, Zhu J, Song X, Jiang G, Fan J: Hemorrhagic shock primes for lung vascular endothelial cell pyroptosis: role in pulmonary inflammation following LPS. Cell Death Dis 7(9):e2363–e12363, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kovacs SB, Miao EA: Gasdermins: effectors of pyroptosis. Trends Cell Biol 27(9):673–684, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H, Zhuang Y, Cai T, Wang F, Shao F: Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature 526(7575):660–665, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang H, Wang H, Czura CJ, Tracey KJ: The cytokine activity of HMGB1. J Leukocyte Biol 78(1):1–8, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lu B, Nakamura T, Inouye K, Li J, Tang Y, Lundbäck P, Valdes-Ferrer SI, Olofsson PS, Kalb T, Roth J: Novel role of PKR in inflammasome activation and HMGB1 release. Nature 488(7413):670–674, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Andersson U, Tracey KJ: HMGB1 is a therapeutic target for sterile inflammation and infection. Annu Rev Immunol 29:139–162, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen L, Zhao Y, Lai D, Zhang P, Yang Y, Li Y, Fei K, Jiang G, Fan J: Neutrophil extracellular traps promote macrophage pyroptosis in sepsis. Cell Death Dis 9(6):1–12, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, Weinrauch Y, Zychlinsky A: Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 303(5663):1532–1535, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kaplan MJ, Radic M: Neutrophil extracellular traps: double-edged swords of innate immunity. J Immunol 189(6):2689–2695, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Papayannopoulos V, Zychlinsky A: NETs: a new strategy for using old weapons. Trends Immunol 30(11):513–521, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sørensen OE, Borregaard N: Neutrophil extracellular traps—the dark side of neutrophils. J Clin Invest 126(5):1612–1620, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gentry M, Taormina J, Pyles RB, Yeager L, Kirtley M, Popov VL, Klimpel G, Eaves-Pyles T: Role of primary human alveolar epithelial cells in host defense against Francisella tularensis infection. Infect Immun 75(8):3969–3978, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Corvol H, Flamein F, Epaud R, Clement A, Guillot L: Lung alveolar epithelium and interstitial lung disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41(8–9):1643–1651, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Andreeva AV, Kutuzov MA, Voyno-Yasenetskaya TA: Regulation of surfactant secretion in alveolar type II cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293(2):L259–L271, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mason RJ: Biology of alveolar type II cells. Respirology 11:S12–S15, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Li Z-G, Scott MJ, Brzoska T, Sundd P, Li Y-H, Billiar TR, Wilson MA, Wang P, Fan J: Lung epithelial cell-derived IL-25 negatively regulates LPS-induced exosome release from macrophages. Mil Med Res 5(1):24, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hoshino D, Kirkbride KC, Costello K, Clark ES, Sinha S, Grega-Larson N, Tyska MJ, Weaver AM: Exosome secretion is enhanced by invadopodia and drives invasive behavior. Cell Rep 5(5):1159–1168, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bonifacino JS, Glick BS: The mechanisms of vesicle budding and fusion. Cell 116(2):153–166, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ostrowski M, Carmo NB, Krumeich S, Fanget I, Raposo G, Savina A, Moita CF, Schauer K, Hume AN, Freitas RP: Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nat Cell Biol 12(1):19–30, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Spits H, Artis D, Colonna M, Diefenbach A, Di Santo JP, Eberl G, Koyasu S, Locksley RM, McKenzie AN, Mebius RE, et al. : Innate lymphoid cells—a proposal for uniform nomenclature. Nat Rev Immunol 13(2):145–149, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Juelke K, Romagnani C: Differentiation of human innate lymphoid cells (ILCs). Curr Opin Immunol 38:75–85, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Abt MC, Alenghat T, Ziegler CG, Doering TA, Angelosanto JM, Laidlaw BJ, Yang CY, Sathaliyawala T: Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat Immunol 12(11):1045, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mjösberg JM, Trifari S, Crellin NK, Peters CP, Van Drunen CM, Piet B, Fokkens WJ, Cupedo T, Spits H: Human IL-25-and IL-33-responsive type 2 innate lymphoid cells are defined by expression of CRTH2 and CD161. Nat Immunol 12(11):1055–1062, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Huang Y, Guo L, Qiu J, Chen X, Hu-Li J, Siebenlist U, Williamson PR, Urban JF Jr, Paul WE: IL-25-responsive, lineage-negative KLRG1 hi cells are multipotential ‘inflammatory’type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol 16(2):161–169, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kim BS, Siracusa MC, Saenz SA, Noti M, Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Hepworth MR, Van Voorhees AS, Comeau MR, Artis D: TSLP elicits IL-33—independent innate lymphoid cell responses to promote skin inflammation. Sci Transl Med 5(170):170ra16–ra1170, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Miller AM: Role of IL-33 in inflammation and disease. J Inflamm (Lond) 8(1):22, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gasteiger G, Fan X, Dikiy S, Lee SY, Rudensky AY: Tissue residency of innate lymphoid cells in lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs. Science 350(6263):981–985, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lai D, Tang J, Chen L, Fan EK, Scott MJ, Li Y, Billiar TR, Wilson MA, Fang X, Shu Q: Group 2 innate lymphoid cells protect lung endothelial cells from pyroptosis in sepsis. Cell Death Dis 9(3):1–12, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Coletta C, Módis K, Oláh G, Brunyánszki A, Herzig DS, Sherwood ER, Ungvári Z, Szabo C: Endothelial dysfunction is a potential contributor to multiple organ failure and mortality in aged mice subjected to septic shock: preclinical studies in a murine model of cecal ligation and puncture. Crit Care 18(5):511, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gill SE, Taneja R, Rohan M, Wang L, Mehta S: Pulmonary microvascular albumin leak is associated with endothelial cell death in murine sepsis-induced lung injury in vivo. PLoS One 9(2):e88501, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]